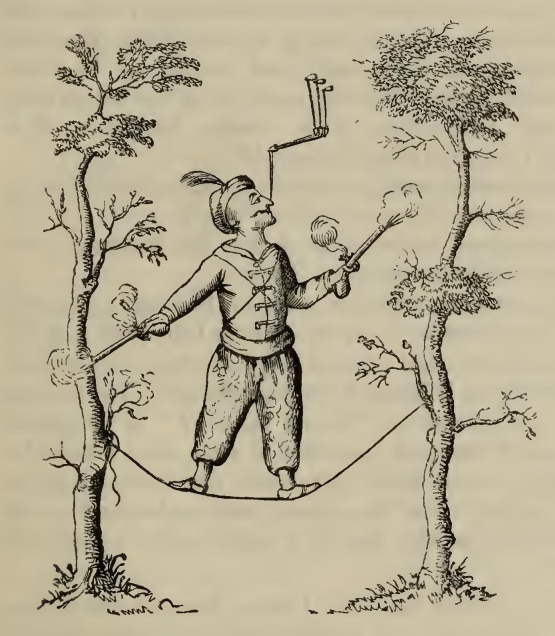

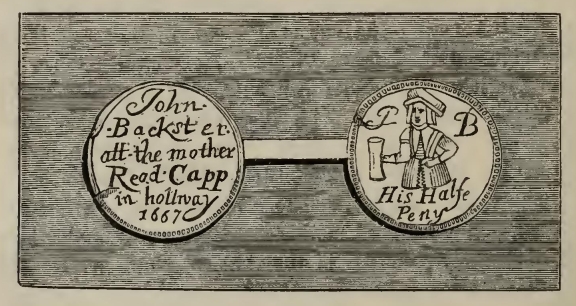

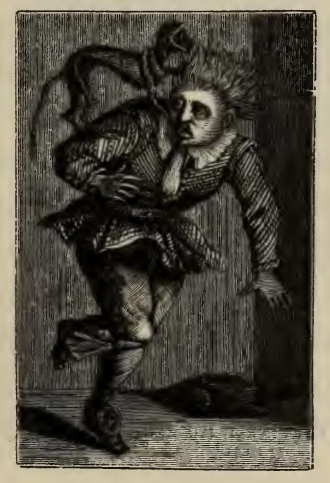

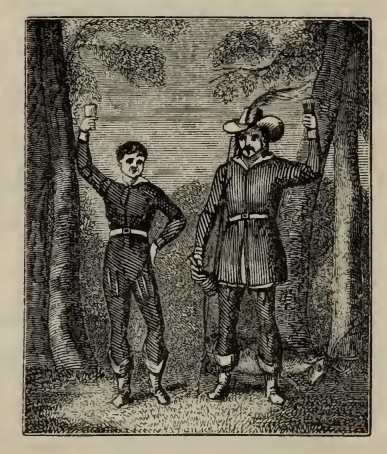

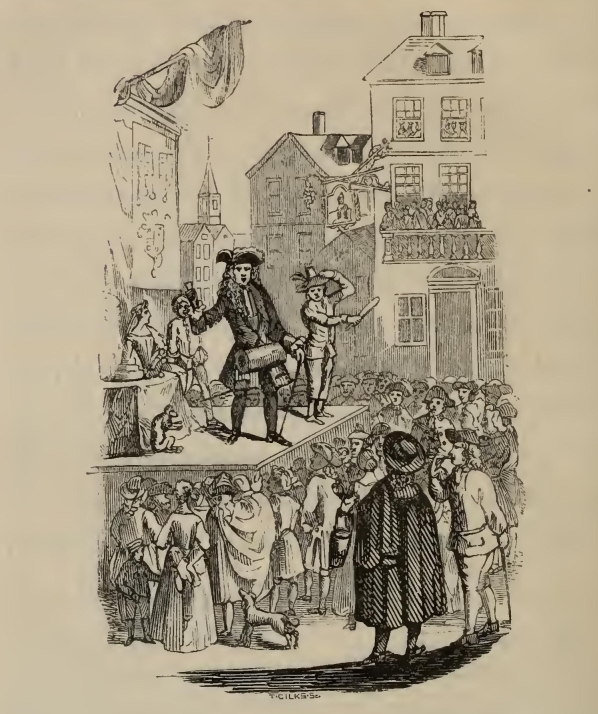

“Merrie England in the Olden Time” having found favour with the Public in “Bentley's Miscellany,” puts forth new attractions in the present volumes. It has received numerous and important corrections and additions; the story has been illustrated by those eminent artists Messrs. Leech and Robert Cruikshank; and fac-similes, faithfully executed by that “cunninge” limner Mr. Thomas Gilks, of rare and unique portraits of celebrated Players, Jesters, Conjurers, and Mountebanks, (preserved only in the cabinets of the curious,) exhibit “lively sculptures” of once popular drolls and wizards that shook the sides and “astonished the nerves” of our jovial-hearted and wondering ancestors.

To supply the antiquarian portion of Merrie England, a library and a collection of prints and drawings of a highly curious and recherche character have been resorted to; and, though the task of concentrating and reducing into moderate compass such ample materials has not been an easy one,

“The labour we delight in physics pain.”

This, and a large share of public approval, have made it a “labour of love.”

In that part which is purely fiction the characters can best speak for themselves.

Canonbury,

Oct. 1841.

CONTENTS

MERRIE ENGLAND IN THE OLDEN TIME.

Youth is the season of ingenuousness and enjoyment, when we desire to please, and blush not to own ourselves pleased. At that happy period there is no affectation of wisdom; we look only to the bright and beautiful: we inquire not whether it be an illusion; it is sufficient that fairy land, with its flowers of every hue, is the path on which we tread. To youth succeeds manhood, with its worldly prudence: then we are taught to take nothing, not even happiness, upon trust; to investigate until we are lost in the intricacies of detail; and to credit our judgment for what is due only to our coldness and apathy. We lose all sympathy for the past; the future is the subject of our anxious speculation; caution and re serve are our guardian angels; and if the heart still throb with a fond emotion, we stifle it with what speed we may, as detrimental to our interests, and unworthy our new-born intelligence and philosophy. A short acquaintance with the world will convince the most sanguine that this stage is not the happiest; that ambition and mercenary cares make up the tumultuous scene; and though necessity compel a temporary submission, it is good to escape from the toils, and breathe a purer air. This brings us to another period, when reflection has taught us self-knowledge, and we are no longer overwise in our own esteem. Then returns something of the simplicity that characterised our early days. We welcome old friends; have recourse to old amusements, and the fictions that enchained our youthful fancy resume their wonted spell.

We remember the time when just emerging from boyhood, we affected a disdain for the past. We had put on the man, and no urchin that put on for the first time his holiday suit, felt more inexpressible self-complacency. We had roared at pantomime, and gaped with delight at the mysteries of melodrame—but now becoming too sober to be amused, “puerile!”

“ridiculous!” were the critical anathemas that fulminated from our newly-imbibed absolute wisdom! It might be presumption to say that we have since grown wiser; certain it is, we are become less pleased with ourselves, and consequently more willing to be pleased.

Gentle Reader, we are old enough to have enjoyed, and young enough to remember many of the amusements, wakes, and popular drolleries of Merrie England that have long since submitted to “the tooth of time and razure of oblivion.” Like Parson Adams, we have also been a great traveller—in our books! Reversing the well-known epigram,

“Give me the thing that's pretty, smart, and new:

All ugly, old, odd things, I leave to you,”

we have all our life been a hunter after oddities. We have studied attentively the past. For the future we have been moderately solicitous; there being so many busy economists to take the unthankful task off our hands. We have lost our friend rather than our joke, when the joke has been the better of the two; and have been free of discourse where it has been courteously received, preferring (in the cant of pompous ignorance, which is dear at any price!) to make ourselves “cheap” rather than be set down as exclusive and unkind. Disappointments we have had, and sorrows, with ample experience of the world's ingratitude. But life is too short to harbour enmities; and to be resentful is to be unhappy. This may have cast a transient shade over our lucubrations, which let thy happier humour shine upon and dispel! Wilt thou accept us for thy Cicerone through a journey of strange sights? the curiosities of nature, and the whimsicalities of art. We promise thee faster speed than steam-boat and railroad: for thou shalt traverse the ground of two centuries in two hours! With pleasant companions by the way, free from the perils of fire and flood,

“Fancy, like the finger of a clock,

Runs the great circuit, and is still at home.”

Dost thou think because thou art virtuous there shall be no more cakes and ale?” was the admirable reply of Sir Toby Belch to Malvolio when he would have marred his Christmas * merrymaking with Sir Andrew and the Clown. And how beautiful is Olivia's reply to the self-same precisian when the searching apophthegms of the “foolish wise man, or wise foolish man,” sounded like discords in his ears. “O, you are sick of selflove, Malvolio, and taste all with a distempered appetite. To be generous, guiltless, and of free disposition, is to take those things for bird-bolts that you deem cannon-bullets. There is no slander in an allowed fool, though he do nothing but rail; nor no railing in a known discreet man, though he do nothing but reprove.”

