| Transcriber's note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

are listed at the end of the text, after the notes.

|

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| Introduction | ix | |

| I. | The Origin of Armory | 1 |

| II. | The Status and the Meaning of a Coat of Arms in Great Britain | 19 |

| III. | The Heralds and Officers of Arms | 27 |

| IV. | Heraldic Brasses | 49 |

| V. | The Component Parts of an Achievement | 57 |

| VI. | The Shield | 60 |

| VII. | The Field of a Shield and the Heraldic Tinctures | 67 |

| VIII. | The Rules of Blazon | 99 |

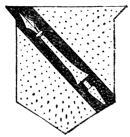

| IX. | The so-called Ordinaries and Sub-Ordinaries | 106 |

| X. | The Human Figure in Heraldry | 158 |

| XI. | The Heraldic Lion | 172 |

| XII. | Beasts | 191 |

| XIII. | Monsters | 218 |

| XIV. | Birds | 233 |

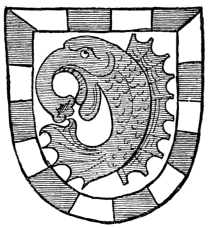

| XV. | Fish | 253 |

| XVI. | Reptiles | 257 |

| XVII. | Insects | 260 |

| XVIII. | Trees, Leaves, Fruits, and Flowers | 262 |

| XIX. | Inanimate Objects | 281 |

| XX. | The Heraldic Helmet | 303 |

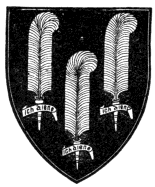

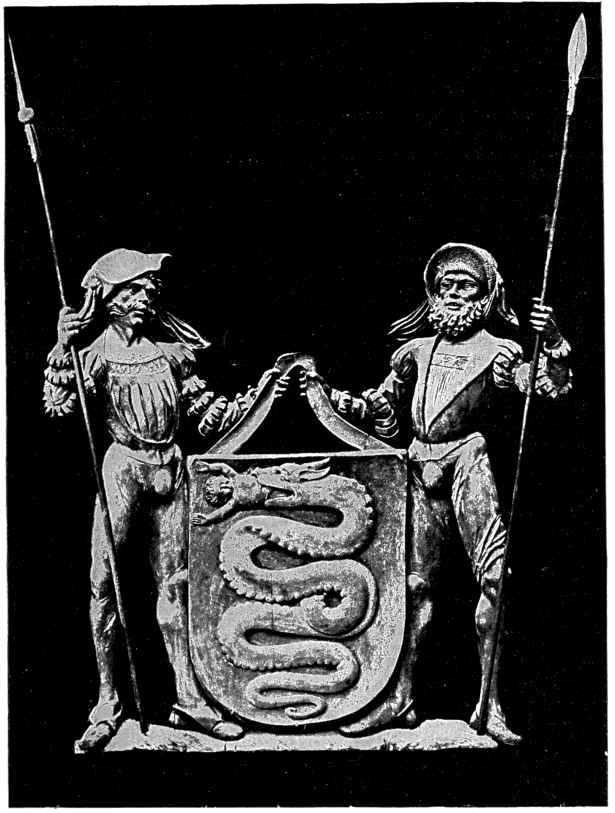

| {viii} XXI. | The Crest | 326 |

| XXII. | Crowns and Coronets | 350 |

| XXIII. | Crest Coronets and Chapeaux | 370 |

| XXIV. | The Mantling or Lambrequin | 383 |

| XXV. | The Torse or Wreath | 402 |

| XXVI. | Supporters | 407 |

| XXVII. | The Compartment | 441 |

| XXVIII. | Mottoes | 448 |

| XXIX. | Badges | 453 |

| XXX. | Heraldic Flags, Banners, and Standards | 471 |

| XXXI. | Marks of Cadency | 477 |

| XXXII. | Marks of Bastardy | 508 |

| XXXIII. | The Marshalling of Arms | 523 |

| XXXIV. | The Armorial Insignia of Knighthood | 561 |

| XXXV. | The Armorial Bearings of a Lady | 572 |

| XXXVI. | Official Heraldic Insignia | 580 |

| XXXVII. | Augmentations of Honour | 589 |

| XXXVIII. | Ecclesiastical Heraldry | 600 |

| XXXIX. | Arms of Dominion and Sovereignty | 607 |

| XL. | Hatchments | 609 |

| XLI. | The Union Jack | 611 |

| XLII. | "Seize-Quartiers" | 618 |

| Index | 623 |

Too frequently it is the custom to regard the study of the science of Armory as that of a subject which has passed beyond the limits of practical politics. Heraldry has been termed "the shorthand of History," but nevertheless the study of that shorthand has been approached too often as if it were but the study of a dead language. The result has been that too much faith has been placed in the works of older writers, whose dicta have been accepted as both unquestionably correct at the date they wrote, and, as a consequence, equally binding at the present day.

Since the "Boke of St. Albans" was written, into the heraldic portion of which the author managed to compress an unconscionable amount of rubbish, books and treatises on the subject of Armory have issued from the press in a constant succession. A few of them stand a head and shoulders above the remainder. The said remainder have already sunk into oblivion. Such a book as "Guillim" must of necessity rank in the forefront of any armorial bibliography; but any one seeking to judge the Armory of the present day by the standards and ethics adopted by that writer, would find himself making mistake after mistake, and led hopelessly astray. There can be very little doubt that the "Display of Heraldry" is an accurate representation of the laws of Armory which governed the use of Arms at the date the book was written; and it correctly puts forward the opinions which were then accepted concerning the past history of the science.

There are two points, however, which must be borne in mind.

The first is that the critical desire for accuracy which fortunately seems to have been the keynote of research during the nineteenth century, has produced students of Armory whose investigations into facts have swept away the fables, the myths, and the falsehood which had collected around the ancient science, and which in their preposterous assertions had earned for Armory a ridicule, a contempt, and a disbelief which the science itself, and moreover the active practice of the science, had never at any time warranted or deserved. The desire to gratify the vanity of illustrious patrons rendered the mythical traditions attached to Armory more difficult to explode than in the cases of those other sciences in which no one has a personal interest in {x}upholding the wrong; but a study of the scientific works of bygone days, and the comparison, for example, of a sixteenth or seventeenth century medical book with a similar work of the present day, will show that all scientific knowledge during past centuries was a curious conglomeration of unquestionable fact, interwoven with and partly obscured by a vast amount of false information, which now can either be dismissed as utter rubbish or controverted and disproved on the score of being plausible untruth. Consequently, Armory, no less than medicine, theology, or jurisprudence, should not be lightly esteemed because our predecessors knew less about the subject than is known at the present day, or because they believed implicitly dogma and tradition which we ourselves know to be and accept as exploded. Research and investigation constantly goes on, and every day adds to our knowledge.

The second point, which perhaps is the most important, is the patent fact that Heraldry and Armory are not a dead science, but are an actual living reality. Armory may be a quaint survival of a time with different manners and customs, and different ideas from our own, but the word "Finis" has not yet been written to the science, which is still slowly developing and altering and changing as it is suited to the altered manners and customs of the present day. I doubt not that this view will be a startling one to many who look upon Armory as indissolubly associated with parchments and writings already musty with age. But so long as the Sovereign has the power to create a new order of Knighthood, and attach thereto Heraldic insignia, so long as the Crown has the power to create a new coronet, or to order a new ceremonial, so long as new coats of arms are being called into being,—for so long is it idle to treat Armory and Heraldry as a science incapable of further development, or as a science which in recent periods has not altered in its laws.

The many mistaken ideas upon Armory, however, are not all due to the two considerations which have been put forward. Many are due to the fact that the hand-books of Armory professing to detail the laws of the science have not always been written by those having complete knowledge of their subject. Some statement appears in a textbook of Armory, it is copied into book after book, and accepted by those who study Armory as being correct; whilst all the time it is absolutely wrong, and has never been accepted or acted upon by the Officers of Arms. One instance will illustrate my meaning. There is scarcely a text-book of Armory which does not lay down the rule, that when a crest issues from a coronet it must not be placed upon a wreath. Now there is no rule whatever upon the subject; and instances are frequent, both in ancient and in modern grants, in which coronets have been granted to be borne upon wreaths; and the wreath should {xi}be inserted or omitted according to the original grant of the crest. Consequently, the so-called rule must be expunged.

Another fruitful source of error is the effort which has frequently been made to assimilate the laws of Armory prevailing in the three different kingdoms into one single series of rules and regulations. Some writers have even gone so far as to attempt to assimilate with our own the rules and regulations which hold upon the Continent. As a matter of fact, many of the laws of Arms in England and Scotland are radically different; and care needs to be taken to point out these differences.

The truest way to ascertain the laws of Armory is by deduction from known facts. Nevertheless, such a practice may lead one astray, for the number of exceptions to any given rule in Armory is always great, and it is sometimes difficult to tell what is the rule, and which are the exceptions. Moreover, the Sovereign, as the fountain of honour, can over-ride any rule or law of Arms; and many exceptional cases which have been governed by specific grants have been accepted in times past as demonstrating the laws of Armory, when they have been no more than instances of exceptional favour on the part of the Crown.

In England no one is compelled to bear Arms unless he wishes; but, should he desire to do so, the Inland Revenue requires a payment of one or two guineas, according to the method of use. From this voluntary taxation the yearly revenue exceeds £70,000. This affords pretty clear evidence that Armory is still decidedly popular, and that its use and display are extensive; but at the same time it would be foolish to suppose that the estimation in which Armory is held, is equal to, or approaches, the romantic value which in former days was attached to the inheritance of Arms. The result of this has been—and it is not to be wondered at—that ancient examples are accepted and extolled beyond what should be the case. It should be borne in mind that the very ancient examples of Armory which have come down to us, may be examples of the handicraft of ignorant individuals; and it is not safe to accept unquestioningly laws of Arms which are deduced from Heraldic handicraft of other days. Most of them are correct, because as a rule such handicraft was done under supervision; but there is always the risk that it has not been; and this risk should be borne in mind when estimating the value of any particular example of Armory as proof or contradiction of any particular Armorial law. There were "heraldic stationers" before the present day.

