Title: Ten Boys from Dickens

Author: Kate Dickinson Sweetser

Illustrator: George Alfred Williams

Release date: February 1, 2004 [eBook #11227]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/11227

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Andrea Ball and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

In this small volume there are presented as complete stories the boy-lives portrayed in the works of Charles Dickens. The boys are followed only to the threshold of manhood, and in all cases the original text of the story has been kept, except where of necessity a phrase or paragraph has been inserted to connect passages;—while the net-work of characters with which the boys are surrounded in the books from which they are taken, has been eliminated, except where such characters seem necessary to the development of the story in hand.

Charles Dickens was a loyal champion of all boys, and underlying his pen pictures of them was an earnest desire to remedy evils which he had found existing in London and its suburbs. Poor Jo, who was always being "moved on," David Copperfield, whose early life was a picture of Dickens' own childhood, workhouse-reared Oliver, and the miserable wretches at Dotheboy Hall were no mere creations of an author's vivid imagination. They were descriptions of living boys, the victims of tyranny and oppression which Dickens felt he must in some way alleviate. And so he wrote his novels with the histories in them which affected the London public far more deeply, of course, than they affect us, and awakened a storm of indignation and protest.

Schools, work-houses, and other public institutions were subjected to a rigorous examination, and in consequence several were closed, while all were greatly improved. Thus, in his sketches of boy-life, Dickens accomplished his object.

My aim is to bring these sketches, with all their beauty and pathos, to the notice of the young people of to-day. If through this volume any boy or girl should be aroused to a keener interest in the great writer, and should learn to love him and his work, my labour will be richly repaid.

KATE DICKINSON SWEETSER

Bolder, Cobbey, Graymarsh, Mobb's

Little Em'ly and David Copperfield

Charles Dickens has given us no picture of Tiny Tim, but at the thought of him comes a vision of a delicate figure, less boy than spirit. We seem to see a face oval in shape and fair in colouring. We see eyes deep-set and grey, shaded by lashes as dark as the hair parted from the middle of his low forehead. We see a sunny, patient smile which from time to time lights up his whole face, and a mouth whose firm, strong lines reveal clearly the beauty of character, and the happiness of disposition, which were Tiny Tim's.

He was a rare little chap indeed, and a prime favourite as well. Ask the Crachits old and young, whose smile they most desired, whose applause they most coveted, whose errands they almost fought with one another to run, whose sadness or pain could most affect the family happiness, and with one voice they would answer, "Tim's!"

It was Christmas Day, and in all the suburbs of London there was to be no merrier celebration than at the Crachits. To be sure, Bob Crachit had but fifteen "Bob" himself a week on which to clothe and feed all the little Crachits, but what they lacked in luxuries they made up in affection and contentment, and would not have changed places, one of them, with any king or queen.

While Bob took Tiny Tim to church, preparations for the feast were going on at home. Mrs. Crachit was dressed in a twice-turned gown, but brave in ribbons which are cheap and make a goodly show for sixpence; and she laid the cloth, assisted by Belinda, second of her daughters, also brave in ribbons, while Master Peter Crachit plunged a fork into a saucepan full of potatoes, getting the corners of his monstrous shirt collar (Bob's private property, conferred upon his son and heir in honour of the day) into his mouth, but rejoiced to find himself so finely dressed, and yearning to show his linen in the fashionable Parks.

Two smaller Crachits, boy and girl, came tearing in, screaming that outside the baker's they had smelt the goose, and known it for their own; and basking in luxurious thoughts of sage and onions, these young Crachits danced about the table, and exalted Master Peter Crachit to the skies, while he (not proud, although his collar almost choked him) blew the fire, until the slow potatoes, bubbling up, knocked loudly at the saucepan-lid to be let out and peeled.

"What has ever got your precious father, then?" said Mrs. Crachit. "And your brother, Tiny Tim! And Martha warn't as late last Christmas Day by half an hour!"

"Here's Martha, mother!" cried the two young Crachits. "Hurrah! there's such a goose, Martha!"

"Why, bless your heart alive, dear, how late you are!" said Mrs. Crachit, kissing the daughter, who lived away from home, a dozen times. "Well, never mind as long as you are come!"

"There's father coming!" cried the two young Crachits, who were everywhere at once. "Hide, Martha, hide!"

So Martha hid herself, and in came little Bob, the father, with at least three feet of comforter hanging down before him, and his threadbare clothes darned up and brushed to look seasonable; and Tiny Tim upon his shoulder. Why was the child thus carried? Alas for Tiny Tim, he bore a little crutch and had his limbs supported by an iron frame! Patient little Tim,—never was he heard to utter a fretful or complaining word. No wonder they cherished him so tenderly!

"Why, where's our Martha?" cried Bob Crachit looking round.

"Not coming!" said Mrs. Crachit.

"Not coming?" said Bob, with a sudden declension in his high spirits; for he had been Tim's blood horse all the way from church, and had come home rampant.

"Not coming upon Christmas Day!"

Martha didn't like to see him disappointed, if it were only in joke; so she ran out from behind the closet door, and ran into his arms, while the two young Crachits hustled Tiny Tim, and bore him off into the wash-house, that he might hear the pudding singing in the copper.

"And how did little Tim behave?" asked Mrs. Crachit; when she had rallied Bob on his credulity, and Bob had hugged his daughter to his heart's content.

"As good as gold," said Bob, "and better. Somehow he gets thoughtful, sitting by himself so much, and thinks the strangest things you ever heard. He told me, coming home, that 'he hoped the people saw him in the church, because he was a cripple, and it might be pleasant to them to remember upon Christmas Day, Who made lame beggars walk and blind men see.'"

Bob's voice was tremulous when he told them this, and it trembled more when he said that Tiny Tim was growing strong and hearty.

His active little crutch was heard upon the floor, and back came Tiny Tim before another word was spoken, escorted by his brother and sister to his stool before the fire; and while Bob compounded some hot mixture in a jug and put it on the hob to simmer, Master Peter and the two young Crachits went to fetch the goose, with which they soon returned in high procession.

Such a bustle ensued that you might have thought the goose the rarest of all birds, and in truth it was something very like it in that house. Mrs. Crachit made the gravy hissing hot; Master Peter mashed the potatoes with incredible vigour; Miss Belinda sweetened up the apple sauce; Martha dusted the hot plates; Bob took Tiny Tim beside him in a corner at the table; the two young Crachits set chairs for everybody, not forgetting themselves, and mounting guard upon their posts, crammed spoons into their mouths, lest they should shriek for goose before their turn came to be helped. At last the dishes were set on and grace was said. It was succeeded by a breathless pause, as Mrs. Crachit, looking slowly along the carving knife, prepared to plunge it in the breast. When she did one murmur of delight arose all round the board, and even Tiny Tim, excited by the two young Crachits, beat on the table with the handle of his knife, and feebly cried "Hurrah!"

There never was such a goose! its tenderness and size, flavour and cheapness, were the themes of universal admiration. Eked out by apple-sauce and mashed potatoes, every one had enough, and the youngest Crachits were steeped in sage and onion to the eyebrows! But now, the plates being changed, Mrs. Crachit left the room alone—too nervous to bear witnesses—to take the pudding up, and bring it in.

Suppose it should not be done enough! Suppose it should break in turning out! All sorts of horrors were supposed.

Hallo! a great deal of steam! The pudding was out of the copper, and in half a minute Mrs. Crachit entered, flushed, but smiling proudly, with the pudding blazing in ignited brandy, and with Christmas holly stuck into the top.

Its appearance was hailed with cheers and with exclamations of joyous admiration. Then, when it was safely landed upon the table, what a racket and clatter there was! Such stories and songs and jokes, and such riotous applause no one can imagine who was not there to see and hear!

At last the dinner was all done, the cloth was cleared, the hearth swept, and the fire made up. The compound in the jug being tasted and pronounced perfect, apples and oranges were put upon the table and a shovelful of chestnuts on the fire. Then all the Crachit family drew round the hearth, Tiny Tim very close to his father's side, upon his little stool, while he gave them a song in his plaintive little voice, about a lost child, and sang it very well indeed.