* Christmas being the season when Jack Frost commonly takes

us by the nose, the diversions are within doors, either in

exercise, or by the fire-side. Viz. a game at blind-man's-

buff, puss-in-the-corner, questions and commands, hoop-and-

hide; stories of hobgoblins, Tom-pokers, bull-beggars,

witches, wizards, conjurors, Doctor Faustus, Friar Bacon,

Doctor Partridge, and such-like horrible bodies, that

terrify and delight!

“O you merry, merry souls,

Christmas is a-coming:

We shall have flowing bowls,

Dancing, piping, drumming.

Delicate minced pies,

To feast every virgin;

Capon and goose likewise,

Brawn, and dish of sturgeon.

We hate to be everlastingly bewailing the follies and vices of mankind; and gladly turn to the pleasanter side of the picture, to contemplate something that we can love and emulate. We know

Then for Christmas-box,

Sweet plum-cake and money;

Delicate holland smocks,

Kisses sweet as honey.

Hey for Christmas ball,

Where we will be jolly;

Coupling short and tall,

Kate, Dick, Ralph, and Molly.

To the hop we go,

Where we'll jig and caper;

Cuckolds all a-row—

Will shall pay the scraper.

Tom must dance with Sue,

Keeping time with kisses;

We'll have a jolly crew

Of sweet smirking Misses!”—Old Song.

There are such things as opaque wits and perverse minds, as there are squinting eyes and crooked legs; but we desire not to entertain such guests either as companions or foils. We come not to the conclusion that the world is split into two classes, viz. those who are and those who ought to be hanged; that we should believe every man to be a rogue till we find him honest. There is quite virtue enough in human life to make our journey moderately happy. We are of the hopeful order of beings, and think this world a very beautiful world, if man would not mar it with his pride, selfishness, and gloom.

It has been a maxim among all great and wise nations to encourage public sports and diversions. The advantages that arise from them to a state; the benefit they are to all degrees of the people; the right purposes they may be made to serve in troublesome times, have generally been so well understood by the ruling powers, that they have seldom permitted them to suffer from the assaults of narrow-minded and ignorant reformers.

Our ancestors were wise when they appointed amusements for the people. And as religious services (which are the means, not the end—the road to London is not London) were never intended for a painful duty, the “drum ecclesiastic,” which in latter times called its recruits to pillage and bloodshed, often summoned Punch, Robin Hood, and their merry crew, to close the motley ceremonies of a holy-appointed day! Then was the calendar Devotion's diary and Mirth's manual! Rational pleasure is heightened by participation; solitary enjoyment is always selfish. Who ever inquires after a sour recluse, except his creditors and next heir? Nobody misses him when there are so many more agreeable people to supply his place. Of what use is such a negative, “crawling betwixt earth and heaven?” If he hint that Diogenes, * dying of the dumps, may be found at home in his tub, who cares to disinter him? Oh, the deep solitude of a great city to a morose and selfish spirit! The Hall of Eblis is not more terrible. Away, then, with supercilious exclusiveness! 'Tis the grave of the affections! the charnel-house of the heart! What to us is the world, if to the world we are nothing?

We delight to see a fool ** administer to his brethren.

* Diogenes, when he trod with his dirty cobbled shoes on the

beautiful carpets of Plato, exclaimed triumphantly, “I tread

upon the pride of Plato!”—“Yes,” replied Plato, “but with

a greater pride!”

** “A material fool,” as Jacques describes Touchstone. Such

was Dr. Andrew Borde, the well-known progenitor of Merry

Andrews; and the presumed author of the “Merry Tales of the

Wise Men of Gotham,” composed in the early part of the

sixteenth century. “In the time of Henry VIII. and after,”

(says Anthony à Wood,) “it was accounted a book full of wit

and mirth by the scholars and gentlemen.” It is thus

referred to in an old play of 1560:—

“Ha! ha! ha! ha! ha!

I must needs laughe in my slefe.

The wise men of Gotum are risen againe.”

If merriment sometimes ran riot, it never exhibited itself in those deep-laid villanies so rife among the pretenders to sanctity and mortification. An appeal to “clubs” among the London apprentices; the pulling down of certain mansions of iniquity, of which Mrs. Cole, * in after days, was the devout proprietress; a few broken heads at the Bear Garden; the somewhat opposite sounds of the “belles tolling for the lectorer, and the trumpets sounding to the stages,” ** and sundry minor enormities, were the only terrible results of this national licence. Mark what followed, when masking, morris-dancing, ***

* Foote's “Minor.” Act i. scene 1.

** Harleian MSS. No. 286.

*** The morris-dance was one of the most applauded

merriments of Old England. Robin Hood, Little John, Friar

Tuck, Maid Marian, the Queen or Lady of the May, the fool,

the piper, to which were afterwards added a dragon, and a

hobbyhorse, were the characters that figured away in that

truly ancient and grotesque movement. Will Kempe, “the

comical and conceited jest-monger, and vicegerent to the

ghost of Dicke Tarleton,” who “raised many a roar by making

faces and mouths of all sorts,” danced the morris with his

men of Gotham, in his “Nine daies' wonder from London to

Norwich.” Kempe's “new jigg,” rivalled in popularity his

Peter in Romeo and Juliet; Dogberry, in “Much ado about

nothing;” and

Justice Shallow, of which he was the original performer. In

“Jacke Drum's Entertainment,” 4to. 1601, is the following

song:

ON THE INTRODUCTION OF A WHITSUN MORRIS-DANCE.

“Skip it and trip it nimbly, nimbly,

Tickle it, tickle it lustily,

Strike up the tabour for the wenches' favour,

Tickle it, tickle it, lustily.

Let us be seene on Hygate Greene,

To dance for the honour of Holloway.

Sing we are come hither, let us spare for no leather,

To dance for the honour of Holloway.”

May games, stage-plays, * fairs, and the various pastimes that delighted the commonalty, were sternly prohibited. The heart sickens at the cant and cruelty of these monstrous times, when fanaticism, with a dagger in one hand, and “Hooks and Eyes for an Unbeliever's Breeches,” in the other, revelled in the destruction of all that was intellectual in the land.

* Plays were suppressed by the Puritans in 1633. The actors

were driven off the stage by the soldiers; and the only

pleasantry that Messrs. “Praise-God-Barebones” and “Fight-

the-good-fight,” indulged in, was “Enter red coat, exit hat

and cloak;” a cant phrase in reference to this devout

tyranny. Randolph, in “The Muses' Looking-glass,” makes a

fanatic utter this charitable prayer:

“That the Globe,

Wherein (quoth he) reigns a whole world of vice,

Had been consum'd, the Phoenix burnt to ashes;

The Fortune whipp'd for a blind—Blackfriars!

He wonders how it 'scap'd demolishing I' the time of

Reformation: lastly, he wished The Bull might cross the

Thames to the Bear Gardens, And there be soundly baited.

In 1599 was published “The overthrow of Stage Playes, by way

of controversie betwixt D. Gager and D. Rainolde, where-

in all the Reasons that ean be made for them are notably

refuted, the objections answered, and the case so clear and

resolved as that the judgment of any man that is not froward

and perverse may casilic be satisfied; wherein is

manifestly proved that it is not onely unlawfull to bee an

actor, but a beholder of those vanities, &e. &c.”

When the lute, the virginals, the viol-de-gambo, were hushed for the inharmonious bray of their miserable conventicles, * and the quaintly appropriate signs ** of the ancient taverns and music shops were pulled down to make room for some such horrible effigy as we see dedicated to their high priest, John Knox, on a wall in the odoriferous Canongate of Modern Athens. ***

* “What a poor pimping business is a Presbyterian place of

worship; dirty, narrow and squalid: stuck in the corner of

an old Popish garden such as Linlithgow, and much more,

Melrose.”—Robert Burns.

** Two wooden heads, with this inscription under it: “We

three loggerheads be.” The third was the spectator. The

tabor was the ancient sign of a music shop. Tarleton kept an

eating-house with this sign. Apropos of signs—Two Irishmen

beholding a hatchment fixed against a house, the one

inquired what it was? “It's a bad sign!” replied the other

mysteriously. Paddy being still at fault as to the meaning,

asked for further explanation.—“It's a sign,” cried his

companion with a look of immeasurable superiority, “that

somebody is dead!”

*** Those who would be convinced of the profaneness of the

Cameronians and Covenanters have only to read “Scotch

Presbyterian Eloquence displayed, or the Folly of their

teaching discovered from their Books, Sermons, and Prayers,”

1738,—a volume full of ludicrous impieties. We select one

specimen.

Mr. William Vetch, preaching at Linton, in Tiviotdale, said,

“Our Bishops thought they were very secure this long time.

“Like Willie Willie Wastel,

I am in my castel.

All the dogs in the town

Dare nor ding me down.

“Yea, but there is a doggie in Heaven that has dung them all

down.”

Deep was the gloom of those dismal days! The kitchens were cool; the spits motionless. * The green holly and the mystic mistletoe ** were blooming abominations. The once rosy cheeks of John Bull looked as lean as a Shrove-Tuesday pancake, and every rib like the tooth of a saw.

* “The Lamentable Complaints of Nick Froth the Tapster, and

Ruleroast the Cook,” 4to. 1641.

