"There is nothing unclean of itself: but to him that esteemeth anything to be unclean, to him it is unclean."

—Paul (Romans xiv. 14).

CONTENTS

PHALLIC WORSHIP AMONG THE JEWS.

THE BRAZEN SERPENT, AND SALVATION BY SIMILARS.

SAUL'S SPIRITUALIST STANCE AT ENDOR.

List of Illustrations

Fig. 1.—the Hindu Maha Deva, Or Linga-yoni

My old friend Mr. Wheeler asks me to launch this little craft, and I do so with great pleasure. She is not a thunderous ironclad, nor a gigantic ocean liner; but she is stoutly built, well fitted, and calculated to weather all the storms of criticism. My only fear is that she will not encounter them.

During the sixteen years of my friend's collaboration with me in many enterprises for the spread of Freethought and the destruction of Superstition, he has written a vast variety of articles, all possessing distinctive merit, and some extremely valuable. From these he and I have made the following selection. The articles included deal with the Bible from a special standpoint; the standpoint of an Evolutionist, who reads the Jewish Scriptures in the light of anthropology, and finds infinite illustrations in them of the savage origin of religion.

Literary and scientific criticism of the Old Testament have their numerous votaries. Mr. Wheeler's mind is given to a different study of the older half of the Bible. He is bent on showing what it really contains; what religious ideas, rites, and customs prevailed among the ancient Jews and find expression in their Scriptures. This is a fruitful method, especially in our country, if it be true, as Dr. Tylor observes, that "the English mind, not readily swayed by rhetoric, moves freely under the pressure of facts."

Careful readers of this little book will find it full of precious information. Mr. Wheeler has a peculiarly wide acquaintance with the literature of these subjects. He has gathered from far and wide, like the summer bee, and what he yields is not an undigested mass of facts, but the pure honey of truth.

Many readers will be astonished at what Mr. Wheeler tells them. We have read the Bible, they will say, and never saw these things. That is because they read it without knowledge, or without attention. Reading is not done with the eyes only, but also with the brain; and the same sentences will make various impressions, according as the brain is rich or poor in facts and principles. Even the great, strong mind of Darwin had to be plentifully stored with biological knowledge before he could see the meaning of certain simple facts, and discover the wonderful law of Natural Selection.

Those who have studied the works of Spencer, Tylor, Lubbock, Frazer, and such authors, will not be astonished at the contents of this volume. But they will probably find some points they had overlooked; some familiar points presented with new force; and some fresh views, whose novelty is not their only virtue: for Mr. Wheeler is not a slavish follower of even the greatest teachers, he thinks for himself, and shows others what he has seen with his own eyes.

I hope this little volume will find many readers. Its doing so will please the author, for every writer wishes to be read; why else, indeed, should he write? Only less will be the pleasure of his friend who pens this Preface. I am sure the book will be instructive to most of those into whose hands it falls; to the rest, the few who really study and reflect, it will be stimulating and suggestive. Greater praise the author would not desire; so much praise cannot often be given with sincerity.

G. W. Foote.

"The hatred of indecency, which appears to us so natural as

to be thought innate, and which is so valuable an aid to

chastity, is a modern virtue, appertaining exclusively, as

Sir G. Staunton remarks, to civilised life. This is shown by

the ancient religious rites of various nations, by the

drawings on the walls of Pompeii, and by the practices of

many savages."—C. Darwin, "Descent of Man" pt. 1, chap.

iv., vol. i., p. 182; 1888.

The study of religions is a department of anthropology, and nowhere is it more important to remember the maxim of the pagan Terence, Homo sum, nihil humani a me alienum puto. It is impossible to dive deep into any ancient faiths without coming across a deal of mud. Man has often been defined as a religious animal. He might as justly be termed a dirty and foolish animal. His religions have been growths of earth, not gifts from heaven, and they usually bear strong marks of their clayey origin.*

* The Contemporary Review for June 1888, says (p. 804) "when

Lord Dalhousie passed an Act intended to repress obscenity

(in India), a special clause in it exempted all temples and

religious emblems from its operation."

I am not one of those who find in phallicism the key to all the mysteries of mythology. All the striking phenomena of nature—the alternations of light and darkness, sun and moon, the terrors of the thunderstorm, and of pain, disease and death, together with his own dreams and imaginations—contributed to evoke the wonder and superstition of early man. But investigation of early religion shows it often nucleated around the phenomena of generation. The first and final problem of religion concerns the production of things. Man's own body was always nearer to him than sun, moon, and stars; and early man, thinking not in words but in things, had to express the very idea of creation or production in terms of his own body. It was so in Egypt, where the symbol, from being the sign of production, became also the sign of life, and of regeneration and resurrection. It was so in Babylonia and Assyria, as in ancient Greece and Troy, and is so till this day in India.

Montaigne says:

"Fifty severall deities were in times past allotted to this office. And there hath beene a nation found which to allay and coole the lustful concupiscence of such as came for devotion, kept wenches of purpose in their temples to be used; for it was a point of religion to deale with them before one went to prayers. Nimirum propter continentiam incontinentia neces-saria est, incendium ignibus extinguitur: 'Belike we must be incontinent that we may be continent, burning is quenched by fire.' In most places of the world that part of our body was deified. In that same province some flead it to offer, and consecrated a peece thereof; others offered and consecrated their seed."

It is in India that this early worship maybe best studied at the present day. The worshippers of Siva identify their great god, Maha Deva, with the linga, and wear on their left arm a bracelet containing the linga and yoni. The rival sect of followers of Vishnu have also a phallic significance in their symbolism. The linga yoni (fig. 1) is indeed one of the commonest of religious symbols in India. Its use extends from the Himalayas to Cape Comorin. Major-General Forlong says the ordinary Maha Deva of Northern India is the simple arrangement shown in fig. 2, in which we see "what was I suspect the first Delphic tripod supporting a vase of water over the Linga in Yona. Such may be counted by scores in a day's march over Northern India, and especially at ghats or river ferries, or crossings of any streams or roads; for are they not Hermæ?" The Linga Purana tells us that the linga was a pillar of fire in which Siva was present. This reminds one of Jahveh appearing as a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night.

So astounded have been many writers at the phenomena presented by phallic worship that they have sought to explain it, not only by the story of the fall and the belief in original sin, but by the direct agency of devils.* Yet it may be wrong to associate the origin of phallic worship with obscenity. Early man was rather unmoral than immoral. Obliged to think in things, it was to him no perversion to mentally associate with his own person the awe of the mysterious power of production. The sense of pleasure and the desire for progeny of course contributed. The worship was indeed both natural and inevitable in the evolution of man from savagery. When, however, phallic worship was established, it naturally led to practices such as those which Herodotus, Diodorus, and Lucian tell us took place in the Egyptian, Babylonian, and Syrian religions.

* See Gougenot des Mousseaux's curious work Dieu et les

Dieux, Paris, 1854. When the Luxor monument was erected in

Rome, Pope Sixtus V. deliberately exorcised the devils out

of possession of it.

Hume's observation that polytheism invariably preceded monotheism has been confirmed by all subsequent investigation. The belief in one god or supreme spirit springs out of the belief in many gods or spirits. That this was so with the Jews there is sufficient evidence in the Bible, despite the fact that the documents so called have been frequently "redacted," that is corrected, and the evidence in large part erased. An instance of this falsification may be found in Judges xviii. 30 (see Revised Version), where "Manasseh" has been piously substituted for Moses, in order to conceal the fact that the direct descendants of Moses were image worshippers down till the time of the captivity. The Rabbis gave what Milton calls "this insulse rule out of their Talmud; 'That all words, which in the Law are written obscenely, must be changed to more civil words.' Fools who would teach men to read more decently than God thought good to write."* Instances of euphemisms may be traced in the case of the "feet" (Judges iii. 24, Song v. 3, Isaiah vii* 20); "thigh" (Num. v. 24); "heel" (Gen, iii. 15); "heels" (Jer. xiii. 22); and "hand" (Isaiah lvii. 7). This last verse is translated by Dr. Cheyne, "and behind the door and the post hast thou placed thy memorial, for apart from me thou hast uncovered and gone up; thou hast enlarged thy bed, and obtained a contract from them (?); thou hast loved their bed; thou hast beheld the phallus." In his note Dr. Cheyne gives the view of the Targum and Jerome "that 'memorial' = idol (or rather idolatrous symbol—the phallus)."

* "Apology for Smectymnus," Works, p.84.

The priests, whose policy it was to keep the nation isolated, did their best to destroy the evidence that the Jews shared in the idolatrous beliefs and practices of the nations around them. In particular the cult of Baal and Asherah, which we shall see was a form of phallic worship, became obnoxious, and the evidence of its existence was sought to be obliterated. The worship, moreover, became an esoteric one, known only to the priestly caste, as it still is among Roman Catholic initiates, and the priestly caste were naturally desirous that the ordinary worshipper should not become "as one of us."

It is unquestionable that in the earliest times the Hebrews worshipped Baal. In proof there is the direct assertion of Jahveh himself (Hosea ii. 16) that "thou shalt call me Ishi [my husband] and shalt call me no more Baali." The evidence of names, too, is decisive. Gideon's other name, Jerubbaal (Jud. vi. 32, and 1 Sam. xii. 11), was evidently the true one, for in 2 Sam. xi. 21, the name Jerubbesheth is substituted. Eshbaal (1 Chron. viii. 33) is called Ishbosheth (2 Sam. ii. 8, 10). Meribbaal (1 Chron. viii. 34) is Mephibosheth (2 Sam. iv. 4).* Now bosheth means v "shame," or "shameful thing," and as Dr. Donaldson points out, in especial, "sexual shame," as in Gen. ii. 25. In the Septuagint version of 1 Kings xviii. 25, the prophets of Baal are called "the prophets of that shame." Hosea ix. 10 says "they went to Baal-peor and consecrated themselves to Bosheth and became abominable like that they loved." Micah i. 11 "having thy Bosheth naked." Jeremiah xi. 5, "For according to the number of thy cities were thy gods, O Judah; and according to the number of the streets of Jerusalem have ye set up altars to Bosheth, altars to burn incense unto Baal."

