Title: Frank, the Young Naturalist

Author: Harry Castlemon

Release date: May 1, 2004 [eBook #12405]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/12405

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Asad Razzaki and PG Distributed

Proofreaders

FRANK, THE YOUNG NATURALIST,

FRANK ON A GUN-BOAT,

FRANK IN THE WOODS,

FRANK ON THE PRAIRIE,

FRANK BEFORE VICKSBURG,

FRANK ON THE LOWER MISSISSIPPI.

CHAPTER I.

THE HOME OF THE YOUNG NATURALIST

CHAPTER IV.

A RACE ON THE WATER

CHAPTER V.

A FISHING EXCURSION

CHAPTER VIII.

HOW TO SPEND THE "FOURTH"

CHAPTER IX.

THE COAST-GUARDS OUTWITTED

CHAPTER XII.

A DUCK-HUNT ON THE WATER

CHAPTER XIV.

BILL LAWSON'S REVENGE

CHAPTER XVI.

A CHAPTER OF INCIDENTS

CHAPTER XVII.

THE GRAYHOUND OUTGENERALED

About one hundred miles north of Augusta, the Capital of Maine, the little village of Lawrence is situated. A range of high hills skirts its western side, and stretches away to the north as far as the eye can reach; while before the village, toward the east, flows the Kennebec River.

Near the base of the hills a beautiful stream, known as Glen's Creek, has its source; and, after winding through the adjacent meadows, and reaching almost around the village, finally empties into the Kennebec. Its waters are deep and clear, and flow over a rough, gravelly bed, and under high banks, and through many a little nook where the perch and sunfish love to hide. This creek, about half a mile from its mouth, branches off, forming two streams, the smaller of which flows south, parallel with the river for a short distance, and finally empties into it. This stream is known as Ducks' Creek, and it is very appropriately named; for, although it is but a short distance from the village, every autumn, and until late in the spring, its waters are fairly alive with wild ducks, which find secure retreats among the high bushes and reeds which line its banks. The island formed by these two creeks is called Reynard's Island, from the fact that for several years a sly old fox had held possession of it in spite of the efforts of the village boys to capture him. The island contains, perhaps, twenty-five acres, and is thickly covered with hickory-trees; and there is an annual strife between the village boys and the squirrels, to see which can gather the greater quantity of nuts.

Directly opposite the village, near the middle of the river, is another island, called Strawberry Island, from the great quantity of that fruit which it produces.

The fishing-grounds about the village are excellent. The river affords great numbers of perch, black bass, pike, and muscalonge; and the numberless little streams that intersect the country fairly swarm with trout, and the woods abound in game. This attracts sportsmen from other places; and the Julia Burton, the little steamer that plies up and down the river, frequently brings large parties of amateur hunters and fishermen, who sometimes spend months enjoying the rare sport.

It was on the banks of Glen's Creek, about half a mile from the village, in a neat little cottage that stood back from the road, and which was almost concealed by the thick shrubbery and trees that surrounded it, that FRANK NELSON, the young naturalist, lived. His father had been a wealthy merchant in the city of Boston; and, after his death, Mrs. Nelson had removed into the country with her children, and bought the place of which we are speaking. Frank was a handsome, high-spirited boy, about sixteen years of age. He was kind, open-hearted, and generous; and no one in the village had more friends than he. But his most prominent characteristic was perseverance. He was a slow thinker, and some, perhaps, at first sight, would have pronounced him "dull;" but the unyielding application with which he devoted himself to his studies, or to any thing else he undertook, overcame all obstacles; and he was further advanced, and his knowledge was more thorough than that of any other boy of the same age in the village. He never gave up any thing he undertook because he found it more difficult than he had expected, or hurried over it in a "slipshod" manner, for his motto was, "Whatever is worth doing at all, is worth doing well."

At the time of which we write Frank was just entering upon what he called a "long vacation." He had attended the high-school of which the village boasted for nearly eight years, with no intermission but the vacations, and during this time he had devoted himself with untiring energy to his studies. He loved his books, and they were his constant companions. By intense application he succeeded in working his way into the highest class in school, which was composed of young men much older than himself, and who looked upon him, not as a fellow-student, but as a rival, and used every exertion to prevent him from keeping pace with them. But Frank held his own in spite of their efforts, and not unfrequently paid them back in their own coin by committing his lessons more thoroughly than they.

Things went on so for a considerable time. Frank, whose highest ambition was to be called the best scholar in his class, kept steadily gaining ground, and one by one the rival students were overtaken and distanced. But Frank had some smart scholars matched against him, and he knew that the desired reputation was not to be obtained without a fierce struggle; and every moment, both in and out of school, was devoted to study.

He had formerly been passionately fond of rural sports, hunting and fishing, but now his fine double-barrel gun, which he had always taken especial care to keep in the best possible "shooting order," hung in its accustomed place, all covered with dust. His fishing-rod and basket were in the same condition; and Bravo, his fine hunting-dog, which was very much averse to a life of inactivity, made use of his most eloquent whines in vain.

At last Frank's health began to fail rapidly. His mother was the first to notice it, and at the suggestion of her brother, who lived in Portland, she decided to take Frank out of school for at least one year, and allow him but two hours each day for study. Perhaps some of our young readers would have been very much pleased at the thought of so long a respite from the tiresome duties of school; but it was a severe blow to Frank. A few more months, he was confident, would have carried him ahead of all competitors. But he always submitted to his mother's requirements, no matter how much at variance with his own wishes, without murmuring; and when the spring term was ended he took his books under his arm, and bade a sorrowful farewell to his much-loved school-room.

It is June, and as Frank has been out of school almost two months, things begin to wear their old, accustomed look again. The young naturalist's home, as his schoolmates were accustomed to say, is a "regular curiosity shop." Perhaps, reader, if we take a stroll about the premises, we can find something to interest us.

Frank's room, which he called his "study," is in the south wing of the cottage. It has two windows, one looking out toward the road, and the other covered with a thick blind of climbing roses, which almost shut out the light. A bookcase stands beside one of the windows, and if you were to judge from the books it contained, you would pronounce Frank quite a literary character. The two upper shelves are occupied by miscellaneous books, such as Cooper's novels, Shakspeare's works, and the like. On the next two shelves stand Frank's choicest books—natural histories; there are sixteen large volumes, and he knows them almost by heart. The drawers in the lower part of the case are filled on one side with writing materials, and on the other with old compositions, essays, and orations, some of which exhibit a power of imagination and a knowledge of language hardly to be expected in a boy of Frank's age. On the top of the case, at either end, stand the busts of Clay and Webster, and between them are two relics of Revolutionary times, a sword and musket crossed, with the words "Bunker Hill" printed on a slip of paper fastened to them. On the opposite side of the room stands a bureau, the drawers of which are filled with clothing, and on the top are placed two beautiful specimens of Frank's handiwork. One is a model of a "fore-and-aft" schooner, with whose rigging or hull the most particular tar could not find fault. The other represents a "scene at sea." It is inclosed in a box about two feet long and a foot and a half in hight. One side of the box is glass, and through it can be seen two miniature vessels. The craft in the foreground would be known among sailors as a "Jack." She is neither a brig nor a bark, but rather a combination of both. She is armed, and the cannon can be seen protruding from her port-holes. Every sail is set, and she seems to be making great exertion to escape from the other vessel, which is following close in her wake. The flag which floats at her peak, bearing the sign of the "skull and cross-bones," explains it all: the "Jack" is a pirate; and you could easily tell by the long, low, black hull, and tall, raking masts that her pursuer is a revenue cutter. The bottom of the box, to which the little vessels are fastened in such a manner that they appear to "heel" under the pressure of their canvas, is cut out in little hollows, and painted blue, with white caps, to resemble the waves of the ocean; while a thick, black thunder-cloud, which is painted on the sides of the box, and appears to be rising rapidly, with the lightning playing around its ragged edges, adds greatly to the effect of the scene.

