Title: An Antarctic Mystery

Author: Jules Verne

Translator: Frances Cashel Hoey

Release date: November 1, 2003 [eBook #10339]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/10339

Credits: Norman Wolcott

[ Redactor’s Note: An Antarctic Mystery (Number V046 in the T&M numerical listing of Verne’s works) is a translation of Le Sphinx de Glaces (1897) translated by Mrs. Cashel Hoey who also translated other Verne works.]

BY

TRANSLATED BY MRS. CASHEL HOEY

![[Illustration]](images/colophon.jpg)

ILLUSTRATED

1899

No doubt the following narrative will be received with entire incredulity, but I think it well that the public should be put in possession of the facts narrated in “An Antarctic Mystery.” The public is free to believe them or not, at its good pleasure.

No more appropriate scene for the wonderful and terrible adventures which I am about to relate could be imagined than the Desolation Islands, so called, in 1779, by Captain Cook. I lived there for several weeks, and I can affirm, on the evidence of my own eyes and my own experience, that the famous English explorer and navigator was happily inspired when he gave the islands that significant name.

Geographical nomenclature, however, insists on the name of Kerguelen, which is generally adopted for the group which lies in 49° 45ʹ south latitude, and 69° 6ʹ east longitude. This is just, because in 1772, Baron Kerguelen, a Frenchman, was the first to discover those islands in the southern part of the Indian Ocean. Indeed, the commander of the squadron on that voyage believed that he had found a new continent on the limit of the Antarctic seas, but in the course of a second expedition he recognized his error. There was only an archipelago. I may be believed when I assert that Desolation Islands is the only suitable name for this group of three hundred isles or islets in the midst of the vast expanse of ocean, which is constantly disturbed by austral storms.

Nevertheless, the group is inhabited, and the number of Europeans and Americans who formed the nucleus of the Kerguelen population at the date of the 2nd of August, 1839, had been augmented for two months past by a unit in my person. Just then I was waiting for an opportunity of leaving the place, having completed the geological and mineralogical studies which had brought me to the group in general and to Christmas Harbour in particular.

Christmas Harbour belongs to the most important islet of the archipelago, one that is about half as large as Corsica. It is safe, and easy, and free of access. Your ship may ride securely at single anchor in its waters, while the bay remains free from ice.

The Kerguelens possess hundreds of other fjords. Their coasts are notched and ragged, especially in the parts between the north and the south-east, where little islets abound. The soil, of volcanic origin, is composed of quartz, mixed with a bluish stone. In summer it is covered with green mosses, grey lichens, various hardy plants, especially wild saxifrage. Only one edible plant grows there, a kind of cabbage, not found anywhere else, and very bitter of flavour. Great flocks of royal and other penguins people these islets, finding good lodging on their rocky and mossy surface. These stupid birds, in their yellow and white feathers, with their heads thrown back and their wings like the sleeves of a monastic habit, look, at a distance, like monks in single file walking in procession along the beach.

The islands afford refuge to numbers of sea-calves, seals, and sea-elephants. The taking of those amphibious animals either on land or from the sea is profitable, and may lead to a trade which will bring a large number of vessels into these waters.

On the day already mentioned, I was accosted while strolling on the port by mine host of mine inn.

“Unless I am much mistaken, time is beginning to seem very long to you, Mr. Jeorling?”

The speaker was a big tall American who kept the only inn on the port.

“If you will not be offended, Mr. Atkins, I will acknowledge that I do find it long.”

“Of course I won’t be offended. Am I not as well used to answers of that kind as the rocks of the Cape to the rollers?”

“And you resist them equally well.”

“Of course. From the day of your arrival at Christmas Harbour, when you came to the Green Cormorant, I said to myself that in a fortnight, if not in a week, you would have enough of it, and would be sorry you had landed in the Kerguelens.”

“No, indeed, Mr. Atkins; I never regret anything I have done.”

“That’s a good habit, sir.”

“Besides, I have gained knowledge by observing curious things here. I have crossed the rolling plains, covered with hard stringy mosses, and I shall take away curious mineralogical and geological specimens with me. I have gone sealing, and taken sea-calves with your people. I have visited the rookeries where the penguin and the albatross live together in good fellowship, and that was well worth my while. You have given me now and again a dish of petrel, seasoned by your own hand, and very acceptable when one has a fine healthy appetite. I have found a friendly welcome at the Green Cormorant, and I am very much obliged to you. But, if I am right in my reckoning, it is two months since the Chilian two-master Peñas set me down at Christmas Harbour in mid-winter.

“And you want to get back to your own country, which is mine, Mr. Jeorling; to return to Connecticut, to Providence, our capital.”

“Doubtless, Mr. Atkins, for I have been a globe-trotter for close upon three years. One must come to a stop and take root at some time.”

“Yes, and when one has taken root, one puts out branches.”

“Just so, Mr. Atkins. However, as I have no relations living, it is likely that I shall be the last of my line. I am not likely to take a fancy for marrying at forty.”

“Well, well, that is a matter of taste. Fifteen years ago I settled down comfortably at Christmas Harbour with my Betsy; she has presented me with ten children, who in their turn will present me with grandchildren.”

“You will not return to the old country?”

“What should I do there, Mr. Jeorling, and what could I ever have done there? There was nothing before me but poverty. Here, on the contrary, in these Islands of Desolation, where I have no reason to feel desolate, ease and competence have come to me and mine!”

“No doubt, and I congratulate you, Mr. Atkins, for you are a happy man. Nevertheless it is not impossible that the fancy may take you some day—”

Mr. Atkins answered by a vigorous and convincing shake of the head. It was very pleasant to hear this worthy American talk. He was completely acclimatized on his archipelago, and to the conditions of life there. He lived with his family as the penguins lived in their rookeries. His wife was a “valiant” woman of the Scriptural type, his sons were strong, hardy fellows, who did not know what sickness meant. His business was prosperous. The Green Cormorant had the custom of all the ships, whalers and others, that put in at Kerguelen. Atkins supplied them with everything they required, and no second inn existed at Christmas Harbour. His sons were carpenters, sailmakers, and fishers, and they hunted the amphibians in all the creeks during the hot season. In short, this was a family of honest folk who fulfilled their destiny without much difficulty.

“Once more, Mr. Atkins, let me assure you,” I resumed, “I am delighted to have come to Kerguelen. I shall always remember the islands kindly. Nevertheless, I should not be sorry to find myself at sea again.”

“Come, Mr. Jeorling, you must have a little patience,” said the philosopher, “you must not forget that the fine days will soon be here. In five or six weeks—”

“Yes, and in the meantime, the hills and the plains, the rocks and the shores will be covered thick with snow, and the sun will not have strength to dispel the mists on the horizon.”

“Now, there you are again, Mr. Jeorling! Why, the wild grass is already peeping through the white sheet! Just look!”

“Yes, with a magnifying glass! Between ourselves, Atkins, could you venture to pretend that your bays are not still ice-locked in this month of August, which is the February of our northern hemisphere?”

“I acknowledge that, Mr. Jeorling. But again I say have patience! The winter has been mild this year. The ships will soon show up, in the east or in the west, for the fishing season is near.”

“May Heaven hear you, Atkins, and guide the Halbrane safely into port.”

“Captain Len Guy? Ah, he’s a good sailor, although he’s English—there are good people everywhere—and he takes in his supplies at the Green Cormorant.”

“You think the Halbrane—”

“Will be signalled before a week, Mr. Jeorling, or, if not, it will be because there is no longer a Captain Len Guy; and if there is no longer a Captain Len Guy, it is because the Halbrane has sunk in full sail between the Kerguelens and the Cape of Good Hope.”

Thereupon Mr. Atkins walked away, with a scornful gesture, indicating that such an eventuality was out of all probability.

My intention was to take my passage on board the Halbrane so soon as she should come to her moorings in Christmas Harbour. After a rest of six or seven days, she would set sail again for Tristan d’Acunha, where she was to discharge her cargo of tin and copper. I meant to stay in the island for a few weeks of the fine season, and from thence set out for Connecticut. Nevertheless, I did not fail to take into due account the share that belongs to chance in human affairs, for it is wise, as Edgar Poe has said, always “to reckon with the unforeseen, the unexpected, the inconceivable, which have a very large share (in those affairs), and chance ought always to be a matter of strict calculation.”

Each day I walked about the port and its neighbourhood. The sun was growing strong. The rocks were emerging by degrees from their winter clothing of snow; moss of a wine-like colour was springing up on the basalt cliffs, strips of seaweed fifty yards long were floating on the sea, and on the plain the lyella, which is of Andean origin, was pushing up its little points, and the only leguminous plant of the region, that gigantic cabbage already mentioned, valuable for its anti-scorbutic properties, was making its appearance.

