| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Core Historical Literature of Agriculture (CHLA), Albert R. Mann Library, Cornell University, see http://chla.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=chla;idno=3139668, and Internet Archive/American Libraries, see http://archive.org/details/cyrushallmccormi00cass. |

Transcriber's note: On some devices, clicking illustrations with blue borders will display larger, more detailed versions.

CYRUS HALL McCORMICK

HIS LIFE AND WORK

BY

HERBERT N. CASSON

Author of

"The Romance of Steel," "The Romance of the Reaper," etc.

ILLUSTRATED

CHICAGO

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1909

Copyright

A. C. McCLURG & Co.

1909

Published October, 1909

Entered at Stationers' Hall, London, England

The Lakeside Press

R. R. DONNELLEY & SONS COMPANY

CHICAGO

WHOEVER wishes to understand the making of the United States must read the life of Cyrus Hall McCormick. No other one man so truly represented the dawn of the industrial era,—the grapple of the pioneer with the crudities of a new country, the replacing of muscle with machinery, and the establishment of better ways and better times in farm and city alike. Beginning exactly one hundred years ago, the life of McCormick spanned the heroic period of our industrial advancement, when great things were done by great individuals. To know McCormick is to know what type of man it was who created the United States of the nineteenth century. And now that a new century has arrived, with a new type of business development, it may be especially instructive to review a life that was so structural and so fundamental.

As Professor Simon Newcomb has observed, "It is impressive to think how few men we should have had to remove from the earth during the[vi] past three centuries to have stopped the advance of our civilization." From this point of view, there are few, if any, who will appear to be more indispensable than McCormick. He was not brilliant. He was not picturesque. He was no caterer for fame or favor. But he was as necessary as bread. He fed his country as truly as Washington created it and Lincoln preserved it. He abolished our agricultural peasantry so effectively that we have had to import our muscle from foreign countries ever since. And he added an immense province to the new empire of mind over matter, the expansion of which has been and is now the highest and most important of all human endeavors.

As the master builder of the modern business of manufacturing farm machinery, McCormick set in motion so many forces of human betterment that the fruitfulness of his life can never be fully told. There are to-day in all countries more than one hundred thousand patents for inventions that were meant to lighten the labor of the farmer. And the cereal crop of the[vii] world has risen with incredible gains, until this year its value will be not far from ten thousand millions of dollars,—very nearly the equivalent of all the gold in coin and jewelry and bullion.

So, if there is not power and fascination in this story, it will be the fault of the story-teller, and not of his theme. The story itself is destined to be told and retold. It cannot be forgotten, because it is one of those rare life-histories that blazon out the peculiar genius of the nation under the stress of a new experience. As it is passed on from generation to generation, it may finally be polished into an Epic of the Wheat,—the tale of Man's long wrestle with Famine, and how he won at last by creating a world-wide system for the production and distribution of the Bread.

H. N. C.

Chicago, September 1, 1909.

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | The World's Need of a Reaper | 1 |

| II. | The McCormick Home | 13 |

| III. | The Invention of the Reaper | 26 |

| IV. | Sixteen Years of Pioneering | 48 |

| V. | The Building of the Reaper Business | 68 |

| VI. | The Struggle To Protect Patents | 91 |

| VII. | The Evolution of the Reaper | 105 |

| VIII. | The Conquest of Europe | 123 |

| IX. | McCormick as a Manufacturer | 139 |

| X. | Cyrus H. McCormick As a Man | 154 |

| XI. | The Reaper and the Nation | 188 |

| XII. | The Reaper and the World | 203 |

| XIII. | Give Us This Day Our Daily Bread | 234 |

| Index | 249 |

| Page | |

| Portrait of Cyrus Hall McCormick | Frontispiece |

| Old Blacksmith Shop on Walnut Grove Farm, Virginia | 14 |

| The Old McCormick Homestead, Walnut Grove Farm, Rockbridge County, Virginia | 18 |

| Portrait of Robert McCormick | 22 |

| Portrait of Mrs. Mary Ann Hall McCormick | 24 |

| New Providence Church, Rockbridge County, Virginia | 28 |

| Facsimiles from Manuscript by Mr. McCormick, Giving his Own Account of the Origin of the Reaper | 30 |

| First Practical Reaping Machine | 34 |

| The Field on which the First McCormick Reaper was Tried, Walnut Grove Farm, Virginia | 38 |

| Interior of Blacksmith Shop in which C. H. McCormick Built his First Reaper | 42 |

| Reaping with Crude Knives in India | 50 |

| Reaping with Sickles in Algeria | 56 |

| Reaping with Cradles in Illinois | 60 |

| An Early Advertisement for McCormick's Patent Virginia Reaper | 64 |

| The McCormick Reaper of 1847, on which Seats were Placed for the Driver and the Raker | 70 |

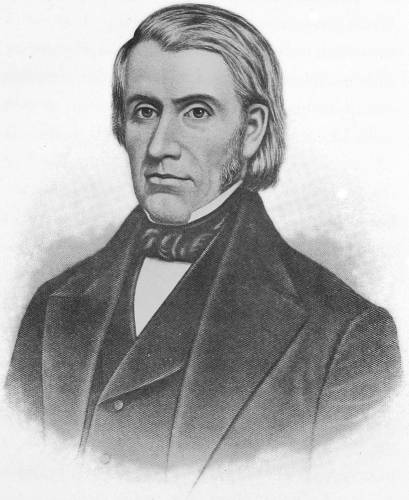

| Portrait of Cyrus Hall McCormick, 1839 | 76 |

| Panoramic View Showing the McCormick Reaper Works before the Chicago Fire of 1871, on Chicago River, East of Rush Street Bridge | 82 |

| Men of Progress | 96[xii] |

| The First McCormick Self-Rake Reaping Machine | 112 |

| Portrait of Cyrus Hall McCormick, 1858 | 120 |

| Portrait of Cyrus Hall McCormick, 1867 | 136 |

| McCormick Reaper Cutting on a Side Hill in Pennsylvania | 144 |

| Reaper Drawn by Oxen in Algeria | 150 |

| The Reaper in Heavy Grain | 166 |

| Harvesting near Spokane, Washington | 174 |

| Portrait of Cyrus Hall McCormick, 1883 | 182 |

| The Works of the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company | 190 |

| McCormick Reaper in Use in Russia | 196 |

| Chart Showing Relative Distribution of Values by Producing Countries of 1908 of World's Production Of Five Principal Grains | 206 |

| Chart Showing Relative Values in 1908 of the World's Production of the Five Principal Grains | 206 |

| Mammoth Wheat-Field in South Dakota with Twenty Harvesters in Line | 214 |

| Harvesting in Roumania | 222 |

| Harvesting Heavy Grain, South America | 230 |

| Indians Reaping their Harvest, White Earth, Minnesota | 236 |

| A Harvest Scene Upon a Russian Estate | 242 |

EITHER by a very strange coincidence, or as a phenomenon of the instinct of self-preservation, the year 1809, which was marked by famine and tragedy in almost every quarter of the globe, was also a most prolific birthyear for men of genius. Into this year came Poe, Blackie, and Tennyson, the poet laureates of America, Scotland, and England; Chopin and Mendelssohn, the apostles of sweeter music; Lincoln, who kept the United States united; Baron Haussemann, the beautifier of Paris; Proudhon, the prophet of communism; Lord Houghton, who did much in science, and Darwin, who did most; FitzGerald, who made known the literature of Persia; Bonar, who wrote hymns; Kinglake, who wrote histories; Holmes, who[2] wrote sentiment and humor; Gladstone, who ennobled the politics of the British empire; and McCormick, who gave the world cheap bread, and whose life-story is now set before us in the following pages.

None of these eminent men, except Lincoln, began life in as remote and secluded a corner of the world as McCormick. His father's farm was at the northern edge of Rockbridge County, Virginia, in a long, thin strip of fairly fertile land that lay crumpled between the Blue Ridge on the east and the Alleghanies on the west. It was eighteen miles south of the nearest town of Staunton, and a hundred miles from the Atlantic coast. The whole region was a quiet, industrious valley, whose only local tragedy had been an Indian massacre in 1764, in which eighty white settlers had been put to death by a horde of savages.

