The Project Gutenberg EBook of Jane Sinclair; Or, The Fawn Of Springvale

by William Carleton

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Jane Sinclair; Or, The Fawn Of Springvale

The Works of William Carleton, Volume Two

Author: William Carleton

Illustrator: M. L. Flanery

Release Date: June 7, 2005 [EBook #16005]

Last Updated: September 6, 2016

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK JANE SINCLAIR ***

Produced by David Widger

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

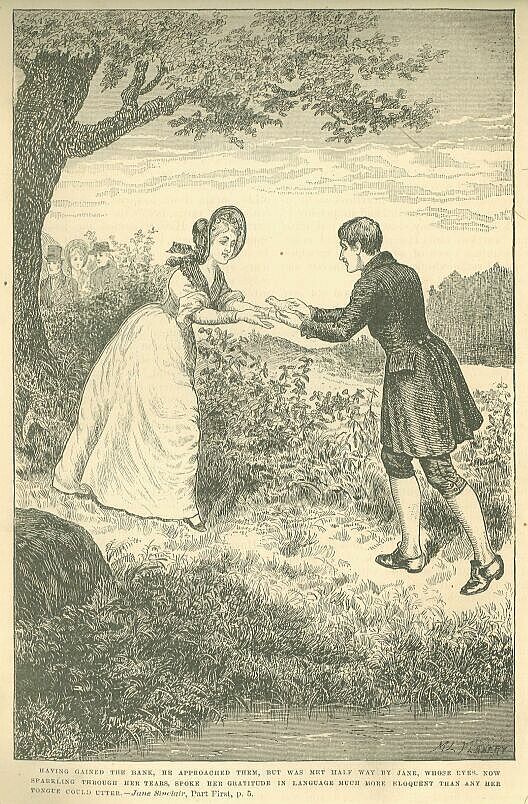

Page 5— Having Gained the Bank, he Approached Them

If there be one object in life that stirs the current of human feeling more sadly than another, it is a young and lovely woman, whose intellect has been blighted by the treachery of him on whose heart, as on a shrine, she offered up the incense of her first affection. Such a being not only draws around her our tenderest and most delicate sympathies, but fills us with that mournful impression of early desolation, resembling so much the spirit of melancholy romance that arises from one of those sad and gloomy breezes which sweep unexpectedly over the sleeping surface of a summer lake, or moans with a tone of wail and sorrow through the green foliage of the wood under whose cooling shade we sink into our noon-day dream. Madness is at all times a thing of fearful mystery, but when it puts itself forth in a female gifted with youth and beauty, the pathos it causes becomes too refined for the grossness of ordinary sorrow—almost transcends our notion of the real, and assumes that wild interest which invests it with the dim and visionary light of the ideal. Such a malady constitutes the very romance of affliction, and gives to the fair sufferer rather the appearance of an angel fallen without guilt, than that of a being moulded for mortal purposes. Who ever could look upon such a beautiful ruin without feeling the heart sink, and the mind overshadowed with a solemn darkness, as if conscious of witnessing the still and awful gloom of that disastrous eclipse of reason, which, alas! is so often doomed never to pass away.

It is difficult to account for the mingled reverence, and terror, and pity with which we look upon the insane, and it is equally strange that in this case we approach the temple of the mind with deeper homage, when we know that the divinity has passed out of it. It must be from a conviction of this that uncivilized nations venerate deranged persons as inspired, and in some instance go so far, I believe, as even to pay them divine worship.

The principle, however, is in our nature: that for which our sympathy is deep and unbroken never fails to secure our compassion and respect, and ultimately to excite a still higher class of our moral feelings.

These preliminary observations were suggested to me by the fate of the beautiful but unfortunate girl, the melancholy, events of whose life I am about to communicate. I feel, indeed, that in relating them, I undertake a task that would require a pen of unexampled power and delicacy. But it is probable that if I remained silent upon a history at once so true, and so full of sorrow; no other person equally intimate with its incidents will ever give them to the world. I cannot presume to detail unhappy Jane’s, calamity with the pathos due to a woe so singularly deep and delicate, or to describe that faithful attachment which gave her once laughing and ruby lips the white smile of a maniac’s misery. This I cannot do; for who, alas, could ever hope to invest a dispensation so dark as her’s with that rich tone of poetic beauty which threw its wild graces about her madness? For my part, I consider the subject not only as difficult, but sacred, and approach it on both accounts with devotion, and fear, and trembling. I need scarcely inform the reader that the names and localities are, for obvious reasons, fictitious, but I may be permitted to add that the incidents are substantially correct and authentic.

Jane Sinclair was the third and youngest daughter of a dissenting clergyman, in one of the most interesting counties in the north of Ireland. Her father was remarkable for that cheerful simplicity of character which is so frequently joined to a high order of intellect and an affectionate warmth of heart. To a well-tempered zeal in the cause of faith and morals, he added a practical habit of charity, both in word and deed, such as endeared him to all classes, but especially to those whose humble condition in life gave them the strongest claim upon his virtues, both as a man and a pastor. Difficult, indeed, would it be to find a minister of the gospel, whose practice and precept corresponded with such beautiful fitness, nor one who, in the midst of his own domestic circle, threw such calm lustre around him as a husband and a father. A temper grave but sweet, wit playful and innocent, and tenderness that kept his spirit benignant to error without any compromise of duty, were the links which bound all hearts to him. Seldom have I known a Christian clergyman who exhibited in his own life so much of the unaffected character of apostolic holiness, nor one of whom it might be said with so much truth, that “he walked in all the commandments of the Lord blameless.”

His family, which consisted of his wife, one son, and three daughters, had, as might be expected, imbibed a deep sense of that religion, the serene beauty of which shone so steadily along their father’s path of life. Mrs. Sinclair had been well educated, and in her husband’s conversation and society found further opportunity of improving, not only her intellect, but her heart. Though respectably descended, she could not claim relationship with what may be emphatically termed the gentry of the country; but she could with that class so prevalent in the north of Ireland, which ranks in birth only one grade beneath them. I say in birth;—for in all the decencies of life, in the unostentatious bounties of benevolence, in moral purity, domestic harmony, and a conscientious observance of religion, both in the comeliness of its forms, and the cheerful freedom of its spirit, this class ranks immeasurably above every other which Irish society presents. They who compose it are not sufficiently wealthy to relax those pursuits of honorable industry which constitute them, as a people, the ornament of our nation; nor does their good-sense and decent pride permit them to follow the dictates of a mean ambition, by struggling to reach that false elevation, which is as much beneath them in all the virtues that grace life, as it is above them in the dazzling dissipation which renders the violation or neglect of its best duties a matter of fashionable etiquette, or the shameful privilege of high birth. To this respectable and independent class did the immediate relations of Mrs. Sinclair belong; and, as might be expected, she failed not to bring all its virtues to her husband’s heart and household—there to soothe him by their influence, to draw fresh energy from their mutual intercourse, and to shape the habits of their family into that perception of self-respect and decent propriety, which in domestic duty, dress, and general conduct, uniformly results from a fine sense of moral feeling, blended with high religious principle. This, indeed, is the class whose example has diffused that spirit of keen intelligence and enterprise throughout the north which makes the name of an Ulster manufacturer or merchant a synonym for integrity and honor. From it is derived the creditable love of independence which operates upon the manners of the people and the physical soil of the country so obviously, that the natural appearance of the one may be considered as an appropriate exponent of the moral condition of the other. Aided by the genius of a practical and impressive creed, whose simple grandeur gives elevation and dignity to its followers;—this class it is which, by affording employment, counsel, and example to many of the lower classes, brings peace and comfort to those who inhabit the white cottages and warm farmsteads of the north, and lights up its cultivated landscapes, its broad champaigns, and peaceful vales, into an aspect so smiling, that even the very soil seems to proclaim and partake of the happiness of its inhabitants. Indeed, few spots in the north could afford the spectator a better opportunity of verifying our observations as to the mild beauty of the country, than the residence of the amiable clergyman whose unhappy child’s fate has furnished us with the affecting circumstances we are about to lay before the reader.

