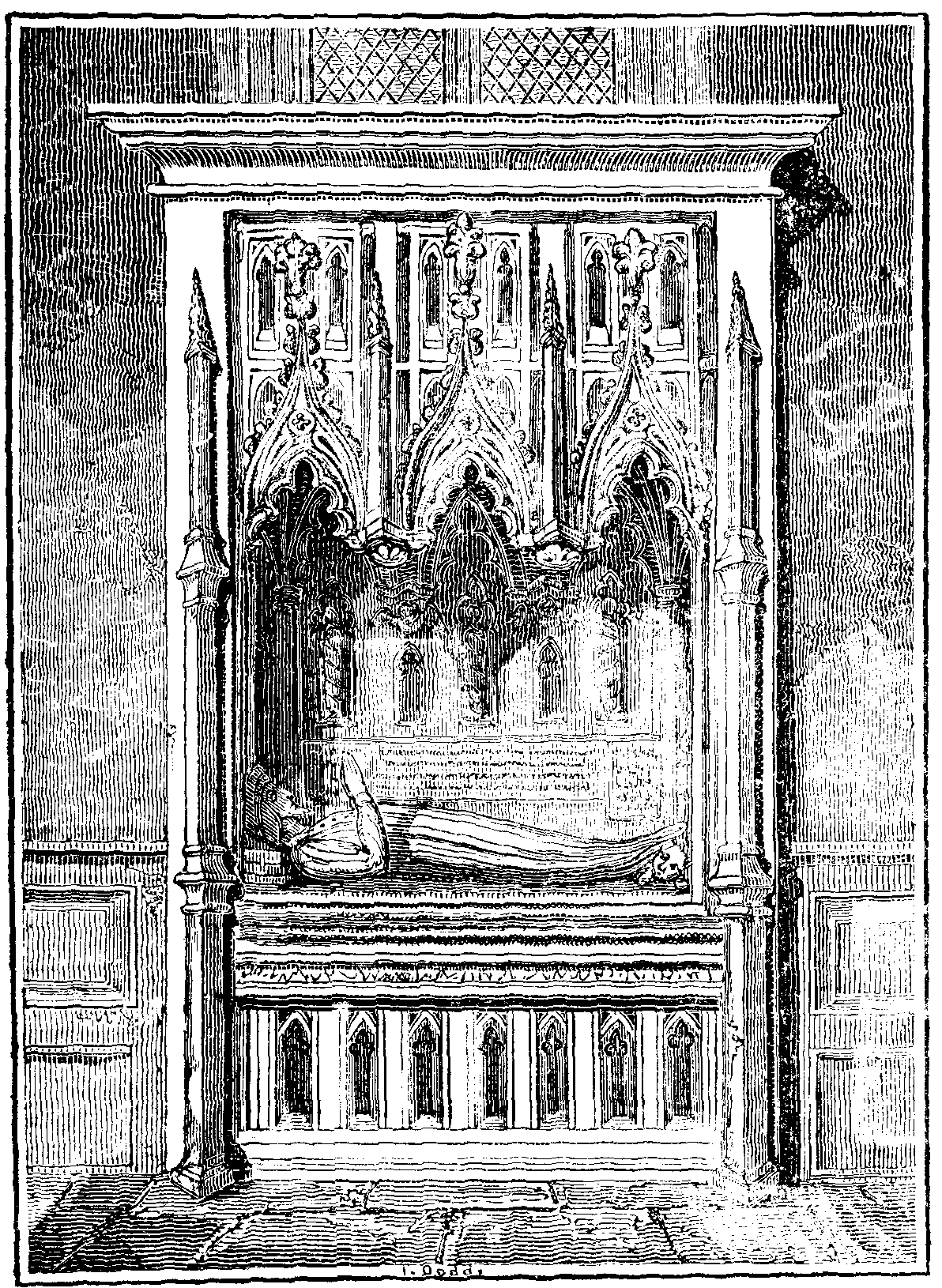

Tomb of Gower, the Poet.

Tomb of Gower, the Poet.Title: The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 364, April 4, 1829

Author: Various

Release date: March 1, 2004 [eBook #11740]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/11740

Credits: Produced by Jonathan Ingram and PG Distributed Proofreaders

| Vol. XIII. No. 364. | SATURDAY, APRIL 4, 1829 | PRICE 2d. |

Dr. Johnson has dignified Gower with the character of "THE FATHER OF ENGLISH POETRY"; so that no apology is required for the introduction of the above memorial in our pages. It stands in the north aisle of the church of St. Mary Ovrie, or St. Saviour, Southwark; and is one of the richest monuments within those hallowed walls. The tomb consists of three Gothic arches, the roof of which springs into several angles. The arches are richly ornamented with cinnquefoil tracery, roses, and carved work of exquisite character. Behind these arches are two rows of trefoil niches; and between them also rises a square column, of the Doric order, surmounted by carved pinnacles. On the extremity of the arches is placed richly carved foliage, of a similar character to that which ornaments the edges of the arches; and in the centre are circles enclosing quatrefoils. From the bases of the two middle square columns descend roses, and other foliage; and from the lower extremities of the interior arches descend cherubim. Within three painted niches, are the figures of Charity, Mercy, and Pity, round whom are entwined golden scrolls bearing the following inscriptions:

"Pour la Pitie Jesu regarde.

Et tiens cest Ami en saufve Garde."

Jesu! for thy compassion's sake look down,

And guard this soul as if it were thine own.

On the second scroll is written:

"Oh, bon Jesu! faite Mercy,

Al' Ame dont le Corps gist icy."

Oh! good Jesu! Mercy shew

To him whose body lies below.

On the third scroll is written:

"En toy qui es Fitz de Dieu le Pere,

Saufve soit qui gist sours cest Pierre."

May he who lies beneath this stone,

Be sav'd in thee, God's only son!1

Between each of these figures are painted blank trefoil niches; and below the whole, on a plain tablet, the following inscription:

"Armiger scutum nihil a modo fut tibi tutum,

Reddidit immolutum, morti generali tributum,

Spiritus exutum se gaudeat esse solutum,

Est ubi vistutum, Regnum sive labe statutum."

On the left side:

"Hoc viri

Inter inclytos memorandi

Monumentum sepulchrali,

Restaurari propriis impensis

Parocnia hujus meolæ

Curaverunt

A.D. MDCCXCVIII."

On the right side:

Capellaris {GULIELMO DAY

{ &

{GULIELMO WINCKWORK.

Custodibus {GULIELMO SWAINE

{ &

{DAVIDE DURIE.

Aotante humiblimo Pastore DAVIDE GILSON.

And below the effigy runs the following:—

"Hic jacet JOHANNIS GOWER,

Armiger, Anglorum Poeta celeberrimus,

ac huic sacro Edificio Benefactor, insignis

temporibus Edw. III. et Rich. II."

Here lieth John Gower, esq., a celebrated

English poet, also a benefactor to

this sacred edifice, in the time of Edward

III. and Richard II.

The base of the monument has seven trefoil niches, within as many plain-pointed ones.

The effigy of the poet is placed above, in a recumbent posture, beneath the canopy just described. He is dressed in a gown, originally purple, covering his feet, which rest on the neck of a lion. A coronet of roses adorns his head, which is raised by three folio volumes, labelled on their respective ends, "Vox Clamantis," "Speculum Meditantis," and "Confessio Amantis." Round the neck hangs a collar of SSS. Over the lion, on the side of the monument, are the arms of the deceased, hanging, by the dexter corner, from an ancient French chappeau, bearing his crest. The dress of this effigy has, probably, given rise to the conjectures concerning the rank in life which Gower maintained; but that is too precarious a ground on which to form a decided opinion on such a point.

Gower's arms are, Argent on a cheveron, azure, three leopard's heads, Or. Crest. On a chappeau turned up with ermine, a talbot, serjant, proper.

A little eastward of Gower's monument is part of a pillar, descending from the roof, with a conical base. It is said to be hollow, and has, indeed, somewhat the appearance of a narrow chimney flue.

A biographical outline of Gower may not be unacceptable. He is said by Leland to have descended from a family settled at Sittenham, in Yorkshire. He was liberally educated, and was a member of the Inner Temple; and some have asserted that he became Chief Justice of the Common Pleas; but the most general opinion is that the judge was another person of the same name. It is certain that Gower was a person of considerable weight in his time; even had he not given such ample proofs of his wealth and munificence in rebuilding the conventual church of St. Mary Ouvrie, If he did not actually rebuild the church, as has been asserted, it is well known that he contributed very largely to that undertaking. Perhaps the only fact in detail which it is now possible to ascertain with certainty is, that he founded a chantry in the chapel of St. John, now the vestry.

