PUNCH,

OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

Vol. 99.

November 22, 1890.

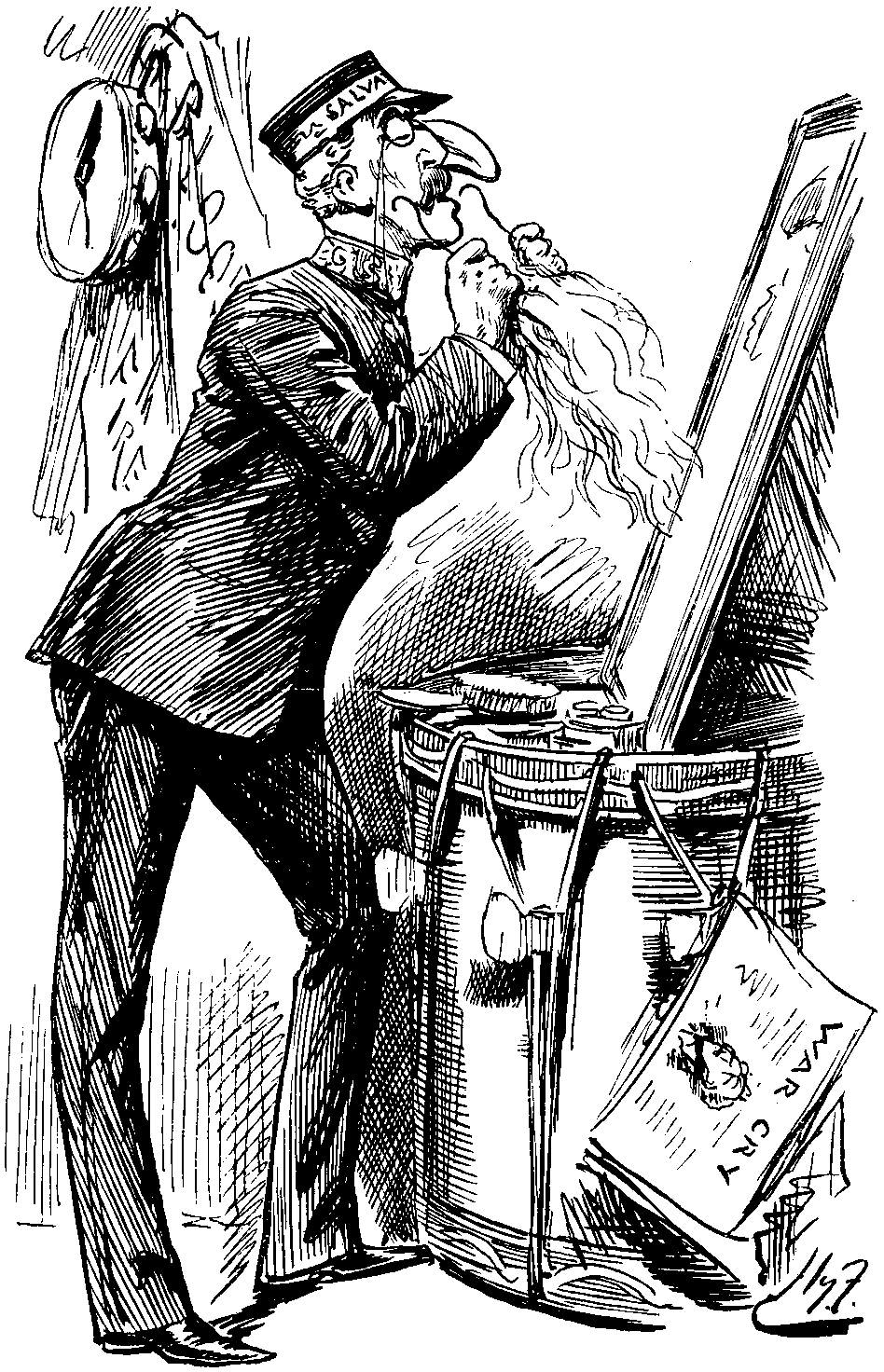

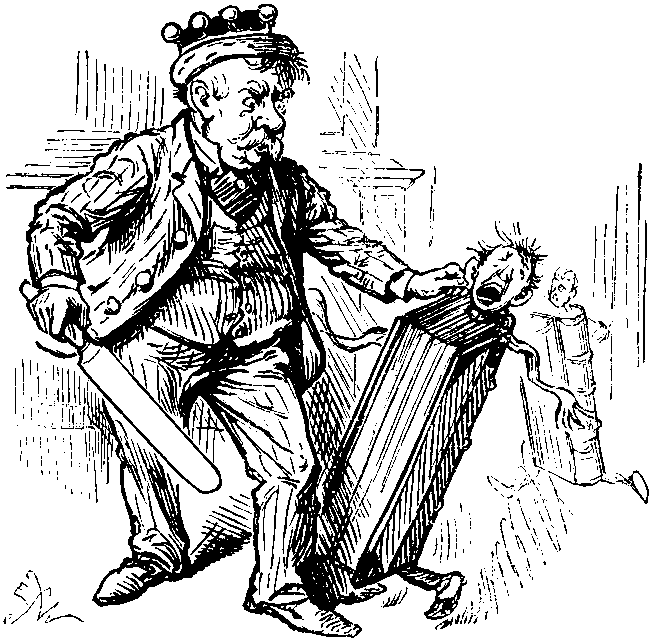

DOUBLING THE PART.

Mr. S.B. B-ncr-ft, having

retired from the Stage, thinks of taking to the Booth.

"'WHEN THE CUE COMES, CALL ME.' AW!—VERY LIKE

HIM—VERY!"

[One day last week Mr. S.B. BANCROFT wrote to the

Daily Telegraph, saying, that so struck was he by

"General" BOOTH's scheme for relieving everybody

generally—of course "generally"—that he wished

at once to relieve himself of £1000, if he could only find

out ninety-and-nine other sheep in the wilderness of London

to follow his example, and consent to be shorn of a similar

amount. Send your cheque to 85, Fleet Street, and we'll

undertake to use it for the benefit of most deserving

objects.]

A GOOD-NATURED TEMPEST.

It was stated in the Echo that, during the late

storm, a brig "brought into Dover harbour two men, with their

ribs and arms broken by a squall off Beachy Head. The

deck-house and steering-gear were carried away, and the men

taken to Dover Hospital." Who shall say, after this, that

storms do not temper severity with kindness? This particular

one, it is true, broke some ribs and arms, and carried away

portions of a brig, but, in the very act of doing this, it took

the sufferers, and laid them, apparently, on the steps of Dover

Hospital. If we must have storms, may they all imitate this

motherly example.

"WHAT A WONDERFUL BO-OY!"—In the Head-Master's

Guide for November, in the list of applicants for

Masterships, appears a gentleman who offers to teach

Mathematics, Euclid, Arithmetic, Algebra, Natural Science,

History, Geography, Book-keeping, French Grammar, Freehand, and

Perspective Drawing, the Piano, the Organ, and the Harmonium,

and Singing, for the modest salary of £20 a-year without a

residence! But it is only just to add; that this person seems

to be of marvellous origin, for although he admits extreme

youth (he says he is only three years of age!) he boasts

ten years of experience! O si sic omnes! So wise, so

young, so cheap!

If spectacular effects are worth remembering, then Sheriff

DRURIOLANUS ought to be a member of the Spectacle-makers'

Company.

ALICE IN BLUNDERLAND.

(On the Ninth of November.)

["Our difficulties are such as these—that America

has instituted a vast system of prohibitive tariffs,

mainly, I believe, because ... American pigs do not receive

proper treatment at the hands of Europe.... If we have any

difficulty with our good neighbours in France, it is

because of that unintelligent animal the lobster; and if we

have any difficulty with our good neighbours in America, it

is because of that not very much nobler animal, the

seal."—Lord Salisbury at the Mansion

House.]

The Real Turtle sang this, very slowly, and

sadly:—

"We are getting quite important," said the Porker to

the Seal,

"For we're 'European Questions,' as a Premier seems

to feel.

See the 'unintelligent' Lobster, even he, makes an

advance!

Oh, we lead the Politicians of the earth a pretty

dance.

Will you, won't you, Yankee Doodle,

England, and gay France.

Will you, won't you, will you, won't you,

let us lead the dance?

"You can really have no notion how delightful it

will be,

When they take us up as matters of the High

Diplomacee."

But the Seal replied, "They brain us!" and he gave a

look askance

At the goggle-eyed mailed Lobster, who was loved

(and boiled) by France.

"Would they, could they, would they,

could they, give us half a chance?

Lobsters, Pigs, and Seals all suffer,

Commerce to advance!"

"What matters it how grand we are!" his plated

friend replied,

If our destiny is Salad, or the Sausage boiled or

fried?

Though we breed strife 'twixt England, and America,

and France,

If we're chopped up, or boiled, or brained where is

our great advance?

Will you, won't you, will you, won't you

chuck away a chance

Of peace in pig-stye, or at sea, to play

the game of France?"

"Thank you, it's a very amusing dance—to

watch," said ALICE, feeling very glad that she had not to

stand up in it.

"You may not have lived much under the Sea" (said the Real

Turtle) ("I haven't," said ALICE), "and perhaps you were never

introduced to a Lobster—" (ALICE began to say "I once

tasted—" but checked herself hastily, and said, "No,

never"),—"So you can have no idea what a delightful dance

a (Diplomatic) Lobster Quadrille is!"

"I dare say not," said ALICE.

"Stand up and repeat ''Tis the Voice of the

Premier,'" said the Griffin.

ALICE got up and began to repeat it, but her head was so

full of Lobsters, Pigs, and Seals, that she hardly knew what

she was saying, and the words came very queer

indeed:—

"'Tis the voice of the Premier; I heard him

complain

On the Ninth of November all prophecy's vain.

I must make some sort of a speech, I

suppose.

Dear DIZZY (who led the whole world by the nose)

Said the world heard, for once, on this day, 'Truth

and Sense'

(I.e. neatly phrased Make-believe and

Pretence),

But when GLADDY's 'tide' rises, and lost seats

abound,

One's voice has a cautious and timorous sound."

"I've heard this sort of thing so often before," said the

Real Turtle; "but it sounds uncommon nonsense. Go on with the

next verse."

ALICE did not dare disobey, though she felt sure it would

all come wrong, and she went on in a trembling

voice:—

"I passed by the Session, and marked, by the

way,

How the Lion and Eagles would share Af-ri-ca.

How the peoples, at peace, were not shooting with

lead,

But bethumping each other with Tariffs instead,

How the Eight Hours' Bill, on which BURNS was so

sweet,

Was (like bye-elections) a snare and a cheat;

How the Lobster, the Pig, and the Seal, I would

say

At my sixth Lord Mayor's Banquet—"

"What is the use of repeating all that stuff," the

Real Turtle interrupted, "if you don't explain it as you go on?

It's by far the most confusing thing I ever heard!"

"Yes, I think you'd better leave off," said the Griffin; and

ALICE was only too glad to do so.

GAMES.—It being the season of burglaries, E. WOLF AND

SON—("WOLF," most appropriate name,—but Wolf and

Moon would have been still better than WOLF AND

SON)—take the auspicious time to bring out their new game

of "Burglar and Bobbies." On a sort of draught-board, so that

both Burglar and Bobby play "on the square," which is in itself

a novelty. The thief may be caught in thirteen moves. This

won't do. We want him to be caught before he moves at all.

NEW EDITION OF "ROBA DI 'ROMER.'"

With Mr.

Punch's sincere congratulations to his Old Friend the New

Judge.

VOCES POPULI.

AT A SALE OF HIGH-CLASS SCULPTURE.

SCENE—An upper floor in a City Warehouse; a

low, whitewashed room, dimly lighted by dusty windows and

two gas-burners in wire cages. Around the walls are ranged

several statues of meek aspect, but securely confined in

wooden cases, like a sort of marble menagerie. In the

centre, a labyrinthine grove of pedestals, surmounted by

busts, groups, and statuettes by modern Italian masters.

About these pedestals a small crowd—consisting of

Elderly Merchants on the look out for a "neat thing in

statuary" for the conservatory at Croydon or Muswell Hill,

Young City Men who have dropped in after lunch,

Disinterested Dealers, Upholsterers' Buyers, Obliging

Brokers, and Grubby and Mysterious men—is cautiously

circulating.

Obliging Broker (to Amiable Spectator, who

has come in out of curiosity, and without the remotest

intention of purchasing sculpture). No Catlog, Sir?

'Ere, allow me to orfer you mine—that's my name in

pencil on the top of it, Sir; and, if you should 'appen

to see any lot that takes your fancy, you jest ketch my eye.

(Reassuringly.) I shan't be fur off. Or look 'ere, gimme

a nudge—I shall know what it means.

[The A.S. thanks him profusely, and edges away

with an inward vow to avoid his and the Auctioneer's

eyes, as he would those of a basilisk.

Auctioneer (from desk, with the usual perfunctory

fervour). Lot 13, Gentlemen, very charming pair of subjects

from child life—"The Pricked Finger" and "The

Scratched Toe"—by BIMBI.

A Stolid Assistant (in shirtsleeves). Figgers

'ere, Gen'lm'n!

[Languid surge of crowd towards them.

A Facetious Bidder. Which of 'em's the finger, and

which the toe?

Auct. (coldly). I should have thought it was

easy to identify by the attitude. Now, Gentlemen, give me a

bidding for these very finely-executed works by BIMBI. Make any

offer. What will you give me for 'em? Both very sweet things,

Gentlemen. Shall we say ten guineas?

