Title: The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 12, No. 348, December 27, 1828

Author: Various

Release date: March 1, 2004 [eBook #11445]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Jonathan Ingram, Keith M. Eckrich, David Garcia, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction, Vol. 12, Issue 348, December 27, 1828, by Various

| VOL. XII, NO. 348.] | SATURDAY, DECEMBER 27, 1828. | [PRICE 2d. |

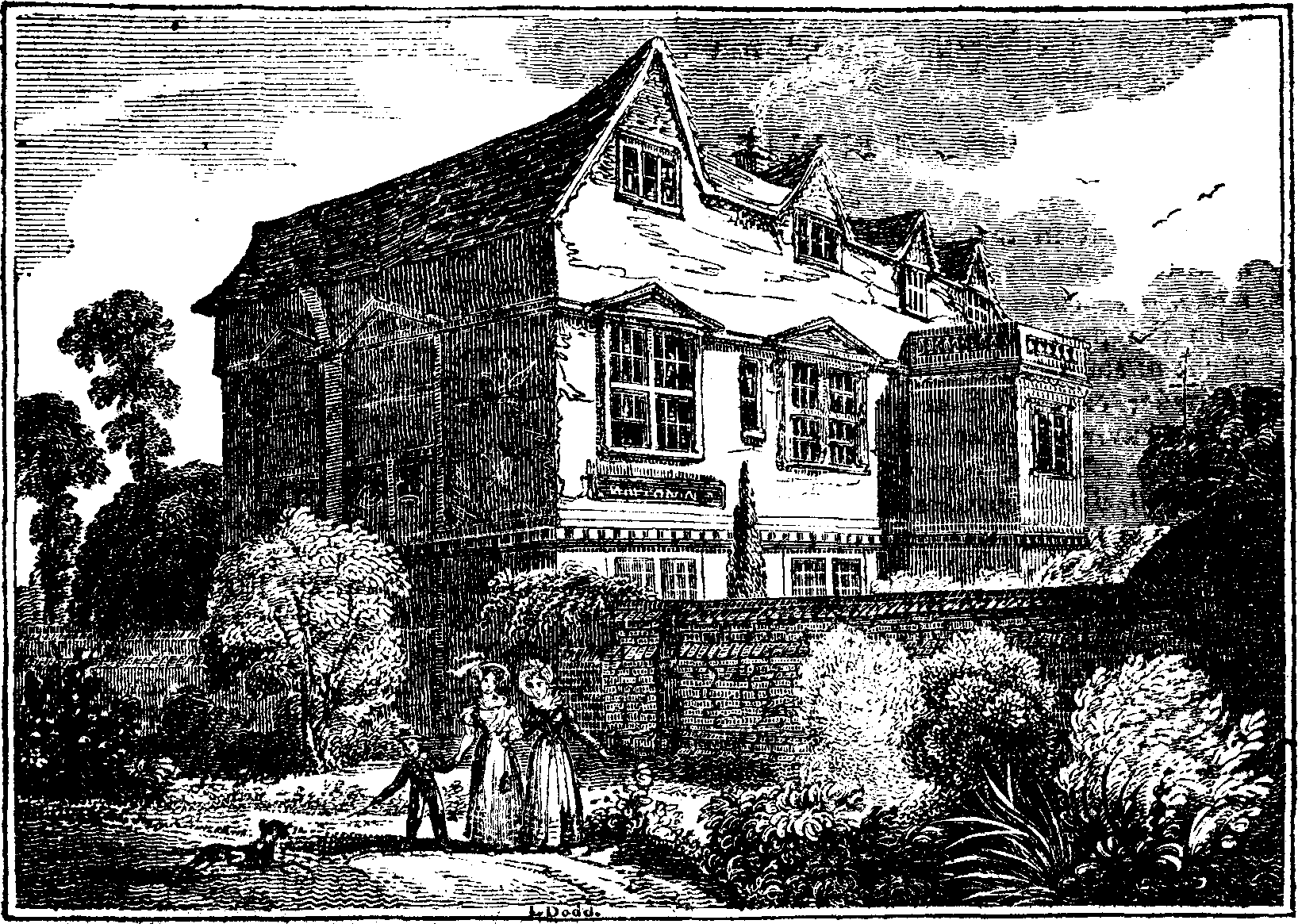

The engraving represents a place of historical interest—an ancient mansion in Mare-street, Hackney, built about the year 1591, upon a spot of ground called Barbour Berns, by which name, or rather Barber's Barn, the house has been described in old writings.

In this house resided the noted Colonel John Okey, one of the regicides "charged with compassing and imagining the death of the late King Charles I." in October, 1660. Nineteen of these "bold traitors," (among whom was Okey,) fled from justice, and were attainted, and Barber's Barn was in his tenure at the time of his attainder. His interest in the premises being forfeited to the crown, was granted to the Duke of York, who, by his indenture, dated 1663, gave up his right therein to Okey's widow. The colonel was apprehended in Holland, with Sir John Berkestead and Miles Corbett, in 1662, whence they were sent over to England; and having been outlawed for high treason, a rule was made by the Court of King's Bench for their execution at Tyburn. These were the last of the regicides that were punished capitally.

Barber's Barn and its adjoining grounds have, however, since become appropriated to more pacific pursuits than hatching treason, compassing, &c. About the middle of the last century, one John Busch cultivated the premises as a nursery. Catharine II. Empress of Russia, says a correspondent of Mr. Loudon's Gardener's Magazine, "finding she could have nothing done to her mind, she determined to have a person from England to lay out her garden." Busch was the person engaged to go out to Russia for this purpose; and in the year 1771 he gave up his concerns at Hackney, with the nursery and foreign correspondence, to Messrs. Loddidges. These gentlemen, who rank as the most eminent florists and nurserymen of their time, have here extensive green and hot houses which are heated by steam; the ingenious apparatus belonging to which has been principally devised by themselves. Their gardens boast of the finest display of exotics ever assembled in this country, and a walk through them is one of the most delightful spectacles of Nature.

Hackney was once distinguished by princely mansions; but, alas! many of these abodes of wealth have been turned [pg 434] into receptacles for lunatics! Brooke House, formerly the seat of a nobleman of that name, and Balmes' House, within memory surrounded by a moat, and approached only by a drawbridge, have shared this humiliating fate. Sir Robert Viner,1 who made Charles II. "stay and take t'other bottle," resided here; and John Ward, Esq. M.P. whom Pope has "damned to everlasting fame," had a house at Hackney.

(For the Mirror.)

The pulpit in the church of St. Peter, at Wolverhampton, is formed wholly of stone. It consists of one entire piece, with the pedestal which supports it, the flight of steps leading to it, with the balustrade, &c., without any division, the whole having been cut out of a solid block of stone. The church was erected in the year 996, at which time it is said this remarkable pulpit was put up; and notwithstanding its great age, which appears to be 832 years, it is still in good condition. At the foot of the steps is a large figure, intended to represent a lion couchant, but carved after so grotesque a fashion, as to puzzle the naturalist in his attempts to determine its proper classification. In other respects the ornamental sculpture about the pulpit is neat and appropriate, and presents a curious specimen of the taste of our ancestors at that early period.

This is a collegiate church, with a fine embattled tower, of rich Gothic architecture, and was originally dedicated to the Virgin, but altered in the time of Henry III. to St. Peter. It is pleasantly situated on a gravelly hill, and commands a fine prospect towards Shropshire and Wales.

A CORRESPONDENT.

(For the Mirror.)

It was but yesterday the snow

Of thy dead sire was on the hill—

It was but yesterday the flow

Of thy spring showers increased the rill,

And made a thousand blossoms swell

To welcome summer's festival.....

And now all these are of the past,

For this lone hour must be thy last!

Thou must depart! where none may know—

The sun for thee hath ever set,

The star of morn, the silver bow,

No more shall gem thy coronet

And give thee glory; but the sky

Shall shine on thy posterity!...