At the north end of the room stands a case similar to the one in which Frank keeps his books, only it is nearly twice as large. It is filled with stuffed "specimens"—birds, nearly two hundred in number. There are bald eagles, owls, sparrows, hawks, cranes, crows, a number of different species of ducks, and other water-fowl; in short, almost every variety of the feathered creation that inhabited the woods around Lawrence is here represented.

At the other end of the room stands a bed concealed by curtains. Before it is a finely carved wash-stand, on which are a pitcher and bowl, and a towel nicely folded lies beside them. In the corner, at the foot of the bed, is what Frank called his "sporting cabinet." A frame has been erected by placing two posts against the wall, about four feet apart; and three braces, pieces of board about six inches wide, and long enough to reach from one post to the other, are fastened securely to them. On the upper brace a fine jointed fish-pole, such as is used in "heavy" fishing, protected by a neat, strong bag of drilling, rests on hooks which have been driven securely into the frame; and from another hook close by hangs a large fish-basket which Frank, who is a capital fisherman, has often brought in filled with the captured denizens of the river or some favorite trout-stream. On the next lower brace hang a powder-flask and shot-pouch and a double-barrel shot-gun, the latter protected from the damp and dust by a thick, strong covering. On the lower brace hang the clothes the young naturalist always wears when he goes hunting or fishing—a pair of sheep's-gray pantaloons, which will resist water and dirt to the last extremity, a pair of long boots, a blue flannel-shirt, such as is generally worn by the sailors, and an India-rubber coat and cap for rainy weather. A shelf has been fastened over the frame, and on this stands a tin box, which Frank calls his "fishing-box." It is divided into apartments, which are filled with fish-hooks, sinkers, bobbers, artificial flies, spoon-hooks, reels, and other tackle, all kept in the nicest order.

Frank had one sister, but no brothers. Her name was Julia. She was ten years of age; and no boy ever had a lovelier sister. Like her brother, she was unyielding in perseverance, but kind and trusting in disposition, willing to be told her faults that she might correct them. Mrs. Nelson was a woman of good, sound sense; always required implicit obedience of her children; never flattered them, nor allowed others to do so if she could prevent it. The only other inmate of the house was Aunt Hannah, as the children called her. She had formerly been a slave in Virginia, and, after years of toil, had succeeded in laying by sufficient money to purchase her freedom. We have already spoken of Frank's dog; but were we to allow the matter to drop here it would be a mortal offense in the eyes of the young naturalist, for Bravo held a very prominent position in his affections. He was a pure-blooded Newfoundland, black as jet, very active and courageous, and there was nothing in the hunting line that he did not understand; and it was a well-established saying among the young Nimrods of the village, that Frank, with Bravo's assistance, could kill more squirrels in any given time than any three boys in Lawrence.

Directly behind the cottage stands a long, low, neatly constructed building, which is divided by partitions into three rooms, of which one is used as a wood-shed, another for a carpenter's shop, and the third is what Frank calls his "museum." It contains stuffed birds and animals, souvenirs of many a well-contested fight. Let us go and examine them. About the middle of the building is the door which leads into the museum, and, as you enter, the first object that catches your eye is a large wild-cat, crouched on a stand which is elevated about four feet above the floor, his back arched, every hair in his body sticking toward his head, his mouth open, displaying a frightful array of teeth, his ears laid back close to his head, and his sharp claws spread out, presenting altogether a savage appearance; and you are glad that you see him dead and stuffed, and not alive and running at liberty in the forest in the full possession of strength. But the young naturalist once stood face to face with this ugly customer under very different circumstances.

About forty miles north of Lawrence lives an old man named Joseph Lewis. He owns about five hundred acres of land, and in summer he "farms it" very industriously; but as soon as the trapping season approaches he leaves his property to the care of his hired men, and spends most of the time in the woods. About two-thirds of his farm is still in its primeval state, and bears, wild-cats, and panthers abound in great numbers. The village boys are never more delighted than when the winter vacation comes, and they can gain the permission of their parents to spend a fortnight with "Uncle Joe," as they call him.

The old man is always glad to see them, and enlivens the long winter evenings with many a thrilling story of his early life. During the winter that had just passed, Frank, in company with his cousin Archie Winters, of whom more hereafter, paid a visit to Uncle Joe. One cold, stormy morning, as they sat before a blazing fire, cracking hickory-nuts, the farmer burst suddenly into the house, which was built of logs, and contained but one room, and commenced taking down his rifle.

"What's the matter, Uncle Joe?" inquired Archie.

"Matter!" repeated the farmer; "why, some carnal varmint got into my sheep-pen last night, and walked off with some of my mutton. Come," he continued, as he slung on his bullet-pouch, "let's go and shoot him."

Frank and Archie were ready in a few minutes; and, after dropping a couple of buck-shot into each barrel of their guns, followed the farmer out to the sheep-pen. It was storming violently, and it was with great difficulty that they could find the "varmint's" track. After half an hour's search, however, with the assistance of the farmer's dogs, they discovered it, and began to follow it up, the dogs leading the way. But the snow had fallen so deep that it almost covered the scent, and they frequently found themselves at fault. After following the track for two hours, the dogs suddenly stopped at a pile of hemlock-boughs, and began to whine and scratch as if they had discovered something.

"Wal," said Uncle Joe, dropping his rifle into the hollow of his arm, "the hounds have found some of the mutton, but the varmint has took himself safe off."

The boys quickly threw aside the boughs, and in a few moments the mangled remains of one of the sheep were brought to light. The thief had probably had more than enough for one meal, and had hidden the surplus carefully away, intending, no doubt, to return and make a meal of it when food was not quite so plenty.

"Wal, boys," said the farmer, "no use to try to foller the varmint any further. Put the sheep back where you found it, and this afternoon you can take one of your traps and set it so that you can ketch him when he comes back for what he has left." So saying, he shouldered his rifle and walked off, followed by his hounds.

In a few moments the boys had placed every thing as they had found it as nearly as possible, and hurried on after the farmer.

That afternoon, after disposing of an excellent dinner, Frank and Archie started into the woods to set a trap for the thief. They took with them a large wolf-trap, weighing about thirty pounds. It was a "savage thing," as Uncle Joe said, with a powerful spring on each side, which severely taxed their united strength in setting it; and its thick, stout jaws, which came together with a noise like the report of a gun, were armed with long, sharp teeth; and if a wolf or panther once got his foot between them, he might as well give up without a struggle. Instead of their guns, each shouldered an ax. Frank took possession of the trap, and Archie carried a piece of heavy chain with which to fasten the "clog" to the trap. Half an hour's walk brought them to the place where the wild-cat had buried his plunder. After considerable exertion they succeeded in setting the trap, and placed it in such a manner that it would be impossible for any animal to get at the sheep without being caught. The chain was them fastened to the trap, and to this was attached the clog, which was a long, heavy limb. Trappers, when they wish to take such powerful animals as the bear or panther, always make use of the clog. They never fasten the trap to a stationary object. When the animal finds that he is caught, his first impulse is to run. The clog is not heavy enough to hold him still, but as he drags it through the woods, it is continually catching on bushes and frees, and retarding his progress. But if the animal should find himself unable to move at all, his long, sharp teeth would be put to immediate use, and he would hobble off on three feet, leaving the other in the trap.

After adjusting the clog to their satisfaction, they threw a few handfuls of snow over the trap and chain, and, after bestowing a few finishing touches, they shouldered their axes and started toward the house. The next morning, at the first peep of day, Frank and Archie started for the woods, with their dogs close at their heels. As they approached the spot where the trap had been placed they held their guns in readiness, expecting to find the wild-cat secure. But they were disappointed; every thing was just as they had left it, and there were no signs of the wild-cat having been about during the night. Every night and morning for a week they were regular in their visits to the trap, but not even a twig had been moved. Two weeks more passed, and during this time they visited the trap but once. At length the time allotted for their stay at Uncle Joe's expired. On the evening previous to the day set for their departure, as they sat before the huge, old-fashioned fireplace, telling stories and eating nuts. Uncle Joe suddenly inquired, "Boys, did you bring in your trap that you set for that wild-cat?"

They had not thought of it; they had been hunting nearly every day, enjoying rare sport, and they had entirely forgotten that they had a trap to look after.

