“Upon my word, friend,” said I, “you have almost made me long to try what a robber I should make.” “There is a great art in it, if you did,” quoth he. “Ah! but,” said I, “there's a great deal in being hanged.” Life and Actions of Guzman d'Alfarache.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER XV. THE ROBBERY IN WILLESDEN CHURCH.

CHAPTER XVI. JONATHAN WILD'S HOUSE IN THE OLD BAILEY.

CHAPTER XVII. THE NIGHT-CELLAR.

CHAPTER XVIII. HOW JACK SHEPPARD BROKE OUT OF THE CAGE AT WILLESDEN.

EPOCH THE THIRD, THE PRISON-BREAKER, 1724.

CHAPTER II. THE BURGLARY AT DOLLIS HILL.

CHAPTER III. JACK SHEPPARD'S QUARREL WITH JONATHAN WILD.

CHAPTER IV. JACK SHEPPARD'S ESCAPE FROM THE NEW PRISON.

CHAPTER VI. WINIFRED RECEIVES TWO PROPOSALS.

CHAPTER VII. JACK SHEPPARD WARNS THAMES DARRELL.

CHAPTER X. HOW JACK SHEPPARD GOT OUT OF THE CONDEMNED HOLD.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

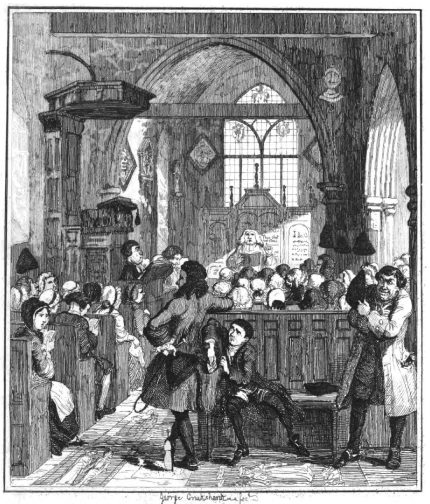

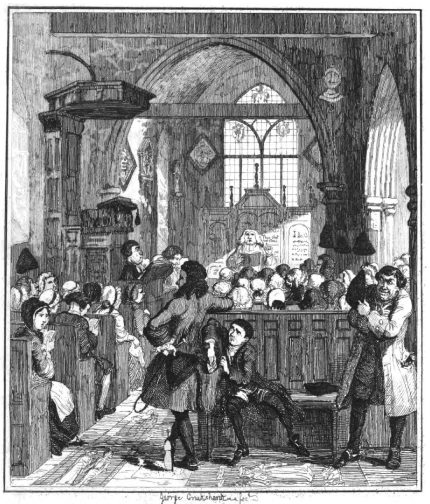

Frontispiece: Jack Shepard committing the Robbery in Willesden Church

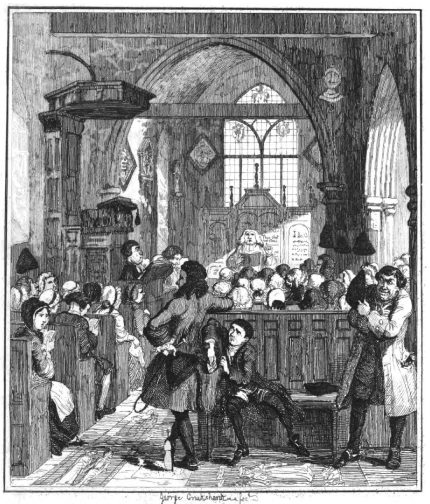

Jack Sheppard gets drunk, and orders his Mother off

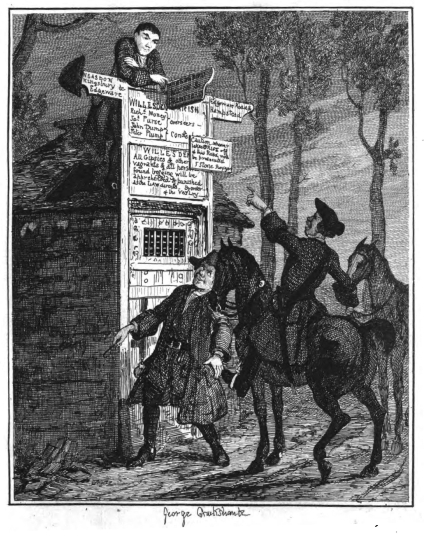

Jack Sheppard's escape from Willesden Cage

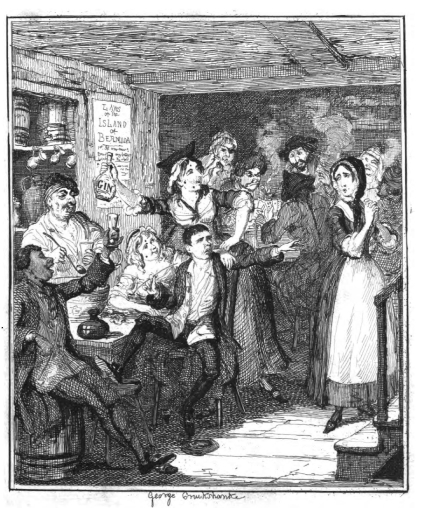

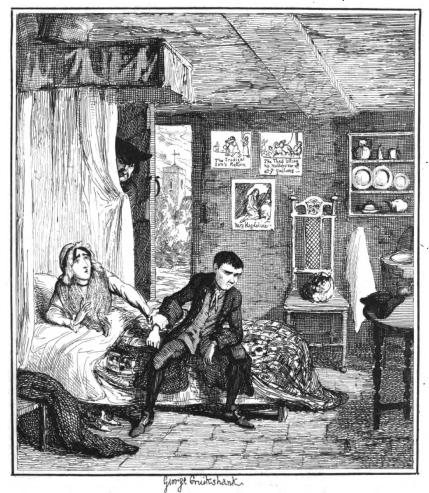

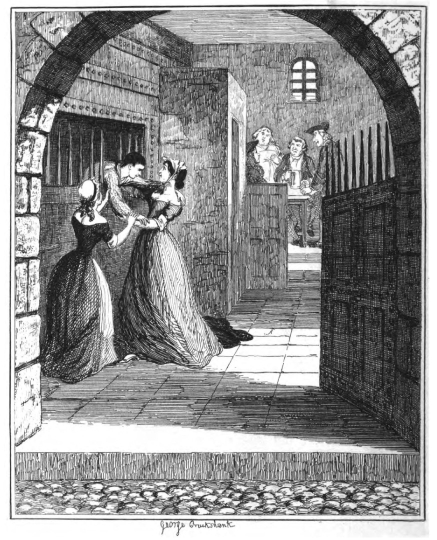

Mrs. Sheppard expostulating with her Son

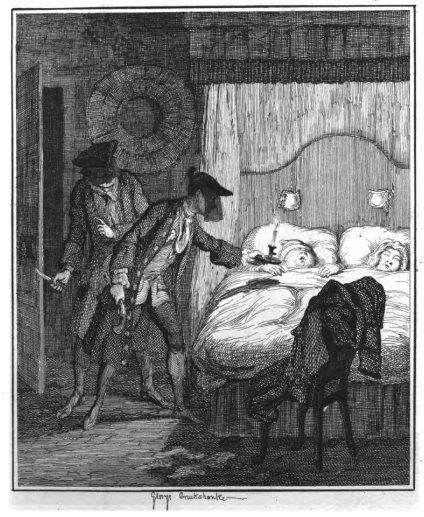

Jack Sheppard and Blueskin in Mr.Wood's Bedroom

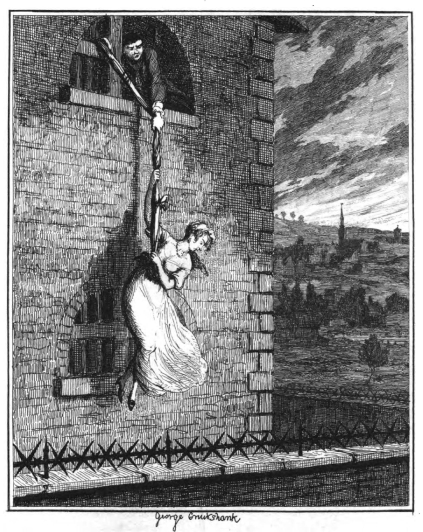

Jack Sheppard and Edgeworth Bess escaping from Clerkenwell Prison

Jack Sheppard escaping from the Condemned Hold in Newgate

The household of the worthy carpenter, it may be conceived, was thrown into the utmost confusion and distress by the unaccountable disappearance of the two boys. As time wore on, and they did not return, Mr. Wood's anxiety grew so insupportable, that he seized his hat with the intention of sallying forth in search of them, though he did not know whither to bend his steps, when his departure was arrested by a gentle knock at the door.

“There he is!” cried Winifred, starting up, joyfully, and proving by the exclamation that her thoughts were dwelling upon one subject only. “There he is!”

“I fear not,” said her father, with a doubtful shake of the head. “Thames would let himself in; and Jack generally finds an entrance through the backdoor or the shop-window, when he has been out at untimely hours. But, go and see who it is, love. Stay! I'll go myself.”

His daughter, however, anticipated him. She flew to the door, but returned the next minute, looking deeply disappointed, and bringing the intelligence that it was “only Mrs. Sheppard.”

“Who?” almost screamed Mrs. Wood.