A Grubby Man. Give yer five.

Auct. (with grieved resignation). Very well,

start 'em at five. Any advance on five? (To Assist.)

Turn 'em round, to show the back view. And a 'arf! Six! And a

'arf! Only six and a 'arf bid for this beautiful pair of

figures, done direct from nature by BIMBI. Come, Gentlemen,

come! Seven! Was that you, Mr. GRIMES? (The Grubby

Man admits the soft impeachment.) Seven and a 'arf. Eight!

It's against you.

Mr. Grimes (with a supreme effort).

Two-and-six!

[Mops his brow with a red cotton

handkerchief.

Auct. (in a tone of gratitude for the smallest

mercies). Eight-ten-six. All done at eight-ten-six? Going

... gone! GRIMES, Eight, ten, six. Take money for 'em. Now we

come to a very 'andsome work by PIFFALINI—"The Ocarina

Player," one of this great artist's masterpieces, and an

exceedingly choice and high-class work, as you will all agree

directly you see it. (To Assist.) Now, then, Lot 14,

there—look sharp!

Stolid Assist. "Hocarina Plier," eyn't arrived,

Sir.

Auct. Oh, hasn't it? Very well, then. Lot 15. "The

Pretty Pill-taker," by ANTONIO BILIO—a really

magnificent work of Art, Gentlemen. ("Pill-taker, 'ere!"

from the S.A.) What'll you give me for her? Come, make me

an offer. (Bidding proceeds till the "Pill-taker" is knocked

down for twenty-three-and-a-half guineas.) Lot 16, "The

Mixture as Before," by same artist—make a charming

and suitable companion to the last lot. What do you say, Mr.

MIDDLEMAN—take it at the same bidding? (Mr. M.

assents, with the end of one eyebrow.) Any advance on

twenty-three and a 'arf? None? Then.—MIDDLEMAN,

Twenty-four, thirteen, six.

Mr. Middleman (to the Amiable Spectator,

who has been vaguely inspecting the "Pill-taker.") Don't

know if you noticed it, Sir, but I got that last couple very

cheap—on'y forty-seven guineas the pair, and they are

worth eighty, I solemnly declare to you. I could get forty

a-piece for 'em to-morrow, upon my word and honour, I could.

Ah, and I know who'd give it me for 'em, too!

The A.S. (sympathetically). Dear me, then

you've done very well over it.

Mr. M. Ah, well ain't the word—and those two

aren't the only lots I've got either. That

"Sandwich-Man" over there is mine—look at the work

in those boards, and the nature in his clay pipe; and "The

Boot-Black," that's mine, too—all worth twice what

I got 'em for—and lovely things, too, ain't

they?

The A.S. Oh, very nice, very

clever—congratulate you, I'm sure.

Mr. M. I can see you've took a fancy to 'em, Sir,

and, when I come across a gentleman that's a connysewer, I'm

always sorry to stand in his light; so, see here, you can have

any one you like out o' my little lot, or all on 'em, with all

the pleasure in the wide world, Sir, and I'll on'y charge you

five per cent. on what I gave for 'em. and be exceedingly

obliged to you, into the bargain, Sir. (The A.S.

feebly disclaims any desire to take advantage of this

magnanimous offer.) Don't say No, if you mean Yes, Sir.

Will you 'ave the "Pill-taker," Sir?

The A.S. (politely). Thank you very much,

but—er—I think not.

Mr. M. Then perhaps you could do with "The Little

Boot-Black," or "The Sandwich-Man," Sir?

The A.S. Perhaps—but I could do still better

without them.

[He moves to another part of the room.

The Obl. Broker (whispering beerily in his

ear). Seen anythink yet as takes your fancy, Sir; 'cos, if

so—

[The A.S. escapes to a dark corner—where

he is warmly welcomed by Mr. MIDDLEMAN.

Mr. M. Knew you'd think better on it, Sir. Now

which is it to be—the "Boot-Black," or "Mixture

as Before"?

Auct. Now we come to Lot 19. Massive fluted column in

coral marble with revolving-top—a column, Gentlemen,

which will speak for

itself.

The Facetious Bidder (after a scrutiny). Then

it may as well mention, while it's about it, that it's

got a bit out of its back!

Auct. Flaw in the marble, that's all. (To

Assist.) Nothing the matter with the column, is

there?

Assist. (with reluctant candour). Well, it

'as got a little chipped, Sir.

Auct. (easily). Oh, very well then, we'll sell

it "A.F." Very glad it was found out in time, I'm sure.

First Dealer to Second (in a husky whisper).

Talkin' o' Old Masters, I put young 'ANWAY up to a good thing

the other day.

Second D. (without surprise—probably from a

knowledge of his friend's noble, unselfish nature).

Ah—'ow was that?

First D. Well, there was a picter as I 'appened to

know could be got in for a deal under what it ought—in

good 'ands, mind yer—to fetch. It was a

Morlan'—leastwise, it was so like you couldn't ha' told

the difference, if you understand my meanin'. (The other

nods with complete intelligence.) Well, I 'adn't no openin'

for it myself just then, so I sez to young 'ANWAY, "You might

do worse than go and 'ave a look at it," I told him. And

I run against him yesterday, Wardour Street way, and I sez,

"Did yer go and see that picter?" "Yes," sez he, "and

what's more, I got it at pretty much my own figger, too!"

"Well," sez I, "and ain't yer goin' to shake 'ands with me

over it?"

Second D. (interested). And did he?

First D. Yes, he did—he beyaved very fair over

the matter, I will say that for him.

Second D. Oh, 'ANWAY's a very decent little

feller—now.

Auct. (hopefully). Now, Gentlemen, this next

lot'll tempt you, I'm sure! Lot 33, a magnificent and

very finely executed dramatic group out of the "Merchant of

Venice," Othello in the act of smothering

Desdemona, both nearly life-size. (Assist., with a

sardonic inflection. "Group 'ere, Gen'lm'n!")

What shall we say for this great work by ROCCOCIPPI, Gentlemen?

A hundred guineas, just to start us?

The F.B. Can't you put the two figgers up

separate?

Auct. You know better than that—being a group,

Sir. Come, come, anyone give me a hundred for this magnificent

marble group! The figure of Othello very finely

finished, Gentlemen.

The F.B. I should ha' thought it was her who

was the finely finished one of the two.

Auct. (pained by this levity). Really,

Gentlemen, do 'ave more appreciation of a 'igh-class

work like this!... Twenty-five guineas?... Nonsense! I can't

put it up at that.

[Bidding languishes. Lot withdrawn.

Second Disinterested Dealer (to First D.D., in an

undertone). I wouldn't tell everyone, but I shouldn't like

to see you stay 'ere and waste your time; so, in case

you was thinking of waiting for that last lot, I may

just as well mention—[Whispers.

First D.D. Ah, it's that way, is it? Much

obliged to you for the 'int. But I'd do the same for you any

day.

Second D.D. I'm sure yer would!

[They watch one another suspiciously.

Auct. Now 'ere's a tasteful thing, Gentlemen. Lot.

41. "Nymph eating Oysters" ("Nymph 'ere,

Gen'lm'n!"), by the celebrated Italian artist VABENE, one

of the finest works of Art in this room, and they're all

exceedingly fine works of Art; but this is truly a work

of Art, Gentlemen. What shall we say for her, eh?

(Silence.) Why, Gentlemen, no more appreciation than

that? Come, don't be afraid of it. Make a beginning.

(Bidding starts.) Forty-five guineas.

Forty-six—pounds. Forty-six pounds only, this

remarkable specimen of modern Italian Art. Forty-six and a

'arf. Only forty-six ten bid for it. Give character to any

gentleman's collection, a figure like this would. Forty-seven

pounds—guineas! and a 'arf.... Forty-seven

and a 'arf guineas.... For the last time! Bidding with you,

Sir. Forty-seven guineas and a 'arf—Gone! Name, Sir, if

you please. Oh, money? Very well. Thank you.

Proud Purchaser (to Friend, in excuse for his

extravagance). You see, I must have something for that

grotto I've got in the grounds.

His Friend. If she was mine, I should put her in the

hall, and have a gaslight fitted in the oyster-shell.

P.P. (thoughtfully). Not a bad idea. But

electric light would be more suitable, and easier to fix too.

Yes—we'll see.

The Obl. Broker (pursuing the Am. Spect.). I

'ope, Sir, you'll remember me, next time you're this way.

The Am. Spect. (who has only ransomed himself by

taking over an odd lot, consisting of imitation marble fruit, a

model, under crystal, of the Leaning Tower of Pisa, and three

busts of Italian celebrities of whom he has never heard).

I'm afraid I shan't have very much chance of forgetting you.

Good afternoon!

[Exit hurriedly, dropping the fruit, as Scene

closes.

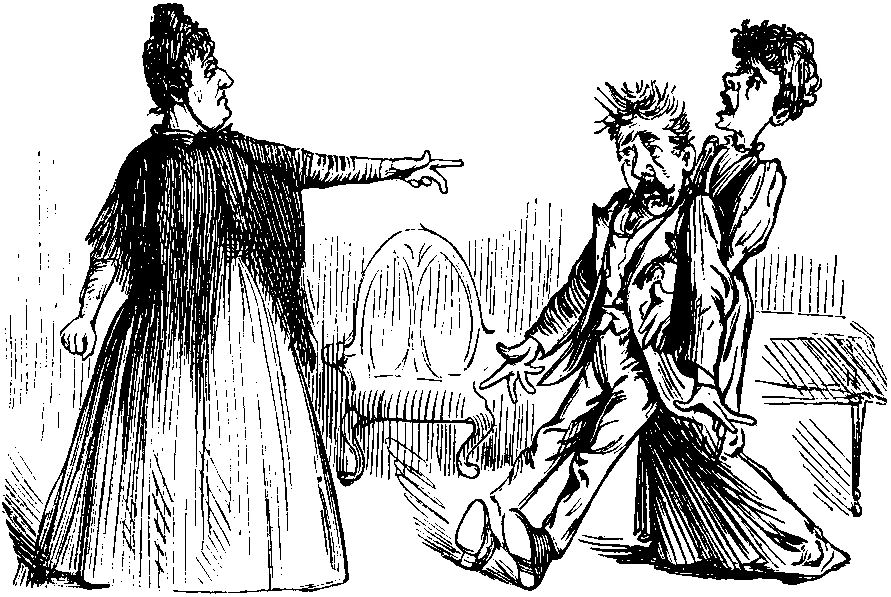

PRIVATE THEATRICALS.

Fond Parent (to Professional Lady). "TELL

ME, MISS LE VAVASOUR, DID MY SON ACQUIT HIMSELF CREDITABLY

AT THIS AFTERNOON'S REHEARSAL?"

Miss Le Vavasour. "WELL, MY LORD,—IF YOUR

SON ONLY ACTS THE LOVER ON THE STAGE HALF AS ENERGETICALLY

AS HE DOES IN THE GREEN-ROOM, THE PIECE WILL BE A

SUCCESS!"

FROM OUR MUSIC HALL.

I had a fine performance at my little place last week. Gave

the Elijah with a chorus whose vigorous delivery and

precision were excellent, and except for uncertain intonation

of soprani in first chorus, I think though perhaps I say

it who shouldn't, I never heard better chorussing within my

walls. Madame SCHMIDT-KOEHNE has a good voice, but I can't say

I approve of her German method, nor do I like embellishments of

text, even when they can be justified. The contralto,

Madame SVIATLOVSKY (O Heavenly name that ends in sky!)

is not what I should have expected, coming to us with such a

name. Perhaps not heard to advantage: perhaps 'vantage to me if

I hadn't heard her. But Miss SARAH BERRY brought down the house

just as SAMSON did, and we were Berry'd all alive, O, and

applauding beautifully. Brava, Miss SARAH BERRY!

"As we are hearing Elijah," says Mr. Corner Man, "may

I ask you, Sir, what Queen in Scripture History this young lady

reminds me of?" Of course I reply, "I give it up, Sir."

Whereupon he answers, "She reminds me, Sir, of the Queen who

was BERENICÉ—'Berry-Nicey'—see?"

Number next in the books. Mr. WATKIN MILLS was dignified and

impressive as Elijah; but, while admitting the

excellence of this profit, we can't forget our loss in the

absence of Mr. SANTLEY. BEN MIO DAVIES sang the tenor music,

but apologised for having unfortunately got a pony on the

event,—that is, he had got a little hoarse during the

day. "BEN MIO" is—um—rather troppo operatico

for the oratorio. Mr. BARNBY bravely bâtoned, as usual. Bravo,

BARNBY! He goes on with the work because he likes it. Did he

not, he would say with the General Bombastes—

"Give o'er! give o'er!

For I will bâton on this tune no more."

Perhaps the quotation is not quite exact, but no matter,

all's well that ends well, as everyone said as they left.

Yours truly,

ALBERT HALL.