* The magical properties of the mistletoe are mentioned both

by Virgil and Ovid; and Apuleius has preserved some verses

of the poet Lelius, in which he mentions the mistletoe as

one of the things necessary to make a magician. In the dark

ages a similar belief prevailed, and even to the present day

the peasants of Holstein, and some other countries, call the

mistletoe the “Spectre's Wand,” from a supposition that

holding a branch of mistletoe in the hand will not only

enable a man to see ghosts, but to force them to speak to

him! The mistletoe is peculiar to Christmas.

Rampant were those times, when crop-ear'd Jack Presbyter was as blythe as shepherd at a wake. * Down tumbled the Maypoles **—no more music

* “We'll break the windows which the whore Of Babylon hath

planted,

And when the Popish saints are down,

Then Burges shall be sainted;

We'll burn the fathers' learned books,

And make the schoolmen flee;

We'll down with all that smells of wit,

And hey, then, up go we!”

** The downfall of May-games, 4to. 1660. By Thomas Hall, the

canting parson of King's-Norton.—Hear the caitiff,

“There's not a knave in all the town,

Nor swearing courtier, nor base clown,

Nor dancing lob, nor mincing quean,

Nor popish clerk, be't priest or dean,

Nor Knight debauch'd nor gentleman,

That follows drab, or cup, or can,

That will give thee a friendly look,

If thou a May-pole canst not brook.”

On May 1, 1517, the unfortunate shaft, or May-pole, gave

rise to the insurrection of that turbulent body, the London

apprentices, and the plundering of the foreigners in the

city, whence it got the name of Evil May-day. From that time

the offending pole was hung on a range of hooks over the

doors of a long row of neighbouring houses. In the 3rd of

Edward VI. an over-zealous fanatic called Sir Stephen began

to preach against this May-pole, which inflamed his audience

so greatly, that the owner of every house over which it hung

sawed off as much as depended over his premises, and

committed piecemeal to the flames this terrible idol!

The “tall May-pole” that “onee o'erlooked the Strand,”

(about the year 1717,) Sir Isaac Newton begged of the

parish, and it was carried to Wanstead in Essex, where it

was erected in the park, and had the honour of raising the

greatest telescope then known. The New Church occupies its

site.

“But now (so Anne and piety ordain),

A church collects the saints of Drury Lane.”

and dancing! * For the disciples of Stubbes and Prynne having discovered by their sage oracles, that May-games were derived from the Floralian Feasts and interludes of the pagan Romans, which were solemnised on the first of May; and that dancing round a May-pole, adorned with garlands of flowers, ribbons, and other ornaments, was idolatry, after the fashion of Baal's worshippers, who capered about the altar in honour of their idol; resolved that the Goddess Flora should no longer receive the gratulations of Maid Marian, Friar Tuck, and Robin Hood's merry men, on a fine May morning; a superstition derived from the Sibyl's books, horribly papistical and pagan.

* “Good fellowes must go learne to daunce

The brydeal is full near a:

There is a brail come out of Fraunce,

The fyrst ye harde this yeare a.

For I must leape, and thou must hoppe,

And we must turne all three a;

The fourth must bounce it like a toppe,

And so we shall agree a.

praye the mynstrell make no stoppe,

For we wyll merye be a.”

From an unique black letter ballad, printed in 1569,

“Intytuled, 'Good Fellowes must go learne to Daunce.'”

Nor was the “precise villain” less industrious in confiscation and sacrilege. * Painted windows—Lucifer's Missal drawings!—he took infinite pains to destroy; and with his long pike did the devil's work diligently. He could endure no cross ** but that on silver; hence the demolition of those beautiful edifices that once adorned Cheapside, and other remarkable sites in ancient times.

* Sir Robert Howard has drawn an excellent picture of a

Puritan family, in his comedy of “The Committee.” The

personages are Mr. Day, chairman to the committee of

sequestrations; Mrs. Day, “the committee-man's utensil,”

with “curled hair, white gloves, and Sabbath-day's cinnamon

waistcoat;” Abel, their booby son, a fellow “whose heart is

down in his breeches at every turn and Obadiah, chief clerk,

dull, drawling, and heinously given to strong waters. We are

admitted into the sanctum sanctorum, of pious fraud, where

are seated certain honourable members, whose names cannot

fail to enforce respect. Nehemiah Catch, Joseph Blemish,

Jonathan Headstrong, and Ezekiel Scrape! The work of plunder

goes bravely on. The robbing of widows and orphans is

“building up the new Zion.” A parcel of notched rascals

laying their heads together to cheat is “the cause of the

righteous prospering when brethren dwell together in unity

and when a canting brother gives up lying and the ghost, Mr.

Day remarks that “Zachariah went off full of exhortation!”

It was at the sacking of Basing House, the seat of the

venerable Marquis of Winchester, that Harrison, the regicide

and butcher's son, shot Major Robinson, exclaiming as he did

the deed, “Cursed is he that doeth the work of the Lord

negligently.” Hugh Peters, the buffooning priest, was of the

party.

** The erection of upright stone crosses is generally

supposed to have dated its origin from the custom which the

first Christians in this island adopted of inscribing the

Druid stones with a cross, that the worship of the converted

idolator might be transferred from the idol to the emblem of

his faith; and afterwards the Saxon kings frequently erected

crosses previously to a battle, at which public prayers were

offered up for victory. After the Norman conquest crosses

became common, and were erected in market-places, to induce

honesty by the sanction of religion: in churchyards, to

inspire devout and pious feelings; in streets, for the

deposit of a corpse when borne to its last home; and for

various other purposes. Here the beggar stationed himself,

and asked alms in the name of Him who suffered on the cross.

They were used for landmarks, that men might learn to

respect and hold sacred the boundaries of another's

property. Du Cange says that crosses were erected in the

14th Richard II. as landmarks to define the boundaries

between Kesteven and Holland. They were placed on public

roads as a check to thieves, and to regulate processions. At

the Reformation (?!! ) most of the crosses throughout the

kingdom were destroyed, when the sweeping injunction of

Bishop Horne was formally promulgated at his Visitation in

1571, that all images of the Trinity in glass windows, or

other places of the church, be put out and extinguished,

together with the stone cross in the churchyard! We devoutly

hope, as Dr. Johnson hoped of John Knox, that Bishop Horne

was buried in a cross-road.

The sleek rogue read his Bible * upside down, and hated his neighbour: his piety was pelf; his godliness gluttony.

* “They like none but sanctified and shuttle-headed weavers,

long-winded boxmakers, and thorough-stitching cobblers,

thumping felt-makers, jerking coachmen, and round-headed

button-makers, which spoyle Bibles while they thumb over the

leaves with their greasie fingers, and sit by the fireside

scumming their porridge-pot, while their zeal seethes over

in applications and interpretations of Scripture delivered

to their ignorant wives and handmaids, with the name and

title of deare brethren and especially beloved sisters.”—

The doleful Lamentation of Cheapside Crosse, or Old England

sick of the Staggers, 1641.

His grace * was as long as his face. The gnat, like Macbeth's “Amen,” stuck in his throat; but the camel slid down merrily. What a weary, working-day world would this have been under his unhospitable dominion! ** How unlovely and lachrymose! how sectarian and sinister! A bumper of bitters, to be swallowed with a rising gorge, and a wry face! All literature would have resolved itself into—

* One Lady D'Arcy, a well-jointured, puritanical widow,

having invited the next heir in the entail to dine with her,

asked him to say grace. The young gentleman, thinking that

her ladyship had lived quite long enough, expressed his

wishes thus graciously:—

“Good Lord of thy mercy,

Take my good Lady D'Arcy

Unto her heavenly throne;

That I, little Frank,

May sit in my rank,

And keep a good house of my own!”

** John Knox proclaimed the mild sentence, which was loudly

re-echoed by his disciples, that the idolator should die the

death, in plain English (or rather, God be thanked! in plain

Scotch) that every Catholic should be hanged. The bare

toleration of prelacy—of the Protestant prelacy!—was the

guilt of soul-murder. These were the merciful Christians!

the sainted martyrs! who conducted the inquisitorial tyranny

of the high commission, and imposed the test of that piece

of impious buffoonery, the “Holy League and Covenant!!” who

visited the west of Scotland with the free quarters of the

military, and triumphed so brutally over the unfortunate,

patriotic and gallant Montrose. The Scotch Presbyterians

enacted that each episcopalian was liable to transportation

who should baptize a child, or officiate as a clergyman to

more than Jour persons, besides the members of his own

family!

—“The plain Pathway to Penuriousness;” Peachwns “Worth of a Penny, or a caution to keep Money;” and the “Key to unknowne Knowledge, or a Shop of Five Windows”

“Which if you do open, to cheapen and copen,

You will be unwilling, for many a shilling,

To part with the profit that you shall have of it;”

and the drama, which, whether considered as a school of eloquence or a popular entertainment, is entitled to national regard, would have been proscribed, because—having neither soul for sentiment, eye for beauty, nor ear for poetry, it was his pleasure to be displeased. His humanity may be summed up in one short sentence, “I will take care, my dear brother, you shall not keep your bed in sickness, for I will take it from under you.” There are two reasons why we don't trust a man—one, because we don't know him, and the other because we do. Such a man would have shouted “Hosan-nah!” when the Saviour entered Jerusalem in triumph; and cried “Crucify him!” when he went up the mountain to die.

