Title: The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 356, February 14, 1829

Author: Various

Release date: May 1, 2004 [eBook #12477]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/12477

Credits: Produced by Jonathan Ingram, David Garcia and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team.

| VOL. XIII, NO. 356.] | SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 14, 1829. | [PRICE 2d. |

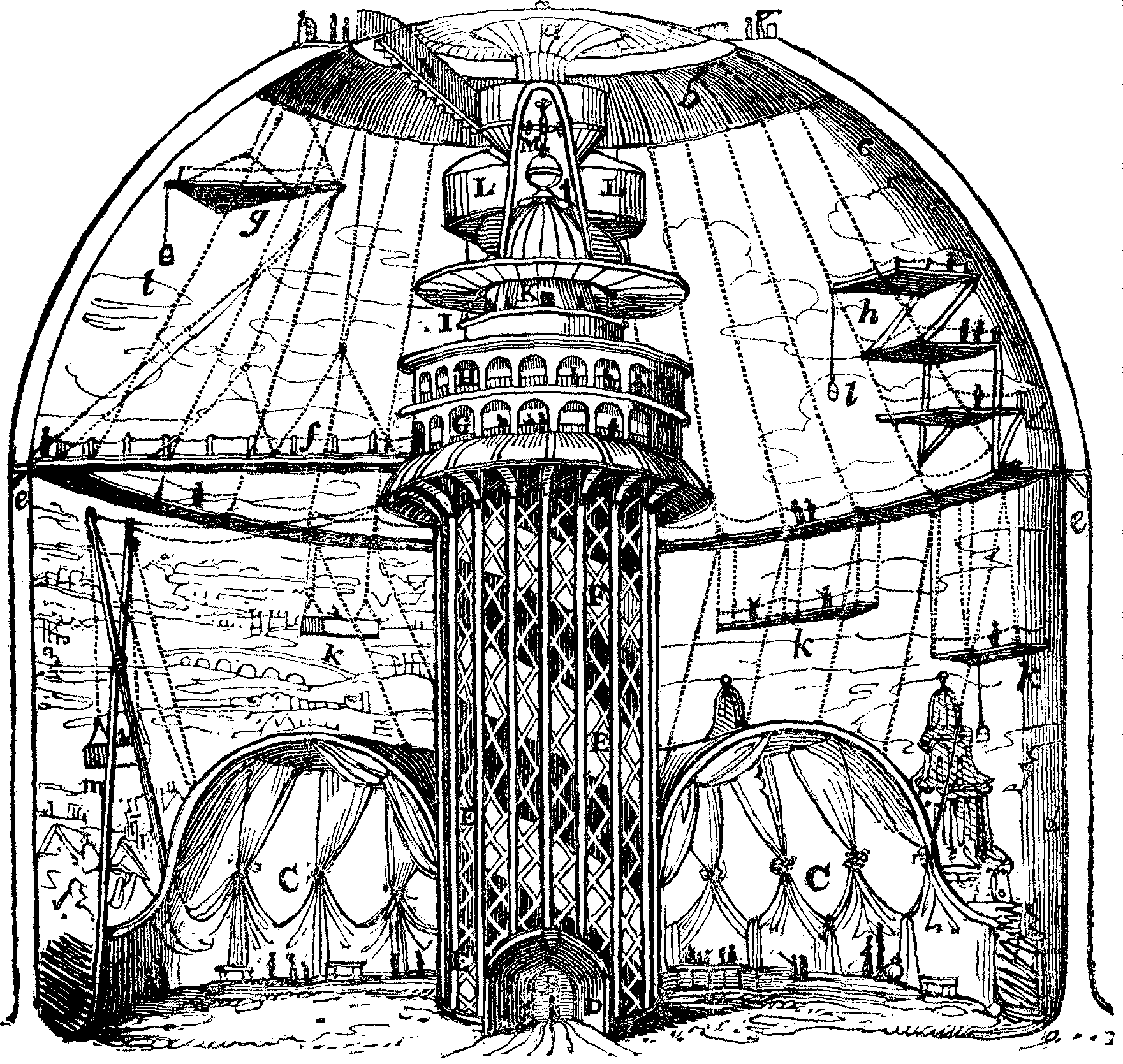

References to the Engraving.

A. Column or Tower in the centre of the building, for supporting the Ascending Room, &c.

B. Entrance to the Ascending-Room.

C. Saloon for the reception of works of art.

D. Passage lending to the Saloon, Galleries, and Ascending-Room.

E. F. Two separate Spiral Flights of Steps, leading to the Galleries, &c.

G. H. I. Galleries from which the Picture is to be viewed.

K. Refreshment-Room.

L. Rooms for Music or Bells.

M. The Old Ball from St. Paul's Cathedral.

N. Stairs leading to the outside of the Building. a. b. Sky-lights. c. Plaster Dome, on which the sky is painted, d. Canvass on which the part of the picture up to the horizon is painted. e. Gallery, suspended by ropes, used for painting the distance, and uniting the plaster and the canvas. f. Temporary Bridge from the Gallery G to the Gallery e. from the end of which the echo of the building might be heard to the greatest advantage. g. One of Fifteen Triangular Platforms, used for painting the sky. h. Platforms fixed on the ropes of the Gallery e, used for finishing and clouding the sky. k. Different methods for getting at the lower parts of the canvas. l. Baskets for conveying colours. &c. to the artists, m. Cross or Shears, formed of two poles, from which a cradle or box is suspended, for finishing the picture after the removal of all the scaffolding and ropes.

Mr. Hornor, in his colossal undertaking, has "devised a mean" to draw us out of the way; and a successful one it has already proved. As a return for [pg 98] the interest which his enterprise has excited, we are, however, induced to present its details to our readers, as perfect as the limits of the MIRROR will allow; and for this purpose we have been favoured by Mr. Parris with the drawing for the annexed cut.

In No. 352, we gave a popular description of the interior of the Colosseum; but the reader's attention was therein directed to the splendid effect of the panorama or picture, whilst the means by which the painting was executed have been reserved for our present Number. This we have endeavoured to illustrate by the annexed engraving; and the explanation will be rendered still clearer by reference to No. 352, wherein we have given an outline of the difficulties with which the principal artist, Mr. Parris, had to contend in painting the panorama. We, however, omitted to state an obstacle equally formidable with the reconciliation of the styles of the several artists engaged to assist Mr. Parris. This additional source of perplexity was the great change, almost amounting to the vitrification of enamel colours, which occurred in the hues of the various pigments, according to the point of view, and the immense distance of the canvas from the spectator.

Besides furnishing the reader with the construction of the apartments, galleries, and ascents of the interior, the engraving presents some idea of the scaffoldings, bridges, platforms, and other mechanical contrivances requisite for the execution of the picture.

The spiral staircase, it will be seen, leads to the lower gallery for viewing the picture. Unconnected with the intermediate gallery, there is a communication from the lowest gallery to the highest, and thence to the refreshment-rooms and exterior of the dome. The ascent to the second price gallery is by a spiral staircase under those already mentioned. The column, or central erection, containing these staircases and the ascending-room, is of timber, with twelve principal uprights seventy-three feet high, one foot square, set upon a circular curb of brickwork, hooped with iron, and further secured by bracing, and by two other circular curbs, from the upper one of which rises a cone of timbers thirty-four feet high, supporting the refreshment-rooms, the identical ball, and model of the cross, of St. Paul's, Mr. Hornor's sketching cabin, staircase to the exterior, &c. Without the circle of timbers already described, is another of twenty-four upright timbers; and between these two circles the staircases wind. The architectural fronts of the galleries form frame-works, through which the spectator may enjoy various parts of the panorama, as in so many distinct pictures.