Springvale House, Mr. Sinclair’s residence, was situated on an eminence that commanded a full view of the sloping valley from which it had its name. Along this vale, winding towards the house in a northern direction, ran a beautiful tributary stream, accompanied for nearly two miles in its progress by a small but well conducted road, which indeed had rather the character of a green lane than a public way, being but very little of a thoroughfare. Nothing could surpass this delightful vale in the soft and serene character of its scenery. Its sides, partially wooded, and cultivated with surpassing taste, were not so precipitous as to render habitation in its bosom inconvenient. They sloped up gradually and gracefully on each side, presenting to the eye a number of snow-white residences, each standing upon the brow of some white table or undulation, and surrounded by grounds sufficiently spacious to allow of green lawns, ornamented plantations, and gardens, together with a due proportion of land for cultivation and pasture. From Mr. Sinclair’s house the silver bends of this fine stream gave exquisite peeps to the spectator as they wound out of the wood which here and there clothed its banks, occasionally dipping into the water. On the loft, attached to the glebe-house of the Protestant pastor of the parish, the eye rested upon a pond as smooth as a mirror, except where an occasional swan, as it floated onwards without any apparent effort, left here and there a slight quivering ripple behind it. Farther down, springing from between two clumps of trees, might be seen the span of a light and elegant arch, from under which the river gently wound away to the right; and beyond this, on the left, about a hundred yards from the bank, rose up the slender spire of the parish church, out of the bosom of the old beeches that overshadowed it, and threw a solemn gloom upon the peaceful graveyard at its side. About two hundred yards again to the right, in a little green shelving dell beneath the house, stood Mr. Sinclair’s modest white meeting-house, with a large ash tree hanging over each gable, and a row of poplars behind it. The valley at the opposite extremity opened upon a landscape bright and picturesque, dotted with those white residences which give that peculiar character of warmth and comfort for which the northern landscapes are so remarkable. Indeed the eye could scarcely rest upon a richer expanse of country than lay stretched out before it, nor can we omit to notice the singularly unique and beautiful effect produced by the numerous bleach-greens that shone at various degrees of distance, and contrasted so sweetly with the surface of a land deeply and delightfully verdant.

In the far distance rose the sharp outlines of a lofty mountain, whose green and sloping base melted into the “sun-silvered” expanse of the sea, on the smooth bosom of which the eye could snatch brilliant glimpses of the snow-white sails that sparkled at a distance as they fell under the beams of the noonday sun. The landscape was indeed beautiful in itself, but still rendered more so by the delicate aerial tints which lay on every object, and touched the whole into a mellower and more exquisite expression.

Such was the happy valley in which this peaceful family resided; each and all enjoying that tranquility which sheds its calm contentment over the unassuming spirits of those who are ignorant of the crimes that flow from the selfishness and ambition of busy life. To them, the fresh breezes of morning, as they rustled through the living foliage, and stirred the modest flowers of their pleasant path, were fraught with an enjoyment which bound their hearts to every object around them, because to each of them these objects were the sources of habitual gratification. On them the dewy stillness of evening descended with tender serenity, as the valley shone in the radiance of the sinking sun; and by them was held that sweet and rapturous communion with nature, which, as it springs earliest in the affections so does it linger about the heart when all the other loves and enmities of life are forgotten. Who is there, indeed, whose spirit does not tremble with tenderness, on looking back upon the scenes of his early life? And, alas! alas! how few are there of those that are long conversant with the world, who can take such a retrospect without feeling their hearts weighed down by sorrow, and the force of associations too mournful to be uttered in words. The bitter consciousness that we can be youthful no more, and that the golden hours of our innocence have passed away for ever, throws a melancholy darkness over the soul, and sends it back again to retrace, in the imaginary light of our early time, the scenes where that innocence had been our playmate. Let no man deny that groves, and meadows, and green fields, and winding streams, and all the other charms of rural imagery, unconsciously but surely give to the human heart a deep perception of that graceful creed which is beautifully termed the religion of nature. They give purity and strength to feeling, and through the imagination, which owes so much of its power to their impressions, they raise our sentiments until we feel them kindled into union with the lustre of a holier light than even that which leads our steps to God through the beauty of his own works. For this reason it is, that all imaginative affections are much stronger in the country than in the town. Love in the one place is not only freer from the coarseness of passion, but incomparably more seductive to the heart, and more voluptuous in its conception of the ideal beauty with which it invests the object of its attachment. Nor is this surprising. In the country its various associations are essentially impressive and poetical. Moonlight—evening—the still glen—the river side—the flowery hawthorn—the bower—the crystal well—not forgetting the melody of the woodland songster—are all calculated, to make the heart and fancy surrender themselves to the blandishments of a passion that is surrounded by objects so sweetly linked to their earliest sympathies. But this is not all. In rural life, neither the heart nor the eye is distracted by the claims of rival beauty, when challenging, in the various graces of many, that admiration which might be bestowed on one alone, did not each successive impression efface that which went before it. In the country, therefore, in spring meadows, among summer groves, and beneath autumnal skies, most certainly does the passion of love sink deepest into the human heart, and pass into the greatest extremes of happiness or pain. Here is where it may be seen, cheek to cheek, now in all the shivering ecstacies of intense rapture, or again moping carelessly along, with pale brow and flashing eye, sometimes writhing in the agony of undying attachment, or chanting its mad lay of hope and love in a spirit of fearful happiness more affecting than either misery or despair.

Everything was beautiful in the history of unhappy Jane Sinclair’s melancholy fate. The evening of the incident to which the fair girl’s misery might eventually be traced was one of the most calm and balmy that could be witnessed even during the leafy month of June. With the exception of Mrs. Sinclair, the whole family had gone out to saunter leisurely by the river side; the father between his two eldest daughters, and Jane, then sixteen, sometimes chatting to her brother William, and sometimes fondling a white dove, which she had petted and trained with such success that it was then amenable to almost every light injunction she laid upon it. It sat upon her shoulder, which, indeed, was its usual seat, would peck her cheek, cower as if with a sense of happiness in her bosom, and put its bill to her lips, from which it was usually fed, either to demand some sweet reward for its obedience, or to express its attachment by a profusion of innocent caresses. The evening, as we said, was fine; not a cloud could be seen, except a pile of feathery flakes that hung far up at the western gate of heaven; the stillness was profound; no breathing even of the gentlest zephyr, could be felt; the river beside them, which was here pretty deep, seemed motionless; not a leaf of the trees stirred; the very aspens were still as if they had been marble; and the whole air was warm and fragrant. Although the sun wanted an hour of setting, yet from the bottom of the vale they could perceive the broad shafts of light which shot from his mild disk through the snowy clouds we have mentioned, like bars of lambent radiance, almost palpable to the touch. Yet, although this delightful silence was so profound, the heart could perceive, beneath its stillest depths, that voiceless harmony of progressing life, which, like the music of a dream, can reach the soul independently of the senses, and pour upon it a sublime sense of natural inspiration.

Something like this appears to have been felt by the group we have alluded to. Mr. Sinclair, after standing for a moment on the bank of the river, and raising his eyes to the solemn splendor of the declining sun, looked earnestly around him, and then out upon the glowing landscape that stretched beyond the valley, after which, with a spirit of high-enthusiasm, he exclaimed, catching at the same time the fire and grandeur of the poet’s noble conception—

These are thy glorious works. Parent of good!

Almighty! thine this universal fame—

Thus wondrous fair—thyself how wondrous then—

To us invisible, or dimly seen

In these thy lowest works.

