"Let mee play the fool: With mirth and laughter let old wrinkles come; And let my liver rather heat with wine, Than my heart cool with mortifying groans, Why should a man, whose blood is warm through, Sit like his grandsire, cut in alubaster? Sleep when he wakes, and creep into the jaundice by being peevish?" Shakspear

CONTENTS

POINT II. THE SHORT COURTSHIP.

POINT IV. EXCHANGE NO ROBBERY.

POINT V. THE JOLLY BEGGARS; OR LOVE AND LIBERTY, A CANTATA, BY ROBERT BURNS

POINT IX. THE DOWNFALL OF HOLY CHURCH.

POINT X. A VISIT WITHOUT FORM.

It will be readily perceived that the literary part of this work is of humble pretensions. One object alone has been aimed at and it is hoped with success—to select or to invent those incidents which' might be interesting or amusing in themselves, while they afforded scope for the peculiar talents of the artist who adorns them with his designs. The selection was more difficult than may at first sight be supposed. It is true, there is no paucity of subjects of wit and humour, but he who will take the trouble to examine them, will find how few are adapted for pictorial representation. No artist can embody a point of wit, and the humour of many of the most laughable stories would vanish at the touch of the pencil of the most ingenious designer in the world. Those ludicrous subjects only which are rich in the humour of situation are calculated for graphic illustration. To prove the following anecdotes are not deficient in this respect, no other appeal is necessary than to the plates themselves! Look at the breadth of the humour, the point of the situation, the selection of the figures, the action, and its accompaniments, and deny (without a laugh on the face) that this portion of the work answers the end in view. In all this the writer or compiler, or whatever he may be called, claims little merit. That the whole effect is comic, that the persons are ludicrous, and engaged in laughable groups and surrounded with objects which tend to broaden the grin, all this, and a thousand times more, belongs to Mr. Cruikshank;—the writer only claims the merit of having suggested to him the materials.

Some of the ten points, now submitted to the public, arise out of a reprint of that admirable piece of humour, the Jolly Beggars of Burns;—A part of his works almost unknown to the public, in consequence of the scrupulousness of the poet's biographer and editor, who withheld them from the world. Lest we however should incur the charge, which Dr. Currie apprehended, we beg leave to prefix the observations on this subject by the first literary character in the kingdom, Sir Walter Scott, as they appeared in the Quarterly Review.

"Yet applauding, as we do most highly applaud, the leading principles of Dr. Currie's selection, we are aware that they sometimes led him into fastidious and over-delicate rejection of the bard's most spirited and happy effusions. A thin octavo, published at Glasgow in 1801, under the title of 'Poems ascribed to Robert Burns, the Ayrshire bard,' furnishes valuable proofs of this assertion; it contains, among a good deal of rubbish, some of his most brilliant poetry. A cantata, in particular, called The Jolly Beggars, for humorous description and nice discrimination of character, is inferior to no poem of the same length in the whole range of English poetry. The scene, indeed, is laid in the very lowest department of low life, the actors being a set of strolling vagrants, met to carouse, and barter their rags and plunder for liquor in a hedge ale-house. Yet even in describing the movements of such a group, the native taste of the poet has never suffered his pen to slide into any thing coarse or disgusting. The extravagant glee and outrageous frolic of the beggars are ridiculously contrasted with their maimed limbs, rags, and crutches—the sordid and squalid circumstances of their appearance are judiciously thrown into the shade. Nor is the art of the poet less conspicuous in the individual figures, than in the general mass. The festive vagrants are distinguished from each other by personal appearance and character, as much as any fortuitous assembly in the higher orders of life. The group, it must be observed, is of Scottish character, and doubtless our northern brethren are more familiar with its varieties than we are; yet the distinctions are too well marked to escape even the southern. The most prominent persons are a maimed soldier and his female companion, a hackneyed follower of the camp, a stroller, late the consort of an highland ketterer, or sturdy beggar—'but weary fa' the waefu' woodie!'—Being now at liberty, she becomes an object of rivalry between a pigmy scraper with his fiddle' and a strolling tinker. The latter, a desperate bandit, like most of his profession, terrifies the musician out of the field, and is preferred by the damsel of course. A wandering ballad-singer, with a brace of doxies, is last introduced upon the stage. Each of these mendicants sings a song in character, and such a collection of humorous lyrics, connected by vivid poetical description, is not perhaps to be paralleled in the English language. The ditty chaunted by the Ballad Singer is certainly far superior to any thing in the Beggar's Opera, where alone we could expect to find its parallel.

"We are at a loss to conceive any good reason why Dr. Currie did not introduce this singular and humorous cantata into his collection. It is true, that in one or two passages the muse has trespassed slightly upon decorum, where, in the language of Scottish song,

"High kilted was she, "As she gaed owre the lea."

"Something, however, is to be allowed to the nature of the subject, and something to the education of the poet: and if from veneration to the names of Swift and Dryden, we tolerate the grossness of the one, and the indelicacy of the other, the respect due to that of Burns, may surely claim indulgence for a few light strokes of broad humour..

"Knowing that this, and hoping that other compositions of similar spirit and tenor, might yet be recovered, we were induced to think that some of them, at least, had found a place in the collection given to the public by Mr. Cromek. But he has neither risqued the censure, nor gained the applause, which might have belonged to such an undertaking."

