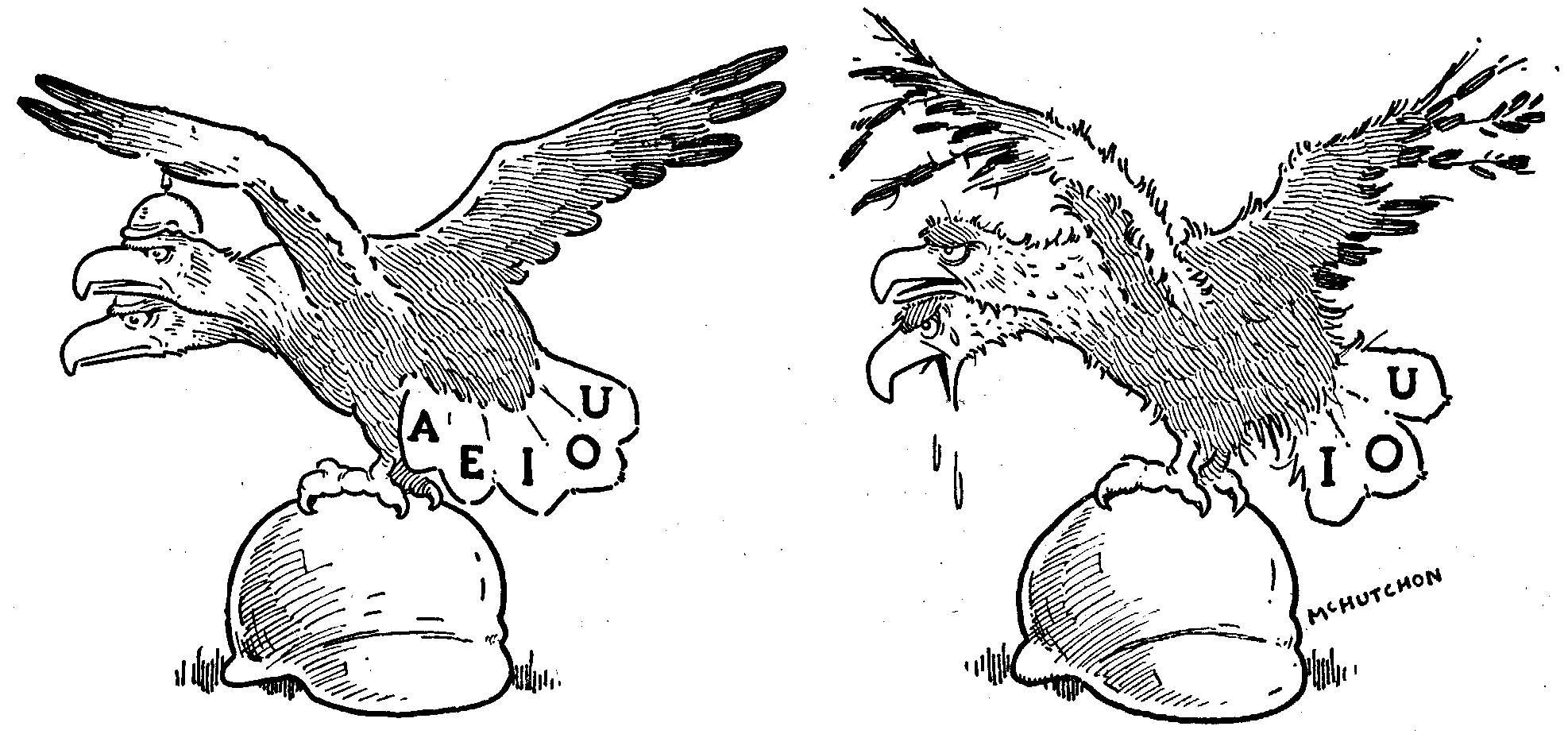

"AUSTRIAE EST IMPERARE ORBI UNIVERSO".

| ONCE UPON A TIME. | TO-DAY. |

Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Volume 156, May 28, 1919

Author: Various

Release date: May 1, 2004 [eBook #12232]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Malcolm Farmer, Sandra Brown and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team.

It was the pig, says an eminent Danish economist, that lost Germany the War. His omission to specify which pig seems almost certain to provoke further recriminations among the German High Command.

After all, the War may have wakened a new spirit in the nation. Up to the time of writing no one has attempted to corner mint-sauce.

A movement, we hear, is on foot to give a public welcome to the cheeses on their return to our midst. It is thought that a march-past could easily be arranged.

Hackney will supply electricity to consumers at a special rate during the Peace celebrations. The present price of one-and-sixpence per kilowatt-and-soda practically inhibits anything like deep-seated festivity.

A Miners' Association in the North has decided not to establish a weekly newspaper. Pending other arrangements they will do a little light mining, but it must not be taken as a precedent.

At a meeting of Hassocks allotment-holders a speaker stated that he had seen rabbits jump a fence five feet high. Experts declare that this is at least three feet over proof.

As the outcome of suggestions by the Economy Committee at Eton Dr. ALINGTON has made certain restrictions in regard to various articles of dress, notably socks and mufflers. Henceforward only such socks as do not require muffling will be worn.

The cow that walked into the lending library at Walton Heath has since explained that it merely wanted to look up "Manchuria" in the encyclopaedia.

It is said that the question of neutrality has caused most of the delay in the formation of the League of Nations. We certainly realise the difficulty in deciding how Norway and Switzerland could come to grips, in the event of a War between these two countries, without infringing the laws of neutrality.

"No harm to the moon will result from the eclipse of the sun on May 28th," states a writer in an evening paper. This is good news for those who have mining shares there.

There is a falling off in the tanning of kids in India, says The Shoe and Leather Trades Record. Smith minor talks of migrating to the Orient.

Government ale, says a trade paper, will shortly be on sale in some parts of Ireland. This certainly ought to be a lesson to them.

Two Parisians who had previously arranged to fight a duel have refused to meet. It is supposed that they have quarrelled.

As we go to press we are informed on good authority that the cat that developed rabies last week has now been successfully killed eight times, and it is expected that its final execution will have taken place by the time this appears in print.

We understand that the Tredegar Fire Brigade strike is settled. Patrons are asked to bear with the Brigade, who have promised to work off arrears of fires in strict rotation.

A Surrey Church magazine appeals for funds to renovate the church exits. For ourselves, if we were a parson, we shouldn't worry about getting people out of church so long as we got them in.

A Scottish Chamber of Commerce has passed a resolution in favour of smaller One Pound Treasury Notes. If at the same time they could be made a bit cheaper the movement would be a popular one.

A taxi-driver who knocked down a pedestrian in Edgware Road and then drove off has been summoned. His defence is that he mistook the unfortunate man for an intending fare.

The Northumberland Miners' Council has passed a resolution calling on the Government to evacuate our troops from Russia, drop the Conscription Bill, remove the blockade and release conscientious objectors. Their silence on the subject of Dalmatia is being much commented on.

A report reaches us that Jazz is about to be made a notifiable disease.

If wound stripes were given to soldiers on becoming casualties to Cupid's archery barrage, Ronnie Morgan's sleeve would be stiff with gilt embroidery. The spring offensive claimed him as an early victim. When be became an extensive purchaser of drab segments of fossilized soap, bottles of sticky brilliantine with a chemical odour, and postcards worked with polychromatic silk, the billet began to make inquiries.

"It's that little mam'zelle at the shop in the Rue de la République," reported Jim Brown. "He spends all his pay and as much as he can borrow of mine to get excuses for speaking to her."

There was a period of regular visits and intense literary activity on the part of Ronnie, followed by the sudden disappearance of Mam'zelle and an endeavour by the disconsolate swain to liquidate his debts in kind.

"I owe you seven francs, Jim," said he. "If you give me another three francs and I give you two bottles of brilliantine and a cake of vanilla-flavoured soap we'll be straight."

"Not me!" said Jim firmly. "I've no wish to be a scented fly-paper. Have you frightened her away?"

"She's been swept away on a flood of my eloquence," said Ronnie sadly. "But in the wrong direction; and after I'd bought enough pomatum from her to grease the keel of a battleship, and enough soap to wash it all off again. Good soap it is too, me lad; lathers well if you soak it in hot water overnight."

"How did you come to lose her?" asked Jim, steering the conversation out of commercial channels.

"The loss is hers," said Ronnie; "I wore holes in my tunic leaning over the counter talking to her, and I made about as much progress as a Peace Conference. I got soap instead of sympathy and scent instead of sentiment. However, she must have got used to me, because one day she asked if I would translate an English letter she'd received into French.

"'Now's your chance to make good,' I thought, language being my strong suit; but I felt sick when I found it was a love-letter from a presumptuous blighter at Calais, who signed himself 'Your devoted Horace.' Still, to make another opportunity of talking to her, I offered to write it out in French. She sold me a block of letter-paper for the purpose, and I went home and wrote a lifelike translation.

"She gave me a dazzling smile and warm welcome when I took it in, but on the balance I didn't feel that I'd done myself much good. And next day I'm dashed if she didn't give me another letter to translate, this time signed 'Your loving Herbert.' Herbert, I discovered, was a sapper who'd been transferred to Boulogne and, judging by his hand, was better with a shovel than a pen. As an amateur in style I couldn't translate his drivel word for word. Like Cyrano, the artist in me rose supreme, and I manicured and curled his letter, painted and embroidered it, and nearly finished by signing 'Ronnie' instead of 'Herbert.'

"She was quite surprised when she read the translation.

"'C'est gentil, n'est-ce-pas?' said she, kissing it and stuffing it away in her belt. 'I did not think,' she went on in French, 'that the dear stupid 'Erbert had so much eloquence.' I saw my error. I had made a probable of a horse that hadn't previously got an earthly. So, to adjust things, I refrigerated the next letter—which happened to be from 'Orace—to the temperature of codfish on an ice block. And the consequence was that Georgette sulked and would scarcely speak to me for three whole days.

