The Project Gutenberg EBook of William Morris, by Elizabeth Luther Cary

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: William Morris

Poet, Craftsman, Socialist

Author: Elizabeth Luther Cary

Release Date: May 18, 2012 [EBook #39725]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WILLIAM MORRIS ***

Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive.)

William Morris

Copyright, 1902

BY

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

Published, October, 1902

Reprinted, June, 1903; December, 1905

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

The personal life of William Morris is already known to us through Mr. Mackail’s admirable biography as fully, probably, as we shall ever know it. My own endeavour has been to present a picture of Morris’s busy career perhaps not less vivid for the absence of much detail, and showing only the man and his work as they appeared to the outer public.

I have used as a basis for my narrative, the volumes by Mr. Mackail; William Morris, his Art, his Writings, and his Public Life, by Aymer Vallance; The Books of William Morris, by H. Buxton Forman; numerous articles in periodicals, and Morris’s own varied works.

I wish to express my indebtedness to Mr. Bulkley of 42 East 14th Street, New York City, for permission to reproduce a number of Morris patterns in his possession, notably a fragment of the St. James’s wall-paper.

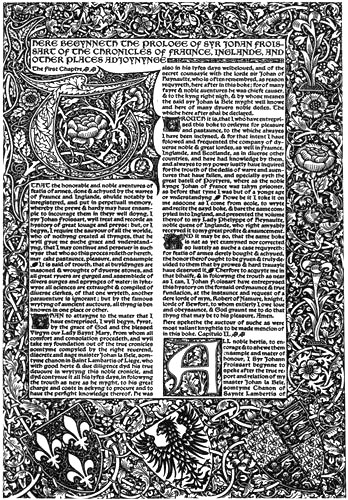

Much material for the letter-press and for the illustrations I have obtained through the Boston Public[Pg iv] Library. The Froissart pages were found there and most of the Kelmscott publications from which I have quoted.

The bibliography is that prepared by Mr. S. C. Cockerell for the last volume of Mr. Morris issued by the Kelmscott Press, under the title of A Note by William Morris on His Aims in Founding the Kelmscott Press. To the Cockerell bibliography have been added a few notes of my own.

E. L. C.

Brooklyn, Sept. 10, 1902.

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I.— | Boyhood | 1 |

| II.— | Oxford Life | 21 |

| III.— | From Rossetti to the Red House | 46 |

| IV.— | Morris and Company | 69 |

| V.— | From the Red House to Kelmscott | 96 |

| VI.— | Poetry | 114 |

| VII.— | Public Life and Socialism | 146 |

| VIII.— | Public Life and Socialism (Continued) | 174 |

| IX.— | Literature of the Socialist Period | 194 |

| X.— | The Kelmscott Press | 219 |

| XI.— | Later Writings | 239 |

| XII.— | The End | 255 |

| Bibliography | 269 | |

| Index | 291 |

ILLUSTRATIONS.

| Page | |

| William Morris From Life. |

Frontispiece |

| Title-page of “The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine” | 32 |

| Portrait of Rossetti By Watts. |

36 |

| Illustration by Rossetti to “The Lady of Shalott” in the Moxon “Tennyson.” The Head of Launcelot is a Portrait of Morris |

42 |

| Portrait of Jane Burden (Mrs. Morris) By Rossetti |

58 |

| Wall-Paper and Cotton-Print Designs | 60 |

| “Acanthus” Wall-Paper | |

| “Pimpernel” Wall-Paper | |

| “African Marigold” Cotton-Print | |

| “These designs must not be taken as exact as to colour afterwards used, Mr. Morris using the colours to his hand and afterwards superintending the actual colouring in the course of manufacture, in most cases many experimental trials being made before the desired colouring was actually decided upon.” | |

| Reproduced from examples obtained by courtesy of Mr. A. E. Bulkley. | |

| The Morris designs in this book were reproduced by permission of Messrs. Morris & Company. | |

| [Pg viii]“The Strawberry Thief” Design for Cotton-Print | 66 |

| Tulip Design for Axminster Carpet | 70 |

| Peacock Design for Coarse Wool Hangings | 72 |

| Painted Wall Decoration Designed by Morris | 76 |

| Painted Wall Decoration Designed by Morris | 80 |

| Design for St. James’s Palace Wall-Paper Reproduced from sample obtained through courtesy of Mr. Bulkley. |

82 |

| Early Design for Morris Wall-Paper “Daisy and Columbine” | 84 |

| Chrysanthemum Design for Wall-Paper | 84 |

| Anemone Pattern for Silk and Wool Curtain Material | 88 |

| Portion of Hammersmith Carpet | 90 |

| Secretary Designed by the Morris Co. In possession of Mr. Bulkley. |

94 |

| Sofa Designed by the Morris Co. In possession of Mr. Bulkley. |

94 |

| Illustration by Burne-Jones for Projected Edition of “The Earthly Paradise,”

Cut on Wood by Morris Himself |

98 |

| Kelmscott Manor House. Two views | 100 |

| Design by Rossetti for Window Executed by Morris & Co. (“The Parable of the Vineyard”) |

110 |

| Design by Rossetti for Stained-Glass Window Executed by the Morris Co.

(“The Parable of the Vineyard”) |

110 |

| [Pg ix]Morris’s Bed, with Hangings Designed by Himself and Embroidered by his

Daughter |

114 |

| Kelmscott Manor House from the Orchard | 118 |

| Portrait of Edward Burne-Jones By Watts. |

120 |

| William Morris | 130 |

| Picture by Rossetti in which the Children’s Faces are Portraits of May Morris | 148 |

| Honeysuckle Design for Linen | 162 |

| Washing Cloth at the Merton Abbey Works | 174 |

| Merton Abbey Works | 174 |

| Portrait of Mrs. Morris By Rossetti. |

200 |

| Study of Mrs. Morris Made by Rossetti for picture called “The Day Dream.” |

216 |

| Kelmscott Types | 220 |

| Page from Kelmscott “Chaucer.” Illustration by Burne-Jones. Border and Initial Letter by Morris |

222 |

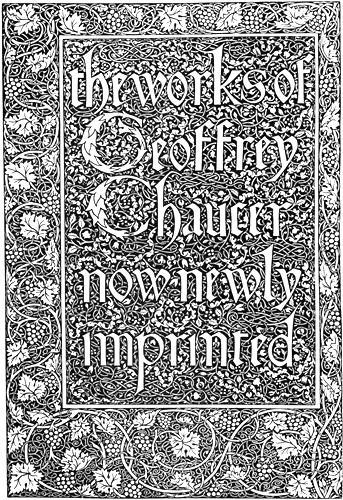

| Title-page of the Kelmscott “Chaucer” | 224 |

| The Smaller Kelmscott Press-Mark | 228 |

| The Larger Kelmscott Press-Mark | 228 |

| Drawing by Morris of the Letter “h” for Kelmscott Type, with Notes and Corrections |

228 |

| Specimen Page from the Kelmscott “Froissart” Projected Edition |

234 |

BOYHOOD.

There is, perhaps, no single work by William Morris that stands out as a masterpiece in evidence of his individual genius. He was not impelled to give peculiar expression to his own personality. His writing was seldom emotionally autobiographic as Rossetti’s always was, his painting and designing were not the expression of a personal mood as was the case with Burne-Jones. But no one of his special time and group gave himself more fully or more freely for others. No one contributed more generously to the public pleasure and enlightenment. No one tried with more persistent effort first to create and then to satisfy a taste for the possible best in the lives and homes of the people. He worked toward this end in so many directions that a lesser energy than his must have been dissipated and a weaker purpose rendered impotent. His tremendous vitality saved him from the most humiliating of failures, the failure to make good extravagant promise. He never lost sight of the result in the[Pg 2] endeavour, and his discontent with existing mediocrity was neither formless nor empty. It was the motive power of all his labour; he was always trying to make everything “something different from what it was,” and this instinct was, alike for strength and weakness, says his chief biographer, “of the very essence of his nature.” To tell the story of his life is to write down the record of dreams made real, of nebulous theories brought swiftly to the test of experiment, of the spirit of the distant past reincarnated in the present. But, as with most natures of similar mould, the man was greater than any part of his work, and even greater than the sum of it all. He remains one of the not-to-be-forgotten figures of the nineteenth century, so interesting was he, so impressive, so simple-hearted, so nearly adequate to the great tasks he set himself, so well beloved by his companions, so useful, despite his blunders, to society at large.