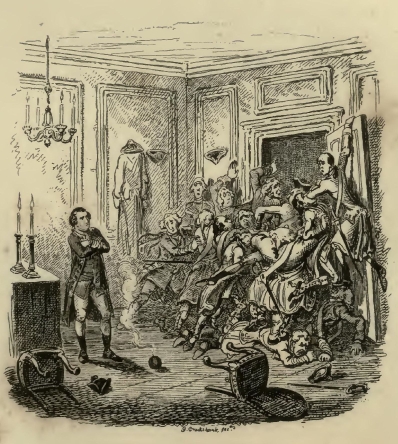

When the American army was at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777, a captain of the Virginian Line refused a challenge sent him by a brother officer, alleging that his life was devoted to the service of his country, and that he did not think it a point of duty to risk it to gratify the caprice of any man. This point of duty gave occasion to a point of humour which clearly displayed the brilliant points of the officer's character, and exposed the weak ones of his brothers in the service in a very pointed manner. His antagonist gave him the character of a coward through the whole army. Conscious of not having merited the aspersion, and discovering the injury he should sustain in the minds of those unacquainted with him, he repaired one evening to a general meeting of the officers of that line. On his entrance, he was avoided by the company, and the officer who had challenged him, insolently ordered him to leave the room; a request which was loudly re-echoed from all parts. He refused, and asserted that he came there to vindicate his fame; and after mentioning the reasons which induced him not to accept the challenge, he applied a large hand grenade to the candle, and when the fuse had caught fire, threw it on the floor, saying, "Here, gentlemen, this will quickly determine which of us all dare brave danger most."

At first they stared upon him for a moment in stupid astonishment, but their eyes soon fell upon the fusé of the grenade, which was fast burning down. Away scampered Colonel, General, Ensign, and Captain, and all made a rush at the door. "Devil take the hindmost." Some fell, and others made way over the bodies of their comrades; some succeeded in getting out, but for an instant there was a general heap of flesh sprawling at the entrance of the apartment. Here was a colonel jostling with a subaltern, and there fat generals pressing lean lieutenants into the boards, and blustering majors, and squeaking ensigns wrestling for exit; the size of one and the feebleness of the other making their chance of departure pretty equal, until time, which does all things at last, cleared the room and left the noble captain standing over the grenade with his arms folded, and his countenance expressing every kind of scorn and contempt for the train of scrambling red coats, as they toiled and bustled and bored their way out of the door.

After the explosion had taken place, some of them ventured to return, to take a peep at the mangled remains of their comrade, whom however to their great surprise they found alive and uninjured.—When they were all gone, the captain threw himself flat on the floor as the only possible means of escape, and fortunately came off with a whole skin, and a repaired reputation.

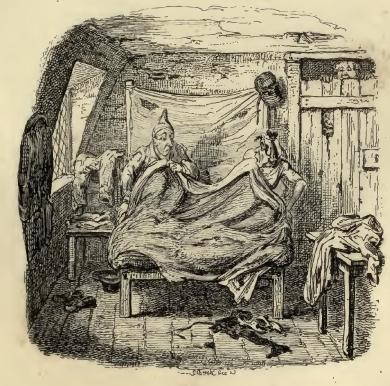

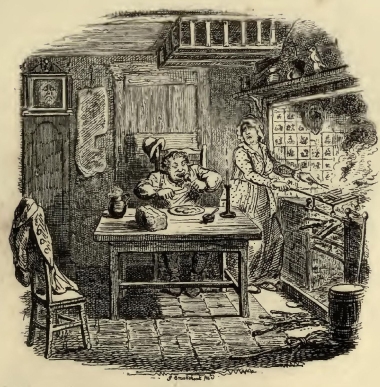

As a gentleman was passing along one of the more retired streets of London late in the evening, he stumbled over the body of an old man, whom on examination he found in a state of excessive inebriation, and who had in consequence tumbled down and rolled into the kennel. He had not gone many yards farther when he found an old woman very nearly in the same circumstances. It immediately struck Mr. L. that this was some poor old couple, who, overcome with the fatigues of the day, had indulged too freely in some restorative beverage, whether Hodges' or Deady's the historian does not say. Full of this idea, and animated by his own charitable disposition, Mr. L. soon made arrangements for the reception of the poor couple into a neighbouring public house, where the landlord promised that the senseless pair should be undressed and placed in a warm and comfortable bed. To bed they were put. Mr. L. left them lying side by side, snoring in concert, and likely to pass together a more harmonious night than perhaps would have been the case had they possessed the full enjoyment of their senses. L. journeyed homewards filled with the satisfaction arising from the performance of a kind deed, and never reflected that there was a possibility of his having joined a pair whom the laws of God had not made one. The fact was, that the old man and the old woman were perfect strangers to each other, and their being found in a similar situation was purely accidental. In London, however extraordinary it may appear, many poor folks get drunk at night, especially Saturday night, and what is not less wonderful, they are in this state often unable to preserve their balance—the laws of gravity exert their influence, and the patient rolls into the kennel. Soundly—soundly did this late united pair sleep and snore till morning,—when the light broke in upon them and disclosed the secret.—Imagine the consternation of the old lady when the fumes of intoxication were dissipated, and she opened her eyes upon her snoring partner—where she was or how she had been put there she knew not. It was clear she was in bed with a man, and that was an event which had never happened to her before,—so she set up a scream, and roused the old gentleman, whose astonishment was not a jot less than the lady's.

She sat upon end in bed staring at him, he moved himself into, a similar situation and riveted his eyes upon her, and so they remained for a few instant's both full of perfect wonderment;—at last it struck the poor lady that this was some monster of a man who had succeeded in some horrible design upon her honour; the idea in a moment gave her the look and manner of a fury, she flung out of bed and roared aloud to the admiration of all the inmates of the house, who attracted by her first scream were already peeping in at the door of the room,—"make me an honest woman, thou wretch," she cried—"villain that you are,—make an honest woman of me, or I'll be the death of thee"—down she sat upon the bed-stocks, and as she attempted to dress herself she interlarded her occupation with calling for vengeance upon her horrible seducer, who sat trembling at the other side of the bed, vainly attempting in his fright to insinuate his legs into his old tattered breeches. The landlord at last interfered with the authority of his station, and on inquiry found that no breach had been made which could not be easily repaired. The old gentleman was asked if he had any objection to take his fair bedfellow for a helpmate during the remainder of his life; he stammered out his acquiescence as well as he could, and the enraged virgin consented to smooth down her anger on satisfaction being made to her injured honour. The bargain was soon struck, the happy pair were bundled off to church, amidst the laughing shouts of the mob, where a parson waited to make good the match too precipitately formed by our charitable friend.