The cut and appended references will explain the devices for painting better than a more extended description; for mere words do not facilitate the understanding of inventions which in themselves are beautiful and simple. To heighten the effect, our artist has, however, introduced light sketchy outlines of the campanile towers of St. Paul's, the city, and the distant country. Mr. Parris's task must have been one of extreme peril, and notwithstanding his ingenious contrivances of galleries, bridges, platforms, &c. he fell twice from a considerable height; but in neither case was he seriously hurt. His progress reminds us of other grand flights to fame, but his success has been triumphant, and alike honourable to his genius and enterprise. In short, looking at the present advanced state of the Colosseum, Mr. Hornor and his indefatigable coadjutors may almost exclaim in the words of Dryden,

"Our toils, my friend, are crown'd with sure success:

The greater part perform'd, achieve the less."

St. Peter's church, Dorchester, is a handsome structure. There is a traditional rhyme about it which imports the founder of this church to have been Geoffery Van.

"Geoffery Van

With his wife Anne

And his maid Nan

Built this church."

But there was long since dug up in a garden here a large seal, with indisputable marks of antiquity, and this inscription:—"Sigillum Galfridi de Ann." It is therefore supposed, with some reason, that the founder's name was Ann.

A great number and variety of Roman coins have been dug up in this town, some of silver, others of copper, called by the common people, King Dorn's Pence; for they have a notion that one king Dorn was the founder of Dorchester.

Ut Rosa flos florum

Sic est domus ista domorum.

Such was the encomium bestowed on the venerable pile of York Minster by an [pg 99] old monkish writer; but, alas! what a change is there in the space of a few short hours; what a scene of desolation, what a lesson of the instability of sublunary things and the vanity of human grandeur! The glory of the city of York, of England, yea, almost of Europe, is now, through the fanaticism of a modern Erostratus, rendered comparatively a pile of ruin; but still

"Looks great in ruin, noble in decay."

This is the third time that this magnificent structure has been assailed by fire; twice it has been totally destroyed; but, like another phoenix, it has again risen from its ashes in a greater degree of splendour. A period of nearly seven hundred years has now elapsed since the last of these occurrences; and the present fabric has but now narrowly escaped sharing the fate of its predecessors.

The damage which the Minster has sustained is not, perhaps, of so great a magnitude as, from the first appearance of the fire, might have been anticipated. The destruction is principally confined to the choir, the roof of which is entirely consumed. The beautiful and elaborately carved screen,1 which divides the choir from the nave, and forms a support for the organ-loft, has escaped in a most wonderful manner, a few of the more projecting ornaments being merely detached. The organ, an instrument scarcely equalled in tone by any other in Europe, is totally destroyed. The oaken stalls,2 together with their richly carved canopies, have likewise perished. The altar table, which stood at the eastern end of the choir, on a raised pavement, ascended by a flight of fifteen steps, is likewise consumed, and the communion plate melted. The beautiful stone screen, which separated the Lady's Chapel from the altar, has not suffered so materially as was at first imagined. This elegant specimen of ancient sculpture is divided into eight pointed arches, and elaborately ornamented with tracery work: the lights were filled with plate glass, through which a fine view of the great eastern window was obtained; some pieces of which still remain uninjured.

Such are the principal parts of the cathedral which have suffered. The books, cushions, and other movable effects, from the northern side of the choir, were fortunately rescued, together with the brazen eagle, from which the prayers were read. The wills, and other valuable documents, were also preserved.

The choir, the destruction of which we have just related, was built by John de Thoresby, a prelate, raised to the archiepiscopal chair in 1532. On this building he expended the then enormous sum of one thousand eight hundred and ten pounds out of his own private purse. The first stone was laid on the 29th of July, 1361; but the founder died before its completion, as is evident from the arms of several of his successors in various parts of the building, particularly those of Scrope and Bowet, the latter of whom was not created archbishop until the year 1405. It was constructed in a more florid style of architecture than the rest of the fabric. The roof, higher by some feet than that of the nave, was more richly ornamented, an elegant kind of festoon work descending from the capitals of the pillars, which separated the middle from the side aisles; from these columns sprung the vaulted roof, the ribs of which crossed each other in angular compartments. The magnificent window, the admiration of all beholders, occupies nearly the whole space of the eastern end of the choir; it is divided by two large mullions into three principal divisions, which are again subdivided into three lights; the upper part from the springing of the arches are also separated into various compartments. It contains nearly two hundred subjects, principally scriptural. The painting of this window was executed about the year 1405, at the expense of the dean and chapter, by John Thornton, a glazier, of Coventry, who, by his contract, was engaged to finish it within three years, and to receive four shillings per week for his work; he was also to have one hundred shillings besides; and also ten pounds more if he did his work well.3 On the exterior of the choir, immediately over the window, is the effigy of John de Thoresby, mitred and robed, and sitting in his archiepiscopal chair, his right hand pointing to the window, and in his left holding the model of a church. At the base of the window are the heads of Christ and the Apostles, with that of some sovereign, supposed to be Edward III.

We will now bring this article to a [pg 100] close, by quoting the words of Æneas Sylvius, afterwards Pope Pius II., in praise of York Cathedral. He says, "It is famous all over the world for its magnificence and workmanship, but especially for a fine lightsome chapel, with shining walls, and small, thin-waisted pillars, quite round."4

On the day of their creation, the trees boasted one to another, of their excellence. "Me, the Lord planted!" said the lofty cedar;—"strength, fragrance, and longevity, he bestowed on me."

"Jehovah fashioned me to be a blessing," said the shadowy palm; "utility and beauty he united in my form." The apple-tree, said, "Like a bridegroom among youths, I glow in my beauty amidst the trees of the grove!" The myrtle, said, "Like the rose among briars, so am I amidst the other shrubs." Thus all boasted;—the olive and the fig-tree—and even the fir.

The vine, alone, drooped silent to the ground! "To me," thought he, "every thing seems to have been refused;—I have neither stem—nor branches—nor flowers,—but such as I am, I will hope and wait." The vine bent down its shoots, and wept!

Not long had the vine to wait; for, behold, the divinity of earth, man, drew nigh; he saw the feeble, helpless, plant trailing its honours along the soil:—in pity, he lifted up the recumbent shoots, and twined the feeble plant around his own bower.

Now the winds played with its leaves and tendrils; and the warmth of the sun began to empurple its hard green grapes, and to prepare within them a sweet and delicious juice.

Decked with its rich clusters, the vine leaned towards its master, who tasted its refreshing fruit and juicy beverage; and he named the vine, his friend and favourite.

Despair not, ye forsaken; bear—be patient,—and strive.

From the insignificant reed flows the sweetest of juices;—from the bending vine springs the most delightful drink of the earth.

THE BATTLE OF NAVARINO.—BY AN OFFICER ENGAGED.

We had been cruizing off the coast of the Morea, for the protection of trading vessels, and to watch the motions of the numerous Greek pirates infesting the narrow seas and adjacent islands. For fourteen months we had been thus actively employed, when the arrival of the Albion and Genoa, from Lisbon, hinted to us, that some coercive measures were about to be used against the Turks, to cause them to discontinue the exterminating war they carried on against the Greeks, and to evacuate the country pursuant to the terms of the treaty of July, 1827. The prospect of a collision with the Turkish fleet appeared to be very agreeable to the ship's crew, as they had got a little tired of their long confinement on board, and anxiously looked for a speedy return to Malta to get ashore, which they had not been able to do for upwards of a year. We again proceeded on our protecting duty, and parted company with the admiral in the Asia. In about six weeks we returned, and found that many other British vessels had joined the Asia, whilst the squadrons of France and Russia added to the number of the fleet, which altogether presented an imposing attitude.

The Turkish and Egyptian fleets had arrived from the unsuccessful attempt in the Gulf of Patras some time before, and lay off the Bay of Navarino, before they finally entered and took up a position within the harbour. While the Ottoman fleet lay off the bay, the Turkish troops were said to have committed many unjustifiable outrages on the defenceless inhabitants of the country adjacent to Navarino; information of these oppressive acts was conveyed to the British admiral, and, it is believed, formed the grounds of a strong remonstrance on his part, addressed to the Turkish commanders, which hastened the collision between the two armaments. These facts were generally known throughout the fleet, and a "row" was eagerly expected.

About the beginning of October we had returned from our cruize; the men, ever since we had been in commission, had been daily exercised at the guns, and, by firing at marks, they had much improved in their practice.