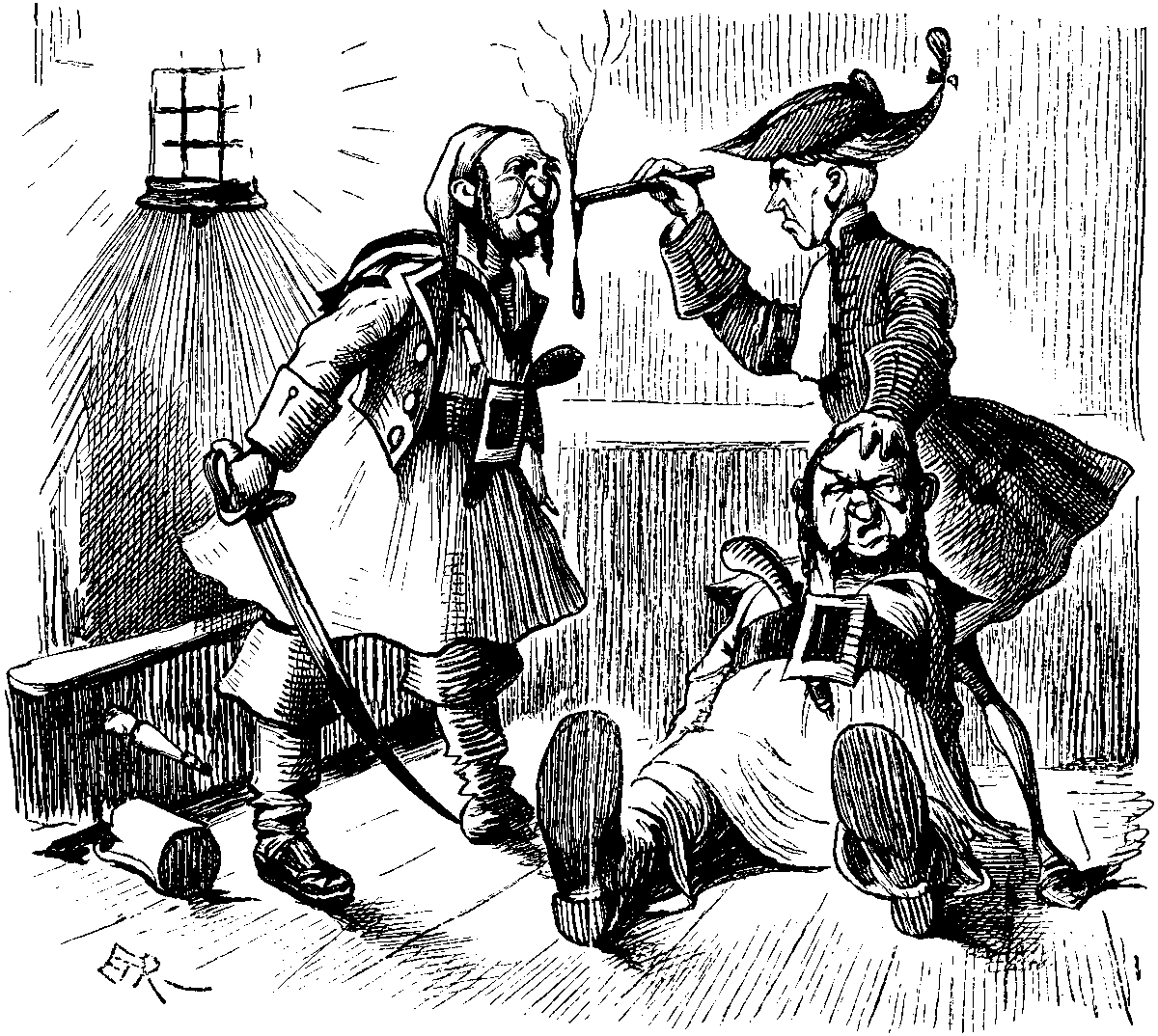

MR. PUNCH'S PRIZE NOVELS.

No. VII.—A BUCCANEER'S BLOOD-BATH.

By L.S. DEEVENSON, Author of "Toldon

Dryland," "The White Heton," "Wentnap,"

"Amiss with a Candletray," "An Outlandish Trip,"

"A Travelled Donkey," "A Queer Fall on a Treacle

Slide," "The Old Persian Baronets," &c.,

&c., &c.

[For some weeks before this Novel actually arrived, we

received by every post an immense consignment of

paragraphs, notices, and newspaper cuttings, all referring

to it in glowing terms. "This" observed the Bi-weekly

Boomer, "is, perhaps, the most brilliant effort of the

brilliant and versatile Author's genius. Humour and pathos

are inextricably blended in it. He sweeps with confident

finger over the whole gamut of human emotions, and moves us

equally to terror and to pity. Of the style, it is

sufficient to say that it is Mr. DEEVENSON's." The MS. of

the Novel itself came in a wrapper bearing the Samoan

post-mark.—ED. Punch.]

CHAPTER I.

I am a man stricken in years, and-well-nigh spent with

labour, yet it behoves that, for the public good, I should take

pen in hand, and set down the truth of those matters wherein I

played a part. And, indeed, it may befall that, when the tale

is put forth in print, the public may find it to their liking,

and buy it with no sparing hand, so that, at the last, the

payment shall be worthy of the labourer.

I have never been gifted with what pedants miscall courage.

That extreme rashness of the temper which drives fools to their

destruction hath no place in my disposition. A shrinking

meekness under provocation, and a commendable absence of body

whenever blows fell thick, seemed always to me to be the better

part. And for this I have boldly endured many taunts. Yet it so

chanced that in my life I fell in with many to whom the cutting

of throats was but a moment's diversion. Nay, more, in most of

their astounding ventures I shared with them; I made one upon

their reckless forays; I was forced, sorely against my will, to

accompany them upon their stormy voyages, and to endure with

them their dangers; and there does not live one man, since all

of them are dead, and I alone survive, so well able as myself

to narrate these matters faithfully within the compass of a

single five-shilling volume.

CHAPTER II.

On a December evening of the year 17—, ten men sat

together in the parlour of "The Haunted Man." Without, upon the

desolate moorland, a windless stricture of frost had bound the

air as though in boards, but within, the tongues were loosened,

and the talk flowed merrily, and the clink of steaming tumblers

filled the room. Dr. DEADEYE sat with the rest at the long deal

table, puffing mightily at the brown old Broseley

church-warden, whom the heat and the comfort of his evening

meal had so far conquered, that he resented the doctor's

treatment of him only by an occasional splutter. For myself, I

sat where the warmth of the cheerful fire could reach my

chilled toes, close by the side of the good doctor. I was a

mere lad, and even now, as I search in my memory for these

long-forgotten scenes, I am prone to marvel at my own

heedlessness in thus affronting these lawless men. But, indeed,

I knew them not to be lawless, or I doubt not but that my

prudence had counselled me to withdraw ere the events befell

which I am now about to narrate.

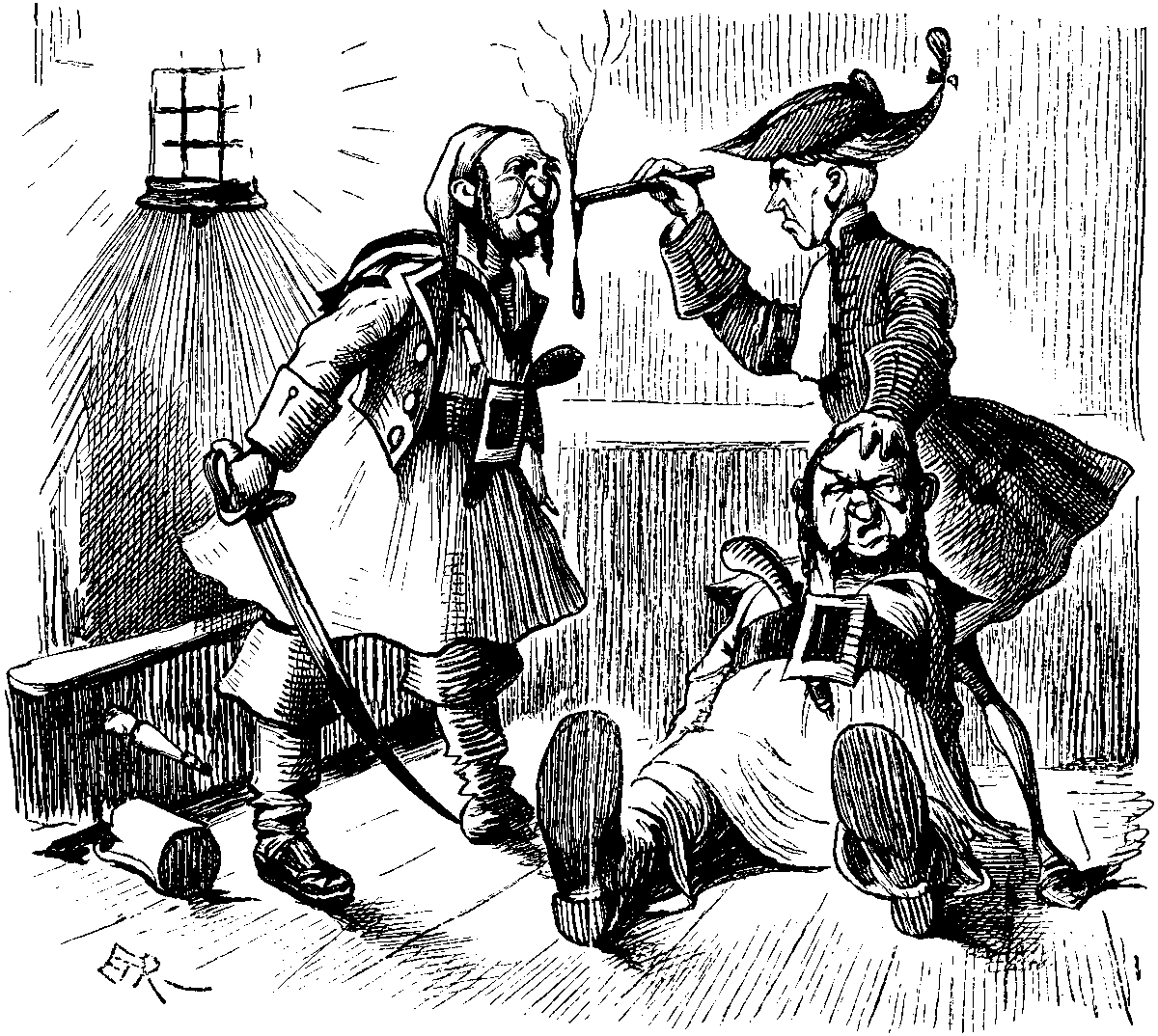

As I remember, the Doctor and Captain JAWKINS were seated

opposite to one another, and, as their wont was, they were in

high debate upon a question of navigation, on which the Doctor

held and expressed an emphatic opinion.

"Never tell me," he said, with flaming aspect, "that the

common term, 'Port your helm,' implies aught but what a man,

not otherwise foolish, would gather from the word. Port means

port, and starboard is starboard, and all the d——d

sea-captains in the world cannot move me from that." With that

the Doctor beat his fist upon the table until the glasses

rattled again and glared into the Captain's weather-beaten

face.

1

"Hear the man," said the Captain—"hear him. A man

would think he had spent his days and nights upon the sea,

instead of mixing pills and powders all his life in a snuffy

village dispensary."

The quarrel seemed like to be fierce, when a sudden sound

struck upon our ears, and stopped all tongues. I cannot call it

a song. Rather, it was like the moon-struck wailing of some

unhappy dog, low, and unearthly; and yet not that, either, for

there were words to it. That much we all heard distinctly.

"Fifteen two and a pair make four,

Two for his heels, and that makes six."

We listened, awestruck, with blanched faces, scarce daring

to look at one another. For myself, I am bold to confess that I

crept under the sheltering table and hid my head in my hands.

Again the mournful notes were moaned forth—

"Fifteen two and a pair make four,

Two for his heels, and—"

But ere it was ended, Captain JAWKINS had sprung forward,

and rushed into the further corner of the parlour. "I know that

voice," he cried aloud; "I know it amid a thousand!" And even

as he spoke, a strange light dispelled the shadows, and by its

rays we could see the crouching form of BILL BLUENOSE, with the

red seam across his face where the devil had long since done

his work.

CHAPTER III.

I had forgot to say that, as he ran, the Captain had drawn

his sword. In the confusion which followed on the discovery of

BLUENOSE, I could not rightly tell how each thing fell out;

indeed, from where I lay, with the men crowding together in

front of me, to see at all was no easy matter. But this I saw

clearly. The Captain stood in the corner, his blade raised to

strike. BLUENOSE never stirred, but his breath came and went,

and his eyelids blinked strangely, like the flutter of a sere

leaf against the wall. There came a roar of voices, and, in the

tumult, the Captain's sword flashed quickly, and fell. Then,

with a broken cry like a sheep's bleat, the great seamed face

fell separate from the body, and a fountain of blood rose into

the air from the severed neck, and splashed heavily upon the

sanded floor of the parlour.

"Man, man!" cried the Doctor, angrily, "what have ye done?

Ye've kilt BLUENOSE, and with him goes our chance of the

treasure. But, maybe, it's not yet too late."

So saying, he plucked the head from the floor and clapped it

again upon its shoulders. Then, drawing a long stick of

sealing-wax from his pocket, he held it well before the

Captain's ruddy face. The wax splattered and melted. The Doctor

applied it to the cut with deft fingers, and with a strange

condescension of manner in one so proud. My heart beat like a

bird's, both quick and little; and on a sudden BLUENOSE raised

his dripping hands, and in a quavering kind of voice piped

out—

"Fifteen two and a pair make four."

But we had heard too much, and the next moment we were

speeding with terror at our backs across the desert

moorland.

CHAPTER IV.

You are to remember that when the events I have narrated

befell I was but a lad, and had a lad's horror of that which

smacked of the supernatural. As we ran, I must have fallen in a

swoon, for I remember nothing more until I found myself walking

with trembling feet through the policies of the ancient mansion

of Dearodear. By my side strode a young nobleman, whom I

straightway recognised as

[pg 245] the Master. His gallant

bearing and handsome face served but to conceal the black

heart that beat within his breast. He gazed at me with a

curious look in his eyes.