Gower is supposed to have been born before Chaucer, who flourished in the early part of the fourteenth century, and is believed to have contracted an acquaintance with Gower during his residence in the Middle Temple. Chaucer himself, after his travels on the continent, became a student of the Inner Temple. The contiguity of these inns of court, the similarity of their studies and pursuits, and particularly, as they both possessed the same political bias; Chaucer attaching himself to John of Ghent, Duke of Lancaster, by whom, as well as by the Duchess Blanche, he was greatly esteemed; and Gower giving his influence to Thomas of Woodstock, both uncles to King Richard II.—would naturally produce a considerable degree of friendship and esteem between the two poets.

Gower did not long survive his friend Chaucer. In the first year of the reign of Henry IV. he appears to have lost his sight; but whether from accident or from old age (for he was then greatly advanced in years) is not known. This misfortune happened but a short period before his death, which took place in the year 1402, about nine years after he had completed the "Confessio Amantis," a work from whence he derived the honour of being ranked among the English poets.

The "Confessio" of Gower is said to have owed its origin to a request made to the poet by King Richard II.; who, accidentally meeting Gower on the Thames, called him into the royal barge, and enjoined him "to booke some new thing." [pg 227]This, therefore, was not the first of his poetical productions, though it is universally admitted to have been his chief, and that on which his principal reputation depends; and into which "it seems to have been his ambition to crowd all his erudition." It is, however, the last of the volumes, the titles which are painted on his monument in this church, and is supposed to be the last he ever wrote, at least of any important extent.

The poetical histories of Gower and Chaucer are intimately connected; yet there is a remarkable difference of opinion and pursuit in their respective writings. It must be confessed that to Chaucer, and not to Gower, should be applied the flattering appellation of "the father of our poetry;" though, as Johnson says, he was the first of our authors who can be said to have written English. To Chaucer, however, are we indebted for the first effort to emancipate the British muse from the ridiculous trammels of French diction, with which, till his time, it had been the fashion to interlard and obscure the English language. Gower, on the contrary, from a close intimacy with the French and Latin poets, found it easier to follow the beaten track. His first work was, therefore, written in French measure, and is entitled "Speculum Meditantis." There are two copies of this book now in the Bodleian Library at Oxford. It contains ten books, and consists of a collection of precepts and examples, compiled from various authors, recommending the chastity of the marriage bed.

Gower's next work was a Latin production, entitled, "Vox Clamantis," of which there are many copies still extant. The unfortunate reign of the poet's royal patron, and the rebellion of Wat Tyler, furnished Gower with ample materials for this publication.—The "Confessio Amantis" was first printed in the year 1403, by Caxton.

There is a MS. in Trinity College, Cambridge, consisting of several small poems by Gower; but they are nearly destitute of merit. The French sonnets, however, of which there is a volume in the Marquess of Stafford's library, are spoken of by Mr. Warton, who has given a long account of them, with specimens, as possessing more merit.

The "Boke of Philip Sparrow," by the witty, but obscene Skelton, who wrote towards the close of the fifteenth century, says that "Gower's Englishe is old;" but the learned Dean Collet, in the early part of the succeeding century, studied not only Gower, but Chaucer, and even Lydgate, in order to improve and correct his own style. By the close of that century, however, the language of these writers was become entirely obsolete.

The "Confessio Amantis" was printed, a second time, by Barthelet, in the year 1532; a third time in 1544; a fourth in 1554; and, lastly, in a very correct and worthy manner, in the year 1810, under the judicious inspection of Dr. Chalmers.

It were ungrateful to withhold from Gower some acknowledgment of the share he had in producing a beneficial revolution in the English language; as it would be absurd and untrue to attribute to him any great degree of praise, as an inventor in that important work.

The church of St. Saviour was founded before the conquest, but was principally rebuilt in the fourteenth century, since which time it has undergone many extensive reparations at different periods. The tower, which is surmounted by four pinnacles, was repaired in 1818 and 1819; and the choir has been recently restored in conformity with the original design, under the superintendence of that indefatigable architect, Mr. George Gwilt.2 The dramatists, Fletcher and Massinger were buried in this church in one grave; and from the tower, Hollar drew his Views of London, both before and after the fire.

Besides the tomb of Gower, there are monuments to Launcelot Andrews, Bishop of Winchester; Richard Humble, Alderman of London, erected in 1616; and several others. Gower's monument was once very splendid, but its present state is not very indicative of the gratitude of the parish in which he perpetuated his munificence by erecting one of the finest churches in the metropolis.

In 1737, so slight and infrequent was the intercourse betwixt London and Edinburgh, that men still alive (1818) remember that upon one occasion the mail from the former city arrived at the General Post-Office in Scotland, with only one letter in it—Scott's Novels.

———————Our first father

Smiled with superior love, as Jupiter

On Juno smiles, when he impregns the clouds,

That shed May flowers, and pressed her matron lip

With kisses pure.

Par. Lost, b. 4, 1. 499—502.

————Kissing the world begun,

And I hope it will never be done

Old Song.

Kissing has been practised in various modes, and for various purposes, from a period of very remote antiquity. Among the ancient oriental nations, presents from a superior were saluted by kissing, to express gratitude and submission to the person conferring the favour. Reference is made to this custom, Genesis, ch. xl. v. 41, "According to thy words shall my people be ruled;" or, as the margin, supported by most eminent critics, renders it, "At thy mouth shall my people kiss." The consecration of the Jewish kings to the regal authority was sealed by a kiss from the officiator in the ceremony: 1 Sam. ch. x. v. 1. Kissing was also employed in the heathen worship as a religious rite. Cicero mentions a statue of Hercules, the chin and lips of which were considerably worn by the repeated kissing of the worshippers. When too far removed to be approached in this manner, it was usual to place the right hand upon the statue, and return it to the lips. That traces of these customs remain to the present day, kissing the Testament on oath in our courts of judicature, and kissing the hand as a respectful salute, afford sufficient evidence. But it is with kissing as a mode of expressing affection or endearment that we are principally concerned, and its use, as such, is of equal (perhaps greater) antiquity with any of the preceding usages. To the passage cited, MIRROR, No. 357, by Professor Childe Wilful, on this subject, may be added the meeting of Telemachus and Ulysses on the return of the latter from Troy, as described, Odyssey, lib. 16, v. 186—218; and the history of the courtship of the patriarch Jacob and the "fair damsel" Rachel, Genesis, ch. xxix. v. 11. This last authority, though it must be acknowledged not so classical as the foregoing, is nevertheless much more piquant, being perhaps the oldest record of amorous kissing extant. Thou seest, therefore, courteous reader, that this "divine custom," in addition to the claims upon thee which it intrinsically possesseth, and which are neither few nor small, hath moreover the universal suffrage of the highest antiquity; thou seest that its date, so far from being confined to the Trojan or Saxon age, can with certainty be traced to patriarchal times; yea, verily, and I cannot find it in me to rest here, without conducting thee to an era even more remote. Revert thine eye to the motto at the head of this chapter. Doth it not carry thee back in spirit to the very baby hours of creation, the "good old days of Adam and Eve?" and doth it not represent unto thee this delightful art as known and practised in full perfection, "when young time told his first birth-days by the sun?" I grant thee that such an authority is not sufficiently critical to fix with precision the "ab initio" of the custom; yet doth it not possess infinite claim upon thy credence? and more especially when thou considerest that, our respectable progenitors, the antediluvians, were visited with the deluge of waters for little else than their license. Vide chap. vi. of the first book of Moses called Genesis, passim. In a world, of which almost all we know with certainty is its uncertainty, and that "the fashion thereof passeth away," it is only a natural inquiry whether the custom of kissing hath, like most others, undergone any material alteration. Perhaps from its nature, it is as little subjected to versatility from the lapse of ages as any; yet still, to say that it has experienced some change, would not be hazarding a very improbable opinion. Who knows but the "clamorous smack" wherewith the Jehu of an eight-horse wagon salutes the lips of his rosy inamorata, (scarcely less audible than the crack of his heavy thong on Smiler's dull sides,) may have been perfectly consistent with the acmé of politesse some centuries bygone. We speak here somewhat confidently. Hear what an amorous votary of the Muses in the olden time, Robert Herrick, saith with respect to kissing:—.