* So Baaljadah [1 Chron. xiv. 7] is Eliada [2 Sam. v. 161.]

In 1 Chron. xii. 6, we have the curious combination,

Baaljah, i.e. Baal is Jah, as the name of one of David's

heroes.

The place where the ark stood, known afterwards as Kirjath-jearim, was formerly named Baalah, or place of Baal (I Chron. xiii. 6). The change of name took place after David's time, since the writer of 2 Sam. vi. 2 says merely that David went with the ark from "Baale of Judah."* Colenso notices that when the four hundred and fifty prophets of Baal are said to have been destroyed by Elijah, nothing is said of the four hundred prophets of the Asherah. "Also these same '400 prophets,' apparently, are called together by Ahab as prophets of JHVH, and they reply in the name of JHVH, 1 Kings xxii. 5-6."

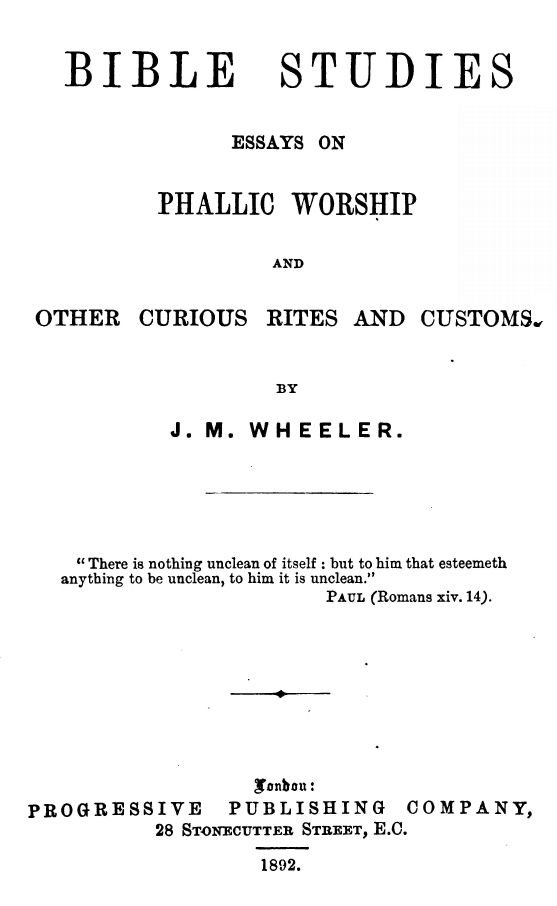

That phallicism was an important element in Baal and Asherah worship is well known to scholars, and will be made clear to discerning readers. The frequent allusion to "groves" in the Authorised Version must have puzzled many a simple student. The natural but erroneous suggestion of "tree worship" does not fit in very well with the important statement (2 Kings xxiii. 6) that Josiah "brought out the grove from the house of the Lord."** A reference to the Revised Version will show that this misleading word is intended to conceal the real nature of the worship of Asherah. The door of life, the conventional form of the Asherah with its thirteen flowers or measurements of time, is given in fig. 3.

* The "Baal" was afterwards taken out of all such names of

places, and instead of Baal Peor, Baal Meon, Baal Tamar,

Baal Shalisha, etc., we find Beth Peor, Beth Meon, Beth

Tamar, etc.

** Verse vii. says, "he brake down the houses of the

sodomites that were by the house of the Lord, where the

women wove hangings for the grove." A reference to the Revised

Version shows that it was "in the house of the Lord, where

the women wove hangings [or tents] for the Asherah." See

also Ezek. xvi. 16.

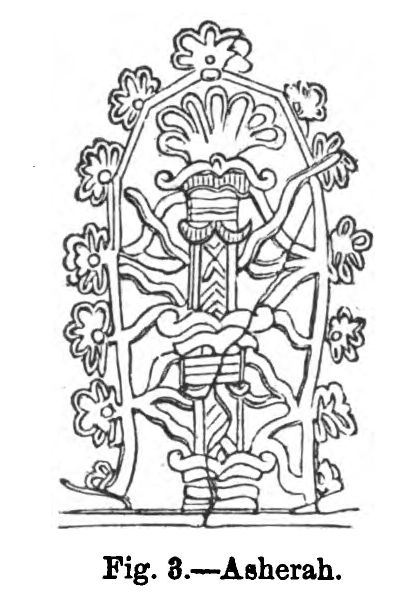

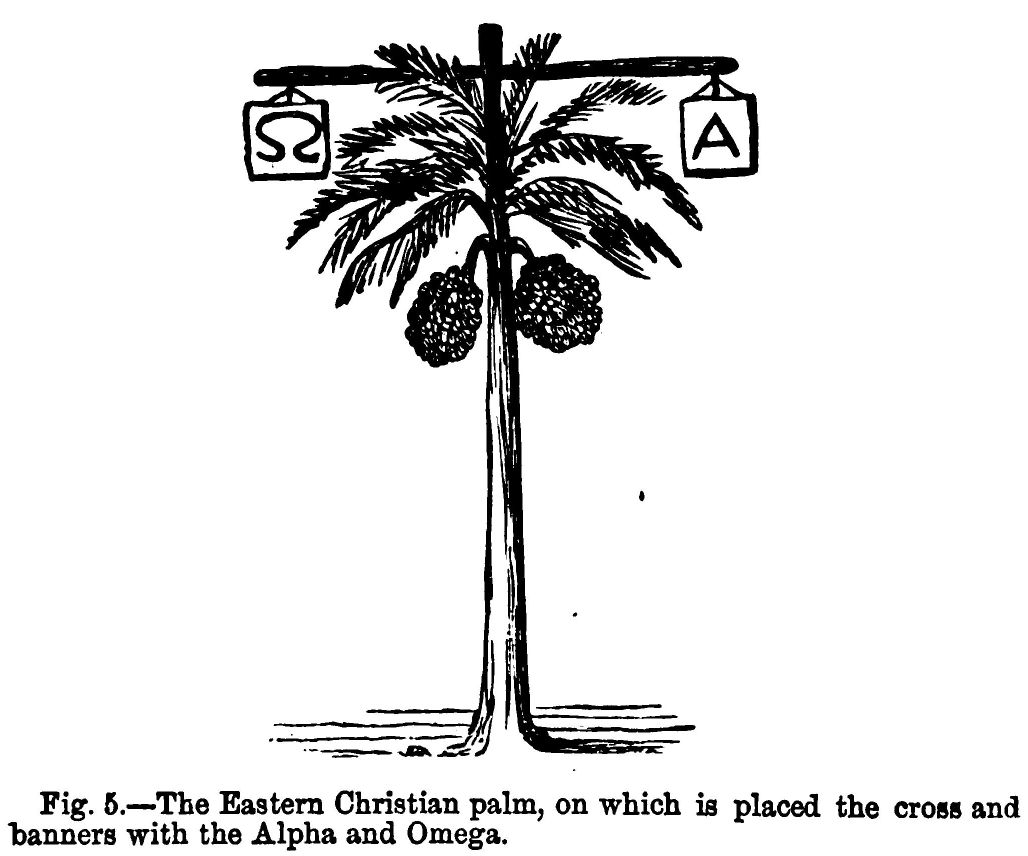

This worship certainly lasted from the earliest historic times until the seventeenth year of Josiah, B.C. 624. We read how in the days of the Judges they "served Baalim and the groves" (R.V., "the Asheroth"; Judges iii, 7; see ii. 12, "Baal and Ash-taroth.) We find that Solomon himself "went after Ashtoreth (1 Kings xi. 5) and that he builded the mount of corruption (margin, i.e., the mount of Olives) for that "abomination of the Zidonians" (2 Kings xxiii. 13). All the distinctive features of Solomon's Temple were Phoenician in character. What the Phoenician temples were like Lucian tells us in his treatise on the goddess of Syria. The great pillars Jachin, "the establisher," and Boaz, "strength"; the ornamentation of palm trees, pomegranates, and lotus work; are all Phoenician and all phallic. The bells and pomegranates on the priests' garment were emblematic of the paps and full womb. The palm-tree, which appears both in Solomon's temple and in Ezekiel's vision, was symbolical, as may be seen in the Assyrian monument (fig. 4), and which finds a place in Eastern Christian symbolism, with the mystic alpha and omega (fig. 5).

The worship of Astoreth, the Assyrian Ishtar, and Greek Astarte, was widespread. The Phoenicians took it with them to Cyprus and Carthage. In the days of Abraham there was a town called after her (Gen. xiv. 5), and to this day her name is preserved in Esther.

It is she who is called the Queen of Heaven, to whom the women made moon-shaped cakes and poured libations (Jer. vii. 18, xliv. 17.) Baal represented the generative, Astoreth the productive power. The pillars and asherah, so often alluded to in the Bible, were the palm-tree, with male and female animals frolicking around the tree of life, the female near the fleur de lis and the male near the yoni. Tall and straight trees, especially the palm, were reverenced as symbols. Palm branches carried in procession were signs of fruitfulness and joy.

Bishop Colenso in his notes to Dr. Oort's work remarks, "It seems plain that the Ashera (from ashar, be straight, erect) was in reality a phallus, like the Linga or Lingam of the Hindoos, the sign of the male organ of generation."**

* The Worship of Baalim and Israel, p. 46.

** Asher was the tutelary god of Assyria. His emblem was the

winged circle.

There can be little doubt on the matter in the mind of anyone acquainted with ancient faiths and the inevitable phases of human evolution, We read (1 Kings xv. 13, Revised Version), that Maachah, the queen mother of Asa, "made an abominable image for an Asherah." This the Vulgate translates "Priape" and Movers pudendum. Jeremiah, who alludes to the same thing (x. 5), tells that the people said, "to a stock, Thou art my father, and to a stone, Thou hast brought me forth" (ii. 27), that they "defiled the land and committed adultery with stones and with stocks" (iii. 9), playing the harlot "under every green tree" (ii. 20, iii. 6, 13; see also Hosea iv. 13). Isaiah xvii. 8, alludes to the Asherim as existing in his own days, and alludes to these religions in plain terms (lvii. 5—8). Micah also prophesies against the "pillars" and "Asherim" (v. 13, 14). Ezekiel xvi. 17, says "Thou hast also taken thy fair jewels, of my gold and of silver, which I have given thee, and madest to thyself images of men, and didst commit whoredom with them." The margin more properly reads images "Heb. of a male" [tsalmi zachar], a male here being an euphemism. As Gesenius says of the metaphor in Numbers xxiv. 7 these things are "ex nostra sensu obscoena, sed Orientalibus familiaria."

