DIALSTONE LANE

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I

Mr. Edward Tredgold sat in the private office of Tredgold and Son, land and estate agents, gazing through the prim wire blinds at the peaceful High Street of Binchester. Tredgold senior, who believed in work for the young, had left early. Tredgold junior, glad at an opportunity of sharing his father’s views, had passed most of the work on to a clerk who had arrived in the world exactly three weeks after himself.

“Binchester gets duller and duller,” said Mr. Tredgold to himself, wearily. “Two skittish octogenarians, one gloomy baby, one gloomier nursemaid, and three dogs in the last five minutes. If it wasn’t for the dogs—Halloa!”

He put down his pen and, rising, looked over the top of the blind at a girl who was glancing from side to side of the road as though in search of an address.

“A visitor,” continued Mr. Tredgold, critically. “Girls like that only visit Binchester, and then take the first train back, never to return.”

The girl turned at that moment and, encountering the forehead and eyes, gazed at them until they sank slowly behind the protection of the blind.

“She’s coming here,” said Mr. Tredgold, watching through the wire. “Wants to see our time-table, I expect.”

He sat down at the table again, and taking up his pen took some papers from a pigeon-hole and eyed them with severe thoughtfulness.

“A lady to see you, sir,” said a clerk, opening the door.

Mr. Tredgold rose and placed a chair.

“I have called for the key of the cottage in Dialstone Lane,” said the girl, still standing. “My uncle, Captain Bowers, has not arrived yet, and I am told that you are the landlord.”

Mr. Tredgold bowed. “The next train is due at six,” he observed, with a glance at the time-table hanging on the wall; “I expect he’ll come by that. He was here on Monday seeing the last of the furniture in. Are you Miss Drewitt?”

“Yes,” said the girl. “If you’ll kindly give me the key, I can go in and wait for him.”

Mr. Tredgold took it from a drawer. “If you will allow me, I will go down with you,” he said, slowly; “the lock is rather awkward for anybody who doesn’t understand it.”

The girl murmured something about not troubling him.

“It’s no trouble,” said Mr. Tredgold, taking up his hat. “It is our duty to do all we can for the comfort of our tenants. That lock—”

He held the door open and followed her into the street, pointing out various objects of interest as they went along.

“I’m afraid you’ll find Binchester very quiet,” he remarked.

“I like quiet,” said his companion.

Mr. Tredgold glanced at her shrewdly, and, pausing only at the jubilee horse-trough to point out beauties which might easily escape any but a trained observation, walked on in silence until they reached their destination.

Except in the matter of window-blinds, Dialstone Lane had not changed for generations, and Mr. Tredgold noted with pleasure the interest of his companion as she gazed at the crumbling roofs, the red-brick doorsteps, and the tiny lattice windows of the cottages. At the last house, a cottage larger than the rest, one side of which bordered the old churchyard, Mr. Tredgold paused and, inserting his key in the lock, turned it with thoughtless ease.

“The lock seems all right; I need not have bothered you,” said Miss Drewitt, regarding him gravely.

“Ah, it seems easy,” said Mr. Tredgold, shaking his head, “but it wants knack.”

The girl closed the door smartly, and, turning the key, opened it again without any difficulty. To satisfy herself—on more points than one—she repeated the performance.

“You’ve got the knack,” said Mr. Tredgold, meeting her gaze with great calmness. “It’s extraordinary what a lot of character there is in locks; they let some people open them without any trouble, while others may fumble at them till they’re tired.”

The girl pushed the door open and stood just inside the room.

“Thank you,” she said, and gave him a little bow of dismissal.

A vein of obstinacy in Mr. Tredgold’s disposition, which its owner mistook for firmness, asserted itself. It was plain that the girl had estimated his services at their true value and was quite willing to apprise him of the fact. He tried the lock again, and with more bitterness than the occasion seemed to warrant said that somebody had been oiling it.

“I promised Captain Bowers to come in this afternoon and see that a few odd things had been done,” he added. “May I come in now?”

The girl withdrew into the room, and, seating herself in a large arm-chair by the fireplace, watched his inspection of door-knobs and window-fastenings with an air of grave amusement, which he found somewhat trying.

“Captain Bowers had the walls panelled and these lockers made to make the room look as much like a ship’s cabin as possible,” he said, pausing in his labours. “He was quite pleased to find the staircase opening out of the room—he calls it the companion-ladder. And he calls the kitchen the pantry, which led to a lot of confusion with the workmen. Did he tell you of the crow’s-nest in the garden?”

“No,” said the girl.

“It’s a fine piece of work,” said Mr. Tredgold.

He opened the door leading into the kitchen and stepped out into the garden. Miss Drewitt, after a moment’s hesitation, followed, and after one delighted glance at the trim old garden gazed curiously at a mast with a barrel fixed near the top, which stood at the end.

“There’s a fine view from up there,” said Mr. Tredgold. “With the captain’s glass one can see the sea distinctly. I spent nearly all last Friday afternoon up there, keeping an eye on things. Do you like the garden? Do you think these old creepers ought to be torn down from the house?”

“Certainly not,” said Miss Drewitt, with emphasis.

“Just what I said,” remarked Mr. Tredgold. “Captain Bowers wanted to have them pulled down, but I dissuaded him. I advised him to consult you first.”

“I don’t suppose he really intended to,” said the girl.

“He did,” said the other, grimly; “said they were untidy. How do you like the way the house is furnished?”

The girl gazed at him for a few moments before replying. “I like it very much,” she said, coldly.

“That’s right,” said Mr. Tredgold, with an air of relief. “You see, I advised the captain what to buy. I went with him to Tollminster and helped him choose. Your room gave me the most anxiety, I think.”

“My room?” said the girl, starting.

“It’s a dream in the best shades of pink and green,” said Mr. Tredgold, modestly. “Pink on the walls, and carpets and hangings green; three or four bits of old furniture—the captain objected, but I stood firm; and for pictures I had two or three little things out of an art journal framed.”

“Is furnishing part of your business?” inquired the girl, eyeing him in bewilderment.

“Business?” said the other. “Oh, no. I did it for amusement. I chose and the captain paid. It was a delightful experience. The sordid question of price was waived; for once expense was nothing to me. I wish you’d just step up to your room and see how you like it. It’s the one over the kitchen.”

Miss Drewitt hesitated, and then curiosity, combined with a cheerful idea of probably being able to disapprove of the lauded decorations, took her indoors and upstairs. In a few minutes she came down again.

“I suppose it’s all right,” she said, ungraciously, “but I don’t understand why you should have selected it.”

“I had to,” said Mr. Tredgold, confidentially. “I happened to go to Tollminster the same day as the captain and went into a shop with him. If you could only see the things he wanted to buy, you would understand.”

The girl was silent.

“The paper the captain selected for your room,” continued Mr. Tredgold, severely, “was decorated with branches of an unknown flowering shrub, on the top twig of which a humming-bird sat eating a dragonfly. A rough calculation showed me that every time you opened your eyes in the morning you would see fifty-seven humming-birds—all made in the same pattern—eating fifty-seven ditto dragon-flies. The captain said it was cheerful.”

“I have no doubt that my uncle’s selection would have satisfied me,” said Miss Drewitt, coldly.

“The curtains he fancied were red, with small yellow tigers crouching all over them,” pursued Mr. Tredgold. “The captain seemed fond of animals.”

“I think that you were rather—venturesome,” said the girl. “Suppose that I had not liked the things you selected?”

Mr. Tredgold deliberated. “I felt sure that you would like them,” he said, at last. “It was a hard struggle not to keep some of the things for myself. I’ve had my eye on those two Chippendale chairs for years. They belonged to an old woman in Mint Street, but she always refused to part with them. I shouldn’t have got them, only one of them let her down the other day.”

“Let her down?” repeated Miss Drewitt, sharply. “Do you mean one of the chairs in my bedroom?”

Mr. Tredgold nodded. “Gave her rather a nasty fall,” he said. “I struck while the iron was hot, and went and made her an offer while she was still laid up from the effects of it. It’s the one standing against the wall; the other’s all right, with proper care.”

Miss Drewitt, after a somewhat long interval, thanked him.

“You must have been very useful to my uncle,” she said, slowly. “I feel sure that he would never have bought chairs like those of his own accord.”

“He has been at sea all his life,” said Mr. Tredgold, in extenuation. “You haven’t seen him for a long time, have you?”

“Ten years,” was the reply.

“He is delightful company,” said Mr. Tredgold. “His life has been one long series of adventures in every quarter of the globe. His stock of yarns is like the widow’s cruse. And here he comes,” he added, as a dilapidated fly drew up at the house and an elderly man, with a red, weatherbeaten face, partly hidden in a cloud of grey beard, stepped out and stood in the doorway, regarding the girl with something almost akin to embarrassment.

“It’s not—not Prudence?” he said at length, holding out his hand and staring at her.

“Yes, uncle,” said the girl.

They shook hands, and Captain Bowers, reaching up for a cage containing a parrot, which had been noisily entreating the cabman for a kiss all the way from the station, handed that flustered person his fare and entered the house again.