The unity that held together his manifold forms of expression was maintained through the different periods of his life, making him a “whole man” to a more than usual degree. From the earliest recorded incidents of his childhood we gain an impression not unlike that made by his latest years, and by all the interval between. The very opposite of Rossetti, with whose “school” he has been so long and so mistakenly identified, his nature was as single as his accomplishment was complex, and the only means by which it is possible to get a just idea of both the[Pg 3] former and the latter is to regard him as a man of one preoccupation amounting to an obsession, the reconstruction of social and industrial life according to an ideal based upon the more poetic aspects of the Middle Ages. From first to last the early English world, the English world of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, was the world to which he belonged. “Born out of his due time,” in truth, he began almost from his birth to accumulate associations with the time to which he should have been native and whose far off splendour lured him constantly back toward it.

The third of nine children, he was born at Walthamstow, in Essex, England, on the 24th of March, 1834. On the Morris side he came of Welsh ancestry, a fact accounting perhaps for the mingled gloom and romance of his temperament. His father was a discount broker in opulent circumstances, and his mother was descended from a family of prosperous merchants and landed proprietors. On the maternal side a strong talent for music existed, but in the Morris family no more artistic quality can be traced than a devotion to general excellence, to which William Morris certainly fell heir. For a time he was a sickly child, and used the opportunity to advance his reading, being “already deep in the Waverley novels” when four years old, and having gone through these and many others before he was seven.

In 1840 the family removed to Woodford Hall, a house belonging to the Georgian period, standing in[Pg 4] about fifty acres of park, on the road from London to Epping, and here Morris led an outdoor life with the result of rapidly establishing his health, steeping mind and sense in the sights and sounds of nature dear to him forever after, and gaining intimate acquaintance with the romantic and mediæval surroundings by which his whole career was to be influenced. The county of Essex was well adapted to feed his prodigious appetite for antiquities. Its churches, in numbers of which Norman masonry is to be found, its ancient brasses (that of the schoolboy Thomas Heron being among many others within easy reach of Woodford), and its tapestry-hung houses, all stimulated his inborn love of the Middle Ages and started him fairly on that path through the thirteenth century which he followed deviously as long as he lived. Even in his own home, we are told, certain of the habits of mediæval England persisted, such as the brewing of beer, the meal of cakes and ale at “high prime,” the keeping of Twelfth Night, and other such festivals. The places he lived in counted for much with him always, and the impressions of this childish period remained, like all his later impressions, keen and permanent. Toward the end of his life he printed at the Kelmscott Press the carol Good King Wenceslas, which begins with a lusty freshness:

Good King Wenceslas look’d out,

On the feast of Stephen,

[Pg 5]When the snow lay round about,

Deep and crisp and even.

Brightly shone the moon that night,

Though the frost was cruel,

When a poor man came in sight

Gath’ring winter fuel.

“The legend itself,” he comments, “is a pleasing and genuine one, and the Christmas-like quality of it, recalling the times of my boyhood, appeals to me at least as a memory of past days.”

Beside angling, shooting, and riding, he very early occupied much of his time with visits to the old churches, a pursuit of which he was never to weary, studying their monuments and accumulating an amount of genuine erudition concerning them quite out of proportion to his rather moderate accomplishment along the ordinary lines of study. At an age when Scott was scouring his native heath in search of Border ballads and antiquities, this almost equally precocious boy was collecting rubbings from ancient inscriptions, and picturing to himself, as he wandered about the region of his home on foot or on horseback, the lovely face of England as it looked in the thirteenth or fourteenth century. In one of the earliest of the boyish romances that appeared in the Oxford and Cambridge Magazine, he imagines himself the master-mason of a church built more than six centuries before, and which has vanished from the face of the earth with nothing to indicate its existence save earth-covered ruins “heaving the yellow corn into glorious waves.” His description[Pg 6] of the carving on the bas-reliefs of the west front and on the tombs shows with what loving intensity he has studied the most minute details of the work of the ancient builders in whose footsteps he would have rejoiced much to tread. How far his family sympathised with his tastes it is impossible to say, but probably not deeply. We have few hints of the personal side of his home-life; we know that a visit to Canterbury Cathedral with his father was among the indelible experiences of his first decade, and that he possessed among his toys a little suit of armour in which he rode about the park after the manner of a Froissart knight, and that is about all we do know until we hear of the strong disapproval of his mother and one of his sisters for the career that finally diverted his interest from the Church for which they had designed him.

His formal education began when he was sent at the age of nine to a preparatory school kept by a couple of maiden ladies. There he remained until the death of his father in 1847. In February, 1848, he went to Marlborough College, a nomination to which his father had purchased for him. The best that can be said for this school seems to be that it was situated in a part of England ideally suited to a boy of archæological tastes, and was provided with an excellent archæological and architectural library. Here his eager mind browsed on the literature of English Gothic, and his restless feet carried him far afield among pre-Celtic barrows, stone circles, and[Pg 7] Roman villas. Savernake Forest was close at hand and he spent many of his holidays within it. It was doubtless the familiarity with all aspects of the woods, due to his pilgrimages through Savernake and Epping Forests and the long roving days idled away among their shadows, that gave rise to the allusions in his books—early and late—to woodland life. The passage through the thick wood and the coming at last to the place where the trees thin out and the light begins to shimmer through them is a constantly recurring figure of his verse and of his prose. Frequently the important scene of a romance or of a long poem is laid in a wildwood, as in the story entitled The Wood beyond the World, or in Goldilocks and Goldilocks, the concluding poem of the volume of Poems by the Way, in which the great grey boles of the trees, the bramble bush, the “woodlawn clear,” and the cherished oaks are as vivid as the human actors in the drama. His heroes seldom fail of being deft woodsmen, able to thread the tangle of underbrush by blind paths, and observant of all the common sights and sounds of the woodland, rabbits scuttling out of the grass, adders sunning themselves on stones in the cleared spaces, wild swine running grunting toward close covert, hart and hind bounding across the way. They know the musty savour of water dipped from a forest brook, they know how to go straight to the yew sticks that quarter best for bow-staves, they know the feeling of the boggy moss under their feet, and the sound of[Pg 8] the “iron wind” through the branches in the depth of winter; there is no detail of wild wood life of which they are ignorant. This intimacy with Nature in her most secluded moments, in her shyest and most mysterious aspect, forms an element of inexpressible charm in the lovely backgrounds against which Morris delighted to place his visionary figures. He never tired of combining the impressions stored away in his mind on his boyish rambles into pictures the delicate beauty of which can hardly be overestimated.

While he was at school, his already highly developed imagination found an outlet in constant fable-making, his tales of knights and fairies and miraculous adventures having a considerable popularity among his comrades, with whom, however, he himself was not especially popular, making friends with them only in a superficial fashion. Judging from the autobiographic fragments occasionally found in his work, he was a boy of many moods, most of them tinged with the self-conscious melancholy of his early poetry. Sentiment was strong with him, and a peculiar reticence or detachment of temperament kept him independent of others during his school years, and apparently uninfluenced by the tastes or opinions of those about him, if we except the case of his Anglo-Catholic proclivities, which obviously were fed by the tendencies of the school, but which, so far from diverting him from the general scheme of his individual interests, fitted into them[Pg 9] and served him as another link between the present and the much preferred past.

Outwardly he can hardly have seemed the typical dreamer he has described himself as being. Beautiful of feature, of sturdy build, with a shouting voice, extraordinary muscular strength, and a gusty temper, he impressed himself upon his comrades chiefly by his impetuosity in the energetic game of singlestick, by the surplus vigour that led him at times to punch his own head with all his might to “take it out of himself,” and by the vehemence and enthusiasm of his argumentative talk.

