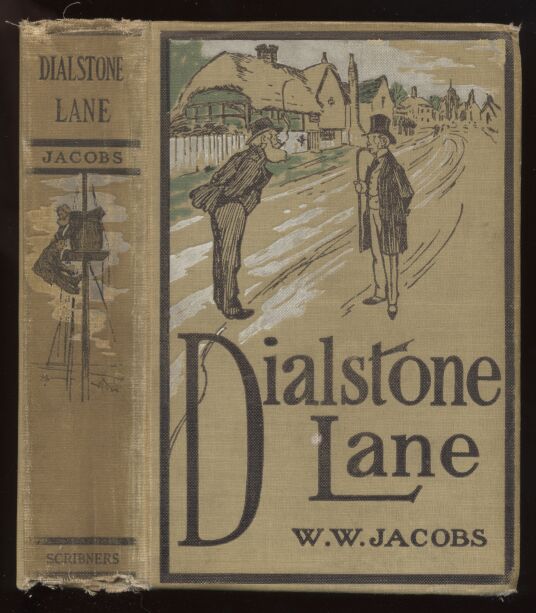

Title: Dialstone Lane, Part 5.

Author: W. W. Jacobs

Illustrator: Will Owen

Release date: April 1, 2004 [eBook #11975]

Most recently updated: December 26, 2020

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/11975

Credits: Produced by David Widger

"He Led the Reluctant Man As Far from The Helmsman As Possible and Whispered the Information."

"The 'fair Emily' Had Disappeared."

"Mr. Chalk, With the Air of an Old Campaigner, Made A Small Fire and Prepared Breakfast."

"Her Friend Gazed Long and Mournfully at a Large Photograph of Mr. Stobell."

"Miss Vickers Stood Wiping Her Hands on Her Coarse Apron."

"Selina Gives Twopence on Account."

"I Told Him That You Would Like to Hear It."

"Half Binchester Had Congregated to Welcome Their Fellow-townsmen."

"'Halloa! What Do You Want?' he Inquired"

"'It'll Be All Right,' Said Brisket, Puffing at His Cigar."

"Then Tredgold, With his Back to the Others, Caught His Eye and Frowned Significantly."

"They Stared Solemnly up Dialstone Lane."

Month by month the Fair Emily crept down south. The Great Bear and other constellations gave way to the stars of the southern skies, and Mr. Chalk tried hard not to feel disappointed with the arrangement of those in the Southern Cross. Pressed by the triumphant Brisket, to whom he voiced his views, he had to admit that it was at least as much like a cross as the other was a bear.

As they got farther south he had doffed his jersey and sea boots in favour of a drill suit and bare feet. In this costume, surmounted by a Panama hat, he was the only thing aboard that afforded the slightest amusement to Mr. Stobell, whose temper was suffering severely under a long spell of monotonous idleness, and whose remarks concerning the sea and everything in connection with it were so strangely out of keeping with the idea of a pleasure cruise that Mr. Tredgold lectured him severely on his indiscretion.

"Stobell is no more doing this for pleasure than I am," said Captain Brisket to Mr. Duckett. "It's something big that's brought him all this way, you mark my words."

The mate nodded acquiescence. "What about Mr. Chalk?" he said, in a low voice. "Can't you get it out of him?"

"Shuts up like an oyster directly I get anywhere near it," replied the captain; "sticks to it that it is a yachting trip and that Tredgold is studying the formations of islands. Says he has got a list of them he is going to visit."

"Mr. Tredgold was talking the same way to me," said the mate. "He says he's going to write a book about them when he goes back. He asked me what I thought'ud be a good title."

"I know what would be a good title for him," growled Brisket, as Mr. Stobell came on deck and gazed despondently over the side. "We're getting towards the end of our journey, sir."

"End?" said Mr. Stobell. "End? I don't believe there is an end. I believe you've lost your way and we shall go sailing on and on for ever."

He walked aft and, placing himself in a deckchair, gazed listlessly at the stolid figure of the helmsman. The heat was intense, and both Tredgold and Chalk had declined to proceed with a conversation limited almost entirely on his side to personal abuse. He tried the helmsman, and made that unfortunate thirsty for a week by discussing the rival merits of bitter ale in a pewter and stout in a china mug. The helmsman, a man of liberal ideas, said, with some emotion, that he could drink either of them out of a flower-pot.

Mr. Chalk became strangely restless as they neared their goal. He had come thousands of miles and had seen nothing fresh with the exception of a few flying-fish, an albatross, and a whale blowing in the distance. Pacing the deck late one night with Captain Brisket he expressed mild yearnings for a little excitement.

"You want adventure," said the captain, shaking his head at him. "I know you. Ah, what a sailorman you'd ha' made. With a crew o' six like yourself I'd take this little craft anywhere. The way you pick up seamanship is astonishing. Peter Duckett swears you must ha' been at sea as a boy, and all I can do I can't persuade him otherwise."

"I always had a feeling that I should like it," said Mr. Chalk, modestly.

"Like it!" repeated the captain. "O' course you do; you've got the salt in your blood, but this peaceful cruising is beginning to tell on you. There's a touch o' wildness in you, sir, that's always struggling to come to the front. Peter Duckett was saying the same thing only the other day. He's very uneasy about it."

"Uneasy!" repeated Mr. Chalk.

"Aye," said the captain, drawing a deep breath. "And if I tell you that I am too, it wouldn't be outside the truth."

"But why?" inquired Mr. Chalk, after they had paced once up and down the deck in silence.

"It's the mystery we don't like," said Brisket, at last. "How are we to know what desperate venture you are going to let us in for? Follow you faithful we will, but we don't like going in the dark; it ain't quite fair to us."

"There's not the slightest danger in the world," said Mr. Chalk, with impressive earnestness.

"But there's a mystery; you can't deny that," said the captain.

Mr. Chalk cleared his throat. "It's a secret," he said, slowly.

"From me?" inquired the captain, in reproachful accents.

"It isn't my secret," said Mr. Chalk. "So far as I'm concerned I'd tell you with pleasure."

The captain slowly withdrew his arm from Mr. Chalk's, and moving to the side leaned over it with his shoulders hunched. Somewhat moved by this display of feeling, Mr. Chalk for some time hesitated to disturb him, and when at last he did steal up and lay a friendly hand on the captain's shoulder it was gently shaken off.

"Secrets!" said Brisket, in a hollow voice. "From me! I ain't to be trusted?"

"It isn't my doing," said Mr. Chalk.

"Well, well, it don't matter, sir," said the captain. "Bill Brisket must put up with it. It's the first time in his life he's been suspected, and it's doubly hard coming from you. You've hurt me, sir, and there's no other man living could do that."

Mr. Chalk stood by in sorrowful perplexity.

"And I put my life in your hands," continued the captain, with a low, hard laugh. "You're the, only man in the world that knows who killed Smiling Peter in San Francisco, and I told you. Well, well!"

"But you did it in self-defence," said the other, eagerly.

"What does that matter?" said the captain, turning and walking forward, followed by the anxious Mr. Chalk. "I've got no proof of it. Open your mouth—once—and I swing for it. That's the extent of my trust in you."

Mr. Chalk, much affected, swore a few sailorly oaths as to what he wished might happen to him if he ever betrayed the other's confidence.

"Yes," said the captain, mournfully, "that's all very well; but you can't trust me in a smaller matter, however much I swear to keep it secret. And it's weighing on me in another way: I believe the crew have got an inkling of something, and here am I, master of the ship, responsible for all your lives, kept in ignorance."

"The crew!" ejaculated the startled Mr. Chalk.

Captain Brisket hesitated and lowered his voice. "The other night I came on deck for a look round and saw one of them peeping down through your skylight," he said, slowly. "I sent him below, and after he'd gone I looked down and saw you and Mr. Tredgold and Stobell all bending over a paper."

Mr. Chalk, deep in thought, paced up and down in silence.

"That's a secret," said Brisket. "I don't want them to think that I was spying. I told you because you understand. A shipmaster has to keep his eyes open, for everybody's sake."

"It's your duty," said Mr. Chalk, firmly.