A somewhat similar consideration must govern the estimate of the Heraldic art of a former day. To every action we are told there is a reaction; and the reaction of the present day, admirable and commendable as it undoubtedly is, which has taken the art of Armory back to the style in vogue in past centuries, needs to be kept within intelligent {xii}bounds. That the freedom of design and draughtsmanship of the old artists should be copied is desirable; but at the same time there is not the slightest necessity to copy, and to deliberately copy, the crudeness of execution which undoubtedly exists in much of the older work. The revulsion from what has been aptly styled "the die-sinker school of heraldry" has caused some artists to produce Heraldic drawings which (though doubtless modelled upon ancient examples) are grotesque to the last degree, and can be described in no other way.

In conclusion, I have to repeat my grateful acknowledgments to the many individuals who assisted me in the preparation of my "Art of Heraldry," upon which this present volume is founded, and whose work I have again made use of.

The very copious index herein is entirely the work of my professional clerk, Mr. H. A. Kenward, for which I offer him my thanks. Only those who have had actual experience know the tedious weariness of compiling such an index.

23 Old Buildings,

Lincoln's Inn, W. C.

rmory is that science of which the rules and the laws govern the use, display, meaning, and knowledge of the pictured signs and emblems appertaining to shield, helmet, or banner. Heraldry has a wider meaning, for it comprises everything within the duties of a herald; and whilst Armory undoubtedly is Heraldry, the regulation of ceremonials and matters of pedigree, which are really also within the scope of Heraldry, most decidedly are not Armory.

"Armory" relates only to the emblems and devices. "Armoury" relates to the weapons themselves as weapons of warfare, or to the place used for the storing of the weapons. But these distinctions of spelling are modern.

The word "Arms," like many other words in the English language, has several meanings, and at the present day is used in several senses. It may mean the weapons themselves; it may mean the limbs upon the human body. Even from the heraldic point of view it may mean the entire achievement, but usually it is employed in reference to the device upon the shield only.

Of the exact origin of arms and armory nothing whatever is definitely known, and it becomes difficult to point to any particular period as the period covering the origin of armory, for the very simple reason that it is much more difficult to decide what is or is not to be admitted as armorial. {2}

Until comparatively recently heraldic books referred armory indifferently to the tribes of Israel, to the Greeks, to the Romans, to the Assyrians and the Saxons; and we are equally familiar with the "Lion of Judah" and the "Eagle of the Cæsars." In other directions we find the same sort of thing, for it has ever been the practice of semi-civilised nations to bestow or to assume the virtues and the names of animals and of deities as symbols of honour. We scarcely need refer to the totems of the North American Indians for proof of such a practice. They have reduced the subject almost to an exact science; and there cannot be the shadow of a doubt that it is to this semi-savage practice that armory is to be traced if its origin is to be followed out to its logical and most remote beginning. Equally is it certain that many recognised heraldic figures, and more particularly those mythical creatures of which the armorial menagerie alone has now cognisance, are due to the art of civilisations older than our own, and the legends of those civilisations which have called these mythical creatures into being.

The widest definition of armory would have it that any pictorial badge which is used by an individual or a family with the meaning that it is a badge indicative of that person or family, and adopted and repeatedly used in that sense, is heraldic. If such be your definition, you may ransack the Scriptures for the arms of the tribes of Israel, the writings of the Greek and Roman poets for the decorations of the armour and the persons of their heroes, mythical and actual, and you may annex numberless "heraldic" instances from the art of Nineveh, of Babylon, and of Egypt. Your heraldry is of the beginning and from the beginning. It is fact, but is it heraldry? The statement in the "Boke of St. Albans" that Christ was a gentleman of coat armour is a fable, and due distinction must be had between the fact and the fiction in this as in all other similar cases.

Mr. G. W. Eve, in his "Decorative Heraldry," alludes to and illustrates many striking examples of figures of an embryonic type of heraldry, of which the best are one from a Chaldean bas-relief 4000 B. C., the earliest known device that can in any way be called heraldic, and another, a device from a Byzantine silk of the tenth century. Mr. Eve certainly seems inclined to follow the older heraldic writers in giving as wide an interpretation as possible to the word heraldic, but it is significant that none of these early instances which he gives appear to have any relation to a shield, so that, even if it be conceded that the figures are heraldic, they certainly cannot be said to be armorial. But doubtless the inclusion of such instances is due to an attempt, conscious or unconscious, on the part of the writers who have taken their stand on the side of great antiquity to so frame the definition of armory that it shall include everything heraldic, and due perhaps somewhat to the half unconscious {3}reasoning that these mythical animals, and more especially the peculiarly heraldic positions they are depicted in, which nowadays we only know as part of armory, and which exist nowhere else within our knowledge save within the charmed circle of heraldry, must be evidence of the great antiquity of that science or art, call it which you will. But it is a false deduction, due to a confusion of premise and conclusion. We find certain figures at the present day purely heraldic—we find those figures fifty centuries ago. It certainly seems a correct conclusion that, therefore, heraldry must be of that age. But is not the real conclusion, that, our heraldic figures being so old, it is evident that the figures originated long before heraldry was ever thought of, and that instead of these mythical figures having been originated by the necessities of heraldry, and being part, or even the rudimentary origin of heraldry, they had existed for other reasons and purposes—and that when the science of heraldry sprang into being, it found the whole range of its forms and charges already existing, and that none of these figures owe their being to heraldry? The gryphon is supposed to have originated, as is the double-headed eagle, from the dimidiation of two coats of arms resulting from impalement by reason of marriage. Both these figures were known ages earlier. Thus departs yet another of the little fictions which past writers on armory have fostered and perpetuated. Whether the ancient Egyptians and Assyrians knew they were depicting mythical animals, and did it, intending them to be symbolical of attributes of their deities, something beyond what they were familiar with in their ordinary life, we do not know; nor indeed have we any certain knowledge that there have never been animals of which their figures are but imperfect and crude representations.

But it does not necessarily follow that because an Egyptian artist drew a certain figure, which figure is now appropriated to the peculiar use of armory, that he knew anything whatever of the laws of armory. Further, where is this argument to end? There is nothing peculiarly heraldic about the lion passant, statant, dormant, couchant, or salient, and though heraldic artists may for the sake of artistic appearance distort the brute away from his natural figure, the rampant is alone the position which exists not in nature; and if the argument is to be applied to the bitter end, heraldry must be taken back to the very earliest instance which exists of any representation of a lion. The proposition is absurd. The ancient artists drew their lions how they liked, regardless of armory and its laws, which did not then exist; and, from decorative reasons, they evolved a certain number of methods of depicting the positions of e.g. the lion and the eagle to suit their decorative purposes. When heraldry came into existence it came in as an adjunct of decoration, and it necessarily followed that the whole of the positions in which the {4}craftsmen found the eagle or the lion depicted were appropriated with the animals for heraldry. That this appropriation for the exclusive purposes of armory has been silently acquiesced in by the decorative artists of later days is simply proof of the intense power and authority which accrued later to armory, and which was in fact attached to anything relating to privilege and prerogative. To put it baldly, the dominating authority of heraldry and its dogmatic protection by the Powers that were, appropriated certain figures to its use, and then defied any one to use them for more humble decorative purposes not allied with armory. And it is the trail of this autocratic appropriation, and from the decorative point of view this arrogant appropriation, which can be traced in the present idea that a griffin or a spread eagle, for example, must be heraldic. Consequently the argument as to the antiquity of heraldry which is founded upon the discovery of the heraldic creature in the remote ages goes by the board. One practical instance may perhaps more fully demonstrate my meaning. There is one figure, probably the most beautiful of all of those which we owe to Egypt, which is now rapidly being absorbed into heraldry. I refer to the Sphinx. This, whilst strangely in keeping with the remaining mythical heraldic figures, for some reason or other escaped the exclusive appropriation of armorial use until within modern times. One of the earliest instances of its use in recognised armory occurs in the grant to Sir John Moore, K.B., the hero of Corunna, and another will be found in the augmentation granted to Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, K.B. Since then it has been used on some number of occasions. It certainly remained, however, for the late Garter King of Arms to evolve from the depths of his imagination a position which no Egyptian sphinx ever occupied, when he granted two of them as supporters to the late Sir Edward Malet, G.C.B. The Sphinx has also been adopted as the badge of one of his Majesty's regiments, and I have very little doubt that now Egypt has come under our control the Sphinx will figure in some number of the grants of the future to commemorate fortunes made in that country, or lifetimes spent in the Egyptian services. If this be so, the dominating influence of armory will doubtless in the course of another century have given to the Sphinx, as it has to many other objects, a distinctly heraldic nature and character in the mind of the "man in the street" to which we nowadays so often refer the arbitrament between conflicting opinions. Perhaps in the even yet more remote future, when the world in general accepts as a fact that armory did not exist at the time of the Norman Conquest, we shall have some interesting and enterprising individual writing a book to demonstrate that because the Sphinx existed in Egypt long before the days of Cleopatra, heraldry must of necessity be equally antique. {5}

I have no wish, however, to dismiss thus lightly the subject of the antiquity of heraldry, because there is one side of the question which I have not yet touched upon, and that is, the symbolism of these ancient and so-called heraldic examples. There is no doubt whatever that symbolism forms an integral part of armory; in fact there is no doubt that armory itself as a whole is nothing more or less than a kind of symbolism. I have no sympathy whatever with many of the ideas concerning this symbolism, which will be found in nearly all heraldic books before the day of the late J. R. Planché, Somerset Herald, who fired the train which exploded then and for ever the absurd ideas of former writers. That an argent field meant purity, that a field of gules meant royal or even martial ancestors, that a saltire meant the capture of a city, or a lion rampant noble and enviable qualities, I utterly deny. But that nearly every coat of arms for any one of the name of Fletcher bears upon it in some form or another an arrow or an arrow-head, because the origin of the name comes from the occupation of the fletcher, who was an arrow-maker, is true enough. Symbolism of that kind will be found constantly in armory, as in the case of the foxes and foxes' heads in the various coats of Fox, the lions in the coats of arms of Lyons, the horse in the arms of Trotter, and the acorns in the arms of Oakes; in fact by far the larger proportion of the older coats of arms, where they can be traced to their real origin, exhibit some such derivation. There is another kind of symbolism which formerly, and still, favours the introduction of swords and spears and bombshells into grants of arms to military men, that gives bezants to bankers and those connected with money, and that assigns woolpacks and cotton-plants to the shields of textile merchants; but that is a sane and reasonable symbolism, which the reputed symbolism of the earlier heraldry books was not.