"SQUARETOES, SQUARETOES," said he—it was thus he had

named me, and by that I knew that we were in Scotland, and that

my name was become MACKELLAR—"I have a mind to end your

prying and your lectures here where we stand."

"End it," said I, with a boldness which seemed strange to me

even as I spoke; "end it, and where will you be? A penniless

beggar and an outcast."

"The old fool speaks truly," he continued, kicking me twice

violently in the back, but otherwise ignoring my presence; "and

if I end him, who shall tell the story? Nay, SQUARETOES, let us

make a compact. I will play the villain, and brawl, and cheat,

and murder; you shall take notes of my actions, and, after I

have died dramatically in a North American forest, you shall

set up a stone to my memory, and publish the story. What say

you? Your hand upon it."

Such was the fascination of the man that even then I could

not withstand him. Moreover, the measure of his misdeeds was

not yet full. My caution prevailed, and I gave him my hand.

"Done!" said he; "and a very good bargain for you,

SQUARETOES!"

Let the public, then, judge between me and the Master, since

of his house not one remains, and I alone may write the

tale.

(To be continued.—Author.) THE END.—Ed.

Punch.

OUR BOOKING-OFFICE.

The Children of the Castle, by Mrs. MOLESWORTH

(published by MACMILLAN), will certainly be a favourite with

the children in the house. A quaintly pretty story of child

life and fairies, such as she can write so well, it is valuably

assisted with Illustrations by WALTER CRANE.

GEORGE ROUTLEDGE evidently means to catch the youthful

book-worm's eye by the brilliancy of his bindings, but the

attraction will not stay there long, for the contents are equal

to the covers.

These are days of reminiscences, so "Bob," the Spotted

Terrier, writes his own tale, or, wags it. Illustrations by

HARRISON WEIR. And here for the tiny ones, bless 'em, is The

House that Jack Built,—a paper book in actually the

very shape of the house he built! And then there's the

melancholy but moral tale of Froggy would a-Wooing Go.

"Recommended," says the Baron.

Published by DEAN AND SON, who should call their publishing

establishment "The Deanery," is The Doyle Fairy Book, a

splendid collection of regular fairy lore; and the

Illustrations are by RICHARD DOYLE, which needs nothing

more.

The Mistletoe Bough, edited by M.E. BRADDON, is not

only very strong to send forth so many sprigs, but it is a

curious branch, as from each sprig hangs a tale. The first, by

the Editor and Authoress, His Oldest Friends, is

excellent.

Flowers of The Hunt, by FINCH MASON, published by

Messrs. FORES. Rather too spring-like a title for a sporting

book, as it suggests hunting for flowers. Sketchy and

amusing.

HACHETTE AND CIE, getting ahead of Christmas, and neck and

neck with the New Year, issue a Nouveau Calendrier

Perpéteul, "Les Amis Fidèles," representing three

poodles, the first of which carries in his mouth the day of the

week, the second the day of the month, and the third the name

of the month. This design is quaint, and if not absolutely

original, is new in the combination and application.

Unfortunately it only suggests one period of the year, the

dog-days, but in 1892 this can be improved upon, and

amplified.

No nursery would be complete without a Chatterbox,

and, as a reward to keep him quiet, The Prize would come

in useful. WELLS, DARTON, & GARDNER, can supply both of

them.

F. WARNE has another Birthday-book, Fortune's Mirror, Set

in Gems, by M. HALFORD, with Illustrations by KATE

CRAUFORD. A novel idea of setting the mirror in the binding;

but, to find your fortune, you must look inside, and then you

will see what gem ought to be worn in the month of your

birth.

WILLERT BEALE's Light of Other Days is most

interesting to those who, like the Baron, remember the latter

days of GRISI and MARIO, who can call to mind MARIO in Les

Huguenots, in Trovatore, in Rigoletto; and

GRISI in Norma, Valentina, Fides,

Lucrezia, and some others. It seems to me that the

centre of attraction in these two volumes is the history of

MARIO and GRISI on and off the stage; and the gem of all is the

simple narrative of Mrs. GODFREY PEARSE, their daughter, which

M. WILLERT BEALE has had the good taste to give

verbatim, with few notes or comments. To think that only

twenty years ago we lost GRISI, and that only nine years ago

MARIO died in Rome! Peace to them both! In Art they were a

glorious couple, and in their death our thoughts cannot divide

them. GRISI and MARIO, Queen and King of song, inseparable. I

have never looked upon their like again, and probably never

shall. My tribute to their memory is, to advise all those to

whom their memory is dear, and those to whom their memory is

but a tradition, to read these Reminiscences, of them and of

others, by WILLERT BEALE, in order to learn all they can about

this romantic couple, who, caring little for money, and

everything for their art, were united in life, in love, in

work, and, let us, peccatores, humbly hope, in death.

WILLERT BEALE has, in his Reminiscences, given us a greater

romance of real life than will be found in twenty volumes of

novels, by the most eminent authors. Yet all so naturally and

so simply told. At least so, with moist eyes, says your

tender-hearted critic,

THE SYMPATHETIC BARON DE BOOK-WORMS.

WIGS AND RADICALS.

["As a protest against the acceptance by the Corporation

of Sunderland of robes, wigs, and cocked hats, for the

Mayor and Town Clerk, Mr. STOREY, M.P., has sent in his

resignation of the office of Alderman of that

body."—Daily Paper.]

Brutus. Tell us what has chanced to-day, that STOREY

looks so sad.

Casca. Why, there was a wig and a cocked hat offered

him, and he put it away with the back of his hand, thus; and

then the Sunderland Radicals fell a-shouting.

Brutus. What was the second noise for?

Casca. Why, for that too.

Brutus. They shouted thrice—what was the last

cry for?

Casca. Why, for that too—not to mention a

municipal robe.

Brutus. Was the wig, &c, offered him thrice?

Casca. Ay, marry, was it, and he put the things by

thrice, every time more savagely than before.

Brutus. Who offered him the wig?

Casca. Why, the Sunderland Municipality, of

course—stoopid!

Brutus. Tell us the manner of it, gentle CASCA.

Casca. I can as well be hanged, as tell you. It was

mere foolery, I did not mark it. I saw the people offer a

cocked hat to him—yet 'twas not to him neither, because

he's only an Alderman, 'twas to the Mayor and Town

Clerk—and, as I told you, he put the things by thrice;

yet, to my thinking, had he been Mayor, he would fain have had

them. And the rabblement, of course, cheered such an exhibition

of stern Radical simplicity, and STOREY called the wig a

bauble, though, to my thinking, there's not much bauble about

it, and the cocked-hat he called a mediæval intrusion, though,

to my thinking, there were precious few cocked-hats in the

Middle Ages. Then he said he would no more serve as Alderman;

and the Mayor and the Town Clerk cried—"Alas, good

soul!"—and accepted his resignation with all their

hearts.

Brutus. Then will not the Sunderland Town Hall miss

him?

Casca. Not it, as I am a true man! There'll be a

STOREY the less on it, that's all. Farewell!

"Not there, Not there, My Child!"

By some misadventure I was unable to attend the pianoforte

recital of Paddy REWSKI, the player from Irish Poland at the

St. James's Hall last Wednesday. Everybody much pleased, I'm

told. Glad to hear it. I was "Not there, not there, my child!"

But audience gratified—

"And Stalldom shrieked when Paddy REWSKI played,"

as the Poet says, or something like it. I hear he made a

hit. The papers say he did, and if he didn't it's another

thumper, that's all.

"SO NO MAYER AT PRESENT FROM YOURS TRULY THE ENTREPRENEUR OF

THE FRENCH PLAYS, ST. JAMES'S THEATRE."—It is hard on the

indefatigable M. MAYER, but when Englishmen can so easily cross

the Channel, and so willingly brave the mal-de-mer for

the sake of a week in Paris, it is not likely that they will

patronise French theatricals in London, even for their own

linguistic and artistic improvement, or solely for the benefit

of the deserving and enterprising M. MAYER. Even if it be

mal-de-mer against bien de Mayer, an English

admirer of French acting would risk the former to get a week in

Paris. We are sorry 'tis so, but so 'tis.

"THE MAGAZINE RIFLE."—Is this invention patented by

the Editor of The Review of Reviews? Good title for the

Staff of that Magazine, "The Magazine Rifle Corps."

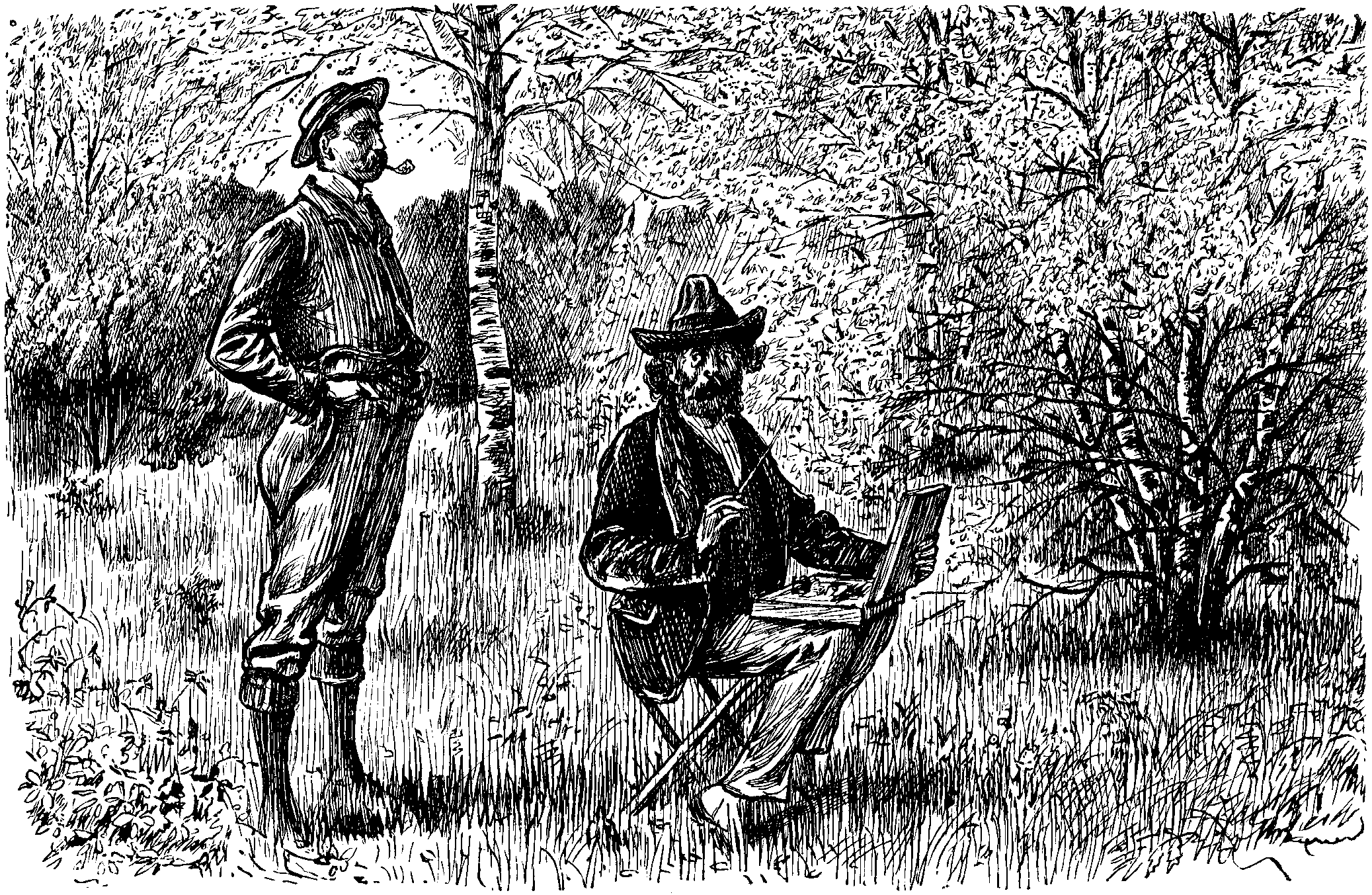

UNNECESSARY CANDOUR.

Critic. "BY JOVE, HOW ONE CHANGES! I'VE QUITE

CEASED TO ADMIRE THE KIND OF PAINTING I USED TO THINK SO

CLEVER TEN YEARS AGO; AND VICE VERSÂ!"

Pictor. "THAT'S AS IT SHOULD BE! IT SHOWS

PROGRESS, DEVELOPMENT! IT'S AN UNMISTAKABLE PROOF THAT

YOU'VE REACHED A HIGHER INTELLECTUAL AND ARTISTIC LEVEL, A

MORE ADVANCED STAGE OF CULTURE, A LOFTIER—"

Critic. "I'M GLAD YOU THINK SO, OLD MAN. BUT,

CONFOUND IT, YOU KNOW!—THE KIND OF PAINTING I USED TO

THINK SO CLEVER TEN YEARS AGO, HAPPENS TO BE

YOURS!"