“Glad to see you, my lad,” he said, shaking hands with Mr. Tredgold and glancing covertly at his niece. “I hope you haven’t been waiting long,” he added, turning to the latter.

“No,” said Miss Drewitt, regarding him with a puzzled air.

“I missed the train,” said the captain. “We must try and manage better next time. I—I hope you’ll be comfortable.”

“Thank you,” said the girl.

“You—you are very like your poor mother,” said the captain.

“I hope so,” said Prudence.

She stole up to the captain and, after a moment’s hesitation, kissed his cheek. The next moment she was caught up and crushed in the arms of a powerful and affectionate bear.

“Blest if I hardly knew how to take you at first,” said the captain, his red face shining with gratification. “Little girls are one thing, but when they grow up into”—he held her away and looked at her proudly—“into handsome and dignified-looking young women, a man doesn’t quite know where he is.” He took her in his arms again and, kissing her forehead, winked delightedly in the direction of Mr. Tredgold, who was affecting to look out of the window.

“My man’ll be in soon,” he said, releasing the girl, “and then we’ll see about some tea. He met me at the station and I sent him straight off for things to eat.”

“Your man?” said Miss Drewitt.

“Yes; I thought a man would be easier to manage than a girl,” said the captain, knowingly. “You can be freer with ’em in the matter of language, and then there’s no followers or anything of that kind. I got him to sign articles ship-shape and proper. Mr. Tredgold recommended him.”

“No, no,” said that gentleman, hastily.

“I asked you before he signed on with me,” said the captain, pointing a stumpy forefinger at him. “I made a point of it, and you told me that you had never heard anything against him.”

“I don’t call that a recommendation,” said Mr. Tredgold.

“It’s good enough in these days,” retorted the captain, gloomily. “A man that has got a character like that is hard to find.”

“He might be artful and keep his faults to himself,” suggested Tredgold.

“So long as he does that, it’s all right,” said Captain Bowers. “I can’t find fault if there’s no faults to find fault with. The best steward I ever had, I found out afterwards, had escaped from gaol. He never wanted to go ashore, and when the ship was in port almost lived in his pantry.”

“I never heard of Tasker having been in gaol,” said Mr. Tredgold. “Anyhow, I’m certain that he never broke out of one; he’s far too stupid.”

As he paid this tribute the young man referred to entered laden with parcels, and, gazing awkwardly at the company, passed through the room on tiptoe and began to busy himself in the pantry. Mr. Tredgold, refusing the captain’s invitation to stay for a cup of tea, took his departure.

“Very nice youngster that,” said the captain, looking after him. “A little bit light-hearted in his ways, perhaps, but none the worse for that.”

He sat down and looked round at his possessions. “The first real home I’ve had for nearly fifty years,” he said, with great content. “I hope you’ll be as happy here as I intend to be. It sha’n’t be my fault if you’re not.”

Mr. Tredgold walked home deep in thought, and by the time he had arrived there had come to the conclusion that if Miss Drewitt favoured her mother, that lady must have been singularly unlike Captain Bowers in features.

CHAPTER II

In less than a week Captain Bowers had settled down comfortably in his new command. A set of rules and regulations by which Mr. Joseph Tasker was to order his life was framed and hung in the pantry. He studied it with care, and, anxious that there should be no possible chance of a misunderstanding, questioned the spelling in three instances. The captain’s explanation that he had spelt those words in the American style was an untruthful reflection upon a great and friendly nation.

Dialstone Lane was at first disposed to look askance at Mr. Tasker. Old-fashioned matrons clustered round to watch him cleaning the doorstep, and, surprised at its whiteness, withdrew discomfited. Rumour had it that he liked work, and scandal said that he had wept because he was not allowed to do the washing.

The captain attributed this satisfactory condition of affairs to the rules and regulations, though a slight indiscretion on the part of Mr. Tasker, necessitating the unframing of the document to add to the latter, caused him a little annoyance.

The first intimation he had of it was a loud knocking at the front door as he sat dozing one afternoon in his easy-chair. In response to his startled cry of “Come in!” the door opened and a small man, in a state of considerable agitation, burst into the room and confronted him.

“My name is Chalk,” he said, breathlessly.

“A friend of Mr. Tredgold’s?” said the captain. “I’ve heard of you, sir.”

The visitor paid no heed.

“My wife wishes to know whether she has got to dress in the dark every afternoon for the rest of her life,” he said, in fierce but trembling tones.

“Got to dress in the dark?” repeated the astonished captain.

“With the blind down,” explained the other.

Captain Bowers looked him up and down. He saw a man of about fifty nervously fingering the little bits of fluffy red whisker which grew at the sides of his face, and trying to still the agitation of his tremulous mouth.

“How would you like it yourself?” demanded the visitor, whose manner was gradually becoming milder and milder. “How would you like a telescope a yard long pointing—”

He broke off abruptly as the captain, with a smothered oath, dashed out of his chair into the garden and stood shaking his fist at the crow’s-nest at the bottom.

“Joseph!” he bawled.

“Yes, sir,” said Mr. Tasker, removing the telescope described by Mr. Chalk from his eye, and leaning over.

“What are you doing with that spy-glass?” demanded his master, beckoning to the visitor, who had drawn near. “How dare you stare in at people’s windows?”

“I wasn’t, sir,” replied Mr. Tasker, in an injured voice. “I wouldn’t think o’ such a thing—I couldn’t, not if I tried.”

“You’d got it pointed straight at my bedroom window,” cried Mr. Chalk, as he accompanied the captain down the garden. “And it ain’t the first time.”

“I wasn’t, sir,” said the steward, addressing his master. “I was watching the martins under the eaves.”

“You’d got it pointed at my window,” persisted the visitor.

“That’s where the nests are,” said Mr. Tasker, “but I wasn’t looking in at the window. Besides, I noticed you always pulled the blind down when you saw me looking, so I thought it didn’t matter.”

“We can’t do anything without being followed about by that telescope,” said Mr. Chalk, turning to the captain. “My wife had our house built where it is on purpose, so that we shouldn’t be overlooked. We didn’t bargain for a thing like that sprouting up in a back-garden.”

“I’m very sorry,” said the captain. “I wish you’d told me of it before. If I catch you up there again,” he cried, shaking his fist at Mr. Tasker, “you’ll remember it. Come down!”

Mr. Tasker, placing the glass under his arm, came slowly and reluctantly down the ratlines.

“I wasn’t looking in at the window, Mr. Chalk,” he said, earnestly. “I was watching the birds. O’ course, I couldn’t help seeing in a bit, but I always shifted the spy-glass at once if there was anything that I thought I oughtn’t—”

“That’ll do,” broke in the captain, hastily. “Go in and get the tea ready. If I so much as see you looking at that glass again we part, my lad, mind that.”

“I don’t suppose he meant any harm,” said the mollified Mr. Chalk, after the crestfallen Joseph had gone into the house. “I hope I haven’t been and said too much, but my wife insisted on me coming round and speaking about it.”

“You did quite right,” said the captain, “and I thank you for coming. I told him he might go up there occasionally, but I particularly warned him against giving any annoyance to the neighbours.”

“I suppose,” said Mr. Chalk, gazing at the erection with interest—“I suppose there’s a good view from up there? It’s like having a ship in the garden, and it seems to remind you of the North Pole, and whales, and Northern Lights.”

Five minutes later Mr. Tasker, peering through the pantry window, was surprised to see Mr. Chalk ascending with infinite caution to the crow’s-nest. His high hat was jammed firmly over his brows and the telescope was gripped tightly under his right arm. The journey was evidently regarded as one of extreme peril by the climber; but he held on gallantly and, arrived at the top, turned a tremulous telescope on to the horizon.

Mr. Tasker took a deep breath and resumed his labours. He set the table, and when the water boiled made the tea, and went down the garden to announce the fact. Mr. Chalk was still up aloft, and even at that height the pallor of his face was clearly discernible. It was evident to the couple below that the terrors of the descent were too much for him, but that he was too proud to say so.

“Nice view up there,” called the captain.

“B—b—beautiful,” cried Mr. Chalk, with an attempt at enthusiasm.

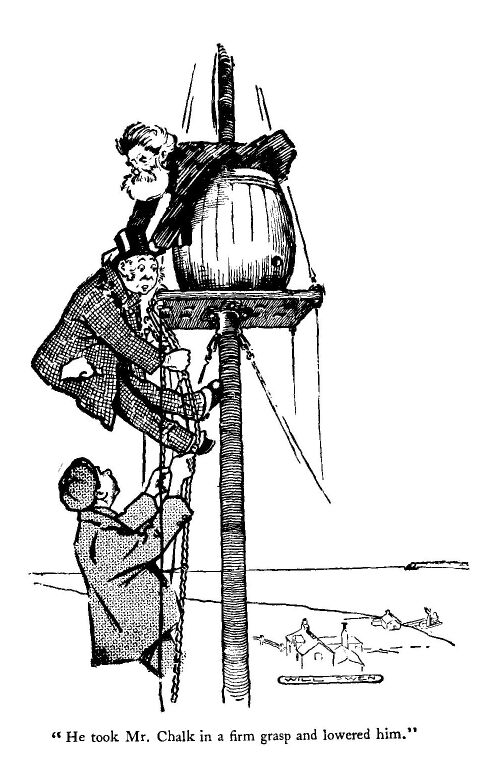

The captain paced up and down impatiently; his tea was getting cold, but the forlorn figure aloft made no sign. The captain waited a little longer, and then, laying hold of the shrouds, slowly mounted until his head was above the platform.

