At that moment a board creaked in the corridor.

If I were caught here I should be arrested.

Title: The Powers and Maxine

Author: C. N. Williamson

A. M. Williamson

Illustrator: Frank T. Merrill

Release date: December 1, 2003 [eBook #10410]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/10410

Credits: Suzanne Shell, Gary Toffelmire, Greg Dunham and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

It had come at last, the moment I had been thinking about for days. I was going to have him all to myself, the only person in the world I ever loved.

He had asked me to sit out two dances, and that made me think he really must want to be with me, not just because I’m the “pretty girl’s sister,” but because I’m myself, Lisa Drummond.

Being what I am,—queer, and plain, I can’t bear to think that men like girls for their beauty; yet I can’t help liking men better if they are handsome.

I don’t know if Ivor Dundas is the handsomest man I ever saw, but he seems so to me. I don’t know if he is very good, or really very wonderful, although he’s clever and ambitious enough; but he has a way that makes women fond of him; and men admire him, too. He looks straight into your eyes when he talks to you, as if he cared more for you than anyone else in the world: and if I were an artist, painting a picture of a dark young knight starting off for the crusades, I should ask Ivor Dundas to stand as my model.

Perhaps his expression wouldn’t be exactly right for the pious young crusader, for it isn’t at all saintly, really: still, I have seen just that rapt sort of look on his face. It was generally when he was talking to Di: but I wouldn’t let myself believe that it meant anything in particular. He has the reputation of having made lots of women fall in love with him. This was one of the first things I heard when Di and I came over from America to visit Lord and Lady Mountstuart. And of course there was the story about him and Maxine de Renzie. Everyone was talking of it when we first arrived in London.

My heart beat very fast as I guided him into the room which Lady Mountstuart has given Di and me for our special den. It is separated by another larger room from the ballroom; but both doors were open and we could see people dancing.

I told him he might sit by me on the sofa under Di’s book shelves, because we could talk better there. Usually, I don’t like being in front of a mirror, because—well, because I’m only the “pretty girl’s sister.” But to-night I didn’t mind. My cheeks were red, and my eyes bright. Sitting down, you might almost take me for a tall girl, and the way my gown was made didn’t show that one shoulder is a little higher than the other. Di designed the dress.

I thought, if I wasn’t pretty, I did look interesting, and original. I looked as if I could think of things; and as if I could feel.

And I was feeling. I was wondering why he had been so good to me lately, unless he cared. Of course it might be for Di’s sake; but I am not so queer-looking that no man could ever be fascinated by me.

They say pity is akin to love. Perhaps he had begun by pitying me, because Di has everything and I nothing; and then, afterwards, he had found out that I was intelligent and sympathetic.

He sat by me and didn’t speak at first. Just then Di passed the far-away, open door of the ballroom, dancing with Lord Robert West, the Duke of Glasgow’s brother.

“Thank you so much for the book,” I said.

(He had sent me a book that morning—one he’d heard me say I wanted.)

He didn’t seem to hear, and then he turned suddenly, with one of his nice smiles. I always think he has the nicest smile in the world: and certainly he has the nicest voice. His eyes looked very kind, and a little sad. I willed him hard to love me.

“It made me happy to get it,” I went on.

“It made me happy to send it,” he said.

“Does it please you to do things for me?” I asked.

“Why, of course.”

“You do like poor little me a tiny bit, then?” I couldn’t help adding—“Even though I’m different from other girls?”

“Perhaps more for that reason,” he said, with his voice as kind as his eyes.

“Oh, what shall I do if you go away!” I burst out, partly because I really meant it, and partly because I hoped it might lead him on to say what I wanted so much to hear. “Suppose you get that consulship at Algiers.”

“I hope I may,” he said quickly. “A consulship isn’t a very great thing—but—it’s a beginning. I want it badly.”

“I wish I had some influence with the Foreign Secretary,” said I, not telling him that the man actually dislikes me, and looks at me as if I were a toad. “Of course, he’s Lord Mountstuart’s cousin, and brother-in-law as well, and that makes him seem quite in the family, doesn’t it? But it isn’t as if I were really related to Lady Mountstuart. I was never sorry before that Di and I are only step-sisters—no, not a bit sorry, though her mother had all the money, and brought it to my poor father; but now I wish I were Lady Mountstuart’s niece, and that I had some of the coaxing, ‘girly’ ways Di can put on when she wants to get something out of people. I’d make the Foreign Secretary give you exactly what you wanted, even if it took you far, far from me.”

With that, he looked at me suddenly, and his face grew slowly red, under the brown.

“You are a very kind Imp,” he said. “Imp” is the name he invented for me. I loved to hear him call me by it.

“Kind!” I echoed. “One isn’t kind when one—likes—people.”

I saw by his eyes, then, that he knew. But I didn’t care. If only I could make him say the words I longed to hear—even because he pitied me, because he had found out how I loved him, and because he had really too much of the dark-young-Crusader-knight in him, to break my heart! I made up my mind that I would take him at his word, quickly, if he gave me the chance; and I would tell Di that he was dreadfully in love with me. That would make her writhe.

I kept my eyes on him, and I let them tell him everything. He saw; there was no doubt of that; but he did not say the words I hoped for. A moment or two he was silent; and then, gazing away towards the door of the ballroom, he spoke very gently, as if I had been a child—though I am older than Di by three or four years.

“Thank you, Imp, for letting me see that you are such a staunch little friend,” said he. “Now that I know you really do take an interest in my affairs, I think I may tell you why I want so much to go to Algiers—though very likely you’ve guessed already—you are such an ‘intuitive’ girl. And besides, I haven’t tried very hard to hide my feelings—not as hard as I ought, perhaps, when I realise how little I have to offer to your sister. Now you understand all, don’t you—even if you didn’t before? I love her, and if I go to Algiers—”

“Don’t say any more,” I managed to cut him short. “I can’t bear—I mean, I understand. I—did guess before.”

It was true. I had guessed, but I wouldn’t let myself believe. I hoped against hope. He was so much kinder to me than any other man ever took the trouble to be, in all my wretched, embittered twenty-four years of life.

“Di might have told me,” I went gasping on, rather than let there be a long silence between us just then. I had enough pride not to want him to see me cry—though, if it could have made any difference, I would have grovelled at his feet and wet them with my tears. “But she never does tell me anything about herself.”

“She’s so unselfish and so fond of you, that probably she likes better to talk about you instead,” he defended her. And then I felt that I could hate him, as much as I’ve always hated Di, deep down in my heart. At that minute I should have liked to kill her, and watch his face when he found her lying dead—out of his reach for ever.

“Besides,” he hurried on, “I’ve never asked her yet if she would marry me, because—my prospects weren’t very brilliant. She knows of course that I love her—”

“And if you get the consulship, you’ll put the important question?” I cut him short, trying to be flippant.

“Yes. But I told you tonight, because I—because you were so kind, I felt I should like to have you know.”

Kind! Yes, I had been too kind. But if by putting out my foot I could have crushed every hope of his for the future—every hope, that is, in which my stepsister Diana Forrest had any part—I would have done it, just as I trample on ants in the country sometimes, for the pleasure of feeling that I—even I—have power of life and death.

I swallowed hard, to keep the sobs back. I’m never very strong or well, but now I felt broken, ready to die. I was glad when I heard the music stop in the ballroom.

“There!” I said. “The two dances you asked me to sit out with you are over. I’m sure you’re engaged for the next.”

“Yes, Imp, I am.”

“To Di?”

“No, I have Number 13 with her.”

“Thirteen! Unlucky number.”

“Any number is lucky that gives me a chance with her. The next one, coming now, is with Mrs. George Allendale.”

“Oh, yes, the actor manager’s wife. She goes everywhere; and Lord Mountstuart likes theatrical celebrities. This house ought to be very serious and political, but we have every sort of creature—provided it’s an amusing, or successful, or good-looking one. By the way, used Maxine de Renzie to come here, when she was acting in London at George Allendale’s theatre? That was before Di and I arrived on the scene, you remember.”

“I remember. Oh, yes, she came here. It was in this house I met her first, off the stage, I believe.”

“What a sweet memory! Wasn’t Mrs. George awfully jealous of her husband when he had such a fascinating beauty for his leading lady?”

“I never heard that she was.”

“You needn’t look cross with me. I’m not saying anything against your gorgeous Maxine.”

“Of course not. Nobody could. But you mustn’t call Miss de Renzie ‘my Maxine,’ please, Imp.”

“I beg your pardon,” I said. “You see, I’ve heard other people call her that—in joke. And you dedicated your book about Lhassa, that made you such a famous person, to her, didn’t you?”

