Henry H. Gibson

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See http://archive.org/details/americanforestt00gibs |

Please see Transcriber’s Note at the end of this document.

Henry H. Gibson

BY

HENRY H. GIBSON

Edited by

HU MAXWELL

Hardwood Record

CHICAGO

1913

Copyright 1913 by

HARDWOOD RECORD

Chicago, Ill.

The Regan Printing House

Chicago.

The material on which this volume is based, appeared in Hardwood Record, Chicago, in a series of articles beginning in 1905 and ending in 1913, and descriptive of the forest trees of this country. More than one hundred leading species were included in the series. They constitute the principal sources of lumber for the United States. The present volume includes all the species described in the series of articles, with a large number of less important trees added. Every region of the country is represented; no valuable tree is omitted, and the lists and descriptions are as complete as they can be made in the limited space of a single volume. The purpose held steadily in view has been to make the work practical, simple, plain, and to the point. Trees as they grow in the forest, and wood as it appears at the mill and factory, are described and discussed. Photographs and drawings of trunk and foliage are made to tell as much of the story as possible. The pictures used as illustrations are nearly all from photographs made specially for that purpose. They are a valuable contribution to tree knowledge, because they show forest forms and conditions, and are as true to nature as the camera can make them. Statistics are not given a place in these pages, for it is no part of the plan to show the product and the output of the country’s mills and forests, but rather to describe the source of those products, the trees themselves. However, suggestions for utilization are offered, and the fitness of the various woods for many uses is particularly indicated. The prominent physical properties are described in language as free as possible from technical terms, and yet with painstaking accuracy and clearness. Descriptions intended to aid in identification of trees are given; but simplicity and clearness are held constantly in view, and brevity is carefully studied. The different names of commercial trees in the various localities where they are known, either as standing timber or as lumber in the yard and factory, are included in the descriptions as an assistance in identification. The natural range of the forest trees, and the regions where they abound in commercial quantities, are outlined according to the latest and best authorities. Estimates of present and future supply are offered, where such exist that seem to be authoritative. The trees are given the common and the botanical names recognized as official by the United States Forest Service. This lessens misunderstanding and confusion in the discussion of species whose common names are not the same in different regions, and whose botanical names[4] are not agreed upon among scientific men who mention or describe them. The forests of the United States contain more than five hundred kinds of trees, ranging in size from the California sequoias, which attain diameters of twenty feet or more and heights exceeding two hundred, down to indefinite but very small dimensions. The separating line between trees and shrubs is not determined by size alone. In a general way, shrubs may be considered smaller than trees, but a seedling tree, no matter how small, is not properly called a shrub. It is customary, not only among botanists, but also among persons who do not usually recognize exact scientific terms and distinctions, to apply the name tree to all woody plants which produce naturally in their native habitat one main, erect stem, bearing a definite crown, no matter what size they may attain.

The commercial timbers of this country are divided into two classes, hardwoods and softwoods. The division is for convenience, and is sanctioned by custom, but it is not based on the actual hardness and softness of the different woods. The division has, however, a scientific basis founded on the mechanical structures of the two classes of woods, and there is little disagreement among either those who use forest products or manufacture them, or those who investigate the actual structure of the woods themselves, as to which belong in the hardwood and which in the softwood class.

Softwoods—The needleleaf species, represented by pines, hemlocks, firs, cedars, cypresses, spruces, larches, sequoias, and yews, are softwoods. The classification of evergreens as softwoods is erroneous, because all softwoods are not evergreen, and all evergreens are not softwoods. Larches and the southern cypress shed their leaves yearly. Most other softwoods drop only a portion of their foliage each season, and enough is always on the branches to make them evergreen. Softwoods are commonly called conebearers, and that description fits most of them, but the cedars and yews produce fruit resembling berries rather than cones. Though the needleleaf species are classed as softwoods, there is much variation in the absolute hardness of the wood produced by different species. The white pines are soft, the yews hard, and the other species range between. If there were no other means of separating trees into classes than tests of actual hardness of wood, the line dividing hardwoods from softwoods might be quite different from that now so universally recognized in this country.

Hardwoods—The broadleaf trees are hardwoods. Most, but not all, shed their foliage yearly. It is, therefore, incorrect to classify deciduous trees as hardwoods, since it is not true in all cases, any more than it is true that softwoods are evergreen. Live oaks and American holly are[5] evergreen, and yet are true hardwoods. In a test of hardness they stand near the top of the list.

There are more species of hardwoods than of softwoods in this country; but the actual quantity of softwood timber in the forests greatly exceeds the hardwoods. Nearly two hundred species of the latter are seldom or never seen in a sawmill, while softwoods are generally cut and used wherever found in accessible situations.

As in the case of needleleaf trees, there is much variation in actual hardness of the wood of different broadleaf species. Some which are classed as hardwoods are softer than some in the softwood list. It is apparent, therefore, that the terms hardwood and softwood are commercial rather than scientific.

Palm, cactus, and other trees of that class are not often employed as lumber, and it is not customary to speak of them as either hardwoods or softwoods.

Sapwood and Heartwood—Practically all mature trees contain two qualities of wood known as sap and heart. The inner portion is the heartwood, the outer the sap. They are usually distinguished by differences of color.

The terms are much used in lumber transactions and are well understood by the trade. The two kinds of wood need be described only in the most general way, and for the guidance and information of those who are not familiar with them. Differences are many and radical in the relative size and appearance of the two kinds of wood in different species, and even between different trees of the same species. No general law is followed, except that the heartwood forms in the interior of the tree, and the sapwood in a band outside, next to the bark. In the majority of cases young trees have little heartwood, often none. It is a development attendant on age, yet age does not always produce it. Some mature trees have no heartwood, others very little.

The two kinds of wood belong to needleleaf and broadleaf trees alike; but palms, owing to their manner of growth, have neither. Their size increases in height rather than in diameter. With palms, the oldest wood is in the base of the trunk, the newest in the top; but in the ordinary timber tree the oldest wood is in the center of the trunk, the youngest in the outside layers next the bark. It is the oldest that becomes heartwood, and it is, of course, in the center of the tree. The band of sapwood is of no certain thickness, but averages much thicker in some species than in others. The sapwood of Osage orange is scarcely half an inch thick, and in loblolly pine it may be six inches or more.

Heartwood is known by its color. The eye can detect no other difference between it and the surrounding band of sapwood. There is[6] no fundamental difference. The heart was once sapwood, and the latter will sometime become heartwood if the tree lives long enough. As the trunk increases in size and years, the wood near the heart dies. It no longer has much to do with the life of the tree, except that it helps support the weight of the trunk. The heartwood is, therefore, deadwood. The activities of tree life are no longer present. The color changes, because mineral and chemical substances are deposited in the wood and fill many of the cavities. That process begins at the center of the trunk and works outward year by year, forming a pretty distinct line between the living sapwood and the dead and inert heartwood.

For some reason, the heartwood of certain species is prone to decay. Sycamore is the best example. The largest trunks are generally hollow. The heart has disappeared, leaving only the thin shell of sapwood, and this is required not only to maintain the tree’s life and activities, but to support the trunk’s weight. In most instances the substances deposited in the heartwood, and associated with the coloring matter, tend to preserve the wood from decay. For that reason heart timber lasts longer than sap when exposed in damp situations. The dark and variegated shades of the heartwood of some species give them their chief value as cabinet and furniture material. The sapwood of black walnut is not wanted by anybody, for it is light in color and is characterless; but when the sap has changed to heart, and its tones have been deepened by the accumulation of pigments, it becomes a choice material for certain purposes. The same is true of many other timbers, notably sweet and yellow birch, black cherry, and several of the oaks.

