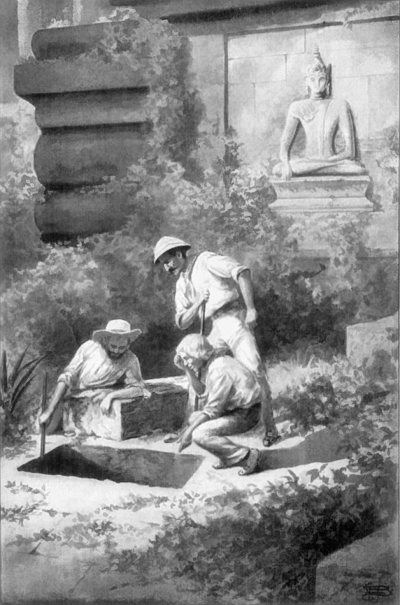

"A DARK, NARROW HOLE, THE BOTTOM OF WHICH IT WAS IMPOSSIBLE TO SEE."

Title: My Strangest Case

Author: Guy Boothby

Release date: January 1, 2004 [eBook #10585]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Susan Woodring and PG Distributed

Proofreaders

My Strangest Case |

|

By

By Guy BoothbyAuthor of "Dr. Nikola," "The Beautiful White Devil," "Pharos, the Egyptian," etc. |

|

Illustrated by

L.J. Bridgman and P. Hard |

Originally Published 1901. |

"A DARK, NARROW HOLE, THE BOTTOM OF WHICH IT WAS IMPOSSIBLE TO SEE."

" 'LOOK HERE,' HE CRIED, 'IT'S THE BANK OF ENGLAND IN EACH HAND.' "

" 'POOR DEVIL,' SAID GREGORY. 'HE SEEMS TO BE ON HIS LAST LEGS.' "

"HE FELL WITH A CRASH AT MY FEET."

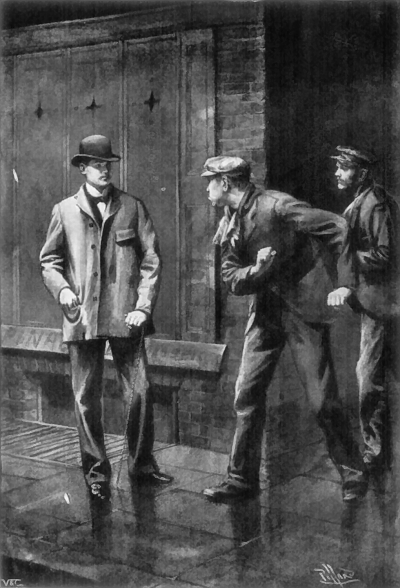

" 'LET'S OUT HIM, BILL,' SAID THE TALLER OF THE TWO MEN."

" 'HOW DO YOU DO, MR. FAIRFAX?' SAID MISS KITWATER."

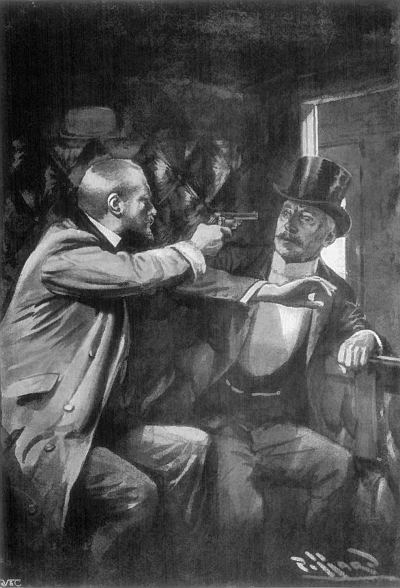

"IN HIS HAND HE HELD A REVOLVER."

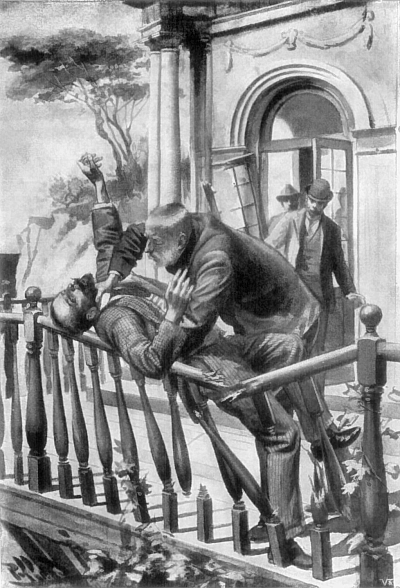

"THE WOODWORK SNAPPED, AND THE TWO MEN FELL OVER THE EDGE."

I am of course prepared to admit that there are prettier places on the face of this earth of ours than Singapore; there are, however, I venture to assert, few that are more interesting, and certainly none that can afford a better study of human life and character. There, if you are so disposed, you may consider the subject of British Rule on the one hand, and the various aspects of the Chinese question on the other. If you are a student of languages you will be able to hear half the tongues of the world spoken in less than an hour's walk, ranging say from Parisian French to Pigeon English; you shall make the acquaintance of every sort of smell the human nose can manipulate, from the sweet perfume of the lotus blossom to the diabolical odour of the Durien; and every sort of cooking from a dainty vol-au-vent to a stuffed rat. In the harbour the shipping is such as, I feel justified in saying, you would encounter in no other port of its size in the world. It comprises the stately man-of-war and the Chinese Junk; the P. and O., the Messagerie Maritime, the British India and the Dutch mail-boat; the homely sampan, the yacht of the globe-trotting millionaire, the collier, the timber-ship, and in point of fact every description of craft that plies between the Barbarian East and the Civilized West. The first glimpse of the harbour is one that will never be forgotten; the last is usually associated with a desire that one may never set eyes on it again. He who would, of his own free will, settle down for life in Singapore, must have acquired the tastes of a salamander, and the sensibility of a frog.

Among its other advantages, Singapore numbers the possession of a multiplicity of hotels. There is stately Raffles, where the globe-trotters do mostly take up their abode, also the Hôtel de l'Europe, whose virtues I can vouch for; but packed away in another and very different portion of the town, unknown to the wealthy G.T., and indeed known to only a few of the white inhabitants of Singapore itself, there exists a small hostelry owned by a lynx-eyed Portuguese, which rejoices in the name of the Hotel of the Three Desires. Now, every man, who by mischance or deliberate intent, has entered its doors, has his own notions of the meaning of its name; the fact, however, remains that it is there, and that it is regularly patronized by individuals of a certain or uncertain class, as they pass to and fro through the Gateway of the Further East. This in itself is strange, inasmuch as it is said that the proprietor rakes in the dollars by selling liquor that is as bad as it can possibly be, in order that he may get back to Lisbon before he receives that threatened knife-thrust between the ribs which has been promised him so long. There are times, as I am unfortunately able to testify, when the latter possibility is not so remote as might be expected. Taken altogether, however, the Hotel of the Three Desires is an excellent place to take up one's abode, provided one is not desirous of attracting too much attention in the city. As a matter of fact its patrons, for some reason of their own, are more en evidence after nightfall than during the hours of daylight. They are also frugal of speech as a rule, and are chary of forming new acquaintances. When they know each other well, however, it is surprising how affable they can become. It is not the smallest of their many peculiarities that they seldom refer to absent friends by their names. A will ask B when he expects to hear from Him, and C will inform D that "the old man is now running the show, and that, if he doesn't jump from Calcutta inside a week, there will be trouble on the floor." Meanwhile the landlord mixes the drinks with his own dirty hands, and reflects continually upon the villainy of a certain American third mate, who having borrowed five dollars from him, was sufficiently ungrateful as to catch typhoid fever and die without either repaying the loan, or, what was worse, settling his account for the board and lodging received. Manuel, for this was the proprietor's name, had one or two recollections of a similar sort, but not many, for, as a rule, he is a careful fellow, and experience having taught him the manners and idiosyncrasies of his customers, he generally managed to emerge from his transactions with credit to himself, and what was of much more importance, a balance on the right side of his ledger.

The time of which I am now writing was the middle of March, the hottest and, in every respect, the worst month of the year in Singapore. Day and night the land was oppressed by the same stifling heat, a sweltering calidity possessing the characteristics of a steam-laundry, coupled with those of the stokehole of an ocean liner in the Red Sea. Morning, noon, and night, the quarter in which the Hotel of the Three Desires was situated was fragrant with the smell of garbage and Chinese tobacco; a peculiar blend of perfume, which once smelt is not to be soon forgotten. Everything, even the bottles on the shelves in the bar, had a greasy feel about them, and the mildew on one's boots when one came to put them on in the morning, was a triumph in the way of erysiphaceous fungi. Singapore at this season of the year is neither good for man nor beast; in this sweeping assertion, of course I except the yellow man, upon whom it seems to exercise no effect whatsoever.