It has yet to be demonstrated, however, though the belief is very generally credited, that all these very ancient Egyptian and Assyrian figures of a heraldic character had anything of symbolism about them. But even granting the whole symbolism which is claimed for them, we get but little further. There is no doubt that the eagle from untold ages has had an imperial symbolism which it still possesses. But that symbolism is not necessarily heraldic, and it is much more probable that heraldry appropriated both the eagle and its symbolism ready made, and together: consequently, if, as we have shown, the existence of the eagle is not proof of the coeval existence of heraldry, no more is the existence of the symbolical imperial eagle. For if we are to regard all symbolism as heraldic, where are we either to begin or to end? Church vestments and ecclesiastical emblems are symbolism run riot; in fact they are little else: but by no stretch of imagination can these be {6}considered heraldic with the exception of the few (for example the crosier, the mitre, and the pallium) which heraldry has appropriated ready made. Therefore, though heraldry appropriated ready made from other decorative art, and from nature and handicraft, the whole of its charges, and though it is evident heraldry also appropriated ready made a great deal of its symbolism, neither the earlier existence of the forms which it appropriated, nor the earlier existence of their symbolism, can be said to weigh at all as determining factors in the consideration of the age of heraldry. Sloane Evans in his "Grammar of Heraldry" (p. ix.) gives the following instances as evidence of the greater antiquity, and they are worthy at any rate of attention if the matter is to be impartially considered.

"The antiquity of ensigns and symbols may be proved by reference to Holy Writ.

"1. 'Take ye the sum of all the congregation of the children of Israel, after their families, by the house of their fathers, with the number of their names.... And they assembled all the congregation together on the first day of the second month; and they declared their pedigrees after their families, by the house of their fathers, according to the number of the names, from twenty years old and upward.... And the children of Israel shall pitch their tents, every man by his own camp, and every man by his own standard, throughout their hosts' (Numbers i. 2, 18, 52).

"2. 'Every man of the children of Israel shall pitch by his own standard, with the ensign of their father's house' (Numbers ii. 2).

"3. 'And the children of Israel did according to all that the Lord commanded Moses: so they pitched by their standards, and so they set forward, every one after their families, according to the house of their fathers' (Numbers ii. 34)."

The Latin and Greek poets and historians afford numerous instances of the use of symbolic ornaments and devices. It will be sufficient in this work to quote from Æschylus and Virgil, as poets; Herodotus and Tacitus, as historians.

The poet here introduces a dialogue between Eteocles, King of Thebes, the women who composed the chorus, and a herald (κηρυξ), which latter is pointing out the seven captains or chiefs of the army of Adrastus against Thebes; distinguishing one from another by the emblematical devices upon their shields.

"... Frowning he speaks, and shakes

The dark crest streaming o'er his shaded helm

In triple wave; whilst dreadful ring around

The brazen bosses of his shield, impress'd

{7}With his proud argument:—'A sable sky

Burning with stars; and in the midst full orb'd

A silver moon;'—the eye of night o'er all,

Awful in beauty, forms her peerless light."

"On his proud shield portray'd: 'A naked man

Waves in his hand a blazing torch;' beneath

In golden letters—'I will fire the city.'"

"... No mean device

Is sculptured on his shield: 'A man in arms,

His ladder fix'd against the enemies' walls,

Mounts, resolute, to rend their rampires down;'

And cries aloud (the letters plainly mark'd),

'Not Mars himself shall beat me from the Tow'rs.'"

"... On its orb, no vulgar artist

Expressed this image: 'A Typhæus huge,

Disgorging from his foul enfounder'd jaws,

In fierce effusion wreaths of dusky smoke.

Signal of kindling flames; its bending verge

With folds of twisted serpents border'd round.'

With shouts the giant chief provokes the war,

And in the ravings of outrageous valour

Glares terror from his eyes ..."

"... Upon his clashing shield,

Whose orb sustains the storm of war, he bears

The foul disgrace of Thebes:—'A rav'nous Sphynx

Fixed to the plates: the burnish'd monster round

Pours a portentous gleam: beneath her lies

A Theban mangled by her cruel fangs:'—

'Gainst this let each brave arm direct the spear."

"So spoke the prophet; and with awful port

Advanc'd his massy shield, the shining orb

Bearing no impress, for his gen'rous soul

Wishes to be, not to appear, the best;

And from the culture of his modest worth

Bears the rich fruit of great and glorious deeds."

"... His well-orb'd shield he holds,

New wrought, and with a double impress charg'd:

A warrior, blazing all in golden arms,

A female form of modest aspect leads,

Expressing justice, as th' inscription speaks,

'Yet once more to his country, and once more

To his Paternal Throne I will restore him'—

Such their devices ..."

"Choræbus, with youthful hopes beguil'd,

Swol'n with success, and of a daring mind,

This new invention fatally design'd.

'My friends,' said he, 'since fortune shows the way,

'Tis fit we should the auspicious guide obey.

For what has she these Grecian arms bestowed,

But their destruction, and the Trojans' good?

Then change we shields, and their devices bear:

Let fraud supply the want of force in war.

They find us arms.'—This said, himself he dress'd

In dead Androgeos' spoils, his upper vest,

His painted buckler, and his plumy crest."

"Next Aventinus drives his chariot round

The Latian plains, with palms and laurels crown'd.

Proud of his steeds, he smokes along the field;

His father's hydra fills his ample shield;

A hundred serpents hiss about the brims;

The son of Hercules he justly seems,

By his broad shoulders and gigantic limbs."

"Fair Astur follows in the wat'ry field,

Proud of his manag'd horse, and painted shield.

Thou muse, the name of Cinyras renew,

And brave Cupavo follow'd but by few;

Whose helm confess'd the lineage of the man,

And bore, with wings display'd, a silver swan.

Love was the fault of his fam'd ancestry.

Whose forms and fortunes in his Ensigns fly."

"And to them is allowed the invention of three things, which have come into use among the Greeks:—For the Carians seem to be the first who put crests upon their helmets and sculptured devices upon their shields."

"Those who deny this statement assert that he (Sophanes) bare on his shield, as a device, an anchor."

"They relinquished the guard of the gates; and the Eagles and other Ensigns, which in the beginning of the Tumult they had thrown together, were now restored each to its distinct station."

Potter in his "Antiquities of Greece" (Dunbar's edition, Edinburgh, 1824, vol. ii. page 79), thus speaks of the ensigns or flags (σημεῖα) used by the Grecians in their military affairs: "Of these there were different sorts, several of which were adorned with images of animals, or other things bearing peculiar relations to the cities they belong to. The Athenians, for instance, bore an owl in their ensigns (Plutarchus Lysandro), as being sacred to Minerva, the protectress of their city; the Thebans a Sphynx (idem Pelopidas, Cornelius Nepos, Epaminondas), in memory of the famous monster overcome by Œdipus. The Persians paid divine honours to the sun, and therefore represented him in their ensigns" (Curtius, lib. 3). Again (in page 150), speaking of the ornaments and devices on their ships, he says: "Some other things there are in the prow and stern that deserve our notice, as those ornaments wherewith the extremities of the ship were beautified, commonly called ἀκρονεα (or νεῶν κορωνίδες), in Latin, Corymbi. The form of them sometimes represented helmets, sometimes living creatures, but most frequently was winded into a round compass, whence they are so commonly named Corymbi and Coronæ. To the ἀκροστόλια in the prow, answered the ἄφγαστα in the stern, which were often of an orbicular figure, or fashioned like wings, to which a little shield called ἀσπιδεῖον, or ἀσπιδίσκη, was frequently affixed; sometimes a piece of wood was erected, whereon ribbons of divers colours were hung, and served instead of a flag to distinguish the ship. Χηνίσκος was so called from Χὴν, a Goose, whose {10}figure it resembled, because geese were looked on as fortunate omens to mariners, for that they swim on the top of the waters and sink not. Παράσημον was the flag whereby ships were distinguished from one another; it was placed in the prow, just below the στόλος, being sometimes carved, and frequently painted, whence it is in Latin termed pictura, representing the form of a mountain, a tree, a flower, or any other thing, wherein it was distinguished from what was called tutela, or the safeguard of the ship, which always represented some one of the gods, to whose care and protection the ship was recommended; for which reason it was held sacred. Now and then we find the tutela taken for the Παράσημον, and perhaps sometimes the images of gods might be represented on the flags; by some it is placed also in the prow, but by most authors of credit assigned to the stern. Thus Ovid in his Epistle to Paris:—

'Accipit et pictos puppis adunca Deos.'

'The stern with painted deities richly shines.'