The older men and women of 1809 could remember when wolf-heads were used as currency; and when the stocks and the ducking stool stood in the main street of Staunton. Also, they were fond of telling how the farmers of the[3] valley, when they heard that the Revolution had begun in Massachusetts, carted 137 barrels of flour to Frederick, one hundred miles north, and ordered it sent forthwith to the needy people of Boston. This grew to be one of the most popular tales of local history,—an epic of the patriots who fought for liberty, not with gunpowder but flour.

By 1809 the more severe hardships of the pioneer days had been overcome. Houses were still built of logs, but they were larger and better furnished. In the McCormick homestead, for instance, there was a parlor which had the dignity of mahogany furniture, and the luxury of books and a carpet. The next-door county of Augusta boasted of thirteen carriages and one hundred and two cut-glass decanters. And the chief sources of excitement had evolved from Indian raids and wolf-hunts into elections, lotteries, and litigation.

It was perhaps fortunate for the child McCormick that he was born in such an out-of-the-way nook, for the reason that in 1809 almost the whole civilized world was in a turmoil. In England[4] mobs of unemployed men and women were either begging for bread or smashing the new machines that had displaced them in the factories. In the Tyrol, sixty thousand peasants, who had revolted from the intolerable tyranny of the Bavarians, were being beaten into submission. In Servia, the Turks were striking down a rebellion by building a pyramid of thirty thousand Servian skulls,—a tragic pile which may still be seen midway between Belgrade and Stamboul. Sweden was being trampled under the feet of a Russian army; and the greater part of Holland, Austria, Germany, and Spain had been so scourged by the hosts of Napoleon as to be one vast shamble of misery and blood.

In the United States there was no war, but there certainly did exist an abnormal surplus of adversity. The young republic, which had fewer white citizens than the two cities of New York and Chicago possess to-day, was being terrorized in the West by the Indian Confederacy of Tecumseh; and its flag had been flouted by England, France, and the Barbary pirates. Its total revenue was much less than the value of[5] last year's hay crop in Vermont. It was desperately poor, with its people housed for the most part in log cabins, clothed in homespun, and fed every winter on food that would cause a riot in any modern penitentiary.

There was no such thing known, except in dreams, as the use of machinery in the cultivation of the soil. The average farmer, in all civilized countries, believed that an iron plow would poison the soil. He planted his grain by the phases of the moon; kept his cows outside in winter; and was unaware that glanders was contagious. Joseph Jenks, of Lynn, had invented the scythe in 1655, "for the more speedy cutting of grasse"; and a Scotchman had improved it into the grain cradle. But the greater part of the grain in all countries was, a century ago, being cut by the same little hand sickle that the Egyptians had used on the banks of the Nile and the Babylonians in the valley of the Euphrates.

The wise public men of that day knew how urgent was the need of better methods in farming. Fifteen years before, George Washington[6] had said, "I know of no pursuit in which more real and important service can be rendered to any country than by improving its agriculture." But it was generally believed that the task was hopeless; and any effort to encourage inventors had hitherto been a failure. An English society, for instance, had offered a prize of one hundred and fifty dollars for a better method of reaping grain, and the only answer it received was from a traveller who had seen the Belgians reaping with a two-foot scythe and a cane; the cane was used to push the grain back before it was cut, so that more grain could be cut at a blow. As to whether or not he received the prize for this discovery is not recorded.

The city of New York in 1809 was not larger than the Des Moines of to-day, and not nearly so well built and prosperous. Two miles to the north of it, through swamps and forests, lay the clearing that is now known as Herald Square. There was no street railway, nor cooking range, nor petroleum, nor savings bank, nor friction match, nor steel plow, neither in New York nor anywhere else. And the one pride and[7] boast of the city was Fulton's new steamboat, the Clermont, which could waddle to Albany and back, if all went well, in three days or possibly four.

As for social conditions, they were so hopelessly bad that few had the heart to improve them. The house that we call a "slum tenement" to-day would have made an average American hotel in 1809. Rudeness and rowdyism were the rule. Drunkenness was as common, and as little considered, as smoking is at the present time; there was no organized opposition to it of any kind, except one little temperance society at Saratoga. There were no sewers, and much of the water was drawn from putrid wells. Many faces were pitted with small-pox. Cholera and yellow jack or strange hunger-fevers cut wide swaths of death again and again among the helpless people. There was no science, of course, and no sanitation, and no medical knowledge except a medley of drastic measures which were apt to be as dangerous as the disease.

The desperate struggle to survive appears[8] to have been so intense that there was little or no social sympathy. There was very little pity for the pauper,—he was auctioned off to be half starved by the lowest bidder; and for the criminal there was no feeling except the utmost repulsion and abhorrence. It was found, for instance, in 1809, that in the jail in New York there were seventy-two women, white and black, in one chairless, bedless room, all kept in order by a keeper with a whip, and fed like cattle from a tub of mush, some eating with spoons and some with cups and some with their unwashed hands. And the men's room of that jail, says this report, "is worse than the women's."

Also, in 1809, the chronic quantity of misery had been terribly augmented by the Embargo,—that most ruinous invention of President Jefferson, whereby American ships were swept from the sea, with a loss to capital of twelve millions a year, and a loss to labor of thirty thousand places of employment. According to this amazing act of political folly, every market-boat sailing from New Jersey to New[9] York—every sailboat or canoe—had to give bail to the federal government before it dared to leave the dock.

Whatever flimsy little structure of industry had been built up in thirty years of independence, was thrown prostrate by this Embargo. A hundred thousand men stood on the streets with helpless hands, begging for work or bread. The jails were jammed with debtors,—1,300 in New York alone. The newspapers were overrun by bankruptcy notices. The coffee-houses were empty. The ships lay mouldering at the docks. In those hand-to-mouth days there was no piled-up reserve of food or wealth,—no range of towering wheat-banks at every port; and the seaboard cities lay for a time as desolate as though they had been ravaged by a pestilence.

In that darkest year the hardscrabble little republic learned and remembered one of its most important lessons,—the fact that liberty and independence are not enough. Here it was, an absolutely free nation,—the only free civilized country in the world,—and yet as miserable[10] and poor and hungry as though it were a mere province of a European empire. So, by degrees, there came a change in the American point of view,—a swing from politicalism to industrialism. The mass of the people were now surfeited with oratory and politics and war. They began to settle down to hard facts and hard work. Instead of declaiming about the rights of man, they began to build roads and weave cloth and organize stock companies. Slowly they came to realize that a second Revolution must be wrought,—a Revolution that would enable them to write a Declaration of Independence against Hunger and Hardship and Hand Labor.

Up to the year 1809 the chief topics of interest in American legislatures and grocery stores were the blockades, the Embargo, the treaties, the badness of Napoleon, the blunders of Jefferson, and the rudeness of England and France. But after that year the chief topics of interest came to be of a wholly different sort. They were such as the tariff, the currency, the building of factories and canals, the opening of public[11] lands, the problem of slavery, and the development of the West. The hardy, victorious little nation began to talk less and work more; and so by a natural evolution of thought the era of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson came to an end, and the era of Robert Fulton and Peter Cooper and Cyrus Hall McCormick was in its dawn.

From 1810 to 1820 there was a rush to the land. Twenty million acres were sold, in most cases for two dollars an acre. Thousands of men who had been sailors turned their backs on the sea and learned to till the soil. Town laborers, too, whose wages had been fifty cents a day, tramped westward along the Indian trails and seized upon scraps of land that lay ownerless. Nine out of ten Americans began to farm with the utmost energy and perseverance,—but with what tools? With the wooden plow, the sickle, the scythe, and the flail, the same rude hand-labor tools that the nations of antiquity had tried to farm with,—the tools of failure and slavery and famine.

Such was the predicament of this republic[12] for the first seventy-five years of its life. It could not develop beyond the struggle for food. It was chained to the bread-line. It could not feed itself. Not even nine-tenths of its people could produce enough grain to satisfy its hunger. Again and again, until 1858, wheat had to be imported by this nation of farmers. So, as we now look back over those basic years, from the summit of the twentieth century, we can see how timely an event it was that in the dark year 1809 the inventor of the Reaper was born.