I had not come across a single land mammal—sea mammals swarm in these waters—not even of the batrachian or reptilian kinds. A few insects only—butterflies or others—and even these did not fly, for before they could use their wings, the atmospheric currents carried the tiny bodies away to the surface of the rolling waves.

“And the Halbrane?” I used to say to Atkins each morning.

“The Halbrane, Mr. Jeorling,” he would reply with complacent assurance, “will surely come into port to-day, or, if not to-day, to-morrow.”

In my rambles on the shore, I frequently routed a crowd of amphibians, sending them plunging into the newly-released waters. The penguins, heavy and impassive creatures, did not disappear at my approach; they took no notice; but the black petrels, the puffins, black and white, the grebes and others, spread their wings at sight of me.

One day I witnessed the departure of an albatross, saluted by the very best croaks of the penguins, no doubt as a friend whom they were to see no more. Those powerful birds can fly for two hundred leagues without resting for a moment, and with such rapidity that they sweep through vast spaces in a few hours. The departing albatross sat motionless upon a high rock, at the end of the bay of Christmas Harbour, looking at the waves as they dashed violently against the beach.

Suddenly, the bird rose with a great sweep into the air, its claws folded beneath it, its head stretched out like the prow of a ship, uttering its shrill cry: a few moments later it was reduced to a black speck in the vast height and disappeared behind the misty curtain of the south.

The Halbrane was a schooner of three hundred tons, and a fast sailer. On board there was a captain, a mate, or lieutenant, a boatswain, a cook, and eight sailors; in all twelve men, a sufficient number to work the ship. Solidly built, copper-bottomed, very manageable, well suited for navigation between the fortieth and sixtieth parallels of south latitude, the Halbrane was a credit to the ship-yards of Birkenhead.

All this I learned from Atkins, who adorned his narrative with praise and admiration of its theme. Captain Len Guy, of Liverpool, was three-fifths owner of the vessel, which he had commanded for nearly six years. He traded in the southern seas of Africa and America, going from one group of islands to another and from continent to continent. His ship’s company was but a dozen men, it is true, but she was used for the purposes of trade only; he would have required a more numerous crew, and all the implements, for taking seals and other amphibia. The Halbrane was not defenceless, however; on the contrary, she was heavily armed, and this was well, for those southern seas were not too safe; they were frequented at that period by pirates, and on approaching the isles the Halbrane was put into a condition to resist attack. Besides, the men always slept with one eye open.

One morning—it was the 27th of August—I was roused out of my bed by the rough voice of the innkeeper and the tremendous thumps he gave my door.

“Mr. Jeorling, are you awake?”

“Of course I am, Atkins. How should I be otherwise, with all that noise going on? What’s up?”

“A ship six miles out in the offing, to the nor’east, steering for Christmas!”

“Will it be the Halbrane?”

“We shall know that in a short time, Mr. Jeorling. At any rate it is the first boat of the year, and we must give it a welcome.”

I dressed hurriedly and joined Atkins on the quay, where I found him in the midst of a group engaged in eager discussion. Atkins was indisputably the most considerable and considered man in the archipelago—consequently he secured the best listeners. The matter in dispute was whether the schooner in sight was or was not the Halbrane. The majority maintained that she was not, but Atkins was positive she was, although on this occasion he had only two backers.

The dispute was carried on with warmth, the host of the Green Cormorant defending his view, and the dissentients maintaining that the fast-approaching schooner was either English or American, until she was near enough to hoist her flag and the Union Jack went fluttering up into the sky. Shortly after the Halbrane lay at anchor in the middle of Christmas Harbour.

The captain of the Halbrane, who received the demonstrative greeting of Atkins very coolly, it seemed to me, was about forty-five, red-faced, and solidly built, like his schooner; his head was large, his hair was already turning grey, his black eyes shone like coals of fire under his thick eyebrows, and his strong white teeth were set like rocks in his powerful jaws; his chin was lengthened by a coarse red beard, and his arms and legs were strong and firm. Such was Captain Len Guy, and he impressed me with the notion that he was rather impassive than hard, a shut-up sort of person, whose secrets it would not be easy to get at. I was told the very same day that my impression was correct, by a person who was better informed than Atkins, although the latter pretended to great intimacy with the captain. The truth was that nobody had penetrated that reserved nature.

I may as well say at once that the person to whom I have alluded was the boatswain of the Halbrane, a man named Hurliguerly, who came from the Isle of Wight. This person was about forty-four, short, stout, strong, and bow-legged; his arms stuck out from his body, his head was set like a ball on a bull neck, his chest was broad enough to hold two pairs of lungs (and he seemed to want a double supply, for he was always puffing, blowing, and talking), he had droll roguish eyes, with a network of wrinkles under them. A noteworthy detail was an ear-ring, one only, which hung from the lobe of his left ear. What a contrast to the captain of the schooner, and how did two such dissimilar beings contrive to get on together? They had contrived it, somehow, for they had been at sea in each other’s company for fifteen years, first in the brig Power, which had been replaced by the schooner Halbrane, six years before the beginning of this story.

Atkins had told Hurliguerly on his arrival that I would take passage on the Halbrane, if Captain Len Guy consented to my doing so, and the boatswain presented himself on the following morning without any notice or introduction. He already knew my name, and he accosted me as follows:

“Mr. Jeorling, I salute you.”

“I salute you in my turn, my friend. What do you want?”

“To offer you my services.”

“On what account?”

“On account of your intention to embark on the Halbrane.”

“Who are you?”

“I am Hurliguerly, the boatswain of the Halbrane, and besides, I am the faithful companion of Captain Len Guy, who will listen to me willingly, although he has the reputation of not listening to anybody.”

“Well, my friend, let us talk, if you are not required on board just now.”

“I have two hours before me, Mr. Jeorling. Besides, there’s very little to be done to-day. If you are free, as I am—”

He waved his hand towards the port.

“Cannot we talk very well here?” I observed.

“Talk, Mr. Jeorling, talk standing up, and our throats dry, when it is so easy to sit down in a corner of the Green Cormorant in front of two glasses of whisky.”

“I don’t drink.”

“Well, then, I’ll drink for both of us. Oh! don’t imagine you are dealing with a sot! No! never more than is good for me, but always as much!”

I followed the man to the tavern, and while Atkins was busy on the deck of the ship, discussing the prices of his purchases and sales, we took our places in the eating-room of his inn. And first I said to Hurliguerly: “It was on Atkins that I reckoned to introduce me to Captain Len Guy, for he knows him very intimately, if I am not mistaken.”

“Pooh! Atkins is a good sort, and the captain has an esteem for him. But he can’t do what I can. Let me act for you, Mr. Jeorling.”

“Is it so difficult a matter to arrange, boatswain, and is there not a cabin on board the Halbrane? The smallest would do for me, and I will pay—”

“All right, Mr. Jeorling! There is a cabin, which has never been used, and since you don’t mind putting your hand in your pocket if required—however—between ourselves—it will take somebody sharper than you think, and who isn’t good old Atkins, to induce Captain Len Guy to take a passenger. Yes, indeed, it will take all the smartness of the good fellow who now drinks to your health, regretting that you don’t return the compliment!”

What a wink it was that accompanied this sentiment! And then the man took a short black pipe out of the pocket of his jacket, and smoked like a steamer in full blast.

“Mr. Hurliguerly?” said I.

“Mr. Jeorling.”

“Why does your captain object to taking me on his ship?”

“Because he does not intend to take anybody on board his ship. He never has taken a passenger.”

“But, for what reason, I ask you.”

“Oh! because he wants to go where he likes, to turn about if he pleases and go the other way without accounting for his motives to anybody. He never leaves these southern seas, Mr. Jeorling; we have been going these many years between Australia on the east and America on the west; from Hobart Town to the Kerguelens, to Tristan d’Acunha, to the Falklands, only taking time anywhere to sell our cargo, and sometimes dipping down into the Antarctic Sea. Under these circumstances, you understand, a passenger might be troublesome, and besides, who would care to embark on the Halbrane? she does not like to flout the breezes, and goes wherever the wind drives her.”

“The Halbrane positively leaves the Kerguelens in four days?”

“Certainly.”

“And this time she will sail westward for Tristan d’Acunha?”

“Probably.”

“Well, then, that probability will be enough for me, and since you offer me your services, get Captain Len Guy to accept me as a passenger.”

“It’s as good as done.”

“All right, Hurliguerly, and you shall have no reason to repent of it.”

“Eh! Mr. Jeorling,” replied this singular mariner, shaking his head as though he had just come out of the sea, “I have never repented of anything, and I know well that I shall not repent of doing you a service. Now, if you will allow me, I shall take leave of you, without waiting for Atkins to return, and get on board.”

With this, Hurliguerly swallowed his last glass of whisky at a gulp—I thought the glass would have gone down with the liquor—bestowed a patronizing smile on me, and departed.

An hour later, I met the innkeeper on the port, and told him what had occurred.