"The ship wherein Europa was conveyed from Phœnicia into Crete had a bull for its flag, and Jupiter for its tutelary deity. The Bœotian ships had for their tutelar god Cadmus, represented with a dragon in his hand, because he was the founder of Thebes, the principal city of Bœotia. The name of the ship was usually taken from the flag, as appears in the following passage of Ovid, where he tells us his ship received its name from the helmet painted upon it:—

'Est mihi, sitque, precor, flavæ tutela Minervæ,

Navis et à pictâ casside nomen habit.'

'Minerva is the goddess I adore,

And may she grant the blessings I implore;

The ship its name a painted helmet gives.'

"Hence comes the frequent mention of ships called Pegasi, Scyllæ, Bulls, Rams, Tigers, &c., which the poets took liberty to represent as living creatures that transported their riders from one country to another; nor was there (according to some) any other ground for those known fictions of Pegasus, the winged Bellerophon, or the Ram which is reported to have carried Phryxus to Colchos."

To quote another very learned author: "The system of hieroglyphics, or symbols, was adopted into every mysterious institution, for the purpose of concealing the most sublime secrets of religion from the prying curiosity of the vulgar; to whom nothing was exposed but the beauties of their morality." (See Ramsay's "Travels of Cyrus," lib. 3.) "The old Asiatic style, so highly figurative, seems, by what we find of {11}its remains in the prophetic language of the sacred writers, to have been evidently fashioned to the mode of the ancient hieroglyphics; for as in hieroglyphic writing the sun, moon, and stars were used to represent states and empires, kings, queens, and nobility—their eclipse and extinction, temporary disasters, or entire overthrow—fire and flood, desolation by war and famine; plants or animals, the qualities of particular persons, &c.; so, in like manner, the Holy Prophets call kings and empires by the names of the heavenly luminaries; their misfortunes and overthrow are represented by eclipses and extinction; stars falling from the firmament are employed to denote the destruction of the nobility; thunder and tempestuous winds, hostile invasions; lions, bears, leopards, goats, or high trees, leaders of armies, conquerors, and founders of empires; royal dignity is described by purple, or a crown; iniquity by spotted garments; a warrior by a sword or bow; a powerful man, by a gigantic stature; a judge by balance, weights, and measures—in a word, the prophetic style seems to be a speaking hieroglyphic."

It seems to me, however, that the whole of these are no more than symbolism, though they are undoubtedly symbolism of a high and methodical order, little removed from our own armory. Personally I do not consider them to be armory, but if the word is to be stretched to the utmost latitude to permit of their inclusion, one certain conclusion follows. That if the heraldry of that day had an orderly existence, it most certainly came absolutely to an end and disappeared. Armory as we know it, the armory of to-day, which as a system is traced back to the period of the Crusades, is no mere continuation by adoption. It is a distinct development and a re-development ab initio. Undoubtedly there is a period in the early development of European civilisation which is destitute alike of armory, or of anything of that nature. The civilisation of Europe is not the civilisation of Egypt, of Greece, or of Rome, nor a continuation thereof, but a new development, and though each of these in its turn attained a high degree of civilisation and may have separately developed a heraldic symbolism much akin to armory, as a natural consequence of its own development, as the armory we know is a development of its own consequent upon the rise of our own civilisation, nevertheless it is unjustifiable to attempt to establish continuity between the ordered symbolism of earlier but distinct civilisations, and our own present system of armory. The one and only civilisation which has preserved its continuity is that of the Jewish race. In spite of persecution the Jews have preserved unchanged the minutest details of ritual law and ceremony, the causes of their suffering. Had heraldry, which is and has always been a matter of pride, formed a part of their distinctive life we should find it still existing. Yet the fact remains {12}that no trace of Jewish heraldry can be found until modern times. Consequently I accept unquestioningly the conclusions of the late J. R. Planché, Somerset Herald, who unhesitatingly asserted that armory did not exist at the time of the Conquest, basing his conclusions principally upon the entire absence of armory from the seals of that period, and the Bayeux tapestry.

The family tokens (mon) of the Japanese, however, fulfil very nearly all of the essentials of armory, although considered heraldically they may appear somewhat peculiar to European eyes. Though perhaps never forming the entire decoration of a shield, they do appear upon weapons and armour, and are used most lavishly in the decoration of clothing, rooms, furniture, and in fact almost every conceivable object, being employed for decorative purposes in precisely the same manners and methods that armorial devices are decoratively made use of in this country. A Japanese of the upper classes always has his mon in three places upon his kimono, usually at the back just below the collar and on either sleeve. The Japanese servants also wear their service badge in much the same manner that in olden days the badge was worn by the servants of a nobleman. The design of the service badge occupies the whole available surface of the back, and is reproduced in a miniature form on each lappel of the kimono. Unfortunately, like armorial bearings in Europe, but to a far greater extent, the Japanese mon has been greatly pirated and abused. {13}

Fig. 1, "Kiku-non-hana-mon," formed from the conventionalised bloom (hana) of the chrysanthemum, is the mon of the State. It is formed of sixteen petals arranged in a circle, and connected on the outer edge by small curves.

Fig. 2, "Kiri-mon," is the personal mon of the Mikado, formed of the leaves and flower of the Paulowna imperialis, conventionally treated.

Fig. 3, "Awoï-mon," is the mon of the House of Minamoto Tokugawa, and is composed of three sea leaves (Asarum). The Tokugawa reigned over the country as Shogune from 1603 until the last revolution in 1867, before which time the Emperor (the Mikado) was only nominally the ruler.

Fig. 4 shows the mon of the House of Minamoto Ashikaya, which from 1336 until 1573 enjoyed the Shogunat.

Fig. 5 shows the second mon of the House of Arina, Toymote, which is used, however, throughout Japan as a sign of luck.

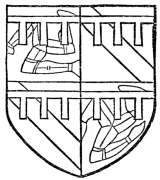

The Saracens and the Moors, to whom we owe the origin of so many of our recognised heraldic charges and the derivation of some of our terms (e.g. "gules," from the Persian gul, and "azure" from the Persian lazurd) had evidently on their part something more than the rudiments of armory, as Figs. 6 to 11 will indicate. {14}

One of the best definitions of a coat of arms that I know, though this is not perfect, requires the twofold qualification that the design must be hereditary and must be connected with armour. And there can be no doubt that the theory of armory as we now know it is governed by those two ideas. The shields and the crests, if any decoration of a helmet is to be called a crest, of the Greeks and the Romans undoubtedly come within the one requirement. Also were they indicative of and perhaps intended to be symbolical of the owner. They lacked, however, heredity, and we have no proof that the badges we read of, or the decorations of shield and helmet, were continuous even during a single lifetime. Certainly as we now understand the term there must be both continuity of use, if the arms be impersonal, or heredity if the arms be personal. Likewise must there be their use as decorations of the implements of warfare.

If we exact these qualifications as essential, armory as a fact and as a science is a product of later days, and is the evolution from the idea of tribal badges and tribal means and methods of honour applied to the decoration of implements of warfare. It is the conjunction and association of these two distinct ideas to which is added the no less important idea of heredity. The civilisation of England before the Conquest has left us no trace of any sort or kind that the Saxons, the Danes, or the Celts either knew or practised armory. So that if armory as we know it is to be traced to the period of the Norman Conquest, we must look for it as an adjunct of the altered civilisation and the altered law which Duke William brought into this country. Such evidence as exists is to the contrary, and there is nothing that can be truly termed armorial in that marvellous piece of cotemporaneous workmanship known as the Bayeux tapestry.

Concerning the Bayeux tapestry and the evidence it affords, Woodward and Burnett's "Treatise on Heraldry," apparently following Planché's conclusions, remarks: "The evidence afforded by the famous tapestry preserved in the public library of Bayeux, a series of views in sewed work representing the invasion and conquest of England by William the Norman, has been appealed to on both sides of this controversy, and has certainly an important bearing on the question of the antiquity of coat-armour. This panorama of seventy-two scenes is on probable grounds believed to have been the work of the Conqueror's Queen Matilda and her maidens; though the French historian Thierry and others ascribe it to the Empress Maud, daughter of Henry III. The latest authorities suggest the likelihood of its having been wrought as a decoration for the Cathedral of Bayeux, when rebuilt by William's uterine brother Odo, Bishop of that See, in 1077. The exact correspondence which has been discovered between the length of the tapestry {15}and the inner circumference of the nave of the cathedral greatly favours this supposition. This remarkable work of art, as carefully drawn in colour in 1818 by Mr. C. Stothard, is reproduced in the sixth volume of the Vetusta Monumenta; and more recently an excellent copy of it from autotype plates has been published by the Arundel Society. Each of its scenes is accompanied by a Latin description, the whole uniting into a graphic history of the event commemorated. We see Harold taking leave of Edward the Confessor; riding to Bosham with his hawk and hounds; embarking for France; landing there and being captured by the Count of Ponthieu; redeemed by William of Normandy, and in the midst of his Court aiding him against Conan, Count of Bretagne; swearing on the sacred relics to recognise William's claim of succession to the English throne, and then re-embarking for England. On his return, we have him recounting the incidents of his journey to Edward the Confessor, to whose funeral obsequies we are next introduced. Then we have Harold receiving the crown from the English people, and ascending the throne; and William, apprised of what had taken place, consulting with his half-brother Odo about invading England. The war preparations of the Normans, their embarkation, their landing, their march to Hastings, and formation of a camp there, form the subjects of successive scenes; and finally we have the battle of Hastings, with the death of Harold and the flight of the English. In this remarkable piece of work we have figures of more than six hundred persons, and seven hundred animals, besides thirty-seven buildings, and forty-one ships or boats. There are of course also numerous shields of warriors, of which some are round, others kite-shaped, and on some of the latter are rude figures, of dragons or other imaginary animals, as well as crosses of different forms, and spots. On one hand it requires little imagination to find the cross patée and the cross botonnée of heraldry prefigured on two of these shields. But there are several fatal objections to regarding these figures as incipient armory, namely that while the most prominent persons of the time are depicted, most of them repeatedly, none of these is ever represented twice as bearing the same device, nor is there one instance of any resemblance in the rude designs described to the bearings actually used by the descendants of the persons in question. If a personage so important and so often depicted as the Conqueror had borne arms, they could not fail to have had a place in a nearly contemporary work, and more especially if it proceeded from the needle of his wife."