These images are alluded to and prohibited in Deut. iv. 16. It is thus evident that some form of phallic worship lasted among the Jews-from the earliest times until their captivity in Babylon.

It is a most significant fact that the Jews used one and the same word to signify both "harlot" and "holy." "There shall be no kedeshah of the daughters of Israel" (Deut. xxiii. 17) means no female consecrated to the temple worship. Kuenen says "it is natural to assume that this impurity was practised in the worship of Jahveh, however much soever the lawgiver abhors it." It must be noticed, too, that there is no absolute prohibition. It only insists that the slaves of desire shall not be of the house of Israel, and stipulates that the money so obtained shall not be dedicated to Jahveh. That this was the custom both in Samaria and Jerusalem, as in Babylon, may be gathered from Micah i. 7, and Hosea iv. 14.

Dr. Kalisch, by birth a Jew and one of the most fair-minded of biblical scholars, says in his note on Leviticus xix. 29: "The unchaste worship of Ashtarte, known also as Beltis and Tanais, Ishtar, Mylitta, and Anaitis, Asherah and Ashtaroth, flourished among the Hebrews at all times, both in the kingdom of Judah and Israel; it consisted in presenting to the goddess, who was revered as the female principle of conception and birth, the virginity of maidens as a first-fruit offering; and it was associated with the utmost licentiousness. This-degrading service took such deep root, that in the Assyrian period it was even extended by the adoption of new rites borrowed from Eastern Asia, and described by the name of 'Tents of the Maidens' (Succoth Benoth); and it left its mark in the Hebrew language itself, which ordinarily expressed the notion courtesan by 'a consecrated woman' (Kadeshah), and that of sodomite by 'consecrated man' (Kadesh)."

The Succoth Benoth in 2 Kings xvii. 30, may be freely rendered Tabernacles of Venus. Venus is plausibly derived from Benoth, whose worship was at an early time disseminated from Carthage and other parts of Africa to the shores of Italy. The merriest festival among the Jews was the Feast of Tabernacles. Plutarch (who suggests that the pig was originally worshipped by the Jews, a position endorsed by Mr. J. G. Frazer, in his Golden Bough, vol. ii., pp. 52, 53) says the Jewish feast of Tabernacles "is exactly agreeable to the holy rites of Bacchus."* He adds, "What they do within I know not, but it is very probable that they perform the rites of Bacchus."

* Symposiacs, bk. iv., queat. 6, p. 310, vol. iii.,

Plutarch's Morals, 1870.

Dr. Adam Clarke, in his Commentary on 2 Kings xvii. 30, gives the following:—"Succoth-benoth maybe literally translated, The Tabernacle of the Daughters, or Young Women; or if Benoth be taken as the name of a female idol, from birth, to build up, procreate, children, then the words will express the tabernacles sacred to the productive powers feminine. And, agreeably to this latter exposition, the rabbins say that the emblem was a hen and chickens. But however this may be, there is no room to doubt that these succoth were tabernacles, wherein young women exposed themselves to prostitution in honor of the Babylon goddess Melitta." Herodotus (lib. i., c. 199; Rawlinson) says: "Every woman born in the country must once in her life go and sit down in the precinct of Venus, and there consort with a stranger. Many of the wealthier sort, who are too proud to mix with the others, drive in covered carriages to the precinct, followed by a goodly train of attendants, and there take their station. But the larger number seat themselves within the holy enclosure with wreaths of string about their heads; and here there is always a great crowd, some coming and others going; lines of cord mark out paths in all directions among the women, and the strangers pass along them to make their choice. A woman who has once taken her seat is not allowed to return home till one of the strangers throws a silver coin into her lap, and takes her with him beyond the holy ground. When he throws the coin he says these words—'The goddess Mylitta prosper thee" (Venus is called Mylitta by the Assyrians). The silver coin may be of any size; it cannot be refused, for that is forbidden by the law, since once thrown it is sacred. The woman goes with the first man who throws her money, and rejects no one. When she has gone with him, and so satisfied the goddess, she returns home, and from that time forth no gift, however great, will prevail with her. Such of the women as are tall and beautiful are soon released, but others who are ugly have to stay a long time before they can fulfil the law. Some have waited three or four years in the precinct. A custom very much like this is also found in certain parts of the island of Cyprus." This custom is alluded to in the Apocryphal Epistle of Jeremy (Barch vi. 43): "The women also with cords about them sitting in the ways, burnt bran for perfume; but if any of them, drawn by some that passeth by, lie with him, she reproacheth her fellow, that she was not thought as worthy as herself, nor her cord broken." The Commentary published by the S. P. C. K. says, "Women with cords about them," the token that they were devotees of Mylitta, the Babylonian Venus, called in 2 Kings xvii. 30, 'Succoth-benoth,' the ropes denoting the obligation of the vow which they had taken upon themselves." Valerius Maximus speaks of a temple of Sicca Venus in Africa, where a similar custom obtained. Strabo also mentions the custom (lib. xvi., c. i., 20), and says, "The money is considered as consecrated to Venus." In book xi., c. xiv., 16, Strabo says the Armenians pay particular reverence to Anaïtes. "They dedicate there to her service male and female slaves; in this there is nothing remarkable, but it is surprising that persons of the highest rank in the nation consecrate their virgin daughters to the goddess. It is customary for these women, after being prostituted a long period at the temple of Anaites, to be disposed of in marriage, no one disdaining a connection with such persons. Herodotus mentions something similar respecting the Lydian women, all of whom prostitute themselves." Of the temple of Venus at Corinth, Strabo says "it had more than a thousand women consecrated to the service of the goddess, courtesans, whom men and women had dedicated as offerings to the goddess"; and of Comana, in Cappadocia, he has a similar relation (bk. xii., c. iii., 36).

Dr. Kalisch also says Baal Peor "was probably the principle of generation par excellence, and at his festivals virgins were accustomed to yield themselves in his honor. To this disgraceful idolatry the Hebrews were addicted from very early times; they are related to have already been smitten on account of it by a fearful plague which destroyed 24,000 worshippers, and they seem to have clung to its shameful practices in later periods."* Jerome says plainly that Baal-Peor was Priapus, which some derive from Peor Apis. Hosea says (ix. 10, Revised Version) "they came to Baal-Peor and consecrated themselves unto the shameful thing, and became abominable like that which they loved"; see, too, Num. xxvi. 1, 3. Amos (ii. 7,8) says a son and a father go in unto the same maid in the house of God to profane Jahveh's holy name, so that it appears this "maid" was regarded as in the service of Jahveh. Maimonides says it was known that the worship of Baal-Peor was by uncovering of the nakedness; and this he makes the reason why God commanded the priests to make themselves breeches to wear at the time of service, and why they might not go up to the altar by steps that their nakedness might not be discovered.** Jules Soury says*** "The tents of the sacred prostitutes were generally erected on the high places."

* Leviticus, p. 364.

** That even more shameful practices were once common is

evident from the narratives in Genesis xix. and Judges xix.

*** Religion of Israel chap. ix., p. 71.

**** Leviticus, part i., p. 383. Kork, Die Gotter Syrian, p.

103, says the pillars and Asherah stood in the adytum, that

is the holy of holies, which represented the genetrix.

In the temple at Jerusalem the women wove hangings for the Asherah (2 Kings xxiii. 7), that is for concealment in the worship of the genetrix, and in the same precincts were the houses of prostitute priests (see also 1 Kings xiv. 24; xv. 12; xxii. 46. Luther translates "Hurer"). Although Josiah destroyed these, B.C. 624, Kalisch says "The image of Ashtarte was probably erected again in the inner court (Jer. xxxii. 34; Ezek. viii. 6)." Ezekiel says (xvi. 16), "And of thy garments thou didst take, and deckedst thy high places with divers colors and playedst the harlot thereupon," and (v. 24) "Thou hast also built unto thee an eminent place, and hast made thee a high place in every street," which is plainly translated in the Roman Catholic Douay version "Thou didst also build thee a common stew and madest thee a brothel house in every street." The "strange woman," against whom the Proverbs warns, practised her profession under cover of religion (see Prov. vii. 14). The "peace offerings" there alluded to were religious sacrifices.

Together with their other functions the Kadeshah, like the eastern nautch girls and bayaderes, devoted themselves to dancing and music (see Isaiah xxiii. 16). Dancing was an important part of ancient religious worship, as may be noticed in the case of King David, who danced before the ark, clad only in a linen ephod, probably a symbolic emblem (see Judges viii. 27), to the scandal of his wife, whom he had purchased by a trophy of two hundred foreskins from the uncircumcised Philistines (1 Sam. xviii. 27; 2 Sam. vi. 14-16). When the Israelites worshipped the golden calf they danced naked (Exodus xxxii. 19, 25). They sat down to eat and to drink, and rose up to play, the word being the same as that used in Gen. xxvi. 8. The word chag is frequently translated "feast," and means "dance." In the wide prevalence of sacred prostitution Sir John Lubbock sees a corroboration of his hypothesis of communal marriage. Mr. Wake, however, refers it to the custom of sexual hospitality, a practice widely spread among all savage races, the rite like that of blood covenanting being associated with ideas of kinship and friendliness.