“Ah! that Hurliguerly!” said he, “always the old story. If you were to believe him, Captain Len Guy wouldn’t blow his nose without consulting him. He’s a queer fellow, Mr. Jeorling, not bad, not stupid, but a great hand at getting hold of dollars or guineas! If you fall into his hands, mind your purse, button up your pocket, and don’t let yourself be done.”

“Thanks for your advice, Atkins. Tell me, you have been talking with Captain Len Guy; have you spoken about me?”

“Not yet, Mr. Jeorling. There’s plenty of time. The Halbrane has only just arrived, and—”

“Yes, yes, I know. But you understand that I want to be certain as soon as possible.”

“There’s nothing to fear. The matter will be all right. Besides, you would not be at a loss in any case. When the fishing season comes, there will be more ships in Christmas Harbour than there are houses around the Green Cormorant. Rely on me. I undertake your getting a passage.”

Now, these were fair words, but, just as in the case of Hurliguerly, there was nothing in them. So, notwithstanding the fine promises of the two, I resolved to address myself personally to Len Guy, hard to get at though he might be, so soon as I should meet him alone.

The next day, in the afternoon, I saw him on the quay, and approached him. It was plain that he would have preferred to avoid me. It was impossible that Captain Len Guy, who knew every dweller in the place, should not have known that I was a stranger, even supposing that neither of my would-be patrons had mentioned me to him.

His attitude could only signify one of two things—either my proposal had been communicated to him, and he did not intend to accede to it; or neither Hurliguerly nor Atkins had spoken to him since the previous day. In the latter case, if he held aloof from me, it was because of his morose nature; it was because he did not choose to enter into conversation with a stranger.

At the moment when I was about to accost him, the Halbrane’s lieutenant rejoined his captain, and the latter availed himself of the opportunity to avoid me. He made a sign to the officer to follow him, and the two walked away at a rapid pace.

“This is serious,” said I to myself. “It looks as though I shall find it difficult to gain my point. But, after all it only means delay. To-morrow morning I will go on board the Halbrane. Whether he likes it or whether he doesn’t, this Len Guy will have to hear what I’ve got to say, and to give me an answer, yes or no!”

Besides, the captain of the Halbrane might come at dinner-time to the Green Cormorant, where the ship’s people usually took their meals when ashore. So I waited, and did not go to dinner until late. I was disappointed, however, for neither the captain nor anyone belonging to the ship patronized the Green Cormorant that day. I had to dine alone, exactly as I had been doing every day for two months.

After dinner, about half-past seven, when it was dark, I went out to walk on the port, keeping on the side of the houses. The quay was quite deserted; not a man of the Halbrane’s crew was ashore. The ship’s boats were alongside, rocking gently on the rising tide. I remained there until nine, walking up and down the edge in full view of the Halbrane. Gradually the mass of the ship became indistinct, there was no movement and no light. I returned to the inn, where I found Atkins smoking his pipe near the door.

“Atkins,” said I, “it seems that Captain Len Guy does not care to come to your inn very often?”

“He sometimes comes on Sunday, and this is Saturday, Mr. Jeorling.”

“You have not spoken to him?”

“Yes, I have.”

Atkins was visibly embarrassed.

“You have informed him that a person of your acquaintance wished to take passage on the Halbrane?”

“Yes.”

“What was his answer?”

“Not what either you or I would have wished, Mr. Jeorling.”

“He refuses?”

“Well, yes, I suppose it was refusing; what he said was: ‘My ship is not intended to carry passengers. I never have taken any, and I never intend to do so.’”

I slept ill. Again and again I “dreamed that I was dreaming.” Now—this is an observation made by Edgar Poe—when one suspects that one is dreaming, the waking comes almost instantly. I woke then, and every time in a very bad humour with Captain Len Guy. The idea of leaving the Kerguelens on the Halbrane had full possession of me, and I grew more and more angry with her disobliging captain. In fact, I passed the night in a fever of indignation, and only recovered my temper with daylight. Nevertheless I was determined to have an explanation with Captain Len Guy about his detestable conduct. Perhaps I should fail to get anything out of that human hedgehog, but at least I should have given him a piece of my mind.

I went out at eight o’clock in the morning. The weather was abominable. Rain, mixed with snow, a storm coming over the mountains at the back of the bay from the west, clouds scurrying down from the lower zones, an avalanche of wind and water. It was not likely that Captain Len Guy had come ashore merely to enjoy such a wetting and blowing.

No one on the quay; of course not. As for my getting on board the Halbrane, that could not be done without hailing one of her boats, and the boatswain would not venture to send it for me.

“Besides,” I reflected, “on his quarter-deck the captain is at home, and neutral ground is better for what I want to say to him, if he persists in his unjustifiable refusal. I will watch him this time, and if his boat touches the quay, he shall not succeed in avoiding me.”

I returned to the Green Cormorant, and took up my post behind the window panes, which were dimmed by the hissing rain. There I waited, nervous, impatient, and in a state of growing irritation. Two hours wore away thus. Then, with the instability of the winds in the Kerguelens, the weather became calm before I did. I opened my window, and at the same moment a sailor stepped into one of the boats of the Halbrane and laid hold of a pair of oars, while a second man seated himself in the back, but without taking the tiller ropes. The boat touched the landing-place and Captain Len Guy stepped on shore.

In a few seconds I was out of the inn, and confronted him.

“Sir,” said I in a cold hard tone.

Captain Len Guy looked at me steadily, and I was struck by the sadness of his eyes, which were as black as ink. Then in a very low voice he asked:

“You are a stranger?”

“A stranger at the Kerguelens? Yes.”

“Of English nationality?”

“No. American.”

He saluted me, and I returned the curt gesture.

“Sir,” I resumed, “I believe Mr. Atkins of the Green Cormorant has spoken to you respecting a proposal of mine. That proposal, it seems to me, deserved a favourable reception on the part of a—”

“The proposal to take passage on my ship?” interposed Captain Len Guy.

“Precisely.”

“I regret, sir, I regret that I could not agree to your request.”

“Will you tell me why?”

“Because I am not in the habit of taking passengers. That is the first reason.”

“And the second, captain?”

“Because the route of the Halbrane is never settled beforehand. She starts for one port and goes to another, just as I find it to my advantage. You must know that I am not in the service of a shipowner. My share in the schooner is considerable, and I have no one but myself to consult in respect to her.”

“Then it entirely depends on you to give me a passage?”

“That is so, but I can only answer you by a refusal—to my extreme regret.”

“Perhaps you will change your mind, captain, when you know that I care very little what the destination of your schooner may be. It is not unreasonable to suppose that she will go somewhere—”

“Somewhere indeed.” I fancied that Captain Len Guy threw a long look towards the southern horizon.

“To go here or to go there is almost a matter of indifference to me. What I desired above all was to get away from Kerguelen at the first opportunity that should offer.”

Captain Len Guy made me no answer; he remained in silent thought, but did not endeavour to slip away from me.

“You are doing me the honour to listen to me?” I asked him sharply.

“Yes, sir.”

“I will then add that, if I am not mistaken, and if the route of your ship has not been altered, it was your intention to leave Christmas Harbour for Tristan d’Acunha.”

“Perhaps for Tristan d’Acunha, perhaps for the Cape, perhaps for the Falklands, perhaps for elsewhere.”

“Well, then, Captain Guy, it is precisely elsewhere that I want to go,” I replied ironically, and trying hard to control my irritation.

Then a singular change took place in the demeanour of Captain Len Guy. His voice became more sharp and harsh. In very plain words he made me understand that it was quite useless to insist, that our interview had already lasted too long, that time pressed, and he had business at the port; in short that we had said all that we could have to say to each other.

I had put out my arm to detain him—to seize him would be a more correct term—and the conversation, ill begun, seemed likely to end still more ill, when this odd person turned towards me and said in a milder tone,—

“Pray understand, sir, that I am very sorry to be unable to do what you ask, and to appear disobliging to an American. But I could not act otherwise. In the course of the voyage of the Halbrane some unforeseen incident might occur to make the presence of a passenger inconvenient—even one so accommodating as yourself. Thus I might expose myself to the risk of being unable to profit by the chances which I seek.”

“I have told you, captain, and I repeat it, that although my intention is to return to America and to Connecticut, I don’t care whether I get there in three months or in six, or by what route; it’s all the same to me, and even were your schooner to take me to the Antarctic seas—”

“The Antarctic seas!” exclaimed Captain Len Guy, with a question in his tone. And his look searched my thoughts with the keenness of a dagger.

“Why do you speak of the Antarctic seas?” he asked, taking my hand.

“Well, just as I might have spoken of the ‘Hyperborean seas’ from whence an Irish poet has made Sebastian Cabot address some lovely verses to his Lady.(1) I spoke of the South Pole as I might have spoken of the North.”