“Jack Sheppard's mother,” answered the little girl, dejectedly; “she has brought a basket of eggs from Willesden, and some flowers for you.”

“For me!” vociferated Mrs. Wood, in indignant surprise. “Eggs for me! You mistake, child. They must be for your father.”

“No; I'm quite sure she said they're for you,” replied Winifred; “but she does want to see father.”

“I thought as much,” sneered Mrs. Wood.

“I'll go to her directly,” said Wood, bustling towards the door. “I dare say she has called to inquire about Jack.”

“I dare say no such thing,” interposed his better half, authoritatively; “remain where you are, Sir.”

“At all events, let me send her away, my dear,” supplicated the carpenter, anxious to avert the impending storm.

“Do you hear me?” cried the lady, with increasing vehemence. “Stir a foot, at your peril.”

“But, my love,” still remonstrated Wood, “you know I'm going to look after the boys——”

“After Mrs. Sheppard, you mean, Sir,” interrupted his wife, ironically. “Don't think to deceive me by your false pretences. Marry, come up! I'm not so easily deluded. Sit down, I command you. Winny, show the person into this room. I'll see her myself; and that's more than she bargained for, I'll be sworn.”

Finding it useless to struggle further, Mr. Wood sank, submissively, into a chair, while his daughter hastened to execute her arbitrary parent's commission.

“At length, I have my wish,” continued Mrs. Wood, regarding her husband with a glance of vindictive triumph. “I shall behold the shameless hussy, face to face; and, if I find her as good-looking as she's represented, I don't know what I'll do in the end; but I'll begin by scratching her eyes out.”

In this temper, it will naturally be imagined, that Mrs. Wood's reception of the widow, who, at that moment, was ushered into the room by Winifred, was not particularly kind and encouraging. As she approached, the carpenter's wife eyed her from head to foot, in the hope of finding something in her person or apparel to quarrel with. But she was disappointed. Mrs. Sheppard's dress—extremely neat and clean, but simply fashioned, and of the plainest and most unpretending material,—offered nothing assailable; and her demeanour was so humble, and her looks so modest, that—if she had been ill-looking—she might, possibly, have escaped the shafts of malice preparing to be levelled against her. But, alas! she was beautiful—and beauty is a crime not to be forgiven by a jealous woman.

As the lapse of time and change of circumstances have wrought a remarkable alteration in the appearance of the poor widow, it may not be improper to notice it here. When first brought under consideration, she was a miserable and forlorn object; squalid in attire, haggard in looks, and emaciated in frame. Now, she was the very reverse of all this. Her dress, it has just been said, was neatness and simplicity itself. Her figure, though slight, had all the fulness of health; and her complexion—still pale, but without its former sickly cast,—contrasted agreeably, by its extreme fairness, with the dark brows and darker lashes that shaded eyes which, if they had lost some of their original brilliancy, had gained infinitely more in the soft and chastened lustre that replaced it. One marked difference between the poor outcast, who, oppressed by poverty, and stung by shame, had sought temporary relief in the stupifying draught,—that worst “medicine of a mind diseased,”—and those of the same being, freed from her vices, and restored to comfort and contentment, if not to happiness, by a more prosperous course of events, was exhibited in the mouth. For the fresh and feverish hue of lip which years ago characterised this feature, was now substituted a pure and wholesome bloom, evincing a total change of habits; and, though the coarse character of the mouth remained, in some degree, unaltered, it was so modified in expression, that it could no longer be accounted a blemish. In fact, the whole face had undergone a transformation. All its better points were improved, while the less attractive ones (and they were few in comparison) were subdued, or removed. What was yet more worthy of note was, that the widow's countenance had an air of refinement about it, of which it was utterly destitute before, and which seemed to intimate that her true position in society was far above that wherein accident had placed her.

“Well, Mrs. Sheppard,” said the carpenter, advancing to meet her, and trying to look as cheerful and composed as he could; “what brings you to town, eh?—Nothing amiss, I trust?”

“Nothing whatever, Sir,” answered the widow. “A neighbour offered me a drive to Paddington; and, as I haven't heard of my son for some time, I couldn't resist the temptation of stepping on to inquire after him, and to thank you for your great goodness to us both, I've brought a little garden-stuff and a few new-laid eggs for you, Ma'am,” she added turning to Mrs. Wood, who appeared to be collecting her energies for a terrible explosion, “in the hope that they may prove acceptable. Here's a nosegay for you, my love,” she continued, opening her basket, and presenting a fragrant bunch of flowers to Winifred, “if your mother will allow me to give it you.”

“Don't touch it, Winny!” screamed Mrs. Wood, “it may be poisoned.”

“I'm not afraid, mother,” said the little girl, smelling at the bouquet. “How sweet these roses are! Shall I put them into water?”

“Put them where they came from,” replied Mrs. Wood, severely, “and go to bed.”

“But, mother, mayn't I sit up to see whether Thames returns?” implored Winifred.

“What can it matter to you whether he returns or not, child,” rejoined Mrs. Wood, sharply. “I've spoken. And my word's law—with you, at least,” she added, bestowing a cutting glance upon her husband.

The little girl uttered no remonstrance; but, replacing the flowers in the basket, burst into tears, and withdrew.

Mrs. Sheppard, who witnessed this occurrence with dismay, looked timorously at Wood, in expectation of some hint being given as to the course she had better pursue; but, receiving none, for the carpenter was too much agitated to attend to her, she ventured to express a fear that she was intruding.

“Intruding!” echoed Mrs. Wood; “to be sure you are! I wonder how you dare show your face in this house, hussy!”

“I thought you sent for me, Ma'am,” replied the widow, humbly.

“So I did,” retorted Mrs. Wood; “and I did so to see how far your effrontery would carry you.”

“I'm sure I'm very sorry. I hope I haven't given any unintentional offence?” said the widow, again meekly appealing to Wood.

“Don't exchange glances with him under my very nose, woman!” shrieked Mrs. Wood; “I'll not bear it. Look at me, and answer me one question. And, mind! no prevaricating—nothing but the truth will satisfy me.”

Mrs. Sheppard raised her eyes, and fixed them upon her interrogator.

“Are you not that man's mistress?” demanded Mrs. Wood, with a look meant to reduce her supposed rival to the dust.

“I am no man's mistress,” answered the widow, crimsoning to her temples, but preserving her meek deportment, and humble tone.

“That's false!” cried Mrs. Wood. “I'm too well acquainted with your proceedings, Madam, to believe that. Profligate women are never reclaimed. He has told me sufficient of you—”

“My dear,” interposed Wood, “for goodness' sake—”

“I will speak,” screamed his wife, totally disregarding the interruption; “I will tell this worthless creature what I know about her,—and what I think of her.”

“Not now, my love—not now,” entreated Wood.

“Yes, now,” rejoined the infuriated dame; “perhaps, I may never have another opportunity. She has contrived to keep out of my sight up to this time, and I've no doubt she'll keep out of it altogether for the future.”

“That was my doing, dearest,” urged the carpenter; “I was afraid if you saw her that some such scene as this might occur.”

“Hear me, Madam, I beseech you,” interposed Mrs. Sheppard, “and, if it please you to visit your indignation on any one let it be upon me, and not on your excellent husband, whose only fault is in having bestowed his charity upon so unworthy an object as myself.”

“Unworthy, indeed!” sneered Mrs. Wood.

“To him I owe everything,” continued the widow, “life itself—nay, more than life,—for without his assistance I should have perished, body and soul. He has been a father to me and my child.”

“I never doubted the latter point, I assure you, Madam,” observed Mrs. Wood.

“You have said,” pursued the widow, “that she, who has once erred, is irreclaimable. Do not believe it, Madam. It is not so. The poor wretch, driven by desperation to the commission of a crime which her soul abhors, is no more beyond the hope of reformation than she is without the pale of mercy. I have suffered—I have sinned—I have repented. And, though neither peace nor innocence can be restored to my bosom; though tears cannot blot out my offences, nor sorrow drown my shame; yet, knowing that my penitence is sincere, I do not despair that my transgressions may be forgiven.”

“Mighty fine!” ejaculated Mrs. Wood, contemptuously.

“You cannot understand me, Madam; and it is well you cannot. Blest with a fond husband, surrounded by every comfort, you have never been assailed by the horrible temptations to which misery has exposed me. You have never known what it is to want food, raiment, shelter. You have never seen the child within your arms perishing from hunger, and no relief to be obtained. You have never felt the hearts of all hardened against you; have never heard the jeer or curse from every lip; nor endured the insult and the blow from every hand. I have suffered all this. I could resist the tempter now, I am strong in health,—in mind. But then—Oh! Madam, there are moments—moments of darkness, which overshadow a whole existence—in the lives of the poor houseless wretches who traverse the streets, when reason is well-nigh benighted; when the horrible promptings of despair can, alone, be listened to; and when vice itself assumes the aspect of virtue. Pardon what I have said, Madam. I do not desire to extenuate my guilt—far less to defend it; but I would show you, and such as you—who, happily, are exempted from trials like mine—how much misery has to do with crime. And I affirm to you, on my own conviction, that she who falls, because she has not strength granted her to struggle with affliction, may be reclaimed,—may repent, and be forgiven,—even as she, whose sins, 'though many, were forgiven her'.

“It gladdens me to hear you talk thus, Joan,” said Wood, in a voice of much emotion, while his eyes filled with tears, “and more than repays me for all I have done for you.”

