Title: The Troubadours

Author: H. J. Chaytor

Release date: May 1, 2004 [eBook #12456]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/12456

Credits: Produced by Ted Garvin, Renald Levesque and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team.

With the exception of the coat of arms at the foot, the design on the title page is a reproduction of one used by the earliest known Cambridge printer, John Siberch, 1521

This book, it is hoped, may serve as an introduction to the literature of the Troubadours for readers who have no detailed or scientific knowledge of the subject. I have, therefore, chosen for treatment the Troubadours who are most famous or who display characteristics useful for the purpose of this book. Students who desire to pursue the subject will find further help in the works mentioned in the bibliography. The latter does not profess to be exhaustive, but I hope nothing of real importance has been omitted.

H.J. CHAYTOR.

THE COLLEGE, PLYMOUTH, March 1912.

PREFACE

CHAP.

I. INTRODUCTORY

II. THE THEORY OF COURTLY LOVE

III. TECHNIQUE

IV. THE EARLY TROUBADOURS

V. THE CLASSICAL PERIOD

VI. THE ALBIGEOIS CRUSADE

VII. THE TROUBADOURS IN ITALY

VIII. THE TROUBADOURS IN SPAIN

IX. PROVENCAL INFLUENCE IN GERMANY, FRANCE, AND ENGLAND

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND NOTES

INDEX

INTRODUCTORY

Few literatures have exerted so profound an influence upon the literary history of other peoples as the poetry of the troubadours. Attaining the highest point of technical perfection in the last half of the twelfth and the early years of the thirteenth century, Provençal poetry was already popular in Italy and Spain when the Albigeois crusade devastated the south of France and scattered the troubadours abroad or forced them to seek other means of livelihood. The earliest lyric poetry of Italy is Provençal in all but language; almost as much may be said of Portugal and Galicia; Catalonian troubadours continued to write in Provençal until the fourteenth century. The lyric poetry of the "trouvères" in Northern France was deeply influenced both in form and spirit by troubadour poetry, and traces of this influence are perceptible even in [2] early middle-English lyrics. Finally, the German minnesingers knew and appreciated troubadour lyrics, and imitations or even translations of Provençal poems may be found in Heinrich von Morungen, Friedrich von Hausen, and many others. Hence the poetry of the troubadours is a subject of first-rate importance to the student of comparative literature.

The northern limit of the Provençal language formed a line starting from the Pointe de Grave at the mouth of the Gironde, passing through Lesparre, Bordeaux, Libourne, Périgueux, rising northward to Nontron, la Rochefoucauld, Confolens, Bellac, then turning eastward to Guéret and Montluçon; it then went south-east to Clermont-Ferrand, Boën, Saint Georges, Saint Sauveur near Annonay. The Dauphiné above Grenoble, most of the Franche-Comté, French Switzerland and Savoy, are regarded as a separate linguistic group known as Franco-Provençal, for the reason that the dialects of that district display characteristics common to both French and Provençal.1 On the south-west, Catalonia, Valencia and the Balearic Isles must also be included in the Provençal region. As concerns the Northern limit, it must not be regarded as a definite line of demarcation between the langue d'oil or the Northern French dialects and the langue d'oc or Provençal. The boundary is, of course, determined by noting the points at which certain linguistic features peculiar to Provençal cease and are replaced by the characteristics of Northern [3] French. Such a characteristic, for instance, is the Latin tonic a before a single consonant, and not preceded by a palatal consonant, which remains in Provençal but becomes e in French; Latin cantare becomes chantar in Provençal but chanter in French. But north and south of the boundary thus determined there was, in the absence of any great mountain range or definite geographical line of demarcation, an indeterminate zone, in which one dialect probably shaded off by easy gradations into the other.

Within the region thus described as Provençal, several separate dialects existed, as at the present day. Apart from the Franco-Provençal on the north-east, which we have excluded, there was Gascon in the south-west and the modern départements of the Basses and Hautes Pyrénées; Catalonian, the dialect of Roussillon, which was brought into Spain in the seventh century and still survives in Catalonia, Valencia and the Balearic Islands. The rest of the country may be subdivided by a line to the north of which c before a becomes ch as in French, cantare producing chantar, while southwards we find c(k) remaining. The Southern dialects are those of Languedoc and Provence; north of the line were the Limousin and Auvergne dialects. At the present day these dialects have diverged very widely. In the early middle ages the difference between them was by no means so great. Moreover, a literary [4] language grew up by degrees, owing to the wide circulation of poems and the necessity of using a dialect which could be universally intelligible. It was the Limousin dialect which became, so to speak, the backbone of this literary language, now generally known as Provençal, just as the Tuscan became predominant for literary purposes among the Italian dialects. It was in Limousin that the earliest troubadour lyrics known to us were composed, and this district with the adjacent Poitou and Saintonge may therefore be reasonably regarded as the birthplace of Provençal lyric poetry.

Hence the term "Provençal" is not entirely appropriate to describe the literary language of the troubadours, as it may also be restricted to denote the dialects spoken in the "Provincia". This difficulty was felt at an early date. The first troubadours spoke of their language as roman or lingua romana, a term equally applicable to any other romance language. Lemosin was also used, which was too restricted a term, and was also appropriated by the Catalonians to denote their own dialect. A third term in use was the lingua d'oc, which has the authority of Dante 2 and was used by some of the later troubadours; however, the term "Provençal" has been generally accepted, and must henceforward be understood to denote the literary language common to the [5] south of France and not the dialect of Provence properly so-called.

For obvious reasons Southern France during the early middle ages had far outstripped the Northern provinces in art, learning, and the refinements of civilisation. Roman culture had made its way into Southern Gaul at an early date and had been readily accepted by the inhabitants, while Marseilles and Narbonne had also known something of Greek civilisation. Bordeaux, Toulouse, Arles, Lyons and other towns were flourishing and brilliant centres of civilisation at a time when Northern France was struggling with foreign invaders. It was in Southern Gaul, again, that Christianity first obtained a footing; here the barbarian invasions of the fifth and sixth centuries proved less destructive to civilisation than in Northern France, and the Visigoths seem to have been more amenable to the influences of culture than the Northern Franks. Thus the towns of Southern Gaul apparently remained centres in which artistic and literary traditions were preserved more or less successfully until the revival of classical studies during the age of Charlemagne. The climate, again, of Southern France is milder and warmer than that of the North, and these influences produced a difference which may almost be termed racial. It is a difference visible even to-day and is well expressed by [6] the chronicler Raoul de Caen, who speaks of the Provençal Crusaders, saying that the French were prouder in bearing and more war-like in action than the Provençals, who especially contrasted with them by their skill in procuring food in times of famine: "inde est, quod adhuc puerorum decantat naenia, Franci ad bella, Provinciales ad victualia".3 Only a century and a half later than Charlemagne appeared the first poetical productions in Provençal which are known to us, a fragment of a commentary upon the De Consolatione of Boethius4 and a poem upon St Foy of Agen. The first troubadour, William, Count of Poitiers, belongs to the close of the eleventh century.