"The situation, coldly reviewed, appeared to be like this. When 'Orace or 'Erbert pleased her I got a share of the sunshine, but when their love-making cooled her displeasure was visited on poor Ronnie. Any advances on my own part were countered with sales of soap, customers apparently being rarer than lovers. So I had to bide my time.

"But one day letters from 'Orace and 'Erbert arrived simultaneously, and were duly handed to the fourth party for necessary action. It occurred to me that when the time came for me to enter the race on my own behalf I need have little fear of 'Erbert as a rival, so I determined to cut 'Orace out of the running.

"I translated his letter first. I censored the tender parts, spun out the padding and served it up like cold-hash. Then I set to work on 'Erbert. I got the tremolo stop out and the soft pedal on and made a symphony of it. I made it a stream of trickling melody—blue skies, yellow sunshine and scent of roses, with Georgette perched like a sugar goddess on a silver cloud and 'Erbert trying to clamber up to her on a silk ladder. To read it would have made a Frenchman proud of his own language. Then, for dramatic effect, I took the letters, put them on the counter and walked out without a word. 'That,' thought I, 'will do 'Orace's business—and then for 'Erbert!'

"Next day, when I went to see the result, to my surprise I found that her place behind the counter was taken by that little red-haired Celestine.

"'Where's Georgette?' said I.

"'Ah, M'sieur, she has gone,' said Celestine. 'Figure to yourself, this 'Orace, who used to write with ardour and spirit, sent her yesterday a poor pitiful note. It made one's heart bleed to read it, such halting appeal, such inarticulate sentiment. "Le pauvre garçon!" cried Georgette, "his passion is so strong he cannot find words for it. He is stricken dumb with excess of feeling. I must be at his side to comfort him." And she has flown like the wind to Calais, that she may be affianced to him. But if M'sieur desires to buy the soap I know the kind you prefer.'

"So you see me," concluded Ronnie plaintively, "bankrupt in love and money. Three francs, Jim, and I'll chuck in a packet of post-cards."

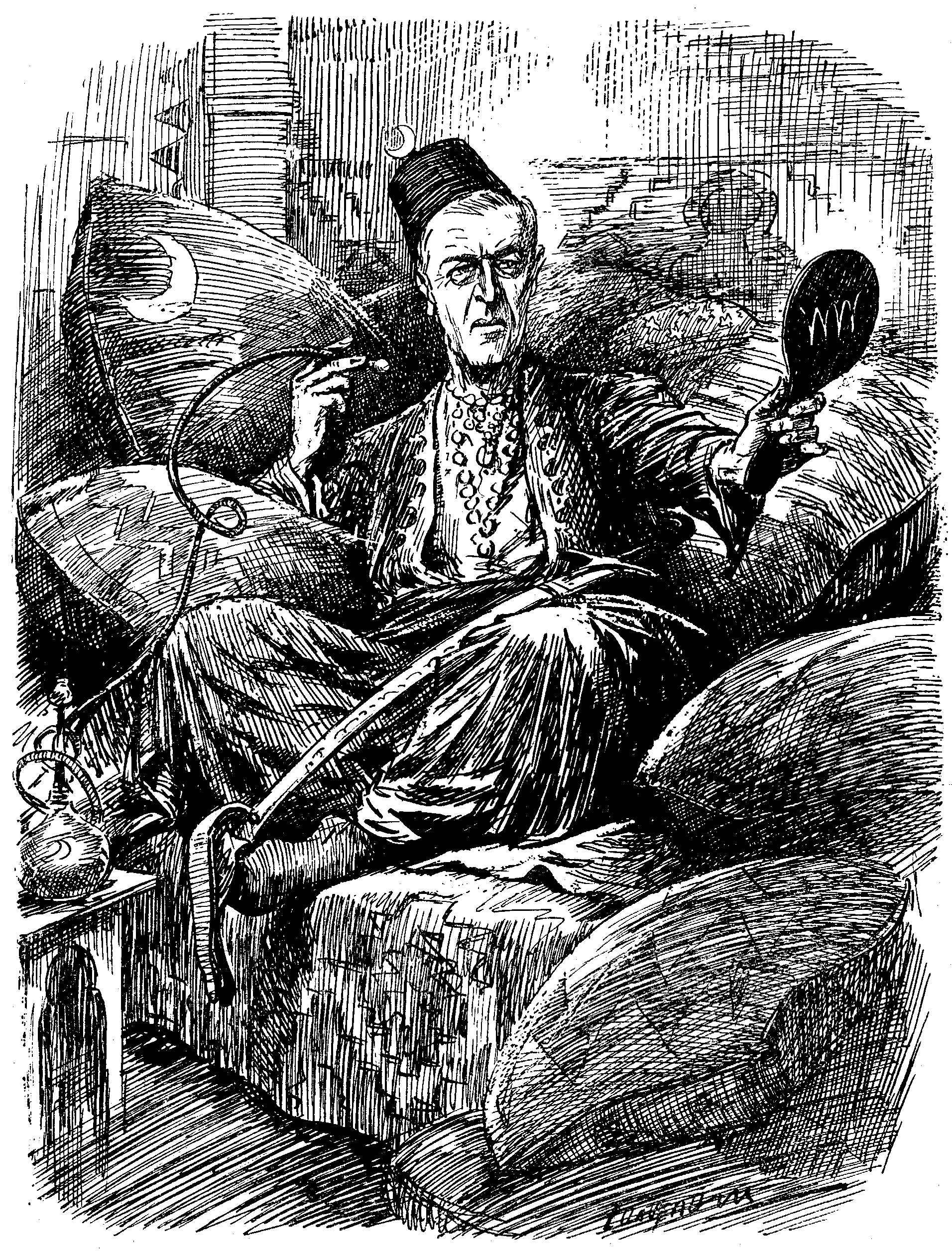

I.—THE BUREAUCRAT.

Along a narrow mountain track

Stalking supreme, alone,

Head upwards, hands behind his back,

He swings his sixteen stone.

Quit of the tinsel and the glare

That lit his forbears' lives,

His tweed-clad shoulders amply bear

The burden that was CLIVE'S.

A man of few and simple needs

He smokes a briar—and yet

His rugged signature precedes

The half an alphabet.

Across these green Elysian slopes

The Secretariat gleams,

The playground of his youthful hopes,

The workshop of his schemes.

He sees the misty depths below,

Where plain and foothills, meet,

And smiles a wistful smile to know

The world is at his feet;

To know that England calls him back;

To know that glory's path

Is leading to a cul de sac

In Cheltenham or Bath;

To know that all he helped to found,

The India of his prayers,

Has now become the tilting ground

Of MILL-bred doctrinaires.

But his the inalienable years

Of faith that stirred the blood,

Of zeal that won through toil and tears,

And after him—the flood.

J.M.S.

Our Feminine Athletes.

"Wanted, Young Lady, vaults bar.—Apply personally, Mrs. ——, Oddfellows' Arms."—Provincial Paper.

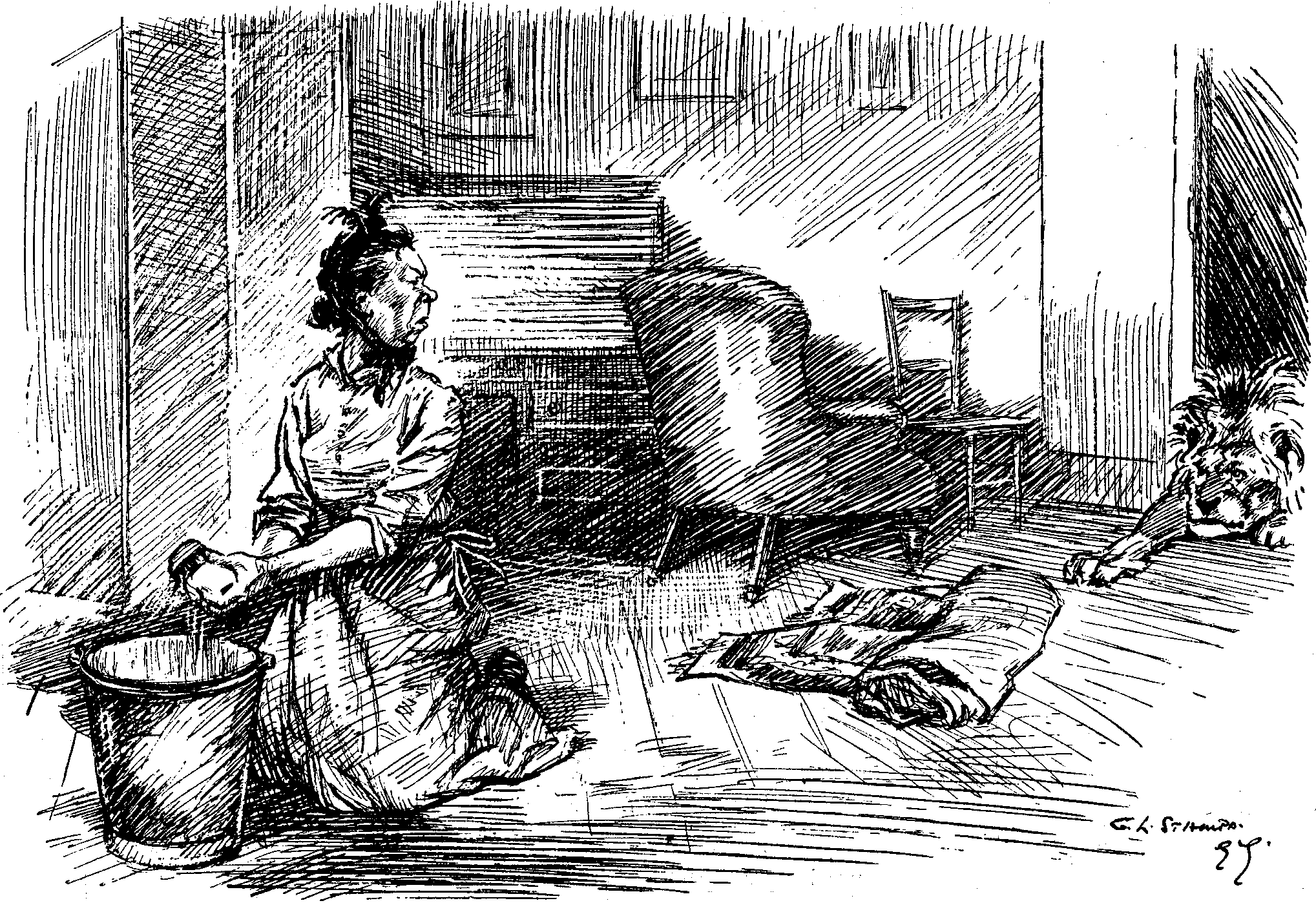

PERFORMING LION AT MUSIC-HALL, HAVING GOT LOOSE, FINDS ITS WAY TO ROOM OCCUPIED BY CHARWOMAN.