“If professions of repentance constitute a Magdalene, Mrs. Sheppard is one, no doubt,” observed Mrs. Wood, ironically; “but I used to think it required something more than mere words to prove that a person's character was abused.”

“Very right, my love,” said Wood, “very sensibly remarked. So it does. Bu I can speak to that point. Mrs. Sheppard's conduct, from my own personal knowledge, has been unexceptionable for the last twelve years. During that period she has been a model of propriety.”

“Oh! of course,” rejoined Mrs. Wood; “I can't for an instant question such distinterested testimony. Mrs. Sheppard, I'm sure, will say as much for you. He's a model of conjugal attachment and fidelity, a pattern to his family, and an example to his neighbours. Ain't he, Madam?'”

“He is, indeed,” replied the widow, fervently; “more—much more than that.”

“He's no such thing!” cried Mrs. Wood, furiously. “He's a base, deceitful, tyrannical, hoary-headed libertine—that's what he is. But, I'll expose him. I'll proclaim his misdoings to the world; and, then, we shall see where he'll stand. Marry, come up! I'll show him what an injured wife can do. If all wives were of my mind and my spirit, husbands would soon be taught their own insignificance. But a time will come (and that before long,) when our sex will assert its superiority; and, when we have got the upper hand, let 'em try to subdue us if they can. But don't suppose, Madam, that anything I say has reference to you. I'm speaking of virtuous women—of WIVES, Madam. Mistresses neither deserve consideration nor commiseration.”

“I expect no commiseration,” returned Mrs. Sheppard, gently, “nor do I need any. But, rather than be the cause of any further misunderstanding between you and my benefactor, I will leave London and its neighbourhood for ever.”

“Pray do so, Madam,” retorted Mrs. Wood, “and take your son with you.”

“My son!” echoed the widow, trembling.

“Yes, your son, Madam. If you can do any good with him, it's more than we can. The house will be well rid of him, for a more idle, good-for-nothing reprobate never crossed its threshold.”

“Is this true, Sir?” cried Mrs. Sheppard, with an agonized look at Wood. “I know you'll not deceive me. Is Jack what Mrs. Wood represents him?”

“He's not exactly what I could desire him to be, Joan,” replied the carpenter, reluctantly, “But a ragged colt sometimes makes the best horse. He'll mend, I hope.”

“Never,” said Mrs. Wood,—“he'll never mend. He has taken more than one step towards the gallows already. Thieves and pickpockets are his constant companions.”

“Thieves!” exclaimed Mrs. Sheppard, horror-stricken.

“Jonathan Wild and Blueskin have got him into their hands,” continued Mrs. Wood.

“Impossible!” exclaimed the widow, wildly.

“If you doubt my word, woman,” replied the carpenter's wife, coldly, “ask Mr. Wood.”

“I know you'll contradict it, Sir,” said the widow, looking at Wood as if she dreaded to have her fears confirmed,—“I know you will.”

“I wish I could, Joan,” returned the carpenter, sadly.

Mrs. Sheppard let fall her basket.

“My son,” she murmured, wringing her hands piteously—, “my son the companion of thieves! My son in Jonathan Wild's power! It cannot be.”

“Why not?” rejoined Mrs. Wood, in a taunting tone. “Your son's father was a thief; and Jonathan Wild (unless I'm misinformed,) was his friend,—so it's not unnatural he should show some partiality towards Jack.”

“Jonathan Wild was my husband's bitterest enemy,” said Mrs. Sheppard. “He first seduced him from the paths of honesty, and then betrayed him to a shameful death, and he has sworn to do the same thing by my son. Oh, Heavens; that I should have ever indulged a hope of happiness while that terrible man lives!”

“Compose yourself, Joan,” said Wood; “all will yet be well.”

“Oh, no,—no,” replied Mrs. Sheppard, distractedly. “All cannot be well, if this is true. Tell me, Sir,” she added, with forced calmness, and grasping Wood's arm; “what has Jack done? Tell me in a word, that I may know the worst. I can bear anything but suspense.”

“You're agitating yourself unnecessarily, Joan,” returned Wood, in a soothing voice. “Jack has been keeping bad company. That's the only fault I know of.”

“Thank God for that!” ejaculated Mrs. Sheppard, fervently. “Then it is not too late to save him. Where is he, Sir? Can I see him?”

“No, that you can't,” answered Mrs. Wood; “he has gone out without leave, and has taken Thames Darrell with him. If I were Mr. Wood, when he does return, I'd send him about his business. I wouldn't keep an apprentice to set my authority at defiance.”

Mr. Wood's reply, if he intended any, was cut short by a loud knocking at the door.

“'Odd's-my-life!—what's that?” he cried, greatly alarmed.

“It's Jonathan Wild come back with a troop of constables at his heels, to search the house,” rejoined Mrs. Wood, in equal trepidation. “We shall all be murdered. Oh! that Mr. Kneebone were here to protect me!”

“If it is Jonathan,” rejoined Wood, “it is very well for Mr. Kneebone he's not here. He'd have enough to do to protect himself, without attending to you. I declare I'm almost afraid to go to the door. Something, I'm convinced, has happened to the boys.”

“Has Jonathan Wild been here to-day?” asked Mrs. Sheppard, anxiously.

“To be sure he has!” returned Mrs. Wood; “and Blueskin, too. They're only just gone, mercy on us! what a clatter,” she added, as the knocking was repeated more violently than before.

While the carpenter irresolutely quitted the room, with a strong presentiment of ill upon his mind, a light quick step was heard descending the stairs, and before he could call out to prevent it, a man was admitted into the passage.

“Is this Misther Wudd's, my pretty miss?” demanded the rough voice of the Irish watchman.

“It is”, seplied Winifred; “have you brought any tidings of Thames Darrell!”

“Troth have I!” replied Terence: “but, bless your angilic face, how did you contrive to guess that?”

“Is he well?—is he safe?—is he coming back,” cried the little girl, disregarding the question.

“He's in St. Giles's round-house,” answered Terence; “but tell Mr. Wudd I'm here, and have brought him a message from his unlawful son, and don't be detainin' me, my darlin', for there's not a minute to lose if the poor lad's to be recused from the clutches of that thief and thief-taker o' the wurld, Jonathan Wild.”

The carpenter, upon whom no part of this hurried dialogue had been lost, now made his appearance, and having obtained from Terence all the information which that personage could impart respecting the perilous situation of Thames, he declared himself ready to start to Saint Giles's at once, and ran back to the room for his hat and stick; expressing his firm determination, as he pocketed his constable's staff with which he thought it expedient to arm himself, of being direfully revenged upon the thief-taker: a determination in which he was strongly encouraged by his wife. Terence, meanwhile, who had followed him, did not remain silent, but recapitulated his story, for the benefit of Mrs. Sheppard. The poor widow was thrown into an agony of distress on learning that a robbery had been committed, in which her son (for she could not doubt that Jack was one of the boys,) was implicated; nor was her anxiety alleviated by Mrs. Wood, who maintained stoutly, that if Thames had been led to do wrong, it must be through the instrumentality of his worthless companion.

“And there you're right, you may dipind, marm,” observed Terence. “Master Thames Ditt—what's his blessed name?—has honesty written in his handsome phiz; but as to his companion, Jack Sheppard, I think you call him, he's a born and bred thief. Lord bless you marm! we sees plenty on 'em in our purfession. Them young prigs is all alike. I seed he was one,—and a sharp un, too,—at a glance.”

“Oh!” exclaimed the widow, covering her face with her hands.

“Take a drop of brandy before we start, watchman,” said Wood, pouring out a glass of spirit, and presenting it to Terence, who smacked his lips as he disposed of it. “Won't you be persuaded, Joan?” he added, making a similar offer to Mrs. Sheppard, which she gratefully declined. “If you mean to accompany us, you may need it.”

“You are very kind, Sir,” returned the widow, “but I require no support. Nothing stronger than water has passed my lips for years.”

“We may believe as much of that as we please, I suppose,” observed the carpenter's wife, with a sneer. “Mr. Wood,” she continued, in an authoritative tone, seeing her husband ready to depart, “one word before you set out. If Jack Sheppard or his mother ever enter this house again, I leave it—that's all. Now, do what you please. You know my fixed determination.”

Mr. Wood made no reply; but, hastily kissing his weeping daughter, and bidding her be of good cheer, hurried off. He was followed with equal celerity by Terence and the widow. Traversing what remained of Wych Street at a rapid pace, and speeding along Drury Lane, the trio soon found themselves in Kendrick Yard. When they came to the round-house, Terry's courage failed him. Such was the terror inspired by Wild's vindictive character, that few durst face him who had given him cause for displeasure. Aware that he should incur the thief-taker's bitterest animosity by what he had done, the watchman, whose wrath against Quilt Arnold had evaporated during the walk, thought it more prudent not to hazard a meeting with his master, till the storm had, in some measure, blown over. Accordingly, having given Wood such directions as he thought necessary for his guidance, and received a handsome gratuity in return for his services, he departed.