"We shall be obliged to let it go until to-morrow," said Frank.

And the next morning, as soon as it was light, he was up and dressed, and shouldering an ax, set out with Brave as a companion, leaving Archie in a sound sleep. It was very careless in him not to take his gun—a "regular boy's trick," as Uncle Joe afterward remarked; but it did not then occur to him that he was acting foolishly; and he trudged off, whistling merrily. A few moments' rapid walking brought him to the place where the trap had been set. How he started! There lay the remains of the sheep all exposed. The snow near it was saturated with blood, and the trap, clog, and all were gone. What was he to do? He was armed with an ax, and he knew that with it he could make but a poor show of resistance against an enraged wild animal; and he knew, too, that one that could walk off with fifty pounds fast to his leg would be an ugly customer to handle. He had left Brave some distance back, digging at a hole in a stump where a mink had taken refuge, and he had not yet come up. If the Newfoundlander had been by his side he would have felt comparatively safe. Frank stood for some minutes undecided how to act. Should he go back to the house and get assistance? Even if he had concluded to do so he would not have considered himself a coward; for, attacking a wounded wild-cat in the woods, with nothing but an ax to depend on, was an undertaking that would have made a larger and stronger person than Frank hesitate. Their astonishing activity and strength, and wonderful tenacity of life, render them antagonists not to be despised. Besides, Frank was but a boy, and although strong and active for his age, and possessing a good share of determined courage that sometimes amounted almost to rashness, it must be confessed that his feelings were not of the most enviable nature. He had not yet discovered the animal, but he knew that he could not be a great distance off, for the weight of the trap and clog would retard him exceedingly; and he judged, from the appearance of things, that he had not been long in the trap; perhaps, at that very moment, his glaring eyes were fastened upon him from some neighboring thicket.

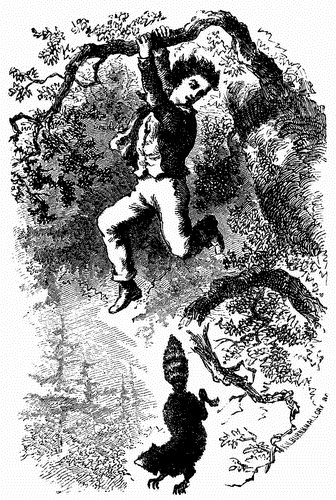

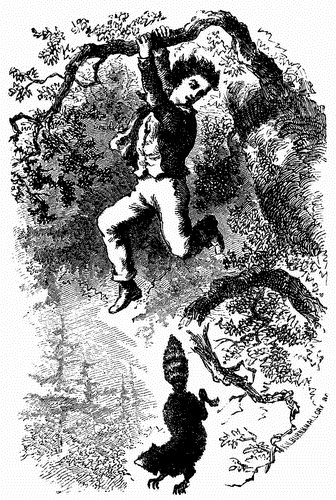

But the young naturalist was not one to hesitate long because there was difficulty or danger before him. He had made up his mind from the first to capture that wild-cat if possible, and now the opportunity was fairly before him. His hand was none of the steadiest as he drew off his glove and placed his fingers to his lips; and the whistle that followed was low and tremulous, very much unlike the loud, clear call with which he was accustomed to let Brave know that he was wanted and he hardly expected that the dog would hear it. A faint, distant bark, however, announced that the call had been heard, and in a few moments Frank heard Brave's long-measured bounds as he dashed through the bushes; and when the faithful animal came in sight, he felt that he had a friend that would stand by him to the last extremity. At this juncture Frank was startled by a loud rattling in the bushes, and the next moment the wild-cat sprang upon a fallen log, not half a dozen rods from the place where he was standing, and, growling fiercely, crouched and lashed his sides with his tail as if about to spring toward him. The trap hung from one of his hind-legs, but by some means he had relieved himself of the clog and chain, and he moved as if the weight of the trap were no inconvenience whatever. The young naturalist was frightened indeed, but bravely stood his ground, and clutched his ax desperately. What would he not have given to have had his trusty double-barrel in his hands! But he was not allowed much time for reflection. Brave instantly discovered the wild-cat, and sprang toward him, uttering an angry growl. Frank raised his ax and rushed forward to his assistance, and cheered on the dog with a voice which, to save his life, he could not raise above a whisper. The wild-cat crouched lower along the log, and his actions seemed to indicate that he intended to show fight. Brave's long, eager bounds brought him nearer and nearer to his enemy. A moment more and he could have seized him; but the wild-cat suddenly turned and sprang lightly into the air, and, catching his claws into a tree that stood full twenty feet distant, ascended it like a streak of light; and, after settling himself between two large limbs, glared down upon his foes as if he were already ashamed of having made a retreat, and had half a mind to return and give them battle. Brave reached the log just a moment too late, and finding his enemy fairly out of his reach, he quietly seated himself at the foot of the tree and waited for Frank to come up.

"Good gracious!" exclaimed the young naturalist, wiping his forehead with his coat-sleeve, (for the exciting scene through which he had just passed had brought the cold sweat from every pore in his body); "it is a lucky circumstance for you and me, Brave, that the varmint did not stand and show fight."

Then ordering the dog to "sit down and watch him," the young naturalist threw down his ax, and started toward the house for his gun. He was still very much excited, fearful that the wild-cat might take it into his head to come down and give the dog battle, in which case he would be certain to escape; for, although Brave was a very powerful and courageous dog, he could make but a poor show against the sharp teeth and claws of the wild-cat. The more Frank thought of it, the more excited he became, and the faster he ran. In a very few moments he reached the house, and burst into the room where Uncle Joe and Archie and two or three hired men sat at breakfast. Frank seemed not to notice them, but made straight across the room toward the place where his shot-gun hung against the wall, upsetting chairs in his progress, and creating a great confusion.

"What in tarnation is the matter?" exclaimed the farmer, rising to his feet.

"I've found the wild-cat," answered Frank, in a scarcely audible voice.

"What's that?" shouted Archie, springing to his feet, and upsetting his chair and coffee-cup.

But Frank could not wait to answer. One bound carried him across the floor and out of the door, and he started across the field at the top of his speed, dropping a handful of buck-shot into each barrel of his gun as he went. It was not until Frank had left the house that Archie, so to speak, came to himself. He had been so astonished at his cousin's actions and the announcement that he had "found the wild-cat," that he seemed to be deprived of action. But Frank had not made a dozen steps from the house before Archie made a dash for his gun, and occasioned a greater uproar than Frank had done; and, not stopping to hear the farmer's injunction to "be careful," he darted out the door, which Frank in his hurry had left open, and started toward the woods at a rate of speed that would have done credit to a larger boy than himself. But Frank gained rapidly on him; and when he reached the tree where the wild-cat had taken refuge, Archie was full twenty rods behind. He found that the animals had not changed their positions. The wild-cat was glaring fiercely down upon the dog as if endeavoring to look him out of countenance; and Brave, seated on his haunches, with his head turned on one side, and his tongue hanging out of the side of his mouth, was steadily returning the gaze. Frank took a favorable position at a little distance from the foot of the tree, and cocking both barrels, so as to be ready for any emergency, in case the first should not prove fatal, raised his gun to his shoulder, and glancing along the clean, brown tube, covered one of the wild-cat's eyes with the fatal sight, and pressed the trigger. There was a sharp report, and the animal fell from his perch stone-dead. At this moment Archie came up. After examining their prize to their satisfaction, the boys commenced looking around through the bushes to find the clog which had been detached from the trap. After some moments' search they discovered it; and Archie unfastened the chain, and shouldering the ax and guns, he started toward the house. Frank followed after, with the wild-cat on his shoulder, the trap still hanging to his leg. The skin was carefully taken off; and when Archie and Frank got home, they stuffed it, and placed it as we now see it.