Lower, in his "Curiosities of Heraldry," clinches the argument when he writes: "Nothing but disappointment awaits the curious armorist who seeks in this venerable memorial the pale, the bend, and {16}other early elements of arms. As these would have been much more easily imitated with the needle than the grotesque figures before alluded to, we may safely conclude that personal arms had not yet been introduced." The "Treatise on Heraldry" proceeds: "The Second Crusade took place in 1147; and in Montfaucon's plates of the no longer extant windows of the Abbey of St. Denis, representing that historical episode, there is not a trace of an armorial ensign on any of the shields. That window was probably executed at a date when the memory of that event was fresh; but in Montfaucon's time, the beginning of the eighteenth century, the Science héroïque was matter of such moment in France that it is not to be believed that the armorial figures on the shields, had there been any, would have been left out."

Surely, if anywhere, we might have expected to have found evidence of armory, if it had then existed, in the Bayeux Tapestry. Neither do the seals nor the coins of the period produce a shield of arms. Nor amongst the host of records and documents which have been preserved to us do we find any reference to armorial bearings. The intense value and estimation attached to arms in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, which has steadily though slowly declined since that period, would lead one to suppose that had arms existed as we know them at an earlier period, we should have found some definite record of them in the older chronicles. There are no such references, and no coat of arms in use at a later date can be relegated to the Conquest or any anterior period. Of arms, as we know them, there are isolated examples in the early part of the twelfth century, perhaps also at the end of the eleventh. At the period of the Third Crusade (1189) they were in actual existence as hereditary decorations of weapons of warfare.

Luckily, for the purposes of deductive reasoning, human nature remains much the same throughout the ages, and, dislike it as we may, vanity now and vanity in olden days was a great lever in the determination of human actions. A noticeable result of civilisation is the effort to suppress any sign of natural emotion; and if the human race at the present day is not unmoved by a desire to render its appearance attractive, we may rest very certainly assured that in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries this motive was even more pronounced, and still yet more pronounced at a more remote distance of time. Given an opportunity of ornament, there you will find ornament and decoration. The ancient Britons, like the Maories of to-day, found their opportunities restricted to their skins. The Maories tattoo themselves in intricate patterns, the ancient Britons used woad, though history is silent as to whether they were content with flat colour or gave their preference to patterns. It is unnecessary to trace the art of {17}decoration through embroidery upon clothes, but there is no doubt that as soon as shields came into use they were painted and decorated, though I hesitate to follow practically the whole of heraldic writers in the statement that it was the necessity for distinction in battle which accounted for the decoration of shields. Shields were painted and decorated, and helmets were adorned with all sorts of ornament, long before the closed helmet made it impossible to recognise a man by his facial peculiarities and distinctions. We have then this underlying principle of vanity, with its concomitant result of personal decoration and adornment. We have the relics of savagery which caused a man to be nicknamed from some animal. The conjunction of the two produces the effort to apply the opportunity for decoration and the vanity of the animal nickname to each other.

We are fast approaching armory. In those days every man fought, and his weapons were the most cherished of his personal possessions. The sword his father fought with, the shield his father carried, the banner his father followed would naturally be amongst the articles a son would be most eager to possess. Herein are the rudiments of the idea of heredity in armory; and the science of armory as we know it begins to slowly evolve itself from that point, for the son would naturally take a pride in upholding the fame which had clustered round the pictured signs and emblems under which his father had warred.

Another element then appeared which exercised a vast influence upon armory. Europe rang from end to end with the call to the Crusades. We may or we may not understand the fanaticism which gripped the whole of the Christian world and sent it forth to fight the Saracens. That has little to do with it. The result was the collection together in a comparatively restricted space of all that was best and noblest amongst the human race at that time. And the spirit of emulation caused nation to vie with nation, and individual with individual in the performance of illustrious feats of honour. War was elevated to the dignity of a sacred duty, and the implements of warfare rose in estimation. It is easy to understand the glory therefore that attached to arms, and the slow evolution which I have been endeavouring to indicate became a concrete fact, and it is due to the Crusades that the origin of armory as we now know it was practically coeval throughout Europe, and also that a large proportion of the charges and terms and rules of heraldry are identical in all European countries.

The next dominating influence was the introduction, in the early part of the thirteenth century, of the closed helmet. This hid the face of the wearer from his followers and necessitated some means by which the latter could identify the man under whom they served. What more natural than that they should identify him by the {18}decoration of his shield and the ornaments of his helmet, and by the coat or surcoat which he wore over his coat of mail?

This surcoat had afforded another opportunity of decoration, and it had been decorated with the same signs that the wearer had painted on his shield, hence the term "coat of arms." This textile coat was in itself a product of the Crusades. The Crusaders went in their metal armour from the cooler atmospheres of Europe to the intolerable heat of the East. The surcoat and the lambrequin alike protected the metal armour and the metal helmet from the rays of the sun and the resulting discomfort to the wearer, and were also found very effective as a preventative of the rust resulting from rain and damp upon the metal. By the time that the closed helmet had developed the necessity of distinction and the identification of a man with the pictured signs he wore or carried, the evolution of armory into the science we know was practically complete. {19}

It would be foolish and misleading to assert that the possession of a coat of arms at the present date has anything approaching the dignity which attached to it in the days of long ago; but one must trace this through the centuries which have passed in order to form a true estimate of it, and also to properly appreciate a coat of arms at the present time. It is necessary to go back to the Norman Conquest and the broad dividing lines of social life in order to obtain a correct knowledge. The Saxons had no armory, though they had a very perfect civilisation. This civilisation William the Conqueror upset, introducing in its place the system of feudal tenure with which he had been familiar on the Continent. Briefly, this feudal system may be described as the partition of the land amongst the barons, earls, and others, in return for which, according to the land they held, they accepted a liability of military service for themselves and so many followers. These barons and earls in their turn sublet the land on terms advantageous to themselves, but nevertheless requiring from those to whom they sublet the same military service which the King had exacted from themselves proportionate with the extent of the sublet lands. Other subdivisions took place, but always with the same liability of military service, until we come to those actually holding and using the lands, enjoying them subject to the liability of military service attached to those particular lands. Every man who held land under these conditions—and it was impossible to hold land without them—was of the upper class. He was nobilis or known, and of a rank distinct, apart, and absolutely separate from the remainder of the population, who were at one time actually serfs, and for long enough afterwards, of no higher social position than they had enjoyed in their period of servitude. This wide distinction between the upper and lower classes, which existed from one end of Europe to the other, was the very root and foundation of armory. It cannot be too greatly insisted upon. There were two qualitative terms, "gentle" and "simple," which were applied to the upper and lower classes respectively. Though now becoming archaic and obsolete, the terms "gentle" and "simple" {20}are still occasionally to be met with used in that original sense; and the two adjectives "gentle" and "simple," in the everyday meanings of the words, are derived from, and are a later growth from the original usage with the meaning of the upper and lower classes; because the quality of being gentle was supposed to exist in that class of life referred to as gentle, whilst the quality of simplicity was supposed to be an attribute of the lower class. The word gentle is derived from the Latin word gens (gentilis), meaning a man, because those were men who were not serfs. Serfs and slaves were nothing accounted of. The word "gentleman" is a derivative of the word gentle, and a gentleman was a member of the gentle or upper class, and gentle qualities were so termed because they were the qualities supposed to belong to the gentle class. A man was not a gentleman, even in those days, because he happened to possess personal qualities usually associated with the gentle class; a man was a gentleman if he belonged to the gentle or upper class and not otherwise, so that "gentleman" was an identical term for one to whom the word nobilis was applied, both being names for members of the upper class. To all intents and purposes at that date there was no middle class at all. The kingdom was the land; and the trading community who dwelt in the towns were of little account save as milch kine for the purposes of taxation. The social position conceded to them by the upper class was little, if any, more than was conceded to the lower classes, whose life and liberties were held very cheaply. Briefly to sum up, therefore, there were but the two classes in existence, of which the upper class were those who held the land, who had military obligations, and who were noble, or in other words gentle. Therefore all who held land were gentlemen; because they held land they had to lead their servants and followers into battle, and they themselves were personally responsible for the appearance of so many followers, when the King summoned them to war. Now we have seen in the previous chapter that arms became necessary to the leader that his followers might distinguish him in battle. Consequently all who held land having, because of that land, to be responsible for followers in battle, found it necessary to use arms. The corollary is therefore evident, that all who held lands of the King were gentlemen or noble, and used arms; and as a consequence all who possessed arms were gentlemen, for they would not need or use arms, nor was their armour of a character upon which they could display arms, unless they were leaders. The leaders, we have seen, were the land-owning or upper class; therefore every one who had arms was a gentleman, and every gentleman had arms. But the status of gentlemen existed before there were coats of arms, and the later inseparable connection between the two was an evolution.

The preposterous prostitution of the word gentleman in these latter {21}days is due to the almost universal attribute of human nature which declines to admit itself as of other than gentle rank; and in the eager desire to write itself gentleman, it has deliberately accepted and ordained a meaning to the word which it did not formerly possess, and has attributed to it and allowed it only such a definition as would enable almost anybody to be included within its ranks.