It was towards evening, and, strange to relate, the Hotel of the Three Desires was for once practically empty. This was the more extraordinary for the reason that the customers who usually frequented it, en route from one end of the earth to the other, are not affected by seasons. Midwinter was to them the same as midsummer, provided they did their business, or got their ships, and by those ships, or that business, received their wages. That those hard-earned wages should eventually find themselves in the pocket of the landlord of the Three Desires, was only in the natural order of things, and, in consequence, such of his guests as were sailors, as a general rule, eventually boarded their ships without as much as would purchase them a pipe of tobacco. It did not, however, prevent them from returning to the Hotel of the Three Desires when next they happened to be that way. If he had no other gift, Manuel at least possessed the faculty of making it comparatively homelike to his customers, and that is a desideratum not to be despised even by sailor men in the Far East.

As I have said, night was falling on one of the hottest days of the year, when a man entered the hotel and inquired for the proprietor. Pleased to find that there was at last to be a turn in the tide of his affairs, the landlord introduced himself to the stranger, and at the same time inquired in what way he could have the pleasure of serving him.

"I want to put up with you," said the stranger, who, by the way, was a tall man, with a hawk's eye and a nose that was not unlike the beak of the same bird. "You are not full, I suppose?"

Manuel rubbed his greasy hands together and observed that he was not as full as he had been; thereby insinuating that while he was not overflowing, he was still not empty. It will be gathered from this that he was a good business man, who never threw a chance away.

"In that case, I'll stay," said the stranger, and set down the small valise he carried upon the floor.

From what I have already written, you will doubtless have derived the impression that the Hotel of the Three Desires, while being a useful place of abode, was far from being the caravanserai of the luxurious order. The stranger, whoever he might be, however, was either not fastidious, or as is more probable, was used to similar accommodation, for he paid as little attention to the perfume of the bar as he did to the dirt upon the floor and walls, and also upon the landlord's hands. Having stipulated for a room to himself, he desired to be shown to it forthwith, whereupon Manuel led him through the house to a small yard at the back, round which were several small cabins, dignified by the name of apartments.

"Splendeed," said Manuel enthusiastically, throwing open the door of one of the rooms as he spoke. "More splendeed than ever you saw."

The stranger gave a ravenish sort of croak, which might have been a laugh or anything else, and then went in and closed the door abruptly behind him. Having locked it, he took off his coat and hung it upon the handle, apparently conscious of the fact that the landlord had glued his eyes to the keyhole in order that he might, from a precautionary point of view, take further stock of his patron. Foiled in his intention he returned to the bar, murmuring "Anglish Peeg" to himself as he did so. In the meantime the stranger had seated himself upon the rough bed in the corner, and had taken a letter from his pocket.

"The Hotel of the Three Desires," he reads, "and on March the fifteenth, without fail." There was a pause while he folded the letter up and placed it in his pocket. Then he continued, "this is the hotel, and to-day is the fifteenth of March. But why don't they put in an appearance. It isn't like them to be late. They'd better not play me any tricks or they'll find I have lost none of my old power of retaliation."

Having satisfied himself that it was impossible for any one to see into the room, either through the keyhole or by means of the window, he partially disrobed, and, when he had done so, unbuckled from round his waist a broad leather money-belt. Seating himself on the bed once more he unfastened the strap of the pocket, and dribbled the contents on to the bed. They consisted of three Napoleons, fifteen English sovereigns, four half-sovereigns, and eighteen one-franc pieces. In his trouser-pocket he had four Mexican dollars, and some cosmopolitan change of small value.

"It's not very much," he muttered to himself after he had counted it, "but it ought to be sufficient for the business in hand. If I hadn't been fool enough to listen to that Frenchwoman on board, I shouldn't have played cards, and then it would have been double. Why the deuce wasn't I able to get Monsieur ashore? In that case I'd have got it all back, or I'd have known the reason why."

The idea seemed to afford him some satisfaction, for he smiled, and then said to himself as if in terms of approbation, "By Jove, I believe you, my boy!"

When he had counted his money and had returned it once more to its hiding-place, he buckled the belt round his person and unstrapped his valise, taking from it a black Tussa coat which he exchanged for that hanging upon the handle of the door. Then he lighted a Java cigar and sat down upon the bed to think. Taken altogether, his was not a prepossessing countenance. The peculiar attributes I have already described were sufficient to prevent that. At the same time it was a strong face, that of a man who was little likely to allow himself to be beaten, of his own free will, in anything he might undertake. The mouth was firm, the chin square, the eyes dark and well set, moreover he wore a heavy black moustache, which he kept sharp-pointed. His hair was of the same colour, though streaked here and there with grey. His height was an inch and a half above six feet, but by reason of his slim figure, he looked somewhat taller. His hands and feet were small, but of his strength there could be no doubt. Taken altogether, he was not a man with whom one would feel disposed to trifle. Unfortunately, however, the word adventurer was written all over him, and, as a considerable section of the world's population have good reason to know, he was as little likely to fail to take advantage of his opportunities as he was to forget the man who had robbed him, or who had done him an ill turn. It was said in Hong Kong that he was well connected, and that he had claims upon a Viceroy now gone to his account; that, had he persevered with them, might have placed him in a very different position. How much truth there was in this report, however, I cannot say; one thing, however, is quite certain; if it were true, he had fallen grievously from his high estate.

When his meditations had continued for something like ten minutes, he rose from the bed, blew a cloud of smoke, stretched himself, strapped his valise once more, gave himself what the sailors call a hoist, that he might be sure his money-belt was in its proper position, and then unlocked the door, passed out, re-locked it after him, and returned to the bar. There he called for certain curious liquors, smelt them suspiciously before using them, and then proceeded deliberately to mix himself a peculiar drink. The landlord watched him with appreciative surprise. He imagined himself to be familiar with every drink known to the taste of man, having had wide experience, but such an one as this he had never encountered before.

"What do you call it?" he asked, when the other had finished his preparations.

"I call it a 'Help to Reformation,' " the stranger replied. Then, with a sneer upon his face, he added, "It should be popular with your customers."

Taking the drink with him into the verandah outside, he seated himself in a long chair and proceeded to sip it slowly, as if it were some elixir whose virtue would be lost by haste. Some people might have been amused by the motley crowd that passed along the street beyond the verandah-rails, but Gideon Hayle, for such was his name, took no sort of interest in it. He had seen it too often to find any variety in it. As a matter of fact the mere sight of a pigtail was sufficient to remind him of a certain episode in his career which he had been for years endeavouring to forget.

"It doesn't look as if they are going to put in an appearance to-night," he said to himself, as the liquor in the glass began to wane. "Can this letter have been a hoax, an attempt to draw me off the scent? If so, by all the gods in Asia, they may rest assured I'll be even with them."

He looked as though he meant it!

At last he rose, and having returned his glass to the bar, donned his topee, left the hotel, and went for a stroll. It was but a short distance to the harbour, and he presently found himself strolling along the several miles of what I have already described as the most wonderful shipping in the world. To Mr. Hayle the scene was too familiar to call for comment. He had seen it on many occasions, and under a variety of auspices. He had witnessed it as a deck-hand and as a saloon passenger; as a steerage passenger, and in the humble capacity of a stowaway. Now he was regarding it as a gentleman of leisure, who smoked a cigar that had been paid for, and round whose waist was a belt with gold in it. Knowing the spot where the British India boats from Calcutta usually lie, he made his way to it, and inquired for a certain vessel. She had not yet arrived, he was informed, and no one seemed to know when she might be expected. At last, tired of his occupation, he returned to his hotel, and in due course sat down to supper. He smoked another cigar in the verandah afterwards, and was on the point of retiring for the night, when two men suddenly made their appearance before him, and accosted him by name. He immediately sprang to his feet with a cry of welcome.

"I had made up my mind that you were not coming," he said as they shook hands.

"The old tub didn't get in until a quarter to nine," the taller of the two new-comers replied. "When did you arrive?"

"This afternoon," said Hayle, and for a moment volunteered no further information. A good poker-player is always careful not to show his hand.

"I suppose this place is not full?" inquired the man who had last spoken.

"Full?" asked Hayle scornfully. "It's full of cockroaches and mildew, if that's what you mean?"

"The best company we could possibly have," said the taller man. "Cockroaches and blackbeetles don't talk and they don't listen at keyholes. What's more, if they trouble you, you can put your heel on them. Now let's see the landlord and see what he's got to offer us in the way of rooms. We don't want any dinner, because we had it on board the steamer."

Hayle accompanied them into the bar, and was a witness of the satisfaction the landlord endeavoured, from business motives, to conceal. In due course he followed them to the small, stifling rooms in the yard at the back, and observed that they were placed on either side of himself. He had already taken the precaution of rapping upon the walls in order to discover their thickness, and to find out whether the sound of chinking money was to be heard through them.