“Shall I take the glass for you?” he inquired.

Mr. Chalk, clutching the edge of the cask, leaned over and handed it down.

“My—my foot’s gone to sleep,” he stammered.

“Ho! Well, you must be careful how you get down,” said the captain, climbing on to the platform. “Now, gently.”

He put the telescope back into the cask, and, beckoning Mr. Tasker to ascend, took Mr. Chalk in a firm grasp and lowered him until he was able to reach Mr. Tasker’s face with his foot. After that the descent was easy, and Mr. Chalk, reaching ground once more, spent two or three minutes in slapping and rubbing, and other remedies prescribed for sleepy feet.

“There’s few gentlemen that would have come down at all with their foot asleep,” remarked Mr. Tasker, pocketing a shilling, when the captain’s back was turned.

Mr. Chalk, still pale and shaking somewhat, smiled feebly and followed the captain into the house. The latter offered a cup of tea, which the visitor, after a faint protest, accepted, and taking a seat at the table gazed in undisguised admiration at the nautical appearance of the room.

“I could fancy myself aboard ship,” he declared.

“Are you fond of the sea?” inquired the captain.

“I love it,” said Mr. Chalk, fervently. “It was always my idea from a boy to go to sea, but somehow I didn’t. I went into my father’s business instead, but I never liked it. Some people are fond of a stay-at-home life, but I always had a hankering after adventures.”

The captain shook his head. “Ha!” he said, impressively.

“You’ve had a few in your time,” said Mr. Chalk, looking at him, grudgingly; “Edward Tredgold was telling me so.”

“Man and boy, I was at sea forty-nine years,” remarked the captain. “Naturally things happened in that time; it would have been odd if they hadn’t. It’s all in a lifetime.”

“Some lifetimes,” said Mr. Chalk, gloomily. “I’m fifty-one next year, and the only thing I ever had happen to me was seeing a man stop a runaway horse and cart.”

He shook his head solemnly over his monotonous career, and, gazing at a war-club from Samoa which hung over the fireplace, put a few leading questions to the captain concerning the manner in which it came into his possession. When Prudence came in half an hour later he was still sitting there, listening with rapt attention to his host’s tales of distant seas.

It was the first of many visits. Sometimes he brought Mr. Tredgold and sometimes Mr. Tredgold brought him. The terrors of the crow’s-nest vanished before his persevering attacks, and perched there with the captain’s glass he swept the landscape with the air of an explorer surveying a strange and hostile country.

It was a fitting prelude to the captain’s tales afterwards, and Mr. Chalk, with the stem of his long pipe withdrawn from his open mouth, would sit enthralled as his host narrated picturesque incidents of hairbreadth escapes, or, drawing his chair to the table, made rough maps for his listener’s clearer understanding. Sometimes the captain took him to palm-studded islands in the Southern Seas; sometimes to the ancient worlds of China and Japan. He became an expert in nautical terms. He walked in knots, and even ordered a new carpet in fathoms—after the shop-keeper had demonstrated, by means of his little boy’s arithmetic book, the difference between that measurement and a furlong.

“I’ll have a voyage before I’m much older,” he remarked one afternoon, as he sat in the captain’s sitting-room. “Since I retired from business time hangs very heavy sometimes. I’ve got a fancy for a small yacht, but I suppose I couldn’t go a long voyage in a small one?”

“Smaller the better,” said Edward Tredgold, who was sitting by the window watching Miss Drewitt sewing.

Mr. Chalk took his pipe from his mouth and eyed him inquiringly.

“Less to lose,” explained Mr. Tredgold, with a scarcely perceptible glance at the captain. “Look at the dangers you’d be dragging your craft into, Chalk; there would be no satisfying you with a quiet cruise in the Mediterranean.”

“I shouldn’t run into unnecessary danger,” said Mr. Chalk, seriously. “I’m a married man, and there’s my wife to think of. What would become of her if anything happened to me?”

“Why, you’ve got plenty of money to leave, haven’t you?” inquired Mr. Tredgold.

“I was thinking of her losing me,” replied Mr. Chalk, with a touch of acerbity.

“Oh, I didn’t think of that,” said the other. “Yes, to be sure.”

“Captain Bowers was telling me the other day of a woman who wore widow’s weeds for thirty-five years,” said Mr. Chalk, impressively. “And all the time her husband was married again and got a big family in Australia. There’s nothing in the world so faithful as a woman’s heart.”

“Well, if you’re lost on a cruise, I shall know where to look for you,” said Mr. Tredgold. “But I don’t think the captain ought to put such ideas into your head.”

Mr. Chalk looked bewildered. Then he scratched his left whisker with the stem of his churchwarden pipe and looked severely over at Mr. Tredgold.

“I don’t think you ought to talk that way before ladies,” he said, primly. “Of course, I know you’re only in joke, but there’s some people can’t see jokes as quick as others and they might get a wrong idea of you.”

“What part did you think of going to for your cruise?” interposed Captain Bowers.

“There’s nothing settled yet,” said Mr. Chalk; “it’s just an idea, that’s all. I was talking to your father the other day,” he added, turning to Mr. Tredgold; “just sounding him, so to speak.”

“You take him,” said that dutiful son, briskly. “It would do him a world of good; me, too.”

“He said he couldn’t afford either the time or the money,” said Mr. Chalk. “The thing to do would be to combine business with pleasure—to take a yacht and find a sunken galleon loaded with gold pieces. I’ve heard of such things being done.”

“I’ve heard of it,” said the captain, nodding.

“Bottom of the ocean must be paved with them in places,” said Mr. Tredgold, rising, and following Miss Drewitt, who had gone into the garden to plant seeds.

Mr. Chalk refilled his pipe and, accepting a match from the captain, smoked slowly. His gaze was fixed on the window, but instead of Dialstone Lane he saw tumbling blue seas and islets far away.

“That’s something you’ve never come across, I suppose, Captain Bowers?” he remarked at last.

“No,” said the other.

Mr. Chalk, with a vain attempt to conceal his disappointment, smoked on for some time in silence. The blue seas disappeared, and he saw instead the brass knocker of the house opposite.

“Nor any other kind of craft with treasure aboard, I suppose?” he suggested, at last.

The captain put his hands on his knees and stared at the floor. “No,” he said, slowly, “I can’t call to mind any craft; but it’s odd that you should have got on this subject with me.”

Mr. Chalk laid his pipe carefully on the table.

“Why?” he inquired.

“Well,” said the captain, with a short laugh, “it is odd, that’s all.”

Mr. Chalk fidgeted with the stem of his pipe. “You know of sunken treasure somewhere?” he said, eagerly.

The captain smiled and shook his head; the other watched him narrowly.

“You know of some treasure?” he said, with conviction.

“Not what you could call sunken,” said the captain, driven to bay.

Mr. Chalk’s pale-blue eyes opened to their fullest extent. “Ingots?” he queried.

The other shook his head. “It’s a secret,” he remarked; “we won’t talk about it.”

“Yes, of course, naturally, I don’t expect you to tell me where it is,” said Mr. Chalk, “but I thought it might be interesting to hear about, that’s all.”

“It’s buried,” said the captain, after a long pause. “I don’t know that there’s any harm in telling you that; buried in a small island in the South Pacific.”

“Have you seen it?” inquired Mr. Chalk.

“I buried it,” rejoined the other.

Mr. Chalk sank back in his chair and regarded him with awestruck attention; Captain Bowers, slowly ramming home a charge of tobacco with his thumb, smiled quietly.

“Buried it,” he repeated, musingly, “with the blade of an oar for a spade. It was a long job, but it’s six foot down and the dead man it belonged to atop of it.”

The pipe fell from the listener’s fingers and smashed unheeded on the floor.

“You ought to make a book of it,” he said at last.

The captain shook his head. “I haven’t got the gift of story-telling,” he said, simply. “Besides, you can understand I don’t want it noised about. People might bother me.”

He leaned back in his chair and bunched his beard in his hand; the other, watching him closely, saw that his thoughts were busy with some scene in his stirring past.

“Not a friend of yours, I hope?” said Mr. Chalk, at last.

“Who?” inquired the captain, starting from his reverie.

“The dead man atop of the treasure,” replied the other.

“No,” said the captain, briefly.

“Is it worth much?” asked Mr. Chalk.

“Roughly speaking, about half a million,” responded the captain, calmly.

Mr. Chalk rose and walked up and down the room. His eyes were bright and his face pinker than usual.