It was not without considerable demur and delay on the part of Sharples that the carpenter and his companion could gain admittance to the round-house. Reconnoitring them through a small grated loophole, he refused to open the door till they had explained their business. This, Wood, acting upon Terry's caution, was most unwilling to do; but, finding he had no alternative, he reluctantly made known his errand and the bolts were undrawn. Once in, the constable's manner appeared totally changed. He was now as civil as he had just been insolent. Apologizing for their detention, he answered the questions put to him respecting the boys, by positively denying that any such prisoners had been entrusted to his charge, but offered to conduct him to every cell in the building to prove the truth of his assertion. He then barred and double-locked the door, took out the key, (a precautionary measure which, with a grim smile, he said he never omitted,) thrust it into his vest, and motioning the couple to follow him, led the way to the inner room. As Wood obeyed, his foot slipped; and, casting his eyes upon the floor, he perceived it splashed in several places with blood. From the freshness of the stains, which grew more frequent as they approached the adjoining chamber, it was evident some violence had been recently perpetrated, and the carpenter's own blood froze within his veins as he thought, with a thrill of horror, that, perhaps on this very spot, not many minutes before his arrival, his adopted son might have been inhumanly butchered. Nor was this impression removed as he stole a glance at Mrs. Sheppard, and saw from her terrified look that she had made the same alarming discovery as himself. But it was now too late to turn back, and, nerving himself for the shock he expected to encounter, he ventured after his conductor. No sooner had they entered the room than Sharples, who waited to usher them in, hastily retreated, closed the door, and turning the key, laughed loudly at the success of his stratagem. Vexation at his folly in suffering himself to be thus entrapped kept Wood for a short time silent. When he could find words, he tried by the most urgent solicitations to prevail upon the constable to let him out. But threats and entreaties—even promises were ineffectual; and the unlucky captive, after exhausting his powers of persuasion, was compelled to give up the point.

The room in which he was detained—that lately occupied by the Mohocks, who, it appeared, had been allowed to depart,—was calculated to inspire additional apprehension and disgust. Strongly impregnated with the mingled odours of tobacco, ale, brandy, and other liquors, the atmosphere was almost stifling. The benches running round the room, though fastened to the walls by iron clamps, had been forcibly wrenched off; while the table, which was similarly secured to the boards, was upset, and its contents—bottles, jugs, glasses, and bowls were broken and scattered about in all directions. Everything proclaimed the mischievous propensities of the recent occupants of the chamber.

Here lay a heap of knockers of all sizes, from the huge lion's head to the small brass rapper: there, a collection of sign-boards, with the names and calling of the owners utterly obliterated. On this side stood the instruments with which the latter piece of pleasantry had been effected,—namely, a bucket filled with paint and a brush: on that was erected a trophy, consisting of a watchman's rattle, a laced hat, with the crown knocked out, and its place supplied by a lantern, a campaign wig saturated with punch, a torn steen-kirk and ruffles, some half-dozen staves, and a broken sword.

As the carpenter's gaze wandered over this scene of devastation, his attention was drawn by Mrs. Sheppard towards an appalling object in one corner. This was the body of a man, apparently lifeless, and stretched upon a mattress, with his head bound up in a linen cloth, through which the blood had oosed. Near the body, which, it will be surmised, was that of Abraham Mendez, two ruffianly personages were seated, quietly smoking, and bestowing no sort of attention upon the new-comers. Their conversation was conducted in the flash language, and, though unintelligible to Wood, was easily comprehended by this companion, who learnt, to her dismay, that the wounded man had received his hurt from her son, whose courage and dexterity formed the present subject of their discourse. From other obscure hints dropped by the speakers, Mrs. Sheppard ascertained that Thames Darrell had been carried off—where she could not make out—by Jonathan Wild and Quilt Arnold; and that Jack had been induced to accompany Blueskin to the Mint. This intelligence, which she instantly communicated to the carpenter, drove him almost frantic. He renewed his supplications to Sharples, but with no better success than heretofore; and the greater part of the night was passed by him and the poor widow, whose anxiety, if possible, exceeded his own, in the most miserable state imaginable.

At length, about three o'clock, as the first glimmer of dawn became visible through the barred casements of the round-house, the rattling of bolts and chains at the outer door told that some one was admitted. Whoever this might be, the visit seemed to have some reference to the carpenter, for, shortly afterwards, Sharples made his appearance, and informed the captives they were free. Without waiting to have the information repeated, Wood rushed forth, determined as soon as he could procure assistance, to proceed to Jonathan Wild's house in the Old Bailey; while Mrs. Sheppard, whose maternal fears drew her in another direction, hurried off to the Mint.

In an incredibly short space of time,—for her anxiety lent wings to her feet,—Mrs. Sheppard reached the debtor's garrison. From a scout stationed at the northern entrance, whom she addressed in the jargon of the place, with which long usage had formerly rendered her familiar, she ascertained that Blueskin, accompanied by a youth, whom she knew by the description must be her son, had arrived there about three hours before, and had proceeded to the Cross Shovels. This was enough for the poor widow. She felt she was now near her boy, and, nothing doubting her ability to rescue him from his perilous situation, she breathed a fervent prayer for his deliverance; and bending her steps towards the tavern in question, revolved within her mind as she walked along the best means of accomplishing her purpose. Aware of the cunning and desperate characters of the persons with whom she would have to deal,—aware, also, that she was in a quarter where no laws could be appealed to, nor assistance obtained, she felt the absolute necessity of caution. Accordingly, when she arrived at the Shovels, with which, as an old haunt in her bygone days of wretchedness she was well acquainted, instead of entering the principal apartment, which she saw at a glance was crowded with company of both sexes, she turned into a small room on the left of the bar, and, as an excuse for so doing, called for something to drink. The drawers at the moment were too busy to attend to her, and she would have seized the opportunity of examining, unperceived, the assemblage within, through a little curtained window that overlooked the adjoining chamber, if an impediment had not existed in the shape of Baptist Kettleby, whose portly person entirely obscured the view. The Master of the Mint, in the exercise of his two-fold office of governor and publican, was mounted upon a chair, and holding forth to his guests in a speech, to which Mrs. Sheppard was unwillingly compelled to listen.

“Gentlemen of the Mint,” said the orator, “when I was first called, some fifty years ago, to the important office I hold, there existed across the water three places of refuge for the oppressed and persecuted debtor.”

“We know it,” cried several voices.

“It happened, gentlemen,” pursued the Master, “on a particular occasion, about the time I've mentioned, that the Archduke of Alsatia, the Sovereign of the Savoy, and the Satrap of Salisbury Court, met by accident at the Cross Shovels. A jolly night we made of it, as you may suppose; for four such monarchs don't often come together. Well, while we were smoking our pipes, and quaffing our punch, Alsatia turns to me and says, 'Mint,' says he, 'you're well off here.'—'Pretty well,' says I; 'you're not badly off at the Friars, for that matter.'—'Oh! yes we are,' says he.—'How so?' says I.—'It's all up with us,' says he; 'they've taken away our charter.'—'They can't,' says I.—'They have,' says he.—'They can't, I tell you,' says I, in a bit of a passion; 'it's unconstitutional.'—'Unconstitutional or not,' says Salisbury Court and Savoy, speaking together, 'it's true. We shall become a prey to the Philistines, and must turn honest in self-defence.'—'No fear o' that,' thought I.—'I see how it'll be,' observed Alsatia, 'everybody'll pay his debts, and only think of such a state of things as that.'—'It's not to be thought of,' says I, thumping the table till every glass on it jingled; 'and I know a way as'll prevent it.'—'What is it, Mint?' asked all three.—'Why, hang every bailiff that sets a foot in your territories, and you're safe,' says I.—'We'll do it,' said they, filling their glasses, and looking as fierce as King George's grenadier guards; 'here's your health, Mint.' But, gentlemen, though they talked so largely, and looked so fiercely, they did not do it; they did not hang the bailiffs; and where are they?”

“Ay, where are they?” echoed the company with indignant derision.

“Gentlemen,” returned the Master, solemnly, “it is a question easily answered—they are NOWHERE! Had they hanged the bailiffs, the bailiffs would not have hanged them. We ourselves have been similarly circumstanced. Attacked by an infamous and unconstitutional statute, passed in the reign of the late usurper, William of Orange, (for I may remark that, if the right king had been upon the throne, that illegal enactment would never have received the royal assent—the Stuarts—Heaven preserve 'em!—always siding with the debtors); attacked in this outrageous manner, I repeat, it has been all but 'up' with US! But the vigorous resistance offered on that memorable occasion by the patriotic inhabitants of Bermuda to the aggressions of arbitrary power, secured and established their privileges on a firmer basis than heretofore; and, while their pusillanimous allies were crushed and annihilated, they became more prosperous than ever. Gentlemen, I am proud to say that I originated—that I directed those measures. I hope to see the day, when not Southwark alone, but London itself shall become one Mint,—when all men shall be debtors, and none creditors,—when imprisonment for debt shall be utterly abolished,—when highway-robbery shall be accounted a pleasant pastime, and forgery an accomplishment,—when Tyburn and its gibbets shall be overthrown,—capital punishments discontinued,—Newgate, Ludgate, the Gatehouse, and the Compters razed to the ground,—Bridewell and Clerkenwell destroyed,—the Fleet, the King's Bench, and the Marshalsea remembered only by name! But, in the mean time, as that day may possibly be farther off than I anticipate, we are bound to make the most of the present. Take care of yourselves, gentlemen, and your governor will take care of you. Before I sit down, I have a toast to propose, which I am sure will be received, as it deserves to be, with enthusiasm. It is the health of a stranger,—of Mr. John Sheppard. His father was one of my old customers, and I am happy to find his son treading in his steps. He couldn't be in better hands than those in which he has placed himself. Gentlemen,—Mr. Sheppard's good health, and success to him!”