"I must remember that thirty-seven and sixpence and two Mexican dollars are all I have in the world," he said to himself. "It would be bad business to allow them to suppose that I had more, until I find out what they want."

"The last time I was here was with Stellman," said the taller of the men, when they met again in the courtyard. "He had got a concession from the Dutch, so he said, to work a portion of the West Coast for shell. He wanted me to go in with him."

"And you couldn't see your way to it?"

"I've seen two Dutch gaols," said the other; "and I have no use for them."

"And what happened to Stellman?" asked Hayle, but without any apparent interest. He was thinking of something else at the time.

"They got his money, his boat, and his shell, with three pearls that would have made your mouth water," replied the other.

"And Stellman?"

"Oh, they buried him at Sourabaya. He took the cholera, so they said, but I have heard since that he died of starvation. They don't feed you too well in Dutch gaols, especially when you've got a concession and a consul."

The speaker looked up at his companion as he said this, and the other, who, as I have already said, was not interested in the unfortunate Stellman, or had probably heard the tale before, nodded his head in the direction of the room where the smaller man was engaged on his toilet, to the accompaniment of splashing water. The movement of the head was as significant as the nod of the famous Lord of Burleigh.

"Just the same, as ever," the other replied. "Always pushing his nose into old papers and documents, until you'd think he'd make himself ill. Lord, what a man he would have been for the British Museum! There's not his equal on Ancient Asia in the world."

"And this particular business?"

"Ah, you shall hear all about it in the proper time. That'll be to-morrow morning, I reckon. In the meantime you can go to bed, and content yourself with the knowledge that, all being well, you're going to play a hand in the biggest scoop that ever I or anybody else have tackled?"

"You can't give me an inkling of what it is to-night, I suppose?"

"I could, but I'm not going to," replied his companion calmly. "The story would take too long to tell, and I'm tired. Besides, you would want to ask questions of Coddy, and that would upset the little man's equilibrium. No! Go to bed and have a good night's rest, and we'll talk it over in the morning. I wonder what my curtains are like? If ever there's a place in this world for mosquitoes, it's Singapore, and I thought Calcutta was bad enough."

Having no desire to waste time in discussing the various capabilities of this noxious insect, Hayle bade the other good-night, and, when he had visited the bar and had smoked another cigar, disappeared in the direction of his own apartment.

Meanwhile Mr. Kitwater, for such was the name of the gentleman he had just left, had begun his preparations for the night, vigorously cursing the mosquitoes as he did so. He was a fine-looking man, with a powerful, though somewhat humorous cast of countenance. His eyes were large, and not unkindly. His head was a good one from a phrenological point of view, but was marred by the possession of enormous ears which stood out on either side of his head like those of a bat. He wore a close-cropped beard, and he was famous for his strength, which indeed was that of a giant.

"Hayle, if I can sum it up aright, is just the same as ever," he said as he arranged the mosquito-netting of his bed. "He doesn't trust me, and I don't trust him. But he'll be none the less useful for that. Let him try to play me false, and by the Lord Harry, he'll not live to do it again."

With this amiable sentiment Mr. Kitwater prepared himself for slumber.

Then, upon the three worthies the hot, tropical night settled down.

Next morning they met at breakfast. All three were somewhat silent. It was as if the weight of the matter which was that day to be discussed pressed upon their spirits. The smallest of the trio, Septimus Codd by name, who was habitually taciturn, spoke scarcely a word. He was a strange little man, a nineteenth century villain in a sense. He was a rogue and a vagabond, yet his one hobby, apart from his business, was a study of the Past, and many an authority on Eastern History would have been astonished at the extent of his learning. He was never so happy as when burrowing amongst ancient records, and it was mainly due to his learning in the first place, and to a somewhat singular accident in the second, that the trio were now foregathered in Singapore. His personal appearance was a peculiar one. His height was scarcely more than four feet six inches. His face was round, and at a distance appeared almost boyish. It was only when one came to look into it more closely, that it was seen to be scored by numberless small lines. Moreover it was unadorned by either beard or moustache. His hair was grey, and was worn somewhat longer than is usual. He could speak fluently almost every language of the East, and had been imprisoned by the Russians for sealing in prohibited waters, had been tortured by the Chinese on the Yang-tse, and, to his own unextinguishable disgrace, flogged by the French in Tonquin. Not the least curious trait in his character was the affection he entertained for Kitwater. The pair had been together for years, had quarrelled repeatedly, but had never separated. The record of their doings would form an interesting book, but for want of space cannot be more than referred to here. Hayle had been their partner in not a few of their curious undertakings, for his courage and resource made him a valuable ally, though how far they trusted each other it is impossible to say.

Breakfast over they adjourned to the verandah, where the inevitable cigars made their appearance.

"Now, let's hear what you've got to say to me?" Hayle began.

"Not here," Kitwater replied. "There are too many listeners. Come down to the harbour."

So saying he led his companions to the waterside, where he chartered a native boat for an hour's sail. Then, when they were out of earshot of the land, he bade Hayle pay attention to what he had to say.

"First and foremost you must understand," he said, "that it's all due to Coddy here. We heard something of it from an old Siamese in Hanoi, but we never put much trust in it. Then Coddy began to look around, to hunt up some of his fusty records, and after awhile he began to think that there might be something in the story after all. You see it's this way: you know Sengkor-Wat?"

"Sengkor how much?"

"Sengkor-Wat—the old ruin at the back of Burmah; near the Chinese Border. Such a place as you never dreamt of. Tumble-down palaces, temples, and all that sort of thing—lying out there all alone in the jungle."

"I've seen Amber," said Hayle, with the air of a man who makes a remark that cannot be lightly turned aside. "After that I don't want any more ruined cities. I've got no use for them."

"No, but you've got a use for other things, haven't you? You can use rubies as big as pigeon's eggs, I suppose. You've got a use for sapphires, the like of which mortal man never set eyes on before."

"That's certainly so," Hayle replied. "But what has this Sengkor-Wat to do with it?"

"Everything in the world," Kitwater replied. "That's where those rubies are, and what's more, that's where we are going to find them."

"Are you joking, or is this sober earnest?"

He looked from Kitwater to Codd. The little man thus appealed to nodded his head. He agreed with all his companion said.

"It's quite true," said he, after a pause. "Rubies, sapphires and gold, enough to make us all millionaires times over."

"Bravo for Sengkor-Wat, then!" said Hayle. "But how do you know all this?"

"I've told you already that Coddy found it out," Kitwater replied. "Looking over his old records he discovered something that put him on the track. Then I happened to remember that, years ago, when I was in Hanoi, an old man had told me a wonderful story about a treasure-chamber in a ruined city in the Burmese jungle. A Frenchman who visited the place, and had written a book about it, mentions the fact that there is a legend amongst the natives that vast treasure is buried in the ruins, but only one man, so far as we can discover, seems to have taken the trouble to have looked for it."

"But how big are the ruins?"

"Bigger than London, so Coddy says!"

Coddy nodded his head in confirmation of this fact. But still Hayle seemed incredulous.

"And are you going to search all that area? It strikes me that you will be an old man by the time you find the treasure, Kitwater."

"Don't you believe it. We've got something better to go upon than that. There was an old Chinese traveller who visited this place in the year ... what was the year, Coddy?"

"Twelve hundred and fifty-seven," Codd replied without hesitation.

"Well, he describes the glory of the place, the wealth of the inhabitants, and then goes on to tell how the king took him to the great treasure-chamber, where he saw such riches as mortal man had never looked upon before."

"But that doesn't tell you where the treasure-chamber is?" argued Hayle.

"Perhaps not, but there are other ways of finding out; that is, if a man has his wits about him. You've got to put two and two together if you want to get on in this world. Coddy has translated it all, and this is what it amounts to. When the king had shown the traveller his treasure, the latter declared that his eyes were so blinded by its magnificence that he could scarcely mount the steps to the spot where his majesty gave audience to his people. In another place it mentions that when the king administered justice he was seated on the throne in the courtyard of the Three-headed Elephants. Now what we've got to do is to find that courtyard, and find it we will."

"But how do you know that the treasure hasn't been taken away years ago? Do you think they were such fools as to leave it behind when they went elsewhere? Not they!"

Though they were well out of earshot of the land, and alone upon the boat, Kitwater looked round him suspiciously before he answered. Then a pleasant smile played over his face. It was as if he were recalling some happy memory.