Frederick the Great, King of Prussia, was so remarkably fond of children, that he suffered the sons of the Prince Royal to enter his apartment whenever they thought proper. One day, while he was writing in his closet, the eldest of these princes was playing at shuttlecock near him. The shuttlecock happened to fall upon the table at which the King sat, who threw it at the young prince and continued to write. The shuttlecock falling on the table a second time, the King threw it back, looking sternly at the child, who promised that no accident of the kind should happen again; the shuttlecock however fell a third time and even upon the paper on which the king was writing. Frederick then took the shuttlecock and put it in his pocket: the little prince humbly asked pardon and begged the King to return him his shuttlecock. His Majesty refused: the prince redoubled his entreaties, but no attention was paid to them; the young prince at length being tired of begging, advanced boldly towards the King, put his two hands on his side, and tossing back his little head with great haughtiness, said in a threatening tone, "Will your Majesty give me my shuttlecock, Yes or No?"

The King burst into a fit of laughter, and taking the shuttlecock out of his pocket, returned it to the prince saying, "you are a brave boy, you will never suffer Silesia to be taken from you."

Near Taunton, in Somersetshire, lived a sturdy fellow, by trade a miller, who possessed a handsome and buxom young woman for his wife. The said dame was many years the junior of her spouse, and thought that the neighbouring village contained not a few more agreeable companions, than the one whom Heaven had given her for life. Of this circumstance the miller had some suspicions, and determined to set them at rest one way or the other. Accordingly, one day he pretended to set off to buy corn, and told his wife that he should not be at home that night. The miller departed, and when the shades of evening afforded some concealment, in glided, to supply his place at bed and board, a neighbouring country squire.

As the village clock struck one that night, and as the loving pair were wrapped in sleep, a loud knocking was heard at the door.

The miller had unexpectedly returned home, and the unfortunate couple within were reduced to despair. The wit of the female was however equal to the emergency; the gentleman's clothes were pushed under her own, and his person was conducted into the kitchen, by the frail fair one, and there enclosed in a singular place of security.

The tall house clock, which always forms a part of the furniture of the "parlour, kitchen, and all," of men of our miller's rank, was at that time out of order, and the works had, on the very morning in question, been conveyed to Taunton, to undergo a thorough repair. It immediately struck the damsel that her lover could abide in no safer place than this, until her husband was asleep, and she could return and let him out. Now the country squire was a tall and a stout man, with a jolly rubicund physiognomy. He consequently enclosed himself in the clock-case with some difficulty, and when the good woman locked the door of it, as the only way of keeping it shut, it gave him a nip in the paunch, which would have extorted a cry under any other circumstances. As it was, the tightness below threw all the blood into his countenance, which, for such was his height, overtopped the wood work of the case, and appeared exactly at the spot where the clock usually shewed the hour. So that, had a light been held up to it, this portentous face would have borne the appearance of a dark red moon scowling, out of fog and vapours upon a stormy night. This despatched, the dame commenced her own part with confidence. She gaped and yawned, and only admitted the miller till he had cursed and sworn his wife into a conviction, that he was her lawful husband, and no deceiver who had mimicked his voice and manner for his own wicked purposes. Much to the dismay of the parties already in possession of the house, the miller insisted upon striking a light, which at length obtaining, he drove his wife before him up to the bed-room, and then slily and under pretence of something else, examined the apartment; and concluded with a thorough conviction of the groundlessness of his suspicions.

The wife, overjoyed at getting the candle out of the kitchen without discovery, was in high good humour, so that the miller became in excellent spirits too, both on account of his agreeable reception and the dispersion of his fears, and as a proof of his state of mind gave his wife a hearty kiss, and swore that they would go down and have a cozy bit of supper together before they went to bed. In vain the poor woman resisted, the slice of bacon must be broiled and the eggs poached. With trembling hand she bore the light into the kitchen, and durst not cast a glance upon the clock case where the prisoner, full of horror at the return of the candle, and reduced to a state of insufferable impatience by his miserable plight, uttered a deep low groan of despair as they entered the apartment. Fortunately it was not loud enough to attract the miller's attention, but thrilled through the heart of his unfortunate spouse. The happy pair soon began their culinary operations, the male with a light heart and a hungry appetite, the female sick and trembling at the disclosure which she feared was inevitable. All she could do, she did. She tried to keep up a conversation, she shaded the light, and she spread rasher after rasher before the all-devouring miller, who seemed as if intent to display his prowess before his rival, who was most ruefully and intently gazing upon him from his window of observation.

By the lady's artful management, the miller sat with only a side view of the clock, and allowed a few sympathizing glances to be interchanged between the unhappy squire and his love, as she spread the tempting meal before her liege lord. Doubtless they both thought the miller's appetite was enormous, and in the calculation of either of them, he had already eat a side of bacon, when he declared he had done. Now for good luck! inwardly exclaimed the dame, fortune befriend me, and let me get him up stairs without casting a look upon that poor deplorable face; which by the bye had lately been assuming all hues, and within the last two minutes had turned from a blue red to deadly pale, and back again to red black; and slight twitches and convulsive motions were observed in the muscles of his face, as if the poor unfortunate owner of them was tormented by some body below, who alternately pricked and pinched him. Oh, what a weight was taken off the heart of the frail fair one, and how fervently did she offer up vows of chastity in the gratitude of the moment, when the miller, having eat and drank his fill, made a motion for the bed room. Gladly was she attending him, when, as ill luck would have it, a loud sneeze was heard in the room, which was followed by an equally loud; scream from the lady of the miller, who now gave all up for lost. It seemed that the dust of the clock-case had been disturbed by the body of the squire, and part of it being dislodged, had sought refuge in the intricacies of his nostrils. Hence the wincings and writhings, which, over and above being abominably nipped, produced the awful changes recorded above, and at length ended in a sneeze, which he could no longer restrain. This event had not the expected issue, for the dame in her fright threw down the candlestick, which she held in her hand, and extinguished the light. The good miller, now drowsy and stupid, chid her for being alarmed at the sneezing of a cat; and, not waiting for the poking out of a light from the dying embers, pushed his wife and himself off to bed, bestowing upon her, by the way, many of those endearing caresses, which husbands in a good humour lavish upon their wives; which caresses were certainly as indifferent to her, as they were doubtless disagreeable to her friend in the clock. Release was not so soon at hand as the parties sanguinely expected, for though the miller slept, he took as secure a hold of his faithful dame, as if he had really been aware of the gaol-delivery she intended to accomplish. To her last resource, therefore, she was compelled to fly, for the morning was fast coming on. The miller's sleep was broken by the loud cries of his wife, who declared she was so ill, she was sure she should die. She yelled and screamed till the poor man in despair knew not what to do, and could only cry out What can I get you, What can I get you? Now the wily dame well knew that that would be the best for her complaint which was not in the house, so she vociferated Brandy, brandy, Oh for some brandy. The poor husband scrambled up some clothes, and set off for the nearest public house for some brandy, which was nearly a mile from his abode. Arriving there, he knocked up the landlord, who administered the medicine to him. To pay for which, the distressed husband put his hand in his breeches' pocket, and much to his own surprise, pulled out a large bundle of bank notes, at which he stared in amazement; when the landlord cried out, Lord! you have got Mr. Farrer's breeches on. Buckskins, it seems, well known in the neighbourhood.