Captain Len Guy did not answer, and I thought I saw tears glisten in his eyes. Then, as though he would escape from some harrowing recollection which my words had evoked, he said,—

“Who would venture to seek the South Pole?”

“It would be difficult to reach, and the experiments would be of no practical use,” I replied. “Nevertheless there are men sufficiently adventurous to embark in such an enterprise.”

“Yes—adventurous is the word!” muttered the captain.

“And now,” I resumed, “the United States is again making an attempt with Wilkes’s fleet, the Vancouver, the Peacock, the Flying Fish, and others.”

“The United States, Mr. Jeorling? Do you mean to say that an expedition has been sent by the Federal Government to the Antarctic seas?”

“The fact is certain, and last year, before I left America, I learned that the vessels had sailed. That was a year ago, and it is very possible that Wilkes has gone farther than any of the preceding explorers.”

Captain Len Guy had relapsed into silence, and came out of his inexplicable musing only to say abruptly,—

“You come from Connecticut, sir?”

“From Connecticut.”

“And more specially?”

“From Providence.”

“Do you know Nantucket Island?”

“I have visited it several times.”

“You know, I think,” said the captain, looking straight into my eyes, “that Nantucket Island was the birthplace of Arthur Gordon Pym, the hero of your famous romance-writer Edgar Poe.”

“Yes. I remember that Poe’s romance starts from Nantucket.”

“Romance, you say? That was the word you used?”

“Undoubtedly, captain.”

“Yes, and that is what everybody says! But, pardon me, I cannot stay any longer. I regret that I cannot alter my mind with respect to your proposal. But, at any rate, you will only have a few days to wait. The season is about to open. Trading ships and whalers will put in at Christmas Harbour, and you will be able to make a choice, with the certainty of going to the port you want to reach. I am very sorry, sir, and I salute you.”

With these words Captain Len Guy walked quickly away, and the interview ended differently from what I had expected, that is to say in formal, although polite, fashion.

As there is no use in contending with the impossible, I gave up the hope of a passage on the Halbrane, but continued to feel angry with her intractable captain. And why should I not confess that my curiosity was aroused? I felt that there was something mysterious about this sullen mariner, and I should have liked to find out what it was.

That day, Atkins wanted to know whether Captain Len Guy had made himself less disagreeable. I had to acknowledge that I had been no more fortunate in my negotiations than my host himself, and the avowal surprised him not a little. He could not understand the captain’s obstinate refusal. And—a fact which touched him more nearly—the Green Cormorant had not been visited by either Len Guy or his crew since the arrival of the Halbrane. The men were evidently acting upon orders. So far as Hurliguerly was concerned, it was easy to understand that after his imprudent advance he did not care to keep up useless relations with me. I knew not whether he had attempted to shake the resolution of his chief; but I was certain of one thing; if he had made any such effort it had failed.

During the three following days, the 10th, 11th, and 12th of August, the work of repairing and re-victualling the schooner went on briskly; but all this was done with regularity, and without such noise and quarrelling as seamen at anchor usually indulge in. The Halbrane was evidently well commanded, her crew well kept in hand, discipline strictly maintained.

The schooner was to sail on the 15th of August, and on the eve of that day I had no reason to think that Captain Len Guy had repented him of his categorical refusal. Indeed, I had made up my mind to the disappointment, and had no longer any angry feeling about it. When Captain Len Guy and myself met on the quay, we took no notice of each other; nevertheless, I fancied there was some hesitation in his manner; as though he would have liked to speak to me. He did not do so, however, and I was not disposed to seek a further explanation.

At seven o’clock in the evening of the 14th of August, the island being already wrapped in darkness, I was walking on the port after I had dined, walking briskly too, for it was cold, although dry weather. The sky was studded with stars and the air was very keen. I could not stay out long, and was returning to mine inn, when a man crossed my path, paused, came back, and stopped in front of me. It was the captain of the Halbrane.

“Mr. Jeorling,” he began, “the Halbrane sails to-morrow morning, with the ebb tide.”

“What is the good of telling me that,” I replied, “since you refuse—”

“Sir, I have thought over it, and if you have not changed your mind, come on board at seven o’clock.”

“Really, captain,” I replied, “I did not expect this relenting on your part.”

“I repeat that I have thought over it, and I add that the Halbrane shall proceed direct to Tristan d’Acunha. That will suit you, I suppose?”

“To perfection, captain. To-morrow morning, at seven o’clock, I shall be on board.”

“Your cabin is prepared.”

“The cost of the voyage—”

“We can settle that another time,” answered the captain, “and to your satisfaction. Until to-morrow, then—”

“Until to-morrow.”

I stretched out my arm, to shake hands with him upon our bargain. Perhaps he did not perceive my movement in the darkness, at all events he made no response to it, but walked rapidly away and got into his boat.

I was greatly surprised, and so was Atkins, when I found him in the eating-room of the Green Cormorant and told him what had occurred. His comment upon it was characteristic.

“This queer captain,” he said, “is as full of whims as a spoilt child! It is to be hoped he will not change his mind again at the last moment.”

The next morning at daybreak I bade adieu to the Green Cormorant, and went down to the port, with my kind-hearted host, who insisted on accompanying me to the ship, partly in order to make his mind easy respecting the sincerity of the captain’s repentance, and partly that he might take leave of him, and also of Hurliguerly. A boat was waiting at the quay, and we reached the ship in a few minutes.

The first person whom I met on the deck was Hurliguerly; he gave me a look of triumph, which said as plainly as speech: “Ha! you see now. Our hard-to-manage captain has given in at last. And to whom do you owe this, but to the good boatswain who did his best for you, and did not boast overmuch of his influence?”

Was this the truth? I had strong reasons for doubting it. After all, what did it matter?

Captain Len Guy came on deck immediately after my arrival; this was not surprising, except for the fact that he did not appear to remark my presence.

Atkins then approached the captain and said in a pleasant tone,—

“We shall meet next year!”

“If it please God, Atkins.”

They shook hands. Then the boatswain took a hearty leave of the innkeeper, and was rowed back to the quay.

Before dark the white summits of Table Mount and Havergal, which rise, the former to two, the other to three thousand feet above the level of the sea, had disappeared from our view.

(1) Thomas D’Arcy McGee. (J.V.)

Never did a voyage begin more prosperously, or a passenger start in better spirits. The interior of the Halbrane corresponded with its exterior. Nothing could exceed the perfect order, the Dutch cleanliness of the vessel. The captain’s cabin, and that of the lieutenant, one on the port, the other on the starboard side, were fitted up with a narrow berth, a cupboard anything but capacious, an arm-chair, a fixed table, a lamp hung from the ceiling, various nautical instruments, a barometer, a thermometer, a chronometer, and a sextant in its oaken box. One of the two other cabins was prepared to receive me. It was eight feet in length, five in breadth. I was accustomed to the exigencies of sea life, and could do with its narrow proportions, also with its furniture—a table, a cupboard, a cane-bottomed arm-chair, a washing-stand on an iron pedestal, and a berth to which a less accommodating passenger would doubtless have objected. The passage would be a short one, however, so I took possession of that cabin, which I was to occupy for only four, or at the worst five weeks, with entire content.

The eight men who composed the crew were named respectively Martin Holt, sailing-master; Hardy, Rogers, Drap, Francis, Gratian, Burg, and Stern—sailors all between twenty-five and thirty-five years old—all Englishmen, well trained, and remarkably well disciplined by a hand of iron.

Let me set it down here at the beginning, the exceptionally able man whom they all obeyed at a word, a gesture, was not the captain of the Halbrane; that man was the second officer, James West, who was then thirty-two years of age.

James West was born on the sea, and had passed his childhood on board a lighter belonging to his father, and on which the whole family lived. All his life he had breathed the salt air of the English Channel, the Atlantic, or the Pacific. He never went ashore except for the needs of his service, whether of the State or of trade. If he had to leave one ship for another he merely shifted his canvas bag to the latter, from which he stirred no more. When he was not sailing in reality he was sailing in imagination. After having been ship’s boy, novice, sailor, he became quartermaster, master, and finally lieutenant of the Halbrane, and he had already served for ten years as second in command under Captain Len Guy.

James West was not even ambitious of a higher rise; he did not want to make a fortune; he did not concern himself with the buying or selling of cargoes; but everything connected with that admirable instrument a sailing ship, James West understood to perfection.

The personal appearance of the lieutenant was as follows: middle height, slightly built, all nerves and muscles, strong limbs as agile as those of a gymnast, the true sailor’s “look,” but of very unusual far-sightedness and surprising penetration, sunburnt face, hair thick and short, beardless cheeks and chin, regular features, the whole expression denoting energy, courage, and physical strength at their utmost tension.

James West spoke but rarely—only when he was questioned. He gave his orders in a clear voice, not repeating them, but so as to be heard at once, and he was understood. I call attention to this typical officer of the Merchant Marine, who was devoted body and soul to Captain Len Guy as to the schooner Halbrane. He seemed to be one of the essential organs of his ship, and if the Halbrane had a heart it was in James West’s breast that it beat.