“No. What made you think that?” He was really annoyed now, and I was pleased—if anything could please me, in my despair.

“Why, everybody thinks it. It was dedicated to ‘M.R.’ as if the name were a secret, so—”

“‘Everybody’ is very stupid then. ‘M.R.’ is an old lady, my god-mother, who helped me with money for my expedition to Lhassa, otherwise I couldn’t have gone. And she isn’t of the kind that likes to see her name in print. Now, where shall I take you, Imp? Because I must go and look for Mrs. Allendale.”

“I’ll stay where I am, thank you,” I said, “and watch you dance—from far off. That’s my part in life, you know: watching other people dance from far off.”

When he was gone, I leaned back among the cushions, and I wasn’t sure that one of my heart attacks would not come on. I felt horribly alone, and deserted; and though I hate Di, and always have hated her, ever since the tiny child and her mother (a beautiful, rich, young Californian widow) came into my father’s house in New York, she does know how to manage me better than anyone else, when I am in such moods. I could have screamed for her, as I sat there helplessly looking through the open doors: and then, at last, I saw her, as if my wish had been a call which had reached her ears over the music in the ballroom.

She had stopped dancing, and with her partner (Lord Robert, again) entered the room which lay between our “den” and the ballroom, Probably they would have gone on to the conservatory, which can be reached in that way, but I cried her name as loudly as I could, and she heard. Only a moment she paused—long enough to send Lord Robert away—and then she came straight to me. He must have been furious: but I didn’t care for that.

I had been wanting her badly, but when I saw her, so bright and beautiful, looking as if she were the joy of life made incarnate, I should have liked to strike her hard, first on one cheek and then the other, deepening the rose to crimson, and leaving an ugly red mark for each finger.

“Have you a headache, dear?” she asked, in that velvet voice she keeps for me—as if I were a thing only fit for pity and protection.

“It’s my heart,” said I. “It feels like a clock running down. Oh, I wish I could die, and end it all! What’s the good of me—to myself or anyone?”

“Don’t talk like that, my poor one,” she said. “Shall I take you upstairs to your own room?”

“No, I think I should faint if I had to go upstairs,” I answered. “Yet I can’t stay here. What shall I do?”

“What about Uncle Eric’s study?” Di asked. She always calls Lord Mountstuart ‘Uncle Eric,’ though he isn’t her uncle. Her mother and his wife were sisters, that’s all: and then there was the other sister who married the British Secretary for Foreign Affairs, a cousin of Lord Mountstuart’s. That family seemed to have a craze for American girls; but Lord Mountstuart makes an exception of me. He’s civil, of course, because he’s an abject slave of Di’s, and she refused to come and pay a visit in England without me: but I give him the shivers, I know very well: and I take an impish joy in making him jump.

“I’m sure he won’t be there this evening,” Di went on, when I hesitated. “He’s playing bridge with a lot of dear old boys in the library, or was, half an hour ago. Come, let me help you there. It’s only a step.”

She put her pretty arm round my waist, and leaning on her I walked across the room, out into a corridor, through a tiny “bookroom” where odd volumes and old magazines are kept, into Lord Mountstuart’s study.

It is a nice room, which he uses much as his wife uses her boudoir. The library next door is rather a show place, but the study has only Lord Mountstuart’s favourite books in it. He writes there (he has written a novel or two, and thinks himself literary), and some pictures he has painted in different parts of the world hang on the walls: for he also fancies himself artistic.

In one corner is a particularly comfortable, cushiony lounge where, I suppose, the distinguished author lies and thinks out his subjects, or dreams them out. And it was to this that Di led me.

She settled me among some fat pillows of old purple and gold brocade, and asked if she should ring and get a little brandy.

“No,” I said, “I shall feel better in a few minutes. It’s so nice and cool here.”

“You look better already!” exclaimed Di. “Soon, when you’ve lain and rested awhile, you’ll be a different girl.”

“Ah, how I wish I could be a different girl!” I sighed. “A strong, well girl, and tall and beautiful, and admired by everyone,—like you—or Maxine de Renzie.”

“What makes you think of her?” asked Di, quickly.

“Ivor was just talking to me of her. You know he calls me his ‘pal,’ and tells me things he doesn’t tell everybody. He thinks a great deal about Maxine, still.”

“She’d be a difficult woman to forget, if she’s as attractive off the stage as she is on.”

“What a pity we didn’t come in time to meet here when she was playing in London with George Allendale. Everybody used to invite her to their houses, it seems. Ivor was telling me that he first met her here, and that it’s such a pleasant memory, whenever he comes to this house. I suppose that’s one reason he likes to come so much.”

“No doubt,” said Di sharply.

“He got so fascinated talking of her,” I went on. “He almost forgot that he had a dance with Mrs. Allendale. Of course Maxine had made a great hit, and all that; but she didn’t stand quite as high as she does now, since she’s become the fashion in Paris. Perhaps she had nothing except her salary, then, whereas she must have saved up a lot of money by this time. I have an idea that Ivor would have proposed to her when she was in London if he’d thought her success established.”

“Nonsense!” Di broke out, her cheeks very pink. “As if Ivor were the kind of man to think of such a thing!”

“He isn’t very rich, and he is very ambitious. It would be bad for him to marry a poor girl, or a girl who wasn’t well connected socially. He has to think of such things.”

I watched the effect of these words, with my eyes half shut; for of course Di has all her mother’s money, two hundred thousand English pounds; and through the Mountstuarts, and her aunt who is married to the Foreign Secretary, she has got to know all the best people in England. Besides, the King and Queen have been particularly nice to her since she was presented, so she has the run of their special set, as well as the political and artistic, and “old-fashioned exclusive” ones.

“Ivor Dundas is a law unto himself,” she said, “and he has plenty of good connections of his own. He’ll have a little money, too, some day, from an aunt or a god-mother, I believe. Anyway, he and Miss de Renzie had nothing more than a flirtation. Aunt Lilian told me so. She said Maxine was rather proud to have Ivor dangling about, because everyone likes him, and because his travels and his book were being a lot talked about just then. Naturally, he admired her, because she’s beautiful, and a very great actress—”

“Oh, your Aunt Lilian would make little of the affair,” I laughed. “She flirts with him herself.”

“Why, Lisa, Aunt Lilian’s over forty, and he’s twenty-nine!”

“Forty isn’t the end of the world for a woman, nowadays. She’s a beauty and a great lady. Ivor always wants the best of everything. She flirts with him, and he with her.”

Di laughed too, but only to make it seem as if she didn’t care. “You’d better not say such silly things to Uncle Eric,” she said, staring at the pattern of the cornice. “Aren’t those funny, gargoyley faces up there? I never noticed them before. But oh—about Mr. Dundas and Maxine de Renzie—I don’t think, really, that he troubles himself much about her any more, for the other day I—I happened to ask what she was playing in Paris now, and he didn’t know. He said he hadn’t been over to see her act, as it was too far away, and he was afraid when he wasn’t too busy, he was too lazy.”

“He said so to you, of course. But when he spends Saturday to Monday at Folkestone with the godmother who’s going to leave him her money, how easy to slip over the Channel to the fair Maxine, without anyone being the wiser.”

“Why shouldn’t he slip, or slide, or steam, or sail in a balloon, if he likes?” laughed Di, but not happily. “You’re looking much better, Lisa. You’ve quite a colour now. Do you feel strong enough to go upstairs?”

“I would rather rest here for awhile, since you think Lord Mountstuart is sure not to come,” said I. “These pillows are so comfortable. Then perhaps, by and by, I shall feel able to go back to the den, and watch the dancing. I should like to keep up, if I can, for I know I shan’t sleep, and the night will seem so long.”

“Very well,” said Di, speaking kindly, though I knew she would have liked to shake me. “I’m afraid I shall have to run away now, for my partner will think me so rude. What about supper?”

“Oh, I don’t want any. And I shall have gone upstairs before that,” I interrupted. “Go now, I don’t need you any more.”

“Ring, and send for me if you feel badly again.”

“Yes—yes.”

By this time she was at the door, and there she turned with a remorseful look in her eyes, as if she had been unkind and was sorry. “Even if you don’t send, I shall come back by and by, when I can, to see how you are,” she said. Then she was gone, and I nestled deeper into the sofa cushions, with the feeling that my head was so heavy, it must weigh down the pillows like a stone.