"The Devil I have," returned the miller, in a tone which came up like a groan, as he gazed upon his nether man. Quickly comprehending the secret of the exchange, he pocketed the notes, drank up the brandy for his own consolation, and went home, moralizing his pensive path, and gave the hypocritical culprit the soundest beating she ever had in her life. She, poor soul! who had been charitably employed in the meanwhile, in letting the bird out of his cage, was not prepared for this reception; nor did she understand it until the next morning, when the breeches were cried round the town by her malignant husband, who also with no pleasant expression of countenance, made a point of turning over his newly-acquired riches in her presence.

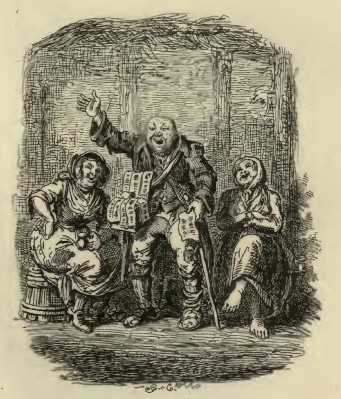

RECITATIVO. When lyart leaves bestrow the yird, Or wavering like the Bauckie-bird *, Bedim cauld Boreas' blast; When hailstanes drive wi' bitter skyte, And infant frosts begin to bite, In hoary cranreuch drest; Ae night at e'en a merry core O' randie, gangrel bodies,

To drink their orra duddies****: Wi' quaffing, and laughing, They ranted an' they sang; Wi' jumping, an' thumping, The vera girdle rang. * The "bat". ** A whiskey house. *** Frolic. **** Superfluous rags.

First, neist the fire, in auld red rags, Ane sat, weel brac'd wi' mealy bags, And knapsack a' in order; His doxy lay within his arm, Wi' usquebae an' blankets warm, She blinket on her sodger: An' ay he gies the tozie drab The tither skelpan kiss, While she held up her greedy gab Just like an aumous* dish: Ilk smack still, did crack still, Just like a cadger's** whip; Then staggering, an' swaggering, He roar'd this ditty up—

AIR. Tune—Soldier's Joy.

I. I am a son of Mars, who have been in many wars, And shew my cuts and scars wherever I come; This here was for a wench, and that other in a trench, When welcoming the French at the sound of the drum. Lai de daudle, &c. II. My prenticeship I past, where my leader breath'd his last, When the bloody die was cast on the heights of Abram; I served out my trade, when the gallant game was play'd, And the Moro low was laid at the sound of the drum. * A plate for receiving alms. ** A man who travels the country, with his wares on the back of a horse or ass.

III. I lastly was with Curtis, among the floating batt'ries, And there I left for witness, an arm and a limb; Yet let my country need me, with Elliot to head me, I'll clatter on my stumps at the sound of a drum. IV. And now tho' I must beg, with a wooden arm and leg, And many a tatter'd rag hanging over my———, I'm as happy with my wallet, my bottle and my callet*, As when I us'd in scarlet to follow a drum. V. What tho' with hoary locks, I must stand the winter shocks, Beneath the woods and rocks oftentimes for a home, When the tother bag I sell, and the tother bottle tell, I could meet a troop of hell at the sound of a drum.

RECITATIVO. He ended; and the kebars** sheuk Aboon the chorus roar; While frighted rattons backward leuk, An' seek the benmost bore***; A Merry Andrew i' the neuk, He skirl'd out, encore! But up arose the martial chuck, An' laid the loud uproar. *Wench. **Rafters. ***Deepest recess. AIR. Tune—Sodger Laddie.

I. I once was a maid, tho' I cannot tell when, And still my delight is in proper young men: Some one of a troop of dragoons was my daddie, No wonder I'm fond of a sodger laddie. Sing, Lal de lal, &c.

II. The first of my loves was a swaggering blade, To rattle the thundering drum was his trade; His leg was so tight and his cheek was so ruddy, Transported was I with my sodger laddie.

III. But the godly old chaplain left him in the lurch, The sword I forsook for the sake of the church; He ventur'd the soul, and I risked the body, 'Twas then I prov'd false to my sodger laddie.

IV. Full soon I grew sick of my sanctified sot, The regiment at large for a husband I got; From the gilded spontoon to the fife I was ready, I asked no more but a sodger laddie.

V. But the peace, it reduc'd me to beg in despair, Till I met my old boy at a Cunningham fair; His rags regimental they flutter'd so gaudy, My heart it rejoic'd at my sodger laddie.

VI. And now I have lived—I know not how long, And still I can join in a cup and a song: But whilst with both hands I can hold the glass steady, Here's to thee, my hero, my sodger laddie. Sing, Lal de dal, &c.

RECITATIVO. Poor Merry Andrew in the neuk Sat guzzling wi' a tinkler hizzie; They mind't na wha the chorus teuk, Between themsels they were sae busy. At length wi' drink and courting dizzy, He stoiter'd up an' made a face; Then turn'd an' laid a smack on Grizzy, Syne tun'd his pipes wi' grave grimace.