So there's an end of 1828; "all its great and glorious transactions are now nothing more than mere matter of history!" What wars of arms and words! what lots of changes and secessions! what debates on "guarantee," "stipulations," and "untoward" events! what "piles of legislation!" what a fund of speculation for the denizens of the stock-exchange, and newspaper press!—all may now be embodied in that little word—the past; and only serve to fill up and figure in the pages of the next "Annual Register!"—sic transit gloria—"but the proverb is somewhat musty." One, two, three.... ten, eleven, twelve, and now "methinks my soul hath elbow room."

Those versed in the lore of Francis Moore, physician, which must doubtless include most of our readers, are aware that our veteran friend, eighteen hundred and twenty-eight, has been for some time in what is called a "galloping" consumption, and it is certain cannot possibly survive after the bells "chime twelve" on Wednesday night, the thirty-first of December,—

"—as if an angel spoke,

I hear the solemn sound,"

when he will depart this life, and be gathered to his ancestors, who have successively been entombed in the vault of Time.

Well, taking all things into consideration, we predict he will not have many mourners in his train. "Rumours of wars" have gone through the land, and the ominous hieroglyphics of "Raphael" in his "Prophetic Messenger," unfold to the lover of futurity, that "war with all its bloody train," will visit this quarter of the globe with unusual severity the coming year—and we have had comets and "rumours" of comets for many months past, while the red and glaring appearance of the planet, Mars, is as we have elsewhere observed, considered by the many a forerunner, and sign of long wars and much bloodshed. To dwell further on the political horizon, or the [pg 435] "events and fortunes" of the past year would be out of place in the fair pages of the MIRROR; and should it be our fate to present its readers with future "notings" on another year, we will then dwell upon the good or ill-fortune of Turk or Russian to the quantum suff. of the most inveterate politician.

"Enough of this:" 1828 has nearly got the "go-by" and we have outlived its pains and perils, its varied scenes of good or evil, and its pleasures too, for there is a bright side to human reverse and suffering, and we are ready at our posts to enact and stand another campaign in this "strange eventful history." We often find that the public discover virtues and good qualities in a man after his death, which they had previously given him no credit for; let this be as it may, 1828 may be deemed a very "passable" year. To use a simile, a sick man when recovering from a fever, makes slow progress at first; and we should fairly hope that the gallant ship is at last weathering the hurricane of the "commercial crisis," and that the trade-winds of prosperity will again visit us and extend their balmy influence over our shores; and to borrow a commercial phrase, we trust to be able to quote an improvement on this head next year.

I stood between the meeting years

The coming and the past,

And I ask'd of the future one

Wilt thou be like the last?

The same in many a sleepless night,

In many an anxious day?

Thank heaven! I have no prophet's eye,

To look upon thy way!

L.E.L.

The march of mind is progressing, and the once boasted "wisdom of our ancestors" and the "golden days of good Queen Bess," are hurled with derision to the tomb of all the Capulets. We regret that we cannot chronicle a "Narrative of a first attempt to reach the cities of Bath and Bristol, in the year 1828, in an extra patent steam-coach, by Messrs. Burstall, or Gurney." The newspapers, however, still continue to inform us that such vehicles are about to start, so we may reasonably expect that Time will accomplish the long talked of event. Nay, we even hear it rumoured that the public are shortly to crest the billows in a steamer at the rate of fifty or a hundred miles an hour! and this is mentioned as a mere first essay, an immature sample of what the improved steam-paddles are to effect—also in Time; who after this can doubt the approaching perfectibility of Mars? Oh, steam! steam! but this is well ploughed ground.

Art, science, and literature, also progress, and we almost begin to fear we shall soon be puzzled where to stow the books, and anticipate a dearth in rags, an extinction of Rag-Fair! (which will keep the others in countenance,) the booksellers' maws seem so capacious. Christmas with its rare recollections of feasting (and their pendant of bile and sick headache) has again come round. New Year's Day, and of all the days most "rich and rare," Twelfth Day is coming! But it is in Scotland that the advent of the new year, or Hogmanay is kept with the most hilarity; the Scotch by their extra rejoicings at this time, seem to wish to make up for their utter neglect of Christmas. We may be induced to offer a few reminiscences of a sojourn in the north, at this period, on a future occasion. The extreme beauty of the following lines on the year that is past, will, we think, prove a sufficient apology for their introduction here:—

In darkness, in eternal space,

Sightless as a sin-quenched star,

Thou shalt pursue thy wandering race,

Receding into regions far—

On thee the eyes of mortal men

Shall never, never light again;

Memory alone may steal a glance

Like some wild glimpse in sleep we're taking.

Of a long perish'd countenance

We have forgotten when awaking—

Sad, evanescent, colour'd weak,

As beauty on a dying cheek.

Farewell! that cold regretful word

To one whom we have called a friend—

Yet still "farewell" I must record

The sign that marks our friendship's end.

Thou'rt on thy couch of wither'd leaves,

The surly blast thy breath receives,

In the stript woods I hear thy dirge,

Thy passing bell the hinds are tolling

Thy death-song sounds in ocean's surge,

Oblivion's clouds are round thee rolling,

Thou'lst buried be where buried lie

Years of the dead eternity!

It is needless to add that our old friend will be succeeded in his title and estates by his next heir, eighteen hundred and twenty-nine, whose advent will no doubt be generally welcomed. We cannot help picturing to ourselves the anxiety, the singularly deep and thrilling interest, which universally prevails as his last hour approaches:—

"Hark the deep-toned chime of that bell

As it breaks on the midnight ear—

Seems it not tolling a funeral knell?

'Tis the knell of the parting year!

Before that bell shall have ceas'd its chime

The year shall have sunk on the ocean of Time!"

And shall we go on after this lone hour? no, we will even follow its course, draw this article to a close by wishing our readers, in the good old phrase, "a happy New Year and many of them;" and conclude with them, that

Our pilgrimage here

By so much is shorten'd—then fare thee well Year!

VYVYAN.

(For the Mirror.)

Tell me, thou god of slumbers! why

Thus from my pillow dost thou fly?

And wherefore, stranger to thy balmy power,

Whilst death-like silence reigns around,

And wraps the world in sleep profound,

Must I alone count every passing hour?

And, whilst each happier mind is hush'd in sleep,

Must I alone a painful vigil keep,

And to the midnight shades my lonely sorrows pour?

Once more be thou the friend of woe,

And grant my heavy eyes to know

The welcome pressure of thy healing hand;

So shall the gnawing tooth of care

Its rude attacks awhile forbear,

Still'd by the touch of thy benumbing wand—

And my tir'd spirit, with thy influence blest,

Shall calmly yield it to the arms of rest,

But which, or comes or flies, only at thy command!

Yet if when sleep the body chains

In sweet oblivion of its pains,

Thou bid'st imagination active wake,

Oh, Morpheus! banish from my bed

Each form of grief, each form of dread,

And all that can the soul with horror shake:

Let not the ghastly fiends admission find,

Which conscience forms to haunt the guilty mind—

Oh! let not forms like these my peaceful slumbers break!

But bring before my raptured sight

Each pleasing image of delight,

Of love, of friendship, and of social joy;

And chiefly, on thy magic wing

My ever blooming Mary bring,

(Whose beauties all my waking thoughts employ,)

Glowing with rosy health and every charm

That knows to fill my breast with soft alarm,

Oh, bring the gentle maiden to my fancy's eye!

Not such, as oft my jealous fear

Hath bid the lovely girl appear,

Deaf to my vows, by my complaints unmov'd,

Whilst to my happier rival's prayer,

Smiling, she turns a willing ear,

And gives the bliss supreme to be belov'd:

Oh, sleep dispensing power! such thoughts restrain,

Nor e'en in dreams inflict the bitter pain,

To know my vows are scorn'd—my rivals are approv'd!

Ah, no! let fancy's hand supply

The blushing cheek, the melting eye,

The heaving breast which glows with genial fire;

Then let me clasp her in my arms,

And, basking in her sweetest charms,

Lose every grief in that triumphant hour.

If Morpheus, thus thou'lt cheat the gloomy night,

For thy embrace I'll fly day's garish light,

Nor ever wish to wake while dreams like this inspire!

HUGH DELMORE.

(For the Mirror.)