“She was afraid of missing Number 13 with Ivor,” I said to myself. “Well—she’s welcome to it now. I don’t think she’ll enjoy it much—or let him. Oh, I hope they’ll quarrel. I don’t think I’d mind anything, if only I was sure they’d never be nearer to each other. I wish Di would marry Lord Robert. Perhaps then Ivor would turn to me. Oh, my God, how I hate her—and all beautiful girls, who spoil the lives of women like me.”

A shivering fit shook me from head to feet, as I guessed that the time must be coming for Number 13. They were together, perhaps. What if, in spite of all, Ivor should tell Di how he loved her, and they should be engaged? At that thought, I tried to bring on a heart attack, and die; for at least it would chill their happiness if, when Lady Mountstuart’s ball was over, I should be found lying white and dead, like Elaine on her barge. I was holding my breath, with my hand pressed over my heart to feel how it was beating, when the door opened suddenly, and I heard a voice speaking.

Someone turned up the light. “I’ll leave you together,” said Lord Mountstuart; and the door was closed.

“What could that mean?” I wondered. I had supposed the two men had come in alone, but there must have been a third person. Who could it be? Had Lord Mountstuart been arranging a tête-â-tête between Di and Ivor Dundas?

The thought was like a hand on my throat, choking my life out. I must hear what they had to say to each other.

Without stopping to think more, I rolled over and let myself sink down into the narrow space between the low couch and the wall, sharply pulling the clinging folds of my chiffon dress after me. Then I lay still, my blood pounding in my temples and ears, and in my nostrils a faint, musty smell from the Oriental stuff that covered the lounge.

I could see nothing from where I lay, except the side of the couch, the wall, and a bit of the ceiling with the gargoyley cornice which Di had mentioned when she wanted to seem indifferent to the subject of our conversation. But I was listening with all my might for what was to come.

“Better lock the door, if you please, Dundas,” said a voice, which gave me a shock of surprise, though I knew it well.

Instead of Di, it was the Foreign Secretary who spoke.

“We won’t run the risk of interruptions,” he went on, with that slow, clear enunciation of his which most Oxford men have, and keep all their lives, especially men of the college that was his—Balliol. “I told Mountstuart that I wanted a private chat with you. Beyond that, he knows nothing, nor does anyone else except myself. You understand that this conversation of ours, whether anything comes of it or not, is entirely confidential. I have a proposal to make. You’ll agree to it or not, as you choose. But if you don’t agree, forget it, with everything I may have said.”

“My services and my memory are both at your disposal,” answered Ivor, in such a gay, happy voice that something told me he had already talked with Diana—and that in spite of me she had not snubbed him. “I am honoured—I won’t say flattered, for I’m too much in earnest—that you should place any confidence in me.”

I lay there behind the lounge and sneered at this speech of his. Of course, I said to myself, he would be ready to do anything to please the Foreign Secretary, since all the big plums his ambition craved were in the gift of that man.

“Frankly, I’m in a difficulty, and it has occurred to me that you can help me out of it better than anyone else I know,” said the smooth, trained voice. “It is a little diplomatic errand you will have to undertake for me tomorrow, if you want to do me a good turn.”

“I will undertake it with great pleasure, and carry it through to the best of my ability,” replied Ivor.

“I’m sure you can carry it through excellently,” said the Foreign Secretary, still fencing. “It will be good practice, if you succeed, for—any future duties in the career which may be opening to you.”

“He’s bribing him with that consulship,” I thought, beginning to be very curious indeed as to what I might be going to hear. My heart wasn’t beating so thickly now. I could think almost calmly again.

“I thank you for your trust in me,” said Ivor.

“A little diplomatic errand,” repeated the Foreign Secretary. “In itself the thing is not much: that is, on the face of it. And yet, in its relation with other interests, it becomes a mission of vast importance, incalculable importance. When I have explained, you will see why I apply to you. Indeed, I came to my cousin Mountstuart’s house expressly because I was told you would be at his wife’s ball. My regret is, that the news which brought me in search of you didn’t reach me earlier, for if it had I should have come with my wife, and have got at you in time to send you off—if you agreed to go—to-night. As it is, the matter will have to rest till to-morrow morning. It’s too late for you to catch the midnight boat across the Channel.”

“Across the Channel?” echoed Ivor. “You want me to go to France?”

“Yes.”

“One could always get across somehow,” said Ivor, thoughtfully, “if there were a great hurry.”

“There is—the greatest. But in this case, the more haste, the less speed. That is, if you were to rush off, order a special train, and charter a tug or motor boat at Dover, as I suppose you mean, my object would probably be defeated. I came to you because those who are watching this business wouldn’t be likely to guess I had given you a hand in it. All that you do, however, must be done quietly, with no fuss, no sign of anything unusual going on. It was natural I should come to a ball given by my wife’s sister, whose husband is my cousin. No one knows of this interview of ours: I believe I may make my mind easy on that score, at least. And it is equally natural that you should start on business or pleasure of your own, for Paris to-morrow morning; also that you should meet Mademoiselle de Renzie there.”

“Mademoiselle de Renzie!” exclaimed Ivor, off his guard for an instant, and showing plainly that he was taken aback.

“Isn’t she a friend of yours?” asked the Foreign Secretary rather sharply. Though I couldn’t see him, I knew exactly how he would be looking at Ivor, his keen grey eyes narrowed, his clean-shaven lips drawn in, the long, well-shaped hand, of which he is said to be vain, toying with the pale Malmaison pink he always wears in his buttonhole.

“Yes, she is a friend of mine,” Ivor answered. “But—”

“A ‘but’ already! Perhaps I’d better tell you that the mission has to do with Mademoiselle de Renzie, and, directly, with no one else. She has acted as my agent in Paris.”

“Indeed! I didn’t dream that she dabbled in politics.”

“And you should not dream it from any word of mine, Mr. Dundas, if it weren’t necessary to be entirely open with you, if you are to help me in this matter. But before we go any further, I must know whether Mademoiselle de Renzie’s connection with this business will for any reason keep you out of it.”

“Not if—you need my help,” said Ivor, with an effort. “And I beg you won’t suppose that my hesitation has anything to do with Miss de Renzie herself. I have for her the greatest respect and admiration.”

“We all have,” returned the Foreign Secretary, “especially those who know her best. Among her many virtues, she’s one of the few women who can keep a secret—her own and others. She is a magnificent actress—on the stage and off. And now I have your promise to help me, I must tell you it’s to help her as well: therefore I owe you the whole truth, or you will be handicapped. For several years Mademoiselle de Renzie has done good service—secret service, you must understand—for Great Britain.”

“By Jove! Maxine a political spy!” Ivor broke out impulsively.

“That’s rather a hard name, isn’t it? There are better ones. And she’s no traitor to her country, because, as you perhaps know, she’s Polish by birth. I can assure you we’ve much for which to thank her cleverness and tact—and beauty. For our sakes I’m sorry that she’s serving our interests professionally for the last time. For her own sake, I ought to rejoice, as she’s engaged to be married. And if you can save her from coming to grief over this very ticklish business, she’ll probably live happily ever after. Did you know of her engagement?”

“No,” replied Ivor. “I saw Miss de Renzie often when she was acting in London a year ago; but after she went to Paris—of course, she’s very busy and has crowds of friends; and I’ve only crossed once or twice since, on hurried visits; so we haven’t met, or written to each other.”

(“Very good reason,” I thought bitterly, behind my sofa. “You’ve been busy, too—falling in love with Diana Forrest.”)

“It hasn’t been announced yet, but I thought as an old friend you might have been told. I believe Mademoiselle wants to surprise everybody when the right time comes—if the poor girl isn’t ruined irretrievably in this affair of ours.”

“Is there really serious danger of that?” “The most serious. If you can’t save her, not only will the Entente Cordiale be shaken to its foundations (and I say nothing of my own reputation, which is at stake), but her future happiness will be broken in the crash, and—she says—she will not live to suffer the agony of her loss. She will kill herself if disaster comes; and though suicide is usually the last resource of a coward, Mademoiselle de Renzie is no coward, and I’m inclined to think I should come to the same resolve in her place.”

“Tell me what I am to do,” said Ivor, evidently moved by the Foreign Secretary’s strange words, and his intense earnestness.

“You will go to Paris by the first train to-morrow morning, without mentioning your intention to anyone; you will drive at once to some hotel where you have never stayed and are not known. I will find means of informing the lady what hotel you choose. You will there give a fictitious name (let us say, George Sandford) and you will take a suite, with a private sitting-room. That done, you will say that you are expecting a lady to call upon you, and will see no one else. You will wait till Mademoiselle de Renzie appears, which will certainly be as soon as she can possibly manage; and when you and she are alone together, sure that you’re not being spied upon, you will put into her hands a small packet which I shall give you before we part to-night.”

