Mount Mayon

Mount Mayon

(See page 308)

THE SPELL OF THE

HAWAIIAN ISLANDS AND

THE PHILIPPINES

THE SPELL SERIES

Each volume with one or more colored plates and many illustrations from original drawings or special photographs. Octavo, decorative cover, gilt top, boxed.

Per volume, net $2.50; carriage paid $2.70

By Isabel Anderson

THE SPELL OF BELGIUM

THE SPELL OF JAPAN

THE SPELL OF THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS AND THE PHILIPPINES

By Caroline Atwater Mason

THE SPELL OF ITALY

THE SPELL OF SOUTHERN SHORES

THE SPELL OF FRANCE

By Archie Bell

THE SPELL OF CHINA

THE SPELL OF EGYPT

THE SPELL OF THE HOLY LAND

By Keith Clark

THE SPELL OF SPAIN

THE SPELL OF SCOTLAND

By W. D. McCrackan

THE SPELL OF TYROL

THE SPELL OF THE ITALIAN LAKES

By Edward Neville Vose

THE SPELL OF FLANDERS

By Burton E. Stevenson

THE SPELL OF HOLLAND

By Julia De W. Addison

THE SPELL OF ENGLAND

By Nathan Haskell Dole

THE SPELL OF SWITZERLAND

THE PAGE COMPANY

53 Beacon Street Boston, Mass.

Being an Account of the Historical and Political Conditions

of Our Pacific Possessions, together with Descriptions of the

natural Charm and Beauty of the Countries and the strange and

interesting Customs of their Peoples.

Author of "The Spell of Japan," "The Spell of Belgium," etc.

ILLUSTRATED

BOSTON

THE PAGE COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1916, by

The Page Company

All rights reserved

Published in November, 1916

Second Impression, June, 1917

THE COLONIAL PRESS

C. H. SIMONDS CO., BOSTON, U. S. A.

I DEDICATE THIS BOOK WITH LOVE

TO THE MEMORY OF MY GRANDFATHER

WILLIAM F. WELD

WHOSE SHIPS SAILED UPON THESE

TROPICAL SEAS

It is my hope that this book about our islands in the Pacific ocean may be of some interest, if for no other reason than that there is at present so much discussion as to whether or not we should keep the Philippines.

Soon after the close of the Civil War my father, who was a naval officer, was sent on a cruise on the Pacific and stopped for a time both at Honolulu and Manila. During this cruise he took part in the occupation and survey of Midway Island, as it is now called—our first possession in Pacific waters. Many years later, when my husband and I started on our first trip to the East, I asked my father if he would give us letters of introduction to his many friends there. He replied, "It is a long time since I visited the islands in the Pacific; if my friends have forgotten me letters would do no good, and if they remember me letters are not necessary." Needless to say, they did remember him and extended to us the most cordial hospitality.

The charm of Hawaii will linger forever in[Pg viii] our memory—those happy flower islands where the air is sweet with perfume and gay with the musical strains of the ukulele. We lived there for a time before the Islands were annexed to the United States and, on another visit, we had the privilege of accompanying the Secretary of War, Hon. J. M. Dickinson, so that we had exceptional opportunities of seeing both Hawaii and the Philippines, and of making the acquaintance of leaders among the Americans and the natives.

We found the Philippines especially fascinating on account of the great variety they provide. The old world plazas, the flowering Spanish courtyards, and the pretty women in their distinctive costume of piña are all enchanting. Nowhere else in the Far East are the mestizos—those of mixed blood—socially above the natives. The Filipinos are unique in that they are the only Asiatics who are Christians. Among the hills, near civilization, live the savages who indulge in the exciting game of head-hunting. The Moros, the Mohammedans of the southern islands, stand quite by themselves. They are very picturesque and absolutely unlike their neighbours.

Secretary Dickinson and Governor Forbes we can never thank enough for the thousand[Pg ix] and one strange sights we saw, as enchanting as the tales which Scheherezade told during those far-off Arabian Nights. I only wish I could describe them in her delightful style! Of all the spells what is more puissant than the spell of the tropics—the singing of dripping water, the rustle of the palm in the breeze. In this land you forget all trouble and dream of love and happiness, while the Southern Cross gleams brightly in the sky.

There it is indeed true that

"The flower of love has leisure for growing,

Music is heard in the evening breeze,

The mountain stream laughs loud in its flowing,

And poesy wakes by the Eastern Seas."

I wish especially to say how grateful I am to those who have helped me in one way or another, with this book: Admiral George Dewey, General Thomas Anderson, Major J. R. M. Taylor, Major William Mitchell, Mr. William R. Castle, Jr., and Mr. C. P. Hatheway. Mr. R. K. Bonine was also very kind in allowing me to reprint some of his photographs of Hawaii. My thanks are also due to Miss Helen Kimball, Miss C. Gilman, Miss K. Crosby, and my husband, and to all the others who have been so good as to encourage me in writing the "Spell of the Hawaiian Islands and the Philippines."