Before entering the bay, the Ottoman fleet lay at the distance of ten or twelve miles from the Allies. They appeared numerous, with many small craft. Most [pg 101] of them bore the crimson flag flying at their peak, and on coming closer, a crescent and sword were visible on the flags. Their ships looked well, and in tolerable order: the Egyptians were evidently superior to the Turks.

Little communication took place between the Allied and Turkish fleets. The Dartmouth had gone into the bay twice, bearing the terms proposed by the allied commanders to Ibrahim Pacha. No satisfactory answer had been returned by the Ottoman admiral, whose conduct appeared evasive and trifling, implying a contempt for our prowess, and daring us to do our worst.

The Dartmouth having proceeded for the last time into the bay, with the final requisitions, and having brought back no satisfactory reply, on Saturday, the 20th of October, 1827, about noon, Admiral Codrington, favoured by a gentle sea-breeze, bore up under all sail for the mouth of the Bay of Navarino. A buzz ran instantly through the ship at the welcome intelligence of the admiral's bearing up; and I could easily perceive the hilarity and exultation of the seamen, and their impatience for the contest.

Our ship's crew was chiefly composed of young men, who had never seen a shot fired; yet, to judge from their manner, one would have thought them familiar with the business of fighting. The decks were then cleared for action, and the ship was quite ready, as we neared the mouth of the bay.

The Asia led the fleet, and was the first to enter the bay, followed by the ships in two columns. This was about one o'clock, or rather later. Abreast of Sir Edward Codrington was the French admiral, distinguished by the large white flag at the mizen. Then came the Genoa and Albion, followed by the Dartmouth, Talbot, and brigs, along with the French and Russian squadrons, in more distant succession. Every sail was set, so that the vast crowd of canvass, that looked more bleached and glittering in the rays of the sun, and contrasted with the deep blue unclouded sky, presented a magnificent and spirit-stirring spectacle. The breeze was just powerful enough to carry the allied fleet forward at a gentle rate, and as the wind freshened a little at times, it had the effect of causing the ships to heel to one side in a graceful, undulating manner,—the various flags and pendants of the united nations puffing out occasionally from the mast-heads. The sea was smooth, the weather rather warm, and the air quite clear. As we neared the entrance of the bay, the land presented all around a rugged, steep appearance towards the sea. In the distance, the mountains were visible, of a light blue, with whitish clouds apparently resting on their summits. The town and castle of Navarino presented a bright, picturesque look, and some spots of cultivation were to be seen. In the interior there rose in the air what looked like the smoke of some conflagration, and such we all believed was the case, as the Turkish soldiery had been employed in ravaging the country, and carrying away the inhabitants. An encampment of tents lay near, close to the castle, and large bodies of soldiers were easily discernible crowding on the batteries as we approached. We were about five hundred yards distant from the castle. The breadth of the entrance was about a mile.

When the Asia had arrived abreast of this castle, a boat rowed from the shore, and came alongside of the Asia with a request from Ibraham Pacha, that the allied fleets would not enter the bay; and just about that time, an unshotted gun was fired from the castle, which we interpreted as a signal for the Ottoman fleet to prepare for action. Close to the mouth of the bay, the cluster of vessels was considerable, all bearing up under a press of sail, and in perfect order. Our ship was close on the Asia's quarter. No opposition was made to our progress by the batteries of Navarino, which was a matter of surprise to all, as the men were ready at their quarters in momentary expectation of being attacked. To the spectators on the battlements our fleet must have presented a beautiful, though a formidable, appearance.

As soon as we had cleared the mouth of the bay, the Turko-Egyptian fleet was seen ranged round from right to left, in the form of an extensive crescent, in two lines, each ship with springs on her cables. Thus the combined fleets were in the centre of the lion's den, and the lists might be said to have been closed. The Asia, on passing the mouth of Navarino, sailed onwards to where the Turkish and Egyptian line-of-battle ships lay at anchor about three-quarters of a mile farther up the bay, and anchored close abreast one of their largest ships, bearing the flag of the Capitan Bey. The Genoa took her station near the Asia, whilst the Albion followed; but the Turks being so closely wedged together, she could not find space to pass between them to her appointed berth. The ship of the Egyptian Admiral lay as close to the Asia as that of the Capitan Bey: a large double-banked frigate was also near: all these three ships being moored in front of the crescent close upon the Asia and the [pg 102] Genoa. The wind by this time had almost died away, consequently the Albion had to anchor close alongside the double-banked frigate. This failing of the wind retarded considerably the progress of the ships, which had not yet entered the bay, particularly the Russian ships, and several of ours, which came later into action, and had to encounter the firing of the artillery of the castle.

The Egyptian fleet lay to the south-east; and, as it was well known that several French officers were serving on board, the French Admiral was appointed to place his squadron abreast of them. It appears, however, that, with one exception, all these Frenchmen quitted the Egyptian fleet, and went on board an Austrian transport which lay off the coast.

The post assigned to the Cambrian, Talbot, and Glasgow, along with the French frigate Armide, was alongside of the Turkish frigates at the left of the crescent on entering into the bay; whilst the Dartmouth, Musquito, the Rose, and Philomel, were ordered to keep a sharp look-out on the several fireships lurking suspiciously at the extremities of the crescent, and apparently ripe for mischief.

It was strictly enjoined in the orders, that no gun was to be fired, without a signal to that effect made by the Admiral, unless it should be in return for shots fired at us by the Turkish fleet. Each ship was to anchor with springs on her cables, if time allowed; and the orders concluded with the memorable words of Nelson,—"No captain can do very wrong who places his ship alongside of any enemy."

It was about two o'clock when we arrived at our station on the left of the bay, and anchored. The men were immediately sent aloft to furl the sails, which operation lasted a few minutes. Whilst so employed, the Dartmouth, distant about half a mile from our ship, had sent a boat, commanded by Lieut. Fitzroy, to request the fireship to remove from her station; a fire of musketry ensued from the fireship into the boat, killing the officer and several men. This brought on a return of small-arms from the Dartmouth and Syrene. Capt. Davis, of the Rose, having witnessed the firing of the Turkish vessel, went in one of his boats to assist that of the Dartmouth; and the crew of these two boats were in the act of climbing up the sides of the fireship, when she instantly exploded with a tremendous concussion, blowing the men into the water, and killing and disabling several in the boats close alongside. Just about this time, and before the men had descended from the yards, an Egyptian double-banked frigate poured a broadside into our ship. The captain gave instant orders to fire away; and the broadside was returned with terrible effect, every shot striking the hull of the Egyptian frigate. The men were now hastily descending the shrouds, while the captain sung out, "Now, my lads! down to the main-deck, and fire away as fast as you can." The seamen cheered loudly as they fired the first broadside, and continued to do so at intervals during the action. The battle had actually commenced to windward before the Asia and the Ottoman admiral had exchanged a single shot; and the action in that part of the bay was brought on in nearly a similar manner as in ours, by the Turks firing into the boat dispatched by Sir E. Codrington to explain the mediatorial views of the Allies. The Greek pilot had been killed; and ere the Asia's boat had reached the ship, the firing was unremitting between the Asia, Genoa, and Albion, and the Turkish ships. About half-past two o'clock, the battle had become general throughout the whole lines, and the cannonade was one uninterrupted crash, louder than any thunder. Previous to the Egyptian frigate firing into us, the men, not engaged in furling the sails, had stripped themselves to their duck-frocks, and were binding their black-silk neckcloths round their heads and waists, and some upon their left knees.

The Egyptian frigate, which had fired into our ship was distant about half a cable's length. Near her was another of the same large class, together with a Turkish frigate and a corvette. These four ships poured their broadsides into us without intermission for nearly a quarter of an hour; but after a few rounds their firing became irregular and hasty, and many of their shots injured our rigging. At the first broadside we received, two men near me were instantly struck dead on the deck. There was no appearance of any wounds upon them, but they never stirred a limb; and their bodies, after lying a little beside the gun at which they had been working, were dragged amid-ships. Several of the men were now severely wounded.