“It sounds simple enough,” said Ivor, “if that’s all.”

“It is all. Yet it may be anything but simple.”

“Would you prefer to have me call at her house, and save her coming to a hotel? I’d willingly do so if—”

“No. As I told you, should it be known that you and she meet, those who are watching her at present ought not to suspect the real motive of the meeting. So much the better for us: but we must think of her. After four o’clock every afternoon, the young Frenchman she’s engaged to is in the habit of going to her house, and stopping until it’s time for her to go to work. He dines with her, but doesn’t drive with her to the theatre, as that would be rather too public for the present, until their engagement’s announced. He adores her, but is inconveniently jealous, like most Latins. It’s practically certain that he’s heard your name mentioned in connection with hers, when she was in London, and as a Frenchman invariably fails to understand that a man can admire a beautiful woman without being in love with her, your call at her house might give Mademoiselle Maxine a mauvais quart d’heure.”

“I see. But if she sends him away, and comes to my hotel—”

“She’ll probably make some excuse about being obliged to go to the theatre early, and thus get rid of him. She’s quite clever enough to manage that. Then, as your own name won’t appear on any hotel list in the papers next day, the most jealous heart need have no cause for suspicion. At the same time, if certain persons whom Mademoiselle—and we, too—have to fear, do find out that she has visited Ivor Dundas, who has assumed a false name for the pleasure of a private interview with her, interests of even deeper importance than the most desperate love affair may still, we’ll hope, be guarded by the pretext of your old friendship. Now, you understand thoroughly?”

“I think so,” replied Ivor, very grave and troubled, I knew by the change in his manner, out of which all the gaiety had been slowly drained. “I will do my very best.”

“If you are sacrificing any important engagements of your own for the next two days, you won’t suffer for it in the end,” remarked the Foreign Secretary meaningly.

No doubt Ivor saw the consulship at Algiers dancing before his eyes, bound up with an engagement to Di, just as a slice of rich plum cake and white bride cake are tied together with bows of satin ribbons sometimes, in America. I didn’t want him to have the consulship, because getting that would perhaps mean getting Di, too.

“Thank you,” said Ivor.

“And what hotel shall you choose in Paris?” asked the Foreign Secretary. “It should be a good one, I don’t need to remind you, where Mademoiselle de Renzie could go without danger of compromising herself, in case she should be recognised in spite of the veil she’s pretty certain to wear. Yet it shouldn’t be in too central a situation.”

“Shall it be the Élysèe Palace?” asked Ivor.

“That will do very well,” replied the other, after reflecting for an instant. And I could have clapped my hands, in what Ivor would call my “impish joy,” when it was settled; for the Élysèe Palace is where Lord and Lady Mountstuart stop when they visit Paris, and they’d been talking of running over next day with Lord Robert West, to look at a wonderful new motor car for sale there—one that a Rajah had ordered to be made for him, but died before it was finished. Lady Mountstuart always has one new fad every six months at least, and her latest is to drive a motor car herself. Lord Robert is a great expert—can make a motor, I believe, or take it to pieces and put it together again; and he’d been insisting for days that she would be able to drive this Rajah car. She’d promised, that if not too tired she’d cross to Paris the day after the ball, taking the afternoon train, via Boulogne, as she wouldn’t be equal to an early start. Now, I thought, how splendid it would be if she should see Maxine at the hotel with Ivor!

The Foreign Secretary was advising Ivor to wire the Élysèe Palace for rooms without any delay, as there must be no hitch about his meeting Maxine, once it was arranged for her to go there. “Any misunderstanding would be fatal,” he went on, as solemnly as if the safety of Maxine’s head depended upon Ivor’s trip. “I only wish I could have got you off to-night; and in that case you might have gone to her own house, early in the morning. She is in a frightful state of mind, poor girl. But it was only to-day that the contents of the packet reached me, and was shown to the Prime Minister. Then, it was just before I hurried round here to see you that I received a cypher telegram from her, warning me that Count Godensky—of whom you’ve probably heard—an attaché of the Russian embassy in Paris, somehow has come to suspect a—er—a game in high politics which she and I have been playing; her last, according to present intentions, as I told you. I have an idea that this man, who’s well known in Paris society, proposed to Mademoiselle de Renzie, refused to take no for an answer, and bored her until she perhaps was goaded into giving him a severe snub. Godensky is a vain man, and wouldn’t forgive a snub, especially if it had got talked about. He’d be a bad enemy: and Mademoiselle seems to think that he is a very bitter and determined enemy. Apparently she doesn’t know how much he has found out, or whether he has actually found out anything at all, or merely guesses, and ‘bluffs.’ But one thing is unfortunately certain, I believe. Every boat and every train between London and Paris will be watched more closely than usual for the next day or two. Any known or suspected agent wouldn’t get through unchallenged. But I can see no reason why you should not.”

“Nor I,” answered Ivor, laughing a little. “I think I could make some trouble for anyone who tried to stop me.”

“Caution above all! Remember you’re in training for a diplomatic career, what? If you should lose the packet I’m going to give you, I prophesy that in twenty-four hours the world would be empty of Maxine de Renzie: for the circumstances surrounding her in this transaction are peculiar, the most peculiar I’ve ever been entangled in, perhaps, in rather a varied experience; and they intimately concern her fiancé, the Vicomte Raoul du Laurier—”

“Raoul du Laurier!” exclaimed Ivor. “So she’s engaged to marry him!”

“Yes. Do you know him?”

“I have friends who do. He’s in the French Foreign Office, though they say he’s more at home in the hunting field, or writing plays—”

“Which don’t get produced. Quite so. But they will get produced some day, for I believe he’s an extremely clever fellow in his way—in everything except the diplomatic ‘trade’ which his father would have him take up, and got him into, through Heaven knows what influence. No; Du Laurier’s no fool, and is said to be a fine sportsman, as well as almost absurdly good-looking. Mademoiselle Maxine has plenty of excuse for her infatuation—for I assure you it’s nothing less. She’d jump into the fire for this young man, and grill with a Joan of Arc smile on her face.”

This would have been pleasant hearing for Ivor, if he’d ever been really in love with Maxine; but I was obliged to admit to myself that he hadn’t, for he didn’t seem to care in the least. On the contrary, he grew a little more cheerful.

“I can see that du Laurier’s being in the French Foreign Office might make it rather awkward for Miss de Renzie if she—if she’s been rather too helpful to us,” he said.

“Exactly. And thereby hangs a tale—a sensational and even romantic tale almost complicated enough for the plot of a novel. When you meet Mademoiselle to-morrow afternoon or evening, if she cares to take you into her confidence, in reward for your services, in regard to some private interests of her own which have got themselves wildly mixed up with the gravest political matters, she’s at liberty to do so as far as I’m concerned, for you are to be trusted, and deserve to be trusted. You may say that to her from me, if the occasion arises. I hope with all my heart that everything may go smoothly. If not—the Entente Cordiale may burst like a bomb. I—who have made myself responsible in the matter, with the clear understanding that England will deny me if the scheme’s a failure—shall be shattered by a flying fragment. The favourite actress of Paris will be asphyxiated by the poisonous fumes; and you, though I hope no worse harm may come to you, will mourn for the misfortunes of others. Your responsibility will be such that it will be almost as if you carried the destructive bomb itself, until you get the packet into the hands of Maxine de Renzie.” “Good heavens, I shall be glad when she has it!” said Ivor.

“You can’t be gladder than she—or I. And here it is,” replied the Foreign Secretary. “I consider it great luck to have found such a messenger, at a house I could enter without being suspected of any motive more subtle than a wish to eat a good supper, or to meet some of the prettiest women in London.”

I would have given a great deal to see what he was giving Ivor to take to Maxine, and I was half tempted to lift myself up and peep at the two from behind the lounge, but I could tell from their voices that they were standing quite near, and it would have been too dangerous. The Foreign Secretary, who is rather a nervous man, and fastidious about a woman’s looks, never could bear me: and I believe he would have thought it almost as justifiable as drowning an ugly kitten, to choke me if he knew I’d overheard his secrets.

However, Ivor’s next words gave me some inkling of what I wished to know. “It’s importance evidently doesn’t consist in bulk,” he said lightly. “I can easily carry the case in my breast pocket.”

“Pray put it there at once, and guard it as you would guard the life and honour of a woman,” said the Foreign Secretary solemnly. “Now, I, must go and look for my wife. It’s better that you and I shouldn’t be seen together. One never knows who may have got in among the guests at a crush like this. I will go out at one door, and when you’ve waited for a few minutes, you can go, by way of another.”