"How do I know it?" he asked by way of preface. "If you'll listen for a moment, I'll tell you. If you want more proof, when I've done, you must be difficult to please. When I was up at Moulmein six months ago, I came across a man I hadn't met for several years. He was a Frenchman, who I knew had spent the most of his life away back in Burmah. He was very flush of money at the time, and kept throwing out hints, when we were alone, of a place he knew of where there was the biggest fortune on earth, to be had for the mere picking up and carrying away. He had brought away as much of it as he could, but he hadn't time to get it all, before he was chased out by the Chinese, who, he said, were strong in the neighbourhood."

Kitwater stopped and rubbed his hands with a chuckle. Decidedly the recollection was a pleasant one.

"Well," he continued, "to make a long story short, I took advantage of my opportunity, and got his secret out of him by ... well never mind how I managed it. It is sufficient that I got it. And the consequence is I know all that is to be known."

"That's all very well, but what became of the Frenchman? How do you know that he isn't back there again filling his pockets?"

"I don't think he is," Kitwater replied slowly. "It put me to a lot of inconvenience, and came just at the time when I was most anxious to leave. Besides it might have meant trouble." He paused for a moment. "As a matter of fact they brought it in 'suicide during temporary insanity, brought on by excessive drinking,' and that got me over the difficulty. It must have been insanity, I think, for he had no reason for doing away with himself. It was proved that he had plenty of money left. What was more, Coddy gave evidence that, only the day before, he had told him he was tired of life."

Hayle looked at both with evident admiration.

"Well, you two, taken together, beat cockfighting," he said enthusiastically. Then he added, "But what about the secret? What did you get out of him?"

"Here it is," said Kitwater, taking an old leather case from his pocket, and producing from it a small piece of parchment. "There's no writing upon it, but we have compared it with another plan that we happen to have, and find that it squares exactly."

He leant over Hayle's shoulder and pointed to a certain portion of the sketch.

"That's the great temple," he said; "and what the red dot means we are going to find out."

"Well, suppose it is, what makes you send for me?" Hayle inquired suspiciously.

"Because we must have another good man with us," Kitwater replied. "I'm very well, but you're better. Codd's head-piece is all right, but if it comes to fighting, he might just as well be in Kensal Green. Isn't that so, little man?"

Mr. Codd nodded his head.

"I said, send for Hayle," he remarked in his quiet little voice. "Kit sent and now you're here, and it's all right."

"Codd speaks the truth," said Kitwater. "Now what we have to do is to arrange the business part of the matter, and then to get away as quickly as possible."

The business portion of the matter was soon settled and Hayle was thereupon admitted a member of the syndicate for the exploration of the ancient town of Sengkor-Wat in the hinterland of Burmah.

For the remainder of the day Hayle was somewhat more silent than usual.

"If there's anything in their yarn it might be managed," he said to himself that night, when he was alone in his bedroom. "Kitwater is clever, I'll admit that, and Coddy is by no manner of means the fool he pretends to be. But I'm Gideon Hayle, and that counts for something. Yes, I think it might be managed."

What it was he supposed might be effected he did not say, but from the smile upon his face, it was evident that the thought caused him considerable satisfaction.

Next day they set sail for Rangoon.

The shadows of evening were slowly falling as the little party of which Kitwater, Codd, and Hayle, with two Burmen servants, were members, obtained their first view of the gigantic ruins of which they had come so far in search. For many days they had been journeying through the jungle, now the prey of hope, now of despair. They had experienced adventures by the score, though none of them were of sufficient importance to be narrated here, and more than once they had come within a hair's-breadth of being compelled to retrace their steps. They rode upon the small wiry ponies of the country, their servants clearing a way before them with their parangs as they advanced. Their route, for the most part, lay through jungle, in places so dense that it was well-nigh impossible for them to force a way through it. It was as if nature were doing her best to save the ancient city from the hand of the spoiler. At last, and so suddenly that it came upon them like a shock, they found themselves emerging from the jungle. Below them, in the valley, peering up out of the forest, was all that remained of a great city, upon the ruined temples of which the setting sun shone with weird effect.

"At last," said Hayle, bringing his pony to a standstill, and looking down upon the ruins. "Let us hope we shall have penetrated their secret before we are compelled to say good-bye to them again."

"Hear, hear, to that," said Kitwater; Septimus Codd, however, never said a word; the magic hand of the past was upon his heart, and was holding him spellbound.

They descended the hill, and, when they had selected a suitable spot, decided to camp upon it for the night.

Next morning they were up betimes; the excitement of the treasure-hunt was upon each man, and would not let him tarry. It would not be long now, they hoped, before they would be able to satisfy themselves as to the truth of the story they had been told, and of the value of the hopes in which they had put their trust. Having eaten their morning meal, they took counsel together, examined the plan for the thousandth time, collected their weapons and tools, bade their servants keep a sharp lookout, and then set off for the city. The morning sun sparkled upon the dew, the birds and monkeys chattered at them from the jungle, while above them towered the myriad domes and sculptured spires of the ancient city. It was a picture that once seen would never be forgotten. So far, however, not a sign of human life had they been able to discover; indeed, for all they knew to the contrary, they might be the only men within fifty miles of the place.

Leaving the jungle behind them, they found themselves face to face with a curious stone bridge, spanning the lake or moat which surrounded the city, and in which the lotus flower bloomed luxuriantly. When they had crossed the bridge, they stood in the precincts of the city itself. On either hand rose the ruins in all their solitary grandeur—palaces, temples, market-places, and houses in endless confusion; while, at the end of the bridge, and running to right and left as far as the eye could reach, was a high wall, constructed of large stones, each one of which would have required the efforts of at least four men to lift it. These, with a few exceptions, were in an excellent state of preservation. Passing through the massive gateway the travellers found themselves in an open square, out of which streets branched off the right and left, while the jungle thrust in its inquisitive nose on every possible occasion. The silence was so impressive that the men found themselves speaking in whispers. Not a sound was to be heard save the fluttering of birds' wings among the trees, and the obscene chattering of the monkeys among the leaves. From the first great square the street began gradually to ascend; then another moat was crossed, and the second portion of the city was reached. Here the buildings were larger, and the sculpture upon the walls more impressive even than before. The same intense silence, however, hung over everything. In the narrower streets creepers trailed from side to side, almost shutting out the light, and adding a twilight effect to the already sufficiently mysterious rooms and courtyards to be seen within.

"This is by no means the most cheerful sort of place," said Hayle to Kitwater, as they passed down a paved street side by side. "Where do you expect to find the great temple and the courtyard of the Three Elephants' Heads?"

"Straight on," said little Codd, who was behind, and had been comparing the route they were following with the plan he held in his hand.

As he spoke they entered another square, and saw before them a mighty flight of steps, worn into grooves in places by the thousands of feet that had ascended and descended them in days gone by. At the top was a sculptured gateway, finer than anything either of them had ever seen, and this they presently entered. Above them, clear of the trees, and towering up into the blue, were the multitudinous domes and spires of the king's palace, to which the gateway above the steps was the principal entrance. Some of the spires were broken, some were covered with creepers, others were mutilated by time and by stress of weather, but the general effect was grand in the extreme. From courtyard to courtyard they wandered, but without finding the particular place of which they were in search. It was more difficult to discover than they had expected; indeed, they had walked many miles through deserted streets, and the afternoon was well advanced, before a hail from Codd, who had gone on ahead of them, informed them that at last some sort of success had crowned their efforts. When they came up with him they found themselves in a courtyard somewhat larger than those they had previously explored, the four corners of which were decorated with three united elephants' heads.

"By the great poker we've got it at last," cried Kitwater, in a voice that echoed and reechoed through the silent halls.

"And about time, too," cried Hayle, upon whom the place was exercising a most curious effect. "If you've found it, show us your precious treasure-chamber."

"All in good time, my friend, all in good time," said Kitwater. "Things have gone so smoothly with us hitherto, that we must look for a little set-back before we've done."

"We don't want any set-backs," said Hayle. "What we want are the rubies as big as pigeon's eggs, and sapphires, and gold, and then to get back to civilization as quick as may be. That's what's the matter with me."

As I have already observed, the courtyard in which they were standing was considerably larger than any they had yet entered. Like the others, however, it had fallen sadly to decay. The jungle had crept in at all points, and gorgeous creepers had wreathed themselves round the necks of the statues above the gateway.

"I don't see any sign of steps," said Hayle, when they had examined the place in silence for some minutes. "I thought you said a flight of stone steps led up to where the king's throne was placed?"

"Codd certainly read it so," Kitwater answered, looking about him as if he did not quite realize the situation. "And how are we to know that there are not some steps here? They may be hidden. What do you think, little man?"

He turned to Codd, who was looking about him with eyes in which a curious light was shining.

"Steps must be somewhere," the latter replied. "We've got to find them—but not to-night. Sun going down. Too late."