AIR. Tune—Auld Sir Simon. Sir Wisdom's a fool when he's fou, Sir Knave is a fool in a session; He's there but a prentice, I trow, But I am a fool by profession. My Grannie she bought me a beuk, An' I held awa to the school; I fear I my talent misteuk, But what will ye hae of a fool. For drink I would venture my neck; A hizzie's the half of my craft; But what could ye other expect Of ane that's avowedly daft. I ance was ty'd up like a stirk, For civilly swearing and quaffing; I ance was abus'd i' the Kirk, For towzing a lass i' my daffin. Poor Andrew that tumbles for sport, Let naebody name wi' a jeer; There's ev'n, I'm tauld, i' the court, A Tumbler ca'd the Premier. Observ'd ye yon reverend lad Mak faces to tickle the mob; He rails at our mountebank squad, It's rivalship just i' the job. And now my conclusion I'll tell, For faith I'm confoundedly dry, The chiel that's a fool for himsel, Guid Lord, he's far dafter than I.

RECITATIVO. Then neist outspak a raucle carlin*, Wha kent fu' weel to cleek the sterlin'; For mony a pursie she had hooked, An' had in mony a well been douked: Her Love had been a Highland laddie, But weary fa' the waefu' woodie**! Wi' sighs and sobs she thus began, To wail her braw John Highlandman.

AIR. Tune—O an ye were dead, Gudeman.

I. A highland lad my love was born, The Lalland laws he held in scorn; But he still was faithfu' to his clan, My gallant, braw John Highlandman!

CHORUS. Sing hey my braw John Highlandman! Sing ho my brazo John Highlandman! There's not a lad in a' the lan' Was match for my John Highlandman! * A sturdy raw-boned dame. ** The gallows.

II. With his philibeg an' tartan plaid, An' guid claymore down by his side, The ladies' hearts he did trepan, My gallant, braw John Highlandman. Sing, hey, &c.

III. We ranged a' from Tweed to Spey, An' liv'd like lords an' ladies gay; For a lalland face he feared none, My gallant, braw John Highlandman. Sing, hey, &c.

IV. They banish'd him beyond the sea, But ere the bud was on the tree, Adown my cheeks the pearls ran, Embracing my John Highlandman. Sing, hey, &c.

V. But och! they catch'd him at the last, And bound him in a dungeon fast; My curse upon them every one, They've hang'd my braw John Highlandman. Sing, hey, &c.

VI. And now a widow I must mourn, Departed joys that ne'er return; No comfort but a hearty can, When I think on John Highlandman. Sing, hey, &c.

RECITATIVO. A pigmy scraper wi' his fiddle, Wha us'd to trystes and fairs to driddle. Her strappen limb an' gausy middle, (He reach'd na higher,) Had hol'd his heartie like a riddle, An' blawn't on fire. W' hand on hainch, an' upward e'e, He croon'd his gamut, one, two, three, Then in an arioso key, The wee Apollo Set off wi' allegretto glee His giga solo.

AIR. Tune—Whistle owre the lave o't. Let me ryke up to dight that tear, An' go wi' me an' be my dear; An' then your every care and fear May whistle owre the lave o't.

CHORUS. I am fidler to my trade, An' at the tunes that e'er I play'd, The sweetest still to wife or maid, Was, whistle owre the lave o't. At kirns an' weddins we'se be there, An' O sae nicely's we will fare! We'll bowse about till Dadie Care Sing whistle owre the lave o't. I am, &c. Sae merrily's the banes we'll pyke, An' sun oursells about the dyke; An' at our leisure when ye like We'll—whistle owre the lave o't.— I am, &c. But bless me wi' your heav'n o' charms, And while I kittle * hair on thairms, Hunger, cauld, an' a' sic harms May whistle owre the lave o't. I am, &c. RECITATIVO. Her charms had struck a sturdy Caird **, As weel as poor Gutscraper; He taks the fiddler by the beard, An' draws a roosty rapier— He swoor by a' was swearing worth, To speet him like a pli ver, Unless he would from that time forth Relinquish her for ever:

Wi' ghastly e'e, poor tweedle-dee, Upon his hunkers*** bended, An' pray'd for grace wi' ruefu' face, An' so the quarrel ended; But tho' his little heart did grieve, When round the tinker prest her, He feign'd to snirtle in his sleeve, When thus the Caird address'd her * While I rub a horse-hair bow upon cat-gut. ** Tinker. ***Haunches.

AIR. Tune—Clout the Caudron. I.. My bonie lass I work in brass, A tinkler is my station; I've travell'd round all Christian ground In this my occupation; I've ta'en the gold, I've been enroll'd In many a noble squadron; But vain they search'd, when off I march'd To go an' clout the caudron. I've ta 'en the gold, &c.

II. Despise that shrimp, that wither'd imp, With a' his noise an' caprin; An' take a share with those that bear The budget an' the apron! An' by that stowp, my faith an' houpe, An' by that dear Kilbaigie*! If e'er ye want, or meet with scant, May I ne'er weet my craigie. An' by that stowp, &c.

RECITATIVO. The Caird prevail'd—th' unblushing fair In his embraces sunk; Partly wi' love o'ercome sa sair, An' partly she was drunk: Sir Violino, with an air, That show'd a man o' spunk, Wish'd unison between the pair, An' made the bottle clunk To their health that night. * A well known kind of whiskey. But hurchin Cupid shot a shaft, That play'd a dame a shavie— A sailor rak'd her fore and aft, Behind the chicken cavie. Her lord a wight o' Homer's craft, Tho' limpan wi' the spavie, He hirpl'd up an' lap like daft, An shor'd * them Dainty Davie O'boot that night. He was a care-defying blade, As ever Bacchus listed! Tho' fortune sair upon him laid, His heart, she ever miss'd it: He had no wish but—to be glad, Nor want but—when he thirsted; He hated nought but—to be sad, An' thus the Muse suggested His sang that night.