Baptist's toast was received with loud applause, and, as he sat down amid the cheers of the company, and a universal clatter of mugs and glasses, the widow's view was no longer obstructed. Her eye wandered quickly over that riotous and disorderly assemblage, until it settled upon one group more riotous and disorderly than the rest, of which her son formed the principal figure. The agonized mother could scarcely repress a scream at the spectacle that met her gaze. There sat Jack, evidently in the last stage of intoxication, with his collar opened, his dress disarranged, a pipe in his mouth, a bowl of punch and a half-emptied rummer before him,—there he sat, receiving and returning, or rather attempting to return,—for he was almost past consciousness,—the blandishments of a couple of females, one of whom had passed her arm round his neck, while the other leaned over the back of his chair and appeared from her gestures to be whispering soft nonsense into his ear.

Both these ladies possessed considerable personal attractions. The younger of the two, who was seated next to Jack, and seemed to monopolize his attention, could not be more than seventeen, though her person had all the maturity of twenty. She had delicate oval features, light, laughing blue eyes, a pretty nez retroussé, (why have we not the term, since we have the best specimens of the feature?) teeth of pearly whiteness, and a brilliant complexion, set off by rich auburn hair, a very white neck and shoulders,—the latter, perhaps, a trifle too much exposed. The name of this damsel was Edgeworth Bess; and, as her fascinations will not, perhaps, be found to be without some influence upon the future fortunes of her boyish admirer, we have thought it worth while to be thus particular in describing them. The other bona roba, known amongst her companions as Mistress Poll Maggot, was a beauty on a much larger scale,—in fact, a perfect Amazon. Nevertheless though nearly six feet high, and correspondingly proportioned, she was a model of symmetry, and boasted, with the frame of a Thalestris or a Trulla, the regular lineaments of the Medicean Venus. A man's laced hat,—whether adopted from the caprice of the moment, or habitually worn, we are unable to state,—cocked knowingly on her head, harmonized with her masculine appearance. Mrs. Maggot, as well as her companion Edgeworth Bess, was showily dressed; nor did either of them disdain the aid supposed to be lent to a fair skin by the contents of the patchbox. On an empty cask, which served him for a chair, and opposite Jack Sheppard, whose rapid progress in depravity afforded him the highest satisfaction, sat Blueskin, encouraging the two women in their odious task, and plying his victim with the glass as often as he deemed it expedient to do so. By this time, he had apparently accomplished all he desired; for moving the bottle out of Jack's reach, he appropriated it entirely to his own use, leaving the devoted lad to the care of the females. Some few of the individuals seated at the other tables seemed to take an interest in the proceedings of Blueskin and his party, just as a bystander watches any other game; but, generally speaking, the company were too much occupied with their own concerns to pay attention to anything else. The assemblage was for the most part, if not altogether, composed of persons to whom vice in all its aspects was too familiar to present much of novelty, in whatever form it was exhibited. Nor was Jack by any means the only stripling in the room. Not far from him was a knot of lads drinking, swearing, and playing at dice as eagerly and as skilfully as any of the older hands. Near to these hopeful youths sat a fence, or receiver, bargaining with a clouter, or pickpocket, for a suit,—or, to speak in more intelligible language, a watch and seals, two cloaks, commonly called watch-cases, and a wedge-lobb, otherwise known as a silver snuff-box. Next to the receiver was a gang of housebreakers, laughing over their exploits, and planning fresh depredations; and next to the housebreakers came two gallant-looking gentlemen in long periwigs and riding-dresses, and equipped in all other respects for the road, with a roast fowl and a bottle of wine before them. Amid this varied throng,—varied in appearance, but alike in character,—one object alone, we have said, rivetted Mrs. Sheppard's attention; and no sooner did she in some degree recover from the shock occasioned by the sight of her son's debased condition, than, regardless of any other consideration except his instant removal from the contaminating society by which he was surrounded, and utterly forgetting the more cautious plan she meant to have adopted, she rushed into the room, and summoned him to follow her.

“Halloa!” cried Jack, looking round, and trying to fix his inebriate gaze upon the speaker,—“who's that?”

“Your mother,” replied Mrs. Sheppard. “Come home directly, Sir.”

“Mother be——!” returned Jack. “Who is it, Bess?”

“How should I know?” replied Edgeworth Bess. “But if it is your mother, send her about her business.”

“That I will,” replied Jack, “in the twinkling of a bedpost.”

“Glad to see you once more in the Mint, Mrs. Sheppard,” roared Blueskin, who anticipated some fun. “Come and sit down by me.”

“Take a glass of gin, Ma'am,” cried Poll Maggot, holding up a bottle of spirit; “it used to be your favourite liquor, I've heard.”

“Jack, my love,” cried Mrs. Sheppard, disregarding the taunt, “come away.”

“Not I,” replied Jack; “I'm too comfortable where I am. Be off!”

“Jack!” exclaimed his unhappy parent.

“Mr. Sheppard, if you please, Ma'am,” interrupted the lad; “I allow nobody to call me Jack. Do I, Bess, eh?”

“Nobody whatever, love,” replied Edgeworth Bess; “nobody but me, dear.”

“And me,” insinuated Mrs. Maggot. “My little fancy man's quite as fond of me as of you, Bess. Ain't you, Jacky darling?”

“Not quite, Poll,” returned Mr. Sheppard; “but I love you next to her, and both of you better than Her,” pointing with the pipe to his mother.

“Oh, Heavens!” cried Mrs. Sheppard.

“Bravo!” shouted Blueskin. “Tom Sheppard never said a better thing than that—ho! ho!”

“Jack,” cried his mother, wringing her hands in distraction, “you'll break my heart!”

“Poh! poh!” returned her son; “women don't so easily break their hearts. Do they, Bess?”

“Certainly not,” replied the young lady appealed to, “especially about their sons.”

“Wretch!” cried Mrs. Sheppard, bitterly.

“I say,” retorted Edgeworth Bess, with a very unfeminine imprecation, “I shan't stand any more of that nonsense. What do you mean by calling me wretch, Madam!” she added marching up to Mrs. Sheppard, and regarding her with an insolent and threatening glance.

“Yes—what do you mean, Ma'am?” added Jack, staggering after her.

“Come with me, my love, come—come,” cried his mother, seizing his hand, and endeavouring to force him away.

“He shan't go,” cried Edgeworth Bess, holding him by the other hand. “Here, Poll, help me!”

Thus exhorted, Mrs. Maggot lent her powerful aid, and, between the two, Jack was speedily relieved from all fears of being carried off against his will. Not content with this exhibition of her prowess, the Amazon lifted him up as easily as if he had been an infant, and placed him upon her shoulders, to the infinite delight of the company, and the increased distress of his mother.

“Now, let's see who'll dare to take him down,” she cried.

“Nobody shall,” cried Mr. Sheppard from his elevated position. “I'm my own master now, and I'll do as I please. I'll turn cracksman, like my father—rob old Wood—he has chests full of money, and I know where they're kept—I'll rob him, and give the swag to you, Poll—I'll—”

Jack would have said more; but, losing his balance, he fell to the ground, and, when taken up, he was perfectly insensible. In this state, he was laid upon a bench, to sleep off his drunken fit, while his wretched mother, in spite of her passionate supplications and resistance, was, by Blueskin's command, forcibly ejected from the house, and driven out of the Mint.

During the whole of the next day and night, the poor widow hovered like a ghost about the precincts of the debtors' garrison,—for admission (by the Master's express orders,) was denied her. She could learn nothing of her son, and only obtained one solitary piece of information, which added to, rather than alleviated her misery,—namely, that Jonathan Wild had paid a secret visit to the Cross Shovels. At one time, she determined to go to Wych Street, and ask Mr. Wood's advice and assistance, but the thought of the reception she was likely to meet with from his wife deterred her from executing this resolution. Many other expedients occurred to her; but after making several ineffectual attempts to get into the Mint unobserved, they were all abandoned.

At length, about an hour before dawn on the second day—Sunday—having spent the early part of the night in watching at the gates of the robbers' sanctuary, and being almost exhausted from want of rest, she set out homewards. It was a long walk she had to undertake, even if she had endured no previous fatigue, but feeble as she was, it was almost more than she could accomplish. Daybreak found her winding her painful way along the Harrow Road; and, in order to shorten the distance as much as possible, she took the nearest cut, and struck into the meadows on the right. Crossing several fields, newly mown, or filled with lines of tedded hay, she arrived, not without great exertion, at the summit of a hill. Here her strength completely failed her, and she was compelled to seek some repose. Making her couch upon a heap of hay, she sank at once into a deep and refreshing slumber.

When she awoke, the sun was high in Heaven. It was a bright and beautiful day: so bright, so beautiful, that even her sad heart was cheered by it. The air, perfumed with the delicious fragrance of the new-mown grass, was vocal with the melodies of the birds; the thick foliage of the trees was glistening in the sunshine; all nature seemed happy and rejoicing; but, above all, the serene Sabbath stillness reigning around communicated a calm to her wounded spirit.

What a contrast did the lovely scene she now gazed upon present to the squalid neighbourhood she had recently quitted! On all sides, expanded prospects of country the most exquisite and most varied. Immediately beneath her lay Willesden,—the most charming and secluded village in the neighbourhood of the metropolis—with its scattered farm-houses, its noble granges, and its old grey church-tower just peeping above a grove of rook-haunted trees.