Captain Brisket, with a little display of emotion, thanked him, and, leaning against the side, drew his attention to the beauty of the stars and sea. Impelled by the occasion and the charm of the night he waxed sentimental, and with a strange mixture of bluffness and shyness spoke of his aged mother, of the loneliness of a seafarer's life, and the inestimable boon of real friendship. He bared his inmost soul to his sympathetic listener, and then, affecting to think from a remark of Mr. Chalk's that he was going to relate the secret of the voyage, declined to hear it on the ground that he was only a rough sailorman and not to be trusted. Mr. Chalk, contesting this hotly, convinced him at last that he was in error, and then found that, bewildered by the argument, the captain had consented to be informed of a secret which he had not intended to impart.

"But, mind," said Brisket, holding up a warning finger, "I'm not going to tell Peter Duckett. There's no need for him to know."

Mr. Chalk said "Certainly not," and, seeing no way for escape, led the reluctant man as far from the helmsman as possible and whispered the information. By the time they parted for the night Captain Brisket knew as much as the members of the expedition themselves, and, with a rare thoughtfulness, quieted Mr. Chalk's conscience by telling him that he had practically guessed the whole affair from the beginning.

He listened with great interest a few days later when Mr. Tredgold, after considering audibly which island he should visit first, gave him the position of Bowers's Island and began to discuss coral reefs and volcanic action. They were now well in among the islands. Two they passed at a distance, and went so close to a third—a mere reef with a few palms upon it—that Mr. Chalk, after a lengthy inspection through his binoculars, was able to declare it uninhabited.

A fourth came into sight a couple of days later: a small grey bank on the starboard bow. Captain Brisket, who had been regarding it for some time with great care, closed his glass with a bang and stepped up to Mr. Tredgold.

"There she is, sir," he said, in satisfied tones.

Mr. Tredgold, who was drinking tea, put down his cup, and rose with an appearance of mild interest. Mr. Stobell followed suit, and both gazed in strong indignation at the undisguised excitement of Mr. Chalk as he raced up the rigging for a better view. Tredgold with the captain's glass, and Stobell with an old pair of field-glasses in which he had great faith, gazed from the deck. Tredgold was the first to speak.

"Are you sure this is the one, Brisket?" he inquired, carelessly.

"Certainly, sir," said the captain, in some surprise. "At least, it's the one you told me to steer for."

"Don't look much like the map," said Stobell, in a low aside. "Where's the mountain?"

Tredgold looked again. "I fancy it's a bit higher towards the middle," he said, after a prolonged inspection; "and, besides, it's 'mount,' not 'mountain.'"

Captain Brisket, who had with great delicacy drawn a little apart in recognition of their whispers, stepped towards them again.

"I don't know that I've ever seen this particular island before," he said, frankly; "likely not; but it's the one you told me to find. There's over a couple of hundred of them, large and small, knocking about. If you think you've made a mistake we might try some of the others."

"No," said Tredgold, after a pause and a prolonged inspection; "this must be right."

Mr. Chalk came down from aloft, his eyes shining with pure joy, and joined them.

"How long before we're alongside?" he inquired.

"Two hours," replied the captain; "perhaps three," he added, considering.

Mr. Chalk glanced aloft and, after a knowing question or two as to the wind, began in a low voice to converse with his friends. Mr. Tredgold's misgivings as to the identity of the island he dismissed at once as baseless. The mount satisfied him, and when, as they approached nearer, discrepancies in shape between the island and the map were pointed out to him he easily explained them by speaking of the difficulties of cartography to an amateur.

"There's our point," he said, indicating it with a forefinger, which the incensed Stobell at once struck down. "We couldn't have managed it better so far as time is concerned. We'll sleep ashore tonight in the tent and start the search at daybreak."

Captain Brisket approached the island cautiously. To the eyes of the voyagers it seemed to change shape as they neared it, until finally, the Fair Emily anchoring off the reef which guarded it, it revealed itself as a small island about three-quarters of a mile long and two or three hundred yards wide. A beach of coral sand shelved steeply to the sea, and a background of cocoa-nut trees and other vegetation completed a picture on which Mr. Chalk gazed with the rapture of a devotee at a shrine.

He went below as the anchor ran out, and after a short absence reappeared on deck bedizened with weapons. A small tent, with blankets and provisions, and a long deal box containing a couple of spades and a pick, were put into one of the boats, and the three friends, after giving minute instructions to the captain, followed. Mr. Duckett took the helm, and after a short pull along the edge of the reef discovered an opening which gave access to the smooth water inside.

"A pretty spot, gentlemen," he said, scanning the island closely. "I don't think that there is anybody on it."

"We'll go over it first and make sure," said Stobell, as the boat's nose ran into the beach. "Come along, Chalk."

He sprang out and, taking one of the guns, led the way along the beach, followed by Mr. Chalk. The men looked after them longingly, and then, in obedience to the mate, took the stores out of the boat and pitched the tent. By the time Chalk and Stobell returned they were seated in the boat and ready to depart.

A feeling of loneliness came over Mr. Chalk as he watched the receding boat. The schooner, riding at anchor half a mile outside the reef, had taken in her sails and presented a singularly naked and desolate appearance. He wondered how long it would take the devoted Brisket to send assistance in case of need, and blamed himself severely for not having brought some rockets for signalling purposes. Long before night came the prospect of sleeping ashore had lost all its charm.

"One of us ought to keep watch," he said, as Stobell, after a heavy supper followed by a satisfying pipe, rolled himself in a blanket and composed himself for slumber.

Mr. Stobell grunted, and in a few minutes was fast asleep. Mr. Tredgold, first blowing out the candle, followed suit, while Mr. Chalk, a prey to vague fears, sat up nursing a huge revolver.

The novelty of the position, the melancholy beat of the surge on the farther beach, and faint, uncertain noises all around kept him awake. He fancied that he heard stealthy footsteps on the beach, and low, guttural voices calling among the palms. Twice he aroused his friends and twice they sat up and reviled him.

"If you put your bony finger into my ribs again," growled Mr. Stobell, tenderly rubbing the afflicted part, "you and me won't talk alike. Like a bar of iron it was."

"I thought I heard something," said Mr. Chalk. "I should have fired, only I was afraid of scaring you."

"Fired?" repeated Mr. Stobell, thoughtfully. "Fired? Was it the barrel of that infernal pistol you shoved into my ribs just now?"

"I just touched you with it," admitted the other. "I'm sorry if I hurt you."

Mr. Stobell, feeling in his pocket, struck a match and held it up. "Full cock," he said, in a broken voice; "and he stirred me up with it. And then he talks of savages!"

He struck another match and lit the candle, and then, before Mr. Chalk could guess his intentions, pressed him backwards and took the pistol away. He raised the canvas and threw it out into the night, and then, remembering the guns, threw them after it. This done he blew out the candle, and in two minutes was fast asleep again.

An hour passed and Mr. Chalk, despite his fears, began to nod. Half asleep, he lay down and drew his blanket about him, and then he sat up suddenly wide awake as an unmistakable footstep sounded outside.

For a few seconds he sat unable to move; then he stretched out his hand and began to shake Stobell. He could have sworn that hands were fumbling at the tent.

"Eh?" said Stobell, sleepily.

Chalk shook him again. Stobell sat up angrily, but before he could speak a wild yell rent the air, the tent collapsed suddenly, and they struggled half suffocated in the folds of the canvas.

Mr. Stobell was the first to emerge, and, seizing the canvas, dragged it free of the writhing bodies of his companions. Mr. Chalk gained his feet and, catching sight of some dim figures standing a few yards away on the beach, gave a frantic shout and plunged into the interior, followed by the others. A shower of pieces of coral whizzing by their heads and another terrible yell accelerated their flight.

Mr. Chalk gained the farther beach unmolested and, half crazy with fear, ran along blindly. Footsteps, which he hoped were those of his friends, pounded away behind him, and presently Stobell, panting heavily, called to him to stop. Mr. Chalk, looking over his shoulder, slackened his pace and allowed him to overtake him.

"Wait—for—Tredgold," said Stobell, breathlessly, as he laid a heavy hand on his shoulder.

Mr. Chalk struggled to free himself. "Where is he?" He gasped.

Stobell, still holding him, stood trying to regain his breath. "They— they must—have got him," he said, at last. "Have you got any of your pistols on you?"

"You threw them all away," quavered Mr. Chalk. "I've only got a knife."

He fumbled with trembling fingers at his belt; Stobell brushing his hand aside drew a sailor's knife from its sheath, and started to run back in the direction of the tent. Mr. Chalk, after a moment's hesitation, followed a little way behind.