It sometimes happens that when sapwood is transformed into heart, a physical change, as well as a coloring process, affects it. Persimmon and dogwood are examples, and hickory in a less degree. The sapwood of persimmon and dogwood makes shuttles and golf heads, but after the change to heartwood occurs, it is considered unsuitable. Handle makers and the manufacturers of buggy spokes prefer hickory sapwood, but use the red heartwood if it is the same weight as the sap.

Annual Rings—The trunks of both hardwoods and softwoods are made up of concentric rings. In most instances the eye easily detects them. They are more distinct in a freshly cut trunk than in weathered wood, though in a few instances weathering accentuates rather than obliterates them. A count of the rings gives the tree’s age in years, each ring being the growth of one year. An occasional exception should be noted, as when accident checks the tree’s growth in the middle of the season, and the growth is later resumed. In that case, it may develop two rings in one year. A severe frost late in spring after leaves have started may produce that result; or defoliation by caterpillars in early[7] summer may do it. Perhaps not one tree in a thousand has that experience in the course of its whole life. Trees in the tropics where seasons are nearly the same the year through, seldom have rings. Imitations of mahogany are sometimes detected by noting clearly marked annual rings. It is difficult for the woodfinisher to obliterate the annual rings, but some of the French woodworkers very nearly accomplish it.

No law of growth governs the width of yearly rings, but circumstances have much to do with it. When the tree’s increase in size is rapid, rings are broad. An uncrowded tree in good soil and climate grows much faster than if circumstances are adverse. Carolina poplar and black willow sometimes have rings nearly three-fourths of an inch broad, while in the white bark pine, which grows above the snow line in California, the rings may be so narrow as to be invisible to the naked eye.

There is no average width of yearly rings and no average age of trees. A few (very few) of the sequoias, or “big trees” of California, are two thousand years old. An age of six or seven centuries appears to be about the limit of the oldest of the other species in this country, though an authentic statement to that effect cannot be made. There are species whose life average scarcely exceeds that of men. The aspen generally falls before it is eighty; and fire cherry scarcely averages half of that. Of all the trees cut for lumber, perhaps not one in a hundred has passed the three century mark. That ratio would not hold if applied to the Pacific coast alone.

Spring and Summerwood—These are not usual terms with lumbermen and woodworkers, but belong more to the engineer who thinks of physical properties of timber, particularly its strength. Yet, sawmill and factory men are well acquainted with the two kinds of wood, but they are likely to apply the term “grain” to the combination of the two.

Spring and summerwood make the annual ring. Springwood grows early in the season, summerwood later. In fact, it usually is the contrast in color where the summerwood of one season abuts against the springwood of the next which makes the ring visible. The inside of the ring—that portion nearest the heart of the tree—is the springwood, the rest of the ring is the summerwood. The former is generally lighter in color. Sometimes, and with certain species, the springwood is much broader than the other. The summerwood may be a very narrow band, not much wider than a fine pencil mark, but its deeper color makes it quite distinct in most instances. In other instances, as with some of the oaks, the summerwood is the wider part of the annual ring. The[8] figure or “grain” of southern yellow pine is largely due to the contrast between the dark summerwood and light springwood of the rings. The same is true of ash, chestnut, and of many other woods.

Pores—Wood is not the solid substance it seems to be when seen in the mass. If magnified it appears filled with cavities, not unlike a piece of coral or honeycomb; but to the unaided eye only a few of the largest openings are visible, and in some woods like maple, none can be seen. The large openings are known as pores. They are so prominent in some of the oaks that in a clean cut end or cross section they look like pin holes. Very little magnifying is required to bring them out distinctly. A good reading glass is sufficient.

Pores belong to hardwoods only. The resin ducts in some softwoods present a similar appearance, but are far less numerous. All pores are, of course, situated in the annual rings, but in different species they are differently located as to spring and summerwood. In some woods the largest pores are in the springwood only and therefore run in rings. Such woods are called “ring porous,” and the oaks are best examples. In other species the pores are scattered through all parts of the ring in about the same proportion, and such woods are called “diffuse porous,” as the birches. Softwoods have no pores proper, and are classed “non-porous.”

Medullary Rays—A smoothly-cut cross section of almost any oak, but particularly white oak and red oak, exhibits to the unaided eye narrow, light-colored lines radiating from the center of the tree toward the bark like spokes of a wheel. They are about the breadth of a fine pencil mark, and are generally a sixth of an inch or less apart. They are among the most conspicuous and characteristic features of oak wood, and are known as medullary or pith rays.

Oak is cited as an example because the rays are large and prominent, but they are present in all wood, and constitute a large part of its body. They vary greatly in size. In some woods a few are visible unmagnified; but even in oak a hundred are invisible to the naked eye to one that can be seen. Some species show none until a glass is used. Some pines have fifteen thousand to a square inch of cross section, all of which are so small as to elude successfully the closest search of the unaided eye.

The medullary rays influence the appearance of most wood. They determine its character. Oak is quarter-sawed for the purpose of bringing out the bright, flat surfaces of these rays. The prominent flecks, streaks, and patches of silvery wood are the flat sides of medullary rays. In cross section, only the line-like ends are seen, but quarter-sawing exposes their sides to view.

That explains in part why some species are adapted to quarter-sawing and others are not. If no broad rays exist in the wood, as with white pine, red cedar, and cottonwood, quarter-sawing cannot add much to the wood’s appearance.

Grain—The grain of wood is not a definite quality. The word does not mean the same thing to all who use it. It sometimes refers to rings of yearly growth, and in that sense a narrow-ringed wood is fine grained, and one with wide rings is coarse grained. A curly, wavy, smoky, or birdseye wood does not owe its quality to annual rings, yet with some persons, all of these figures are called grain. The term sometimes refers to medullary rays, again to hardness, or to roughness. Some mahogany is called “woolly grained” because the surface polishes with difficulty. The pattern maker designates white pine as “even grained”, because it cuts easily in all directions. The handle maker classes hickory as “smooth grained”, because it polishes well and the sole idea of the maker is smoothness to the touch. There are other grains almost as numerous as the trades which use wood. In numerous instances “figure” is a better term than “grain.” Feather mahogany, birdseye birch, burl ash, are figures rather than grains. There is no authority to settle and decide what the real meaning of grain is in wood technology. It has a number of meanings, and one man has as much authority as another to interpret it in accordance with his own ideas, and the usage in his trade. It is a loose term which covers several things in general and nothing in particular.

Weight—The weight of wood is calculated from different standpoints. It has a green weight, an air-dry weight, a kiln-dry weight, and an oven-dry weight. All are different, but the differences are due to the relative amounts of water weighed. Sawlogs generally go by green weight; yard lumber by air-dry or partly air-dry weight; while the wood used in ultimate manufacture, such as furniture, is supposed to be kiln-dry.

The absolute weight of wood, with all air spaces, moisture, and other foreign material removed, is about 100 pounds per cubic foot, which is 1.6 times heavier than water; but that is not a natural form of wood. It is known only in the laboratory.

The actual wood substance of one species weighs about the same as another. Dispense with all air spaces, all water, and all other foreign substance, and pine and ebony weigh alike. It is apparent that the different weights of woods, as between cedar and oak for example, are due chiefly to porosity. The smaller the aggregate space occupied by pores and other cavities, the heavier the wood. That accounts for the differences in weights of absolutely dry woods of different kinds, except[10] that a small amount of other foreign material may remain after water has been driven off. Florida black ironwood is rated as the heaviest in the United States, and it weighs 81.14 pounds per cubic foot, oven-dry. The lightest in this country is the golden fig which is a native of Florida also. It weighs 16.3 pounds per cubic foot, oven-dry. When weights of wood are given, the specimen is understood to be oven-dry, unless it is stated to be otherwise: it is a laboratory weight, calculated from small cubes of the wood. Such weights are always a little less than that of the dryest wood of the same kind that can be obtained in the lumber market.