Seeing how little party spirit, religious controversy, and money-grubbing have contributed to the general stock of human happiness—that pre-eminence in knowledge is

“Only to know how little can be known,

To see all others' faults, and feel our own,”

we cry, with St. Patrick's dean, “Vive la bagatelle!” Democritus lived to an hundred. Death shook, not his dart, but his sides, at the laughing philosopher, and “delay'd to strike” till his lungs had crowed their second jubilee: while Heraclitus was Charon's passenger at threescore. But the night wanes apace; to-morrow we must rise with the lark. Fill we a cup to Mercury, à bon repos!

A bumper at parting! a bumper so bright,

Though the clock points to morning, by way of good

night!

Time, scandal, and cards, are for tea-drinking souls!

Let them play their rubbers, while we ply the bowls!

Oh who are so jocund, so happy as we?

Our skins full of wine, and our hearts full of glee!

Not buxom Dame Nature, a provident lass!

Abhors more a vacuum, than Bacchus's glass,

Where blue-devils drown, and where merry thoughts

swim—

As deep as a Quaker, as broad as his brim!

Like rosy fat friars, again and again

Our beads we have told, boys I—in sparkling champagne!

Our gravity's centre is good vin de grave,

Pour'd out to replenish the goblet concave;

And tell me what rubies so glisten and shine,

Like the deep blushing ruby of Burgundy wine?

His face in the glass Bibo smiles when he sees;

For Fancy takes flight on no wing like the bee's!

If truth in a well lie,—ah! truth, well-a-day!—

I'll seek it in “Fmo,”—the pleasantest way!

Let temperance, twankay, teetotallers trump;

Your sad, sober swiggers at “Veritas” pump!

If water flow hither, so crystal and clear,

To mix with our wine—'tis humanity's tear.

When Venus is crusty, and Mars in a miff,

Their tipple is prime nectar-toddy and stiff,—

And shall we not toast, like their godships above,

The lad we esteem, and the lady we love?

Be goblets as sparkling, and spirits as light,

Our next merry meeting! A bumper—good night!

“The flow'ry May, who from her green lap throws

The yellow cowslip and the pale primrose.”

'Tis Flora's holiday, and in ancient times the goddess kept it with joyous festivity. Ah! those ancient times, they are food for melancholy. Yet may melancholy be made to “discourse most eloquent music,”—

“O why was England 'merrie' called, I pray you tell

me why?—

Because Old England merry was in merry times gone by!

She knew no dearth of honest mirth to cheer both son

and sire,

But kept it up o'er wassail cup around the Christmas

fire.

When fields were dight with blossoms white, and leaves

of lively green,

The May-pole rear'd its flow'ry head, and dancing round

were seen

A youthful band, join'd hand in hand, with shoon and

kirtle trim,

And softly rose the melody of Flora's morning hymn.

Her garlands, too, of varied hue the merry milkmaid

wove,

And Jack the Piper caprioled within his dancing grove;

Will, Friar Tuck, and Little John, with Robin Hood

their king,

Bold foresters! blythe choristers! made vale and moun

tain ring.

On every spray blooms lovely May, and balmy zephyrs

breathe—

Ethereal splendour all above! and beauty all beneath!

The cuckoo's song the woods among sounds sweetly as of

old;

As bright and warm the sunbeams shine,—and why

should hearts grow cold?” *

* This ballad has been set to very beautiful music by Mr. N.

I. Sporle. It is published by T. E. Purday, 50, St. Paul's

Church Yard.

“A sad theme to a merry tune! But had not May another holiday maker? when the compassionate Mrs. Montague walked forth from her hall and bower to greet with a smile of welcome her grotesque visitor, the poor little sweep.”

Thy hand, Eugenio, for those gentle words! Elia would have taken thee to his heart. Be the turf that lies lightly on his breast as verdant as the bank whereon we sit. On a cold, dark, wintry morning, he had too often been disturbed out of a peaceful slumber by his shrill, mournful cry; and contrasting his own warm bed of down with the hard pallet from which the sooty little chorister had been driven at that untimely hour, he vented his generous indignation; and when a heart so tender as Elia's could feel indignation, bitter must have been the provocation and the crime! But the sweep, with his brilliant white teeth, and Sunday washed face, is for the most part a cheerful, healthy-looking being. Not so the squalid, decrepit factory lad, broken-spirited, overworked, and half-starved! The little sweep, in process of time, may become a master “chum-mie,” and have (without being obliged to sweep it,) a chimney of his own: but the factory lad sees no prospect of ever emerging from his heart-sickening toil and hopeless dependance; he feels the curse of Cain press heavily upon him. The little sweep has his merry May-day, with its jigs, rough music, gingling money-box, gilt-paper cocked-hat, and gay patchwork paraphernalia. All days are alike to the factory lad,—“E'en Sunday shines no Sabbath-day to him.” His rest will be the Sabbath of the tomb!

Nothing is better calculated to brace the nerves and diffuse a healthful glow over body and mind than outdoor recreations. What is ennui? Fogs, and over-feeding, content grown plethoric, the lethargy of superabundance, the want of some rational pursuit, and the indisposition to seek one. What its cure?

“'Tis health, 'tis air, 'tis exercise—

Fling but a stone, the giant dies!”

The money-grub, pent up in a close city, eating the bread of carefulness, and with the fear of the shop always before his eyes, is not industrious. He is the droning, horse-in-a-mill creature of habit,—like a certain old lady of our acquaintance, who every morning was the first up in the house, and good-for-nothing afterwards. A century ago the advantages of early rising to the citizen were far more numerous than at present. A brisk walk of ten minutes brought him into the fields from almost any part of the town; and after luxuriating three or four miles amidst clover, sorrel, buttercups, aye, and corn to boot! the fresh breeze of morn, the fragrance of the flowers, and the pleasant prospect, would inspire happy thoughts: and, as nothing better sharpens the appetite than these delightful companions, what was wanting but a substantial breakfast to prepare him for the business of the day? For this certain frugal houses of entertainment were established in the rural outskirts of the Metropolis, *

* “This is to give notice to all Ladies and Gentlemen, at

Spencer's original Breakfasting-Hut, between Sir Hugh

Middleton's Head and St. John Street Road, by the New River

side, fronting Sadler's Wells, may be had every morning,

except Sundays, fine tea, sugar, bread, butter, and milk, at

four-penee per head; coffee at threepence a dish. And in the

afternoon, tea, sugar and milk, at threepence per head, with

good attendance. Coaches may come up to the farthest gar-

den-door next to the bridge in St. John Street Road, near

Sadler's Wells back gate.—Note. Ladies, &c. are desired to

take notice that there is another person set up in

opposition to me, the next door, which is a brick-house, and

faces the little gate by the Sir Hugh Middleton's, and

therefore mistaken for mine; but mine is the little boarded

place by the river side, and my backdoor faces the same as

usual; for

I am not dead, I am not gone,

Nor liquors do I sell;

But, as at first, I still go on,

Ladies, to use you well.

No passage to my hut I have,

The river runs before;

Therefore your care I humbly crave,

Pray don't mistake my door.

“Yours to serve,

Daily Advertiser, May 6, 1745. “S. Spencer.”

where every morning, “except Sundays, fine tea, sugar, bread, butter, and milk,” might be had at fourpence per head, and coffee “at three halfpence a dish.'” And as a walk in summer was an excellent recruit to the spirits after reasonable toil, the friendly hand that lifted the latch in the morning repeated the kind office at evening tide, and spread before him those refreshing elements that “cheer, but not inebriate;” with the harmless addition of music and dancing. Ale, wine, and punch, were subsequently included in the bill of fare, and dramatic representations. But of latter years the town has walked into the country, and the citizen can just espy at a considerable distance a patch of flowery turf, and a green hill, when his leisure and strength are exhausted, and it is time to turn homeward.

The north side of London was famous for suburban houses of entertainment. Midway down Gray's Inn Lane stands Town's End Lane (so called in the old maps), or Elm Street, which takes its name from some elms that once grew there. To the right is Mount Pleasant, and on its summit is planted a little hostelrie, which commanded a delightful prospect of fields, that are now annihilated; their site and our sight being profaned by the House of Correction and the Treadmill! Farther on, to the right, is Warner Street, which the lover of old English ballad poetry and music will never pass without a sigh; for there, while the town were applauding his dramatic drolleries,—and his beautiful songs charmed alike the humble and the refined,—their author, Henry Carey, in a fit of melancholy destroyed himself. *

* October 4, 1743.

Close by stood the old Bath House, which was built over a Cold Spring by one Walter Baynes, in 1697. * The house is razed to the ground, but the spring remains. A few paces forward is the Lord Cobham's Head, ** transmogrified into a modern temple for tippling; its shady gravel walks, handsome grove of trees, and green bowling alleys, are long since destroyed. Its opposite neighbour was (for not a vestige of the ancient building remains) the Sir John Oldcastle, *** where the wayfarer was invited to regale upon moderate terms.