It has been somewhere asserted, that "no one is idle who can do any thing. It is conscious inability, or the sense of repeated failures, that prevents us from undertaking, or deters us from the prosecution of any work." In answer to this it may be said, that men of very great natural genius are in general exempt from a love of idleness, because, being pushed forward, as it were, and excited to action by that vis vivida, which is continually stirring within them, the first effort, the original impetus, proceeds not altogether from their own voluntary exertion, and because the pleasure which they, above all others, experience in the exercise of their faculties, is an ample compensation for the labour which that exercise requires. Accordingly, we find that the best writers of every age have generally, though not always, been the most voluminous. Not to mention a host of ancients, I might instance many of our own country as illustrious examples of this assertion, and no example more illustrious than that of the immortal Shakspeare. In our times the author of "Waverley," whose productions, in different branches of literature, would almost of themselves fill a library, continues to pour forth volume after volume from his inexhaustible stores. Mr. Southey, too, the poet, the historian, the biographer, and I know not what besides, is remarkable for his literary industry; and last, not least, the noble bard, the glory and the regret of every one who has a soul to feel those "thoughts that breathe and words that burn," the mighty poet himself, notwithstanding the shortness of his life, is distinguished by the number, as well as by the beauty and sublimity of his works. Besides these and other male writers, the best of our female authors, the boast and delight of the present age, and who have been compared to "so many modern Muses"—Miss Landon, Mrs. Hemans, Miss Edgeworth, Miss Mitford, &c.—have they not already supplied us largely with the means of entertainment and instruction, and have we not reason to expect still greater supplies from the same sources?

But although it may be easily allowed that men of very great natural genius are for the most part exempt from a love of idleness, it ought also to be acknowledged that there are others to whom, indeed, nature has not been equally bountiful, but who possess a certain degree of talent which perseverance and study (if to study they would apply themselves) might gradually advance, and at last carry to excellence.

[pg 437] With the exception of a few master spirits of every age and nation, genius is more equally distributed among mankind than many suppose. Hear what Quintilian says on the subject; his observations are these:—"It is a groundless complaint, that very few are endowed with quick apprehension, and that most persons lose the fruits of all their application and study through a natural slowness of understanding. The case is the very reverse, because we find mankind in general to be quick in apprehension, and susceptible of instruction, this being the characteristic of the human race; and as birds have from nature a propensity to fly, horses to run, and wild beasts to be savage, so is activity and vigour of mind peculiar to man; and hence his mind is supposed to be of divine original. But men are no more born with minds naturally dull and indocile, than with bodies of monstrous shapes, and these are very rare."

From what has been premised, this conclusion may be drawn—that it is not "conscious inability" alone, but often a love of leisure, which prevents us from undertaking any work. Many, to whom nature had given a certain degree of genius, have lived without sufficiently exercising that genius, and have, therefore, bequeathed no fruits of it to posterity at their death.

A CORRESPONDENT.

(For the Mirror.)

It was here the Danish army lay a considerable time encamped in 1011; and here that Wat Tyler, the Kentish rebel, mustered 100,000 men. Jack Cade, also, who styled himself John Mortimer, and laid claim to the crown, pretending that he was kinsman to the Duke of York, encamped on this heath for a month together, with a large body of rebels, which he had gathered in this and the neighbouring counties, in 1451; and the following year Henry VI. pitched his royal pavilion here, having assembled troops to withstand the force of his cousin, Edward, Duke of York, afterwards Edward IV.; and here, against that king, the bastard Falconbridge encamped. In 1497, the Lord Audley; Flemmock, an attorney; and Joseph, the blacksmith, encamped on this place in the rebellion they raised against Henry VII.; and here they were routed, with a loss of upwards of 2,000 on the spot, and 14,000 prisoners.

In 1415, the lord mayor and aldermen of London, with 400 citizens in scarlet, and with white and red hoods, came to Blackheath, where they met the victorious Henry V. on his return from France, after the famous battle of Agincourt: from Blackheath they conducted his majesty to London. In 1474, the lord mayor and aldermen, attended by 500 citizens, also met Edward IV. here, on his return from France. It appears also to have been usual formerly to meet foreign princes, and other persons of high rank, on Blackheath, on their arrival in England. On the 2lst of December, 1411, Maurice, Emperor of Constantinople, who came to solicit assistance against the Turks, was met here with great magnificence by Henry IV.; and in 1416 the Emperor Sigismund was met here, and from thence conducted in great pomp to London. In 1518, the lord admiral of France and the archbishop of Paris, both ambassadors from the French king, with above 1,200 attendants, were met here by the admiral of England and above 500 gentlemen; and the following year Cardinal Campejus, the pope's legate, being attended hither by the gentlemen of Kent, was met by the Duke of Norfolk, and many noblemen and prelates of England; and in a tent of cloth of gold he put on his cardinal's robes, richly ermined, and from hence rode to London, Here also Henry VIII. met the Princess Anne of Cleves in great state and pomp.

HALBERT H.

A retired barrister, living happily with his wife and children on a very moderate patrimony, has suddenly the misery to have a large fortune left him.—Time pressed. I set off at day break for London; plunged into the tiresome details of legateeship; and after a fortnight's toil, infinite weariness, and longings to breathe in any atmosphere unchoked by a million of chimneys, to sleep where no eternal rolling of equipages should disturb my rest, and to enjoy society without being trampled on by dowagers fifty deep, I saw my cottage roof once more.

But where was the cheerfulness that once made it more than a palace to me? The remittances that I had made from London were already conspiring against my quiet. I could scarcely get a kiss from either of my girls, they were in such merciless haste to make their dinner "toilet." My kind and comely wife was actually not to be seen; and her apology, delivered by a coxcomb in silver lace to the full as deep as any in (my rival) [pg 438] the sugar-baker's service, was, that "his lady would have the honour of waiting on me as soon as she was dressed." This was of course the puppy's own version of the message; but its meaning was clear, and it was ominous.

Dinner came at last: the table was loaded with awkward profusion; but it was as close an imitation as we could yet contrive of our opulent neighbour's display. No less than four footmen, discharged as splendid superfluities from the household of a duke, waited behind our four chairs, to make their remarks on our style of eating in contrast with the polished performances at their late master's. But Mrs. Molasses had exactly four. The argument was unanswerable. Silence and sullenness reigned through the banquet; but on the retreat of the four gentlemen who did us the honour of attending, the whole tale of evil burst forth. What is the popularity of man? The whole family had already dropped from the highest favouritism into the most angry disrepute. A kind of little rebellion raged against us in the village: we were hated, scorned, and libelled on all sides. My unlucky remittances had done the deed.

The village milliner, a cankered old carle, who had made caps and bonnets for the vicinage during the last forty years, led the battle. The wife and daughters of a man of East Indian wealth were not to be clothed like meaner souls; and the sight of three London bonnets in my pew had set the old sempstress in a blaze. The flame was easily propagated. The builder of my chaise-cart was irritated at the handsome barouche in which my family now moved above the heads of mankind. The rumour that champagne had appeared at the cottage roused the indignation of the honest vintner who had so long supplied me with port: and professional insinuations of the modified nature of this London luxury were employed to set the sneerers of the village against me and mine. Our four footmen had been instantly discovered by the eye of an opulent neighbour; and the competition was at once laughed at as folly, and resented as an insult. Every hour saw some of my old friends falling away from me. An unlucky cold, which seized one of my daughters a week before my return, had cut away my twenty years' acquaintance, the village-doctor, from my cause; for the illness of an "heiress" was not to be cured by less than the first medical authority of the province. The supreme Aesculapius was accordingly called in; and his humbler brother swore, in the bitterness of his soul, that he would never forget the affront on this side of death's door. The inevitable increase of dignity which communicated itself to the manners of my whole household did the rest; and if my wife held her head high, never was pride more peevishly retorted. Like the performers in a pillory, we seemed to have been elevated only for the benefit of a general pelting.

These were the women's share of the mischief; but I was not long without administering in person to our unpopularity. The report of my fortune had, as usual, been enormously exaggerated; and every man who had a debt to pay, or a purchase to make, conceived himself "bound to apply first to his old and excellent friend, to whom the accommodation for a month or two must be such a trifle." If I had listened to a tenth of those compliments, "their old and excellent friend" would have only preceded them to a jail. In some instances I complied, and so far only showed my folly; for who loves his creditor? My refusal of course increased the host of my enemies; and I was pronounced purse-proud, beggarly, and unworthy of the notice of the "true gentlemen, who knew how to spend their money."