Moisture in Wood—The varying weights of the same wood indicate that moisture plays an important part. No man ever saw absolutely dry wood. If heated sufficiently to drive off all the moisture, the wood is reduced to charcoal and other products of destructive distillation.

The pores and other cavities in green timber are more or less filled with water or sap. This may amount to one-third, one-half, or even more, of the dry weight of the wood. The water is in the hollow vessels and cell walls. A living tree contains about the same quantity of water in winter as in summer, though the common belief is otherwise. It is misleading to say that the sap is “down” in one season and “up” in another, although there is more activity at certain times than in others. Strictly speaking, there is a difference between the water in a tree, and the tree’s sap; but in common parlance they are considered identical. What takes place is this: water rises from the tree’s roots, through the wood, carrying certain minerals in solution. Some of it reaches the leaves in summer where it mixes with certain gases from the air, and is converted into sap proper. Most of the surplus water, after giving up the mineral substance held in solution, is evaporated through the leaves into the air; but the sap, starting from the leaves which act as laboratories for its manufacture, goes down through the newly-formed (and forming), layer of wood just beneath the bark, and is converted into wood. This newly-formed wood is colorless at first. It builds up the annual ring, first the springwood very rapidly, and then the summerwood more slowly.

The force which causes water to rise through the trunk of a tree is not fully understood. It is one of nature’s mysteries which is yet to be solved. Forces known as root pressure, capillary attraction, and osmosis, are believed to be active in the process, but there seems to be something additional, and no man has yet been able to explain what it is.

The seasoning of wood is the process of getting rid of some of the water. As soon as lumber is exposed to air, the water begins to escape.[11] Long exposure to dry air takes out a large percentage of the moisture which green wood holds, and the lumber is known as air-dry. But some of the original moisture remains, and air at climatic temperature is unable to expel it. The greater heat of a drykiln drives away some more of it, but a quantity yet remains. The lumber is then kiln-dry. Greater heat than the drykiln’s is secured in an oven, and a little more of the wood’s moisture is expelled; but the only method of driving all the moisture out is to heat the wood sufficiently to break down its structure, and reduce it to charcoal.

Wood warps in the process of drying unless it seasons equally on all sides. It curls or bends toward the side which dries most rapidly. Dry wood may warp if exposed to dampness, if one side is more exposed and receives more moisture than another. It curls or bends toward the dryer side.

Warping is primarily due to the more rapid contraction or expansion of wood cells on one side of the piece than on the other. Saturated cells are larger than dry ones.

Moisture in wood affects its strength, the dryer the stronger, at least within certain limits. Architects and builders carefully study the seasoning of timber, because it is a most important factor in their business. The moisture which most affects a wood’s strength is that absorbed in the cell walls, rather than that contained in the cell cavities themselves.

Some woods check or split badly in seasoning unless attended with constant care. Checking is due chiefly to lack of uniformity in seasoning. One part of the stick dries faster than another, the dryer fibers contract, and the pull splits the wood. The checks may be small, even microscopic, or they may develop yawning cracks such as sometimes appear in the ends of hickory and black walnut logs. Greenwood checks worse in summer than in winter, because the weather is warmer, the wood’s surface dries faster, and the strain on the fibers is greater. Phases of the moon have no influence on the seasoning, checking, warping, or lasting properties of timber.

Stiffness, Elasticity, and Strength—Rules for measuring the stiffness of timber are involved in mathematical formulas; but the practical quality of stiffness is not difficult to understand. Wood which does not bend easily is stiff. If it springs back to its original position after the removal of the force which bends it, the wood is elastic. The greatest load it can sustain without breaking, is the measure of its strength. The load required to produce a certain amount of bending is the measure of its stiffness. Flexibility, a term much used by certain classes of workers in wood, is the opposite of stiffness. A brittle wood is not necessarily[12] weak. It may sustain a heavy load without breaking, but when it fails, the break is sudden and complete. A tough wood behaves differently, though it may not be as strong as a brittle one. When a tough wood breaks, the parts are inclined to adhere after they have ceased to sustain the load. Hickory is tough, and in breaking, the wood crushes and splinters. Mesquite is brittle, and a clean snap severs the stick at once.

Builders of houses and bridges, and the manufacturers of articles of wood, study with the greatest care the stiffness, elasticity, strength, toughness, and brittleness of timber. Its chief value may depend upon the presence or absence of one or more of these properties. Take away hickory’s toughness and elasticity and it would cease to be a great vehicle and handle material. Reduce the stiffness and strength of longleaf pine and Douglas fir and they would drop at once from the high esteem in which they are held as structural timbers. Destroy the brittleness of red cedar and it would lose one of the chief qualities which make it the leading lead pencil wood of the world.

There are recognized methods of measuring these important physical properties of woods, but they are expressed in language so technical that it means little to persons who are not specialists. For ordinary purposes, it is unnecessary to be more explicit than to state a certain wood is or is not strong, stiff, tough and elastic. Some species possess one or more of these properties to double the degree that others possess them. Different trees of the same species differ greatly, and even different parts of the same tree. Most tables of figures which show the various physical properties of woods, give averages only, not absolute values.

Hardness—In some woods hardness is considered an advantage, but not in others. If sugar maple were as soft as white pine, it would not be the great floor material it is; and if white pine were as hard as maple, pattern makers would not want it, door and sash manufacturers would get along with less, and it would not be the leading packing box material in so wide a region.

It is generally the summer growth in the annual rings which makes a wood hard. The summerwood is dense. A given bulk of it contains more actual wood substance and less air and water than the springwood. For the same reason, summerwood gives weight, and a relationship between hardness and weight holds generally. It may be added that strength goes with weight and hardness, but it is not a rule without apparent exceptions.

Some woods possess twice or three times the hardness of others. Among some of the hardest in the United States are hickory, sugar maple, mesquite, the Florida ironwoods, Osage orange, locust, persimmon,[13] and the best oak and elm. Among the softest species are buckeye, basswood, cedar, redwood, some of the pines, spruce, hemlock, and chestnut.

The hardness of wood is tested with a machine which records the pressure required to indent the surface. The condition of the specimen, as to dryness, has much to do with its hardness. So many other factors exercise influence that nothing less than an actual test will determine the hardness of a sample. A table of figures can show it only approximately and by averages.

Cleavability—Wood users generally demand a material which does not split easily, but the reverse is sometimes required. Rived staves must come from timbers which split easily. Many handles are from billets which are split in rough form and are afterwards dressed to the required size and shape. In these instances, splitting is preferable to sawing, because a rived billet is free from cross grain.

The cleavability of woods differs greatly. Some can scarcely be split. Black gum is in that list, and sycamore to a less extent. Young trees of some species split more readily than old, while with others, the advantage is with the old. Young sycamore may generally be split with ease, but old trunks seem to develop interlocked fibers which defy the wedge. A white oak pole is hard to split, but the old tree yields readily. Few woods are more easily split than chestnut. With most timbers cleavage is easiest along the radial lines, that is, from the heart to the bark. The flat sides of the medullary rays lie in that plane. Cleavage along tangential lines is easy with some woods. The line of cleavage follows the soft springwood. Green timber is generally, but not always, more easily split than dry. As a rule, the more elastic a wood is, the more readily it may be split.

Durability—In Egypt where climatic conditions are highly favorable, Lebanon cedar, North African acacia, East African persimmon, and oriental sycamore have remained sound during three or four thousand years. In the moist forests of the northwestern Pacific coast, an alder log six or eight inches in diameter will decay through and through in a single year. No wood is immune to decay if exposed to influences which induce it, but some resist for long periods. Osage orange and locust fence posts may stand half a century. Timber from which air is excluded, as when deeply buried in wet earth or under water, will last indefinitely; but if it is exposed to alternate dampness and dryness, decay will destroy it in a few years.