Though the Count of Poitiers is the first troubadour known to us, the relatively high excellence of his technique, as regards stanza construction and rime, and the capacity of his language for expressing lofty and refined ideas in poetical form (in spite of his occasional lapses into coarseness), entirely preclude the supposition that he was the first troubadour in point of time. The artistic conventions apparent in his poetry and his obviously careful respect for fixed rules oblige us to regard his poetry as the outcome of a considerable stage of previous development. At what point this development began and what influences stimulated its progress are questions which still remain in [7] dispute. Three theories have been proposed. It is, in the first place, obviously tempting to explain the origin of Provençal poetry as being a continuation of Latin poetry in its decadence. When the Romans settled in Gaul they brought with them their amusements as well as their laws and institutions. Their scurrae, thymelici and joculatores, the tumblers, clowns and mountebanks, who amused the common people by day and the nobles after their banquets by night and travelled from town to town in pursuit of their livelihood, were accustomed to accompany their performances by some sort of rude song and music. In the uncivilised North they remained buffoons; but in the South, where the greater refinement of life demanded more artistic performance, the musical part of their entertainment became predominant and the joculator became the joglar (Northern French, jongleur), a wandering musician and eventually a troubadour, a composer of his own poems. These latter were no longer the gross and coarse songs of the earlier mountebank age, which Alcuin characterised as turpissima and vanissima, but the grave and artificially wrought stanzas of the troubadour chanso.

Secondly, it has been felt that some explanation is required to account for the extreme complexity and artificiality of troubadour poetry in its most highly developed stage. Some nine hundred different forms of stanza [8] construction are to be found in the body of troubadour poetry,5 and few, if any schools of lyric poetry in the world, can show a higher degree of technical perfection in point of metrical diversity, complex stanza construction and accuracy in the use of rime. This result has been ascribed to Arabic influence during the eighth century; but no sufficient proof has ever been produced that the complexities of Arabic and Provençal poetry have sufficient in common to make this hypothesis anything more than an ingenious conjecture.

One important fact stands in contradiction to these theories. All indications go to prove that the origin of troubadour poetry can be definitely localised in a particular part of Southern France. We have seen that the Limousin dialect became the basis of the literary language, and that the first troubadour known to us belonged to Poitou. It is also apparent that in the Poitou district, upon the border line of the French and Provençal languages, popular songs existed and were current among the country people; these were songs in honour of spring, pastorals or dialogues between a knight and a shepherdess (our "Where are you going, my pretty maid?" is of the same type), albas or dawn songs which represent a friend as watching near the meeting-place of a lover and his lady and giving him due warning of the approach of dawn or [9] of any other danger; there are also ballatas or dance songs of an obviously popular type.6 Whatever influence may have been exercised by the Latin poetry of the decadence or by Arab poetry, it is in these popular and native productions that we must look for the origins of the troubadour lyrics. This popular poetry with its simple themes and homely treatment of them is to be found in many countries, and diversity of race is often no bar to strange coincidence in the matter of this poetry. It is thus useless to attempt to fix any date for the beginnings of troubadour poetry; its primitive form doubtless existed as soon as the language was sufficiently advanced to become a medium of poetical expression.

Some of these popular themes were retained by the troubadours, the alba and pastorela for instance, and were often treated by them in a direct and simple manner. The Gascon troubadour Cercamon is said to have composed pastorals in "the old style." But in general, between troubadour poetry and the popular poetry of folk-lore, a great gulf is fixed, the gulf of artificiality. The very name "troubadour" points to this characteristic. Trobador is the oblique case of the nominative trobaire, a substantive from the verb trobar, in modern French trouver. The Northern French trouvère is a nominative form, and trouveor should more properly correspond with trobador. The accusative form, which should have persisted, was superseded by the [10] nominative trouvère, which grammarians brought into fashion at the end of the eighteenth century. The verb trobar is said to be derived from the low Latin tropus [Greek: tropus], an air or melody: hence the primitive meaning of trobador is the "composer" or "inventor," in the first instance, of new melodies. As such, he differs from the vates, the inspired bard of the Romans and the [Greek: poeta], poeta, the creative poet of the Greeks, the "maker" of Germanic literature. Skilful variation upon a given theme, rather than inspired or creative power, is generally characteristic of the troubadour.

Thus, whatever may have been the origin of troubadour poetry, it appears at the outset of the twelfth century as a poetry essentially aristocratic, intended for nobles and for courts, appealing but rarely to the middle classes and to the common people not at all. The environment which enabled this poetry to exist was provided by the feudal society of Southern France. Kings, princes and nobles themselves pursued the art and also became the patrons of troubadours who had risen from the lower classes. Occasionally troubadours existed with sufficient resources of their own to remain independent; Folquet of Marseilles seems to have been a merchant of wealth, above the necessity of seeking patronage. But troubadours such as Bernart de Ventadour, the son of the [11] stoker in the castle of Ventadour, Perdigon the son of a fisherman, and many others of like origin depended for their livelihood and advancement upon the favour of patrons. Thus the troubadour ranks included all sorts and conditions of men; monks and churchmen were to be found among them, such as the monk of Montaudon and Peire Cardenal, though the Church looked somewhat askance upon the profession. Women are also numbered among the troubadours; Beatrice, the Countess of Die, is the most famous of these.

A famous troubadour usually circulated his poems by the mouth of a joglar (Northern French, jongleur), who recited them at different courts and was often sent long distances by his master for this purpose. A joglar of originality might rise to the position of a troubadour, and a troubadour who fell upon evil days might sink to the profession of joglar. Hence there was naturally some confusion between the troubadour and the joglar, and poets sometimes combined the two functions. In course of time the joglar was regarded with some contempt, and like his forbear, the Roman joculator, was classed with the jugglers, acrobats, animal tamers and clowns who amused the nobles after their feasts. Nor, under certain conditions, was the troubadour's position one of dignity; [12] when he was dependent upon his patron's bounty, he would stoop to threats or to adulation in order to obtain the horse or the garments or the money of his desire; such largesse, in fact, came to be denoted by a special term, messio. Jealousy between rival troubadours, accusations of slander in their poems and quarrels with their patrons were of constant occurrence. These naturally affected the joglars in their service, who received a share of any gifts that the troubadour might obtain.

The troubadours who were established more or less permanently as court poets under a patron lord were few; a wandering life and a desire for change of scene is characteristic of the class. They travelled far and wide, not only to France, Spain and Italy, but to the Balkan peninsula, Hungary, Cyprus, Malta and England; Elias Cairel is said to have visited most of the then known world, and the biographer of Albertet Calha relates, as an unusual fact, that this troubadour never left his native district. Not only love, but all social and political questions of the age attracted their attention. They satirised political and religious opponents, preached crusades, sang funeral laments upon the death of famous patrons, and the support of their poetical powers was often in demand by princes and nobles involved in a struggle. Noteworthy also is the fact that a considerable number retired to some monastery or [13] religious house to end their days (se rendet, was the technical phrase). So Bertran of Born, Bernart of Ventadour, Peire Rogier, Cadenet and many others retired from the disappointments of the world to end their days in peace; Folquet of Marseilles, who similarly entered the Cistercian order, became abbot of his monastery of Torondet, Bishop of Toulouse, a leader of the Albigeois crusade and a founder of the Inquisition.

Troubador poetry dealt with war, politics, personal satire and other subjects: but the theme which is predominant and in which real originality was shown, is love. The troubadours were the first lyric poets in mediaeval Europe to deal exhaustively with this subject, and as their attitude was imitated with certain modifications by French, Italian, Portuguese and German poets, the nature of its treatment is a matter of considerable importance.

Of the many ladies whose praises were sung or whose favours were desired by troubadours, the majority were married. Troubadours who made their songs to a maiden, as did Gui d'Ussel or Gausbert de Puegsibot, are quite exceptional. Love in troubadour poetry was essentially a conventional relationship, and marriage was not its object. This conventional character was derived from the fact that troubadour love was constituted upon the analogy of feudal relationship. If chivalry was the outcome of the Germanic theory of knighthood as modified by the influence of Christianity, it may be said that troubadour love is the [15] outcome of the same theory under the influence of mariolatry. In the eleventh century the worship of the Virgin Mary became widely popular; the reverence bestowed upon the Virgin was extended to the female sex in general, and as a vassal owed obedience to his feudal overlord, so did he owe service and devotion to his lady. Moreover, under the feudal system, the lady might often be called upon to represent her husband's suzerainty to his vassals, when she was left in charge of affairs during his absence in time of war. Unmarried women were inconspicuous figures in the society of the age.