He was little of a student along the orthodox lines, and Marlborough College was not calculated to increase his respect—never undue—for pedagogic methods. A letter written when he was sixteen to his eldest and favourite sister reflects quite fully his pre-occupations. It has none of the genuine wit and literary tone of the juvenile letter written by Stevenson to his father, presenting his claims for reimbursements. It shows no such zest for bookish pursuits as Rossetti’s letters, written at the same age, reveal. But it is entirely free from the shallow flippancy that frequently characterises the correspondence of a young man’s second decade—that characterised Lowell’s, for example, to an almost painful degree; nor has it a shade of the self-magnification to which any amount of flippancy is preferable. It is straightforward and boyish, and remarkable only as showing the thorough and intelligent method[Pg 10] with which its writer followed up whatever commanded his interest. Commencing with the description of an anthem sung at Easter by the trained choir of Blore’s Chapel connected with his school, he passes on to an account of his archæological investigations, giving after his characteristic fashion all the small details necessary to enable his correspondent to form a definite picture of the places he had visited. After he had made one pilgrimage to the Druidical circle and Roman entrenchment at Avebury, he had learned of the peculiar method of placing the stones which, from the dislocated condition of the ruins, had not been obvious to him. Therefore he had returned on the following day to study it out and fix the original arrangement firmly in his imagination, and, at the time of writing the letter, was able to explain it quite clearly, a result, derived from the expenditure of two holidays, that was completely satisfactory to him. He winds up with a purely boyish plea for a “good large cake” and some biscuit in addition to a cheese that had been promised him, and for paper and postage stamps and his silkworm eggs and a pen box to be sent him from home.

At school he was “always thinking about home,” and when the family moved again to Walthamstow, within a short distance of his first home, and to a house boasting a moat and a wooded island, he was eagerly responsive to the poetic suggestions conveyed by these romantic accessories. When at the[Pg 11] end of 1851 he left school to prepare under a private tutor for Oxford, he renewed his early familiarity with Epping Forest and spent most of his holidays among the trees that had not apparently changed since the time of Edward the Confessor. The great age of the wood and its peculiarly English character made a profound impression upon him, and it is easy to imagine the fury with which he must have received the suggestion, made forty years later by Mr. Alfred Wallace, that in place of “a hideous assemblage of stunted mop-like pollards rising from a thicket of scrubby bushes,” North American trees should be planted and a part of the forest made into an “almost exact copy” of North American woodland. Indeed, a suppressed but unmistakable fury breathes from the letters written to the Daily Chronicle, as late as 1895, regarding the tree-felling that was going on ruthlessly in the forest, destroying its native character and individual charm. These letters, curiously recalling those written half a century before concerning boyish excursions through the same region, are well worth quoting here, where properly they belong, as they are inspired by the earliest of the associations and ideals cherished by Morris to the end of his life. They are fine examples of his own native character in argument, his humbly didactic tone early caught from Ruskin and never relinquished, his militant irony, his willingness to fortify his position by painstaking investigation, his moral attitude toward matters artistic, his superb[Pg 12] rightness of taste in the special problem under discussion. They show also how closely his memory had held through his manifold interests the details that had appealed to him in his boyhood. The first letter is dated April 23rd, and addressed to the editor of the Daily Chronicle.

“Sir: I venture to ask you to allow me a few words on the subject of the present treatment of Epping Forest. I was born and bred in its neighbourhood (Walthamstow and Woodford), and when I was a boy and young man I knew it yard by yard from Wanstead to the Theydons, and from Hale End to the Fairlop Oak. In those days it had no worse foes than the gravel stealer and the rolling-fence maker, and was always interesting and often very beautiful. From what I can hear it is years since the greater part of it has been destroyed, and I fear, Sir, that in spite of your late optimistic note on the subject, what is left of it now runs the danger of further ruin.

“The special character of it was derived from the fact that by far the greater part was a wood of hornbeams, a tree not common save in Essex and Herts. It was certainly the biggest hornbeam wood in these islands, and I suppose in the world. The said hornbeams were all pollards, being shrouded every four or six years, and were interspersed in many places with holly thickets, and the result was a very curious and characteristic wood, such as can be seen nowhere[Pg 13] else. And I submit that no treatment of it can be tolerable which does not maintain this hornbeam wood intact.

“But the hornbeam, though an interesting tree to an artist and reasonable person, is no favourite with the landscape gardener, and I very much fear that the intention of the authorities is to clear the forest of native trees, and to plant vile weeds like deodars and outlandish conifers instead. We are told that a committee of ‘experts’ has been formed to sit in judgment on Epping Forest; but, Sir, I decline to be gagged by the word ‘expert,’ and I call on the public generally to take the same position. An ‘expert’ may be a very dangerous person, because he is likely to narrow his views to the particular business (usually a commercial one) which he represents. In this case, for instance, we do not want to be under the thumb of either a wood bailiff whose business is to grow timber for the market, or of a botanist whose business is to collect specimens for a botanical garden; or of a landscape gardener whose business is to vulgarise a garden or landscape to the utmost extent that his patron’s purse will allow of. What we want is reasonable men of real artistic taste to take into consideration what the essential needs of the case are, and to advise accordingly. Now it seems to me that the authorities who have Epping Forest in hand may have two intentions as to it. First, they may intend to landscape-garden it, or turn it into golf grounds (and I[Pg 14] very much fear that even the latter nuisance may be in their minds); or second, they may really think it necessary (as you suggest) to thin the hornbeams, so as to give them a better chance of growing. The first alternative we Londoners should protest against to the utmost, for if it be carried out then Epping Forest is turned into a mere place of vulgarity, is destroyed in fact.

“As to the second, to put our minds at rest, we ought to be assured that the cleared spaces would be planted again, and that almost wholly with hornbeam. And, further, the greatest possible care should be taken that not a single tree should be felled unless it is necessary for the growth of its fellows. Because, mind you, with comparatively small trees, the really beautiful effect of them can only be got by their standing as close together as the emergencies of growth will allow. We want a thicket, not a park, from Epping Forest.

“In short, a great and practically irreparable mistake will be made if, under the shelter of the opinion of ‘experts,’ from mere carelessness and thoughtlessness, we let the matter slip out of the hands of the thoughtful part of the public; the essential character of one of the greatest ornaments of London will disappear, and no one will have even a sample left to show what the great north-eastern forest was like. I am, Sir, yours obediently,

“William Morris

“Kelmscott House, Hammersmith.”

[Pg 15]The second letter is written two or three weeks later, and shows Morris as characteristically prompt and thorough in action as he is positive in speech.

“Yesterday,” he says, “I carried out my intention of visiting Epping Forest. I went to Loughton first, and saw the work that had been done about Clay Road, thence to Monk Wood, thence to Theydon Woods, and thence to the part about the Chingford Hotel, passing by Fair Mead Bottom and lastly to Bury Wood and the wood on the other side of the road thereby.

“I can verify closely your representative’s account of the doings on the Clay Road, which is an ugly scar originally made by the lord of the manor when he contemplated handing over to the builder a part of what he thought was his property. The fellings here seem to me all pure damage to the forest, and in fact were quite unaccountable to me, and would surely be so to any unprejudiced person. I cannot see what could be pleaded for them either on the side of utility or taste.

“About Monk Wood there had been much, and I should say excessive, felling of trees apparently quite sound. This is a very beautiful spot, and I was informed that the trees there had not been polled for a period long before the acquisition of the forest for the public; and nothing could be more interesting and romantic than the effect of the long poles of the hornbeams rising from the trunks and[Pg 16] seen against the mass of the wood behind. This wood should be guarded most jealously as a treasure of beauty so near to ‘the Wen.’ In the Theydon Woods, which are mainly of beech, a great deal of felling has gone on, to my mind quite unnecessary, and therefore harmful. On the road between the Wake Arms and the King’s Oak Hotel there has been again much felling, obviously destructive.