"Pout your joined lips—then speak your kiss."

If this were the present orthodox creed of kissing, it would most woefully spoil the sport of many a gallant youth, who, with the most polite officiousness, extinguishes (by pure accident of course) while professing to snuff, the candles, only that he may snatch a hasty, unobserved kiss of the smiling maiden, whose proximity hath so irresistibly tempted him. I wish the professor who hath already obliged us with a chapter on kissing, would lay us under greater and more manifold obligations, by a course of lectures on the same subject; and if I laid wagers, I would wager my judgment to a cockle-shell, that Socrates' discourse on marriage did not produce a more beneficial effect than would [pg 229] his lecture; and that few untasted lips would be found, either among his auditors, or those whose fortune it should be to fall in the way of those auditors; but as it is at present, (for, alas! these are not the days of Polydore Virgil or Erasmus,) we are compelled, albeit somewhat grumblingly, to be content with but a very limited share of such blisses. Not that I doubt (heaven forbid that I should) the real inclination or the ability of at least the juvenile part of my fair countrywomen to be much more liberal than they generally are in this way; but, "dear, confounded creatures," as Will Honeycomb says, what with the trammels of education and domestic restraint, they are prevented from appearing, as they "really are, the best good-natured things alive." So much innocent hypocrisy, so much mauvaise honte, so many of "the whispered no, so little meant," that they are practical antitheses to themselves. "Can danger lurk within a kiss." But all fathers are not Coleridges, nor are all mothers Woolstonecrafts.

I plead not for libertinism, though only in so simple and innocent a form as kissing. I do not long for the repetition (or more properly commencement) of Polydore Virgil's days of "promiscuous" kisses. Let these remain, as heretofore, in fiction, and in fiction alone. "A glutted market makes provisions cheap," saith Pope. True, saith experience.

"———The lip that all may press,

Shall never more be pressed by mine,"

saith Moore. Sic ego. But there is a medium to be observed between gluttony and absolute starvation, and "medio tutis-simus ibis," saith the proverb; and I do beg to tell those over cautious ladies and gentlemen, who seem to know no medium between the cloistered nun and the abandoned profligate, that Nature will prevail in their spite, or, as Obadiah wisely and truly said, "When lambs meet they will play." And now, reader, kind, courteous, gentle, or whatever thou art, I bid thee adieu, with the hope, that if we agree at this, we may meet again on some future occasion. IOTA.

Why she came to the university was best known to herself. I cannot bring myself always to analyze the motives of people's actions; and if Mrs. Welborn really desired, in lieu of acting mamma to children she did not possess, to play the part of gouvernante to a couple of wild, uncouth lads, (her nephews,) during their residence in college, it speaks much for her good nature, at all events. They were not, I believe, grateful for the means she adopted to display this amiable trait in her disposition, nor did people in general appreciate it as they surely ought to have done. Ill nature—and there is often a frightful preponderance of that quality in a small town—did not hesitate to assert that the widow Welborn's motive for pitching her tent amid scholastic shades was in toto a selfish one; even that of a design, if she could but accomplish it, of adding another self to self. I dare not, in this era of refinement, speak plainer, but will take for granted that I am understood. The widow Welborn, or, as she was more commonly termed. "The gay Widow" from certain gregarious propensities, resided with a couple of female servants in a small house, situated in the most public street of the town; which I know, for this reason,—the principal court of our college was opposite to it, and its gateway was the approved lounge, from morning till night, of the most idle and impudent amongst us. Various were the surmises as to who, what, and from whence the gay widow was; by many she was supposed to be immensely rich; and by a few, some lady of quality incog. Many, however, asserted, that her jewels were glass; her gold, tinsel, and her glittering ornaments, beads sewed upon pasteboard. Nevertheless, in the very face of this shameful detraction, to her delightful little soirées flocked the best families in the town, (there were not many,) the heads of houses, (scarcely room had they in her mansion for their bodies,) and many a, fellow, senior and junior, of many a college in——. I had the honour of attending sometimes at these parties, of which all that I remember at present is, that the sugar was nipped into pieces so small, as to oblige those who liked their tea sweet to put in two or three spoonsfull, instead of an equal quantum of lumps, to the astonishment and visible dismay of the waiters. There was generally, too, a sad deficiency in cake; and, oh! when the negus was handed round,——Well, perhaps her nephews drew largely upon her stock of wine; or the widow possibly thought her young men got too much of that commodity in our parties, and therefore needed it less in her own. As to the senior members of the university, I never could comprehend the reasons that induced their endurance of such an aqueous beverage. Sometimes I [pg 230] have attributed their visits to Mrs. Welborn's merely to a ramification of that system of espionage which she thought proper to employ upon her nephews, and they to extend indiscriminately towards every undergraduate; whereas being myself a well-intentioned, modest young man, mine own honour has seemed grievously insulted; but again, may not vanity, the hope, paramount in the breast of every individual, of being admired by "a fortune," have influenced these old gentlemen to swallow lukewarm potations, (minus wine, lemon, and sugar,) which were a kind of nutmeg broth? I can certainly aver, that old Rightangle, of our college, was, or pretended to be, desperately enamoured with the gay widow; indeed, his doleful looks at one period, and his shyness of the fair lady in question, were to me pretty evident proofs that he had made her an offer, which had been rejected. The gossips of —— had long set it down as a match, but were, it seems, doomed to be disappointed of their cake and wine. I honestly believe that the widow hated Rightangle; and conscientiously declare, to the best of my knowledge, that her antipathy towards my very excellent tutor arose from the circumstance of his having a large red nose, and winning her money whenever they played at the same card-table. Strange stories were afloat respecting the menage of Mrs. Welborn; my bed-maker affirmed, upon her (?) honour and veracity, that a lady and gentleman, who had favoured her with a visit, had quitted her residence thrice thinner than they were when they entered it; and that a gentleman had hastily departed from the shelter of her hospitable roof, upon her refusing him the indulgence of a Welsh rabbit at breakfast! These, and similar tales, were promulgated by the treacherous industry of the widow's maid-servants. Mrs. Welborn was fond of claiming an intimate acquaintance with people of rank. I never, however, met any titled person at her house. She was a kind of living peerage, and an animated chronicle of the actions of the great, virtuous and vicious: but, if the truth must be spoken,—and in a private memoir, why conceal it?—she had acquaintances of a grade far inferior! I say not that I saw it, because I was never accustomed to lounge at our college gate; but the men that were most frequently there, insist that they have many times beheld the gay widow steal forth in the dusk of the evening, dressed as for a party, and have tracked her to the house of a haberdasher in the vicinity! Well! she is married now, and is Mrs. Welborn—the gay widow no longer. How she accomplished this affair I know not; it broke like a thunder-clap upon the ears of the good people of—. Suddenly, the widow was gone—her house and furniture were sold—the happy event was announced in the papers—no cake was sent out—so the gossips were disappointed; and as I have since learnt, that the lady has thrice undergone a separation from her husband, I imagine that she must have been so likewise.

M. L. B.

This beautiful little volume has, in less than six months, reached a fourth edition, which is to us a proof that the readers of the present day know how to discriminate pure gold from pinchbeck or petit or, and intense, natural feeling from the tinsel and tissues of flimsy "poetry." The booksellers, nevertheless, say that poetry is unsaleable, and they are usually allowed to speak feelingly on the score of popularity and success. Yet within a very short time, we have seen a splendid poem—the "Pelican Island," by (the) Montgomery; the "Course of Time," a Miltonic composition, by the Rev. Mr. Pollock; and now we have before us a poem, of which on an average, an edition has been sold in six weeks. The sweeping censure that poems are unsaleable belongs then to a certain grade of poetry which ought never to have strayed out of the album in which it was first written, except for the benefit of the stationer, printer, and the newspapers. Nearly all the poetry of this description is too bizarre, and wants the pathos and deep feeling which uniformly characterize true poetry, and have a lasting impression on the reader: whereas, all the "initial" celebrity, the honied sweetness, lasts but for a few months, and then drops into oblivion.