"Look out!" he screamed, and stopped suddenly, as a figure burst out of the trees on to the beach a score of yards ahead. Stobell, with a hoarse cry, raised his hand and dashed at it.

"Stobell!" cried a voice.

"It's Tredgold," cried Stobell. He waited for him to reach them, and then, turning, all three ran stumbling along the beach.

They ran in silence until they reached the other end of the island. So far there were no signs of pursuit, and Stobell, breathing hard from his unwonted exercise, collected a few lumps of coral and piled them on the beach.

"They had me over—twice," said Tredgold, jerkily; "they tore the clothes from my back. How I got away I don't know. I fought—kicked—then suddenly I broke loose and ran."

He threw himself on the beach and drew his breath in long, sobbing gasps. Stobell, going a few paces forward, peered into the darkness and listened intently.

"I suppose they're waiting for daylight," he said at last.

He sat down on the beach and, after making a few disparaging remarks about coral as a weapon, lapsed into silence.

To Mr. Chalk it seemed as though the night would never end. A dozen times he sprang to his feet and gazed fearfully into the darkness, and a dozen times at least he reminded the silent Stobell of the folly of throwing other people's guns away. Day broke at last and showed him Tredgold in a tattered shirt and a pair of trousers, and Stobell sitting close by sound asleep.

"We must try and signal to the ship," he said, in a hoarse whisper. "It's our only chance."

Tredgold nodded assent and shook Stobell quietly. The silence was oppressive. They rose and peered out to sea, and a loud exclamation broke from all three. The "Fair Emily" had disappeared.

Stobell rubbed his eyes and swore softly; Tredgold and Chalk stood gazing in blank dismay at the unbroken expanse of shining sea.

"The savages must have surprised them," said the latter, in trembling tones. "That's why they left us alone."

"Or else they heard the noise ashore and put to sea," said Tredgold.

They stood gazing at each other in consternation. Then Stobell, who had been looking about him, gave vent to an astonished grunt and pointed to a boat drawn upon the beach nearly abreast of where their tent had been.

"Some of the crew have escaped ashore," said Mr. Chalk.

Striking inland, so as to get the shelter of the trees, they made their way cautiously towards the boat. Colour was lent to Mr. Chalk's surmise by the fact that it was fairly well laden with stores. As they got near they saw a couple of small casks which he thought contained water, an untidy pile of tinned provisions, and two or three bags of biscuit. The closest search failed to reveal any signs of men, and plucking up courage they walked boldly down to the boat and stood gazing stupidly at its contents.

The firearms which Stobell had pitched out of the tent the night before lay in the bottom, together with boxes of cartridges from the cabin, a couple of axes, and a pile of clothing, from the top of which Mr. Tredgold, with a sharp exclamation, snatched a somewhat torn coat and waistcoat. From the former he drew out a bulky pocketbook, and, opening it with trembling fingers, hastily inspected the contents.

"The map has gone!" he shouted.

The others stared at him.

"Brisket has gone off with the ship," he continued, with desperate calmness. "It was the crew of our own schooner that frightened us off last night."

Mr. Stobell, still staring in a stony fashion, nodded slowly; Mr. Chalk after an effort found his voice.

"They've gone off with the treasure," he said, slowly.

"Also," continued Tredgold, "this is not Bowers's Island. I can see it all now. They've only taken the map, and now they're off to the real island to get the treasure. It's as clear as daylight."

"Broad daylight," said Stobell, huskily. "But how did they know?"

"Somebody has been talking," said Tredgold, in a hard voice. "Somebody has been confiding in that honest, open-hearted sailor, Captain Brisket."

He turned as he spoke and gazed fixedly at the open-mouthed Chalk. In a slower fashion, but with no less venom, Mr. Stobell also bent his regards upon that amiable but erring man.

Mr. Chalk returned their gaze with something like defiance. Half an hour before he had expected to have been killed and eaten. He had passed a night of horror, expecting death every minute. Now he exulted in the blue sky, the line of white breakers crashing on the reef, and the sea sparkling in the sunshine; and he had not spent twenty-five years with Mrs. Chalk without acquiring some skill in the noble art of self-defence.

"Ah, Brisket was trying to pump me a week ago," he said, confidentially. "I see it all now."

The others glared at him luridly.

"He said that he had seen us through the skylight studying a paper," continued Mr. Chalk, shaking his head. "I thought at the time you were rather rash, Tredgold."

Mr. Tredgold choked and, meeting the fault-finding eye of Mr. Stobell, began to protest.

"The thing Brisket couldn't understand," said Chalk, gaining confidence as he proceeded, "was Stobell's behaviour. He said that he couldn't believe that a man who grumbled at the sea so much as he did could be sailing for pleasure."

Mr. Stobell glowered fiercely. "Why didn't you tell us before?" he demanded.

"I didn't attach any importance to it," said Mr. Chalk, truthfully. "I thought that it was just curiosity on Brisket's part. It surprised me that he had been observing you and Tredgold so closely; that was all."

"Pity you didn't tell us," exclaimed Tredgold, harshly. "We might have been prepared, then."

"You ought to have told us at once," said Stobell.

Mr. Chalk agreed. "I ought to have done so, perhaps," he said, slowly; "only I was afraid of hurting your feelings. As it is, we must make the best of it. It is no good grumbling at each other.

"If I had had the map instead of Tredgold, perhaps this wouldn't have happened."

"It was a crazy idea to keep it in your coat-pocket," said Stobell, scowling at Tredgold. "No doubt Brisket saw you put it back there the other night, guessed what it was, and laid his plans according."

"If it hadn't been for your grumbling it wouldn't have happened," retorted Tredgold, hotly. "That's what roused his suspicions in the first instance."

Mr. Chalk interposed. "It is no good you two quarrelling about it," he said, with kindly severity. "The mischief is done. Bear a hand with these stores, and then help me to fix the tent up again."

The others hesitated, and then without a word Mr. Stobell worked one of the casks out of the boat and began to roll it up the beach. The tent still lay where it had fallen, but the case of spades had disappeared. They raised the tent again and carried in the stores, after which Mr. Chalk, with the air of an old campaigner, made a small fire and prepared breakfast.

Day by day they scanned the sea for any signs of a sail, but in vain. Cocoa-nuts and a few birds shot by Mr. Stobell—who had been an expert at pigeon-shooting in his youth—together with a species of fish which Mr. Chalk pronounced to be edible a few hours after the others had partaken of it, furnished them with a welcome change of diet. In the smooth water inside the reef they pulled about in the boat, and, becoming bolder and more expert in the management of it, sometimes ventured outside. Mr. Stobell pronounced the life to be more monotonous than that on board ship, and once, in a moment of severe depression, induced by five days' heavy rain, spoke affectionately of Mrs. Stobell. To Mr. Chalk's reminder that the rain had enabled them to replenish their water supply he made a churlish rejoinder.

He passed his time in devising plans for the capture and punishment of Captain Brisket, and caused a serious misunderstanding by expressing his regret that that unscrupulous mariner had not rendered himself liable to the extreme penalty of the law by knocking Mr. Chalk on the head on the night of the attack. His belated explanation that he wished Mr. Chalk no harm was pronounced by that gentleman to be childish.

"We can do nothing to Brisket even if we escape from this place," said Tredgold, peremptorily.

"Do nothing?" roared Stobell. "Why not?"

"In the first place we sha'n't find him," said Tredgold. "After they have got the treasure they will get rid of the ship and disperse all over the world."

Mr. Stobell, with heavy sarcasm, said that once, many years before, he had heard of people called detectives.

"In the second place," continued Tredgold, "we can't explain. It wasn't our map, and, strictly speaking, we had no business with it. Even if we caught Brisket, we should have no legal claim to the treasure. And if you want to blurt out to all Binchester how we were tricked and frightened out of our lives by imitation savages, I don't."

"He stole our ship," growled Stobell, after a long pause. "We could have him for that."

"Mutiny on the high seas," added Chalk, with an important air.

"The whole story would have to come out," said Tredgold, sharply. "Verdict: served them right. Once we had got the treasure we could have given Captain Bowers his share, or more than his share, and it would have been all right. As it is, nobody must know that we went for it."

Mr. Stobell, unable to trust himself with speech, stumped fiercely up and down the beach.

"But it will all have to come out if we are rescued," objected Mr. Chalk.

"We can tell what story we like," said Tredgold. "We can say that the schooner went to pieces on a reef in the night; we got separated from the other boat and made our way here. We have got plenty of time to concoct a story, and there is nobody to contradict it."