There was something singularly impressive in the burst of piety which the hour and the place drew from this venerable pastor, as indeed there was in the whole group, as they listened in the attitude of deep attention to his words. Mr. Sinclair was a tall, fine-looking old man, whose white flowing locks fell down on each side of his neck. His figure appeared to fine advantage, as, standing a little in front of his children, he pointed with his raised arm to the setting sun; behind him stood his two eldest girls, the countenance of one turned with an expression of awe and admiration towards the west; that of the other fixed with mingled reverence and affection on her father. William stood near Jane, and looked out thoughtfully towards the sea, while Jane herself, light, and young, and beautiful, stood with a hushed face, in the act of giving a pat of gentle rebuke to the snow-white dove on her bosom. At length they resumed their walk, and the conversation took a lighter turn. The girls left their father’s side, and strolled in many directions through the meadow. Sometimes they pulled wild flowers, if marked by more than ordinary beauty, or gathered the wild mint and meadow-sweet to perfume their dairy, or culled the flowery woodbine to shed its delicate fragrance through their sleeping-rooms. In fact, all their habits and amusements were pastoral, and simple, and elegant. Jane accompanied them as they strolled about, but was principally engaged with her pet, which flew, in capricious but graceful circles over her head, and occasionally shot off into the air, sweeping in mimic flight behind a green knoll, or a clump of trees, completely out of her sight; after which it would again return, and folding its snowy pinions, drop affectionately upon her shoulder, or into her bosom. In this manner they proceeded for some time, when the dove again sped off across the river, the bank of which was wooded on the other side. Jane followed the beautiful creature with a sparkling eye, and saw it wheeling to return, when immediately the report of a gun was heard from the trees directly beneath it, and the next moment it faltered in its flight, sunk, and with feeble wing, struggled to reach the object of its affection. This, however, was beyond its strength. After sinking gradually towards the earth, it had power only to reach the middle of the river, into the deepest part of which it fell, and there lay fluttering upon the stream.

The report of the gun, and the fate of the pigeon, brought the personages of our little drama with hurrying steps to the edge of the river. One scream of surprise and distress proceeded from the lips of its fair young mistress, after which she wrung her hands, and wept and sobbed like one in absolute despair.

“Oh, dear William,” she exclaimed, “can you not rescue it? Oh, save it—save it; if it sinks I will never see it more. Oh, papa, who could be so cruel, so heartless, as to injure a creature so beautiful and inoffensive?”

“I know not, my dear Jane; but cruel and heartless must the man be that could perpetrate a piece of such wanton mischief. I should rather think it is some idle boy who knows not that it is tame.”

“William, dear William, can you not save it,” she inquired again of her brother; “if it is doomed to die, let it die with me; but, alas! now it must sink, and I will never see it more;” and the affectionate girl continued to weep bitterly.

“Indeed, my dear Jane, I never regretted my ignorance of swimming so much as I do this moment. The truth is, I cannot swim a stroke, otherwise I would save poor little Ariel for your sake.”

“Don’t take it so much to heart, my dear child,” said her father; “it is certainly a distressing incident, but, at the same time, your grief, girl, is too excessive; it is violent, and you know it ought not to be violent for the death of a favorite bird.”

“Oh, papa, who can look upon its struggles for life, and not feel deeply; remember it was mine, and think of its attachment to me. It has not only the pain of its wound to suffer, but to struggle with an element against which it feels a natural antipathy, and with which the gentle creature is this moment contending for its life.”

There was, indeed, something very painful and affecting in the situation of the beautiful wounded dove. Even Mr. Sinclair himself, in witnessing its unavailing struggles, felt as much; nor were the other two girls unaffected any more than Jane herself. Their eyes became filled with tears, and Maria, the eldest, said, “It is better, Jane, to return home. Poor mute creature! the view of its sufferings is, indeed, very painful.”

Just then a tall, slender youth, apparently about eighteen, came out of the trees on the other bank of the river but on seeing Mr. Sinclair and his family, he paused, and appeared to feel somewhat embarrassed. It was evident he had seen the bird wounded, and followed the course of its flight, without suspecting that it was tame, or that there was any person near to claim it. The distress of the females, however, especially of its mistress, immediately satisfied him that it was theirs, and he was about to withdraw into the wood again, when the situation of poor Ariel caught his eye. He instantly took off his hat, flung it across the river, and plunging in swam towards the dove, which was now nearly exhausted. A few strokes brought him to the spot, on reaching which, he caught the bird in one hand, held it above the water, and, with the other, swam down towards a slope in the bank a few yards below the spot where the party stood. Having gained the bank, he approached them, but was met half way by Jane, whose eyes, now sparkling through her tears, spoke her gratitude in language much more eloquent than any her tongue could utter.

The youth first examined the bird, with a view to ascertain where it had been wounded, and immediately placed it with much gentleness in the eager hands of its mistress.

“It will not die, I should think, in consequence of the wound,” he observed, “which, though pretty severe, has left the wing unbroken. The body, at all events, is safe. With care it may recover.”

William then handed him his hat and Mr. Sinclair having thanked him for an act of such humanity, insisted that he should go home with them, in order to procure a change of apparel. At first he declined this offer, but, after a little persuasion, he yielded with something of shyness and hesitation: accordingly, without loss of time, they all reached the house together.

Having, with some difficulty, been prevailed on to take a glass of cordial, he immediately withdrew to William’s apartment, for the purpose of changing his dress. William, however, now observed that he got pale, and that in a few minutes afterwards his teeth began to chatter, whilst he shivered excessively.

“You had better lose no time in putting these dry clothes on,” said he; “I am rather inclined to think bathing does not agree with you, that is, if I am to judge by your present paleness and trembling.”

“No,” said the youth, “it is a pleasure which, for the last two years, I have been forbidden. I feel very chilly, indeed, and you will excuse me for declining the use of your clothes. I must return home forthwith.”

Young Sinclair, however, would not hear of this. After considerable pains he prevailed on him to change his dress, but no argument could induce him to stop a moment longer than until this was effected.

The family, on his entering the drawing-room to take his leave, were surprised at a determination so sudden and unexpected, but when Mr. Sinclair noticed his extreme paleness, he suspected that he had got ill, and that it might not be delicate to press him.

“Before you leave us,” said the good clergyman, “will you not permit us to know the name of the young gentleman to whom my daughter is indebted for the rescue of her dove?”

“We are as yet but strangers in the neighborhood,” replied the youth: “my father’s name is Osborne. We have not been more than three days in Mr. Williams’s residence, which, together with the whole of the property annexed to it, my father has purchased.”

“I am aware, I am aware: then you will be a permanent neighbor of ours,” said Mr. Sinclair; “and believe me, my dear boy, we shall always be happy to see you at Springvale; nor shall we soon forget the generous act which first brought us acquainted.”

Whilst this short dialogue lasted, two or three shy sidelong glances passed between him and Jane. So extremely modest was the young man that, from an apprehension lest these glances might have been noticed, his pale face became lit up with a faint blush, in which state of confusion he took his leave.

Conversation was not resumed among the Sinclairs for some minutes after his departure, each, in fact, having been engaged in reflecting upon the surpassing beauty of his face, and the uncommon symmetry of his slender but elegant person. Their impression, indeed, was rather that of wonder than of mere admiration. The tall youth who had just left them seemed, in fact, an incarnation of the beautiful itself—a visionary creation, in which was embodied the ideal spirit of youth, intellect, and grace. His face shone with that rosy light of life’s prime which only glows on the human countenance during the brief period that intervenes between the years of the thoughtless boy and those of the confirmed man: and whilst his white brow beamed with intellect, it was easy to perceive that the fire of deep feeling and high-wrought enthusiasm broke out in timid flashes from his dark eye. His modesty, too, by tempering the full lustre of his beauty, gave to it a character of that graceful diffidence, which above all others makes the deepest impression upon a female heart.

“Well, I do think,” said William Sinclair, “that young Osborne is decidedly the finest boy I ever saw—the most perfect in beauty and figure—and yet we have not seen him to advantage.”

“I think, although I regretted to see him so, that he looked better after he got pale,” said Maria; “his features, though colorless, were cut like marble.”

“I hope his health may not be injured by what has occurred,” observed the second; “he appeared ill.”