Let us now proceed to examine the other objects in the museum. A wide shelf, elevated about four feet above the floor, extends entirely around the room, and on this the specimens are mounted. On one side of the door stands a tall, majestic elk, with his head thrown forward, and his wide-spreading antlers lowered, as if he meant to dispute our entrance. On the opposite side is a large black fox, which stands with one foot raised and his ears thrown forward, as if listening to some strange sound. This is the same fox which so long held possession of Reynard's Island; and the young naturalist and his cousin were the ones who succeeded in capturing him. The next two scenes are what Frank calls his "masterpieces." The first is a large buck, running for dear life, closely followed by a pack of gaunt, hungry wolves, five in number, with their sharp-pointed ears laid back close to their heads, their tongues hanging out of their mouths, and their lips spotted with foam The flanks of the buck are dripping with blood from wounds made by their long teeth. In the next scene the buck is at bay. Almost tired out, or, perhaps, too closely pressed by his pursuers, he has at length turned furiously upon them, to sell his life as dearly as possible. Two of the wolves are lying a little distance off, where they have been tossed by the powerful buck, one dead, the other disabled; and the buck's sharp antlers are buried deep in the side of another, which had attempted to seize him.

Well may Frank be proud of these specimens, for they are admirably executed. The animals are neatly stuffed, and look so lifelike and the positions are so natural, that you could almost fancy that you hear the noise of the scuffle. The next scene represents an owl, which, while engaged in one of his nocturnal plundering expeditions, has been overtaken by daylight, and not being able to reach his usual hiding-place, he has taken refuge in a clump of bushes, where he has been discovered by a flock of his inveterate enemies, the crows. The owl sits upon his perch, glaring around with his great eyes, while his tormentors surround him on all sides, their mouths wide open, as if reviling their enemy with all their might. The next scene represents a flock of ducks sporting in the water, and a sly old fox, concealed behind the trunk of a tree close by, is watching their motions, evidently with the intention of "bagging" one of them for his supper. In the next scene he is running off, at full speed, with one of the ducks thrown over his shoulder; and the others, with their mouths open as if quacking loudly, are just rising from the water. In the next scene is a large black wolf, which has just killed a lamb, and crouches over it with open mouth, as if growling fiercely at something which is about to interrupt his feast. The next scene represents a fish-hawk, which has just risen from the lake, with a large trout struggling in his talons; and just above him is a bald-eagle, with his wings drawn close to his body, in the act of swooping down upon the fish-hawk, to rob him of his hard-earned booty. In the next scene a raccoon is attempting to seize a robin, which he has frightened off her nest. The thief had crawled out on the limb on which the nest was placed, intending, no doubt, to make a meal of the bird; but mother Robin, ever on the watch, had discovered her enemy, and flown off just in time to escape. The next scene is a large "dead-fall" trap, nicely set, with the bait placed temptingly within; and before it crouches a sleek marten, peeping into it as if undecided whether to enter or not.

All these specimens have been cured and stuffed by Frank and Archie; and, with the exception of the deer and wolves, they had killed them all. The latter had been furnished by Archie's father. The boys had never killed a deer, and he had promised to take them, during the coming winter with him up into the northern part of the state, where they would have an opportunity of trying their skill on the noble game.

But the museum is not the only thing that has given Frank the name of the "young naturalist." He is passionately fond of pets, and he has a pole shanty behind the museum, which he keeps well stocked with animals and birds. In one cage he has a young hawk, which he has just captured; in another, a couple of squirrels, which have become so tame that he can allow them to run about the shanty without the least fear of their attempting to escape. Then he has two raccoons, several pigeons, kingbirds, quails, two young eagles, and a fox, all undergoing a thorough system of training. But his favorite pets are a pair of kingbirds and a crow, which are allowed to run at large all the time. They do not live on very good terms with each other. In their wild state they are enemies, and each seems to think the other has no business about the cottage; and Frank has been the unwilling witness to many a desperate fight between them, in which the poor crow always comes off second best. Then, to console himself, he will fly upon Frank's shoulder, cawing with all his might, as if scolding him for not lending some assistance. To make amends for his defeat, Frank gives him a few kernels of corn, and then shows him a hawk sailing through the air; and Sam, as he calls the crow, is off in an instant, and, after tormenting the hawk until he reaches the woods, he will always return.

Not a strange bird is allowed to come about the cottage. The kingbirds, which have a nest in a tree close by the house, keep a sharp look-out; and hawks, eagles, crows, and even those of their own species, all suffer alike. But now and then a spry little wren pays a visit to the orchard, and then there is sport indeed. The wren is a great fighting character, continually getting into broils with the other birds, and he has no notion of being driven off; and, although the kingbirds, with Sam's assistance, generally succeed in expelling the intruder, it is only after a hard fight.

Directly opposite the door that opens into the museum is another entrance, which leads into a room which Frank calls his shop. A work-bench has been neatly fitted up in one corner, at the end of which stands a large chest filled with carpenter's tools. On the bench are several half-finished specimens of Frank's skill—a jointed fish-pole, two or three finely-shaped hulls, and a miniature frigate, which he is making for one of his friends. The shop and tools are kept in the nicest order, and Frank spends every rainy day at his bench.

The young naturalist is also a good sailor, and has the reputation of understanding the management of a sail-boat as well as any other boy in the village. He has two boats, which are in the creek, tied to the wharf in front of the house. One of them is a light skiff, which he frequently uses in going to and from the village and on his fishing excursions, and the other is a scow, about twenty feet long and six feet wide, which he built himself. He calls her the Speedwell. He has no sail-boat, but he has passed hour after hour trying to conjure up some plan by which he might be enabled to possess himself of one. Such a one as he wants, and as most of the village have, would cost fifty dollars. Already he has laid by half that amount; but how is he to get the rest? He has begun to grow impatient. The yachting season has just opened; every day the river is dotted with white sails; trials of speed between the swiftest sailers come off almost every hour, and he is obliged to stand and look on, or content himself with rowing around in his skiff. It is true he has many friends who are always willing to allow him a seat in their boats, but that does not satisfy him. He has determined to have a yacht of his own, if there is any honest way for him to get it. For almost a year he has carefully laid aside every penny, and but half the necessary sum has been saved. How to get the remainder is the difficulty. He never asks his mother for money; he is too independent for that; besides, he has always been taught to rely on his own resources, and he has made up his mind that, if he can not earn his boat, he will go without it.

Three or four days after the commencement of our story, Frank might have been seen, about five o'clock one pleasant morning, seated on the wharf in front of the house, with Brave at his side. The question how he should get his boat had been weighing heavily upon his mind, and he had come to the conclusion that something must be done, and that speedily.

"Well," he soliloquized, "my chance of getting a sail-boat this season is rather slim, I'm afraid. But I've made up my mind to have one, and I won't give it up now. Let me see! I wonder how the Sunbeam [meaning his skiff] would sail? I mean to try her. No," he added, on second thought, "she couldn't carry canvas enough to sail with one of the village yachts. I have it!" he exclaimed at length, springing to his feet. "The Speedwell! I wonder if I couldn't make a sloop of her. At any rate, I will get her up into my shop and try it."

Frank, while he was paying a visit to his cousin in Portland, had witnessed a regatta, in which the Peerless, a large, schooner-rigged scow, had beaten the swiftest yachts of which the city boasted; and he saw no reason why his scow could not do the same. The idea was no sooner conceived than he proceeded to put it into execution. He sprang up the bank, with Brave close at his heels, and in a few moments disappeared in the wood-shed. A large wheelbarrow stood in one corner of the shed, and this Frank pulled from its place, and, after taking off the sides, wheeled it down to the creek, and placed it on the beach, a little distance below the wharf. He then untied the painter—a long rope by which the scow was fastened to the wharf—and drew the scow down to the place where he had left the wheelbarrow. He stood for some moments holding the end of the painter in his hand, and thinking how he should go to work to get the scow, which was very heavy and unwieldy, upon the wheelbarrow. But Frank was a true Yankee, and fruitful in expedients, and he soon hit upon a plan, which he was about putting into execution, when a strong, cheery voice called out:

"Arrah, me boy! What'll yer be after doing with the boat?"

Frank looked up and saw Uncle Mike, as the boys called him—a good-natured Irishman, who lived in a small rustic cottage not far from Mrs. Nelson's—coming down the bank.