A moment later there was silence in the room, and I knew that Ivor was alone. What if I spoke, and startled him? All that is impish in me longed to see how his face would look; but there was too much at stake. Not only would I hate to have him scorn me for an eavesdropper, but I had already built up a great plan for the use I could make of what I had overheard.

When Ivor was safely out of the room, my first thought was to escape from behind the lounge, and get upstairs to my own quarters. But just as I had sat up, very cramped and wretched, with one foot and one arm asleep, Lord Mountstuart came in again, and down I had to duck.

He had brought a friend, who was as mad about old books and first editions, as he; a stuffy, elderly thing, who had never seen Lord Mountstuart’s treasures before. As both were perfectly daft on the subject, they must have kept me lying there an hour, while they fussed about from one glass-protected book-case to another, murmuring admiration of Caxtons, or discussing the value of a Mazarin Bible, with their noses in a lot of old volumes which ought to have been eaten up by moths long ago. As for me, I should have been delighted to set fire to the whole lot.

At last Lord Mountstuart (whom I’ve nicknamed “Stewey”) remembered that there was a ball going on, and that he was the host. So he and the other duffer pottered away, leaving the coast clear and the door wide open. It was just my luck (which is always bad and always has been) that a pair of flirting idiots, for whom the conservatory, or our “den,” or the stairs, wasn’t secluded enough, must needs be prying about and spy that open door before I had conquered my cramps and got up from behind the sofa.

The dim light commended itself to their silliness, and after hesitating a minute, the girl—whoever she was—allowed herself to be drawn into a room where she had no business to be. Then, to make bad worse, they selected the lounge to sit upon, and I had to lie closely wedged against the wall, with “pins and needles” pricking all over my cramped body, while some man I didn’t know proposed and was accepted by some girl I shall probably never see.

They continued to sit, making a tremendous fuss about each other, until voices were “heard off,” as they say in the directions for theatricals, whereupon they sprang up and hurried out like “guilty things upon a fearful summons.”

By that time I was more dead than alive, but I did manage to crawl out of my prison, and creep up to my room by a back stairway which the servants use. But it was very late now, and people were going, even the young ones who love dancing. As soon as I was able, I scuttled out of my ball dress and into a dressing gown. Also I undid my hair, which is my one beauty, and let it hang over my shoulders, streaming down in front on each side, so that nobody would know one shoulder is higher than the other. It wasn’t that I was particularly anxious to appear well before Di (though I have enough vanity not to like the contrast between us to seem too great, even when she and I are alone), but because I wanted her to think, when she came to my room, that I’d been there a long time.

I was sure she would come and peep in at the door, to steal away if she found me asleep, or to enquire how I felt if I were awake.

By and by the handle of the door moved softly, just as I had expected, and seeing a light, Di came in. It was late, and she had danced all night, but instead of looking tired she was radiant. When she spoke, her voice was as gay and happy as Ivor’s had been when he first came into Lord Mountstuart’s study with the Foreign Secretary.

I said that I was much better, and had had a nice rest; that if I hadn’t wanted to hear how everything had gone at the ball, I should have been in bed and asleep long ago.

“Everything went very well,” said she. “I think it was a great success.”

“Did you dance every dance?” I asked, working up slowly to what I meant to say.

“Except a few that I sat out.”

“I can guess who sat them out with you,” said I. “Ivor Dundas. And one was number thirteen, wasn’t it?”

“How did you know?”

“He told me he was going to have thirteen with you. Oh, you needn’t try to hide anything from me. He tells most things to his ‘Imp.’ Was he nice when he proposed?”

“He didn’t propose.”

“I’ll give you the sapphire bracelet Lady Mountstuart gave me, if he didn’t tell you he loved you, and ask if there’d be a chance for him in case he got Algiers.”

“I wouldn’t take your bracelet even if—if—. But you’re a little witch, Lisa.”

“Of course I am!” I exclaimed, smiling, though I had a sickening wrench of the heart. “And I suppose you forgot all his faults and failings, and said he could have you, Algiers or no Algiers.”

“I don’t believe he has all those faults and failings you were talking about this evening,” said Di, with her cheeks very pink. “He may have flirted a little at one time. Women have spoiled him a lot. But—but he does love me, Lisa.”

“And he did love Maxine!” I laughed.

“He didn’t. He never loved her. I—you see, you put such horrid thoughts into my head that—that I just mentioned her name when he said to-night—oh, when he said the usual things, about never having cared seriously for anyone until he saw me. Only—it seems treacherous to call them ‘usual’ because—when you love a man you feel that the things he says can never have been said before, in the same way, by any other man to any other woman.”

“Only perhaps by the same man to another woman,” I mocked at her, trying to act as if I were teasing in fun.

“Lisa, you can be hateful sometimes!” she cried.

“It’s only for your good, if I’m hateful now,” I said. “I don’t want to have you disappointed, when it’s too late. I want you to keep your eyes open, and see exactly where you’re going. It’s the truest thing ever said that ‘love is blind.’ You can’t deny that you’re in love with Ivor Dundas.”

“I don’t deny it,” she answered, with a proud air which would, I suppose, have made Ivor want to kiss her.

“And you didn’t deny it to him?”

“No, I didn’t. But thanks to you, I put him upon a kind of probation. I wish I hadn’t, now. I wish I’d shown that I trusted him entirely. I know he deserves to be trusted; and to-morrow I shall tell him—”

“I don’t think I should commit myself any further till day after to-morrow,” said I drily. “Indeed, you couldn’t if you wanted to, unless you wrote or wired. You won’t see him to-morrow.”

“Yes, I shall,” she contradicted me, opening those big hazel eyes of hers, that looked positively black with excitement. “He’s going to the Duchess of Glasgow’s bazaar, because I said I should most likely be there: and I will go—”

“But he won’t.”

“How can you know anything about it?”

“I do know, everything. And I’ll tell you what I know, if you’ll promise me two things.”

“What things?”

“That you won’t ask me how I found out, and that you’ll swear never to give me away to anybody.”

“Of course I wouldn’t ‘give you away,’ as you call it. But—I’m not sure I want you to tell me. I have faith in Ivor. I’d rather not hear stories behind his back.”

“Oh, very well, then, go to the Duchess’s to-morrow,” I snapped, “and wear your prettiest frock to please Ivor, when just about that time he’ll be arriving in Paris to keep a very particular engagement with Maxine de Renzie.”

Di grew suddenly pale, and her eyes looked violet instead of black. “I don’t believe he’s going to Paris!” she exclaimed.

“I know he’s going. And I know he’s going especially to see Maxine.”

“It can’t be. He told me to-night he wouldn’t cross the street to see her. I—I made it a condition—that if he found he cared enough for her to want to see her again, he must go, of course: but he must give up all thought of me. If I’m to reign, I must reign alone.”

“Well, then, on thinking it over, he probably did find that he wanted to see her.”

“No. For he loved me just as much when we parted, only half an hour ago.”

“Yet at least two hours ago he’d arranged a meeting with Maxine for to-morrow afternoon.”

“You’re dreaming.”

“I was never wider awake: or if I’m dreaming, you can dream the same dream if you’ll be at Victoria Station to-morrow, or rather this morning, when the boat train goes out at 10 o’clock.”

“I will be there!” cried Di, changing from red to white. “And you shall be with me, to see that you’re wrong. I know you will be wrong.”

“That’s an engagement,” said I. “At 10 o’clock, Victoria Station, just you and I, and nobody else in the house the wiser. If I’m right, and Ivor’s there, shall you think it wise to give him up?”

“He might be obliged to go to Paris, suddenly, for some business reason, without meaning to call on Maxine de Renzie—in which case he’d probably write me. But—at the station, I shall ask him straight out—that is, if he’s there, as I’m sure he won’t be—whether he intends to see Mademoiselle de Renzie. If he says no, I’ll believe him. If he says yes—”

“You’ll tell him all is over between you?”

“He’d know that without my telling, after our talk last night.”

“And whatever happens, you will say nothing about having heard Maxine’s name from me?”

“Nothing,” Di answered. And I knew she would keep her word.

It is rather a startling sensation for a man to be caught suddenly by the nape of the neck, so to speak, and pitched out of heaven down to—the other place.

But that was what happened to me when I arrived at Victoria Station, on my way to Paris.

I had taken my ticket and hurried on to the platform without too much time to spare (I’d been warned not to risk observation by being too early) when I came face to face with the girl whom, at any other time, I should have liked best to meet: whom at that particular time I least wished to meet: Diana Forrest.