This was undoubtedly true, and so, without more ado, but none the less reluctantly, the three travellers retraced their steps to their camp upon the hillside. Hayle was certainly not in a good temper. The monotony of the long journey from civilization had proved too much for him, and he was ready to take offence at anything. Fortunately, however, Kitwater was not of the same way of thinking, otherwise there would probably have been trouble between them.

Next morning they were up and had breakfasted before the sun was in the sky. Their meal at an end, they picked up their arms and tools, bade their servants have a care of the camp, and then set off on their quest once more. There was a perceptible change, however, in their demeanours. A nervous excitement had taken possession of them, and it affected each man in a different manner. Kitwater was suspicious, Hayle was morose, while little Codd repeatedly puckered up his mouth as if he were about to whistle, but no sound ever came from it. The sky overhead was emerald-blue, the air was full of the sweetest perfumes, while birds of the most gorgeous plumage flew continually across their path. They had no regard, however, for nature's beauties. The craving for wealth was in their hearts, rendering them blind to everything else. They crossed the stone bridge, passed through the outer portion of the city, proceeded over the second moat, and at last, with the familiarity of old friends, made their way up the steps towards the courtyard of the king's palace.

"Now, my friends, listen to me," said Kitwater, as he spoke throwing down the tools he had been carrying, "what we have to do is to thoroughly sound the whole of this courtyard, inch by inch and stone by stone. We can't be wrong, for that this is the courtyard of the Three Elephants' Heads, there can be no doubt. You take the right-hand side," he went on addressing Hayle; "you, Coddy, must take the left. I'll try the middle. If we don't hit it to-day we'll do so to-morrow, or the next day, or the day after that. This is the place we were told about, and if the treasure is to be found anywhere, it will be here. For that reason we've got to set about the search as soon as possible! Now to work!"

Using the iron bars they had brought with them for the purpose, they began their task, bumping the iron down upon each individual stone in the hope of eliciting the hollow sound that was to reveal the presence of the treasure-chamber. With the regularity of automatons they paraded up and down the walled enclosure without speaking, until they had thoroughly tested every single stone; no sort of success, however, rewarded their endeavours.

"I expected as much," said Hayle angrily, as he threw down the bar. "You've been humbugged, and our long journey is all undertaken for nothing. I was a fool ever to have listened to your nonsensical yarn. I might have known it would have come to nothing. It's not the first time I've been treasure-hunting, but I'll swear it shall be the last. I've had enough of these fooleries."

A dangerous light was gathering in Kitwater's eyes. He moreover threw down the iron bar as if in anticipation of trouble, and placed his fists defiantly on his hips.

"If you are going to talk like that, my boy," he began, with never a quaver in his voice, "it's best for us to understand each other straight off. Once and for all let me tell you that I'll have none of your bounce. Whether or not this business is destined to come to anything, you may rely upon one thing, and that is the fact that I did my best to do you a good turn by allowing you to come into it. There's another thing that calls for comment, and you can deny it if you will. It's a fact that you've been grumbling and growling ever since we left Rangoon, and have made difficulties innumerable where you needn't have done so, and now, because you think the affair is going to turn out badly, you round upon me as if it were all a put-up job on my part, to rook you of your money. It's not the thing, Hayle, and I don't mind saying that I resent it."

"You may resent it or not, as you darned well please," said Hayle doggedly, biting at the butt of his cigar as he spoke. "It don't matter a curse to me; you don't mean to tell me you think I'm fool enough to stand by and see myself----"

At that moment Codd, who had been away investigating on his own account, and had no idea of the others' quarrel, gave a shout of delight. He was at the further end of the courtyard, at a spot where a dense mass of creeper had fallen, and now lay trailing upon the stones. The effect upon his companions was instantaneous. They abandoned their quarrel without another word, and picking up their crowbars hastened towards the spot where he was waiting for them.

"What have you found, little man?" inquired Kitwater, as he approached.

Mr. Codd, however, said nothing in reply, but beat with his bar upon the stone beneath him. There could be little or no doubt about the hollow sound that rewarded his endeavours.

"We've got it," cried Kitwater. "Bring the pickaxe, Hayle, and we'll soon see what is underneath this precious stone. We may be at the heart of the mystery for all we know."

In less time than it takes to tell Hayle had complied with the other's request, and was hard at work picking out the earth which held the enormous flagstone in its place. A state of mad excitement had taken hold of the men, and the veins stood out like whipcord upon Hayle's forehead. It was difficult to say how many feet separated them from the treasure that was to make them lords of all the earth. At last the stone showed signs of moving, and it was possible for Kitwater to insert his bar beneath one corner. He did so, prized it up, and leant upon it with all his weight. It showed no sign of moving, however. The seal of Time was set upon it, and it was not to be lightly disturbed.

"Push your bar in here alongside of mine, Coddy," said Kitwater at last. "I fancy we shall get it then."

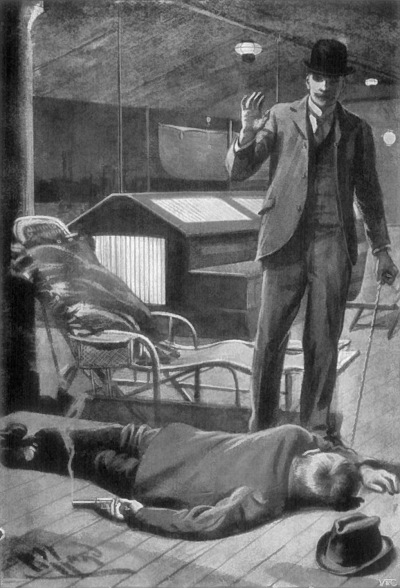

"A DARK, NARROW HOLE, THE BOTTOM OF WHICH IT WAS IMPOSSIBLE TO SEE."

The little man did as he was directed, Kitwater and Hayle seconded his efforts on the other side, and then, under the strain of their united exertions, the stone began to move slowly from its place. Little by little they raised it, putting all the strength they possessed into the operation, until, at last, with one great effort they hurled it backwards, and it fell with a crash upon the pavement behind them, revealing a dark, narrow hole, the bottom of which it was impossible to see.

"Now then, Gideon, my worthy friend, what have you got to say about the business?" asked Kitwater, as he wiped the perspiration from his brow. "You pretended to doubt my story. Was there anything in the old Frenchman's yarn after all. Were we wasting our time upon a fool's errand when we set off to explore Sengkor-Wat?"

Hayle looked at him somewhat sheepishly.

"No? no," he said, "I am willing to admit that so far you have won the trick. Let me down easily if you can. I can neither pass nor follow suite. I am right out of my reckoning. Now what do you propose to do?"

"Get one of those torches we brought with us, and find out what there is in that hole," Kitwater answered.

They waited while the latter went back to the camp, and when he reappeared, and had lighted the torch, they prepared to follow him down the steps into the mysterious depths below. The former, they soon discovered, were as solidly built as the rest of the palace, and were about thirty in number. They were, moreover, wet and slimy, and so narrow that it was only possible for one man to descend them at once. When they reached the bottom they found themselves standing in a narrow passage, the walls of which were composed of solid stone, in many places finely carved. The air was close, and from the fact that now and again bats dashed past them into the deeper darkness, they argued that there must be some way of communicating with the open air at the further end.

"This is just what the Frenchman told me," said Kitwater, and his voice echoed away along the passage like distant thunder. "He said we should find a narrow corridor at the foot of the steps, and then the Treasure Chamber at the further end. So far it looks all right. Let us move on, my friends."

There was no need for him to issue such an invitation. They were more than eager to follow him.

Leaving the first room, or ante-chamber, as it might more properly be called, they continued their way along the narrow passage which led from it. The air was growing perceptibly closer every moment, while the light of the torch reflected the walls on either side. Hayle wondered for a moment as he followed his leader, what would happen to them if the Chinese, of whom the old Frenchman had spoken to Kitwater, should discover their presence in the ruins, and should replace the stone upon the hole. In that case the treasure would prove of small value to them, for they would be buried alive. He did not allow his mind, however, to dwell very long upon this subject, for Kitwater, who was pushing on ahead with the torch, had left the passage, and was standing in a large and apparently well vaulted chamber. Handsomely carved pillars supported the roof, the floor was well paved, while on either side there were receptacles, not unlike the niches in the Roman catacombs, though for what purpose they were intended was not at first glance so easy to determine. With hearts that beat tumultuously in their breasts, they hastened to one of them to see what it contained. The niche in question was filled with strange-looking vessels, some like bowls, and others not unlike crucibles. The men almost clambered over each other in their excitement to see what they contained. It was as if their whole existence depended upon it; they could scarcely breathe for excitement. Every moment's delay was unspeakable agony. At last, however, the coverings were withdrawn and the contents of the receptacles stood revealed. Two were filled with uncut gems, rubies and sapphires, others contained bar gold, and yet more contained gems, to which it was scarcely possible in such a light to assign a name. One thing at least was certain. So vast was the treasure that the three men stood tongue-tied with amazement at their good fortune. In their wildest dreams they had never imagined such luck, and now that this vast treasure lay at their finger-ends, to be handled, to be made sure of, they were unable to realize the extent of their future happiness. Hayle dived his hands into a bowl of uncut rubies, and having collected as many as he could hold in each fist, turned to his companions.