At Bob Crachit's elbow stood the family display of glass; two tumblers and a custard cup without a handle. These held the hot stuff from the jug, however, as well as golden goblets would have done, and Bob served it out with beaming looks, while the chestnuts sputtered and cracked noisily. Then Bob proposed:

"A merry Christmas to us all, my dears,—God bless us!"

which was just what was needed to bring the joy and enthusiasm to a climax. Cheer after cheer went up, over and over the toast was re-echoed, and then one was added for the family ogre, Bob's hard employer, Mr. Scrooge, and one for old and for young, for sick and for well, for Father Christmas and for Father Crachit and for all the little Crachits;—for everyone everywhere who had heard the holiday bells, there was a toast given. Then when the uproar ceased for a moment, low and sweet spoke Tiny Tim alone:

"God bless us every one!"

Clearly it rang out in the earnest childish voice. There was a sudden hush of the merriment, while Bob's arm stole round his son with a firmer grasp and for a moment the shadow of a coming Christmas fell upon him, when the little stool would be vacant and the little crutch unused.

Spirit of Tiny Tim, thy childish essence was from God! Thou didst not know that in the benediction of lives like thine, is given the answer to such prayers. Much did thy loved ones learn from thee; much can the world learn of the nobility of patience from thy sweet child life. Unawares thou wert thyself an answer to thy Christmas prayer:

"God bless us every one!"

Oliver Twist was the child of an unknown woman who died in the workhouse of an English village, almost as soon as her babe drew his first breath. The mother's name being unknown, the workhouse officials called the child Oliver Twist, under which title he grew up. For nine years he was farmed out at a branch poorhouse, where with twenty or thirty other children he bore all the miseries consequent on neglect, abuse, and starvation. He was then removed to the workhouse proper to be taught a useful trade.

His ninth birthday found him a pale, thin child, diminutive in stature, and decidedly small in circumference, but possessed of a good sturdy spirit, which was not broken by the policy of the officials who tried to get as much work out of the paupers as possible, and to keep them on as scant a supply of food as would sustain life.

The boys were fed in a large stone hall, with a copper at one end, out of which the gruel was ladled at meal-times. Of this festive composition each boy had one porringer, and no more—except on occasions of great public rejoicing, when he had two ounces and a quarter of bread besides. The bowls never wanted washing. The boys polished them with their spoons till they shone again; and when they had performed this operation, they would sit staring at the copper, as if they could have devoured the very bricks of which it was composed; sucking their fingers, with the view of catching up any stray splashes of gruel that might have been cast thereon.

Boys have generally excellent appetites. Oliver Twist and his companions suffered the tortures of slow starvation for three months: at last they got so voracious and wild that one boy hinted darkly that unless he had another basin of gruel a day, he was afraid he might some night happen to eat the boy who slept next him. He had a wild, hungry, eye; and they implicitly believed him. A council was held; lots were cast who should walk up to the master, and ask for more, and it fell to Oliver Twist.

The evening arrived; the boys took their places. The gruel was served out, and a long grace was said. The gruel disappeared; the boys whispered each other, and winked at Oliver; while his next neighbours nudged him. Child as he was, he was desperate with hunger, and reckless with misery. He rose and advancing to the master, basin and spoon in hand, said, somewhat alarmed at his own temerity:

"Please, sir, I want some more!"

The master was a fat, healthy man; but he turned very pale. He gazed in stupified astonishment on the small rebel for some seconds, and then clung for support to the copper. The assistants were paralysed with wonder; the boys with fear.

"What?" said the master at length, in a faint voice.

"Please, sir," replied Oliver, "I want some more."

The master aimed a blow at Oliver's head with the ladle; pinioned him in his arms; and shrieked for the beadle, and when that gentleman appeared, an animated discussion took place. Oliver was ordered into instant confinement; and a bill was next morning pasted on the outside of the gate, offering a reward of five pounds to any body who would take Oliver Twist off the hands of the parish. In other words, five pounds, and Oliver Twist were offered to any man or woman who wanted an apprentice to any trade, business, or calling.

Mr. Sowerberry, the parish undertaker, finally applied for the prize, and carried Oliver away with him, which, for the poor boy, was a matter of falling from the frying pan into the fire, and in his short career as undertaker's assistant he even sighed for the workhouse,—miserable as his life there had been. At the undertaker's, Oliver's bed was in the shop. The atmosphere seemed tainted with the smell of coffins. The recess behind the counter in which his mattress was thrust, looked like a grave. His food was broken bits left from the meals of others, and his constant companion was an older boy, Noah Claypole, who, although a charity boy himself, was not a workhouse orphan, and therefore considered himself in a position above Oliver. He made Oliver's days hideous with his abuse, which the younger boy bore as quietly as he could, until the day when Noah made a sneering remark about Oliver's dead mother. That was too much. Crimson with fury, Oliver started up, seized Noah by the throat, shook him till his teeth chattered, and then with one heavy blow, felled him to the ground.

This brought about a violent scene, for Noah accused Oliver of attempting to murder him, and Mrs. Sowerberry, the maid, and the beadle,—who had been hastily summoned,—agreed that Oliver was a hardened wretch, only fit for confinement, and he was accordingly placed in the cellar, till the undertaker came in, when he was dragged out again to have the story retold. To do Mr. Sowerberry justice, he would have been kindly disposed towards Oliver, but for the prejudice of his wife against the boy. However, to satisfy her, he gave Oliver a sound beating, and shut him up in the back kitchen until night, when, amidst the jeers and pointings of Noah and Mrs. Sowerberry, he was ordered up-stairs to his dismal bed.

It was then, alone, in the silence of the gloomy workshop, that Oliver gave way to his feelings, wept bitterly, and resolved no longer to bear such treatment. Softly he undid the fastenings of the door, and looked abroad. It was a cold night. The stars seemed, to the boy's eyes, farther from the earth than he had ever seen them before; there was no wind; and the sombre shadows looked sepulchral and death-like, from being so still. He softly reclosed the door, and having availed himself of the expiring light of the candle to tie up in a handkerchief the few articles of wearing apparel he had, sat himself down to wait for morning.

With the first ray of light, Oliver arose, and again unbarred the door. One timid look around,—one minute's pause of hesitation,—he had closed it behind him.

He looked to the right, and to the left, uncertain whither to fly. He remembered to have seen the waggons, as they went out, toiling up the hill, so he took the same route; and arriving at a footpath which he knew led out into the road, struck into it, and walked quickly on.

For seven long days he tramped in the direction of London, tasting nothing but such scraps of meals as he could beg from the occasional cottages by the roadside. On the seventh morning he limped slowly into the little town of Barnet, and as he was resting for a few moments on the steps of a public-house, a boy crossed over, and walking close to him, said,

"Hullo! my covey! What's the row?"

The boy who addressed this inquiry to the young wayfarer, was about his own age: but one of the queerest looking boys that Oliver had ever seen. He was a snub-nosed, flat-browed, common-faced boy enough; and as dirty a juvenile as one would wish to see; but he had about him all the airs and manners of a man. He was short, with bow-legs, and little, sharp, ugly, eyes. His hat was stuck on the top of his head, and he wore a man's coat that reached nearly to his heels.

"Hullo, my covey! What's the row?" said this strange young gentleman to Oliver.

"I am very hungry and tired," replied Oliver; the tears standing in his eyes as he spoke. "I have walked a long way. I have been walking these seven days."

"Going to London?" inquired the strange boy.

"Yes."

"Got any lodgings?"

"No."

"Money?"

"No."

The strange boy whistled; and put his arms into his pockets.

"Do you live in London?" inquired Oliver.

"Yes, I do when I'm at home," replied the boy. "I suppose you want some place to sleep in to-night, don't you?"

Upon Oliver answering in the affirmative, the strange boy, whose name was Jack Dawkins, said, "I've got to be in London to-night; and I know a 'spectable old genelman as lives there, wot'll give you lodgings for nothink, and never ask for the change—that is, if any genelman he knows interduces you."

This offer of shelter was too tempting to be resisted, and Oliver trudged off with his new friend. Into the city they passed, and through the worst and darkest streets, the sight of which filled Oliver with alarm. At length they reached the door of a house, which Jack entered, drawing Oliver after him, into its dark passage-way, and closing the door after them.

Oliver, groping his way with one hand, and having the other firmly grasped by his companion, ascended with much difficulty the dark and broken stairs, which his conductor mounted with an expedition that showed he was well acquainted with them. He threw open the door of a back-room and drew Oliver in after him.

The walls and ceiling of the room were perfectly black with age and dirt. There was a clothes-horse, over which a great number of silk handkerchiefs were hanging; and a deal table before the fire; upon which were a candle, stuck in a ginger-beer bottle, two or three pewter pots, a loaf and butter, and a plate. In a frying pan, which was on the fire, some sausages were cooking, and standing over them, with a toasting-fork in his hand, was a very old shrivelled Jew, whose villanous-looking and repulsive face was obscured by a quantity of matted red hair.