We have seen that the early Jews shared in the phallic worship of the nations around them. Despite the war against Baal and Asherah worship by the prophets of Jahveh, it was common in the time of the Judges (iii. 7). Solomon himself was a worshipper of Ashtoreth, a faith doubtless after the heart of the sensual sultan (1 Kings xi. 5). The people of Judah "built them high places and phalli and ashera on every high hill and under every green tree. And there were also Sodomites in the land" (1 Kings xiv. 23, 24). The mother of Asa made "an abominable image for an Asherah" (1 Kings xv. 13).* The images of Asherah were kept in the house of Jahveh till the time of Josiah (2 Kings xxiii. 6). Dr. Kuenen says (Religion of Israel, vol. i., p. 80), "the images, pillars and asheras were not considered by those who worshipped them as antagonistic to the acknowledgment of Jahveh as the God of Israel." The same writer contends that Jeroboam exhibiting the calves or young bulls could truly say "These be thy gods, O Israel." Remembering, too, that every Jew bears in his own body the mark of a special covenant with the Lord, the reader may take up his Bible and find much over which pious preachers and commentators have woven a pretty close veil. I will briefly notice a few particulars.

* Larousse, in his Grande Dictionnaire Universelle, says:

"Le phallos hébraique fut pedant neuf cent ans le rival

souvent victorieux de Jéhovah."

Without going into the question of the translation of Genesis i. 2, it is evident from v. 27 that God is hermaphrodite. "So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him, male and female (zakar and nekaba) created he them."

It is not difficult to find traces of phallicism in the allegory of the Garden of Eden. This has been noticed from the earliest times. The rabbis classed the first chapters of Genesis with the Song of Solomon and certain portions of Ezekiel as not to be read by anyone under thirty. The Manichæans and other early Christians held the phallic view. Clement of Alexandria (Strom iii.) admits the sin of Adam consists in a premature indulgence of the sexual appetite. This view explains why knowledge was prohibited and why the first effect of the fall was the perception of nakedness. Basilides contended that we should reverence the serpent because it induced Eve to share the caresses of Adam, without which the human race would never have existed. Many modern writers, notably Beverland and Dr. Donaldson, have sustained the phallic interpretation. Archbishop Whately is also said to have advocated a similar opinion in an anonymous Latin work published in Germany. Dr. Donaldson, who was renowned as a scholar, makes some curious versions of the Hebrew. His translation of the alleged "Messianic promise" in Genesis iii. 15, his adversary, Dr. Perowne, the present Dean of Peterborough, says, is "so gross that it will not bear rendering into English." A good Hebraist, a Jew by birth, who had never heard of Dr. Donaldson's Jashar, gave me an exactly similar rendering of this verse—which makes it a representation of coition—and instanced the phrase "the serpent was more subtle than the other beasts of the field," as an illustration of early Jewish humor.

The French physician, Parise, eloquently says: "This sublime gift of transmitting life—fatal perogative, which man continually forfeits—at once the mainstay of morality by means of family ties, and the powerful cause of depravity—the energetic spring of life and health—the ceaseless source of disease and infirmity—this faculty involves almost all that man can attain of earthly happiness or misfortune, of earthly pleasure or of pain; and the tree of knowledge, of good and evil, is the symbol of it, as true as it is expressive."

Dr. Adam Clarke was so impressed by the difficulty of the serpent having originally gone erect, that he thinks that nachash means "a creature of the ape or ourang-outang kind." Yet it has been suggested that a key to the word may be found in Ezekiel xvi. 36, where it is translated "filthiness." There is nothing whatever in the story to show that the serpent is the Devil. This was an after idea when the Devil had become the symbol of passion and the instigator of lust. De Gubernatis, in his Zoological Mythology (vol. ii., p. 399), says "The phallical serpent is the cause of the fall of the first man." Many other difficulties in the story become less obscure when it is viewed as a remnant in which a phallic element is embodied.

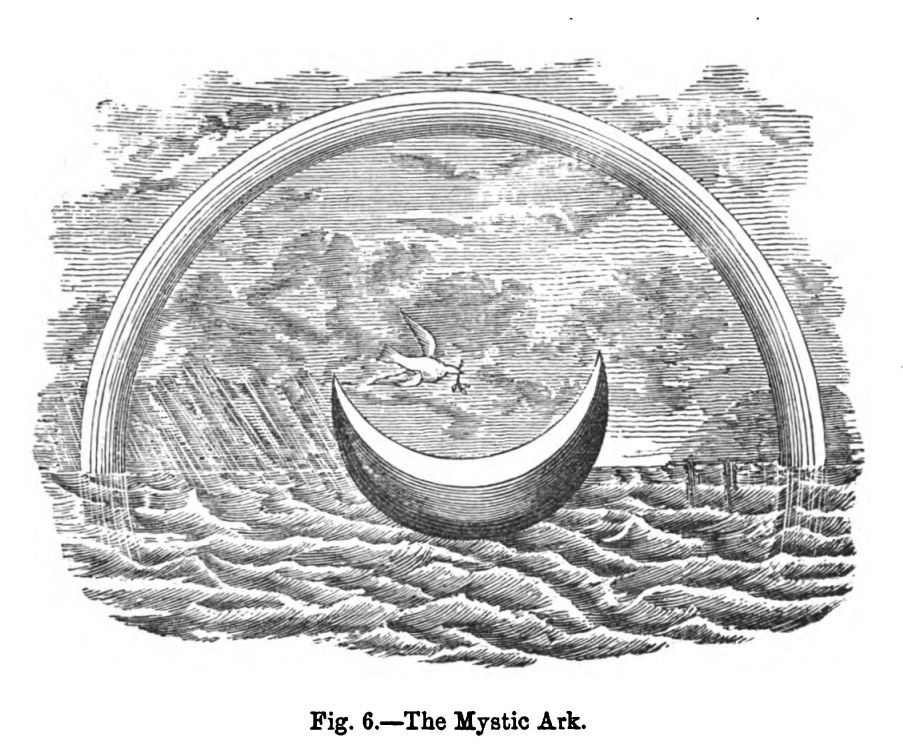

Some have detected a phallic signification in the story of the ark and the deluge, a legend capable of many interpretations. The phallic view is represented in the symbols in fig. 6, taken from Jacob Bryant's Mythology, vol. iv., p. 286, in which the rainbow overshadows the mystic ark, which carries the life across the restless flood of time, which drowns everything that has life, and promises that seed-time and harvest shall endure, and the Ruach broods over the waters. Gerald Massey devotes a section of his Natural Genesis to the typology of the Ark and the Deluge. M. Clermont-Ganneau holds that the Ruach was the feminine companion of Elohim, and that this idea was continued under the name of Kodesh the Euach Kodesh or Holy Ghost, which with the Jews and early Nazarene Christians was feminine.

Another point to be briefly noticed is Jacob's anointing of the stone which he slept on, and then erected and called Beth El, or "house of God," the residence of the creative spirit. This was a phallic rite. Exactly the same anointing of the linga is performed in India till this day. It is evident that Jacob's worship of the pillar was orthodox at the time the narrative was written, for God sends him back to the pillar to perform his vow (see Gen. xxxv.), and again he goes through phallic rites (v. 14). When Paul says, "Flee fornication. Know ye not that your body is the temple of the Holy Ghost?" he elevates and spiritualises the conception which lay in the word Bethel. According to Philo Byblius, the huge stones common in Syria, as in so many lands, were called Baetylia. Kalisch says it is not extravagant to suppose that the words are identical. From this custom of anointing comes the conception of the Messiah, or Christ the Anointed. Kissing the stone or god appears also to have been a religious rite. Thus we read of kissing Baal (1 Kings xix. 18) and kissing the "calves" (Hos. xiii. 2). Epi-phanius said that the Ophites kissed the serpent which this wretched people called the Eucharist. They concluded the ceremonies by singing a hymn through him to the Supreme Father. (See Fergusson's Tree and Serpent Worship, p. 9.) The kissing of the Mohammedan saint's member and of the Pope's toe are probably connected. Amalarius, who lived in the age of Charlemagne, says that on Friday (Dies Veneris) the Pope and cardinals crawl on all fours along the aisles of St. Peter's to a cross before an altar which they salute and kiss.

Mr. Grant Allen, in an article on Sacred Stones in the Fortnightly Review, Jan., 1890, says:

"Samuel judged Israel every year at Bethel, the place of Jacob's sacred pillar; at Gilgal, the place where Joshua's twelve stones were set up; and at Mizpeh, where stood the cairn surmounted by the pillars of Laban's servant. He, himself, 'took a stone and set it up between Mizpeh and Shen'; and its very name, Ebenezer, 'the stone of help,' shows that it was originally worshipped before proceeding on an expedition, though the Jehovistic gloss, 'saying Hitherto the Lord hath helped us,' does its best, of course, to obscure the real meaning. It was to the stone circle of Gilgal that Samuel directed Saul to go down, saying; 'I will come down unto thee, to offer burnt offerings, and to sacrifice sacrifices of peace offerings.' It was at the cairn of Mizpeh that Saul was chosen king; and after the victory over the Ammonites, Saul went once more to the great Stonehenge at Gilgal to 'review the kingdom,' and 'There they made Saul king before Jahveh in Gilgal; and there they sacrificed sacrifices of peace offerings before Jahyeh.'"

This last passage, as Mr. Allen points out, is very instructive, as showing that in the opinion of the writer, Jahveh was then domiciled at Gilgal.

M. Soury, in his note to chap. ii. of his Religion of Israel, says: "It is needful to point out, with M. Schrader, that the most ancient Babylonian inscriptions in the Accadian tongues, those of Urukh and of Ur Kasdim, preserved in the British Museum, were engraved on clay phalii. We have here the origin of the usages and customs of religion so long followed among the Oanaanites and Hebrews (Y. Movers, Die Phonizer, I., 591, et passim)."