There is but one more person to be mentioned; the ship’s cook—a negro from the African coast named Endicott, thirty years of age, who had held that post for eight years. The boatswain and he were great friends, and indulged in frequent talks.

Life on board was very regular, very simple, and its monotony was not without a certain charm. Sailing is repose in movement, a rocking in a dream, and I did not dislike my isolation. Of course I should have liked to find out why Captain Len Guy had changed his mind with respect to me; but how was this to be done? To question the lieutenant would have been loss of time. Besides, was he in possession of the secrets of his chief? It was no part of his business to be so, and I had observed that he did not occupy himself with anything outside of it. Not ten words were exchanged between him and me during the two meals which we took in common daily. I must acknowledge, however, that I frequently caught the captain’s eyes fixed upon me, as though he longed to question me, as though he had something to learn from me, whereas it was I, on the contrary, who had something to learn from him. But we were both silent.

Had I felt the need of talking to somebody very strongly, I might have resorted to the boatswain, who was always disposed to chatter; but what had he to say that could interest me? He never failed to bid me good morning and good evening in most prolix fashion, but beyond these courtesies I did not feel disposed to go.

The good weather lasted, and on the 18th of August, in the afternoon, the look-out discerned the mountains of the Crozet group. The next day we passed Possession Island, which is inhabited only in the fishing season. At this period the only dwellers there are flocks of penguins, and the birds which whalers call “white pigeons.”

The approach to land is always interesting at sea. It occurred to me that Captain Len Guy might take this opportunity of speaking to his passenger; but he did not.

We should see land, that is to say the peaks of Marion and Prince Edward Islands, before arriving at Tristan d’Acunha, but it was there the Halbrane was to take in a fresh supply of water. I concluded therefore that the monotony of our voyage would continue unbroken to the end. But, on the morning of the 20th of August, to my extreme surprise, Captain Len Guy came on deck, approached me, and said, speaking very low,—

“Sir, I have something to say to you.”

“I am ready to hear you, captain.”

“I have not spoken until to-day, for I am naturally taciturn.” Here he hesitated again, but after a pause, continued with an effort,—

“Mr. Jeorling, have you tried to discover my reason for changing my mind on the subject of your passage?”

“I have tried, but I have not succeeded, captain. Perhaps, as I am not a compatriot of yours, you—”

“It is precisely because you are an American that I decided in the end to offer you a passage on the Halbrane.”

“Because I am an American?”

“Also, because you come from Connecticut.”

“I don’t understand.”

“You will understand if I add that I thought it possible, since you belong to Connecticut, since you have visited Nantucket Island, that you might have known the family of Arthur Gordon Pym.”

“The hero of Edgar Poe’s romance?”

“The same. His narrative was founded upon the manuscript in which the details of that extraordinary and disastrous voyage across the Antarctic Sea was related.”

I thought I must be dreaming when I heard Captain Len Guy’s words. Edgar Poe’s romance was nothing but a fiction, a work of imagination by the most brilliant of our American writers. And here was a sane man treating that fiction as a reality.

I could not answer him. I was asking myself what manner of man was this one with whom I had to deal.

“You have heard my question?” persisted the captain.

“Yes, yes, captain, certainly, but I am not sure that I quite understand.”

“I will put it to you more plainly. I ask you whether in Connecticut you personally knew the Pym family who lived in Nantucket Island? Arthur Pym’s father was one of the principal merchants there, he was a Navy contractor. It was his son who embarked in the adventures which he related with his own lips to Edgar Poe—”

“Captain! Why, that story is due to the powerful imagination of our great poet. It is a pure invention.”

“So, then, you don’t believe it, Mr. Jeorling?” said the captain, shrugging his shoulders three times.

“Neither I nor any other person believes it, Captain Guy, and you are the first I have heard maintain that it was anything but a mere romance.”

“Listen to me, then, Mr. Jeorling, for although this ‘romance’—as you call it—appeared only last year, it is none the less a reality. Although eleven years have elapsed since the facts occurred, they are none the less true, and we still await the ‘word’ of an enigma which will perhaps never be solved.”

Yes, he was mad; but by good fortune West was there to take his place as commander of the schooner. I had only to listen to him, and as I had read Poe’s romance over and over again, I was curious to hear what the captain had to say about it.

“And now,” he resumed in a sharper tone and with a shake in his voice which denoted a certain amount of nervous irritation, “it is possible that you did not know the Pym family, that you have never met them either at Providence or at Nantucket—”

“Or elsewhere.”

“Just so! But don’t commit yourself by asserting that the Pym family never existed, that Arthur Gordon is only a fictitious personage, and his voyage an imaginary one! Do you think any man, even your Edgar Poe, could have been capable of inventing, of creating—?”

The increasing vehemence of Captain Len Guy warned me of the necessity of treating his monomania with respect, and accepting all he said without discussion.

“Now,” he proceeded, “please to keep the facts which I am about to state clearly in your mind; there is no disputing about facts. You may deduce any results from them you like. I hope you will not make me regret that I consented to give you a passage on the Halbrane.”

This was an effectual warning, so I made a sign of acquiescence. The matter promised to be curious. He went on,—

“When Edgar Poe’s narrative appeared in 1838, I was at New York. I immediately started for Baltimore, where the writer’s family lived; the grandfather had served as quarter-master-general during the War of Independence. You admit, I suppose, the existence of the Poe family, although you deny that of the Pym family?”

I said nothing, and the captain continued, with a dark glance at me,—

“I inquired into certain matters relating to Edgar Poe. His abode was pointed out to me and I called at the house. A first disappointment! He had left America, and I could not see him. Unfortunately, being unable to see Edgar Poe, I was unable to refer to Arthur Gordon Pym in the case. That bold pioneer of the Antarctic regions was dead! As the American poet had stated, at the close of the narrative of his adventures, Gordon’s death had already been made known to the public by the daily press.”

What Captain Len Guy said was true; but, in common with all the readers of the romance, I had taken this declaration for an artifice of the novelist. My notion was that, as he either could not or dared not wind up so extraordinary a work of imagination, Poe had given it to be understood that he had not received the last three chapters from Arthur Pym, whose life had ended under sudden and deplorable circumstances which Poe did not make known.

“Then,” continued the captain, “Edgar Poe being absent, Arthur Pym being dead, I had only one thing to do; to find the man who had been the fellow-traveller of Arthur Pym, that Dirk Peters who had followed him to the very verge of the high latitudes, and whence they had both returned—how? This is not known. Did they come back in company? The narrative does not say, and there are obscure points in that part of it, as in many other places. However, Edgar Poe stated explicitly that Dirk Peters would be able to furnish information relating to the non-communicated chapters, and that he lived at Illinois. I set out at once for Illinois; I arrived at Springfield; I inquired for this man, a half-breed Indian. He lived in the hamlet of Vandalia; I went there, and met with a second disappointment. He was not there, or rather, Mr. Jeorling, he was no longer there. Some years before this Dirk Peters had left Illinois, and even the United States, to go—nobody knows where. But I have talked, at Vandalia with people who had known him, with whom he lived, to whom he related his adventures, but did not explain the final issue. Of that he alone holds the secret.”

What! This Dirk Peters had really existed? He still lived? I was on the point of letting myself be carried away by the statements of the captain of the Halbrane! Yes, another moment, and, in my turn, I should have made a fool of myself. This poor mad fellow imagined that he had gone to Illinois and seen people at Vandalia who had known Dirk Peters, and that the latter had disappeared. No wonder, since he had never existed, save in the brain of the novelist!

Nevertheless I did not want to vex Len Guy, and perhaps drive him still more mad. Accordingly I appeared entirely convinced that he was speaking words of sober seriousness, even when he added,—

“You are aware that in the narrative mention is made by the captain of the schooner on which Arthur Pym had embarked, of a bottle containing a sealed letter, which was deposited at the foot of one of the Kerguelen peaks?”

“Yes, I recall the incident.”

“Well, then, in one of my latest voyages I sought for the place where that bottle ought to be. I found it and the letter also. That letter stated that the captain and Arthur Pym intended to make every effort to reach the uttermost limits of the Antarctic Sea!”

“You found that bottle?”

“Yes!”

“And the letter?”

“Yes!”

I looked at Captain Len Guy. Like certain monomaniacs he had come to believe in his own inventions. I was on the point of saying to him, “Show me that letter,” but I thought better of it. Was he not capable of having written the letter himself? And then I answered,—

“It is much to be regretted, captain, that you were unable to come across Dirk Peters at Vandalia! He would at least have informed you under what conditions he and Arthur Pym returned from so far. Recollect, now, in the last chapter but one they are both there. Their boat is in front of the thick curtain of white mist; it dashes into the gulf of the cataract just at the moment when a veiled human form rises. Then there is nothing more; nothing but two blank lines—”

“Decidedly, sir, it is much to be regretted that I could not lay my hand on Dirk Peters! It would have been interesting to learn what was the outcome of these adventures. But, to my mind, it would have been still more interesting to have ascertained the fate of the others.”