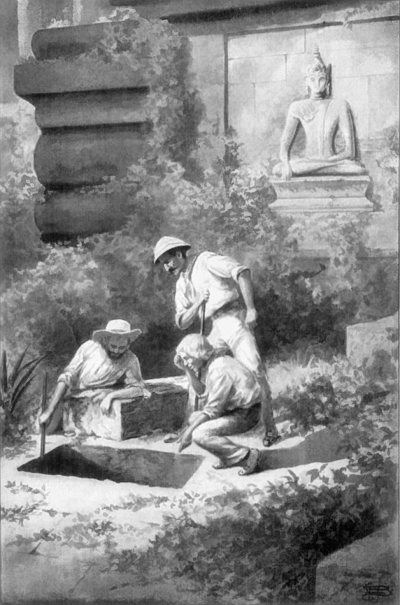

" 'LOOK HERE,' HE CRIED, 'IT'S THE BANK OF ENGLAND IN EACH HAND.' "

"Look here," he cried, "it's the Bank of England in each hand."

His voice ended in a choke. Then Kitwater took up the tale.

"I must get out of this or I shall go mad," he muttered hoarsely. "Come let us get back to the light. If I don't I shall die."

Without more ado, like men who were drunk with the finest wines, they followed him along the passage and up the steps into the open air. They were just in time to see the sun setting blood-red behind the jungle. His beauty, however, had no effect upon them, in all probability they were regardless of him altogether, for with almost simultaneous sighs of relief they threw themselves down upon the flagstones of the courtyard, and set to work, with feverish earnestness, to overhaul the booty they had procured. All three were good judges of stones, and a very brief examination was sufficient, even in the feeble evening light, to enable them to see that they were not only gems of the first water, but also stones of such a size as is seldom seen in these unregenerate days.

"It's the biggest scoop on earth," said Hayle, unconsciously echoing the expression Kitwater had used to him in Singapore. "What's better, there are hundreds more like them down below. I'll tell you what it is, my friends, we're just the richest men on this earth at the present moment, and don't you forget it!"

In his excitement he shook hands wildly with his companions. His ill-humour had vanished like breath off a razor, and now he was on the best of terms not only with himself, but also with the world in general.

"If I know anything about stones there are at least one hundred thousand pounds worth in this little parcel," he said enthusiastically, "and what is more, there is a million or perhaps two millions to be had for the trouble of looking for them. What do you say if we go below again?"

"No! no!" said Kitwater, "it's too late. We'd better be getting back to the camp as soon as may be."

"Very well," Hayle replied reluctantly.

They accordingly picked up their iron bars and replaced the stone that covered the entrance to the subterranean passage.

"I don't like leaving it," said Hayle, "it don't seem to me to be safe, somehow. Think what there is down there. Doesn't it strike you that it would be better to fill our pockets while we've the chance? Who knows what might happen before we can come again?"

"Nonsense," said Kitwater. "Who do you think is going to rob us of it? What's the use of worrying about it? In the morning we'll come back and fill up our bags, and then clear out of the place and trek for civilization as if the devil and all were after us. Just think, my lads, what there will be to divide."

"A million apiece, at least," said Hayle rapturously, and then in an awed voice he added, as if he were discomfited by his own significance, "I never thought to be worth a quarter of that. Somehow it doesn't seem as if it can be real."

"It's quite real," said Mr. Codd, as he sprinkled some dry dust round the crack of the stone to give it an appearance of not having been disturbed. "There's no doubt of it."

When he had finished they picked up their tools and set off on their return journey to the camp. The sun had disappeared behind the jungle when they left the courtyard of the Three Elephants' Heads and ascended the stone steps towards the inner moat. They crossed the bridge, and entered the outer city in silence. The place was very dreary at that hour of the day, and to Codd, who was of an imaginative turn of mind, it seemed as if faces out of the long deserted past were watching him from every house. His companions, however, were scarcely so impressionable. They were gloating over the treasure they had won for themselves, and one, at least, was speculating as to how he should spend his share. Suddenly Hayle, who was looking down a side street, uttered an exclamation of surprise.

"Did you see that?" he inquired of Kitwater. Then, without waiting for a reply, he dived into the nearest ruin and disappeared from view.

"What on earth is the matter with him?" inquired Kitwater of Codd. "Has he gone mad?"

Codd only shook his head. Hayle's doings were more often than not an enigma to him. Presently, however, the runaway made his appearance before them. His face was flushed and he breathed heavily. Apparently he had been running, and for some distance.

"Didn't you see him?" he inquired of his companions in some surprise.

"See who?" asked Kitwater, with elevated eyebrows. "Who do you think you saw?"

"A man," Hayle replied. "I am ready to take my oath I saw him cross that narrow street back yonder."

"Was it one of our own men do you think?" said Codd, referring to the two Burmen they had brought with them.

"Not a bit of it," Hayle replied. "I tell you, Kitwater, I am as sure as I am of anything that the man I saw was a Chinaman."

"Gammon," said Kitwater. "There isn't a Chinaman within fifty miles of the ruins. You are unduly excited. You'll be seeing a regiment of Scots Guards presently if you are not careful."

"I don't care what you say, it was a man I saw," the other answered. "Good Heavens! won't you believe me, when I say that I saw his pigtail?"

"Believe you, of course I will," replied Kitwater good-humouredly. "It's a pity you didn't catch hold of him by it, however. No, no, Gid, you take my word for it, there are no Chinamen about here. What do you think, Codd?"

Mr. Codd appeared to have no opinion, for he did not reply.

By this time they had crossed the last bridge and had left the city behind them. The jungle was lulling itself to sleep, and drowsy croonings sounded on every hand. So certain was Hayle that he had not been mistaken about the man he declared he had seen, that he kept his eyes well open to guard against a surprise. He did not know what clump of bamboo might contain an enemy, and, in consequence, his right hand was kept continually in his pocket in order not to lose the grip of the revolver therein contained. At last they reached the top of the hill and approached the open spot where their camp was situated.

"What did I tell you?" said Kitwater, as he looked about the camp and could discover no traces of their two native servants. "It was one of our prowling rascals you saw, and when he comes back I'll teach him to come spying on us. If I know anything of the rattan, he won't do it again."

Hayle shrugged his shoulders. While the fact that their servants were not at the camp to anticipate their return was certainly suspicious, he was still as convinced as ever that the man he had seen slipping through the ruins was no Burman, but a true son of the Celestial Empire.

Worn out by the excitement of the day, Kitwater anathematized the servants for not having been there to prepare the evening meal, but while he and Hayle wrangled, Mr. Codd had as usual taken the matter into his own hands, and, picking up a cooking-pot, had set off in the direction of the stream, whence they drew their supply of water. He had not proceeded very far, however, before he uttered a cry and came running back to the camp. There was a scared expression upon his face as he rejoined his companions.

"They've not run away," he cried, pointing in the direction whence he had come. "They're dead!"

"Dead?" cried Kitwater and Hayle together. Then the latter added, "What do you mean by that?"

"What I say," Codd replied. "They're both lying in the jungle back there with their throats cut."

"Then I was right after all," Hayle found time to put in. "Come, Kit, let us go and see. There's more than we bargained for at the back of all this."

They hurried with Codd to the spot where he had discovered the bodies, to find that his tale was too true. Their two unfortunate servants were to be seen lying one on either side of the track, both dead and shockingly mutilated. Kitwater knelt beside them and examined them more closely.

"Chinese," he said laconically. Then after a pause he continued, "It's a good thing for us we had the foresight to take our rifles with us to-day, otherwise we should have lost them for a certainty. Now we shall have to keep our eyes open for trouble. It won't be long in coming, mark my words."

"You don't think they watched us at work in that courtyard, do you?" asked Hayle anxiously, as they returned to the camp. "If that's so, they'll have every atom of the remaining treasure, and we shall be done for."

He spoke as if until that moment they had received nothing.

"It's just possible they may have done so, of course," said Kitwater, "but how are we to know? We couldn't prevent them, for we don't know how many of them there may be. That fellow you saw this evening may only have been placed there to spy upon our movements. Confound it all, I wish we were a bigger party."

"It's no use wishing that," Hayle returned, and then after a pause he added—"Fortunately we hold a good many lives in our hands, and what's more, we know the value of our own. The only thing we can do is to watch, watch, and watch, and, if we are taken by surprise, we shall have nobody to thank for it but ourselves. Now if you'll stand sentry, Coddy and I will get tea."