Thus there was a service of love as there was a service of vassalage, and the lover stood to his lady in a position analogous to that of the vassal to his overlord. He attained this position only by stages; "there are four stages in love: the first is that of aspirant (fegnedor), the second that of suppliant (precador), the third that of recognised suitor (entendedor) and the fourth that of accepted lover (drut)." The lover was formally installed as such by the lady, took an oath of fidelity to her and received a kiss to seal it, a ring or some other personal possession. For practical purposes the contract merely implied that the lady was prepared to receive the troubadour's homage in poetry and to be the subject of his song. As secrecy was a duty incumbent upon [16] the troubadour, he usually referred to the lady by a pseudonym (senhal); naturally, the lady's reputation was increased if her attraction for a famous troubadour was known, and the senhal was no doubt an open secret at times. How far or how often the bounds of his formal and conventional relationship were transgressed is impossible to say; "en somme, assez immoral" is the judgment of Gaston Paris upon the society of the age, and is confirmed by expressions of desire occurring from time to time in various troubadours, which cannot be interpreted as the outcome of a merely conventional or "platonic" devotion. In the troubadour biographies the substratum of historical truth is so overlaid by fiction, that little reliable evidence upon the point can be drawn from this source.

However, transgression was probably exceptional. The idea of troubadour love was intellectual rather than emotional; love was an art, restricted, like poetry, by formal rules; the terms "love" and "poetry" were identified, and the fourteenth century treatise which summarises the principles of grammar and metre bore the title Leys d'Amors, the Laws of Love. The pathology of the emotion was studied; it was treated from a psychological standpoint and a technical vocabulary came into use, for which it is often impossible to find English equivalents. The first effect of love is to produce a mental exaltation, a desire to live [17] a life worthy of the beloved lady and redounding to her praise, an inspiring stimulus known as joi or joi d'amor (amor in Provençal is usually feminine).7 Other virtues are produced by the influence of this affection: the lover must have valor, that is, he must be worthy of his lady; this worth implies the possession of cortesia, pleasure in the pleasure of another and the desire to please; this quality is acquired by the observance of mesura, wisdom and self-restraint in word and deed.

The poetry which expresses such a state of mind is usually idealised and pictures the relationship rather as it might have been than as it was. The troubadour who knew his business would begin with praises of his beloved; she is physically and morally perfect, her beauty illuminates the night, her presence heals the sick, cheers the sad, makes the boor courteous and so forth. For her the singer's love and devotion is infinite: separation from her would be worse than death; her death would leave the world cheerless, and to her he owes any thoughts of good or beauty that he may have. It is only because he loves her that he can sing. Hence he would rather suffer any pain or punishment at her hands than receive the highest favours from another. The effects of this love are obvious in his person. His voice quavers with supreme delight or [18] breaks in dark despair; he sighs and weeps and wakes at night to think of the one subject of contemplation. Waves of heat and cold pass over him, and even when he prays, her image is before his eyes. This passion has transformed his nature: he is a better and stronger man than ever before, ready to forgive his enemies and to undergo any physical privations; winter is to him as the cheerful spring, ice and snow as soft lawns and flowery meads. Yet, if unrequited, his passion may destroy him; he loses his self-control, does not hear when he is addressed, cannot eat or sleep, grows thin and feeble, and is sinking slowly to an early tomb. Even so, he does not regret his love, though it lead to suffering and death; his passion grows ever stronger, for it is ever supported by hope. But if his hopes are realised, he will owe everything to the gracious favour of his lady, for his own merits can avail nothing. Sometimes he is not prepared for such complete self-renunciation; he reproaches his lady for her coldness, complains that she has led him on by a show of kindness, has deceived him and will be the cause of his death; or his patience is at an end, he will live in spite of her and try his fortune elsewhere.8

Such, in very general terms, is the course that might be followed in developing a well-worn theme, on which many variations are possible. The [19] most common form of introduction is a reference to the spring or winter, and to the influence of the seasons upon the poet's frame of mind or the desire of the lady or of his patron for a song. In song the poet seeks consolation for his miseries or hopes to increase the renown of his lady. As will be seen in the following chapter, manner was even more important than matter in troubadour lyrics, and commonplaces were revivified by intricate rime-schemes and stanza construction accompanied by new melodies. The conventional nature of the whole business may be partly attested by the fact that no undoubted instance of death or suicide for love has been handed down to us.

Reference should here be made to a legendary institution which seems to have gripped the imagination of almost every tourist who writes a book of travels in Southern France, the so-called Courts of Love.9 In modern times the famous Provençal scholar, Raynouard, attempted to demonstrate the existence of these institutions, relying upon the evidence of the Art d'Aimer by André le Chapelain, a work written in the thirteenth century and upon the statements of Nostradamus (Vies des plus célèbres et anciens poètes provençaux, Lyons 1575). The latter writer, the younger brother of the famous prophet, was obviously well acquainted with Provençal literature and had access to sources of [20] information which are now lost to us. But instead of attempting to write history, he embellished the lives of the troubadours by drawing upon his own extremely fertile imagination when the actual facts seemed too dull or prosaic to arouse interest. He professed to have derived his information from a manuscript left by a learned monk, the Moine des Iles d'Or, of the monastery of St Honorat in the Ile de Lerins. The late M. Camille Chabaneau has shown that the story is a pure fiction, and that the monk's pretended name was an anagram upon the name of a friend of Nostradamus.10 Hence it is almost impossible to separate the truth from the fiction in this book and any statements made by Nostradamus must be received with the utmost caution. André le Chapelain seems to have had no intention to deceive, but his knowledge of Provençal society was entirely second-hand, and his statements concerning the Courts of Love are no more worthy of credence than those of Nostradamus. According to these two unreliable authorities, courts for the decision of lovers' perplexities existed in Gascony, Provence, Avignon and elsewhere; the seat of justice was held by some famous lady, and the courts decided such questions as whether a lover could love two ladies at the same time, whether lovers or married couples were the more affectionate, whether love was compatible with avarice, and the like. [21]

A special poetical form which was popular among the troubadours may have given rise to the legend. This was the tenso,11 in which one troubadour propounded a problem of love in an opening stanza and his opponent or interlocutor gave his view in a second stanza, which preserved the metre and rime-scheme of the first. The propounder then replied, and if, as generally, neither would give way, a proposal was made to send the problem to a troubadour-patron or to a lady for settlement, a proposal which came to be a regular formula for concluding the contest. Raynouard quotes the conclusion of a tenso given by Nostradamus in which one of the interlocutors says, "I shall overcome you if the court is loyal: I will send the tenso to Pierrefeu, where the fair lady holds her court of instruction." The "court" here in question was a social and not a judicial court. Had any such institution as a judicial "court of love" ever been an integral part of Provençal custom, it is scarcely conceivable that we should be informed of its existence only by a few vague and scattered allusions in the large body of Provençal literature. For these reasons the theory that such an institution existed has been generally rejected by all scholars of repute.

Provençal literature contains examples of almost every poetical genre. Epic poetry is represented by Girart of Roussillon,12 a story of long struggles between Charles Martel and one of his barons, by the Roman de Jaufre, the adventures of a knight of the Round Table, by Flamenca, a love story which provides an admirable picture of the manners and customs of the time, and by other fragments and novelas or shorter stories in the same style. Didactic poetry includes historical works such as the poem of the Albigeois crusade, ethical or moralising ensenhamens and religious poetry. But the dominating element in Provençal literature is lyrical, and during the short classical age of this literature lyric poetry was supreme. Nearly five hundred different troubadours are known to us at least by name and almost a thousand different stanza forms have been enumerated. While examples of the fine careless rapture of inspiration are by no means wanting, artificiality reigns supreme in the majority of cases. Questions of technique receive the most sedulous attention, and the principles of stanza construction, rime correspondence and rime distribution, as evolved by the [23] troubadours, exerted so wide an influence upon other European literature that they deserve a chapter to themselves.