“The others?” I exclaimed almost involuntarily. “Of whom do you speak?”

“Of the captain and crew of the English schooner which picked up Arthur Pym and Dirk Peters after the frightful shipwreck of the Grampus, and brought them across the Polar Sea to Tsalal Island—”

“Captain,” said I, just as though I entertained no doubt of the authenticity of Edgar Poe’s romance, “is it not the case that all these men perished, some in the attack on the schooner, the others by the infernal device of the natives of Tsalal?”

“Who can tell?” replied the captain in a voice hoarse from emotion. “Who can say but that some of the unfortunate creatures survived, and contrived to escape from the natives?”

“In any case,” I replied, “it would be difficult to admit that those who had survived could still be living.”

“And why?”

“Because the facts we are discussing are eleven years old.”

“Sir,” replied the captain, “since Arthur Pym and Dirk Peters were able to advance beyond Tsalal Island farther than the eighty-third parallel, since they found means of living in the midst of those Antarctic lands, why should not their companions, if they were not all killed by the natives, if they were so fortunate as to reach the neighbouring islands sighted during the voyage—why should not those unfortunate countrymen of mine have contrived to live there? Why should they not still be there, awaiting their deliverance?”

“Your pity leads you astray, captain,” I replied. “It would be impossible.”

“Impossible, sir! And if a fact, on indisputable evidence, appealed to the whole civilized world; if a material proof of the existence of these unhappy men, imprisoned at the ends of the earth, were furnished, who would venture to meet those who would fain go to their aid with the cry of ‘Impossible!’”

Was it a sentiment of humanity, exaggerated to the point of madness, that had roused the interest of this strange man in those shipwrecked folk who never had suffered shipwreck, for the good reason that they never had existed?

Captain Len Guy approached me anew, laid his hand on my shoulder and whispered in my ear,—

“No, sir, no! the last word has not been said concerning the crew of the Jane.”

Then he promptly withdrew.

The Jane was, in Edgar Poe’s romance, the name of the ship which had rescued Arthur Pym and Dirk Peters from the wreck of the Grampus, and Captain Len Guy had now uttered it for the first time. It occurred to me then that Guy was the name of the captain of the Jane, an English ship; but what of that? The captain of the Jane never lived but in the imagination of the novelist, he and the skipper of the Halbrane have nothing in common except a name which is frequently to be found in England. But, on thinking of the similarity, it struck me that the poor captain’s brain had been turned by this very thing. He had conceived the notion that he was of kin to the unfortunate captain of the Jane! And this had brought him to his present state, this was the source of his passionate pity for the fate of the imaginary shipwrecked mariners!

It would have been interesting to discover whether James West was aware of the state of the case, whether his chief had ever talked to him of the follies he had revealed to me. But this was a delicate question, since it involved the mental condition of Captain Len Guy; and besides, any kind of conversation with the lieutenant was difficult. On the whole I thought it safer to restrain my curiosity. In a few days the schooner would reach Tristan d’Acunha, and I should part with her and her captain for good and all. Never, however, could I lose the recollection that I had actually met and sailed with a man who took the fictions of Edgar Poe’s romance for sober fact. Never could I have looked for such an experience!

On the 22nd of August the outline of Prince Edward’s Island was sighted, south latitude 46° 55ʹ, and 37° 46ʹ east longitude. We were in sight of the island for twelve hours, and then it was lost in the evening mists.

On the following day the Halbrane headed in the direction of the north-west, towards the most northern parallel of the southern hemisphere which she had to attain in the course of that voyage.

In this chapter I have to give a brief summary of Edgar Poe’s romance, which was published at Richmond under the title of

THE ADVENTURES OF ARTHUR GORDON PYM.

We shall see whether there was any room for doubt that the adventures of this hero of romance were imaginary. But indeed, among the multitude of Poe’s readers, was there ever one, with the sole exception of Len Guy, who believed them to be real? The story is told by the principal personage. Arthur Pym states in the preface that on his return from his voyage to the Antarctic seas he met, among the Virginian gentlemen who took an interest in geographical discoveries, Edgar Poe, who was then editor of the Southern Literary Messenger at Richmond, and that he authorized the latter to publish the first part of his adventures in that journal “under the cloak of fiction.” That portion having been favourably received, a volume containing the complete narrative was issued with the signature of Edgar Poe.

Arthur Gordon Pym was born at Nantucket, where he attended the Bedford School until he was sixteen years old. Having left that school for Mr. Ronald’s, he formed a friendship with one Augustus Barnard, the son of a ship’s captain. This youth, who was eighteen, had already accompanied his father on a whaling expedition in the southern seas, and his yarns concerning that maritime adventure fired the imagination of Arthur Pym. Thus it was that the association of these youths gave rise to Pym’s irresistible vocation to adventurous voyaging, and to the instinct that especially attracted him towards the high zones of the Antarctic region. The first exploit of Augustus Barnard and Arthur Pym was an excursion on board a little sloop, the Ariel, a two-decked boat which belonged to the Pyms. One evening the two youths, both being very tipsy, embarked secretly, in cold October weather, and boldly set sail in a strong breeze from the south-west. The Ariel, aided by the ebb tide, had already lost sight of land when a violent storm arose. The imprudent young fellows were still intoxicated. No one was at the helm, not a reef was in the sail. The masts were carried away by the furious gusts, and the wreck was driven before the wind. Then came a great ship which passed over the Ariel as the Ariel would have passed over a floating feather.

Arthur Pym gives the fullest details of the rescue of his companion and himself after this collision, under conditions of extreme difficulty. At length, thanks to the second officer of the Penguin, from New London, which arrived on the scene of the catastrophe, the comrades were picked up, with life all but extinct, and taken back to Nantucket.

This adventure, to which I cannot deny an appearance of veracity, was an ingenious preparation for the chapters that were to follow, and indeed, up to the day on which Pym penetrates into the polar circle, the narrative might conceivably be regarded as authentic. But, beyond the polar circle, above the austral icebergs, it is quite another thing, and, if the author’s work be not one of pure imagination, I am—well, of any other nationality than my own. Let us get on.

Their first adventure had not cooled the two youths, and eight months after the affair of the Ariel—June, 1827—the brig Grampus was fitted out by the house of Lloyd and Vredenburg for whaling in the southern seas. This brig was an old, ill-repaired craft, and Mr. Barnard, the father of Augustus, was its skipper. His son, who was to accompany him on the voyage, strongly urged Arthur to go with him, and the latter would have asked nothing better, but he knew that his family, and especially his mother, would never consent to let him go.

This obstacle, however, could not stop a youth not much given to submit to the wishes of his parents. His head was full of the entreaties and persuasion of his companion, and he determined to embark secretly on the Grampus, for Mr. Barnard would not have authorized him to defy the prohibition of his family. He announced that he had been invited to pass a few days with a friend at New Bedford, took leave of his parents and left his home. Forty-eight hours before the brig was to sail, he slipped on board unperceived, and got into a hiding-place which had been prepared for him unknown alike to Mr. Barnard and the crew.

The cabin occupied by Augustus communicated by a trap-door with the hold of the Grampus, which was crowded with barrels, bales, and the innumerable components of a cargo. Through the trap-door Arthur Pym reached his hiding-place, which was a huge wooden chest with a sliding side to it. This chest contained a mattress, blankets, a jar of water, ship’s biscuit, smoked sausage, a roast quarter of mutton, a few bottles of cordials and liqueurs, and also writing-materials. Arthur Pym, supplied with a lantern, candles, and tinder, remained three days and nights in his retreat. Augustus Barnard had not been able to visit him until just before the Grampus set sail.

An hour later, Arthur Pym began to feel the rolling and pitching of the brig. He was very uncomfortable in the chest, so he got out of it, and in the dark, while holding on by a rope which was stretched across the hold to the trap of his friend’s cabin, he was violently sea-sick in the midst of the chaos. Then he crept back into his chest, ate, and fell asleep.

Several days elapsed without the reappearance of Augustus Barnard. Either he had not been able to get down into the hold again, or he had not ventured to do so, fearing to betray the presence of Arthur Pym, and thinking the moment for confessing everything to his father had not yet come.

Arthur Pym, meanwhile, was beginning to suffer from the hot and vitiated atmosphere of the hold. Terrible nightmares troubled his sleep. He was conscious of raving, and in vain sought some place amid the mass of cargo where he might breathe a little more easily. In one of these fits of delirium he imagined that he was gripped in the claws of an African lion,(1) and in a paroxysm of terror he was about to betray himself by screaming, when he lost consciousness.