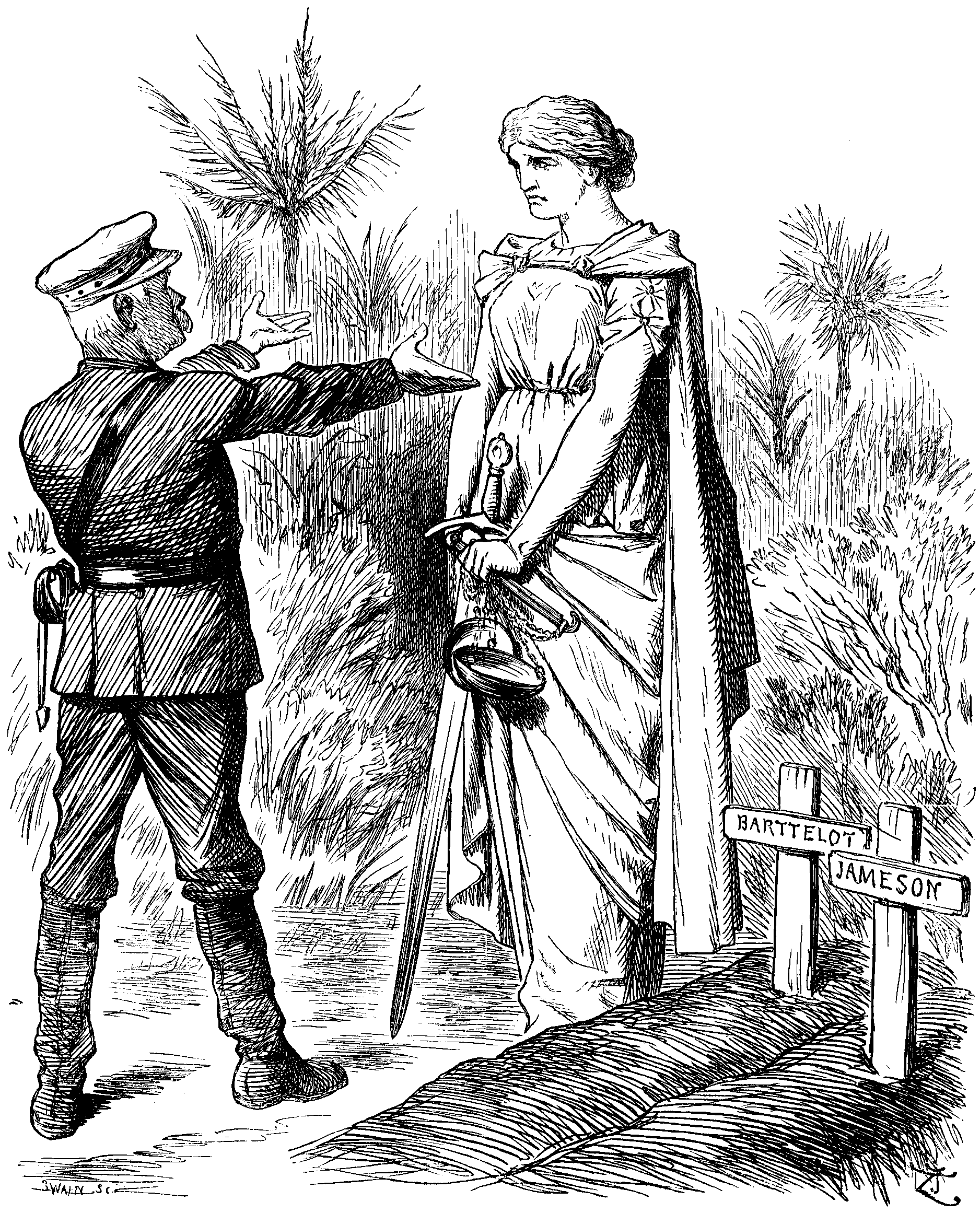

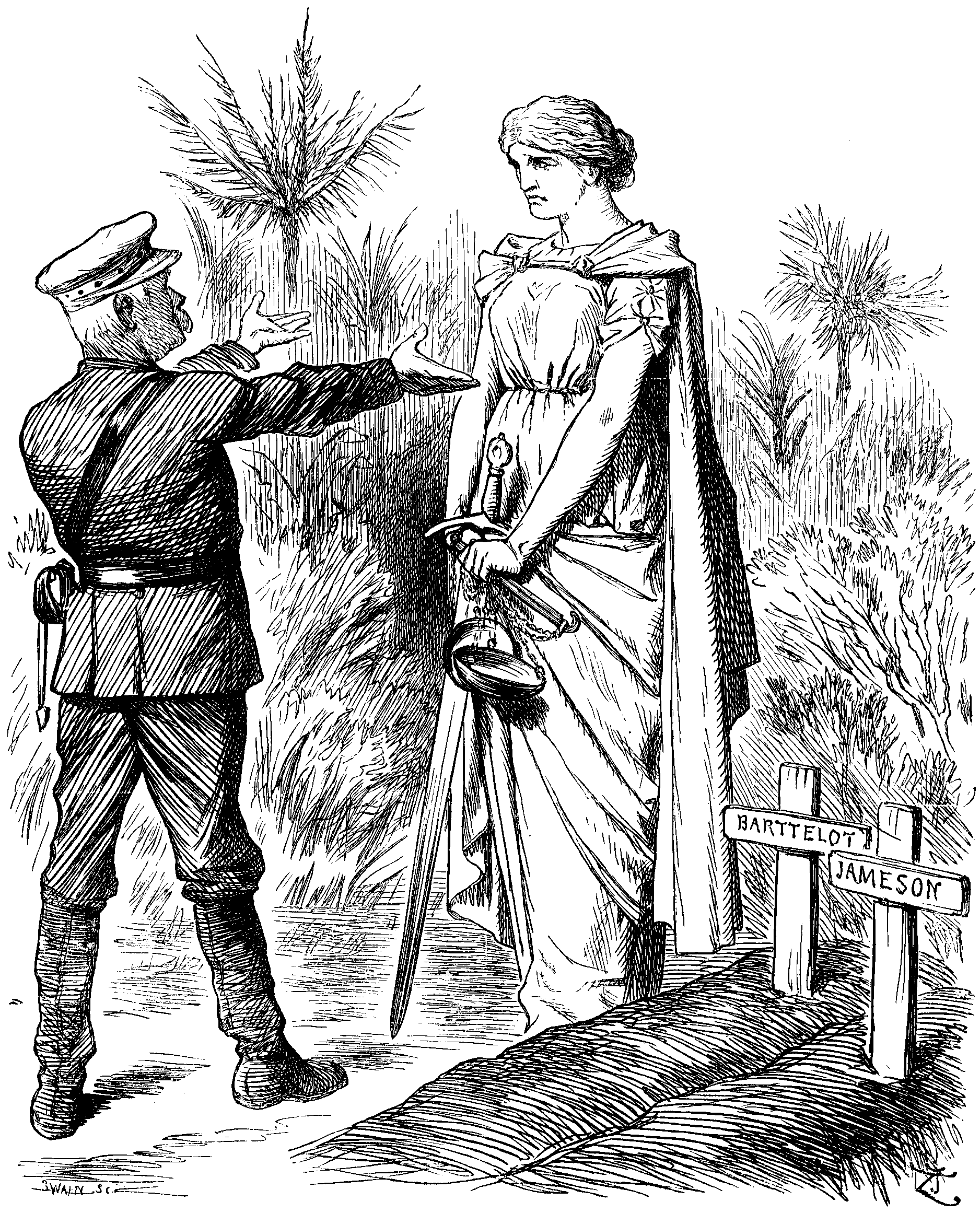

BETWEEN THE QUICK AND THE DEAD.

The Appeal's to Justice! Justice lendeth ear

Unstirred by favour, unseduced by fear;

And they who Justice love must check the thrill

Of natural shame, and listen, and be still.

These wrangling tales of horror shake the heart

With pitiful disgust. Oh, glorious part

For British manhood, much bepraised, to play

In that dark land late touched by culture's day!

Are these our Heroes pictured each by each?

We fondly deemed that where our English speech

Sounded, there English hearts, of mould humane.

Justice would strengthen, cruelty restrain.

And is it all a figment of false pride?

Such horrors do our vaunting annals hide

Beneath a world of words, like flowers that wave

In tropic swamps o'er a malarious grave?

These are the questions which perforce intrude

As the long tale of horror coarse and crude,

Rolls out its sickening chapters one by one.

What will the verdict be when all is done?

Conflicting counsels in loud chorus rise,

"Hush the thing up!" the knowing cynic cries,

"Arm not our chuckling enemies at gaze

With charnel dust to foul our brightest bays!

Let the dead past bury its tainted dead,

Lest aliens at our 'heroes' wag the head."

"Shocking! wails out the sentimentalist.

Believe no tale unpleasant, scorn to list

To slanderous charges on the British name!

That brutish baseness, or that sordid shame

Can touch 'our gallant fellows,' is a thing

Incredible. Do not our poets sing,

Our pressmen praise in dithyrambic prose,

The 'lads' who win our worlds and face our foes?

Who never, save to human pity, yield

One step in wilderness or battlefield!"

Meanwhile, with troubled eyes and straining

hands,

Silent, attentive, thoughtful, Justice stands.

To her alone let the appeal be made.

Heroes, or merely tools of huckstering Trade,

Men brave, though fallible, or sordid brutes,

Let all be heard. Since each to each imputes

Unmeasured baseness, somewhere the black

stain

Must surely rest. The dead speak not, the slain

Have not a voice, save such as that which spoke

From ABEL's blood. Green laurels, or the stroke

Of shame's swift scourge? There's the

alternative

Before the lifted eyes of those who live.

One fain would see the grass unstained that

waves

In the dark Afric waste o'er those two graves.

To Justice the protagonist makes appeal.

Justice would wish him smirchless as her steel,

But stands with steadfast eyes and unbowed head

Silent—betwixt the Living and the Dead!

OPERA NOTES.

What's a Drama without a Moral, and what's Rigoletto

without a MAUREL, who was cast for the part, but who was too

indisposed to appear? So Signor GALASSI came and "played the

fool" instead, much to the satisfaction of all concerned, and

all were very much concerned about the illness or indisposition

of M. MAUREL. DIMITRESCO not particularly strong as the

Dook; but Mlle. STROMFELD came out well as Gilda,

and, being called, came out in excellent form in front of the

Curtain. Signor BEVIGNANI, beating time in Orchestra, and time

all the better for his beating.

"FOR THIS RELIEF MUCH THANKS."—The difficulties in The

City, which Mr. Punch represented in his Cartoon of

November 8, were by the Times of last Saturday publicly

acknowledged to be at an end. The adventurous mariners were

luckily able to rest on the Bank, and are now once more fairly

started. They will bear in mind the warning of the Old Lady of

Threadneedle Street, as given to the boys in the above

mentioned Cartoon.

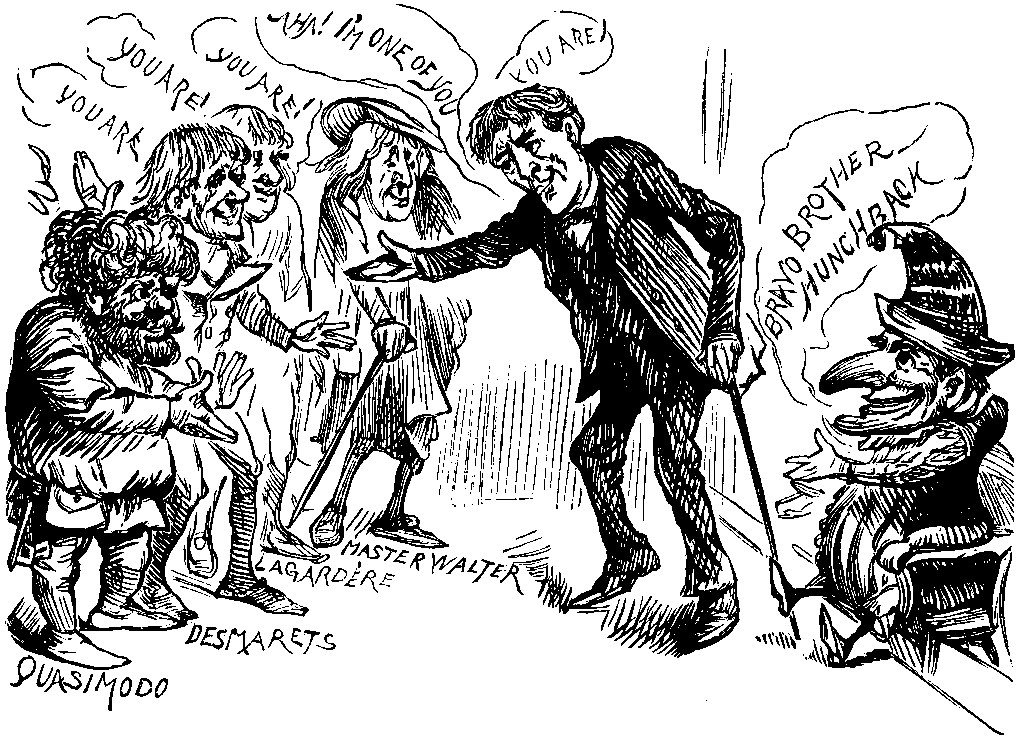

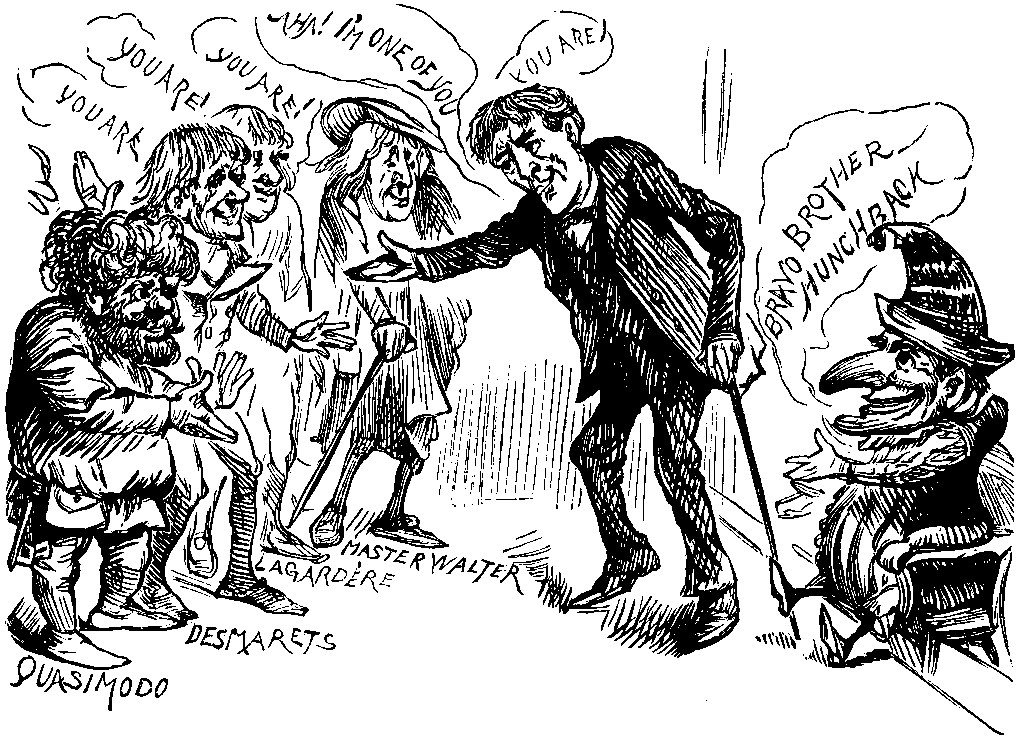

BETWEEN THE QUICK AND THE DEAD.