The story of the Sorrows of Rosalie (there's music in the name) is not of uncommon occurrence; would to heaven it were more rare. Rosalie, won by her omnipotent lover, Arthur, leaves her aged father; is deceived by promises of marriage, and at length deserted by her seducer. She seeks her betrayer in London, (where the many-headed monster, vice, may best conceal herself,) is repulsed, and after enduring all the bitterness [pg 231] of cruelty, hunger, and remorse, she returns to her father's house; but nothing of him and his remains but his memory and his tomb. She is then driven to dishonesty to supply the cravings of her child—is tried and acquitted. During her imprisonment, the child dies; distress brings on her temporary insanity; but she at length flies to a secluded part of the country, and there seeks a solace for her miseries in making peace with her offended Maker.

We can only detach a few portions of the poem, just to show the intensity with which even common scenes and occurrences are worked up. Here is a picture of Rosalie's happy home:

Home of my childhood! quiet, peaceful home!

Where innocence sat smiling on my brow,

Why did I leave thee, willingly to roam,

Lured by a traitor's vainly-trusted vow?

Could they, the fond and happy, see me now,

Who knew me when life's early summer smiled,

They would not know 'twas I, or marvel how

The laughing thing, half woman and half child,

Could e'er be changed to form so squalid, wan, and wild.

I was most happy—witness it, ye skies,

That watched the slumbers of my peaceful night!

Till each succeeding morning saw me rise

With cheerful song, and heart for ever light;

No heavy gems—no jewel, sparkling bright,

Cumbered the tresses nature's self had twined;

Nor festive torches glared before my sight;

Unknowing and unknown, with peaceful mind,

Blest in the lot I knew, none else I wished to find.

I had a father—a gray-haired old man,

Whom Fortune's sad reverses keenly tried;

And now his dwindling life's remaining span,

Locked up in me the little left of pride,

And knew no hope, no joy, no care beside.

My father!—dare I say I loved him well?

I, who could leave him to a hireling guide?

Yet all my thoughts were his, and bitterer fell

The pangs of leaving him, than all I have to tell.

And oh! my childhood's home was lovelier far

Than all the stranger homes where I have been;

It seem'd as if each pale and twinkling star

Loved to shine out upon so fair a scene;

Never were flowers so sweet, or fields so green,

As those that wont that lonely cot to grace

If, as tradition tells, this earth has seen

Creatures of heavenly form and angel race.

They might have chosen that spot to be their dwelling place.

The first approach of her lover is thus told:

He came—admired the pure and peaceful scene,

And offer'd money for our humble cot.

Oh! justly burn'd my father's cheek, I ween,

"His sires by honest toil the dwelling got;

Their home was not for sale." It matters not

How, after that, Lord Arthur won my love.

He smiled contemptuous on my humble lot,

Yet left no means untried my heart to move,

And call'd to witness his the glorious heavens above.

Oh! dimmed are now the eyes he used to praise,

Sad is the laughing brow where hope was beaming,

The cheek that blushed at his impassioned gaze

Wan as the waters where the moon is gleaming;

For many a tear of sorrow hath been streaming

Down the changed face, which knew no care before;

And my sad heart, awakened from its dreaming,

Recalls those days of joy, untimely o'er,

And mourns remembered bliss, which can return no more.

It was upon a gentle summer's eve,

When Nature lay all silently at rest—

When none but I could find a cause to grieve,

I sought in vain to soothe my troubled breast,

And wander'd forth alone, for well I guess'd

That Arthur would be lingering in the bower

Which oft with summer garlands I had drest;

Where blamelessly I spent full many an hour

Ere yet I felt or love's or sin's remorseless power.

No joyful step to welcome me was there;

For slumber had her transient blessing sent

To him I loved—the still and balmy air,

The blue and quiet sky, repose had lent,

Deep as her own—above that form I bent,

The rich and clustering curls I gently raised,

And, trembling, kissed his brow—I turned and went—

Softly I stole away, nor, lingering, gazed;

Fearful and wondering still, at my own deed amazed.

Her first pangs of sorrow at quitting home:

"Oh, Arthur! stay"—he turned, and all was o'er—

My sorrow, my repentance—all was vain—

I dreamt the dream of life and love once more,

To wake to sad reality of pain.

He spoke, but to my ear no sound was plain,

Until the little wicket-gate we passed—

That sound of home I never heard again,

And then "drive on—drive faster—yet more fast."

I raised my weeping head—Oh! I had looked my last.

One of those precious moments in which remorse overtakes the victims of crime, is thus finely drawn:

Months passed: one evening, as of early days,

When first my bosom thrilled his voice to hear,

And thought upon the gentle words of praise

Which forced my lips to smile, and chased my fear:

I sang—a sob, deep, single, struck my ear;

Wondering, I gazed on Arthur, bending low—

His features were concealed, but many a tea,

Quick gushing forth, continued fast to flow,

Stood where they fell, then sank like dew-drops on the snow.

Oh yes! however cold in after years,

At least it cost thee sorrow then to leave me;

And for those few sincere, remorseful tears,

I do forgive (though thou couldst thus deceive me)

The years of peace of which thou didst bereave me.

Yes—as I saw those gushing life-drops come

Back to the heart which yet delayed to grieve me,

Thy love returned a moment to its home,

Far, far away from me for ever then to roam.

He deserts her:

Still hope was left me, and each tedious hour

Was counted as it brought his coming near;

And joyfully I watched each fading flower;

Each tree, whose shadowy boughs grew red and sear;

And hailed sad Autumn, favourite of the year.

At length my time of sorrow came—'twas over,

A beauteous boy was brought me, doubly dear,

For all the Tears that promise caused to hover

Round him—'twas past—I claimed a husband in my lover.

On her return to her paternal cottage:

"My father' oh, my father!" vain the cry—

I had no father now; no need to say

"Thou art alone!." I felt my misery—

My father, yet return,—return! the day

When sorrow had availed is passed away:

Tears cannot raise the dead, grief cannot call

Back to the earthy corse the spirit's ray—

Vainly eternal tears of blood might fall;

One short year since, he lived—my hopes now perished all!

The tale then concludes:

Years have gone by—my thoughts have risen higher—

I sought for refuge at the Almighty's throne;

And when I sit by this low mould'ring fire,

With but my Bible, feel not quite alone.

Lingering in peace, till I can lay me down,

Quiet and cold in that last dwelling place,

By him o'er whose young head the grass is grown—

By him who yet shall rise with angel face,

Pleading for me, the lost and sinful of my race.

And if I still heave one reluctant sigh—

If earthly sorrows still will cross my heart—

If still to my now dimmed and sunken eye

The bitter tear, half checked, in vain will start;

I hid the dreams of other days depart,

And turn, with clasping hands, and lips compress'd,

To pray that Heaven will soothe sad memory's smart;

Teach me to bear and calm my troubled breast;

And grant her peace in Heaven who not on earth may rest.

The author of this exquisite volume is the daughter of the late Thomas Sheridan, and is described as a young and lovely woman, moving in a fashionable sphere.

In this edition are several minor pieces, and others not before published, some of which are of equal merit with the specimens we have here quoted.

Of the numerous pilgrims who arrive at Mekka before the caravan, some are professed merchants; many others bring a few articles for sale, which they dispose of without trouble. They then pass the interval of time before the Hadj, or pilgrimage, very pleasantly; free from cares and apprehensions, and enjoying that supreme happiness of an Asiatic, the dolce far niente. Except those of a very high rank, the pilgrims live together in a state of freedom and equality. They keep but few servants; many, indeed, have none, and divide among themselves the various duties of housekeeping, such as bringing the provisions from market and cooking them, although accustomed at home to the services of an attendant. The freedom and oblivion of care which accompany travelling, render it a period of enjoyment among the people of the East as among Europeans; and the same kind of happiness results from their residence at Mekka, where reading the Koran, smoking in the streets or coffee-houses, praying or conversing in the mosque, are added to the indulgence of their pride in being near the holy house, and to the anticipation of the honours attached to the title of hadjy for the remainder of their lives; besides the gratification of religious feelings, and the hopes of futurity, which influence many of the pilgrims. The hadjys who come by the caravans pass their time very differently. As soon as they have finished their tedious journey, they must undergo the fatiguing ceremonies of visiting the Kaaba and Omra; immediately after which, they are hurried away to Arafat and Mekka, and, still heated from the effects of the journey, are exposed to the keen air of the Hedjaz mountains under the slight and inadequate covering of the ihram: then returning to Mekka, they have only a few days left to recruit their strength, and to make their repeated visits to the Beitullah, when the caravan sets off on its return; and thus the whole pilgrimage is a severe trial of bodily strength, and a continual series of fatigues and privations. This mode of visiting the holy city is, however, in accordance with the opinions of many most learned Moslem divines, who thought that a long residence in the Hedjaz, however meritorious the intention, is little conducive to true belief, since the daily sight of the holy places weakened the first impressions made by them. Notwithstanding the general decline of Musselman zeal, there are still found Mohammedans whose devotion induces them to visit repeatedly the holy places.—Burckhardt's Travels in Arabia.

