BY

LE VICOMTE HENRI DELABORDE.

TRANSLATED BY

R. A. M. STEVENSON.

With an Additional Chapter on English Engraving

BY

WILLIAM WALKER.

CASSELL & COMPANY, Limited:

LONDON, PARIS, NEW YORK & MELBOURNE.

1886.

[ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.]

The author of "La Gravure," of which work the present volume is a translation, has devoted so little attention to English Engraving, that it has been thought advisable to supplement his somewhat inadequate remarks by a special chapter dealing with this subject.

In accordance with this view, Mr. William Walker has contributed an account of the rise and progress of the British School of Engraving, which, together with his Chronological Table of the better-known English Engravers, will, we feel sure, add much to the value of the Work in the eyes of English readers.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | The Processes of Early Engraving. The Beginnings of Engraving in Relief. Xylography and Printing with Movable Type | 1 |

| II. | Playing Cards. The Dot Manner | 30 |

| III. | First Attempts at Intaglio Engraving. The Nielli of the Florentine Goldsmiths. Prints by the Italian and German Painter-Engravers of the Fifteenth Century | 49 |

| IV. | Line Engraving and Wood Engraving in Germany and Italy in the Sixteenth Century | 86 |

| V. | Line Engraving and Etching in the Low Countries, to the Second Half of the Seventeenth Century | 118 |

| VI. | The Beginning of Line Engraving and Etching in France and England. First Attempts at Mezzotint. A Glance at Engraving in Europe before 1660 | 150viii |

| VII. | French Engravers in the Reign of Louis XIV | 178 |

| VIII. | Engraving in France and in other European Countries in the Eighteenth Century. New Processes: Stipple, Crayon, Colour, and Aquatint | 211 |

| IX. | Engraving in the Nineteenth Century | 248 |

| A Chapter on English Engraving | 287 | |

| Chronological Table of English Engravers | 331 | |

| Index | 343 | |

THE PROCESSES OF EARLY ENGRAVING. THE BEGINNINGS OF ENGRAVING IN RELIEF. XYLOGRAPHY AND PRINTING WITH MOVABLE TYPE.

The nations of antiquity understood and practised engraving, that is to say, the art of representing things by incised outlines on metal, stone, or any other rigid substance. Setting aside even those relics of antiquity in bone or flint which still retain traces of figures drawn with a sharp-pointed tool, there may yet be found in the Bible and in Homer accounts of several works executed by the aid of similar methods; and the characters outlined on the precious stones adorning the breastplate of the high-priest Aaron, or the scenes represented on the armour of Achilles, might be quoted amongst the most ancient examples of the art of engraving. The Egyptians, Greeks, and Etruscans have left us specimens of goldsmith's work and fragments of all kinds, which, at any rate, attest the practice of engraving in their countries. Finally, every one is aware that metal seals and dies of engraved stone were in common use amongst the Romans.

Engraving, therefore, in the strict sense of the2 word, is no invention due to modern civilisation. But many centuries elapsed before man acquired the art of multiplying printed copies from a single original, to which art the name of engraving has been extended, so that nowadays the word signifies the operation of producing a print.

Of engraving thus understood there are two important processes or methods. By the one, strokes are drawn on a flat surface, and afterwards laboriously converted by the engraver into ridges, which, when coated with ink, are printed on the paper in virtue of their projection. By the other, outlines, shadows, and half-tints are represented by incisions intended to contain the colouring matter; while those parts meant to come out white on paper are left untouched. Wood-cutting, or engraving in relief, is an example of the first method; while to the second belongs metal-work or copperplate engraving, which we now call engraving with the burin, or line engraving.

In order to engrave in relief, a block, not less than an inch thick, of hard, smooth wood, such as box or pear, is used. On this block every detail of the design to be engraved is drawn with pen or pencil. Then such places as are meant to come out white in the print are cut away with a sharp tool. Thus, only those places that have been covered beforehand by the pencil or the pen remain at the level of the surface of the block; they only will be inked by the action of the roller; and when the block is subjected to the action of the press, they only will transfer the printing ink to the proof.

3 This method, earlier than that of the incised line, led to engraving "in camaïeu," which was skilfully practised in Italy and Germany during the sixteenth century. As in camaïeu engraving those lines which define the contours are left as ridges by the cutting away of the surrounding surface, we may say that in this method (which the Italians call "chiaroscuro") the usual processes of engraving in relief are employed. But it is a further object of camaïeu to produce on the paper flat tints of various depths: that is to say, a scale of tones somewhat similar to the effect of drawings washed in with Indian ink or sepia, and touched up with white. Now such a chromatic progression can only be arrived at by the co-operation of distinct processes. Therefore, instead of printing from a single surface, separate blocks are employed for the outlines, shadows, and lights, and a proof is taken by the successive application of the paper to all these blocks, which are made to correspond exactly by means of guiding marks.

A third style of engraving in relief, the "early dot manner," was practised for some time during the period of the Incunabuli, when the art was, as the root of this Latin word shows, still "in its cradle." By this method the work was no longer carried out on wood, but on metal; and the engraver, instead of completely hollowing out those parts destined to print light, merely pitted them with minute holes, leaving their bulk in relief. He was content that these masses should appear upon the paper black4 relieved only by the sprinkling of white dots resulting from the hollows.

We just mention by way of note the process which produced those rare specimens called "empreintes en pâte." All specimens of this work are anterior in date to the sixteenth century, and belong less strictly to art than to industry, as the process only consisted in producing on paper embossed designs strongly suggesting the appearance of ornaments in embroidery or tapestry. To produce these inevitably coarse figures a sort of half-liquid, blackish gum or paste was introduced into the hollow portions of the block before printing. On the block thus prepared was placed a sheet of paper, previously stained orange, red, or light yellow, and the paste contained in the hollow places, when lodged on the paper, became a kind of drawing in relief, something like an impasto of dark colour. This was sometimes powdered with a fluffy or metallic dust before the paste had time to harden.

Though simple enough as regards the mere process, in practice line engraving demands a peculiar dexterity. When the outlines of the drawing that is to be copied have been traced and transferred to a plate usually made of copper1 the metal is5 attacked with a sharp tool, called the dry-point. Then the trenches thus marked out are deepened, or fresh ones are made with the graver, which, owing to its shape, produces an angular incision. The appearance of every object represented in the original must be reproduced solely by these incised lines: at different distances apart, or tending in various directions: or by dots and cross-hatchings.

Line engraving possesses no other resources. Moreover, in addition to the difficulties resulting from the use of a refractory tool, we must mention the unavoidable slowness of the work, and the frequent impossibility of correcting faults without having recourse to such drastic remedies as obtaining a fresh surface by re-levelling the plate where the mistakes have been made.

Etching by means of aquafortis, originally used by armourers in their damascene work, is said to have been first applied to the execution of plates in Germany towards the close of the fifteenth century. Since then it has attracted a great many draughtsmen and painters, as it requires only a short apprenticeship, and is the quickest kind of engraving. Line engravers have not only frequently used etching in beginning their plates, but have often employed it, not merely to sketch in their subject, but actually in conjunction with the burin.6 Many important works owe their existence to the mixture of the two processes, among others the fine portraits of Jean Morin, and the admirable "Batailles d'Alexandre," engraved by Gérard Audran, after Lebrun. But at present we are only occupied with etching as practised separately and within the limits of its own resources.

The artist who makes use of this method has to scoop no laborious furrows. He draws with the needle, on a copper plate covered with a coating of varnish, suggestions of form as free as the strokes of pen or pencil. At first these strokes only affect the surface of the copper where the needle has freed the plate from varnish. But they become of the necessary depth as soon as a certain quantity of corrosive fluid has been poured on to the plate, which is surrounded by a sort of wax rampart. For a length of time proportioned to the effect intended, the acid is allowed to bite the exposed parts of the metal, and when the plate is cleaned proofs can be struck off from it.