"Good morning, Uncle Mike," said Frank, politely accepting the Irishman's proffered hand and shaking it cordially. "I want to get this scow up to my shop; but I'm afraid it is a little too heavy for me to manage."

"So it is, intirely," said Mike, as he divested himself of his coat, and commenced rolling up his shirt-sleeves. "Allow me to lend yer a helpin' hand." And, taking the painter from Frank's hand, he drew the scow out of the water, high upon the bank. He then placed his strong arms under one side of the boat, and Frank took hold of the other, and, lifting together, they raised it from the ground, and placed it upon the wheelbarrow. "Now, Master Frank," said Mike, "if you will take hold and steady her, I'll wheel her up to the shop for you."

Frank accordingly placed his hands upon the boat in such a manner that he could keep her steady and assist Mike at the same time; and the latter, taking hold of the "handles," as he termed them, commenced wheeling her up the bank. The load was heavy, but Mike was a sturdy fellow, and the scow was soon at the door of the shop. Frank then placed several sticks of round wood, which he had brought out of the wood-shed, upon the ground, about three feet apart, to serve as rollers, and, by their united efforts, the Speedwell was placed upon her side on these rollers, and in a few moments was left bottom upward on the floor of the shop.

A week passed, and the Speedwell again rode proudly at her moorings, in front of the cottage; but her appearance was greatly changed. A "center-board" and several handy lockers had been neatly fitted up in her, and her long, low hull painted black on the outside and white on the inside; and her tall, raking mast and faultless rigging gave her quite a ship-like appearance.

Frank had just been putting on a few finishing touches, and now stood on the wharf admiring her. It was almost night, and consequently he could not try her sailing qualities that day; and he was so impatient to discover whether or not he had made a failure, that it seemed impossible for him to wait.

While he was thus engaged, he heard the splashing of oars, and, looking up, discovered two boys rowing toward him in a light skiff As they approached, he recognized George and Harry Butler, two of his most intimate acquaintances. They were brothers, and lived about a quarter of a mile from Mrs. Nelson's, but they and Frank were together almost all the time. Harry, who was about a year older than Frank, was a very impulsive fellow, and in a moment of excitement often said and did things for which he felt sorry when he had time to think the matter over; but he was generous and good-hearted, and if he found that he had wronged any one, he never failed to make ample reparation. George, who was just Frank's age, was a jolly, good-natured boy, and would suffer almost any indignity rather than retaliate.

"Well, Frank," said Harry, as soon as they came within speaking distance, "George and I wanted a little exercise, so we thought we would row up and see what had become of you. Why don't you come down and see a fellow? Hallo!" he exclaimed, on noticing the change in the Speedwell's appearance, "what have you been trying to do with your old scow?"

"Why, don't you see?" said Frank. "I've been trying to make a yacht out of her."

"How does she sail?" inquired George.

"I don't know. I have just finished her, and have not had time to try her sailing qualities yet."

"I don't believe she will sail worth a row of pins," said Harry, confidently, as he drew the skiff alongside the Speedwell, and climbed over into her. "But I'll tell you what it is," he continued, peeping into the lockers and examining the rigging, "you must have had plenty of hard work to do in fixing her over. You have really made a nice boat out of her."

"Yes, I call it a first-rate job," said George. "Did you make the sails yourself, Frank?"

"Yes," answered Frank. "I did all the work on her. She ought to be a good sailer, after all the trouble I've had. How would you like to spend an hour with me on the river to-morrow? You will then have an opportunity to judge for yourself."

The boys readily agreed to this proposal, and, after a few moments' more conversation, they got into their skiff and pulled down the creek. The next morning, about four o'clock, Frank awoke, and he had hardly opened his eyes before he was out on the floor and dressing. He always rose at this hour, both summer and winter; and he had been so long in the habit of it, that it had become a kind of second nature with him. Going to the window, he drew aside the curtain and looked out. The Speedwell rode safely at the wharf, gallantly mounting the swells which were raised by quite a stiff breeze that was blowing directly down the creek. He amused himself for about two hours in his shop; and after he had eaten his breakfast, he began to get ready to start on the proposed excursion. A large basket, filled with refreshments, was carefully stowed away in one of the lockers of the Speedwell, the sails were hoisted, the painter was cast off, and Frank took his seat at the helm, and the boat moved from the shore "like a thing of life." The creek was too narrow to allow of much maneuvering, and Frank was obliged to forbear judging of her sailing qualities until he should reach the river. But, to his delight, he soon discovered one thing, and that was, that before the wind the Speedwell was no mean sailer. A few moments' run brought him to Mr. Butler's wharf, where he found George and Harry waiting for him. Frank brought the Speedwell around close to the place where they were standing in splendid style, and the boys could not refrain from expressing their admiration at the handsome manner in which she obeyed her helm. They clambered down into the boat, and seated themselves on the middle thwarts, where they could assist Frank in managing the sails, and in a few moments they reached the river.

"There comes Bill Johnson!" exclaimed George, suddenly, "just behind the Long Dock."

The boys looked in the direction indicated, and saw the top of the masts and sails of a boat which was moving slowly along on the other side of the dock.

"Now, Frank," said Harry, "turn out toward the middle of the river, and get as far ahead of him as you can, and see if we can't reach the island [meaning Strawberry Island] before he does."

Frank accordingly turned the Speedwell's head toward the island, and just at that moment the sail-boat came in sight. The Champion—for that was her name—was classed among the swiftest sailers about Lawrence; in fact, there was no sloop that could beat her. She was a clinker-built boat, about seventeen feet long, and her breadth of beam—that is, the distance across her from one side to the other—was great compared with her length. She was rigged like Frank's boat, having one mast and carrying a mainsail and jib; but as her sails were considerably larger than those of the Speedwell, and as she was a much lighter boat, the boys all expected that she would reach the island, which the young skippers always regarded as "home" in their races, long before the Speedwell. The Champion was sailed by two boys. William Johnson, her owner, sat in the stern steering, and Ben. Lake, a quiet, odd sort of a boy, sat on one of the middle thwarts managing the sails. As soon as she rounded the lock, Harry Butler sprang to his feet, and, seizing a small coil of rope that lay in the boat, called out,

"Bill! if you will catch this line, we'll tow you."

"No, I thank you," answered William. "I think we can get along very well without any of your help."

"Yes," chimed in Ben. Lake, "and we'll catch you before you are half-way to the island."

"We'll see about that!" shouted George, in reply.

By this time the Speedwell was fairly before the wind, the sails were hauled taut, the boys seated themselves on the windward gunwale, and the race began in earnest. But they soon found that it would be much longer than they had imagined. Instead of the slow, straining motion which they had expected, the Speedwell flew through the water like a duck, mounting every little swell in fine style, and rolling the foam back from her bow in great masses. She was, beyond a doubt, a fast sailer.

George and Harry shouted and hurrahed until they were hoarse, and Frank was so overjoyed that he could scarcely speak.

"How she sails!" exclaimed Harry. "If the Champion beats this, she will have to go faster than she does now."

Their pursuers were evidently much surprised at this sudden exhibition of the Speedwell's "sailing qualities;" and William hauled more to the wind and "crowded" his boat until she stood almost on her side, and the waves frequently washed into her.

"They will overtake us," said Frank, at length; "but I guess we can keep ahead of them until we cross the river."

And so it proved. The Champion began to gain—it was very slowly, but still she did gain—and when the Speedwell had accomplished half the distance across the river, their pursuers were not more than three or four rods behind.

At length they reached the island, and, as they rounded the point, they came to a spot where the wind was broken by the trees. The Speedwell gradually slackened her headway, and the Champion, which could sail much faster than she before a light breeze, gained rapidly, and soon came alongside.

"There is only one fault with your boat, Frank," said William; "her sails are too small. She can carry twice as much canvas as you have got on her now."

"Yes," answered Frank, "I find that I have made a mistake; but the fact is, I did not know how she would behave, and was afraid she would capsize. My first hard work shall be to make some new sails."