They set to work, and the meal was in due course served and eaten. Afterwards Codd went on guard, being relieved by Hayle at midnight. Ever since they had made the ghastly discovery in the jungle, the latter had been more silent even than the gravity of the situation demanded. Now he sat, nursing his rifle, listening to the mysterious voices of the jungle, and thinking as if for dear life. Meanwhile his companions slept soundly on, secure in the fact that he was watching over them.

At last Hayle rose to his feet.

"It's my only chance," he said to himself, as he went softly across to where Kitwater was lying. "It must be now or never!"

Kneeling beside the sleeping man, he felt for the packet of precious stones they had that day obtained. Having found it he transferred it to his own pocket, and then returned to his former position as quietly as he had come. Then, having secured as much of their store of ammunition as he could conveniently carry, together with a supply of food sufficient to last him for several days, he deserted his post, abandoned his friends, and disappeared into the jungle!

The sun was slowly sinking behind the dense wall of jungle which hems in, on the southern side, the frontier station of Nampoung. In the river below there is a Ford, which has a distinguished claim on fame, inasmuch as it is one of the gateways from Burmah into Western China. This Ford is guarded continually by a company of Sikhs, under the command of an English officer. To be candid, it is not a post that is much sought after. Its dullness is extraordinary. True, one can fish there from morning until night, if one is so disposed; and if one has the good fortune to be a botanist, there is an inexhaustible field open for study. It is also true that Nampoung is only thirty miles or so, as the crow flies, from Bhamo, and when one has been in the wilds, and out of touch of civilization for months at a time, Bhamo is by no means a place to be despised. So thought Gregory, of the 123rd Burmah Regiment, as he threw his line into the pool below him.

"It's worse than a dog's life," he said to himself, as he looked at the Ford a hundred yards or so to his right, where, at the moment, his subaltern was engaged levying toll upon some Yunnan merchants who were carrying cotton on pack-mules into China. After that he glanced behind him at the little cluster of buildings on the hill, and groaned once more. "I wonder what they are doing in England," he continued. "Trout-fishing has just begun, and I can imagine the dear old Governor at the Long Pool, rod in hand. The girls will stroll down in the afternoon to find out what sport he has had, and they'll walk home across the Park with him, while the Mater will probably meet them half way. And here am I in this God-forsaken hole with nothing to do but to keep an eye on that Ford there. Bhamo is better than this; Mandalay is better than Bhamo, and Rangoon is better than either. Chivvying dakus is paradise compared with this sort of thing. Anyhow, I'm tired of fishing."

He began to take his rod to pieces preparatory to returning to his quarters on the hill. He had just unshipped the last joint, when he became aware that one of his men was approaching him. He inquired his business, and was informed in return that Dempsey, his sub, would be glad to see him at the Ford. Handing his rod to the man he set off in the direction of the crossing in question, to become aware, as he approached it, of a disreputable figure propped up against a tree on the nearer bank.

"What's the matter, Dempsey?" he inquired. "What on earth have you got there, man?"

"Well, that's more than I can say," the other replied. "He's evidently a white man, and I fancy an Englishman. At home we should call him a scarecrow. He turned up from across the Ford just now, and tumbled down in the middle of the stream like a shot rabbit. Never saw such a thing before. He's not a pretty sight, is he?"

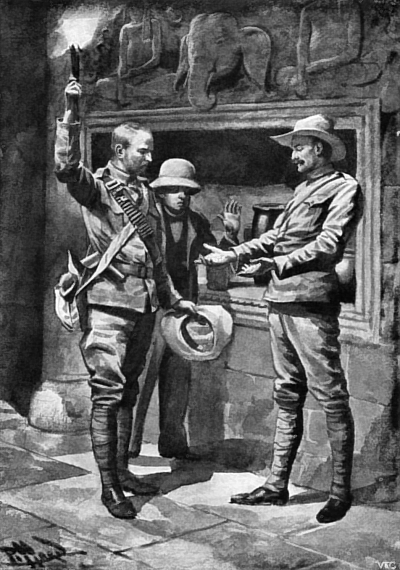

" 'POOR DEVIL,' SAID GREGORY. 'HE SEEMS TO BE ON HIS LAST LEGS.' "

"Poor devil," said Gregory. "He seems to be on his last legs. I wonder who the deuce he is, and what brought him into this condition."

"I've searched, and there's nothing about to tell us," said Dempsey. "What do you think we had better do with him?"

"Get him up the hill," said his superior, without hesitation. "When he's a bit stronger we'll have his story out of him. I'll bet a few years' pay it will be interesting."

A file of men were called, and the mysterious stranger was carried up to the residence of the English officers. It was plain to the least observant that he was in a very serious condition. Such clothes as he possessed were in rags; his face was pinched with starvation, and moreover he was quite unconscious. When his bearers, accompanied by the two Englishmen, reached the cluster of huts, he was carried to a small room at the end of the officers' bungalow and placed upon the bed. After a little brandy had been administered, he recovered consciousness and looked about him. Heaving a sigh of relief, he inquired where he might be.

"You are at Nampoung," said Gregory, "and you ought to thank your stars that you are not in Kingdom Come. If ever a man was near it, you have been. We won't ask you for your story now; however, later on, you shall bukh to your heart's content. Now I am going to give you something to eat. You look as if you want it badly enough."

Gregory looked at Dempsey and made a sign, whereupon the other withdrew, to presently return carrying a bowl of soup. The stranger drank it ravenously, and then lay back and closed his eyes once more. He would have been a clever man who could have recognized in the emaciated being upon the bed, the spruce, well-cared-for individual who was known to the Hotel of the Three Desires in Singapore as Gideon Hayle.

"You'd better rest a while now," said Gregory, "and then perhaps you'll feel equal to joining us at mess, or whatever you like to call it."

"Thanks very much," the man replied, with the conventional utterance of an English gentleman, which was not lost upon his audience. "I hope I shall feel up to it."

"Whoever the fellow is," said Gregory, as they passed along the verandah a few minutes later, "he has evidently seen better days. Poor beggar, I wonder where he's been, and what he has been up to?"

"We shall soon find out," Dempsey answered. "All he said when we fished him out of the water was 'at last,' and then he fainted clean away. I am not more curious than my neighbours, but I don't mind admitting that I am anxious to hear what he has to say for himself. Talk about Rip Van Winkle, why, he is not in it with this fellow. He could give him points and beat him hollow."

An hour later the stranger was so far recovered as to be able to join his hosts at their evening meal. Between them they had managed to fit him out with a somewhat composite set of garments. He had shaved off his beard, had reduced his hair to something like order, and in consequence had now the outward resemblance at least of a gentleman.

"Come, that's better," said Gregory as he welcomed him. "I don't know what your usual self may be like, but you certainly have more the appearance of a man, and less that of a skeleton than when we first brought you in. You must have been pretty hard put to it out yonder."

The recollection of all he had been through was so vivid, that the man shuddered at the mere thought of it.

"I wouldn't go through it again for worlds," he said. "You don't know what I've endured."

"Trading over the border alone?" Gregory inquired.

The man shook his head.

"Tried to walk across from Pekin," he said, "viâ Szechuen and Yunnan. Nearly died of dysentery in Yunnan city. While I was there my servants deserted me, taking with them every halfpenny I possessed. Being suspected by the Mandarins, I was thrown into prison, managed eventually to escape, and so made my way on here. I thought to-day was going to prove my last."

"You have had a hard time of it, by Jove," said Dempsey; "but you've managed to come out of it alive. And now where are you going?"

"I want, if possible, to get to Rangoon," the other replied. "Then I shall ship for England as best as I can. I've had enough of China to last me a lifetime."

From that moment the stranger did not refer again to his journey. He was singularly reticent upon this point, and feeling that perhaps the recollection of all he had suffered might be painful to him, the two men did not press him to unburden himself.

"He's a strange sort of fellow," said Gregory to Dempsey, later in the evening, when the other had retired to rest. "If he has walked from Pekin here, as he says, he's more than a little modest about it. I'll be bound his is a funny story if only he would condescend to tell it."

They would have been more certain than ever of this fact had they been able to see their guest at that particular moment. In the solitude of his own room he had removed a broad leather belt from round his waist. From the pocket of this belt he shook out upwards of a hundred rubies and sapphires of extraordinary size. He counted them carefully, replaced them in the belt, and then once more secured the latter about his waist.

"At last I am safe," he muttered to himself, "but it was a close shave—a very close shave. I wouldn't do that journey again for all the money the stones are worth. No! not for twice the amount."

Once more the recollection of his sufferings rose so vividly before him that he could not suppress a shudder. Then he arranged the mosquito-curtains of his bed, and laid himself down upon it. It was not long before he was fast asleep.