With the exception of such few modifications as characterise prints in the scraped or scratched manner, called "sgraffio," and in the stippled manner, the methods of engraving just mentioned are all that have been used in Europe from the end of the Middle Ages up to about the second half of the seventeenth century. We need not, therefore, at present mention more recent processes, such as mezzotint, aquatint, &c., each of which we shall touch upon at its proper place in the history of the art. Before7 proceeding with this history, let us try to recollect the facts with which we have prefaced it; and, as chronological order proscribes, to differentiate and classify the first productions of relief engraving.

However formal their differences of opinion on matters of detail, technical writers hold as certain one general fact. They all agree in recognising that the methods of relief engraving were practised with a view to printing earlier than the method of intaglio. What interval, however, separates the two discoveries? At what epoch are we to place the invention of wood engraving? or if the process, as has been often alleged, is of Asiatic origin, when was it brought into Europe? To pretend to give a decisive answer to these questions would be, at least, imprudent. Conjectures of every sort, and even the most dogmatic assertions, are not wanting. But the learned have in vain evoked testimony, interpreted passages, and drawn conclusions. They have gone back to first causes, and questioned the most remote antiquity; they have sometimes strangely forced the meaning of traditions, and have too often confounded simple material accidents with the evidences of conscious art properly so called. Yet the problem is as far from solution as ever, and, indeed, the number and diversity of opinions have up till now done little but render conviction more difficult and doubt more excusable.

Our authorities, for instance, are not justified in connecting the succession of modern engravers with those men who, "even before the Deluge, engraved8 on trees the history of their times, their sciences, and their religion."2 Nor is the mention by Plutarch of a certain almost typographical trick of Agesilaus, King of Sparta, excuse enough for those who have counted him among the precursors of Gutenberg. It is by no means impossible that Agesilaus, in a sacrifice to the gods on the eve of a decisive battle may have been clever enough to deceive his soldiers, by imprinting on the liver of the victim the word "Victory," already written in reverse on the palm of his hand. But in truth such trickery only distantly concerns art; and if we are to consider the Greek hero as the inventor of printing, we must also allow that it has taken us as long as eighteen centuries to profit by his discovery.

We shall therefore consider ourselves entitled to abandon all speculations on the first cause of this discovery in favour of an exclusive attention to such facts as mark an advance from the dim foreshadowing of its future capabilities to the intelligent and persevering practice of the perfected processes of the art. We shall be content to inquire towards what epoch this new method, the heir of popular favour, supplemented the old resources of the graphic arts by the multiplication of engravings in the printing press. And we may therefore spare ourselves the trouble of going back to doubtful or remote information, to archæological speculations, more or less excused by certain passages in Cicero, Quintilian, and Petronius9 or by a frequently quoted phrase of Pliny on the books, ornamented with figures, that belonged to Marcus Varro.3

Moreover in examining the historical question from a comparatively modern epoch only, we are not certain to find for ourselves, still less to provide for others, perfectly satisfactory answers. Reduced even to these terms, such a question is complicated enough to excuse controversy, and vast enough to make room for a legendary as well as a critical view of the case. Xylography, or block printing, which may be called the art of stamping on paper designs and immovable letters cut out on wood, preceded without doubt the invention of printing in movable metal characters. Some specimens authentically dated, such as the "St. Christopher" of 1423, and certain prints published in the course of the following years, prove with undeniable authority the priority of block printing. It remains to be seen if these specimens are absolutely the first engraved in Europe; whether they illustrate the beginning of the art, or only a step in its progress; whether, in one word, they are types without precedent, or only chance survivals of other and more ancient styles of wood engraving.

Papillon, in support of the opinion that the earliest attempts took place at Ravenna before the end of the thirteenth century, brings into court a somewhat doubtful story. Two children of sixteen, the Cavaliere Alberico Cunio and his twin sister10 Isabella, took it into their heads in 1284 to carve on wood "with a little knife," and to print by some process seemingly as simple a series of compositions on "the chivalrous deeds of Alexander the Great." The relations and friends of the two young engravers, Pope Honorius IV. amongst others, each received a copy of their work. After this no more was heard of the discovery till the day when Papillon miraculously came across evidences of it in the library of "a Swiss officer in retirement at Bagneux." Papillon unfortunately was satisfied with merely recording his discovery. It never occurred to him to ensure more conclusive publicity, nor even to inquire into the ultimate fate of the prints he only had seen. The collection of "The Chivalrous Deeds of Alexander the Great" again vanished, and this time not to reappear. It is more prudent, in default of any means of verification, to withhold our belief in the precocious ability of the Ravenna twins, their xylographic attempts, and the assertions of their admirers, although competent judges, such as the Abbé Zani4 and after him Emeric David, have not hesitated to admit the authenticity of the whole story.

The learned Zani had, in truth, his own reasons for taking Papillon at his word. Had the story tended to establish the pre-existence of engraving in Germany, he would probably have investigated the matter more closely, and with a less ready faith. But the glory of Italy was directly at issue, and Zani12 honest though he was, did not feel inclined to receive with coldness, still less to reject, testimony which, for lack of better, might console his national self-respect, and somewhat help to avenge what the Italians called "German vanity." Pride would have been a better word, for the pretensions of Germany with regard to wood engraving are based on more serious titles and far more explicit documents than the one discovered by Papillon, and recklessly passed on by Zani. Heinecken and the other German writers on the subject doubtless criticise in a slightly disdainful manner, and with some excess of patriotic feeling. For all that, they defend their opinions by documents, and not by mere traditions; and if all their examples are not quite evidently German, those which are not should in justice be attributed to Flanders, or to Holland, and by no means to Italy.

In this struggle of rival national claims the schools of the Low Countries are entitled to their share of glory. It is quite possible that their claims, so generally ignored towards the end of the last century, should in the present day be accounted the most valid of all; and that, in this obscure question of priority, the presumption may be in favour of the country which supplied an art closely connected with engraving with its first elements and its first examples. It would be unbecoming in every way to pretend to enter here on a detailed history of the origin of printing. The number of exhaustive works on the subject, the explanations of M. Léon de Laborde, M. Auguste Bernard, and more recently13 of M. Paeile, would render it a mere lesson in repetition or a too easy parade of borrowed learning. Anyhow, the discovery of printing with type is so intimately connected with the printing of engravings, and the practical methods in both are so much alike, that it is necessary to mention a few facts, and to compare a few dates. We shall therefore, under correction, reduce to the limits of a sketch the complete picture drawn by other hands.

If printing be strictly understood to mean typography, or the art of transferring written matter to paper by means of movable and raised metal types, there can be no doubt that its discovery must date from the day on which there was invented at Mayence the process of casting characters in a mould previously stamped in the bottom by a steel die bearing the type to be reproduced.

Gutenberg, with whom the idea of this decisive improvement originated, is in this sense the earliest printer. His "Letters of Indulgence" of 1454 and his "Bible" are the oldest examples of the art with which he is for ever associated. In a general sense, however, and in a wider meaning of the word, it may be said that printing was known before Gutenberg's time, or at least before he published his typographical masterpieces. People previously knew both how to print broadsides from characters cut on a single block, and how to vary the arrangement of the text by using, in place of an immovable row of letters, characters existing as separate types, and capable of various combinations. On this point14 we must trust to the testimony of one of Gutenberg's workmen, Ulrich Zell, the first printer established in Cologne. Far from attributing to his master the absolute invention of movable type, he merely contrasts with the process known and practised in the Low Countries before the second half of the fifteenth century "the far more delicate process" of cast type "that was discovered later." And Ulrich Zell adds, "the first step towards this invention was taken in 1440 in the printing of the copies of Donatus5 which were printed before this time in Holland (ab illis atque ex illis)."