There was no formal school for poetical training during the best period of Provençal lyric. When, for instance, Giraut de Bornelli is said to have gone to "school" during the winter seasons, nothing more is meant than the pursuit of the trivium and quadrivium, the seven arts, which formed the usual subjects of instruction. A troubadour learned the principles of his art from other poets who were well acquainted with the conventions that had been formulated in course of time, conventions which were collected and systematised in such treatises as the Leys d'Amors during the period of the decadence.

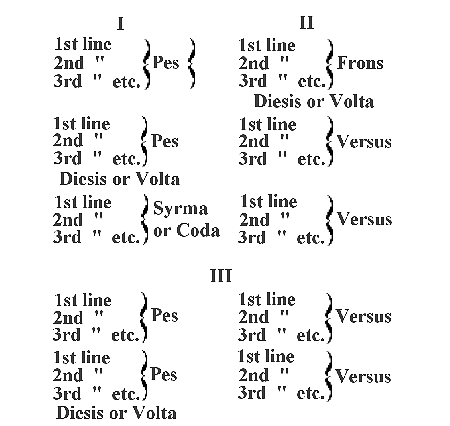

The love song or chanso was composed of five, six or seven stanzas (coblas) with, one or two tornadas or envois. The stanza varied in length from two to forty-two lines, though these limits are, of course, exceptional. An earlier form of the chanso was known as the vers; it seems to have been in closer relation to the popular poetry than the more artificial chanso, and to have had shorter stanzas and lines; but the distinction is not clear. As all poems were intended to be sung, the poet was also a composer; the biography of Jaufre Rudel, for instance, says that this troubadour "made many poems with good tunes but poor [24] words." The tune known as son (diminutive sonnet) was as much the property of a troubadour as his poem, for it implied and would only suit a special form of stanza; hence if another poet borrowed it, acknowledgment was generally made. Dante, in his De Vulgari Eloquentia, informs us concerning the structure of this musical setting: it might be continuous without repetition or division; or it might be in two parts, one repeating the other, in which case the stanza was also divided into two parts, the division being termed by Dante the diesis or volta; of these two parts one might be subdivided into two or even more parts, which parts, in the stanza, corresponded both in rimes and in the arrangement of the lines. If the first part of the stanza was thus divisible, the parts were called pedes, and the musical theme or oda of the first pes was repeated for the second; the rest of the stanza was known as the syrma or coda, and had a musical theme of its own. Again the first part of the stanza might be indivisible, when it was called the frons, the divided parts of the second half being the versus; in this case the frons had its own musical theme, as did the first versus, the theme of the first versus being repeated for the second. Or, lastly, a stanza might [25] consist of pedes and versus, one theme being used for the first pes and repeated for the second and similarly with the versus. Thus the general principle upon which the stanza was constructed was that of tripartition in the following three forms:—

These forms were rather typical than stringently binding as Dante himself notes (De Vulg. El., ii, 11); many variations were [26] possible. The first seems to have been the most popular type. The poem might also conclude with a half stanza or tornada, (French envoi). Here, as in the last couplet of the Arabic gazul, were placed the personal allusions, and when these were unintelligible to the audience the joglar usually explained the poem before singing it; the explanations, which in some cases remain prefixed to the poem, were known as the razos.

Troubadour poems were composed for singing, not for recitation, and the

music of a poem was an element of no less importance than the words.

Troubadours are described as composing "good" tunes and "poor" words, or

vice versa; the tune was a piece of literary property, and, as we have

said, if a troubadour borrowed a tune he was expected to acknowledge its

origin. Consequently music and words were regarded as forming a unity,

and the structure of the one should be a guide to the structure of the

other. Troubadour music is a subject still beset with difficulties13:

we possess 244 tunes written in Gregorian notation, and as in certain

cases the same poem appears in different MSS. with the tune in

substantial agreement in each one, we may reasonably assume that we have

an authentic record, as far as this could be expressed in Gregorian

notation. The chief difference between Troubadour and Gregorian music

lies in the fact that the former was syllabic in character; in other

[27]

words, one note was not held over several syllables, though several

notes might be sung upon one syllable. The system of musical time in the

age of the troubadours was based upon the so-called "modes," rhythmical

formulae combining short and long notes in various sequences. Three of

these concern us here. The first mode consists of a long followed by a

short note, the long being equivalent to two short, or in time

time

. The second mode is the reverse of

the first

. The second mode is the reverse of

the first  . The third mode in modern

. The third mode in modern

time appears as

time appears as  . The principle of

sub-division is thus ternary; "common" time or

. The principle of

sub-division is thus ternary; "common" time or  time is a later

modification. So much being admitted, the problem of transposing a tune

written in Gregorian notation without bars, time signature, marks of

expression or other modern devices is obviously a difficult matter. J.

Beck, who has written most recently upon the subject, formulates the

following rules; the musical accent falls upon the tonic syllables of

the words; should the accent fall upon an atonic syllable, the duration

of the note to which the tonic syllable is sung may be increased, to

avoid the apparent discordance between the musical accent and the tonic

syllable. The musical accent must fall upon the rime and the rhythm

[28]

adopted at the outset will persist throughout the poem.

time is a later

modification. So much being admitted, the problem of transposing a tune

written in Gregorian notation without bars, time signature, marks of

expression or other modern devices is obviously a difficult matter. J.

Beck, who has written most recently upon the subject, formulates the

following rules; the musical accent falls upon the tonic syllables of

the words; should the accent fall upon an atonic syllable, the duration

of the note to which the tonic syllable is sung may be increased, to

avoid the apparent discordance between the musical accent and the tonic

syllable. The musical accent must fall upon the rime and the rhythm

[28]

adopted at the outset will persist throughout the poem.

Hence a study of the words will give the key to the interpretation of the tune. If, for instance, the poem shows accented followed by unaccented syllables or trochees as the prevalent foot, the first "mode" is indicated as providing the principle to be followed in transposing the Gregorian to modern notation. When these conditions are reversed the iambic foot will prevail and the melody will be in the second mode. It is not possible here to treat this complicated question in full detail for which reference must be made to the works of J. Beck. But it is clear that the system above outlined is an improvement upon that proposed by such earlier students of the subject as Riemann, who assumed that each syllable was sung to a note or group of notes of equal time value. There is no evidence that such a rhythm was ever employed in the middle ages, and the fact that words and music were inseparable in Provençal lyrics shows that to infer the nature of the musical rhythm from the rhythm of the words is a perfectly legitimate method of inquiry.

A further question arises: how far do the tunes correspond with the structure of the stanza as given by Dante? In some cases both tune and stanza correspond in symmetrical form; but in others we find stanzas [29] which may be divided according to rule conjoined with tunes which present no melodic repetition of any kind; similarly, tunes which may be divided into pedes and coda are written upon stanzas which have no relation to that form. On the whole, it seems that the number of tunes known to us are too few, in comparison with the large body of lyric poetry existing, to permit any generalisation upon the question. The singer accompanied himself upon a stringed instrument (viula) or was accompanied by other performers; various forms of wind instruments were also in use. Apparently the accompaniment was in unison with the singer; part writing or contrapuntal music was unknown at the troubadour period.