Several rough beds, made of old sacks, were huddled side by side on the floor. Seated round the table were four or five boys, none older than Jack Dawkins, familiarly called the Dodger. The boys all crowded about their associate, as he whispered a few words to the Jew; and then they turned round and grinned at Oliver. So did the Jew himself, toasting-fork in hand.

"This is him, Fagin," said Jack Dawkins; "my friend Oliver Twist."

The Jew, making a low bow to Oliver, took him by the hand, and hoped he should have the honour of his intimate acquaintance. Upon this the young gentlemen came round him, and shook his hand very hard, especially the one in which he held his little bundle.

"We are very glad to see you, Oliver, very," said the Jew. "Dodger take off the sausages; and draw a tub near the fire for Oliver. Ah, you're a-staring at the pocket-handkerchiefs! eh, my dear? There are a good many of 'em, ain't there? We've just looked 'em out ready for the wash; that's all, Oliver, that's all. Ha! ha! ha!"

The latter part of this speech was hailed by a boisterous shout from the boys, who, Oliver found, were all pupils of the merry old gentleman. In the midst of which they went to supper.

Oliver ate his share, and the Jew then mixed him a glass of hot gin and water, telling him he must drink it off directly because another gentleman wanted the tumbler. Oliver did as he was desired. Immediately afterwards, he felt himself gently lifted on to one of the sacks; and then he sunk into a deep sleep.

It was late next morning when Oliver awoke, from a sound, long sleep. There was no other person in the room but the old Jew, who was boiling some coffee in a saucepan for breakfast, and whistling softly to himself as he stirred it. He would stop every now and then to listen when there was the least noise below; and, when he had satisfied himself, he would go on, whistling and stirring again, as before.

When the coffee was done, the Jew drew the saucepan to the hob, then he turned and looked at Oliver, and called him by name, but the boy did not answer, and was to all appearances asleep. After satisfying himself upon this head, the Jew stepped gently to the door, which he fastened. He then drew forth as it seemed to Oliver, from some trap in the floor a small box, which he placed carefully on the table. His eyes glistened as he raised the lid, and looked in. Dragging an old chair to the table, he sat down, and took from it a magnificent gold watch, sparkling with jewels.

At least half a dozen more were severally drawn forth from the same box, besides rings, brooches, bracelets, and other articles of jewellery, of such magnificent materials, and costly workmanship, that Oliver had no idea, even of their names.

At length the bright, dark eyes of the Jew, which had been staring vacantly before him, fell on Oliver's face; the boy's eyes were fixed on his in mute curiosity; and, although the recognition was only for an instant,—it was enough to show the man that he had been observed. He closed the lid of the box with a loud crash; and, laying his hand on a bread knife which was on the table, started furiously up.

"What's that?" said the Jew. "What do you watch me for? Why are you awake? What have you seen? Speak out, boy! Quick—quick! for your life!"

"I wasn't able to sleep any longer, sir," replied Oliver meekly. "I am very sorry if I have disturbed you, sir."

"You were not awake an hour ago?" said the Jew, scowling fiercely.

"No! No indeed!" replied Oliver.

"Are you sure?" cried the Jew, with a still fiercer look than before, and a threatening attitude.

"Upon my word I was not, sir," replied Oliver, earnestly. "I was not, indeed, sir."

"Tush, tush, my dear!" said the Jew, abruptly resuming his old manner. "Of course I know that, my dear, I only tried to frighten you. You're a brave boy. Ha! ha! you're a brave boy, Oliver!"

The Jew rubbed his hands with a chuckle, but glanced uneasily at the box, notwithstanding.

"Did you see any of these pretty things, my dear?" said the Jew.

"Yes, sir," replied Oliver.

"Ah!" said Fagin, turning rather pale. "They—they're mine, Oliver; my little property. All I have to live upon in my old age. The folks call me a miser, my dear. Only a miser; that's all."

Oliver thought the old gentleman must be a decided miser to live in such a dirty place, with so many watches; but thinking that perhaps his fondness for the Dodger and the other boys, cost him a good deal of money, he only cast a deferential look at the Jew, and asked if he might get up. Permission being granted him, he got up, walked across the room, and stooped for an instant to raise the water-pitcher. When he turned his head, the box was gone.

Presently the Dodger returned with a friend, Charley Bates, and the four sat down to a breakfast of coffee, and some hot rolls, and ham, which the Dodger had brought home in the crown of his hat.

"Well," said the Jew, "I hope you've been at work this morning, my dears?"

"Hard," replied the Dodger.

"As Nails," added Charley Bates.

"Good boys, good boys!" said the Jew. "What have you got, Dodger?"

"A couple of pocket-books," replied the young gentleman.

"Lined?" inquired the Jew, with eagerness.

"Pretty well," replied the Dodger, producing two pocket-books.

"And what have you got, my dear?" said Fagin to Charley Bates.

"Wipes," replied Master Bates; at the same time producing four pocket-handkerchiefs.

"Well," said the Jew, inspecting them closely; "they 're very good ones, very. You haven't marked them well, though, Charley; so the marks shall be picked out with a needle, and we'll teach Oliver how to do it. Shall us, Oliver, eh?"

"If you please, sir," said Oliver.

"You'd like to be able to make pocket-handkerchiefs as easy as Charley Bates, wouldn't you, my dear?" said the Jew.

"Very much indeed, if you'll teach me, sir," replied Oliver.

Master Bates saw something so exquisitely ludicrous in this reply, that he burst into a laugh; which laugh, meeting the coffee he was drinking, and carrying it down some wrong channel, very nearly terminated in his suffocation.

"He is so jolly green!" said Charley, when he recovered, as an apology to the company for his unpolite behaviour.

When the breakfast was cleared away, the merry old gentleman and the two boys played at a very curious and uncommon game, which was performed in this way. Fagin, placing a snuff-box in one pocket of his trousers, a notecase in the other, and a watch in his waistcoat pocket, with a guard-chain round his neck, and sticking a mock diamond pin in his shirt, buttoned his coat tight round him, and putting his spectacle-case and handkerchief in his pockets, trotted up and down with a stick, in imitation of the manner in which old gentlemen walk about the streets. Sometimes he stopped at the fire-place, and sometimes at the door, making believe that he was staring with all his might into shop windows. At such times he would look constantly round him, for fear of thieves, and would keep slapping all his pockets in turn, to see that he hadn't lost anything, in such a very funny and natural manner, that Oliver laughed till the tears ran down his face.

All this time, the two boys followed him closely about; getting out of his sight so nimbly, that it was impossible to follow their motions. At last, the Dodger trod upon his toes accidentally, while Charley Bates stumbled up against him behind; and in that one moment they took from him, with the most extraordinary rapidity, snuff-box, note-case, watch-guard, chain, shirt-pin, pocket-handkerchief—even the spectacle-case. If the old gentleman felt a hand in one of his pockets, he cried out where it was; and then the game began all over again.

When this game had been played a great many times, a couple of young women came in; one of whom was named Bet, and the other Nancy, and afterwards Oliver discovered that they also were pupils of Fagin's as well as the boys.

Later the young people went out, leaving Oliver alone with the Jew, who was pacing up and down the room.

"Is my handkerchief hanging out of my pocket, my dear?" said the Jew, stopping short, in front of Oliver.

"Yes sir," said Oliver.

"See if you can take it out, without my feeling it: as you saw them do when we were at play."

Oliver held up the bottom of the pocket with one hand, as he had seen the Dodger hold it, and drew the handkerchief lightly out of it with the other.

"Is it gone?" cried the Jew.

"Here it is, sir," said Oliver, showing it in his hand.

"You're a clever boy, my dear," said the playful old gentleman, patting Oliver on the head approvingly. "I never saw a sharper lad. Here's a shilling for you. If you go on in this way, you'll be the greatest man of the time. And now come here, and I'll show you how to take the marks out of the handkerchiefs."

Oliver wondered what picking the old gentleman's pocket in play, had to do with his chances of being a great man. But, thinking that the Jew, being so much his senior, must know best, he followed him quietly to the table, and was soon deeply involved in his new study.

For many days Oliver remained in the Jew's room, picking marks out of the pocket-handkerchiefs. But at length, he began to languish, and entreated Fagin to allow him to go out to work with his two companions. So, one morning, he obtained permission to go out, under the guardianship of Charley Bates and the Dodger.