Char. "NAH, THEN! I WON'T 'AVE THEM NASTY THINGS IN 'ERE. I CAN'T ABIDE 'EM."

PEACE AND OTHER COMPLICATIONS.

DEAREST DAPHNE,—Already everyone's got peace-strain and what state we shall all be in by the time it's actually signed I haven't the dimmest. People have their own ideas of how they mean to celebrate it, and when they find that other people have the same ideas and mean to do the same things at the same time there are alarums and excursions, and things are said, and quite several people who were dear friends during the War don't speak now owing to the peace!

Par exemple, marches and processions being so much in the air, I'd planned a lovely Procession of Knitters; two enormous gilt knitting-needles to be carried by the leaders and a banner with "We Knitted our Way to Victory!" and myself on a triumphal car dressed in white silk-knitting. And then, just as everything was being arranged at our "Knitters' Peace Procession" committee meetings, I found that Beryl Clarges had stolen my idea and was arranging a "Crochet Peace Procession," with an immense gilt crochet-hook to be carried in front, and a banner with some nonsense about crochet on it, and herself on a triumphal car dressed in crochet!

I said exactly what I thought before I left off speaking to her.

Then, again, everyone wants to give a dance on peace night. I'd settled to give a big affair with some perfectly new departures, and all the nicest people I wanted have said, "Sorry, dearest, but I'm giving one myself that night." I've no patience with the silliness and selfishness of everybody.

Talking of dances, one's getting a bit dégoûtée of Jazz bands and steps. When ces autres get hold of anything it always begins to leave off being amusing. There's really a new step, however, the Peace Leap, that hasn't yet been quite usé and spoilt by the outlying tribes. The origin of it was a little funny. Chippy Havilland was at one of Kickshaw's Jazz dinners one night, where people fly out of their seats to one-step and two-step between the courses and during the courses and all the time. Well, while Chippy was eating his fish the band struck up that catchy Jazz-stagger, "She's corns on her toes," and Chippy, his mouth full of fish, jumped up and began to dance. Of course several fish-bones flew down his throat, and while he was choking he did such fearful and wonderful things that the whole room, not dreaming the poor dear was at his dernier soupir, broke out clapping and shouting and then imitated him, and by the time Chippy felt better he found himself famous and everybody doing the Peace Leap, which has completely cut out the Jazz-stagger, the Wolf's Prowl and everything else.

Oh, my dearest, who do you think are among the crowd of married people who're going to celebrate peace by dissolving partnership? The Algy Mallowdenes! Our prize couple! The flitchiest of Dunmow Flitch pairs! The turtlest of turtle—doves! Whenever people spoke of marriage as played out other people always weighed in with, "Well, but look at the Algy Mallowdenes."

They married on war-bread and [pg 417] Government cheese and kisses (unrationed). Seriously, though, m'amie, I believe they'd scarcely anything beyond his two thousand pounds a year as Permanent Irremovable Assistant Under-Secretary at the No-Use-Coming-Here Office. Certainly an "official residence" and a staff of servants were allowed 'em, but when poor Lallie asked to have a ball-room built, and Algy said he simply must have a billiard-room and smoke-room added, one of those fearful red-flag creatures got up in the House just as the money was going to be voted and made such an uproar that the matter was dropped.

And then, having heaps of spare time at the No-Use-Coming-Here Office, Algy began to write novels and found himself at once. You've read some of them, of course? Life with a big L, my dear. Every kind of world while you wait, the upper, the under, and the half. Lallie was very glad of the money that came rolling in, but I believe she said wistfully, "How does my gentle quiet Algy know so much about this, that and the other?" And her gentle quiet Algy made answer: "Intuition, dear; imagination; the novelist's temperament."

By-and-by, however, she began to hear of his being seen at the Umpty Club and Gaston's, chatting with Pearl Preston (one of those people, you know, Daphne, who're immensely talked about but never mentioned). And then a "certain liveliness" set in at the official residence of the Permanent Irremovable Assistant Under-Secretary.

"You silly little goosey!" said Algy; "don't you see that it's not as a man who admires her but as a novelist who's studying her that I talk to Pearl Preston? She's my next heroine. A heroine like that is a sine quâ non in a novel of the Modernist school."

But Lallie couldn't see the dif between a man and a novelist, and Algy couldn't write his best seller without studying its heroine, and so—and so—at last our poor prize couple are in that long list that an overworked judge complained of the other day. And if you ask for the moral I suppose it's "Don't try to study character where there isn't any."

This is emphatically a season for arms, my Daphne, which seems quite a good little idea for peace-time! Faces and figures don't count; it's the arm, the whole arm and nothing but the arm! There are all sorts of stunts for attracting attention to round white arms, and if one has the other kind one had better go and do a rest-cure. Your Blanche is beyond criticism in that respect, as you know, and the other night at the opera I'd a succès fou with a big black-enamel beetle, held in place by an invisible platinum chain, crawling on my upper arm.

Lady Manoeuvrer is simply ravie de joie at the rage for arms, for her Daffodil, who's been a great worry to her (she's the only clever one, you know, all the others being pretty), has the best arms of the whole bunch. She's taken Madame Fallalerie's course, "The Fascination of the Arms," and is made to flourish hers about from morn to night, poor child, till she sometimes does a small weep from sheer exhaustion. The other day at Kempford Races, in a no-sleeved coatee with a black sticking-plaster racehorse in full gallop on her upper arm, she attracted plenty of attention and had two offers, I hear. Arms and the man, again!

À propos, Lady Manoeuvrer told me yesterday she'd sent a thank-offering to one of the hospitals. "But how sweet of you!" I said. "For the restoration of Peace, I suppose?" "No, dearest," she whispered; "for the restoration of the London Season!"

Ever thine, BLANCHE.

"LETTS TAKE RIGA."

Daily Mail.

Yes, and let's keep it.