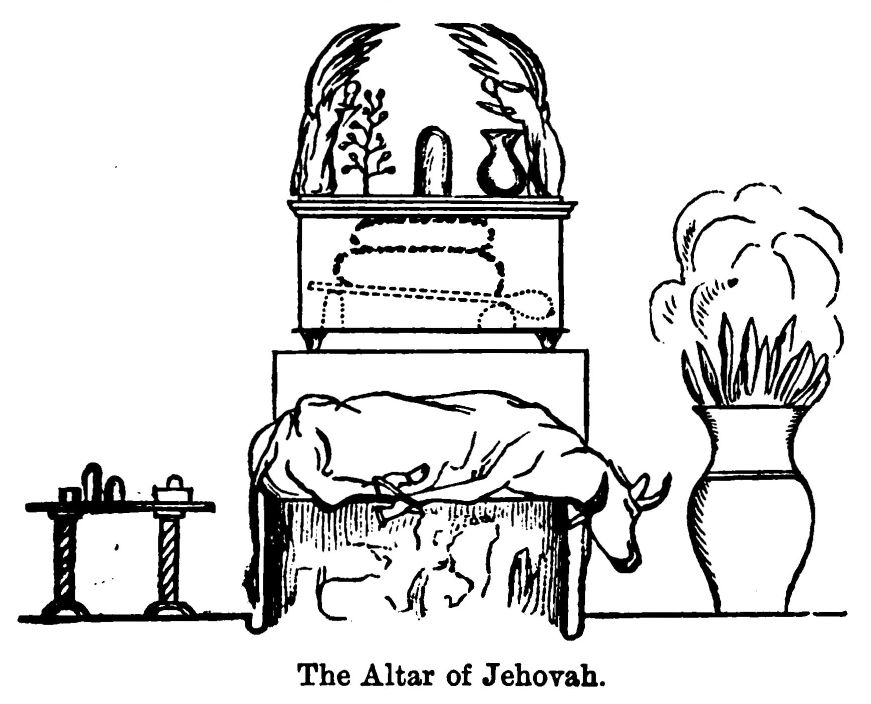

In the old hymn embodied in Deut. xxxii., God is frequently called Tsur, "The Rock which begat thee," etc. Major-General Forlong believes "that the Jews had a Phallus or phallic symbol in their 'Ark of the Testimony' or Ark of the Eduth, a word which I hold tries to veil the real objects" (Rivers of Life, vol. i., p. 149). He does not scruple to say this was "the real God of the Jews; that God of the Ark or the Testimony, but surely not of Europe" (vol. i., p. 169). This contention is forcibly suggested by the picture of the Egyptian Ark found in Dr. Smith's Bible Dictionary, art.

"Ark of the Covenant." The Ark of the Testimony, or significant thing, the tabernacle of the testimony and the veil of the testimony alluded to in Exodus are never mentioned in Deuteronomy. The Rev. T. Wilson, in his Archaeological Dictionary, art. "Sanctum," observes that "the Ark of the Covenant, which was the greatest ornament of the first temple, was wanting in the second, but a stone of three inches thick, it is said, supplied its place, which they [the Jews] further assert is still in the Mahommedan mosque called the temple of the Stone, which is erected where the Temple of Jerusalem stood." This forcibly suggests that the nature of the "God in the box" which the Jews carried about with them was similar to that carried in the processions of Osiris and Dionysos. According to 1 Kings viii. 9 the Ark contained two stones, but the much later writer of Heb. ix. 4 makes it contain the golden pot with manna, Aaron's rod, and the tables of the covenant.

Mr. Sellon, in the papers of the Anthropological Society of London, 1863-4, p. 327, argues: "There would also now appear good ground for believing that the ark of the covenant, held so sacred by the Jews, contained nothing more nor less than a phallus, the ark being the type of the Argha or Yoni (Linga worship) of India." Hargrave Jennings (Phallicism, p. 67) says: "We know from the Jewish records that the ark contained a table of stone.... That stone was phallic, and yet identical with the sacred name Jehovah, which, written in unpointed Hebrew with four letters, is JEVE, or JHVH (the H being merely an aspirate and the same as E). This process leaves us the two letters I and V (in another form, U); then, if we place the I in the V, we have the 'Holy of Holies'; we also have the Linga and Yoni and Argha of the Hindus, the Isvara and 'Supreme Lord'; and here we have the whole secret of its mystic and arc-celestial import confirmed in itself by being identical with the Ling-yoni of the Ark of the Covenant."

In Hosea, who finds it quite natural that the Lord should tell him "Go take unto thee a wife of whoredoms," we find the Lord called his zakar (translated memorial, xii. 5). In the same prophet we read that Jahveh declares thou shalt call me Ishi (my husband); and shalt no more call me Baali (ii. 16). Again he says to his people "I am your husband" (Hosea iii. 14); "Thy maker is thine husband; Jahveh Sabaoth is his name" (Isaiah liv. 5). I was an husband to them, saith Jahveh (Jer. xxxi. 32. See also Jer. iii. 20 and Ezek. xvi. 32). God even does not scruple to represent himself in Ezekiel xxiii. as the husband of two adulterous sisters. Taking to other deities is continually called whoring and adultery. See Exod. xxxiv. 15, 16; Lev. xx. 5; Num. xxv. 1-3; Deut. xxxi. 16; xxxii. 16-21; Jud. ii. 17; viii. 27; 1 Chron. v. 25; Ps. lxxiii. 27; cvi. 39; Jer. iii. 1, 2, 6; Ezek. xvi. 15, 17; xxiii. 3; Hos. i. 2; ii. 4, 5; iv. 13, 15; v. 3, 4; ix. 7. In the Wisdom of Solomon (xiv. 12), we read: "For the devising of idols was the beginning of spiritual fornication, and the invention of them the corruption of life." Here the word "spiritual" is deliberately inserted to pervert the meaning. Let any one reflect how such coarse expressions could continually be used unless the writers were used to phallic worship. Further consider the narrative in Numbers xxxi., where the Lord takes a maiden tribute out of 32,000 girls, who must all have been examined. Vestal virgins and nuns are all consecrated like the kadeshim to the god, and the god is personified by the priest. In this sense phallicism is the key of all the creeds.

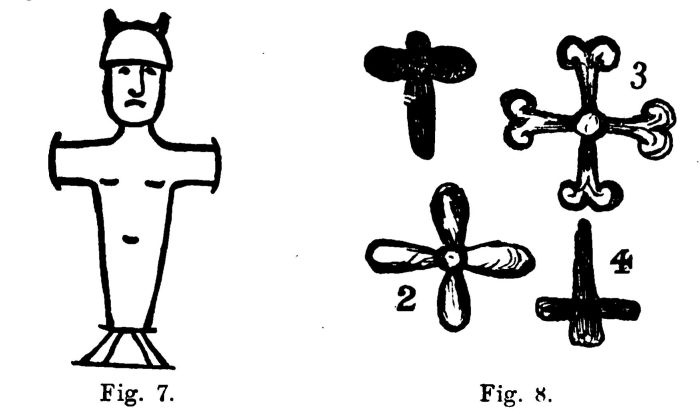

That some remnants of phallicism may be traced even in Christianity, will be evident to the readers of Anacalypsis, by Godfrey Higgins; Ancient Faiths Embodied in Ancient Names, by Dr. Thomas Inman, and Ancient Pagan and Modern Christian Symbolism Exposed and Explained, by the same author; the valuable Rivers of Life, by Major-General Forlong; a little book on Idolomania, by "Investigator Abhorrens"; and another on The Masculine Cross, by Sha Rocco (New York, 1874). The sign of the cross, certainly long pre-Christian in the Egyptian sign for life, is specially dealt with in the last two works. In fig. 7 we see the connection of the Egyptian tau with the Hermæ. Of fig. 8 General Forlong (Rivers of Life, vol i., p 65) says: "The Samaritan cross, which they stamped on their coins, was No. 1, but the Norseman preferred No. 2 (the circle and four stout arms of equal size and weight), and called it Tor's hammer. It is somewhat like No. 3, which the Greek Christians early adopted, though this is more decidedly phallic, and shows clearly the meaning so much insisted on by some writers as to all meeting in the centre."

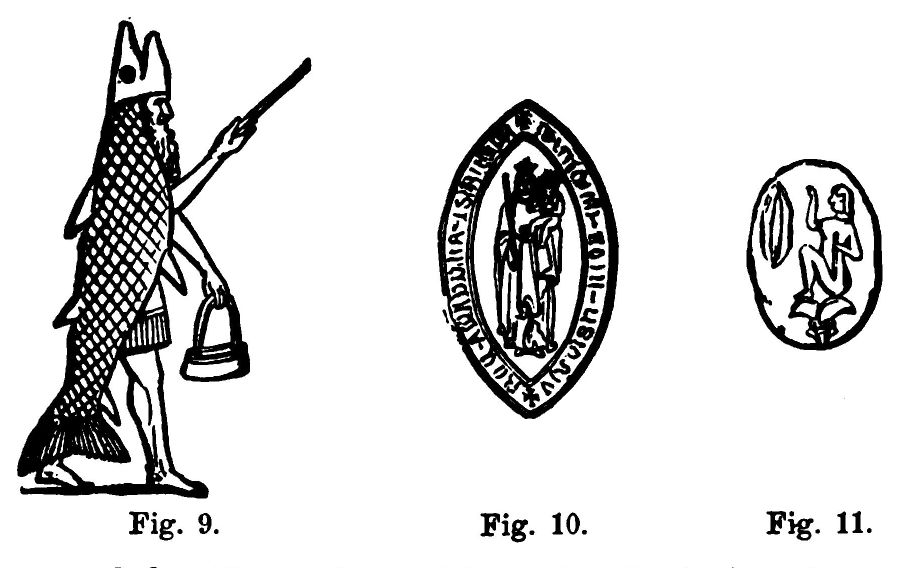

The custom of eating fish on Friday (Dies Veneris) is considered a survival of the days when a peculiar sexual signification was given to the fish, which has such a prominent place in Christian symbolism. Fig. 9 illustrates the origin of the bishop's mitre.

The vescica piscis, or fish's bladder (fig. 10), is a well-known ecclesiastical emblem of the virgin, often used in church windows, seals, etc. The symbol is equally known in India. Its real nature is shown in fig. 11, discovered by Layard at Nineveh, depicting its worshipper seated on a lotus. The vescica piscis is conspicuously displayed in fig. 12, copied from a Rosary of the Blessed Virgin, printed at Venice 1582, with the license from the Inquisition, in which the Holy Dove darts his ray, fecundating the Holy Virgin. Many instances of Christ in an elliptical aureole may be seen in Didron's Christian Iconography, fig. 71, p. 281, vol. i. strikingly resembles our figure.