The word gentleman nowadays has become meaningless as a word in an ordinary vocabulary; and to use the word with its original and true meaning, it is necessary to now consider it as purely a technical term. We are so accustomed to employ the word nowadays in its unrestricted usage that we are apt to overlook the fact that such a usage is comparatively modern. The following extract from "The Right to Bear Arms" will prove that its real meaning was understood and was decided by law so late as the seventeenth century to be "a man entitled to bear arms":—

"The following case in the Earl Marshal's Court, which hung upon the definition of the word, conclusively proves my contention:—

"'21st November 1637.—W. Baker, gent., humbly sheweth that having some occasion of conference with Adam Spencer of Broughton under the Bleane, co. Cant., on or about 28th July last, the said Adam did in most base and opprobrious tearmes abuse your petitioner, calling him a base, lying fellow, &c. &c. The defendant pleaded that Baker is noe Gentleman, and soe not capable of redresse in this court. Le Neve, Clarenceux, is directed to examine the point raised, and having done so, declared as touching the gentry of William Baker, that Robert Cooke, Clarenceux King of Arms, did make a declaration 10th May 1573, under his hand and seale of office, that George Baker of London, sonne of J. Baker of the same place, sonne of Simon Baker of Feversham, co. Cant., was a bearer of tokens of honour, and did allow and confirm to the said George Baker and to his posterity, and to the posterity of Christopher Baker, these Arms, &c. &c. And further, Le Neve has received proof that the petitioner, William Baker, is the son of William Baker of Kingsdowne, co. Cant., who was the brother of George Baker, and son of Christopher aforesaid.' The judgment is not stated. (The original Confirmation of Arms by Cooke, 10th May 1573, may now be seen in the British Museum.—Genealogist for 1889, p. 242.)"

It has been shown that originally practically all who held land bore arms. It has also been shown that armory was an evolution, and as a consequence it did not start, in this country at any rate, as a ready-made science with all its rules and laws completely known or promulgated. There is not the slightest doubt that, in the earliest infancy of the science, arms were assumed and chosen without the control of the Crown; and one would not be far wrong in assuming that, so long as the rights accruing from prior appropriation of other people were respected, a landowner finding the necessity of arms in battle, was originally at liberty to assume what arms he liked.

That period, however, was of but brief duration, for we find as early {22}as 1390, from the celebrated Scrope and Grosvenor case, (1) that a man could have obtained at that time a definite right to his arms, (2) that this right could be enforced against another, and we find, what is more important, (3) that the Crown and the Sovereign had supreme control and jurisdiction over arms, and (4) that the Sovereign could and did grant arms. From that date down to the present time the Crown, both by its own direct action and by the action of the Kings of Arms to whom it delegates powers for the purpose, in Letters Patent under the Great Seal, specifically issued to each separate King of Arms upon his appointment, has continued to grant armorial bearings. Some number of early grants of arms direct from the Crown have been printed in the Genealogical Magazine, and some of the earliest distinctly recite that the recipients are made noble and created gentlemen, and that the arms are given them as the sign of their nobility. The class of persons to whom grants of arms were made in the earliest days of such instruments is much the same as the class which obtain grants of arms at the present day, and the successful trader or merchant is now at liberty, as he was in the reign of Henry VIII. and earlier, to raise himself to the rank of a gentleman by obtaining a grant of arms. A family must make its start at some time or other; let this start be made honestly, and not by the appropriation of the arms of some other man.

The illegal assumption of arms began at an early date; and in spite of the efforts of the Crown, which have been more or less continuous and repeated, it has been found that the use of "other people's" arms has continued. In the reign of Henry V. a very stringent proclamation was issued on the subject; and in the reigns of Queen Elizabeth and her successors, the Kings of Arms were commanded to make perambulations throughout the country for the purpose of pulling down and defacing improper arms, of recording arms properly borne by authority, and of compelling those who used arms without authority to obtain authority for them or discontinue their use. These perambulations were termed Visitations. The subject of Visitations, and in fact the whole subject of the right to bear arms, is dealt with at length in the book to which reference has been already made, namely, "The Right to Bear Arms."

The glory of a descent from a long line of armigerous ancestors, the glory and the pride of race inseparably interwoven with the inheritance of a name which has been famous in history, the fact that some arms have been designed to commemorate heroic achievements, the fact that the display of a particular coat of arms has been the method, which society has countenanced, of advertising to the world that one is of the upper class or a descendant of some ancestor who performed some glorious deed to which the arms have reference, the fact that arms themselves are the very sign of a particular descent or of a particular {23}rank, have all tended to cause a false and fictitious value to be placed upon all these pictured emblems which as a whole they have never possessed, and which I believe they were never intended to possess. It is because they were the prerogative and the sign of aristocracy that they have been coveted so greatly, and consequently so often assumed improperly. Now aristocracy and social position are largely a matter of personal assertion. A man assumes and asserts for himself a certain position, which position is gradually and imperceptibly but continuously increased and elevated as its assertion is reiterated. There is no particular moment in a man's life at the present time, the era of the great middle class, at which he visibly steps from a plebeian to a patrician standing. And when he has fought and talked the world into conceding him a recognised position in the upper classes, he naturally tries to obliterate the fact that he or "his people" were ever of any other social position, and he hesitates to perpetually date his elevation to the rank of gentility by obtaining a grant of arms and thereby admitting that before that date he and his people were plebeian. Consequently he waits until some circumstance compels an application for a grant, and the consequence is that he thereby post-dates his actual technical gentility to a period long subsequent to the recognition by Society of his position in the upper classes.

Arms are the sign of the technical rank of gentility. The possession of arms is a matter of hereditary privilege, which privilege the Crown is willing should be obtained upon certain terms by any who care to possess it, who live according to the style and custom which is usual amongst gentle people. And so long as the possession of arms is a matter of privilege, even though this privilege is no greater than is consequent upon payment of certain fees to the Crown and its officers; for so long will that privilege possess a certain prestige and value, though this may not be very great. Arms have never possessed any greater value than attaches to a matter of privilege; and (with singularly few exceptions) in every case, be it of a peer or baronet, of knight or of simple gentleman, this privilege has been obtained or has been regularised by the payment at some time or other of fees to the Crown and its officers. And the only difference between arms granted and paid for yesterday and arms granted and paid for five hundred years ago is the simple moral difference which attaches to the dates at which the payments were made.