Now if these copies of Donatus were not printed by means of movable type, why should they be mentioned rather than the many other works equally fitted to give a hint to Gutenberg? Why, in going back to the origin of the discovery, should his pupil say nothing of those illustrated legends which were xylographically cut and sold in all the Rhenish towns, and which the future inventor of printing must have seen hundreds of times? For the attention of Gutenberg to have been thus concentrated on a single object, there must have been some peculiar merit and some stamp of real progress in the mode of execution to distinguish the copies of Donatus printed at Haarlem from other contemporary work. Laurence Coster—the name attributed to the inventor of the process which Gutenberg improved—must have already made15 use of a method more closely allied than any other to the improvements about to follow, and destined to put a term to mere experiments.

To suppose the contrary is to misunderstand the words of Ulrich Zell and the influence which he attributes to the Dutch edition of Donatus, from which Gutenberg derived "the first idea of his invention." It is still more difficult to understand how, if the Donatuses are block-printed, reversed letters are sometimes found in the fragmentary specimens which survive. There is nothing the least extraordinary in such a mistake when it can be explained by the carelessness of a compositor of movable type, but such a mistake would really be incredible on the part of a xylographic workman. What possible caprice could have tempted him to engrave occasional letters upside down? One could only suppose he erred, not from inadvertence, but with voluntary infidelity and in calculated defiance of common sense.

The discovery which has immortalised the name of Gutenberg should be recognised and admired as the conclusion and crown of a series of earlier attempts in printed type. Taking into account the inadequacy of the movable type, whether of wood or of any other substance, first employed by the Dutch, and the perfection of the earliest specimens of German printing, it can and should be admitted that, before the publication of the "Letters of Indulgence," the "Bible," and other productions from the workshop of Gutenberg and his fellow-labourers16 attempts at genuine typography had been already pursued, and to a certain extent rewarded with success.

From the very confession of Ulrich Zell, a confession repeated by the anonymous author of the "Chronicle of Cologne" printed in 14996 the first rude essay in the art (prefiguratio) was seen in the town of Haarlem. We may, in short, conclude that the idea of combining designs cut on wood with a separate letterpress in movable types, belongs in all probability to Holland.

One of the oldest collections of engravings with subject matter printed by this process is the "Speculum Humanæ Salvationis," mentioned by Adrian Junius in his "Batavia"—written, it would seem, between the years 1560 and 1570, but not published till 1588, many years after his death. Therein it is expressly stated that the "Speculum" was printed before 1442 by Lourens Janszoon Coster. It is true that Junius is speaking of events which occurred more than a century before the time to which he ascribes them: "on the testimony," as he says, "of very aged men, who had received this tradition, as a burning torch passed from hand to hand." And this belated narrative has appeared, and may still appear, somewhat doubtful. We ourselves consider the doubt to be exaggerated, but we shall not insist on that. The specimens survive which gave rise to such legends17 and commentaries; and it is fitting they should be questioned.

Four editions of the "Speculum" are known, two in Dutch and two in Latin. It must be understood that we only speak of the editions which have no publishers' names, no dates, nor any sign of the place where they were published: the "Speculum," a sort of Christian handbook, much used in the Low Countries, having been frequently reprinted, with due indication of names and places, during and after the last twenty years of the fifteenth century. The oldest Dutch edition that is dated, the one of 1483, printed by John Veldenaer, reproduces certain engravings which had already embellished the four anonymous editions, with the difference that the plates have been sawn in two to suit the dimensions of a smaller volume. Hence, whatever conjectures may exist as to the date of the first publication, we have, at least, a positive fact: as the original plates only appear in a mutilated state in the copies printed in 1483, it is evident that the four editions where they appear entire are of earlier date. These questions remain:—first, whether they are earlier, too, than the second half of the fifteenth century—earlier, that is, than the time when Gutenberg gave to the world the results of his labour? and second, whether they originated, like the edition of Donatus, in a Dutch workshop?

Doubt seems impossible on the last point. These four editions are all printed with the same cuts, on the same paper made in Brabant, and under the same typographical conditions, with the exception of18 some slight differences in the characters of the two Dutch editions, and the insertion of twenty leaves xylographically printed in one of the two Latin editions. Is it, then, likely, or even possible, that these books belong, as has been supposed, to Germany?

Fig. 2.—THE HOLY VIRGIN AND THE INFANT JESUS.

German Wood Engraving. (Fifteenth Century.)

The thing might, indeed, be possible, were it merely a question of the copies in Latin; but the Dutch ones cannot be supposed to have been published anywhere but in Holland; and the origin of the latter once established, how are we to explain the typographical imperfection of the work if not by ignorance of the process which Gutenberg was to popularise? According to M. Paeile, a competent judge in such a matter7 the letterpress of the Dutch "Speculum" is written in the pure dialect of North Holland, as it was spoken in those parts towards the end of the fourteenth century and the beginning of the fifteenth. Armed, therefore, with but a few particulars as to printing and idiom, it will not be too bold in us to fix the date of publication between the first and second quarters of the fifteenth century. It may be added that the costume of the figures is of the time of Philip the Good; that the taste and style of the drawing suggests the influence of the brothers Van Eyck; and that there is a decided contrast between the typographical imperfection of the text and the excellent quality of the plates. Art, and20 art already well on its way and confident of its powers, is thus seen side by side with an industrial process still in its infancy: a remarkable proof of the advances already accomplished in wood engraving before printing had got beyond the rudimentary period. For our present purpose, this is the chief point, the essential fact to verify.

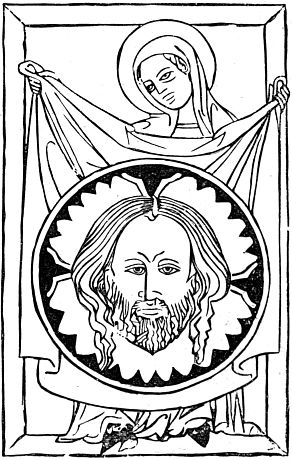

Fig. 3.—ST. VERONICA.

German Wood Engraving. (Fifteenth Century.)

Fig. 4.—ST. JOHN.

Flemish Wood Engraving. (Fifteenth Century.)

22 The discovery of printing, therefore, is doubtless a result of the example of relief engraving, and there is no doubt either that the first attempts at printing with type originated in Holland. Whilst Coster, or the predecessor of Gutenberg, whoever he was, was somewhat feebly preparing the way for typographical industry, painting and the arts of design generally had in the Low Countries attained a degree of development which they had not before reached, except in Italy. Amongst the German contemporaries of Hubert and John van Eyck, what rival was there to compare with these two masters?—what teacher with so notable an influence, or so fertile a teaching? Whilst, on the banks of the Rhine, artists unworthy of the name and painters destitute of talent were continuing the Gothic traditions and the formulæ of their predecessors, the school of Bruges was renewing, or rather founding, a national art. By the beginning of the fifteenth century the revolution was accomplished in this school, which was already distinguished by the Van Eycks, and to which Memling was about to add fresh lustre. Germany, too, in a few years was to glory in a like success; but the movement did not set in till after the second half of the century. Till then everything remained dead, everything betrayed an extreme poverty of method and doctrine. If we judge the German art of the time by such work, for instance, as the "St. Christopher," engraved in 1423, a single glance is sufficient to reveal the marked superiority of the contemporary Flemings. It is, then, far from unnatural24 that, at a time when painters, goldsmiths, and all other artists in Flanders were so plainly superior in skill to their co-workers in Germany, the Flemish engravers should likewise have led the van of progress26 and taken their places as the first in the history of their art.

Fig. 5.—THE INFANT JESUS.

Flemish Wood Engraving. (Fifteenth Century.)

Fig. 6.—JESUS, SAVIOUR OF THE WORLD.

German Wood Engraving. (Fifteenth Century.)

Fig. 7.—THE CRUCIFIXION.