| Foreword | vii | |

| THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | The Bright Land | 3 |

| II | Myths and Meles | 29 |

| III | The Five Kamehamehas | 48 |

| IV | Servant and Soil | 81 |

| V | In and Out | 103 |

| THE PHILIPPINES | ||

| I | Manila as We Found It | 123 |

| II | The Philippines of the Past | 148 |

| III | Insurrection | 180 |

| IV | Following the Flag | 206 |

| V | Healing a Nation | 224 |

| VI | Dog-Eaters and Others | 245 |

| VII | Among the Head-Hunters | 270 |

| VIII | Inspecting with the Secretary of War | 296 |

| IX | The Moros | 325 |

| X | Journey's End | 353 |

| Bibliography | 363 | |

| Index | 365 | |

| PAGE | |

| Mount Mayon (in full colour) (See page 308) | Frontispiece |

| MAP OF THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS | 1 |

| Royal Hawaiian Hotel | 6 |

| Hon. Sanford B. Dole | 9 |

| Surf-boating (in full colour) | 17 |

| Making Poi (in full colour) | 27 |

| Interior of Hawaiian Grass House | 33 |

| Ancient Temple Inclosure | 37 |

| A Hula Dancer (in full colour) | 40 |

| Queen Emma | 65 |

| King Kalakaua and Staff | 73 |

| "The Tiny Plantation Railway Among the Waving Green Stalks" | 82 |

| Pineapple Plantation, Island of Oahu | 88 |

| Leper Colony, Island of Molokai | 105 |

| Silversword in Bloom, in the Crater of Haleakala | 108 |

| Fire Hole, Kilauea | 110 |

| On the Shores of Kauai, the "Garden Island" | 115 |

| MAP OF THE PHILIPPINES | 121 |

| Governor General Cameron Forbes | 125 |

| The Pasig River (in full colour) | 128 |

| Malacañan Palace | 136 |

| Mrs. Anderson in Filipina Costume | 139 |

| "Under the Bells" | 155 |

| Jose Rizal | 170 |

| Fort Santiago | 172 |

| A Group of Filipina Ladies | 182 |

| Aguinaldo's Palace at Malolos | 191 |

| San Juan Bridge | 194 |

| [Pg xiv]General Lawton | 196 |

| Benguet Road | 212 |

| First Philippine Assembly | 215 |

| Osmeña, the Speaker of the First Assembly | 217 |

| A Carabao (in full colour) | 225 |

| Penal Colony on the Island of Palawan | 239 |

| The Party at Baguio | 246 |

| Igorot School Girl Weaving | 251 |

| Igorot Outside his House | 253 |

| Ilongot in Rain-coat and Hat of Deerskin | 258 |

| Ilongots Returning from the Chase | 260 |

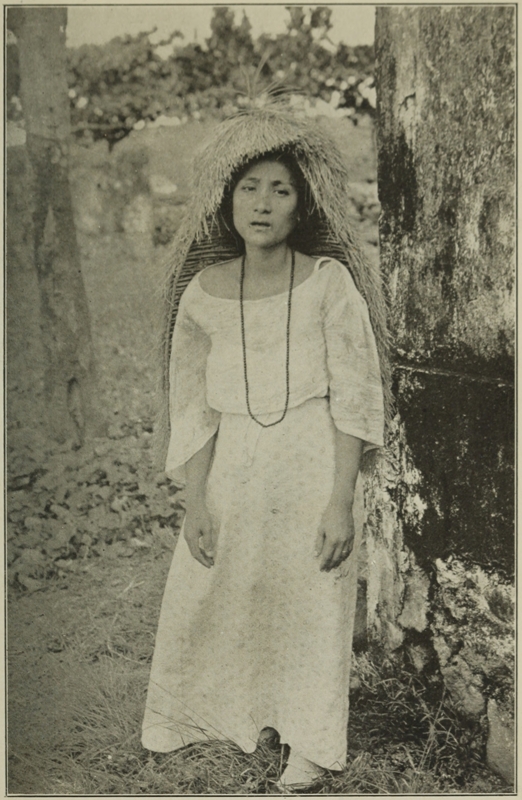

| Woman of the Batan Islands with Grass Hood | 264 |

| Constabulary Soldiers | 283 |

| Rice Terraces | 287 |

| Ifugao Couple | 289 |

| Ifugao Head Dance | 293 |

| Weapons of the Wild Tribes | 295 |

| Landing at Tobaco | 309 |

| A Moro Dato and His Wife, with a Retinue of Attendants | 325 |

| A Moro Grave | 329 |

| A Moro Dato's House | 336 |

| Bagobo Man with Pointed Teeth | 339 |

| Bagobos with Musical Instruments | 345 |

| Bagobo with Nose Flute | 348 |

| Moro Boats | 350 |

| One Day's Catch of Fish | 356 |

| View in Iloilo, Iloilo, Showing High School Grounds | 358 |

| The Old Augustinian Church, Manila | 361 |

THE SPELL OF THE

HAWAIIAN ISLANDS AND

THE PHILIPPINES

n our first trip to Hawaii we sailed from San Francisco aboard the Gaelic with good, jolly Captain Finch. He was a regular old tar, and we liked him. We little thought that in 1914 he would have the misfortune to be in command of the Arabic when it was torpedoed in the Atlantic. He showed great gallantry, standing on the bridge and going down with his ship, but I take pleasure in adding that he was saved.

We had an ideal ocean voyage: calm, blue seas, with a favouring trade wind, a glorious moon, and strange sights of huge turtles, tropic birds, and lunar rainbows. We had, too, an unusual company on board—Captain Gridley, of Manila Bay fame, then on his way to take[Pg 4] command of the Olympia; Judge Widemann, a German who had lived for many years in Honolulu, and had married a Hawaiian princess; Mr. Irwin, a distinguished American with a Japanese wife—all old friends of my father, who, as a naval officer, made several cruises in the Pacific—Dr. Furness of Philadelphia, a classmate of my husband's at Harvard, who was going out to study the head-hunters of Borneo; and Mr. Castle, grandson of one of the early missionaries to Hawaii. He has since written a charming book on the Islands.

After six days on the smooth Pacific, we caught sight of Oahu, the fairy island on which Honolulu is situated. Diamond Head stretches far out into the blue, like a huge lizard guarding its treasure—a land of fruits and flowers, of sugar-cane and palm. The first view across the bay of the town with its wreath of foliage down by the shore, just as the golden sun was setting over the mountain range, was a picture to be remembered. And in the distance, above Honolulu, the extinct crater called Punchbowl could be seen, out of which the gods of old no doubt drank and made merry.

An ancient Hawaiian myth of the creation tells how Wakea, "the beginning," married[Pg 5] Papa, "the earth," and they lived in darkness until Papa produced a gourd calabash. Wakea threw its cover into the air, and it became heaven. The pulp and seeds formed the sky, the sun, moon and stars. The juice was the rain, and out of the bowl the land and sea were created. This country they lived in and called it Hawaii, "the Bright Land." There are many legends told of Papa by the islanders of the Pacific. She traveled far, and had many husbands and children, among whom were "the father of winds and storms," and "the father of forests."

As we approached the dock, we forgot to watch the frolicking porpoises and the silver flying fish, at sight of the daring natives on their boards riding the surf that broke over the coral reef. The only familiar face we saw on the wharf as we landed was Mr. George Carter, a friend of my husband's, who has since been Governor of the Islands.

Oahu is a beautiful island, and the town of Honolulu at once casts its spell upon you, with the luxuriance of its tropical gardens. There is the spreading Poinciana regia, a tree gorgeous with flowers of flame colour, and the "pride of India," with delicate mauve blossoms; there are trees with streaming yellow clusters, called[Pg 6] "golden showers," and superb date and cocoanut and royal palms, and various kinds of acacia. Bougainvilleas, passion-flowers, alamanders and bignonias drape verandas and cover walls. There are hedges of hibiscus and night-blooming cereus, and masses of flowering shrubs. Everywhere there is perfume, colour and profusion, the greatest wealth of vegetation, all kept in the most perfect freshness by constant little passing showers—"marvelous rain, that powders one without wetting him!" Honolulu is well named, the word meaning "abundance of peace," for we found the gardens of the town filled with cooing doves. It is said the place was called after a chief by that name in the time of Kakuhihewa, the only great king of Oahu who is mentioned before Kamehameha I.

ROYAL HAWAIIAN HOTEL.

ROYAL HAWAIIAN HOTEL.

At the time of this visit, in 1897, the total isolation of the Islands was impressive, absolutely cut off, as they were, except for steamers. Sometimes, moreover, Hawaii was three weeks without an arrival, so that the coming of a steamer was a real event. To cable home, one had to send the message by a ship to Japan and so on around the world.

After a night at the old Royal Hawaiian Hotel, big and rambling, in the center of a pretty garden, we started housekeeping for ourselves [Pg 7] in a little bungalow on the hotel grounds, with a Chinaman for maid of all work. Here we lived as if in a dream, reveling in the beauty of land and sea, of trees and flowers, enjoying the hospitality for which the Islands are famous, and exploring as far as we could some of the enchanting spots of this heaven on earth.

We were pleased with our little house, with its wide veranda, or lanai, as it is called there, which we made comfortable and pretty with long wicker chairs and Chinese lanterns. Mangoes falling with a thump to the ground outside, and lizards and all sorts of harmless creatures crawling or flying about the house, helped to carry out the tropical effect.

In the four visits that we have made on different occasions we have found the climate perfect; the temperature averages about 73 degrees. The trade winds blowing from the northeast across the Pacific are refreshing as well as the tiny showers, which follow you up and down the streets. There is not a poisonous vine or a snake, or any other creature more harmful than the bee; but I must confess that the first night at the old hotel, the apparently black washstand turned white on my approach as the water bugs scuttled away. Nothing really troubled us but the mosquitoes, which, by the way, did not exist[Pg 8] there in the early days, so must have been taken in on ships.

The Islands have been well called "the Paradise of the Pacific" and "the playground of the world." The five largest in the group, and the only important ones, are Hawaii, about the size of Connecticut, Maui, Oahu, Kauai and Molokai. The small ones are not worth mentioning, as they have only cattle and sheep and a few herdsmen upon them. They are formed of lava—the product of numberless volcanic eruptions—and the action of the sea and the rain, combined with the warm climate and the moisture brought by the trade winds, has resulted in the most varied and fascinating scenery. Mark Twain, who spent many months there, said of them, "They are the loveliest group of islands that ever anchored in an ocean," and indeed we were of his opinion.

At that time the Islands formed an independent republic, under Sanford B. Dole as President, the son of Rev. Daniel Dole, one of the early missionaries. He was educated at Punahou, meaning new spring, now called Oahu College, and at Williams College in the States. He came to Boston to study law, and was admitted to the bar. But Hawaii called him, as if with a forecast of the need she would have of his services [Pg 9] in later days, and he went back to Oahu, where he took high rank among the lawyers in the land of his birth, and became judge of the Supreme Court. After the direct line of Kamehameha sovereigns became extinct, and the easy-going rule of their successors culminated in the high-handed attempt of Queen Liliuokalani to restore the ancient rites and also to turn the island into a Monte Carlo, Judge Dole was the one man who understood both parties and had the confidence of both, and he was the unanimous choice of the best element of the population for president.

HON. SANFORD B. DOLE.

HON. SANFORD B. DOLE.