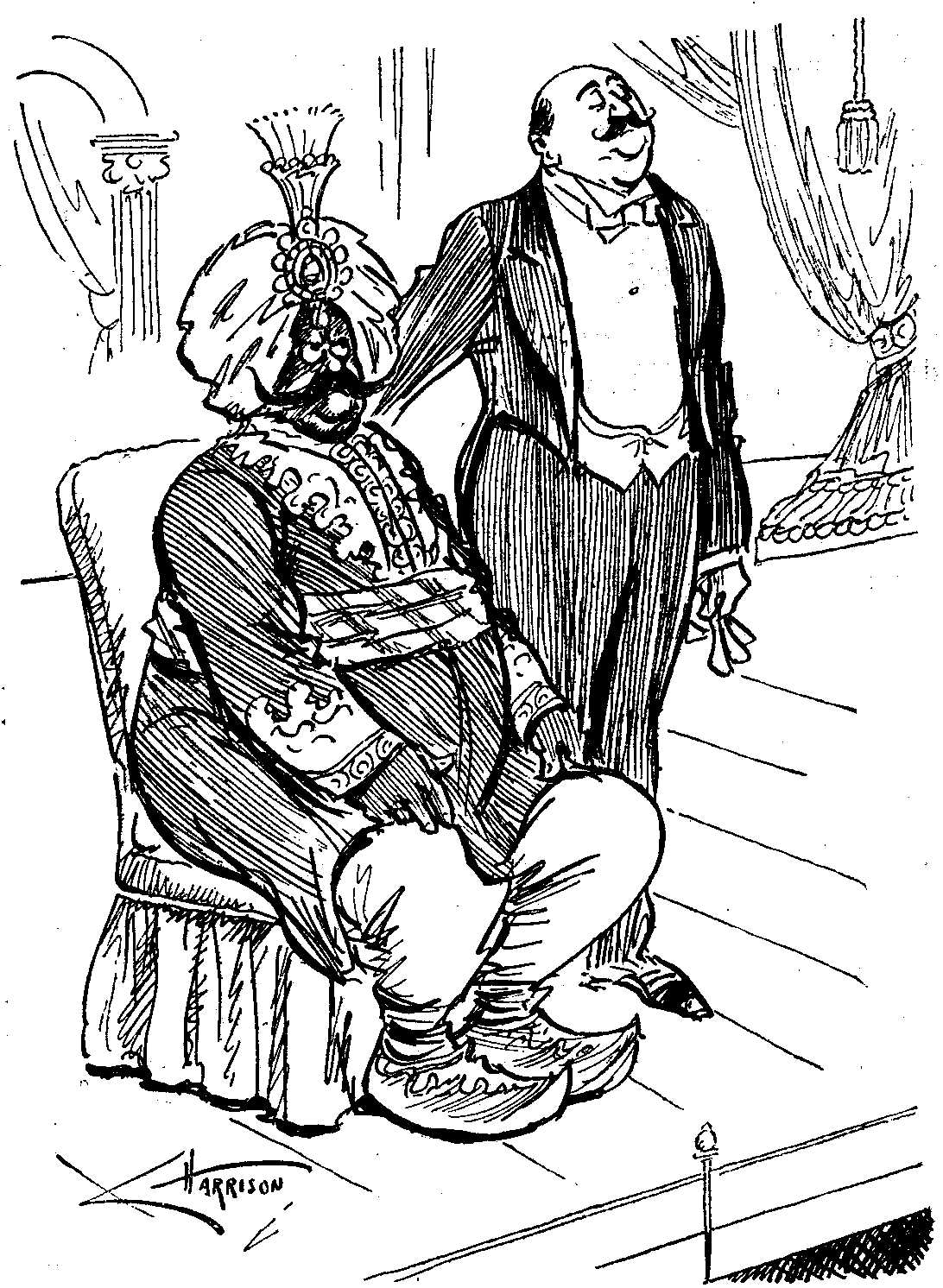

Manager (introducing music-hall turn). "LADIES AND GENTLEMEN, KHAGOOLA WILL NOW PROCEED TO GIVE HIS ASTOUNDING CLAIRVOYANT, MEMORY AND SECOND SIGHT ACT, AND WILL ANSWER ANY QUESTION THAT ANY MEMBER OF THE AUDIENCE MAY PUT TO HIM."

Voice from Gallery. "TELL US WHERE THERE'S A 'OUSE TO LET."

This was to have been an essay from an igloo, describing the awful privations of the writer and the primitive savagery of his surroundings on the Murman coast. It was to have wrung the sympathetic heart of the public and at the same time to have enthralled the student of barbaric life with its wealth of exotic detail. While embodying all the best-known newspaper clichés appropriated to these latitudes it was to have included others specially and laboriously prepared after a fascinating study of Arctic literature.

But circumstances have blighted its early inspiration, and the article it was to have been will never be written, the telling word-pictures designed on board the transport never executed.

Figure the disgust of five adventurers who, landing at the Murman base, sternly braced to encounter the last extremity of peril and of hardship, to sleep in the snow and dig one another out o' mornings, to give the weakest of their number the warmest icicle to suck, the longest candle to chew—found themselves billeted in a room which the landladies of home would delight to advertise! Its walls were hung with such pictures as give cheap lodgings half their horror; it was encumbered with countless frail chairs and "kiggly" tables, and upon every flat surface had settled a swarm of albums, framed photographs, china dogs, wax flowers, penholder-stands, and all the choicest by-products of civilization struggling towards culture. As we were not to be frozen by exposure or immediately attacked by Bolshies, we might reasonably have expected to be asphyxiated by the Russian stove; but even this consolation was denied us, since Madame, convinced that the English are mad in their love of fresh air, consented to leave it unlit.

When first we arrived, five large soldiers with five large kits, the aspect of the room filled us with terror. The fiercest frost or foe we could have faced, but the bravest man may quail before wax-flowers and fragile tables top-heavy with ornaments and knick-knacks, and all felt that to encounter such things within the Arctic Circle was an unfair test of our fortitude. Why had not the War Office or some newspaper correspondent warned us?

Madame, however, proved to have a sense of proportion or humour; or perhaps the collection was not her own. In any case she showed no reluctance to displace family photographs or china dogs, and rapidly had the room cleared for action; so that now, when we roll about the floor in friendly struggle, it is only someone's toilet tackle that crashes with its spidery table, instead of cherished artificial fauna and flora.

Thanks to our serviceable and becoming Arctic kit and the steady approach of the Spring thaw, heralded by the preparation of spare bridges to replace the existing ones, we can defy the eccentricities of the climate. Even the language begins to reveal what might be termed hand-holds; though possibly, when the natives echo our words of greeting, painfully acquired from textbooks on Russian, they are simply imitating the sounds we make under the impression that they are learning a little English.

More difficult problems arise, however, regarding questions of military etiquette. Not King's Regulations, nor Military Law, nor any handbook devotes even a sub-paragraph to light and leading upon certain points which we have here to consider every day. For example, if a subaltern glissading on ski down the village street, maintaining his precarious balance by the aid of a "stick" in each hand, meets a General, also on ski and also a novice, what should happen? What does happen we know by demonstration: the subaltern brandishes both sticks round his head, slides forward five yards, smartly crosses the points of his ski and then, plunging forward, buries his head in the wayside drift, while the General Officer sits down and says what he thinks. But we do not know if these gestures of natural courtesy are such as our mentors would approve. No authority has set up for us any ideal in such matters. From official rules of deportment the British soldier knows how to salute when on foot or mounted on bicycle, horse, mule, camel, elephant, motor-lorry or yak, but no provision has been made for the case of an army scooting on ski. So here we are at large in the Arctic Circle, coping with new conditions by the light of nature, and paying such perilous "compliments" to senior officers as our innate courtesy and sense, of balance suggest and permit.

Further, consider the question of dress. Even the gunners, who in the late war used to wear riding-breeches of their favourite colour, no matter what it was, the kind of footgear they most fancied, and any old variety of hat they thought becoming, are shocked by the fantastic kit that is countenanced in this latitude. It must be borne in mind that most of us are old campaigners and old nomads whose tailors have grown accustomed to build us appropriate gear for various climes. Fashions for fighting in France, in Egypt, in Mesopotamia, have gained a hold upon our affections, to say nothing of those [pg 419] designs for civil breadwinning or moss-dodging in Central Africa, Bond Street, Kirkcaldy or Dawson City. The consequence is that here, pretty well out of A.P.M. range, sartorial individualism flourishes unchecked. Thus the eye is startled to behold a fur headdress as big as a busby, an ordinary service tunic, gaberdine breeches, shooting stockings and Shackleton boots, going about as component parts of one officer's make-up; or snow-goggles worn with flannel trousers, or sharp-toothed Boreas defied by a bare head and a chamois-leather jerkin; or the choice flowers of Savile Row associated with Canadian moccasins.

What idea will the North Russians retain of the outward appearance of the typical British officer? How will the little Lapps, befurred and smiling, who come sliding to market behind the trotting reindeer, report of us to the smaller Lapps at home? In any case I hope we shall found a legend of a well-meaning if peculiar and patchwork people.

British Matron (whose husband has just had his weekly coat of woad, to visitor). "I'M SORRY, SIR, BUT MY HUSBAND CAN'T SEE YOU TILL HE'S DRY."

"Gas Stoker wanted for 11 million works, used to gas engine and exhauster; 50s. per week of seven 12-hour shifts."—Advt. in Daily Paper.

In the circumstances the reference to "exhauster" seems superfluous.

The readers of the Personal Column of The Times were lately refreshed by the following entry:—

"Would the person in the green Tyrolese hat note that though it may be a custom on his own course to pocket golf-balls on the fairway, it is not done elsewhere."

For long the Personal Column has been a vehicle for appeal and regret, for affection and grief, in addition to its other manifold uses; but as an instrument of admonishment it is fresh. The tragic thing is that up to the time of going to press the green Tyrolese hat has made no reply. Either it does not read The Times or it has been rendered speechless. We were longing for some first-class recriminations.

The new fashion is sure to spread. For example, any morning we are liable to find this:—

Would the lady (?) in the purple toque note that, though it may be the thing in her home to disregard the feelings of others, the abstraction of someone else's chair at a White Sale at Blankridge's is not the thing.

And again:—

The female with a red parasol, who thought it her duty to struggle like a wild-cat for a place on a No. 11 bus, opposite the Stores, on Friday afternoon last at a quarter to three, may be interested in learning that the service is not run solely for her.

And a more intimate note still may be struck. Something like this may be looked for:—

Will Lydia Lopokova take pity on an unhappy and neglected wife, whose husband has stated that he would resume dining at home only on condition that the table was laid as it is laid in The Good-Humoured Ladies?

Before I was a little girl I was a little bird,

I could not laugh, I could not dance, I could not speak a word;

But all about the woods I went and up into the sky—

And isn't it a pity I've forgotten how to fly?

I often came to visit you. I used to sit and sing

Upon our purple lilac bush that smells so sweet in Spring;

But when you thanked me for my song of course you never knew

I soon should be a little girl and come to live with you.

R. F.

"Arbitration is to be adopted first in disputes between members of the League, then meditation by the Council."—Liverpool Paper.

I certainly hoped when I took up my quarters in this quiet village that there would be no jarring note to disturb the idyllic peace of my surroundings. And yet I had not been long in this pleasant sitting-room, with its outlook on blossom-laden fruit-trees, creamy-spired chestnuts and wooded down, before I became aware that a pitiful and rather sordid little domestic drama was in progress within fifty yards from my open windows. I discovered a son in the act of encouraging his aged and apparently imbecile parent to gamble with a professional swindler! Not that I have actually seen them thus engaged. As a matter of fact I have merely heard a few short remarks—and those were all spoken by the son. But, as everyone knows, even a single sentence accidentally overheard by an observant stranger may give him a clearer insight into the unknown, and possibly unseen, speaker's character than could be gained from countless chapters of a modern analytical novel.

So these four sentences were quite enough for me. Perhaps I should mention here that the three personages in this drama are birds—which makes it all the more painful.

Like many of our British birds, the sole speaker occasionally drops into English, or I should never have understood what was going on. He may be a blackbird or thrush, but I doubt it, because I know all their remarks, while his are new to me. If A.A.M. heard them he would probably tell me they were those of a "Blackman's Warbler," and I should have believed him—once. Hardly now, after he has so airily exposed his title as an authority; but even as it is I should not dream of questioning his statement that "the egg of course is rather more speckled," because I can well believe that the egg this bird—whatever he is—came from was very badly speckled indeed.