We were near enough to distinguish the Turkish and Egyptian sailors in the enemy's ships. They seemed to be a motley group. Most of them wore turbans of white, with a red cap below, small brown jackets, and very wide trousers; their legs were bare. They were active, brawny fellows, of a dark-brown complexion, and they crowded the Turkish ships, which accounts for the very great slaughter we occasioned among them. Many dead bodies were [pg 103] tumbled through their port-holes into the sea.

Capt. Hugon, commanding the French frigate L'Armide, about three o'clock, seeing the unequal, but unflinching combat we were maintaining, wormed his ship coolly and deliberately through the Turkish inner line, in such a gallant, masterly style, as never for one moment to obstruct the fire of our ship upon our opponents. He then anchored on our starboard-quarter, and fired a broadside into one of the Turkish frigates, thus relieving us of one of our foes, which, in about ten minutes, struck to the gallant Frenchman; who, on taking possession, in the most handsome manner, hoisted our flag along with his own, to show he had but completed the work we had begun. The skill, gallantry, and courtesy of the French captain, were the subject of much talk amongst us, and we were loud in his praise. We had still two of the frigates and the corvette to contend with, whilst the Armide was engaged, when a Russian line-of-battle-ship came up, and attracted the attention of another Egyptian frigate, and thus drew off her fire from us. Our men had now a breathing time, and they poured broadside upon broadside into the Egyptian frigate, which had been our first assailant. The rapidity and intensity of our concentrated fire soon told upon the vessel. Her guns were irregularly served, and many shots struck our rigging. Our round-shot, which were pointed to sink her, passed through her sides, and frequently tore up her decks in rebounding. In a short time she was compelled to haul down her colours, and ceased firing. We learned afterwards, that her decks were covered with nearly one hundred and fifty dead and wounded men, and the deck itself ripped up from the effects of our balls. In the interim, the corvette, which had annoyed us exceedingly during the action, came in for her share of our notice, and we managed to repay her in some style for the favours she had bestowed on us in the heat of the business. Orders were then issued for the men to cease firing for a few minutes, until the Rose had passed between our ship and the corvette, and had stationed herself in such a position as to annoy the latter in conjunction with us. Our firing was then renewed with redoubled fury, The men, during the pause, had leisure to quench their thirst from the tank which stood on the deck, and they appeared greatly refreshed—I may say, almost exhilarated, and to their work they merrily went again.

The double-banked Egyptian frigate, which had struck her colours to us, to our astonishment began, after having been silenced for some time, to open a smart fire on our ships, though she had no colours flying. The men were exceedingly exasperated at such treacherous conduct, and they poured into her two severe broadsides, which effectually silenced her, and at the moment we saw that a blue ensign was run up her mast, on which we ceased cannonading her, and she never fired another gun during the remainder of the action. It was a Greek pilot, pressed on board the Egyptian, who ran up the English ensign, to prevent our ship from firing again. He declared that our shot came into the frigate as thick and rapidly as a hail-storm, and so terrified the crew, that they all ran below. From the combined effects of our firing, and that of the Russian ship, the other Egyptian frigate hauled down her colours. The corvette, which was roughly handled by the Rose, was driven on shore, and there destroyed.

Before this, however, a Turkish fireship approached us, having seemingly no one on board. We fired into her, and in a few minutes she loudly exploded astern, without doing us any damage. The concussion was tremendous, shaking the ship through every beam. Another fireship came close to the Philomel which soon sunk her, and in the very act of going down she exploded.

A large ship near the Asia was now seen to be on fire; the blaze flamed up as high as the topmast, and soon became one vast sheet of fire; in that state she continued for a short time. The crew could be easily discerned gliding about across the light; and, after a horrible suspense, she blew up, with an explosion far louder and more stunning than the ships which had done so in our vicinity. The smoke and lurid flame ascended to a vast height in the air; beams, masts, and pieces of the hull, along with human figures in various distorted postures, were clearly distinguishable in the air.

It was now almost dark, and the action had ceased to be general throughout the lines; but blaze rose upon blaze, and explosion thundered upon explosion, in various parts of the bay. A pretty sharp cannonading had been kept up between the guns of the castle and the ships entering the bay, and that firing still continued. The smaller Turkish vessels, forming the second line, were now nearly silenced, and several exhibited signs of being on fire, from the thick light-coloured smoke that rose from their decks.

The action had nearly terminated by six o'clock, after a duration of four hours. Daylight had disappeared unperceived, owing to the dense smoke of the [pg 104] cannonading, which, from the cessation of the firing, now began to clear away, and showed us a clouded sky. The bay was illuminated in various quarters by the numerous burning ships, which rendered the sight one of the most sublime and magnificent that could be imagined.

Seynte Valentine. Of custome, yeere by yeere,

Men have an usaunce, in this regioun,

To loke and serche Cupide's kalendere,

And chose theyr choyse, by grete affeccioun;

Such as ben move with Cupide's mocioun,

Taking theyr choyse as theyr sorte doth falle;

But I love oon whyche excellith alle.

In some villages in Kent there is a singular custom observed on St. Valentine's day. The young maidens, from five or six to eighteen years of age, assemble in a crowd, and burn an uncouth effigy, which they denominate a "holly boy," and which they obtain from the boys; while in another part of the village the boys burn an equally ridiculous effigy, which they call an "ivy girl," and which they steal from the girls. The oldest inhabitants can give you no reason or account of this curious practice, though it is always a sport at this season.

Numerous are the sports and superstitions concerning the day in different parts of England. In some parts of Dorsetshire the young folks purchase wax candles, and let them remain lighted all night in the bedroom. I learned this from some old Dorsetshire friends of mine, who, however, could throw no further light upon the subject. In the same county, I was also informed it was in many places customary for the maids to hang up in the kitchen a bunch of such flowers as were then in season, neatly suspended by a true lover's knot of blue riband. These innocent doings are prevalent in other parts of England, and elsewhere.

Misson, a learned traveller, relates an amusing practice which was kept up in his time:—"On the eve of St. Valentine's day, the young folks in England and Scotland, by a very ancient custom, celebrated a little festival. An equal number of maids and bachelors assemble together; all write their true or some feigned name separately upon as many billets, which they rolled up, and drew by way of lots, the maids taking the men's billets, and the men the maids'; so that each of the young men lights upon a girl that he calls his Valentine, and each of the girls upon a young man which she calls her's. By this means each has two Valentines; but the man sticks faster to the Valentine that falls to him, than to the Valentine to whom he has fallen. Fortune having thus divided the company into so many couples, the Valentines give balls and treats to their fair mistresses, wear their billets several days upon their bosoms or sleeves, and this little sport often ends in love."

In Poor Robin's Almanack, 1676, the drawing of Valentines is thus alluded to:

"Now Andrew, Antho-

Ny, and William,

For Valentines draw

Prue, Kate, Jilian."

Gay makes mention of a method of choosing Valentines in his time, viz. that the lad's Valentine was the first lass he spied in the morning, who was not an inmate of the house; and the lass's Valentine was the first young man she met.

Also, it is a belief among certain playful damsels, that if they pin four bay leaves to the corners of the pillow, and the fifth in the middle, they are certain of dreaming of their lover.

Shakspeare bears witness to the custom of looking out of window for a Valentine, or desiring to be one, by making Ophelia sing:—

Good morrow! 'tis St. Valentine's day,

All in the morning betime,

And I a maid at your window.

To be your Valentine!

In London this day is ushered in by the thundering knock of the postman at the different doors, through whose hands some thousands of Valentines pass for many a fair maiden in the course of the day. Valentines are, however, getting very ridiculous, if we may go by the numerous doggrels that appear in the print-shops on this day. As an instance, I transmit the reader a copy of some lines appended to a Valentine sent me last year. Under the figure of a shoemaker, with a head thrice the size of his body, and his legs forming an oval, were the following rhymes:—

Do you think to be my Valentine?

Oh, no! you snob, you shan't be mine:

So big your ugly head has grown,

No wig will fit to seem your own

Go, find your equal if you can,

For I will ne'er have such a man;

Your fine bow legs and turned-in feet,

Make you a citizen complete."