"You showed us a clean pair of heels, any way," said Ben. Lake, clambering over into the Speedwell. "Why, how nice and handy every thing is! Every rope is just where you can lay your hand on it."

"Let's go ashore and see how we are off for a crop of strawberries," said Harry.

William had pulled down his sails when he came alongside, and while the conversation was going on the Speedwell had been towing the Champion toward the island, and, just as Harry spoke, their bows ran high upon the sand. The boys sprang out, and spent two hours in roaming over the island in search of strawberries; but it was a little too early in the season for them, and, although there were "oceans" of green ones, they gathered hardly a pint of ripe ones.

After they had eaten the refreshments which Frank had brought with him, they started for home. As the wind blew from the main shore, they were obliged to "tack," and the Speedwell again showed some fine sailing, and when the Champion entered the creek, she was not a stone's throw behind.

Frank reached home that night a good deal elated at his success. After tying the Speedwell to the wharf, he pulled down the sails and carried them into his shop. He had promised, before leaving George and Harry, to meet them at five o'clock the next morning to start on a fishing excursion, and, consequently, could do nothing toward the new sails for his boat for two days.

Precisely at the time agreed upon, Frank might have been seen sitting on the wharf in front of Mr. Butler's house. In his hand he carried a stout, jointed fish-pole, neatly stowed away in a strong bag of drilling, and under his left arm hung his fish-basket, suspended by a broad belt, which crossed his breast. In this he carried his hooks, reels, trolling-lines, dinner, and other things necessary for the trip. Brave stood quietly by his side, patiently waiting for the word to start. They were not obliged to wait long, for hasty steps sounded on the gravel walk that led up to the house, the gate swung open, and George and Harry appeared, their arms filled with their fishing-tackle.

"You're on time, I see," said Harry, as he climbed down into a large skiff that was tied to the wharf, "Give us your fish-pole."

Frank accordingly handed his pole and basket down to Harry, who stowed them away in the boat. He and George then went into the boat-house, and one brought out a pair of oars and a sail, which they intended to use if the wind should be fair, and the other carried two pails of minnows, which had been caught the night before, to serve as bait.

They then got into the boat, and Frank took one oar and Harry the other, and Brave stationed himself at his usual place in the bow. George took the helm, and they began to move swiftly down the creek toward the river. About a quarter of a mile below the mouth of the creek was a place, covering half an acre, where the water was about four feet deep, and the bottom was covered with smooth, flat stones. This was known as the "black-bass ground," and large numbers of these fish were caught there every season. George turned the boat's head toward this place, and, thrusting his hand into his pocket, drew out a "trolling-line," and, dropping the hook into the water behind the boat, began to unwind the line. The trolling-hook (such as is generally used in fishing for black-bass) can be used only in a strong current, or when the boat is in rapid motion through the water. The hook is concealed by feathers or a strip of red flannel, and a piece of shining metal in the shape of a spoon-bowl is fastened to it in such a manner as to revolve around it when the hook is drawn rapidly through the water. This is fastened to the end of a long, stout line, and trailed over the stern of the boat, whose motion keeps it near the surface. It can be seen for a great distance in the water, and the fish, mistaking it for their prey, dart forward and seize it.

A few moments' pulling brought them to the bass ground, and George, holding the stick on which the line had been wound in his hand, waited impatiently for a "bite." They had hardly entered the ground when several heavy pulls at the line announced that the bait had been taken. George jerked in return, and, springing to his feet, commenced hauling in the line hand over hand, while whatever was at the other end jerked and pulled in a way that showed that he was unwilling to approach the surface. The boys ceased rowing, and Frank exclaimed,

"You've got a big one there, George. Don't give him any slack, or you'll lose him."

"Haul in lively," chimed in Harry. "There he breaches!" he continued, as the fish—a fine bass, weighing, as near as they could guess, six pounds—leaped entirely out of the water in his mad efforts to escape. "I tell you he's a beauty."

Frank took up the "dip-net," which the boys had used in catching the minnows, and, standing by George's side, waited for him to bring the fish within reach, so that he might assist in "landing" him. The struggle was exciting, but short. The bass was very soon exhausted, and George drew him alongside the boat, in which he was soon safely deposited under one of the seats.

They rowed around the ground for half an hour, each taking his turn at the line, and during that time they captured a dozen fish. The bass then began to stop biting; and Frank, who was at the helm, turned the boat toward the "perch-bed," which was some distance further down the river. It was situated at the outer edge of a bank of weeds, which lined the river on both sides. The weeds sprouted from the bottom in the spring, and by fall they reached the hight of four or five feet above the surface of the water. They were then literally swarming with wild ducks; but at the time of which we write, as it was only the latter part of June, they had not yet appeared above the water. The perch-bed was soon reached, and Harry, who was pulling the bow-oar, rose to his feet, and, raising the anchor, which was a large stone fastened to the boat by a long, stout rope, lifted it over the side, and let it down carefully into the water. The boat swung around until her bow pointed up stream, and the boys found themselves in the right spot to enjoy a good day's sport.

Frank, who was always foremost in such matters, had his pole rigged in a trice, and, baiting his hook with one of the minnows, dropped it into the water just outside of the weeds. Half a dozen hungry perch instantly rose to the surface, and one of them, weighing nearly a pound, seized the bait and darted off with it, and the next moment was dangling through the air toward the boat.

"That's a good-sized fish," said Harry, as he fastened his reel on his pole.

"Yes," answered Frank, taking his prize off the hook and throwing it into the boat; "and we shall have fine sport for a little while."

"But they will stop biting when the sun gets a little warmer; so we had better make the most of our time," observed George.

By this time the other boys had rigged their poles, and soon two more large perch lay floundering in the boat. For almost two hours they enjoyed fine sport, as Frank had said they would, and they were too much engaged to think of being hungry. But soon the fish began to stop biting, and Harry, who had waited impatiently for almost five minutes for a "nibble," drew up his line and opened a locker in the stern of the boat, and, taking out a basket containing their dinner, was about to make an inroad on its contents, when he discovered a boat, rowed by a boy about his own age, shoot rapidly around a point that extended for a considerable distance out into the river, and turn toward the spot where they were anchored.

"Boys," he exclaimed, "here comes Charley Morgan!"

"Charley Morgan," repeated Frank. "Who is he?"

"Why, he is the new-comer," answered George. "He lives in the large brick house on the hill."

Charley Morgan had formerly lived in New York. His father was a speculator, and was looked upon by some as a wealthy man; but it was hinted by those who knew him best that if his debts were all paid he would have but little ready money left. Be that as it may, Mr. Morgan and his family, at any rate, lived in style, and seemed desirous of outshining all their neighbors and acquaintances. Becoming weary of city life, they had decided to move into the country, and, purchasing a fine village lot in Lawrence, commenced building a house upon it. Although the village could boast of many fine dwellings, the one on Tower Hill, owned by Mr. Morgan, surpassed them all, and, as is always the case in such places, every one was eager to discover who was to occupy the elegant mansion. When the house was completed, Mr. Morgan returned to New York to bring on his family, leaving three or four "servants," as he called them, to look after his affairs; and the Julia Burton landed at the wharf, one pleasant morning, a splendid open carriage, drawn by a span of jet-black horses. The carriage contained Mr. Morgan and his family, consisting of his wife and one son—the latter about seventeen years old. At the time of his introduction to the reader they had been in the village about a week. Charles, by his haughty, overbearing manner, had already driven away from him the most sensible of the village boys who had become acquainted with him; but there are those every-where who seem, by some strange fatality, to choose the most unworthy of their acquaintances for their associates; and there were several boys in Lawrence who looked upon Charles as a first-rate fellow and a very desirable companion.

George and Harry, although they had frequently seen the "new-comer," had not had an opportunity to get acquainted with him; and Frank who, as we have said, lived in the outskirts of the village, and who had been very busy at work for the last week on his boat, had not seen him at all.

"What sort of a boy is he?" inquired the latter, continuing the conversation which we have so unceremoniously broken off.

"I don't know," replied Harry. "Some of the boys like him, but Ben. Lake says he's the biggest rascal in the village. He's got two or three guns, half a dozen fish-poles, and, by what I hear the boys say, he must be a capital sportsman. But he tells the most ridiculous stories about what he has done."