The botanical garden of St. Petersburg, like all the rest of the institutions, is of gigantic dimensions. It contains sixty-five acres: a parallelogram formed by three parallel lines of hot-houses and conservatories, united at the extremities by covered corridors, constitutes the grand feature of this establishment. The south line contains green-house plants in the centre, and hot-house plants at each end; the middle line has hot-house plants only, and the north line is filled with green-house plants. The connecting corridors are two hundred and forty-five feet. The north and south line contain respectively five different compartments of one hundred toises each, that is to say, they are together six thousand feet. The middle line has seven compartments, that is, three thousand more, making in the whole length nine thousand feet!—Granville's Travels.

The engraving represents an elegant complimentary piece of plate, presented by the Committee for managing the Eisteddvod, held at Denbigh, September, 1828, to Dr. Jones, their Honorary Secretary, for his valuable services on that occasion.

Mr. Ellis, of John-street, Oxford-street, Medalist to the Royal Cambrian institution, was requested to execute (for this purpose) after his own design, a drinking goblet of an ancient form. Mr. E. thought of the Hirlas Horn, and he has completed a beautiful and unique piece of workmanship. It is an elegantly carved horn, about eighteen inches long, brilliantly polished, and richly mounted, the cover highly ornamented with chased oak leaves, and the tip adorned with an acorn; the horn resting on luxuriant branches of an oaken tree, exquisitely finished in chased silver. Around the cover is engraved the following inscription:—"Presented by the Cymmrodorion in Gwynedd, to RICHARD PHILLIPS JONES, M.D. for his unwearied exertions in promoting the Royal Eisteddvod, held at Denbigh, 1828." The horn (the inside of which is lined with silver,) will contain about three half pints; and we doubt not that it will be often passed around, filled with Cwrw da, in remembrance of the interesting event which it is intended to commemorate—

"And former times renew in converse sweet."

The origin of the Hirlas Horn is as follows:—

About 1160, Owain Cyveiliog, one of the most distinguished Princes of Powis, flourished; he was a great warrior and an eminent poet; several specimens of his writings are given in the Archaiology of Wales, published by the late patriotic Owain Jones Myfyr. His poem called the Hirlas Horn (the long blue horn,) is a masterpiece. It used to be the custom with the prince, when he had gained a battle, to call for the horn, filled with metheglin, or mead, and drink the contents at one draught, then sound it to show that there was no deception; each of his officers following his example. Mrs. Hemans has given a beautiful song, in Parry's second volume of Welsh Melodies, on the subject, concluding thus:—

"Fill higher the HIRLAS' forgetting not those

Who shar'd its bright draught in the days which are fled!

Tho' cold on their mountains the valiant repose,

Their lot shall be lovely—renown to the dead!

While harps in the hall of the feast shall be strung,

While regal ERYRI3 with snow shall be crown'd—

So long by the bard shall their battles be sung,

And the heart of the hero shall burn at the sound:

The free winds of Cambria shall swell with their name,

And OWAIN's rich HIRLAS be fill'd to their fame!"

It may be observed, that although many of the bird tribe seem to prefer the vicinity of the residence of man for their domicile, yet they, for the most part, avoid cities and large towns, for one, among other reasons, because there is no food for them. There are, notwithstanding, [pg 234] some remarkable exceptions to this. The House Sparrow is to be seen, I believe, in every part of London. There is a rookery in the Tower; and another was, till lately, in Carlton Palace Gardens; but the trees having been cut down to make room for the improvements going on there, the rooks removed in (1827,) to some trees behind the houses in New-street, Spring-gardens. There was also, for many years, a rookery on the trees in the churchyard of St. Dunstan's in the East, a short distance from the Tower; the rooks for some years past deserted that spot, owing, it is believed, to the fire that occurred a few years ago at the old Custom House. But in 1827, they began again to build on those trees, which are not elm, but a species of plane. There was also, formerly, a rookery on some large elm trees in the College Garden behind the Ecclesiastical Court in Doctors' Commons, a curious anecdote concerning which has been recorded.

The Stork, and some other of the tribe of waders, are occasionally also inhabitants of some of the continental towns.

Rooks appear to be peculiarly partial to building their nests in the vicinity of the residence of man. Of the numerous rookeries of which I have any recollection, most of them were a short distance from dwelling houses. In March, 1827, there was a rookery on some trees, neither very lofty nor very elegant, in the garden of the Royal Naval Asylum, at Greenwich; and although many very fine and lofty elms are in the park near, which one might naturally suppose the rooks would prefer, yet, such is the fact, there is not even one rook's nest in Greenwich Park. Possibly the company of so large a number of boys, and the noise which they make, determine these birds in the choice of such a place for their procreating domicile.

There is also a remarkable fact related by Mr. French, on the authority of Dr. Spurgin, in the second volume of the Zoological Journal, which merits attention, in regard to the rook.

A gentleman occupied a farm in Essex, where he had not long resided before numerous rooks built their nests on the trees surrounding his premises; the rookery was much prized; the farmer, however, being induced to hire a larger farm about three quarters of a mile distant, he left the farm and the rookery; but, to his surprise and pleasure, the whole rookery deserted their former habitation and came to the new one of their old master, where they continue to flourish. It ought to be added, that this gentleman was strongly attached to all animals whatsoever, and of course used them kindly.

The Swallow, Swift, and Martin, seem to have almost deserted London, although they are occasionally, though not very plentifully, to be seen in the suburbs. Two reasons may be assigned for this relative to the swallow; flies are not there so plentiful as in the open country; and most of the chimneys have conical or other contracted tops to them, which, if they do not preclude, are certainly no temptation to their building in such places; the top of a chimney being, as is well known, its favourite site for its nest. The Martin is also scarce in London. But, during the summer of 1820, I observed a Martin's nest against a blind window in Goswell Street Road, on the construction of which the Martins were extremely busy in the early part of the month of August. I have since seen many Martins, (August, 1826,) busily engaged in skimming over a pool in the fields, to the south of Islington: most of these were, I conjecture, young birds, as they were brown, not black; but they had the white on the rump, which is characteristic of the species. A few days afterwards I observed several Martin's nests in a blind window on Islington-Green. And, Sept. 20, of the same year, I saw from the window of my present residence, in Dalby Terrace, City Road, many similar birds actively on the wing.

The Redbreast has been, I am told, occasionally seen in the neighbourhood of Fleet-market and Ludgate-hill. I saw it myself before the window of my present residence, Dalby Terrace, in November, 1825, and in Nov. 1826, the Wren was seen on the shrubs in the garden before the house at Dalby Terrace; it was very lively and active, and uttered its peculiar chit, chit.

The Starling builds on the tower at Canonbury, in Islington; and the Baltimore Oriole is, according to Wilson, found very often on the trees in some of the American cities; but the Mocking-bird, that used to be very common in the American suburban regions, is, it is said, now becoming more rare, particularly in the neighbourhood of Philadelphia.

The Thrush was also often heard in the gardens behind York-place, during the spring of 1826. I heard it myself in delightful song early in March, 1826, among the trees near the canal, on the north side of the Regent's Park.

Some of the migratory birds approach much nearer to London than is generally imagined. The Cuckoo and Wood-pigeon are heard occasionally in Kensington-gardens. The Nightingale approaches also much nearer to London than has been [pg 235] commonly supposed. I heard it in melodious song at seven o'clock in the morning, in the wood near Hornsey-wood House, May 10, 1826, which is, I believe, the nearest approach to St. Paul's it has been for some time known to make. It is also often heard at Hackney and Mile-end. I have also heard it regularly for some years past in a garden near the turnpike-gate on the road leading from London to Greenwich, a short distance from the third mile stone from London-Bridge. This charming bird may be also heard, during the season, in Greenwich Park, particularly in the gardens adjoining Montagu-house; but never, I believe, on its lofty trees. The Nightingale prefers copses and bushes to trees; the Cuckoo, on the contrary, prefers trees, and of these the elm, from which it most probably obtains its food. The Nightingale is also common at Lee and Lewisham, Forest-hill, Sydenham, and Penge-wood; in all these places, except Hackney and Mile-end, I have myself often heard it, and in the day-time. Those who are partial to the singing of birds generally, will find the morning, from four to nine o'clock, the most favourable time for hearing them——Jennings's Ornithologia.