AVENUE HUNCHBACK.

Mr. Punch applauding Master Walter George

Desmarets.

Of course there is nothing very new in the idea of a cripple

loving a beautiful maiden, while the beautiful maiden bestows

her affections on somebody else. SHERIDAN KNOWLES's Hunchback,

Master Walter, is an exception to Hunchbacks generally,

as he turns out to be the father, not the lover, of the leading

lady. It has remained for Mr. CARTON to give us in an original

three-act play a deformed hero, who has to sacrifice love to

duty, or, rather, to let self-abnegation triumph over the

gratification of self. This self-sacrificing part is admirably

played by Mr. GEORGE ALEXANDER, whose simple make-up for the

character is irreproachable. That something more can still be

made by him of the scene of his great temptation I feel sure,

and if he does this he will have developed several full leaves

from his already budding laurels, and, which is presently

important, he will have added another 100 nights to the

run.

Dr. Latimer at the Steak. Historical

subject treated in Act II. of

S. & S.

Maud (without the final "e") capitally

played by Miss MAUDE (with the final "E") MILLETT. (Why

didn't the author choose another name when this character was

cast to Miss MILLETT? Not surely for the sake of someone

saying, "Come into the garden"—eh? And the author has

already indulged his pungent humour by giving "George"

Addis to "GEORGE" ALEXANDER. Mistake.) This character of

Maud is a sketch of an utterly odious

girl,—odious, that is, at home, but fascinating no doubt,

away from the domestic circle. Is a sketch of such a character

worth the setting? How one pities the future Bamfield

ménage, when the unfortunate idiot Bamfield, well

represented by Mr. BEN WEBSTER, has married this flirting,

flighty, sharp-tongued, selfish little girl. To these two are

given some good, light, and bright comedy scenes, recalling to

the mind of the middle-aged playgoer the palmy days of what

used to be known as the Robertsonian "Tea-cup-and-saucer

Comedies," with dialogue, scarcely fin de siècle

perhaps, but pleasant to listen to, when spoken by Miss MAUDE

MILLETT, MISS TERRY, and Mr. BEN WEBSTER.

"The Shadow," but more like the

substance. Collapse of Mr. Yorke Stephens into the

arms of Miss Marrying Terry, on hearing the Shadow

exclaim, "Yorke (Stephens), you're wanted!"

In Miss MARION TERRY's Helen, the elder of the

Doctor's daughters, we have a charming type, nor could Mr.

NUTCOMBE GOULD's Dr. Latimer be improved upon as an

artistic performance where repose and perfectly natural

demeanour give a certain coherence and solidity to the entire

work. Mr. YORKE STEPHENS as Mark Denzil is too heavy,

and his manner conveys the impression that, at some time or

other, he will commit a crime, such, perhaps, as stealing the

money from the Doctor's desk; or, when this danger is past and

he hasn't done it, his still darkening, melodramatic manner

misleads the audience into supposing that in Act III, he will

make away with his objectionable wife, possess himself of the

two hundred pounds, and then, just at the moment when, with a

darkling scowl and a gleaming eye, he steps forward to claim

his affianced bride, Scollick, Mr. ALFRED HOLLES,

hitherto only known as the drunken gardener, will throw off his

disguise, and, to a burst of applause from an excited audience,

will say, "I arrest you for murder and robbery! and—I am

HAWKSHAW the Detective!!!" or words to this effect. In his

impersonation of Mark Denzil Mr. STEPHENS seems to have

attempted an imitation of the light and airy style of Mr.

ARTHUR STIRLING.

The end of the Second Act is, to my thinking, a mistake in

dramatic art. Everyone of the audience knows that the woman who

has stolen the money is Mark Denzil's wife, and nobody

requires from Denzil himself oral confirmation of the

fact, much less do they want an interval of several

minutes,—it may be only seconds, but it seems

minutes,—before the Curtain descends, occupied only by

Mark Denzil imploring that his wife shall not be taken

before the magistrate and be charged with theft. This is an

anti-climax, weakening an otherwise effective situation, as the

immediate result of this scene could easily be given in a

couple of sentences of dialogue at the commencement of the last

Act. It is this fault, far more than the unpruned passages of

dialogue, that makes this interesting and well acted play

seem too long—at least, such is the honest opinion

of A FRIEND IN FRONT.

THE BURDEN OF BACILLUS.

Is there no one to protect us, is existence then a

sin,

That we're worried here in London and in Paris and

Berlin?

We would live at peace with all men, but "Destroy

them!" is the cry,

Physiological assassins are not happy till we

die.

With the rights of man acknowledged, can you wonder

that we squirm

At the endless persecution of the much-maltreated

germ.

We are ta'en from home and hearthstone, from the

newly-wedded bride,

To be looked at by cold optics on a microscopic

slide;

We are boiled and stewed together, and they never

think it hurts;

We're injected into rabbits by those hypodermic

squirts:

Never safe, although so very insignificant in

size,

There's no peace for poor Bacillus, so it seems,

until he dies.

It is strange to think how men lived in the days of

long ago,

When the fact of our existence they had never

chanced to know.

If the scientific ghouls are right who hunt us to

the death,

Those who came before them surely had expired ere

they drew breath:

We were there in those old ages, thriving in our

youthful bloom;

Then there was no KOCH or PASTEUR bent on compassing

our doom.

Men humanity are preaching, and philanthropists

elate

Point out he who injures horses shall be punished by

the State;

Dogs are carefully protected, likewise the domestic

cats,

Possibly kind-hearted people would not draw the line

at rats:

If all that be right and proper, why then persecute

and kill us?

Lo! the age's foremost martyr is the vilified

Bacillus!

WALK UP!

As far as Vigo Street, and see Mr. NETTLESHIP's Wild Beast

Show at the sign of "The Rembrandt Head." Here are Wild Animals

to be seen done from the life, and to the life; tawny lions,

sleepy bears, flapping vultures, and eagles, and brilliant

macaws—all in excellent condition. Observe the "Lion

roaring" at No. 28, and the "Ibis flying" with the sunlight on

his big white wings against a deep blue sky, No. 36. All these

Wild Animals can be safely guaranteed as pleasant and agreeable

companions to live with, and so, judging from certain labels on

the frames, the British picture-buyer has already discovered.

Poor Mr. NETTLESHIP's Menagerie will return to him shorn of its

finest specimens—that is, if he ever sees any of them

back at all.

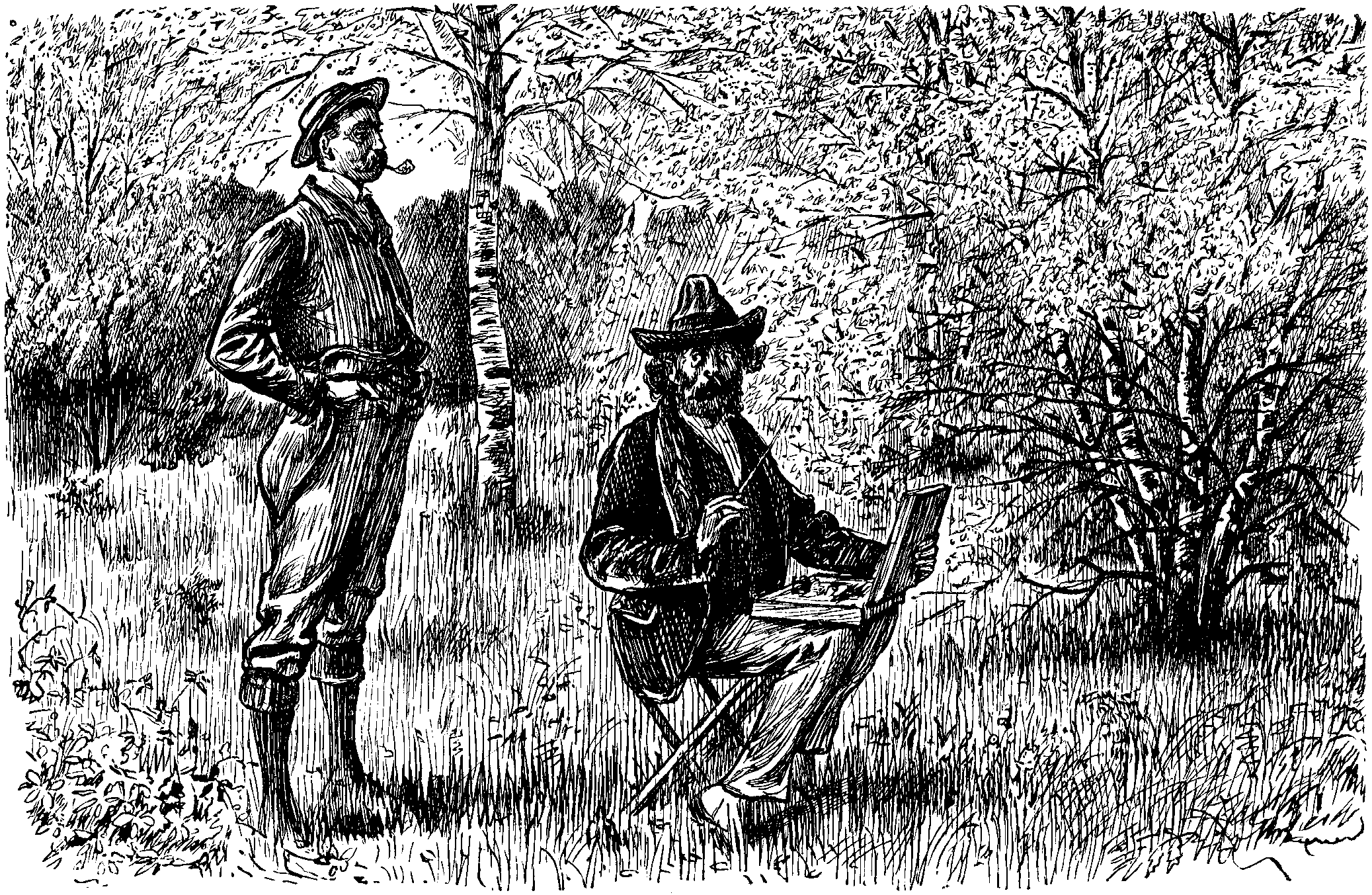

IN OUR GARDEN.

It has occurred to me in looking back over these

unpremeditated notes, that if by any chance they came to be

published, the public might gain the impression that the Member

for SARK and I did all the work of the Garden, whilst our hired

man looked on. SARK, to whom I have put the case, says that is

precisely it. But I do not agree with him. We have, as I have

already explained, undertaken this new responsibility from a

desire to preserve health and strength useful to our QUEEN and

Country. Therefore we, as ARPACHSHAD says, potter about the

Garden, get in each other's way, and in his; that is to say, we

are out working pretty well all day, with inadequate intervals

for meals.

ARPACHSHAD, to do him justice, is most anxious not to

interfere with our project by unduly taking labour on himself.

When we are shifting earth, and as we shift it backwards and

forwards there is a good deal to be done in that way, he is

quite content to walk by the side, or in front of the barrow,

whilst SARK wheels it, and I walk behind, picking up any bits

that have shaken out of the vehicle. (Earth trodden into the

gravel-walk would militate against its efficiency.) But of

course ARPACHSHAD is, in the terms of his contract, "a working

gardener," and I see that he works.

At the same time it must be admitted that he does not

display any eagerness in engaging himself, nor does he rapidly

and energetically carry out little tasks which are set him.

There are, for example, the sods about the trees in the

orchard. He says it's very bad for the trees to have the sods

close up to their trunks. There should be a small space of open

ground. ARPACHSHAD thought that perhaps "the gents," as he

calls us, would enjoy digging a clear space round the trees. We

thought we would, and set to work. But SARK having woefully

hacked the stem of a young apple-tree (Lord Suffield)

and I having laboriously and carefully cut away the entire

network of the roots of a damson-tree, under the impression

that it was a weed, it was decided that ARPACHSHAD had better

do this skilled labour. We will attain to it by-and-by.