By this time Charles had almost reached them, and, when he came alongside, he rested on his oars and called out,

"Well, boys, how many fish have you caught?"

"So many," answered George, holding up the string, which contained over a hundred perch and black-bass. "Have you caught any thing?"

"Not much to brag of," answered Charles; "I hooked up a few little perch just behind the point. But that is a tip-top string of yours."

"Yes, pretty fair," answered Harry. "You see we know where to go."

"That does make some difference," said Charles. "But as soon as I know the good places, I'll show you how to catch fish."

"We will show you the good fishing-grounds any time," said George.

"Oh, I don't want any of your help. I can tell by the looks of a place whether there are any fish to be caught or not. But you ought to see the fishing-grounds we have in New York," he continued. "Why, many a time I've caught three hundred in less than half an hour, and some of them would weigh ten pounds."

"Did you catch them with a hook and line?" inquired George.

"Of course I did! What else should I catch them with? I should like to see one of you trying to handle a ten or fifteen-pound fish with nothing but a trout-pole."

"Could you do it?" inquired Harry, struggling hard to suppress a laugh.

"Do it? I have done it many a time. But is there any hunting around here?"

"Plenty of it."

"Well," continued Charles, "I walked all over the woods this morning, and couldn't find any thing."

"It is not the season for hunting now," said George; "but in the fall there are lots of ducks, pigeons, squirrels, and turkeys, and in the winter the woods are full of minks, and now and then a bear or deer; and the swamps are just the places to kill muskrats."

"I'd just like to go hunting with some of you. I'll bet I can kill more game in a day than any one in the village."

The boys made no reply to this confident assertion, for the fact was that they were too full of laughter to trust themselves to speak.

"I'll bet you haven't got any thing in the village that can come up to this," continued Charles; and as he spoke he raised a light, beautifully-finished rifle from the bottom of the boat, and held it up to the admiring gaze of the boys.

"That is a beauty," said Harry, who wished to continue the conversation as long as possible, in order to hear some more of Charles's "large stories." "How far will it shoot?"

"It cost me a hundred dollars," answered Charles, "and I've killed bears and deer with it, many a time, as far as across this river here."

Charles did not hesitate to say this, for he was talking only to "simple-minded country boys," as he called them, and he supposed he could say what he pleased and they would believe it. His auditors, who before had been hardly able to contain themselves, were now almost bursting with laughter. Frank and George, however, managed to draw on a sober face, while Harry turned away his head and stuffed his handkerchief into his mouth.

"I tell you," continued Charles, not noticing the condition his hearers were in, "I've seen some pretty tough times in my life. Once, when I was hunting in the Adirondack Mountains, in the northern part of Michigan, I was attacked by Indians, and came very near being captured, and the way I fought was a caution to white folks. This little rifle came handy then, I tell you. But I must hurry along now; I promised to go riding with the old man this afternoon."

And he dipped the oars into the water, and the little boat shot rapidly up the river. It was well that he took his departure just as he did, for our three boys could not possibly have contained themselves a moment longer. They could not wait for him to get out of sight, but, lying back in the boat, they laughed until the tears rolled down their cheeks.

"Well, Frank, what do you think of him?" inquired Harry, as soon as he could speak.

"I think the less we have to do with him the better," answered Frank.

"I did think," said Harry, stopping now and then to indulge in a hearty fit of laughter, "that there might be some good things about him; but a boy that can tell such whopping big lies as he told must be very small potatoes. Only think of catching three hundred fish in less than half an hour, and with only one hook and line! Why, that would be ten every minute, and that is as many as two men could manage. And then for him to talk about that pop-gun of his shooting as far as across this river!—why, it's a mile and a half—and I know it wouldn't shoot forty rods, and kill. But the best of all was his hunting among the Adirondack Mountains, in Michigan, and having to defend himself against the Indians; that's a good joke."

And Harry laid back in the boat again, and laughed and shouted until his sides ached.

"He must be a very ungrateful fellow," said Frank, at length. "Didn't you notice how disrespectfully he spoke of his father? He called him his 'old man.' If I had a father, I'd never speak so lightly of him."

"Yes, I noticed that," said George. "But," he continued, reaching for the basket which Harry, after helping himself most bountifully, had placed on the middle seat, "I'm hungry as blazes, and think I can do justice to the good things mother has put up for us."

After eating their dinner they got out their fishing-tackle again; but the perch had stopped biting, and, after waiting patiently for half an hour without feeling a nibble, they unjointed their poles, drew up the anchor, and Frank seated himself at the helm, while George and Harry took the oars and pulled toward home.

One of the range of hills which extended around the western side of the village was occupied by several families, known as the "Hillers." They were ignorant, degraded people, living in miserable hovels, and obtaining a precarious subsistence by hunting, fishing, and stealing. With them the villagers rarely, if ever, had intercourse, and respectable persons seldom crossed their thresholds. The principal man among the Hillers was known as Bill Powell. He was a giant in strength and stature, and used to boast that he could visit "any hen-roost in the village every night in the week, and carry off a dozen chickens each time, without being nabbed." He was very fond of liquor, too indolent to work, and spent most of his time, when out of jail, on the river, fishing, or roaming through the woods with his gun. He had one son, whose name was Lee, and a smarter boy it was hard to find. He possessed many good traits of character, but, as they had never been developed, it was difficult to discover them. He had always lived in the midst of evil influences, led by the example of a drunken, brutal father, and surrounded by wicked companions, and it is no wonder that his youthful aspirations were in the wrong direction.

Lee and his associates, as they were not obliged so attend school, and were under no parental control, always amused themselves as they saw it. Most of their time was spent on the river or in the woods, and, when weary of this sport, the orchards and melon-patches around the village, although closely guarded, were sure to suffer at their hands; and they planned and executed their plundering expeditions with so much skill and cunning, that they were rarely detected.

A day or two after the events related in the preceding chapter transpired, Charles Morgan, in company with two or three of his chosen companions, was enjoying a sail on the river. During their conversation, one of the boys chanced to say something about the Hillers, and Charles inquired who they were. His companions gave him the desired information, and ended by denouncing them in the strongest terms.

Charles, after hearing them through, exclaimed, "I'd just like to catch one of those boys robbing our orchard or hen-roost. One or the of us would get a pummeling, sure as shooting."

"Yes," said one of the boys, "but, you see, they do not go alone. If they did, it would be an easy matter to catch them. But they all go together, and half of them keep watch, and the rest bag the plunder; and they move around so still that even the dogs don't hear them."

"I should think you fellows here in the village would take the matter into your own hands," said Charles.

"What do you mean?" inquired his companions.

"Why don't you club together, and every time you see one of the Hillers, go to work and thrash him like blazes? I guess, after you had half-killed two or three of them, they would learn to let things alone."

"I guess they would, too," said one of the boys.

"Suppose we get up a company of fifteen or twenty fellows," resumed Charles, "and see how it works. I'll bet my eyes that, after we've whipped half a dozen of them, they won't dare to show their faces in the village again."

"That's the way to do it," said one of the boys. "I'll join the company, for one."

The others readily fell in with Charles's proposal, and they spent some time talking it over and telling what they intended to do when they could catch the Hillers, when one of the boys suddenly exclaimed,

"I think, after all, that we shall have some trouble in carrying out our plans. Although there are plenty of fellows in the village who would be glad to join the company, there are some who must not know any thing about it, or the fat will all be in the fire."

"Who are they?" demanded Charles.

"Why, there are Frank Nelson, and George and Harry Butler, and Bill Johnson, and a dozen others, who could knock the whole thing into a cocked hat, in less than no time."

"Could they? I'd just like to see them try it on," said Charles, with a confident air. "They would have a nice time of it. How would they go to work?"

"I am afraid that, if they saw us going to whip the Hillers, they would interfere."

"They would, eh? I'd like to see them undertake to hinder us. Can't twenty fellows whip a dozen?"