In the centre of the heavens above us, the sun began to break through the mist, forming a clear space, which, as it grew wider by the gradual retreat of the mist and clouds, was enclosed or surrounded by a complete circle of hazy light, much brighter than the general aspect of the atmosphere, but not so brilliant as the sun itself. This circle was about half as broad as the apparent size of the sun, through which it seemed to pass, while on each side of the sun, at about the distance of a sixth of the circumference of the ring, which likewise traversed them, were situated two mock suns, resembling the real sun in everything but brightness, and on the opposite side of the circle two other mock suns were placed, distant from each other about a third of the circuit of the band of light, forming altogether five suns, one real and four fictitious luminaries, through which a broad hoop of subdued light ran round an area of slightly hazy blue sky. The centre of this area was occupied by a small segment of a rainbow, the concave side of which was turned from the true sun, while on its convex edge, in contact with it at its most prominent part, was stretched a broad straight band of prismatic colours, similar to the rainbow in all but curvature. Across the space, within the circle of light, there was a broad stream of dusky cloud, formed of three distinct streaks, and reaching from one of the most distant mock suns to another opposite to it, in the shape of a low arch; but in a little while one extremity of this bar moved away from its original position, while the other end remained stationary, leading me to suppose that it was merely an accidental piece of cloud.

As noon approached, or rather as the clouds dispersed, the blue hazy sky extended beyond the ring of light, and while the day advanced, and the heavens grew more clear, the whole meteor gradually disappeared, the circle vanishing first, and then the imitative suns. My companions assured me they had never before witnessed a similar exhibition during voyages in these seas; but more learned Thebans describe them as phenomena frequently witnessed in high latitudes, and have assigned them the designation of parhelia. There was, during this solar panorama, a large and complete semicircle of haze, lighter in colour than the surrounding fog, resting on the horizon perpendicularly, like a rainbow, but this appearance my associates informed me was familiar to their sight.—Tales of a Voyager in the Arctic Ocean.

"Talking of broiling steaks—when I was in Egypt we used to broil our beef-steaks on the locks—no occasion for fire—thermometer at 200—hot as h-ll! I have seen four thousand men at a time cooking for the whole army as much as twenty or thirty thousand pounds of steaks at a time, all hissing and frying at a time—just about noon, of course, you know—not a spark of fire! Some of the soldiers who had been brought up as glass-blowers at Leith swore they never saw such heat. I used to go to leeward of them for a whiff, and think of old England! Ay! that's the country, after all, where a man may think and say what he pleases! But that sort of work did not last long, as you may suppose; their eyes were all fried out, —— me, in three or four weeks! I had been ill in my bed, for I was attached to the 72nd regiment, seventeen hundred strong. I had a party of seamen with me; but the ophthalmia made such ravages, that the whole regiment, colonel and all, went stone-blind—all, except one corporal! You may stare, gentlemen, but it's very true. Well, this corporal had a precious time of it: he was obliged [pg 236] to lead out the whole regiment to water—he led the way, and two or three took hold of the skirts of his jacket on each side; the skirts of these were seized again by as many more; and double the number to the last, and so all held on by one another, till they had all had a drink at the well; and, as the devil would have it, there was but one well among us all—so this corporal used to water the regiment just as a groom waters his horses; and all spreading out, you know, just like the tail of a peacock."—"Of which the corporal was the rump," interrupted the doctor. The captain looked grave. "You found it warm in that country?" inquired the surgeon. "Warm!" exclaimed the captain; "I'll tell you what, doctor, when you go where you have sent many a patient, and where, for that very reason, you certainly will go, I only hope, for your sake, and for that of your profession in general, that you will not find it quite so hot as we found it in Egypt. What do you think of nineteen of my men being killed by the concentrated rays of light falling on the barrels of the sentinels' bright muskets, and setting fire to the powder? I commanded a mortar battery at Acre, and I did the French infernal mischief with the shells. I used to pitch in among them when they had sat down to dinner; but how do you think the scoundrels weathered on me at last? —— me, they trained a parcel of poodle dogs to watch the shells when they fell, and then to run and pull the fusees out with their teeth. Did you ever hear of such villains? By this means they saved hundreds of men, and only lost half-a-dozen dogs—fact, by——; only ask Sir Sydney Smith, he'll tell you the same, and a—— sight more." * * * * He continued his lies, and dragged in as usual the name of Sir Sydney Smith to support his assertions. "If you doubt me, only ask Sir Sydney Smith; he'll talk to you about Acre for thirty-six hours on a stretch, without taking breath; his cockswain at last got so tired of it, that he nick-named him 'Long Acre.'" * * * "Capital salmon this," said the captain; "where does Billet get it from? By the by, talking of that, did you ever hear of the pickled salmon in Scotland?" We all replied in the affirmative. "Oh, you don't take. Hang it, I don't mean dead pickled salmon; I mean live pickled salmon, swimming about in tanks, as merry as grigs, and as hungry as rats." We all expressed our astonishment at this, and declared we never heard of it before. "I thought not," said he, "for it has only lately been introduced into this country by a particular friend of mine, Dr. Mac—. I cannot just now remember his——, jaw-breaking, Scotch name; he was a great chemist and geologist, and all that sort of thing—a clever fellow, I can tell you, though you may laugh. Well, this fellow, sir, took Nature by the heels, and capsized her, as we say. I have a strong idea that he had sold himself to the d—l. Well, what does he do, but he catches salmon and puts them into tanks, and every day added more and more salt, till the water was as thick as gruel, and the fish could hardly wag their tails in it. Then he threw in whole pepper-corns, half-a-dozen pounds at a time, till there was enough. Then he began to dilute with vinegar until his pickle was complete. The fish did not half like it at first; but habit is every thing; and when he showed me his tank, they were swimming about as merry as a shoal of dace: he fed them with fennel, chopped small, and black pepper-corns. 'Come, doctor,' says I, 'I trust no man upon tick; if I don't taste I won't believe my own eyes, though I can believe my tongue.' (We looked at each other.) 'That you shall do in a minute,' says he; so he whipped one of them out with a landing-net; and when I stuck my knife into him, the pickle ran out of his body like wine out of a claret-bottle, and I ate at least two pounds of the rascal, while he flapped his tail in my face. I never tasted such salmon as that. Worth your while to go to Scotland, if it's only for the sake of eating live pickled salmon. I'll give you a letter, any of you, to my friend. He'll be d—d glad to see you; and then you may convince yourselves. Take my word for it, if once you eat salmon that way, you will never eat it any other."—The Naval Officer.