IF we wish to solve the riddle of the Reaper,—to know why it was not invented in any of the older nations that rose to greatness and perished in so many instances for lack of bread,—we can find the key to the answer in the home and the ancestry of the McCormicks. We shall see that the family into which he was born represented in the highest degree that new species of farmer,—self-reliant, studious, enterprising, and inventive,—which was developed in the pioneer period of American history.

Robert McCormick, the father of Cyrus, was in his most prosperous days the owner of four farms, having in all 1,800 acres. But his acres were only one-half of his interests. He owned as well two grist-mills, two sawmills, a smelting-furnace, a distillery, and a blacksmith-shop. He did much more than till the soil. He hammered iron and shaped wood, and did both well, as those can testify who have seen an iron crane[14] and walnut cabinet that were made by his hands. More than this, he invented new types of farm machinery,—a hemp-brake, a clover huller, a bellows, and a threshing-machine.

The little log workshop still stands where Robert McCormick and his sons hammered and tinkered on rainy days. It is about twenty-four feet square, with an uneven floor, and a heavy door that was hung in place by home-made nails and home-made hinges. There was a forge on either side of the chimney, so that two men could work at the same time; and one small rusted anvil is all that now remains of its equipment.

In this shop the first practical reaping machine was built by Cyrus Hall McCormick in 1831

As for the McCormick homestead itself, there were so many manufacturing activities in it that it was literally half a home and half a factory. Shoes were cobbled, cotton, flax, and wool were spun into yarn, woven into cloth, and fashioned into clothes for the whole family. The stockings and mitts and caps were all home-made, and so was the cradle in which the eight children were rocked. What with the moulding of candles, and sewing of carpet-rags, and curing of hams,[15] and boiling of soap, and drying of herbs, and stringing of apples, the McCormick home was practically a school of many trades for the people who lived under its roof.

Robert McCormick was an educated man. He was not at all like the poor serfs who tilled the soil of Europe. He belonged to the same general class as those other eminent farmers,—Washington, Jefferson, Adams, Webster, and Clay. He was a reader of deep books and a student of astronomy. Lawyers and clergymen would frequently drive to his house to consult with him. And in mechanical pursuits he had an unusual degree of skill, having been born the son of a weaver and accustomed from babyhood to the use of machinery.

He was a gentle, reflective man, with a genius for self-reliance in any great or little emergency. When a new stone church was built, and he found that his pew was so dark that he could not see to read the hymns, he promptly cut a small window in the wall,—a peculiarity which is still pointed out to visitors. On another occasion, with this same spirit of resourcefulness, he drove[16] the spectre of yellow fever from the home. This dreaded disease was gathering in a full harvest in the farm-houses of the county. It had cut down three of Mrs. McCormick's family,—her father, mother, and brother,—and had swung its fatal scythe toward the boy Cyrus, who was then five years of age. When the doctor was called, he insisted that the child should be bled. "But you bled all the others, and they died," said Robert McCormick quietly; "I'll have no more bleedings." No remedy for yellow fever, except bleeding, was known to the doctors of a century ago, so Robert McCormick at once invented a remedy. He devised a treatment of hot baths, hot teas, and bitter herbs; and Cyrus was rescued from the fever and restored to perfect health.

Such a man as Robert McCormick would have been practically impossible in any other country at that time. There, in that isolated hollow of the Virginian mountains, he was a citizen of a free country. His vote had helped to make Thomas Jefferson President. He was a proprietor, not a serf nor a tenant. He was[17] not compelled to divide up every cord of wood and bushel of wheat with a king or a landlord. Whatever he earned was his own. He was an American; and thus, in the endless chain of cause and effect, we can trace the origin of the Reaper back, if we wish, to George Washington and Christopher Columbus.

The whole spirit of the young republic pushed towards the invention of labor-saving machinery,—towards replacing the hoe with the steel plow, the needle with the sewing-machine, the puddling-furnace with the Bessemer converter, the sickle with the Reaper. And it is fair to say that the social forces that represented the American spirit were focused to a remarkable degree in the home in which Cyrus H. McCormick had his birth and his education.

There was another contributing influence, too, in the making of McCormick,—the fact that the blood of his father and mother came to him in a pure strain of Scotch-Irish. It was this inheritance that endowed him with the tenacity and unconquerable resiliency that enabled him not only to invent a new machine, but to create[18] a new industry and hold fast to it against all comers.

The Scotch-Irish! The full story of what the United States owes to this fire-hardened race has never yet been told,—it is a tale that will some day be expanded into a fascinating volume of American history. It is not possible to understand either the character or the success of McCormick without knowing the Scotch-Irish influences that shaped him.

The one man who did more to launch the Scotch-Irish on their conquering way, so it appears, was John Knox. This preacher-statesman, "who never feared the face of man," forced Queen Mary from her throne, and established self-government and a pure religion in Scotland, about seventy-five years after the discovery of America. This brought English armies down upon the Scotch, and for very nearly two centuries the struggle was bitter and desperate, the Scotch refusing to compromise or to bate one jot or tittle of a covenant which many of them had signed with their blood.

At the height of this conflict, about 300,000[19] of these Scotch Covenanters left their ravaged country and set out in a fleet of little vessels for the north of Ireland. Here they settled in the barren and boggy province of Ulster, and presto! in the course of two generations Ulster became the most prosperous, moral, and intelligent section of the British empire. Its people were, beyond a doubt, the best educated masses of that period, either in Great Britain or anywhere else. They were the most skilful of farmers. They wove woollen cloth and the finest of linen. They built schools and churches and factories. But in 1698, the English Parliament, jealous of such progressiveness, passed laws against their manufacturing, and Ulster was overrun, as Scotland had been, with the police and the soldiery of England.

The Scotch-Irish fought, of course, even against such odds. They had never learned how to submit. But as the devastation of Ulster continued, they resolved to do as their great-grandfathers had done,—emigrate to a new country. They had heard good reports of America, through several of their leaders who had[20] been banished there by the British government. So they packed up their movable property, and set out across the wide uncharted Atlantic Ocean in an exodus for liberty of industry and liberty of conscience.

By the year 1776 there were more than 500,000 of the Scotch-Irish in this country. They went first across the Alleghanies, into the new lands of western Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Texas. Beyond all question, they were the hardiest and ablest founders of the republic. They dissolved the rule of the Cavaliers in Virginia; and in the little hamlet of Mecklenburg they planned the first defiance of Great Britain and struck the key-note of the Revolution. They gave Washington thirty-nine of his generals, three out of four members of his cabinet, and three out of five judges of the first Supreme Court.

Of all classes of settlers in the thirteen colonies, they were the best prepared and most willing for the struggle with England, for the reason that they had begun to fight for liberty two hundred and fifty years before the battle of[21] Bunker Hill. They were not amateurs in the work of revolution. They were veterans. And so, because they were pioneers and patriots by nature and inheritance, the Scotch-Irish became, in the words of John Fiske, "the main strength of our American democracy."

Naturally, they were pathfinders in industry as well as in the matter of self-government, as many of them had been manufacturers in Ireland. "Thousands of the best manufacturers and weavers in Ulster went to seek their bread in America," writes Froude, "and they carried their art and their tools with them." In one instance, by the failure of the woollen trade, 20,000 of them were driven to the United States. As might have been expected, these Scotch-Irish Americans have produced not only five of our Presidents, but also such merchants as A. T. Stewart; such publishers as Harper, Bonner, Scribner, and McClurg; and such inventors as Joseph Henry, Morse, Fulton, and McCormick. They were possibly the first large body of people who had ever been driven from manufacturing into farming; and it was not at all[22] surprising, therefore, that the new profession of making farm machinery should have been born upon a Scotch-Irish farm.

As for Cyrus H. McCormick, he represented the fourth generation of American McCormicks. His great-grandfather, Thomas McCormick, quit Ulster in the troublous days of 1735. He was a soldier at Londonderry; and later became noted as an Indian fighter in Pennsylvania. His son Robert, who moved south to Virginia, carried a rifle for American independence at the battle of Guilford Court-house, North Carolina, in 1781. He was a farmer and weaver by occupation, a typical Ulsterman, whose farm was a busy workshop of invention and manufacturing.