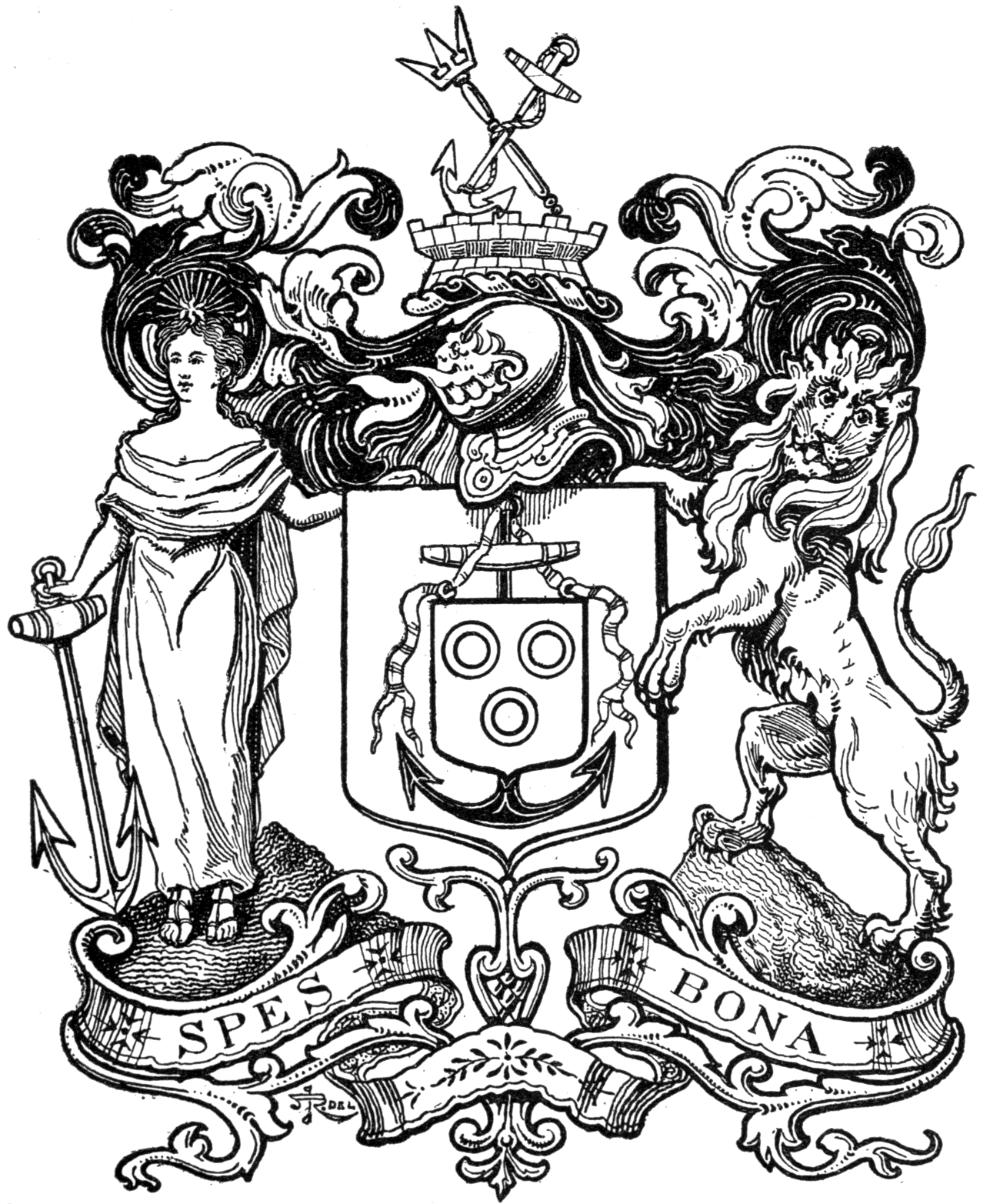

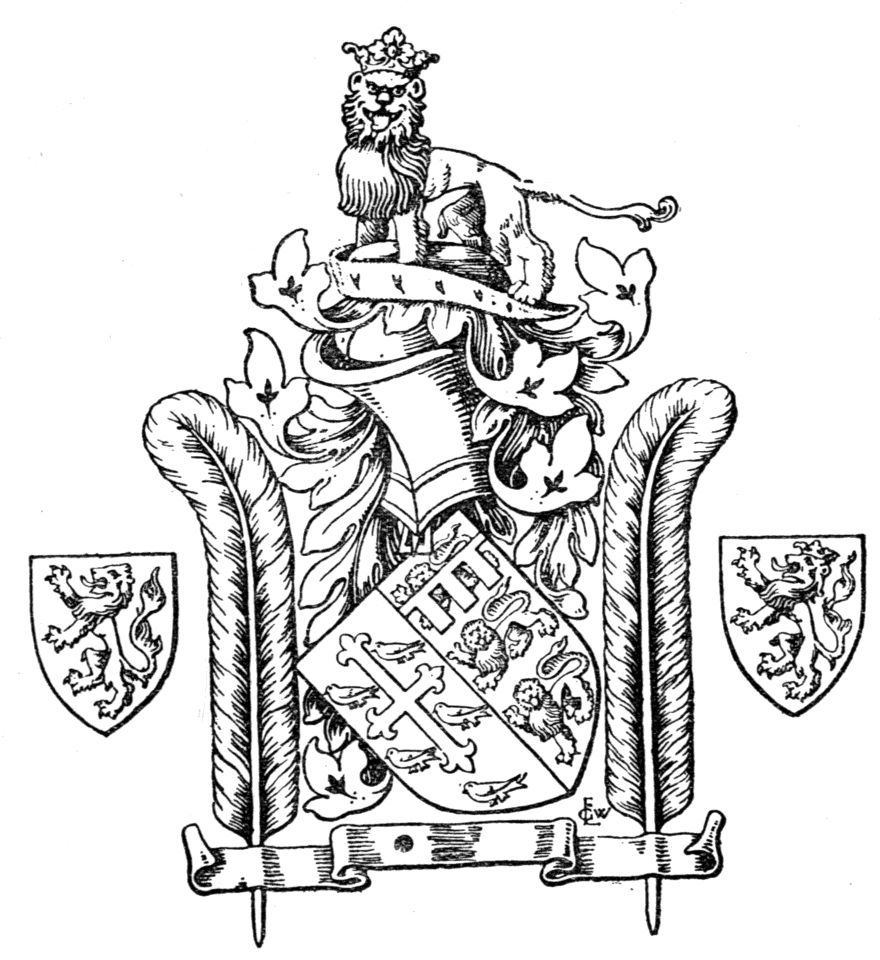

Gentility is merely hereditary rank, emanating, with all other rank, from the Crown, the sole fountain of honour. It is idle to make the word carry a host of meanings it was never intended to. Arms being the sign of the technical rank of gentility, the use of arms is the advertisement of one's claim to that gentility. Arms mean nothing more. By {24}coronet, supporters, and helmet can be indicated one's place in the scale of precedence; by adding arms for your wife you assert that she also is of gentle rank; your quarterings show the other gentle families you represent; difference marks will show your position in your own family (not a very important matter); augmentations indicate the deeds of your ancestors which the Sovereign thought worthy of being held in especial remembrance. By the use of a certain coat of arms, you assert your descent from the person to whom those arms were granted, confirmed, or allowed. That is the beginning and end of armory. Why seek to make it mean more?

However heraldry is looked upon, it must be admitted that from its earliest infancy armory possessed two essential qualities. It was the definite sign of hereditary nobility and rank, and it was practically an integral part of warfare; but also from its earliest infancy it formed a means of decoration. It would be a rash statement to assert that armory has lost its actual military character even now, but it certainly possessed it undiminished so long as tournaments took place, for the armory of the tournament was of a much higher standard than the armory of the battlefield. Armory as an actual part of warfare existed as a means of decoration for the implements of warfare, and as such it certainly continues in some slight degree to the present day.

Armory in that bygone age, although it existed as the symbol of the lowest hereditary rank, was worn and used in warfare, for purposes of pageantry, for the indication of ownership, for decorative purposes, for the needs of authenticity in seals, and for the purposes of memorials in records, pedigrees, and monuments. All those uses and purposes of armory can be traced back to a period coeval with that to which our certain knowledge of the existence of armory runs. Of all those usages and purposes, one only, that of the use of armorial bearings in actual battle, can be said to have come to an end, and even that not entirely so; the rest are still with us in actual and extensive existence. I am not versed in the minutiæ of army matters or army history, but I think I am correct in saying that there was no such thing as a regular standing army or a national army until the reign of Henry VIII. Prior to that time the methods of the feudal system supplied the wants of the country. The actual troops were in the employment, not of the Crown, but of the individual leaders. The Sovereign called upon, and had the right to call upon, those leaders to provide troops; but as those troops were not in the direct employment of the Crown, they wore the liveries and heraldic devices of their leaders. The leaders wore their own devices, originally for decorative reasons, and later that they might be distinguished by their particular followers: hence the actual use in battle in former days of private armorial bearings. And even yet the {25}practice is not wholly extinguished, for the tartans of the Gordon and Cameron Highlanders are a relic of the usages of these former days. With the formation of a standing army, and the direct service of the troops to the Crown, the liveries and badges of those who had formerly been responsible for the troops gave way to the liveries and badges of the Crown. The uniform of the Beefeaters is a good example of the method in which in the old days a servant wore the badge and livery of his lord. The Beefeaters wear the scarlet livery of the Sovereign, and wear the badge of the Sovereign still. Many people will tell you, by the way, that the uniform of a Beefeater is identical now with what it was in the days of Henry VIII. It isn't. In accordance with the strictest laws of armory, the badge, embroidered on the front and back of the tunic, has changed, and is now the triple badge—the rose, the thistle, and the shamrock—of the triple kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Every soldier who wears a scarlet coat, the livery of his Sovereign, every regiment that carries its colours, every saddle-cloth with a Royal emblem thereupon, is evidence that the use of armory in battle still exists in a small degree to the present day; but circumstances have altered. The troops no longer attack to the cry of "A Warwick! a Warwick!" they serve His Majesty the King and wear his livery and devices. They no longer carry the banner of their officer, whose servants and tenants they would formerly have been; the regiment cherishes instead the banner of the armorial bearings of His Majesty. Within the last few years, probably within the lifetime of all my readers, there has been striking evidence of the manner in which circumstances alter everything. The Zulu War put an end to the practice of taking the colours of a regiment into battle; the South African War saw khaki substituted universally for the scarlet livery of His Majesty; and to have found upon a South African battlefield the last remnant of the armorial practices of the days of chivalry, one would have needed, I am afraid, to examine the buttons of the troopers. Still the scarlet coat exists in the army on parade: the Life Guards wear the Royal Cross of St. George and the Star of the Garter, the Scots Greys have the Royal Saltire of St. Andrew, and the Gordon Highlanders have the Gordon crest of the Duke of Richmond and Gordon; and there are many other similar instances.

There is yet another point. The band of a regiment is maintained by the officers of the regiment, and at the present day in the Scottish regiments the pipers have attached to their pipes banners bearing the various personal armorial bearings of the officers of the regiment. So that perhaps one is justified in saying that the use of armorial bearings in warfare has not yet come to an end. The other ancient usages of armory exist now as they existed in the earliest times. So that it is {26}foolish to contend that armory has ceased to exist, save as an interesting survival of the past. It is a living reality, more widely in use at the present day than ever before.

Certainly the military side of armory has sunk in importance till it is now utterly overshadowed by the decorative, but the fact that armory still exists as the sign and adjunct of hereditary rank utterly forbids one to assert that armory is dead, and though this side of armory is also now partly overshadowed by its decorative use, armory must be admitted to be still alive whilst its laws can still be altered. When, if ever, rank is finally swept away, and when the Crown ceases to grant arms, and people cease to use them, then armory will be dead, and can be treated as the study of a dead science. {27}

The crown is the Fountain of Honour, having supreme control of coat-armour. This control in all civilised countries is one of the appanages of sovereignty, but from an early period much of the actual control has been delegated to the Heralds and Kings of Arms. The word Herald is derived from the Anglo-Saxon—here, an army, and wald, strength or sway—though it has probably come to us from the German word Herold.

In the last years of the twelfth century there appeared at festal gatherings persons mostly habited in richly coloured clothing, who delivered invitations to the guests, and, side by side with the stewards, superintended the festivities. Many of them were minstrels, who, after tournaments or battle, extolled the deeds of the victors. These individuals were known in Germany as Garzune.

Originally every powerful leader had his own herald, and the dual character of minstrel and messenger led the herald to recount the deeds of his master, and, as a natural consequence, of his master's ancestors. In token of their office they wore the coats of arms of the leaders they served; and the original status of a herald was that of a non-combatant messenger. When tournaments came into vogue it was natural that some one should examine the arms of those taking part, and from this the duties of the herald came to include a knowledge of coat-armour. As the Sovereign assumed or arrogated the control of arms, the right to grant arms, and the right of judgment in disputes concerning arms, it was but the natural result that the personal heralds of the Sovereign should be required to have a knowledge of the arms of his principal subjects, and should obtain something in the nature of a cognisance or control and jurisdiction over those arms; for doubtless the actions of the Sovereign would often depend upon the knowledge of his heralds.