The three boys sallied out; the Dodger with his coat-sleeves tucked up, and his hat cocked as usual; Master Bates sauntering along with his hands in his pockets; and Oliver between them, wondering where they were going, and what branch of manufacture he would be instructed in, first.

They were just emerging from a narrow court, when the Dodger made a sudden stop; and, laying his finger on his lip, drew his companions back again with the greatest caution.

"What's the matter?" demanded Oliver.

"Hush!" replied the Dodger. "Do you see that old cove at the book-stall?"

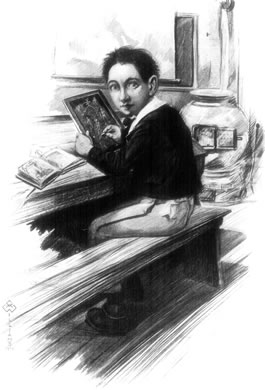

"The old gentleman over the way?" said Oliver. "Yes, I see him."

"He'll do," said the Dodger.

"A prime plant," observed Master Charley Bates.

Oliver looked from one to the other, with the greatest surprise; but could not ask any questions, for the two boys walked stealthily across the road, and slunk close behind the old gentleman. Oliver walked a few paces behind them, looking on in silent amazement.

The old gentleman had taken up a book from the stall; and there he stood: reading away, perfectly absorbed, and saw not the book-stall, nor the street, nor the boys, nor anything but the book itself. What was Oliver's horror and alarm to see the Dodger plunge his hand into the old gentleman's pocket, and draw from thence a handkerchief! To see him hand the same to Charley Bates; and finally to behold them, both, running away round the corner at full speed!

In an instant the whole mystery of the handkerchiefs, and the watches, and the jewels, and the Jew, rushed upon the boy's mind. He stood, for a moment, with the blood tingling through all his veins from terror; then, confused and frightened, he took to his heels.

In the very instant when Oliver began to run, the old gentleman, putting his hand to his pocket, and missing his handkerchief, turned sharp round. Seeing the boy scudding away at such a rapid pace, he very naturally concluded him to be the depredator, and, shouting "Stop thief!" with all his might, made off after him, book in hand. The Dodger and Master Bates, who had merely retired into the first doorway round the corner, no sooner heard the cry, and saw Oliver running, than they issued forth with great promptitude; and, shouting, "Stop thief! Stop thief!" too, joined in the pursuit like good citizens.

"Stop thief!" The cry is taken up by a hundred voices, the tradesman, the carman, the butcher, the baker, the milkman, the school-boy, follow in hot pursuit. Away they run, pell-mell, helter-skelter, slap-dash: tearing, yelling: screaming, knocking down the passengers as they turn the corners, splashing through the mud, and rattling along the pavements, following after the wretched, breathless, panting child, gaining upon him every instant. Stopped at last! A clever blow! He is down upon the pavement, covered with mud and dust, looking wildly round upon the heap of faces that surround him.

"Yes," said the old gentleman, "I am afraid that is the boy. Poor fellow! he has hurt himself!"

Just then a police officer appeared and dragged the half fainting boy off, the old gentleman walking beside him, Oliver protesting his innocence as they went. At the police station Oliver was searched in vain, and then locked in a cell for a time, while the old gentleman sat outside waiting, and read his book. Presently the boy was brought out before the Magistrate; and the policeman and the old gentleman preferred their charges against him. While the case was proceeding, Oliver fell to the floor in a fainting fit, and as he lay there the Magistrate uttered his penance, "He stands committed for three months of hard labour. Clear the office!" A couple of men were about to carry the insensible boy to his cell, when an elderly man rushed hastily into the office. "Stop, stop!" he said. "Don't take him away! I saw it all. I keep the book-stall. I saw three boys loitering on the opposite side of the way when this gentleman was reading. The robbery was committed by another boy. I saw it done; and I saw that this boy was perfectly amazed and stupified by it!"

Having by this time recovered a little breath, the bookstall keeper proceeded to relate in a more coherent manner the exact circumstances of the robbery, in consequence of which explanation Oliver Twist was discharged, and carried off, still white and faint, in a coach, by the kind-hearted old gentleman whose name was Brownlow, who seemed to feel himself responsible for the boy's condition, and resolved to have him cared for in his own home.

After Charley Bates and the Dodger had seen Oliver dragged away by the police officer, they scoured off with great rapidity. Coming to a halt Master Bates burst into an uncontrollable fit of laughter.

"What's the matter?" inquired the Dodger.

"I can't help it," said Charley, "I can't help it! To see him splitting away at that pace, and cutting round the corners, and knocking up against the posts, and starting on again as if he was made of iron, and me with the wipe in my pocket, singing out arter him—oh, my eye!" The vivid imagination of Master Bates presented the scene before him in too strong colours, and he rolled upon a door-step and laughed louder than before.

"What'll Fagin say?" inquired the Dodger, and the question sobered Master Bates at once, as both boys stood in great dread of the Jew. And their worst fears were realised. Fagin was livid with rage at the loss of his promising pupil, as well as fearful of the disclosures he might make. After long consultation on the subject, it was agreed by the band that Nancy was to go to the police station in a disguised dress, to find out what had been done with Oliver, for whom she was to search as her "dear little lost brother."

Meanwhile Oliver lay for many days burning with fever and unconscious of his surroundings, in the quietly comfortable home of Mr. Brownlow at Pentonville. At length, weak, and thin, and pallid, he awoke from what seemed a dream, and found himself being nursed by Mrs. Bedwin, Mr. Brownlow's motherly old house-keeper, and visited constantly by the doctor. Gradually he grew stronger, and soon could sit up a little. Those were happy, peaceful days of his recovery, the only happy ones he had ever known. Everybody was so kind and gentle that it seemed like Heaven itself, as he sat by the fireside in the house-keeper's room. On the wall hung a portrait of a beautiful, mild, lady with sorrowful eyes, of which Oliver was the living copy. Every feature was the same—to Mr. Brownlow's intense astonishment, as he gazed from it to Oliver.

Later, Oliver heard the history of the portrait and his own connection with it.

When he was strong enough to put his clothes on, Mr. Brownlow caused a complete new suit, and a new cap, and a new pair of shoes, to be provided for him. Oliver gave his old clothes to one of the servants who had been kind to him, and she sold them to a Jew who came to the house.

One evening Mr. Brownlow sent up word to have Oliver come down into his study and see him for a little while,—so Mrs. Bedwin helped him to prepare himself, and although there was not even time to crimp the little frill that bordered his shirt-collar, he looked so delicate and handsome, that she surveyed him with great complacency.

Mr. Brownlow was reading, but when he saw Oliver, he pushed the book away, and told him to come near, and sit down, which Oliver did. Then the old gentleman began to talk kindly of what Oliver's future was to be. Instantly the boy became pallid with fright, and implored Mr. Brownlow to let him stay with him, as a servant, as anything, only not to send him out into the streets again, and the old gentleman, touched by the appeal, assured the boy that unless he should deceive him, he would be his faithful friend. He then asked Oliver to relate the whole story of his life, which he was beginning to do when an old friend of Mr. Brownlow's—a Mr. Grimwig,—entered.

He was an eccentric old man, and was loud in his exclamations of distrust in this boy whom Mr. Brownlow was harbouring.

"I'll answer for that boy's truth with my life!" said Mr. Brownlow, knocking the table.

"And I for his falsehood with my head!" rejoined Mr. Grimwig, knocking the table also.

"We shall see!" said Mr. Brownlow, checking his rising anger.

"We will!" said Mr. Grimwig, with a provoking smile; "we will."

Just then Mrs. Bedwin brought in some books which had been bought of the identical book stall-keeper who has already figured in this history. Mr. Brownlow was greatly disturbed that the boy who brought them had not waited, as there were some other books to be returned.

"Send Oliver with them," suggested Mr. Grimwig, "he will be sure to deliver them safely, you know!"

"Yes; do let me take them, if you please, sir," said Oliver "I'll run all the way, sir."

Mr. Brownlow was about to refuse to have Oliver go out, when Mr. Grimwig's malicious cough made him change his mind, and let the boy go.

"You are to say," said Mr. Brownlow, "that you have brought those books back; and that you have come to pay the four pound ten I owe him. This is a five-pound note, so you will have to bring me back ten shilling change."

"I won't be ten minutes, sir," replied Oliver, eagerly, as with a respectful bow he left the room. Mrs. Bedwin watched him out of sight exclaiming, "Bless his sweet face!"—while Oliver looked gaily round, and nodded before he turned the corner.