Of course we visited the buildings and localities in Honolulu that were of interest because of their connection with the existing government or their history in the past. The Executive Building—the old palace, built by King Kalakaua and finished in the finest native woods—and the Court House, which was the Government Building in the days of the kings; the big Kawaiahao Church, built of coral blocks in 1842, and the Queen's Hospital, all are in the city, but they have often been described, so I pass them by with only this mention. The first frame house ever erected in the Islands deserves a word, as it was sent out from Boston for the missionaries. It had two stories, and in the early days its tiny[Pg 10] rooms were made to shelter four mission families and twenty-two native children, who were their pupils.

Oahu College, too, interested us. It was built on the land given by Chief Boki to Hiram Bingham, one of the earliest missionaries, who donated it to his coworkers as a site for a school for missionary children. The buildings stand in a beautiful park of ninety acres, in which are superb royal palms and the finest algaroba trees in Honolulu. Long ago, in the days of the rush for gold to California, boys were sent there for an education from the Pacific Coast.

The great aquarium at Waikiki, the bathing suburb of Honolulu, I found particularly fascinating. There does not exist in the world an aquarium with fishes more peculiar in form or colouring than those at Waikiki, unless the new one in the Philippines now surpasses it. About five hundred varieties of fish are to be found in the vicinity of the Islands. The fish are of many curious shapes and all the colours of the rainbow. Some have long, swordlike noses, and others have fins on their backs that look like feathers. One called the "bridal veil" has a lovely filmy appendage trailing through the water. The unusual shapes of the bodies, the extraordinary eyes and the fine colouring give[Pg 11] many of them a lively and comical appearance. Even the octopus, the many-armed sea creature, seemed wide awake and gazed at the onlookers through his glass window.

An afternoon was spent in the Bishop Museum, which is very fine and well equipped, its collection covering all the Pacific islands. I was chiefly interested in the Hawaiian curios,—the finely woven mats of grass work and the implements of the old days. Here, too, was the famous royal cloak of orange, made of feathers from the mamo bird.[1] It was a work of prodigious labour, covering a hundred years. This robe is one of the most gorgeous things I have ever seen and is valued at a million dollars. There were others of lemon yellow and of reds, besides the plumed insignia of office, called kahili, which were carried before the king. Our guide through the museum was the curator, Professor Brigham, who had made it the greatest institution of its kind in the world.

This museum is a memorial, created by her husband, to Bernice Pauahi Bishop, great-granddaughter of Kamehameha I and the last descendant of his line. Bernice Pauahi was the[Pg 12] daughter of the high chief Paki and the high chieftainess Konia. She was born in 1831, and was adopted in native fashion by Kinau, sister of Kamehameha III, who at that time had no daughters of her own. Her foster sister, Queen Liliuokalani, said of her, "She was one of the most beautiful girls I ever saw."

At nineteen she married an American, Hon. Charles R. Bishop, who was collector of customs in Honolulu at that time. She led a busy life, and used her ability and her wealth to help others. She understood not only her own race but also foreigners, and she used her influence in bringing about a good understanding between them.

In 1883, the year before her death, she bequeathed her fortune to found the Kamehameha School for Hawaiian boys and girls. This school has now a fine group of stone buildings not far from Honolulu.

The Lunalilo Home was founded by the king of that name for aged Hawaiians. When we visited it, we were particularly interested in one old native who was familiar with the use of the old-time musical instruments. This man, named Keanonako, was still alive two years ago. He was taught by his grandfather, who was retained by one of the old chiefs. He played on[Pg 13] three primitive instruments—a conch shell, a jew's-harp and a nose flute. The last is made of bamboo, and is open at one end with three perforations; the thumb of the left hand is placed against the left nostril, closing it. The flute is held like a clarinet, and the fingers are used to operate it. Keanonako played the different notes of the birds of the forest, and really gave us a lovely imitation. The musical instruments in use to-day are the guitar, the mandolin, and the ukulele. The native Hawaiians are very musical and sing and play well, but the music is now greatly mixed with American and European airs.

It was always entertaining to drive in the park, where we listened to the band and watched the women on horseback. In those days the native women rode astride wonderfully well and looked very dignified and stately, but one does not see this superb horsemanship and the old costumes any more. They did indeed make a fine appearance, with the paus, long flowing scarfs of gay colours, which some of them wore floating over their knees and almost reaching the ground, while their horses curvetted and pranced.

One of the amusements was to go down to the dock to see a steamer off and watch the pretty[Pg 14] custom of decorating those who went away with leis—wreaths of flowers—which were placed around the neck till the travelers looked like moving bouquets and the whole ship at last became a garden. When large steamers sailed the whole town went to the wharf, and the famous Royal Hawaiian Band—which Captain Berger, a German, led for forty years—played native airs for an hour before the time of sailing. It was an animated and pretty sight at the dock, for the natives are so fond of flowers that they, too, wear leis continually as bands around their hats, and they bring and send them as presents and in compliment. Steamers arriving at the port were welcomed in the same charming fashion.

Judge Widemann kindly asked us to dine and view his wonderful hedge of night-blooming cereus. The good old Judge who had married the Princess had three daughters; two of the girls were married to two brothers, who were Americans. All the daughters were attractive, and the youngest, who was the wife of a German, was remarkably pretty. It was strange at first to see brown-skinned people in low-necked white satin dinner gowns, and to find them so cultured and charming.

We dined with Mr. and Mrs. Castle, also with[Pg 15] old Mrs. Macfarlane at Waikiki. We enjoyed our evening there immensely. Sam Parker, "the prince of the natives," and Paul Neumann, and Mrs. Wilder, too, all great characters in those days, were very kind to us. Many of them have passed away, but I shall always remember them as we knew them in those happy honeymoon months.

All the mystic spell of those tropical evenings at Waikiki lives in these lines by Rupert Brooke:

"Warm perfumes like a breath from vine and tree

Drift down the darkness. Plangent, hidden from eyes,

Somewhere an eukaleli thrills and cries

And stabs with pain the night's brown savagery.

And dark scents whisper; and dim waves creep to me,

Gleam like a woman's hair, stretch out, and rise;

And new stars burn into the ancient skies,

Over the murmurous soft Hawaiian sea."

I took great pleasure in going to Governor Cleghorn's place. He is a Scotchman who married a sister of the last king, and was at one time governor of this island. Many years ago, my father brought home a photograph of their beautiful daughter, then a girl of fourteen, who died not long after. Mr. Cleghorn's grounds were superb—old avenues of palms and flowering shrubs, and shady walks with Japanese bridges, and pools of water filled with lilies. A[Pg 16] fine view of the valley opened out near the house. There were really two connected houses, which were large and built of wood, with verandas. One huge room was filled with portraits of the Hawaiian royal family and some prints of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. There were knickknacks everywhere, and teak-wood tables and chairs, poi bowls made by hand, and primitive stone tools. We were served with lemonade by two Japanese servants in the pretty costume of their land, while tea was served by a picturesque Chinese woman at a table on the veranda.

Besides these informal entertainments, there were various official functions. One was a delightful musicale at President Dole's house, in the midst of his lovely tropical garden; also a dinner at the Consul General's, besides several parties on the naval vessels at the station. Captain Book gave us a dinner and dance on his ship, the Marian. We had breakfast one day on the flagship Philadelphia with Admiral and Mrs. Beardsley—the Admiral was in command of the station. Captain Cotton of the Philadelphia also gave us a boating party by moonlight, followed by a little dance aboard ship.

After lunching with the American Minister, Mr. Sewall, one day, we sat on his lanai [Pg 17] at Waikiki and watched the surf-boating, which was most exciting, even from a distance, as the canoes came in at racehorse speed on the crest of the breakers. That day L. and I put our bathing suits on, as we did indeed several times, got into an outrigger canoe with two native boys to handle it, and started for the reef. They skilfully paddled the boat out between the broken waves, waiting for the chance to move on without meeting a foaming crester, and then hurrying to catch a smooth place. At last we got out far enough and turned, watching over our shoulders for a big fellow to come rolling in. Then the boys paddled wildly and allowed the crest, as it broke, to catch and lift the boat and rush it along on top of the roaring foam, right up to the beach. On one of our trips our oarsmen were a little careless and we were upset. But instead of swimming in shore we swam out to sea and pushed the boat until we were well beyond the breakers, where we could right it again and get in—which, for those not used to it, is not a particularly easy thing to accomplish. The people on the shore became frightened about us and sent out another boat to pick us up, for we were quite far out and there were many sharks around.