Before he went to his own quarters, Gregory looked in upon the stranger to find him sleeping heavily, one arm thrown above his head.

"Poor beggar!" said the kind-hearted Englishman, as he looked down at him. "One meets some extraordinary characters out here. But I think he's the strangest that has come into my experience."

The words had scarcely left his lips before the stranger was sitting up in bed with a look of abject terror in his eyes. The sweat of a living fear was streaming down his face. Gregory ran to him and placed his arm about him.

"What's the matter?" he asked. "Pull yourself together, man, there's nothing for you to fear here. You're quite safe."

The other looked at him for a moment as if he did not recognize him. Then, taking in the situation, he gave an uneasy laugh.

"I have had such an awful nightmare," he said. "I thought the Chinese were after me again. Lord! how thankful I am it's not true."

Next morning George Bertram, as he called himself, left Nampoung for Bhamo, with Gregory's cheque for five hundred rupees in his pocket.

"You must take it," said that individual in reply to the other's half-hearted refusal of the assistance. "Treat it as a loan if you like. You can return it to me when you are in better circumstances. I assure you I don't want it. We can't spend money out here."

Little did he imagine when he made that offer, the immense wealth which the other carried in the belt that encircled his waist. Needless to say Hayle said nothing to him upon the subject. He merely pocketed the cheque with an expression of his gratitude, promising to repay it as soon as he reached London. As a matter of fact he did so, and to this day, I have no doubt, Gregory regards him as a man of the most scrupulous and unusual integrity.

Two days later the wanderer reached Bhamo, that important military post on the sluggish Irrawaddy. His appearance, thanks to Gregory and Dempsey's kind offices, was now sufficiently conventional to attract little or no attention, so he negotiated the Captain's cheque, fitted himself out with a few other things that he required, and then set off for Mandalay. From Mandalay he proceeded as fast as steam could take him to Rangoon, where, after the exercise of some diplomacy, he secured a passage aboard a tramp steamer bound for England.

When the Shweydagon was lost in the evening mist, and the steamer had made her way slowly down the sluggish stream with the rice-fields on either side, Hayle went aft and took his last look at the land to which he was saying good-bye.

"A quarter of a million if a halfpenny," he said, "and as soon as they are sold and the money is in my hands, the leaf shall be turned, and my life for the future shall be all respectability."

Two months had elapsed since the mysterious traveller from China had left the lonely frontier station at Nampoung. In outward appearance it was very much the same as it had been then. The only difference consisted in the fact that Captain Gregory and his subaltern Dempsey, having finished their period of enforced exile, had returned to Bhamo to join the main body of their regiment. A Captain Handiman and a subaltern named Grantham had taken their places, and were imitating them inasmuch as they spent the greater portion of their time fishing and complaining of the hardness of their lot. It was the more unfortunate in their case that they did not get on very well together. The fact of the matter was Handiman was built on very different lines to Gregory, his predecessor; he gave himself airs, and was fond of asserting his authority. In consequence the solitary life at the Ford sat heavily upon both men.

One hot afternoon, Grantham, who was a keen sportsman, took his gun, and, accompanied by a wiry little Shan servant, departed into the jungle on shikar thoughts intent. He was less successful than usual; indeed, he had proceeded fully three miles before he saw anything worth emptying his gun at. In the jungle the air was as close as a hothouse, and the perspiration ran down his face in streams.

"What an ass I was to come out!" he said angrily to himself. "This heat is unbearable."

At that moment a crashing noise reached him from behind. Turning to discover what occasioned it, he was just in time to see a large boar cross the clearing and disappear into the bamboos on the further side. Taking his rifle from the little Shan he set off in pursuit. It was no easy task, for the jungle in that neighbourhood was so dense that it was well nigh impossible to make one's way through it. At last, however, they hit upon a dried up nullah, and followed it along, listening as they went to the progress the boar was making among the bamboos on their right. Presently they sighted him, crossing an open space a couple of hundred yards or so ahead of them. On the further side he stopped and began to feed. This was Grantham's opportunity, and, sighting his rifle, he fired. The beast dropped like a stone, well hit, just behind the shoulder. The report, however, had scarcely died away before the little Shan held up his hand to attract Grantham's attention.

"What is it?" the other inquired.

Before the man had time to reply his quick ear caught the sound of a faint call from the jungle on the other side of the nullah. Without doubt it was the English word help, and, whoever the man might be who called, it was plain that he was in sore straits.

"What the deuce does it mean?" said Grantham, half to himself and half to the man beside him. "Some poor devil got lost in the jungle, I suppose? I'll go and have a look."

Having climbed the bank of the nullah, he was about to proceed in the direction whence the cry had come, when he became aware of the most extraordinary figure he had ever seen in his life approaching him. The appearance Hayle had presented when he had turned up at the Ford two months before was nothing compared with that of this individual. He was a small man, not more than five feet in height. His clothes were in rags, a grizzly beard grew in patches upon his cheeks and chin, while his hair reached nearly to his shoulders. His face was pinched until it looked more like that of a skeleton than a man. Grantham stood and stared at him, scarcely able to believe his eyes.

"Good Heavens," he said to himself, "what a figure! I wonder where the beggar hails from?" Then addressing the man, he continued, "Are you an Englishman, or what are you?"

The man before him, however, did not reply. He placed his finger on his lips, and turning, pointed in the direction he had come.

"Either he doesn't understand, or he's dumb," said Grantham. "But it's quite certain that he wants me to follow him somewhere."

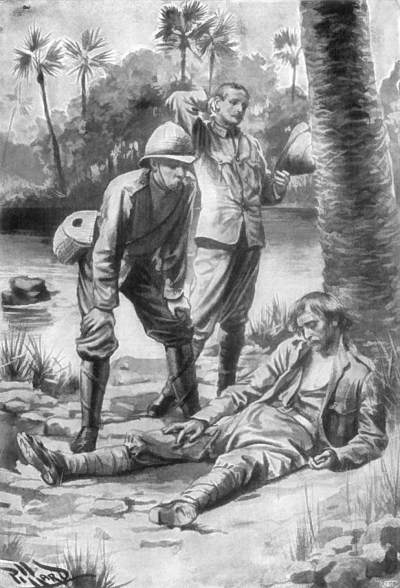

Turning to the man again, he signed to him to proceed, whereupon the little fellow hobbled painfully away from the nullah in the direction whence he had appeared. On and on he went until he at length came to a standstill at the foot of a hill, where a little stream came splashing down in a miniature cascade from the rocks above. Then Grantham realized the meaning of the little man's action. Stretched out beside a rock was the tall figure of a man. Like his companion, he presented a miserable appearance. His clothes, if clothes they could be called, were in rags, his hair was long and snowy white, matching his beard, which descended to within a few inches of his waist. His eyes were closed, and for a moment Grantham thought he was dead. This was not the case, however, for upon his companion approaching him he held out his hand and inquired whether he had discovered the man who had fired the shot?

To Grantham's surprise the other made no reply in words, but, taking his friend's hand he made some mysterious movements upon it with his fingers, whereupon the latter raised himself to a sitting position.

"My friend tells me that you are an Englishman," he said in a voice that shook with emotion. "I'm glad we have found you. I heard your rifle shot and hailed you. We are in sore distress, and have been through such adventures and such misery as no man would believe. I have poisoned my foot, and am unable to walk any further. As you can see for yourself I am blind, while my companion is dumb."

This statement accounted for the smaller man's curious behaviour and the other's closed eyes.

"You have suffered indeed," said Grantham pityingly. "But how did it all come about?"

"We were traders, and we fell into the hands of the Chinese," the taller man answered. "With their usual amiability they set to work to torture us. My companion's tongue they cut out at the roots, while, as I have said, they deprived me of my sight. After that they turned us loose to go where we would. We have wandered here, there, and everywhere, living on what we could pick up, and dying a thousand deaths every day. It would have been better if we had died outright—but somehow we've come through. Can you take us to a place where we can procure food? We've been living on jungle fruit for an eternity. My foot wants looking to pretty badly, too."

"We'll do all we can for you," said Grantham. "That's if we can get you down to the Ford, which is about five miles away."

"You'll have to carry me then, for I'm too far gone to walk."

"I think it can be managed," said Grantham. "At any rate we'll try."

Turning to the little Shan he despatched him with a message to Handiman, and when the other had disappeared, knelt down beside the tall man and set to work to examine his injured foot. There could be no doubt that it was in a very serious condition. Tramping through the jungle he had managed to poison it, and had been unable to apply the necessary remedies. Obtaining some water from the stream Grantham bathed it tenderly, and then bound it up as well as he could with his handkerchief.

"That's the best I can do for you for the present," he said. "We must leave it as it is, and, when we get you to the station, we will see what else can be managed."