On his mother's side, too, Cyrus McCormick had behind him a line of battling Scotch-Irish. She was the daughter of a Virginian farmer named Patrick Hall, one of whose forefathers had been driven out of Armagh by the massacre of 1641. Patrick Hall was the leader of the old-school Presbyterians in his region of Virginia. So rigid was he in his loyalty to the faith of the[23] Covenanters, that once when a new minister came to preach in the little kirk, and lined out a Watts hymn instead of a psalm of David, Patrick Hall picked up his hat and strode out, followed by a goodly part of the congregation. He at once built upon his own farm a new church of limestone, in which no such levity as hymn-singing was permitted.

Cyrus McCormick's mother inherited her father's strength of character, without his severity. She was a thorough Celt, impulsive, free-spoken, and highly imaginative. Judging from the stories about her that are remembered in the neighborhood, it is evident that she was a woman of exceptional quality of mind. She was not as studious as her husband, but quicker and more ambitious. As a girl, she had been strikingly handsome, with a tall and commanding figure. She was saving and shrewd, with the Scotch-Irish passion for "getting ahead." She allowed no idle moments in the home. If the children were dressed before breakfast was ready, out they went to cut wood or weed the garden. She knew the profession[24] of housekeeping in all its old-fashioned complexity; and she worked at it from dawn to starlight, with no rest except the relief of flitting from one task to another.

"Mrs. McCormick came riding by our farm one day," said an aged neighbor, "at a time when my father and mother were hurrying to save some hay from a coming rain-storm. 'If you don't hurry up you'll be too late,' she said; and then tying her horse to the fence she picked up a rake and helped with the hay until it was all in the barn. That's the kind of woman she was,—always full of energy and ready to help."

But Mrs. McCormick was much more than industrious. She had a fine pride in the ownership of beautiful things,—flowers and handsome clothes and silverware and mahogany furniture. Her flock of peacocks was one of the sights of the county; and in her later life, when she was for ten years the sole manager of the farm, she was accustomed to drive about in a wonderful carriage with folding steps, drawn by prancing horses and driven by a stately colored coachman,—an equipage of so much[25] style and grandeur that it is still remembered by the neighbors. "She loved to drive fast," said one old lady; "and I was much impressed as a little girl with the startling way in which her horses would come clattering and dancing up to the door."

Thus there was in the McCormick home the spiritual and imaginative element that was vital to the development of a man whose whole life was a battle against the prejudices and "impossibilities" of the world. Cyrus McCormick was predestined, we may legitimately say, by the conditions of his birth, to accomplish his great work. From his father he had a specific training as an inventor; from his mother he had executive ability and ambition; from his Scotch-Irish ancestry he had the dogged tenacity that defied defeat; and from the wheat-fields that environed his home came the call for the Reaper, to lighten the heavy drudgery of the harvest.

NOT far from the McCormick homestead was the "Old Field School," built of logs and with a part of one of the upper logs cut out to provide a window. Here the boy Cyrus sat on a slab bench and studied five books as though they were the only books in the world,—Murray's Grammar, Dilworth's Arithmetic, Webster's Spelling Book, the Shorter Catechism, and the Bible.

He was a strong-limbed, self-contained, serious-natured boy, always profoundly intent upon what he was doing. Even at the age of fifteen he was inventive. One winter morning he brought to school a most elaborate map of the world, showing the two hemispheres side by side. First he had drawn it in ink upon paper, then pasted the paper upon linen, and hung it upon two varnished rollers. This map, which is still preserved, reveals a remarkable degree of skill and patience; and the fact that a mere lad[27] could conceive of and create such a map was a week's wonder in the little community. "That boy," declared the teacher, "is beyond me."

At about this time he undertook to do a man's work in the reaping of the wheat, and here he discovered that to swing a cradle against a field of grain under a hot summer sun was of all farming drudgeries the severest. Both his back and his brain rebelled against it. One thing at least he could do,—he could make a smaller cradle, that would be easier to swing; and he did this, whittling away in the evening in the little log workshop.

"Cyrus was a natural mechanical genius," said an old laborer who had worked on the McCormick farm. "He was always trying to invent something." "He was a young man of great and superior talents," said a neighbor. At eighteen he studied the profession of surveying, and made a quadrant for his own use. This is still preserved, and bears witness to his good workmanship. From this time until his twenty-second year, there is nothing of exceptional interest recorded of him. He had grown to be[28] a tall, muscular, dignified young man. The neighbors, in later years, remembered him mainly because he was so well dressed on Sundays, in broadcloth coat and beaver hat, and because of his fine treble voice as he led the singing in the country church.

Even as a youth he was absorbed in his inventions and business projects. He had no time for gayeties. In a letter written from Kentucky to a cousin, Adam McChesney, in 1831, he says: "Mr. Hart has two fine daughters, right pretty, very smart, and as rich probably as you would wish; but alas! I have other business to attend to."

Ever since Cyrus was a child of seven, it had been the most ardent ambition of his father to invent a Reaper. He had made one and tried it in the harvest of 1816, but it was a failure. It was a fantastic machine, pushed from behind by two horses. A row of short curved sickles were fastened to upright posts, and the grain was whirled against them by revolving rods. It was highly ingenious, but the sinewy grain merely bunched and tangled around its futile[29] sickles; and the poor old Reaper that would not reap was hauled off the field, to become one of the jokes of the neighborhood.

This failure did not dishearten Robert McCormick. He persevered with Scotch-Irish tenacity, but in secret. Hurt by the jests of the neighbors, he worked thenceforward with the door of his workshop locked, or at night. He hid his Reaper, too, upon a shelf inside the workshop. "He allowed no one to see what he was doing, except his sons," said Davis McCormick, who is now the only living person in the neighborhood with a memory that extends back to that early period. "Yes," said this lone octogenarian, "Robert McCormick was a good man, a true Christian; and he worked for years to make a Reaper. He always kept his plans to himself, and he told his wife that if visitors came to the house, she should send one of the children to fetch him, and not allow the visitors to come to his workshop."

By the early Summer of 1831, Robert McCormick had so improved his Reaper that he gave it a trial in a field of grain. Again it was a[30] failure. It did cut the grain fairly well, but flung it in a tangled heap. As much as this had been done before by other machines, and it was not enough. To cut the grain was only one-half of the problem; the other half of the problem, which up to this time no one had solved, was how to properly handle and deliver the grain after it was cut.

By this time Cyrus had become as much of a Reaper enthusiast as his father. Also, he had been studying out the reasons for his father's failure, and working out in his mind a new plan of construction. How this new plan was slowly moulded into shape by his creative fancy is now told for the first time. A manuscript, written by Cyrus H. McCormick himself, and which has not hitherto been made public, gives a complete description of the process of thought by which he became the inventor of the first practical Reaper. This account, it may be said in explanation, was written by Mr. McCormick shortly before the Chicago fire of 1871. It was to be published at that time, and was in type when the fire came and left not a vestige[31] of the printery. The original manuscript was preserved; but the labor of rebuilding his factory prevented him from carrying out his original design. He wholly forgot his authorship in the troubles of his city; and so his own story of his invention lay untouched among the private papers of the family for thirty-eight years.

"Robert McCormick," says this document, "being satisfied that his principle of operation could not succeed, laid aside and abandoned the further prosecution of his idea." He had labored for fifteen years to make a Reaper that would reap, and he had failed.

At this point Cyrus took up the work that his father had reluctantly abandoned. He had never seen or heard of any Reaper experiments except those of his father; but he believed he saw a better way, and "devoted himself most laboriously to the discovery of a new principle of operation."

He showed his originality at the outset by beginning where his father and all other Reaper inventors had left off,—with the cutting of grain that lay in a fallen and tangled mass. He faced[32] the problem worst end first. The Reaper that would cut such grain, he believed, must first separate the grain that is to be cut from the grain that is left standing. It must have at the end of its knife a curved arm—a divider. This idea was simple, but in the long history of harvesting grain no one had thought of it before.

Next, in order to cut this snarled and prostrate grain without missing any of it, the knife must have two motions: its forward motion, as drawn by the horses, and also a slashing sideways motion of its own. How was this to be done? McCormick's first thought was to cut the grain with a whirling wheel-knife, but this plan presented too many new difficulties. Suddenly the idea came to him—why not have a straight blade, with a back and forward motion of its own? This was the birth-idea of the reciprocating blade, which has been used to this day on all grain-cutting machines. It was not, like the divider, a wholly new conception; but Cyrus McCormick conceived it independently, and did more than any one else to establish it as the basic feature of the Reaper.