Yet, though I was to be thus abandoned by my fox-hunting friends, I was by no means to feel myself the inhabitant of a solitary world. If the sudden discovery of kindred could cheer me under my calamities, no man might have passed a gayer life. For a long succession of years I had not seen a single relative. Not that they altogether disdained even the humble hospitalities of my cottage, or the humble help of my purse; on the contrary, they liked both exceedingly, and would have exhibited their affection in enjoying them as often as I pleased.

But I had early adopted a resolution, which I recommend to all men. I made use of no disguise on the subject of our mutual tendencies. I knew them to be selfish, beggarly in the midst of wealth, and artificial in the fulness of protestation. I disdained to play the farce of civility with them. I neither kissed nor quarrelled with them; but I quietly shut my door, and at last allowed no foot of their generation inside it. They hated me mortally in consequence, and I knew it. I despised them, and I conclude they knew that too. But I was resolved that they should not despise me; and I secured that point by not suffering them to feel that they had made me their dupe. The nabob's will had not soothed their tempers; and I was honoured with their most smiling animosity.

But now, as if they were hidden in the [pg 439] ground like weeds only waiting for the shower, a new and boundless crop of relationship sprang up. Within the first fortnight after my return, I was overwhelmed with congratulations from east, west, north, and south; and every postscript pointed with a request for my interest with boards and public offices of all kinds; with India presidents, treasury secretaries, and colonial patrons, for the provision of sons, nephews, and cousins, to the third and fourth generation.

My positive declarations that I had no influence with ministers were received with resolute scepticism. I was charged with old obligations conferred on my grandfathers and grandmothers; and, finally, had the certain knowledge that my gentlest denials were looked upon as a compound of selfishness and hypocrisy. Before a month was out, I had extended my sources of hostility to three-fourths of the kingdom, and contrived to plant in every corner some individual who looked on himself as bound to say the worst he could of his heartless, purse-proud, and abjured kinsman.

I should have sturdily borne up against all this while I could keep the warfare out of my own county. But what man can abide a daily skirmish round his house? I began to think of retreating while I was yet able to show my head; for, in truth, I was sick of this perpetual belligerency. I loved to see happy human faces. I loved the meeting of those old and humble friends to whose faces, rugged as they were, I was accustomed. I liked to stop and hear the odd news of the village, and the still odder versions of London news that transpired through the lips of our established politicians. I liked an occasional visit to our little club, where the exciseman, of fifty years standing was our oracle in politics; the attorney, of about the same duration, gave us opinions on the drama, philosophy, and poetry, all equally unindebted to Aristotle; and my mild and excellent father-in-law, the curate, shook his silver locks in gentle laughter at the discussion. I loved a supper in my snug parlour with the choice half dozen; a song from my girls, and a bottle after they were gone to dream of bow-knots and bargains for the next day.

But my delights were now all crushed. Another Midas, all I touched had turned to gold; and I believe in my soul that, with his gold, I got credit for his asses' ears.

However, I had long felt that contempt for popular opinion which every man feels who knows of what miserable materials it is made—how much of it is mere absurdity—how much malice—how much more the frothy foolery and maudlin gossip of the empty of this empty generation. "What was it to me if the grown children of our idle community, the male babblers, and the female cutters-up of character, voted me, in their commonplace souls, the blackest of black sheep? I was still strong in the solid respect of a few worth them all."

Let no man smile when I say that, on reckoning up this Theban band of sound judgment and inestimable fidelity, I found my muster reduced to three, and those three of so unromantic a class as the grey-headed exciseman, the equally grey-headed solicitor, and the curate.

But let it be remembered that a man must take his friends as fortune wills; that he who can even imagine that he has three is under rare circumstances; and that, as to the romance, time, which mellows and mollifies so many things, may so far extract the professional virus out of excisemen and solicitor, as to leave them both not incapable of entering into the ranks of humanity.

Showing the proportion per cent, of alcohol contained in different fermented liquors.

per cent.

Port wine 25.83

Ordinary port 23.71

Madeira 24.42

Sherry 19.81

Lisbon 18.94

Bucellas 18.49

Cape Madeira 22.94

Vidonia 19.25

Hermitage 17.43

Claret 17.11

Burgundy 16.60

Sauterne 14.22

Hock 14.37

Champagne 13.80

Champagne (sparkling) 12.80

Vin de Grave 13.94

Cider from 5.50 to 9.87

Perry (average) 7.26

Burton ale 8.88

Edinburgh 6.20

Dorchester 5.56

Brown stout 6.80

London porter (average) 4.20

Brandy 53.39

Rum 53.68

Gin 51.60

The figures set down opposite each liquor, exhibit the quantity of alcohol [pg 440] per cent. by measure in each at the temperature of 60°. Port, Sherry and Madeira, contain a large quantity of alcohol; that Claret, Burgundy, and Sauterne, contain less; and that Brandy contains as much as 53 per cent. of alcohol. In a general way, we may say, that the strong wines in common use, contain as much as a fourth per cent. of alcohol.

During Captain Franklin's recent voyage, the winter was so severe, near the Coppermine River, that the fish froze as they were taken out of the nets; in a short time they became a solid mass of ice, and were easily split open by a blow from a hatchet. If, in the completely frozen state, they were thawed before the fire, they revived. This is a very remarkable instance of how completely animation can be suspended in cold-blooded animals.

J.G.L.

The following method of rendering cast-iron soft and malleable may be new to some of your readers:—It consists in placing it in a pot surrounded by a soft red ore, found in Cumberland and other parts of England, which pot is placed in a common oven, the doors of which being closed, and but a slight draught of air permitted under the grate; a regular heat is kept up for one or two weeks, according to the thickness and weight of the castings. The pots are then withdrawn, and suffered to cool; and by this operation the hardest cast metal is rendered so soft and malleable, that it may be welded together, or, when in a cool state, bent into almost any shape by a hammer or vice.

W.G.C.

A countryman was seized with the most excruciating pain in his stomach, and which continued for so long a period, that his case became desperate, and his life was even despaired of. In this predicament, the medical gentleman to whom he applied administered to him a most violent emetic, and the result was the ejection of the larva, and which remained alive for a quarter of an hour after its expulsion. Upon questioning the man as to how it was likely that the insect got into his stomach, he stated that he was exceedingly fond of watercresses, and often gathered and eat them, and, possibly, without taking due care, in freeing them from any aquatic insects they might hold. He was also in the frequent habit of lying down and drinking the water of any clear rivulet when he was thirsty; and thus, in any of these ways, the insect, in its smaller state, might have been swallowed, and remained gradually increasing in size until it was ready for the change into the beetle state; at times, probably, preying upon the inner coat of the stomach, and thus producing the severe pains complained of by the sufferer.

We are surprised we do not hear more of the effects of swallowing the eggs or larva of insects, along with raw salads of different kinds. We would strongly recommend all families who can afford it, to keep in their sculleries a cistern of salt water, or, if they will take the trouble of renewing it frequently, of lime and water; and to have all vegetables to be used raw, first plunged in this cistern for a minute, and then washed in pure fresh water.—Gardener's Magazine.

Mr. Johnson, of Great Totham, is of opinion that smearing trees with oil, to destroy insects on them, injures the vegetation, and is not a certain remedy. He recommends scrubbing the trunks and branches of the trees every second year, with a hard brush dipped in strong brine of common salt. This effectually destroys insects of all kinds, and moss; and the stimulating influence of the application and friction is very beneficial.

The manna of the larch is thus procured:—About the month of June, when the sap of the tree is most luxuriant, it produces small white drops, of a sweet glutinous matter, like Calabrian manna, which are collected by the peasants early in the morning before the sun dissipates them.—Med. Bot.