By the way, one hears it questioned even to-[Pg 18]day whether sharks really do eat men, notwithstanding two men were bitten lately while bathing as far north as on the New Jersey coast. I will simply say I have seen a black diving boy at Aden with only one leg, as the other was bitten off by a shark, and have myself even worn black stockings when bathing in tropical seas because it is said sharks prefer white legs to black.

An old friend of mine, an admiral in the navy, tells this extraordinary story—that a sailor was lost overboard from his ship, and that inside a shark caught the very same day was found the sailor's head. Here is another story even more remarkable than that, taken from Musick's book on Hawaii:

"Why, sharks are the most tractable creatures in the world when you know how to handle them. It takes a great deal of experience and skill to handle a good-sized shark, one of the man-eating species, but the Kanaka boys know exactly how to master them. I used to have a fish pond over on the other side of Oahu, and at high tide sometimes as many as half a dozen full-grown sharks would come in the pond at a time, and when it was low tide it left them in the pond, which would be so shallow the sharks could not turn over. The native boys used to[Pg 19] go to that pond, jump astride the sharks and ride them through the water. It was great amusement to see them riding races around the pond on the backs of the sharks.

"Now, if you don't believe this story, if you will charter the ship I will take the whole party to the very pond in which the sharks are ridden for horses. If I can't show you the pond, I will pay the expense of the ship."

A long drive up into the mountains back of the town one morning, took us to Mt. Tantalus, two thousand or more feet high, from which there are splendid views of the plain below and the sea beyond and mountain ranges on each side. To-day there are many pretty summer villas built on its slopes. While we were looking down on the town and harbour far below us, we saw little puffs of white smoke, and long after could just hear the booming of the guns of the warships, American, English, and Japanese, saluting in honour of the President of this little island republic, who was visiting one of the vessels. Then we climbed higher yet, through woods of koa trees, bordered by thickets of the lantana, with its many-coloured flowers, up till we could look down into the dead crater of Punchbowl and over Diamond Head, and far off across the[Pg 20] sparkling ocean, while the steeply ravined and ribbed mountains seemed to fall away suddenly beneath our feet.

Punchbowl, where in the early days the natives offered human sacrifices, "is for the most part as red as clay, though a tinge of green in its rain-moistened chinks suggests those bronzes of uncertain antiquity." On this mountain top a myth tells us how a human being was first made—a man to rule over this island. The gods molded him from the clay of the crater, and as they were successful and he came to life, they made from his shadow a woman to keep him company. Indeed, many of the natives still believe in gods and fairies, in shark men, owls, and ghosts, and they will tell you stories of the goddess of the crater even to-day.

When we last visited this island thirteen years later with our Secretary of War, Mr. Dickinson, we saw many changes. We were taken to the Alexander Young Hotel in the center of the town, and to the great hotel at Waikiki. The old hotel, where we stayed years before, had changed hands and was sadly run down. How pretty and green everything was, and how marvelous were the flowers! Many new and rare species had been planted.[Pg 21]

The changes have been gradual, but to-day Honolulu is a modern, up-to-date American town, with business blocks of brick. The Makapuu Point Light is one of the largest in the world, and Diamond Head crater has been made into one of the strongest fortifications of modern times. Great men-of-war are to be seen off Honolulu, and Pearl Harbour has been dredged. The army quarters on this island are quite fine. There are good golf links, and on the polo field you see excellent players; the field is also used for aviation. The finely equipped Children's Hospital, the Normal School, and the McKinley High School were interesting institutions that had sprung up since our first visit.

To-day, out of a total population in all the Islands of 209,830, Honolulu has over 50,000. Many new houses and beautiful gardens are to be seen. The island now has, of course, cable and wireless communication with the mainland, electric cars and lights, telephones, the telegraph and numberless motors—in fact, every luxury is to be found. There are a number of clubs, of which the University is especially popular, and the Pacific, or British, Club is the oldest. The graduates of women's colleges have formed a club of their own. Schools and charitable institutions and missionary societies are[Pg 22] numerous, and the Y. M. C. A. building is very prominent.

The city now has many churches, which are well attended. The Episcopal cathedral, of stone brought from England, is especially fine. The Catholic cathedral and convent have long been established. It was a Catholic priest who first brought the algaroba tree from Central America sixty years ago and planted it in the city of Honolulu. The descendants of that one tree have reclaimed great sandy wastes and clothed them with fodder for cattle.

Our motor trip to Pearl Harbour took us past Mr. S. M. Damon's charming new place with its delightful Japanese garden. We motored to the Pali, a precipice that drops one thousand feet to the plains which stretch to the sea, where in the old days we had gone so often. Now, a stone tablet on its summit bears the following inscription:

"Erected by the Daughters of Hawaii in 1907 to commemorate the battle of Nuuanu, fought in this valley in 1795, when the invading Kamehameha I drove the forces of Kalanikupule, king of Oahu, to the Pali and hurled them over the precipice, thus establishing the Kamehameha dynasty."

In these days of aeroplanes, I gather this myth[Pg 23] of the Bird-man of the Pali from "Legends of old Honolulu," by Westervelt:

Namaka was a noted man of Kauai, but he left that island to find some one whom he would like to call his lord. He excelled in spear-throwing, boxing, leaping and flying. He went first to Oahu, and in Nuuanu Valley he met Pakuanui, a very skilful boxer, and they prepared for a contest at the Pali. Pakuanui could not handle Namaka, who was a "whirlwind around a man," so he became angry and planned to kill him. Namaka was as "slimy as a fish." "The hill of the forehead he struck. The hill of the nose he caught." Like a rainbow bending over the hau-trees he was, as he circled around Pakuanui. At a narrow place Pakuanui gave him a kick that knocked him over the precipice, expecting him to be dashed to pieces. "But Namaka flew away from the edge.... The people who were watching said, ... He flew off from the Pali like an Io bird, leaping into the air ... spreading out his arms like wings!"

This panorama is one of the wonders of the world; land and sea, coral reef and mountains, green meadow and shining sand, spread out before one's eyes at the Pali. As the road makes a sharp turn and begins to descend toward the valley, we encounter the full force of the trade[Pg 24] winds, for through this pass a gale is always blowing. To quote from Charles W. Stoddard, "If you open your mouth too wide, you can't shut it again without getting under the lee of something—the wind blows so hard."

From the Pali we went on to Pearl Harbour, where the United States Government is constructing a great naval station. This harbour, the finest in the Islands, is a deep lagoon, entered from the ocean by a narrow channel three miles in length. At the inner end it expands and divides into two "lochs," which are from thirty to sixty feet deep and with a shore line of some thirty miles. Algaroba forests cover the shores, and the fertile countryside, in which are rice, sugar and banana plantations, promises abundant supplies for the troops stationed here.

Pearl Harbour has really been in our possession ever since the Reciprocity Treaty with Hawaii was signed in Harrison's administration.[2] As it covers ten square miles, the whole navy of this country could find anchorage there, and[Pg 25] be in perfect safety. Not only has the bar that obstructed the entrance to the channel been removed, the long, narrow channel straightened, and a huge drydock constructed in which our largest ships of war could be repaired, but barracks, repair shops, a power house, hospitals, a powder magazine, and all the other buildings needed to make a complete station have been erected at a cost of more than ten millions of dollars. Before the drydock was finished it was partially destroyed by an upheaval. The natives' explanation was that the dock was built over the home of the Shark-god, and that he resented this invasion of his domain.

The island of Oahu will soon be a second Gibraltar, we hope. The channel from the sea is guarded by Fort Kamehameha. Fort Ruger is at the foot of Diamond Head, Fort DeRussy near Waikiki Beach; at Moanalua is Fort Shafter, and at the entrance of Honolulu Harbour, Fort Armstrong. There are more than eleven thousand troops stationed there to-day, consisting of field artillery, cavalry, infantry, engineers, signal corps, telephone and telegraph corps, and it is said there will soon be fifteen thousand or more.[3]

A Hawaiian feast, such as they had in the old days, was given in honour of the Secretary of War, so we were taken to the house of a member of the royal family. I was surprised to see how fine these residences were. This man was only part native, and really one would not have suspected from his appearance that he had any Hawaiian blood at all. His wife was a fat native in a holoku—a mother hubbard—who directed the feast, but did not receive.

The bedroom in which we took off our wraps opened out of the big ball room. There was a bright-coloured quilt on the bed, and on the walls were many photographs and cheap prints. Here were also royal feather plumes in vases and more polished poi bowls.