As has been said, the stanza (cobla) might vary in length. No poetical literature has made more use of rime than Provençal lyric poetry. There were three typical methods of rime disposition: firstly, the rimes might all find their answer within the stanza, which was thus a self-contained whole; secondly, the rimes might find their answer within the stanza and be again repeated in the same order in all following stanzas; and thirdly, the rimes might find no answer within the stanza, but be repeated in following stanzas. In this case the rimes were known as dissolutas, and the stanza as a cobla estrampa. This last arrangement tended to make the poem a more organic whole than was possible in the first two cases; in these, stanzas might be omitted without necessarily impairing the general effect, but, when coblas estrampas were employed, the ear of the auditor, attentive for the [30] answering rimes, would not be satisfied before the conclusion of the second stanza. A further step towards the provision of closer unity between the separate stanzas was the chanso redonda, which was composed of coblas estrampas, the rime order of the second stanza being an inversion of the rime order of the first; the tendency reaches its highest point in the sestina, which retained the characteristic of the chanso redonda, namely, that the last rime of one stanza should correspond with the first rime of the following stanza, but with the additional improvement that every rime started a stanza in turn, whereas, in the chanso redonda the same rime continually recurred at the beginning of every other stanza.

Reference has already been made to the chanso. A poetical form of much importance was the sirventes, which outwardly was indistinguishable from the chanso. The meaning of the term is unknown; some say that it originally implied a poem composed by "servants," poets in the service of an overlord; others, that it was a poem composed to the tune of a [31] chanso which it thus imitated in a "servile" manner. From the chanso the sirventes is distinguished by its subject matter; it was the vehicle for satire, moral reproof or political lampooning. The troubadours were often keenly interested in the political events of their time; they filled, to some extent, the place of the modern journalist and were naturally the partisans of the overlord in whose service or pay they happened to be. They were ready to foment a war, to lampoon a stingy patron, to ridicule one another, to abuse the morality of the age as circumstances might dictate. The crusade sirventes14 are important in this connection, and there were often eloquent exhortations to the leaders of Christianity to come to the rescue of Palestine and the Holy Sepulchre. Under this heading also falls the planh, a funeral song lamenting the death of a patron, and here again, beneath the mask of conventionality, real emotion is often apparent, as in the famous lament upon Richard Coeur de Lion composed by Gaucelm Faidit.

Reference has been already made to the tenso, one of the most characteristic of Provençal lyric forms. The name (Lat. tentionem) implies a contention or strife, which was conducted in the form of a dialogue and possibly owed its origin to the custom in early vogue among many different peoples of holding poetical tournaments, in which one [32] poet challenged another by uttering a poetical phrase to which the opponent replied in similar metrical form. Such, at any rate, is the form of the tenso; a poet propounds a theme in the first stanza and his interlocutor replies in a stanza of identical metrical form; the dispute usually continues for some half dozen stanzas. One class of tenso was obviously fictitious, as the dialogue is carried on with animals or even lifeless objects, such as a lady's cloak, and it is possible that some at least of the discussions ostensibly conducted between two poets may have emanated from the brain of one sole author. Sometimes three or four interlocutors take part; the subject of discussion was then known as a joc partit, a divided game, or partimen, a title eventually transferred to the poem itself. The most varied questions were discussed in the tenso, but casuistical problems concerning love are the most frequent: Is the death or the treachery of a loved one easier to bear? Is a lover's feeling for his lady stronger before she has accepted him or afterwards? Is a bad noble or a poor but upright man more worthy to find favour? The discussion of such questions provided an opportunity of displaying both poetical dexterity and also dialectical acumen. But rarely did either of the disputants declare himself convinced or vanquished by his opponents' arguments the question [33] was left undecided or was referred by agreement to an arbitrator.

A poetical form which preserves some trace of its popular origin is the pastorela15 or pastoral which takes its name from the fact that the heroine of the piece was always a shepherdess. The conventional opening is a description by a knight of his meeting with a shepherdess, "the other day" (l'autrier, the word with which the poem usually begins). A dialogue then follows between the knight and the shepherdess, in which the former sues for her favours successfully or otherwise. The irony or sarcasm which enables the shepherdess to hold her own in the encounter is far removed from the simplicity of popular poetry. The Leys d'Amors mentions other forms of the same genre such as vaqueira (cowherd), auqueira (goose girl), of which a specimen of the first-named alone has survived. Of equal interest is the alba or dawn-song, in which the word alba reappeared as a refrain in each verse; the subject of the poem is the parting of the lovers at the dawn, the approach of which is announced by a watchman or by some faithful friend who has undertaken to guard their meeting-place throughout the night. The counterpart of this form, the serena, does not appear until late in the history of Provençal lyric poetry; in the serena the lover longs for the [34] approach of evening, which is to unite him with his beloved.

Other forms of minor importance were the comjat in which a troubadour bids a lady a final farewell, and the escondig or justification in which the lover attempts to excuse his behaviour to a lady whose anger he had aroused. The troubled state of his feelings might find expression in the descort (discord), in which each stanza showed a change of metre and melody. The descort of Raimbaut de Vaqueiras is written in five dialects, one for each stanza, and the last and sixth stanza of the poem gives two lines to each dialect, which Babel of strange sounds is intended, he says, to show how entirely his lady's heart has changed towards him. The ballata and the estampida were dance-songs, but very few examples survive. Certain love letters also remain to us, but as these are written in rimed couplets and in narrative style, they can hardly be classified as lyric poetry.

In conclusion, a word must be said concerning the dispute between two schools of stylists, which is one of the most interesting points in the literary history of the troubadours.16 From the earliest times we find two poetical schools in opposition, the trobar clus (also known as car, ric, oscur, sotil, cobert), the obscure, or close, subtle style of composition, and the trobar clar (leu, leugier, plan), the clear, light, easy, straightforward style. Two or three causes may have [35] combined to favour the development of obscure writing. The theme of love with which the chanso dealt is a subject by no means inexhaustible; there was a continual struggle to revivify the well-worn tale by means of strange turns of expression, by the use of unusual adjectives and forced metaphor, by the discovery of difficult rimes (rimes cars) and stanza schemes of extraordinary complexity. Marcabrun asserts, possibly in jest, that he could not always understand his own poems. A further and possibly an earlier cause of obscurity in expression was the fact that the chanso was a love song addressed to a married lady; and though in many cases it was the fact that the poem embodied compliments purely conventional, however exaggerated to our ideas, yet the further fact remains that the sentiments expressed might as easily be those of veritable passion, and, in view of a husband's existence, obscurity had a utility of its own. This point Guiraut de Bornelh advances as an objection to the use of the easy style: "I should like to send my song to my lady, if I should find a messenger; but if I made another my spokesman, I fear she would blame me. For there is no sense in making another speak out what one wishes to conceal and keep to oneself." The [36] habit of alluding to the lady addressed under a senhal, or pseudonym, in the course of the poem, is evidence for a need of privacy, though this custom was also conventionalised, and we find men as well as women alluded to under a senhal. It was not always the fact that the senhal was an open secret, although in many cases, where a high-born dame desired to boast of the accomplished troubadour in her service, his poems would naturally secure the widest publication which she could procure. A further reason for complexity of composition is given by the troubadour Peire d'Auvergne: "He is pleasing and agreeable to me who proceeds to sing with words shut up and obscure, to which a man is afraid to do violence." The "violence" apprehended is that of the joglar, who might garble a song in the performance of it, if he had not the memory or industry to learn it perfectly, and Peire d'Alvernhe (1158-80) commends compositions so constructed that the disposition of the rimes will prevent the interpolation of topical allusions or careless altercation. The similar safeguard of Dante's terza rima will occur to every student.