German Wood Engraving. (Fifteenth Century.)

It may be said that the proofs are insufficient. Be it so. We shall not look for them in the "Virgin" on wood, belonging to the Brussels Library, and bearing the date 1418, as the authenticity of this date, to our thinking perfectly genuine, has been disputed; nor shall we seek for them in the anonymous examples which it seems to us but just to ascribe to the old school of the Low Countries.8

Fig. 8.—THE APOCALYPSE OF ST. JOHN.

Dutch Wood Engraving. (Fifteenth Century.)

Up to now we are willing to admit that only Germany is in a position to produce a piece of evidence beyond suspicion. With its imposing date of 1423, its time-honoured rights, and official renown, the "St. Christopher," now in the library of Lord Spencer, has privileges which cannot be disputed or questioned. But it does not follow that the wood-cuts of the "Speculum," of the "Biblia Pauperum," of the "Ars Moriendi," and of similar undated publications, must be more recent. Nor, because a dated German print has survived, must it therefore be concluded that nothing was produced at that time except in27 Germany. It should be particularly observed that the plates of the "Speculum" seem well-nigh prodigies28 of pictorial skill and knowledge in comparison with the "St. Christopher;" that their author must have served a long apprenticeship in a good school; that, in short, no art begins with such a piece of work, and that, even supposing these cuts did not appear till after the German print, some time had doubtless elapsed during which the progress they involve had been prepared and pursued.

It is therefore reasonable to suppose that, from the first years of the fifteenth century, the engravers of the Low Countries began, under the influence of the Van Eycks, to be initiated into the conditions of art, and that, like their countrymen the printers, they showed the path which others were to clear and level. It must be remarked, however, that in the beginning printing and wood engraving do not always march on parallel lines—that they do not meet in like order their successive periods of trial and advance. In Germany, up till the time when Gutenberg attained the final stage, and popularised the last secrets of the printing process, painters, draughtsmen, and engravers were all helpless in a rut: from the author of the "St. Christopher" to the engravers of thirty years later, they boast but the roughest and coarsest of ideas and methods. Heinecken, the exaggerated champion of the German cause as against the partisans of Coster, whom he contemptuously calls "the beadle"9—Heinecken himself, speaking of the first German books engraved on wooden tablets, is29 obliged to admit that "when the drawing is examined with a connoisseur's eye, a heavy and barbarous taste appears to reign throughout."10 In Germany the artistic part was to wait upon and follow the example of the industrial: was to lag behind and to plod on in barbarism long after the industrial revolution was accomplished at its side. And it was long before the "wood-cutting" engravers acquired anything like the skill of the printers employed by Gutenberg and by Füst.

In the Low Countries, on the other hand, the regeneration of art preceded mechanical improvement. Even when the latter was in full progress, nay, even when a grand discovery had revealed all the capabilities and fixed the limits of printing, engraving was by no means subordinated, as in Germany, to the advance of the new process, but, on the contrary, had long since acquired a clearness and certainty of execution which was still lacking in the works of the printers. The "Speculum," as we have said, bears testimony to that sort of anomaly between the mechanical imperfection of the Dutch printed texts of the fifteenth century and the merit of the plates by which they were accompanied. Other examples might be mentioned, but it is useless to multiply evidence, and to insist on details. We shall have accomplished enough if we have succeeded in accentuating some of the principal features, and in summing up the essential characteristics of engraving, at the time of the Incunabuli.

PLAYING CARDS. THE DOT MANNER.

In our endeavour to prove the relative antiquity of wood engraving in the Low Countries, we have intentionally rather deferred the purely archæological question, and have sought the first signs of talent instead of the bold beginnings of the art. The origin of wood engraving, materially considered, cannot be said to be confined to the time and country of the pupils of Van Eyck. It was certainly in their hands that it first began to show signs of being a real art, and give promise for the future; but we have still to inquire how many years it had been practised in Europe, through what phases it had already passed, and to what uses it had been applied, before it took this start and received this consecration.

We treat this question of origin with some reserve, and must repeat as our excuse that savants have pushed their researches so far, and unhappily with such conflicting results, and have found, or have thought they found, in the accounts of travellers, or in ancient official or historical documents, so many proofs and arguments in support of different systems, that it becomes equally difficult to accept or to finally reject their various conclusions. The prevailing31 opinion, however, attributes to the makers of playing cards, if not the discovery of wood engraving, at least its first practical application in Europe. Many writers agree on the general principle, but agreement ends when it comes to be question of the date and place of the earliest attempts. Some pronounce in favour of the fourteenth century and Germany; others plead for France, where they say cards were in use from the beginning of the reign of Philip of Valois. Others again, to support the claims of Italy, arm themselves with a passage quoted by Tiraboschi from the "Trattato del Governo della Famiglia," a work written, according to them, in 1299; and they suppose, besides, that the commercial relations of Japan and China with Venice would have introduced into that town before any other the use of cards and the art of making them.

Emeric David, one of the most recent authorities, carries things with a still higher hand. He begins by setting aside all the claimants—Germany with the Low Countries, France as well as Italy.11 Where playing cards were first used, or whether any particular xylographic collection belongs or not to the first years of the fifteenth century, are matters of extremely small importance in his eyes. In the documents brought forward by competent experts as the most ancient remains of wood engraving, he finds instead a testimony to the uninterrupted practice of the art in Europe. For the real origin the32 author of the "Discours sur la Gravure" does not hesitate to go boldly back beyond the Christian era. Nor does he stop there; but sees in the practice of the Greeks under the successors of Alexander a mere continuance of the traditions of those Asiatic peoples who were accustomed from time immemorial to print on textile fabrics by means of wooden moulds.

It would be too troublesome to discuss his facts or his conclusions; so many examples borrowed from the poets, from the historians of antiquity, and the Fathers of the Church, appear to sustain his perhaps too comprehensive theory. The best and the shortest plan will be to take it upon trust, and to admit on the authority of Homer, Herodotus, Ezekiel, and St. Clement of Alexandria, that from the heroic ages till the early days of Christianity, there has been no break in the practice of printing upon various materials from wooden blocks. Still less need we grudge the Middle Ages the possession of a secret already the common property of so many centuries.

But the printing of textiles does not imply the knowledge and practice of engraving properly so called; and many centuries may have passed without any attempt to use this merely industrial process for finer ends, or to apply it to the purposes of art. Seals with letters cut in relief were smeared with colour and impressed on vellum or paper long before the invention of printing. The small stamps or patterns with which the scribes and illuminators transferred the outlines of capital letters to their manuscripts, might well have suggested the last33 advance. And yet how many years and experiments were required to bring it to perfection! Why may we not suppose that the art of engraving, like the art of printing, in spite of early, partial, and analogous discoveries, may have waited long for its hour of birth? And when block printing was once brought from Asia into Europe, why may it not have suffered the same fate as other inventions equally ingenious in principle and equally limited in their earlier applications? Glass, for instance, was well known by the nations of antiquity; but how long a time elapsed before it was applied to windows?

We have said that according to a generally received opinion we must look upon playing cards as the oldest remains of xylography. But the evidence on which this opinion is based has only a negative authority. Because the old books in which cards are mentioned say nothing of any other productions of wood engraving, it has been inferred that such productions did not yet exist; but is it not allowable to ask if the silence of writers in such a case absolutely establishes such a negative? Might not this silence be explained by the nature of the work, and of the subject treated, which was generally literary or philosophical, and quite independent of questions of art? When speaking of cards, whether to formally forbid or only to restrain their use, the chroniclers and the moralists of the fourteenth century, or of the beginning of the fifteenth, probably thought but little of the way they were made. Their intention was to denounce a vice rather than to describe an industrial process. Why, then34 should they have troubled about other works in which this process was employed, not only without danger to religion and morality, but with a view of honouring both? Pious pictures cut in wood by the hands of monks or artisans might have been well known at this time, although contemporary authors may have chosen to mention only cards; and, without pushing conjecture too far, we may take the liberty of supposing that engravers first drew their inspiration from the same source as illuminators, painters on glass, and sculptors. Besides, we know well that art was then only the naïve expression of religion and the emblem of Christian thought. Why should the cutters of xylographic figures have been an exception to the general rule? and what strange freak would have led them to choose as the subject of their first efforts a species of work so contrary to the manners and traditions of all the schools?