The fact is that he was not dreaming at all. It was not a lion that Arthur Pym felt crouching upon his chest, it was his own dog, Tiger, a young Newfoundland. The animal had been smuggled on board by Augustus Barnard unperceived by anybody—(this, at least, is an unlikely occurrence). At the moment of Arthur’s coming out of his swoon the faithful Tiger was licking his face and hands with lavish affection.

Now the prisoner had a companion. Unfortunately, the said companion had drunk the contents of the water jar while Arthur was unconscious, and when Arthur Pym felt thirsty, he discovered that there was “not a drop to drink!” His lantern had gone out during his prolonged faint; he could not find the candles and the tinder-box, and he then resolved to rejoin Augustus Barnard at all hazards. He came out of the chest, and although faint from inanition and trembling with weakness, he felt his way in the direction of the trap-door by means of the rope. But, while he was approaching, one of the bales of cargo, shifted by the rolling of the ship, fell down and blocked up the passage. With immense but quite useless exertion he contrived to get over this obstacle, but when he reached the trap-door under Augustus Barnard’s cabin he failed to raise it, and on slipping the blade of his knife through one of the joints he found that a heavy mass of iron was placed upon the trap, as though it were intended to condemn him beyond hope. He had to renounce his attempt and drag himself back towards the chest, on which he fell, exhausted, while Tiger covered him with caresses.

The master and the dog were desperately thirsty, and when Arthur stretched out his hand, he found Tiger lying on his back, with his paws up and his hair on end. He then felt Tiger all over, and his hand encountered a string passed round the dog’s body. A strip of paper was fastened to the string under his left shoulder.

Arthur Pym had reached the last stage of weakness. Intelligence was almost extinct. However, after several fruitless attempts to procure a light, he succeeded in rubbing the paper with a little phosphorus—(the details given in Edgar Poe’s narrative are curiously minute at this point)—and then by the glimmer that lasted less than a second he discerned just seven words at the end of a sentence. Terrifying words these were: blood—remain hidden—life depends on it.

What did these words mean? Let us consider the situation of Arthur Pym, at the bottom of the ship’s hold, between the boards of a chest, without light, without water, with only ardent liquor to quench his thirst! And this warning to remain hidden, preceded by the word “blood”—that supreme word, king of words, so full of mystery, of suffering, of terror! Had there been strife on board the Grampus? Had the brig been attacked by pirates? Had the crew mutinied? How long had this state of things lasted?

It might be thought that the marvellous poet had exhausted the resources of his imagination in the terror of such a situation; but it was not so. There is more to come!

Arthur Pym lay stretched upon his mattress, incapable of thought, in a sort of lethargy; suddenly he became aware of a singular sound, a kind of continuous whistling breathing. It was Tiger, panting, Tiger with eyes that glared in the midst of the darkness, Tiger with gnashing teeth—Tiger gone mad. Another moment and the dog had sprung upon Arthur Pym, who, wound up to the highest pitch of horror, recovered sufficient strength to ward off his fangs, and wrapping around him a blanket which Tiger had torn with his white teeth, he slipped out of the chest, and shut the sliding side upon the snapping and struggling brute.

Arthur Pym contrived to slip through the stowage of the hold, but his head swam, and, falling against a bale, he let his knife drop from his hand.

Just as he felt himself breathing his last sigh he heard his name pronounced, and a bottle of water was held to his lips. He swallowed the whole of its contents, and experienced the most exquisite of pleasures.

A few minutes later, Augustus Barnard, seated with his comrade in a corner of the hold, told him all that had occurred on board the brig.

Up to this point, I repeat, the story is admissible, but we have not yet come to the events which “surpass all probability by their marvellousness.”

The crew of the Grampus numbered thirty-six men, including the Barnards, father and son. After the brig had put to sea on the 20th of June, Augustus Barnard had made several attempts to rejoin Arthur Pym in his hiding-place, but in vain. On the third day a mutiny broke out on board, headed by the ship’s cook, a negro like our Endicott; but he, let me say at once, would never have thought of heading a mutiny.

Numerous incidents are related in the romance—the massacre of most of the sailors who remained faithful to Captain Barnard, then the turning adrift of the captain and four of those men in a small whaler’s boat when the ship was abreast of the Bermudas. These unfortunate persons were never heard of again.

Augustus Barnard would not have been spared, but for the intervention of the sailing-master of the Grampus. This sailing-master was a half-breed named Dirk Peters, and was the person whom Captain Len Guy had gone to look for in Illinois!

The Grampus then took a south-east course under the command of the mate, who intended to pursue the occupation of piracy in the southern seas.

These events having taken place, Augustus Barnard would again have joined Arthur Pym, but he had been shut up in the forecastle in irons, and told by the ship’s cook that he would not be allowed to come out until “the brig should be no longer a brig.” Nevertheless, a few days afterwards, Augustus contrived to get rid of his fetters, to cut through the thin partition between him and the hold, and, followed by Tiger, he tried to reach his friend’s hiding-place. He could not succeed, but the dog had scented Arthur Pym, and this suggested to Augustus the idea of fastening a note to Tiger’s neck bearing the words:

“I scrawl this with blood—remain hidden—your life depends on it—”

This note, as we have already learned, Arthur Pym had received. Just as he had arrived at the last extremity of distress his friend reached him.

Augustus added that discord reigned among the mutineers. Some wanted to take the Grampus towards the Cape Verde Islands; others, and Dirk Peters was of this number, were bent on sailing to the Pacific Isles.

Tiger was not mad. He was only suffering from terrible thirst, and soon recovered when it was relieved.

The cargo of the Grampus was so badly stowed away that Arthur Pym was in constant danger from the shifting of the bales, and Augustus, at all risks, helped him to remove to a corner of the ‘tween decks.

The half-breed continued to be very friendly with the son of Captain Barnard, so that the latter began to consider whether the sailing-master might not be counted on in an attempt to regain possession of the ship.

They were just thirty days out from Nantucket when, on the 4th of July, an angry dispute arose among the mutineers about a little brig signalled in the offing, which some of them wanted to take and others would have allowed to escape. In this quarrel a sailor belonging to the cook’s party, to which Dirk Peters had attached himself, was mortally injured. There were now only thirteen men on board, counting Arthur Pym.

Under these circumstances a terrible storm arose, and the Grampus was mercilessly knocked about. This storm raged until the 9th of July, and on that day, Dirk Peters having manifested an intention of getting rid of the mate, Augustus Barnard readily assured him of his assistance, without, however, revealing the fact of Arthur Pym’s presence on board. Next day, one of the cook’s adherents, a man named Rogers, died in convulsions, and, beyond all doubt, of poison. Only four of the cook’s party then remained, of these Dirk Peters was one. The mate had five, and would probably end by carrying the day over the cook’s party.

There was not an hour to lose. The half-breed having informed Augustus Barnard that the moment for action had arrived, the latter told him the truth about Arthur Pym.

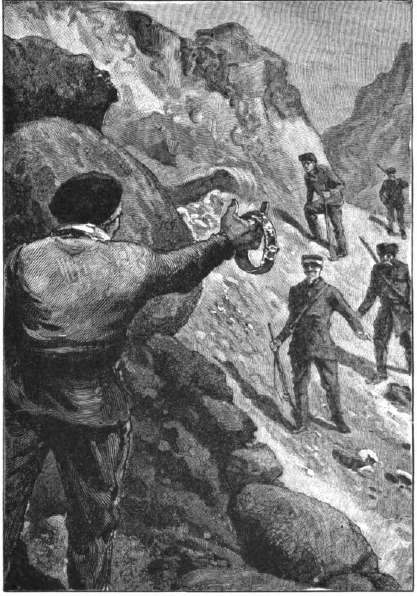

While the two were in consultation upon the means to be employed for regaining possession of the ship, a tempest was raging, and presently a gust of irresistible force struck the Grampus and flung her upon her side, so that on righting herself she shipped a tremendous sea, and there was considerable confusion on board. This offered a favourable opportunity for beginning the struggle, although the mutineers had made peace among themselves. The latter numbered nine men, while the half-breed’s party consisted only of himself, Augustus Barnard and Arthur Pym. The ship’s master possessed only two pistols and a hanger. It was therefore necessary to act with prudence.

Then did Arthur Pym (whose presence on board the mutineers could not suspect) conceive the idea of a trick which had some chance of succeeding. The body of the poisoned sailor was still lying on the deck; he thought it likely, if he were to put on the dead man’s clothes and appear suddenly in the midst of those superstitious sailors, that their terror would place them at the mercy of Dirk Peters. It was still dark when the half-breed went softly towards the ship’s stern, and, exerting his prodigious strength to the utmost, threw himself upon the man at the wheel and flung him over the poop.