It is apparent that resistance to decay is not a property inherent in the wood, but depends on circumstances. However, the ability to resist decay varies greatly with different species, under similar circumstances.[14] Buckeye and red cedar fence posts, situated alike, will not last alike. The buckeye may be expected to fall in two or three years, and the cedar will stand twenty. Timbers light in weight and light in color are, as a class, quick-decaying when exposed to the weather.

The rule holds in most cases that sapwood decays more quickly than heart when both are subject to similar exposure. The matter of decay is not important when lumber and other products intended for use are in dry situations. Furniture and interior house finish do not decay under ordinary circumstances, no matter what the species of wood may be; but resistance to decay overshadows almost any other consideration in choosing mine timbers, crossties, fence posts, and tanks and silos.

Decay in timber is not simply a chemical process, but is due primarily to the activities of a low order of plants known as fungi, sometimes bacteria. The fungi produce thread-like filaments which penetrate the body of the wood, ramifying in and passing from cell to cell, absorbing certain materials therein, and ultimately breaking down and destroying the structure of the wood. Both air and dampness are essential to the growth of fungus. That is the reason why timbers deep beneath ground or water do not decay. Air is absent, though moisture is abundant; while in the dry Egyptian tombs, air is abundant but moisture is wanting, fungus cannot exist, and consequently decay of the wood does not occur. Nothing is needed to render timber immune to decay except to keep fungus out of the cells. Some of the fungus concerned in wood rotting is microscopic, while other appears in forms and sizes easily seen and recognized.

Timber may be protected for a time against the agencies of decay by covering the surface with paint, thereby preventing the entrance of fungus. By another process, certain oils or other materials which are poisonous to the insinuating threads of fungus, are forced into the pores of the wood. Creosote is often used for this purpose. Attacks are thus warded off, and decay is hindered. The preservative fluid will not remain permanently in wood exposed to weather conditions, but the period during which it affords protection and immunity extends over some years; but different woods vary greatly in their ability to receive and retain preservative mixtures.

The better seasoned, the less liable is timber to decay, because it contains less moisture to support fungi. It is generally supposed that timber cut in the fall of the year is less subject to decay than if felled in summer. If it is so, the reason for it lies in the fact that fungus is inactive during winter, and before the coming of warm weather the timber has partly dried near the surface, and fungi cannot pass through the dry outside to reach the interior. Timber cut in warm weather may be[15] attacked at once, and before cold weather stops the activities of fungus it has reached the interior of the wood and the process of rotting is under way. When the agents of decay have begun to grow in the wood, destruction will go on as long as air and moisture conditions are favorable.

The bluing of wood is an incipient decay and is generally due to fungus. Some kinds of wood are more susceptible to bluing than others. Though boards may quickly season sufficiently to put a stop to the bluing process before it has actually weakened the material, the result is more or less injurious. The wood’s natural color and luster undergo deterioration; it does not reflect light as formerly, and seems dead and flat.

Decay affects sapwood more readily than heart. The reason may be that sapwood contains more food for fungus, thereby inducing greater activity. The sapwood is on the outside of timbers and is often more exposed than the heart. In some instances greater decay may be due to greater exposure. Another reason for more rapid decay of sapwood than heart is the fact that the pores of the heartwood are more or less filled with coloring matter deposited while the growth of the tree was in progress. The coloring matter, in many cases, acts as a preservative; it shuts the threads of fungus out. Sometimes the sapwood of a dead tree or a log is totally destroyed while the heart remains sound. This often happens with red cedar and sometimes with black walnut, yellow poplar, and cherry. Occasionally a tree’s bark is more resistant to decay than its wood. Paper birch and yellow birch logs in damp situations occasionally show this. What appears to be a solid fallen trunk, proves to be nothing more than a shell of bark with a soft, pulpy mass of decayed wood within.

[1] The following 12 species are usually classed soft pines: White Pine (Pinus strobus); Sugar Pine (Pinus lambertiana); Western White Pine (Pinus monticola); Mexican White Pine (Pinus strobiformis); Limber Pine (Pinus flexilis); Whitebark Pine (Pinus albicaulis); Foxtail Pine (Pinus balfouriana); Parry Pine (Pinus quadrifolia); Mexican Pinon (Pinus cembroides); Pinon (Pinus edulis); Singleleaf Pinon (Pinus monophylla); Bristlecone Pine (Pinus aristata).

The best known wood of the United States has never been burdened with a multitude of names, as many minor species have. It is commonly known as white pine in every region where it grows, and in many where the living tree is never seen, except when planted for ornament. The light color of the wood suggests the name. The bark and the foliage are of somber hue, though not as dark as hemlock and many of the pines. The name Weymouth pine is occasionally heard, but it is more used in books than by lumbermen. It is commonly supposed that the name refers to Lord Weymouth who interested himself in the tree at an early period, but this has been disputed. In Pennsylvania it is occasionally called soft pine to distinguish it from the harder and inferior pitch pine and table mountain pine with which it is sometimes associated. It is the softest of the pines, and the name is not inappropriate. In some regions of the South, where it is well known, it is called northern spruce pine in recognition of the fact that it is a northern species which has followed the Appalachian mountain ranges some hundreds of miles southward. There is no good reason for this name when applied to white pine. It should be remembered, however, that no less than a dozen tree species in the United States are sometimes called spruce pine. Cork pine is a trade name applied more frequently to the wood than to the living tree. It is the wood of old, mature, first class trunks, as nearly perfect as can be found. Pumpkin pine is another name given to the same class of wood. It is so named because the grain is homogeneous, like a pumpkin, and may be readily cut and carved in any direction. It is the ideal wood for the pattern maker, but it is now hard to get because the venerable white pines, many hundred years old, are practically gone.

The northern limit of the range of white pine stretches from Newfoundland to Manitoba, more than 1800 miles east and west across the Dominion of Canada, and southward to northern Georgia, 1200 miles in a north and south direction. But white pine does not grow in all parts of the territory thus delimited. It attained magnificent[20] development in certain large regions before lumbering began, and in others it was scarce or totally wanting. Its ability to maintain itself on land too thin for vigorous hardwood growth gave it a monopoly of enormous stretches of sandy country, particularly in the Lake States. It occupied large areas in New England and southern Canada; developed splendid stands in New York and Pennsylvania; and it covered certain mountains and uplands southward along the mountain ranges across Maryland, West Virginia, and the elevated regions two or three hundred miles farther south.

A dozen or more varieties of white pine have been developed under cultivation, but they interest the nurseryman, not the lumberman. In all the wide extension of its range, and during all past time, nature was never able to develop a single variety of white pine which departed from the typical species. For that reason it is one of the most interesting objects of study in the tree kingdom. True, the white pine in the southern mountains differs slightly from the northern tree, but botanically it is the same. Its wood is a little heavier, its branches are more resinous and consequently adhere a longer time to the trunk after they die, resulting in lumber with more knots. The southern wood is more tinged with red, the knots are redder and usually sounder than in the North.

It is unfortunately necessary in speaking of white pine forests to use the past tense, for most of the primeval stands have disappeared. The range is as extensive as ever, because wherever a forest once grew, a few trees remain; but the merchantable timber has been cut in most regions. The tree bears winged seeds which quickly scatter over vacant spaces, and new growth would long ago, in most cases, have taken the place of the old, had not fires persistently destroyed the seedlings. In parts of New England where fire protection is afforded, dense stands of white pine are coming on, and in numerous instances profitable lumber operations are carried on in second growth forests. That condition does not exist generally in white pine regions. Primeval stands were seldom absolutely pure, but sometimes, in bodies of thousands of acres, there was little but white pine. Generally hardwoods or other softwoods grew with the pine. At its best, it is the largest pine of the United States, except the sugar pine of California. The largest trees grew in New England where diameters of six or more feet and heights exceeding 200 feet were found. A diameter of four and five feet and a height of 150 feet are about the size limits in the Lake States and the southern mountains. Trees two or three feet through and ninety and 120 tall are a fair average for mature timber.