The inclosure where we feasted—or had the luau or "bake"—which led out of the ball room, was half open with a cover of canvas and banana leaves. It contained a long table covered with flowers and fruit, bowls and small dishes. There were no forks nor spoons, nor anything but one's fingers to eat with. At the end of the meal a wooden dish was passed for us to wash our fingers. Some of the dishes contained raw fish with a sauce. A cocoanut shell held rock [Pg 27] salt, the kind that is given to cattle, and a small bowl was filled with a mixture of sweet potato and cocoanut. That was the best dish of all. The roasted sweet potato was good, too, and pork, sewed up in ti leaves and roasted with hot stones, was another delicacy. The drink was made of fruits and was very sweet. And, of course, we had poi.

Poi is described as "one-finger" or "two-finger" poi—thick or thin. Native Hawaiians like it a few days old, when it is sour. Fortunately, as this was only one day old, I was able to put one finger-full of the pasty stuff in my mouth, and, on a dare, I ventured another. Poi is made from the taro root, which is boiled till soft, then pounded and mixed with water. Why I was not ill after this feast I don't know, as I tried mangoes, grapes, watermelon, and pineapple, as well as all the other things. Leis of pink carnations were put about our necks. Hawaiian music with singing went on during the meal, and afterward we danced.

The company was certainly cosmopolitan. One of the people who interested me most was a Hawaiian princess, really very pretty, dressed in the height of fashion. Her father was English. Another interesting person was the daughter of a full-blooded Chinaman, her[Pg 28] mother being half Hawaiian. Her husband was an American. She told me with great pride that her boys were both very blond. A wild Texan army man also roused my interest, from the point of view of character study; and I must not forget an Englishwoman, who said, on departure, "Us is going now." We found it all very diverting and the people so kind and hospitable that we enjoyed every minute of our stay.

ative Hawaiians—big, generous, happy, good-looking folk, athletic and fond of music—are in physical characteristics, in temperament, in language, traditions and customs, so closely related to the Samoans, the Maoris of New Zealand, and the other inhabitants of Polynesia, that it is clear they belong to the same race. Although Hawaii is two thousand miles from any other land, the people are so much like the natives of the South Sea Islands that I do not see how the relationship can be questioned. Distance, too, means little, for we hear that only lately a Japanese junk was caught in a storm and the mast destroyed, yet it was swept along by the Japan current and in an exceedingly short time was washed up on the shore near Vancouver, with most of the sailors still alive. The adventurous boatmen who first landed on the island of Hawaii, however, must not only have crossed two thousand miles of ocean in their canoes but crossed it in the face of opposing trade winds and ocean currents.[Pg 30]

The Polynesians of those early days, like the ancient Chaldeans, studied the heavenly bodies, and so, on their long voyages, were able to guide their course by the stars. Their vessels, which were double canoes, like those of the modern Samoans, were from fifty to one hundred feet long and carried a large company of people, with provisions, animals, idols, and everything that was needed for a long voyage or for colonizing a strange island.

The legends of that earliest time tell of Hawaii-loa, who sailed from the west to the Islands, which he named for himself. The coming of Wakea and Papa also belonged to that period. While they are mentioned as the creators of the earth, they are said in another version of the story to have come from Savaii in Samoa. They brought with them the tabu, which is common to all Polynesia.

Little is to be learned, however, of the history of Hawaii from the folklore of Pacific Islanders until about the year 1000 A. D. If we may believe their traditions, this was a time of great restlessness throughout all Polynesia, when Hawaii was again visited and held communication with other islands, peopled by the same race. It is interesting to remember that this was the century when the Norsemen were strik[Pg 31]ing out across the Atlantic, showing that there were daring navigators on both sides of the globe.

Paao, one of the heroes from Samoa, who settled in Hawaii, became high priest. He introduced the worship of new gods and increased the number of tabus. The great temple built by him was the first in the shape of a quadrangle—previously they had been three-sided. Afterward, he went back to Samoa and returned with Pili, whom he made ruler, and from whom the Kamehamehas were descended.

From the Hawaiian meles, or songs, we may picture their life. The men were skilful fishermen, using hooks of shell, bone, or tortoise shell, nets of olona-fiber or long spears of hard wood. The bait used in shark fishing was human flesh. When it was thrown into the water and the shark was attracted to it, the fishermen sprang overboard and fought the fish with knives of stone and sharp shark's teeth. No doubt it was an extremely exciting sport.

Along the shores of the Islands are the walls of many fish-ponds, some of which, though very old, are still in use and bid fair to last for centuries longer. Usually they were made by building a wall of lava rock across the entrance to a small bay, and the fish were kept in the in[Pg 32]closure. The wall was built loosely enough to allow the water to percolate through it, and sluice gates were added, which could be opened and closed. They were at first owned by kings and chiefs, and were probably built by the forced labour of the people. Tradition has it that the wall of Wekolo Pond at Pearl Harbour was built by natives who formed a line from shore to mountain and passed lava rock from hand to hand until it reached the shores over a mile away, without once touching the ground. Some of the ponds in the interior of the Islands have been turned into rice fields and taro patches, especially on Oahu.

The sports and games of the Hawaiians, of which there were many, were nearly all associated with gambling. Indeed, it was the betting that furnished most of the excitement connected with them. At the end of a day of games, many of the people would have staked and lost everything they owned in the world.

Boxing, surf-riding and hurling the ulu—a circular stone disk, three or four inches in diameter—were some of the favourite amusements, as well as tobogganing, which is interesting as a tropical adaptation of something that we consider a Northern sport. The slide was laid out on a steep hillside, that was made slippery [Pg 33] with dry pili grass. The sled, of two long, narrow strips of wood joined together by wicker work, was on runners from twelve to fourteen feet long, and was more like our sleds than modern toboggans. The native held the sled by the middle with both hands, and ran to get a start. Then, throwing himself face downward, he flew down the hill out upon the plain beyond, sometimes to a distance of half a mile or more.

INTERIOR OF HAWAIIAN GRASS HOUSE.

INTERIOR OF HAWAIIAN GRASS HOUSE.

The old Hawaiians were not bad farmers, indeed, I think we may call them very good farmers, when we consider that they had no metal tools of any description and most of their agricultural work was done with the o-o, which was only a stick of hard wood, either pointed at one end or shaped like a rude spade. With such primitive implements they terraced their fields, irrigated the soil, and raised crops of taro, bananas, yams, sweet potatoes, and sugar-cane.

Most of the houses of primitive Hawaiians were small, but the grass houses of the chiefs were sometimes seventy feet long. They were all simply a framework of poles thatched with leaves or the long grass of the Islands. Inside, the few rude belongings—mats, calabashes, gourds, and baskets for fish—were all in strange contrast to the modern luxury which many of[Pg 34] their descendants enjoy to-day. The cooking was done entirely by the men, in underground ovens. Stones were heated in these; the food, wrapped in ti leaves, was laid on the stones and covered with a layer of grass and dirt; then water was poured in through a small opening to steam the food.

The mild climate of Hawaii makes very little clothing necessary for warmth, and before the advent of the missionaries the women wore only a short skirt of tapa that reached just below the knees, and the men a loin-cloth, the malo. Tapa, a sort of papery cloth, is made from the bark of the paper mulberry.

Hawaiians say that in the earliest days their forefathers had only coverings made of long leaves or braided strips of grass, until two of the great gods, Kane and Kanaloa, took pity upon them and taught them to make kiheis, or shoulder capes.

Tapa making was an important part of the work of the women. It was sometimes brilliantly coloured with vegetable dyes and a pattern put on with a bamboo stamp. Unlike the patterns which our Indians wove into their baskets and blankets, each one of which had its meaning, these figures on the tapa had no special significance, so far as is known. By[Pg 35] lapping strips of bark over each other and beating them together, the tapa could be made of any desired size or thickness.

In the old legends, Hina, the mother of the demi-god Maui, figures as the chief tapa maker. The clouds are her tapas in the sky, on which she places stones to hold them down. When the winds drive the clouds before them, loud peals of thunder are the noise of the rolling stones. When Hina folds up her clouds the gleams of sunlight upon them are seen by men and called the lightning.