[33] The third problem was the supporting of the grain while it was being cut, so that the knife would not merely flatten it to the ground. McCormick solved this by placing a row of fingers at the edge of the blade. These fingers projected a few inches, in such a way that the grain was caught and held in position to be cut. The shape of these fingers was afterwards much improved, to prevent wet grain from clogging the slit in which the knife slid back and forth.

A fourth device was still needed to lift up and straighten the grain that had fallen. This was done by a simple revolving reel, such as fishermen use for the drying of their nets. Several of the abortive Reapers that had been tried elsewhere had possessed some sort of a reel; but McCormick made his much larger than any other, so that no grain was too low to escape it.

The fifth factor in this assembling of a Reaper was the platform, to catch the cut grain as it fell; and from which the grain was to be raked off by a man who walked alongside of it. The sixth was the idea of putting the shafts on the outside, or stubble side, of the Reaper, making it a side-draught,[34] instead of a "push" machine. And the seventh and final factor was the building of the whole Reaper upon one big driving-wheel, which carried the weight and operated the reel and cutting-blade. The grain-side end of the blade was at first supported by a wooden runner, and later—the following year—by a small wheel.

Built and used by Cyrus Hall McCormick on Walnut Grove Farm, Va., in 1831

Such was the making of the first practical Reaper in the history of the world. It was as clumsy as a Red River ox-cart; but it reaped. It was made on right lines. The "new principle" that the youth McCormick laboriously conceived in the little log workshop became the basic type of a wholly new machine. It has never been displaced. Since then there have been 12,000 patents issued for reaper and mower inventions; but not one of them has overthrown the type of the first McCormick Reaper. Not one of the seven factors that he assembled has been thrown aside; and the most elaborate self-binder of to-day is a direct descendant of the crude machine that was thus created by a young Virginian farmer in 1831.

[35] The young inventor toiled "laboriously," he says, to complete his Reaper in time for the harvest of 1831. He was very nearly too late, but a small patch of wheat was left standing at his request; and one day in July, with no spectators except his parents and his excited brothers and sisters, Cyrus put a horse between the shafts of his Reaper, and drove against the yellow grain. The reel revolved and swept the gentle wheat downwards upon the knife. Click! Click! Click! The white steel blade shot back and forth. The grain was cut. It fell upon the platform in a shimmering golden swath. From here it was raked off by a young laborer named John Cash. It was a roughly done specimen of reaping, no doubt. The reel and the divider worked poorly. But for a preliminary test it was a magnificent success. Here, at last, was a Reaper that reaped, the first that had ever been made in any country.

The scene of this first "reaping by horse-power" was then, and is to-day, one of unusual beauty. The field is near by the farm-house, rolling in several undulations to the rim of a[36] winding little rivulet. In the centre of the field is a single tree, a wide-branched white oak, which was probably born before the first colonists arrived at Jamestown. And in the background, not more than two miles distant, rise the tall and jagged crags of the Blue Ridge, twelve sharp peaks flung high from deep ravines, on which the lights and shades are incessantly changing,—a most impressive staging for the first act of the drama of the Reaper.

This McCormick farm, having 600 acres of land, is now owned by the McCormick family. The whole region has changed but little. Once, and once only, the great noisy outside world surged into this quiet valley,—when a Union army under General Butler clattered through it, burning and destroying, and so close to the McCormick homestead that the blue uniforms could be seen from its front windows. Doubtless, when farmers have time to take a proper pride in the history of their own profession, they will visit the McCormick farm as a spot of historic interest,—the place where the New Agriculture was born. It is no longer a difficult place[37] to reach, as it is now possible to lunch to-day in either Chicago or New York and to-morrow in the same comfortable red brick farm-house that sheltered the McCormicks in 1831.

Several days after the advent of the Reaper on the home farm, Cyrus McCormick had improved its reel and divider, and was ready for a public exhibition at the near-by village of Steele's Tavern. Here, with two horses, he cut six acres of oats in an afternoon, a feat which was attested in court in 1848 by his brothers William and Leander, and also by three of the villagers, John Steele, Eliza Steele, and Dr. N. M. Hitt. Such a thing at that time was incredible. It was equal to the work of six laborers with scythes, or twenty-four peasants with sickles. It was as marvellous as though a man should walk down the street carrying a dray-horse on his back.

The next year, 1832, Cyrus McCormick came out with his Reaper into what seemed to him "the wide, wide world." He gave a public exhibition near the little town of Lexington, which lay eighteen miles south of the farm. Fully one[38] hundred people were present—several political leaders of local fame, farmers, professors, laborers, and a group of negroes who frolicked and shouted in uncomprehending joy.

At the start, it appeared as though this new contraption of a machine, which was unlike anything else that human eyes had ever seen, was to prove a grotesque failure. The field was hilly, and the Reaper jolted and slewed so violently that John Ruff, the owner of the field, made a loud protest.

"Here! This won't do," he shouted. "Stop your horses. You are rattling the heads off my wheat."

THE FIELD ON WHICH THE FIRST McCORMICK REAPER WAS TRIED, WALNUT GROVE FARM, VIRGINIA

THE FIELD ON WHICH THE FIRST McCORMICK REAPER WAS TRIED, WALNUT GROVE FARM, VIRGINIA

This was a hard blow to the young farmer-inventor. Several laborers, who were openly hostile to the machine as their rival in the labor market, began to jeer with great satisfaction. "It's a humbug," said one. "Give me the old cradle yet, boys," said another. These men were hardened and bent and calloused with the drudgery of harvesting. They worked twelve and fourteen hours a day for less than a nickel an hour. But they were as resentful toward[39] a Reaper as the drivers of stage-coaches were to railroads, or as the hackmen of to-day are towards automobiles.

At this moment of apparent defeat, a man of striking appearance, who had been watching the floundering of the Reaper with great interest, came to the rescue.

"I'll give you a fair chance, young man," he said. "That field of wheat on the other side of the fence belongs to me. Pull down the fence and cross over."

This friend in need was the Honorable William Taylor, who was several years later a candidate for the governorship of Virginia. His offer was at once accepted by Cyrus McCormick, and as the second field was fairly level, he laid low six acres of wheat before sundown. This was no more than he had done in 1831, but on this occasion he had conquered a larger and more incredulous audience.

After the sixth acre was cut, the Reaper was driven with great acclaim into the town of Lexington and placed on view in the court-house square. Here it was carefully studied by a[40] Professor Bradshaw of the Lexington Female Academy, who finally announced in a loud and emphatic voice, "This—machine—is worth—a hundred—thousand—dollars." This praise, from "a scholar and a gentleman," as McCormick afterwards called him, was very encouraging. And still more so was the quiet word of praise from Robert McCormick, who said, "It makes me feel proud to have a son do what I could not do."

Of all who were present on that memorable summer day, not one is now alive. Neither in Lexington nor in Staunton—the towns that lay on either side of the McCormick farm—can we find any one who saw the Reapers of 1831 and 1832. But among those who testified at various lawsuits that they had seen the Lexington Reaper operate were Colonel James McDowell, Colonel John Bowyer, Colonel Samuel Reed, Colonel A. T. Barclay, Dr. Taylor, William Taylor, John Ruff, John W. Houghawout, John Steele, James Moore, and Andrew Wallace. There was an old lady, also, in 1885, Miss Polly Carson, who told how she had seen[41] the Reaper hauled along the road by two horses, which, she said, "had to be led by a couple of darkies, because they were scared to death by the racket of the machine." And she expressed the general unbelief of that day, very likely, by saying, "I thought it was a right smart curious sort of a thing, but that it wouldn't come to much."

Cyrus McCormick was far from being the first to secure a Reaper patent. He was the forty-seventh. Twenty-three others in Europe and twenty-three in the United States had invented machines of varying inefficiency; but there was not one of these which could have been improved into the proper shape. Without any exception, the rival manufacturers who rose up in later years to fight McCormick did him the homage of copying his Reaper; and certainly none of them attempted to offer for sale any type of machine that was invented prior to 1831.