“In Bury Wood (by Sewardstone Green) we saw the trunks of a great number of oak trees (not pollards), all of them sound, and a great number were yet standing in the wood marked for felling, which, however, we heard had been saved by a majority of the committee of experts. I can only say that it would have been a very great misfortune if they had been lost; in almost every case where the stumps of the felled trees showed there seemed to have been no reason for their destruction. The wood on the other side of the road to Bury Wood, called in the map Woodman’s Glade, has not suffered from felling, and stands as an object lesson to show how unnecessary such felling is. It is one of the thickest parts of the forest, and looks in all respects like such woods were forty years ago, the growth of the heads of the hornbeams being but slow; but there is no difficulty in getting through it in all directions, and it has a peculiar charm of its own not to be found in any other forest; in short, it is thoroughly characteristic. I should mention that the whole of these[Pg 17] woods are composed of pollard hornbeams and ‘spear’—i.e., unpolled—oaks.

“I am compelled to say from what I saw in a long day’s inspection, that, though no doubt acting with the best intentions, the management of the forest is going on the wrong tack; it is making war on the natural aspect of the forest, which the Act of Parliament that conferred it on the nation expressly stipulated was to be retained. The tendency of all these fellings is on the one hand to turn over London forest into a park, which would be more or less like other parks, and on the other hand to grow sizable trees, as if for the timber market. I must beg to be allowed a short quotation here from an excellent little guidebook to the forest by Mr. Edward North Buxton, verderer of the forest (Sanford, 1885). He says, p. 38: ‘In the drier parts of the forest beeches to a great extent take the place of oaks. These “spear” trees will make fine timber for future generations, provided they receive timely attention by being relieved of the competing growth of the unpicturesque hornbeam pollards. Throughout the wood between Chingford and High Beech, this has been recently done, to the great advantage of the finer trees.’

“The italics are mine, and I ask, Sir, if we want any further evidence than this of one of the verderers as to the tendency of the fellings. Mr. Buxton declares in so many words that he wants to change the special character of the forest; to take[Pg 18] away this strange, unexampled, and most romantic wood, and leave us nothing but a commonplace instead. I entirely deny his right to do so in the teeth of the Act of Parliament. I assert, as I did in my former letter, that the hornbeams are the most important trees in the forest, since they give it its special character. At the same time I would not encourage the hornbeams at the expense of the beeches, any more than I would the beeches at the expense of the hornbeams. I would leave them all to nature, which is not so niggard after all, even on Epping Forest gravel, as e. g., one can see in places where forest fires have denuded spaces, and where in a short time birches spring up self-sown.

“The committee of the Common Council has now had Epping Forest in hand for seventeen years, and has, I am told, in that time felled 100,000 trees. I think the public may now fairly ask for a rest on behalf of the woods, which, if the present system of felling goes on, will be ruined as a natural forest; and it is good and useful to make the claim at once, when, in spite of all disfigurements, the northern part of the forest, from Sewardstone Green to beyond Epping, is still left to us, not to be surpassed in interest by any other wood near a great capital. I am, Sir, yours obediently,

“William Morris.”

These letters emphasise in a single instance what the close student of Morris will find emphasised at[Pg 19] every turn in his career,—the persistent and strong influence over him of the tastes and occupations of his boyhood. Unless this is kept constantly in mind, it is easy to fall into the common error of regarding the various activities into which he threw himself as separate and dissociated instead of seeing them as they were, component parts of a perfectly simple purpose and unalterable ideal. With most men who are on the whole true to the analogy of the chambered nautilus and cast off the outworn shell of their successive phases of individuality as the seasons roll, the effect of early environment and tendency may easily be exaggerated, but Morris grew in the fashion of his beloved oaks, keeping the rings by which his advance in experience was marked; at the end all were visible. His education began and continued largely outside the domain of books and away from masters. His wanderings in the depths of the quaint and beautiful forest, his intimate acquaintance with the nature of Gothic architecture, his familiarity with Scott, his prompt adoption of Ruskin, all these formed the foundation on which he was to build his own theory of life, and all were his before he went up to Oxford. They prepared him for the many-sided profession, if profession it can be called, which was to absorb and at last to exhaust his mighty energy. It was the tangible surface of the world that most inspired him in boyhood and in maturity. Loving so much even as a child its aspects, its lights and shadows, the forms of trees and birds and[Pg 20] beasts, the changes of season, the lives of men living close to “the kind soil” and in touch with it through hearty manual labour, it was but a step to the occupations that finally engrossed him. He never got so far away from the visions of his youth as to forget them. In one form or another he was constantly trying to embody them that others might see them with his eyes and worship them with his devotion. “The spirit of the new days, of our days,” says the old man in News from Nowhere, “was to be delight in the life of the world, intense and almost overweening love of the very skin and surface of the earth on which man dwells.”

OXFORD LIFE.

Like the majority of the students who went up to Oxford in the fifties, Morris matriculated with the definite intention of taking holy orders. Unlike the majority, he was impelled not only by the sensuous beauty of ritualistic worship, to which, however, no one could have been more keenly alive than he, but by a genuine enthusiasm for a life devoted to high purposes. A fine buoyant desire to better existing conditions and sweep as much evil as possible off the face of the earth early inspired him. His mind turned toward the conventual life as that which combined the mediæval suggestions always alluring to him with the moral beauty of holiness. He planned a “Crusade and Holy Warfare against the Age,” sang plain song at daily morning service, read masses of mediæval chronicles and ecclesiastical Latin poetry, and hovered just this side of the Roman Communion. Had the ecclesiology of the University been supported at that time by an inward and spiritual grace sufficient to hold the heart[Pg 22] of youth to a sustained allegiance, there is little doubt that Morris would have thrown himself ardently into the religious path. But Oxford had become an indolent and indifferent mother to her children. The storm of feeling aroused by the Tractarian movement had died down and the reaction from it was evident. At Balliol Jowett’s energy had made its mark, but at Exeter, where Morris was, the educational system deserved (and received) the contempt of an ambitious boy with an unusually large supply of stored-up intellectual force seeking outlet and guidance. Nor was the social life more stimulating to moral activity. The abuses recorded in 1852 by the University Commission were in essence so shameful that in the light of that famous report “the sweet city with her dreaming spires” seems to have only the beauty of the daughter of Helios, under whose enchantments men were turned to swine for loving her. The clean mind and honest nature of Morris revolted from the excesses that went on about him. He wrote to his mother two years after his matriculation, defending the proposition that his Oxford education had not been thrown away: “If by living here and seeing evil and sin in its foulest and coarsest forms, as one does day by day, I have learned to hate any form of sin and to wish to fight against it, is not this well too?” It is proof of his purity of taste and strength of will that, despite his ample means, the wanton extravagance of the typical undergraduate had for him no allurement. It is certain that he was[Pg 23] never seen at those dinners which were pronounced by an official censor “a curse and a disgrace to a place of Christian education,” and as certainly he played no part in the mad carnivals at which novices were initiated into a curriculum of vice. Yet he could not indeed say with any truth what Gibbon had said a hundred years before, that the time he spent at Oxford was the most idle and unprofitable of his whole life. If he felt, as Gibbon did, that his formal studies were “equally devoid of profit and pleasure,” and if he found nothing ridiculous in Ruskin’s bitter complaint that Oxford taught him all the Latin and Greek that he would learn, but did not teach him that fritillaries grew in Iffley meadow, he did find a little band of helpful associates. With these he realised the priceless advantages which Mr. Bagehot says cannot be got outside a college and which he sums up as found “in the books that all read because all like; in what all talk of because all are interested; in the argumentative walk or disputatious lounge; in the impact of fresh thought on fresh thought, of hot thought on hot thought; in mirth and refutation, in ridicule and laughter.” The first of the few strong personal attachments in the life of Morris dates from his first day at Oxford. At the end of January, 1853, he went up for his matriculation, and beside him at the examination in the Hall sat Burne-Jones, who within a week of their formal entrance to the college became his intimate. The friendship thus spontaneously formed on the verge of[Pg 24] manhood lasted until Morris died. In their studies, in their truant reading, in their later aims and work, the two, diametrically as they differed in aspect and in temperament and in quality of mind, were sympathetic and dear companions. Together they joined a group of other happily gifted men—Fulford, Faulkner, Dixon, Cormell Price, and Macdonald—who met in one another’s rooms for the disputatious lounge over the exuberant ideals by which they were in common inspired. Tennyson, Keats, and Shelley, Shakespeare, Ruskin, Carlyle, Kingsley, Thackeray, Dickens, and Miss Yonge were the gods and half gods of their young and passionate enthusiasm. The last, curiously enough, was an influence as potent as any. The hero of her novel of 1853, The Heir of Redclyffe, was the pattern chosen by Morris, according to Mr. Mackail’s account, to build himself upon. Singular as it seems to-day that any marked impression should have been made upon an even fairly well-trained mind by a writer of such slight literary quality, it is true that the author of The Daisy Chain counted among her devoted readers men of brilliant and dominant intellectual power. She had the lucky touch to kindle in young minds that fire of sympathy with which they greet whatever shows them their own world, their age, themselves as they best like to see them. To Morris in particular the young heir of Redclyffe made the appeal of a congenial temperament in a position similar to his own. Like Morris, he was headstrong and passionate, given[Pg 25] to excessive bursts of rage and to repentances not less excessive; like Morris, he united to his natural pride an unnatural and slightly obtrusive humility; like Morris, he was rich and beautiful, generous and lovable. It was no great wonder that Morris, poring with his characteristic absorption over the pleasant pages on which Guy Morville’s chivalrous life is portrayed, said as Dromio to Dromio, “Methinks you are my glass and not my brother; I see by you I am a sweet-faced youth.”