ARPACHSHAD has now been engaged on the work for a fortnight,

and I think it will carry him on into the spring. The way he

walks round the harmless apple-tree before cautiously putting

in the spade, is very impressive. Having dug three exceedingly

small sods, he packs them in a basket, and then, with a great

sigh, heaves it on to his shoulder, and walks off to store the

sods by the potting-shed. Anything more solemn than his walk,

more depressing than his mien, has not been seen outside a

churchyard. If he were burying the child of his old age, he

could not look more cut up. SARK, who, probably owing to

personal associations, is beginning to develop some sense of

humour, walked by the side of him this morning whistling

"The Dead March in Saul."

The effect was unexpected and embarrassing. ARPACHSHAD

slowly relieved himself of the burden of the three sods,

dropped them on the ground with a disproportionate thud, and,

producing a large pocket-handkerchief, whose variegated and

brilliant colours were, happily, dimmed by a month's use,

mopped his eyes.

"You'll excuse me, gents," he snuffled, "but I never

hear that there tune, 'Rule Britanny,' whistled or sung

but I think of the time when I went down to see my son off from

Portsmouth for the Crimee, 'Rule Britanny' was the tune

they played when he walked proudly aboard. He was in all the

battles, Almy, Inkerman, Ballyklaver, Seringapatam, and

Sebastopol."

"And was he killed?" asked the Member for SARK, making as

though he would help ARPACHSHAD with the basket on to his

shoulder again.

"No," said ARPACHSHAD, overlooking the attention—"he

lived to come home; and last week he rode in the Lord Mayor's

coach through the streets of London, with all his medals on.

Five shillings for the day, and a good blow-out, presided over

by Mr. AUGUSTIN HARRIS, in his Sheriff's Cloak and Chain at the

'Plough-and-Thunder,' in the Barbican."

HARTINGTON came down to see us to-day. Mentioned ARPACHSHAD,

and his natural indisposition to hurry himself.

"Why should he?" asked HARTINGTON, yawning, as he leaned

over the fence. "What's the use, as Whosthis says, of ever

climbing up the climbing wave? I can't understand how you

fellows go about here with your shirt-sleeves turned up,

bustling along as if you hadn't a minute to spare. It's just

the same in the House; bustle everywhere; everybody straining

and pushing—everybody but me."

"Well," said SARK, "but you've been up in Scotland, making

quite a lot of speeches. Just as if you were Mr. G.

himself."

"Yes," said HARTINGTON, looking admiringly at ARPACHSHAD,

who had taken off his coat, and was carefully folding it up,

preparatory to overtaking a snail, whose upward march on a

peach-tree his keen eye had noted; "but that wasn't my fault. I

was dragged into it against my will. It came about this way.

Months ago, when Mr. G.'s tour was settled, they said nothing

would do but that I must follow him over the same ground,

speech by speech. If it had been to take place in the next day

or two, or in the next week, I would have plumply said No. But,

you see, it was a long way off. No one could say what might not

happen in the interval. If I'd said No, they would have worried

me week after week. If I said Yes, at least I wouldn't be bored

on the matter for a month or two. So I consented, and, when the

time came, I had to put in an appearance. But I mean to cut the

whole business. Shall take a Garden, like you and SARK, only it

shall be a place to lounge in, not to work in. Should like to

have a fellow like your ARPACHSHAD; soothing and comforting to

see him going about his work."

"I suppose you'll take a partner?" I asked. "Hope you'll get

one more satisfactory than SARK has proved."

HARTINGTON blushed a rosy red at this reference to a

partner. Didn't know he was so sensitive on account of SARK;

abruptly changed subject.

"Fact is, TOBY," he said, "I hate politics; always been

dragged into them by one man or another. First it was BRIGHT;

then Mr. G.; now the MARKISS is always at me, making out that

chaos will come if I don't stick at my place in the House

during the Session, and occasionally go about country making

speeches in the recess. Wouldn't mind the House if seats were

more comfortable. Can sleep there pretty well for twenty

minutes before dinner; but nothing to rest your head against;

back falls your head; off goes your hat; and then those Radical

fellows grin. I could stand politics better if Front Opposition

Bench or Treasury Bench were constructed on principle of family

pews in country churches. Get a decent quiet corner, and there

you are. In any new Reformed Parliament hope they'll think of

it; though it doesn't matter much to me. I'm going to cut it.

Done my share; been abused now all round the Party circle.

Conservatives, Whigs, Liberals, Radicals, Irish Members, Scotch

and Welsh, each alternately have praised and belaboured me. My

old enemies now my closest friends. Old friends look at me

askance. It's a poor business. I never liked it, never had

anything to get out of it, and you'll see presently that I'll

give it up. Don't you suppose, TOBY my boy, that you shall keep

the monopoly of retirement. I'll find a partner, peradventure

an ARPACHSHAD, and we'll all live happily for the rest of our

life."

With his right hand thrust in his trouser-pocket, his left

swinging loosely at his side, and his hat low over his brow,

HARTINGTON lounged off till his tall figure was lost in the

gloaming.

"That's the man for my money," said ARPACHSHAD,

looking with growing discontent at the Member for SARK, who,

with the only blade left in his tortoiseshell-handled penknife,

was diligently digging weeds out of the walk.

In the Club Smoking-Room.

"Lux Mundi," said somebody, reading aloud the title heading

a lengthy criticism in the Times.

"Don't know so much about that," observed a sporting and

superstitious young man; "but I know that 'Ill luck's

Friday.'"