The fair writer had here evidently ventured upon a pun; how far it has succeeded I will leave others to say. The lovely creature was, however, entirely ignorant of my calling; and whatever impression such a description would leave on the reader's mind, it made none on mine, though in the second verse I was certainly much pleased with the fair punster. I wish you saw the engraving!

The first page or frontispiece embellisment of the present Number of the MIRROR illustrates one of the most recent triumphs of art; and the above vignette is a fragment of the monastic splendour of the twelfth century. Truly this is the bathos of art. The plaster and paint of the Colosseum are scarcely dry, and half the work is in embryo; whilst Kirkstall is crumbling to dust, and reading us "sermons in stones:" we may well say,

"Look here, upon this picture, and on this."

Kirkstall Abbey is situated a short distance from Leeds, in the West Riding of Yorkshire. Its situation is one of the most picturesque that the children of romance can wish for, being in a beautiful vale, watered by the river Aire. It was of the Cistercian order, founded by Henry de Lacy in 1157, and valued at the dissolution at 329l. 2s. 11d. Its rents are now worth 10,253l. 6s. 8d. The gateway has been walled up, and converted into a farm-house. The abbot's palace was on the south; the roof of the aisle is entirely gone; places for six altars, three on each side the high altar, appear by distinct chapels, but to what saints dedicated is not easy, at this time, to discover. The length of the church, from east to west, was 224 feet; the transept, from north to south, 118 feet. The tower, built in the time of Henry VIII., remained entire till January 27, 1779, when three sides of it were blown down, and only the fourth remains. Part of an arched chamber, leading to the cemetery, and part of the dormitory, still remain. On the ceiling of a room in the gatehouse is inscribed,

Mille et Quingentos postquam compleverit Orbis

Tuq: et ter demos per sua signi Deus

Prima sauluteferi post cunabula Christi,

Cui datur omnium Honor, Gloria, Laus, et Amor.

The principal window is particularly admired as a rich specimen of Gothic beauty, and a tourist, in 1818, says, "bids defiance to time and tempest;" but in our engraving, which is of very recent date, the details of the window will be sought for in vain. "Shrubs and trees," observes the same writer, "have found a footing in the crevices, and branches from the walls shook in undulating monotony, and with a gloomy and spiritual murmur, that spoke to the ear of time and events gone by, and lost in oblivion and dilapidation. At the end, immediately beneath the colossal window, grows an alder of considerable luxuriance, which, added to the situation of every other object, brought Mr. Southey's pathetic ballad of 'Mary the Maid of the Inn,' so forcibly before my imagination,5 that I involuntarily turned my eye to search for the grave, where the murderers concealed their victim." He likewise tells us of "the former garden of the [pg 106] monastery, still cultivated, and exhibiting a fruitful appearance;" cells and cavities covered with underwood; and his ascent to a gallery by a winding turret stair, whence, says he, "the monks of Kirkstall feasted their eyes with all that was charming in nature. It is said," adds he, "that a subterraneous passage existed from hence to Eshelt Hall, a distance of some miles, and that the entrance is yet traced."

The Mocking-bird seems to be the prince of all song birds, being altogether unrivalled in the extent and variety of his vocal powers; and, besides the fulness and melody of his original notes, he has the faculty of imitating the notes of all other birds, from the humming-bird to the eagle. Pennant tells us that he heard a caged one, in England, imitate the mewing of a cat and the creaking of a sign in high winds. The Hon. Daines Barrington says, his pipe comes nearest to the nightingale, of any bird he ever heard. The description, however, given by Wilson, in his own inimitable manner, as far excels Pennant and Barrington as the bird excels his fellow-songsters. Wilson tells that the ease, elegance and rapidity of his movements, the animation of his eye, and the intelligence he displays in listening and laying up lessons, mark the peculiarity of his genius. His voice is full, strong, and musical, and capable of almost every modulation, from the clear mellow tones of the wood thrush to the savage scream of the bald eagle. In measure and accents he faithfully follows his originals, while in force and sweetness of expression he greatly improves upon them. In his native woods, upon a dewy morning, his song rises above every competitor, for the others seem merely as inferior accompaniments. His own notes are bold and full, and varied seemingly beyond all limits. They consist of short expressions of two, three, or at most five or six, syllables, generally expressed with great emphasis and rapidity, and continued with undiminished ardour, for half an hour or an hour at a time. While singing, he expands his wings and his tail, glistening with white, keeping time to his own music, and the buoyant gaiety of his action is no less fascinating than his song. He sweeps round with enthusiastic ecstasy, he mounts and descends as his song swells or dies away; he bounds aloft, as Bartram says, with the celerity of an arrow, as if to recover or recall his very soul, expired in the last elevated strain. A bystander might suppose that the whole feathered tribes had assembled together on a trial of skill; each striving to produce his utmost effect, so perfect are his imitations. He often deceives the sportsman, and even birds themselves are sometimes imposed upon by this admirable mimic. In confinement he loses little of the power or energy of his song. He whistles for the dog; Cæsar starts up, wags his tail, and runs to meet his master. He cries like a hurt chicken, and the hen hurries about, with feathers on end, to protect her injured brood. He repeats the tune taught him, though it be of considerable length, with great accuracy. He runs over the notes of the canary, and of the red bird, with such superior execution and effect, that the mortified songsters confess his triumph by their silence. His fondness for variety, some suppose to injure his song. His imitations of the brown thrush is often interrupted by the crowing of cocks; and his exquisite warblings after the blue bird, are mingled with the screaming of swallows, or the cackling of hens. During moonlight, both in the wild and tame state, he sings the whole night long. The hunters, in their night excursions, know that the moon is rising the instant they begin to hear his delightful solo. After Shakspeare, Barrington attributes in part the exquisiteness of the nightingale's song to the silence of the night; but if so, what are we to think of the bird which in the open glare of day, overpowers and often silences all competition? His natural notes partake of a character similar to those of the brown thrush, but they are more sweet, more expressive, more varied, and uttered with greater rapidity.

The Yellow breasted Chat naturally follows his superior in the art of mimicry. When his haunt is approached, he scolds the passenger in a great variety of odd and uncouth monosyllables, difficult to describe, but easily imitated so as to deceive the bird himself, and draw him after you to a good distance. At first are heard short notes like the whistling of a duck's wings, beginning loud and rapid, and becoming lower and slower, till they end in detached notes. There succeeds something like the barking of young puppies, followed by a variety of guttural sounds, and ending like the mewing of a cat, but much hoarser.

The song of the Baltimore Oriole is little less remarkable than his fine appearance, and the ingenuity with which he builds his nest. His notes consist of a clear mellow whistle, repeated at short intervals as he gleams among the branches. [pg 107] There is in it a certain wild plaintiveness and naïveté extremely interesting. It is not uttered with rapidity, but with the pleasing tranquillity of a careless ploughboy, whistling for amusement. Since the streets of some of the American towns have been planted with Lombardy poplars, the orioles are constant visiters, chanting their native "wood notes wild," amid the din of coaches, wheelbarrows, and sometimes within a few yards of a bawling oysterwoman.

The Virginian Nightingale, Red Bird, or Cardinal Grosbeak, has great clearness, variety, and melody in his notes, many of which resemble the higher notes of a fife, and are nearly as loud. He sings from March till September, and begins early in the dawn, and repeating a favourite stanza twenty or thirty times successively, and often for a whole morning together, till, like a good story too frequently repeated, it becomes quite tiresome. He is very sprightly, and full of vivacity; yet his notes are much inferior to those of the wood, or even of the brown thrush.

The whole song of the Black-throated Bunting consists of five, or rather two, notes; the first repeated twice and very slowly, the third thrice and rapidly, resembling chip, chip, che-che-che; of which ditty he is by no means parsimonious, but will continue it for hours successively. His manners are much like those of the European yellow-hammer, sitting, while he sings, on palings and low bushes.