The sound of the tapa beating was often heard in the Islands. The story is told, that the women scattered through the different valleys devised a code of signals in the strokes and rests of the mallets by which they sent all sorts of messages to one another—a sort of primitive telegraphy that must have been a great comfort and amusement to lonely women.

In the early days, marriage and family associations fell lightly on their shoulders, and even to-day they are somewhat lax in their morals. The seamen who visited the Islands after their discovery by Captain Cook brought corruption with them, so that the condition of the natives when the first missionary arrived was indescribable. A great lack of family affection[Pg 36] perhaps naturally followed from this light esteem of marriage. The adoption and even giving away of children was the commonest thing, even among the high chiefs and kings, and exists more or less to-day.

There were three distinctly marked classes even among the ancient Hawaiians—chiefs, priests, and common people—proving that social distinctions do not entirely depend upon civilization. The chief was believed to be descended from the gods and after death was worshiped as a deity.

The priestly class also included sorcerers and doctors, all called kahuna, and were much like the medicine men among the American Indians. As with most primitive peoples—for after all, when compared they have very similar tastes and customs—diseases were supposed to be caused by evil spirits, and the kahuna was credited with the power to expel them or even to install them in a human body. The masses had implicit belief in this power, and "praying to death" was often heard of in the old days.[4]

Ancient Hawaiians wrapped their dead in tapa with fragrant herbs, such as the flowers of [Pg 37] sugar-cane, which had the property of embalming them. They were sometimes buried in their houses or in grottoes dug in the solid rock, but more frequently in natural caves, where the bodies were dried and became like mummies. Sometimes the remains were thrown into the boiling lava of a volcano, as a sacrifice to Pele.

ANCIENT TEMPLE INCLOSURE.

ANCIENT TEMPLE INCLOSURE.

It is said no Hawaiians were ever cannibals, but in the early days man-eaters from the south visited these Islands and cooked their victims in the ovens of the natives. Human bones made into the shape of fish hooks were thought to bring luck, especially those of high chiefs, so, as only part of Captain Cook's body was found and he was considered a god, perhaps his bones were used in this way.

The heiaus, or temples, developed from Paao's time into stone platforms inclosed by walls of stone. Within this inclosure were sacred houses for the king and the priests, an altar, the oracle, which was a tall tower of wicker work, in which the priest stood when giving the message of his god to the king, and the inner court—the shrine of the principal idol. One of the most important heiaus, which still exists, although in ruins, is the temple of Wahaula on the island of Hawaii.

There was much that was hard and cruel[Pg 38] about this religion. The idols were made hideous that they might strike terror to the worshipers. Human sacrifices were offered at times to the chief gods. The idols of the natives were much like those of the North American Indians, but the Kanakas are not like the Indians in character.

The oppressive tabu was part of the religion, and the penalty for breaking it was death. The word means prohibited, and the system was a set of rules, made by the chiefs and high priests, which forbade certain things. For instance, it was tabu for women to eat with men or enter the men's eating house, or to eat pork, turtles, cocoanuts, bananas and some kinds of fish. There were many tabu periods when "no canoe could be launched, no fire lighted, no tapa beaten or poi pounded, and no sound could be uttered on pain of death, when even the dogs had to be muzzled, and the fowls were shut up in calabashes for twenty-four hours at a time." Besides the religious tabus there were civil ones, which could be imposed at any time at the caprice of king or chiefs, who would often forbid the people to have certain things because they wished to keep them for themselves.

One is apt to think that in those early days the natives of these heavenly islands must have[Pg 39] been happy and free-living, without laws and doing as they wished, with plenty of fruit and fish to eat; but it was not so at all, for they were obliged to crawl in the dust before their king; they were killed if they even crossed his shadow.

As a pleasant contrast to all these grim features, the Hawaiians, like the ancient Israelites, had cities of refuge, of which there were two on the island of Hawaii. Here the murderer was safe from the avenger, the tabu-breaker was secure from the penalty of death, and in time of war, old men and women and children could dwell in peace within these walls.

The curious belief in a second soul, or double, and in ghosts, the doctrines of a future state, and the peculiar funeral rites, all of which formed part of the native religion, seem strange to many present-day Christian Hawaiians.

In all Polynesia the four great gods were Kane, "father of men and founder of the world,"[5] Kanaloa, his brother, Ku, the cruel one, and Lono, to whom the New Year games[Pg 40] were sacred. These four were also the chief deities of Hawaiians.

With some concession in costume to Western conventions

Besides the great gods there was a host of inferior deities, such as the god of the sea, the god of the fishermen, the shark god, the goddess of the tapa beaters, Laka, the goddess of song and dance, who was very popular, and Pele, the goddess of volcanoes. Still lower in the scale were the demi-gods and magicians of marvelous power, like Maui, for whom the island of Maui is said to be named, who pulled New Zealand out of the sea with his magic fish hook and stole the secret of making fire from the wise mud hens. His greatest achievement was that of lassoing the sun and forcing him to slacken his speed. He was a hero throughout Polynesia, and his hook is said to have been still preserved on the island of Tonga in the eighteenth century.

Like most primitive peoples, the Hawaiians danced in order that their gods might smile upon them and bring them luck, or to appease the dreaded Pele and the other gods of evil. The much-talked of hula began in this way as a sacred dance before the altar in a temple inclosure, while the girls, clad in skirts of grass and wreaths of flowers, chanted their songs. There was grace in some of the movements, but [Pg 41] on the whole the dances are said to have been "indescribably lascivious." After the missionaries arrived, the hula was modified, and to-day it has almost died out.

Many of the old chants were addressed to Laka, sometimes called the "goddess of the wildwood growths." These meles had neither rime nor meter and were more like chants or recitatives, as the singers used only two or three deep-throated tones. Curiously enough the verses suggest the modern vers libre. The chants include love songs, dirges and name songs—composed at the birth of a child to tell the story of his ancestors—besides prayers to the gods and historical traditions. As some of these early songs have real vigour and charm, I give a few examples.

The following is a very old chant of Kane, Creator of the Universe:

"The rows of stars of Kane,

The stars in the firmament,

The stars that have been fastened up,

Fast, fast, on the surface of the heaven of Kane,

And the wandering stars,

The tabued stars of Kane,

The moving stars of Kane;

Innumerable are the stars;

The large stars,

The little stars,

The red stars of Kane. O infinite space!

[Pg 42]The great Moon of Kane,

The great Sun of Kane

Moving, floating,

Set moving about in the great space of Kane.

The Great Earth of Kane,

The Earth squeezed dry by Kane,

The Earth that Kane set in motion.

Moving are the stars, moving is the Moon,

Moving is the great Earth of Kane."[6]

I find the meles to Laka especially pretty, such as these, taken from Emerson's "Unwritten Literature of Hawaii":

"O goddess Laka!

O wildwood bouquet, O Laka!

O Laka, queen of the voice!

O Laka, giver of gifts!

O Laka, giver of bounty!

O Laka, giver of all things!"

"This is my wish, my burning desire,

That in the season of slumber,

Thy spirit my soul may inspire,

Altar dweller,

Heaven guest,

Soul awakener,

Bird from covert calling,

Where forest champions stand,

There roamed I too with Laka."

This one from the same collection is interesting in its simplicity and strength:

"O Pele, god Pele!

Burst forth now! burst forth!

Launch a bolt from the sky!

Let thy lightnings fly!...

Fires of the goddess burn.

Now for the dance, the dance,

Bring out the dance made public;

Turn about back, turn about face;

Dance toward the sea, dance toward the land,

Toward the pit that is Pele,

Portentous consumer of rocks in Puna!"

The Hawaiian myths, I find, are not nearly so original or so full of charm as the Japanese and Chinese stories, and the long names are tiresome. They have, moreover, lost their freshness, their individuality and their primitive quality in translation and through American influence. They had been handed down entirely by word of mouth until the missionaries arrived. Many of the myths bear some resemblance to Old Testament stories as well as to the traditions told by the head-hunters of the Philippines. The legends of the volcano seem more distinctly Hawaiian.

There are many legends of Pele as well as chants in her honour, which generally represent her as wreaking her vengeance on mortals who have been so unfortunate as to offend her. I quote one that is told to account for the origin of a stream of unusually black lava, which long,[Pg 44] long ago flowed down to the coast on Maui:

"A withered old woman stopped to ask food and hospitality at the house of a dweller on this promontory, noted for his penuriousness. His kalo (taro) patches flourished, cocoanuts and bananas shaded his hut, nature was lavish of her wealth all around him. But the withered hag was sent away unfed, and as she turned her back on the man she said, 'I will return to-morrow.'