It seems that, some time ago—I can't say when exactly, but it was before I came down here—this unnatural son introduced to the parental abode (which I think is either No. 5 or No. 6 in a row of young chestnuts abutting on the high road) a rook of more than dubious reputation, whom he persuaded his unsuspecting sire to put up for the night. And there the rook has been ever since. As I said, I have neither heard nor seen him, but I'm positive he's there. I am unable to give the precise date on which he first led the conversation to the good old English game of "rigging the thimble"—that also was before I came. All I can state with certainty is that he interested his host in it so effectually that now the infatuated old fool is playing it all day long.

This is evident from his son's conversation; during the pause which invariably precedes it I should undoubtedly hear the father-bird (if he would only speak up—which he doesn't) quavering, "I'm not sure, my boy, I'm not sure, but I've a notion that, this time, he's left the pea under the middle thimble—eh?"

On which the young scoundrel, knowing well that it is elsewhere, pipes out, "There it is, Fa-ther, there it is, Fa-ther!" with an unctuous humility shading into impatient contempt that is simply indescribable, being indeed too revolting for words.

Then, as the father still wavers, his son makes some observations which I cannot quite follow, but take to be on the fairness of the game as played with a sportsbird, and the certainty that the luck must turn sooner or later. After which he exhorts him—this time in plain English—to "be a bird." Whereupon the doting old parent decides that he will be a bird and back the middle thimble, and the next moment I hear the son exclaim, evidently referring to the rook, "No, 'e's got it; no, 'e's got it. Cheer up! Cheer up!" with a perfunctory concern that is but a poor disguise for indecent exultation. I am not suggesting, by the way, that birds are in the habit of dropping their "h's"—but this one does. There are times when he is so elated by his parent's defeat that he cannot repress an outburst of inarticulate devilry. And so the game goes on, minute after minute, hour after hour, every day from dawn to dusk. The amount of grains or grubs or whatever the stakes may be (and it is not likely that any rook would play for love), that that old idiot must have lost even since I have been here, is beyond all calculation. He has never once been allowed to spot the right thimble, but he will go on. As to the son's motive in permitting it, any bird of the world would tell you that, if you possess a senile parent who is bound to be rooked by somebody, it had better be by a person with whom you can come to a previous arrangement.

Now I come to think of it, though, I have not heard the unnatural offspring once since I sat down to write this. Can it have dawned at last upon his parent that this is one of those little games where the odds are a trifle too heavy in favour of the Table? Or can the son have sickened of his own villainy and washed his claws of his shady confederate? I don't know why, but I am almost beginning to hope.... No; through the open window comes the well-known cry, "There it is, Fa-ther! There it is, Fa-ther! Be a bird! Be a bird!... No, 'e's got it! No, 'e's got it! Cheer up! Cheer up!" They are at it again!

[From inquiries made by a Daily Chronicle representative it appears that the present demand for housing accommodation is such that people no longer draw the line at ghosts.]

The problem at last is a thing of the past;

Doubts and fears, Geraldine, are at rest;

We can put up the banns and make definite plans,

For the love-birds will soon have a nest.

I've inspected, my sweet, the sequestered retreat

In which we are destined to dwell,

And on thinking things out I have not the least doubt

It will suit us exceedingly well.

There are drawbacks, I grant, but one nowadays can't

Have perfection, as you are aware,

And I'm sure you won't grouse when I state that the house

Is both damp and in need of repair.

I might add there's a floor that shows traces of gore;

I discovered the latter to be

That of one Lady Jane, who was brutally slain

By her husband in Sixteen-Two-Three.

Years have passed since the time of that dastardly crime,

But the victim's intangible shade

Can be seen to this day, so the villagers say,

In diaphanous garments arrayed.

In the gloom of the room where she met with her doom

She's appearing once nightly, it seems,

And the listener quails as lugubrious wails

Are succeeded by agonised screams.

But the trivial flaws I have mentioned need cause

No concern; I am certain that you

Will approve of my choice, Geraldine, and rejoice

In the thought that our haven's in view.

In the likely event of your mother's descent

There's the warmest of welcomes in store,

And a rug I'll provide for her bedroom, to hide

That indelible stain on the floor.

(On perceiving William in mufti again and carrying one.)

What is this implement of warfare, Bill?

What seed of fire within its entrails slumbers?

Does it unfold at all? Run through the drill,

Doing it first by numbers.

Not a grenade and not a parachute?

Some remnant rather of the ancient folly,

Some touch of times before the Big Dispute?

I have it now! A brolly.

Yes, and it opens outwards like a tent,

Guarding the sacred poll from skies injurious.

Up with it! Let us see your tops'ls bent.

How splendid! And how curious!

Do it again, Bill. I am better now;

Only at first, perhaps, I slightly trembled.

Press on the little clutch and show me how

The parts are reassembled.

To think men poked these things into the sky,

Fearing to face the storm's minutest particles,

Through four long hectic years, whilst you and I

Forgot there were such articles.

It brings the old times back to one again,

The grim-eyed crowd that faced the morning's dolours

Doing their very best to drip the rain

Down other people's collars;

The fond, fond pair beneath a single dome;

The fight to ride on Hammersmiths and Chelseas;

The rapture when you found on reaching home

Your gamp was someone else's.

O symbol of routine and office hours!

O emblem of the soft civilian status!

Shall I too deign to roof me from the showers

With such an apparatus?

Shall I consent to grasp within my hand

The sign of serfdom and to get the habit

Of marching like a mushroom down the Strand,

A mushroom on a rabbit?

Never. O hateful sight! And yet—and yet

I'm not so sure. This month has been a dry one;

June will most probably be beastly wet;

P'r'aps, after all, I'll buy one.

EVOE.

East is East.

"The Girl Guides are doing well.... Another guide was married this month to Corporal ——. We wish them all happiness."—Diocesan Magazine (India).

Corporal —— appears to be a specialist.

"There are persistent rumours of a plot to bring back the old régime and put either a Hohenzollern or a representative of some other Royal house on the Thorne of Germany."—Canadian Paper.

EX-KAISER (loq.): "No, thanks; I've had some."

"OXFORD FOR HOLIDAYS.—Most beautiful city in England. Good lodgings and boating. Two golf links and fishing."—Advt. in Provincial Paper.

We seem to remember, too, some mention of an educational establishment in connection with the place.

Our Helpful Contemporaries.

"There have been cases, we believe, in which the height of a person has increased after the person had reached mature age, but it has always been suspected that this was due to greater uprightness. A man who stoops always looks shorter than when he is standing quite upright. But no such explanation as this can be given for an apparent increase of the human head. If a head really requires a larger hat it must be because the head is larger."—Provincial Paper.

GERMAN DELEGATE. "SIGN? I'D SOONER DIE! (Aside) AFTER WHICH PRELIMINARY REMARKS I WILL NOW SELECT A NIB."

Monday, May 19th.—The coalminers lately received concessions in wages and hours that are going to cost the country twenty millions sterling in the present financial year. The first result of this boon (teste Sir AUCKLAND GEDDES) is that they are turning out less coal per man than ever, and that the unhappy consumer must look forward to a further reduction in his already meagre ration. It is rather hard upon Mr. SMILLIE, who daily dilates in the Coal Commission upon the hardships of the miner's life, that his clients should let him down like this.

For a thorough-going democrat commend me to Lieutenant-Commander KENWORTHY, the new Member for Central Hull, whose latest idea is that before British troops are sent to any new front the approval of the House of Commons should be obtained. I suspect that if, during his active-service days, some Member had proposed a similar restriction on the movements of the Fleet the comments of the gallant Commander himself would have been more pithy than Parliamentary.

The number of motor-cars at the disposal of the Air Ministry now stands at the apparently irreducible minimum of forty-two. Quite a number of the officials use train or bus, like ordinary folk; some have even been seen to walk; and there has been such a slump in "joy-riding" that when asked if ladies were now carried in the official chariots General SEELY was able to assure the House that that never happens; though I think he added under his breath—"well, hardly ever."

There was barely a quorum when Colonel LESLIE WILSON rose to introduce the estimates of the Shipping Controller. This was a pity, for he had a good story to tell of the mercantile marine, and told it very well. He was less successful on the subject of the "national shipyards," which have cost four millions of money and in two years have not succeeded in turning out a single completed ship. With the wisdom that comes after the event Sir CHARLES HENRY fulminated ferociously against the "superman" who had imposed this "disastrous scheme" upon the country.

This brought up the superman himself, Sir ERIC GEDDES, who in the most vigorous speech he has yet delivered in the House defended the scheme as being absolutely essential at the time it was initiated. It was a war-time expedient, which changing circumstances had rendered unnecessary; but if the War and the U-boat campaign had gone on it might have been the salvation of the country. After all you can't expect to have shipyards without making a few slips.

Tuesday, May 20th.—The advance of woman continues. Very soon she will have her foot upon the first rung of the judicial ladder, and be able to write J.P. after her name, for the LORD CHANCELLOR, pointing out that in this matter the Government were bound to honour the pledges of the PRIME MINISTER, gracefully swallowed Lord BEAUCHAMP'S Bill. He took occasion, however, to warn the prospective justicesses (if that is the right term) that, as the Commissions of the Peace were already fully manned, it might be some time before any large number of ladies could be added to the roll of those who, in the words of the Prayer-book, "indifferently administer justice."

Quite unintentionally, of course, Mr. BOTTOMLEY did the Government a real service in the Commons. Every day since his return from Paris Mr. BONAR LAW has been pestered with inquiries as to when, if ever, the House was to be allowed to discuss the Peace terms, and has evaded a direct answer with more or less ingenuity. This afternoon Mr. BOTTOMLEY, after hearing that the LEADER OF THE HOUSE had "nothing to add" to his previous replies, asked if he was right in supposing that, when the Treaty came up for ratification, the House must take it or leave it, and would have no power to amend it in any respect. Mr. LAW joyfully jumped at the chance of ending the daily catechism once for all. "That," he said, "exactly represents the position, and I do not see in what other way any Treaty could ever be arranged."