The social conditions again under which troubadour poetry was produced, apart from the limitations of its subject matter, tended to foster an obscure and highly artificial diction. This obscurity was attained, as we have said, by elevation and preciosity of style, and was not the result of confusion of thought. Guiraut de Bornelh tells us his method [37] in a passage worth quoting in the original—

Mas per melhs assire

mon chan,

vau cercan

bos motz en fre

que son tuit cargat e ple

d'us estranhs sens naturals;

mas no sabon tuich de cals.

"But for the better foundation of my song I keep on the watch for words good on the rein (i.e. tractable like horses), which are all loaded (like pack horses) and full of a meaning which is unusual, and yet is wholly theirs (naturals); but it is not everyone that knows what that meaning is".17

Difficulty was thus intentional; in the case of several troubadours it affected the whole of their writing, no matter what the subject matter. They desired not to be understood of the people. Dean Gaisford's reputed address to his divinity lecture illustrates the attitude of those troubadours who affected the trobar clus: "Gentlemen, a knowledge of Greek will enable you to read the oracles of God in the original and to look down from the heights of scholarship upon the vulgar herd." The inevitable reaction occurred, and a movement in the opposite direction was begun; of this movement the most distinguished supporter was the troubadour, Guiraut de Bornelh. He had been one of the most successful [38] exponents of the trobar clus, and afterwards supported the cause of the trobar clar. Current arguments for either cause are set forth in the tenso between Guiraut de Bornelh and Linhaure (pseudonym for the troubadour Raimbaut d'Aurenga).

(1) I should like to know, G. de Bornelh, why, and for what reason, you keep blaming the obscure style. Tell me if you prize so highly that which is common to all? For then would all be equal.

(2) Sir Linhaure, I do not take it to heart if each man composes as he pleases; but judge that song is more loved and prized which is made easy and simple, and do not be vexed at my opinion.

(3) Guiraut, I do not like my songs to be so confused, that the base and good, the small and great be appraised alike; my poetry will never be praised by fools, for they have no understanding nor care for what is more precious and valuable.

(4) Linhaure, if I work late and turn my rest into weariness for that reason (to make my songs simple), does it seem that I am afraid of work? Why compose if you do not want all to understand? Song brings no other advantage.

(5) Guiraut, provided that I produce what is best at all times, I care not if it be not so widespread; commonplaces are no good for the appreciative—that is why gold is more valued than salt, and with song [39] it is even the same.

It is obvious that the disputants are at cross purposes; the object of writing poetry, according to the one, is to please a small circle of highly trained admirers by the display of technical skill. Guiraut de Bornelh, on the other hand, believes that the poet should have a message for the people, and that even the fools should be able to understand its purport. He adds the further statement that composition in the easy style demands no less skill and power than is required for the production of obscurity. This latter is a point upon which he repeatedly insists: "The troubadour who makes his meaning clear is just as clever as he who cunningly conjoins words." "My opinion is that it is not in obscure but in clear composition that toil is involved." Later troubadours of renown supported his arguments; Raimon de Miraval (1168-1180) declares: "Never should obscure poetry be praised, for it is composed only for a price, compared with sweet festal songs, easy to learn, such as I sing." So, too, pronounces the Italian Lanfranc Cigala (1241-1257): "I could easily compose an obscure, subtle poem if I wished; but no poem should be so concealed beneath subtlety as not to be clear as day. For knowledge is of small value if clearness does not bring light; obscurity has ever been regarded as death, and brightness [40] as life." The fact is thus sufficiently demonstrated that these two styles existed in opposition, and that any one troubadour might practise both.

Enough has now been said to show that troubadour lyric poetry, regarded as literature, would soon produce a surfeit, if read in bulk. It is essentially a literature of artificiality and polish. Its importance consists in the fact that it was the first literature to emphasise the value of form in poetry, to formulate rules, and, in short, to show that art must be based upon scientific knowledge. The work of the troubadours in these respects left an indelible impression upon the general course of European literature.

The earliest troubadour known to us is William IX, Count of Poitiers (1071-1127) who led an army of thirty thousand men to the unfortunate crusade of 1101. He lived an adventurous and often an unedifying life, and seems to have been a jovial sensualist caring little what kind of reputation he might obtain in the eyes of the world about him. William of Malmesbury gives an account of him which is the reverse of respectable. His poems, of which twelve survive, are, to some extent, a reflection of this character, and present a mixture of coarseness and delicate sentiment which are in strangely discordant contrast. His versification is of an early type; the principle of tripartition, which became predominant in troubadour poetry at a later date, is hardly perceptible in his poems. The chief point of interest in them is the fact that their comparative perfection of form implies a long anterior course of development for troubadour poetry, while we also find him employing, though in undeveloped form, the chief ideas which afterwards became commonplaces among the troubadours. The half mystical exaltation inspired by love is already known to William IX. as joi, and he is [42] acquainted with the service of love under feudal conditions. The conventional attitudes of the lady and the lover are also taken for granted, the lady disdainful and unbending, the lover timid and relying upon his patience. The lady is praised for her outward qualities, her "kindly welcome, her gracious and pleasing look" and love for her is considered to be the inspiration of nobility in the lover. But these ideas are not carried to the extravagant lengths to which later poets pushed them; William's sensual leanings are enough to counterbalance any tendency to such exaggeration. The conventional opening of a love poem by a description of spring is also in evidence; in short, the commonplaces, the technical language and formulae of later Provençal lyrics were in existence during the age of this first troubadour.

Next in point of time is the troubadour Cercamon, of whom we know very little; his poems, as we have them, seem to fall between the years 1137 and 1152; one of them is a lament upon the death of William X. of Aquitaine, the son of the notorious Count of Poitiers, and another alludes to the marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine, the daughter of William X. According to the Provençal biography he was the instructor of a more interesting and original troubadour Marcabrun, whose active life [43] extended from 1150 to 1195. Many of his poems are extremely obscure; he was one of the first to affect the trobar clus. He was also the author of violent invectives against the passion of love—

Que anc non amet neguna

Ni d'autra no fon amatz—

"Who never loved any woman nor was loved of any." This aversion to the main theme of troubadour poetry is Marcabrun's most striking characteristic.

Amors es mout de mal avi;

Mil homes a mortz ses glavi;

Dieus non fetz tant fort gramavi.

"Love is of a detestable lineage; he has killed thousands of men without a sword. God has created no more terrible enchanter." These invectives may have been the outcome of personal disappointment; the theory has also been advanced that the troubadour idea of love had not yet secured universal recognition, and that Marcabrun is one who strove to prevent it from becoming the dominant theme of lyric poetry. His best known poem was the "Starling," which consists of two parts, an unusual form of composition. In the first part the troubadour sends the starling to his love to reproach her for unfaithfulness, and to recommend himself to her favour; the bird returns, and in the second part offers excuses from the [44] lady and brings an invitation from her to a meeting the next day. Marcabrun knows the technical terms cortesia and mesura, which he defines: mesura, self-control or moderation, "consists in nicety of speech, courtesy in loving. He may boast of courtesy who can maintain moderation." The poem concludes with a dedication to Jaufre Rudel—

Lo vers e·l son vueill envier

A'n Jaufre Rudel outra mar.

"The words and the tune I wish to send to Jaufre Rudel beyond the sea."

This was the troubadour whom Petrarch has made famous—

Jaufre Rudel che usò la vela e'l remo

A cercar la sua morte.