“That, Agnes, is more to the point,” said Mr. Sinclair; “I fear the boy is by no means well; and I am apprehensive, from the deep carnation of his cheek, and his subsequent paleness, that he carries within him the seeds of early dissolution. He is too delicate, almost too etherial for earth.”

“If he becomes an angel,” said William, smiling, “with a very slight change, he will put some of them out of countenance.”

“William,” said the father, “never, while you live attempt to be witty at the expense of what is sacred or solemn; such jests harden the heart of him who utters them, and sink his character, not only as a Christian, but as a gentleman.”

“I beg your pardon, father—-I was wrong—but I spoke heedlessly.”

“I know you did, Billy; but in future avoid it. Well, Jane, how is your bird?”

“I think it is better, papa; but one can form no opinion so soon.”

“Go, show it to your mamma—she is the best doctor among us—follow her advice, and no doubt she will add its cure to the other triumphs of her skill.”

“Jane is fretting too much about it,” observed Agnes; “why, Jane, you are just now as pale as young Osborne himself.”

This observation turned the eyes of the family upon her; but scarcely had her sister uttered the words when the young creature’s countenance became the color of crimson, so deeply, and with such evident confusion did she blush. Indeed she felt conscious of this, for she rose, with the wounded dove lying gently between her hands and bosom, and passed, without speaking, out of the room.

“Don’t you think, papa,” observed Miss Sinclair, “that there is a striking resemblance between young Osborne and Jane? I could not help remarking it.”

“There decidedly is, Maria, now that you mentioned it,” said William.

The father paused a little, as if to consider the matter, and then added with a smile—

“It is very singular, Mary; but indeed I think there is—both in the style of their features and their figure.”

“Osborne is too handsome for a man,” observed Agnes; “yet, after all, one can hardly say so, his face, though fine, is not feminine.”

“Beauty, my children!—alas, what is it? Often—too often, a fearful, a fatal gift. It is born with us, and not of our own merit; yet we are vain enough to be proud of it. It is at best a flower that soon fades—a light that soon passes away. Oh! what is it when contrasted with those high principles whose beauty is immortal, which brighten by age, and know neither change nor decay. There is Jane—my poor child—she is indeed very beautiful and graceful, yet I often fear that her beauty, joined as it is to an over-wrought sensibility, may, before her life closes, occasion much sorrow either to herself or others.”

“She is all affection,” said William.

“She is all love, all tenderness, all goodness; and may the grace of her Almighty Father keep her from the wail and woe which too often accompany the path of beauty in this life of vicissitude and trial.”

A tear of affection for his beautiful child stood in the old man’s eyes as he raised them to heaven, and the loving hearts of his family burned with tenderness towards this their youngest and best beloved sister.

The sun had now gone down, and, after a short pause, the old man desired William to summon the other members of the household in to prayers. The evening worship being concluded, the youngsters walked in the lawn before the door until darkness began to set in, after which they retired to their respective apartments for the night.

Sweet and light be your slumbers, O ye that are peaceful and good—sweet be your slumbers on this night so calm and beautiful; for, alas, there is one among you into whose I innocent bosom has stolen that destroying spirit which will yet pale her fair cheek, and wring many a bitter tear from the eyes that love to look upon her. Her early sorrows have commenced this night, and for what mysterious purpose who can divine?—but, alas, alas, her fate is sealed—the fawn of Springvale is stricken, and even now carries in her young heart a wound that will never close.

Osborne’s father, who had succeeded to an estate of one thousand per annum, was the eldest son of a gentleman whose habits were badly calculated to improve the remnant of property which ancestral extravagance had left him.

Ere many years the fragment which came into his possession dwindled into a fraction of its former value, and he found himself With a wife and four children—two sons and two daughters—struggling on a pittance of two hundred a year. This, to a man possessing the feelings and education of a gentleman, amounted to something like retributive justice upon his prodigality. His conflict with poverty, however, (for to him it might be termed such,) was fortunately not of long duration. A younger brother who, finding that he must fight his own battle in life, had embraced the profession of medicine, very seasonably died, and Osborne’s father succeeded to a sum of twelve thousand pounds in the funds, and an income in landed property of seven hundred per annum. He now felt himself more independent than he had ever been, and with this advantage, that his bitter experience of a heartless world had completely cured him of all tendency to extravagance. And now he would have enjoyed as much happiness as is the usual lot of man, were it not that the shadow of death fell upon his house, and cast its cold blight upon his children. Ere three years had elapsed he saw his eldest daughter fade out of life, and in less than two more his eldest son was laid beside her in the same grave. Decline, the poetry of death, in its deadly beauty came upon them, and whilst it sang its song of life and hope to their hearts, treacherously withdrew them to darkness and the worm.

Osborne’s feelings were those of thoughtlessness and extravagance; but he had never been either a libertine or a profligate, although the world forbore not, when it found him humbled in his poverty, to bring such charges against him. In truth, he was full of kindness, and no parent ever loved his children with deeper or more devoted affection. The death of his noble son and beautiful girl brought down his spirit to the most mournful depths of affliction. Still he had two left, and, as it happened, the most beautiful, and more than equally possessed his affections. To them was gradually transferred that melancholy love which the heart of the sorrowing father had carried into the grave of the departed; and alas, it appeared as if it had come back to those who lived loaded with the malady of the dead. The health of the surviving boy became delicate, and by the advice of his physician, who pronounced the air in which they lived unfavorable,—Osborne, on hearing that Mr. Williams, a distant relation, was about to dispose of his house and grounds, immediately became the purchaser. The situation, which had a southern aspect, was dry and healthy, the air pure and genial, and, according to the best medical opinions, highly beneficial to persons of a consumptive habit.

For two years before this—that is since his brother’s death—the health of young Osborne had been watched with all the tender vigilance of affection. A regimen in diet, study and exercise, had been prescribed for him by his physician; the regulations of which he was by no means to transgress.

In fact his parents lived under a sleepless dread of losing him which kept their hearts expanded with that inexpressible and burning love which none but a parent so circumstanced can ever feel. Alas! notwithstanding the promise of life which early years usually hold out, there was much to justify them in this their sad and gloomy apprehension. Woeful was the uncertainty which they felt in discriminating between the natural bloom of youth and the beauty of that fatal malady which they dreaded. His tall slender frame, his transparent cheek, so touching, so unearthly in the fairness of its expression; the delicacy of his whole organization, both mental and physical—all, all, with the terror of decline in their hearts, spoke as much of despair as of hope, and placed the life and death of their beloved boy in an equal poise.

But, independently of his extraordinary personal advantages, all his dispositions were so gentle and affectionate, that it was not I in human nature to entertain harsh feeling toward him. Although modest and shrinking, even to diffidence, he possessed a mind full of intellect and enthusiasm: his imagination, too, overflowed with creative power, and sought the dreamy solitudes of noon, that it might, far from the bustle of life, shadow forth those images of beauty which come thickly only upon those whose hearts are most susceptible of its forms. Many a time has he sat alone upon the brow of a rock or hill, watching the clouds of heaven, or gazing on the setting sun, or communing with the thousand aspects of nature in a thousand moods, his young spirit relaxed into that elysian reverie which, beyond all other kinds of intellectual enjoyment, is the most seductive to a youth of poetic temperament.

There were, indeed, in Osborne’s case, too many of those light and scarcely perceptible tokens which might be traced, if not to a habit of decline, at least to a more than ordinary delicacy of constitution. The short cough, produced by the slightest damp, or the least breath of ungenial air—the varying cheek, now rich as purple, and again pale as a star of heaven—the unsteady pulse, and the nervous sense of uneasiness without a cause—all these might be symptoms of incipient decay, or proofs of those fine impulses which are generally associated with quick sensibility and genius. Still they existed; at one time oppressing the hearts of his parents with fear, and again exalting them with pride. The boy was consequently enjoined to avoid all violent exercise, to keep out of Currents, while heated to drink nothing cold, and above all things never to indulge in the amusement of cold bathing.