In anticipation of the debate on the Finance Bill Mr. SYDNEY ARNOLD sought an admission from the CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER that the income-tax on small incomes was hardly worth retaining, owing to the cost of collection. Not at all, said Mr. CHAMBERLAIN. It costs six hundred thousand pounds and brings in eight million. Of course, he added, it costs more proportionately to collect small amounts than large. If the whole of the income-tax could be paid by one individual the cost of collection would be nil. One imagined the CHANCELLOR on the eve of the Budget wishing, à la NERO, that the whole of the British people had but one purse, into which he could dip as deeply and as often as he pleased.

The debate on the Finance Bill was largely devoted to the proposed "levy on capital," which a section of the "Wee Frees," who already display fissiparous tendencies, have borrowed from the Labourites. After their amendment was framed, however, Mr. ASQUITH spoke at Newcastle, and ostentatiously refused to say a word about the new nostrum. Sir DONALD MACLEAN, anxious to avoid displeasing either his old leader or his new supporters, contented himself with the suggestion that a Commission should be set up to consider the subject.

The CHANCELLOR had little difficulty in disposing of the amendment. He might, indeed, have contented himself with quoting the War Bond advertisements, which daily inform us that the patriotic investor "will receive the whole of his money back with a substantial premium."

The Preference proposals which Mr. ACLAND had described as bred "by Filial Piety out of the Board of Trade" received the unexpected aid of Sir ALFRED MOND, who disposed of his Cobdenite prejudices as easily as the conjurer swallows his gloves, and unblushingly asserted that the tiny Preference now proposed, far from being the advance-guard of Protection, was in reality a very strong movement towards Free Trade. Comforted by this authoritative declaration Coalition Liberals helped the Government to defeat the amendment by 317 to 72.

Wednesday, May 21st.—The Peers being as usual rather short of work at this period of the Session, the LORD CHANCELLOR introduced a Bill "to enable the Official Solicitor for the time being to exercise powers and duties conferred on the person holding the office of Official Solicitor."

The rumours that have lately appeared in the papers, to the effect that the FIRST COMMISSIONER OF WORKS was contemplating revolutionary alterations at Hampton Court—in particular that he was going to transform the famous pond-garden into something quite different: a MOND-garden, in fact—are, it seems, grossly exaggerated. All that he has done is to appoint a Committee of experts to advise him what, if any, changes are desirable.

The resumed debate on the Finance Bill was enlivened by some personal details. By way of showing that even without a levy on capital the rich man bears his share of the burdens of the State, Sir EDWARD CARSON remarked that, when he receives a retainer, he immediately allows for the super-tax and enters it in his fee-book at only half the amount. He had had one that very morning. "Say it was five pounds"—and the House laughed loudly at such an absurd supposition.

Then we had Lord HUGH CECIL pointing his argument that the importance of the proposed Preference to the Dominions was political rather than economical by the remark that if he was going to be married—which he fervently hoped would not happen to him—he would expect his mythical bride to value his engagement-ring less for its pecuniary than its sentimental value.

A capital speech by Mr. STANLEY BALDWIN, one of the few men in the House who talks finance as if he really understood it, wound up the debate, and procured the Finance Bill a second reading nem. con.

Thursday, May 22nd.—The Ministry of Health Bill came up for third reading in the Lords. An eleventh-hour attempt by the Government to provide the new Minister with an additional Under-Secretary was heavily defeated, Lord DOWNHAM being appropriately enough one of the Tellers for the Opposition.

The Commons heard some good news. Mr. KENDALL'S pathetic story of an angling-party which, after walking five miles along a dusty road to its favourite hostelry, found it adorned with the now too frequent notice, "Closed—No Beer," brought a most sympathetic reply from Mr. GEORGE ROBERTS, who boldly confessed, "I am a believer in good beer myself," and later on announced that the Government had decided to increase the output from twenty million to twenty-six million standard barrels.

Geordie (after intently watching conductor of Jazz band for some time). "AH'VE HAD ENOUGH O' THIS. YON CHAP WI' STICK'S ONLY CODDIN'. HE'S NOT HIT ONE OF 'EM SINCE WE CAAME IN."

Farmer. "WELL, I BE MAIN GLAD TO SEE YOU BACK FROM THE WAR. I SUPPOSE YOU'LL BE THINKING OF TAKING TO WORK NOW?"

The original answer to the question at the head of these insignificant remarks was (correct me if I am wrong) nothing. "A rose," said Juliet, "by any other name would smell as sweet." But of course she was wrong. If a rose were handed to a visitor in the garden, with the words, "Do see how wonderful this onion is!" such a prejudice would be set up as fatally to impair its fragrance. There is, in fact, much in a name; and therefore the attempt of a correspondent of The Daily Express to find a generic nomenclature for domestic servants should be given very serious attention; the purpose being to meet "the objection felt by so many women servants to being either called by Christian or surname."

As a means of placating this very sensitive class the correspondent writes:—

"One nearly always calls a cook by the name of her calling. I therefore suggest that a name be adopted beginning with the first letter of the class. For example:—

| Lady's-maid | Louise. | |

| Parlourmaid | Palmer. | |

| Housemaid | Hannah. | |

| General | Gertrude. | |

| Scullerymaid | Sarah." |

Here we have materials for a sweeping innovation which might, if it spread, not only simplify life but reinforce the language. For why confine such terms to domestic servants? If all parlourmaids are to be called "Palmer," why not, for example, call all editors "Eddy" (very good Eddy, or very bad Eddy, according to taste)? And all London County Councillors, "Elsie"?

But let us look a little narrowly at the specimens given. "Palmer" for "parlourmaid" is good; but "Louise" does not reproduce the sound values of "lady's-maid." Some such word as "Lais" would be better, or why not "Lady-bird," which combines the desired similarity with the new euphemism "home-bird," invented to help transform domestic service to a privilege and pleasure? "Hannah" for "housemaid" is also wrong, although for "handmaid" it would be good. On the analogy of "Palmer," why not call all housemaids "How"? or even "House"?

If American Colonels can be called HOUSE, why not English housemaids? For generals "Jenny" would be better than "Gertrude"; and for scullery-maids "Scully." "Scully" is quite a good name; there is a distinguished psychologist named SULLY, and there was an M.P. for Pontefract named GULLY. No scullery-maid need be offended.

It is odd how we call some persons by their profession or calling, and others not. We say "Doctor," but we do not address our gum-architect as "Dentist." We say "Carpenter," but we do not address a plumber as "Plumber." (Incidentally, all plumbers might be called Warner). We say "Gardener" and "Coachman," but we do not address an advocate as "Barrister." If we had a definite rule everything would be simple, but as we have not it is necessary to find several more names. I am not at all satisfied with The Daily Express's test. For example, what would a second parlour-maid be called? If three were kept they might be called Palm, Palmer and Palmist. A long vista of difficulties opens.

["Encouraged by the summer weather yesterday, a titled lady took her tea with some friends on the footway at Belsize Park Gardens, Hampstead. Unsympathetic passers-by, however, complained of the obstruction ... and, following representation to the police by the public, the al-fresco tea-party was broken up."—Daily News.]

In spite of the innate conservatism of the police we are pleased to think that the seeds of a happy unconventionality, sown by this courageous lady of title, have already borne fruit.

On Thursday night, about ten o'clock, the attention of passers-by was drawn to a four-post bed, which was being trundled along the Strand by eight stalwart footmen. On it reposed the Duke of Sleepyacres. It appears that his Grace, on return from active service, found that the confined air of an ordinary bed-room engendered insomnia. He therefore conceived the idea of sleeping in the open-air and caused his bed to be placed in the centre of the Strand, opposite the entrance to the Savoy Hotel. The presence of the sleeping nobleman might have been unnoticed, had not Mr. SMILLIE chanced to pass the spot on his way from dining after a session of the Coal Commission. His eye was immediately caught by the ducal crest on the panels of the bed. Suspicious that this was a dastardly attempt on the part of a member of the landed classes to obtain sleeping-rights in a public thoroughfare, Mr. SMILLIE lodged a complaint with the police, and the Duke was removed to Bow Street.

Some mild interest has been displayed by the public in a camp which has been established by three subalterns in the roadway at the corner of Charing Cross and Northumberland Avenue. It is a small and quite inconspicuous affair, consisting merely of an army pattern bell-tent, a camp fire and a few deck chairs. Our representative recently visited the occupants to ascertain the reason for their presence. After hastily declining an offer of a glass of E.F.C. port, smuggled over from France, he inquired with polite interest whether his hosts contemplated a lengthy stay. They replied that they did. They were waiting for their demobilisation gratuities. The locality, they added, was a quiet one, where advancing old age could be met in comfortable meditation. Also the offices of Messrs. Cox, Box & Co., the Regimental Agents, were in convenient proximity, and the latest news of the gratuities could be obtained with a minimum of trouble. Up to the present the police have not interfered with them, apparently taking them for workmen employed in repairing the roadway.

"KISSING TIME."

For an infrequent worshipper at the shrine of Musical Comedy the atmosphere of a first night at a new, or renascent, theatre is perhaps rather too heady. There are so many potent vintages set on the board; so many connoisseurs who will offer to tell you beforehand of the merits of their favourite brands.

I confess, to my shame, that when an actor with whose gifts I am unfamiliar is received on his entrance with a storm of applause, I am not prejudiced, as I ought to be, in his favour. On the contrary I follow his performance the more judicially, and if I cannot find that it corresponds to his apparent reputation I am apt (wrongly again) to conclude that the fault lies with him and not with myself.