* According to tradition, this was once the bath of Nell

Gwynn. In Baynes's Row, close by, lived for many years the

celebrated clown Joe Grimaldi.

** “Sir,—Coming to my lodging in Islington, I called at the

Lord Cobham's Head, in Cold Bath Fields, to drink some of

their beer, which I had often heard to be the finest,

strongest, and most pleasant in London, where I found a very

handsome house, good accommodation, and pleasantly situated.

I afterwards walked in the garden, where I was greatly

surprised to find a very handsome grove of trees, with

gravel walks, and finely illuminated, to please the company

that should honour them with drinking a tankard of beer,

which is threepence. There will be good attendance, and

music of all sorts, both vocal and instrumental, and will

begin this day, being the 10th of August.

“I am yours,

“Tom Freeman.”

Daily Advertiser, 9th August 1742.

*** “Sir,—A few days ago, invited by the serenity of the

evening, I made a little excursion into the fields.

Returning home, being in a gay humour, I stopt at a booth

near Sir John Oldcastle's, to hear the rhetoric of Mr.

Andrew. He used so much eloquence to persuade his auditors

to walk in, that I (with many others) went to see his

entertainment; and I never was more agreeably amused than

with the performances of the three Bath Morris Dancers. They

showed so many astonishing feats of strength and activity,

so many amazing transformations, that it is impossible for

the most lively imagination to form an adequate idea

thereof. As the Fairs are coming on, I presume these

admirable artists will be engaged to entertain the town; and

I assure your readers they can't spend an hour more

agreeably than in seeing the performances of these wonderful

men.

“I am, &c.

Daily Advertiser, 27th July 1743.

See a rare print, entituled “A new and exact prospect of

the North side of the City of London, taken from the Upper

Pond near Islington. Printed and sold by Thomas Bake-well,

Print and Map-seller, over against Birching Lane, Corn-hill,

August 5, 1730.”

Show-booths were erected in this immediate neighbourhood for Merry-Andrews and mor-ris-dancers. Onward was the Ducking Pond; * (“Because I dwell at Hogsden,” says Master Stephen, in Every Man in his Humour, “I shall keep company with none but the archers of Finsbury or the citizens that come a ducking to Islington Ponds;”) and, proceeding in almost a straight line towards “Old Iseldon,” were the London Spa, originally built in 1206; Phillips's New Wells; *

* “By a company of English, French, and Germans, at

Phillips's New Wells, near the London Spa, Clerkenwell, 20th

August 1743.

“This evening, and during the Summer Season, will be

performed several new exercises of Rope-dancing, Tumbling,

Vaulting, Equilibres, Ladder-dancing, and Balancing, by Ma—

dame Kerman, Sampson Rogetzi, Monsieur German, and Monsieur

Dominique; with a new Grand Dance, called Apollo and Daphne,

by Mr. Phillips, Mrs. Lebrune, and others; singing by Mrs.

Phillips and Mrs. Jackson; likewise the extraordinary

performance of Herr Von Eeekenberg, who imitates the lark,

thrush, blackbird, goldfinch, canary-bird, flageolet, and

German flute; a Sailor's Dance by Mr. Phillips; and Monsieur

Dominique flies through a hogshead, and forces both heads

out. To which will be added The Harlot's Progress. Harlequin

by Mr. Phillips; Miss Kitty by Mrs. Phillips. Also, an exact

representation of the late glorious victory gained over the

French by the English at the battle of Dettingen, with the

taking of the White Household Standard by the Scots Greys,

and blowing up the bridge, and destroying and drowning most

part of the French army. To begin every evening at five

o'clock. Every one will be admitted for a pint of wine, as

usual.”

Mahommed Caratha, the Grand Turk, performed here his

“Surprising Equilibres on the Slack Rope.”

In after years, the imitations of Herr Von Eeekenberg were

emulated by James Boswell. (Bozzy!)

“A great many years ago, when Dr. Blair and I (Boswell) were

sitting together in the pit of Drury Lane Playhouse, in a

wild freak of youthful extravagance, I entertained the

audience prodigiously by imitating the lowings of a cow. The

universal cry of the galleries was, 'Encore the cow!' In the

pride of my heart I attempted imitations of some other

animals, but with very inferior effect. My revered friend,

anxious for my fame, with an air of the utmost gravity and

earnestness, addressed me thus, My dear sir, I would confine

myself to the cow!'”

the New Red Lion Cockpit; * the Mulberry Gardens; **

* “At the New Red Lion Cockpit, near the Old London Spaw,

Clerkenwell, this present Monday, being the 12th July 1731,

will be seen the Royal Sport of Cock-fighting, for two

guineas a-battle. To-morrow begins the match for four

guineas a-battle, and twenty guineas the old battle, and

continues all the week, beginning at four o'clock.”

** “Mulberry Gardens, Clerkenwell.—The gloomy clouds that

obscured the season, it is to be hoped, are vanished, and

nature once more shines with a benign and cheerful

influence. Come, then, ye honest sons of trade and industry,

after the fatigues of a well-spent day, and taste of our

rural pleasures! Ye sons of care, here throw aside your

burden! Ye jolly Bacchanalians, here regale, and toast your

rosy god beneath the verdant branches! Ye gentle lovers,

here, to soft sounds of harmony, breathe out your sighs,

till the cruel fair one listens to the voice of love! Ye who

delight in feats of war, and are anxious for our heroes

abroad, in mimic fires here see their ardour displayed!

“Note.—The proprietor being informed that it is a general

complaint against others who offer the like entertainments,

that if the gentle zephyrs blow ever so little, the company

are in danger of having their viands fanned away, through

the thinness of their consistence, promises that his shall

be of such a solidity as to resist, the air!”—Daily

Advertiser, July 8, 1745.

The latter part of this picturesque and poetical

advertisement is a sly hit at what, par excellence, are

called, “Vauxhall slices.”

the Shakspeare's Head Tavern and Jubilee Gardens; * the New Tunbridge Wells, **

* In 1742, the public were entertained at the “Shakspeare's

Head, near the New Wells, Clerkenwell,', with refreshments

of all sorts, and music; “the harpsichord being placed in so

judicious a situation, that the whole company cannot fail of

equally receiving the benefit.” In 1770, Mr. Tonas exhibited

“a great and pleasing variety of performances, in a

commodious apartment,” up one pair.

** These once beautiful tea-gardens (we remember them as

such) were formerly in high repute. In 1733, their Royal

Highnesses the Princesses Amelia and Caroline frequented

them in the summer time, for the purpose of drinking the

waters. They have furnished a subject for pamphlets, poems,

plays, songs, and medical treatises, by Ned Ward, George

Col-man the elder, Bickham, Dr. Hugh Smith, &c. Nothing now

remains of them but the original chalybeate spring, which is

still preserved in an obscure nook, amidst a poverty-

stricken and squalid rookery of misery and vice.

a fashionable morning lounge of the nobility and gentry during the early part of the eighteenth century; the Sir Hugh Middleton's Head; the Farthing Pie House; * and Sadler's Music House and “Sweet Wells.” ** A little to the left were Merlin's Cave,

* Farthing Pie Houses were common in the outskirts of London

a century ago. Their fragrance caught the sharp set citizen

by the nose, and led him in by that prominent member to

feast on their savoury fare. One solitary Farthing Pie House

(the Green Man) still stands near Portland Road, on the way

to Paddington.

** Originally a chalybeate spring, then a music-house, and

afterwards a “theatre-royal!” Cheesecakes, pipes, wine, and

punch, were formerly part of the entertainment.

“If at Sadler's sweet Wells the wine should be thick,

The cheesecakes be sour, or Miss Wilkinson sick,

If the fume of the pipe should prove pow'rful in June,

Or the tumblers be lame, or the bells out of tune,

We hope you will call at our warehouse at Drury,—We've a

curious assortment of goods, I assure you.” Foote's Prologue

to All in the Wrong, 1761.

Its rural vicinity made it a great favourite with the play-

going and punch-drinking citizens. See Hogarth's print of

“Evening.”

“A New Song on Sadler's Wells, set by Mr. Brett, 1740.

'At eve, when Sylvan's shady scene

Is clad with spreading branches green,

And varied sweets all round display'd,

To grace the pleasant flow'ry meads,

For those who're willing joys to taste,

Where pleasures flow and blessings last,

And God of Health with transport dwells,

Must all repair to Sadler's Wells.

The pleasant streams of Middleton

In gentle murmurs glide along,

In which the sporting fishes play,

To close each weary summer's day;

And music's charm, in lulling sounds,

With mirth and harmony abounds;

While nymphs and swains, with beaus and belles,

All praise the joys of Sadler's Wells.'”

Bagnigge Wells, * the English Grotto (which stood near the New River Water-works in the fields), and, farther in advance, White Conduit House. **

* Once the reputed residence of Nell Gwynn, which makes the

tradition of her visiting the “Old Bath House” more than

probable. F or. upwards of a century it has been a noted

place of entertainment.'Tis now almost a ruin! Pass we to

its brighter days, as sung in the “Sunday Ramble,” 1778:—

“Salubrious waters, tea, and wine,

Here you may have, and also dine;

But as ye through the gardens rove,

Beware, fond youths, the darts of love!”