A careful study of the pre-McCormick Reapers reveals one fault common to all,—they were made by theorists, to cut ideal grain in ideal fields. Some of them, if grain always grew[42] straight and was perfectly willing to be cut, might have been fairly useful. They assuredly might have succeeded if grain grew in a parlor. But to cut actual grain in actual fields was another matter, and quite beyond their power. None of them, apparently, knew the fundamental difference between a Reaper and a mower. They did not observe that grain is easy to cut but hard to handle, while grass is hard to cut and easy to handle; and they persisted in the assumption that grain could be reaped by a mower.

These inventors who failed, but who doubtless blazed the way by their failures to the final success of McCormick, were not, as he was, a practical farmer on rough and hilly ground. One was a clergyman, who devised a six-wheel chariot, with many pairs of scissors, and which was to be pushed by horses and steered by a rudder that in rough ground would jerk a man's arm out of joint. A second of these inventors was a sailor, who experimented with a few stalks of straight grain stuck in gimlet holes in his workshop floor. A third was an actor,[43] who had built a Reaper that would cut artificial grain on the stage. A fourth was a school-teacher, a fifth a machinist, and so on. In no instance can we find that any one of these pre-McCormick inventors was a farmer, who therefore knew what practical difficulties had to be overcome.

The farmers, on the other hand, thought first of these difficulties and scoffed at the parlor inventors. The editor of the "Farmer's Register" spoke the opinion of most farmers of that time when he said that "an insurmountable difficulty will sometimes be found to the use of reaping-machines in the state of the growing crops, which may be twisted and laid flat in every possible direction. A whole crop may be ravelled and beaten down by high winds and heavy rains in a single day."

One of the basic reasons, therefore, for the success of Cyrus McCormick was the fact that he was not a parlor inventor. He was primarily a farmer. He knew what wheat was and how it grew. And his first aim in making a reaper was not to produce a mechanical curiosity, nor to[44] derive a fortune from the sale of his patent, but to cut the grain on his father's farm.

So far as the pre-McCormick inventors are concerned, the whole truth about them seems to be that a few invented fractional mowers or reapers that were fairly good as far as they went, and that most of them invented nothing that became of any lasting value. Nine-tenths of them were pathfinders in the sense that they showed what ought not to be done.

Very little attention would have been given them had it not been for the persistent effort made by rival manufacturers to detract from McCormick's reputation as an inventor. This they did in a wholly impersonal manner, of course, so that they should not be obliged to pay him royalties, and because his prestige as the original inventor of the Reaper enabled him to outsell them among the farmers.

But now that the competition of Reaper manufacturers has been tempered by consolidation, the time has arrived to do justice to Cyrus McCormick as the inventor of the Reaper. The stock phrase,—"He was less of an inventor[45] than a business man," which was so widely used against him during his lifetime, ought now in all fairness to be laid aside. The fact is, as we have seen, that he was schooled as a boy into an inventive habit of mind; and that before his invention of the Reaper, he had devised a new grain-cradle, a hillside plow, and a self-sharpening plow. There is abundant corroborative evidence in the letters which he wrote to his father and brothers, instructing them to "make the divider and wheel post longer," to "put the crank one inch farther back," and so forth. Also, in the will of Robert McCormick, there is a clause authorizing the executor to pay a royalty to Cyrus of fifteen dollars apiece on whatever machines were sold by the family during that season, showing that the father, who of all men was in the best position to know, regarded Cyrus as the inventor.

Of all the manufacturers who fought McCormick in the patent suits of early days, three only have survived to see the passing of the McCormick Centenary—Ralph Emerson, C. W. Marsh, and William N. Whiteley. In response[46] to a question as to Cyrus McCormick's place as an inventor, Mr. Whiteley said: "McCormick invented the divider and the practical reel; and he was the first man to make the Reaper a success in the field." Mr. Marsh said: "He was a meritorious inventor, although he combined the ideas of other men with his own; and he produced the first practical side-delivery machine in the market." And Mr. Emerson said: "The enemies of Cyrus H. McCormick have said that he was not an inventor, but I say that he was an inventor of eminence."

Thus it appears that the invention of the Reaper was not in any sense unique; it came about by an evolutionary process such as produced all other great discoveries and inventions. First come the dreamers, the theorists, the heroic innovators who awaken the world's brain upon a new line of thought. Then come the pioneers who solve certain parts of the problem and make suggestions that are of practical value. And then, in the fulness of time, comes one masterful man who is more of a doer than a dreamer, who works out the exact combination[47] of ideas to produce the result, and establishes the new product as a necessary part of the equipment of the whole human family.

Cyrus Hall McCormick invented the Reaper. He did more—he invented the business of making Reapers and selling them to the farmers of America and foreign countries. He held preëminence in this line, with scarcely a break, until his death; and the manufacturing plant that he founded is to-day the largest of its kind. Thus, it is no more than an exact statement of the truth to say that he did more than any other member of the human race to abolish the famine of the cities and the drudgery of the farm—to feed the hungry and straighten the bent backs of the world.

IN 1831 Cyrus McCormick had his Reaper, but the great world knew nothing of it. None of the 850 papers that were being printed at this time in the United States had given the notice of its birth. There was the young inventor, with the one machine that the human race most needed, in a remote cleft of the Virginian mountains, four days' journey from Richmond, and wholly without any experience or money or influence that would enable him to announce what he had done.

He had such a problem to solve as no inventor of to-day or to-morrow can have. He was not living, as we are, in an age of faith and optimism—when every new invention is welcomed with a shout of joy. He confronted a sceptical and slow-moving little world, so different from that of to-day that it requires a few lines of portrayal.

In general, it was a non-inventive and hand-labor world. There were few factories, except[49] for the weaving of cotton and woollen cloth. There was no sewing-machine, nor Bessemer converter, nor Hoe press, nor telegraph, nor photography. It was still the age of the tallow candle and stage-coach and tinder-box. Practically no such thing was known as farm machinery. Jethro Wood had invented his iron plow, but he was at this time dying in poverty, never having been able to persuade farmers to abandon their plows of wood. As for steel plows, no one in any country had conceived of such a thing. James Oliver was a bare-footed school-boy in Scotland and John Deere was a young blacksmith in Vermont. Plows were pulled by oxen and horses, not by slaves, as in certain regions of Asia; but almost every other sort of farm work was done by hand.

Railways were few and of little account. Eighty-two miles of flimsy track had been built in the United States; the Baltimore and Ohio was making a solemn experiment with locomotives, horses, and sails, to ascertain which one of these three was the best method of propulsion. The first really successful American locomotive[50] was put on the rails in this year; and Professor Joseph Henry set up his trial telegraph wire and gave the electric current its first lesson in obedience.

There was no free library in the world in 1831. The first one was started in Peterborough, N. H., two years later. In England, electoral reform had not begun, a General Fast had been ordered because of the prevalence of cholera, and a four-pound loaf cost more than the day's pay of a laborer. The United States was a twenty-four-State republic, with very little knowledge of two-thirds of its own territory. The source of the Mississippi River, for instance, was unknown. To send a letter from Boston to New York cost the price of half a bushel of wheat. There was no newspaper in Wisconsin and no house in Iowa. The first sale of lots was announced in Chicago, but there was then no public building in that hamlet, nothing but a few log cabins in a swampy waste that was populous only in wild ducks, bears, and wolves. Forty of the latter were shot by the villagers in 1834.

Of the many eminent men who had the same[51] birth-year as McCormick, Poe and Mendelssohn had begun to be known as men of genius in 1831. But Lincoln was then "a sort of clerk" in a village store. Darwin was setting out on H. M. S. Beagle upon his first voyage as a naturalist. Gladstone was a student at Oxford. Proudhon was working at the case as a poor printer. Oliver Wendell Holmes was somewhat aimlessly studying law. Chopin was on his way to Paris. Tennyson had left college, without a degree, to devote his life to the service of poetry. Three great men who had been born earlier, Garrison, Whittier, and Mazzini, began their life-work in 1831. And science was a babe in the cradle. Herbert Spencer, Virchow and Pasteur were learning the multiplication table. Huxley was six and Bertheiot four.