AIR. Tune—for a' that, an' a' that.

I. I am a bard of no regard Wi' gentle-folks, an' a' that; But Homer-like, the glowran byke**, Frae town to town I draw that.

CHORUS. For a' that, an' a' that, An' twice as muckle's a' that, I've lost but ane, I've twa behin' I've wife eneugh 'or a' that. * Promised. ** The multitude. II. I never drank the Muses' tank, Castalia's burn an' a' that; But there it streams, an' richly reams My Helicon I ca' that. For a' that, &c.

III. Great love I bear to all the Fair, Their humble slave, an' a' that; But lordly Will, I hold it still A mortal sin to thraw that. For a' that, &c.

IV. In raptures sweet, this hour we meet, Wi' mutual love an' a' that; But for how lang the flie may stang, Let Inclination law that. For a' that, &c.

V. Their tricks an' craft hae put me daft, They've ta'en me in, an' a' that; But clear your decks, an' here's the Sex! I like the jads for a' that. For a' that, an a' that, An' twice as muckle's a' that, My dearest bluid, to do them guid, They're welcome till't for a' that.

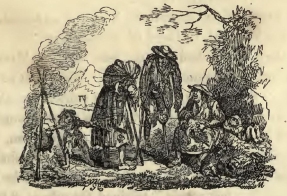

RECITATIVO. So sung the Bard—and Nansie's waws Shook wi' a thunder of applause, Re-echo'd from each mouth! They toom'd * their pokes, they pawn'd their duds**, They scarcely left to coor their fuds, To quench their lowan drouth.

Then owre again, the jovial thrang, The poet did request, To lowse his pack an' wale a sang, A ballad o' the best.. He, rising, rejoicing, Between his two, Deborahs, Looks round him, an' found them Impatient for the chorus. * Opened. **Rags.

AIR. Tune—JOLLY MORTALS, fill your glasses.

I. See! the smoking bowl before us, Mark our jovial, ragged ring! Round and round take up the chorus, And in raptures let us sing— A fig for those by law protected, Liberty's a glorious feast! Courts for cowards were erected, Churches built to please the priest. What is title, what is treasure, What is reputation's care? If we lead a life of pleasure, 'Tis no matter how or where. A fig, &c. III. With the ready trick and fable, Round we wander all the day; And at night, in barn or stable, Hug our doxies on the hay. A fig, &c.

IV. Does the train-attended carriage Thrp' the country lighter rove? Does the sober bed of marriage Witness brighter scenes of love? A fig, &c. V. Life is all a variorum, We regard not how it goes; Let them cant about, decorum Who have character to lose. A fig, &c.

VI. Here's to budgets, bags, and wallets! Here's to all the wandering train! Here's our ragged brats and callets! One and all cry out, Amen! A fig for those by law protected, Liberty's a glorious feast! Courts for cowards were erected, Churches built to please the priest.

In the year of 1460, Revel was governed by a General, whose name was John of Mengden; a worthy old man, who loved his glass of wine, and had the gout; for wine and the gout are sister's children. It was his custom to ride out occasionally on a black horse down to the shores of the Baltic, whence he continued his way to a convent of nuns consecrated to St. Bridget. This nunnery, which was called Marianthal, was situated about a mile from the town, and its ruins are inhabited by owls and ravens.

On one of these excursions he was accompanied by the Lord Marshal, Gothard of Plettenberg.

As they approached the convent wall, the Marshal's horse became suddenly restive. "Have you heard," said he, "the strange, stories of the subterraneous passage, and that it winds in intricate mazes round the cloister?"—— "No," replied John of Mengden, "but I should like to hear them over a bottle; you shall relate them to me in the evening."

"It may be done now, and in a few words," rejoined the other; "for we stand exactly before the subterraneous passage, or mouth of the cavern; but for fifty years, not a human foot has advanced beyond the bottom of the steps, there the torches are always blown out."

The burgomaster of Revel, who was then with them, made a cross on his breast, and confirmed the statement. "Sometimes," continued Gothard, "are heard, during the night, the sounds of soft music, arising slowly and melodiously from the cave, like the sweet tones of musical glasses, with an accompaniment of the songs of angels. The holy sisters of the convent are frequent listeners to this divine harmony, though none of the words can be understood."

"Let the venerable Lady Abbess come down to me," said the general, as he alighted from his horse, and placed his glove in his sword-belt. The Abbess now appeared, veiled. She modestly curtsied to the knight, and presented him with a cup of Spanish wine. The old General laid himself down on the grass, and asked the sainted lady if she could give him any information relative to the subterraneous passage? The Abbess replied in the affirmative, adding a number of particulars concerning what she and her pious sisters had seen,—and fancied they had seen—heard, and fancied they had heard.

"So God and St. Vitus help me!" exclaimed the governor, "I will myself make an attempt to descend into the cavern; give me a lighted, consecrated torch."

The burgomaster crossed himself all over. A cold shivering seized him; the only vault into which he had been accustomed to descend, was the town-cellar which was haunted by none but choice spirits, with which he was familiar.

The lady Abbess entreated the old man not to undertake so rash an enterprize; and assured him, that the spirits of former times, unlike those of the present day, would not allow themselves to be sported with. But in arguing with the brave old General, they talked to the wind which blew over the Baltic. The consecrated torches were brought, the corpulent General repeated an Ave-Maria, recommended himself to St. Vitus, his protecting Saint, and courageously entered the mysterious passage. The sound of his feet was still heard on the steps; his breathing was still audible, and the glimmer of his torch played on the damp walls. On a sudden all was silent, and the light disappeared. The listeners above were on the stretch of attention. Go-thard was stationed on the upper step; the burgomaster a few paces further back; and behind him stood the Abbess, her rosary running through her fingers. They listened, but all was still! "Holloa there, John of Mengden!—how fare you?" thundered the voice of Gothard; yet all was still as the grave. The listeners were alarmed; they inclined their ears; they stood lightly on tip-toe; they restrained their breath—not a sound ascended. The cavern yawned before them, and all was silent below; "Holy St. Bridget! what can have happened? Let the priests be summoned, and mass be said, to appease the spirits!"