“The Imp”—Lisa Drummond—was with her: but I saw only Di at first— Di, looking a little pale and harassed, but beautiful as always. Only last night I had told her that Paris had no attractions for me. I had said that I didn’t care to see Maxine de Renzie: yet here I was on the way to see her, and here was Di discovering me in the act of going to see, her.

Of course I could lie; and I suppose some men, even men of honour, would think it justifiable as well as wise to lie in such a case, when explanations were forbidden. But I couldn’t lie to a girl I loved as I love Diana Forrest. It would have sickened me with life and with myself to do it: and it was with the knowledge in my mind that I could not and would not lie, that I had to greet her with a conventional “Good morning.”

“Are you going out of town?” I asked, with my hat off for her and for the Imp, whose strange little weazened face I now saw looking over my tall love’s shoulders. It had never before struck me that the Imp was like a cat; but suddenly the resemblance struck me—something in the poor little creature’s expression, it must have been, or in her greenish grey eyes which seemed at that moment to concentrate all the knowledge of old and evil things that has ever come into the world since the days of the early Egyptians—when a cat was worshipped.

“No, I’m not going out of town,” Di answered. “I came here to meet you, in case you should be leaving by this train, and I brought Lisa with me.”

“Who told you I was leaving?” I asked, hoping for a second or two that the Foreign Secretary had confided to her something of his secret—guessing ours, perhaps, and that my unexpected, inexplicable absence might injure me with her.

“I can’t tell you,” she answered. “I didn’t believe you would go; even though I got your letter by the eight o’clock post this morning.”

“I’m glad you got that,” I said. “I posted it soon after I left you last night.”

“Why didn’t you tell me when we were bidding each other good-bye, that you wouldn’t be able to see me this afternoon, instead of waiting to write?”

“Frankly and honestly,” I said (for I had to say it), “just at the moment, and only for the moment, I forgot about the Duchess of Glasgow’s bazaar. That was because, after I decided to drop in at the bazaar, something happened which made it impossible for me to go. In my letter I begged you to let me see you to-morrow instead; and now I beg it again. Do say ‘yes.’”

“I’ll say yes on one condition—and gladly,” she replied, with an odd, pale little smile, “that you tell me where you’re going this morning. I know it must seem horrid in me to ask, but—but—oh, Ivor, it isn’t horrid, really. You wouldn’t think it horrid if you could understand.”

“I’m going to Paris,” I answered, beginning to feel as if I had a cold potato where my heart ought to be. “I am obliged to go, on business.”

“You didn’t say anything about Paris in your letter this morning, when you told me you couldn’t come to the Duchess’s,” said Di, looking like a beautiful, unhappy child, her eyes big and appealing, her mouth proud. “You only mentioned ‘an urgent engagement which you’d forgotten.’”

“I thought that would be enough to explain, in a hurry,” I told her, lamely.

“So it was—so it would have been,” she faltered, “if it hadn’t been for—what we said last night about—Paris. And then—I can’t explain to you, Ivor, any more than it seems you can to me. But I did hear you meant to go there, and—after our talk, I couldn’t believe it. I didn’t come to the station to find you; I came because I was perfectly sure I wouldn’t find you, and wanted to prove that I hadn’t found you. Yet—you’re here.”

“And, though I am here, you will trust me just the same,” I said, as firmly as I could.

“Of course. I’ll trust you, if—”

“If what?”

“If you’ll tell me just one little, tiny thing: that you’re not going to see Maxine de Renzie.”

“I may see her,” I admitted.

“But—but at least, you’re not going on purpose?”

This drove me into a corner. Without being disloyal to the Foreign Secretary, I could not deny all personal desire to meet Maxine. Yet to what suspicion was I not laying myself open in confessing that I deliberately intended to see her, having sworn by all things a man does swear by when he wishes to please a girl, that I didn’t wish to see Maxine, and would not see Maxine?

“You said you’d trust me, Di,” I reminded her. “For Heaven’s sake don’t break that promise.”

“But—if you’re breaking a promise to me?”

“A promise?”

“Worse, then! Because I didn’t ask you to promise. I had too much faith in you for that. I believed you when you said you didn’t care for—anyone but me. I’ve told Lisa. It doesn’t matter our speaking like this before her. I asked you to wait for my promise for a little while, until I could be quite sure you didn’t think of Miss de Renzie as—some people fancied you did. If you wanted to see her, I said you must go, and you laughed at the idea. Yet the very next morning, by the first train, you start.”

“Only because I am obliged to,” I hazarded in spite of the Foreign Secretary and his precautions. But I was punished for my lack of them by making matters worse instead of better for myself.

“Obliged to!” she echoed. “Then there’s something you must settle with her, before you can be—free.”

The guard was shutting the carriage doors. In another minute I should lose the train. And I must not lose the train. For her future and mine, as well as Maxine’s, I must not.

“Dearest,” I said hurriedly, “I am free. There’s no question of freedom. Yet I shall have to go. I hold you to your word. Trust me.”

“Not if you go to her—this day of all days.” The words were wrung from the poor child’s lips, I could see, by sheer anguish, and it was like death to me that I should have to cause her this anguish, instead of soothing it.

“You shall. You must,” I commanded, rather than implored. “Good-bye, darling—precious one. I shall think of you every instant, and I shall come back to you to-morrow.”

“You needn’t. You need never come to me again,” she said, white lipped. And the guard whistled, waving his green flag.

“Don’t dare to say such a cruel thing—a thing you don’t mean!” I cried, catching at the closed door of a first-class compartment. As I did so, a little man inside jumped to the window and shouted, “Reserved! Don’t you see it’s reserved?” which explained the fact that the door seemed to be fastened.

I stepped back, my eyes falling on the label to which the man pointed, and would have tried the handle of the next carriage, had not two men rushed at the door as the train began to move, and dexterously opened it with a railway key. Their throwing themselves thus in my way would have lost me my last chance of catching the moving train, had I not dashed in after them. If I could choose, I would be the last man to obtrude myself where I was not wanted, but there was no time to choose; and I was thankful to get in anywhere, rather than break my word. Besides, my heart was too sore at leaving Diana as I had had to leave her, to care much for anything else. I had just sense enough to fight my way in, though the two men with the key (not the one who had occupied the compartment first), now yelled that it was reserved, and would have pushed me out if I hadn’t been too strong for them. I had a dim impression that, instead of joining with the newcomers, the first man, who would have kept the place to himself before their entrance, seemed willing to aid me against the others. They being once foisted upon him, he appeared to wish for my presence too, or else he merely desired to prevent me from being dashed onto the platform and perhaps killed, for he thrust out a hand and tried to pull me in.

At the same time a guard came along, protesting against the unseemly struggle, and the carriage door was slammed shut upon us all four.

When I got my balance, and was able to look out, the train had gone so far that Diana and Lisa had been swept away from my sight. It was like a bad omen; and the fear was cold upon me that I had lost my love for ever.

At that moment I suffered so atrociously that if it had not been too late, I fear I should have sacrificed Maxine and the Foreign Secretary and even the Entente Cordiale (provided he had not been exaggerating) for Di’s sake, and love’s sake. But there was no going back now, even if I would. The train was already travelling almost at full speed, and there was nothing to do but resign myself to the inevitable, and hope for the best. Someone, it was clear, had tried to work mischief between Diana and me, and there were only too many chances that he had succeeded. Could it be Bob West, I asked myself, as I half-dazedly looked for a place to sit down among the litter of small luggage with which the first occupant of the carriage had strewn every seat. I knew that Bob was as much in love with Di as a man of his rather unintellectual, unimaginative type could be, and he hadn’t shown himself as friendly lately to me as he once had: still, I didn’t think he was the sort of fellow to trip up a rival in the race by a trick, even if he could possibly have found out that I was going to Paris this morning.

“Won’t you sit here, sir?” a voice broke into my thoughts, and I saw that the little man had cleared a place for me next his own, which was in a corner facing the engine. Thanking him absent-mindedly, I sat down, and began to observe my travelling companions for the first time.

So far, their faces had been mere blurs for me: but now it struck me that all three were rather peculiar; that is, peculiar when seen in a first-class carriage.