The song of the Rice Bird is highly musical. Mounting and hovering on the wing, at a small height above the ground, he chants out a jingling melody of varied notes, as if half a dozen birds were singing together. Some idea may be formed of it, by striking the high keys of a piano-forte singly and quickly, making as many contrasts as possible, of high and low notes. Many of the tones are delightful, but the ear can with difficulty separate them. The general effect of the whole is good; and when ten or twelve are singing on the same tree, the concert is singularly pleasing.

The Red-eyed Flycatcher has a loud, lively, and energetic song, which is continued sometimes for an hour without intermission. The notes are, in short emphatic bars of two, three, or four syllables. On listening to this bird, in his full ardour of song, it requires but little imagination to fancy you hear the words "Tom Kelly! whip! Tom Kelly!'" very distinctly; and hence Tom Kelly is the name given to the bird in the West Indies.

The Crested Titmouse possesses a remarkable variety in the tones of its voice, at one time not louder than the squeaking of a mouse, and in a moment after whistling aloud and clearly, as if calling a dog, and continuing this dog-call through the woods for half an hour at a time.

The Red-breasted Blue Bird has a soft, agreeable, and often repeated warble, uttered with opening and quivering wings. In his courtship he uses the tenderest expressions, and caresses his mate by sitting close by her, and singing his most endearing warblings. If a rival appears, he attacks him with fury, and having driven him away, returns to pour out a song of triumph. In autumn his song changes to a simple plaintive note, which is heard in open weather all winter, though in severe weather the bird is never to be seen.—Mag. Nat. Hist.

In the 312th Number of the Mirror, several solutions are given of the name of a well-known and high-priced fish, the John Dory, or Jaune Dorée. Sir Joseph Banks's observation, that it should be spelled and acknowledged "adorée," because it is the most valuable (or worshipful) of fish, as requiring no sauce, is equally absurd and unwarranted; for so far from its being incapable of improvement from such adjuncts, its relish is materially augmented by any one of the three most usual side tureens. The dory attains its fullest growth in the Adriatic, and is a favourite dish in Venice, where, as in all the Italian ports of the Mediterranean, it is called Janitore, or the gate-keeper, by which title St. Peter is most commonly designated among the Catholics, as being the reputed keeper of the keys of heaven. In this respect, the name tallies with the superstitious legend of this being the fish out of whose mouth the apostle took the tribute money. The breast of the animal is very much flattened, as if it had been compressed; but, unfortunately for the credit of the monks, this feature is exhibited in equally strong lineaments by, at least, twenty other varieties of the finny tribe.

Our sailors naturally substituted the appellation of John Dory for the Italian Janitore, and a very high price is sometimes given for this fish when in prime condition, as I can testify from experience; having two years since seen one at Ramsgate which was sold early in the day for eighteen shillings.

"Anecdotes correspond in literature with the sauces, the savoury dishes, and the sweetmeats of a splendid banquet;" and as our weekly sheet is a sort of literary fricassee, the following may not be unacceptable to the reader. They are penciled from a work quaintly enough entitled "The Living and the Dead, by a Country Curate;" and equally strange, the cognomen of the author is not a ruse—he being a curate at Liverpool, the son of Dr. Adam Neale, and a nephew of the late Mr. Archibald Constable, the eminent publisher, of Edinburgh. The information which this volume contains, may therefore be received with greater confidence than is usually attached to flying anecdotes; since Mr. Constable's frequent and familiar intercourse with the first literary characters of his time must have given him peculiar facilities of observation of their personal habits. The present volume of "The Living and the Dead" is what the publisher terms the Second Series; for, like Buck, the turncoat actor, booksellers always think that one good turn deserves another. Our first extracts relate to Chantrey's monument in Lichfield Cathedral, and another of rival celebrity.

At the retired church of Ashbourne is "a remarkable monument", by Banks, to the memory of a very lovely and intelligent little girl, a baronet's only child. It bears an inscription which, to use the mildest term, as it contains not the slightest reference to Christian hopes, should have been refused admittance within a Christian church. To the sentiments it breathes, Paine himself, had he been alive, could have raised no objection. * * * * The figure, which is recumbent, is that of a little girl; the attitude exquisitely natural and graceful. It recalls most forcibly to the recollection Chantrey's far-famed monument in Lichfield Cathedral; for the resemblance, both in design and execution, between these beautiful specimens of art is close and striking.

Previous to his executing that most magnificent yet most touching piece of sculpture, which alone would have sufficed to immortalize his name, Chantrey was, at his own request, locked up alone in the church for two hours. This fact may be apocryphal; but the following I do affirm most confidently. When I hinted to the venerable matron who shows the monument, and who, being a retainer of the Boothby family, feels their honour identified with her own, that Chantrey's was by far the finer effort of the two, and that I wished I had that yet to see; and my companion added, that though the design of the Boothby monument was good, the execution was coarse and clumsy in the extreme, compared with the elaborate finish of the Robinson's. "Humph," said the old lady, with a most vinegar expression of countenance, with a degree of angry hauteur, an air of insulted dignity that Yates would have travelled fifty miles to witness; "the like of that's what I now hear every day. Hang that fellow Chantee, or Cantee, or what you call him; I wish he had never been born!" The Ashbourne people are naturally proud of the monument. With them it is a kind of idol, to which every stranger is required to do homage. Among others, when Prince Leopold passed through Ashbourne, and inquiries were made by some of his royal highness's suite as to the "lions" of the neighbourhood—"We have one of our own, Sir," was the ready reply; "a noble piece of sculpture in the church." To the church the royal mourner was on the very point of repairing, when Sir Robert Gardiner suddenly inquired the description to which the sculpture in question belonged. "It is a monument, Sir, no one passes through without seeing it; for its like is not to be met with in England—it is a monument to an only child, whose mother died—" "Not now," said the prince faintly; "not now. I too have lost—" and he turned away from the carriage in tears.

It may be observed, too, by the way, that to Ashbourne the late Mr. Canning was remarkably partial. Near it lived a female relative to whom he was warmly attached, and under whose roof many of his happiest hours were spent. It is stated, that a little poem, entitled, "A Spring Morning in Dovedale," one of the earliest efforts of his muse, is still in existence; and I have good reasons for knowing, that but a very few weeks previous to his death, he stated, in conversation, what delight he should feel in "going into that neighbourhood, and revisiting haunts which to him had been scenes of almost unalloyed enjoyment." I could scarcely believe, so exquisitely tranquil is the scene, the very murmur of the stream which flows around seems to soften itself in unison with the stillness of the landscape—that Ashbourne had ever been other than the abode of rural [pg 109] peace and comfort; and yet I was assured that during the war there was scarcely any limit to the bustle and gaiety which pervaded it.

At Mayfield, near Ashbourne, is a cottage where Moore, it is stated, composed Lalla Rookh. "For some years this distinguished poet lived at the neighbouring village of Mayfield; and there was no end to the pleasantries and anecdotes that were floating about its coteries respecting him; no limit to the recollections which existed of the peculiarities of the poet, of the wit and drollery of the man. Go where you would, his literary relics were pointed out to you. One family possessed pens; and oh! Mr. Bramah! such pens! they would have borne a comparison with Miss Mitford's; and those who are acquainted with that lady's literary implements and accessaries will admit this is no common-place praise—pens that wrote "Paradise and the Peri" in Lalia Rookh! Another showed you a glove torn up into thin shreds in the most even and regular manner possible; each shred being in breadth about the eighth of an inch, and the work of the teeth! Pairs were demolished in this way during the progress of the Life of Sheridan. A third called your attention to a note written in a strain of the most playful banter, and announcing the next "tragi-comedy meeting." A fourth repeated a merry impromptu; and a fifth played a very pathetic air, composed and adapted for some beautiful lines of Mrs. Opie's. But to return to Mayfield. Our desire to go over the cottage which he had inhabited was irresistible. It is neat, but very small, and remarkable for nothing except combining a most sheltered situation with the most extensive prospect. Still one had pleasure in going over it, and peeping into the little book-room, ycleped the "Poet's Den," from which so much true poetry had issued to delight and amuse mankind. But our satisfaction was not without its portion of alloy. As we approached the cottage, a figure scarcely human appeared at one of the windows. Unaware that it was again inhabited, we hesitated about entering; when a livid, half-starved visage presented itself through the lattice, and a thin, shrill voice discordantly ejaculated,—"Come in, gentlemen, come in. Don't be afeard! I'm only a tailor at work on the premises." This villanous salutation damped sadly the illusion of the scene; and it was some time before we rallied sufficiently from this horrible desecration to descend to the poet's walk in the shrubbery, where, pacing up and down the live-long morning, he composed his Lalla Rookh. It is a little confined gravel-walk, in length about twenty paces; so narrow, that there is barely room on it for two persons to walk abreast: bounded on one side by a straggling row of stinted laurels, on the other by some old decayed wooden paling; at the end of it was a huge haystack. Here, without prospect, space, fields, flowers, or natural beauties of any description, was that most imaginative poem conceived, planned, and executed. It was at Mayfield, too, that those bitter stanzas were written on the death of Sheridan. There is a curious circumstance connected with them; they were sent to Perry, the well-known editor of the Morning Chronicle. Perry, though no stickler in a general way, was staggered at the venom of two stanzas, to which I need not more particularly allude, and wrote to inquire whether he might be permitted to omit them. The reply which he received was shortly this: "You may insert the lines in the Chronicle or not, as you please; I am perfectly indifferent about it; but if you do insert them, it must be verbatim." Mr. Moore's fame would not have suffered by their suppression; his heart would have been a gainer. Some of his happiest efforts are connected with the localities of Ashbourne. The beautiful lines beginning