It is very easy to kill plants by means of electricity. A very small shock, according to Cavallo, sent through the stem of a balsam, is sufficient to destroy it. A few minutes after the passage of the shock, the plant droops, the leaves and branches become flaccid, and its life ceases. A small Leyden phial, containing six or eight square inches of coated surface, is generally sufficient for this purpose, which may even be effected by means of strong sparks from the prime conductor of a large electrical machine. The charge by which these destructive effects are produced, is probably too inconsiderable to burst the vessels of the plant, or to occasion any material derangement of its organization; and, accordingly, it is not found, on minute examination of a plant thus killed by electricity, that either the internal vessels or any other parts have sustained perceptible injury.

Two correspondents have favoured us with the following illustrations of this curious custom: one of them (W.H.H.) has appended to his communication a pen and ink sketch, from which the above engraving is copied:—

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)

In Westmoreland this custom is thus commenced:—When it is known that a man has "fallen out" with his wife, or beaten or ill-used her, the townspeople procure a long pole, and instantly repair to his house; and after creating as much riot and confusion before the house as possible, one of them is hoisted upon this pole, borne by the multitude. He then makes a long speech opposite the said house, condemning, in strong terms, the offender's conduct—the crowd also showing their disapprobation. After this he is borne to the market-place, where he again proclaims his displeasure as before; and removes to different parts of the town, until he thinks all the town are informed of the man's behaviour; and after endeavouring to extort a fine from the party, which he sometimes does, all repair to a public-house, to regale themselves at his expense. Unless the delinquent can ill afford it, they take his "goods and chattels," if he will not surrender his money. The origin of this usage I am ignorant of, and shall be greatly obliged by any kind correspondent of the MIRROR who will explain it.

W.H.H.

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)

At Biggar, in Lanarkshire, as well as in several other places in Scotland, a very singular ancient practice is at times, though but rarely, revived. It is called riding the stang. When any husband is known to treat his wife extremely ill by beating her, and when the offence is long and unreasonably continued, while the wife's character is unexceptionable, the indignation of the neighbourhood, becoming gradually vehement, at last breaks out into action in the following manner:—All the women enter into conspiracy to execute vengeance upon the culprit. Having fixed upon the time when their design is to be put into effect, they suddenly assemble in a great crowd, and seize the offending party. They take care, at the same time, to provide a stout beam of wood, upon which they set him astride, and, hoisting him aloft, tie his legs beneath. He is thus carried in derision round the village, attended by the hootings, scoffs, and hisses of his numerous attendants, who pull down his legs, so as to render his seat in other respects abundantly uneasy. The grown-up men, in the meanwhile, remain at a distance, and avoid interfering in the ceremony. And it is well if the culprit, at the conclusion of the business, has not a ducking added to the rest of the punishment. Of the origin of this custom we know nothing. It is well known, however, over the country; [pg 442] and within these six years, it was with great ceremony performed upon a weaver in the Canongate of Edinburgh.

This custom can scarcely fail to recall to the recollection of the intelligent reader, the analogous practice among the Negroes of Africa, mentioned by Mungo Park, under the denomination of the mysteries of Mumbo Jumbo. The two customs, however, mark, in a striking manner, the different situations of the female sex in the northern and middle regions of the globe. From Tacitus and the earliest historians we learn, that the most ancient inhabitants of Europe, however barbarous their condition in other respects might be, lived on terms of equal society with their women, and avoided the practice of polygamy; but in Africa, where the laws of domestic society are different, the husbands, as the masters of a number of enslaved women, find it necessary to have recourse to frauds and disgraceful severities to maintain their authority; whereas in Europe we find, among the common people, a sanction for the women to protect each other, by severities, against the casual injustice committed by the ruling sex.

CHARLES STUART.

We have spiced our former volumes, as well as our present number, with two or three articles suitable to this jocund season; but we cannot deny ourselves the pleasure of adding "more last words." People talk of Old and New Christmas with woeful faces; and a few, more learned than their friends, cry stat nominis umbra,—all which may be very true, for aught we know or care. Swift proved that mortal MAN is a broomstick; and Dr. Johnson wrote a sublime meditation on a pudding; and we could write a whole number about the midnight mass and festivities of Christmas, pull out old Herrick and his Ceremonies for Christmasse—his yule log—and Strutt's Auntient Customs in Games used by Boys and Girls, merrily sett out in verse; but we leave such relics for the present, and seek consolation in the thousand wagon-loads of poultry and game, and the many million turkeys that make all the coach—offices of the metropolis like so many charnel-houses. We would rather illustrate our joy like the Hindoos do their geography, with rivers and seas of liquid amber, clarified butter, milk, curds, and intoxicating liquors. No arch in antiquity, not even that of Constantine, delights us like the arch of a baron of beef, with its soft-flowing sea of gravy, whose silence is only broken by the silver oar announcing that another guest is made happy. Then the pudding, with all its Johnsonian associations of "the golden grain drinking the dews of the morning—milk pressed by the gentle hand of the beauteous milk-maid—egg, that miracle of nature, which Burnett has compared to creation—and salt, the image of intellectual excellence, which contributes to the foundation of a pudding." As long as the times spare us these luxuries, we leave Hortensius to his peacocks; Heliogabalus to his dishes of cocks-combs; and Domitian to his deliberations in what vase he may boil his huge turbot. We have epicures as well as had our ancestors; and the wonted fires of Apicius and Sardanapalus may still live in St. James's-street and Waterloo-place; but commend us to the board, where each guest, like a true feeler, brings half the entertainment along with him. This brings us to notice Christmas, a Poem, by Edward Moxon, full of ingenuousness and good feeling, in Crabbe-like measure; but, captious reader, suspect not a pun on the poet of England's hearth—for a more unfortunate name than Crabbe we do not recollect.

Mr. Moxon's is a modest little octavo, of 76 pages, which may be read between the first and last arrival of a Christmas party. As a specimen, we subjoin the following:—

Hail, Christmas! holy, joyous time,

The boast of many an age gone by,

And yet methinks unsung in rhyme,

Though dear to bards of chivalry;

Nor less of old to Church and State,

As authors erudite relate.

If so, my harp, thou friend to me,

Thy chords I'll touch right merrily—

Then a fire-side picture of Christmas in the country:—

The doughty host has gather'd round

Those most for wit and mirth renown'd,

And soon each neighbouring Squire will be

With all the world in charity—

Its cares and troubles all forgetting,

Good-humour'd joke alone abetting.

'Tis good and cheering to the soul

To see the ancient wassail bowl

No longer lying on its face,

Or dusty in its hiding place.

It brings to mind a day gone by,

Our fathers and their chivalry—

It speaks of courtly Knight and Squire,

Of Lady's love, and Dame, and Friar,

Of times, (perchance not better now,)

When care had less of wrinkled brow—

When she with hydra-troubled mien,

Our greatest enemy, the Spleen,

Was seldom, or was never seen.

Now pledge they round each other's name,

And drink to Squire and drink to Dame,

While here, more precious far than gold,

Sits womanhood, with modest eye—

Glances to her the truth unfold,

She shall not pass unheeded by.

T'was woman that with health did greet,

When Vortigern did Hengist meet—

'Twas fair Rowena, Saxon maid,

In blue-ey'd majesty array'd,

Presented 'neath their witching roll

To British Chief the wassail bowl.

She touch'd to him, nor then in vain,

He back return'd the health again.

Thus 'tis with feelings kind as true

They drink the tribute ever due,

Nor would they less, tho' truth denied it,

Their love for woman would decide it.

Right merry now the hours they pass,

Fleeting thru jocund pleasure's glass,

The yule-clog too burns bright and clear,

Auspicious of a happy year:

While some with joke, and some with tale

But all with sweeter mulled ale,

Pass gaily time's swift stream along,

With interlude of ancient song—

And as each rosy cup they drain,

Bounty replenishes again.

An happy time! hours like to these,

Tho' fleeting, never fail to please.

Who reigns, who riots, or who sings,

Or who enjoys the smiles of kings.

What preacher follows half the town;

Who pleads, with or without a gown;

Who rules his wife, or who the state;

Who little, or who truly great;

What matters light the world amuse,

Where half the other half abuse;

Whether it shall be peace or war,

Or we remain just as we are—

Is all as one to those we see

Around the cup of jollity.

Old age, with joke will still crack on,

And story will be dwelt upon—

Till Christmas shows his ruddy nose,

They will not seek for night's repose,

Nor this their jovial meeting close.