The man who had reserved the compartment for himself, and who had removed a bundle of golf sticks from the seat to make room for me, did not look like a typical golfer, nor did he appear at all the sort of person who might be expected to reserve a whole compartment for himself. He was small and thin, and weedy, with little blinking, pink-rimmed eyes of the kind which ought to have had white lashes instead of the sparse, jet black ones that rimmed them. His forehead, though narrow, suggested shrewdness, as did the expression of those light coloured eyes of his, which were set close to the sharp, slightly up-turned nose. His hair was so black that it made his skin seem singularly pallid, though it was only sallow; and a mean, rabbit mouth worked nervously over two prominent teeth. Though his clothes were good, and new, they had the air of having been bought ready made; and in spite of his would-be “smart” get up, the man (who might have been anywhere between thirty and thirty-eight) looked somewhat like an ex-groom, or bookmaker, masquerading as a “swell.”

The two intruders who had violated the sanctity of the reserved compartment by means of their railway key were both bigger and more manly than he who had a right to it. One was dark, and probably Jewish, with a heavy beard and moustache, in the midst of which his sensual and cruel mouth pouted disagreeably red. The other was puffy and flushed, with a brick-coloured complexion deeply pitted by smallpox. They also were flashily dressed with “horsey” neckties and conspicuous scarf-pins. As I glanced at the pair, they were talking together in a low voice, with an open newspaper held up between them; but the man who had helped me in against their will sat silent, staring out of the window and uneasily fingering his collar. Not one of the trio was, apparently, paying the slightest attention to me, now that I was seated; nevertheless I thought of the large, long letter-case which I carried in an inner breast pocket of my carefully buttoned coat. I would not attract attention to the contents of that pocket by touching it, to assure myself that it was safe, but I had done so just before meeting Di, and I felt certain that nothing could have happened to it since.

I folded my arms across my chest, glanced up to see where the cord of communication might be found in case of emergency; and then reflected that these men were not likely to be dangerous, since I had followed them into the compartment, not they me. This thought was reassuring, as they were three to one if they combined against me, and the train was, unfortunately, not entirely a corridor train. Therefore, having assured myself that I was not among spies bent on having my life or the secret I carried, I forgot about my fellow-travellers, and fell into gloomy speculations as to my chances with Diana. I had been loving her, thinking of little else but her and my hopes of her, for many months now; but never had I realised what a miserable, empty world it would be for me without Di for my own, as I did now, when I had perhaps lost her.

Not that I would allow myself to think that I could not get her back. I would not think it. I would force her to believe in me, to trust me, even to repent her suspicions, though appearances were all against me, and Heaven knew how much or when I might be permitted to explain. I would not be a man if I took her at her word, and let her slip from me, no matter how many times that word were repeated; so I told myself over and over. Yet a voice inside me seemed to say that nothing could be as it had been; that I’d sacrificed my happiness to please a stranger, and to save a woman whom I had never really loved.

Di was so beautiful, so sweet, so used to being admired by men; there were so many who loved her, so many with a thousand times more to offer than I had or would ever have: how could I hope that she would go on caring for me, after what had happened to-day? I wondered. She hadn’t said in actual words last night that she would marry me, whereas this morning she had almost said she never would. I should have nobody to blame but myself if I came back to London to-morrow to find her engaged to Lord Robert West—a man who, as his brother has no children, might some day make her a Duchess.

“Sorry to have seemed rude just now, sir,” said one of the two railway-key men, suddenly reminding me of his unnecessary existence. “Hardly knew what I was about when I shoved you away from the door. Me and my friend was afraid of missing the train, so we pushed—instinct of self-preservation, I suppose,” and he chuckled as if he had got off some witticism. “Anyhow, I apologise. Nothing intentional, ’pon my word.”

“Thanks. No apology is necessary,” I replied as indifferently as I felt.

“That’s all right, then,” finished the Jewish-faced man, who had spoken. He turned to his companion, and the two resumed their conversation behind the newspaper: but I now became conscious that they occasionally glanced over the top at their neighbour or at me, as if their whole attention were not taken up with the news of the day.

Any interest they might feel in me, provided it had nothing to do with a certain pocket, they were welcome to: but the little man was apparently not of the same mind concerning himself. His nervously twitching hand on the upholstered seat-arm which separated his place from mine attracted my attention, which was then drawn up to his face. He was so sickly pale, under a kind of yellowish glaze spread over his complexion, that I thought he must be ill, perhaps suffering from train sickness, in anxious anticipation of the horrors which might be in store for him on the boat. Presently he pulled out a red-bordered handkerchief, and unobtrusively wiped his forehead, under his checked travelling cap. When he had done this, I saw that his hair was left streaked with damp; and there was a faint, purplish stain on the handkerchief, observing which with evident dismay he stuffed the big square of coarse cambric hastily into his pocket.

“The little beast must dye his hair,” I thought contemptuously. “Perhaps he’s an albino, really. His eyes look like it.”

With that, he threw a frightened glance at me, which caused me to turn away and spare him the humiliation of knowing that he was observed. But immediately after, he made an effort to pull himself together, picking up a book he had laid down to wipe his forehead and holding it so close to his nose that the printed page must have been a mere blur, unless he were very near-sighted. Thus he sat for some time; yet I felt that no look thrown by the other two was lost on him. He seemed to know each time one of them peered over the newspaper; and when at last the train slowed down by the Admiralty Pier all his nervousness returned. His small, thin hands, freckled on their backs, hovered over one piece of luggage after another, as if he could not decide how to pile the things together.

Naturally I had not brought my man with me on this errand, therefore I had let my suitcase go into the van, that I might have both hands free, and I had nothing to do when the train stopped but jump out and make for the boat. Nevertheless I lingered, folding up a newspaper, and tearing an article out of a magazine by way of excuse; for it was not my object to be caught in a crowd and hustled, perhaps, by some clever wretches who might be lying in wait for what I had in my pocket. It seemed impossible that anyone could have learned that I was playing messenger between the British Secretary for Foreign Affairs and Maxine de Renzie: still, the danger and difficulty of the apparently simple mission had been so strongly impressed on me that I did not intend to neglect any precaution.

I lingered therefore; and the Jewish-looking man with his heavy-faced friend lingered also, for some reason of their own. They had no luggage, except a small handbag each, but these they opened at the last minute to stuff in their newspapers, and apparently to review the other contents. Presently, when the first rush for the boat was over, and the porters who had come to the door of our compartment had gone away empty-handed, I would have got out, had I not caught an imploring glance from the little man who had reserved the carriage. Perhaps I imagined it, but his pink-rimmed eyes seemed to say, “For heaven’s sake, don’t leave me alone with these others.”

“Would you be so very kind, sir,” he said to me, “to beckon a porter, as you are near the door? I find after all that I shan’t be able to carry everything myself.”

I did as he asked; and there was so much confusion in the carriage when the porter came, that in self-defence the two friends got out with their bags. I also descended and would have followed in the wake of the crowd, if the little man had not called after me. He had lost his ticket, he said. Would I be so extremely obliging as to throw an eye about the platform to see if it had fallen there?

I did oblige him in this manner, without avail; but by this time he had found the missing treasure in the folds of his travelling rug; and scrambling out of the carriage, attended by the porter I had secured for him, he would have walked by my side towards the boat, had I not dropped behind a few steps, thinking—as always—of the contents of that inner breast pocket.

He and I were now at the tail-end of the procession hastening boatward, or almost at the tail, for there were but four or five other passengers—a family party with a fat nurse and crying baby—behind us. As I approached the gangway, I saw on deck my late travelling companions, the Jewish man and his friend, regarding us with interest. Then, just as I was about to step on board, almost on the little man’s heels, there came a cry apparently from someone ahead: “Look out—gangway’s falling!”

In an instant all was confusion. The fat nurse behind me screamed, as the nervous fellow in front leaped like a cat, intent on saving himself no matter what happened to anyone else, and flung me against the woman with the baby. Two or three excitable Frenchmen just ahead also attempted to turn, thus nearly throwing the little man onto his knees. The large bag which he carried hit me across the shins; in his terror he almost embraced me as he helped himself up: the nurse, as she stumbled, pitched forward onto my shoulder, and if I had not seized the howling baby, it would certainly have fallen under our feet.

My bowler was knocked over my eyes, and though an officer of the boat cried the reassuring intelligence that it was a false alarm—that the gangway was “all right,” and never had been anything but all right, I could not readjust my hat nor see what was going on until the fat nurse had obligingly retrieved her charge, without a word of thanks.

My first thought was for the letter-case in my pocket, for I had a horrible idea that the scare might have been got up for the express purpose of robbing me of it. But I could feel its outline as plainly as ever under my coat, and decided, thankfully, that after all the alarm had had nothing to do with me.