The wood of white pine is among the lightest of the commercial[21] timbers of this country, and among the softest. While it is not strong, it compares favorably, weight for weight, with most others. It is of rather rapid growth, and the rings of annual increase are clearly defined, and they contain comparatively few resin ducts. For that reason it may be classed as a close, compact wood. It polishes well, may be cut with great ease, and after it is seasoned it holds its form better than most woods. That property fits it admirably for doors and sash and for backing of veneer, where a little warping or twisting would do much harm.

The medullary rays are numerous but are too small to be easily seen separately, and do not figure much in the appearance of the wood. The resin passages are few and small, but the wood contains enough resin to give it a characteristic odor, which is not usually considered injurious to merchandise shipped in pine boxes. The white color of the wood gives it much of its value. Though rather weak, white pine is stiff, rather low in elasticity, is practically wanting in toughness, has little figure, and when exposed to alternate dryness and dampness it is rated poor in lasting properties; yet shingles and weather boarding of this wood have been known to stand half a century. The sapwood is lighter in color than the heart, and decays more quickly.

As long as white pine was abundant it surpassed all other woods of this country in the amount used. It was one of the earliest exports from New England, and it went to the West Indies and to Europe. England attempted to control the cutting and export of white pine, but was unsuccessful. At an early period the rivers were utilized for transporting the logs and the lumber to market, and that method has continued until the present time. Spectacular log drives were common in early times in New England, later in New York and Pennsylvania, and still later in Michigan and the other Lake States. Many billions of feet of faultless logs have gone down flooded rivers. The scenes in the woods and the life in lumber camps have been written in novels and romances, and the central figure of it all was white pine.

There are a few things for which this wood is not suitable; otherwise its use has been nearly universal in some parts of this country. It went into masts and matches, which are the largest and smallest commodities, and into almost every shape and size of product between. Most of the early houses and barns in the pine region were built of it. Hewed pine was the foundation, and the shingles were of split and shaved pine. It formed floors, doors, sash, and shutters. It was the ceiling within and the weather boarding without. It fenced the fields and bridged the streams. It went to market as rough lumber, and planing mills turned it out as dressed stock in various forms. It has probably[22] been more extensively employed by box makers than any other wood, and though it is scarcer than formerly, hundreds of millions of feet of it are still used annually by box makers. Scores of millions of feet yearly are demanded by the manufacturers of window shade rollers, though individually the roller is a very small commodity. In this, as for patterns and many other things, no satisfactory substitute for white pine has been found.

As a timber tree, it will not disappear from this country, though the days of its greatest importance are past. Enormous tracts where it once grew will apparently never again produce a white pine sawlog. The prospect is more encouraging in other regions, and there will always be a considerable quantity of this lumber in the American market, though the high percentage of good grades which prevailed in the past will not continue in the future.

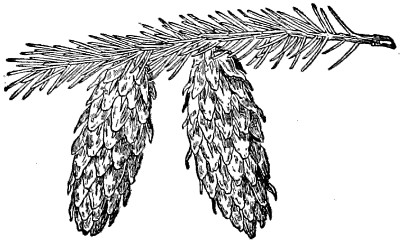

White pine belongs in the five needle group, that is, five leaves grow in a bundle. They turn yellow and fall in the autumn of the second year. The cones are slender, are from five to eleven inches in length, and ripen and disperse their seeds in the autumn of the second year.

The silvery luster of the needles of this tree gives it the name silver pine, by which many people know it. It appears in literature as mountain Weymouth pine, the reference being to the eastern white pine (Pinus strobus), which is sometimes called Weymouth pine. Finger-cone pine is a California name; so are mountain pine and soft pine. In the same state it is called little sugar pine, to distinguish it from sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana), which it resembles in some particulars but not in all. It is thus seen that California is generous in bestowing names on this tree, notwithstanding it is not abundant in any part of that state and is unknown in most parts.

The botanical name means “mountain pine,” and that describes the species. It does best among the mountains, and it ranges from an altitude of from 4,000 feet to 10,000 on the Sierra Nevada mountains. Sometimes trees of very large size are found near the upper limits of its range, but the best stands are in valleys and on slopes at lower altitudes. Its range lies in British Columbia, Montana, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, and California. In the latter state it follows the Sierra Nevada mountains southward to the San Joaquin river.

This species has been compared with the white pine of the East oftener than with any other species. The weights of the two woods are nearly the same, and both are light. Their fuel values are about the same. The strength of the eastern tree is a little higher, but the western species is stiffer. The woods of both are light in color, but that of the eastern tree is whiter; both are soft, but again the advantage is with the eastern tree. The western pine generally grows rapidly and the annual rings are wide; but, like most other species, it varies in its rate of growth, and trunks are found with narrow rings. The summerwood is thin, not conspicuous, and slightly resinous. The small resin passages are numerous. The heartwood is fairly durable in contact with the soil.

The western white pine has entered many markets in recent years, but it is difficult to determine what the annual cut is. Statistics often include this species and the western yellow pine under one name, or at least confuse one with the other, and there is no way to determine exactly how much of the sawmill output belongs to each. The bulk of merchantable western white pine lumber is cut in Idaho and Montana. The stands are seldom pure, but this species frequently predominates over its associates. When pure forests are found, the yield is sometimes[26] very high, as much as 130,000 feet of logs growing on a single acre. That quantity is not often equalled by any other forest tree, though redwood and Douglas fir sometimes go considerably above it.

The western white pine’s needles grow in clusters of five and are from one and a half to four inches long. The cones are from ten to eighteen inches long. The seeds ripen the second year. Reproduction is vigorous and the forest stands are holding their own. Trees about one hundred and seventy-five feet high and eight feet in diameter are met with, but the average size is one hundred feet high and from two to three feet in diameter, or about the size of eastern white pine.

The wood is useful and has been giving service since the settlement of the country began, fifty or more years ago. Choice trunks were split for shakes or shingles, but the wood is inferior in splitting qualities to either eastern white pine or California sugar pine, because of more knots. The western white pine does not prime itself early or well. Dead limbs adhere to the trunk long after the sugar pine would shed them. In split products, the western white pine’s principal rival has been the western red cedar. The pine has been much employed for mine timbers in the region where it is abundant. Miners generally take the most convenient wood for props, stulls, and lagging. A little higher use for pine is found among the mines, where is it made into tanks, flumes, sluice boxes, water pipes, riffle blocks, rockers, and guides for stamp mills. However, the total quantity used by miners is comparatively small. Much more goes to ranches for fences and buildings. It is serviceable, and is shipped outside the immediate region of production and is marketed in the plains states east of the Rocky Mountains, where it is excellent fence material.

A larger market is found in manufacturing centers farther east. Western white pine is shipped to Chicago where it is manufactured into doors, sash, and interior finish, in competition with all other woods in that market. It is said to be of frequent occurrence that the very pine which is shipped in its rough form out of the Rocky Mountain region goes back finished as doors and sash. When the mountain regions shall have better manufacturing facilities, this will not occur. In the manufacture of window and hothouse sash, glass is more important than wood, although each is useless without the other. The principal glass factories are in the East, and it is sometimes desirable to ship the wood to the glass factory, have the sash made there, and the glazing done; and the finished sash, ready for use, may go back to the source of the timber.

The same operation is sometimes repeated for doors; but in recent years the mountain region where this pine grows has been supplied[27] with factories and there is now less shipping of raw material out and of finished products back than formerly. The development of the fruit industry in the elevated valleys of Idaho, Montana, Washington, and Oregon has called for shipping boxes in large numbers, and western white pine has been found an ideal wood for that use. It is light in weight and in color, strong enough to satisfy all ordinary requirements, and cheap enough to bring it within reach of orchardists. It meets with lively competition from a number of other woods which grow abundantly in the region, but it holds its ground and takes its share of the business.