** So called after an ancient conduit that once stood hard

by. Goldsmith, in the “Citizen of the World,” celebrates the

“hot rolls and butter' of White Conduit House. Thither

himself and a few friends would repair to tea, after having

dined at Highbury Barn. A supper at the Grecian, or Temple

Exchange Coffeehouses, closed the “Shoemaker's Holiday” of

this exquisite English Classic,—this gentle and benignant

spirit!

Passing by the Old Red Lion, bearing the date of 1415, and since brightened up with some regard to the taste of ancient times; and the Angel,—now a fallen one!—a huge structure, the architecture of which is anything but angelic, having risen on its ruins, we enter Islington, described by Goldsmith as “a pretty and neat town.” In ancient times it was not unknown to fame.

“What village can boast like fair Islington town

Such time-honour'd worthies, such ancient renown?

Here jolly Queen Bess, after flirting with Leicester,

'Undumpish'd'' herself with Dick Tarleton her jester.

Here gallant gay Essex, and burly Lord Burleigh,

Sat late at their revels, and came to them early;

Here honest Sir John took his ease at his inn—

Bardolph's proboscis, and Jack's double chin!

Here Finsbury archers disported and quaff'd,

Here Raleigh the brave took his pipe and his draught;

Here the Knight of St. John pledged the Highbury Monk,

Till both to their pallets reel'd piously drunk.” *

In “The Walks of Islington and Hogsdon, with the Humours of Wood Street Compter,” a comedy, by Thomas Jordan, 1641, the scene is laid at the Saracen's Head, Islington; and the prologue celebrates its “bottle-beer, cream, and (gooseberry) fools and the “Merry Milkmaid of Islington,

* “The Islington Garland.”

or the Rambling Gallant defeated,” a comedy, 1680, is another proof of its popularity. Poor Robin, in his almanac, 1676, says,

“At Islington

A Fair they hold,

Where cakes and ale

Are to be sold.

At Highgate and

At Holloway

The like is kept

Here every day.

At Totnam Court

And Kentish Town,

And all those places

Up and down.”

Drunken Barnaby notices some of its inns. Sir William d'Avenant, describing the amusements of the citizens during the long vacation, makes a “husband gray” ask,

“Where's Dame? (quoth he.) Quoth son of shop

She's gone her cake in milk to sop—

Ho! Ho!—to Islington—enough!”

Bonnel Thornton, in “The Connoisseur,” speaks of the citizens smoking their pipes and drinking their ale at Islington; and Sir William Wealthy exclaims to his money-getting brother, “What, old boy, times are changed since the date of thy indentures, when the sleek crop-eared 'prentice used to dangle after his mistress, with the great Bible under his arm, to St. Bride's on a Sunday, bring home the text, repeat the divisions of the discourse, dine at twelve, and regale upon a gaudy day with buns and beer at Islington or Mile-end.” *

Among its many by-gone houses of entertainment, the Three Hats has a double claim upon our notice. It was the arena where those celebrated masters, Johnson, ** Price, Sampson, *** and Coningham exhibited their feats of horsemanship, and the scene of Mr. Mawworm's early back-slidings. “I used to go,” (says that regenerated ranter to old Lady Lambert,) “every Sunday evening to the Three Hats at Islington; it's a public house; mayhap your Ladyship may know it.

* “The Minor,” Act I.

** Johnson exhibited in 1758, and Price, at about the same

time,—Coningham in 1772. Price amassed upwards of fourteen

thousand pounds by his engagements at home and abroad.

*** “Horsemanship, April 29, 1767.

Mr. Sampson will begin his famous feats of horsemanship next

Monday, at a commodious place built for that purpose in a

field adjoining the Three Hats at Islington, where he

intends to continue his performance during the summer

season. The doors to be opened at four, and Mr. Sampson will

mount at five. Admittance, one shilling each. A proper band

of music is engaged for the entertainment of those ladies

and gentlemen who are pleased to honour him with their

company.”

I was a great lover of skittles, too; but now I can't bear them.” At Dobney's Jubilee Gardens (now entirely covered with mean hovels), Daniel Wildman * performed equestrian exercises; and, that no lack of entertainment might be found in this once merry village, “a new booth, near Islington Turnpike,” for tricks and mummery, was erected in September 1767; “an insignificant erection, calculated totally for the lowest classes, inferior artisans, superb apprentices, and journeymen.”

Fields,

* “The Bees on Horseback!” At the Jubilee Gardens, Dobney's,

1772. “Daniel Wildman rides, standing upright, one foot on

the saddle, and the other on the horse's neck, with a

curious mask of bees on his face. He also rides, standing

upright on the saddle, with the bridle in his mouth, and, by

firing a pistol, makes one part of the bees march over a

table, and the other part swarm in the air, and return to

their proper places again.”

** Animadvertor's letter to the Printer of the Daily

Advertiser, 21st September 1767.

*** August 22nd, 1770, Mr. Craven stated in an

advertisement, that he had “established rules for the

strictest maintenance of order” at the Pantheon. How far

this was true, the following letter “To the Printer of the

St. James's Chronicle” will show:—

“Sir,—Happening to dine last Sunday with a friend in the

city, after coming from church, the weather being very

inviting, we took a walk as far as Islington. In our return

home towards Cold Bath Fields, we stepped in to view the

Pantheon there; but such a scene of disorder, riot, and

confusion, presented itself to me on my entrance, that I was

just turning on my heel in order to quit it, when my friend

observing that we might as well have something for our money

(for the doorkeeper obliged each of us to deposit a tester

before he granted us admittance), I acquiesced in his

proposal, and became one of the giddy multitude. I soon,

however, repented of my choice; for, besides having our

sides almost squeezed together, we were in danger every

minute of being scalded by the boiling water which the

officious Mercuries were circulating with the utmost

expedition through their respective districts. We therefore

began to look out for some place to sit down in, which with

the greatest difficulty we at length procured, and producing

our tickets, were served with twelve-penny worth of punch.

Being seated towards the front of one of the galleries, I

had now a better opportunity of viewing this dissipated

scene. The male part of the company seemed to consist

chiefly of city apprentices and the lower class of

tradesmen. The ladies, who constituted by far the greater

part of the assembly, seemed most of them to be pupils of

the Cyprian goddess, and I was sometimes accosted with,

'Pray, sir, will you treat me with a dish of tea?' Of all

the tea-houses in the environs of London, the most

exceptionable that I have had occasion to be in is the

Pantheon.

“I am sir, your constant reader,

“Speculator.”

“Chiswick, May 5, 1772.”

near Islington,” * was opened in 1770 for the sale of tea, coffee, wine, punch, &c., a “tester” being the price of admission to the promenade and galleries. It was eventually turned to a very different use, and converted into a lay chapel by the late Countess of Huntingdon.

* Spa-Fields (like “Jack Plackett's Common” the site of

Dalby Terrace, Islington) was famous for duck-hunting, bull-

baiting, and other low sports. “On Wednesday last, two women

fought for a new shift valued at half-a-guinea, in the Spaw-

Fields near Islington. The battle was won by a woman called

Bruising Peg, who beat her antagonist in a terrible

manner.”—22nd June 1768.

But by far the most interesting ancient hostelrie that has submitted to the demolishing mania for improvement is the Old Queen's Head, formerly situate in the Lower Street, Islington. This stately edifice was one of the most perfect specimens of ancient domestic architecture in England. Under its venerable roof Sir Walter Raleigh, it is said, “puffed his pipe;” and might not Jack Falstaff have taken his ease there, when he journeyed to string a bow with the Finsbury archers? For many years it was a pleasant retreat for retired citizens, who quaffed their nut-brown beneath its primitive porch, and indulged in reminiscences of the olden time. Thither would little Quick, King George the Third's favourite actor, resort to drink cold punch, and “babble” of his theatrical contemporaries. Plays * were formerly acted there.

* The following curious “Old Queen's Head” play-bill, temp.

George the Second, is presumed to be unique:—

G. II. R.

By a Company of Comedians, at the Queen's Head, in the Lower

Street, Islington,

This present evening will be acted a Tragedy, called the

Fair Penitent.

Sciolto, Mr. Malone.—Horatio, Mr. Johnson.

Altamont, Mr. Jones.—Lothario, Mr. Dunn.

Rosano, Mr. Harris.—Calista, Mrs. Harman.

Lavinia, Mrs. Malone.—Lucilla, Miss Platt.

To which will be added, a Farce called The Lying Valet.

Prices—Pit, 2s.; Gallery, Is. To begin at 7 o'clock.”

On Monday, October 19, 1829, it was razed to the ground, to make room for a misshapen mass of modern masonry. The oak parlour has been preserved from the wreck, and is well worth a visit from the antiquary. Canonbury Tavern and Highbury Barn still maintain their festive honours. Farther a-field are the Sluice, or Eel-pie House; Copenhagen House; Hornsey-wood House, formerly the hunting seat of Queen Elizabeth; Chalk Farm; Jack Straw's Castle; the Spaniards, &c. as yet undefiled by pitiful prettinesses of bricks and mortar, and affording a delightful opportunity of enjoying pure air and pastime. The canonised Bishop of Lichfield and Mademoiselle St. Agnes have each their wells. What perambulator of the suburbs but knows St. Chad, in Gray's Inn Lane, and St. Agnes le Clair, * at Hoxton? Paneras **

* Whit, in Jonson's Bartholomew Fair, promises to treat his

company with a clean glass, washed with the water of Agnes

le Clare.