Then Mr. Brownlow drew out his watch and waited, while Mr. Grimwig asserted that the boy would never be back. "He has a new suit of clothes on his back; a set of valuable books under his arm; and a five-pound note in his pocket. He'll join his old friends the thieves, and laugh at you. If ever that boy returns to this house, sir," said Mr. Grimwig, "I'll eat my head!"

It grew so dark that the figures on the dial-plate were scarcely discernible. The gas lamps were lighted; Mrs. Bedwin was waiting anxiously at the open door; the servant had run up the street twenty times to see if there were any traces of Oliver; and still the two old gentlemen sat, perseveringly, in the dark parlour, with the watch between them, waiting—but Oliver did not come.

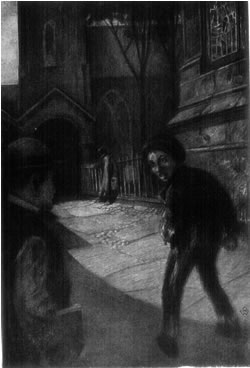

He meanwhile, had walked along, on his way to the bookstall, thinking how happy and contented he ought to feel, when he was startled by a young woman screaming out very loud, "Oh, my dear brother!"—and then he was stopped by having a pair of arms thrown tight round his neck.

"Don't!" cried Oliver, struggling. "Let go of Who is it? What are you stopping me for?"

"Oh my gracious!" said the young woman, "I've found him! Oh you naughty boy, to make me suffer sich distress on your account! Come home, dear, come!" With these and more incoherent exclamations, the young woman burst out crying, and told the onlookers that Oliver was her brother, who had run away from his respectable parents a month ago, joined a gang of thieves and almost broke his mother's heart,—to which Oliver, greatly alarmed, replied that he was an orphan, had no sister, and lived at Pentonville. Then, catching sight of the woman's face for the first time, he cried,—"Why, it's Nancy!"

"You see he knows me!" cried Nancy. "Make him come home, there's good people, or he'll kill his dear mother and father, and break my heart!" With this a man who was Nancy's accomplice, Bill Sikes by name, came to the rescue, tore the volumes from Oliver's grasp, and struck him on the head. Weak still, and stupified by the suddenness of the attack, overpowered and helpless, what could one poor child do? Darkness had set in; it was a low neighbourhood; no help was near—resistance was useless. In another moment he was dragged into a labyrinth of dark narrow courts: and was forced along them, at a pace which rendered the few cries he dared to give utterance to, unintelligible.

At length they turned into a very filthy street, and stopped at an apparently untenanted house into which Bill Sikes and Nancy led Oliver, and there, were his old friends, Charley Bates, the Dodger, and Fagin.

They greeted Oliver with cheers, and at once rifled his pockets of the five-pound note, and relieved him of the books,—although Oliver pleaded that the books and money be sent back to Mr. Brownlow. When he found that all pleading and resistance were useless, he jumped suddenly to his feet and tore wildly from the room, uttering shrieks for help which made the bare old house echo to the roof, and then attempted to dart through the door, opened for a moment, but he was instantly caught, while Sikes' dog would have sprung upon him, except for Nancy's intervention. She was struck with Oliver's pallor and great grief and tried to shield him from violence. But it was of little avail. He was beaten by the Jew, and then led off by Master Bates into an adjacent kitchen to go to bed. His new clothes were taken from him and he was given the identical old suit which he had so congratulated himself upon leaving off at Mr. Brownlow's, and the accidental display of which to Fagin, by the Jew who purchased them, had been the first clue to Oliver's whereabouts.

For a week or so the boy was kept locked up, but after that the Jew left him at liberty to wander about the house; which was a weird, ghostlike place, with the mouldering shutters fast closed, and no evidence from outside that it sheltered human creatures. Oliver was constantly with Charley Bates and the Dodger, who played the old game with the Jew every day. At times Fagin entertained the boys with stories of robberies he had committed in his younger days, which made Oliver laugh heartily, and show that he was amused in spite of his better feelings. In short, the wily old Jew had the boy in his toils, and hoped gradually to instil into his soul the poison which would blacken it and change its hue forever.

Meanwhile Fagin, Bill Sikes, and Nancy were arranging a plot in which poor Oliver was to play a notable part. One morning he found to his surprise, a pair of stout new shoes by his bedside, and at breakfast Fagin told him that he was to be taken to the residence of Bill Sikes that night, but no reason for this was given. Fagin then left him and presently Nancy came in, looking pale and ill. She came from Sikes to take Oliver to him. Her countenance was agitated and she trembled.

"I have saved you from being ill-used once, and I will again; and I do now," she said, "for those who would have fetched you if I had not, would have been far more rough than me. Remember this, and don't let me suffer more for you just now. If I could help you, I would; but I have not the power. I have promised for your being quiet; if you are not, you will harm youself and perhaps be my death. Hush! Give me your hand! Make haste!"

Blowing out the light, she drew Oliver hastily after her, out, and into a hackney-cabriolet. The driver wanted no directions, but lashed his horse into full speed, and presently they were in a strange house. There, with Nancy and Sikes, Oliver remained until an early hour the next morning, when the three set out, whither or for what Oliver did not know, but before they started Sikes drew out a pistol, and holding it close to Oliver's temple said, "If you speak a word while you're out of doors, with me, except when I speak to you, that loading will be in your head without notice!" And Oliver did not doubt the statement.

In the gray dawn of a cheerless morning the trio started off, and by continual tramping, and an occasional lift from a carter reached a public house where they lingered for some hours, and then went on again until the next night. They turned into no house at Shepperton, as the weary boy had expected; but still kept walking on, in mud and darkness, until they came in sight of the lights of a town. Then they stopped for a time at a solitary, dilapidated house, where they were met by other men. The party then crossed a bridge and were soon in the little town of Chertsey. There was nobody abroad. They had cleared the town as the church-bell struck two. After walking about a quarter of a mile, they stopped before a detached house surrounded by a wall: to the top of which one of the men, Toby Crackit, climbed in a twinkling.

"The boy next!" said Toby. "Hoist him up; I'll catch hold of him."

Before Oliver had time to look round, Sikes had caught him under the arms; and he and Toby were lying on the grass, on the other side of the wall. Sikes followed, and they stole towards the house. Now, for the first time Oliver realised that robbery, if not murder, was the object of the expedition. In vain he pleaded that they let him go,—he was answered only by oaths, while the robbers were busy opening a little window not far from the ground at the back of the house, which was just large enough to admit Oliver. Toby planted himself firmly with his head against the wall beneath the window, then Sikes, mounting upon him, put Oliver through the window with his feet first, and without leaving hold of his collar, planted him safely on the floor inside.

"Take this lantern," whispered Sikes, looking into the room, "You see the stairs afore you; go up softly and unfasten the street door."

Oliver, more dead than alive gasped out, "Yes." Sikes then advised him to take notice that he was within shot all the way; and that if he faltered, he would fall dead that instant.

"It's done in a minute," said Sikes. "Directly I leave go of you, do your work. Hark!"

"What's that?" whispered the other man.

"Nothing," said Sikes,—"Now!"

In the short time he had to collect his senses, Oliver had resolved that, whether he died in the attempt or not, he would make one effort to dart up stairs and to alarm the family. Filled with this idea, he advanced at once, but stealthily.

"Come back!" suddenly cried Sikes aloud. "Back! Back!"

Scared by the sudden breaking of the stillness and by a loud cry which followed it, Oliver let his lantern fall and knew not whether to advance or fly. The cry was repeated—a light appeared—a vision of two terrified half-dressed men at the top of the stairs swam before his eyes—a flash—a smoke—a crash somewhere,—and he staggered back.

Sikes had disappeared for an instant; but he was up again, and had Oliver by the collar before the smoke had cleared away. He fired his pistol after the men, and dragged the boy up.

"Clasp your arm tighter," said Sikes, as he drew him through the window. "Give me a shawl here. They've hit him. Quick! How the boy bleeds!"

Then came the loud ringing of a bell, mingled with the noise of fire-arms, the shouts of men, and the sensation of being carried over uneven ground at a rapid pace. Then the noises grew confused in the distance; and the boy saw or heard no more. Bill Sikes had him on his back scudding like the wind. Oliver's head hung down, and he was deadly cold. The pursuers were close upon Sikes' heels. He dropped the boy in a ditch and fled.