"This was Pele, goddess of the volcano, and she kept her word, and came back the next day in earthquakes and thunderings, rent the mountain, and blotted out every trace of the man and his dwelling with a flood of fire."

Another story goes that in the form of a maiden the goddess appeared to a young chief at the head of a toboggan slide and asked for a ride on his sled. He refused her, and started down without her. Soon, hearing a roar as of thunder and looking back, he saw a lava torrent chasing him and bearing on its highest wave the maiden, whom he then knew to be the goddess Pele. Down the hill and across the plain his toboggan shot, followed by the flaming river of molten rock. The chief, however, reached the ocean at last and found safety in the waters.[Pg 45]

This condensed story of the Shark King is also a typical Hawaiian tale:

The King Shark, while sporting in the water, watched a beautiful maiden diving into a pool, and fell in love with her. As king sharks can evidently take whatever form they please, he turned himself into a handsome man and waited for her on the rocks. Here the maiden came one day to seek shellfish, which she was fond of eating. While she was gathering them a huge wave swept her off her feet, and the handsome shark man saved her life. As a matter of course, she straightway fell in love with him. So it happened that one day they were married; but it was only when her child was born that the shark man confided to her who he really was, and that he must now disappear. As he left, he cautioned her never to give their child any meat, or misfortune would follow.

The child was a fine boy, and was quite like other children except that he bore on his back the mark of the great mouth of the shark. As he grew older he ate with the men instead of the women, as was the custom, and his grandfather, not heeding the warning but wishing to make his grandson strong, so that some day he might become a chief, gave him the forbidden meat. When in company, the boy wore a cape[Pg 46] to cover the scar on his back, and he always went swimming alone, but when in the water he remembered his father, and it was then that he would turn into a shark himself. The more meat the boy ate the more he wanted, and in time it was noticed that children began to disappear. They would go in bathing and never return. The people became suspicious, and one day they tore the boy's mantle off him and saw the shark's mouth upon his back. There was great consternation, and at last he was ordered to be burned alive. He had been bound with ropes and was waiting for the end, but while the fire was kindling he called on his father, King Shark, for help, and so it was that he was able to burst the ropes and rush into the water, where he turned into a shark and escaped.

The mother then confessed that she had married the Shark King. The chiefs and the high priests held a council and decided that it would be better to offer sacrifices to appease him rather than to kill the mother. This they did, and for that reason King Shark promised that his son should leave the shores of the island of Hawaii forever. It was true, he did leave this island, but he visited other islands and continued his bad habits, until one day he was really caught just as he was turning from a man[Pg 47] into a shark on the beach in shallow water. He was bound and hauled up a canyon, where they built a fire from the bamboo of the sacred grove. But the shark was so large that they had to chop down one tree after another for his funeral pyre, until the sacred grove had almost disappeared. This so angered the god of the forest that he changed the variety of bamboo in this region; it is no longer sharp-edged like other bamboo on the Islands.

awaiian myths and traditions are confused and unreliable, and we know little real history of the "Bright Land," the "Land of Rainbows," before the coming of Captain Cook, in 1778. We do know, however, that, in those early days, the different tribes continually carried on a savage warfare among themselves. Not until the latter part of the eighteenth century did there arise a native chieftain powerful enough to subdue all the islands under his sway and bring peace among the warring tribes. This chief was Kamehameha I, or Kamehameha the Great, often called the Napoleon of the Pacific. The authentic history of Hawaii really begins with his reign. His portrait in the Executive Building in Honolulu shows him as a stern warrior.

The Japanese, as well as the Spaniards, had long known of the existence of islands in that part of the Pacific Ocean. Tradition tells of some shipwrecked Spanish sailors and some[Pg 49] Japanese who settled there at a very early date. These Islands were, however, brought to the notice of the civilized world for the first time by Captain Cook.

The Englishmen were received by the simple natives with awe and wonder, Captain Cook himself was declared by the priests to be an incarnation of Lono, god of the forest and husband of the goddess Laka, and abundant provisions were brought to the ship as an offering to this deity. Had the natives been even decently treated, there would have been no tragic sequel to the story, but Cook's crew were allowed complete and unrestrained license on shore. As it was, there was no serious trouble during their first visit, but when they returned in a few months and again exacted contributions the supplies were given grudgingly. The English vessel sailed away, but was unfortunately obliged to put back for repairs, and it was then that the fight occurred between the foreigners and the natives in which Captain Cook met his death. It was this famous voyager who gave the name of Sandwich Islands to the group, in honour of his patron, Lord Sandwich. They were known by that name for many years, but it was never the official designation, and is now seldom used.[Pg 50]

The discovery of the Islands by Englishmen and Americans was fraught with evil consequences to the natives, as they brought with them new diseases, and they also introduced intoxicating liquors, and it soon became the custom for whaling vessels in the Pacific to call there and make them the scene of debauchery and licentiousness. It has been said that at that time sea captains recognized no laws, either of God or man, west of Cape Horn. We must not fail to note, however, that even in those early days there were a few white men who really sought the good of the Hawaiians.

Isaac Davis and John Young were two of these men. When the crew of an American vessel was massacred these two were spared, and they continued to live in the Islands until their death. They were a bright contrast to most seamen who visited Hawaii at that period. They accepted the responsibility imposed by their training in civilization, exerting a great influence for good, and were even advisers and teachers of King Kamehameha I.

Captain George Vancouver, who visited the Islands three times in the last decade of the eighteenth century under commission from the British Government, was another white man whose work there was wholly good. He landed[Pg 51] the first sheep and cattle ever seen there, and induced the king to proclaim them tabu for ten years so that they might have time to increase, after which women were to be allowed to eat them as well as men. He introduced some valuable plants, such as the grapevine, the orange and the almond, and brought the people seeds of garden vegetables. He refused them firearms. Under his direction the first sailing vessel was built there and called the Britannia. Vancouver so won over the natives by his kind treatment that the chiefs ceded the Islands to Great Britain and raised the British flag in February, 1794. He left them with a promise to come again and bring them teachers of Christianity and the industries of civilization. His death, however, prevented his return, and Great Britain never took formal possession.

Kamehameha I, who, at the time of Cook's arrival, was only a chief on the island of Hawaii, joined in the tribal wars, conquered the other chiefs of that island, and became king. While this conquest was in progress, an eruption of Kilauea destroyed a large part of the opposing army and convinced Kamehameha that Pele was on his side.

The subjugation of Maui and Oahu followed. At the great battle fought in the Nuuanu Val[Pg 52]ley, the king of Oahu was defeated and driven with his army over the Pali. Kamehameha was twice prevented from invading Kauai, but some years later it was ceded to him by its ruler.

After the conquest of Oahu was completed, in 1795, it was Kamehameha's work to build up a strong central government. According to the feudal system that had existed in the Islands up to that time, all the land was considered to belong to the king, who divided it among the great chiefs, these in turn apportioning their shares among the lesser chiefs, of whom the people held their small plots of ground. All paid tribute to those above them in rank. Kamehameha I, in order to increase his own power and destroy that of the chiefs, distributed their lands to them in widely separated portions rather than in large, continuous tracts, as had been the custom previously.

Kamehameha was elected by the chiefs as king of all the Hawaiian Islands, and founded the dynasty called by his name, under which his people had peace for nearly eighty years. He adroitly used the tabu to strengthen his power, and availing himself of the wise advice of the few benevolent foreigners whom he knew, he sought in every way to further the best inter[Pg 53]ests of his people. He has been called "one of the notable men of the earth."

The bronze statue of Kamehameha I stands in front of the Judiciary Building in Honolulu. The anniversary of the birthday of the great ruler occurs in June, and is celebrated by the natives far and near. His statue is dressed in his royal cape of bird feathers and decorated with leis of flowers by the sons and daughters of Hawaii.

The strength of character of Kamehameha I is shown in many ways, but especially in the stand he took in regard to liquor, which was having a disastrous effect on his people. When he became convinced that alcoholic drinks were injurious, he decided never to taste them again.