** “At Edward Martin's, at the Hornes at Pancrass, is that

excellent water, highly approved of by the most eminent phy-

sitians, and found by long experience to be a powerful

antidote against rising of the vapours, also against the

stone and gravel. It likewise cleanses the body, purifies

and sweetens the blood, and is a general and sovereign help

to nature. I shall open on Whitson-Monday, the 24th of May

1697; and there will be likewise dancing every Tuesday and

Thursday all the summer season at the place aforesaid. The

poor may drink the waters gratis.” Then follow sixteen lines

of rhyme in praise of “this noble water,” and inviting

ladies and gentlemen to drink of it. Of this rare hand-bill

no other copy is known.

“And although this place (Paneras) be as it were forsaken of

all, and true men seldome frequent the same but upon de-vyne

occasions, yet is it visyted and usually haunted of roages,

vagabondes, harlettes and theeves, who assemble not ther to

pray, but to wayte for praye, and manie fall into their

hands clothed, that are glad when they are escaped naked.

Walke not ther too late.”—Speculi Britannio Pars, by John

Norden, MS. 1594.

and Hampstead Wells, renowned for their salubrious waters, are dried up. Though the two latter were professed marts for aqua pura, liquids more exhilarating were provided for those who relished stronger stimulants. We may therefore fairly assume that John Bull anciently travelled northward ho! when he rambled abroad for recreation.

As population increased, houses of entertainment multiplied to meet the demand. South, east, and west they rose at convenient distances, within the reach of a short stage, and a long pair of legs. Apollo Gardens, St. George's Fields; Bohemia's Head; Turnham Green; Cuper's Gardens, Lambeth; China Hall, Rotherhithe; Dog and Duck, St. George's Fields; Cherry Gardens Bowling-green, Rotherhithe; Cumberland Gardens, Vaux-hall; Spa Gardens, Bermondsey; Finch's Grotto Garden's, St. George's Fields; Smith's Tea Gardens, Vauxhall; Kendal House, Isleworth; New Wells, Goodman's Fields; Marble Hall, Vaux-hall; Staton's Tea-House, opposite Mary-le-bone Gardens; the Queen's Head and Artichoke, Mary-le-bone Fields; Ruckholt House, in Essex, of which facetious Jemmy Worsdale was the Apollo; Old Chelsea Bun-house; Queen Elizabeth's Cheesecake House, in Hyde Park; the Star and Garter Tavern, * and Don Saltero's coffeehouse, **

* “Star and Garter Tavern, Chelsea, 1763. Mr. Lowe will

display his uncommon abilities with watches, letters, rings,

swords, cards, and enchanted clock, which absolutely tells

the thoughts of any person in the company. The astonishing

Little Man, only four inches high, pays his respects to the

company, and vanishes in a flash of fire. Mr. Lowe commands

nine lighted candles to fly from the table to the top of the

ceiling! Added, a grand entertainment, with musick and

dancing, &c. &c.”

** The great attraction of Don Saltero's Coffeehouse was its

collection of rarities, a catalogue of which was published

as a guide to the visitors. It comprehends almost every

description of curiosity, natural and artificial. “Tigers'

tusks; the Pope's candle; the skeleton of a Guinea-pig; a

fly-cap monkey; a piece of the true Cross; the Four

Evangelists' heads cut on a cherry-stone; the King of

Morocco's tobacco-pipe;

Mary Queen of Scot's pincushion; Queen Elizabeth's prayer-

book; a pair of Nun's stockings; Job's ears, which grew on a

tree; a frog in a tobacco stopper,” and five hundred more

odd relies! The Don had a rival, as appears by “A Catalogue

of the Rarities to be seen at Adams's, at the Royal Swan, in

Kingsland Road, leading from Shoreditch Church, 1756.” Mr.

Adams exhibited, for the entertainment of the curious, “Miss

Jenny Cameron's shoes; Adam's eldest daughter's hat; the

heart of the famous Bess Adams, that was hanged at Tyburn

with Lawyer Carr, January 18, 1736-7; Sir Walter Raleigh's

tobacco-pipe; Vicar of Bray's clogs; engine to shell green

pease with; teeth that grew in a fish's belly; Black Jack's

ribs; the very comb that Abraham combed his son Isaac and

Jacob's head with; Wat Tyler's spurs; rope that cured

Captain Lowry of the head-ach, ear-ach, tooth-ach and belly-

ach; Adam's key of the fore and back door of the Garden of

Eden, &e. &e.” These are only a few out of five hundred

others equally marvellous. Is this strange catalogue a quiz

on Don Saltero?

Chelsea; Mary-le-bone and Ranelagh Gardens; *

* The Rotunda was first opened on the 5th of April, 1742,

with a public breakfast. At Ranelagh House (Gentleman's

Magazine for 1767) on the 12th of May, were performed the

much-admired catches and glees, selected from the curious

collection of the Catch Club; being the first of the kind

publickly exhibited in this or any other kingdom. The

entertainment consisted of the favourite catches and glees,

composed by the most eminent masters of the last and present

age, by a considerable number of the best vocal and

instrumental performers. The choral and instrumental parts

were added, to give the catches and glees their proper

effect in so large an amphitheatre; being composed for that

purpose by Dr. Arne. The Masquerades at Ranelagh are

represented in Fielding's “Amelia” as dangerous to morals,

and the “Connoisseur” satirises their Eve-like beauties with

caustic humour.

and the illuminated saloons and groves of Vauxhall. * These, and many others, bear testimony to the growing spirit of national jollity during a considerable part of the eighteenth century. How few now remain, “the sad historians of the pensive tale,” of their bygone merriments!

* “The extreme beauty and elegance of this place is well

known to almost every one of my readers; and happy is it for

me that it is so, since to give an adequate idea of it would

exceed my power of description. To delineate the particular

beauties of these gardens would indeed require as much

pains, and as much paper too, as to rehearse all the good

actions of their master; whose life proves the truth of an

observation which I have read in some other writer, that a

truly elegant taste is generally accompanied with an

excellency of heart; or in other words, that true virtue is

indeed nothing else but true taste.” Amelia, b. ix. c. ix.

The Genius of Mirth never hit upon a happier subject than the humours of Cockneyland. “Man made the town and a pretty sample it is of the maker! Behind or before the counter, at home and abroad, the man of business or the beau, the Cockney is the same whimsical original, baffling imitation, and keeping description in full cry. See him sally forth on a fine Sunday to inhale his weekly mouthful of fresh air, * the world all before him, where to choose occupying his meditations, till he finds himself elevated on High-gate Hill or Hampstead Heath. From those magnificent summits he beholds in panorama, woods, valleys, lofty trees, and stately turrets, not forgetting that glorious cupola dedicated to the metropolitan saint, which points out the locality where, six days out of the seven, his orisons are paid to a deity not contemplated by the apostle.

* Moorfields, Pimlico Path, and the Exchange, were the

fashionable parades of the citizens in the days of Elizabeth

and James I.

He lays himself out for enjoyment, and seeks good entertainment for man and (if mounted, or in his cruelty-van) for horse. Having taken possession of a window that commands the best prospect, the waiter is summoned, the larder called over, the ceremony of lunch commenced, and, with that habitual foresight which marks his character, the all-important meal that is to follow, duly catered for. The interval for rural adventure arrives; he takes a stroll; the modest heath-bell and the violet turn up their dark blue eyes to him; and he finds blackberries enough (as Falstaff's men did linen!) on every hedge. Dinner served up, and to his mind, he warms and waxes cosey, jokes with the waiter, talks anything, and to anybody,

Drinks a glass

To his favourite lass!”

pleased with himself, and willing to please. If his phraseology provoke a laugh, he puts it to the account of his smart sayings, and is loudest in the chorus; for when the ball of ridicule is flying about, he ups with his racket and strikes it off to his neighbour.