Augustus Barnard and Arthur Pym joined him instantly, each armed with a belaying-pin. Leaving Dirk Peters in the place of the steersman, Arthur Pym, so disguised as to present the appearance of the dead man, and his comrade, posted themselves close to the head of the forecastle gangway. The mate, the ship’s cook, all the others were there, some sleeping, the others drinking or talking; guns and pistols were within reach of their hands.

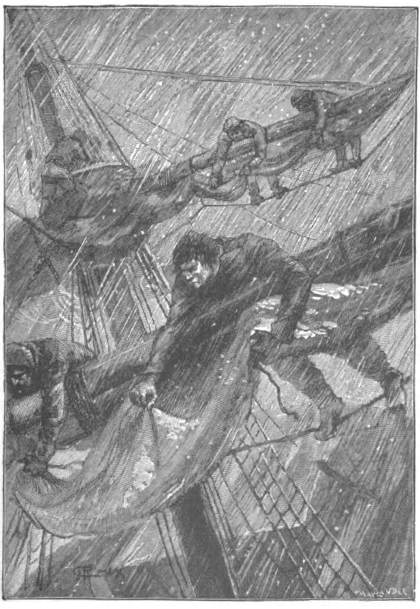

The tempest raged furiously; it was impossible to stand on the deck.

At that moment the mate gave the order for Augustus Barnard and Dirk Peters to be brought to the forecastle. This order was transmitted to the man at the helm, no other than Dirk Peters, who went down, accompanied by Augustus Barnard, and almost simultaneously Arthur Pym made his appearance.

The effect of the apparition was prodigious. The mate, terrified on beholding the resuscitated sailor, sprang up, beat the air with his hands, and fell down dead. Then Dirk Peters rushed upon the others, seconded by Augustus Barnard, Arthur Pym, and the dog Tiger. In a few moments all were strangled or knocked on the head,—save Richard Parker, the sailor, whose life was spared.

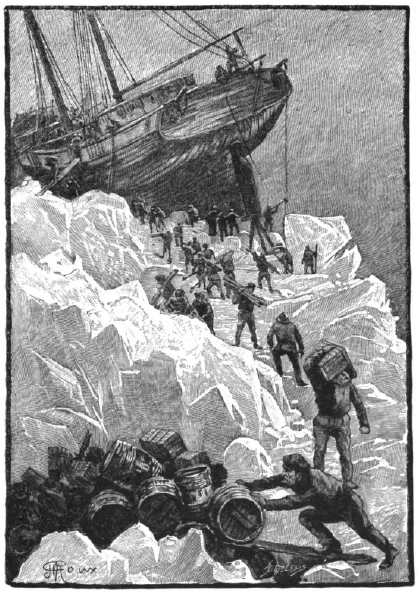

And now, while the tempest was in full force, only four men were left to work the brig, which was labouring terribly with seven feet of water in her hold. They had to cut down the mainmast, and, when morning came, the mizen. That day was truly awful, the night was more awful still! If Dirk Peters and his companions had not lashed themselves securely to the remains of the rigging, they must have been carried away by a tremendous sea, which drove in the hatches of the Grampus.

Then follows in the romance a minute record of the series of incidents ensuing upon this situation, from the 14th of July to the 7th of August; the fishing for victuals in the submerged hold, the coming of a mysterious brig laden with corpses, which poisoned the atmosphere and passed on like a huge coffin, the sport of a wind of death; the torments of hunger and thirst; the impossibility of reaching the provision store; the drawing of lots by straws—the shortest gave Richard Parker to be sacrificed for the life of the other three—the death of that unhappy man, who was killed by Dirk Peters and devoured; lastly, the finding in the hold of a jar of olives and a small turtle.

Owing to the displacement of her cargo the Grampus rolled and pitched more and more. The frightful heat caused the torture of thirst to reach the extreme limit of human endurance, and on the 1st of August, Augustus Barnard died. On the 3rd, the brig foundered in the night, and Arthur Pym and the half-breed, crouching upon the upturned keel, were reduced to feed upon the barnacles with which the bottom was covered, in the midst of a crowd of waiting, watching sharks. Finally, after the shipwrecked mariners of the Grampus had drifted no less than twenty-five degrees towards the south, they were picked up by the schooner Jane, of Liverpool, Captain William Guy.

Evidently, reason is not outraged by an admission of the reality of these facts, although the situations are strained to the utmost limits of possibility; but that does not surprise us, for the writer is the American magician-poet, Edgar Poe. But from this moment onwards we shall see that no semblance of reality exists in the succession of incidents.

Arthur Pym and Dirk Peters were well treated on board the English schooner Jane. In a fortnight, having recovered from the effects of their sufferings, they remembered them no more. With alternations of fine and bad weather the Jane sighted Prince Edward’s Island on the 13th of October, then the Crozet Islands, and afterwards the Kerguelens, which I had left eleven days ago.

Three weeks were employed in chasing sea-calves; these furnished the Jane with a goodly cargo. It was during this time that the captain of the Jane buried the bottle in which his namesake of the Halbrane claimed to have found a letter containing William Guy’s announcement of his intention to visit the austral seas.

On the 12th of November, the schooner left the Kerguelens, and after a brief stay at Tristan d’Acunha she sailed to reconnoitre the Auroras in 35° 15ʹ of south latitude, and 37° 38ʹ of west longitude. But these islands were not to be found, and she did not find them.

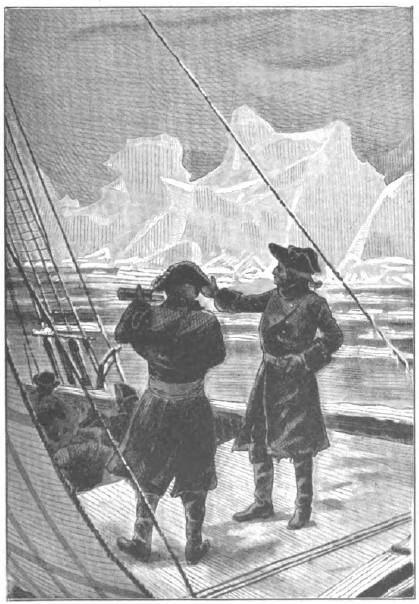

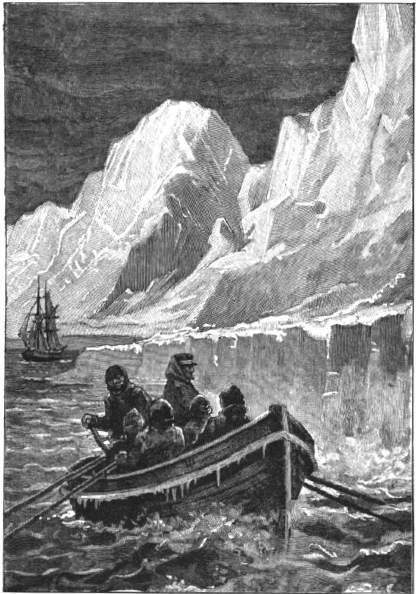

On the 12th of December the Jane headed towards the Antarctic pole. On the 26th, the first icebergs came in sight beyond the seventy-third degree.

From the 1st to the 14th of January, 1828, the movements were difficult, the polar circle was passed in the midst of ice-floes, the icebergs’ point was doubled and the ship sailed on the surface of an open sea—the famous open sea where the temperature is 47° Fahrenheit, and the water is 34°.

Edgar Poe, every one will allow, gives free rein to his fancy at this point. No navigator had ever reached latitudes so high—not even James Weddell of the British Navy, who did not get beyond the seventy-fourth parallel in 1822. But the achievement of the Jane, although difficult of belief, is trifling in comparison with the succeeding incidents which Arthur Pym, or rather Edgar Poe, relates with simple earnestness. In fact he entertained no doubt of reaching the pole itself.

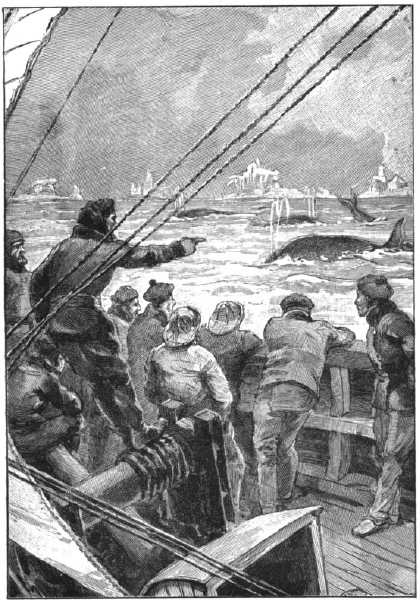

In the first place, not a single iceberg is to be seen on this fantastic sea. Innumerable flocks of birds skim its surface, among them is a pelican which is shot. On a floating piece of ice is a bear of the Arctic species and of gigantic size. At last land is signalled. It is an island of a league in circumference, to which the name of Bennet Islet was given, in honour of the captain’s partner in the ownership of the Jane.