Towards this spot Mrs. Sheppard now directed her steps. She speedily reached her own abode,—a little cottage, standing in the outskirts of the village. The first circumstance that struck her on her arrival seemed ominous. Her clock had stopped—stopped at the very hour on which she had quitted the Mint! She had not the heart to wind it up again.

After partaking of some little refreshment, and changing her attire, Mrs. Sheppard prepared for church. By this time, she had so far succeeded in calming herself, that she answered the greetings of the neighbours whom she encountered on her way to the sacred edifice—if sorrowfully, still composedly.

Every old country church is beautiful, but Willesden is the most beautiful country church we know; and in Mrs. Sheppard's time it was even more beautiful than at present, when the hand of improvement has proceeded a little too rashly with alterations and repairs. With one or two exceptions, there were no pews; and, as the intercourse with London was then but slight, the seats were occupied almost exclusively by the villagers. In one of these seats, at the end of the aisle farthest removed from the chancel, the widow took her place, and addressed herself fervently to her devotions.

The service had not proceeded far, when she was greatly disturbed by the entrance of a person who placed himself opposite her, and sought to attract her attention by a number of little arts, surveying her, as he did so, with a very impudent and offensive stare. With this person—who was no other than Mr. Kneebone—she was too well acquainted; having, more than once, been obliged to repel his advances; and, though his impertinence would have given her little concern at another season, it now added considerably to her distraction. But a far greater affliction was in store for her.

Just as the clergyman approached the altar, she perceived a boy steal quickly into the church, and ensconce himself behind the woollen-draper, who, in order to carry on his amatory pursuits with greater convenience, and at the same time display his figure (of which he was not a little vain) to the utmost advantage, preferred a standing to a sitting posture. Of this boy she had only caught a glimpse;—but that glimpse was sufficient to satisfy her it was her son,—and, if she could have questioned her own instinctive love, she could not question her antipathy, when she beheld, partly concealed by a pillar immediately in the rear of the woollen-draper, the dark figure and truculent features of Jonathan Wild. As she looked in this direction, the thief-taker raised his eyes—those gray, blood-thirsty eyes!—their glare froze the life-blood in her veins.

As she averted her gaze, a terrible idea crossed her. Why was he there? why did the tempter dare to invade that sacred spot! She could not answer her own questions, but vague fearful suspicions passed through her mind. Meanwhile, the service proceeded; and the awful command, “Thou shalt not steal!” was solemnly uttered by the preacher, when Mrs. Sheppard, who had again looked round towards her son, beheld a hand glance along the side of the woollen-draper. She could not see what occurred, though she guessed it; but she saw Jonathan's devilish triumphing glance, and read in it,—“Your son has committed a robbery—here—in these holy walls—he is mine—mine for ever!”

She uttered a loud scream, and fainted.

Just as St. Sepulchre's church struck one, on the eventful night of the 10th of June, (to which it will not be necessary to recur,) a horseman, mounted on a powerful charger, and followed at a respectful distance by an attendant, galloped into the open space fronting Newgate, and directed his course towards a house in the Old Bailey. Before he could draw in the rein, his steed—startled apparently by some object undistinguishable by the rider,—swerved with such suddenness as to unseat him, and precipitate him on the ground. The next moment, however, he was picked up, and set upon his feet by a person who, having witnessed the accident, flew across the road to his assistance.

“You're not hurt I hope, Sir Rowland?” inquired this individual.

“Not materially, Mr. Wild,” replied the other, “a little shaken, that's all. Curses light on the horse!” he added, seizing the bridle of his steed, who continued snorting and shivering, as if still under the influence of some unaccountable alarm; “what can ail him?”

“I know what ails him, your honour,” rejoined the groom, riding up as he spoke; “he's seen somethin' not o' this world.”

“Most likely,” observed Jonathan, with a slight sneer; “the ghost of some highwayman who has just breathed his last in Newgate, no doubt.”

“May be,” returned the man gravely.

“Take him home, Saunders,” said Sir Rowland, resigning his faulty steed to the attendant's care, “I shall not require you further. Strange!” he added, as the groom departed; “Bay Stuart has carried me through a hundred dangers, but never played me such a trick before.”

“And never should again, were he mine,” rejoined Jonathan. “If the best nag ever foaled were to throw me in this unlucky spot, I'd blow his brains out.”

“What do you mean, Sir?” asked Trenchard.

“A fall against Newgate is accounted a sign of death by the halter,” replied Wild, with ill-disguised malignity.

“Tush!” exclaimed Sir Rowland, angrily.

“From that door,” continued the thief-taker, pointing to the gloomy portal of the prison opposite which they were standing, “the condemned are taken to Tyburn. It's a bad omen to be thrown near that door.”

“I didn't suspect you of so much superstition, Mr. Wild,” observed the knight, contemptuously.

“Facts convince the most incredulous,” answered Jonathan, drily. “I've known several cases where the ignominious doom I've mentioned has been foretold by such an accident as has just befallen you. There was Major Price—you must recollect him, Sir Rowland,—he stumbled as he was getting out of his chair at that very gate. Well, he was executed for murder. Then there was Tom Jarrot, the hackney-coachman, who was pitched off the box against yonder curbstone, and broke his leg. It was a pity he didn't break his neck, for he was hanged within the year. Another instance was that of Toby Tanner—”

“No more of this,” interrupted Trenchard; “where is the boy?”

“Not far hence,” replied Wild. “After all our pains we were near losing him, Sir Rowland.”

“How so?” asked the other, distrustfully.

“You shall hear,” returned Jonathan. “With the help of his comrade, Jack Sheppard, the young rascal made a bold push to get out of the round-house, where my janizaries had lodged him, and would have succeeded too, if, by good luck,—for the devil never deserts so useful an agent as I am, Sir Rowland,—I hadn't arrived in time to prevent him. As it was, my oldest and trustiest setter, Abraham Mendez, received a blow on the head from one of the lads that will deprive me of his services for a week to come,—if, indeed it does not disable him altogether. However, if I've lost one servant, I've gained another, that's one comfort. Jack Sheppard is now wholly in my hands.”

“What is this to me, Sir?” said Trenchard, cutting him short.

“Nothing whatever,” rejoined the thief-taker, coldly. “But it is much to me. Jack Sheppard is to me what Thames Darrell is to you—an object of hatred. I owed his father a grudge: that I settled long ago. I owe his mother one, and will repay the debt, with interest, to her son. I could make away with him at once, as you are about to make away with your nephew, Sir Rowland,—but that wouldn't serve my turn. To be complete, my vengeance must be tardy. Certain of my prey, I can afford to wait for it. Besides, revenge is sweetened by delay; and I indulge too freely in the passion to rob it of any of its zest. I've watched this lad—this Sheppard—from infancy; and, though I have apparently concerned myself little about him, I have never lost sight of my purpose. I have suffered him to be brought up decently—honestly; because I would make his fall the greater, and deepen the wound I meant to inflict upon his mother. From this night I shall pursue a different course; from this night his ruin may be dated. He is in the care of those who will not leave the task assigned to them—the utter perversion of his principles—half-finished. And when I have steeped him to the lips in vice and depravity; when I have led him to the commission of every crime; when there is neither retreat nor advance for him; when he has plundered his benefactor, and broken the heart of his mother—then—but not till then, I will consign him to the fate to which I consigned his father. This I have sworn to do—this I will do.”

“Not unless your skull's bullet-proof,” cried a voice at his elbow; and, as the words were uttered, a pistol was snapped at his head, which,—fortunately or unfortunately, as the reader pleases,—only burnt the priming. The blaze, however, was sufficient to reveal to the thief-taker the features of his intended assassin. They were those of the Irish watchman.

“Ah! Terry O'Flaherty!” vociferated Jonathan, in a tone that betrayed hot the slightest discomposure. “Ah! Terry O'Flaherty!” he cried, shouting after the Irishman, who took to his heels as soon as he found his murderous attempt unsuccessful; “you may run, but you'll not get out of my reach. I'll put a brace of dogs on your track, who'll soon hunt you down. You shall swing for this after next sessions, or my name's not Jonathan Wild. I told you, Sir Rowland,” he added, turning to the knight, and chuckling, “the devil never deserts me.”

“Conduct me to your dwelling, Sir, without further delay,” said Trenchard, sternly,—“to the boy.”

“The boy's not at my house,” replied Wild.

“Where is he, then?” demanded the other, hastily.

“At a place we call the Dark House at Queenhithe,” answered Jonathan, “a sort of under-ground tavern or night-cellar, close to the river-side, and frequented by the crew of the Dutch skipper, to whose care he's to be committed. You need have no apprehensions about him, Sir Rowland. He's safe enough now. I left him in charge of Quilt Arnold and Rykhart Van Galgebrok—the skipper I spoke of—with strict orders to shoot him if he made any further attempt at escape; and they're not lads—the latter especially—to be trifled with. I deemed it more prudent to send him to the Dark House than to bring him here, in case of any search after him by his adoptive father—the carpenter Wood. If you choose, you can see him put on board the Zeeslang yourself, Sir Rowland. But, perhaps, you'll first accompany me to my dwelling for a moment, that we may arrange our accounts before we start. I've a few necessary directions to leave with my people, to put 'em on their guard against the chance of a surprise. Suffer me to precede you. This way, Sir Rowland.”