Setting aside written testimony, and consulting the engravings themselves which have been handed down to us from former centuries, we are entitled to say that the very oldest playing cards are, at the most, contemporaneous with the "St. Christopher" of 1423 and the oldest known wood-cuts, inasmuch as the engraving of these cards certainly does not date back beyond the reign of Charles VII. That the Italian, German, or French tarocchi (ornamented chequers or cards) were in use before that time is possible; but as none of these early tarocchi have survived, it cannot be known to what extent they represent the progress of the art, and how far they may have served as models for other35 xylographic works: even though it be true that relief engraving, and not merely drawing with the pen, was the means first employed for the making of the tarocchi mentioned here and there in the chronicles.

Such French cards as have come down to us would lead us to believe, in any case, that the progress was slow enough, for they still reveal an extraordinary want of experience both as to shape and effect, and have all the timidity of an art still in its infancy. This must also be said of works of the same kind executed in Germany in the fifteenth century; except the cards, attributed to a contemporary of the Master of 1466, and these are engraved on metal. In Italy alone, cards, or rather the symbolical pieces known rightly or wrongly by the name of tarocchi, possessed, from an artistic point of view, real importance from the time when engraving on metal had begun to take the place of wood-cutting. The artists initiated by Finiguerra into the secrets of the new method displayed good taste, knowledge, and skill; and in such less important work, as well as in that of a higher order, their talent at last inaugurated an era of real progress and of fruitful enterprise.

It is of no consequence, for the matter of that, whether wood engraving was first applied to the making of pious pictures or to the manufacture of cards. In any case the process is generally looked upon as the oldest method of engraving, and as the first to give types to be multiplied in proofs by printing.

36 M. Léon de Laborde, one of the clearest and best informed writers on the origins of engraving and typography, considers, on the other hand, that engraving in relief on metal, rather than the xylographic process, was the proximate cause of the discovery of printing. In a work published in 1839, which unfortunately has yet to receive the amplifications promised by the author12 M. de Laborde declares that the first printed engravings must have been dotted ones: that is, prints produced in the peculiar mode already touched upon, and in which the black parts come out sprinkled with white dots. According to him, engraving, or, to speak more exactly, the printing of engraved work, must have been invented by goldsmiths rather than by draughtsmen or illuminators. The former, by the nature of their craft, possessed the tools and the necessary materials, and were therefore in a better position than any one else to stumble upon the discovery of the process, if not deliberately to invent it. As matter of fact, many of those who worked in the Low Countries, or in the Rhenish provinces, during the first years of the fifteenth century, printed works in the early dot manner: in other words, engraved in relief on metal. And those xylographic specimens which are usually looked upon as the oldest examples of engraving, are in reality only the outcome of a reformation, and the product of an art already modified.

Fig. 9.—JESUS CHRIST CARRYING THE CROSS.

Engraving in the Dot Manner (1406).

38 The opinion expressed some time ago by M. Léon de Laborde has recently been supported by the discovery of two engravings, in the early dot manner, belonging, we think, to the year 1406, and on which we have ourselves published some remarks.13 But our argument being only founded on the similarity of certain external facts, so to speak, and on the probability of certain calculations, it is not really possible to attribute to these documents so secure a standing as to those whose age is established by dates, and set practically beyond question.

Fig. 10.—THE HOLY FACE.

Engraving in the Dot Manner (1406).

Now, the oldest of the dated engravings in relief on metal is the "St. Bernardino of Siena," wrongly called the "St. Bernard," belonging to the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. This engraving in the dot manner bears the date 1454. It is, therefore, later than the "St. Christopher" engraved on wood, and later even, as we shall presently see, than the first engraving in incised line, the "Pax," by Finiguerra, whose date of printing is certain. Remembering these facts, the separation of the oldest dotted prints from the first specimens of true engraving is only permissible on the ground that they are works executed by a special process. Considered from a purely artistic point of view, they offer little interest. Their drawing, still ruder than that of the German wood-cuts, exhibits an almost hieroglyphic unreality. Their general effect is purely conventional; and, owing to the uniform depth of the40 blacks, their insignificant modelling expresses neither the relief nor the comparative depression of the forms.

Fig. 11.—ST. BERNARDINO.

Engraving in the Dot Manner (1454).

Fig. 12.—ST. CHRISTOPHER.

Engraving in the Dot Manner. (Fifteenth Century.)

In short, we find in these early dotted prints nothing but perfect falseness to nature, and all the mendacity42 inherent in feebleness of taste and slavish conformity to system.

How comes it that this sorry child's-play has appeared to deserve in our day attention which is not always conceded to more serious work? This might be better excused had these prints been investigated in order to demonstrate the principles of the method followed afterwards by the engravers of illustrations for books. The charming borders, for instance, which adorn the "Books of Hours," printed in France at the end of the fifteenth and the beginning of the sixteenth centuries, would naturally suggest comparisons between the way in which many parts are stippled, and the process of the early dotted engraving. But we may surely term excessive the efforts of certain scholars to fix on these defective attempts in a particular method of work the attention of a public naturally attracted elsewhere. The fact is, however, that in this matter, as well as in questions relating to the origin of wood engraving and printing, national self-respect was at stake, and writers sought in the narrow field of archæology a victory over rival claims which they might less easily have achieved on other grounds.

Fig. 13.—JESUS ON THE MOUNT OF OLIVES.

Engraving in the Dot Manner. (Fifteenth Century.)

Between the authors of the Low Countries and of Germany, long accustomed to skirmishes of the kind, this new conflict might have begun and continued without awaking much interest in other nations; but, contrary to custom, these counterclaims originated neither in Germany nor in the Low Countries. For the first time the name of France was43 heard of in a dispute as to the origin of engraving; and though there was but scant honour to be gained, the unforeseen rivalry did not fail to give additional44 interest to the struggle, and, in France at least, to meet with a measure of favour.

The words "Bernhardinus Milnet," deciphered, or supposed to be deciphered, at the bottom of an old dotted engraving, representing "The Virgin and the Infant Jesus," were taken for the signature of a French engraver, and the discovery was turned to further profit by the assumption that the said "Bernard or Bernardin Milnet" engraved all the prints of this particular class; although, even supposing these to belong to a single school, they manifestly could not all belong to a single epoch. The invention and monopoly of dotted engraving once attributed to a single country, or rather to a single man, these assertions continued to gain ground for some time, and were even repeated in literary and historical works. A day, however, came when they began to lose credit; and as doubts entered even the minds of his countrymen, the supposed Bernard Milnet is now deprived of his name and title, and is very properly regarded as an imaginary being.

Does it follow from this, as M. Passavant14 would have it, that all these prints, naturalised for a little while in France, ought to be restored to Germany? Their contradictory character with regard to workmanship and style might cause one, with the most honest intentions, to hesitate, though their intrinsic value is not such as to cause the former country any great loss.

Fig. 14.—ST. GEORGE.

Engraving in the Dot Manner. (Fifteenth Century.)

Fig. 15.—ST. DOMINIC.

Engraving in the Dot Manner. (Fifteenth Century.)