Estimates of the total stand of western white pine among its native mountains have not been published, but the quantity is known to be large. It is a difficult species to estimate because it is scattered widely, large, pure stands being scarce. Some large mills make a specialty of sawing this species. The annual output is believed to reach 150,000,000 feet, most of which is in Idaho and Montana.

Mexican White Pine (Pinus strobiformis) is not sufficiently abundant to be of much importance in the United States. The best of it is south of the international boundary in Mexico, but the species extends into New Mexico and Arizona where it is most abundant at altitudes of from 6,000 to 8,000 feet. The growth is generally scattering, and the trunks are often deformed through fire injury, and are inclined to be limby and of poor form. The best trees are from eighty to one hundred feet high, and two in diameter; but many are scarcely half that size. The lumbermen of the region, who cut Mexican white pine, are inclined to place low value on it, not because the wood is of poor quality, but because it is scarce. It is generally sent to market with western yellow pine. Excellent grades and quality of this wood are shipped into the United States from Mexico, but not in large amounts. An occasional carload reaches door and sash factories in Texas, and woodworkers as far east as Michigan are acquainted with it, through trials and experiments which they have made. It is highly recommended by those who have tried it. Some consider it as soft, as easy to work, and as free from warping and checking as the eastern white pine. In Arizona and New Mexico the tree is known as ayacahuite pine, white pine, and Arizona white pine. The wood is moderately light, fairly strong, rather stiff, of slow growth, and the bands of summerwood are comparatively broad. The resin passages are few and large. The wood is light red, the sapwood whiter. The leaves occur in clusters of five, are three or four inches long, and fall during the third and fourth years. The seeds are large and have small wings which cannot carry them far from the parent tree.

Pinon (Pinus edulis). This is one of the nut pines abounding among the western mountains, and it is called pinon in Texas, nut pine in Texas and Colorado, pinon pine and New Mexican pinon in other parts of its range, extending from Colorado through New Mexico to western Texas. It has two and three leaves to the cluster. They begin to fall the third year and continue through six or seven years following. The cones are quite small, the largest not exceeding one and one-half inches in length. Trees are from thirty to forty feet high, and large trunks may be two and one-half feet in diameter. The tree runs up mountain sides to altitudes of 8,000 or 9,000 feet. It exists in rather large bodies, but is not an important timber tree, because the trunks are short and are generally of poor form. It often branches near the ground and assumes the appearance of a large shrub. Ties of pinon have been used with various results. Some have proved satisfactory, others have proved weak by breaking, and the ties occasionally split when spikes are driven. The wood’s service as posts varies also. Some posts will last only three or four years, while others remain sound a long time. The difference in lasting properties is due to the difference in resinous contents of the wood. Few softwoods rank above it in fuel value, and much is cut in some localities. Large areas have been totally stripped for fuel. Charcoal for local smithies is burned from this pine. The wood is widely used for ranch purposes, but not in large quantities. The edible nuts are sought by birds, rodents, and Indians. Some stores keep the nuts for sale. The tree is handicapped in its effort at reproduction by weight, and the small wing power of the seeds. They fall near the base of the parent tree, and most of them are speedily devoured.

This is the largest pine of the United States, and probably is the largest true pine in the world. Its rival, the Kauri pine of New Zealand, is not a pine according to the classification of botanists; and that leaves the sugar pine supreme, as far as the world has been explored. David Douglas, the first to describe the species, reported a tree eighteen feet in diameter and 245 feet high, in southern Oregon. No tree of similar size has been reported since; but trunks six, ten, and even twelve feet through, and more than 200 high are not rare.

The range of sugar pine extends from southern Oregon to lower California. Through California it follows the Sierra Nevada mountains in a comparatively narrow belt. In Oregon it descends within 1,000 feet of sea level, but the lower limit of its range gradually rises as it follows the mountains southward, until in southern California it is 8,000 or 10,000 feet above the sea. Its choice of situation is in the mountain belt where the annual precipitation is forty inches or more. The deep winter snows of the Sierras do not hurt it. The young trees bear abundant limbs covering the trunks nearly or quite to the ground, and are of perfect conical shape. When they are ten or fifteen feet tall they may be entirely covered in snow which accumulates to a depth of a dozen feet or more. The little pines are seldom injured by the load, but their limbs shed the snow until it covers the highest twig. The consequence is that a crooked sugar pine trunk is seldom seen, though a considerable part of the tree’s youth may have been spent under tons of snow. Later in life the lower limbs die and drop, leaving clean boles which assure abundance of clear lumber in the years to come.

The tree is nearly always known as sugar pine, though it may be called big pine or great pine to distinguish it from firs, cedars, and other softwoods with which it is associated. The name is due to a product resembling sugar which exudes from the heartwood when the tree has been injured by fires, and which dries in white, brittle excrescences on the surface. Its taste is sweet, with a suggestion of pitch which is not unpleasant. The principle has been named “pinite.”

The needles of sugar pine are in clusters of five and are about four inches long. They are deciduous the second and third years. The cones are longer than cones of any other pine of this country but those of the Coulter pine are a little heavier. Extreme length of 22 inches for the sugar pine cone has been recorded, but the average is from 12 to 15 inches. Cones open, shed their seeds the second year, and fall the third.[32] The seeds resemble lentils, and are provided with wings which carry them several hundred feet, if wind is favorable. This affords excellent opportunities for reproduction; but there is an offset in the sweetness of the seeds which are prized for food by birds, beasts and creeping things from the Piute Indian down to the Douglas squirrel and the jumping mouse.

Sugar pine occupies a high place as a timber tree. It has been in use for half a century. The cut in 1900 was 52,000,000 feet, in 1904 it was 120,000,000; in 1907, 115,000,000, and the next year about 100,000,000. Ninety-three per cent of the cut is in California, the rest in Oregon. Its stand in California has been estimated at 25,000,000,000 feet.

The wood of sugar pine is a little lighter than eastern white pine, is a little weaker, and has less stiffness. It is soft, the rings of growth are wide, the bands of summerwood thin and resinous; the resin passages are numerous and very large, the medullary rays numerous and obscure. The heart is light brown, the sapwood nearly white.

Sugar pine and redwood were the two early roofing woods in California, and both are still much used for that purpose. Sugar pine was made into sawed shingles and split shakes. The shingle is a mill product; but the shake was rived with mallet and frow, and in the years when it was the great roofing material in central and eastern California, the shake makers camped by twos in the forest, lived principally on bacon and red beans, and split out from 200,000 to 400,000 shakes as a summer’s work. The winter snows drove the workers from the mountains, with from eight to twelve hundred dollars in their pockets for the season’s work.

The increase in stumpage price has practically killed the shake maker’s business. In the palmy days when most everything went, he procured his timber for little or nothing. He sometimes failed to find the surveyor’s lines, particularly if there happened to be a fine sugar pine just across on a government quarter section. His method of operation was wasteful. He used only the best of the tree. If the grain happened to twist the fraction of an inch, he abandoned the fallen trunk, and cut another. The shakes were split very thin, for sugar pine is among the most cleavable woods of this country. Four or five good trees provided the shake maker’s camp with material for a year’s work.

Some of the earliest sawmills in California cut sugar pine for sheds, shacks, sluiceboxes, flumes among the mines; and almost immediately a demand came from the agricultural and stock districts for lumber. From that day until the present time the sugar pine mills have been busy. As the demand has grown, the facilities for meeting it have increased. The prevailing size of the timber forbade the use of small[33] mills. A saw large enough for most eastern and southern timbers would not slab a sugar pine log. From four to six feet were common sizes, and the lumberman despised anything small.