Mr. Stobell brought up in front of him and frowned thoughtfully. "I suppose you're right," he said, slowly; "but if we ever get off this chicken-perch, and I run across him, let him look out, that's all."

To pass the time they built themselves a hut on the beach in a situation where it would stand the best chance of being seen by any chance vessel. At one corner stood a mast fashioned from a tree, and a flag, composed for the most part of shirts which Mr. Chalk thought his friends had done with, fluttered bravely in the breeze. It was designed to attract attention, and, so far as the bereaved Mr. Stobell was concerned, it certainly succeeded.

Nearly a year had elapsed since the sailing of the Fair Emily, and Binchester, which had listened doubtfully to the tale of the treasure as revealed by Mr. William Russell, was still awaiting news of her fate. Cablegrams to Sydney only elicited the information that she had not been heard of, and the opinion became general that she had added but one more to the many mysteries of the sea.

Captain Bowers, familiar with many cases of ships long overdue which had reached home in safety, still hoped, but it was clear from the way in which Mrs. Chalk spoke of her husband and the saint-like qualities she attributed to him that she never expected to see him again. Mr. Stobell also appeared to his wife through tear-dimmed eyes as a person of great gentleness and infinite self-sacrifice.

"All the years we were married," she said one afternoon to Mrs. Chalk, who had been listening with growing impatience to an account of Mr. Stobell which that gentleman would have been the first to disclaim, "I never gave him a cross word. Nothing was too good for me; I only had to ask to have."

Mrs. Chalk couldn't help herself. "Why don't you ask, then?" she inquired.

Mrs. Stobell started and eyed her indignantly. "So long as I had him I didn't want anything else," she said, stiffly. "We were all in all to each other; he couldn't bear me out of his sight. I remember once, when I had gone to see my poor mother, he sent me three telegrams in thirty-five minutes telling me to come home."

"Thomas was so unselfish," murmured Mrs. Chalk. "I once stayed with my mother for six weeks and he never said a word."

An odd expression, transient but unmistakable, flitted across the face of the listener.

"It nearly broke his heart, though, poor dear," said Mrs. Chalk, glaring at her. "He said he had never had such a time in his life."

"I don't expect he had," said Mrs. Stobell, screwing up her small features.

Mrs. Chalk drew herself up in her chair. "What do you mean by that?" she demanded.

"I meant what he meant," replied Mrs. Stobell, with a little air of surprise.

Mrs. Chalk bit her lip, and her friend, turning her head, gazed long and mournfully at a large photograph of Mr. Stobell painted in oils, which stared stiffly down on them from the wall.

"He never caused me a moment's uneasiness," she said, tenderly. "I could trust him anywhere."

Mrs. Chalk gazed thoughtfully at the portrait. It was not a good likeness, but it was more like Mr. Stobell than anybody else in Binchester, a fact which had been of some use in allaying certain unworthy suspicions of Mr. Stobell the first time he saw it.

"Yes," said Mrs. Chalk, significantly, "I should think you could."

Mrs. Stobell, about to reply, caught the staring eye of the photograph, and, shaking her head sorrowfully, took out her handkerchief and wiped her eyes. Mrs. Chalk softened.

"They both had their faults," she said, gently, "but they were great friends. I dare say that it was a comfort to them to be together to the last."

Captain Bowers himself began to lose hope at last, and went about in so moody a fashion that a shadow seemed to have fallen upon the cottage. By tacit consent the treasure had long been a forbidden subject, and even when the news of Selina's promissory note reached Dialstone Lane he had refused to discuss it. It had nothing to do with him, he said, and he washed his hands of it—a conclusion highly satisfactory to Miss Vickers, who had feared that she would have had to have dropped for a time her visits to Mr. Tasker.

A slight change in the household occurring at this time helped to divert the captain's thoughts. Mr. Tasker while chopping wood happened to chop his knee by mistake, and, as he did everything with great thoroughness, injured himself so badly that he had to be removed to his home. He was taken away at ten in the morning, and at a quarter-past eleven Selina Vickers, in a large apron and her sleeves rolled up over her elbows, was blacking the kitchen stove and throwing occasional replies to the objecting captain over her shoulder.

"I promised Joseph," she said, sharply, "and I don't break my promises for nobody. He was worrying about what you'd do all alone, and I told him I'd come."

Captain Bowers looked at her helplessly.

"I can manage very well by myself," he said, at last.

"Chop your leg off, I s'pose?" retorted Miss Vickers, good-temperedly. "Oh, you men!"

"And I'm not at home much while Miss Drewitt is away," added the captain.

"All the better," said Miss Vickers, breathing noisily on the stove and polishing with renewed vigour. "You won't be in my way."

The captain pulled himself together.

"You can finish what you're doing," he said, mildly, "and then—"

"Yes, I know what to do," interrupted Miss Vickers. "You leave it to me. Go in and sit down and make yourself comfortable. You ought not to be in the kitchen at all by rights. Not that I mind what people say—I should have enough to do if I did—but still—"

The captain fled in disorder and at first had serious thoughts of wiring for Miss Drewitt, who was spending a few days with friends in town. Thinking better of this, he walked down to a servants' registry office, and, after being shut up for a quarter of an hour in a small room with a middle-aged lady of Irish extraction, who was sent in to be catechized, resolved to let matters remain as they were.

Miss Vickers swept and dusted, cooked and scrubbed, undisturbed, and so peaceable was his demeanour when he returned from a walk one morning, and found the front room being "turned out," that she departed from her usual custom and explained the necessities of the case at some length.

"I dare say it'll be the better for it," said the captain.

"O' course it will," retorted Selina. "You don't think I'd do it for pleasure, do you? I thought you'd sit out in the garden, and of course it must come on to rain."

The captain said it didn't matter.

"Joseph," said Miss Vickers, as she squeezed a wet cloth into her pail— "Joseph's got a nice leg. It's healing very slow."

The captain, halting by the kitchen door, said he was sorry to hear it.

"Though there's worse things than bad legs," continued Miss Vickers, soaping her scrubbing-brush mechanically; "being lost at sea, for instance."

Captain Bowers made no reply. Adopting the idea that all roads lead to Rome, Miss Vickers had, during her stay at Dialstone Lane, made many indirect attempts to introduce the subject of the treasure-seekers.

"I suppose those gentlemen are drowned?" she said, bending down and scrubbing noisily.

The captain, taking advantage of her back being turned towards him, eyed her severely. The hardihood of the girl was appalling. His gaze wandered from her to the bureau, and, as his eye fell on the key sticking up in the lid, the idea of reading her a much-needed lesson presented itself. He stepped over the pail towards the bureau and, catching the girl's eye as she looked up, turned the key noisily in the lock and placed it ostentatiously in his pocket. A sudden vivid change in Selina's complexion satisfied him that his manoeuvre had been appreciated.

"Are you afraid I shall steal anything?" she demanded, hotly, as he regained the kitchen.

The captain quailed. "No," he said, hastily. "Somebody once took a paper of mine out of there, though," he added. "So I keep it locked up now."

Miss Vickers dropped the brush in the pail, and, rising slowly to her feet, stood wiping her hands on her coarse apron. Her face was red and white in patches, and the captain, regarding her with growing uneasiness, began to take in sail.

"At least, I thought they did," he muttered.

Selina paid no heed. "Get out o' my kitchen," she said, in a husky voice, as she brushed past him.

The captain obeyed hastily, and, stepping inside the dismantled room, stood for some time gazing out of window at the rain. Then he filled his pipe and, removing a small chair which was sitting upside down in a large one, took its place and stared disconsolately at the patch of wet floor and the general disorder.

At the end of an hour he took a furtive peep into the kitchen. Selina Vickers was sitting with her back towards him, brooding over the stove. It seemed clear to him that she was ashamed to meet his eye, and, glad to see such signs of grace in her, he resolved to spare her further confusion by going upstairs. He went up noisly and closed his door with a bang, but although he opened it afterwards and stood listening acutely he heard so sound from below.

By the end of the second hour his uneasiness had increased to consternation. The house was as silent as a tomb, the sitting-room was still in a state of chaos, and a healthy appetite would persist in putting ominous and inconvenient questions as to dinner. Whistling a cheerful air he went downstairs again and put his head in at the kitchen. Selina sat in the same attitude, and when he coughed made no response.