The lady Abbess hastened to the convent, rang the chapel-bell, when all the pious sisterhood hurried from their cells, fell upon their bare knees, chastizing themselves, and praying to heaven for mercy towards the old General. The burgomaster threw himself upon his horse, and trotted back to the town to impart the terrible news to his wife, children and domestics. Gothard, who was a courageous knight, alone remained, absorbed in gloomy reflection, leaning against the wall, with his eyes fixed on the darkness beneath. Thus he continued during two hours. At last he thought he heard on the steps, some one breathing and struggling.—"John of Mengden!" he vociferated—"are you alive, or dead?"—-"I am alive!" replied the General, half breathless, as he stumbled up the steps. "Thanks to God and St. Bridget!—we have been in agony on your account. Where have you been? What have you heard or seen?" The General then related that he had quietly descended, with the consecrated taper in his hand; that his heart beat a little as he advanced; that a cold shiver had begun to seize him; but that he took courage, as his taper burnt always clear and bright: that at length he stood on the bottom step, and looked down an endless passage, doubtful whether, under the protection of St. Bridget, he should move forward or backward; that suddenly he was surrounded by a lukewarm breeze, mild and fragrant, as if wafted over a bed of flowers, which in a moment extinguished his taper, and so clouded his senses, that he sunk like a dead man on the steps, and then lay a considerable time in a sort of trance; that at last he awoke again, and it appeared to him as if he were gently moved by a warm hand, though he knew not where he was, nor what had happened to him; that he stretched out his hands, and felt nothing but the cold stone; but that, as a little daylight glimmered upon him from above, he composed his spirits, and began to creep with difficulty up the steps; that when on them he was perfectly recovered, feeling only a slight oppression in the head, similar to the effect of intoxication.

"Well, brother," said he to the lord-marshal, "will not you also make the attempt, and try whether it will not succeed better with you."

Gothard of Plettenberg demurred: notwithstanding he never feared, in former times, a knight of flesh and bone, as long as he was able to wield his sword; yet, with respect to ghosts, a very just exception was allowed; and a knight might tremble in the dark like an old woman, without any stain upon his honor, or impeachment of his valour. Now a days, the matter is quite altered, and a man may fear any thing but ghosts.

"By my sword," said the governor, as he was returning home, "I will investigate the causes of this mystery. I must know from whose mouth proceeded the gentle breath, that smelt fragrant as the plants of the east, and yet had force enough to extinguish the flame of the consecrated taper, and even to confuse my head, as though I had been drunk."

He instantly sent for Henry of Uxkull, bishop of Revel, and the Abbot, of Pardis. Being arrived, they were entertained at a large oak table, and quaffed wine from the family goblet. They listened to the fearful story of their host, with their fat hands folded upon their huge bellies, and shook their heads with significant silence.

Having well weighed the matter, knitted their brows and assumed an air of importance, they finally agreed that they knew not what to think of it. Each then waddled to his home and thought no more of the mysterious cavern.

But it was not so with the General. He could not rest. His fancy was on the rack, to account for the mystery. On the next morning, he despatched letters to the Archbishop of Riga, to a learned canon, and two pious deans of the holy church of Riga—stating "that a surprising incident had obliged him to have recourse to their piety and wisdom, and entreating that they would be at Revel on St. Egidius's day, to discuss in Christian humility this weighty affair."

They came on the appointed day: for they were aware that the cellar of the Governor contained excellent wine, and that his was no niggard hospitality. The archbishop of Revel, and the Abbot of Pardis, were likewise invited to assist, who failed not at the proper hour to present themselves at the castle. An elegant repast had been prepared for them, bumpers went cheerily round to the prosperity of Holy Church, and to the perpetual bloom of the German order of religion. When their spiritual stomachs were sufficiently gorged, the General thus addressed them: "Reverend and pious fathers! thus and thus it happened to me and my friend here, Gothard of Plettenberg," recounting his story—"What is to be done to liberate the spirits who wander and breathe in the subterraneous passage?"

"They must be driven out by force," replied the archbishop of Riga, "and the power to do this was given to bishops from above."

"A wisp of hay should be steeped in holy water," added the canon, "with which the steps of the dark passage should be sprinkled."

One of the deans advised that "the little chest with the Egyptian hieroglyphics, which was kept as a relic in the convent of St. Bridget, should be taken to the cavern.".

The other dean was of opinion that the spirits should be allowed to continue without molestation so long as they only wandered and breathed.

The archbishop of Revel was also of the same sentiment, but the Abbot of Pardis applauded this idea of the Egyptian hieroglyphics.

Last of all, the old General proposed that they should immediately ride to the beach, and employ the arms of the church against the inhabitants of the subterraneous passage. The wine had imparted its spirit to the holy fathers; and they now felt courage to engage, if necessary, even with the fiends of hell.

Within half an hour they were at the convent gate!

Three times were the consecrated torches borne round by the archbishop, who, muttering between his teeth, dipped the wisp into a large ewer of holy water, and plentifully besprinkled all present; Thus spiritually armed, they silently and cautiously approached the entrance of the cavern. Here a question arose, "who should go down first?" Those who were at home were unwilling to rob the strangers of the honor of precedence. The deans drew back, as being merely subalterns in the church, out of respect to their bishop. The archbishop bowed to the right learned canon, and he bowed to the rest. The General became impatient, and forced the archbishop down the steps. The rest followed with beating hearts and tottering knees.

Each carried in his hand a consecrated taper; and with a rosary hanging at his elbow, sprinkled the walls with drops of holy water. The last of the procession was the Abbot of Pardis, who, grown unwieldy by the luxurious diet of the church, could scarcely drag his short puffed legs after his fat and bulky paunch. The steps too were not only small, but damp and slippery; whence it happened, that on the second step the Abbot lost his footing, and falling with his whole weight upon Henry of Uxkull, they both fell upon the last dean: all three on the first dean; all four on the canon; all five upon the archbishop of Riga; when the whole troop rolled helter skelter down the steps, and plumped to the bottom like so many sacks, there remaining senseless!