On the evening of April 8, 1814, De Bausset left Blois, commissioned by Josephine to deliver at Paris, a letter to the Emperor of Austria, and afterwards another at Fontainbleau to her husband. Having executed the first part of this commission, he set out at two in the morning of the 11th of April for Fontainbleau, and arrived at the palace about nine o'clock. He was introduced to Napoleon immediately, and gave him the letter from the empress. "Good Louise!" exclaimed Napoleon, after having read it, and then asked numerous questions as to her health and that of his son. De Bausset expressed his wish to carry back an answer to the empress, and Napoleon promised to give him a [pg 237] letter in the afternoon. He was calm and decided; but his tones were milder, and his manners mere gentle than was his wont. He began talking about Elba, and showed to De B. the maps and books of geography which he had been consulting on the subject of his future little empire. "The air is good," said he, "and the inhabitants well-disposed: I shall not be very ill off there, and I hope Marie-Louise will put up with it as well as I shall." He knew that for the present they were not to meet, but his hope was that when she was once in the possession of the duchy of Parma, she and his son would be allowed to reside with him in the island. But he never saw either again. The prince of Neufchâtel, Berthier, entered the room to demand permission to go to Paris on his private affairs; he would return the next day. After he had left the room, Napoleon said with a melancholy tone:—"Never! he will never return hither!" "What, sire!" replied Maret, who was present, "can that be the farewell of your Berthier?" "Yes! I tell you; he will not return." He did not. At two o'clock in the afternoon Napoleon sent again for De Bausset. He was walking on the terrace under the gallery of Francis I. He questioned De B. as to all he had seen or heard during the late events; he found great fault with the measure adopted by the council in leaving Paris; the letter to his brother, upon which they acted, had been written under very different circumstances; the presence of Louise at Paris would have prevented the treason and defection of many of his soldiers, and he should still have been at the head of a formidable army, with which he could have forced his enemies to quit France and sign an honourable peace. De B. expressed his regret that peace had not been made at Châtillon. "I never could put any confidence," said Napoleon, "in the good faith of our enemies. Every day they made fresh demands, imposed fresh conditions; they did not wish to have peace—and then—I had declared publicly to all France that I would not submit to humiliating terms, although the enemy were on the heights of Montmartre." De B. remarked that France within the Rhine would be one of the finest kingdoms in the world; on which Napoleon, after a pause, said—"I abdicate; but I yield nothing." He ran rapidly over the characters of his principal officers, but dwelt on that of Macdonald. "Macdonald," said he, "is a brave and faithful soldier; it is only during these late events that I have fully appreciated his Worth; his connexion with Moreau prejudiced me against him: but I did him injustice, and I regret much that I did not know him better." Napoleon paused; then after a minute's silence—"See," said he, "what our life is! In the action at Arcis-sur-Aube I fought with desperation, and asked nothing but to die for my country. My clothes were torn to pieces by musket balls—but alas! not one could touch my person! A death which I should owe to an act of despair would be cowardly; suicide does not suit my principles nor the rank I have holden in the world. I am a man condemned to live." He sighed almost to sobbing;—then, after several minutes' silence, he said with a bitter smile—"After all they say, a living camp-boy is worth more than a dead emperor,"—and immediately retired into the palace. It was the last time De Bausset ever saw his master.

This day, beyond all contradiction,

This day is all thine own, Queen Fiction!

And thou art building castles boundless

Of groundless joys, and griefs as groundless;

Assuring beauties that the border

Of their new dress is out of order;

And schoolboys that their shoes want tying;

And babies that their dolls are dying.

Lend me, lend me, some disguise;

I will tell prodigious lies:

All who care for what I say

Shall be April fools to-day.

First I relate how all the nation

Is ruined by Emancipation:

How honest men are sadly thwarted;

How beads and faggots are imported;

How every parish church looks thinner;

How Peel has asked the Pope to dinner;

And how the Duke, who fought the duel,

Keeps good King George on water-gruel.

Thus I waken doubts and fears

In the Commons and the Peers;

If they care for what I say,

They are April fools to-day.

Next I announce to hall and hovel

Lord Asterisk's unwritten novel.

It's full of wit, and full of fashion,

And full of taste, and full of passion;

It tells some very curious histories,

Elucidates some charming mysteries,

And mingles sketches of society

With precepts of the soundest piety.

Thus I babble to the host

Who adore the "Morning Post;"

If they care for what I say.

They are April fools to-day.

Then to the artist of my raiment

I hint his bankers have stopped payment;

And just suggest to Lady Locket

That somebody has picked her pocket—

And scare Sir Thomas from the city,

By murmuring, in a tone of pity,

That I am sure I saw my Lady

Drive through the Park with Captain Grady.

Off my troubled victims go,

Very pale and very low;

If they care for what I say,

They are April fools to-day.

I've sent the learned Doctor Trepan

To feel Sir Hubert's broken kneepan;

'Twill rout doctor's seven senses

To find Sir Hubert charging fences!

I've sent a sallow parchment scraper

To put Miss Trim's last will on paper;

He'll see her, silent as a mummy,

At whist with her two maids and dummy.

Man of brief, and man of pill,

They will take it very ill;

If they care for what I say,

They are April fools to-day.

And then to her, whose smiles shed light on

My weary lot last year at Brighton,

I talk of happiness and marriage,

St. George's and a travelling carriage.

I trifle with my rosy fetters,

I rave about her 'witching letters,

And swear my heart shall do no treason

Before the closing of the season.

Thus I whisper in the ear

Of Louisa Windermere—

If she cares for what I say,

She's an April fool to-day.

And to the world I publish gaily

That all things are improving daily;

That suns grow warmer, streamlets clearer,

And faith more firm, and love sincerer—

That children grow extremely clever—

That sin is seldom known, or never—

That gas, and steam, and education,

Are, killing sorrow and starvation!

Pleasant visions—but, alas

How those pleasant visions pass!

If you care for what I say,

You're an April fool to-day.

Last, to myself, when night comes round me,

And the soft chain of thought has bound me,

I whisper, "Sir, your eyes are killing—

You owe no mortal man a shilling—

You never cringe for star or garter,

You're much too wise to be a martyr—

And since you must, be food for vermin,

You don't feel much desire for ermine!"

Wisdom is a mine, no doubt,

If one can but find it out—

But whate'er I think or say,

I'm an April fool to-day,

London Magazine.

A widow of the name of Betty Falla kept an alehouse in one of the market-towns frequented by the Lammermuir ladies, (Dunse, we believe,) and a number of them used to lodge at her house during the fair. One year Betty's ale turned sour soon after the fair; there had been a thunder-storm in the interim, and Betty's ale was, as they say in that country, "strongest in the water." Betty did not understand the first of these causes, and she did not wish to understand the latter. The ale was not palatable; and Betty brewed again to the same strength of water. Again it thundered, and again the swipes became vinegar. Betty was at her wit's end,—no long journey; but she was breathless.

Having got to her own wit's end, Betty naturally wished to draw upon the stock of another; and where should she find it in such abundance as with the minister of the parish. Accordingly, Betty put on her best, got her nicest basket, laid a couple of bottles of her choicest brandy in the bottom, and over them a dozen or two of her freshest eggs; and thus freighted, she fidgetted off to the manse, offered her peace-offering, and hinted that she wished to speak with his reverence in "preevat."

"What is your will, Betty?" said the minister of Dunse. "An unco uncanny mishap," replied the tapster's wife.

"Has Mattie not been behaving?" said the minister. "Like an innocent lamb," quoth Betty Falla.

"Then—?" said the minister, lacking the rest of the query. "Anent the yill," said Betty.

"The ale!" said the minister; "has any body been drinking and refused to pay?"

"Na," said Betty, "they winna drink a drap."

"And would you have me to encourage the sin of drunkenness?" asked the minister.

"Na, na," said Betty, "far frae that; I only want your kin' han' to get in yill again as they can drink."

"I am no brewer, Betty," said the minister gravely.

"Gude forfend, Sir," said Betty, "that the like o' you should be evened to the gyle tub. I dinna wish for ony thing o' the kind."—"Then what is the matter?" asked the minister.

"It's witched, clean witched; as sure as I'm a born woman," said Betty.

"Naebody else will drink it, an' I canna drink it mysel'."

"You must not be superstitious, Betty," said the minister. "I'm no ony thing o' the kin'," said Betty, colouring, "an' ye ken it yoursel'; but twa brousts wadna be vinegar for naething." (She lowered her voice.) "Ye mun ken, Sir, that o' a' the leddies frae the Lammermuir, that hae been comin' and gaen, there was an auld rudas wife this fair, an' I'm certie she's witched the yill; and ye mun just look into ye'r buiks, an' tak off the withchin!"

"When do you brew, Betty?"—"This blessed day, gin it like you, Sir."

"Then, Betty, here is the thing you want, the same malt and water as usual?"

—"Nae difference, Sir?"

"Then when you have put the water to the malt, go three times round the vat with the sun, and in pli's name put in three shoolfu's of malt; and when you have done that, go three times round the vat, against the sun, and, in the devil's name, take out three bucketfuls of water; and take my word for it, the ale will be better."

"Thanks to your reverence; gude mornin."—Ibid.

"A snapper-up of unconsidered trifles."

SHAKSPEARE.

The sun was sunk beneath the hills,

The western clouds were lin'd with gold,

The sky was clear, the winds were still,

The flocks were pent within their fold:

When from the silence of the grove,

Poor Damon thus despair'd of love.

Who seeks to pluck the fragrant rose

From the bare rock, or oozy beach,

Who from each barren weed that grows,

Expects the grape, or blushing peach.

With equal faith may hope to find

The truth of love in woman-kind.