Indeed, it is difficult to conceive of anything less interesting, except with regard to the particular nature of the process. The outlines of the figures have none of that drawing, firm even to stiffness, nor46 has the flow of the draperies that taste for abrupt forms, which distinguished the productions of the German school from its beginnings. The least feeble of these specimens, such as the "Saint Barbara," in the Brussels Library, or the "St. George on Horseback," preserved in the Print Department of the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, do indeed occasionally suggest some similarity of origin or manner with the school of Van Eyck. But it is unnecessary to debate the point at greater length. Whether produced in France, in the Low Countries, or in Germany, the dotted engravings of the fifteenth century add so little lustre to the land which gave them birth, that no scepticism as to their origin need lie very heavily on the conscience. In the general history of the documents on the origin of engraving, the dotted prints form a series distinguished by the method of their execution from any other earlier or contemporary specimens of work; the date mark 1454, borne by one among the number, gives us47 authentic information as to the time of these strange experiments, these curiosities of handicraft rather than of art. This is as much as we need to bear in mind upon the subject, and quite enough to complete the history of the elementary attempts which preceded or which co-existed for a few years with the beginning of engraving by incised line in Italy.

We have now arrived at that decisive moment when engraving, endowed with fresh resources, was practised for the first time by real masters. Up to the present, the trifling ability and skill possessed by certain wood-cutters and the peculiar methods of dotted engraving have been the only means by which we could measure the efforts expended in the search for new technical methods, or in their use when discovered. We have now done with such hesitating and halting progress. The art of printing from plates cut in intaglio had no sooner been discovered by, or at least dignified by the practice of, a Florentine goldsmith, than upon every side fresh talent was evoked. In Italy and Germany it was a question of who should profit most and quickest by the advance. A spirit of rivalry at once arose between the two schools; and fifteen years had not elapsed since Italian art had given its note in the works of the goldsmith engravers of the school of Finiguerra, before German art had found an equally definite expression in the works of the Master of 1466. But, before examining this simultaneous progress, we shall have to say a few words on the historical part of the question, and to48 return to the origin of the process of intaglio engraving, as we have already done with the origin of engraving in relief. This part of our subject must be briefly and finally disposed of; we may then altogether abandon the uncertain ground of archæological hypothesis.

FIRST ATTEMPTS AT INTAGLIO ENGRAVING. THE NIELLI OF THE FLORENTINE GOLDSMITHS. PRINTS BY THE ITALIAN AND GERMAN PAINTER-ENGRAVERS OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY

We have seen that Gutenberg's permanent improvements in the method of printing resulted in the substitution, so far as written speech was concerned, of a mode of reproduction almost infinitely fruitful, and even rapid when compared to the slowness and the limited resources of the xylographic method. Typography was destined to abolish the use of block printing, and more particularly of caligraphy, which, till then, had occupied so many pious and patient hands both in monasteries and in schools. The art of printing from engravings worked similar mischief to the illuminator's craft. Such were, before long, the natural consequences of the progress made; and, we may add, such had been from the first the chief object of these innovations.

Perhaps this double revolution, so potent in its general effect and in its influence on modern civilisation, may have appeared to those engaged in it no more important than a purely industrial improvement. Surely, for instance, we do no injustice to Gutenberg if we accept with some reserve the vast50 political and philosophical ideas, and the purposes of universal enfranchisement, with which he has been sometimes credited? Probably the views of the inventor of printing reached neither so far nor so high. He did not intend to figure as an apostle, nor did he regard himself as devoted to a philanthropic mission, as we should put it in the present day. He considered himself no more than a workman with a happy thought, when he proposed to replace the lengthy and costly labours of the copyist by a process so much cheaper and so much more expeditious.

A somewhat similar idea had already occurred to the xylographic printers. Even the title of one of the first books published by them, the "Biblia Pauperum," or "Bible for the Poor," proved their wish to place within the reach of the masses an equivalent to those illuminated manuscript copies which were only obtainable by the rich. One glance at the ancient xylographic collections is enough to disclose the spirit in which such work was undertaken, and the design with which it was conceived. The new industry imitated in every particular the appearance of those earlier works due to the pen of the scribe or to the brush of the illuminator; and, perhaps, the printers themselves, speculating on the want of discernment in the purchasing public, thought less of exposing the secret of their method than of maintaining an illusion.

In most of the xylographic books, indeed, the first page is quite without ornamentation. There are neither chapter-headings nor ornamental capitals; the51 blank space seems to await the hand of the illuminator, who should step in to finish the work of the printer, and complete the resemblance between the printed books and the manuscript. Gutenberg followed; and even he, although less closely an imitator of caligraphy, did not himself disdain at first to practise some deception as to the nature of his method. It is said that the Bible he printed at Mayence was sold as manuscript; and the letterpress is certainly not accompanied by any technical explanation, or by any note of the printer's name or the mode of fabrication. Not till somewhat later, when he published the "Catholicon," did Gutenberg avow that he had printed this book "without the help of reed, quill, or stylus, but by means of a marvellous array of moulds and punches." Even in this specimen of a process already settled and finally disclosed to the public, the capital letters were left blank in the printing, and were afterwards filled in with brush or pen. It was a farewell salutation to the past, and the latest appearance of that old art which was now doomed to pass away before the new, and to leave the field to the products of the press.

Did the inventor of the art of printing from plates cut in intaglio, like the inventor of the art of typography, only wish at first to extend to a larger public what had hitherto been reserved for the favoured few? Was early engraving but a weapon turned against the monopoly of the miniature painter? We might be tempted to think so, from the number of manuscripts belonging to the second half of the52 fifteenth century, in which coloured prints, surrounded by borders also coloured, are set opposite a printed text, apparently in order to imitate as nearly as possible the familiar aspect of illuminated books. Next in turn came printed books with illustrations, and loose sheets published separately for every-day use. The Italian engravers, even before they began to adorn with the burin those works which have been the most frequently illustrated—such, for instance, as the religious handbooks and the poem of Dante—employed the new process from as early as 1465, to assure their calendars a wider publicity. But let us return to the time when engraving was yet in its early stages, and when—by chance, by force of original genius, or by the mere completion of what had been begun by other hands—a Florentine goldsmith, one Maso Finiguerra, succeeded in fixing on paper the impression of a silver plate on which lines had been engraved in intaglio and filled with black.

Finiguerra's great glory does not, however, lie in the solution of the practical difficulty. Amongst the Italians none before him had ever thought of trying to print from a work engraved in incised line or intaglio on metal; and therefore, at least, in his own country, he deserved the honours of priority. But the invention of the process—that is, in the absolute and literal sense of its name, the notion of reproducing burin work by printing—was certainly not peculiar to Finiguerra. Unconscious of what was passing elsewhere, he may have been the first in Florence to attempt this revolution in art; but53 beyond the frontiers of Italy, many had already employed for the necessities of trade that method which it was his to turn into a powerful instrument of art. His true glory consists in the unexpected authority with which he inaugurated the movement. Although it may be true that there are prints a few years older than any Florentine niello—the German specimens of 1446, discovered but the other day by M. Renouvier15 or the "Virgin" of 1451 described by M. Passavant16—it cannot change the real date of the invention of engraving; that date has been written by the hand of a man of talent, the first engraver worthy of the name of artist.

That Finiguerra was really the inventor of engraving, because he dignified the new process by the striking ability with which he used it, and proved his power where his contemporaries had only exhibited their weakness, must be distinctly laid down, even at the risk of scandalising some of the learned. He has the same right to celebrity as Gutenberg, who, like him, was but the discoverer of a decisive advance; the same right also as Nicolò Pisano and Giotto, the real founders of the race of the Great Masters, and, truly speaking, the first painter and the first sculptor who appeared in Italy, although neither sculpture nor painting were even novelties at the moment of their birth. As a mere question of date, the "Pax" of Florence may not be the earliest example54 of engraving; be it so. But in which of these earlier attempts, now so much acclaimed as arguments against the accepted tradition, can we glean even the faintest promise of the merits which distinguish that illustrious engraving? He who wrought it is no usurper; his fame is a legitimate conquest.