His romantic story is as follows in the words of the Provençal biography: "Jaufre Rudel of Blaya was a very noble man, the Prince of Blaya; he fell in love with the Countess of Tripoli, though he had never seen her, for the good report that he had of her from the pilgrims who came from Antioch, and he made many poems concerning her with good tunes but poor words.18 And from desire to see her, he took the cross and went to sea. And in the ship great illness came upon him so that those who were with him thought that he was dead in the ship; but they [45] succeeded in bringing him to Tripoli, to an inn, as one dead. And it was told to the countess, and she came to him, to his bed, and took him in her arms; and he knew that she was the countess, and recovering his senses, he praised God and gave thanks that his life had been sustained until he had seen her; and then he died in the lady's arms. And she gave him honourable burial in the house of the Temple, and then, on that day, she took the veil for the grief that she had for him and for his death." Jaufre's poems contain many references to a "distant love" which he will never see, "for his destiny is to love without being loved." Those critics who accept the truth of the story regard Melisanda, daughter of Raimon I., Count of Tripoli, as the heroine; but the biography must be used with great caution as a historical source, and the mention of the house of the order of Templars in which Jaufre is said to have been buried raises a difficulty; it was erected in 1118, and in the year 1200 the County of Tripoli was merged in that of Antioch; of the Rudels of Blaya, historically known to us, there is none who falls reasonably within these dates. The probability is that the constant references in Jaufre's poems to an unknown distant love, and the fact of his crusading expedition to the Holy Land, formed in conjunction the nucleus of the [46] legend which grew round his name, and which is known to all readers of Carducci, Uhland and Heine.

Contemporary with Jaufre Rudel was Bernard de Ventadour, one of the greatest names in Provençal poetry. According to the biography, which betrays its untrustworthiness by contradicting the facts of history, Bernard was the son of the furnace stoker at the castle of Ventadour, under the Viscount Ebles II., himself a troubadour and a patron of troubadours. It was from the viscount that Bernard received instruction in the troubadours' art, and to his patron's interest in his talents he doubtless owed the opportunities which he enjoyed of learning to read and write, and of making acquaintance with such Latin authors as were currently read, or with the anthologies and books of "sentences" then used for instruction in Latin. He soon outstripped his patron, to whose wife, Agnes de Montluçon, his early poems were addressed. His relations with the lady and with his patron were disturbed by the lauzengiers, the slanderers, the envious, and the backbiters of whom troubadours constantly complain, and he was obliged to leave Ventadour. He went to the court of Eleanor of Aquitaine, the granddaughter of the first troubadour, Guillaume IX. of Poitiers, who by tradition and temperament was a patroness of troubadours, many of whom sang her praises. She had [47] been divorced from Louis VII. of France in 1152, and married Henry, Duke of Normandy, afterwards King of England in the same year. There Bernard may have remained until 1154, in which year Eleanor went to England as Queen. Whether Bernard followed her to England is uncertain; the personal allusions in his poems are generally scanty, and the details of his life are correspondingly obscure. But one poem seems to indicate that he may have crossed the Channel. He says that he has kept silence for two years, but that the autumn season impels him to sing; in spite of his love, his lady will not deign to reply to him: but his devotion is unchanged and she may sell him or give him away if she pleases. She does him wrong in failing to call him to her chamber that he may remove her shoes humbly upon his knees, when she deigns to stretch forth her foot. He then continues19

Faitz es lo vers totz a randa,

Si que motz no y descapduelha.

outra la terra normanda

part la fera mar prionda;

e si·m suy de midons lunhans.

yes si·m tira cum diamans,

la belha cui dieus defenda.

Si·l reys engles el dux normans

o vol, ieu la veirai, abans

que l'iverns nos sobreprenda.

"The vers has been composed fully so that not a word is wanting, [48] beyond the Norman land and the deep wild sea; and though I am far from my lady, she attracts me like a magnet, the fair one whom may God protect. If the English king and Norman duke will, I shall see her before the winter surprise us."

How long Bernard remained in Normandy, we cannot conjecture. He is said to have gone to the court of Raimon V., Count of Toulouse, a well-known patron of the troubadours. On Raimon's death in 1194, Bernard, who must himself have been growing old, retired to the abbey of Dalon in his native province of Limousin, where he died. He is perhaps more deeply inspired by the true spirit of lyric poetry than any other troubadour; he insists that love is the only source of song; poetry to be real, must be lived.

Non es meravelha s'ieu chan

mielhs de nulh autre chantador;

que plus mi tra·l cors ves amor

e mielhs sui faitz a son coman.

"It is no wonder if I sing better than any other singer; for my heart draws me more than others towards love, and I am better made for his commandments." Hence Bernard gave fuller expression than any other troubadour to the ennobling power of love, as the only source of real worth and nobility.

The subject speedily became exhausted, and ingenuity did but increase [49] the conventionality of its treatment. But in Bernard's hands it retains its early freshness and sincerity. The description of the seasons of the year as impelling the troubadour to song was, or became, an entirely conventional and expected opening to a chanso; but in Bernard's case these descriptions were marked by the observation and feeling of one who had a real love for the country and for nature, and the contrast or comparison between the season of the year and his own feelings is of real lyrical value. The opening with the description of the lark is famous—

Quant vey la lauzeta mover

De joi sas alas contral rai,

que s'oblida e·s laissa cazer

per la doussor qu'al cor li vai,

ai! tan grans enveia m'en ve

de cui qu'eu veya jauzion!

meravilhas ai, quar desse

lo cor de dezirier no·m fon.

"When I see the lark flutter with joy towards the sun, and forget himself and sing for the sweetness that comes to his heart; alas, such envy comes upon me of all that I see rejoicing, I wonder that my heart does not melt forthwith with desire".20

At the same time Bernard's style is simple and clear, though he shows full mastery of the complex stanza form; to call him the Wordsworth of the troubadour world is to exaggerate a single point of coincidence; but he remains the greatest of troubadour poets, as modern taste regards [50] poetry.

Arnaut de Mareuil (1170-1200 circa) displays many of the characteristics which distinguished the poetry of Bernard of Ventadour; there is the same simplicity of style and often no less reality of feeling: conventionalism had not yet become typical. Arnaut was born in Périgord of poor parents, and was brought up to the profession of a scribe or notary. This profession he soon abandoned, and his "good star," to quote the Provençal biography, led him to the court of Adelaide, daughter of Raimon V. of Toulouse, who had married in 1171 Roger II., Viscount of Béziers. There he soon rose into high repute: at first he is said to have denied his authorship of the songs which he composed in honour of his mistress, but eventually he betrayed himself and was recognised as a troubadour of high merit, and definitely installed as the singer of Adelaide. The story is improbable, as the troubadour's rewards naturally depended upon the favour of his patrons to him personally; it is probably an instance of the manner in which the biographies founded fictions upon a very meagre substratum of fact, the fact in this instance being a passage in which Arnaut declares his timidity in singing the praise of so great a beauty as Adelaide.

"But great fear and great apprehension comes upon me, so that I dare not tell you, lady, that it is I who sing of you."

Arnaut seems to have introduced a new poetical genre into Provençal literature, the love-letter. He says that the difficulty of finding a trustworthy messenger induced him to send a letter sealed with his own ring; the letter is interesting for the description of feminine beauty which it contains: "my heart, that is your constant companion, comes to me as your messenger and portrays for me your noble, graceful form, your fair light-brown hair, your brow whiter than the lily, your gay laughing eyes, your straight well-formed nose, your fresh complexion, whiter and redder than any flower, your little mouth, your fair teeth, whiter than pure silver,... your fair white hands with the smooth and slender fingers"; in short, a picture which shows that troubadour ideas of beauty were much the same as those of any other age. Arnaut was eventually obliged to leave Béziers, owing, it is said, to the rivalry of Alfonso II. of Aragon, who may have come forward as a suitor for Adelaide after Roger's death in 1194. The troubadour betook himself to the court of William VIII., Count of Montpelier, where he probably spent the rest of his life. The various allusions in his poems cannot always [52] be identified, and his career is only known to us in vague outline. Apart from the love-letter, he was, if not the initiator, one of the earliest writers of the type of didactic poem known as ensenhamen, an "instruction" containing observations upon the manners and customs of his age, with precepts for the observance of morality and right conduct such as should be practised by the ideal character. Arnaut, after a lengthy and would-be learned introduction, explains that each of the three estates, the knights, the clergy and the citizens, have their special and appropriate virtues. The emphasis with which he describes the good qualities of the citizen class, a compliment unusual in the aristocratic poetry of the troubadours, may be taken as confirmation of the statement concerning his own parentage which we find in his biography.