The thief-taker's residence was a large dismal-looking, habitation, separated from the street by a flagged court-yard, and defended from general approach by an iron railing. Even in the daylight, it had a sombre and suspicious air, and seemed to slink back from the adjoining houses, as if afraid of their society. In the obscurity in which it was now seen, it looked like a prison, and, indeed, it was Jonathan's fancy to make it resemble one as much as possible. The windows were grated, the doors barred; each room had the name as well as the appearance of a cell; and the very porter who stood at the gate, habited like a jailer, with his huge bunch of keys at his girdle, his forbidding countenance and surly demeanour seemed to be borrowed from Newgate. The clanking of chains, the grating of locks, and the rumbling of bolts must have been music in Jonathan's ears, so much pains did he take to subject himself to such sounds. The scanty furniture of the rooms corresponded with their dungeon-like aspect. The walls were bare, and painted in stone-colour; the floors, devoid of carpet; the beds, of hangings; the windows, of blinds; and, excepting in the thief-taker's own audience-chamber, there was not a chair or a table about the premises; the place of these conveniences being elsewhere supplied by benches, and deal-boards laid across joint-stools. Great stone staircases leading no one knew whither, and long gloomy passages, impressed the occasional visitor with the idea that he was traversing a building of vast extent; and, though this was not the case in reality, the deception was so cleverly contrived that it seldom failed of producing the intended effect. Scarcely any one entered Mr. Wild's dwelling without apprehension, or quitted it without satisfaction. More strange stories were told of it than of any other house in London. The garrets were said to be tenanted by coiners, and artists employed in altering watches and jewelry; the cellars to be used as a magazine for stolen goods. By some it was affirmed that a subterranean communication existed between the thief-taker's abode and Newgate, by means of which he was enabled to maintain a secret correspondence with the imprisoned felons: by others, that an under-ground passage led to extensive vaults, where such malefactors as he chose to screen from justice might lie concealed till the danger was blown over. Nothing, in short, was too extravagant to be related of it; and Jonathan, who delighted in investing himself and his residence with mystery, encouraged, and perhaps originated, these marvellous tales. However this may be, such was the ill report of the place that few passed along the Old Bailey without bestowing a glance of fearful curiosity at its dingy walls, and wondering what was going on inside them; while fewer still, of those who paused at the door, read, without some internal trepidation, the formidable name—inscribed in large letters on its bright brass-plate—of JONATHAN WILD.

Arrived at his habitation, Jonathan knocked in a peculiar manner at the door, which was instantly opened by the grim-visaged porter just alluded to. No sooner had Trenchard crossed the threshold than a fierce barking was heard at the farther extremity of the passage, and, the next moment, a couple of mastiffs of the largest size rushed furiously towards him. The knight stood upon his defence; but he would unquestionably have been torn in pieces by the savage hounds, if a shower of oaths, seconded by a vigorous application of kicks and blows from their master, had not driven them growling off. Apologizing to Sir Rowland for this unpleasant reception, and swearing lustily at his servant for occasioning it by leaving the dogs at liberty, Jonathan ordered the man to light them to the audience-room. The command was sullenly obeyed, for the fellow did not appear to relish the rating. Ascending the stairs, and conducting them along a sombre gallery, in which Trenchard noticed that every door was painted black, and numbered, he stopped at the entrance of a chamber; and, selecting a key from the bunch at his girdle, unlocked it. Following his guide, Sir Rowland found himself in a large and lofty apartment, the extent of which he could not entirely discern until lights were set upon the table. He then looked around him with some curiosity; and, as the thief-taker was occupied in giving directions to his attendant in an undertone, ample leisure was allowed him for investigation. At the first glance, he imagined he must have stumbled upon a museum of rarities, there were so many glass-cases, so many open cabinets, ranged against the walls; but the next convinced him that if Jonathan was a virtuoso, his tastes did not run in the ordinary channels. Trenchard was tempted to examine the contents of some of these cases, but a closer inspection made him recoil from them in disgust. In the one he approached was gathered together a vast assortment of weapons, each of which, as appeared from the ticket attached to it, had been used as an instrument of destruction. On this side was a razor with which a son had murdered his father; the blade notched, the haft crusted with blood: on that, a bar of iron, bent, and partly broken, with which a husband had beaten out his wife's brains. As it is not, however, our intention to furnish a complete catalogue of these curiosities, we shall merely mention that in front of them lay a large and sharp knife, once the property of the public executioner, and used by him to dissever the limbs of those condemned to death for high-treason; together with an immense two-pronged flesh-fork, likewise employed by the same terrible functionary to plunge the quarters of his victims in the caldrons of boiling tar and oil. Every gibbet at Tyburn and Hounslow appeared to have been plundered of its charnel spoil to enrich the adjoining cabinet, so well was it stored with skulls and bones, all purporting to be the relics of highwaymen famous in their day. Halters, each of which had fulfilled its destiny, formed the attraction of the next compartment; while a fourth was occupied by an array of implements of housebreaking almost innumerable, and utterly indescribable. All these interesting objects were carefully arranged, classed, and, as we have said, labelled by the thief-taker. From this singular collection Trenchard turned to regard its possessor, who was standing at a little distance from him, still engaged in earnest discourse with his attendant, and, as he contemplated his ruthless countenance, on which duplicity and malignity had set their strongest seals, he could not help calling to mind all he had heard of Jonathan's perfidiousness to his employers, and deeply regretting that he had placed himself in the power of so unscrupulous a miscreant.

Jonathan Wild, at this time, was on the high-road to the greatness which he subsequently, and not long afterwards, obtained. He was fast rising to an eminence that no one of his nefarious profession ever reached before him, nor, it is to be hoped, will ever reach again. He was the Napoleon of knavery, and established an uncontrolled empire over all the practitioners of crime. This was no light conquest; nor was it a government easily maintained. Resolution, severity, subtlety, were required for it; and these were qualities which Jonathan possessed in an extraordinary degree. The danger or difficulty of an exploit never appalled him. What his head conceived his hand executed. Professing to stand between the robber and the robbed, he himself plundered both. He it was who formed the grand design of a robber corporation, of which he should be the sole head and director, with the right of delivering those who concealed their booty, or refused to share it with him, to the gallows. He divided London into districts; appointed a gang to each district; and a leader to each gang, whom he held responsible to himself. The country was partitioned in a similar manner. Those whom he retained about his person, or placed in offices of trust, were for the most part convicted felons, who, having returned from transportation before their term had expired, constituted, in his opinion, the safest agents, inasmuch as they could neither be legal evidences against him, nor withhold any portion of the spoil of which he chose to deprive them. But the crowning glory of Jonathan, that which raised him above all his predecessors in iniquity, and clothed this name with undying notoriety—was to come. When in the plenitude of his power, he commenced a terrible trade, till then unknown—namely, a traffic in human blood. This he carried on by procuring witnesses to swear away the lives of those persons who had incurred his displeasure, or whom it might be necessary to remove.

No wonder that Trenchard, as he gazed at this fearful being, should have some misgivings cross him.

Apparently, Jonathan perceived he was an object of scrutiny; for, hastily dismissing his attendant, he walked towards the knight.

“So, you're admiring my cabinet, Sir Rowland,” he remarked, with a sinister smile; “it is generally admired; and, sometimes by parties who afterwards contribute to the collection themselves,—ha! ha! This skull,” he added, pointing to a fragment of mortality in the case beside them, “once belonged to Tom Sheppard, the father of the lad I spoke of just now. In the next box hangs the rope by which he suffered. When I've placed another skull and another halter beside them, I shall be contented.”

“To business, Sir!” said the knight, with a look of abhorrence.

“Ay, to business,” returned Jonathan, grinning, “the sooner the better.”

“Here is the sum you bargained for,” rejoined Trenchard, flinging a pocket-book on the table; “count it.”

Jonathan's eyes glistened as he told over the notes.

“You've given me more than the amount, Sir Rowland,” he said, after he had twice counted them, “or I've missed my reckoning. There's a hundred pounds too much.”

“Keep it,” said Trenchard, haughtily.

“I'll place it to your account, Sir Rowland,” answered the thief-taker, smiling significantly. “And now, shall we proceed to Queenhithe?”

“Stay!” cried the other, taking a chair, “a word with you, Mr. Wild.”

“As many as you please, Sir Rowland,” replied Jonathan, resuming his seat. “I'm quite at your disposal.”

“I have a question to propose to you,” said Trenchard, “relating to—” and he hesitated.

“Relating to the father of the boy—Thames Darrell,” supplied Jonathan. “I guessed what was coming. You desire to know who he was, Sir Rowland. Well, you shall know.”

“Without further fee?” inquired the knight.

“Not exactly,” answered Jonathan, drily. “A secret is too valuable a commodity to be thrown away. But I said I wouldn't drive a hard bargain with you, and I won't. We are alone, Sir Rowland,” he added, snuffing the candles, glancing cautiously around, and lowering his tone, “and what you confide to me shall never transpire,—at least to your disadvantage.”

“I am at a loss to understand you Sir,”, said Trenchard.

“I'll make myself intelligible before I've done,” rejoined Wild. “I need not remind you, Sir Rowland, that I am aware you are deeply implicated in the Jacobite plot which is now known to be hatching.”

“Ha!” ejaculated the other.

“Of course, therefore,” pursued Jonathan, “you are acquainted with all the leaders of the proposed insurrection,—nay, must be in correspondence with them.”