He is the worst mortal in the world to be put out of his way. The slightest inconvenience, the most trifling departure from his wonted habits, he magnifies into a serious evil. His well-stocked larder and cheerful fireside are ever present to his view: beef and pudding have taken fast hold of him; and, in default of these, his spirits flag; he is hipped and melancholy. Foreign travel exhibits him in his natural light; his peculiarities break forth with whimsical effect, which, though not always the most amiable, are nevertheless entertaining. He longs to see the world; and having with due ceremony arranged his wardrobe, put money in his purse, and procured his passport to strange lands, he sets forward, buttoned up in his native consequence, to the capital of the grand monarque, to rattle dice, and drink champagne. His expectations are not the most reasonable. Without considering the different manners and customs of foreign parts, he bends to nobody, yet takes it as an affront if everybody bend not to him! His baggage is subjected to rigorous search. The infernal parlez-vous!—nothing like this ever happens in old England! His passport is inspected, and his person identified. The inquisitors!—to take the length and breadth of a man, his complexion and calling! The barriers are closed, and he must bivouac in the Diligence the live-long night. Monstrous tyranny! Every rogue enjoys free ingress and egress in a land of liberty! He calls for the bill of fare, the “carte,” and in his selection puts the cart before the horse! Of course there is a horrible conspiracy to poison him! The wines, too, are sophisticated. The champagne is gooseberry; the Burgundy, Pontac; and the vin ordinaire neither better nor worse than a dose of “Braithwait's Intermediate.” The houses are dirty and dark; the streets muddy and gay; the madames and mademoiselles pretty well, I thank'e; and the Mounseers a pack of chattering mountebanks, stuck over with little bits of red ribbon, and blinded with snuff and whiskers! Even the air is too thin: he misses his London smoke! And but one drunken dog has he encountered (and he was his countryman!) to bring to fond remembrance the land we live in! * What wonder, then, if he sigh for luxurious bachelorship in a Brighton boarding-house? Beds made, dinner provided, the cook scolded by proxy, and all the agreeable etceteras incidental to good living set before him, without the annoyance of idle servants, and the trouble of ordering, leaving him to the delightful abandonment of every care, save that of feasting and pleasure-taking!

* Beware of those who are homeless by choice. Show me the

man who cares no more for one place than another, and I will

show you in the same person one who loves nothing but

himself. Home and its attachments are dear to the ingenuous

mind—to cherish their remembrance is the surest proof of a

noble spirit.

With moderate gastronomical and soporific powers, he may manage to eat, drink, and sleep out three guineas a-week; for the sea is a rare provocative to feeding and repose. Besides, a Brighton boarding-house is a change both of air and condition; bachelors become Benedicks, and widows wives, for three guineas a-week, more or less! It furnishes an extensive assortment of acquaintance, such as nowhere else can be found domiciled under the same roof. Each finds it necessary to make himself and herself agreeable. Pride, mauvaise honte, modesty? that keep people apart in general society, all give way. The inmates are like one family; and when they break up for the season, 'tis often in pairs!

“Uncle Timothy to a T! Pardon me, sir, but he must have sat to you for the portrait. If you unbutton his native consequence a little, and throw a jocular light over his whim-whams and caprices, the likeness would be perfect.”

This was addressed to us by a lively, well-to-do-in-the-world-looking little gentleman, who lolled in an arm-chair opposite to an adjoining window, taking things in an easy pick-tooth way, and coquetting with a pint of old port.

“The picture, sir, that you are pleased to identify is not an individual, but a species,—a slight off-hand sketch, taken from general observation.”

“Indeed! That's odd.”

“Even so.”

“Never knew Uncle Tim was like all the world. Would, for all the world's sake, that all the world were like Uncle Tim!”

“A worthy character.”

“Sir, he holds in his heart all the four honours,—Truth, Honesty, Affection, and Benevolence,—in the great game of humanity, and plays not for lucre, but love! I fear you think me strangely familiar,—impertinent too, perhaps. But that portrait, so graphical and complete, was a spell as powerful as Odin's to break silence. Besides, I detest your exclusives,—sentimentalising! soliloquising!—Their shirt-collars, affectedly turned down, puts my choler up! Give me the human face divine, the busy haunts of men, the full tide of human existence.”

The little gentleman translated the “full tide” into a full glass to our good healths and better acquaintance, at the same time drawing his chair nearer, and presenting a handsomely embossed card, on which was inscribed, in delicate Italian calligraphy, “Mr. Benjamin Bosky, Dry-salter, Little Britain.”

Drysalter,—he looked like a thirsty soul!

“Pleasant prospect from this window; you may count every steeple in London. There's the 'tall bully,'—how gloriously his flaming top-knot glistens in the setting sun! Wouldn't give a fig for the best view in the world, if it didn't take in the dome of St. Paul's! Beshrew the Vandal architect that cut down those beautiful elms.—

'The rogue the gallows as his fate foresees,

And bears the like antipathy to trees,'

and run up the wigwam pavilions, the Tom-foolery baby-houses, the run mad, shabby-genteel, I-would-if-I-could-but-I-can't cottages ornée—ornée?—horney!—the cows popping in their heads at the parlour windows, frightening the portly proprietors from their propriety and port!”

It was clear that Mr. Bosky was not to be so frightened; for he drew another draught on his pint decanter, though sitting beneath the umbrage of a huge pair of antlers that were fixed against the wall, under which innumerable Johnny New-comes had been sworn, according to ancient custom, at the Horns at Highgate. It was equally clear, too, that Mr. Bosky himself might have sat for the portrait that he had so kindly appropriated to Uncle Timothy.

A fine manly voice without was heard to troll with joyous melody,—

“The lark, that tirra-lirra chants,—

With hey! with hey! the thrush and the jay,

Are summer songs for me and my aunts,

While we lie tumbling in the hay.”

“Uncle Tim! Uncle Tim!” shouted the mercurial little Drysalter, and up he started as if he had been galvanised, scampered out of the room, made but one leap from the top of the stairs to the bottom, descended à plomb, was up again before we had recovered from our surprise, and introduced a middle-aged, rosy-faced gentleman, “more fat than bard beseems,” with a perforating eye and a most satirical nose. “Uncle Timothy, gentlemen.—A friend or two, (if I may presume to call them so,) Uncle Timothy, that I have fallen in with most unexpectedly and agreeably.”

There is a certain “I no not like thee, Doctor Fell,” feeling, and an “I do,” that have rarely deceived us. With the latter, the satirical-nosed gentleman inspired us at first sight. There was the humorist, with a dash of the antiquary, heightened with a legible expression that nature sometimes stamps on her higher order of intelligences. What a companion, we thought, for “Round about our coal fire” on a winter's evening, or, “Under the green-wood tree” on a summer's clay!

We were all soon very good company; and half a dozen tea-totallers, who had called for a pint of ale and six glasses, having discussed their long division and departed, we had the room to ourselves.

“Know you, Uncle Timothy,” cried Mr. Bosky, with a serio-comic air, “that the law against vagabonds and sturdy beggars is in full force, seeing that you carol in broad daylight, and on the King's highway, a loose catch appertaining to one of the most graceless of their fraternity?”

“Beggars! varlet! I beg nothing of thee but silence, which is gold, if speech be silver. * Is there aught unseemly in my henting the stile with the merry Autolycus? Vagabonds! The order is both ancient and honourable. Collect they not tribute for the crown? Take heed, Benjamin, lest thine be scored on! Are they not solicitors as old as Adam?”

* A precept of the Koran.

“And thieves too, from Mercury downwards, Uncle Timothy.”

“Conveyancers, sirrah! sworn under the Horns never to beg when they can steal. Better lose my purse than my patience. Thou, scapegrace! rob best me of my patience, and beggest nought but the question.”

“Were not the beggars once a jovial crew, sir?” addressing ourselves to the middle-aged gentleman with the satirical nose.

“Right merry! Gentlemen—

'Sweeter than honey

Is other men's money.'

“The joys of to-day were never marred by the cares of to-morrow; for to-morrow was left to take care of itself; and its sun seldom went down upon disappointment. The beggar, * though his pockets be so low, that you might dance a jig in one of them without breaking your shins against a halfpenny; while from the other you might be puzzled to extract as much coin as would pay turnpike for a walking-stick, sings with a light heart; his fingers no less light! playing administrators to the farmer's poultry, and the good housewife's sheets that whiten every hedge!

* “Cast our nabs and cares away,—

This is Beggars' Holiday;

In the world look out and see

Who's so happy a king as he?

At the crowning of our king,

Thus we ever dance and sing.

Where's the nation lives so free

And so merry as do we?

Be it peace, or be it war,

Here at liberty we are.

Hang all Harmanbccks! we cry,

And the Cuffinquiers, too, by.

We enjoy our ease and rest,

To the fields we are not press'd;

When the subsidy's increas'd,

We are not a penny cost;

Nor are we called into town

To be troubled with a gown;

Nor will any go to law

With a beggar for a straw.

All which happiness he brags

He doth owe unto his rags!”

Of all the mad rascals that belong to this fraternity, the

Abraham-Man is the most fantastic. He calls himself by

the name of Poor Tom, and, coming near to any one, cries

out “Poor Tom's a-cold!” Some are exceedingly merry, and do

nothing but sing songs, fashioned out of their own brains;

some will dance; others will do nothing but laugh or weep;

others are dogged, and so sullen, both in look and speech,

that, spying but small company in a house, they boldly

enter, compelling the servants, through fear, to give them

what they demand, which is commonly something that will

yield ready money. The “Upright Man” (who in ancient times

was, next to the king and those “o' th' blood,” in dignity,)

is not a more terrible enemy to the farmer's poultry than

Poor Tom.

How finely has Shakspeare spiritualized this strange

character in the part of Edgar in King Lear!

The middle aisle of old St. Paul's was a great resort for

beggars.

“In Paul's Church, by a pillar,

Sometimes ye have me stand, sir,

With a writ that shews

What care and woes

I pass by sea and land, sir.

With a seeming bursten belly,

I look like one half dead, sir,

Or else I beg With a wooden leg,

And with a night-cap on my head, sir.”

Blind Beggars Song.