The process of development in this country will be more easily understood when it is remembered that the Marshal or Earl Marshal was in former times, with the Lord High Constable, the first in military rank under the King, who usually led his army in person, and to {28}the Marshal was deputed the ordering and arrangement of the various bodies of troops, regiments, bands of retainers, &c., which ordering was at first facilitated and at length entirely determined by the use of various pictorial ensigns, such as standards, banners, crests, cognisances, and badges. The due arrangement and knowledge of these various ensigns became first the necessary study and then the ordinary duty of these officers of the Marshal, and their possession of such knowledge, which soon in due course had to be written down and tabulated, secured to them an important part in mediæval life. The result was that at an early period we find them employed in semi-diplomatic missions, such as carrying on negotiations between contending armies on the field, bearing declarations of war, challenges from one sovereign to another, besides arranging the ceremonial not only of battles and tournaments, but also of coronations, Royal baptisms, marriages, and funerals.

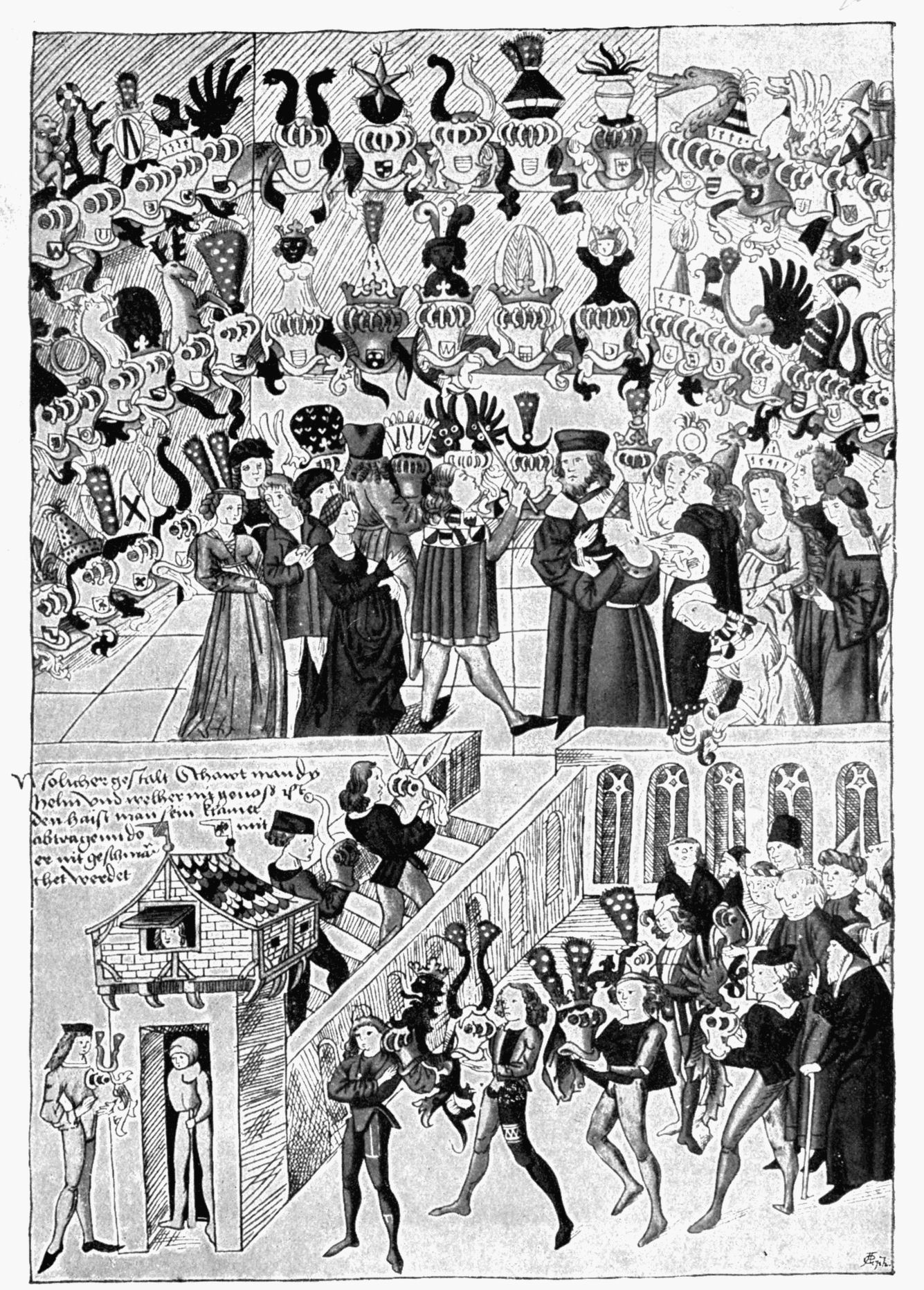

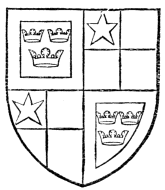

From the fact that neither King of Arms nor Herald is mentioned as officiating in the celebrated Scrope and Grosvenor case, of which very full particulars have come down to us, it is evident that the control of arms had not passed either in fact or in theory from the Crown to the officers of arms at that date. Konrad Grünenberg, in his Wappencodex ("Roll of Arms"), the date of which is 1483, gives a representation of a helmschau (literally helmet-show), here reproduced (Fig. 12), which includes the figure of a herald. Long before that date, however, the position of a herald in England was well defined, for we find that on January 5, 1420, the King appointed William Bruges to be Garter King of Arms. It is usually considered in England that it would be found that in Germany armory reached its highest point of evolution. Certainly German heraldic art is in advance of our own, and it is curious to read in the latest and one of the best of German heraldic books that "from the very earliest times heraldry was carried to a higher degree of perfection and thoroughness in England than elsewhere, and that it has maintained itself at the same level until the present day. In other countries, for the most part, heralds no longer have any existence but in name." The initial figure which appears at the commencement of Chapter I. represents John Smert, Garter King of Arms, and is taken from the grant of arms issued by him to the Tallow Chandlers' Company of London, which is dated September 24, 1456.

Long before there was any College of Arms, the Marshal, afterwards the Earl Marshal, had been appointed. The Earl Marshal is now head of the College of Arms, and to him has been delegated the whole of the control both of armory and of the College, with the exception of that part which the Crown has retained in its own hands. {29}After the Earl Marshal come the Kings of Arms, the Heralds of Arms, and the Pursuivants of Arms.

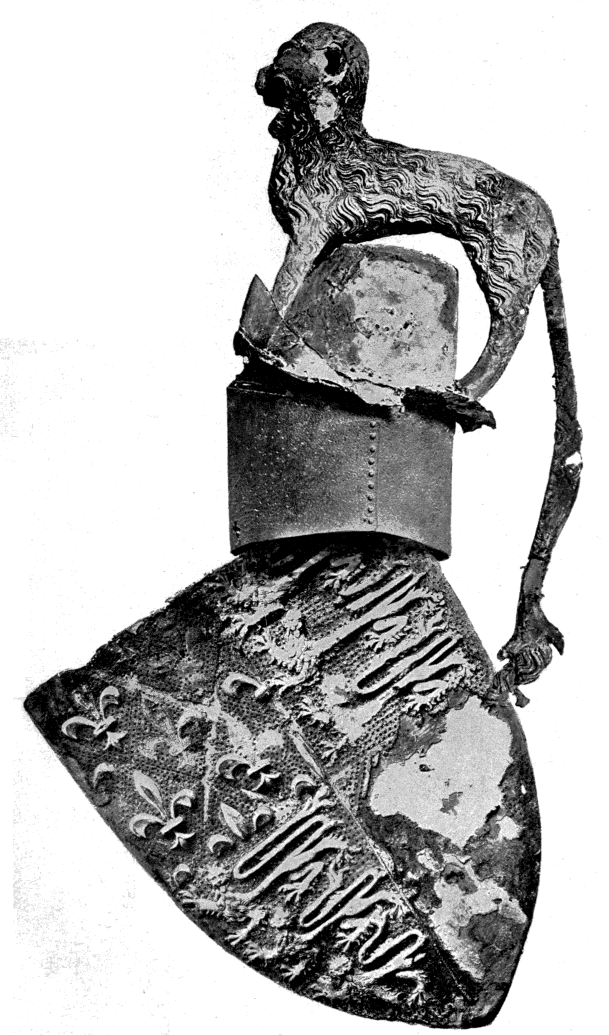

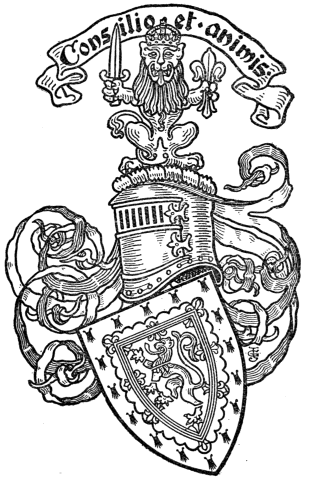

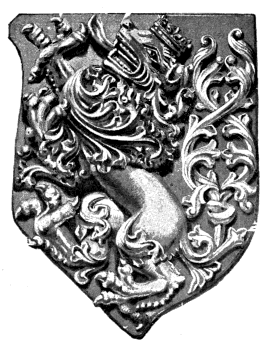

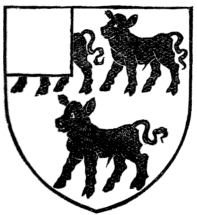

Fig. 12.—Helmschau or Helmet-Show. (From Konrad Grünenberg's Wappencodex zu München.) End of fifteenth century.