“Why don’t you get it?” he demanded, at last, pausing in front of his host.

“Why, it ain’t mine,” said the captain, staring. “D’ye think I’m a thief?”

Mr. Chalk stared in his turn. “But who does it belong to, then?” he inquired.

“I don’t know,” replied the captain. “All I know is, it isn’t mine, and that’s enough for me. Whether it was rightly come by I don’t know. There it is, and there it’ll stay till the crack of doom.”

“Don’t you know any of his relations or friends?” persisted the other.

“I know nothing of him except his name,” said the captain, “and I doubt if even that was his right one. Don Silvio he called himself—a Spaniard. It’s over ten years ago since it happened. My ship had been bought by a firm in Sydney, and while I was waiting out there I went for a little run on a schooner among the islands. This Don Silvio was aboard of her as a passenger. She went to pieces in a gale, and we were the only two saved. The others were washed overboard, but we got ashore in the boat, and I thought from the trouble he was taking over his bag that the danger had turned his brain.”

“Ah!” said the keenly interested Mr. Chalk.

“He was a sick man aboard ship,” continued the captain, “and I soon saw that he hadn’t saved his life for long. He saw it, too, and before he died he made me promise that the bag should be buried with him and never disturbed. After I’d promised, he opened the bag and showed me what was in it. It was full of precious stones—diamonds, rubies, and the like; some of them as large as birds’ eggs. I can see him now, propped up against the boat and playing with them in the sunlight. They blazed like stars. Half a million he put them at, or more.”

“What good could they be to him when he was dead?” inquired the listener.

Captain Bowers shook his head. “That was his business, not mine,” he replied. “It was nothing to do with me. When he died I dug a grave for him, as I told you, with a bit of a broken oar, and laid him and the bag together. A month afterwards I was taken off by a passing schooner and landed safe at Sydney.”

Mr. Chalk stopped, and mechanically picking up the pieces of his pipe placed them on the table.

“Suppose that you had heard afterwards that the things had been stolen?” he remarked.

“If I had, then I should have given information, I think,” said the other. “It all depends.”

“Ah! but how could you have found them again?” inquired Mr. Chalk, with the air of one propounding a poser.

“With my map,” said the captain, slowly. “Before I left I made a map of the island and got its position from the schooner that picked me up; but I never heard a word from that day to this.”

“Could you find them now?” said Mr. Chalk.

“Why not?” said the captain, with a short laugh. “The island hasn’t run away.”

He rose as he spoke and, tossing the fragments of his visitor’s pipe into the fireplace, invited him to take a turn in the garden. Mr. Chalk, after a feeble attempt to discuss the matter further, reluctantly obeyed.

CHAPTER III

Mr. Chalk, with his mind full of the story he had just heard, walked homewards like a man in a dream. The air was fragrant with spring and the scent of lilac revived memories almost forgotten. It took him back forty years, and showed him a small boy treading the same road, passing the same houses. Nothing had changed so much as the small boy himself; nothing had been so unlike the life he had pictured as the life he had led. Even the blamelessness of the latter yielded no comfort; it savoured of a lack of spirit.

His mind was still busy with the past when he reached home. Mrs. Chalk, a woman of imposing appearance, who was sitting by the window at needlework, looked up sharply at his entrance. Before she spoke he had a dim idea that she was excited about something.

“I’ve got her,” she said, triumphantly.

“Oh!” said Mr. Chalk.

“She didn’t want to come at first,” said Mrs. Chalk; “she’d half promised to go to Mrs. Morris. Mrs. Morris had heard of her through Harris, the grocer, and he only knew she was out of a place by accident. He—”

Her words fell on deaf ears. Mr. Chalk, gazing through the window, heard without comprehending a long account of the capture of a new housemaid, which, slightly altered as to name and place, would have passed muster as an exciting contest between a skilful angler and a particularly sulky salmon. Mrs. Chalk, noticing his inattention at last, pulled up sharply.

“You’re not listening!” she cried.

“Yes, I am; go on, my dear,” said Mr. Chalk.

“What did I say she left her last place for, then?” demanded the lady.

Mr. Chalk started. He had been conscious of his wife’s voice, and that was all. “You said you were not surprised at her leaving,” he replied, slowly; “the only wonder to you was that a decent girl should have stayed there so long.”

Mrs. Chalk started and bit her lip. “Yes,” she said, slowly. “Ye-es. Go on; anything else?”

“You said the house wanted cleaning from top to bottom,” said the painstaking Mr. Chalk.

“Go on,” said his wife, in a smothered voice. “What else did I say?”

“Said you pitied the husband,” continued Mr. Chalk, thoughtfully.

Mrs. Chalk rose suddenly and stood over him. Mr. Chalk tried desperately to collect his faculties.

“How dare you?” she gasped. “I’ve never said such things in my life. Never. And I said that she left because Mr. Wilson, her master, was dead and the family had gone to London. I’ve never been near the house; so how could I say such things?”

Mr. Chalk remained silent.

“What made you think of such things?” persisted Mrs. Chalk.

Mr. Chalk shook his head; no satisfactory reply was possible. “My thoughts were far away,” he said, at last.

His wife bridled and said, “Oh, indeed!” Mr. Chalk’s mother, dead some ten years before, had taken a strange pride—possibly as a protest against her only son’s appearance—in hinting darkly at a stormy and chequered past. Pressed for details she became more mysterious still, and, saying that “she knew what she knew,” declined to be deprived of the knowledge under any consideration. She also informed her daughter-in-law that “what the eye don’t see the heart don’t grieve,” and that it was better to “let bygones be bygones,” usually winding up with the advice to the younger woman to keep her eye on Mr. Chalk without letting him see it.

“Peckham Rye is a long way off, certainly,” added the indignant Mrs. Chalk, after a pause. “It’s a pity you haven’t got something better to think of, at your time of life, too.”

Mr. Chalk flushed. Peckham Rye was one of the nuisances bequeathed by his mother.

“I was thinking of the sea,” he said, loftily.

Mrs. Chalk pounced. “Oh, Yarmouth,” she said, with withering scorn.

Mr. Chalk flushed deeper than before. “I wasn’t thinking of such things,” he declared.

“What things?” said his wife, swiftly.

“The—the things you’re alluding to,” said the harassed Mr. Chalk.

“Ah!” said his wife, with a toss of her head. “Why you should get red in the face and confused when I say Peckham Rye and Yarmouth are a long way off is best known to yourself. It’s very funny that the moment either of these places is mentioned you get uncomfortable. People might read a geography-book out loud in my presence and it wouldn’t affect me.”

She swept out of the room, and Mr. Chalk’s thoughts, excited by the magic word geography, went back to the island again. The half-forgotten dreams of his youth appeared to be materializing. Sleepy Binchester ended for him at Dialstone Lane, and once inside the captain’s room the enchanted world beyond the seas was spread before his eager gaze. The captain, amused at first at his enthusiasm, began to get weary of the subject of the island, and so far the visitor had begged in vain for a glimpse of the map.

His enthusiasm became contagious. Prudence, entering one evening in the middle of a conversation, heard sufficient to induce her to ask for more, and the captain, not without some reluctance and several promptings from Mr. Chalk when he showed signs of omitting vital points, related the story. Edward Tredgold heard it, and, judging by the frequency of his visits, was almost as interested as Mr. Chalk.

“I can’t see that there could be any harm in just looking at the map,” said Mr. Chalk, one evening. “You could keep your thumb on any part you wanted to.”

“Then we should know where to dig,” urged Mr. Tredgold. “Properly managed there ought to be a fortune in your innocence, Chalk.”

Mr. Chalk eyed him fixedly. “Seeing that the latitude and longitude and all the directions are written on the back,” he observed, with cold dignity, “I don’t see the force of your remarks.”

“Well, in that case, why not show it to Mr. Chalk, uncle?” said Prudence, charitably.

Captain Bowers began to show signs of annoyance. “Well, my dear,” he began, slowly.

“Then Miss Drewitt could see it too,” said Mr. Tredgold, blandly.

Miss Drewitt reddened with indignation. “I could see it any time I wished,” she said, sharply.

“Well, wish now,” entreated Mr. Tredgold. “As a matter of fact, I’m dying with curiosity myself. Bring it out and make it crackle, captain; it’s a bank-note for half a million.”

The captain shook his head and a slight frown marred his usually amiable features. He got up and, turning his back on them, filled his pipe from a jar on the mantelpiece.

“You never will see it, Chalk,” said Edward Tredgold, in tones of much conviction. “I’ll bet you two to one in golden sovereigns that you’ll sink into your honoured family vault with your justifiable curiosity still unsatisfied. And I shouldn’t wonder if your perturbed spirit walks the captain’s bedroom afterwards.”

Miss Drewitt looked up and eyed the speaker with scornful comprehension. “Take the bet, Mr. Chalk,” she said, slowly.

Mr. Chalk turned in hopeful amaze; then he leaned over and shook hands solemnly with Mr. Tredgold. “I’ll take the bet,” he said.