“What right have you to suppose this, Sir?” demanded Trenchard, sternly.

“Have a moment's patience, Sir Rowland,” returned Wild; “and you shall hear. If you will furnish me with a list of these rebels, and with proofs of their treason, I will not only insure your safety, but will acquaint you with the real name and rank of your sister Aliva's husband, as well as with some particulars which will never otherwise reach your ears, concerning your lost sister, Constance.”

“My sister Constance!” echoed the knight; “what of her?”

“You agree to my proposal, then?” said Jonathan.

“Do you take me for as great a villain as yourself, Sir?” said the knight, rising.

“I took you for one who wouldn't hesitate to avail himself of any advantage chance might throw in his way,” returned the thief-taker, coldly. “I find I was in error. No matter. A time may come,—and that ere long,—when you will be glad to purchase my secrets, and your own safety, at a dearer price than the heads of your companions.”

“Are you ready?” said Trenchard, striding towards the door.

“I am,” replied Jonathan, following him, “and so,” he added in an undertone, “are your captors.”

A moment afterwards, they quitted the house.

After a few minutes' rapid walking, during which neither party uttered a word, Jonathan Wild and his companion had passed Saint Paul's, dived down a thoroughfare on the right, and reached Thames Street.

At the period of this history, the main streets of the metropolis were but imperfectly lighted, while the less-frequented avenues were left in total obscurity; but, even at the present time, the maze of courts and alleys into which Wild now plunged, would have perplexed any one, not familiar with their intricacies, to thread them on a dark night. Jonathan, however, was well acquainted with the road. Indeed, it was his boast that he could find his way through any part of London blindfolded; and by this time, it would seem, he had nearly arrived at his destination; for, grasping his companion's arm, he led him along a narrow entry which did not appear to have an outlet, and came to a halt. Cautioning the knight, if he valued his neck, to tread carefully, Jonathan then descended a steep flight of steps; and, having reached the bottom in safety, he pushed open a door, that swung back on its hinges as soon as it had admitted him; and, followed by Trenchard, entered the night-cellar.

The vault, in which Sir Rowland found himself, resembled in some measure the cabin of a ship. It was long and narrow, with a ceiling supported by huge uncovered rafters, and so low as scarcely to allow a tall man like himself to stand erect beneath it. Notwithstanding the heat of the season,—which was not, however, found particularly inconvenient in this subterranean region,—a large heaped-up fire blazed ruddily in one corner, and lighted up a circle of as villanous countenances as ever flame shone upon.

The guests congregated within the night-cellar were, in fact, little better than thieves; but thieves who confined their depredations almost exclusively to the vessels lying in the pool and docks of the river. They had as many designations as grades. There were game watermen and game lightermen, heavy horsemen and light horsemen, scuffle-hunters, and long-apron men, lumpers, journeymen coopers, mud-larks, badgers, and ratcatchers—a race of dangerous vermin recently, in a great measure, extirpated by the vigilance of the Thames Police, but at this period flourishing in vast numbers. Besides these plunderers, there were others with whom the disposal of their pillage necessarily brought them into contact, and who seldom failed to attend them during their hours of relaxation and festivity;—to wit, dealers in junk, old rags, and marine stores, purchasers of prize-money, crimps, and Jew receivers. The latter formed by far the most knavish-looking and unprepossessing portion of the assemblage. One or two of the tables were occupied by groups of fat frowzy women in flat caps, with rings on their thumbs, and baskets by their sides; and no one who had listened for a single moment to their coarse language and violent abuse of each other, would require to be told they were fish-wives from Billingsgate.

The present divinity of the cellar was a comely middle-aged dame, almost as stout, and quite as shrill-voiced, as the Billingsgate fish-wives above-mentioned, Mrs. Spurling, for so was she named, had a warm nut-brown complexion, almost as dark as a Creole; and a moustache on her upper lip, that would have done no discredit to the oldest dragoon in the King's service. This lady was singularly lucky in her matrimonial connections. She had been married four times: three of her husbands died of hempen fevers; and the fourth, having been twice condemned, was saved from the noose by Jonathan Wild, who not only managed to bring him off, but to obtain for him the situation of under-turnkey in Newgate.

On the appearance of the thief-taker, Mrs. Spurling was standing near the fire superintending some culinary preparation; but she no sooner perceived him, than hastily quitting her occupation, she elbowed a way for him and the knight through the crowd, and ushered them, with much ceremony, into an inner room, where they found the objects of their search, Quilt Arnold and Rykhart Van Galgebrok, seated at a small table, quietly smoking. This service rendered, without waiting for any farther order, she withdrew.

Both the janizary and the skipper arose as the others entered the room.

“This is the gentleman,” observed Jonathan, introducing Trenchard to the Hollander, “who is about to intrust his young relation to your care.”

“De gentleman may rely on my showing his relation all de attention in my power,” replied Van Galgebrok, bowing profoundly to the knight; “but if any unforseen accident—such as a slip overboard—should befal de jonker on de voyage, he mushn't lay de fault entirely on my shoulders—haw! haw!”

“Where is he?” asked Sir Rowland, glancing uneasily around. “I do not see him.”

“De jonker. He's here,” returned the skipper, pointing significantly downwards. “Bring him out, Quilt.”

So saying, he pushed aside the table, and the janizary stooping down, undrew a bolt and opened a trap-door.

“Come out!” roared Quilt, looking into the aperture. “You're wanted.”

But as no answer was returned, he trust his arm up to the shoulder into the hole, and with some little difficulty and exertion of strength, drew forth Thames Darrell.

The poor boy, whose hands were pinioned behind him, looked very pale, but neither trembled, nor exhibited any other symptom of alarm.

“Why didn't you come out when I called you, you young dog?” cried Quilt in a savage tone.

“Because I knew what you wanted me for!” answered Thames firmly.

“Oh! you did, did you?” said the janizary. “And what do you suppose we mean to do with you, eh?”

“You mean to kill me,” replied Thames, “by my cruel uncle's command. Ah! there he stands!” he exclaimed as his eye fell for the first time upon Sir Rowland. “Where is my mother?” he added, regarding the knight with a searching glance.

“Your mother is dead,” interposed Wild, scowling.

“Dead!” echoed the boy. “Oh no—no! You say this to terrify me—to try me. But I will not believe you. Inhuman as he is, he would not kill her. Tell me, Sir,” he added, advancing towards the knight, “tell me has this man spoken falsely?—Tell me my mother is alive, and do what you please with me.”

“Tell him so, and have done with him, Sir Rowland,” observed Jonathan coldly.

“Tell me the truth, I implore you,” cried Thames. “Is she alive?”

“She is not,” replied Trenchard, overcome by conflicting emotions, and unable to endure the boy's agonized look.

“Are you answered?” said Jonathan, with a grin worthy of a demon.

“My mother!—my poor mother!” ejaculated Thames, falling on his knees, and bursting into tears. “Shall I never see that sweet face again,—never feel the pressure of those kind hands more—nor listen to that gentle voice! Ah! yes, we shall meet again in Heaven, where I shall speedily join you. Now then,” he added more calmly, “I am ready to die. The only mercy you can show me is to kill me.”

“Then we won't even show you that mercy,” retorted the thief-taker brutally. “So get up, and leave off whimpering. Your time isn't come yet.”

“Mr. Wild,” said Trenchard, “I shall proceed no further in this business. Set the boy free.”

“If I disobey you, Sir Rowland,” replied the thief-taker, “you'll thank me for it hereafter. Gag him,” he added, pushing Thames rudely toward Quilt Arnold, “and convey him to the boat.”

“A word,” cried the boy, as the janizary was preparing to obey his master's orders. “What has become of Jack Sheppard?”

“Devil knows!” answered Quilt; “but I believe he's in the hands of Blueskin, so there's no doubt he'll soon be on the high-road to Tyburn.”

“Poor Jack!” sighed Thames. “You needn't gag me,” he added, “I'll not cry out.”

“We won't trust you, my youngster,” answered the janizary. And, thrusting a piece of iron into his mouth, he forced him out of the room.

Sir Rowland witnessed these proceedings like one stupified. He neither attempted to prevent his nephew's departure, nor to follow him.

Jonathan kept his keen eye fixed upon him, as he addressed himself for a moment to the Hollander.

“Is the case of watches on board?” he asked in an under tone.

“Ja,” replied the skipper.

“And the rings?”

“Ja.”

“That's well. You must dispose of the goldsmith's note I gave you yesterday, as soon as you arrive at Rotterdam. It'll be advertised to-morrow.”

“De duivel!” exclaimed Van Galgebrok, “Very well. It shall be done as you direct. But about dat jonker,” he continued, lowering his voice; “have you anything to add consarnin' him? It's almosht a pity to put him onder de water.”

“Is the sloop ready to sail?” asked Wild, without noticing the skipper's remark.

“Ja,” answered Van; “at a minut's nodish.”

“Here are your despatches,” said Jonathan with a significant look, and giving him a sealed packet. “Open them when you get on board—not before, and act as they direct you.”

“I ondershtand,” replied the skipper, putting his finger to his nose; “it shall be done.”

“Sir Rowland,” said Jonathan, turning to the knight, “will it please you to remain here till I return, or will you accompany us?”

“I will go with you,” answered Trenchard, who, by this time, had regained his composure, and with it all his relentlessness of purpose.

“Come, then,” said Wild, marching towards the door, “we've no time to lose.”