Hours afterwards Oliver came to himself, and found his left arm rudely bandaged hung useless at his side. He was so weak that he could scarcely move. Trembling from cold and exhaustion he made an effort to stand upright, but fell back, groaning with pain. Then a creeping stupor came over him, warning him that if he lay there he must surely die. So he got upon his feet, and stumbling on, dizzy and half unconscious, drew near to the very house which caused him to shudder with horror at the memory of last night's dreadful scene.

Within, in the kitchen all the servants were gathered round the fire discussing the attempted burglary. While Mr. Giles, the butler, was giving his version of the affair, there came a timid knock. They opened the door cautiously and beheld poor little Oliver Twist, speechless and exhausted, who raised his heavy eyes and mutely solicited their compassion. Instantly there was an outcry, and Oliver was seized by one leg and one arm, lugged into the hall, and laid on the floor. "Here he is!" bawled Giles up the staircase; "here's one of the thieves, ma'am! Here's a thief, miss! Wounded, miss. I shot him, miss; and Brittles held the light!" There was great confusion then, all the servants talking at once, but the sound of a sweet voice from above quelled the commotion. On learning that a wounded thief was lying in the house, the voice directed that he be instantly carried up-stairs to the room of Mr. Giles, and a doctor be summoned; and so for the second time in his short, tragic existence, Oliver fell into kind hands at a moment when all hope had left his breast. He was now in the home of Mrs. Maylie, a finely preserved, bright-eyed, elderly lady, and her fair young adopted niece, Rose.

The attempted burglary had greatly shocked them both, and the fact that one of the robbers was in the house added to their nervousness. So when Dr. Losberne came, and begged them to accompany him to the patient's room, they dreaded to comply with the request, but finally yielded to his demand. What was their astonishment when the bed-curtains were drawn aside, instead of a black-visaged ruffian, to see a mere child, worn with pain, and sunk into a deep sleep. His wounded arm bound and splintered up, was crossed upon his breast. His head reclined upon the other arm, which was half hidden by his long hair, as it streamed over the pillow. The boy smiled in his sleep as at a pleasant dream, when Rose bent tenderly over him, while the older lady and the Doctor discussed the probability of the child's having been the tool of robbers. Fearing that the doctor might influence her aunt to send the boy away, Rose pleaded that he be kept and cared for; it was finally decided that when Oliver awoke he should be examined as to his past life, and if the result seemed satisfactory, he should remain. But not until evening was he able to be questioned. He then told them all his simple history. It was a solemn thing to hear the feeble voice of the sick child recounting a weary catalogue of evils and calamities which hard men had brought upon him, and his hearers were profoundly moved by the recital. His pillow was smoothed by gentle hands that night and he slept as sleep the calm and happy.

On the following day, officers who had heard of the burglary, and that a thief was prisoner in the Maylie house, came from London to arrest him, but Dr. Losberne and Mrs. Maylie shielded him, and their joint bail was accepted for the boy's appearance in court if it should ever be required.

With the Maylies Oliver remained, and thanks to their tender care, gradually throve and prospered, although it was long weeks before he was quite himself again. Many times he spoke to the two sweet ladies of his gratitude to them, saying that he only desired to serve them always. To this they responded that he should go with them to the country, and there could serve them in a hundred ways.

Only one cloud was on Oliver's sky. He longed to go to Mr. Brownlow and tell him the true story of his seeming ingratitude. So as soon as he was sufficiently recovered, Dr. Losberne drove him out to the place where he said Mr. Brownlow resided. They hastened to the house, but alas! it was empty. There was a bill in the window, "To Let" and upon inquiring, they found that Mr. Brownlow, Mr. Grimwig, and Mrs. Bedwin had gone to the West Indies.

The disappointment was a cruel one, for all through his sickness Oliver had anticipated the delight of seeing his first benefactor, and clearing himself of guilt, but now that was impossible.

In a fortnight the Maylies went to the country, and Oliver, whose life had been spent in squalid crowds, seemed to enter on a new existence there. The sky and the balmy air, the woods and glistening water, the rose and honeysuckle, were each a daily joy to him. Every morning he went to a white-haired old gentleman who taught him to read better and to write, then he would walk and talk with Rose and Mrs. Maylie, and so three happy months glided away.

In the summer Rose was taken down with a terrible fever, and anxiety hung like a cloud over the cottage where she was so dear, but at length the danger passed and the loving hearts grew lighter again.

Meanwhile a man named Monks,—a friend of Fagin's—had by chance seen Oliver, had been strangely excited and angered at sight of him, and after carefully learning some details of the boy's history, had gone to the beadle at the workhouse where Oliver began life, and by dint of bribes, had extorted information concerning Oliver's mother, which only one person knew. Satisfied with what he learned, Monks conferred with Fagin, telling some facts about Oliver which caused Nancy, who happened to overhear them, to become terror-stricken.

As soon as she could, she stole away from her companions, out towards the West End of London, to a hotel where the Maylies were then boarding, and which she had heard Monks mention. Nancy was such a ragged object that she found it difficult to have her name carried up to Rose Maylie, but at length she succeeded, and was ushered into the sweet young lady's presence, where she quickly related what she had come to tell. That Monks had accidentally seen Oliver, and found out where he was living, and with whom;—that a bargain had been struck with Fagin that he should have a certain sum of money if Oliver were brought back, and a still larger amount if the boy could be made a thief. Nancy then went on to tell that Monks spoke of Oliver as his young brother, and boasted that the proofs of the boy's identity lay at the bottom of the river—that he, Monks, had money which by right should have been shared with Oliver, and that his one desire was to take the boy's life.

These disclosures made Rose Maylie turn pale, and ask many questions, from which she discovered that Nancy's confession was actuated by a real liking for Oliver and a fierce hatred for the man Monks. Her tale finished, and refusing money, or help of any kind, Nancy went as swiftly as she had come, and when she left, Rose sank into a chair completely overcome by what she had heard.

Of course the matter was too serious to pass over, and the next day, as Rose was trying to decide upon a course of action, Oliver settled it for her, by rushing in with breathless haste, and exclaiming, "I have seen the gentleman—the gentleman who was so good to me—Mr. Brownlow!"

"Where?" asked Rose.

"Going into a house," replied Oliver. "And Giles asked, for me, whether he lived there, and they said he did. Look here," producing a scrap of paper, "here it is; here's where he lives—I'm going there directly! OH, DEAR ME! DEAR ME! what shall I do when I come to hear him speak again!"

With her attention not a little distracted by these exclamations of joy, an idea came to Rose, and she determined upon turning this discovery to account.

"Quick!" she said, "tell them to fetch a hackney-coach, and be ready to go with me. I will take you to see Mr. Brownlow directly."

Oliver needed no urging and they were soon on their way to Craven Street. When they arrived, Rose left Oliver in the coach, and sending up her card, requested to see Mr. Brownlow on business. She was shown up stairs, and presented to Mr. Brownlow, an elderly gentleman of benevolent appearance, in a bottle-green coat, and with him was his friend, Mr. Grimwig. Rose began at once upon her errand, to the great amazement of the two old gentlemen. She related in a few natural words all that had befallen Oliver since he left Mr. Brownlow's house, concluding with the assurance that his only sorrow for many months had been the not being able to meet with his former benefactor and friend.

"Thank God!" said Mr. Brownlow. "This is great happiness to me; great happiness! But why not have brought him?"

"He is waiting in a coach at the door," replied Rose.

"At this door!" cried Mr. Brownlow. With which he hurried down the stairs, without another word, and came back with Oliver. Then Mrs. Bedwin was sent for. "God be good to me!" she cried, embracing him; "it is my innocent boy! He would come back—I knew he would! How well he looks, and how like a gentleman's son he is dressed again! Where have you been, this long, long while?"

Running on thus,—now holding Oliver from her, now clasping him to her and passing her fingers through his hair, the good soul laughed and wept upon his neck by turns.

Leaving Oliver with her, Mr. Brownlow led Rose into another room, by her request, and she narrated her interview with Nancy, which occasioned Mr. Brownlow no small amount of perplexity and surprise. After a long consultation they decided to take Mrs. Maylie and Dr. Losberne into their confidence, also Mr. Grimwig, thus forming a committee for the purpose of guarding the young lad from further entanglement in the plots of villains.

Through Nancy, with whom Rose had another interview, the man Monks was tracked, and finally captured by Mr. Brownlow, who to his sorrow, found that the villain was the erring son of his oldest friend, and his name of Monks only an assumed one. Facing him in a room of his own house, to which Monks had been brought,—Mr. Brownlow charged the man with one crime after another.