In utter prostration, and sacred privacy of soul, I almost think now, and have often felt heretofore, man may make a confessional of the breast of his brother man. Once I had such a friend—and to me he was a priest. He has been so long dead, that it seems to me now, that I have almost forgotten him—and that I remember only that he once lived, and that I once loved him with all my affections. One such friend alone can ever, from the very nature of things, belong to any one human being, however endowed by nature and beloved of heaven. He is felt to stand between us and our upbraiding conscience. In his life lies the strength—the power—the virtue of ours—in his death the better half of our whole being seems to expire. Such communion of spirit, perhaps, can only be in existences rising towards their meridian; as the hills of life cast longer shadows in the westering hours, we grow—I should not say more suspicious, for that may be too strong a word—but more silent, more self-wrapt, more circumspect—less sympathetic even with kindred and congenial natures, who will sometimes, in our almost sullen moods or theirs, seem as if they were kindred and congenial no more—less devoted to Spirituals, that is, to Ideas, so tender, true, beautiful, and sublime, that they seem to be inhabitants of heaven though born of earth, and to float between the two regions, angelical and divine—yet felt to be mortal, human still—the Ideas of passions, and desires, and affections, and "impulses that come to us in solitude," to whom we breathe out our souls in silence, or in almost silent speech, in utterly mute adoration, or in broken hymns of feeling, believing that the holy enthusiasm will go with us through life to the grave, or rather knowing not, or feeling not, that the grave is any thing more for us than a mere word with a somewhat mournful sound, and that life is changeless, cloudless, unfading as the heaven of heavens, that lies to the uplifted fancy in blue immortal calm, round the throne of the eternal Jehovah.—Noctes—Blackwood's Magazine.

The English school of landscape painting has come to be of the first rank, and the contemporaries of Turner, Constable, Calcott, Thomson, Williams, Copley Fielding, and others whom we might name even with these masters, have no reason to reproach themselves with any neglect of their merits. The truth with which these artists have delineated the features of British landscape is, according to general admission, unmatched by even the most splendid exertions of foreign schools in the same department.—Quarterly Rev..

Mr. Leigh, who is well known as the publisher of the best English guides all over the continent, has just added to their number a Panorama of the Rhine and the adjacent country, from Cologne to Mayence, with maps of the routes from London to Cologne, and from thence to the sources of the Rhine. The Panorama is designed from nature by F.W. Delkeskamp, and engraved by John Clark. It consists of a beautiful aqua-tint engraving, upwards of seven feet in length, and six inches in width, representing the course of the Rhine, and its picturesque banks, studded with towns and villages; whilst steam-boats, bridges, and islets are distinctly shown in the river. It would be difficult to convey to our readers an idea of the extreme delicacy with which the plate is engraved; and, to speak dramatically, the entire success of the representation. A more interesting or useful companion for the tourist could scarcely be conceived; for the picture is not interrupted by the names of the places, but these are judiciously introduced in the margins of the plate. In short, every [pg 444] town, village, fortress, convent, mansion, mountain, dale, field, and forest, are here represented. By way of Supplement to the Plate, a Steam-boat Companion is appended, describing the principal places on the Rhine, with the population, curiosities, inns, &c. We passed an hour over the engraving very agreeably, coasting along till we actually fancied ourselves in one of the apartments of the Hotel of Darmstadt at Mayence, when missing our high conic bumper of Rudesheim—we found our thanks were due to the artist for the luxury of the illusion. The Panorama folds up in a neat portfolio, and occupies little more room than a quire of letter paper.

A' The lumms smokeless! No ae jack turnin' a piece o' roastin' beef afore ae fire in ony ae kitchen in a' the New Toon! Streets and squares a' grass-grown, sae that they micht be mawn! Shops like bee-hives that hae de'd in wunter! Coaches settin' aff for Stirlin', and Perth, and Glasgow, and no ae passenger either inside or out—only the driver keepin' up his heart wi' flourishin' his whup, and the guard, sittin' in perfect solitude, playin' an eerie spring on his bugle-horn! The shut-up play-house a' covered ower wi' bills that seem to speak o' plays acted in an antediluvian world! Here, perhaps, a leevin' creter, like ane emage, staunin' at the mouth o' a close, or hirplin' alang, like the last relic o' the plague. And oh! but the stane-statue o' the late Lord Melville, staunin' a' by himsell up in the silent air, a hunder-and-fifty feet high, has then a ghastly seeming in the sky, like some giant condemned to perpetual imprisonment on his pedestal, and mournin' ower the desolation of the city that in life he loved so well.—Noctes—Blackwood's Magazine.

A Correspondent has sent us a copy of some "Stanzas written in Commemoration of the Battle of Navarin," written by A. Grassie, piper on board H.M.S. Glasgow, R.N.—or "by a sailor in the engagement." One of the twelve stanzas is as follows:—

To save the sacrifice of life,

Was valiant Codrington's design;

And for those Turks it had been good.

If to his terms they would incline:

They fired upon the Dartmouth's boat,

And killed some of its gallant men;

But that distinguished frigate had

Complete revenge at Navarin.

This specimen of nautical numbers reminds us of Addison's suggestion for setting the Chelsea and Greenwich pensioners to write accounts of the battles in which they had served; and we hope others will follow Mr. Grassie's example in these piping times of peace.

A point of some importance in the internal decoration of palatial houses, viz. the introduction of "ornaments of the age of Louis XIV." is now canvassing among connoisseurs, or rather among those who direct the public taste. Some of our readers are probably aware that the mansion built for the late Duke of York, and Crockford's Club-house, are embellished in this style, which, to say the best, is gorgeous and expensive, without displaying good taste. We ought to leave such matters to the classical Mr. T. Hope, who has written a folio volume on "Household Furniture and Internal Decorations;" or the Carvers, Gilders, and Cabinet-Makers' Societies might sit in council on the subject. The question is interesting to all lovers of the fine arts, and to men of taste generally.

Is there any thing in this?

"It were no preposterous conceit to affirm, that nature typifies in each individual man the several offices and orders which our commonwealth distributes to the several ranks and functionaries of the state. There are the Operative Energies, Talents, Passions, Appetites, good servants all, but bad masters, useful citizens, always to be controlled, but never oppressed, and most effective when they are neither pampered nor starved. There, too, is the Executive Will; Prudence, Chancellor of the Exchequer; Self-love, minister for the Home Department; Observation, Secretary of Foreign Affairs; Poetry, over the Woods and Forests; Lord Keeper Conscience, a sage, scrupulous, hesitating, head-shaking, hair-splitting personage, whose decisions are most just, but too slow to be useful, and who is the readier to weep for what is done, than to direct what should be done; Wit, Manager of the House of Commons, a flashy, either-sided gentleman, who piques himself on never being out; and Self-Denial, always eager to vacate his seat and accept the Chiltern Hundreds."—Blackwood's Mag.

Man is so pugnacious an animal, that even the quakers, who in all other things seem effectually to have subdued this part of their animal nature, carry on controversy, whenever they engage in it, tooth and nail.—Quarterly Rev.

Vitellius, an Emperour of Rome, was among divers other his notorious vices so luxuriously given, that at one supper he was served with two thousand fishes of divers kindes, and seven thousand flying foules; he was afterward drawne through the streets with a halter about his neck, and shamefully put to death.

But what shall we wonder at emperours prodigalities, when of later yeares a simple Franciscan frier, Peter de Ruere, after hee had attained to the dignitie of cardinall by the favour of the pope, his kinsman, hee spent in two yeares, in which he lived at Rome, in feasts and banquets, two hundred thousand crownes, besides his debts, which were as much more.

In our time Muleasses, King of Tunis, was so drowned in pleasures, that being expelled from his kingdome for his vices, after his returne from Germanie, being denyed of ayd hee sought of the Emperour Charles the Fifth, he spent an hundred crownes upon the dressing of a peacocke for his owne mouth. And that hee might with more pleasure heare musicke, he used to cover his eyes.—But the judgment of God fell upon him; for his sone or brother dispossessed him of his kingdome, and provided him a remedie that his sight should be no longer annoyance to his hearing, causing his eyes to be put out with a burning hot iron. He that is given to please his senses, and delighteth in the excesse of eating and drinking, may, as Sallust saith, bee called animal, for hee is unworthy the name of a man. For wherin can a man more resemble brute beasts, and degenerate from his angelicall nature, than to serve his belly and his senses? But if our predecessors exceeded us in superfluitie of meats, wee can compare and goe beyond them in drinking and quaffing.