"What about dinner?" he said, at last, in a voice which strove to be unconcerned.

"Go away," said Selina, thickly. "I don't want no dinner."

The captain started. "But I do," he said, feelingly.

"You'd better get it yourself, then," replied Miss Vickers, without turning her head. "I might steal a potato or something."

"Don't talk nonsense," said the other, nervously.

"I'm not a thief," continued Miss Vickers. "I work as hard as anybody in Binchester, and nobody can ever say that I took the value of a farthing from them. If I'm poor I'm honest."

"Everybody knows that," said the captain, with fervour.

"You said you didn't want the paper," said Selina, turning at last and regarding him fiercely. "I heard you with my own ears, else I wouldn't have taken it. And if they had come back you'd have had your share. You didn't want the treasure yourself and you didn't want other people to have it. And it wasn't yours, because I heard you say so."

"Very well, say no more about it," said the captain. "If anybody asks you can say that I knew you had it. Now go and put that back in the bureau."

He tossed the key on to the table, and Miss Vickers, after a moment's hesitation, turned with a gratified smile and took it up. The next hour he spent in his bedroom, the rapid evolutions of Miss Vickers as she passed from the saucepans to the sitting room and from the sitting-room back to the saucepans requiring plenty of sea room.

A week later she was one of the happiest people in Binchester. Edward Tredgold had received a cable from Auckland: "All safe; coming home," and she shared with Mrs. Chalk and Mrs. Stobell in the hearty congratulations of a large circle of friends. Her satisfaction was only marred by the feverish condition of Mr. Tasker immediately on receipt of the news.

Fortunately for their peace of mind, Mr. Chalk and his friends, safe on board the s.s. Silver Star, bound for home, had no idea that the story of the treasure had become public property. Since their message it had become the principal topic of conversation in the town, and, Miss Vickers being no longer under the necessity of keeping her share in the affair secret, Mr. William Russell was relieved of a reputation for untruthfulness under which he had long laboured.

Various religious and philanthropic bodies began to bestir themselves. Owing to his restlessness and love of change no fewer than three sects claimed Mr. Chalk as their own, and, referring to his donations in the past, looked forward to a golden future. The claim of the Church to Mr. Tredgold was regarded as flawless, but the case of Mr. Stobell bristled with difficulties. Apologists said that he belonged to a sect unrepresented in Binchester, but an offshoot of the Baptists put in a claim on the ground that he had built that place of worship—at a considerable loss on the contract—some fifteen years before.

Dialstone Lane, when it became known that Captain Bowers had waived his claim to a share, was besieged by people seeking the reversion, and even Mint Street was not overlooked. Mr. Vickers repelled all callers with acrimonious impartiality, but Selina, after a long argument with a lady subaltern of the Salvation Army, during which the methods and bonnets of that organization were hotly assailed, so far relented as to present her with twopence on account.

Miss Drewitt looked forward to the return of the adventurers with disdainful interest. To Edward Tredgold she referred with pride to the captain's steadfast determination not to touch a penny of their ill-gotten gains, and with a few subtle strokes drew a comparison between her uncle and his father which he felt to be somewhat highly coloured. In extenuation he urged the rival claims of Chalk and Stobell.

"They were both led away by Chalk's eloquence and thirst for adventure," he said, as he walked by her side down the garden.

Miss Drewitt paid no heed. "And you will benefit by it," she remarked.

Mr. Tredgold drew himself up with an air the nobleness of which was somewhat marred by the expression of his eyes. "I will never touch a penny of it," he declared. "I will be like the captain. I am trying all I can to model myself on his lines."

The girl regarded him with suspicion. "I see no signs of any result at present," she said, coldly.

Mr. Tredgold smiled modestly. "Don't flatter me," he entreated.

"Flatter you!" said the indignant Prudence.

"On my consummate powers of concealment," was the reply. "I am keeping everything dark until I am so like him—in every particular—that you will not know the difference. I have often envied him the possession of such a niece. When the likeness is perfec——"

"Well?" said Miss Drewitt, with impatient scorn.

"You will have two uncles instead of one," rejoined Mr. Tredgold, impressively.

Miss Drewitt, with marked deliberation, came to a pause in the centre of the path.

"Are you going to continue talking nonsense?" she inquired, significantly.

Mr. Tredgold sighed. "I would rather talk sense," he replied, with a sudden change of manner.

"Try," said the girl, encouragingly.

"Only it is so difficult," said Edward, thoughtfully, "to you."

Miss Drewitt stopped again.

"For me," added the other, hastily. His companion said that she supposed it was. She also reminded him that nothing was easy without practice.

"And I ought not to find it difficult," complained Mr. Tredgold. "I have got plenty of sense hidden away somewhere."

Miss Drewitt permitted herself a faint exclamation of surprise. "It was not an empty boast of yours just now, then," she said.

"Boast?" repeated the other, blankly. "What boast?"

"On your wonderful powers of concealment," said Prudence, gently.

"You are reverting of your own accord to the nonsense," said Mr. Tredgold, sternly. "You are returning to the subject of uncles."

"Nothing of the kind," said Prudence, hotly.

"Before we leave it—for ever," said Mr. Tredgold, dramatically, "I should like, if I am permitted, to make just one more remark on the subject. I would not, for all the wealth of this world, be your uncle Where are you going?"

"Indoors," said Miss Drewitt, briefly.

"One moment," implored the other. "I am just going to begin to talk sense."

"I will listen when you have had some practice," said the girl, walking towards the house.

"It's impossible to practise this," said Edward, following. "It is something that can only be confided to yourself. Won't you stay?"

"No," said the girl.

"Not from curiosity?"

Miss Drewitt, gazing steadfastly before her, shook her head.

"Well, perhaps I can say it as well indoors," murmured Edward, resignedly.

"And you'll have a bigger audience," said Prudence, breathing more easily as she reached the house. "Uncle is indoors."

She passed through the kitchen and into the sitting-room so hastily that Captain Bowers, who was sitting by the window reading, put down his paper and looked up in surprise. The look of grim determination on Mr. Tredgold's face did not escape him.

"Mr. Tredgold has come indoors to talk sense," said Prudence, demurely.

"Talk sense?" repeated the astonished captain.

"That's what he says," replied Miss Drewitt, taking a low chair by the captain's side and gazing composedly at the intruder. "I told him that you would like to hear it."

She turned her head for a second to hide her amusement, and in that second Mr. Tredgold favoured the captain with a glance the significance of which was at once returned fourfold. She looked up just in time to see their features relaxing, and moving nearer to the captain instinctively placed her hand upon his knee.

"I hope," said Captain Bowers, after a long and somewhat embarrassing silence—"I hope the conversation isn't going to be above my head?"

"Mr. Tredgold was talking about uncles," said Prudence, maliciously.

"Nothing bad about them, I hope?" said the captain, with pretended anxiety.

Edward shook his head. "I was merely envying Miss Drewitt her possession of you," he said, carelessly, "and I was just about to remark that I wished you were my uncle too, when she came indoors. I suppose she wanted you to hear it."

Miss Drewitt started violently, and her cheek flamed at the meanness of the attack.

"I wish I was, my lad," said the admiring captain.

"It would be the proudest moment of my life," said Edward, deliberately.

"And mine," said the captain, stoutly.

"And the happiest."

The captain bowed. "Same here," he said, graciously.

Miss Drewitt, listening helplessly to this fulsome exchange of compliments, wondered whether they had got to the end. The captain looked at Mr. Tredgold as though to remind him that it was his turn.

"You—you were going to show me a photograph of your first ship," said the latter, after a long pause. "Don't trouble if it's upstairs."

"It's no trouble," said the captain, briskly.

He rose to his feet and the hand of the indignant Prudence, dislodged from his knee, fell listlessly by her side. She sat upright, with her pale, composed face turned towards Mr. Tredgold. Her eyes were scornful and her lips slightly parted. Before these signs his courage flickered out and left him speechless. Even commonplace statements of fact were denied him. At last in sheer desperation he referred to the loudness of the clock's ticking.

"It seems to me to be the same as usual," said the girl, with a slight emphasis on the pronoun.

The clock ticked on undisturbed. Upstairs the amiable captain did his part nobly. Drawers opened and closed noisily; doors shut and lids of boxes slammed. The absurdity of the situation became unbearable, and despite her indignation at the treatment she had received Miss Drewitt felt a strong inclination to laugh. She turned her head swiftly and looked out of window, and the next moment Edward Tredgold crossed and took the captain's empty chair.