It is a singular coincidence that the discovery of printing and that of the art of taking proofs on paper from a plate engraved in intaglio, or, to speak more exactly, that the final improvements of both these processes, should have sprung up almost simultaneously, one in Italy and the other in Germany. There is only an interval of two years between the time when Finiguerra printed his first engraving in 1452, and the time when Gutenberg exhibited his first attempts at printing in 1454. Till then, copies drawn, painted, or written by hand had been the only efficient means of reproduction. None, even amongst those most capable of original thought or action, considered it beneath them to set forth the thought of others. Boccaccio and Petrarch exchanged whole books of Livy or of Cicero which they had patiently transcribed, and monkish or professional artists copied on the vellum of missals the paintings which covered the walls or adorned the altars of their churches. Such subjects as were engraved on wood were only designed to stimulate the devotion of the pious. Both by their inadequate execution, and the special use for which they were intended, they must rank as industrial products rather than as works of art.

Besides illumination and wood engraving, there55 was a process sometimes used to copy certain originals, portraits or fancy subjects, but more frequently employed by goldsmiths in the decoration of chalices, reliquaries, and altar canons. This process was nothing but a special application and combination of the resources belonging to the long known arts of enamelling and chalcography, which last simply means engraving on metal. The incised lines made by the graver in a plate of silver, or of silver and gold combined, were filled with a mixture of lead, silver, and copper, made more easily fusible by the addition of a certain quantity of borax and sulphur. This blackish-coloured mixture (nigellum, whence niello, niellare) left the unengraved parts exposed, and, in cooling, became encrusted in the furrows where it had been introduced. After this, the plate, when carefully polished, presented to the eye the contrast of a design in dull black enamel traced upon a field of shining metal.

Towards the middle of the fifteenth century this kind of engraving was much practised in Italy, especially in Florence, where the best niellatori were to be found. One of them, Tomaso, or for short, Maso Finiguerra, was, like many goldsmiths of his time, at once an engraver, a designer, and a sculptor. The drawings attributed to him, his nielli, and the bas-reliefs partly by him and partly by Antonio Pollajuolo, would not, perhaps, have been enough to have preserved his memory: it is his invention—in the degree we mentioned—of the art of printing intaglio engravings, or rather of the art of engraving itself, that has made him immortal.

56 What, however, can seem more simple than this discovery? It is even difficult to understand why it was not made before, when we remember not only that the printing of blocks engraved in relief had been practised since the beginning of the fifteenth century, but that the niellatori themselves were in the habit of taking, first in clay and then in sulphur, an impression and a counter-impression of their work before applying the enamel. What should seem more simple than to have taken a direct proof on a thin elastic body such as paper? But it is always easy to criticise after the event, and to point out the road of progress when the end has been attained. Who knows if to-day there is not lying at our very hand some discovery which yet we never think of grasping, and if our present blindness will not be the cause of similar wonder to our successors?

At any rate, Finiguerra had found the solution of the problem by 1452. This was put beyond doubt on the day towards the close of the last century (1797), when Zani discovered, in the Print-Room of the Paris Library, a niello by Finiguerra printed on paper of indisputable date.

Fig. 16.—FINIGUERRA.

The "Pax" of the Baptistery of St. John at Florence.

This little print, or rather proof, taken before the plate was put in niello, of a "Pax"17 engraved by the Florentine goldsmith for the Baptistery of St. John58 represents the Coronation of the Virgin. It measures only 130 millimetres by 87. As regards its size, therefore, the "Coronation" is really only a vignette; but it is a vignette handled with such knowledge and style, and informed with so deep a feeling for beauty, that it would bear with perfect impunity the ordeal of being enlarged a hundred times and transferred to a canvas or a wall. Its claims as an archæological specimen, and the value that four centuries have added to this small piece of perishable paper, must assuredly neither be forgotten nor misunderstood by any one. Yet he would be ill-advised, on the other hand, who should regard this masterpiece of art as a mere historical curiosity.

Fig. 17.—ITALIAN NIELLO.

(Fifteenth Century.)

Fig. 18.

ITALIAN NIELLO. (Fifteenth Century.)

The rare merits which distinguish Finiguerra's "Coronation" are to be seen, though much less conspicuously, in a certain number of works attributed to the same origin. Other pieces engraved at the same time, and printed under the same conditions by unknown Florentine workmen, prove that the example given in 1452 had59 at once created imitators. It must be remarked, however, that amongst such works, whether attributed to Finiguerra or to other goldsmiths of the same time and country, none belong to the class of engravings properly so called. In other words they are only what we have agreed to call nielli: that is, proofs on paper of plates designed to be afterwards enamelled, and not impressions of plates specially and finally intended to be used for printing. It would almost appear that the master and his first followers failed to foresee all the results and benefits of this discovery; that they looked upon it only as a surer test of work than clay or sulphur casts, as a test process suitable to certain stages of the labours of the goldsmith. In one word, from the time when he made his first success till the end of his life, Finiguerra probably only used the new process to forward his work as a niellatore, without its ever occurring to him to employ it for its own sake, and in the spirit of a real engraver.

Fig. 19.—ITALIAN NIELLO.

(Fifteenth Century.)

Florentine engravings of the fifteenth century, other than in niello, or those at least whose origin and date are certain, are not only later than Finiguerra's60 working days, but are even later than the year of his death (1470). In Germany, from the very beginning, so to speak, of the period of initiation, the Master of 1466 and his disciples were multiplying impressions of their works, and profiting by the full resources of the new process. In Florence, on the contrary, there passed about twenty years during which the art seems to have remained stationary and confined to the same narrow field of practice as at first. You may visit the richest public or private collections without meeting (with the exception of works in niello) any authentic and official specimen of Florentine engraving of the time of which we speak.18 You may open books and catalogues, and find no mention of any engraved subject that can be called a print earlier than those attributed to Baccio Baldini, or to Botticelli, which only appeared in the last quarter of the century. Yet it is impossible to find any explanation of this sterility—of this extraordinary absence of a school of engravers, in the exact acceptation of the word, outside of the group of the niellatori.

Fig 20.—BACCIO BALDINI.

Illustration from the "Divina Commedia" of 1481.

Some years later, however, progress had led to emancipation. The art of engraving, henceforth free, broke from its industrial servitude, deserted the62 traditions of enamelling and chasing, and took possession of its own domain. There are still to be remarked, of course, a certain timidity and a certain lack of experience in the handling of the tool, an execution at once summary and strangely careful, a mixture of naïve intentions and conventional modes of expression. But the burin, though only able as yet imperfectly to treat lines in mass and vary the values of shadows, has mastered the secret of representing life with precision and elegance of outline, and can render the facial expression of the most different types. Sacred and mythological personages, sybils and prophets, madonnas and the gods of Olympus, the men and women of the fifteenth century, all not only reveal at the first glance their close pictorial relationship to the general inclinations and habits of Florentine art of the fourteenth century, but show us these tendencies continued and confirmed in a fresh form. The delicacy which charms us in the bas-reliefs and the pictures of the time; the aspiration, common to contemporary painters and sculptors, of idealising and heightening the expression of external facts; the love of rare, exquisite, and somewhat subtle expression, are to be found in the works left by the painter-engravers who were the immediate followers of Finiguerra, no less clearly than in the painted and sculptured subjects on the walls of contemporary churches and palaces.

Fig. 21.—BACCIO BALDINI.

Theseus and Ariadne.

Whatever we may suppose to have been the part

due to Baccio Baldini, to Botticelli, to Pollajuolo, or

to anybody else; with whatever acuteness we may63

discern, or think we discern, the inequalities of style

and the tricks of touch in different men; all their65

66

works display a vigorous unity, which must be carefully

taken into account, inasmuch as it gives its

character to the school. Though we should even

succeed in separately labelling with a proper name

each one of the works which are all really dependent

on one another, the gain would be small.