Among the many traces that the Jews were once savages I place the distinguishing mark of their race, circumcision. Many explanations have been given of this curious custom. The account, in Genesis xvii. that God commanded it to Abraham, at the ripe age of 99, critics agree was written after the exile—that is, thirteen hundred years after the death of the patriarch. Now, there is evidence from the Egyptian monuments that circumcision was known long before Abraham's time. This constrains Dr. Kitto to say, "God might have selected a practice already in use among other nations." If so, God must have had a curious taste and an uninventive mind. Why, having made people as they are, he should order his chosen race to be mutilated, must be a puzzle to the orthodox. Some writers have absurdly argued that the Egyptians borrowed from the Jews, whom they despised (see Genesis xliii. 32). Apart from the evidence of Herodotus and of monuments and mummies to the contrary, this view is never suggested in the Bible, but the testimony of the book of Joshua (v. 9) implies the reverse.

The narrative of the Lord's attempted assassination of Moses (Exodus iv. 24-26), which we shall shortly examine, has the most archaic complexion of any of the biblical references to circumcision, and from it Dr. T. K. Cheyne argues that the rite is of Arabian origin.* If instituted in the time of Abraham under the penalty of death, it is curious that Moses never circumcised his own son, nor saw to its performance in the wilderness for forty years, so that Joshua had personally to circumcise over a million males at Gilgal.

Let us now look at the various theories of the origin and purpose of circumcision. Rationalising Jews say it is of a sanatory character. This view, though found in Philo, may be dismissed as an after theory to meet a religious difficulty. Most Asiatic nations are uncircumcised. The Philistines did not practice the rite, nor did the Syrians in the time of Josephus. Even if in a few cases it might possibly be beneficial, that would be no sufficient reason for imposing it on a whole nation under penalty of death. The fact is, the rite is a religious one. Indeed, upon its retention the early controversy between Jews and Christians largely turned.

The view that it is an imposed mutilation of a subject race is suggested in Dr. Remondino's History of Circumcision, and has the high authority of Herbert Spencer. He instances the trophy of foreskins taken by David as a dowry for Saul's daughter (1 Sam. xviii. 27), and that Hyrcanus having subdued the Idumeans, made them submit to circumcision. This, however, may have been a part of the policy of making them one with the Jewish race in being tributary to Jahveh. It is not easy to see how a mutilation imposed from without should ever become a part of the pride of race and be enjoined when all other mutilations were forbidden.

* Encyclopaedia Britannica, article "Circumcision."

I incline to a view which, although in accord with early sociological conditions, I have never yet seen stated. It was suggested to me by the passage where Tacitus alludes to this custom among the Jews. It is that circumcision is of the nature of savage totem and tattoo marks—a device to distinguish the tribal division from other tribes, and to indicate those with whom the tribe might marry.* If, as has been suggested, the meaning of Genesis xxxiv. 14 is "one who is uncircumcised is as a woman to us," this view is confirmed. The Jewish abhorrence to mixed marriages and "the bed of the uncircumcised" is well known.

* What Tacitus says is, "They do not eat with strangers or

make marriages with them, and this nation, otherwise most

prone to debauchery, abstains from all strange women. They

have introduced circumcision in order to distinguish

themselves thereby."

The Hebrew distinguishing term for male—zachar, which also means record or memorial—will agree with this view, as also with that of Dr. Trumbull, which associates circumcision with that of blood-covenanting. It seems evident from the narrative in Exodus iv., where Zipporah, after circumcising her son, says—not as generally understood to Moses—"A bloody husband art thou to me," but to Jahveh, "Thou art a Kathan of blood"—i.e., one made akin by circumcision—that this idea of a blood-covenant became interwoven with the rite. It is to be noticed that in the covenant between God and the Jews women had no share.

Dr. Kuenen holds that circumcision is of the nature of a substitute for human sacrifice. No doubt the Jews had such sacrifices, and were familiar with the idea of substitution; but with this I rather connect the Passover observance. If a sacrifice, it was doubtless phallic—an offering to the god on whom the fruit of the womb depended; possibly a substitution for the barbarous rites by which the priests of Cybele were instituted for office. Ptolemy's Tetrabibles, speaking of the neighboring nations, says: "Many of them devote their genitals to their divinities." According to Gerald Massey, "it was a dedication of the first-fruits of the male at the shrine of the virgin mother and child, which was one way of passing the seed through the fire to Moloch."

Westrop and Wake (Phallicism in Ancient Religion, p. 37) say "Circumcision, in its inception, is a purely phallic rite, having for its aim the marking of that which from its associations is viewed with peculiar veneration, and it converts the two phases of this superstition which have for their object respectively the instrument of generation and the agent."

General Forlong, who maintains the phallic view, also holds that "truth compels us to attach an Aphrodisiacal character to the mutilations of this highly sensual Jewish race." This view will not be hastily rejected by those who know of the many strange devices resorted to by barbarous peoples. Some have believed that circumcision enhances fecundity.

With the exception of the two first views, which I dismiss as not explaining the religious and permanent character of the rite, all these views imply a special regard being paid to the emblem of generation. This is further confirmed by the manner of oath-taking customary among the ancient Jews. When Abraham swore his servant, he said, "Put, I pray thee, thy hand under my thigh" (Gen. xxiv. 2). The same euphemism is used in the account of Jacob swearing Joseph (xlvii. 29), and the custom, which has lasted among Arabs until modern days, is also alluded to in the Hebrew of 1 Chronicles xxix. 24. The Latin testiculi seems to point to a similar custom. In the law that no uncircumcised or sexually-imperfect person might appear before the shrine of the Lord, we may see yet further evidence that Jewish worship was akin to the phallic rites of the nations around them.

And it came to pass by the way in the inn, that the lord met him, and sought to kill him. Then Zipporah took a sharp stone, and cut off the foreskin of her son, and cast it at his feet, and said,

Surely a bloody husband art thou to me.

So he let him go: then she said,

A bloody husband thou art, because of the circumcision.

—Exodus iv. 24-26.

Anyone who wishes to note the various shifts to which orthodox people will resort in their attempts to pass off the barbarous records of the Jews as God's holy word, should demand an explanation of the attempted assassination of Moses by Jehovah, as recorded in the above verses. Some commentators say that by the Lord is meant "the angel of the Lord," as if Jehovah was incapable of personally conducting so nefarious a piece of business. Bishop Patrick says "The Schechinah, I suppose, appeared to him—appeared with a drawn sword, perhaps, as he did to Balaam and David." Some say it was Moses's firstborn the Lord sought to kill. Some say it was at the child's feet the foreskin was cast, others at those of Moses, but the Targums of Jonathan and Jerusalem more properly represent that it was at the feet of God, in order to pacify him.

The story certainly presents some difficulties. Moses had just had one of his numerous interviews with Jehovah, who had told him to go back to Egypt, for all those are dead who sought his life. He is to tell Pharaoh that Israel is the Lord's firstborn, and that if Pharaoh will not let the Israelites go he will slay Pharaoh's firstborn. Then immediately follows this passage. Why this sudden change of conduct towards Moses, whose life Jehovah was apparently so anxious to save?

Adam Clarke says the meaning is that the son of Moses had not been circumcised, and therefore Jehovah was about to have slain the child because not in covenant with him by circumcision, and thus he intended [after his usual brutal fashion] to punish the disobedience of the father by the death of the son. Zip-porah getting acquainted with the nature of the case, and the danger to which her firstborn was exposed, took a sharp stone and cut off the foreskin of her son. By this act the displeasure of the Lord was turned aside, and Zipporah considered herself as now allied to God because of this circumcision. Old Adam tries to gloss over the attempted assassination of Moses by pretending it was only a child's life that was in danger. But we beg the reader to notice that no child is mentioned, but only a son whose age is unspecified. Dr. Clarke can hardly have read the treatise of John Frischl, De Circumcisione Zipporo, or he would surely have admitted that the person menaced with death was Moses, and not his son.

Other commentators say that Zipporah did not like the snipping business (although she seems to have understood it at once), and therefore addressed her husband opprobriously. Circumcision, we may remark, was anciently performed with stone. The Septuagint version records how the flints with which Joshua circumcised the people at Gilgal were buried in his grave.

A nice specimen of the modern Christian method of semi-rationalising may be found in Dr. Smith's Bible Dictionary, to which the clergy usually turn for help in regard to any difficulties in connection with the sacred fetish they call the word of God. Smith says:

"The most probable explanation seems to be, that at the caravanserai either Moses or Gershom was struck with what seemed to be a mortal illness. In some way, not apparent to us, this illness was connected by Zipporah with the fact that her son had not been circumcised. She instantly performed the rite, and threw the sharp instrument, stained with the fresh blood, at the feet of her husband, exclaiming in the agony of a mother's anxiety for the life of her child, 'A bloody husband thou art, to cause the death of my son.' Then when the recovery from the illness took place (whether of Moses or Gershom), she exclaims again, 'A bloody husband still thou art, but not so as to cause the child's death, but only to bring about his circumcision.'"

We have no hesitation in saying that this most approved explanation is the worst. In seeking to make the story rational, it utterly ignores the primitive ideas and customs by which alone this ancient fragment can be interpreted. One little fact is sufficient to refute it. The Jews never use the word Khathan, improperly translated "husband," after marriage. The word may be interpreted spouse, betrothed or bridegroom, but not husband. The Revised Version, which always follows as closely as possible the Authorised Version, translates "a bridegroom of blood." But this makes it evident that Moses was not addressed, for no woman having a son calls her husband "bridegroom." We may now see the true meaning of the incident—that by the blood covenant of circumcision, Zipporah entered into kinship with Jehovah and thereby claimed his friendship instead of enmity. In ancient times only the good-will of those who recognise the family bond or ties of blood could be relied on. Herbert Spencer, in his Ceremonial Institutions, contends that bloody sacrifices arise "from the practice of establishing a sacred bond between living persons by partaking of each other's blood: the derived conception, being that those who give some of their blood to the ghost of a man just dead and lingering near, effect with it a union which on the one side implies submission, and on the other side friendliness."