"Shall I call him down?" he asked, in a low voice.

"Call him down?" repeated the girl, coldly, but without turning her head. "Yes, if you——"

A loud crash overhead interrupted her sentence. It was evident that in his zeal the captain had pulled out a loaded drawer too far and gone over with it. Slapping sounds, as of a man dusting himself down, followed, and it was obvious that Miss Drewitt was only maintaining her gravity by a tremendous effort. Much emboldened by this fact the young man took her hand.

"Mr. Tredgold!" she said, in a stifled voice.

Undismayed by his accident the indefatigable captain was at it again, and in face of the bustle upstairs Prudence Drewitt was afraid to trust herself to say more. She sat silent with her head resolutely averted, but Edward took comfort in the fact that she had forgotten to withdraw her hand.

"Bless him!" he said, fervently, a little later, as the captain's foot was heard heavily on the stair. "Does he think we are deaf?"

Much to the surprise of their friends, who had not expected them home until November or December, telegrams were received from the adventurers, one day towards the end of September, announcing that they had landed at the Albert Docks and were on their way home by the earliest train. The most agreeable explanation of so short a voyage was that, having found the treasure, they had resolved to return home by steamer, leaving the Fair Emily to return at her leisure. But Captain Bowers, to whom Mrs. Chalk propounded this solution, suggested several others.

He walked down to the station in the evening to see the train come in, his curiosity as to the bearing and general state of mind of the travellers refusing to be denied. He had intended to witness the arrival from a remote corner of the platform, but to his surprise it was so thronged with sightseers that the precaution was unnecessary. The news of the return had spread like wildfire, and half Binchester had congregated to welcome their fellow-townsmen and congratulate them upon their romantically acquired wealth.

Despite the crowd the captain involuntarily shrank back as the train rattled into the station. The carriage containing the travellers stopped almost in front of him, and their consternation and annoyance at the extent of their reception were plainly visible. Bronzed and healthy-looking, they stepped out on to the platform, and after a brief greeting to Mrs. Chalk and Mrs. Stobell led the way in some haste to the exit. The crowd pressed close behind, and inquiries as to the treasure and its approximate value broke clamorously upon the ears of the maddened Mr. Stobell. Friends of many years who sought for particulars were shouldered aside, and it was left to Mr. Chalk, who struggled along in the rear with his wife, to announce that they had been shipwrecked.

Captain Bowers, who had just caught the word, heard the full particulars from him next day. For once the positions were reversed, and Mr. Chalk, who had so often sat in that room listening to the captain's yarns, swelled with pride as he noted the rapt fashion in which the captain listened to his. The tale of the shipwreck he regarded as a disagreeable necessity: a piece of paste flaunting itself among gems. In a few words he told how the Fair Emily crashed on to a reef in the middle of the night, and how, owing to the darkness and confusion, the boat into which he had got with Stobell and Tredgold was cast adrift; how a voice raised to a shriek cried to them to pull away, and how a minute afterwards the schooner disappeared with all hands.

"It almost unnerved me," he said, turning to Miss Drewitt, who was listening intently.

"You are sure she went down, I suppose?" said the captain; "she didn't just disappear in the darkness?"

"Sank like a stone," said Mr. Chalk, decidedly. "Our boat was nearly swamped in the vortex. Fortunately, the sea was calm, and when day broke we saw a small island about three miles away on our weather-beam."

"Where?" inquired Edward Tredgold, who had just looked in on the way to the office. Mr. Chalk explained.

"You tell the story much better than my father does," said Edward, nodding. "From the way he tells it one might think that you had the island in the boat with you."

Mr. Chalk started nervously. "It was three miles away on our weather-beam," he repeated, "the atmosphere clear and the sea calm. We sat down to a steady pull, and made the land in a little under the hour."

"Who did the pulling?" inquired Edward, casually.

Mr. Chalk started again, and wondered who had done it in Mr. Tredgold's version. He resolved to see him as soon as possible and arrange details.

"Most of us took a turn at it," he said, evasively, "and those who didn't encouraged the others."

"Most of you!" exclaimed the bewildered captain; "and those who didn't— but how many?"

"The events of that night are somewhat misty," interrupted Mr. Chalk, hastily. "The suddenness of the calamity and the shock of losing our shipmates—"

"It's wonderful to me that you can remember so much," said Edward, with a severe glance at the captain.

Mr. Chalk paid no heed. Having reached the island, the rest was truth and plain sailing. He described their life there until they were taken off by a trading schooner from Auckland, and how for three months they cruised with her among the islands. He spoke learnedly of atolls, copra, and missionaries, and, referring for a space to the Fijian belles, thought that their charms had been much overrated. Edward Tredgold, waiting until the three had secured berths in the s.s. Silver Star, trading between Auckland and London, took his departure.

Miss Vickers, who had been spending the day with a friend at Dutton Priors, and had missed the arrival in consequence, heard of the disaster in a mingled state of wrath and despair. The hopes of a year were shattered in a second, and, rejecting with fierceness the sympathy of her family, she went up to her room and sat brooding in the darkness.

She came down the next morning, pale from want of sleep. Mr. Vickers, who was at breakfast, eyed her curiously until, meeting her gaze in return, he blotted it out with a tea-cup.

"When you've done staring," said his daughter, "you can go upstairs and make yourself tidy."

"Tidy?" repeated Mr. Vickers. "What for?"

"I'm going to see those three," replied Selina, grimly; "and I want a witness. And I may as well have a clean one while I'm about it."

Mr. Vickers darted upstairs with alacrity, and having made himself approximately tidy smoked a morning pipe on the doorstep while his daughter got ready. An air of importance and dignity suitable to the occasion partly kept off inquirers.

"We'll go and see Mr. Stobell first," said his daughter, as she came out.

"Very good," said the witness, "but if you asked my advice——"

"You just keep quiet," said Selina, irritably; "I've not gone quite off my head yet. And don't hum!"

Mr. Vickers lapsed into offended silence, and, arrived at Mr. Stobell's, followed his daughter into the hall in so stately a fashion that the maid—lately of Mint Street—implored him not to eat her. Miss Vickers replied for him, and the altercation that ensued was only quelled by the appearance of Mr. Stobell at the dining-room door.

"Halloa! What do you want?" he inquired, staring at the intruders.

"I've come for my share," said Miss Vickers, eyeing him fiercely.

"Share?" repeated Mr. Stobell. "Share? Why, we've been shipwrecked. Haven't you heard?"

"Perhaps you came to my house when I wasn't at home," retorted Miss Vickers, in a trembling but sarcastic voice. "I want to hear about it. That's what I've come for."

She walked to the dining-room and, as Mr. Stobell still stood in the doorway, pushed past him, followed by her father. Mr. Stobell, after a short deliberation, returned to his seat at the breakfast-table, and in an angry and disjointed fashion narrated the fate of the Fair Emily and their subsequent adventures. Miss Vickers heard him to an end in silence.

"What time was it when the ship struck on the rock?" she inquired.

Mr. Stobell stared at her. "Eleven o'clock," he said, gruffly.

Miss Vickers made a note in a little red-covered memorandum-book.

"Who got in the boat first?" she demanded.

Mr. Stobell's lips twisted in a faint grin. "Chalk did," he said, with relish.

Miss Vickers, nodding at the witness to call his attention to the fact, made another note.

"How far was the boat off when the ship sank?"

"Here, look here—" began the indignant Stobell.

"How far was the boat off?" interposed the witness, severely; "that's what we want to know."

"You hold your tongue," said his daughter.

"I'm doing the talking. How far was the boat off?"

"About four yards," replied Mr. Stobell. "And now look here; if you want to know any more, you go and see Mr. Chalk. I'm sick and tired of the whole business. And you'd no right to talk about it while we were away."

"I've got the paper you signed and I'm going to know the truth," said Miss Vickers, fiercely. "It's my right. What was the size of the island?"

Mr. Stobell maintained an obstinate silence.

"What colour did you say these 'ere Fidgetty islanders was?" inquired Mr. Vickers, with truculent curiosity.

"You get out," roared Stobell, rising. "At once. D'ye hear me?"

Mr. Vickers backed with some haste towards the door. His daughter followed slowly.

"I don't believe you," she said, turning sharply on Stobell. "I don't believe the ship was wrecked at all."