"Those evening bells, those evening bells,"

were suggested, it is said, by hearing the Ashboume peal; and sweetly indeed do they sound at that distance, "both mournfully and slow;" while those exquisitely touching stanzas,

"Weep not for those whom the veil of the tomb

In life's happy morning hath hid from our eyes,"

were avowedly written on the sister of an Ashbourne gentleman, Mr. P—— B——. But to his drolleries. He avowed on all occasions an utter horror of ugly women. He was heard, one evening, to observe to a lady, whose person was pre-eminently plain, but who, nevertheless, had been anxiously doing her little endeavours to attract his attention, "I cannot endure an ugly woman. I'm sure I could never live with one. A man that marries an ugly woman cannot be happy." The lady observed, that "such an observation she could not permit to pass without remark. She knew many plain couples who lived most happily."—"Don't talk of it," said the wit; "don't talk of it. It cannot be."—"But I tell you," said the lady, who became all at once both piqued and positive, "it can be, and it is. I will name individuals so [pg 110] circumstanced. You have heard of Colonel and Mrs. ——. She speaks in a deep, gruff bass voice; he in a thin, shrill treble. She looks like a Jean Dorée; he like a dried alligator. They are called Bubble and Squeak by some of their neighbours; Venus and Adonis by others. But what of that? They are not handsome, to be sure; and there is neither mirror nor pier-glass to be found, search their house from one end of it to the other. But what of that? No unhandsome reflections can, in such a case, be cast by either party! I know them well; and a more harmonious couple I never met with. Now, Mr. Moore, in reply, what have you to say? I flatter myself I have overthrown your theory completely." "Not a whit. Colonel—has got into a scrape, and, like a soldier, puts the best face he can upon it." Those still exist who were witnesses to his exultation when one morning he entered Mrs——'s drawing-room, with an open letter in his hand, and, in his peculiarly joyous and animated manner, exclaimed, "Don't be surprised if I play all sorts of antics! I am like a child with a new rattle! Here is a letter from my friend Lord Byron, telling me he has dedicated to me his poem of the 'Corsair.' Ah, Mrs.——, it is nothing new for a poor poet to dedicate his poem to a great lord; but it is something passing strange for a great lord to dedicate his book to a poor poet." Those who know him most intimately feel no sort of hesitation in declaring, that he has again and again been heard to express regret at the earlier efforts of his muse; or reluctance in stating, at the same time, as a fact, that Mr. M., on two different occasions, endeavoured to repurchase the copyright of certain poems; but, in each instance, the sum demanded was so exorbitant, as of itself to put an end to the negotiation. The attempt, however, does him honour. And, affectionate father as he is well known to be, when he looks at his beautiful little daughter, and those fears, and hopes, and cares, and anxieties, come over him which almost choke a parent's utterance as he gazes on a promising and idolized child, he will own the censures passed on those poems to be just: nay more—every year will find him more and more sensible of the paramount importance of the union of female purity with female loveliness—more alive to the imperative duty, on a father's part, to guard the maiden bosom from the slightest taint of licentiousness. It is a fact not generally suspected, though his last work, "The Epicurean," affords strong internal evidence of the truth of the observation, that few are more thoroughly conversant with Scripture than himself. Many of Alethe's most beautiful remarks are simple paraphrases of the sacred volume. He has been heard to quote from it with the happiest effect—to say there was no book like it—no book, regarding it as a mere human composition, which could on any subject even "approach it in poetry, beauty, pathos, and sublimity." Long may these sentiments abide in him! And as no man, to use his own words, "ever had fiercer enemies or firmer friends"—as no man, to use those of others, was ever more bitter and sarcastic as a political enemy, more affectionate and devoted as a private friend, the more deeply his future writings are impregnated with the spirit of that volume, the more heartfelt, let him be well assured, will be his gratification in that hour when "we shall think of those we love, only to regret that we have not loved more dearly, when we shall remember our enemies only to forgive them."

The following Synopsis of English Sovereigns, and their contemporaries, will, it is hoped, be acceptable to the readers of history.

began his reign, 14th Oct. 1066, died 9th Sept. 1087.

Popes.

Alexander II., 1061.

Gregory VII., 1073.

Victor III., 1086.

Emperors of the East.

Constantine XII., 1059.

Romanus IV., 1068.

Michael VII., 1071.

Nicephorus I., 1078.

Alexis I., 1081.

Emperor of the West.

Henry IV., 1056.

France.

Philip I., 1060.

Scotland.

Malcolm III., 1059.

Donald VIII., 1068.

began his reign 9th Sept. 1087, died 2nd Aug. 1100.

Popes.

Victor III., 1086.

Urban II., 1088.

Pascal II., 1099.

Emperor of the East.

Alexis I., 1081.

Emperor of the West.

Henry IV., 1056.

France.

Philip I., 1060.

Scotland.

Donald VIII., 1068.

began his reign 2nd August 1100, ended 1st Dec. 1135.

Popes.

Pascal II., 1099.

Gelassus II., 1118.

Calistus II., 1119.

Honorius II., 1124.

Innocent II., 1130.

Celestin II., 1134.

Emperors of the East.

Alexis I., 1081.

John Cominus, 1118.

Emperors of the West.

Henry IV., 1056.

Henry V., 1106.

Lotharius II., 1125.

France.

Philip I., 1060.

Louis VI., 1108.

Scotland.

Donald VIII., 1068.

Edgar, 1108.

David, 1134.

began his reign 1st Dec. 1135, ended 25th Oct. 1154.

Popes.

Celestin II., 1134.

Lucius II., 1144.

Eugenius III. 1145.

Anastasius IV., 1153.

Adrian V., 1154.

Emperors of the East.

John Cominus, 1118.

Emanuel Cominus, 1143.

Emperors of the West.

Lotharius II. 1125.

Conrad III., 1138.

Frederic I., 1152.

France.

Louis VI., 1108.

Louis VII., 1137.

Scotland.

David, 1134.

began his reign 25th Oct. 1154, ended 6th July, 1189.

Popes.

Adrian IV., 1154.

Alexander II., 1154.

Lucius III., 1181.

Urban III., 1185.

Gregory VIII., 1187.

Clement III., 1188.

Emperors of the East.

Emanuel Cominus, 1143.

Alexis II., 1180.

Andronicus I., 1183.

Isaac II., 1185.

Emperor of the West.

Frederic I., 1152.

France.

Louis VII., 1137.

Philip II., 1180.

Scotland.

David, 1134.

Malcolm IV., 1163.

William, 1165.

began his reign 6th July, 1189, ended 6th April, 1199.