The father of Monks had two children who were half brothers, Monks and Oliver Twist. The father died suddenly, leaving in Mr. Brownlow's home the portrait of Oliver's mother, which was hanging in the house-keeper's room. The striking likeness between this portrait and Oliver had led Mr. Brownlow to recognise the boy as the child of his dear old friend. Then, just when he had determined to adopt Oliver, the boy had disappeared, and all efforts to find him had proved unavailing. Mr. Brownlow knew that, although the mother and father were dead, the elder brother was alive, and at once commenced a search for him. Now he had discovered him in the man Monks, the friend of thieves and murderers, and by a chance clue he found also that there had been a will, dividing the property between the two brothers. That will had been destroyed, together with all proofs of Oliver's parentage, so that Monks might have the entire property. Fearing discovery, Monks had bargained with Fagin to keep the child a thief or to kill him outright.

This revelation of his crime in all its terrible details, told in clear cutting tones by Mr. Brownlow, while his eyes never left the man's face, overwhelmed the coward Monks. He stood convicted, and confessed his guilt.

Then, because the man was son of his old friend, Mr. Brownlow was merciful.

"Will you set your hand to a statement of truth and facts, and repeat it before witnesses?" he asked.

"That I promise," said Monks.

"Remain quietly here until such a document is drawn up, and proceed with me to such a place as I may deem advisable, to attest it?"

To this also Monks agreed.

"You must do more than that," said Mr. Brownlow; "Make restitution to Oliver. You have not forgotten the provisions of the will. Carry them into execution so far as your brother is concerned, and then go where you please. In this world you need meet no more."

To this also, at length Monks gave fearing assent.

A few days later Oliver found himself in a travelling carriage rolling fast towards his native town, with the Maylies, Mrs. Bedwin, Dr. Losberne, and Mr. Grimwig, while Mr. Brownlow followed in a post-chaise with Monks.

Oliver was much excited, for he had been told of the disclosures of Monks, which, together with journeying over a road which he had last travelled on foot, a poor houseless, wandering boy, without a friend, or a roof to shelter his head, caused his heart to beat violently and his breath to come in quick gasps.

"See there, there!" he cried, "that's the stile I came over; there are the hedges I crept behind, for fear anyone should overtake me and force me back!"

As they approached the town, and drove through its narrow streets, it became matter of no small difficulty to restrain the boy within reasonable bounds. There was the undertaker's just as it used to be, only less imposing in appearance than he remembered it. There was the workhouse, the dreary prison of his youthful days; there was the same lean porter standing at the gate. There was nearly everything as if he had left it but yesterday, and all his recent life had been a happy dream.

They drove at once to the hotel where Mr. Brownlow joined them with Monks, and there in the presence of the whole party, the wretched man made his full confession of guilt, and surrendered one half of the property—about three thousand pounds—to his half-brother, upon whom even as he spoke, he cast looks of hatred so violent that Oliver trembled. From some details of his confession it was also discovered that Rose Maylie, who was only an adopted niece of Mrs. Maylie, had been the sister of Oliver's mother, and was therefore the boy's aunt, the first blood relation, except Monks, that he had ever possessed.

"Not aunt," cried Oliver, throwing his arms about her neck, "I'll never call her aunt. Sister, my own, dear sister, that something taught my heart to love so dearly from the first, Rose! dear, darling Rose!" And in Rose's close embrace, the boy found compensation for all his past sadness.

The only link to his old life which remained was soon broken. Fagin had been captured too, sentenced to death, and was in prison awaiting the fulfilment of his doom. In his possession he had papers relating to Oliver's parentage, and the boy went with Mr. Brownlow to the prison to try to recover them. With Mr. Brownlow, Fagin was obstinately silent, but to Oliver he whispered where they could be found, and then begged and prayed the boy to help him escape justice, and sent up cry after cry that rang in Oliver's ears for months afterwards.

But youth and sorrow are seldom companions for long, and our last glimpse of Oliver is of a boy as thoroughly happy as one often is. He is now the adopted son of the good Mr. Brownlow. Removing with him and Mrs. Bedwin to within a mile of the Maylies' home, Mr. Brownlow gratified the only remaining wish of Oliver's warm and earnest heart, and as the happy days go swiftly by, the past becomes the shadow of a dream.

Several times a year Mr. Grimwig visits in the neighbourhood, and it is a favourite joke for Mr. Brownlow to rally him on his old prophecy concerning Oliver, and to remind him of the night on which they sat with the watch between them awaiting his return. But Mr. Grimwig contends that he was right in the main, and in proof thereof remarks that Oliver did not come back after all,—which always calls forth a laugh on his side, and increases his good humour.

Poor Traddles! In a tight sky-blue suit that made his arms and legs like German sausages, or roly-poly puddings, and with his hair standing upright, giving him the expression of a fretful porcupine, he was the merriest and most miserable of all the boys at Mr. Creakle's school, called Salem House. I never think of him without a strange disposition to laugh, and yet with tears in my eyes.

He was always being caned—I think he was caned every day in the half-year I spent at Salem House, except one holiday Monday when he was only ruler'd on both hands—and was always going to write to his uncle about it, and never did. After laying his head on the desk for a little while, he would cheer up somehow, begin to laugh again, and draw skeletons all over his slate, before his eyes were dry. I used at first to wonder what comfort Traddles found in drawing skeletons; and for some time looked upon him as a sort of a hermit, who reminded himself by those symbols of mortality that caning couldn't last for ever. But I believe he only did it because they were easy, and didn't want any features.

He was very honourable, Traddles was; and held it as a solemn duty in the boys to stand by one another. He suffered for this code of honour on several occasions. One evening we had a great spread up in our room after time for lights to be down, and we all got happily out of it but Traddles. He was too unfortunate even to come through a supper like anybody else. He was taken ill in the night—quite prostrate he was—in consequence of Crab; and after being drugged to an extent which Demple (whose father was a doctor) said was enough to undermine a horse's constitution, received a caning and six chapters of Greek Testament for refusing to confess.

At another time, when Steerforth (who was the only parlour-boarder and the lion of the school) laughed in church, the Beadle, who thought the offender was Traddles, took him out. I see him now, going away in custody, despised by the congregation. He never said who was the real offender, although he smarted for it next day, and was imprisoned so many hours that he came forth with a whole churchyardful of skeletons swarming all over his Latin dictionary. But he had his reward. Steerforth said there was nothing of the sneak in Traddles, and we all felt that to be the highest praise.

On still a third occasion during my half-year at Salem House I have a vivid recollection of Traddles in distress; that time for siding with the down-trodden under-teacher, Mr. Mell, in a heated discussion between that gentleman and Steerforth.

The discussion took place on a Saturday which should have properly been a half-holiday, but as Mr. Creakle was indisposed, and the noise in the playground would have disturbed him; and the weather was not favourable for going out walking, we were ordered into school in the afternoon, and set some lighter tasks than usual; and Mr. Mell, a pale, delicately-built, little man, was detailed to keep us in order, which he tried in vain to accomplish.

Boys started in and out of their places, playing at puss-in-the-corner with other boys; there were laughing boys, singing boys, talking boys, dancing boys, howling boys; boys shuffled with their feet, boys whirled about him, grinning, making faces, mimicking him behind his back and before his eyes: mimicking his poverty, his boots, his coat, his mother, every thing belonging to him that they should have had consideration for.

"Silence!" cried Mr. Mell, suddenly rising up, and striking his desk with the book. "What does this mean! It's impossible to bear it. It's maddening. How can you do it to me, boys?"

The boys all stopped, some suddenly surprised, some half afraid, and some sorry perhaps.

Steerforth alone remained in his lounging position, hands in his pockets, and looked at Mr. Mell with his mouth shut up as if he were whistling, when Mr. Mell looked at him.

"Silence, Mr. Steerforth!" said Mr. Mell.

"Silence yourself," said Steerforth, turning red. "Whom are you talking to?"

"Sit down!" said Mr. Mell.

"Sit down yourself!" said Steerforth, "and mind your business."

There was a titter and some applause; but Mr. Mell was so white, that silence immediately succeeded.

"When you make use of your position of favouritism, here, sir," pursued Mr. Mell, with his lip trembling very much, "to insult a gentleman——"

"A what?—where is he?" said Steerforth.