Fig. 22.—BACCIO BALDINI.

The Prophet Baruch.

Provided that neither the qualities nor the meaning of the whole movement be understood, we may, as regards the distribution of minor parts, resign ourselves to doubt, and even ignorance, and console ourselves for the mystery which enshrouds these nameless talents: and this the more readily that we can with greater impartiality appreciate their merits in the absence of biographical hypothesis and the commentaries of the scholar.

Fig. 23.—BACCIO BALDINI.

The Sibyl of Cumæ.

The prints due to the Florentine painter-engravers who followed Finiguerra mark a transitional epoch between the first stage of Italian engraving and the time when the art, having entered upon its period of virility, used its powers with confidence, and showed itself equal to any feat. The privileges of fruitfulness and success in this second phase no longer, it is true, belong wholly to Florence. It would seem that, after having again and again given birth to so much talent, Florentine art, exhausted by rapid production, reposed and voluntarily allowed the neighbouring schools to take her place. Even before the appearance of Marc Antonio, the most important proofs of skill were given outside of Tuscany; and if towards the beginning, or at the beginning, of the sixteenth century, the numerous67 plates engraved by Robetta still continued to sustain the reputation of the Florentine school, such a result was owing far less to the individual talent of the engraver, than to the charm and intrinsic value of his models.

Fig. 25.—MANTEGNA.

The Virgin and the Infant Jesus.

Of all the Italian engravers who, towards the end of the fifteenth century, completed the popularisation in their country of the art whose first secrets and examples were revealed and supplied by Florence, the one most powerfully inspired and most skilful was certainly Andrea Mantegna. We need not here69 recall the true position of this great artist in the history of painting. Such of his pictures and decorative paintings as still exist possess a world-wide fame;70 and, though his engravings are less generally known, they deserve equal celebrity, and would justify equal admiration.

Fig. 26.—MANTEGNA.

From the Print Representing a Battle of Sea-Gods.

The engraved work of Mantegna consists of only twenty plates, about half of which are religious, and the remainder mythological or historical. Though none of these engravings bears the signature or initials of the Paduan master, their authenticity cannot be doubted. It is abundantly manifest in certain marked characteristics of style and workmanship; in the delicate yet strong precision of the drawing; and in that somewhat rude elegance which was at the command of none of his contemporaries in the same degree. Every part of them, even where they savour of imperfection or of extravagance, bears witness to the indomitable will and independent genius of a master. His touch imparts a passionate and thrilling aspect even to the details of architectural decoration and the smallest inanimate objects. One would suppose that, after having studied each part of his subject with the eye of a man of culture and a thinker, Mantegna, when he came to represent it on the metal, forgot all but the burning impatience of his hand and the fever of the struggle with his material.

Fig. 27.—MANTEGNA.

The Entombment.

Fig. 28.—MANTEGNA.

Jesus Christ, St. Andrew, and St. Longinus.

And yet the handling alone of such works as the "Entombment" and the "Triumph of Cæsar" bears witness to the talent of an engraver already more experienced than any of his Italian predecessors and more alive to the real resources of his art. The burin in Mantegna's hand displays a firmness that can no longer be called stiffness; and, while it hardly as yet72 can be said to imitate painting, competes in boldness and rapidity at least with the effect of chalk or the pen. Unlike the Florentine engravers, with their timid sparse strokes which scarcely served to mark the outlines, Mantegna works with masses of shadow produced by means of closer graining, and seeks to73 express, or at any rate to suggest, internal modelling, instead of contenting himself with the mere outlines of the body. In a word, Mantegna as an engraver never forgot his knowledge as a painter; and it is this, combined with the rare vigour of his imagination, which assures him the first place amongst the Italian masters before the time of Marc Antonio.

Fig. 29.—MANTEGNA.

From the Triumph of Julius Cæsar.

74 Mantegna had soon many imitators. Some of them, as Mocetto, Jacopo Francia, Nicoletto da Modena, and Jacopo de' Barbari, known as the Master of the Caduceus, though profiting by his example, did not push their docility so far as to sacrifice their own tastes and individual sentiment. Others, as Zoan Andrea and Giovanni Antonio da Brescia, whose work has been sometimes mistaken for that of Mantegna himself, set themselves not only to make his manner their own, but to imitate his engravings line for line.

However strongly Mantegna's influence may have acted on the Italian engravers of the fifteenth century, or the early years of the sixteenth, it hardly seems to have extended beyond Lombardy, Venice, and the small neighbouring states. It was neither in Florence nor in Rome that the Paduan example principally excited the spirit of imitation. The works it gave rise to belong nearly all of them to artists formed under the master's very eyes, or in close proximity to his teachings, whether the manner of the leader of the school appeared in the efforts of pure copyists and imitators more or less adroit, or whether it appeared in a much modified condition in the works of more independent disciples.

Fig. 30.—MOCETTO.

Bacchus.

It was in Verona, Venice, Modena, and Bologna that the movement which Mantegna started in art found its most brilliant continuation. As the engravers, emboldened by experience, gradually tended to reconcile something of their own inspirations and personal desires with the doctrines transmitted to them, assuredly a75 certain amount of progress was manifested and some improvements were introduced into the use or the combination of means; but in spite of such partial divergences, the general appearance of the works proves their common origin, and testifies to the imprudence76 of the efforts sometimes made to split into small isolated groups and infinite subdivisions what, in reality, forms a complete whole, a genuine school.

The same spirit of unity is again found to predominate in all the works of the German engravers belonging to the second half of the fifteenth century. With respect to purpose and style, there is certainly a great difference between the early Italian engravings and those which mark the beginning of the art in the towns of High and Low Germany. But both have this in common: that certain fixed traditions once founded remain for a time almost unchangeable; that certain fixed methods of execution are held like articles of faith, and only modified with an extreme respect for the time-honoured principles of early days. The Master of 1466, and shortly after him, Martin Schongauer, had scarcely shown themselves, before their example was followed, and their teaching obediently practised, by a greater number of disciples than had followed, or were destined to follow, in Italy the lead of the contemporaries of Finiguerra or Mantegna. The influence exerted by the latter had at least an equivalent in the ascendancy of Martin Schongauer; while the Master of 1466, in the character of a founder, which belongs to him, has almost the same importance in the history of German engraving as the Florentine goldsmith in that of Italian engraving.

Fig. 31.—BATTISTA DEL PORTO, CALLED THE "MASTER OF THE BIRD."

St. Sebastian.

Fig. 32.—MARTIN SCHONGAUER.

The Virgin and the Infant Jesus.

Fig. 33.—MARTIN SCHONGAUER.

St. John the Evangelist.

The Master of 1466 may, indeed, be regarded as

the Finiguerra of Germany, because he was the first

in his own country to raise to the dignity of an art77

what had been only an industrial process in the hands

of talentless workmen. Like wood engraving, intaglio

engraving, such as we see it in German prints some

years before the works of the Master of 1466, had only78

succeeded in spreading abroad, in the towns on the

banks of the Rhine, productions of a rude or grotesque

symbolism, in which, notwithstanding recent attempts

to exaggerate their value,

a want of technical experience

was as evident

as extreme poverty of

conception. These archæological

curiosities

can have no legitimate

place amongst works of

art, and we may without

injustice take still less

account of them, as the

rapid progress made by

the Master of 1466

throws their inferiority

into greater relief. If the

anonymous artist called

the Master of 1466 be

the true founder of the

German school of engraving;

if he show himself

cleverer than any

of the Italian engravers

of the period—from the

point of view only of practical execution, and the

right handling of the tool—it does not necessarily

follow that he holds the same priority in talent as

he certainly holds in order of time before all other

engravers of the same age and country. One of79

these, Martin Schongauer, called also "handsome

Martin," or for short, "Martin Schon," may have a

better right to the highest place. Endowed with

more imagination than

the Master of 1466, with