“Uncle will show it to you to please me,” announced Prudence, in a clear voice. “Won’t you, uncle?”

The captain turned and took the matches from the table. “Certainly, my dear, if I can find it,” he said, in a hesitating fashion. “But I’m afraid I’ve mislaid it. I haven’t seen it since I unpacked.”

“Mislaid it!” ejaculated the startled Mr. Chalk. “Good heavens! Suppose somebody should find it? What about your word to Don Silvio then?”

“I’ve got it somewhere,” said the captain, brusquely; “I’ll have a hunt for it. All the same, I don’t know that it’s quite fair to interfere in a bet.”

Miss Drewitt waved the objection away, remarking that people who made bets must risk losing their money.

“I’ll begin to save up,” said Mr. Tredgold, with a lightness which was not lost upon Miss Drewitt. “The captain has got to find it before you can see it, Chalk.”

Mr. Chalk, with a satisfied smile, said that when the captain promised a thing it was as good as done.

For the next few days he waited patiently, and, ransacking an old lumber-room, divided his time pretty equally between a volume of “Captain Cook’s Voyages” that he found there and “Famous Shipwrecks.” By this means and the exercise of great self-control he ceased from troubling Dialstone Lane for a week. Even then it was Edward Tredgold who took him there. The latter was in high spirits, and in explanation informed the company, with a cheerful smile, that he had saved five and ninepence, and was forming habits which bade fair to make him a rich man in time.

“Don’t you be in too much of a hurry to find that map, captain,” he said.

“It’s found,” said Miss Drewitt, with a little note of triumph in her voice.

“Found it this morning,” said Captain Bowers. He crossed over to an oak bureau which stood in the corner by the fireplace, and taking a paper from a pigeon-hole slowly unfolded it and spread it on the table before the delighted Mr. Chalk. Miss Drewitt and Edward Tredgold advanced to the table and eyed it curiously.

The map, which was drawn in lead-pencil, was on a piece of ruled paper, yellow with age and cracked in the folds. The island was in shape a rough oval, the coast-line being broken by small bays and headlands. Mr. Chalk eyed it with all the fervour usually bestowed on a holy relic, and, breathlessly reading off such terms as “Cape Silvio,” “Bowers Bay,” and “Mount Lonesome,” gazed with breathless interest at the discoverer.

“And is that the grave?” he inquired, in a trembling voice, pointing to a mark in the north-east corner.

The captain removed it with his finger-nail. “No,” he said, briefly. “For full details see the other side.”

For one moment Mr. Chalk hoped; then his face fell as Captain Bowers, displaying for a fraction of a second the writing on the other side, took up the map and, replacing it in the bureau, turned the key in the lock and with a low laugh resumed his seat. Miss Drewitt, glancing over at Edward Tredgold, saw that he looked very thoughtful.

“You’ve lost your bet,” she said, pointedly.

“I know,” was the reply.

His gaiety had vanished and he looked so dejected that Miss Drewitt was reminded of the ruined gambler in a celebrated picture. She tried to quiet her conscience by hoping that it would be a lesson to him. As she watched, Mr. Tredgold dived into his left trouser-pocket and counted out some coins, mostly brown. To these he added a few small pieces of silver gleaned from his waistcoat, and then after a few seconds’ moody thought found a few more in the other trouser-pocket.

“Eleven and tenpence,” he said, mechanically.

“Any time,” said Mr. Chalk, regarding him with awkward surprise. “Any time.”

“Give him an I O U,” said Captain Bowers, fidgeting.

“Yes, any time,” repeated Mr. Chalk; “I’m in no hurry.”

“No; I’d sooner pay now and get it over,” said the other, still fumbling in his pockets. “As Miss Drewitt says, people who make bets must be prepared to lose; I thought I had more than this.”

There was an embarrassing silence, during which Miss Drewitt, who had turned very red, felt strangely uncomfortable. She felt more uncomfortable still when Mr. Tredgold, discovering a bank-note and a little collection of gold coins in another pocket, artlessly expressed his joy at the discovery. The simple-minded captain and Mr. Chalk both experienced a sense of relief; Miss Drewitt sat and simmered in helpless indignation.

“You’re careless in money matters, my lad,” said the captain, reprovingly.

“I couldn’t understand him making all that fuss over a couple o’ pounds,” said Mr. Chalk, looking round. “He’s very free, as a rule; too free.”

Mr. Tredgold, sitting grave and silent, made no reply to these charges, and the girl was the only one to notice a faint twitching at the corners of his mouth. She saw it distinctly, despite the fact that her clear, grey eyes were fixed dreamily on a spot some distance above his head.

She sat in her room upstairs after the visitors had gone, thinking it over. The light was fading fast, and as she sat at the open window the remembrance of Mr. Tredgold’s conduct helped to mar one of the most perfect evenings she had ever known.

Downstairs the captain was also thinking. Dialstone Lane was in shadow, and already one or two lamps were lit behind drawn blinds. A little chatter of voices at the end of the lane floated in at the open window, mellowed by distance. His pipe was out, and he rose to search in the gloom for a match, when another murmur of voices reached his ears from the kitchen. He stood still and listened intently. To put matters beyond all doubt, the shrill laugh of a girl was plainly audible. The captain’s face hardened, and, crossing to the fireplace, he rang the bell.

“Yessir,” said Joseph, as he appeared and closed the door carefully behind him.

“What are you talking to yourself in that absurd manner for?” inquired the captain with great dignity.

“Me, sir?” said Mr. Tasker, feebly.

“Yes, you,” repeated the captain, noticing with surprise that the door was slowly opening.

Mr. Tasker gazed at him in a troubled fashion, but made no reply.

“I won’t have it,” said the captain, sternly, with a side glance at the door. “If you want to talk to yourself go outside and do it. I never heard such a laugh. What did you do it for? It was like an old woman with a bad cold.”

He smiled grimly in the darkness, and then started slightly as a cough, a hostile, challenging cough, sounded from the kitchen. Before he could speak the cough ceased and a thin voice broke carelessly into song.

“What!” roared the captain, in well-feigned astonishment. “Do you mean to tell me you’ve got somebody in my pantry? Go and get me those rules and regulations.”

Mr. Tasker backed out, and the captain smiled again as he heard a whispered discussion. Then a voice clear and distinct took command. “I’ll take ’em in myself, I tell you,” it said. “I’ll rules and regulations him.”

The smile faded from the captain’s face, and he gazed in perplexity at the door as a strange young woman bounced into the room.

“Here’s your rules and regulations,” said the intruder, in a somewhat shrewish voice. “You’d better light the lamp if you want to see ’em; though the spelling ain’t so noticeable in the dark.”

The impressiveness of the captain’s gaze was wasted in the darkness. For a moment he hesitated, and then, with the dignity of a man whose spelling has nothing to conceal, struck a match and lit the lamp. The lamp lighted, he lowered the blind, and then seating himself by the window turned with a majestic air to a thin slip of a girl with tow-coloured hair, who stood by the door.

“Who are you?” he demanded, gruffly.

“My name’s Vickers,” said the young lady. “Selina Vickers. I heard all what you’ve been saying to my Joseph, but, thank goodness, I can take my own part. I don’t want nobody to fight my battles for me. If you’ve got anything to say about my voice you can say it to my face.”

Captain Bowers sat back and regarded her with impressive dignity. Miss Vickers met his gaze calmly and, with a pair of unwinking green eyes, stared him down.

“What were you doing in my pantry?” demanded the captain, at last.

“I was in your kitchen,” replied Miss Vickers, with scornful emphasis on the last word, “to see my young man.”

“Well, I can’t have you there,” said the captain, with a mildness that surprised himself. “One of my rules—”

Miss Vickers interposed. “I’ve read ’em all over and over again,” she said, impatiently.

“If it occurs again,” said the other, “I shall have to speak to Joseph very seriously about it.”

“Talk to me,” said Miss Vickers, sharply; “that’s what I come in for. I can talk to you better than what Joseph can, I know. What harm do you think I was doing your old kitchen? Don’t you try and interfere between me and my Joseph, because I won’t have it. You’re not married yourself, and you don’t want other people to be. How do you suppose the world would get on if everybody was like you?”

Captain Bowers regarded her in open-eyed perplexity. The door leading to the garden had just closed behind the valiant Joseph, and he stared with growing uneasiness at the slight figure of Miss Vickers as it stood poised for further oratorical efforts. Before he could speak she gave her lips a rapid lick and started again.

“You’re one of those people that don’t like to see others happy, that’s what you are,” she said, rapidly. “I wasn’t hurting your kitchen, and as to talking and laughing there—what do you think my tongue was given to me for? Show? P’r’aps if you’d been doing a day’s hard work you’d—”

“Look here, my girl—” began the captain, desperately.

“Don’t you my girl me, please,” interrupted Miss Vickers. “I’m not your girl, thank goodness. If I was you’d be a bit different, I can tell you. If you had any girls you’d know better than to try and come between them and their young men. Besides, they wouldn’t let you. When a girl’s got a young man—”

The captain rose and went through the form of ringing the bell. Miss Vickers watched him calmly.