Mr. Mackail notes with an accent of surprise that Kingsley was much more widely read than Newman, thinking the choice a curious one in the case of passionate Anglo-Catholics. So far as Morris was concerned, however, there was little enough to relish in Newman’s subtle theology and relentless logic. The man to whom religion as a mere sentiment was “a dream and a mockery” could hardly appeal to one to whom all life was a sentiment. Kingsley, on the other hand, although he was anti-Catholic in temper, and disposed to overthrow the illusions by which such romanticists as Scott, such dreamers as Fouqué, had surrounded the Middle Ages, picturing their coarse and barbarous side with harsh realism, was happy in rendering the charms of outdoor life and bold adventure, and the songs of the Crusaders in his Saint’s Tragedy must have gone farther toward winning Morris than pages of Newman’s reasoning devotion.

Gradually the monastic ideal faded before the brightness of art and literature and the life of the[Pg 26] world as these became more and more impressed upon Morris’s consciousness. To live in the spirit and in the region of purely intellectual interests could not have been his choice after the passing of the first fanatic impulse of youth to dedicate itself to what is difficult, ignorant of the joy of choosing. Many influences united to determine the precise form into which he should shape the future that for all practical purposes was under his control. His interest in pictorial art was stimulated by Burne-Jones, who was already making fantastic little drawings, and studies of flowers and foliage. Of great art he knew nothing until he spent the Long Vacation of 1854 in travelling through Belgium and Northern France, where he saw Van Eyck and Memling, who at once became to him, as they were to Rossetti, masters of incontestable supremacy. On this trip he saw also the beautiful churches of Amiens, Beauvais, and Chartres, which in his unbridled expansiveness of phrase he called “the grandest, the most beautiful, the kindest, and most loving of all the buildings that the earth has ever borne.” The following year he repeated the experience, with Burne-Jones and Fulford for companions. This time the journey was to have been made on foot from motives of economy, as Burne-Jones was poor and Morris embraced the habits of poverty when in his company with unaffected delicacy of feeling. At Amiens, however, Morris went lame, and, “after filling the streets with imprecations on all boot-makers,” bought a pair of gay[Pg 27] carpet slippers in which to continue the trip. These proved not to serve the purpose, and the travellers were obliged to reach Chartres by the usual methods of conveyance, Morris arguing with fury and futility in favour of skirting Paris, “even by two days’ journey, so as not to see the streets of it.” They had with them one book, Keats, and their minds were filled with the poetic ideas of art as the expression of man’s pleasure in his toil, and of beauty as the natural and necessary accompaniment of productive labour, which Ruskin had been preaching in The Stones of Venice and in the Edinburgh lectures. By this time they had become acquainted with the work of the Pre-Raphaelites, and Burne-Jones had announced that of all men who lived on earth the one he wanted to see was Rossetti. Morris had used his spare time, of which we may imagine he had a considerable amount, in the study of mediæval design as the splendid manuscripts in the Bodleian Library illustrate it. An architectural newspaper also formed part of his regular reading outside of his studies. Thus primed for definite action, on this holiday filled with stimulating interests and the delicious freedom of roaming quite at will with the best of companions through the sweet fertile country of Northern France, Morris put quite aside all aims that had not directly to do with art. He and Burne-Jones, walking late one night on the quays of Havre, discussed their plans. Both gave up once and for all the idea of taking orders; both[Pg 28] decided to leave Oxford as quickly as they could; both were to be artists, Burne-Jones a painter and Morris an architect.

Although Morris was never to become a practising architect, this choice of a profession at the beginning of his career is both characteristic and significant. Buildings, as we have seen, had interested him from his childhood. His favourite excursions, long and short, had been to the region of churches. In the art of building he saw the means of elevating all the tastes of man. Architecture meant to him “the art of creating a building with all the appliances fit for carrying on a dignified and happy life.” It seemed to him even at the outset, before the word “socialism” had come into his vocabulary, incredible that people living in pleasant homes and engaged in making and using these appliances of which he speaks, should lead lives other than dignified and happy. It was much more in accordance with his ideal of a vocation, a ministry to man, that he should contribute to the daily material comfort and pleasure of the world, that he should make places good for the body to live in and fair for the eye to rest upon, and therefore soothing to the soul, than that he should construct abstract spiritual mansions of which he could at best form but a vague conception. It was, then, with a certain sense of dedication, an exchange of method without a change of spirit, that he gave up the thought of holy orders and turned to the thought of furthering the good of[Pg 29] mankind by working toward the beauty and order of the visible world.

From the point of view of his later interests as a decorator of houses, he was showing the utmost wisdom in beginning with the framework, which must exist before any decoration can be applied. “I have spoken of the popular arts,” he says himself, in one of his lectures, “but they might all be summed up in that one word Architecture; they are all parts of that great whole, and the art of house-building begins it all. If we did not know how to dye or to weave; if we had neither gold nor silver nor silk, and no pigments to paint with but half a dozen ochres and umbers, we might yet frame a worthy art that would lead to everything, if we had but timber, stone and lime, and a few cutting tools to make these common things not only shelter us from wind and weather but also express the thoughts and aspirations that stir in us. Architecture would lead us to all the arts, as it did with the earlier men; but if we despise it and take no note of how we are housed, the other arts will have a hard time of it indeed.”

And again: “A true architectural work,” he says, “is a building duly provided with all the necessary furniture, decorated with all due ornament, according to the use, quality, and dignity of the building, from mere mouldings or abstract lines to the great epical works of sculpture and painting, which except as decorations of the nobler form of such buildings[Pg 30] cannot be produced at all. So looked upon, a work of architecture is a harmonious, co-operative work of art, inclusive of all the serious arts—those which are not engaged in the production of mere toys or ephemeral prettinesses.”