THE OLD GAIETY IN A NEW

HOME.

THE OLD GAIETY IN A NEW

HOME.But in the case of Kissing Time, after a rather dull First Act, during which I kept telling myself that I was not suffering from senile decay, I had to admit that the gods were in a great measure justified of their elect. For one thing the authors, taking a bold and original line (from the French), had produced a coherent plot; and both dialogue and lyrics were above what I understand to be the average in this kind. One expects, of course, a little Cockney licence—"pyjamas" rhymed with "Palmer's," and so on—and a certain amount of popular banality, as in the song, "Some Day" (rapturously approved); but there were excellent verses on the text, "A woman has no mercy on a man," and, I doubt not, much other good stuff which I missed because Mr. IVAN CARYLL, who conducted (and was probably thinking more of his own pleasant music than somebody else's words), did not make enough allowance for my slowness in the up-take of patter.

Mr. LESLIE HENSON was funny, and should be funnier still when the book has been cut down by about an hour and space allowed him for private developments. Miss PHYLLIS DARE was graceful and confident. One easily understood her popularity; but Miss YVONNE ARNAUD, who was a little slow for the general pace, must, I think, be more of an acquired taste.

Mr. TOM WALLS (very svelte in his French uniform) did sound work, and so did Mr. GEORGE BARRETT, a humourist by gift of nature. Mr. GEORGE GROSSMITH, who with Mr. LAURILLARD has made out of the old Middlesex a most attractive and spacious "Winter Garden," brought with him the traditions of the Gaiety, and had a warm personal welcome. I could bear him to be funnier than he was; but as I'm sure that he's clever enough to be anything he likes I can only assume that he wasn't really trying.

I join everybody in wishing him good cheer in this "garden" of his, where, if the auguries fulfil themselves, he is not likely, even in the dog-days, to have to endure "the winter of our discontent."

I know a spot where balmy air and still

Enfolds the placid dweller hour by hour

As, all unhampered in his tranquil bower,

He stretches idle limbs at ease until

The blessed peace about him calms his will

And hidden thoughts, expanding into flower,

Amaze him with their beauty, and the sour

Sharp voice of Care, that sounds far off and shrill,

Moves him to gentle mirth that men can be

So strangely foolish as to heed her call,

Regardless of their true felicity....

Avoid the place, ye bores. Aroint ye all!

Afflict not one to this dear haven fled,

My private earthly paradise—my BED.

"Quarrymen (experienced) Wanted, wages 1s. 5-1/2d. per hour; constant employment for good men. No bankers need apply."—Country Paper.

Why this marked discrimination against bankers? We have known several who were most respectable.

The unexampled rapidity with which, owing to the opportunities of war-time, men in all walks of life have reached the top of the tree in early manhood is leading on to strange but inevitable results. Unable to rise any higher they are already contemplating the heroic course of justifying their eminence by starting afresh at the bottom of the ladder.

The crucial and classical example is, of course, furnished by our Boy Chancellor. It is an open secret that, with that sagacious foresight which has always characterised him, Lord BIRKENHEAD recognises the impermanency of his exalted position and is resolved when and if he leaves the Woolsack to resume practice as a Junior. It is further rumoured that some of our judges intend to follow his august example. The atmosphere of the Bench is not always exhilarating, and the salary is fixed. But a self-effacing altruism doubtless also enters into their motives.

The impending exodus from Whitehall is another factor in the situation. Scores of demobilised "Ministerial angels" will soon be released, and are meditating fresh outlets for their benevolent energies. Many of them are young and some beautiful. The romance of commerce and of the stage will prove a potent lure. Never has the demand for an elegant deportment and urbane manners in our great shops and stores been more clamant; never has the standard been higher. Our ex-officials may have to stoop, but it will be to conquer. We can confidently look forward to the day when no shop will be without its DEMOSTHENES, ALCIBIADES or its CICERO. Opportunities for employment on the stage are likely to be multiplied by the alleged intention of several actor-managers to enter Parliament, while others, nobly anxious to satisfy the claims of youth, have expressed their resolve only to appear henceforth in such subsidiary parts as dead bodies and outside shouts.

In the domain of letters some startling developments are also threatened on similar lines. Mr. WELLS, always remarkable for his refusal to commit himself to any finality in the formulation of his opinions, has, it is said, decided to devote his talents in future exclusively to the composition of educational works in words of one syllable, and where possible of three letters. He is also contemplating a revised and simplified edition of his novels, beginning with Mr. Brit Sees It Thro'. Mr. SHAW'S fresh start will be the greatest surprise of all. He intends to go to Eton and Oxford, and, as a don, to combat the tide of Socialism at our older Universities. Mr. BELLOC, it is reported, has re-enlisted in the French Artillery, and Mr. ARNOLD BENNETT has accepted a commission in the Dutch mercantile marine.

The future of Mr. ASQUITH has given rise to a good deal of speculation in the Press, but we are in a position to state that he does not intend to re-enter politics or to resume his practice at the Bar, but has resolved to return to his first love—journalism. Sport is the only department in which the ornate and orotund style of which Mr. ASQUITH is a master is still in vogue, and the description of classic events in classical diction will furnish him with a congenial opening for the exercise of his great literary talent.

The rumour that Mr. BALFOUR, on his retirement from the post of Foreign Secretary, will take up the arduous duties of caddie-master at St. Andrew's is not yet fully confirmed. Meanwhile he is known to be considering the alternative offer of the secretaryship to the Handel Society. In this context it is interesting to hear that, according to a Rotterdam agency, Sir EDWARD ELGAR has just completed a series of pieces for the mouth-organ, dedicated to Sir LEO CHIOZZA MONEY, which will, it is hoped, be shortly heard in the luncheon interval at the Coal Commission.

"EXCUSE ME, OFFICER, BUT HAVE YOU SEEN ANY PICKPOCKETS ABOUT HERE WITH A HANDKERCHIEF MARKED 'SUSAN'?"

DEAR ALEC,—Jolly glad to hear you're coming home. I beat you after all, though. I suppose I was looking particularly pivotal when I saw the D.O., because he let me through at once.

Will you go back to the Governor's office?

Yours ever, GARRY NORTON.

DEAR GARRY,—Haven't the faintest; but before settling down I'm going to have a week or two, either sailing or fishing, so as to try to shed the army feeling, and I think you'd better come with me. I've saved no end of shekels, and I'm going to give old Cox a run for his money (the bit that's mine, I mean, that he's been keeping for me).

If you can find a likely craft, mop her up for me, old bean, and we'll have a hairy time somewhere on the S.W. coast.

Yours in haste, ALEC RIDLEY.

DEAR ALEC,—I wish you'd be less vague. What sort of a boat do you want—schooner, yawl, cutter or spoonbill? A half-decker, or the full five quires to the ream? Give me definite instructions and I'll do my best to carry them out. I'm afraid I can't get off, so you'll have to take someone else, or incarnadine the seas by yourself.

Yours as ever, GARRY.

DEAR GARRY,—Sorry to hear you can't come. Any kind of a boat that will go without bouncing too high will do, and if it has a rudder, a couple of starboard tacks, bath and butler's pantry so much the better. I mean to wash out the memory of those nine months at Basra last year with the flies.

Yours, ALEC.

DEAR ALEC,—What you want, my lad, is a houseboat, and I doubt whether you'll get one during this shortage of residential property.

I should try fishing if I were you. In fact I have taken a bit of water for you in Chamshire. I haven't seen it, but am told it's very all right and only twenty pounds till the 10th of June.

Yours ever, GARRY NORTON.

DEAR GARRY,—This is a top-hole place. To have got this water for so little you 're absolutely the Senior Wangler.

You might send me some mayflies, old dear; about half a pint I shall want, judging from the infernal number of bushes on the river banks here. Mr. MILLS's bombs have put me right off my cast and I can't do the old Shimmy shake either somehow. I can hear the click of croquet balls in the Vicarage garden as I write, so the hooping season has begun.

There's one other chap staying in the pub. Talks and dresses like a War profiteer. Seems to be doing nothing but loafing about at present.

Yours ever, ALEC.

Postcard.

Have ordered the mayflies and will send them soon as poss. G. N.

DEAR GARRY,—Thanks for yours. Not so anxious about mayflies now, but should be glad if you would send me a pound or two of the best chocolates. Having good sport.

In haste for post,

Yours, ALEC.

DEAR ALEC,—I enclose a couple of pounds of extra special chocolates, but didn't know they were included in the Angler's Pharmacopoeia.

Glad you are having good sport and justifying my choice of water.

Yours as usual, GARRY.

DEAR GARRY,—Thanks for chocs. The Vicar called the other day, and I have caught several cups of tea on the recoil at the Vicarage since. Miss Stevenson, his ewe-lamb, is A1, and we have had some splendid sport together. We caught eleven beauties yesterday; one was over 19-1/2 inches.

Post just going out.

Yours in haste, ALEC.

P.S.—Another couple of pounds of chocs would be useful.

DEAR ALEC,—-Awfully glad to hear the fishing is so good. I shall expect a brace of good long trout for breakfast one of these days.

Yours, GARRY.

DEAR GARRY,—Who said anything about fish? I sub-let the water (at a profit) to the War-profiteer three days after arriving.

Miss Stevenson, with a brace of bouncing terriers, is outside whistling for me, so I must put the lid on.

Yours, ALEC.

DEAR ALEC,—What's the idea? You say you let the fishing a fortnight ago; but last Wednesday you wrote about catching eleven beauties, one over nineteen and a half inches long. Some trout—what? But why the terriers?

Yours in darkness,

Postcard. Rats. ALEC.

"When Greek Joins Greek."

"The Red Cross announces that the repatriation of Greeks forcibly removed from their homes in Eastern Macedonia has been virtually completed despite Bulgarian opposition. The reports says the Greek Red Cross rendered invaluable aid in looting imprisoned Greeks hidden remotely."—Egyptian Gazette.