Mr. Stobell sat gasping at her. "What?" he stammered. "W h-a-a-t?"

"I don't believe it was wrecked," repeated Selina, wildly. "You've got the treasure all right, and you're keeping it quiet and telling this tale to do me out of my share. I haven't done with you yet. You wait!"

She flung out into the hall, and Mr. Vickers, after a lofty glance at Mr. Stobell, followed her outside.

"And now we'll go and hear what Mr. Tredgold has to say," she said, as they walked up the road. "And after that, Mr. Chalk."

Mr. Tredgold was just starting for the office when they arrived, but, recognising the justice of Miss Vickers's request for news, he stopped and gave his version of the loss of the Fair Emily. In several details it differed from that of Mr. Stobell, and he looked at her uneasily as she took out pencil and paper and made notes.

"If you want any further particulars you had better go and see Mr. Stobell," he said, restlessly. "I am busy."

"We've just been to see him," replied Miss Vickers, with an ominous gleam in her eye. "You say that the boat was two or three hundred yards away when the ship sank?"

"More or less," was the cautious reply.

"Mr. Stobell said about half a mile," suggested the wily Selina.

"Well, perhaps that would be more correct," said the other.

"Half a mile, then?"

"Half a mile," said Mr. Tredgold, nodding, as she wrote it down.

"Four yards was what Mr. Stobell said," exclaimed Selina, excitedly. "I've got it down here, and father heard it. And you make the time it happened and a lot of other things different. I don't believe that you were any more shipwrecked than I was."

"Not so much," added the irrepressible Mr. Vickers.

Mr. Tredgold walked to the door. "I am busy," he said, curtly. "Good morning."

Miss Vickers passed him with head erect, and her small figure trembling with rage and determination. By the time she had cross-examined Mr. Chalk her wildest suspicions were confirmed. His account differed in several particulars from the others, and his alarm and confusion when taxed with the discrepancies were unmistakable.

Binchester rang with the story of her wrongs, and, being furnished with three different accounts of the same incident, seemed inclined to display a little pardonable curiosity. To satisfy this, intimates of the gentlemen most concerned were provided with an official version, which Miss Vickers discovered after a little research was compiled for the most part by adding all the statements together and dividing by three. She paid another round of visits to tax them with the fact, and, strong in the justice of her cause, even followed them in the street demanding her money.

"There's one comfort," she said to the depressed Mr. Tasker. "I've got you, Joseph. They can't take you away from me."

"There's nobody could do that," responded Mr. Tasker, with a sigh of resignation.

"And if I had to choose," continued Miss Vickers, putting her arm round his waist, "I'd sooner have you than a hundred thousand pounds."

Mr. Tasker sighed again at the idea of an article estimated at so high a figure passing into the possession of Selina Vickers. In a voice broken with emotion he urged her to persevere in her claims to a fortune which he felt would alone make his fate tolerable. The unsuspecting Selina promised.

"She'll quiet down in time," said Captain Bowers to Mr. Chalk, after the latter had been followed nearly all the way to Dialstone Lane by Miss Vickers, airing her grievance and calling upon him to remedy it. "Once she realizes the fact that the ship is lost, she'll be all right."

Mr. Chalk looked unconvinced. "She doesn't want to realize it," he said, shaking his head.

"She'll be all right in time," repeated the captain; "and after all, you know," he added, with gentle severity, "you deserve to suffer a little. You had no business with that map."

On a fine afternoon towards the end of the following month Captain Brisket and Mr. Duckett sat outside the Swan and Bottle Inn, Holemouth, a small port forty miles distant from Biddlecombe. The day was fine, with just a touch of crispness in the air to indicate the waning of the year, and, despite a position regarded by the gloomy Mr. Duckett as teeming with perils, the captain turned a bright and confident eye on the Fair Emily, anchored in the harbour.

"We ought to have gone straight to Biddlecombe," said Mr. Duckett, following his glance; "it would have looked better. Not that anything'll make much difference."

"And everybody in a flutter of excitement telegraphing off to the owners," commented the captain. "No, we'll tell our story first; quiet and comfortable-like. Say it over again."

"I've said it three times," objected Mr. Duckett; "and each time it sounds more unreal than ever."

"It'll be all right," said Brisket, puffing at his cigar. "Besides, we've got no choice. It's that or ruin, and there's nobody within thousands of miles to contradict us. We bring both the ship and the map back to 'em. What more can they ask?"

"You'll soon know," said the pessimistic Mr. Duckett. "I wonder whether they'll have another shot for the treasure when they get that map back?" "I should like to send that Captain Bowers out searching for it," said Brisket, scowling, "and keep him out there till he finds it. It's all his fault. If it hadn't been for his cock-and-bull story we shouldn't ha' done what we did. Hanging's too good for him."

"I suppose it's best for them not to know that there's no such island?" hazarded Mr. Duckett.

"O' course," snapped his companion. "Looks better for us, don't it, giving them back a map worth half a million. Now go through the yarn again and I'll see whether I can pick any holes in it. The train goes in half an hour."

Mr. Duckett sighed and, first emptying his mug, began a monotonous recital. Brisket listened attentively.

"We were down below asleep when the men came running down and overpowered us. They weighed anchor at night, and following morning made you, by threats, promise to steer them to the island. You told me on the quiet that you'd die before you betrayed the owners' trust. How did they know that the island the gentlemen were on wasn't the right one? Because Sam Betts was standing by when you told me you'd made a mistake in your reckoning and said we'd better go ashore and tell them."

"That's all right so far, I think," said Brisket, nodding.

"We sailed about and tried island after island just to satisfy the men and seize our opportunity," continued Mr. Duckett, with a weary air. "At last, one day, when they were all drunk ashore, we took the map, shipped these natives, and sailed back to the island to rescue the owners. Found they'd gone when we got there. Mr. Stobell's boot and an old pair of braces produced in proof."

"Better wrap it up in a piece o' newspaper," said Brisket, stooping and producing the relic in question from under the table.

"Shipped four white men at Viti Levu and sailed for home," continued Mr. Duckett. "Could have had more, but wanted to save owners' pockets, and worked like A.B.'s ourselves to do so."

"Let'em upset that if they can," said Brisket, with a confident smile. "The crew are scattered, and if they happened to get one of them it's only his word against ours. Wait a bit. How did the crew know of the treasure?"

"Chalk told you," responded the obedient Duckett. "And if he told you —and he can't deny it—why not them?"

Captain Briskett nodded approval. "It's all right as far as I can see," he said, cautiously. "But mind. Leave the telling of it to me. You can just chip in with little bits here and there. Now let's get under way."

He threw away the stump of his cigar and rose, turning as he reached the corner for a lingering glance at the Fair Emily.

"Scrape her and clean her and she'd be as good as ever," he said, with a sigh. "She's just the sort o' little craft you and me could ha' done with, Peter."

They had to change twice on the way to Binchester, and at each stopping-place Mr. Duckett, a prey to nervousness, suggested the wisdom of disappearing while they had the opportunity.

"Disappear and starve, I suppose?" grunted the scornful Brisket. "What about my certificate? and yours, too? I tell you it's our only chance."

He walked up the path to Mr. Chalk's house with a swagger which the mate endeavoured in vain to imitate. Mr. Chalk was out, but the captain, learning that he was probably to be found at Dialstone Lane, decided to follow him there rather than first take his tidings to Stobell or Tredgold. With the idea of putting Mr. Duckett at his ease he talked on various matters as they walked, and, arrived at Dialstone Lane, even stopped to point out the picturesque appearance its old houses made in the moonlight.

"This is where the old pirate who made the map lives," he whispered, as he reached the door. "If he's got anything to say I'll tackle him about that. Now, pull yourself together!"

He knocked loudly on the door with his fist. A murmur of voices stopped suddenly, and, in response to a gruff command from within, he opened the door and stood staring at all three of his victims, who were seated at the table playing whist with Captain Bowers.

The three gentlemen stared back in return. Tredgold and Chalk had half risen from their seats; Mr. Stobell, with both arms on the table, leaned forward, and regarded him open-mouthed.

"Good evening, gentlemen all," said Captain Brisket, in a hearty voice.

He stepped forward, and seizing Mr. Chalk's hand wrung it fervently.

"It's good for sore eyes to see you again, sir," he said. "Look at him, Peter!"

Mr. Duckett, ignoring this reflection on his personal appearance, stepped quietly inside the door, and stood smiling nervously at the company.