"I don't know. Every one calls Frank Nelson and his set the best boys in the village. They never fight if they can help it; but they are plaguy smart fellows, I tell you; and, if we once get them aroused, we shall have a warm time of it, I remember a little circumstance that happened last winter. We had a fort in the field behind the school-house, and one night we were out there, snowballing, and I saw Frank Nelson handle two of the largest boys in his class. There were about a dozen boys in the fort—and they were the ones that always go with Frank—and all the rest of the school were against them. The fort stood on a little hill, and we were almost half an hour capturing it, and we wouldn't ever have taken it if the wall hadn't been broken down. We would get almost up to the fort, and they would rush out and drive us down again. At last we succeeded in getting to the top of the hill, and our boys began to tumble over the walls, and I hope I may be shot if they didn't throw us out as fast as we could get in, and—"

"Oh, I don't care any thing about that," interrupted Charles, who could not bear to hear any one but himself praised. "If I had been there, I would have run up and thrown them out."

"And you could have done it easy enough," said one of the boys, who had for some time remained silent.

"Frank Nelson and his set are not such great fellows, after all."

"Of course they ain't," said the other. "They feel big enough; but I guess, if we get this company we have spoken of started, and they undertake to interfere with us, we will take them down a peg or two."

"That's the talk!" said Charles. "I never let any one stop me when I have once made up my mind to do a thing. I would as soon knock Frank Nelson down as any body else."

By this time the boat, which had been headed toward the shore, entered the creek, and Charles drew up to the wharf, and, after setting his companions ashore, and directing them to speak to every one whom they thought would be willing to join the company, and to no one else, he drew down the sails, and pulled up the creek toward the place where he kept his boat.

A week passed, and things went on swimmingly. Thirty boys had enrolled themselves as members of the Regulators, as the company was called, and Charles, who had been chosen captain, had carried out his plans so quietly, that he was confident that no one outside of the company knew of its existence. Their arrangements had all been completed, and the Regulators waited only for a favorable opportunity to carry their plans into execution.

Frank, during this time, had remained at home, working in his garden or shop, and knew nothing of what was going on.

One afternoon he wrote a letter to his cousin Archie, and, after supper, set out, with Brave at his heels, to carry it to the post-office. He stopped on the way for George and Harry Butler, who were always ready to accompany him. On the steps of the post-office they met three or four of their companions, and, after a few moments' conversation, William Johnson suddenly inquired,

"Have you joined the new society, Frank?"

"What society?"

"Why, the Regulators."

"I don't know what you mean," said Frank.

"Yes, I guess they have managed to keep it pretty quiet," said William. "They don't want any outsiders to know any thing about it. They asked me to join in with them, but I told them that they ought to know better than to propose such a thing to me. Then they tried to make me promise that I wouldn't say any thing about it, but I would make no such promise, for—"

"Why, Bill, what are you talking about?" inquired Harry. "You rattle it off as if we knew all about it."

"Haven't you heard any thing about it, either?" inquired William, in surprise. "I was certain that they would ask you to join. Well, the amount of it is that Charley Morgan and a lot of his particular friends have been organizing a company for the purpose of thrashing the Hillers, and making them stop robbing hen-roosts and orchards and cutting up such shines."

"Yes," chimed in James Porter, "there are about thirty of them, and they say that they are going to whip the Hillers out of the village."

"Well, that's news to me," said Frank.

"For my part," said Thomas Benton, "I, of course, know that the Hillers ought to be punished; but I do not think it is the duty of us boys to take the law into our own hands."

"Nor I," said James Porter.

"Well, I do," said Harry, who, as we have said, was an impetuous, fiery fellow, "and I believe I will join the Regulators, and help whip the rascals out of the country. They ought, every one of them, to be thrashed for stealing and—"

"Now, see here, Harry," interrupted George. "You know very well that such a plan will never succeed, and it ought not to. You have been taught that it is wrong to take things that do not belong to you, but with the Hillers the case is different; their parents teach them to steal, and they are obliged to do it."

"Besides," said Frank, "this summary method of correcting them will not break up their bad habits; kindness will accomplish much more than force."

"Kindness!" repeated Harry, sneeringly; "as if kindness could have any effect on a Hiller!"

"They can tell when they are kindly treated as well as any one else," said George.

"And another thing," said Ben. Lake; "these Regulators must be a foolish set of fellows to suppose that the Hillers are going to stand still and be whipped. I say, as an old sea-captain once said, when it was proposed to take a man-o'-war with a whale-boat, 'I guess it will be a puttering job.'"

"Well," said James, "I shall do all I can to prevent a fight."

"So will I," said Frank.

"I won't," said Harry, who, with his arms buried almost to the elbows in his pockets, was striding backward and forward across the steps. "I say the Hillers ought to be thrashed."

"I'm afraid," said William, without noticing what Harry had remarked, "that our interference will be the surest way to bring on a fight; because, after I refused to join the company, they told me that if any of us attempted to defend the Hillers, or break up the company, they would thrash us, too."

"We don't want to break up their company," said Frank, with a laugh. "We must have a talk with them, and try to show them how unreasonable they are."

"Here they come, now," said George, pointing up the road.

The boys looked in the direction indicated, and saw the Regulators just turning the corner of the street that led to Mr. Morgan's house. They came around in fine order, marching four abreast, and turned up the street that led to the post-office. They had evidently been well drilled, for they kept step admirably.

"They look nice, don't they?" said Ben.

"Yes," answered George; "and if they were enlisted in a good cause, I would off with my hat and give them three cheers."

The Regulators had almost reached the post-office, when they suddenly set up a loud shout, and, breaking ranks, started on a full run down the street. The boys saw the reason for this, when they discovered Lee Powell coming up the road that led from the river, with a large string of fish in his hand. He always had good luck, but he seemed to have been more fortunate than usual, for his load was about as heavy as he could conveniently carry. He walked rapidly along, evidently very much occupied with his own thoughts, when, suddenly, two or three stones came skipping over the ground, and aroused him from his reverie. He looked up in surprise, and discovered that his enemies were so close to him that flight was useless.

The Regulators drew nearer and nearer, and the stones fell thick about the object of their wrath, until, finally, one struck him on the shoulder, and another knocked his cap from his head.

"I can't stand that," said Frank; and, springing from the steps, he started to the rescue, followed by all of his companions, (except Harry, who still paced the steps), and they succeeded in throwing themselves between Lee and his assailants.

Several of the Regulators faltered on seeing Lee thus defended; but Charles, followed by half a dozen of his "right-hand men," advanced, and attempted to force his way between Frank and his companions.

"Hold on, here!" said Frank, as he gently, but firmly, resisted Charles's attempts to push him aside. "What are you trying to do?"

"What business is that of yours?" answered Charles, roughly, as he continued his efforts to reach Lee. "You question me as if you were my master. Stand aside, if you don't want to get yourself in trouble."

"You don't intend to hurt Lee, do you?"

"Yes, I do. But it's none of your business, any way. Get out of the way!"

"Has he ever done you any harm?"

"It's none of your business, I say!" shouted Charles, now almost beside himself with rage.

"And I want you to keep your hands off me!" he continued, as Frank seized his arm, which he had raised to strike Lee, who stood close behind his protector.

Frank released his hold, and Charles sprang forward again, and, dodging Frank's grasp, slipped under his arm, and attempted to seize the Hiller. But Frank was as quick as a cat in his motions; and, before Charles had time to strike a blow, he seized him with a grip that brought from him a cry of pain, and seated him, unceremoniously, on the ground.

As soon as Charles could regain his feet, he called out,

"Here it is, boys—just as I expected! Never mind the Hiller, but let's go to work and give the other fellows a thrashing that they won't get over in a month."

And he sprang toward Frank, against whom he seemed to cherish an especial grudge, followed by a dozen Regulators, who brandished their fists as if they intended to annihilate Lee's gallant defenders. But, just as Charles was about to attack Frank, a new actor appeared. Harry Butler, who had greatly changed his mind in regard to "thrashing the Hillers," seeing that the attack was about to be renewed, sprang down the steps, and caught Charles in his arms, and threw him to the ground, like a log.