I have no herds, no fleecy care,

No fields that wave with golden grain,

No meadows green, or gardens fair,

A damsel's venal heart to gain.

Then all in vain my sighs must prove,

For I, alas! have naught but love.

How wretched is the faithful youth,

Since women's hearts are bought and

sold,

They ask no vows of sacred truth,

Whene'er they sigh, they sigh for gold.

Gold can the frowns of scorn remove,

But I, alas! have naught but love.

To buy the gems of India's coast,

What gold, what treasure will suffice,

Not all their fire can ever boast

The living lustre of her eyes.

For thee the world too cheap must prove,

But I, alas! have naught but love.

O Sylvia! since no gems, nor ore

Can with thy brighter charms compare,

Consider that I proffer more

More seldom found, a heart sincere.

Let treasure meaner beauty's move,

Who pays thy worth, must pay in love.

The following "announcement" is so characteristic and amusing, that we copy it verbatim et literatim:—The author of "Whims and Oddities" has the honour of informing the public, that, encouraged by the popularity of the Ballads in the first and second series of that work, he intends to communicate a succession of similar vocal crotchets, to run alone without the help of an octavo. Sally Brown, Faithless Nelly Gray, and Mary's Ghost, have been patronised by many public and private singers; but unfortunately they were adapted to as many airs—sometimes even to jigs; and the natural result was an occasional falling-out between the words and the melodies. Judging that it would be better for those verses to be regularly married to music, than that they should form temporary connexions with any rambling tunes about town, Mr. J. Blewitt has at last kindly provided them with airs that are airs of character, and made their alliance with music of the correct and permanent kind. The same gentleman has undertaken the same good office for the forthcoming Comic Ballads; and his well-known skill and talent will insure that all unhappy differences between Sound and Sense will be amicably composed. In fact, the words and the airs will be intended for each other from the cradle—like Paul and Virginia. It is intended that the new Ballads shall start in couples. Two to make a Number, and a number of Numbers may be bound to the library, as a volume, for a term of years. The work will be set with variations. Occasionally there will be a duet or trio, to accommodate those timid vocalists who do not choose to make themselves particular in a solo, or those other singers of sociable habits who prefer giving tongue in a pack. One word about the words. They will be "merry and wise." Not a jest will be admitted that might be liable to misconstruction by the Council of Nice. The Comic Muse has been too apt to mistake liberty for license, and has been proportionably licentious; the Comic Ballads will be as particular as Seneca or Aesop in their regard for good morals. Nothing, in short, will be inserted but what is cut out for the female ear. To conclude—the said Melodies will be issued by Messrs. Clementi and Co., of Cheapside. Be sure to ask for "Comic Melodies," as all others are counterfeits, and not benefits, to the proprietors. The first Number is expected to commence, like Blue Bonnets, with "March;" and the work will be continued regularly through every other month in the calendar.

The other day, a man of ninety-nine was buried at Père-la-chaise, at Paris, and was followed to his grave by twenty children, fifteen grand-children and great grand-children. Happily, such populators are not common! The deceased, it appears, had buried six wives, and married the seventh: he died in the full enjoyment of his senses, and assured his numerous progeny that he did not regret life, as he knew he was about to rejoin the six beloved partners of his days, who had gone before him. Few men, we fear, would be consoled by such an idea in their last moments, or at any moment of their existence!—Literary Gaz.

The following is the last and best that we have heard of the above-named gentleman. We should premise, that, the details of it are a little altered, with the view of adapting it to "ears polite;" for without some process of this kind, it would not have been presentable. A lady went to the doctor in great distress of mind, and stated to him, that, by a strange accident, she had swallowed a live spider. At first, his only reply was, "whew! whew! whew!" a sort of internal whistling sound, intended to be indicative of supreme contempt. But his anxious patient was not so easily to be repulsed. She became every moment more and more urgent for some means of relief from the dreaded effect of the strange accident she had consulted him about; when, at last, looking round upon the wall, he put up his hand and caught a fly. "There, ma'am," said he, "I've got a remedy for you. Open your mouth; and as soon as I've put this fly into it, shut it close again; and the moment the spider hears the fly buzzing about, up he'll come; and then you can spit them both out together."

Lovesick people e'en will smile,

In spite of cares, and for the while

Sadness will not lag on:

Tic dolereux will lose its power

On facial nerves for half an hour,

Now Listen plays Moll Flaggon.

J. S. C.

At Astracan, Feb. 19, the cold was 28 deg. below the zero of Reaumur.

A volume of poems by the King of Bavaria has just been published at Munich, the profits of which are to be given to an institution devoted to the blind.

The late Mr. Henry Hase succeeded Abraham Newland, as cashier at the Bank of England. Newland is buried in St. Saviour's Church, Southwark. The lyrical celebrity of Abraham Newland will not be forgotten in our times.

A fine white lion and the largest bear died here last week. This bear was the largest of the three in the pit, and was considered to have been the finest in England. He usually seized the largest share of cakes and fruit, and snorted and snarled whenever his companions secured any. He had latterly grown so fat that he could with difficulty ascend the pole; and after eating his usual breakfast, he expired suddenly. Like many other animals we could name, his greatness was his mortal foe—and as Hume grew too pursy to write, so our four-footed friend became too gross to climb. Toby, with all his ill-treatment and attachment to strong ale, is still alive and well.

Man is a glass, life is the water,

That's weakly walled about:

Sin brings in death, death breaks the glass,

So runs the water out.

GEO. F.

When on her love, with heart sincere,

The maid bestowed her hand, she dropt a tear.

Delightful omen of her life's employ,

For they who sow in tears shall reap in joy.

J. R. R.

Echard, in his "History of England," gives us the rates or prices of the following provisions in the year 1299, being the 27th of Edward I.:—A fat cock, 1-1/2d.; a goose, 4d.; a fat capon, 2-1/2d.; 2 pullets, 1-1/2d.; a mallard, 1-1/2d.; a pheasant, 4d.; a heron, 6d.; a plover, 1d.; a swan, 3s.; a crane. 1s.; 2 wood-cocks, 1-1/2d.; a fat lamb, (from Christmas to Shrovetide,) 1s. 4d., and all the year after 4d. only. Lastly, wheat was sold for 20d. the quarter, and in some places for 6d., or 4s. of our money.

| s. | d. | |

| Mackenzie's Man of Feeling | 0 | 6 |

| Paul and Virginia | 0 | 6 |

| The Castle of Otranto | 0 | 6 |

| Almoran and Hamet | 0 | 6 |

| Elizabeth, or the Exiles of Siberia | 0 | 6 |

| The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne | 0 | 6 |

| Rasselas | 0 | 8 |

| The Old English Baron | 0 | 8 |

| Nature and Art | 0 | 8 |

| Goldsmith's Vicar of Wakefield | 0 | 10 |

| Sicilian Romance | 1 | 0 |

| The Man of the World | 1 | 0 |

| A Simple Story | 1 | 4 |

| Joseph Andrews | 1 | 6 |

| Humphry Clinker | 1 | 8 |

| The Romance of the Forest | 1 | 8 |

| The Italian | 2 | 0 |

| Zeluco, by Dr. Moore | 2 | 6 |

| Edward, by Dr. Moore | 2 | 0 |

| Roderick Random | 2 | 6 |

| The Mysteries of Udolpho | 3 | 6 |

Printed and Published by J. LIMBIRD, 143, Strand (near Somerset House,) London; sold by ERNEST FLEISCHER, 626, New Market, Leipsic, and by all Newsmen and Booksellers.

Footnote 2: (return)Only the tower and the choir have yet been restored; but the fidelity with which these portions have been executed, heightens our anxiety for the renovation of the whole structure. The repairs of the south transept will, we believe, be shortly commenced, but the fate of the nave and aisles is not yet decided. These are in a dilapidated condition.

Mr. Gwilt has already expended much time and research into the history of this very interesting structure. On our last week-day visit to the church, we saw the fine arch of a Saxon door just uncovered after a concealment of many ages, in one of the surveys of this erudite artist, who is sedulously attached to the study of antiquities, and is an honour to his profession. We ought not to forget the altar-screen which has lately been restored under Mr. Gwilt's superintendence. Indeed, the inspection of this venerable fabric will repay a walk from the most remote corner of the metropolis.

Printed and published by J LIMBIRD, 143, Strand, (near Somerset House,) and sold by all Newsmen and Booksellers.