"It's him," said the staring Mr. Stobell, drawing a deep breath. "It's Brisket."

He pushed his chair back and, rising slowly from the table, confronted him. Captain Brisket, red-faced and confident, stared up at him composedly.

"It's Brisket," said Mr. Stobell again, in a voice of deep content. "Turn the key in that door, Chalk."

Mr. Chalk hesitated, but Brisket, stepping to the door, turned the key and, placing it on the table, returned to his place by the side of the mate. Except for a hard glint in his eye his face still retained its smiling composure.

"And now," said Stobell, "you and me have got a word or two to say to each other. I haven't had the pleasure of seeing your ugly face since—"

"Since the disaster," interrupted Tredgold, loudly and hastily.

"Since the——"

Mr. Stobell suddenly remembered. For a few moments he stood irresolute, and then, with an extraordinary contortion of visage, dropped into his chair again and sat gazing blankly before him.

"Me and Peter Duckett only landed to-day," said Brisket, "and we came on to see you by the first train we could—"

"I know," said Tredgold, starting up and taking his hand, "and we're delighted to see you are safe. And Mr. Duckett?—"

He found Mr. Duckett's hand after a little trouble—the owner seeming to think that he wanted it for some unlawful purpose—and shook that. Captain Brisket, considerably taken aback by this performance, gazed at him with suspicion.

"You didn't go down with your ship, then, after all," said Captain Bowers, who had been looking on with much interest.

Amazement held Brisket dumb. He turned and eyed Duckett inquiringly. Then Tredgold, with his back to the others, caught his eye and frowned significantly.

"If Captain Brisket didn't go down with it I am sure that he was the last man to leave it," he said, kindly; "and Mr. Duckett last but one."

Mr. Duckett, distrustful of these compliments, cast an agonized glance at the door.

"Stobell was a bit rough just now," said Tredgold, with another warning glance at Brisket, "but he didn't like being shipwrecked."

Brisket gazed at the door in his turn. He had an uncomfortable feeling that he was being played with.

"It's nothing much to like," he said, at last, but—"

"Tell us how you escaped," said Tredgold; "or, perhaps," he continued, hastily, as Brisket was about to speak—"perhaps you would like first to hear how we did."

"Perhaps that would be better," said the perplexed Brisket.

He nudged the mate with his elbow, and Mr. Tredgold, still keeping him under the spell of his eye, began with great rapidity to narrate the circumstances attending the loss of the Fair Emily. After one irrepressible grunt of surprise Captain Brisket listened without moving a muscle, but the changes on Mr. Duckett's face were so extraordinary that on several occasions the narrator faltered and lost the thread of his discourse. At such times Mr. Chalk took up the story, and once, when both seemed at a loss, a growling contribution came from Mr. Stobell.

"Of course, you got away in the other boat," said Tredgold, nervously, when he had finished.

Brisket looked round shrewdly, his wits hard at work. Already the advantages of adopting a story which he supposed to have been concocted for the benefit of Captain Bowers were beginning to multiply in his ready brain.

"And didn't see us owing to the darkness," prompted Tredgold, with a glance at Mr. Joseph Tasker, who was lingering by the door after bringing in some whisky.

"You're quite right, sir," said Brisket, after a trying pause. "I didn't see you."

Unasked he took a chair, and with crossed legs and folded arms surveyed the company with a broad smile.

"You're a fine sort of shipmaster," exclaimed the indignant Captain Bowers. "First you throw away your ship, and then you let your passengers shift for themselves."

"I am responsible to my owners," said Brisket. "Have you any fault to find with me, gentlemen?" he demanded, turning on them with a frown.

Tredgold and Chalk hastened to reassure him.

"In the confusion the boat got adrift," said Brisket. "You've got their own word for it. Not that they didn't behave well for landsmen: Mr. Chalk's pluck was wonderful, and Mr. Tredgold was all right."

Mr. Stobell turned a dull but ferocious eye upon him.

"And you all got off in the other boat," said Tredgold. "I'm very glad."

Captain Brisket looked at him, but made no reply. The problem of how to make the best of the situation was occupying all his attention.

"Me and Peter Duckett would be glad of some of our pay," he said, at last.

"Pay?" repeated Tredgold, in a dazed voice.

Brisket looked at him again, and then gave a significant glance in the direction of Captain Bowers. "We'd like twenty pounds on account—now," he said, calmly.

Tredgold looked hastily at his friends. "Come and see me to-morrow," he said, nervously, "and we'll settle things."

"You can send us the rest," said Brisket, "but we want that now. We're off to-night."

"But we must see you again," said Tredgold, who was anxious to make arrangements about the schooner. "We—we've got a lot of things to talk about. The—the ship, for instance."

"I'll talk about her now if you want me to," said Brisket, with unpleasant readiness. "Meantime, we'd like that money."

Fortunately—or unfortunately—Tredgold had been to his bank that morning, and, turning a deaf ear to the expostulations of Captain Bowers, he produced his pocketbook, and after a consultation with Mr. Chalk, and an attempt at one with the raging Stobell, counted out the money and handed it over.

"And there is an I.O.U. for the remainder," he said, with an attempt at a smile, as he wrote on a slip of paper.

Brisket took it with pleased surprise, and the mate, leaning against his shoulder, read the contents: "Where is the 'Fair Emily'?"

"You might as well give me a receipt," said Tredgold, significantly, as he passed over pencil and paper.

Captain Brisket thanked him and, sucking the pencil, eyed him thoughtfully. Then he bent to the table and wrote.

"You sign here, Peter," he said.

Mr. Tredgold smiled at the precaution, but the smile faded when he took the paper. It was a correctly worded receipt for twenty pounds. He began to think that he had rated the captain's intelligence somewhat too highly.

"Ah, we've had a hard time of it," said Brisket, putting the notes into his breast-pocket and staring hard at Captain Bowers. "When that little craft went down, of course I went down with her. How I got up I don't know, but when I did there was Peter hanging over the side of the boat and pulling me in by the hair."

He paused to pat the mate on the shoulder.

"Unfortunately for us we took a different direction to you, sir," he continued, turning to Tredgold, "and we were pulling for six days before we were picked up by a barque bound for Melbourne. By the time she sighted us we were reduced to half a biscuit a day each and two teaspoonfuls o' water, and not a man grumbled. Did they, Peter?"

"Not a man," said Mr. Duckett.

"At Melbourne," said the captain, who was in a hurry to be off, "we all separated, and Duckett and me worked our way home on a cargo-boat. We always stick together, Peter and me."

"And always will," said Mr. Duckett, with a little emotion as he gazed meaningly at the captain's breast-pocket.

"When I think o' that little craft lying all those fathoms down," continued the captain, staring full at Mr. Tredgold, "it hurts me. The nicest little craft of her kind I ever handled. Well—so long, gentlemen."

"We shall see you to-morrow," said Tredgold, hastily, as the captain rose.

Brisket shook his head.

"Me and Peter are very busy," he said, softly. "We've been putting our little bit o' savings together to buy a schooner, and we want to settle things as soon as possible."

"A schooner?" exclaimed Mr. Tredgold, with an odd look.

Captain Brisket nodded indulgently.

"One o' the prettiest little craft you ever saw, gentlemen," he said," and, if you've got no objection, me and Peter Duckett thought o' calling her the Fair Emily, in memory of old times. Peter's a bit sentimental at times, but I don't know as I can blame him for it. Good night."

He opened the door slowly, and the sentimental Mr. Duckett, still holding fast to the parcel containing Mr. Stobell's old boot, slipped thankfully outside. Calmly and deliberately Captain Brisket followed, and the door was closing behind him when it suddenly stopped, and his red face was thrust into the room again.

"One thing is," he said, eyeing the speechless Tredgold with sly relish, "she's uncommonly like the Fair Emily we lost. Good night."

The door closed with a snap, but Tredgold and Chalk made no move. Glued to their seats, they stared blankly at the door, until the rigidity of their pose and the strangeness of their gaze began to affect the slower-witted Mr. Stobell.

"Anything wrong?" inquired the astonished Captain Bowers, looking from one to the other.

There was no reply. Mr. Stobell rose and, after steadying himself for a moment with his hands on the table, blundered heavily towards the door. As though magnetized, Tredgold and Chalk followed and, standing beside him on the footpath, stared solemnly up Dialstone Lane.

Captain Brisket and his faithful mate had disappeared.