Popes.

Clement III., 1188.

Celestin III., 1191.

Innocent III., 1198.

Emperors of the East.

Isaac II., 1185.

Alexis III., 1195.

Emperors of the West.

Frederic I., 1152.

Henry VI., 1196.

Philip I., 1197.

France.

Philip II., 1180.

Scotland.

William., 1165.

began his reign 6th April, 1199, ended 19th Oct. 1216.

Popes.

Innocent III., 1198.

Honorius III., 1215.

Emperors of the East.

Alexis III., 1195.

Alexis IV., 1203.

Alexis V., 1204.

Theodoras I., 1204.

Emperors of the West.

Philip I., 1197.

Otho IV., 1208.

Frederic II., 1212.

French Emperors of Constantinople.

Baldwin I., 1204.

Henry I., 1206.

France.

Philip II., 1180.

Scotland.

William, 1165.

Alexander II., 1214.

began his reign 19th Oct. 1216, ended 16th Nov. 1272.

Popes.

Honorius III., 1215.

Gregory IX., 1227.

Celestin IV., 1241.

Innocent IV., 1243.

Alexander IV., 1254.

Urban IV., 1261.

Clement IV., 1265.

Gregory X., 1271.

Emperors of the East.

Theodore I., 1204.

John III., 1222.

Theodore II., 1225.

John IV., 1259.

Michael VIII., 1259.

Emperor of the West.

Frederic II., 1212.

French Emperors of Constantinople.

Henry I., 1206.

Peter II., 1217.

Robert de Cour., 1221.

Baldwin II., 1237.

France.

Philip II., 1180.

Louis VIII., 1223.

Louis IX., 1226.

Philip III., 1270.

Scotland.

Alexander II., 1214.

Alexander III., 1249.

began his reign 16th Nov. 1272, ended 7th July, 1307.

Popes.

Gregory X., 1270.

Innocent V., 1276.

Adrian V., 1276.

John XXI., 1276.

Nicholas III., 1277.

Martin IV., 1281.

Honorius IV., 1285.

Nicholas IV., 1288.

Celestin V., 1294.

Boniface VIII., 1294.

Benedict X., 1303.

Clement V., 1305.

Emperors of the East.

Michael VIII., 1259.

Andronicus II., 1283.

Emperors of the West.

Frederic II., 1212.

Rodolphus I., 1273.

Adolphus, 1291.

Albert I., 1298.

France.

Philip III., 1270.

Philip IV., 1285.

Scotland.

Alexander III., 1249.

John Baliol, 1293.

Robert Bruce, 1306.

A snapper up of unconsidered trifles.

SHAKSPEARE.

A soldier of Marshal Saxe's army being discovered in a theft, was condemned to be hanged. What he had stolen might be worth about 5s. The marshal meeting him as he was being led to execution, said to him, "What a miserable fool you were to risk your life for 5s.!"—"General," replied the soldier, "I have risked it every day for five-pence." This repartee saved his life.

It was customary, as the French general in command of the Italian army passed through Lyons to join his army, for that town to offer him a purse full of gold. Marshal Villars on being thus complimented by the head magistrate, the latter concluded his speech by observing, that Turenne, who was the last commander of the Italian army who had honoured the town with his presence, had taken the purse, but returned the money. "Ah!" replied Villars, pocketing both the purse and the gold, "I have always looked upon Turenne to be inimitable."

Capt. S———, of the ——— regiment, during the American war, was notorious for a propensity, not to story-telling, but to telling long stories, which he used to indulge in defiance of time and place, often to the great annoyance of his immediate companions; but he was so good-humoured withal, that they were loth to check him abruptly or harshly. An opportunity occurred of giving him a hint, which had the desired effect. He was a member of a courtmartial assembled for the trial of a private of the regiment. The man bore a very good character in general, the offence he had committed was slight, and the court was rather at a loss what punishment to award, for it was requisite to award some, as the man had been found guilty. While they were deliberating on this, Major ———, now General Sir ———, suddenly turning to the president, said, in his dry manner, "Suppose we sentence him to hear two of Captain S———'s long stories."

The crier sounds a flourish on that delightful sonorous instrument, the bagpipe, then loquitor, "Tak tent a' ye land louping hallions, the meickle deil tamn ye, tat are within the bounds. If any o' ye be foond fishing in ma Lort Preadalpine's gruns, he'll be first headit, and syne hangit, and syne droom't; an' if ta loon's bauld enough to come bock again, his horse and cart will be ta'en frae him; and if ta teils' sae grit wi' him tat he shows his ill faurd face ta three times, far waur things wull be dune till him. An noo tat ye a' ken ta wull o' ta lairt, I'll e'en gang hame and sup my brose."

L et me but hope

O lovely maid,

U ever will be mine,

I 'll bless my fate,

S upremely great,

A happy Valentine.

"Dyed stockings are always rotten," said a Nottingham warehouseman.—"Yes," replied a by-stander, "and you'll be rotten when you're dead."

What will some grave people say to this?—from a "Constant Reader." A little boy having swallowed a medal of Napoleon, ran in great tribulation to his mother, and told her "that he had swallowed Boneparty."

PURCHASERS of the MIRROR, who may wish to complete their sets are informed, that every volume is complete in itself, and may be purchased separately. The whole of the numbers are now in print, and can be procured by giving an order to any Bookseller or Newsvender.

Complete sets Vol I.. to XII. in boards, price £3. 5s. half bound, £4. 2s. 6d.

CHEAP and POPULAR WORKS published at the MIRROR OFFICE in the Strand, near Somerset House.

The ARABIAN NIGHTS' ENTERTAINMENTS, Embellished with nearly 150

Engravings. Price 6s. 6d. boards

The TALES of the GENII. Price 2s.

The MICROCOSM. By the Right Hon. G. CANNING. &c. Price 2s.

PLUTARCH'S LIVES, with Fifty Portraits, 2 vols. price 13s. boards.

COWPER'S POEMS, with 12 Engravings, price 3s 6d boards.

COOK'S VOYAGES, 2 vols. price 8s. boards.

The CABINET of CURIOSITIES: or, WONDERS of the WORLD DISPLAYED. Price

5s. boards.

BEAUTIES of SCOTT. 2 vols. price 7s. boards.

The ARCANA of SCIENCE for 1828. Price 4s. 6d.

*** Any of the above Works can be purchased in Parts.

GOLDSMITH'S ESSAYS. Price 8d.

DR. FRANKLIN'S ESSAYS. Price 1s. 2d.

BACON'S ESSAYS Price 8d.

SALMAGUNDI. Price 1s. 8d.

Footnote 1: (return)This elegant and curious piece of workmanship, the history of which is involved in uncertainty, bears the marks of an age subsequent to that of the choir, and was probably erected in the reign of Henry VI. It is in the most finished style of the florid Gothic, containing niches, canopies, pediments, and pinnacles, and decorated with the statues of all the sovereigns of England, from the Norman Conquest to Henry V. The statue of James I. stands in the niche which tradition assigns as that formerly occupied by the one of Henry VI.

Footnote 2: (return)These stalls or seats which were formed of oak, and of the most elaborate workmanship, occupied the side, and western end of the choir: they were surmounted by canopies, supported by slender pillars, rising from the arms, each being furnished with a movable misericordia.

Footnote 4: (return)We thank our intelligent antiquarian correspondent for this article, which, he will perceive appears somewhat, abridged, as we are unable to spare room for further details.

Footnote 5: (return)We ourselves remember the thrilling effect of our first reading this ballad; especially while clambering over the ruins of Brambletye House. Indeed, the incident of the ballad is of the most sinking character, and it works on the stage with truly melo-dramatic force, Perhaps, there is not a more interesting picture than a solitary tree, tufted on a time-worn ruin; there are a thousand associations in such a scene, which, to the reflective mind, are dear as life's-blood, and as an artist would say, they make a fine study.

Printed and Published by J. LIMBIRD, 143, Strand, (near Somerset House,) London; sold by ERNEST FLEISCHER, 626, New Market, Leipsic; and by all Newsmen and Booksellers.