King Edgar so much detested this vice of drunkennesse, that hee set an order that no man should drinke beyond a certaine ring, made round about the glasses and cups, of purpose for a marke.

Anacharsis saith, that the first draught is to quench the thirst, the second for nourishment, the third for pleasure, the fourth for madnesse.

Augustine Lercheimer reporteth a strange historie of three quaffers in Germany, in the yeare one thousand five hundred and fortie nine; these three companions were in such a jollity after they had taken in their cups, according to the brutish manner of that countrey, that with a coale they painted the divell on the wall, and dranke freely to him, and talked to him as though hee had been present. The next morning they were found strangled, and dead, and were buried under the gallowes.

Surfeits maketh worke many times for the physician, who turning R into D giveth his patient sometime a Decipe for a Recipe; and so payeth deerely for his travell that hastneth him to his end. Horace calleth such men that give themselves to their belly, a beast of Arcadia that devoureth the grasse of the earth.

Cornelius Celsus giveth this counsell when men come to meat: Nunquam utilis nimia satietatis, saepe inutilis nimia abstinentia; over-much satiety is never good, over-much abstinence is often hurtfull.

Mahomet desirous to draw men to the liking of him and his doctrine, and perceiving the pronenesse of men to luxuriousness and fleshly pleasures, yet dealt more craftily in his Alcoran, than to persuade them that felicitie consisted in the voluptuousenesse and pleasures of this life, which he knew would not be believed nor followed but of a few, and those the more brutish sort, but threatened them with a kind of hell, and gave them precepts tending somewhat more to civilitie and humanitie, and promised his followers a paradise in the life to come, wherin they should enjoy all maner of pleasures which men desire in this world; as faire gardens environed with pleasant rivers, sweet flowers, all kinde of odoriferous savours, most delicate fruits, tables furnished with most daintie meats, and pleasant wines served in vessels of gold, &c. &c.

The Egyptians had a custome not unmeet to bee used at the carousing banquets; their manner was, in the middest of their feasts to have brought before them anatomie of a dead body dried, that the sight and horror thereof putting them in minde to what passe themselves should one day come, might containe them in modesty. But peradventure things are fallen so far from their right course, that that device will not so well serve the turne, as if the carousers of these later daies were persuaded, as Mahomet persuaded his followers when hee forbad them the drinking of wine, that in every grape there dwelt a divell. But whun they have taken in their cups, it seemeth that many of them doe feare neither the divell nor any thing else.

[pg 446] Lavater reporteth a historie of a parish priest in Germanie, that disguised himselfe with a white sheete about him, and at midnight came into the chamber of a rich woman that was in bed, and fashioning himself like a spirit, hee thought to put her in such feare, that shee would procure a conjuror or exorcist to talke with him, or else speake to him herselfe. The woman desired one of her kinsmen to stay with her in her chamber the next night. This man making no question whether it were a spirit or not, instead of conjuration or exorcisme, brought a good cudgell with him, and after hee had well drunke to encrease his courage, knowing his hardinesse at those times to bee such, that all the divels in hell could not make him affraide, hee lay downe upon a pallat, and fell asleepe. The spirit came into the chamber againe at his accustomed houre, and made such a rumbling noyse, that the exorcist (the wine not being yet gone out of his head) awaked, and leapt out of his bed, and toward the spirit hee goeth, who with counterfeit words and gesture, thought to make him afraid. But this drunken fellow making no account of his threatnings, Art thou the divel? quoth he, then I am his damme; and so layeth upon him with his cudgell, that if the poore priest had not changed his divel's voyce, and confessed himselfe to be Hauns, and rescued by the woman that then knew him, he had bin like not to have gone out of the place alive.

This vice of drunkennesse, wherein many take over-great pleasure, was a great blemish to Alexander's virtues. For having won a great part of Asia, he laid aside that sobrietie hee brought forth of Macedon, and gave himselfe to the luxuriousenesse of those people whom he had conquered.

That King, Cambyses, tooke over-great plaasure in drinking of wine; and when he asked Prexaspes, his secretary, what the Persians said of him, he answered, that they commended him highly, notwithstanding they thought him over-much given to wine, the king being therewith very angry, caused Prexaspes' sonne to stand before him, and taking his bow in his hand, Now (quoth he) if I strike thy son's heart, it will then appeare that I am not drunk, but that the Persians doe lye; but if I misse his heart, they may be believed. And when he had shot at his son, and found his arrow had pierced his heart, he was very glad; and told him that he had proved the Persians to be lyars.

Fliolmus, king of the Gothes, was so addicted to drinking, that hee would sit a great part of the night quaffing and carousing with his servants. And as on a time he sate after his accustomed and beastly manner carousing with them, his servants being as drunke as he, threw the king, in sport, into a great vessell full of drinke, that was set in the middist of the hall for their quaffing, where he ridiculously and miserably ended his life.

Cineas being ambassador to Pyrrhus, as he arrived in Egypt, and saw the exceeding height of the vines of that country, considering with himselfe how much evill that fruit brought forth to men, sayd, that such a mother deserved justly to be hanged so high, seeing she did beare so dangerous a child as wine was. Plato considering the hurt that wine did to men, sayd, that the gods sent wine downe hither, partly for a punishment of their sinnes, that when they are drunke, one might kill another.

Paulus Diacrius reporteth a monstrous kinde of quaffing, between foure old men at a banquet, which they made of purpose. Their challenge was, two to two, and he that dranke to his companion must drinke so many times as hee had yeares; the youngest of the foure was eight and fiftie yeares old; the second three-score and three; the third four-score and seven; the fourth four-score and twelve; so that he which dranke least, dranke eight-and-fifty bowles full of wine, and so consequently, according to their yeares, whereof one dranke four-score and twelve bowles.

The old Romanes, when they were disposed to quaff lustily, would drinke so many carouses as there were letters in the names of their mistresses, or lovers; so easily were they overcome with this vice, who by their virtue some other time, became masters of the world; but these devices are peradventure stale now; there be finer devices to provoke drunkennesse.

In the time of Antonius Pius, the people of Rome being given to drinke without measure, he commanded that none should presume to sell wine but in apothecaries' shops, for the sicke or diseased.

Cyrus, of a contrary disposition to the gluttons and carousers, in his youth gave notable signes and afterward like examples of sobrietie and frugalitie, when he was monarch of the Persians. For, being demanded when he was but a boy, of his grandfather, Astyages, why he would drink no wine, because, said hee, I observed yesterday when you celebrated the feast of your nativitie, so strange a thing, that it could not be but that som man had put poison into all the wine that ye drank; for at the taking up of the table, there was not one man in his right minde. By this it appeareth, how rare a matter it was then to drinke wine, and a thing to be wondered at to see men drunke. For when the use of wine was first found out, it was taken for a thing medicinable, and not used for a common drinke, and was to be found rather in apothecaries' shops than in tavernes. What a great difference there was betweene the frugalitie of the former ages and the luxuriousnesse of these latter dayes, these few examples will shew. This Cyrus, as hee marched with his army, one asking him what he would have provided for his supper, hee answered, bread; for I hope, sayth hee, wee shall find a fountain to serve us of drinke. When Plato had beene in Sicilia, being asked what new or strange thing hee had seene; I have seene, sayth hee, a monster of nature, that eateth twice a day. For Dionysius whom he meant, first brought the custome into that country. For it was the use among the Hebrewes, the Grecians, the Romanes, and other nations, to eat but once a day. But now many would thinke they should in a short time be halfe famished, if they should eat but twice a day; nay, rather whole dayes and nights bee scant sufficient for many to continue eating and quaffing. Wee may say with the poet—

Tempora mutantur et nos mutamur in illis.

The times are changed and we are changed in them.