Such were the circumstances under which Osbome first appeared to the reader, who may now understand the extent of his alarm on feeling himself so suddenly and seriously affected by his generosity in rescuing the wounded dove. His mere illness on this occasion was a matter of much less anxiety to himself than the alarm which he knew it would occasion his parents and sister. On his reaching home he mentioned the incident which occurred, admitted that he had been rather warm on going into the water, and immediately went to bed. Medical aid was forthwith procured, and although the physician assured them that there appeared nothing serious in his immediate state, yet was his father’s house a house of wail and sorrow.

The next day the Sinclairs, having heard in reply to their inquiries through the servant who had been sent home with his apparel, that he was ill, the worthy clergyman lost no time in paying his parents a visit on the occasion. In this he expressed his regret, and that also of his whole family, that any circumstance relating to them should have been the means, even accidentally, of affecting the young gentleman’s health. It was not, however, until he dwelt upon the occurrence in terms of approbation, and placed the boy’s conduct in a generous light, that he was enabled to appreciate the depth and tenderness of their affection for him. The mother’s tears flowed in silence on hearing this fresh proof of his amiable spirit, and the father, with a foreboding heart, related to Mr. Sinclair the substance of that which we have detailed to the reader.

Such was the incident which brought these two families acquainted, and ultimately ripened their intimacy into friendship.

Much sympathy was felt for young Osborne by the other members of Mr. Sinclair’s household, especially as his modest and unobtrusive deportment, joined to his extraordinary beauty, had made so singularly favorable an impression upon them. Is or was the history of that insidious malady, which had already been so fatal to his sister and brother, calculated to lessen the interest which his first appearance had excited. There was one young heart among them which sank, as if the Weight of death had come over it, on hearing this melancholy account of him whose image was now for ever the star of her fate, whether for happiness or sorrow. From the moment their eyes had met in those few shrinking but flashing glances by which the spirit of love conveys its own secret, she felt the first painful transports of the new affection, and retired to solitude with the arrow that struck her so deeply yet quivering in her bosom.

The case of our fair girl differed widely from that of many young persons, in whose heart the passion of love lurks unknown for a time, throwing its roseate shadows of delight and melancholy over their peace, whilst they themselves feel unable in the beginning to develop those strange sensations which take away from their pillows the unbroken slumber of early life.

Jane from the moment her eyes rested on Osborne felt and was conscious of feeling the influence of a youth so transcendently fascinating. Her love broke not forth gradually like the trembling light that brightens into the purple flush of morning; neither was it fated to sink calm and untroubled like the crimson tints that die only when the veil of night, like the darkness of death, wraps them in its shadow. Alas no, it sprung from her heart in all the noontide strength of maturity—a full-grown passion, incapable of self-restraint, and conscious only of the wild and novel delight arising from its own indulgence. Night and day that graceful form hovered before her, encircled in the halo of her young imagination, with a lustre that sparkled beyond the light of human beauty. We know that the eye when it looks steadily upon a cloudless sun, is incapable for some time afterwards of seeing any other object distinctly; and that in whatever direction it turns that bright image floats incessantly before it—nor will be removed even although the eye itself is closed against its radiance. So was it with Jane. Asleep or awake, in society or in solitude, the vision with which her soul held communion never for a moment withdrew from before her, until at length her very heart became sick, and her fancy entranced, by the excess of her youthful and unrestrained attachment. She could not despair, she could scarcely doubt; for on thinking of the blushing glances so rapidly stolen at herself, and of the dark brilliant eye from whence they came, she knew that the soul of him she loved spoke to her in a language that was mutually understood. These impressions, it is true, were felt in her moments of ecstacy, but then came, notwithstanding this confidence, other moments when maidenly timidity took the crown of rejoicing off her head, and darkened her youthful brow with that uncertainty, which, while it depresses hope, renders the object that is loved a thousand times dearer to the heart.

To others, at the present stage of her affection, she appeared more silent than usual, and evidently fond of solitude, a trait which they had not observed in her before. But these were slight symptoms of what she felt; for alas, the day was soon to come that was to overshadow their hearts forever—never, never more were they and she, in the light of their own innocence, to sing like the morning stars together, or to lay their untroubled heads in the slumbers of the happy.

More than a month had now elapsed since the first appearance of Osborne as one of the dramatis personae of our narrative. A slight fever, attended with less effect upon the lungs than his parents anticipated, had passed off, and he was once more able to go abroad and take exercise in the open air. The two families were now in the habit of visiting each other almost daily; and what tended more and more to draw closer the bonds of good feeling between them, was the fact of the Osbornes being members of the same creed, and attendants at Mr. Sinclair’s place of worship. Jane, while Charles Osborne was yet ill, had felt a childish diminution of her affection for her convalescent dove, whilst at the same time something whispered to her that it possessed a stronger interest in her heart than it had ever done before. This may seem a paradox to such of our readers as have never been in love; but it is not at all irreconcilable to the analogous and often conflicting states of feeling produced by that strange and mysterious passion. The innocent girl was wont, as frequently as she could without exciting notice, to steal away to the garden, or the fields, or the river side, accompanied by her mute, companion, to which with pouting caresses she would address a series of rebukes of having been the means of occasioning the illness of him she loved.

“Alas, Ariel, little do you know, sweet bird, what anxiety you have caused your mistress—if he dies I shall never love you more? Yes, coo, and flutter—but I do not care for you; no, that kiss won’t satisfy me until he is recovered—then I shall be friends with you, and you shall be my own Ariel again.”

She would then pat it petulantly; and the beautiful creature would sink its head, and slightly expand its wings, as if conscious that there was a change of mood in her affection.

But again the innocent remorse of her girlish heart would flow forth in terms of tenderness and endearment; again would I she pat and cherish it; and with the artless I caprice of childhood exclaim—

“No, my own Ariel, the fault was not yours; come, I shall love you—and I will not be angry again; even if you were not good I would love you for his sake. You are now dearer to me a thousand times than you ever were; but alas! Ariel, I am sick, I am sick, and no longer happy. Where is my lightness of heart, my sweet bird, and where, oh where is the joy I used to feel?”

Even this admission, which in the midst of solitude could reach no other human ear, would startle the bashful creature into alarm; and whilst her cheek became alternately pale and crimson at such an avowal thus uttered aloud, she would wipe away the tears that arose to her eyes whenever the depths of her affection were stirred by those pensive broodings which gave its sweetest charm to youthful love.

In thus seeking solitude, it is not to be imagined that our young heroine was drawn thither by a love of contemplating nature in those fresher aspects which present themselves in the stillness of her remote recesses. She sought not for their own sakes the shades of the grove, the murmuring cascade, nor the voice of the hidden rivulet that occasionally stole out from its leafy cover, and ran in music towards the ampler stream of the valley.

No, no; over her heart and eye the spirit of their beauty passed idly and unfelt. All of external life that she had been wont to love and admire gave her pleasure no more. The natural arbors of woodbine, the fairy dells, and the wild flowers that peeped in unknown sweetness about the hedges, the fairy fingers, the blue-bells, the cow-slips, with many others of her fragrant and graceful favorites, all, all, charmed her, alas, no more. Nor at home, where every voice was tenderness, and every word affection, did there exist in her stricken heart that buoyant sense of enjoyment which had made her youth like the music of a brook, where every thing that broke the smoothness of its current only turned it into melody. The morning and evening prayer—the hymn of her sister voices—their simple spirit of tranquil devotion—and the touching solemnity of her father, worshipping God upon the altar of his own heart—all, all this, alas—alas, charmed her no more. Oh, no—no; many motives conspired to send her into solitude, that she might in the sanctity of unreproving nature cherish her affection for the youth whose image was ever, ever before her. At home such was the timid delicacy of her love, that she felt as if its indulgence even in the stillest depths of her own heart, was disturbed by the conversation of her kindred, and the familiar habits of domestic life. Her father’s, her brother’s, and her sisters’ voices, produced in her a feeling of latent shame, which, when she supposed for a moment that they could guess her attachment, filled her with anxiety and confusion. She experienced besides a sense of uneasiness on reflecting that she practiced, for the first time in their presence, a dissimulation so much at variance with the opinion she knew they entertained of her habitual candor. It was, in fact, the first secret she had ever concealed from them; and now the suppression of it in her own bosom made her feel as if she had withdrawn that confidence which was due to the love they bore her. This was what kept her so much in her own room, or sent her abroad to avoid all that had a tendency to repress the indulgence of an attachment that had left in her heart a capacity for no other enjoyment. But in solitude she was far from every thing that could disturb those dreams in which the tranquility of nature never failed to entrance her. There was where the mysterious spirit that raises the soul above the impulses of animal life, mingled with her being—and poured upon her affection the elemental purity of that original love which in the beginning preceded human guilt.