Dr. T. K. Oheyne, in his article on Circumcision in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, takes the story of Moses at the inn as a proof that circumcision was of Arabic origin. He says; "Khathan meant originally not 'husband,' but 'a newly admitted member of the family.' So that 'a khathan of blood' meant one who has become a khathan, not by marriage, but by circumcision," a meaning confirmed by the derived sense of the Arabic khatana, "to circumcise"—circumcision being performed in Arabia at the age of puberty.

The English of the Catholic Douay version is not so good as the Authorised Version, but it brings us nearer the real meaning of the story. It runs thus:

"And when he was in his journey, in the inn, the Lord met him and would have killed him. Immediately Sephora took a very sharp stone, and circumcised the foreskin of her son, and touched his feet, and said: A bloody spouse art thou to me. And he let him go after she had said: A bloody spouse art thou unto me, because of the circumcision."

Here it is evidently the feet of the Lord that are touched, as was the ancient practice in rendering tribute, and we see that the foreskin was a propitiatory offering.

Dr. Trumbull in his interesting book on the Blood Covenant, says: "The Hebrew word Khathan has as its root idea, the binding through severing, the covenanting by blood; an idea that is in the marriage-rite, as the Orientals view it, and that is in the rite of circumcision also." Dr. Trumbull omits to say that the term is not used after marriage, and consequently that it must be taken as applied to the Lord. Zipporah, being already married, did not need to enter into the blood covenant with Moses, but with Jehovah, so that to her and hers the Lord might henceforth be friendly.

We do not make much of the inn. There were no public-houses between Midian and Egypt. Probably the reference is only to a resting-place or caravanserai. We would, therefore, render the passage thus:

The Lord met him [Moses] at a halting place and sought to kill him. Then Zipporah took a flint, and cut off the foreskin of her son and cast it at [made it touch] his [the Lord's] feet, and she said: Surely a kinsman of blood [one newly bound through blood] art thou to me. So he [the Lord] let him [Moses] alone.

Kuenen considers the passage, in connection with the place where it is inserted, indicated that circumcision was a substitute for child sacrifice. Any way, it may safely be said that the mark which every Jew bears on his own body is a sign that his ancestry worshipped a deity who sought to assassinate Moses, and was only to be appeased by an offering of blood.

Hahnemann, the founder of homoeopathy, is usually credited with the introduction of the medical maxim, similta similibus ourantur—like things are cured by like. Those who would dispute his originality need not refer to the ancient saying familiar to all topers, of "taking a hair of the dog that bit you"; they may find the origin of the homoeopathic doctrine in the great source of all inspiration—the holy Bible.

The book of Numbers contains several recipes which would be invaluable if divine grace would enable us to re-discover and correctly employ them. There is, for instance, the holy water described in chap. v., the effects of which will enable any jealous husband to discover if his wife has been faithful to him or not, and in the case of her guilt enable him to dispense with the services of Sir James Hannen.

But perhaps the most curious prescription in the book is that recorded in the twenty-first chapter. The Israelites wandering about for forty years, without travelling forty miles, got tired of the heavenly manna with which the "universal provider" supplied them. They looked back on the fried fish, which they "did eat in Egypt freely," the cucumbers, melons, leeks, onions and garlic, wherein the Jewish stomach delighteth, and they longed for a change of diet. Upon remonstrating with Moses, and stating their preference for Egyptian lentils rather than celestial mushrooms, the Lord of his tender mercy sent "fiery serpents" (the word is properly translated "seraphim"), and they bit the people; and much people of Israel died. Then the people prayed Moses to intercede for them, saying, "We have sinned, for we have spoken against the Lord and against thee;" and Jahveh, in direct opposition to his own commandment, directed Moses to "make a fiery serpent, and set it upon a pole, and it shall come to pass that every one that is bitten when he looketh upon it shall live." Moses accordingly made a serpent of brass, we presume from some of that stolen from the Egyptians, which had the desired effect. Instead of being but one monster more, the sight immediately cured the wounds, and these seraphim sent by the Lord, ashamed of being beaten by their brazen brother, skedaddled. Of course it may be contended that a seraph is neither in the likeness of anything in heaven above, in earth beneath, or in the water, or fire, under the earth, and that consequently Moses in no wise infringed the Decalogue.

Commentators have been puzzled to account for this evident relic of serpent worship in a religion so abhorrent of idolatry as that of the Jews. These gentry usually shut their eyes very close to the many evidences that the god-guided people were always falling into the idolatries of the surrounding nations. Now we know that the Babylonians, in common with all the great nations of antiquity, worshipped the serpent. It has been thought, indeed, that the name Baal is an abbreviation of Ob-el, "the serpent god." In the Apocryphal book of Bel and the Dragon, to be found in every Catholic Bible, it says (v. 23): "And in that same place there was a great dragon, which they of Babylon worshipped. And the king said unto Daniel, Wilt thou also say that this is of brass? Lo, he liveth, he eateth and drinketh, thou canst not say that he is no living god; therefore worship him." Serpent worship is indeed so widely spread, and of such great antiquity, that it has been conjectured to have sprung from the antipathy between our monkey ancestors and snakes. In this legend the brazen serpent is benevolent, but more usually that reptile represents the evil principle. Thus a story in the Zendavesta (which is clearly allied to, and may have suggested that in Genesis) says that Ahriman assumed a serpent's form in order to destroy the first of the human race, whom he accordingly poisoned. In the Saddu we read: "When you kill serpents you shall repeat the Zendavesta, whereby you will obtain great merit; for it is the same as if you had killed so many devils." It is curious that the serpent which is the evil genius of Genesis is the good genius in Numbers, and that Jesus himself is represented as comparing himself to it (John iii. 14). An early Christian sect, the Ophites, found serpent worshipping quite consistent with their Christianity.

It seems likely that this story of the brazen serpent having been made by Moses, was a priestly invention to account for its being an object of idolatry among the Jews, as we know from 2 Kings xviii. 4, it was worshipped down to the time of Hezekiah, that is 700 years after the time of Moses. Hezekiah, we are told, broke the brazen serpent in pieces, but it must have been miraculously joined again, for the identical article is still to be seen, for a consideration, in the Church of St. Ambrose at Milan. Some learned rabbis regard the brazen serpent as a talisman which Moses was enabled to prepare from his knowledge of astrology. Others say it was a form of amulet to be copied and worn as a charm against disease. Others again declare it was only set up in terrorem, as a man who has chastised his son hangs up the rod against the wall as a warning. Rationalising commentators have pretended that it was but an emblem of healing by the medical art, a sort of sign-post to a camp hospital, like the red cross flag over an ambulance. These altogether pervert the text, and miss the meaning of the passage. The resemblance of the object set up was of the essence of the cure, as may be seen in 1 Sam. vi. 5. In truth, the doctrine of like curing like, instead of being a modern discovery is a very ancient superstition. The old medical books are full of prescriptions, or rather charms, founded on this notion.* It is, indeed, one of the recognised principles in savage magic and medicine that things like each other, however superficially, affect each other in a mystic way, and possess identical properties. Thus in Melanesia, according to Mr. Codrington,** "a stone in the shape of a pig, of a bread fruit, of a yam, was a most valuable find," because it made pigs prolific, and fertilised bread, fruit trees, and yam plots.

* See Myths in Medicine and Old Time Doctors, by Alfred C.

Garratt, M.D.

** Journal Anthropological Institute, February, 1881.

In Scotland, too, "stones were called by the names of the limbs they resembled, as 'eye-stanes, head-stane.'" A patient washed the affected part of his body, and rubbed it well with the stone corresponding. In precisely the same way the mandrake* root, being thought to resemble the human body, was supposed to be of wondrous medical efficacy, and was credited with human and super-human powers.** The method of cure, when the Philistines were smitten with emerods and mice, was to make images of the same (1 Sam. vi. 5), and the same idea was found in the well-known superstition of sorcerers making "a waxen man" to represent an enemy, injuries to the waxen figure being supposed to affect the person represented.

* Gregor, Folk-lore of North-East Counties, p. 40.

** See the paper on "Moly and Mandragora," in A. Lang's

Custom and Myth; 1884.

Many curious customs and superstitions may be traced to this belief. In old medical works one may still read that to eat of a lion's heart is a specific to ensure courage, while other organs and certain bulbous plants are a remedy for sterility. The virtue of all the ancient aphrodisiacs resided in their shape. This notion, which largely affected the early history of medicine, is known as the doctrine of signatures.

Certain plants and other natural objects were believed to be so marked or stamped that they presented visibly the indications of the diseases, or diseased organs, for which they were specifics; these were their signatures. Hence a large portion of the ancient art of medicine consisted in ascertaining what plants were analogous to the symptoms of disease, or to the organ diseased. To this doctrine we owe some popular names of plants, such as eye-bright, liver-wort, spleen-wort, etc. The mandrake, from its supposed resemblance to the human form, was credited with marvellous powers, and anyone who will take the trouble to inquire into the folk-lore concerning plants and disease will find that much depends upon the appearance of the remedy.

One of the most curious peculiarities of Christianity is its doctrine of a God crucified for sinners. So strange, so repugnant to reason as such a doctrine is, it was quite consonant to the thoughts of those who held the belief in salvation by similars. If Paul said, since by man came death by man came also the resurrection of the dead, the development of the doctrine necessitated that if it is God who damns it is also God who saves. Any casual reader of Paul must have been struck by the antithesis which he constantly draws between the law and the Gospel, works and faith, the fall of man, and the redemption through "the second Adam." The very phrase "second Adam" implies this doctrine, which is summed up in the statement that "Christ hath redeemed us from the curse of the law, being made a curse for us" (Gal. iii. 13).