Before the close of his life, he made a noble effort to prevent the use of liquor by his people. All the chiefs on the island of Hawaii were summoned to meet in an immense grass house, which he had ordered built at Kailua, the ancient capital, solely for this council. When they were all assembled the King entered in his magnificent cape of mamo bird feathers, and drawing himself up to his full height, uttered this command:

"Return to your homes, and destroy every[Pg 54] distillery on the island! Make no more intoxicating liquors!"

At the death of Kamehameha I, in 1819, his son Liholiho succeeded him as Kamehameha II. Unfortunately, he did not carry out his father's wishes. He was like his father in nothing but name, being weak and dissipated, and easily influenced by the unscrupulous foreigners who surrounded him. Many changes took place in his reign, but so strong had the government been made by his father that it survived them all. Fortunately, too, an able woman, one of the wives of the first Kamehameha, was associated with the King as Queen Regent.

Before the end of the year 1819 the Hawaiians had burned their idols and abolished tabu. It was the influence of Europeans that had led to these radical changes. Early in the nineteenth century the trade in sandalwood sprang up, in return for which many manufactured articles were imported, especially rum, firearms and cheap ornaments. This trade brought increased numbers of foreigners to the Islands, and their sneers undermined the faith of the people in their old gods without offering them any other religion as a substitute.

In this connection, we are told that twice Kamehameha I made an effort to learn something[Pg 55] about Christianity. When he heard that the people of Tahiti had embraced the new faith, he inquired of a foreigner about it, but the man could tell him nothing. Again, just before his death, he asked an American trader to tell him about the white man's God, but, as a native afterward reported to the missionaries, "He no tell him." This greatest of the Hawaiians prepared the way, but he himself died without hearing of Christ.

The Hawaiians had now swept their house clean, and they were ready for an entirely new set of furnishings. In a land far away beyond the Pacific these were preparing for them, and the short reign of this second Kamehameha was made memorable not only by the changes already mentioned but also by the coming of the missionaries, in 1820.

Obookiah, whose real name was Opukahaia, was a young Hawaiian who shipped as seaman on a whaler about 1817, and was taken to New Haven, where he found people who befriended him and undertook to give him an education. They sent him to the Foreign Mission School which had been established at Cornwall, Connecticut, for young men from heathen lands. Among his mates were four others from his native islands. It had been his purpose to carry[Pg 56] the Christian religion to his home, but he was taken seriously ill at the school and on his death-bed he pleaded with his new friends not to forget his country. His appeal led the first missionaries to embark for those far-away shores. Three young Hawaiians from the school went with them as assistants.

When the Christian teachers arrived, it is said that the captain of the ship sent an officer ashore with the Hawaiian boys. After awhile they returned, shouting out their wonderful news:

"Liholiho is king. The tabus are abolished. The idols are burnt. There has been war. Now there is peace."

The missionaries received a cordial welcome from some of the natives of high station. The former high priest met them with the words,

"I knew that the wooden images of gods carved by our own hands could not supply our wants, but I worshiped them because it was a custom of our fathers.... My thought has always been, there is only one great God, dwelling in the heavens."

The chief Kalaimoku, neatly dressed in foreign clothes, boarded the ship, accompanied by the two queen dowagers, and welcomed each of the newcomers in turn with a warm hand clasp.[Pg 57] One of the queens asked the American women to make her a white dress while they were sailing along the coast, to wear on meeting the King. When she went ashore in her new white mother hubbard, a shout greeted her from hundreds of throats! Because the gown was so loose that she could both run and stand in it, the natives called it a holoku, meaning "run-stand." It became the national dress. The queens afterward sent the missionaries sugar-cane, bananas, cocoanuts and other foods, as a token of their pleasure.

The Americans were received kindly by the King after explaining their mission and were allowed to remain in the Islands. They had many trials and privations, but they were strong in their faith, and within twenty years they had the joy of baptizing thousands of converts.

Kamehameha II, fearing the Russians—one trader had actually gone so far as to hoist the Russian flag over some forts that he had built—visited the United States with his queen and then went on to England to ask for protection, which was promised them by George IV. They both died there, in 1824, and their remains were sent home in a British man-of-war, commanded by Lord Byron, cousin of the poet.

When Kamehameha III was made ruler, all[Pg 58] the unprincipled white men in Oahu immediately set to work to lead him into every form of dissipation, but they were not to succeed with him as they had with his predecessor. There were men of ability in that band of missionaries, and they had great influence with him. These faithful advisers had a large share in framing the liberal constitution which he granted.

It is of special interest to note that, the year before the constitution was adopted, a Bill of Rights was promulgated, which set forth the fundamental principles of government and is often called the Hawaiian Magna Charta. An eminent writer has given us the provisions of this document.

It asserts the right of every man to "life, limb, liberty, freedom from oppression, the earnings of his hand, and the productions of his mind, not however, to those who act in violation of the laws. It gave natives for the first time the right to hold land in fee simple; before that the King had owned all the land, and no one could buy it. In this document it is also declared that 'protection is hereby secured to the persons of all the people, together with their lands, their building lots and all their property while they conform to the laws of the kingdom,'[Pg 59] and that laws must be enacted for the protection of subjects as well as rulers."

A commission was also formed to determine the ownership of the land. By this commission one-third of all the land was confirmed to the King, one-third to the chiefs, and one-third to the common people. As far as possible the people's share was so divided that each person received the piece of ground that he was living on. The King and many of the chiefs turned over one-half of their share to the Government, which soon held nearly one-third of all the landed property in the kingdom.

The first constitution was framed in 1840. About ten years later an improved one was adopted. The legislature was to meet in two houses. The nobles were to be chosen by the King for life, and were not to be more than thirty in number. There were to be not less than twenty-four representatives, who were to be elected by the people. The Supreme Court was to be composed of three members—a chief justice and two associate justices. Four circuit courts were to be established, and besides the judges for these, each district was to have a judge who should settle petty cases.

It was in 1825, early in the reign of Kamehameha III, that Kapiolani, daughter of the[Pg 60] high chief Keawe-mauhili, of Hilo, defied the power of Pele. Having become a Christian, she determined to give her people an object lesson on the powerlessness of their gods. With a retinue of eighty persons she journeyed, most of the way on foot, one hundred miles to the crater of Kilauea. When near the crater, she was met by the priestess of Pele, who threatened her with death if she broke the tabus. But Kapiolani ate the sacred ohelo berries without first offering some to the goddess, and undaunted, made her way with her followers down five hundred feet to the "Black Ledge." There, on the very margin of the fiery lake of Halemaumau, she addressed her followers in these ringing words:

"Jehovah is my God. He kindled these fires.... I fear not Pele. If I perish by the anger of Pele, then you may fear the power of Pele; but if I trust in Jehovah, and he should save me from the wrath of Pele, then you must fear and serve the Lord Jehovah. All the gods of Hawaii are vain!" Then they sang a hymn of praise to Jehovah, and wended their way back to the crater's rim in safety.

It was during the reign of Kamehameha III that the United States, France and Great Britain recognized the independence of the Ha[Pg 61]waiian Islands. Before this news reached the Pacific, however, Lord George Paulet, a British naval officer, took possession and hoisted the British flag, because the King refused to yield to his demands. Five months later, Admiral Thomas, in command of Great Britain's fleet in the East, appeared at Honolulu and restored the country to the natives. In recognition, an attractive public park was named for him. At the thanksgiving service held on that day, the King uttered the words which were afterward adopted as the motto of the nation, the translation of which is: "In righteousness is the life of the land."

The independence of Hawaii was only once again threatened by a foreign power, when a French admiral took possession of the fort and the government buildings at Honolulu for a few days. Indeed, that independence was not only recognized but guaranteed by France, England and the United States.

Many of the missionaries settled in Hawaii, and their descendants have become rich and prominent citizens. Hawaii owes much to them. So far as lay in their power, they taught the people trades and introduced New England ideals of government and education. Two years after they arrived a spelling book was printed,[Pg 62] and a few years later the printing office sent out a newspaper in the native language. The first boarding school for boys was started by Lorrin Andrews in 1831, on Maui, and it was not long after that one was established for girls. The Hilo boarding school, which came later, was the one that General Armstrong took many suggestions from for his work for the coloured people, at Hampton Institute in Virginia. Indeed, so eager were the Hawaiians to learn of their new teachers that whole villages came to the mission stations, gray-haired men and women becoming pupils, and the chiefs leading the way.