It is, indeed, far from the contamination of society—in the stillness of solitude when the sentiment of love comes abroad before its passion, that the heart can be said to realize the object of its devotion, and to forget that its indulgence can ever be associated with error. This is, truly, the angelic love of youth and innocence; and such was the nature of that which the beautiful girl felt. Indeed, her clay was so divinely tempered, that the veil which covered her pure and ethereal spirit, almost permitted the light within to be visible, and exhibited the workings of a soul that struggled to reach the object whose communion with itself seemed to constitute the sole end of its existence.

The evening on which Jane and Charles Osborne met for the first time, unaccompanied by their friends, was one of those to which the power of neither pen nor pencil can do justice. The sun was slowly sinking among a pile of those soft crimson clouds, behind which fancy is so apt to picture to itself the regions of calm delight that are inhabited by the happy spirits of the blest; the sycamore and hawthorn were yet musical with the hum of bees, busy in securing their evening burthen for the hive. Myriads of winged insects were sporting in the sunbeams; the melancholy plaint of the ringdove came out sweetly from the trees, mingled with the songs of other birds, and the still sweeter voice of some happy groups of children at play in the distance. The light of the hour, in its subdued but golden tone, fell with singular clearness upon all nature, giving to it that tranquil beauty which makes every thing the eye rests upon glide with quiet rapture into the heart. The moth butterflies were fluttering over the meadows, and from the low stretches of softer green rose the thickly-growing grass-stalks, laying their slender ear’s bent with the mellow burthen of wild honey—the ambrosial feast for the lips of innocence and childhood. It was, indeed, an evening when love would bring forth its sweetest memories, and dream itself into those ecstacies of tenderness that flow from the mingled sensations of sadness and delight.

It would be difficult, perhaps impossible, to see on this earth a young creature, whose youth and beauty, and slender grace of person gave her more the appearance of some visionary spirit, too exquisitely ideal for human life. Indeed, she seemed to be tinted with the hues of heaven, and never did a mortal being exist in such fine and harmonious keeping with the scene in which she moved. So light and sylph-like was her figure, though tall, that the eye almost feared she would dissolve from before it, and leave nothing to gaze at but the earth on which she trod. Yet was there still apparent in her something that preserved, with singular power, the delightful reality that she was of humanity, and subject to all those softer influences that breathe their music so sweetly over the chords of the human heart. The delicate bloom of her cheek, shaded away as it was, until it melted into the light that sparkled from her complexion—the snowy forehead, the flashing eye, in which sat the very soul of love—the lips, blushing of sweets—her whole person breathing the warmth of youth, and feeling, and so characteristic in the easiness of its motions of that gracile flexibility that has never been known to exist separate from the power of receiving varied and profound emotions—all this told the spectator, too truly, that the lovely being before him was not of another sphere, but one of the most delightful that ever appeared in this.

But hush!—here is a strain of music! Oh! what lips breathed forth that gush of touching melody which flows in such linked sweetness from the flute of an unseen performer? How soft, how gentle, but oh, how very mournful are the notes! Alas! they are steeped in sorrow, and melt away in the plaintive cadences of despair, until they mingle with silence. Surely, surely, they come from one whose heart has been brought low by the ruined hopes of an unrequited passion. Yes, fair girl, thou at least dost so interpret them; but why this sympathy in one so young? Why is thy bright eye dewy with tears for the imaginary sorrows of another? And again—but ha!—why that flash of delight and terror?—that sudden suffusion of red over thy face and neck—and even now, that paleness like death! Thy heart, thy heart—why does it throb, and why do thy knees totter? Alas! it is even so; the Endymion of thy dreams, as beautiful as even thou thyself in thy purple dawn of womanhood,—he from whom thou now shrinkest, yet whom thou dreadest not to meet, is approaching, and bears in his beauty the charm that will darken thy destiny.

The appearance of Osborne, unaccompanied, taught this young creature to know the full extent of his influence over her. Delight, terror, and utter confusion of thought and feeling, seized upon her the moment he became visible. She wished herself at home, but had not power to go; she blushed, she trembled, and, in the tumult of the moment, lost all presence of mind and self-possession. He had come from behind a hedge, on the path-way along which she walked, and was consequently approaching her, so that it was evident they must meet. On seeing her he ceased to play, paused a moment, and were it not that it might appear cold, and rather remarkable, he, too, would have retraced his steps homewards. In truth, both felt equally confused and equally agitated, for, although such an interview had been, for some time previously, the dearest wish of their hearts, yet would they both almost have felt relieved, had they had an opportunity of then escaping it. Their first words were uttered in a low, hesitating voice, amid pauses occasioned by the necessity of collecting their scattered thoughts, and with countenances deeply blushing from a consciousness of what they felt. Osborne turned back, mechanically, and accompanied her in her walk. After this there was a silence for some time, for neither had courage to renew the conversation. At length Osborne, in a faltering voice addressed her:

“Your dove,” said he, “is quite recovered, I presume.”

“Oh, yes,” she replied, “it is perfectly well again.”

“It is an exceedingly beautiful bird, and remarkably docile.”

“I have had little difficulty in training it,” she returned, and then added, very timidly, “it is also very affectionate.”

The youth’s eyes sparkled, as if he were about to indulge in some observation suggested by her reply, but, fearing to give it expression, he paused again; in a few minutes, however, he added—

“I think there is nothing that gives one so perfect an idea of purity and innocence as a snow-white dove, unless I except a young and beautiful girl, such as—”

He glanced at her as he spoke, and their eyes met, but in less than a moment they were withdrawn, and cast upon the earth.

“And of meekness and holiness too,” she observed, after a little.

“True; but perhaps I ought to make another exception,” he added, alluding to the term by which she herself was then generally known. As he spoke, his voice expressed considerable hesitation.

“Another exception,” she answered, inquiringly, “it would be difficult, I think, to find any other emblem of innocence so appropriate as a dove.”

“Is not a Fawn still more so,” he replied, “it is so gentle and meek, and its motions are so full of grace and timidity, and beauty. Indeed I do not wonder, when an individual of your sex resembles it in the qualities I have mentioned, that the name is sometimes applied to her.”

The tell-tale cheek of the girl blushed a recognition of the compliment implied in the words, and after a short silence, she said, in a tone that was any thing but indifferent, and with a view of changing the conversation—

“I hope you are quite recovered from your illness.”

“With the exception of a very slight cough, I am,” he replied.

“I think,” she observed, “that you look somewhat paler than you did.”

“That paleness does not proceed from indisposition, but from a far different”—he paused again, and looked evidently abashed. In the course of a minute, however, he added, “yes, I know I am pale, but not because I am unwell, for my health is nearly, if not altogether, restored, but because I am unhappy.”

“Strange,” said Jane, “to see one unhappy at your years.”

“I think I know my own character and disposition well,” he replied; “my temperament is naturally a melancholy one; the frame of my mind is like that of my body, very delicate, and capable of being affected by a thousand slight influences which pass over hearts of a stronger mould, without ever being felt. Life to me, I know, will be productive of much pain, and much enjoyment, while its tenure lasts, but that, indeed, will not be long. My sands are measured, for I feel a presentiment, a mournful and prophetic impression, that I am doomed to go down into an early grave.”