Morris communicated his momentous decision to his family as soon as it was made, and they received it with amazement and distress. While their origin was not especially aristocratic, their tastes ran toward the symbols of aristocracy. When Morris was nine years old, his father obtained a grant of arms from the Heralds’ College, and the son had no small liking for the bearings assigned—bearings which included a horse’s head erased argent between three horseshoes. The horse’s head he introduced on the tiles and glass of the house he built for himself in later years, and he was in the habit of making a yearly pilgrimage to the famous White Horse of the Berkshire Downs, connecting it in some obscure way with his ancestry. In England, during the fifties, nothing was less calculated to appeal to an aristocratic tendency than any form of art considered as a profession. In The Newcomes Mr. Honeyman remarks with bland dignity to his aspiring young relative; “My dear Clive, there are degrees in society which we must respect. You surely cannot think of being a professional artist.” In much this spirit, apparently, Mrs. Morris received her son’s announcement, conveyed in a long and affectionate letter stating in detail the motives that had led him to[Pg 31] his resolution. After defending his chosen profession at some length, calling it with characteristic avoidance of pompous phraseology, “a useful trade,” he dwells upon the moderation of his hopes and expectations. He does not hope “to be great at all in anything,” but thinks he may look forward to reasonable happiness in his work. It will be grievous to his pride and self-will, he says, to have to do just as he is told for three long years, but “good for it, too,” and he looks forward with little delight to the drudgery of learning a new trade, but is pretty confident of success, and is happy in being able to pay “the premium and all that” without laying any fresh burden of expense upon his mother. Finally he proposes taking as his master George Edmund Street, who was living in Oxford as architect of the diocese, and whose enthusiasm for the thirteenth century could hardly have failed to claim the sympathy of Morris. Certainly it seemed precisely the fitting opportunity that offered. There could have been no better moment for him to follow the advice he so frequently gave to others—to turn his back upon an ugly age, choose the epoch that suited him best, and identify himself with that. Gothic to the core, he had come to Oxford, not, as Mr. Day has suggested, to catch the infection of mediævalism abroad there, but to assimilate and thrive upon all the influences to which his independently mediæval spirit was acutely susceptible. Scott, Pugin, Shaw, Viollet-le-Duc, had broken the way through popular prejudice, and Street was[Pg 32] engaged at the time Morris went to him in the work of restoring ancient churches and designing Gothic buildings. “Restoration” had not then so evil a sound to Morris as it later came to have. Some thirty years after, he was to say: “No man or no body of men, however learned they may be in ancient art, whatever skill in design or love of beauty they may have, can persuade, or bribe, or force our workmen of to-day to do their work in the same way as the workmen of King Edward I. did theirs. Wake up Theodoric the Goth from his sleep of centuries and place him on the throne of Italy, turn our modern House of Commons into the Witenagemote (or Meeting of the Wise Men) of King Alfred the Great!—no less a feat is the restoration of an ancient building.” In 1855, however, he had not fully arrived at this conviction. It was then the period of “fresh hope and partial insight” which, regarding it retrospectively, he says, “produced many interesting buildings and other works of art, and afforded a pleasant time indeed to the hopeful but very small minority engaged in it, in spite of all vexations and disappointments.” There seemed no reason to suppose that, helped as he was by his predilections and by his environment, he could not become the master-builder of the house beautiful that constantly haunted his imagination.

TITLE-PAGE OF “THE OXFORD AND CAMBRIDGE MAGAZINE”

He was not to begin at once, however. In deference to his mother’s wish he went through his final term, passed in the Final Schools without difficulty,[Pg 33] and, together with his companions—The Brotherhood as they now called themselves,—gave distinction to his last year at the University, where despite all drawbacks he had been aboundingly happy, by founding the since famous little Oxford and Cambridge Magazine.

Like the Pre-Raphaelite Germ, this periodical aimed at an unusually high standard. It was printed at the Chiswick Press with some pretensions to typographical beauty. Each number had upon its title-page an ornamental heading designed by one of Charles Whittingham’s daughters and engraved by Mary Byfield. On the green wrappers the name of the magazine was printed in the old-fashioned type which the Chiswick Press was the first to revive, and although, unlike The Germ, it was not illustrated, photographs of Woolner’s medallions of Carlyle and Tennyson were mounted to bind with it and sold at a shilling apiece to subscribers. The price of each number was also a shilling, and twelve monthly numbers appeared, making it thrice as long lived as its prototype, The Germ. The financial responsibility, says Mr. Mackail, was undertaken wholly by Morris, and he at first attempted the general control. This he was soon glad to relinquish, paying a salary of a hundred pounds a year to his editor. The title, which in full read The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine, Conducted by Members of the Two Universities, indicates rather more co-operation than existed, the magazine being conducted entirely by Oxford men[Pg 34] and fully two-thirds written by them. The tone of the contributions was to be impeccable. “It is unanimously agreed,” wrote Price, “that there is to be no shewing off, no quips, no sneers, no lampooning in our Magazine.” Politics were to be almost eschewed, “Tales, Poetry, friendly Critiques, and social articles” making up the body of the text.

First among the contributors in quantity and regularity of supply was Morris. During his second year at the University he had discovered that he could write poetry, and had communicated the fact to his companions without loss of time. Canon Dixon, recalling the very thrilling occasion of his reading his first poem to the group gathered in the old Exeter rooms occupied by Burne-Jones, affirms that he reached his perfection at once, that nothing could have been altered for the better, and also quotes him as saying, “Well, if this is poetry, it is very easy to write.” He was not one to let a capability fust in him unused. Poetry and prose, equally easy to him, poured after this from his pen, giving expression with some confusion and incoherence to his boyish raptures over the things he best loved and most thought about. During the twelve months of the magazine’s life he contributed to it five poems, eight prose tales, a review of Browning’s Men and Women, and two special articles, one on a couple of engravings by Alfred Bethel and one on the Cathedral at Amiens. In all this early work, filled with superabundant imagery, self-conscious, sensuous, [Pg 35]unsubstantial, pictorial, we have Morris the writer as he was at the beginning and much as he was again at the end. His first strange little romances pass before the eyes as his late ones do, like strips of beautiful fabric, deeply dyed with colours both dim and rich, and printed with faintly outlined figures in postures illustrating the dreamy events of dreamy lives. Many of the pages echo with the sound of trumpets and the clash of arms, but the echo is from so far away that the heart of the reader declines to leap. Passionate emotions are portrayed in passionate language. Men and women love and die with wild adventure. Splendid sacrifices are made, and dark revenges taken. But the effect is of marionettes, admirably costumed and ingeniously managed yet inevitably suggesting artifice and failing to suggest life. Nevertheless Morris wrote in the fashion commonly supposed to impart vitality if nothing else to composition. He sat up late of nights, after the manner of young writers, and let his words stand as they fell hot and unpremeditated on the page. The labour of learning the art, as his favourite, Keats, learned it, by indefatigable practice in finding the perfect word, the one exquisite phrase, was quite outside his method. As long as he lived, he preferred rewriting to revising a manuscript. The austerity of mind that leads to impatience of superfluous colour or tone, and that dreads as the plague superfluous sentiment, was foreign to him, nor did he ever acquire it as even the Epicurean temperament may do by ardent[Pg 36] self-restraint. In most of the romances and poems the scene is laid somewhat vaguely but unmistakably in the Middle Ages. We rarely surprise the young writer in a date, but the atmosphere is that of the thirteenth century though with many thirteenth-century characteristics left out. The incidents appeal to what Bagehot calls “that kind of boyish fancy which idolises mediæval society as the ‘fighting time.’” The distinction lies in the fertility and beauty of the descriptions. On nearly every page is some passage that has the quality of a picture. In The Hollow Land, in Gertha’s Lovers, in Svend and his Brethren, and especially in the article on the Amiens Cathedral, are exquisite landscapes and backgrounds against which the personages group themselves with perfect fittingness. “I must paint Gertha before I die,” said Burne-Jones, after Morris himself was dead, recalling the charm of this story which was written in his company, under the willows by the riverside. “The opening and the closing sentences always invited me in an indescribable way, but the motive par excellence was that of Gertha after death, in the chapter entitled ‘What Edith the Handmaiden Saw from the War Saddle,’ where the beautiful queen lies on the battle-field with the blue speedwell about her pale face, while a soft wind rustles the sunset-lit aspens overhead.”