When first I joined the R.N.V.

And ventured out upon the sea,

The war-tried Subs. R.N. and Looties

Who guided me about my duties

Were wont to wink and chuckle if

I found the going rather stiff;

And when, upon the Nor'-East Rough,

My legs proved scarcely firm enough

To keep me yare and head-to-wind

The very nicest of them grinned.

Now times are changed, and here I am

Once more beside the brimming Cam,

Where lo, those selfsame Loots and Subs

Whirl madly by in punts and tubs,

Which they propel by strength of will

And muscle rather more than skill.

For (if one may be fairly frank)

They barge across from bank to bank,

With zig-zag motions, in and out,

As though torpedoes were about;

Whilst I with all an expert's ease

Glide by as gaily as you please,

Or calmly, 'mid the rout of punts,

Perform accomplished super-stunts.

But do not think I jibe or jeer

However strangely they career.

In soothing accents, sweet as spice,

I offer them my best advice,

Or deftly show them how to plant a

Propulsive pole in oozy Granta,

Observing, "If you only knew it

This is the proper way to do it;"

Till soon each watching Looty's face

Grows full of wonder at my grace,

And daring Subs in frail Rob Roys

Attempt to imitate my poise.

O war-tried Loots and Subs. R.N.,

Thus by the Cam we meet again;

And, as in wilder sterner days,

We shared the ocean's dreary ways

In fellowship of single aim,

I never doubt we'll do the same

By sunny Cam in happier times;

And therefore, if through these my rhymes

Some gentle banter slyly flits,

Forgive me, Sirs—and call it quits.

From a club journal:—

"Members will look forward to the River Trip this year as a change from a Trip to the River."

This constant craving for variety is one of the most unhealthy symptoms of the times in which we live.

From a report of the debate on the National Shipyards:—

"'The Mercantile Marine was our weakest front. If the sinking increased our unbiblical cord would be cut' (a graphic phrase this)."—Provincial Paper.

Graphic, perhaps, but hardly stenographic.

Poacher (to gamekeeper who has been chasing him for twenty minutes). "NOW, SONNY, IF YOU'VE 'AD A GOOD REST WE'LL SET OFF AGAIN."

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

MR. E.F. BENSON, seizing occasion as it flies, has given us, in Across the Stream (MURRAY), a story on the very topical subject of spiritualism and communication with the dead. As a practised novelist, with a touch so sure that it can hardly fail to adorn, he has made a tale that is interesting throughout and here and there aspires to real beauty of feeling; though not all the writer's skill can disguise a certain want of unity in the natural and supernatural divisions of his theme. The early part of the book, which tells of the boyhood of Archie and the attempts of his dead brother Martin to "get through" to him, are admirably done. As always in these studies of happy and guarded childhood, Mr. BENSON is at his best, sympathetic, tender, altogether winning. There was lung trouble in Archie's record—Martin indeed had died of it (sometimes I wonder whether any of Mr. BENSON'S protagonists can ever be wholly robust), and there is a genuine thrill in the scene at the Swiss sanatorium, where the dead and living boys touch hands over the little cache of childish treasure buried by the former beneath a pine-tree in the garden. Later, when Archie had recovered from his disease and grown to suitor's estate, I could not but feel, despite the sardonically observed figure of Helena, the detestable girl who nearly ruins him, that the whole affair had become conventional, and by so much lost interest for its creator. Apart, however, from the bogie chapters of Possession (which I shall not further indicate) the most moving scenes in this latter part are those between Archie and his father. I have seldom known a horrible situation handled with more delicate art; it is for this, rather than for its slightly unconvincing devilments, that I would give the book an honourable place in the ranks of Bensonian romance.

I quite agree with Mr. HAROLD BEGBIE, whose Mr. Sterling Sticks it Out (HEADLEY) is a generous attempt to put into the form of a story the case of the conscientious objector of the finest type, that, when we are able to think about this matter calmly, we shall have considerable misgivings at least about details in our treatment of this difficult problem. I also agree that the officials of the Press Bureau don't come at all well out of the correspondence which he prints in his preface, and, further, that the Government ought to have had the courage to alter the law allowing absolute exemption rather than stretch it beyond the breaking point. But I emphatically dispute his assumption that the matter was a simple one. It was not the saintly, single-minded and sweet-natured C.O.'s of Christopher Sterling's type that made the chief difficulty. There were few of this literal interpretation and heroic texture. The real difficulty was created by men of a very different character and in much greater numbers, sincere in varying degrees, but deliberately, passionately and unscrupulously obstructive, bent on baulking the national will and making anything like reasonable treatment of them impossible. It would require saints, not men, to deal without occasional lapses from strict equity with such infuriating folk. Mr. BEGBIE'S book is unfair in its emphasis, but it is not [pg 432] fanatical or subversive, and I can see no decent reason why it should have been banned. I certainly commend it to the majority-minded as a wholesome corrective.

That the reviewer should finish his study of the assembled biographies of twenty-four fallen heroes of this War with a feeling of disappointment and some annoyance argues a fault in the biographer or in the reviewer. I invite the reader to be the judge between us, for The New Elizabethans (LANE) must certainly be read, if only to understand clearly that there is no fault in the heroes, at any rate. Mr. E.B. OSBORN describes them as "these golden lads ... who first conquered their easier selves and secondly led the ancestral generations into a joyous captivity" (whatever that may mean), and maintains, against the father of one of them apparently, that he is apt in the title he has given to them and to their countless peers. I agree with the father and think they deserve a new name of their own; such men as the GRENFELL brothers, HUGH and JOHN CHARLTON and DONALD HANKEY did more than maintain a tradition. There is about DIXON SCOTT, "the Joyous Critic," something, I think, which will be recognised as marking a production and a surprise of our own generation—the "ink-slinger" who, when it came to the point, was found equally reckless and brave in slinging more dangerous matter. Again, I feel that there is needed a clearer motive than is apparent to warrant "a selection of the lives of young men who have fallen in the great war." Selections in this instance are more odious than comparisons; there should be one book for one hero. Thirdly, I disapprove the dedication to the Americans; and, lastly, I found in the author's prose a certain affectation that is unworthy of the subject-matter. An instance is the reference to HARRY BUTTERS' "joyous" quotation of the quatrain:—

Every day that passes

Filling out the year

Leaves the wicked Kaiser

Harder up for beer.

I like the quatrain, of course; who, knowing the "Incorrigibles," doesn't? But I did not like that reiterated word "joyous."

I should certainly have supposed that recent history had discounted popular interest in the monarchies of make-believe; in other words, that when real sovereigns have been behaving in so sensational a manner one might expect a slump in counterfeits. But it appears that Mr. H.B. MARRIOTT WATSON is by no means of this opinion. His latest story, The Pester Finger (SKEFFINGTON), shows him as Ruritanian as ever. As usual we find that distressful country, here called Varavia, in the throes of dynastic upheaval, which centres, in a manner also not without precedent, in the figure of a young and beautiful Princess. This lady, the last of her race, had been adopted as ward—on, I thought, insufficient introduction—by the hero, Sir Francis Vyse. The situation was further complicated by the fact that in his youth he had been the officer of the guard who ought to have prevented the murder of Sonia's august parents, and didn't. Quite early I gave up counting how many times Sir Francis and his fair ward were set upon, submerged, imprisoned and generally knocked about. You never saw so convulsed a courtship; for I will no longer conceal the fact that, when he was not more strenuously engaged, he soon began to regard Sonia with a softening eye. And as Sonia herself was growing up to womanhood, or, in Mr. WATSON'S elegant phrase, "muliebrity claimed her definitely"—well, he is an enviable reader for whom the last page will hold any considerable surprise.

"ETIENNE," in an introductory note to A Naval Lieutenant, 1914-1918 (METHUEN), gives an excellent reason for wishing to record his impressions of the "sea affair." He was in H.M.S. Southampton during the earlier part of the War, and "on all the four principal occasions when considerable German forces were encountered in the North Sea, her guns were in action." Very naturally he desired to do honour to this gallant light cruiser, and I admire prodigiously the modest way in which he has done it. "ETIENNE" is not a stylist; a professor of syntax might conceivably be distressed by his confusion of prepositions; but apart from this detail all is plain sailing—and fighting. I have read no more thrilling account of the Battle of Jutland than is to be found here. The author does it so well because he tells his story with great simplicity and without what I believe he would call "windiness." Best of all, he has a nice sense of humour, and would even, I believe, have discovered the funny side of Scapa, if there had been one. "ETIENNE," whose short stories of naval life were amusing, makes a distinct advance in this new work.

GOLF IN SPRINGTIME.

Merry little baa-lambs sporting on the grass,

Playing ring-a-roses, dancing as you pass,

Crying,

"Jones has topped his brassie shot! What a way to play!

Now then, all together, boys—Me-e-eh!"

Pretty little woollies, white as driven snow,

Following your mothers, skipping as you go,

Crying,

"Jones is in the bunker! What a lot he has to say!

Give it all together, boys—Me-e-e-eh!"

Harbingers of Springtime! innocently fair,

Frisking on the greensward, leaping in the air,

Crying,

"Jones is in the whins again! He's off his drive to-day;

Once more let him have it, boys—Me-e-e-e-eh!"

Silly little baa-lambs! If you only knew,

One day you'll be fatter and I'll have the laugh on you,

Crying,

"Every time I foozled they bleated with delight.

Now they're lamb-and-mint-sauce. Serves the beggars right!"

ALGOL.

"WHAT DO YOU MEAN BY HANGING ON BEHIND ME LIKE THAT?"

"I'VE BROKEN MY HORN, OLD TOFF, AND I THOUGHT YOU COULD TOOT FOR TWO."