God, in order to redeem man, had to take on sinful flesh and be himself the curse in order to be the cure. Hence we read in the Teaching of the Twelve Apostles, chap. xvi., that "they who endure in their faith shall be saved by the very curse." Thus may we understand that which modern Christians find so difficult of explanation, viz., that the whole Christian world for the first thousand years from St. Justin to St. Anselm believed that Christ paid the ransom for sinners to the Devil, their natural owner. Christ in order to become the Savior had to become the curse, had to die and had to descend to hell, though of course, being God, he could not stay there. Hence his being likened to the brazen serpent, that remnant of early Jewish fetichism which was smashed by Hezekiah (2 Kings xviii. 4). John makes Jesus himself teach that "as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness [as a cure for serpent bites] even so must the Son of man be lifted up, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish but have eternal life."

So Irenæus says (bk. iv., chap. 2), "men can be saved in no other way from the old wound of the serpent than by believing in him, who in the likeness of sinful flesh, is lifted up from the earth on the tree of martyrdom, and draws all things to himself and vivified the dead." That is, Christ was made sinful flesh to be the curse itself, just as the innocent brass appeared a serpent, because the form of the curse was necessary to the cure. Paul dwells on the passage of the law "Cursed is he that hangeth on a tree," with the very object of showing that Christ, cursed under the law, was a blessing under his glad tidings. The Fathers were never tired of saying that man was lost by a tree (in Eden) and saved by a tree (on Calvary), that as the curse came in child-birth* and thorns, so the world was saved by the birth of Christ and his crown of thorns. Justin says, "As the curse came by a Virgin, so by a Virgin the salvation," and this antithesis between Eve and Mary has been carried on by Catholic writers down to our own day.

* Notice too 1 Tim. 15, where women are said to be saved by

child birth, their curse.

As the Christian doctrine of salvation through the blood of Christ has certainly no more foundation in fact than the efficacy of liver-wort in liver diseases, we suggest it may have no better foundation than the ancient superstition of salvation by similars.

"New Presbyter," says Milton, "is but old priest writ large." Old priest, it may be said, is but older sorcerer in disguise. In early times religion and magic were intimately associated; indeed, it may be said they were one and the same. The earliest religion being the belief in spirits, the earliest worship is an attempt to influence or propitiate them by means that can only be described as magical; the belief in spirits and in magic both being founded on dreams. Medicine men and sorcerers were the first priests. Herbert Spencer says (Principles of Sociology, sec. 589): "A satisfactory distinction between priests and medicine men is difficult to find. Both are concerned with supernatural agents, which in their original form are ghosts; and their ways of dealing with these supernatural agents are so variously mingled, that at the outset no clear classification can be made." Among the Patagonians the same men officiate in the "threefold capacity of priests, magicians and doctors"; and among the North American Indians the functions of "sorcerer, prophet, physician, exorciser, priest, and rain doctor" are united.

Everywhere we find the priests are magicians. Their authority rests on imagined and dreaded power.

They are supposed by their spells and incantations to have power over nature, or rather the spirits supposed to preside over it. Hence they became the rulers of the people. The modern priest, who is supposed by muttering a formula to change the nature of consecrated elements or by his prayers to bring blessings on the people, betrays his lineal descent from the primitive rain-makers and sorcerers of savagery.

The Bible is full of magic and sorcery. Its heroes are magicians, from Jahveh Elohim, who puts Adam into a sleep and then makes woman from his rib, to Jesus who casts out devils and cures blindness with clay and spittle, and whose followers perform similar works by the power of his name. The most esteemed persons among the Jews were magicians. Pious Jacob cheats his uncle by a species of magic with peeled rods. Joseph not only tells fortunes by interpreting dreams but has a divining cup (Gen. xliv. 5), doubtless similar to the magic bowls used to the present day in Egypt, in which, as described by Lane in his Modern Egyptians, a boy looks and pretends to see images of the future in water.

The fourth chapter of Exodus gives the initiation of Moses into the magician's art by Jahveh, the great adept, who changes the rod of Moses into a serpent and back again into a rod; suddenly makes his hand leprous, and as suddenly restores it. Moses and Aaron show themselves superior magicians to those at the court of Pharaoh, who, when Aaron cast down his magic rod and it became a serpent, did in like manner with their rods, which also became serpents, though Aaron's rod swallowed up their rods (Exodus vii. 11,12). Upon this passage the learned Methodist commentator, Dr. Adam Clarke, writing at an age when the belief in witchcraft was almost extinct, after remarking that such feats evidently required something more than jugglery, observes: "How much more rational at once to allow that these magicians had familiar spirits who could assume all shapes, change the appearance of the subjects on which they operated, or suddenly convey one thing away and substitute another in its place."

Aaron also used his rod to change all the water into blood, a feat which the Egyptian magicians also contrived to perform—we presume with the aid of spirits. If you believe in spirits, there is no end to the supposition of what they might do. The magic rod of Moses is used to divide the water of the Red Sea, so that the children went through the midst of the sea on dry ground (Ex. xiv. 16), and to draw water from a rock (Num. xx. 8). Aaron's rod blossoms miraculously to show the superiority of the tribe of Levi (Num. xvii. 8).

The Urim and Thummin of Aaron's breastplate were also magical articles used in divination (see Num. xxviii. 21; 1 Sam. xxiii. 9, and xxx. 7, 8). Casting lots was another method of divination often referred to in the Bible. Prov. xvi. 31, says "The lot is cast into the lap, but the whole disposing thereof is with the Lord." It was because "when Saul inquired of Jahveh, Jahveh answered him not, neither by dreams, nor by Urim, nor by prophets" (1 Sam. xxviii. 6), that he resorted to the witch of Endor. The ephod and holy plate (Ex. xxviii.), and the phylacteries worn as frontlets between the eyes (Deut. vi. 8), were magical amulets. Modern Arabs wear scraps of the Koran in a similar way. The holy oil (Ex. xxx.) and the water of jealousy (Num. v.) were magical, as was also the brazen serpent, adored down to the days of Hezekiah. The great Wizard's ark was also endowed with magical powers, bringing with it victory and punishing those who infringed its tabu; it was taken into battle. His sanctuary was also called an oracle where the priest "inquired of the Lord" (2 Sam. xvi. 23; 1 Kings vi. 16).

The teraphim were also magical, as we learn from Ezek. xxi. 21, where the word is translated "images." The prophet Hosea, one of the very earliest of the Old Testament writers (about 740), announced as a misfortune that "the children of Israel shall abide many days without a king, and without a prince, and without a sacrifice, and without an image, and without an ephod, and without teraphim." Laban, although a believer in Elohim, calls the teraphim "his gods" (Genesis xxxi. 29, 30), and so does Micah (Judges xviii. 18-24). The latter chapter shows that the teraphim were worshipped and served by the descendants of Moses down to the time of David (see Revised Version). David's wife Michal kept one in the house (1 Sam. xix. 13). It was evidently a fetish in human shape. How comes it, then, one may ask, that divination and sorcery are denounced in Deuteronomy xviii.? The answer is simple. The Deutoronomic law was first found in the time of Josiah, B.C. 641 (see 2 Kings xxii. 8-11), and there is abundant evidence it was not known before that time. Josiah, as we learn from 2 Kings xxiii. 24, put away "the familiar spirits, and the wizards and the teraphim and the idols," as Hezekiah (b.c. 726) had destroyed the brazen serpent. Not only had Jezebel practised witchcraft (2 Kings ix. 22), but Manasseh, the son of Hezekiah, "dealt with a familiar spirit and with wizards" (2 Chron. xxxiii. 6). These, it may be said, were wicked persons.

Yet another piece of evidence is derived from the fact that Nashon, the chief of the tribe of Judah and one of the ancestry of the blessed Savior, signifies "enchanter." Zechariah (b.c. 580) shows the great advance made from the time of Hosea by declaring that "the teraphim have spoken vanity, and the diviners have seen a lie, and have told false dreams" (x. 2).

Samuel, like other early priests, was ruler and weather doctor, Elijah was a corpse restorer and rain com-peller. Elisha not only inherited his mantle, but also raised the dead and multiplied food. His very bones proved magical. Jesus Christ was a great wonderworker or magician, casting out devils, turning water into wine, healing diseases even by the touch of his magical robe, and finally levitating from earth.

The charge brought against Jesus by the Jews was that he had stolen the sacred Word and by it wrought miracles. We read in the Gospels that Jesus "cast out spirits with his word" (Matt. viii. 16). Jesus promised that in his name his disciples should cast out devils, and Peter declared that his name healed the lame (Acts iii. 16). When the Jews asked, "By what power, or by what name have we done this" (Acts iv. 7), Peter answered, "By the name of Jesus Christ." Paul says, "God hath... given him a name which is above every name: That at the name of Jesus every knee should bow in heaven and in earth and under the earth" (Philip ii. 9, 10).

Any careful reader of the Bible must have been struck with the frequency with which "the name of the Lord" is mentioned, and the care not to profane that name. "Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain" is the second commandment, and Christians still speak of God "in a bondsman's key with bated breath and whispering humbleness," for no better reason than this old superstition. In Leviticus xxiv. 11 and 16, the word translated by us "blasphemeth" was by the Jews rendered "pronounces," so that the son of the Israelitish woman was stoned to death for pronouncing the ineffable name of J.H.V.H. The Talmud say "He who attempts to pronounce it shall have no part in the world to come." Once a year only, on the day of Atonement, was the high priest allowed to whisper the word, even as at the present day "the word" is whispered in Masonic lodges. The Hebrew Jehovah dates only from the Massoretic invention of points. When the Rabbis began to insert the vowel-points they had lost the true pronunciation of the sacred name. To the letters J. H. V. H. they put the vowels of Edonai or Adonai, lord or master, the name which in their prayers they substitute for Jahveh. Moses wanted to know the name of the god of the burning bush. He was put off with the formula I am that I am. Jahveh having lost his name has become "I was but am not." When Jacob wrestled with the god, angel, or ghost, he demanded his name. The wary angel did not comply (Gen. xxxii. 29.) So the father of Samson begs the angel to say what is his name. "And the angel of the Lord said unto him, why asketh thou thus after my name seeing it is secret" (Judges xiii. 18). All this superstition can be traced to the belief that to know the names of persons was to acquire power over them.