Portrait of Rossetti

By Watts

To his genius for evoking a scene from memory or imagination with a grace and delicacy missing in the designs he was later to make with tools more rebellious than words, Morris added a[Pg 37] singular ability to convey to his readers the most significant quality of what he admired, to impress them with the feature that had most impressed him. The fancy for gold, inspired perhaps by study of mediæval illumination, runs like a glittering thread through the story of Svend and his Brethren. Cissela’s gold hair, her crown of gold, the golden ring she breaks with her lover, the gold cloth over which she walks across the trampled battle-field, the samite of purple wrought with gold stars, the golden letters on the sword-blade,—all these recur like so many bright accents from which the attention cannot escape. Again, in the description of Amiens Cathedral, we get from simple verbal repetition the effect of massive modelling, the sense of weight in the design as Morris felt it in one of the sculptured figures of the niches: “A stately figure with a king’s crown on his head, and hair falling in three waves over his shoulders; a very kingly face looking straight onward; a great jewelled collar falling heavily to his elbows: his right hand holding a heavy sceptre formed of many budding flowers, and his left just touching in front the folds of his raiment that falls heavily, very heavily to the ground over his feet. Saul, King of Israel.” In another passage describing with minute detail the figures of the Virgin and Child, a similar emphasis is laid on the quality of restfulness. “The two figures are very full of rest; everything about them expresses it from the broad forehead of the Virgin, to the resting of the feet of[Pg 38] the Child (who is almost self-balanced) in the fold of the robe that she holds gently, to the falling of the quiet lines of her robe over her feet, to the resting of its folds between them.” And if the effect to be rendered is one of colour, a touch of finer eloquence is added to this somewhat crude method. The final passage of the account of the great Cathedral is a genuine triumph of poetic observation, carrying the fancy of the reader lightly over the silvery loveliness of the picture as it lay before the boy enraptured by it: “And now, farewell to the church that I love, to the carved temple-mountain that rises so high above the water-meadows of the Somme, above the grey roofs of the good town. Farewell to the sweep of the arches, up from the bronze bishops lying at the west end, up to the belt of solemn windows, where, through the painted glass, the light comes solemnly. Farewell to the cavernous porches of the west front, so grey under the fading August sun, grey with the wind-storms, grey with the rain-storms, grey with the beat of many days’ sun, from sunrise to sunset; showing white sometimes, too, when the sun strikes it strongly; snowy-white, sometimes, when the moon is on it, and the shadows growing blacker; but grey now, fretted into deeper grey, fretted into black by the mitres of the bishops, by the solemn covered heads of the prophets, by the company of the risen, and the long robes of the judgment-angels by hell-mouth and its flames gaping there, and the devils that feed it; by the saved souls and the crowning[Pg 39] angels; by the presence of the Judge, and by the roses growing above them all forever.”

The review of Browning’s Men and Women, then recently published, is more valuable as testifying to the impression produced by Browning upon his young contemporary, than for any especial illumination it throws upon the poems themselves. Browning was popular with the students of Oxford long before he gained his wider audience, and although Morris did not follow him far in his investigation of the human soul and came heartily to dislike “his constant dwelling on sin and probing of the secrets of the heart,” he placed him at the time of writing his criticism “high among the poets of all time” and he “hardly knew whether first or second in our own,” and his defence of him, bristling with ejaculations, and couched in boyish phrases, shows in part a more than boyish divination. “It does not help poems much to solve them,” he says, after what, in truth, is a somewhat disastrous attempt to interpret the meaning of Women and Roses, “because there are in poems so many exquisitely small and delicate turns of thought running through their music, and along with it, that cannot be done into prose, any more than the infinite variety of form, and shadow, and colour in a great picture can be rendered by a coloured woodcut.” It was “a bitter thing” to him to see the way in which the poet had been received by “almost everybody,” and he assured his little world that what the critics called obscurity in[Pg 40] Browning’s poems resulted from depth of thought and greatness of subject on the poet’s part, and on his readers’ part, “from their shallower brains and more bounded knowledge,” if not indeed from “mere wanton ignorance and idleness,” and to this kind of obscurity one had little right to object. It was the first tilt in the lists, the beginning of the long combat against the Philistines upon which Morris entered with high resolve and firm conviction, which he lustily enjoyed, and in which despite many a broken lance he bore himself as a bold and skilful knight.

In the little tale called The Hollow Land, written for the magazine just before it “went to smash,” to use Burne-Jones’s expressive phrase, an amusingly significant sentence occurs: “Then I tried to learn painting,” says the hero, “till I thought I should die, but at last learned through very much pain and grief.” Here it is not difficult to recognise an autobiographic touch. Painting was already beginning to beckon Morris away from the profession he had so recently chosen. At the end of 1855, during the Christmas vacation, and just before Morris entered Street’s office, Burne-Jones had made a visit to London, where at a monthly meeting at the Working Men’s College he for the first time saw Rossetti, and later heard him rend in pieces the opinions of those who differed with him, and stoutly support his infrangible theory that all men should be painters. How ready Burne-Jones was to yield himself[Pg 41] to this potent influence, how promptly Rossetti’s vivid and original temperament acted upon his admirer, is clear from the latter’s description, written many years after, of the first encounter—the young undergraduate sitting half-frightened, embarrassed and worshipping, among strangers, eating thick bread and butter, and listening to speeches about the progress of the college, until the entrance of his idol, whose sensitive, gentle, indolent face, with its flickering of humour and the fire of genius, entirely satisfied his poetic imagination. The great qualities of Rossetti in those days revealed themselves in his face, and his imperious will and keen intellect were no less obvious in his talk. Burne-Jones returned to Oxford with the idea of dedicating himself to art more than ever firmly fixed in his mind. Rossetti had approved the drawings which he had brought to him for consideration, and had pronounced the seven months still to elapse before he could take his degree time too valuable to waste outside of art, counselling him to fling the University and all its works behind him and begin painting at once. With mingled delight and terror Burne-Jones, in spite of small means and weak health, followed his leader, who, however rash to advise, was not one to neglect his charge, and who worked loyally to bring him through with triumph, criticising, teaching, approving, encouraging without stint, and presently, after his own inimitable fashion, bringing patrons to him, bidding them buy, which obediently they did.

[Pg 42]It was inevitable that Morris should be stirred to emulation by this step on the part of his friend. After Burne-Jones went to London to begin painting under Rossetti’s direction, Morris spent nearly all his Sundays with him at his lodgings in Chelsea. These holidays were full of excitement. It was a glorious little world that opened out under Rossetti’s enthusiastic, dogmatic, and continuous talk and argument. Morris was deeply impressed by his notion that everyone should be a painter, and after Street moved his office to London and Morris and Burne-Jones took lodgings together, the former tried the characteristic experiment of combining painting with architecture, attempting to get six hours a day at his drawing in addition to his office work. It is interesting to find him writing at this juncture that he cannot enter into politico-social subjects with any interest, that things are in a muddle and that he has no power to set them right in the smallest degree, that his work is the embodiment of dreams in one form or another. What Rossetti thought of his two disciples is seen in a letter written by him to William Allingham in December, 1856, when Morris had been nearly a year with Street. He found both “wonders after their kind.” “Jones is doing designs which quite put one to shame,” he wrote, “so full are they of everything—Aurora Leighs of art. He will take the lead in no time.” Morris he deemed “one of the finest little fellows alive—with a touch of the incoherent, but a real man,” and “in [Pg 43]all illumination and work of that kind” he considered him quite unrivalled by anything modern that he knew. With a guide thus confident and inspiring, it is not strange that Morris presently yielded to the spell, and renounced architecture to pursue painting as an end and aim in itself, although, like the hero of his romance, he learned with much pain and grief.

ILLUSTRATION BY ROSSETTI TO “THE LADY OF SHALOTT”