The consecrated tapers were extinguished, and the venerable group were veiled by a sort of Egyptian darkness. The General, who remained above, heard the tremendous rumbling, to which succeeded a dead silence. For two hours he listened, called on each by name, and waited in vain for a reply. His voice alone was returned to him in a dull and hollow echo. The only sound which met his eager listening, was that of the terrified bat, flitting in the depths of the cavern; or, at intervals, the scream of the frightened owl.

He was a man of uncommon courage, and he resolved to descend once more himself, to see what was become of his guests; but as a prelude to this perilous expedition, he determined to enliven his natural spirits by a draught of generous wine. As he vociferated—"a cup of wine," to the groom who held his horse, the word Wine reached the ears of the holy men—they disentangled themselves from each other, scrambled up, their foreheads bedewed with the sweat of terror, and when they had recovered themselves, they confessed unanimously that they were not able to unravel the mystery.

Thus ended the second attempt to gain a more intimate acquaintance with the spirits of the subterraneous passage, and thenceforward no one was bold enough to tread the magic ground.

When the Cardinal Bernis resided at Rome in the capacity of Ambassador from France, he bore the highest character for sanctity—yet the Cardinal was a man, though a churchman; and churchmen are sometimes not invulnerable to the shafts of love. A pair of speaking black eyes like those of the Princess B., have before now made sad havoc in the heart of the votary of celibacy. The lady was conscious of her own charms, but being married to the man she loved, instead of setting them off by certain little manouvres which some ladies perfectly understand how to put in practice, she carefully avoided giving any encouragement to the Cardinal, whose constant attendance upon her began to give her some uneasiness. At length the Cardinal, finding that his visits, attentions, cadeaux, and fine speeches had no effect, determined upon seeking an opportunity of making the lady sensible of the excess of his passion. One morning the Princess, on returning from mass, in her haste to avoid a violent shower of rain, tripped as she was getting out of her carriage, and sprained her ancle. The Cardinal, who by his spies was informed of every step the Princess took, had attended at mass also; and as he was following the Princess, unobserved, he saw the accident and ran to her assistance, raised her into the carriage, and very humbly entreated her to allow him the honour of seeing her safe home. His Excellency was not to be refused consistently with etiquette, so the poor Princess was under the necessity of hearing all the pretty things the Ambassador had reserved for the occasion. All his protestations and entreaties proved fruitless, and the poor lady arrived at the palace almost exhausted with the alarm the conversation had caused her. She now endeavoured with all care to avoid receiving the Cardinal's visits, but the old gentleman's amorous plans were not to be thwarted.—He still found means of seeing her, and again attacked her with his vows and protestations, so that the lady, unable to bear it any longer, determined to inform the Prince, and related to him all the circumstances of the affair. The Prince was enraged, and threatened all kinds of vengeance against the lover; but however, when the first burst of passion had a little subsided, he said to her, "We are, my love, in a very aukward situation, for the Cardinal being Ambassador his person is sacred; besides we should have the whole consistory and his holiness at their head, thundering excommunication upon us. However, I will think of some scheme of cooling the passion of this holy gentleman." He accordingly suggested that she should write word to the Cardinal, that as her husband was going that evening to his Villa near Tivoli, to order some improvement to be made which would detain him the best part of next day, she had determined to admit a visit from him; but that in order to keep the matter a secret from the servants, she desired him to come at midnight; that she would fix a silken ladder at her room window which looked into the garden, whence he might easily ascend into the anti-room, where he would find the door open that led into her own room. The reader will naturally conceive the transports which this delicious billet excited in the worthy Cardinal. He danced, and leaped and capered about for joy, rang the bell, gave contradictory orders, and convinced his valet that he was mad. He had the sense however to direct a suit of his finest linen to be prepared, and to countermand the order for his carriage, for he bethought himself he had better go privately. How tedious did the hours, which intervened before the time of appointment, appear to our ardent lover, and when the clock struck eleven he could no longer wait. It was a good distance, he must be there in time, not a second too late; therefore off he set after taking some precautions against his sacred person being discovered. He arrives, panting with love and hope; the burning of Mongibello could scarcely exceed the conflagration within him. He gets to the garden-gate. One cannot think of every thing. The Princess in her flurry had forgotten to order the garden-gate to be left open. What was to be done? The wall was not high; but must his Eminence endanger his sacred person? Love, however, the sovereign ruler, who makes even cowards heroes, animated him. It was dreadfully dark; but luckily, in feeling for the height of the wall, the anxious lover found an aperture in it large enough to admit the foot: into this he stepped, gave a spring, and got to the top; and then slid down the other side, not however without losing his hat and cloak, which owing to the darkness of the night he could not find again, nor was he aware, for the same reason, how he was daubed with mortar and brick-dust. In this pickle, our Adonis made the best of his way to find the ladder, tumbling over orange-trees and rosebushes, to the manifest injury of his cassock, which began to hang about him in rags. At last he reached the ladder, seized hold of it, stopped, panted a while for breath, and then up he went. He had just got one leg through the window, when the two large folding doors of the apartment flew open, and fifteen or twenty servants with lighted torches in their hands presented themselves before him.

The Prince, at their head, ran up to the window, and with all courtesy helped in the astonished Cardinal, and turning to the servants said, "Scoundrels! is it thus you pay respect to the sacred person of the Cardinal Bernis? Is it thus, by your negligence, that you compel his Eminence, when coming to my wife, to venture his precious life upon a slight ladder and force him through the window in this miserable plight?" Conceive the situation of the bald-pated, cloakless, and tattered Cardinal, as he stood ashamed and terrified before the jeering Prince and his twenty torchbearers. His trembling knees could scarcely support him, as, half dead with fright, shame, and disappointment, he sneaked out of the room, still lighted by the torches and bowed out by the Prince, who continued to apologize for the carelessness of his servants, much to the annoyance of the poor Cardinal, whose misery was heightened by one stroke more; for, as he was huddling off, he just caught the face of the Princess, peeping through the opening of a door with some friends, all almost convulsed with laughter.