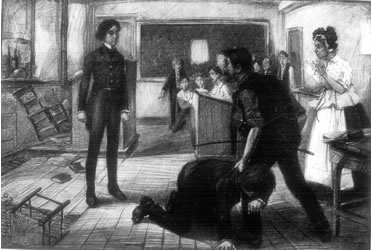

Here somebody cried out, "Shame, J. Steerforth! Too bad!" It was Traddles; whom Mr. Mell instantly discomfited by bidding him to hold his tongue,——

"—to insult one who is not fortunate in life, sir, and who never gave you the least offence, and the many reasons for not insulting whom you are old enough and wise enough to understand," said Mr. Mell, with his lip trembling more and more, "you commit a mean and base action. You can sit down or stand up as you please, sir."

"I tell you what, Mr. Mell," said Steerforth, coming forward, "once for all. When you take the liberty of calling me mean or base, or anything of that sort, you are an impudent beggar. You are always a beggar, you know; but when you do that, you are an impudent beggar."

Had Mr. Creakle not entered the room at that moment, there is no knowing what might have happened, for the highest pitch of excitement had been reached by combatants and lookers-on.

Both Steerforth and the under-teacher at once turned to Mr. Creakle, pouring out in his attentive ear the story of the burning wrong to which each had subjected the other, and the end of the whole affair was that Mr. Mell—having discovered that Mr. Creakle's veneration for money, and fear of offending his head-pupil, far outweighed any consideration for the teacher's feelings,—taking his flute and a few books from his desk, and leaving the key in it for his successor, went out of the school, with his property under his arm.

Mr. Creakle then made a speech, in which he thanked Steerforth for asserting (though perhaps too warmly) the independence and respectability of Salem House; and which he wound up by shaking hands with Steerforth; while we gave three cheers—I did not quite know what for, but I supposed for Steerforth, and joined in them, though I felt miserable. Mr. Creakle then caned Tommy Traddles for being discovered in tears, instead of cheers, and went away leaving us to ourselves.

Steerforth was very angry with Traddles, and said he was glad he had caught it. Poor Traddles, who had passed the stage of lying with his head upon the desk, and was relieving himself as usual with a burst of skeletons, said he didn't care. Mr. Mell was ill-used.

"Who has ill-used him, you girl?" said Steerforth.

"Why, you have," returned Traddles.

"What have I done?" said Steerforth.

"What have you done?" retorted Traddles. "Hurt his feelings and lost him his situation."

"His feelings!" repeated Steerforth, disdainfully. "His feelings will soon get the better of it, I'll be bound. His feelings are not like yours, Miss Traddles! As to his situation—which was a precious one, wasn't it?—do you suppose I am not going to write home and take care that he gets some money?"

We all thought this intention very noble in Steerforth, whose mother was a rich widow, and, it was said, would do anything he asked her. We were all very glad to see Traddles so put down, and exalted Steerforth to the skies, and none of us appreciated at that time that our hero, J. Steerforth was very, very small indeed, as to character, in comparison to funny, unfortunate Tommy Traddles.

Years later, when Salem House was only a memory, and we were both men, Traddles and I met again. He had the same simple character and good temper as of old, and had, too, some of his old unlucky fortune, which clung to him always; yet notwithstanding that—as all of his trouble came from good-natured meddling with other people's affairs, for their benefit, I am not at all certain that I would not risk my chance of success—in the broadest meaning of that word—in the next world surely, if not in this, against all the Steerforths living, if I were Tommy Traddles.

Poor Traddles?—No, happy Traddles!

They were certainly the very oddest pair that ever the moon shone on,—Stony Durdles and the boy "Deputy."

Durdles was a stone-mason, from which occupation, undoubtedly, came his nickname "Stony," and Deputy was a hideous small boy hired by Durdles to pelt him home if he found him out too late at night, which duty the boy faithfully performed. In all the length and breadth of Cloisterham there was no more noted man than the stone-mason, Durdles, not, I regret to say, on account of his virtues, but rather because of his talent for remaining out late at night, and not being able to guide his steps homeward. There is a coarser term which might have been applied to this talent of Durdles, but we have nothing to do with that, here and now; what we desire is an introduction to the small boy who is Durdles's shadow.

One night, John Jasper, choir-master in Cloisterham Cathedral, on his way home through the Close, is brought to a standstill by the spectacle of Stony Durdles, dinner-bundle and all, leaning against the iron railing of the burial-ground, while a hideous small boy in rags flings stones at him, in the moonlight. Sometimes the stones hit him, and sometimes they miss him, but Durdles seems indifferent to either fortune. The hideous small boy, on the contrary, whenever he hits Durdles, blows a whistle of triumph through a jagged gap in the front of his mouth, where half his teeth are wanting; and whenever he misses him, yelps out, "Mulled agin!" and tries to atone for the failure by taking a more correct and vicious aim.

"What are you doing to the man?" demands Jasper.

"Makin' a cock-shy of him," replies the hideous small boy.

"Give me those stones in your hand."

"Yes, I'll give 'em you down your throat, if you come a ketchin' hold of me," says the small boy, shaking himself loose from Jasper's touch, and backing. "I'll smash your eye if you don't look out!"

"What has the man done to you?"

"He won't go home."

"What is that to you?"

"He gives me a 'apenny to pelt him home if I ketches him out too late," says the boy. And then chants, like a little savage, half stumbling, and half dancing, among the rags and laces of his dilapidated boots,——

Widdy widdy wen!

I—ke—ches—'im out—ar—ter ten,

Widdy widdy wy!

Then—'E—don't—go—then—I shy,

Widdy widdy Wakecock warning!

—with a sweeping emphasis on the last word, and one more shot at Durdles. The bit of doggerel is evidently a sign which Durdles understands to mean either that he must prove himself able to stand clear of the shots, or betake himself immediately homeward, but he does not stir.

John Jasper crosses over to the railing where the Stony One is still profoundly meditating.

"Do you know this thing, this child?" he asks.

"Deputy," says Durdles, with a nod.

"Is that its—his—name?"

"Deputy," assents Durdles, whereupon the small boy feels called upon to speak for himself.

"I'm man-servant up at the Travellers Twopenny in Gas Works Garding," he explains. "All us man-servants at Travellers Lodgings is named Deputy, but I never pleads to no name, mind yer. When they says to me in the Lockup, 'What's your name?' I says to 'em 'find out.' Likewise when they says, 'What's your religion?' I says, 'find out'!" After delivering himself of this speech, he withdraws into the road and taking aim, he resumes:——

Widdy widdy wen!

I—ket—ches—'im—out—ar—ter—

"Hold your hand!" cries Jasper, "and don't throw while I stand so near him, or I'll kill you! Come Durdles, let me walk home with you to-night. Shall I carry your bundle?"

"Not on any account," replies Durdles, adjusting it, and continuing to talk in a rambling way, as he and Jasper walk on together.

"This creature, Deputy, is behind us," says Jasper, looking back. "Is he to follow us?"

The relations between Durdles and Deputy seem to be of a capricious kind, for on Durdles turning to look at the boy, Deputy makes a wide circuit into the road and stands on the defensive.

"You never cried Widdy Warning before you begun tonight," cries Durdles, unexpectedly reminded of, or imagining an injury.

"Yer lie; I did," says Deputy, in his only polite form of contradiction, whereupon Durdles turns back again and forgets the offence as unexpectedly as he had recalled it, and says to Jasper, in reference to Deputy.

"Own brother, sir, to Peter, the Wild Boy! But I gave him an object in life."

"At which he takes aim?" Mr. Jasper suggests.

"That is it, sir," returns Durdles; "at which he takes aim. I took him in hand and gave him an object. What was he before? A destroyer. What work did he do? Nothing but destruction. What did he earn by it? Short terms in Cloisterham jail. Not a person, not a piece of property, not a winder, not a horse, nor a dog, nor a cat, nor a bird, nor a fowl, nor a pig, but that he stoned for want of an enlightened object. I put that enlightened object before him, and now he can turn his honest halfpenny by the three pennorth a week."

"I wonder he has no competitors."

"He has plenty, Mr. Jasper, but he stones 'em all away."

"He still keeps behind us," repeats Jasper, looking back, "is he to follow us?"

"We can't help going round by the Travellers Twopenny, if we go the short way, which is the back way," Durdles answers, "and we'll drop him there."

So they go on; Deputy attentive to every movement of the Stony One, until at length nearly at their destination Durdles whistles, and calls—"Holloa, you Deputy!"

"Widdy!" is Deputy's shrill response, standing off again.

"Catch that ha'penny. And don't let me see any more of you to-night, after we come to the Travellers Twopenny."

"Warning!" returns Deputy, having caught the halfpenny, and appearing by this mystic word to express his assent to the arrangement, then off he darts.