IN THE MOXON “TENNYSON.” THE HEAD OF

LAUNCELOT IS A PORTRAIT OF MORRIS

Rossetti’s service to Morris is difficult to estimate. For a brief period his influence over him was supreme. Perhaps in the work and temper of this Italian, Morris saw more deeply into the heart of the mediæval world than all his churches and illuminated manuscripts could help him to see. At all events, he was for the time close to genius and dominated by it. His devotion to his master partook of the violence inseparable from his temperament. He was soon ready to say, when Burne-Jones complained that he worked better in Rossetti’s manner than in his own: “I have got beyond that; I want to imitate Gabriel as much as I can.” But he was never to be for very long under any personal influence. Nor could he be persuaded by the most brilliant eloquence in the world that good could be got out of doing what he did not enjoy; and he never enjoyed any labour that required long patience and persistent concentration of effort. Without being fickle, his mind was so restless as to produce the effect of fickleness and to preclude the possibility of his doing really great work. While he was trying,[Pg 44] under Rossetti’s stimulating but peremptory rule, to master a painter’s methods he became gloomy and despondent. “How long Rossetti’s daily influence might have kept him labouring at what he could not do,” writes Mr. Mackail with a tinge of bitterness, “when there was work all round that he could do, on the whole, better than any man living, it is needless to inquire.” But that Rossetti did manage to keep him for a couple of years at the study of painting cannot be counted a misfortune. Probably that experience, together with his brief term under Street, did as much as anything to save his design from mediocrity and imitativeness. He did not make himself an architect, and he never learned to draw anything that remotely resembled the actual structure of the human form, but he must have gained through his study some knowledge of the inviolable laws of art that he could not have gained by passive observation however keen, or by sympathy however ardent. Rossetti can hardly have been the best master for him. His own nature was too undisciplined, and he had as few of the academic virtues as any man on record of the same technical ability. But his was the supreme faculty of rousing enthusiasm. It may be doubted whether any other painter in England could have kept Morris at the appointed and impossible task for so long a time. It is easy to imagine how the impatient spirit of the latter rebelled against the slow process of learning to draw the human figure in its complicated and subtle[Pg 45] beauty of construction and surface. The fact that he stopped so far short of satisfactory accomplishment seems to account for many of the defects to be found in his later designs, which at their best were never to be entirely beautiful, though full of zest and freedom. His tendency to drop any branch of his work as soon as it became tedious to him, to turn to something else, kept his creative impulse continually fresh and effective; but kept him also from achieving the penetrating distinction of artistic self-possession. Whatever helped him in any degree toward this self-possession, whatever he got in the way of discipline of mind and hand, should be acknowledged by his admirers with gratitude, and it is but just to recognise in Rossetti the one man who seems to have kept the prodigious impetuosity of Morris down without promptly losing hold upon his interest. Add to this the clear vision of a romantic ideal which all who worked with Rossetti were privileged to share, and the constant inspiration of the drama of sentiment and emotion rendered in his colour and line and in his exotic treatment of form, and we must own that nowhere else could Morris have found such food for an imagination already quickened by influences reaching it from a remote time and an alien world. Nowhere else could he have come so close to the concealed mysteries of the human soul, despite the disillusionment he was bound to feel in daily contact with a character as contradictory as it was compelling.

FROM ROSSETTI TO THE RED HOUSE.

Although a blight of discouragement seems to have fallen upon Morris under Rossetti’s tuition, there were some blithe compensations. Not the least of these was the fitting up of the rooms at 17 Red Lion Square where he and Burne-Jones took quarters. “Topsy and I live together,” wrote Burne-Jones, “in the quaintest room in all London, hung with brasses of old knights and drawings of Albert Dürer.” For the furniture, Morris, who, Rossetti said, was “bent on doing the magnificent,” made designs to be carried out in deal by a carpenter of the neighbourhood. Everything was very large and heavy, intensely mediæval, and doubtless rather ugly in an honest fashion, but in the end it was furniture to be coveted, for it offered great spaces for decoration, and Rossetti as well as Morris and Burne-Jones painted on it subjects from Chaucer and Dante and the Arthurian stories. The panels of a cupboard glowed with Rossetti’s beautiful pictures representing Dante and Beatrice meeting in[Pg 47] Florence and meeting in Paradise, and on the wide backs of the chairs he painted scenes from some of the poems Morris had written. The wardrobe was decorated by Burne-Jones with paintings from The Prioress’s Tale. On the walls of the room were hung, no doubt, the several water-colours bought from Rossetti, to the lovely names of which Morris promptly wrote ballads. An owl was co-tenant with the young artists, and they were served and also criticised by a housemaid of literary ambitions. In this highly individual apartment, where, curiously enough, Rossetti and his friend Deverell had had their studio together five or six years before, life was not all labour and striving. There were, moreover, holidays spent at the Zoölogical Gardens, evenings at the theatre, night-long sessions in Rossetti’s rooms, and excursions on the Thames. One of the latter is vividly described in Dr. Birkbeck Hill’s Letters of Gabriel Rossetti to William Allingham, giving a joyous picture of Morris at the mercy of his ungovernable temper. The party, consisting of Hill, Morris, and Faulkner, had started out to row down the Thames from Oxford to a London suburb. By the time they had reached Henley they had spent all their money except enough for Faulkner’s return ticket to Oxford, where he was to attend a college meeting. For this he departed, promising to bring back a supply of money in the evening. “The weather was unusually hot,” writes Dr. Hill, “Morris and I sauntered along the river-side. I have not forgotten the longing[Pg 48] glances he cast on a large basket of strawberries. He had always been so plentifully supplied with money that he bore with far greater impatience than I did this privation. At last the shadows had grown long and the heat was more bearable. We went with light hearts to the railway station to meet our comrade. ‘Well, Faulkner,’ cried out Morris, cheerfully, ‘how much money have you brought?’ Our friend gave a start. ‘Good heavens,’ he replied, ‘I forgot all about it.’ Morris thrust both his hands into his long dark curly hair, tugged at it wildly, ground his teeth, swore like a trooper, and stamped up and down the platform—in fact, behaved just like Sinbad’s captain when he found that his ship was driving upon the rocks. His outbursts of rage, I hasten to say, were always harmless. They left no sullenness behind, and as each rapidly passed away he was ready to join in a hearty laugh at it. Faulkner, who was not the most patient of men, noticed that passengers, station-master, porters, engine-driver, and stoker were all gazing in astonishment. He, too, lost his temper, and, though in a far lower key, stormed back. Morris soon quieted down, and a council of war was held. He fortunately had a gold watch-chain on which he raised enough to pay all needful expenses. I remember well how the rest of our journey we rowed by many a tavern on the bank as effectually constrained as ever was Ulysses not to listen to its siren call. It was through no earthly paradise that the young poet and artist passed[Pg 49] on the afternoon of our last day.” When they landed they had just a penny among them, and were still some six or seven miles from their destination, so they were obliged to hire a cab and trust to good fortune for not coming to a turnpike gate before arriving at Red Lion Square.

About this time also Rossetti and Morris made an excursion to Oxford for the purpose of visiting Benjamin Woodward, the architect and Rossetti’s friend. Mr. Woodward had recently erected a building for the Oxford Union, a society composed of past and present members of the University. In exhibiting the building to Rossetti it was suggested that the blank stretch of wall which ran around the top of the Debating Room afforded an admirable opportunity for decoration, and Rossetti with prompt enthusiasm evolved a plan for a coöperative enterprise. He and Morris, with several other willing spirits,—Burne-Jones, of course, Arthur Hughes, Valentine Prinsep, Spencer Stanhope, and J. Hungerford Pollen,—were to go up to Oxford in a body. Each was to choose a subject from the Morte d’Arthur, and execute it to the best of his ability on the walls of the Debating Room. The whole affair was to be a matter of a few weeks. The artists offered their services for nothing; their expenses (which turned out to be as free as their offer) were to be paid by the Union. It is easy to imagine the ensuing bustle and ardour. Rossetti eagerly managing, Morris delighted with the charmingly mediæval situation,—a few humble painters[Pg 50] working together piously, without hope of glory or thought of gain,—the others following their leader with lamb-like docility. Had their knowledge of methods been equal to their zeal, the walls of the Debating Room must have become the loveliest of realised visions and the delight of many generations. The young workmen sat for each other, Morris, Burne-Jones, and Rossetti all possessing fine paintable heads. They clambered up and down endless ladders to gain a satisfactory view of their performance, and attacked the most stupendous difficulties with patience and ingenuity. The faces in the subject undertaken by Burne-Jones were painted, for example, in three planes at right angles to one another, owing to the projection of a string-course of bricks straight across the space to be filled by the heads of the figures. Some studies by Rossetti have been preserved, and show that his part at least of the decoration was conceived in a fresh poetic spirit, with fulness and quaintness of expression and suggestion. But the congenial band had entered upon their labours with a carelessness that can only be described as wanton. Not one of them knew how to paint in tempera, and the new damp walls were smeared over with a thin coat of white lime wash laid upon the bare bricks as sole preparation for a sort of water-colour painting that blossomed like a flower under the gifted hands of the artists, and faded almost as soon away. The effect at the time was so brilliant as to make the walls, according to Mr.[Pg 51] Coventry Patmore’s contemporaneous testimony, “look like the margin of an illuminated manuscript,” but in the course of a few months the colours had sunk into the sponge-like surface to such an extent that the designs were already dim and indistinguishable.