In late years sugar pine operators have looked beyond the local markets, and have been sending their lumber to practically every state in the Union, except probably the extreme South. It comes in direct competition with the white pine of New England and the Lake States. The two woods have many points of resemblance. The white pine would probably have lost no markets to the California wood if the best grades could still be had at moderate prices; but most of the white pine region has been stripped of its best timber, and the resulting scarcity in the high grades has been, in part, made good by sugar pine. Some manufacturers of doors and frames claim that sugar pine is more satisfactory than white pine, because of better behavior under climatic changes. It is said to shrink, swell, and warp less than the eastern wood.

Sugar pine has displaced white pine to a very small extent only, in comparison with the field still held by the eastern wood, whose annual output is about thirty times that of the California species. Their uses are practically the same except that only the good grades of sugar pine go east, and the corresponding grades of white pine west, and therefore there is no competition between the poor grades of the two woods. The annual demand for sugar and white pine east of the Rocky Mountains is probably represented as an average in Illinois, where 2,000,000 feet of the former and 175,000,000 of the latter are used yearly.

While there is a large amount of mature sugar pine ready for lumbermen, the prospect of future supplies from new growth is not entirely satisfactory. The western yellow pine is mixed with it throughout most of its range, and is more than a match for it in taking possession of vacant ground. It is inferred from this fact that the relative positions of the two species in future forests will change at the expense of sugar pine. It endures shade when small, and this enables it to obtain a start among other species; but as it increases in size it becomes intolerant of shade, and if it does not receive abundance of light it will not grow. A forest fire is nearly certain to kill the small sugar pines, but old trunks are protected by their thick bark. Few species have fewer natural enemies. Very small trees are occasionally attacked by mistletoe (Arceuthobium occidentale) and succumb or else are stunted in their growth.

Mexican Pinon (Pinus cembroides) is known also as nut pine, pinon pine and stone-seed Mexican pinon. It is one of the smallest of the native pines of this country. The tree is fifteen or twenty feet high and a few inches in diameter, but in sheltered canyons in Arizona it sometimes attains a height of fifty or sixty feet with[34] a corresponding diameter. It reaches its best development in northern Mexico and what is found of it in the United States is the species’ extreme northern extension, in Arizona and New Mexico at altitudes usually above 6,000 feet. It supplies fuel in districts where firewood is otherwise scarce, and it has a small place as ranch timber. The wood is heavy, of slow growth, the summerwood thin and dense. The resin passages are few and small; color, light, clear yellow, the sapwood nearly white. If the tree stood in regions well-forested with commercial species, it would possess little or no value; but where wood is scarce, it has considerable value. The hardshell nuts resemble those of the gray pine, but are considered more valuable for food. They are not of much importance in the United States, but in Mexico where the trees are more abundant and the population denser, the nuts are bought and sold in large quantities. Its leaves are in clusters of three, sometimes two. They are one inch or more in length, and fall the third and fourth years. Cones are seldom over two inches in length. The species is not extending its range, but seems to be holding the ground it already has. It bears abundance of seeds, but not one in ten thousand germinates and becomes a mature tree.

This interesting and peculiar pine has a number of names, most of which are descriptive. The whiteness of the bark and the stunted and recumbent position which the tree assumes on bleak mountains are referred to in the names whitestem pine in California and Montana, scrub pine in Montana, whitebark in Oregon, white in California, and elsewhere it is creeping pine, whitebark pine, and alpine whitebark pine. It is a mountain tree. There are few heights within its range which it cannot reach. Its tough, prostrate branches, in its loftiest situations, may whip snow banks nine or ten months of the year, and for the two or three months of summer every starry night deposits its sprinkle of frost upon the flowers or cones of this persistent tree. It stands the storms of centuries, and lives on, though the whole period of its existence is a battle for life under adverse circumstances. At lower altitudes it fares better but does not live longer than on the most sterile peak. Its range covers 500,000 square miles, but only in scattered groups. It touches the high places only, creeping down to altitudes of 5,000 or 6,000 feet in the northern Rocky Mountains. It grows from British Columbia to southern California, and is found in Montana, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, Nevada, Arizona, and California. Its associates are the mountain climbers of the tree kingdom, Engelmann spruce, Lyall larch, limber pine, alpine fir, foxtail pine, Rocky Mountain juniper, knobcone pine, and western juniper. Its dark green needles, stout and rigid, are from one and one-half to two and one-half inches long. They hang on the twigs from five to eight years. In July the scarlet flowers appear, forming a beautiful contrast with the white bark and the green needles. In August the seeds are ripe. The cones are from one and one-half to three inches long. The seeds are nearly half an inch long, sweet to the taste. The few squirrels and birds which inhabit the inhospitable region where the whitebark pine grows, get busy the moment the cones open, and few escape. Nature seems to have played a prank on this pine by giving wings to the seeds and rendering their use impossible. The wing is stuck fast with resin to the cone scales, and the seed can escape only by tearing its wing off. The heavy nut then falls plumb to the ground beneath the branches of its parent. It might be supposed that a tree situated as the whitebark pine is would be provided with ample means of seedflight in order to afford wide distribution, and give opportunity to survive the hardships which are imposed by surroundings; but such is not the case. The willow and the cottonwood[38] which grow in fertile valleys have the means of scattering their seeds miles away; but this bleak mountain tree must drop its seeds on the rocks beneath. In this instance, nature seems more interested in depositing the pine nuts where the hungry squirrels can get them, than in furnishing a planting place for the nuts themselves—therefore, tears off their wings before they leave the cone. The battle for existence begins before the seeds germinate, and the struggle never ceases. The tree, in parts of its range, survives a temperature sixty degrees below zero. Its seedlings frequently perish, not from cold and drought, but because the wind thrashes them against the rocks which wear them to pieces. Trees which survive on the great heights are apt to assume strange and fantastic forms, with less resemblance to trees than to great, green spiders sprawling over the rocks. Trees 500 years old may not be five feet high. Deep snows hold them flat to the rocks so much of the time that the limbs cannot lift themselves during the few summer days, but grow like vines. The growth is so exceedingly slow that the new wood on the tips of twigs at the end of summer is a mere point of yellow. John Muir, with a magnifying glass, counted seventy-five annual rings in a twig one-eighth of an inch in diameter. Trunks three and one-half inches in diameter may be 225 years old; one of six inches had 426 rings; while a seventeen-inch trunk was 800 years old, and less than six feet high. Such a tree has a spread of branches thirty or forty feet across. They lie flat on the ground. Wild sheep, deer, bear, and other wild animals know how to shelter themselves beneath the prostrate branches by creeping under; and travelers, overtaken by storms, sometimes do the same; or in good weather the sheepherder or the hunter may spread his blankets on the mass of limbs, boughs, and needles, and spend a comfortable night on a springy couch—actually sleeping in a tree top within two feet of the ground. In regions lower down, the whitebark pine reaches respectable tree form. Fence posts are sometimes cut from it in the Mono basin, east of the Sierra Nevada mountains. In the Nez Perce National Forest trees forty feet high have merchantable lengths of twenty-four feet. Similar growth is found in other regions. In its best growth, the wood of whitebark pine resembles that of white pine. It is light, of about the same strength as white pine, but more brittle. The annual rings are very narrow; the small resin passages are numerous. The sapwood is very thin and is nearly white. Men can never greatly assist or hinder this tree. It will continue to occupy heights and elevated valleys.