I had wired for a private cabin, thinking it would be well to be out of the way of my fellow-passengers during the crossing: but the weather had been rough for a day or two (it was not yet the middle of April) and everything was already engaged; therefore I walked the deck most of the time, always conscious of the unusual thickness of my breast pocket. The little man paced up and down, too, though his yellow face grew slowly green, and he would have been much better off below, lying on his back. As for the two others, they also remained on deck, talking together as they leaned against the rail; but though I passed them now and again, I noticed that the little man invariably avoided them by turning before he reached their “pitch.”

At the Gare du Nord I regretted that I had not carried my own bag, because if I had it would have been examined on the boat, and all bother would have been over. But rather than run any risks in the crowd thronging the douane, I decided to let the suitcase look after itself, and send down for it with the key from the hotel later. Again the little man was close to my side as I went in search of a cab, for all his things had been gone through by the custom house officer in mid-channel, so that he too was free to depart without delay. He even seemed to cling to me, somewhat wistfully, and I half thought he meant to speak, but he did not, save for a “good evening, sir,” as I separated myself from him at last. He had stuck rather too close, elbow to elbow; but I had no fear for the letter-case, as he was on the wrong side to play any conjurer’s tricks with that. The last I saw of the fellow, he was walking toward a cab, and looking uneasily over his shoulder at his two late travelling companions, who were getting into another vehicle near by.

I went straight to the Élysée Palace Hotel, where I had never stopped before—a long drive from the Gare du Nord—and claimed the rooms for which “Mr. George Sandford” had wired from London. The suite engaged was a charming one, and the private salon almost worthy to receive the lovely lady I expected. Nor did she keep me waiting. I had had time only to give instructions about sending a man with a key to the station for my luggage, to say that a lady would call, to reach my rooms, and to draw the curtains over the windows, when a knock came at the salon door. I was in the act of turning on the electric light when this happened, but to my surprise the room remained in darkness—or rather, in a pink dusk lent by the colour of the curtains.

“The lady has arrived, Monsieur,” announced the servant. “As Monsieur expected her, she has come up without waiting; but I regret that something has gone wrong with the electricity, all over the hotel. It was but just now discovered, at time for turning on the lights, otherwise lamps and plenty of candles would have been provided, though no doubt the light will fonctionne properly in a few minutes. If Monsieur permits, I will instantly bring him a lamp.”

“No, thank you,” I said hurriedly, for I did not wish to be interrupted in the midst of my important interview with Maxine. “If the light comes on, it will he all right: if not, I will put back the curtains; and it is not yet quite dark. Show the lady in.”

Into the pink twilight of the curtained room came Maxine de Renzie, whose tall and noble figure I recognised in its plain, close-fitting black dress, though her wide brimmed hat was draped with a thickly embroidered veil that completely hid her face, while long, graceful lace folds fell over and obscured the bright auburn of her hair.

“One moment,” I said. “Let me push the curtains back. The electricity has failed.”

“No, no,” she answered. “Better leave them as they are. The lights may come on and we be seen from outside. Why,”—as she drew nearer to me, and the servant closed the door, “I thought I recognised that voice! It is Ivor Dundas.”

“No other,” said I. “Didn’t the—weren’t you warned who would be the man to come?”

“No,” she replied. “Only the assumed name of the messenger and place of meeting were wired. It was safer so, even though the telegram was in a cypher which I trust nobody knows—except myself and one other. But I’m glad—glad it’s you. It was clever of—him, to have sent you. No one would dream that—no one would think it strange if they knew—as I hope they won’t—that you came to Paris to see me. Oh, the relief that you’ve got through safely! Nothing has happened? You have—the paper?”

“Nothing has happened, and I have the paper,” I reassured her. “No adventures, to speak of, on the way, and no reason to think I’ve been spotted. Anyway, here I am; and here is something which will put an end to your anxiety.” And I tapped the breast of my coat, meaningly.

“Thank God!” breathed Maxine, with a thrilling note in her voice which would have done her great credit on the stage, though I am sure she was never further in her life from the thought of acting. “After all I’ve suffered, it seems too good to be true. Give it to me, quick, Ivor, and let me go.”

“I will,” I said. “But you might seem to take just a little more interest in me, even if you don’t really feel it, you know. You might just say, ‘How have you been for the last twelve months?’”

“Oh, I do take an interest, and I’m grateful to you—I can’t tell you how grateful. But I have no time to think either of you or myself now,” she said, eagerly. “If you knew everything, you’d understand.”

“I know practically nothing,” I confessed; “still, I do understand. I was only teasing you. Forgive me. I oughtn’t to have done it, even for a minute. Here is the letter-case which the Foreign—which was given to me to bring to you.”

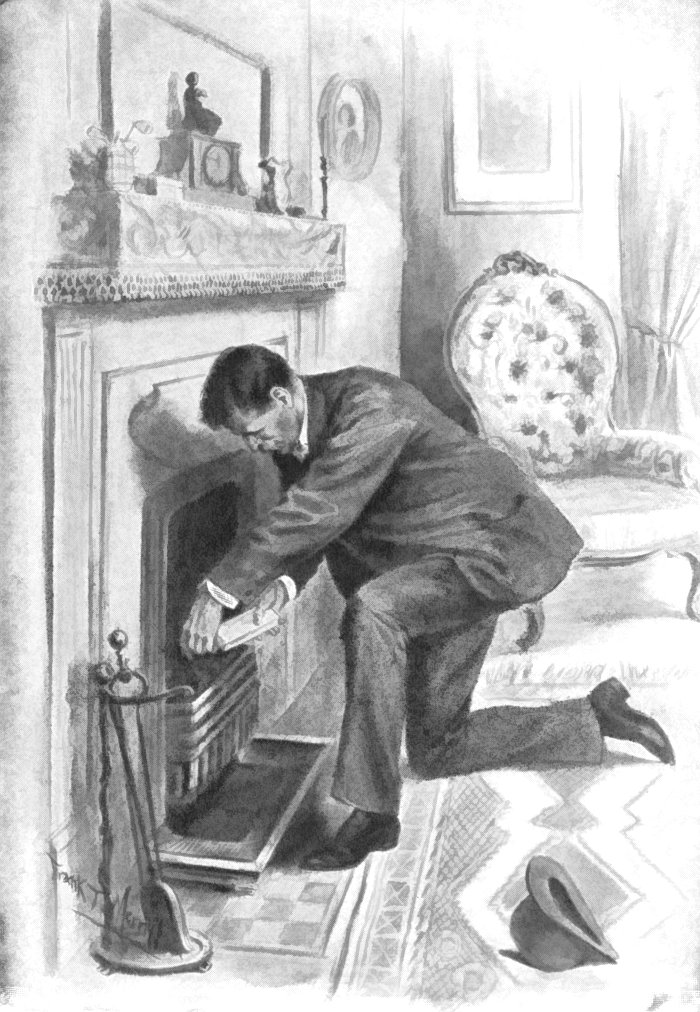

“Wait!” she exclaimed, still in the half whisper from which she had never departed. “Wait! It will he better to lock the door.” But even as she spoke, there came a knock, loud and insistent. With a spring, she flung herself on me, her hand fumbling for the pocket I had tapped suggestively a moment ago. I let her draw out the long case which I had been guarding—the case I had not once touched since leaving London, except to feel anxiously for its outline through my buttoned coat. At least, whatever might be about to happen, she had it in her own hands now.

Neither of us spoke nor made a sound during the instant that she clung to me, the faint, well-remembered perfume of her hair, her dress, in my nostrils. But as she started away, and I knew that she had the letter-case, the knock came again. Then, before I could be sure whether she wished for time to hide, or whether she would have me cry “come in,” without seeming to hesitate, the door opened. For a second or two Maxine and I, and a group of figures at the door were mere shadows in the ever deepening pink dusk: but I could scarcely have counted ten before the long expected light sprang up. I had turned it on in more than one place: and a sudden, brilliant illumination showed me a tall Commissary of Police, with two little gendarmes looking over his shoulder.

I threw a glance at Maxine, who was still veiled, and was relieved to see that she had found some means of putting the letter-case out of sight. Having ascertained this, I sharply enquired in French what in the devil’s name the Commissary of Police meant by walking into an Englishman’s room without being invited; and not only that, but what under heaven he wanted anyway.

He was far more polite than I was.

“Ten thousand pardons, Monsieur,” he apologised. “I knocked twice, but hearing no answer, entered, thinking that perhaps, after all, the salon was unoccupied. Important business must be my excuse. I have to request that Monsieur Dundas will first place in my hands the gift he has brought from London to Mademoiselle de Renzie.”