There was no Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska, California, nor Texas. Virginia was the main wheat State. Local famines were of yearly occurrence. The period between 1816 and 1820 had been one of severe depression and was bitterly referred to as the "1800-and-starve-to-death" period. Seventy-five thousand people[52] had been imprisoned for debt in New York in a single year, and a workingmen's party had sprung up as a protest against such intolerable conditions. Even as late as 1837 there was a bread riot in the city of New York. Five thousand hungry rioters broke into the warehouse of Eli Hart & Company, and destroyed a great quantity of flour and wheat. Five hundred barrels of flour were thrown from the windows; and women and children gathered it up greedily from the dirty gutter where it fell.

So the world that confronted Cyrus McCormick was not a friendly world of science and invention and prosperity. It was slow and dull and largely hostile to whoever would teach it a better way of working. And we shall now see by what means McCormick compelled it to accept his Reaper, and to give him the credit and pay for his invention.

He was resolved from the first not to be robbed and flung aside as most inventors had been. Whitney, the inventor of the cotton-gin, had said in 1812: "The whole amount I have received is not equal to the value of the labor saved[53] in one hour by my machines now in use." Fulton had died at fifty, plagued and plundered by imitators. Kay, Jacquard, Heathcoat, and Hargreaves, inventors of weaving machinery, were mobbed. Arkwright's mill was burned by incendiaries. Gutenberg, Cort, and Jethro Wood lost their fortunes. Palissy was thrown into the Bastile. And Goodyear, who gave us rubber, Bottgher, who gave us Sèvres porcelain, and Sauvage, who gave us the screw propeller, died in poverty and neglect.

But Cyrus McCormick was more than an inventor. He was a business-builder. In the same resolute, deliberate way in which he had made his Reaper, he now set to work to make a business. He planned and figured and made experiments. "His whole soul was wrapped up in his Reaper," said one of the neighbors. Once while riding home on horseback in the Summer of 1832, his horse stopped to drink in the centre of a stream, and as he looked out upon the fields of yellow grain, shimmering in the sunlight, the dazzling thought flashed upon his brain, "Perhaps I may make a million dollars from this[54] Reaper." As he said in a letter written in later years: "This thought was so enormous that it seemed like a dream-like dwelling in the clouds—so remote, so unattainable, so exalted, so visionary."

His first step was seemingly a mistake, though it must have contributed much toward the development of self-reliance and hardihood in his own character. He received a tract of land from his father, and proceeded with might and main to farm it alone. There was a small log house on his land, and here he lived with two aged negro servants and his Reaper.

He needed money to buy iron—to advertise—to appoint agents. And he had no means of earning money except by farming.

It is very evident that he had not set aside his purpose to make Reapers, for we find in the Lexington Union of September 28, 1833, the first advertisement of his machine. He offers Reapers for sale at $50.00 apiece, and gives four testimonials from farmers. But nothing came of this advertisement. No farmer came[55] forward to buy. The four men who had given testimonials had only seen the Reaper at work. They were not purchasers. McCormick was "a voice crying in the wilderness" for nine years before he found a farmer who had the money and the courage to buy one of his Reapers.

After living for more than a year on his farm, McCormick saw that as a means of raising money it was a failure. It had given him a most valuable period of preparatory solitude, but it had not helped him to launch the Reaper; so he looked about him for some enterprise that would yield a larger profit. There was a large deposit of iron ore near by, and he resolved to build a furnace and make iron. Iron was the most expensive item in the making of a reaper. At that time it was $50.00 a ton—two and a half cents a pound. So as he had been unable to establish the Reaper business with a farm, he now set out to do it with a furnace. He persuaded his father and the school teacher to become his partners; and they built the furnace and were making their first iron in 1835—the[56] same year, by the way, in which a babe named Andrew Carnegie was born in the little Scotch town of Dunfermline.

For several years the furnace did fairly well. It swallowed the ore and charcoal and limestone, and poured into the channelled sand little sputtering streams of fiery metal. Cyrus made the patterns for the moulds, and, because of his great strength, did much of the heaviest labor. But the work was so incessant that he had no time to build Reapers. And in 1839, when the effects of the 1837 panic were felt in the more remote regions of Virginia, Cyrus McCormick realized to the full the aptness of that couplet of Hudibras—

The price of iron fell; debtors were unable to pay; the school teacher signed over his property to his mother; and the whole burden of the inevitable bankruptcy fell upon the McCormicks. Cyrus gave up his farm to the creditors, and whatever other property he had that was saleable. He did not give up the Reaper, and[57] nobody would have taken it if he had. Thus far, he had made no progress towards the building of a Reaper business. Instead of being the owner of a million, or any part of a million, he was eight years older than when he had begun to seek his fortune, and penniless.

In this hour of debt and defeat Cyrus became the leader of the family. Here for the first time he showed that indomitable spirit which was, more than any other one thing, the secret of his success. At once he did what he had not felt was possible before—he began to make Reapers. Without money, without credit, without customers, he founded the first of the world's reaper factories in the little log workshop near his father's house. In the year of the iron failure, 1839, he gave a public exhibition on the farm of Joshua Smith, near the town of Staunton. With two men and a team of horses he cut two acres of wheat an hour. At this there was great applause, but no buyers.

The farmers of that day were not accustomed to the use of machinery. Their farm tools, for the most part, were so simple as to be made[58] either by themselves or by the village blacksmith. That the Reaper did the work of ten men, they could not deny. But it was driven by an expert. "It's all very wonderful, but I'm running a farm, not a circus," thought the average spectator at these exhibitions. Also, there was in all Eastern States at that time a surplus of labor and a scarcity of money, both of which tended to retard the adoption of the Reaper.

Neither did the business men of Staunton pay any serious attention to it. There was a Samson Eager at that time who made wagons, a David Gilkerson who made furniture, a Jacob Kurtz who made spinning wheels, and an Absalom Brooks who made harness. But none of these men saw any fortune in the making of Reapers, and Staunton lost its great opportunity to be a manufacturing centre.

Failure was being heaped on failure, yet Cyrus McCormick hung to his Reaper as John Knox had to his Bible. He went back to the little log workshop with a fighting hope in his[59] heart, and hammered away to make a still better machine.

This was the darkest period in the history of the McCormicks—from 1837 to 1840. Once a constable named John Newton rode up to the farm-house door with a summons, calling Cyrus and his father before the County Judge on account of a debt of $19.01. A teamster named John Brains had brought suit. His bill had been $72.00 and he had been paid more than three-fourths of the money. But the constable was so impressed with the honesty and industry of the McCormicks, that he rode back to town without having served the summons. A little later, Mr. John Brains received his money; and it may be said that had he accepted, instead, a five per cent interest in the Reaper, he would have become in twenty years or less one of the richest men in the county.

As it happened, not one of Cyrus McCormick's creditors thought of such an idea as seizing the Reaper, or the patent, which had been secured in 1834. If the queer-looking[60] machine, which was regarded as part marvel and part freak, had been put up to auction in that neighborhood of farmers, very likely it would have found no bidders. There appeared to be one man only, a William Massie, who appreciated the ability of Cyrus McCormick and lent him sums of money on various urgent occasions.

But in 1840 a stranger rode from the north and drew rein in front of the little log workshop. In appearance he was a rough-looking man, but to Cyrus he was an angel of light. He had come to buy a Reaper. He had been one of the spectators at the Staunton exhibition, and he had resolved to risk $50 on one of the new machines. His name, which deserves to be recorded in the annals of the Reaper, was Abraham Smith.

Several weeks later came two other angels in disguise—farmers who had heard of the Reaper and who had ridden from their homes on the James River, a forty-mile journey on horseback through the Blue Ridge Mountains. These men had never seen a Reaper, but they had[61] faith. They were notable men. Both ordered machines, and Cyrus McCormick accepted one of the orders only, as he was not satisfied with the way his Reaper worked in grain that was wet. It was apt to clog in the grooves that held the blade. Even in this darkest and most debt-ridden period of his life, McCormick was much more intent, apparently, upon making his Reapers work well than upon winning a fortune.

Almost breathlessly, the young inventor waited for the next harvest. This was the unique difficulty of his task, that he had only a few weeks once a year to try out his machine and to improve it. He had now sold two, so that there were three Reapers clicking through the grain-fields in the Summer of 1840. They failed to operate evenly. Where the grain was dry, they cut well; but where it was damp, they clogged and at times refused to cut at all.