The tone of passionate enthusiasm which pervaded these words, uttered as they were in a voice wherein pathos and melody were equally blended, appeared to be almost too much for a creature whose sympathy in all his moods and feelings was then so deep and congenial. She felt some difficulty in repressing her tears, and said, in a voice which no effort could keep firm.

“You ought not to indulge in those gloomy forebodings; you should struggle against them, otherwise they will distress your mind, and injure your health.”

“Oh, you do not know,” he proceeded, his eyes sparkling with that light which is so often the beacon of death—“you do not know the fatal fascination by which a mind, set to the sorrows of a melancholy temperament, is charmed out of its strength. But no matter how dark may be my dreams—there is one light for ever upon them—one image ever, ever before me—one figure of grace and beauty—oh, how could I deny myself the contemplation of a vision that pours into my soul a portion of itself, and effaces: every other object but an entrancing sense of its own presence. I cannot, I cannot—it bears me away into a happiness that is full of sadness—where I indulge alone, without knowing why, in my feast of tears’—happy! happy! so I think, and so I feel; yet why is my heart sunk, and why are all my visions filled with death and the grave?”

“Oh, do not talk so frequently of death,” replied the beautiful girl, “surely you need not fear it for a long while. This morbid tone of mind will pass away when you grow into better health and strength.”

“Is not this hour calm?” said he, flashing his dark eyes full upon her, “see how beautiful the sun sinks in the west;—alas! so I should wish to die—as calm, and the moral lustre of my life as radiant.”

“And so you shall,” said Jane, in a voice full of that delightful spirit of consolation which, proceeding from such lips, breathes the most affecting power of sympathy, “so you shall, but like him, not until after the close of a long and well-spent life.”

“That—that,” said he, “was only a passing thought. Yes, the hour is calm, but even in such stillness, do you not observe that the aspen there to our left, this moment quivers to the breezes which we cannot feel, and by which not a leaf of any other tree about us is stirred—such I know myself to be, an aspen among men, stirred into joy or sorrow, whilst the hearts of others are at rest. Oh, how can my foretaste of life be either bright or cheerful, for when I am capable of being moved by the very breathings of passion, what must I not feel in the blast, and in the storm—even now, even now!”—The boy, here overcome by the force of his own melancholy enthusiasm, paused abruptly, and Jane, after several attempts to speak, at last said, in a voice scarcely audible—

“Is not hope always better than despair?”

Osborne instantly fixed his eyes upon her, and saw, that although her’s were bent upon the earth, her face had become overspread with a deep blush. While he looked she raised them, but after a single glance, at once quick and timid, she withdrew them again, a still deeper blush mantling on her cheek. He now felt a sudden thrill of rapture fall upon his heart, and rush, almost like a suffocating sensation, to his throat; his being became for a moment raised to an ecstacy too intense for the power of description to portray, and, were it not for the fear which ever accompanies the disclosure of first and youthful love, the tears of exulting delight would have streamed down his cheeks.

Both had reached a little fairy dell of vivid green, concealed by trees on every side, and in the middle of which rose a large yew, around whose trunk had been built a seat of natural turf whereon those who strolled about the ground might rest, when heated or fatigued by exercise or the sun. Here the girl sat down.

A change had now come over both. The gloom of the boy’s temperament was gone, and his spirit caught its mood from that of his companion. Each at the moment breathed the low, anxious, and tender timidity of love, in it purest character. The souls of both vibrated to each other, and felt depressed with that sweetest emotion which derives all its power from the consciousness that its participation is mutual. Osborne spoke low, and his voice trembled; the girl was silent, but her bosom panted, and her frame shook from head to foot. At length, Osborne spoke.

“I sometimes sit here alone, and amuse myself with my flute; but of late—of late—I can hear no music that is not melancholy.”

“I, too, prefer mournful—mournful music,” replied Jane. “That was a beautiful air you played just now.”

Osborne put the flute to his lips, and commenced playing over again the air she had praised; but, on glancing at the fair girl, he perceived her eyes fixed upon him with a look of such deep and devoted passion as utterly overcame him. Her eyes, as before, were immediately withdrawn, but there dwelt again upon her burning cheek such a consciousness of her love as could not, for a moment, be mistaken. In fact she betrayed all the confused symptoms of one who felt that the state of her heart had been discovered. Osborne ceased playing; for such was his agitation that he scarcely knew what he thought or did.

“I cannot go on,” said he in a voice which equally betrayed the state of his heart; “I cannot play;” and at the same time he seated himself beside her.

Jane rose as he spoke, and in a broken voice, full of an expression like distress, said hastily:

“It is time I should go;—I am,—I am too long out.”

Osborne caught her hand, and in words that burned with the deep and melting contagion of his passion, said simply:

“Do not go:—oh do not yet go!”

She looked full upon him, and perceived that as he spoke his face became deadly pale, as if her words were to seal his happiness or misery.

“Oh do not leave me now,” he pleaded; “do not go, and my life may yet be happy.”

“I must,” she replied, with great difficulty; “I cannot stay; I do not wish you to be unhappy;” and whilst saying this, the tears that ran in silence down her cheeks proved too clearly how dear his happiness must ever be to her.

Osborne’s arm glided round her waist, and she resumed her seat,—or rather tottered into it.

“You are in tears,” he exclaimed. “Oh could it be true! Is it not, my beloved girl? It is—it is—love! Oh surely, surely it must—it must!”

She sobbed aloud once or twice; and, as he kissed her unresisting lips, she murmured out, “It is; it is; I love you.”

Oh life! how dark and unfathomable are thy mysteries! And why is it that thou permittest the course of true love, like this, so seldom to run smooth, when so many who, uniting through the impulse of sordid passion, sink into a state of obtuse indifference, over which the lights and shadows that touch thee into thy finest perceptions of enjoyment pass in vain.

It is a singular fact, but no less true than singular, that since the world began there never was known any instance of an anxiety, on the part of youthful lovers, to prolong to an immoderate extent the scene in which the first mutual avowal of their passions takes place. The excitement is too profound, and the waste of those delicate spirits, which are expended in such interviews, is much too great to permit the soul to bear such an excess of happiness long. Independently of this, there is associated with it an ultimate enjoyment, for which the lovers immediately fly to solitude; there, in the certainty of waking bliss, to think over and over again of all that has occurred between them, and to luxuriate in the conviction, that at length the heart has not another wish, but sinks into the solitary charm which expands it with such a sense of rapturous and exulting delight.

The interview between our lovers was, consequently, not long. The secret of their hearts being now known, each felt anxious to retire, and to look with a miser’s ecstacy upon the delicious hoard which the scene we have just described had created. Jane did not reach home until the evening devotions of the family were over, and this was the first time she had ever, to their knowledge, been absent from them before. Borne away by the force of what had just occurred, she was proceeding up to her own room, after reaching home, when Mr. Sinclair, who had remarked her absence, desired that she be called into the drawing-room.

“It is the first neglect,” he observed, “of a necessary duty, and it would be wrong in me to let it pass without at least pointing it out to the dear child as an error, and knowing from her own lips why it has happened.”

Terror and alarm, like what might be supposed to arise from the detection of secret guilt, seized upon the young creature so violently that she had hardly strength to enter the drawing-room without support: her face became the image of death, and her whole frame tottered and trembled visibly.

“Jane, my dear, why were you absent from prayers this evening?” inquired her father, with his usual mildness of manner.

This question, to one who had never yet been, in the slightest instance, guilty of falsehood, was indeed a terrible one; and especially to a girl so extremely timid as was this his best beloved daughter.

“Papa,” she at last replied, “I was out walking;” but as she spoke there was that in her voice and manner which betrayed the guilt of an insincere reply.

“I know, my dear, you were; but although you have frequently been out walking, yet I do not remember that you ever stayed, away from our evening worship before. Why is this?”