“I thought I’d just have it out with you for once and for all,” she continued. “I told Joseph that I’d no doubt your bark was worse than your bite. And what he can see to be afraid of in you I can’t think. Nervous disposition, I s’pose. Good evening.”

She gave her head a little toss and, returning to the pantry, closed the door after her. Captain Bowers, still somewhat dazed, returned to his chair and, gazing at the “Rules,” which still lay on the table, grinned feebly in his beard.

CHAPTER IV

To keep such a romance to himself was beyond the powers of Mr. Chalk. The captain had made no conditions as to secrecy, and he therefore considered himself free to indulge in hints to his two greatest friends, which caused those gentlemen to entertain some doubts as to his sanity. Mr. Robert Stobell, whose work as a contractor had left a permanent and unmistakable mark upon Binchester, became imbued with a hazy idea that Mr. Chalk had invented a new process of making large diamonds. Mr. Jasper Tredgold, on the other hand, arrived at the conclusion that a highly respectable burglar was offering for some reason to share his loot with him. A conversation between Messrs. Stobell and Tredgold in the High Street only made matters more complicated.

“Chalk always was fond of making mysteries of things,” complained Mr. Tredgold.

Mr. Stobell, whose habit was taciturn and ruminative, fixed his dull brown eyes on the ground and thought it over. “I believe it’s all my eye and Betty Martin,” he said, at length, quoting a saying which had been used in his family as an expression of disbelief since the time of his great-grandmother.

“He comes in to see me when I’m hard at work and drops hints,” pursued his friend. “When I stop to pick ’em up, out he goes. Yesterday he came in and asked me what I thought of a man who wouldn’t break his word for half a million. Half a million, mind you! I just asked him who it was, and out he went again. He pops in and out of my office like a figure on a cuckoo-clock.”

Mr. Stobell relapsed into thought again, but no gleam of expression disturbed the lines of his heavy face; Mr. Tredgold, whose sharp, alert features bred more confidence in his own clients than those of other people, waited impatiently.

“He knows something that we don’t,” said Mr. Stobell, at last; “that’s what it is.”

Mr. Tredgold, who was too used to his friend’s mental processes to quarrel with them, assented.

“He’s coming round to smoke a pipe with me to-morrow night,” he said, briskly, as he turned to cross the road to his office. “You come too, and we’ll get it out of him. If Chalk can keep a secret he has altered, that’s all I can say.”

His estimate of Mr. Chalk proved correct. With Mr. Tredgold acting as cross-examining counsel and Mr. Stobell enacting the part of a partial and overbearing judge, Mr. Chalk, after a display of fortitude which surprised himself almost as much as it irritated his friends, parted with his news and sat smiling with gratification at their growing excitement.

“Half a million, and he won’t go for it?” ejaculated Mr. Tredgold. “The man must be mad.”

“No; he passed his word and he won’t break it,” said Mr. Chalk. “The captain’s word is his bond, and I honour him for it. I can quite understand it.”

Mr. Tredgold shrugged his shoulders and glanced at Mr. Stobell; that gentleman, after due deliberation, gave an assenting nod.

“He can’t get at it, that’s the long and short of it,” said Mr. Tredgold, after a pause. “He had to leave it behind when he was rescued, or else risk losing it by telling the men who rescued him about it, and he’s had no opportunity since. It wants money to take a ship out there and get it, and he doesn’t see his way quite clear. He’ll have it fast enough when he gets a chance. If not, why did he make that map?”

Mr. Chalk shook his head, and remarked mysteriously that the captain had his reasons. Mr. Tredgold relapsed into silence, and for some time the only sound audible came from a briar-pipe which Mr. Stobell ought to have thrown away some years before.

“Have you given up that idea of a yachting cruise of yours, Chalk?” demanded Mr. Tredgold, turning on him suddenly.

“No,” was the reply. “I was talking about it to Captain Bowers only the other day. That’s how I got to hear of the treasure.”

Mr. Tredgold started and gave a significant glance at Mr. Stobell. In return he got a wink which that gentleman kept for moments of mental confusion.

“What did the captain tell you for?” pursued Mr. Tredgold, returning to Mr. Chalk. “He wanted you to make an offer. He hasn’t got the money for such an expedition; you have. The yarn about passing his word was so that you shouldn’t open your mouth too wide. You were to do the persuading, and then he could make his own terms. Do you see? Why, it’s as plain as A B C.”

“Plain as the alphabet,” said Mr. Stobell, almost chidingly.

Mr. Chalk gasped and looked from one to the other.

“I should like to have a chat with the captain about it,” continued Mr. Tredgold, slowly and impressively. “I’m a business man and I could put it on a business footing. It’s a big risk, of course; all those things are . . . but if we went shares . . . if we found the money——”

He broke off and, filling his pipe slowly, gazed in deep thought at the wall. His friends waited expectantly.

“Combine business with pleasure,” resumed Mr. Tredgold, lighting his pipe; “sea-air . . . change . . . blow away the cobwebs . . . experience for Edward to be left alone. What do you think, Stobell?” he added, turning suddenly.

Mr. Stobell gripped the arms of his chair in his huge hands and drew his bulky figure to a more upright position.

“What do you mean by combining business with pleasure?” he said, eyeing him with dull suspicion.

“Chalk is set on a trip for the love of it,” explained Mr. Tredgold.

“If we take on the contract, he ought to pay a bigger share, then,” said the other, firmly.

“Perhaps he will,” said Tredgold, hastily.

Mr. Stobell pondered again and, slightly raising one hand, indicated that he was in the throes of another idea and did not wish to be disturbed.

“You said it would be experience for Edward to be left alone,” he said, accusingly.

“I did,” was the reply.

“You ought to pay more, too, then,” declared the contractor, “because it’s serving of your ends as well.”

“We can’t split straws,” exclaimed Tredgold, impatiently. “If the captain consents we three will find the money and divide our portion, whatever it is, equally.”

Mr. Chalk, who had been in the clouds during this discussion, came back to earth again. “If he consents,” he said, sadly; “but he won’t.”

“Well, he can only refuse,” said Mr. Tredgold; “and, anyway, we’ll have the first refusal. Things like that soon get about. What do you say to a stroll? I can think better while I’m walking.”

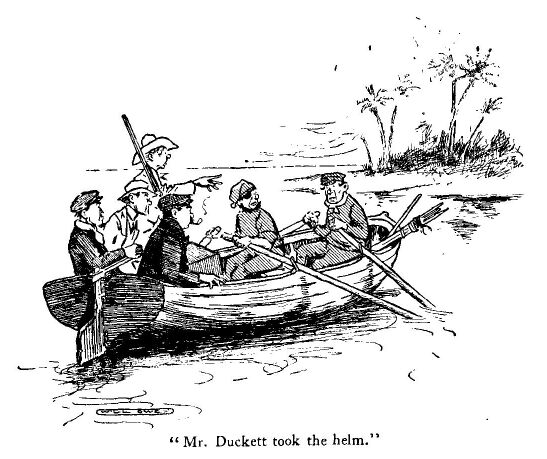

His friends assenting, they put on their hats and sallied forth. That they should stroll in the direction of Dialstone Lane surprised neither of them. Mr. Tredgold leading, they went round by the church, and that gentleman paused so long to admire the architecture that Mr. Stobell got restless.

“You’ve seen it before, Tredgold,” he said, shortly.

“It’s a fine old building,” said the other. “Binchester ought to be proud of it. Why, here we are at Captain Bowers’s!”

“The house has been next to the church for a couple o’ hundred years,” retorted his friend.

“Let’s go in,” said Mr. Tredgold. “Strike while the iron’s hot. At any rate,” he concluded, as Mr. Chalk voiced feeble objections, “we can see how the land lies.”

He knocked at the door and then, stepping aside, left Mr. Chalk to lead the way in. Captain Bowers, who was sitting with Prudence, looked up at their entrance, and putting down his newspaper extended a hearty welcome.

“Chalk didn’t like to pass without looking in,” said Mr. Tredgold, “and I haven’t seen you for some time. You know Stobell?”

The captain nodded, and Mr. Chalk, pale with excitement, accepted his accustomed pipe from the hands of Miss Drewitt and sat nervously awaiting events. Mr. Tasker set out the whisky, and, Miss Drewitt avowing a fondness for smoke in other people, a comfortable haze soon filled the room. Mr. Tredgold, with a significant glance at Mr. Chalk, said that it reminded him of a sea-fog.

It only reminded Mr. Chalk, however, of a smoky chimney from which he had once suffered, and he at once entered into minute details. The theme was an inspiriting one, and before Mr. Tredgold could hark back to the sea again Mr. Stobell was discoursing, almost eloquently for him, upon drains. From drains to the shortcomings of the district council they progressed by natural and easy stages, and it was not until Miss Drewitt had withdrawn to the clearer atmosphere above that a sudden ominous silence ensued, which Mr. Chalk saw clearly he was expected to break.