Wet grain! This, after nine years of arduous labor, still remained a stubborn obstacle to the success of the Reaper. It was especially hard to overcome, because in that primitive[62] neighborhood McCormick could not secure the best workmanship in the making of the cutting-blade. However, this obstacle did not daunt him. He gave his blade a more serrated edge, and to his delight it cut down the wet grain very nearly as neatly as the dry.

This success had cost him another year, for he sold no machines in 1841. But he had now, at least, a wholly satisfactory Reaper. Fortified with a testimonial from Abraham Smith, he fixed the price at $100 and became a salesman. By great persistence he sold seven Reapers in 1842, twenty-nine in 1843, and fifty in 1844. At last, after thirteen years of struggle and defeat, Cyrus McCormick had succeeded; and the home farm was transformed into a busy and triumphant Reaper factory.

There were new obstacles, of course. A few buyers failed to pay. Four machines were held on loitering canal-boats until they were too late for the harvest. There was strong opposition in several places by day laborers. A trusted workman who was sent out to collect $300 ran away with both horse and money.[63] But none of these trifles moved the victorious McCormick. The great stubborn world was about to surrender, and he knew it.

By 1844 he had done more than sell machines. He had made converts. One enthusiastic farmer named James M. Hite, who had made a world's record in 1843 by cutting 175 acres of wheat in less than eight days, was the first of these apostles of the Reaper. "My Reaper has more than paid for itself in one harvest," he said; and he gave $1,333 for the right to sell Reapers in eight counties. Closely after this man came Colonel Tutwiler, who agreed to pay $2,500 for the right to sell in southern Virginia. And a manufacturer in Richmond, J. Parker, bought an agency in five counties for $500; and won the renown of being the first business man who appreciated the Reaper. All this money was not paid in at once. Some of it was never paid. But after thirteen years of struggle and debt, this was Big Business.

Best of all, orders for seven Reapers had come from the West. Two farmers in Tennessee and one each in Wisconsin, Missouri, Iowa,[64] Illinois, and Ohio, had written to McCormick for "Virginia Reapers," as they were called in the farm papers of that day. These seven letters, as may be imagined, brought great joy and satisfaction to the McCormick family, which was now, under the leadership of Cyrus, devoting its best energies to the making of Reapers. The Reapers were made and then, when the question of their transportation arose, Cyrus for the first time saw clearly that the Virginia farm was not the best site for a factory. To get the seven Reapers to the West, they had first to be carried in wagons to Scottsville, then by canal to Richmond, re-shipped down the James River to the Atlantic Ocean and around Florida to New Orleans, transferred here to a river boat that went up the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers to Cincinnati, and from Cincinnati in various directions to the expectant farmers. Four of these Reapers arrived too late for the harvest of 1844, and two of them were not paid for. Clearly, something must be done to supply the Western farmers more efficiently.

At this time a friend said to him, "Cyrus,[65] why don't you go West with your Reaper, where the land is level and labor is scarce?" His mind was ripe for this idea. It was the call of the West. So one morning he put $300 into his belt and set off on a 3,000-mile journey to establish the empire of the Reaper. Up through Pennsylvania he rode by stage to Lake Ontario, then westward through Ohio, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Missouri.

For the first time he saw the prairies. So vast, so flat, so fertile, these boundless plains amazed him. And he was quick to see that this great land ocean was the natural home of the Reaper. Virginia might, but the West must, accept his new machine.

Already the West was in desperate need of a quicker way to cut grain. As McCormick rode through Illinois, he saw the most convincing argument in favor of his Reaper. He saw hogs and cattle turned into fields of ripe wheat, for lack of laborers to gather it in. The fertile soil had given Illinois five million bushels of wheat, and it was too much. It was more than the sickle and the scythe could cut. Men[66] toiled and sweltered to save the yellow affluence from destruction. They worked by day and by night; and their wives and children worked. But the tragic aspect of the grain crop is this—it must be gathered quickly or it breaks down and decays. It will not wait. The harvest season lasts from four to ten days only. And whoever cannot snatch his grain from the field during this short period must lose it.

Truly, the West needed the Reaper; and McCormick's first plan was to overcome the transportation obstacle by selling licenses to many manufacturers in many States. By 1846 he had, with herculean energy, started Fitch & Company and Seymour, Morgan & Company in Brockport, N. Y., Henry Bear in Missouri, Gray & Warner in Illinois, and A. C. Brown in Cincinnati. These manufacturers, and the McCormick family in Virginia, built 190 Reapers for the harvest of 1846. This was multiplying the business by four, very nearly, but the plan was not satisfactory. Some manufacturers used poor materials; some had unskilled workmen; and one became[67] so absorbed in new experiments that when the harvest time arrived, his machines were not completed.

The new difficulty was not to get manufacturers to make Reapers, but to get them to make good Reapers. What was to be done? The thought of having defective Reapers scattered among the farmers was intolerable to Cyrus McCormick. He pondered deeply over the whole situation. He considered the fact that the supremacy in wheat was slowly passing from Virginia to Ohio. He took note of the railroads that were creeping westward. He remembered the limitless prairies, far out in the sunset country, that were still uncultivated. Plainly, he must make Reapers in a factory of his own, so as to have them made well, and he must locate that factory as near as possible to the prairies, at some point along the Great Lakes. With the most painstaking diligence he studied the map and finally he put his finger upon a town—a small new town, which bore the strange name of Chicago.

OF all the cities that Cyrus McCormick had seen in his 3,000-mile journey, Chicago was unquestionably the youngest, the ugliest, and the most forlorn. It lacked the comforts of ordinary life, and many of the necessities. For the most part, it was the residuum of a broken land boom; and most of its citizens were remaining in the hope that they might persuade some incoming stranger to buy them out.

The little community, which had absurdly been called a city ten years before, had at this time barely ten thousand people—as many as are now employed by a couple of its department stores. It was exhausted by a desperate struggle with mud, dust, floods, droughts, cholera, debt, panics, broken banks, and a slump in land values. Other cities ridiculed its ambitions and called it a mudhole. Its harbor, into which six small schooners ventured in 1847, was obstructed by a sand-bar. And the entire region,[69] for miles back from the lake, was a dismal swamp—the natural home of frogs, wild ducks, and beavers.

The six years between 1837 and 1843 had been to Illinois a period of the deepest discouragement. There was little or no money that any one could accept with confidence. Trade was on a barter basis. The State was hopelessly in debt. It had borrowed $14,000,000 in the enthusiasm of its first land boom, and now had no money to pay the interest. Even as late as 1846 there was only $9,000 in the State treasury.

Buffalo was at this time the chief grain market of the United States. We were selling a little wheat to foreign countries—much less than is grown to-day in Oklahoma. Hulled corn was the staff of life in Iowa. The Mormons had just started from Illinois on their 1,500-mile pilgrimage to the West, through a country that had not a road, a village, a bridge, nor a well. The sewing-machine had recently been invented by Howe, and the use of ether had been announced by Dr. Morton; but there was no Hoe press, nor Bessemer steel, nor even so much as a[70] postage stamp. And in the Old World the two most impressive figures, perhaps, were Livingstone, the missionary, who was groping his way to the heart of the Dark Continent, and DeLesseps, the master-builder of canals, who was now cutting a channel through the hot sand at Suez.

In Chicago, there was at this time no Board of Trade. The first wheat had been exported nine years before—as much as would load an ordinary wagon. There was no paved street, except one short block of wooden paving. The houses were rickety, unpainted frame shanties, which had not even the dignity of being numbered. There was a school, a jail, a police force of six, a theatre, and a fire-engine. But there was no railroad, nor telegraph, nor gas, nor sewer, nor stock-yards. The only post-office was a little frame shack on Clark Street, with one window and one clerk; and one of the lesser hardships of the citizens was to stand in line here on rainy days.

Prosperity was still an elusive hope in 1847, but the spirit of depression was being overcome.[71] The Federal bankrupt law of 1842 had broken the deadlock, and the Legislature had passed several "Hard Times" measures for the relief of debtors. To such an extent had the little community recovered its confidence that it opened a new theatre, welcomed its first circus, founded a law-school, launched a new daily paper called the Tribune, and organized a regiment for the Mexican War.