Bristlecone Pine (Pinus aristata) owes its name to the sharp bristles on the tips of the cone scales. It is known also as foxtail pine and hickory pine. The latter name is given, not because of toughness,[39] but on account of the whiteness of the sapwood. It is strictly a high mountain tree, running up to the timber line at 12,000 feet, and seldom occurring below 6,000 or 7,000 feet. It maintains its existence under adverse circumstances, its home being on dry, stony ridges, cold and stormy in winter, and subject to excessive drought during the brief growing season. Trees of large trunks and fine forms are impossible under such conditions. The bristlecone pine’s bole is short, tapers rapidly and is excessively knotty. The species reaches its best development in Colorado. Though it is seldom sawed for lumber, it is of much importance in many localities where better material is scarce. In central Nevada many valuable mines were developed and worked by using the wood for props and fuel. Charcoal made of it was particularly important in that region, and it was carried long distances to supply blacksmith shops in mining camps. Railways have made some use of it for ties. Though rough, it is liked for fence posts. The resin in the wood assists in resisting decay, and posts last many years in the dry regions where the tree grows. Ranchmen among the high mountains build corrals, pens, sheds, and fences of it; but the fibers of the wood are so twisted and involved that splitting is nearly impossible, and round timbers only are employed. The bristlecone pine can never be more important in the country’s lumber supply than it is now. It occupies waste land where no other tree grows, and it crowds out nothing better than itself. It clings to stony peaks and wind-swept ridges where the ungainly trunks are welcome to the traveler, miner, or sheepherder who is in need of a shed to shelter him, or a fire for his night camp. In situations exposed to great cold and drying winds, the bristlecone pine is a shrub, with little suggestion of a tree, further than its green foliage and small cones. The needles are in clusters of five. They cling to the twigs for ten or fifteen years. The seeds are scattered about the first of October, and the wind carries them hundreds of feet. They take root in soil so sterile that no humus is visible. Young trees and the small twigs of old ones present a peculiar appearance. The bark is chalky white, but when the trees are old the bark becomes red or brown.

Foxtail Pine (Pinus balfouriana) owes its name to the clustering of its needles round the ends of the branches, bristling like a fox’s tail. The needles are seldom more than one and one-half inches in length, and are in clusters of fives. They cling to the branches ten or fifteen years before falling. The cones are about three inches long, and are armed with slender spines. The tree is strictly a mountain species and grows at a higher altitude than any other tree in the United States, although whitebark pine is not much behind it. It reaches its best development near Mt. Whitney, California, where it is said to grow at an altitude of 15,000 feet above sea level. It has been officially reported at Farewell Gap, in the Sierra Nevada mountains, at an altitude of 13,000. At high altitudes it is scrubby and distorted, but in[40] more favorable situations it may be sixty feet high and two in diameter. On high mountains it is generally not more than thirty feet high and ten inches in diameter. It is of remarkably slow growth, and comparatively small trees may be 200 or 300 years old. The wood is moderately light, is soft, weak, brittle. Resin passages are few and very small. The wood is satiny and susceptible of a good polish, and would be valuable if abundant. The seeds are winged and the wind scatters them widely, but most of them are lost on barren rocks or drifts of eternal snow. The untoward circumstances under which the tree must live prevent generous reproduction. It holds its own but can gain no new foothold on the bleak and barren heights which form its environment. The dark green of its foliage makes the belts of foxtail pines conspicuous where they grow above the timber line of nearly all other trees. Its range is confined to a few of the highest mountains of California, particularly about (but not on) Mt. Shasta and among the clusters of peaks about the sources of Kings and Kern rivers. Those who travel and camp among the highest mountains of California are often indebted to foxtail pine for their fuel. Near the upper limit of its range it frequently dies at the top, and stands stripped of bark for many years. The dead wood, which frequently is not higher above the ground than a man’s head, is broken away by campers for fuel, and it is often the only resource.

Longleaf is generally considered to be the most important member of the group of hard or pitch pines in this country[2]. It is known by many names in different parts of its range, and outside of its range where the wood is well known.

[2] There is no precise agreement as to what should be included in the group of hard pines in the United States, but the following twenty-two are usually placed in that class: Longleaf Pine (Pinus palustris), Shortleaf Pine (Pinus echinata), Loblolly Pine (Pinus tæda), Cuban Pine (Pinus heterophylla), Norway Pine (Pinus resinosa), Western Yellow Pine (Pinus ponderosa), Chihuahua Pine (Pinus chihuahuana), Arizona Pine (Pinus arizonica), Pitch Pine (Pinus rigida), Pond Pine (Pinus serotina), Spruce Pine (Pinus glabra), Monterey Pine (Pinus radiata), Knobcone Pine (Pinus attenuata), Gray Pine (Pinus sabiniana), Coulter Pine (Pinus coulteri), Lodgepole Pine (Pinus contorta), Jack Pine (Pinus divaricata), Scrub Pine (Pinus virginiana), Sand Pine (Pinus clausa), Table Mountain Pine (Pinus pungens), California Swamp Pine (Pinus muricata), Torry Pine (Pinus torreyana).

The names southern pine, Georgia pine, and Florida pine are not well chosen, because there are other important pines in the regions named. Turpentine pine is a common term, but other species produce turpentine also, particularly the Cuban pine. Hard pine is much employed in reference to this tree, and it applies well, but it describes other species also. Heart pine is a lumberman’s term to distinguish this species from loblolly, shortleaf, and Cuban pines. The sapwood of the three last named is thick, the heartwood small, while in longleaf pine the sap is thin, the heart large, hence the name applied by lumbermen. In Tennessee where it is not a commercial forest tree, it is called brown pine, and in nearly all parts of the United States it is spoken of as yellow pine, usually with some adjective as “southern,” “Georgia,” or “longleaf.” The persistency with which Georgia is used as a portion of the name of this tree is due to the fact that extensive lumbering of the longleaf forests began in that state. The center of operations has since shifted to the West, and is now in Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. The tree has many other names, among them being pitch pine and fat pine. These have reference to its value in the naval stores industry. The name longleaf pine is now well established in commercial transactions. It has longer leaves than any other pine in this country. They range in length from eight to eighteen inches. The needles of Cuban pine are from eight to twelve inches; loblolly’s are from six to nine; and those of shortleaf from three to five.

Longleaf pine’s geographic range is more restricted than that of[44] loblolly and shortleaf, but larger than the range of Cuban pine. Longleaf occupies a belt from Virginia to Texas, following the tertiary sandy formation pretty closely. The belt seldom extends from the coast inland more than 125 miles. The tree runs south in Florida to Tampa bay. It disappears as it approaches the Mississippi, but reappears west of that river in Louisiana and Texas. Its western limit is near Trinity river, and its northern in that region is near the boundary between Louisiana and Arkansas.

Longleaf attains a height of from sixty to ninety feet, but a few trees reach 130. The diameters of mature trunks range from one foot to three, usually less than two. The leaves grow three in a bundle, and fall at the end of the second year. They are arranged in thick, broom-like bunches on the ends of the twigs. It is a tree of slow growth compared with other pines of the region. Its characteristic narrow annual rings are usually sufficient to distinguish its logs and lumber from those of other southern yellow pines. Its thin sapwood likewise assists in identification. The proportionately high percentage of heartwood in longleaf pine makes it possible to saw lumber which shows little or no sapwood. It is difficult to do that with other southern pines.

The wood is heavy, exceedingly hard for pine, very strong, tough, compact, durable, resinous, resin passages few, not conspicuous; medullary rays numerous, not conspicuous; color, light red or orange, the thin sapwood nearly white. The annual rings contain a large proportion of dark colored summerwood, which accounts for the great strength of longleaf pine timber. The contrast in color between the springwood and the summerwood is the basis of the figure of this pine which gives it much of its value as an interior finish material, including doors. The hardness of the summerwood provides the wearing qualities of flooring and paving blocks. The coloring matter in the body of the wood protects it against decay for a longer period than most other pines. This, in connection with its hardness and strength, gives it high standing for railroad ties, bridges, trestles, and other structures exposed to weather.