By the historie of the swine (which by the permission of God, were vexed by the divell) we be secretly admonished that they which spend their lives in pleasures and deliciousnesse, such belly-gods as the world hath many in these daies, that live like swine, shall one day be made a prey for the divell; for seeing they will not be the temple of God, and the house of the Holy Ghost, they must of necessitie be the habitation of the divell. Such swine, sayth one, be they that make their paradise in this world, and that dissemble their vices, lest they should bee deprived of their worldly goods.

[The author of the following stanzas is JOHN BYROM, an ingenious poet, famous also as the inventor of a System of Stenography. He was born in 1691, and died in 1763. Byrom wrote poetry, or rather verse, with extraordinary facility. His pastoral, entitled "Colin and Phoebe," first published in the "Spectator," when the author was quite young, has been much admired. As literary curiosities, his poems are too interesting to be neglected; and their oddity well entitles them to the room they fill. The following poem is perfectly in the manner of Elizabeth's age; and we have selected it as a seasonable dish for the present number—trusting that its rich vein of humour may find a kindred flow in the hearts of our readers.]

I am content, I do not care,

Wag as it will the world for me;

When fuss and fret was all my fare,

I got no ground as I could see:

So when away my caring went,

I counted cost, and was content.

With more of thanks and less of thought,

I strive to make my matters meet;

To seek what ancient sages sought,

Physic and food in sour and sweet:

To take what passes in good part,

And keep the hiccups from the heart.

With good and gentle humour'd hearts,

I choose to chat where'er I come,

Whate'er the subject be that starts:

But if I get among the glum,

I hold my tongue to tell the truth,

And keep my breath to cool my broth.

For chance or change of peace or pain;

For Fortune's favour or her frown;

For lack or glut, for loss or gain,

I never dodge, nor up nor down:

But swing what way the ship shall swim,

Or tack about with equal trim.

I suit not where I shall not speed,

Nor trace the turn of ev'ry tide;

If simple sense will not succeed

I make no bustling, but abide:

For shining wealth, or scaring woe,

I force no friend, I fear no foe.

Of ups and downs, of ins and outs,

Of the're i'th' wrong, and we're i'th' right,

I shun the rancours and the routs,

And wishing well to every wight,

Whatever turn the matter takes,

I deem it all but ducks and drakes.

With whom I feast I do not fawn,

Nor if the folks should flout me, faint;

If wonted welcome he withdrawn,

I cook no kind of a complaint:

With none dispos'd to disagree,

But like them best who best like me.

Not that I rate myself the rule

How all my betters should behave;

But fame shall find me no man's fool,

Nor to a set of men a slave.

I love a friendship free and frank,

And hate to hang upon a hank.

Fond of a true and trusty tie,

I never loose where'er I link;

Tho' if a bus'ness budges by,

I talk thereon just as I think;

My word, my work, my heart, my hand,

Still on a side together stand.

If names or notions make a noise,

Whatever hap the question hath,

The point impartially I poise,

And read or write, but without wrath;

For should I burn, or break my brains,

Pray, who will pay me for my pains?

I love my neighbour as myself,

Myself like him too, by his leave—

Nor to his pleasure, pow'r, or pelf,

Came I to crouch, as I conceive:

Dame Nature doubtless has design'd

A man the monarch of his mind.

Now taste and try tills temper, sirs,

Mood it and brood it in your breast—

Or if ye ween, for worldly stirs.

That man does right to mar his rest,

Let me be deft and debonair,

I am content, I do not care.

"A snapper-up of unconsidered trifles."

SHAKSPEARE.

The following recipe for a French tragedy is not unworthy of Swift. "Take two good characters, and one wicked, either a tyrant, a traitor, or a rogue. Let the latter set the two former by the ears and make them very unhappy for four acts, during which he must promulgate all manner of shocking maxims, interlarded with poisons, daggers, oracles, &c.; while the good characters repeat their catechism of moralities. In the fifth act, let the power of the tyrant be overthrown by an insurrection, or the treason of the villain be discovered by some episodical personage, and the worthy folks be preserved. Above all, don't forget, if there is any difference subsisting between France and England, or between the parliament and the clergy, to allude to it, and you will have fabricated such a piece as shall be applauded three times a week for three weeks together at the Comédie Française."

Some time, far back, my Christmas fare

Was turkey and a chine,

With puddings made of things most rare,

And plenty of good wine.

When times grew worse, I then could dine

On goose or roasted pig;

Instead of wine, a glass of grog,

And dance the merry jig.

When still grown worse, I then could dine

On beef and pudding plain;

Instead of grog, some good strong beer—

Nor did I then complain.

But now my joy is turn'd to grief,

For Christmas day is here;

No turkey, chine, or goose, or beef,

No wine, no grog, no beer.

Dec. 25, 1828.

—When I'm late for school,

The excuse 'twill be my mother, Sir;

And when that one won't do,

I'll try and make another, Sir.

Fer my mother is a good man,

And so, Sir, is my daddy O—

And 'twill not be my fault

If I'm not their own Paddy O.

"His Honur Mr. Trant, Esquire, Dr. to James Barret, Shoemaker."

£. s. d.

To clicking and sowling Miss Clara 0 2 6

To strapping and welting Miss Biddy 0 1 0

To binding and closing Miss Mary 0 1 6

________

Paid, July 14, 1828. £0 5 0

JAMES BARRET.

Croker's Legends of the Lakes.

A celebrated literary character, in a northern metropolis, had a black servant, whom he occasionally employed in beating covers for woodcocks and other game. On one occasion of intense frost, the native of Afric's sultry shores was nearly frozen to death by the cold and wet of the bushes, which sparkled, (but not with fire-flies,) and on which, pathetically blowing his fingers, he was heard to exclaim, in reply to an observation of his master, that "the woodcocks were very, scarce," "Ah, massa, me wish woodcock never been!"

"Lady Racher is put to bed," said Sir Boyle Roche to a friend. "What has she got?"—"Guess."—"A boy?"—"No, guess again."—"A girl?"—"Who told you?"

The supplement to VOL. XII., containing Titles, Preface, Index, &c., with a fine Steel Plate PORTRAIT of T. MOORE, Esq. and an Original Memoir, is published with the present Number.

LIMBIRD'S EDITION OF THE

Following Novels are already Published:

s. d.

Mackenzie's Man of Feeling 0 6

Paul and Virginia 0 6

The Castle of Otranto 0 6

Almoran and Hamet 0 6

Elizabeth, or the Exiles of Siberia 0 6

The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne 0 6

Rasselas 0 8

The Old English Baron 0 8

Nature and Art 0 8

Goldsmith's Vicar of Wakefield 0 10

Sicilian Romance 1 0

The Man of the World 1 0

A Simple Story 1 4

Joseph Andrews 1 6

Humphry Clinker 1 8

The Romance of the Forest 1 8

The Italian 2 0

Zeluco, by Dr. Moore 2 6

Edward, by Dr. Moore 2 6

Roderick Random 2 6

The Mysteries of Udolpho 3 6

Footnote 1: (return)The following anecdote is related of him:—Charles II. more than once dined with his good citizens of London on their Lord Mayor's Day, and did so the year that Sir Robert Viner was mayor. Sir Robert was a very loyal man, and, very fond of his sovereign; but, what with the joy he felt at heart for the honour done him by his prince, and through the warmth he was in with continual toasting healths to the royal family, his lordship grew a little fond of his majesty, and entered into a familiarity not altogether so graceful in so public a place. The king understood very well how to extricate himself in all kinds of difficulties, and, with a hint to the company to avoid ceremony, stole off and made towards his coach, which stood ready for him in Guildhall yard. But the mayor liked his company so well, and was grown so intimate, that he pursued him hastily, and, catching him fast by the hand, cried out with a vehement oath and accent, "Sir, you shall stay and take t'other bottle." The airy monarch looked kindly at him over his shoulder, and with a smile and graceful air, repeated this line of the old song—

"He that's drunk is as great as a king,"

and immediately returned back, and complied with his landlord.—Spectator, 462.

Printed and Published by J. LIMBIRD, 143, Strand, London; sold by ERNEST FLEISCHER, 626, New Market, Leipsic; and by all Newsmen and Booksellers.