Her father’s question was repeated in vain. She hung her head and returned no answer. She tried to speak, but from her parched lips not a word could proceed. She felt as if all the family that moment were conscious of the occurrence between her and her lover; and if the wish could have relieved her, she would almost have wished to die, so much did she shrink abashed in their presence.

“Tell me, my daughter,” proceeded her father, more seriously, “has your absence been occasioned by anything that you are ashamed or afraid to mention? From me, Jane, you ought to have no secrets;—you are yet too young to think away from your father’s heart and from your mother’s also;—speak candidly, my child,—speak candidly,—I expect it.”

As he uttered the last words, the head of their beautiful flower sank upon her bosom, and in a moment she lay insensible upon the sofa on which she had been sitting.

This was a shock for which neither the father nor the family were prepared. William flew to her,—all of them crowded about her, and scarcely had he raised that face so pale, but now so mournfully beautiful in its insensibility, when her mother and sisters burst into tears and wailings, for they feared at the moment that their beloved one must have been previously seized with sudden illness, and was then either taken, or about to be taken from their eyes for ever. By the coolness of her father, however, they were directed how to restore her, in which, after a lapse of not less than ten minutes, they succeeded.

When she recovered, her mother folded her in her arms, and her sisters embraced her with tenderness and tears. Her father then gently caught her hand in his, and said with much affection:

“Jane, my child, you are ill. Why not have told us so?”

The beautiful girl knelt before him for a moment, but again rose up, and hiding her head in his bosom, exclaimed—weeping—

“Papa, bless me, oh, bless me, and forgive me.”

“I do; I do,” said the old man; and as he spoke a few large tears trickled down his cheeks, and fell upon her golden locks.

It is a singular fact, but one which we know to be true, that not only the affection of parents, but that of brothers and sisters, goes down with greater tenderness to the youngest of the family, all other circumstances being equal. This is so universally felt and known, that it requires no further illustration from us. At home, Jane Sinclair was loved more devotedly in consequence of being the most innocent and beautiful of her father’s children; in addition to this, however, she was cherished with that peculiar sensibility of attachment by which the human heart is always swayed towards its youngest and its last.

On witnessing her father’s tenderness, she concealed her face in his bosom, and wept for some time in silence, and by a gentle pressure of her delicate arms, as they encircled his neck, intimated her sense of his affectionate indulgence towards her; and perhaps, could it have been understood, a tacit acknowledgment of her own unworthiness on that occasion to receive it.

At length, she said, after an effort to suppress her tears, “Papa, I will go to bed.”

“Do, my love; and Jane, forget not to address the Throne of God before you sleep.”

“I did not intend to neglect it, papa. Mamma, come with me.” She then kissed her sisters and bade good-night to William; after which she withdrew, accompanied by her mother, whilst the eyes of those who remained were fixed upon her with love and pride and admiration.

“Mamma,” said she, when they reached the apartment, “allow me to sleep alone tonight.”

“Jane, your mind appears to be depressed, darling,” replied her mother; “has anything disturbed you, or are you really ill?”

“I am quite well, mamma, and not at all depressed; but do allow me to sleep in the closet bed.”

“No, my dear, Agnes will sleep there, and you can sleep in your own as usual; the poor girl will wonder why you leave her, Jane; she will feel so lonely, too.”

“But, mamma, it would gratify me very much, at least for this night. I never wished to sleep away from Agnes before; and I am certain she will excuse me when she knows I prefer it.”

“Well, my love, of course Jean have no objection; I only fear you are not so well as you imagine yourself. At all events, Jane, remember your father’s advice to pray to God; and remember this, besides, that from me at least you ought to have no secrets. Good-night, dear, and may the Lord take care of you!”

She then kissed her with an emotion of sorrow for which she could scarcely account, and passed down to the room wherein the other members of the family were assembled.

“I know not what is wrong with her,” she observed, in reply to their enquiries. “She declares she is perfectly well, and that her mind is not at all depressed.”

“In that I agree with her,” said William; “her eye occasionally sparkled with something that resembled joy more than depression.”

“She begged of me to let her sleep alone to-night,” continued the mother; “so that you, Agnes, must lie in the closet bed.”

“She must, certainly, be unwell then,” replied Agnes, “or she would hardly leave me. Indeed I know that her spirits have not been so good of late as usual. Formerly we used to chat ourselves asleep, but for some weeks past she has been quite changed, and seldom spoke at all after going to bed. Neither did she sleep so well latterly as she used to.”

“She is, indeed, a delicate flower,” observed her father, “and a very slight blast, poor thing, will make her droop—droop perhaps into an early grave!”

“Do not speak so gloomily, my dear Henry,” said her mother. “What is there in her particular case to justify any such apprehension?”

“Her health has been always good, too,” observed Maria; “but the fact is, we love her so affectionately that many things disturb us about her which we would never feel if we loved her less.”

“Mary,” said her father, “you have in a few words expressed the true state of our feelings with respect to the dear child. We shall find her, I trust, in good health and spirits in the morning; and please the Divine Will, all will again be well—but what’s the matter with you, Agnes?”

Mr. Sinclair had, a moment before, observed that an expression of thought, blended with sorrow, overshadowed the face of his second daughter. The girl, on hearing her father’s enquiry, looked mournfully upon him, whilst the tears ran silently down her cheeks.

“I will go to her,” said she, “and stay with her if she lets me. Oh, papa, why talk of an early grave for her? How could we lose her? I could not—and I cannot bear even to think of it.”

She instantly rose and proceeded to Jane’s room, but in a few minutes returned, saying, “I found her at prayers, papa.”

“God bless her, God bless her! I knew she would not voluntarily neglect so sacred a duty. As she wishes to be alone, it is better not to disturb her; solitude and quiet will no doubt contribute to her composure, and it is probably for this purpose that she wishes to be left to herself.”

After this the family soon retired to bed, with the exception of Mr. Sinclair himself, who, contrary to his practice, remained for a considerable time longer up than usual. It appeared, indeed, as if the shadow of some coming calamity had fallen upon their hearts, or that the affection they had entertained for her was so mysteriously deep as to produce that prophetic sympathy which is often known to operate in a presentiment of sorrow that never fails to be followed by disaster. It is difficult to account for this singular succession of cause to effect, as they act upon our emotions, except probably by supposing that it is an unconscious development of those latent faculties which are decreed to expand into a full growth in a future state of existence. Be this as it may, these loving relatives experienced upon that night a mood of mind such as they had never before known, even when the hand of death had taken a brother and sister from among them. It was not grief but a wild kind of dread, slight it is true, but distinct in its character, and not dissimilar to that fear which falls upon the spirits during one of those glooms that precede some dark and awful convulsion of nature. Her father remained up, as we have said, longer than the rest, and in the silence which succeeded their retirement for the night, his voice could be occasionally heard in deep and earnest supplication. It was evident that he had recourse to prayer; and by some of the expressions caught from time to time, they gathered that “his dear child,” and “her peace of mind” were the object of the foreboding father’s devotions.

Jane’s distress, at concealing the cause of her absence from prayers, though acute at the moment of enquiry, was nevertheless more transient than one might suppose from the alarming effects it produced. Her mind was at the time in a state of tumult and excitement, such as she had never till then experienced, and the novel guilt of dissimulation, by superinducing her first impression of deliberate crime, opposed itself so powerfully to the exulting sense of her newborn happiness, that both produced a shock of conflicting emotions which a young mind, already so much exhausted, could not resist. She felt, therefore, that a strange darkness shrouded her intellect, in which all distinct traces of thought, and all memory of the past were momentarily lost. Her frame, too, at the best but slender and much enfeebled by the preceding interview with Osborne, and her present embarrassment, could not bear up against this chaotic struggle between delight and pain. It was, no doubt, impossible for her relatives to comprehend all this, and hence their alarm. She was too pure and artless to be suspected of concealing the truth; and they consequently entertained not the slightest suspicion of that kind; but still their affections were aroused, and what might have terminated in an ordinary manner, ended in that unusual mood we have described.