We now reach a group of three troubadours whom Dante21 selected as typical of certain characteristics: "Bertran de Born sung of arms, Arnaut Daniel of love, and Guiraut de Bornelh of uprightness, honour and virtue." The last named, who was a contemporary (1175-1220 circa) and compatriot of Arnaut de Marueil, is said in his biography to have enjoyed so great a reputation that he was known as the "Master of the Troubadours." This title is not awarded to him by any other troubadour; the jealousy constantly prevailing between the troubadours is enough to account for their silence on this point. But his reputation is fairly attested by the number of his poems which have survived and by the numerous MSS. in which they are preserved; when troubadours were studied as classics in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Guiraut's poems were so far in harmony with the moralising tendency of that age that his posthumous reputation was certainly as great as any that he enjoyed in his life-time.

Practically nothing is known of his life; allusions in his poems lead us [54] to suppose that he spent some time in Spain at the courts of Navarre, Castile and Aragon. The real interests of his work are literary and ethical. To his share in the controversy concerning the trobar clus, the obscure and difficult style of composition, we have already alluded. Though in the tenso with Linhaure, Guiraut expresses his preference for the simple and intelligible style, it must be said that the majority of his poems are far from attaining this ideal. Their obscurity, however, is often due rather to the difficulty of the subject matter than to any intentional attempt at preciosity of style. He was one of the first troubadours who attempted to analyse the effects of love from a psychological standpoint; his analysis often proceeds in the form of a dialogue with himself, an attempt to show the hearer by what methods he arrived at his conclusions. "How is it, in the name of God, that when I wish to sing, I weep? Can the reason be that love has conquered me? And does love bring me no delight? Yes, delight is mine. Then why am I sad and melancholy? I cannot tell. I have lost my lady's favour and the delight of love has no more sweetness for me. Had ever a lover such misfortune? But am I a lover? No! Have I ceased to love passionately? No! Am I then a lover? Yes, if my lady would suffer my love." Guiraut's [55] moral sirventes are reprobations of the decadence of his age. He saw a gradual decline of the true spirit of chivalry. The great lords were fonder of war and pillage than of poetry and courtly state. He had himself suffered from the change, if his biographer is to be believed; the Viscount of Limoges had plundered and burnt his house. He compares the evils of his own day with the splendours of the past, and asks whether the accident of birth is the real source of nobility; a man must be judged by himself and his acts and not by the rank of his forefathers; these were the sentiments that gained him a mention in the Fourth Book of Dante's Convivio.22

The question why Dante should have preferred Arnaut Daniel to Guiraut de Bornelh23 has given rise to much discussion. The solution turns upon Dante's conception of style, which is too large a problem for consideration here. Dante preferred the difficult and artificial style of Arnaut to the simple style of the opposition school; from Arnaut he borrowed the sestina form; and at the end of the canto he puts the well-known lines, "Ieu sui Arnaut, que plor e vau cantan," into the troubadour's mouth. We know little of Arnaut's life; he was a noble of Riberac in Périgord. The biography relates an incident in his life which is said to have taken place at the court of Richard Coeur de Lion.

A certain troubadour had boasted before the king that he could compose a [56] better poem than Arnaut. The latter accepted the challenge and the king confined the poets to their rooms for a certain time at the end of which they were to recite their composition before him. Arnaut's inspiration totally failed him, but from his room he could hear his rival singing as he rehearsed his own composition. Arnaut was able to learn his rival's poem by heart, and when the time of trial came he asked to be allowed to sing first, and performed his opponent's song, to the wrath of the latter, who protested vigorously. Arnaut acknowledged the trick, to the great amusement of the king.

Preciosity and artificiality reach their height in Arnaut's poems, which are, for that reason, excessively difficult. Enigmatic constructions, word-plays, words used in forced senses, continual alliteration and difficult rimes produced elaborate form and great obscurity of meaning. The following stanza may serve as an example—

L'aur' amara fa·ls bruels brancutz

clarzir que·l dons espeys' ab fuelhs,

e·ls letz becxs dels auzels ramencx

te balbs e mutz pars e non pars.

per qu'ieu m'esfortz de far e dir plazers

A manhs? per ley qui m'a virat has d'aut,

don tern morir si·ls afans no·m asoma.

"The bitter breeze makes light the bosky boughs which the gentle breeze [57] makes thick with leaves, and the joyous beaks of the birds in the branches it keeps silent and dumb, paired and not paired. Wherefore do I strive to say and do what is pleasing to many? For her, who has cast me down from on high, for which I fear to die, if she does not end the sorrow for me."

The answers to the seventeen rime-words which occur in this stanza do not appear till the following stanza, the same rimes being kept throughout the six stanzas of the poem. To rest the listener's ear, while he waited for the answering rimes, Arnaut used light assonances which almost amount to rime in some cases. The Monk of Montaudon in his satirical sirventes says of Arnaut: "He has sung nothing all his life, except a few foolish verses which no one understands"; and we may reasonably suppose that Arnaut's poetry was as obscure to many of his contemporaries as it is to us.

Dante placed Bertran de Born in hell, as a sower of strife between father and son, and there is no need to describe his picture of the troubadour—

"Who held the severed member lanternwise

And said, Ah me!" (Inf. xxviii. 119-142.)

The genius of Dante, and the poetical fame of Bertran himself, have given him a more important position in history than is, perhaps, [58] entirely his due. Jaufré, the prior of Vigeois, an abbey of Saint-Martial of Limoges, is the only chronicler during the reigns of Henry II. and Richard Coeur de Lion who mentions Bertran's name. The razos prefixed to some of his poems by way of explanation are the work of an anonymous troubadour (possibly Uc de Saint-Círe); they constantly misinterpret the poems they attempt to explain, confuse names and events, and rather exaggerate the part played by Bertran himself. Besides these sources we have the cartulary of Dalon, or rather the extracts made from it by Guignières in 1680 (the original has been lost), which give us information about Bertran's family and possessions. From these materials, and from forty-four or forty-five poems which have come down to us, the poet's life can be reconstructed.

Bertran de Bern's estates were situated on the borders of Limousin and Périgord. The family was ancient and honourable; from the cartulary Bertran appears to have been born about 1140; we find him, with his brother Constantin, in possession of the castle of Hautefort, which seems to have been a strong fortress; the lands belonging to the family were of no great extent, and the income accruing from them was but scanty. In 1179 Bertran married one Raimonde, of whom nothing is known, except that she bore him at least two sons. In 1192 he lost this first [59] wife, and again married a certain Philippe. His warlike and turbulent character was the natural outcome of the conditions under which he lived; the feudal system divided the country into a number of fiefs, the boundaries of which were ill defined, while the lords were constantly at war with one another. All owed allegiance to the Duke of Aquitaine, the Count of Poitou, but his suzerainty was, in the majority of cases, rather a name than a reality. These divisions were further accentuated by political events; in 1152 Henry II., Count of Anjou and Maine, married Eleanor, the divorced wife of Louis VII. of France, and mistress of Aquitaine. Henry became king of England two years later, and his rule over the barons of Aquitaine, which had never been strict, became the more relaxed owing to his continual absence in England.