“I—I’ve been telling them some of your adventures,” he said, desperately, as he glanced at the captain; “they’re both interested in such things.”

The latter gave a slight start and glanced shrewdly at his visitors. “Aye, aye,” he said, composedly.

“Very interesting, some of them,” murmured Mr. Tredgold. “I suppose you’ll have another voyage or two before you’ve done? One, at any rate.”

“No,” said the captain, “I’ve had my share of the sea; other men may have a turn now. There’s nothing to take me out again—nothing.”

Mr. Tredgold coughed and murmured something about breaking off old habits too suddenly.

“It’s a fine career,” sighed Mr. Chalk.

“A manly life,” said Mr. Tredgold, emphatically.

“It’s like every other profession, it has two sides to it,” said the captain.

“It is not so well paid as it should be,” said the wily Tredgold, “but I suppose one gets chances of making money in outside ways sometimes.”

The captain assented, and told of a steward of his who had made a small fortune by selling Japanese curios to people who didn’t understand them.

The conversation was interesting, but extremely distasteful to a business man intent upon business. Mr. Stobell took his pipe out of his mouth and cleared his throat. “Why, you might build a hospital with it,” he burst out, impatiently.

“Build a hospital!” repeated the astonished captain, as Mr. Chalk bent suddenly to do up his shoelace.

“Think of the orphans you could be a father to!” added Mr. Stobell, making the most of an unwonted fit of altruism.

The captain looked inquiringly at Mr. Tredgold.

“And widows,” said Mr. Stobell, and, putting his pipe in his mouth as a sign that he had finished his remarks, gazed stolidly at the company.

“Stobell must be referring to a story Chalk told us of some precious stones you buried, I think,” said Mr. Tredgold, reddening. “Aren’t you, Stobell?”

“Of course I am,” said his friend. “You know that.”

Captain Bowers glanced at Mr. Chalk, but that gentleman was still busy with his shoe-lace, only looking up when Mr. Tredgold, taking the bull by the horns, made the captain a plain, straightforward offer to fit out and give him the command of an expedition to recover the treasure. In a speech which included the benevolent Mr. Stobell’s hospitals, widows, and orphans, he pointed out a score of reasons why the captain should consent, and wound up with a glowing picture of Miss Drewitt as the heiress of the wealthiest man in Binchester. The captain heard him patiently to an end and then shook his head.

“I passed my word,” he said, stiffly.

Mr. Stobell took his pipe out of his mouth again to offer a little encouragement. “Tredgold has broke his word before now,” he observed; “he’s got quite a name for it.”

“But you would go out if it were not for that?” inquired Tredgold, turning a deaf ear to this remark.

“Naturally,” said the captain, smiling; “but, then, you see I did.”

Mr. Tredgold drummed with his fingers on the arms of his chair, and after a little hesitation asked as a great favour to be permitted to see the map. As an estate agent, he said, he took a professional interest in plans of all kinds.

Captain Bowers rose, and in the midst of an expectant silence took the map from the bureau, and placing it on the table kept it down with his fist. The others drew near and inspected it.

“Nobody but Captain Bowers has ever seen the other side,” said Mr. Chalk, impressively.

“Except my niece,” interposed the captain. “She wanted to see it, and I trust her as I would trust myself. She thinks the same as I do about it.”

His stubby forefinger travelled slowly round the coast-line until, coming to the extreme south-west corner, it stopped, and a mischievous smile creased his beard.

“It’s buried here,” he observed. “All you’ve got to do is to find the island and dig in that spot.”

Mr. Chalk laughed and shook his head as at a choice piece of waggishness.

“Suppose,” said Mr. Tredgold, slowly—“suppose anybody found it without your connivance, would you take your share?”

“Let ’em find it first,” said the captain.

“Yes, but would you?” inquired Mr. Chalk.

Captain Bowers took up the map and returned it to its place in the bureau. “You go and find it,” he said, with a genial smile.

“You give us permission?” demanded Tredgold.

“Certainly,” grinned the captain. “I give you permission to go and dig over all the islands in the Pacific; there’s a goodish number of them, and it’s a fairly common shape.”

“It seems to me it’s nobody’s property,” said Tredgold, slowly. “That is to say, it’s anybody’s that finds it. It isn’t your property, Captain Bowers? You lay no claim to it?”

“No, no,” said the captain. “It’s nothing to do with me. You go and find it,” he repeated, with enjoyment.

Mr. Tredgold laughed too, and his eye travelled mechanically towards the bureau. “If we do,” he said, cordially, “you shall have your share.”

The captain thanked him and, taking up the bottle, refilled their glasses. Then, catching the dull, brooding eye of Mr. Stobell as that plain-spoken man sat in a brown study trying to separate the serious from the jocular, he drank success to their search. He was about to give vent to further pleasantries when he was stopped by the mysterious behaviour of Mr. Chalk, who, first laying a finger on his lip to ensure silence, frowned severely and nodded at the door leading to the kitchen.

The other three looked in the direction indicated. The door stood half open, and the silhouette of a young woman in a large hat put the upper panels in shadow. The captain rose and, with a vigorous thrust of his foot, closed the door with a bang.

“Eavesdropping,” said Mr. Chalk, in a tense whisper.

“There’ll be a rival expedition,” said the captain, falling in with his mood. “I’ve already warned that young woman off once. You’d better start tonight.”

He leaned back in his chair and surveyed the company pleasantly. Somewhat to Mr. Chalk’s disappointment Mr. Tredgold began to discuss agriculture, and they were still on that theme when they rose to depart some time later. Tredgold and Chalk bade the captain a cordial good-night; but Stobell, a creature of primitive impulses, found it difficult to shake hands with him. On the way home he expressed an ardent desire to tell the captain what men of sense thought of him.

The captain lit another pipe after they had gone, and for some time sat smoking and thinking over the events of the evening. Then Mr. Tasker’s second infringement of discipline occurred to him, and, stretching out his hand, he rang the bell.

“Has that young woman gone?” he inquired, cautiously, as Mr. Tasker appeared.

“Yessir,” was the reply.

“What about your articles?” demanded the captain, with sudden loudness. “What do you mean by it?”

Mr. Tasker eyed him forlornly. “It ain’t my fault,” he said, at last. “I don’t want her.”

“Eh?” said the other, sternly. “Don’t talk nonsense. What do you have her here for, then?”

“Because I can’t help myself,” said Mr. Tasker, desperately; “that’s why. She’s took a fancy to me, and, that being so, it would take more than you and me to keep ’er away.”

“Rubbish,” said his master.

Mr. Tasker smiled wanly. “That’s my reward for being steady,” he said, with some bitterness; “that’s what comes of having a good name in the place. I get Selina Vickers after me.”

“You—you must have asked her to come here in the first place,” said the astonished captain.

“Ask her?” repeated Mr. Tasker, with respectful scorn. “Ask her? She don’t want no asking.”

“What does she come for, then?” inquired the other.

“Me,” said Mr. Tasker, brokenly. “I never dreamt o’ such a thing. I was going ’er way one night—about three weeks ago, it was—and I walked with her as far as her road—Mint Street. Somehow it got put about that we were walking out. A week afterwards she saw me in Harris’s, the grocer’s, and waited outside for me till I come out and walked ’ome with me. After she came in the other night I found we was keeping company. To-night—tonight she got a ring out o’ me, and now we’re engaged.”

“What on earth did you give her the ring for if you don’t want her?” inquired the captain, eyeing him with genuine concern.

“Ah, it seems easy, sir,” said the unfortunate; “but you don’t know Selina. She bought the ring and said I was to pay it off a shilling a week. She took the first shilling to-night.”

His master sat back and regarded him in amazement.

“You don’t know Selina, sir,” repeated Mr. Tasker, in reply to this manifestation. “She always gets her own way. Her father ain’t ’it ’er mother not since Selina was seventeen. He dursent. The last time Selina went for him tooth and nail; smashed all the plates off the dresser throwing ’em at him, and ended by chasing of him up the road in his shirt-sleeves.”

The captain grunted.

“That was two years ago,” continued Mr. Tasker; “and his spirit’s quite broke. He ’as to give all his money except a shilling a week to his wife, and he’s not allowed to go into pubs. If he does it’s no good, because they won’t serve ’im. If they do Selina goes in next morning and gives them a piece of ’er mind. She don’t care who’s there or what she says, and the consequence is Mr. Vickers can’t get served in Binchester for love or money. That’ll show you what she is.”

“Well, tell her I won’t have her here,” said the captain, rising. “Good-night.”

“I’ve told her over and over again, sir,” was the reply, “and all she says is she’s not afraid of you, nor six like you.”

The captain fell back silent, and Mr. Tasker, pausing in a respectful attitude, watched him wistfully. The captain’s brows were bent in thought, and Mr. Tasker, reminding himself that crews had trembled at his nod and that all were silent when he spoke, felt a flutter of hope.

“Well,” said the captain, sharply, as he turned and caught sight of him, “what are you waiting there for?”

Mr. Tasker drifted towards the door which led upstairs.

“I—I thought you were thinking of something we could do to prevent her coming, sir,” he said, slowly. “It’s hard on me, because as a matter of fact——”

“Well?” said the captain.

“I—I’ve ’ad my eye on another young lady for some time,” concluded Mr. Tasker.

He was standing on the bottom stair as he spoke, with his hand on the latch. Under the baleful stare with which the indignant captain favoured him, he closed it softly and mounted heavily to bed.

CHAPTER V

Mr. Chalk’s expedition to the Southern Seas became a standing joke with the captain, and he waylaid him on several occasions to inquire into the progress he was making, and to give him advice suitable for all known emergencies at sea, together with a few that are unknown. Even Mr. Chalk began to tire of his pleasantries, and, after listening to a surprising account of a Scotch vessel which always sailed backwards when the men whistled on Sundays, signified his displeasure by staying away from Dialstone Lane for some time.

Deprived of his society the captain consoled himself with that of Edward Tredgold, a young man for whom he was beginning to entertain a strong partiality, and whose observations of Binchester folk, flavoured with a touch of good-natured malice, were a source of never-failing interest.

“He is very wide-awake,” he said to his niece. “There isn’t much that escapes him.”

Miss Drewitt, gazing idly out of window, said that she had not noticed it.

“Very clever at his business, I understand,” said the captain.

His niece said that he had always appeared to her—when she had happened to give the matter a thought—as a picture of indolence.

“Ah! that’s only his manner,” replied the other, warmly. “He’s a young man that’s going to get on; he’s going to make his mark. His father’s got money, and he’ll make more of it.”

Something in the tone of his voice attracted his niece’s attention, and she looked at him sharply as an almost incredible suspicion as to the motive of this conversation flashed on her.

“I don’t like to see young men too fond of money,” she observed, sedately.

“I didn’t say that,” said the captain, eagerly. “If anything, he is too open-handed. What I meant was that he isn’t lazy.”

“He seems to be very fond of coming to see you,” said Prudence, by way of encouragement.

“Ah!” said the captain, “and——”

He stopped abruptly as the girl faced round. “And?” she prompted.

“And the crow’s-nest,” concluded the captain, somewhat lamely.

There was no longer room for doubt. Scarce two months ashore and he was trying his hand at matchmaking. Fresh from a world of obedient satellites, and ships responding to the lightest touch of the helm, he was venturing with all the confidence of ignorance upon the most delicate of human undertakings. Miss Drewitt, eyeing him with perfect comprehension and some little severity, sat aghast at his hardihood.

“He’s very fond of going up there,” said Captain Bowers, somewhat discomfited.

“Yes, he and Joseph have much in common,” remarked Miss Drewitt, casually. “They’re somewhat alike, too, I always fancy.”

“Alike!” exclaimed the astonished captain. Edward Tredgold like Joseph? Why, you must be dreaming.”

“Perhaps it’s only my fancy,” conceded Miss Drewitt, “but I always think that I can see a likeness.”

“There isn’t the slightest resemblance in the world,” said the captain. “There isn’t a single feature alike. Besides, haven’t you ever noticed what a stupid expression Joseph has got?”

“Yes,” said Miss Drewitt.

The captain scratched his ear and regarded her closely, but Miss Drewitt’s face was statuesque in its repose.

“There—there’s nothing wrong with your eyes, my dear?” he ventured, anxiously—“short sight or anything of that sort?”

“I don’t think so,” said his niece, gravely.

Captain Bowers shifted in his chair and, convinced that such a superficial observer must have overlooked many things, pointed out several admirable qualities in Edward Tredgold which he felt sure must have escaped her notice. The surprise with which Miss Drewitt greeted them all confirmed him in this opinion, and he was glad to think that he had called her attention to them ere it was too late.

“He’s very popular in Binchester,” he said, impressively. “Chalk told me that he is surprised he has not been married before now, seeing the way that he is run after.”

“Dear me!” said his niece, with suppressed viciousness.

The captain smiled. He resolved to stand out for a long engagement when Mr. Tredgold came to him, and to stipulate also that they should not leave Binchester. An admirer in London to whom his niece had once or twice alluded—forgetting to mention that he was only ten—began to fade into what the captain considered proper obscurity.

Mr. Edward Tredgold reaped some of the benefits of this conversation when he called a day or two afterwards. The captain was out, but, encouraged by Mr. Tasker, who represented that his return might be looked for at any moment, he waited for over an hour, and was on the point of departure when Miss Drewitt entered.

“I should think that you must be tired of waiting?” she said, when he had explained.

“I was just going,” said Mr. Tredgold, as he resumed his seat. “If you had been five minutes later you would have found an empty chair. I suppose Captain Bowers won’t be long now?”

“He might be,” said the girl.

“I’ll give him a little while longer if I may,” said Mr. Tredgold. “I’m very glad now that I waited—very glad indeed.”

There was so much meaning in his voice that Miss Drewitt felt compelled to ask the reason.

“Because I was tired when I came in and the rest has done me good,” explained Mr. Tredgold, with much simplicity. “Do you know that I sometimes think I work too hard?”

Miss Drewitt raised her eyebrows slightly and said, “Indeed!—I am very glad that you are rested,” she added, after a pause.

“Thank you,” said Mr. Tredgold, gratefully. “I came to see the captain about a card-table I’ve discovered for him. It’s a Queen Anne, I believe; one of the best things I’ve ever seen. It’s poked away in the back room of a cottage, and I only discovered it by accident.”

“It’s very kind of you,” said Miss Drewitt, coldly, “but I don’t think that my uncle wants any more furniture; the room is pretty full now.”

“I was thinking of it for your room,” said Mr. Tredgold.

“Thank you, but my room is full,” said the girl, sharply.

“It would go in that odd little recess by the fireplace,” continued the unmoved Mr. Tredgold. “We tried to get a small table for it before you came, but we couldn’t see anything we fancied. I promised the captain I’d keep my eyes open for something.”

Miss Drewitt looked at him with growing indignation, and wondered whether Mr. Chalk had added her to his list of the victims of Mr. Tredgold’s blandishments.

“Why not buy it for yourself?” she demanded.

“No money,” said Mr. Tredgold, shaking his head. “You forget that I lost two pounds to Chalk the other day, owing to your efforts.”

“Well, I don’t wish for it,” said Miss Drewitt, firmly. “Please don’t say anything to my uncle about it.”

Mr. Tredgold looked disappointed. “As you please, of course,” he remarked.

“Old things always seem a little bit musty,” said the girl, softening a little. “I, should think that I saw the ghosts of dead and gone players sitting round the table. I remember reading a story about that once.”

“Well, what about the other things?” said Mr. Tredgold. “Look at those old chairs, full of ghosts sitting piled up in each other’s laps—there’s no reason why you should only see one sitter at a time. Think of that beautifully-carved four-poster.”

“My uncle bought that,” said Miss Drewitt, somewhat irrelevantly.

“Yes, but I got it for him,” said Mr. Tredgold. “You can’t pick up a thing like that at a moment’s notice—I had my eye on it for years; all the time old Brown was bedridden, in fact. I used to go and see him and take him tobacco, and he promised me that I should have it when he had done with it.”

“Done with it?” repeated the girl, in a startled voice. “Did—did he get another one, then?”

Mr. Tredgold, roused from the pleasurable reminiscences of a collector, remembered himself suddenly. “Oh, yes, he got another one,” he said, soothingly.

“Is—is he bedridden now?” inquired the girl.

“I haven’t seen him for some time,” said Mr. Tredgold, truthfully. “He gave up smoking and—and then I didn’t go to see him, you know.”

“He’s dead,” said Miss Drewitt, shivering. “He died in—— Oh, you are horrible!”

“That carving—” began Mr. Tredgold.

“Don’t talk about it, please,” said the indignant Miss Drewitt. “I can’t understand why my uncle should have listened to your advice at all; you must have forced it on him. I’m sure he didn’t know how you got it.”

“Yes, he did,” said the other. “In fact, it was intended for his room at first. He was quite pleased with it.”

“Why did he alter his mind, then?” inquired the girl.

Mr. Tredgold looked suddenly at the opposite wall, but his lips quivered and his eyes watered. Miss Drewitt, reading these signs aright, was justly incensed.

“I don’t believe it,” she cried.

“He said that you didn’t know and he did,” said Mr. Tredgold, apologetically. “I talk too much. I’d no business to let out about old Brown, but I forgot for the moment—sailors are always prone to childish superstitions.”

“Are you talking about my uncle?” inquired Miss Drewitt, with ominous calm.

“They were his own words,” said the other.

Miss Drewitt, feeling herself baffled, sat for some time wondering how to find fault politely with the young man before her. Her mind was full of subject-matter, but the politeness easily eluded her. She threw out after a time the suggestion that his presence at the bedside of sick people was not likely to add to their comfort.

Captain Bowers entered before the aggrieved Mr. Tredgold could think of a fitting reply, and after a hasty greeting insisted upon his staying for a cup of tea. By a glance in the visitor’s direction and a faint smile Miss Drewitt was understood to endorse the invitation.