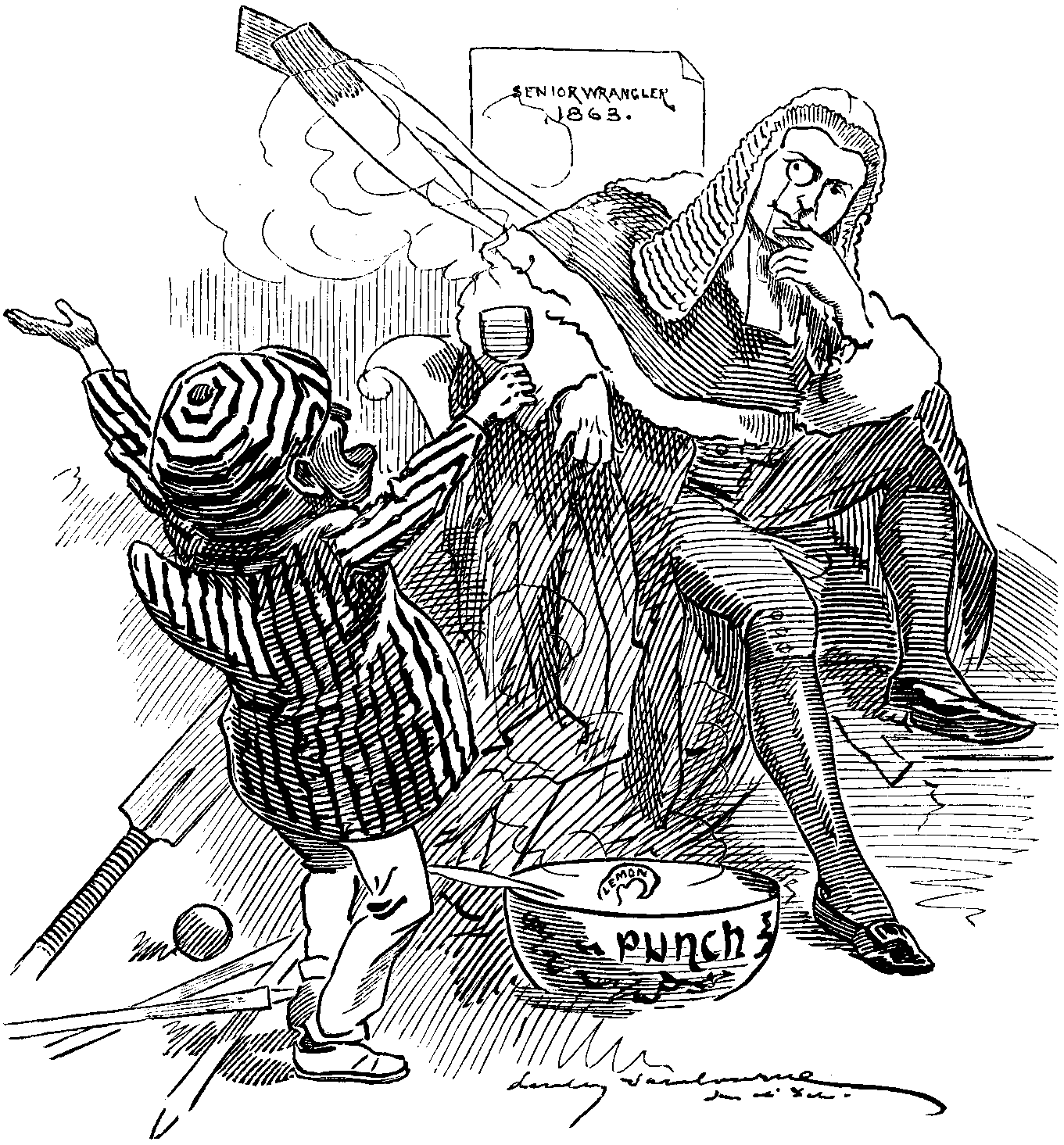

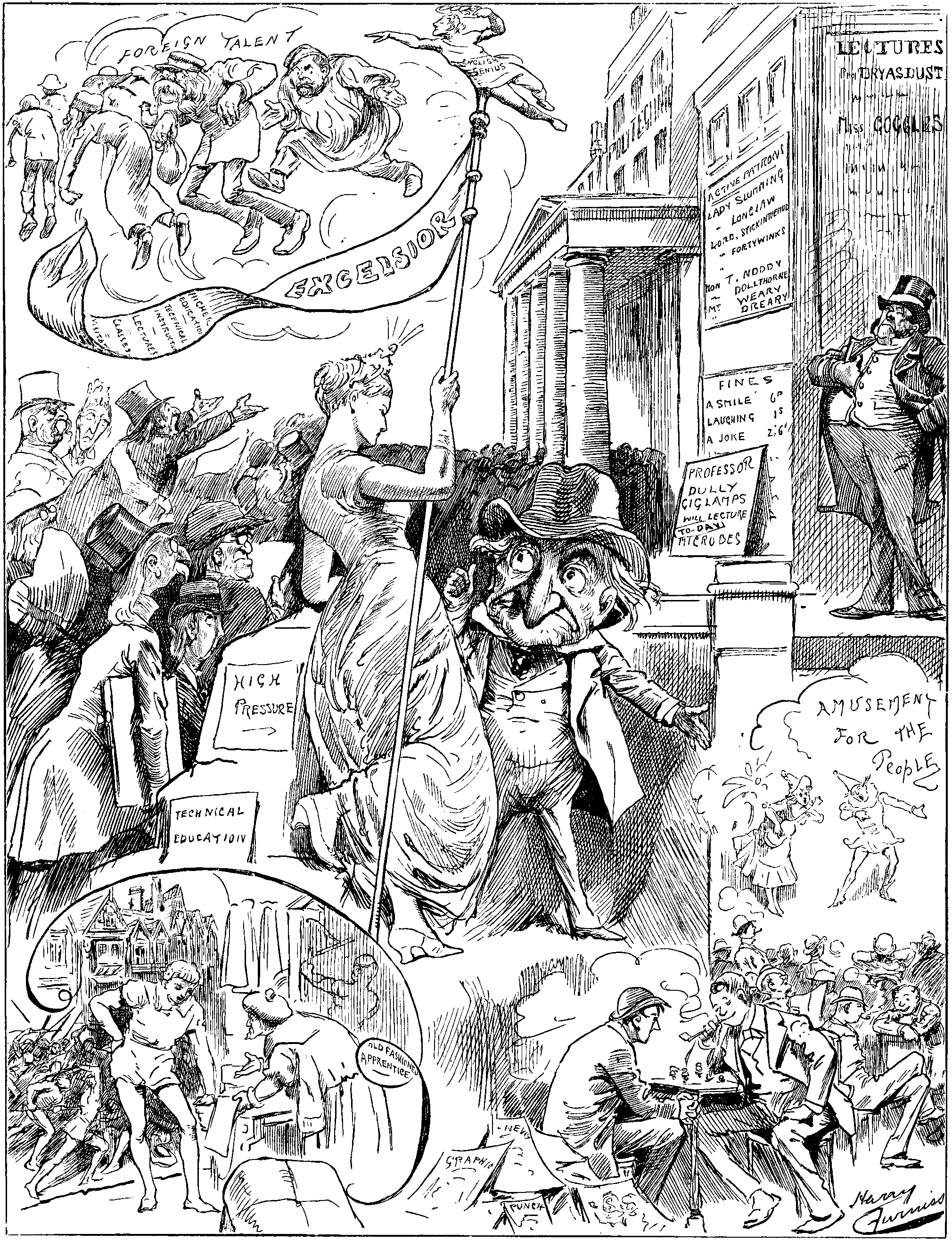

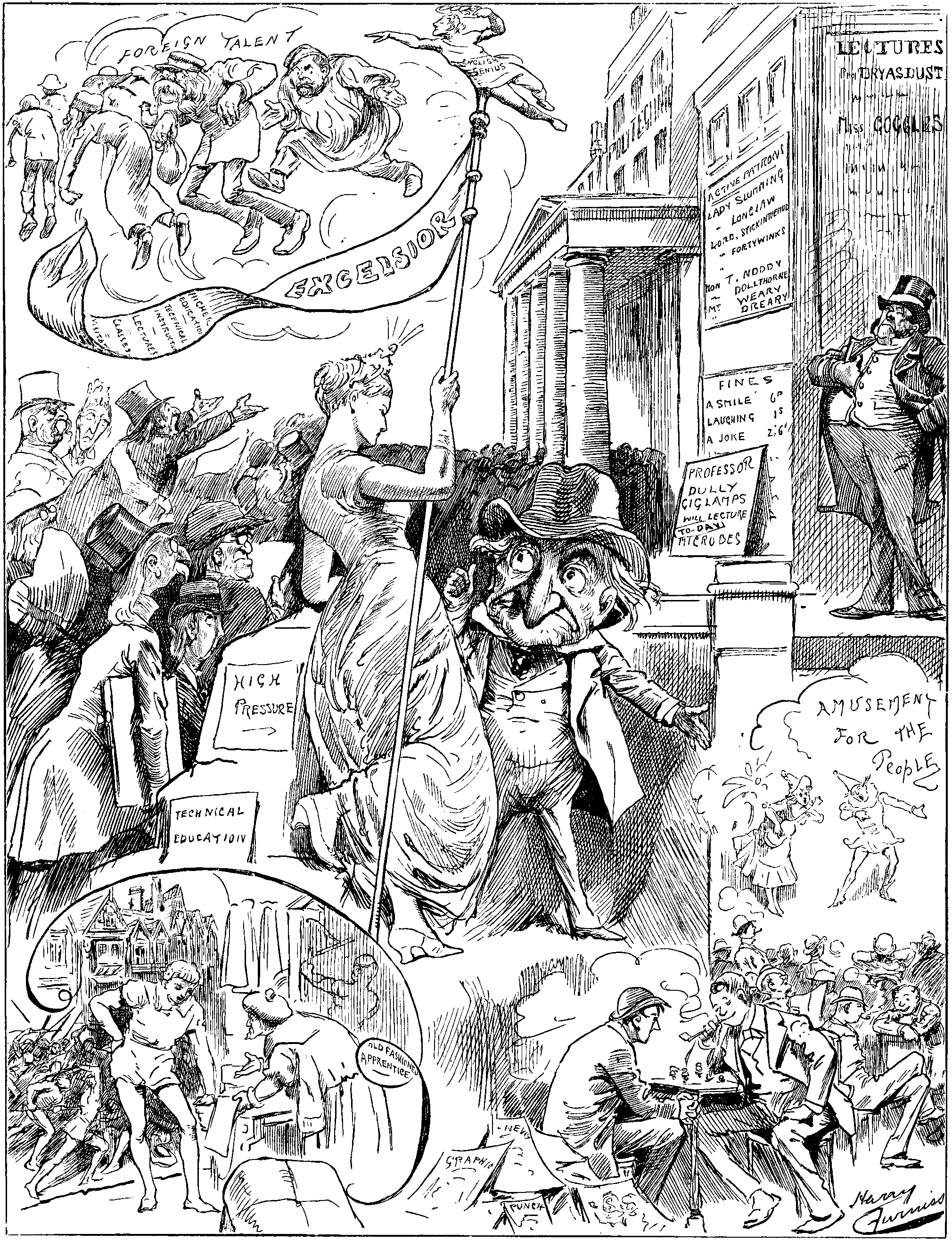

HIGHER EDUCATION.

Mr. Punch. "THAT'S ALL

VERY WELL, BUT IT'S TOO DULL. LET THEM HAVE A LITTLE

SUNSHINE, OR THEY WILL NEVER FOLLOW YOU."

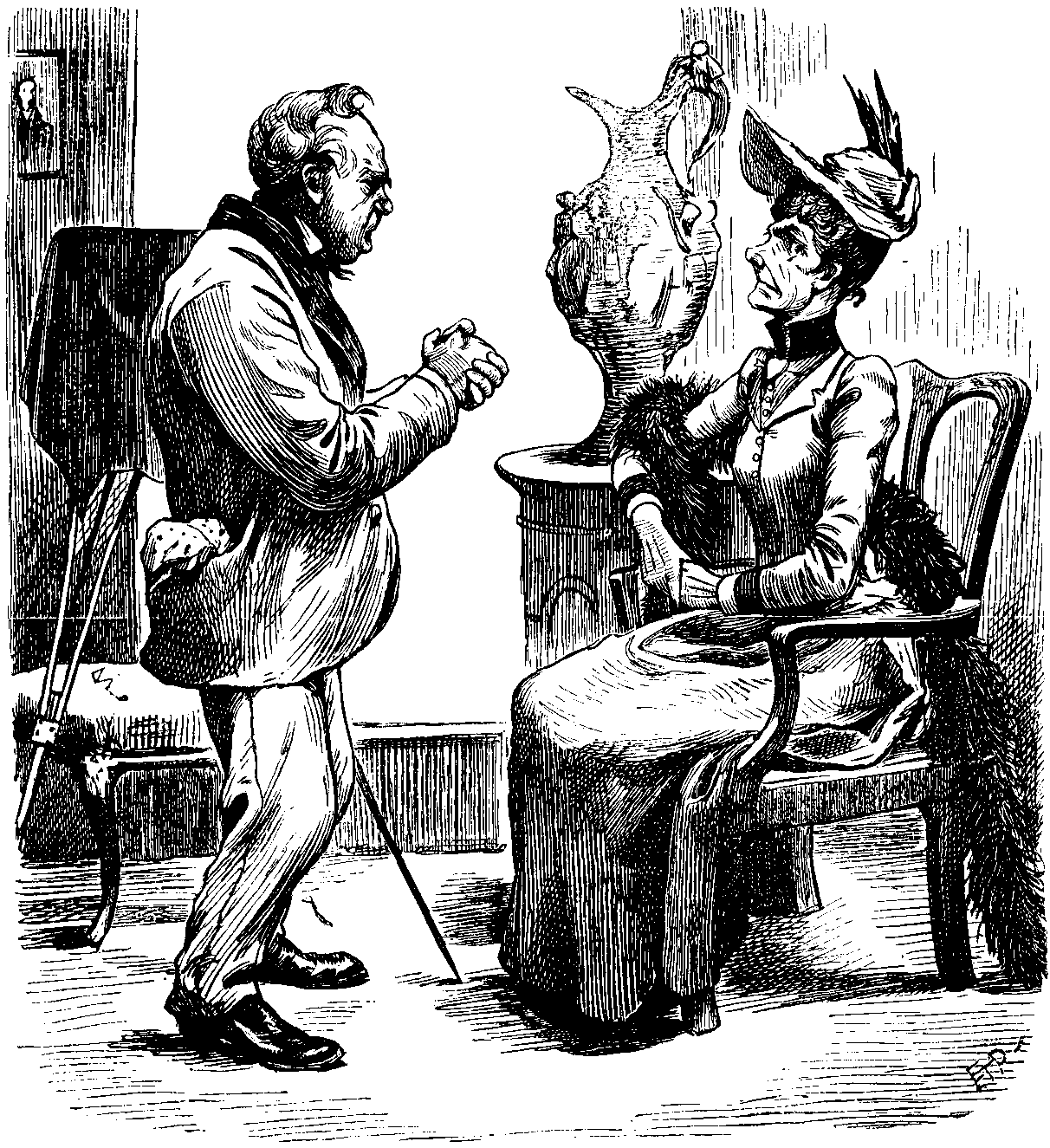

A POSER.

Fair Client. "I'M ALWAYS PHOTOGRAPHED FROM THE

SAME SIDE, BUT I FORGET WHICH!"

Scotch Photographer (reflectively). "WELL,

IT'LL NO BE THIS SIDE, I'M THINKIN'. MAYBE IT'S

T'ITHER!"

PARS ABOUT PICTURES.

Yes, quite so. It's a very good excuse! Whenever I do not

turn up when I am expected, my children say, "Pa's about

pictures." It's just the same as a doctor, when he forgets to

keep an appointment, says, "he has unexpectedly been called

out." Yah! I'd call some of 'em out if I had the chance.

I took French leave the other day, and went to the French

Gallery, expecting to see sketches in French chalk, or studies

in French grey. Nothing of the kind! Mr. WALLIS will have his

little joke. The main part of the exhibition is essentially

English, and so I found my Parisian accent was entirely thrown

away. If it had only been Scotch, I could have said something

about the "Scots wha hae wi' WALLIS," but I didn't have even

that chance. Too bad, though, the show is a good one. "English,

you know, quite English." Lots of good landscapes by LEADER,

bright, fresh, breezy. Young painters should "follow their

Leader," and they can't go very far wrong. I would write a

leader on the subject, and introduce something about the

land-scape-goat, only I know it would be cut out. Being very

busy, sent Young Par to see Miss CHARLOTTE ROBINSON's

Exhibition of Screens. He behaved badly. Instead of looking at

matters in a serious light, he seemed to look upon the whole

affair as a "screening farce," and began to sing—

Here screens of all kinds you may see,

Designed most ar-tist-tic-a-lee,

In exquisite va-ri-e-tee,

By clever CHARLOTTE ROBINSON!

They'll screen you from the bitter breeze,

They'll screen you when you take your teas,

They'll screen you when you flirt with

shes—

Delightful CHARLOTTE ROBINSON!

He then folded his arms, and began to sing, "with my

riddle-ol, de riddle-ol, de ri, de O," danced a hornpipe all

over the place, broke several valuable pieces of furniture, and

was removed in charge of the police. And this is the boy that

was to be a comfort to me in my old age!

Yours parabolically, OLD PAR.

Novel praise from the D.T. for the Lord Mayor's Show,

during a pause for lunch:—"It is so quaint, so bright, so

thoroughly un-English." The Lord Mayor's Show "So Un-English,

you know"! Then, indeed have we arrived at the end of the

ancient al-fresco spectacle.

IN A HOLE.

(Brief Imperial Tragi-Comedy, in Two Acts, in Active

Rehearsal.)

["Well, if it comes to fighting, we should be just in a

hole."—A Linesman's Opinion of the New Rifle, from

Conversation in Daily Paper.]

ACT I.

SCENE—A Public Place in Time of Peace.

Mrs. Britannia (receiving a highly finished and

improved newly constructed scientific weapon from cautious and

circumspect Head of Department). And so this is the new

Magazine Rifle?

Head of Department (in a tone of quiet and

self-satisfied triumph). It is, Madam.

Mrs. Britannia. And I may take your word for it, that

it is a weapon I can with confidence place in the hands of my

soldiers.

Head of Department. You may, Madam. Excellent as has

been all the work turned out by the Department I have the

honour to represent, I think I may fairly claim this as our

greatest achievement. No less than nine firms have been

employed in its construction, and I am proud to say that in one

of the principal portions of its intricate mechanism, fully

seven-and-thirty different parts, united by microscopic screws,

are employed in the adjustment. But allow me to explain.

[Does so, giving an elaborate and confusing account of the

construction, showing that, without the greatest care, and

strictest attention to a series of minute precautions on the

part of the soldier, the weapon is likely to get suddenly out

of order, and prove worse than useless in action. This,

however, he artfully glides over in his description, minimising

all its possible defects, and finally insisting that no power

in Europe has turned out such a handy, powerful, and

serviceable rifle.

Mrs. Britannia. Ah, well, I don't profess to

understand the practical working of the weapon. But I have

trusted you implicitly to provide me with a good one, and this

being, as you tell me, what I want, I herewith place it the

hands of my Army. (Presents the rifle to TOMMY ATKINS.)

Here, ATKINS, take your rifle, and I hope you'll know how to

use it.

Tommy Atkins (with a broad grin). Thank'ee,

Ma'am. I hope I shall, for I shall be in a precious 'ole if I

don't.

[Flourish of newspaper articles, general

congratulatory chorus on all sides, as Act-drop

descends.

ACT II.

A Battle-field in time of War. Enter TOMMY ATKINS

with his rifle. In the interval, since the close of the

last Act, he is supposed to have been thoroughly instructed

in its proper use, and, though on one or two occasions,

owing to disregard of some trifling precaution, he has

found it "jam," still, in the leisure of the

practice-field, he has been generally able to get it right

again, and put it in workable order. He is now hurrying

along in all the excitement of battle, and in face of the

enemy, of whom a batch appear on the horizon in front of

him, when the word is given to "fire."

Tommy Atkins (endeavours to execute the order, but

he finds something "stuck," and his rifle refuses to go

off.) Dang it! What's the matter with the beastly thing!

It's that there bolt that's caught agin' (thumps it

furiously in his excitement and makes matters worse.) Dang

the blooming thing; I can't make it go. (Vainly endeavours

to recall some directions, committed in calmer moments, to

memory.) Drop the bolt? No! that ain't it. Loose this 'ere

pin (tugs frantically at a portion of the mechanism.)

'Ang me if I can make it go! (Removes a pin which suddenly

releases the magazine), well, I've done it now and no

mistake. Might as well send one to fight with a broomstick.

(A shell explodes just behind him.) Well, I am in a

'ole and no mistake. [Battle proceeds with results as

Act-drop falls.

OLD FRENCH SAW RE-SET.—From The Standard,

November 14:—

"The duel between M. DÉROULÈDE and M. LAGUERRE occurred

yesterday morning in the neighbourhood of Charleroi, in

Belgium. Four shots were exchanged without any result. On

returning to Charleroi the combatants and their seconds

were arrested."

"C'est Laguerre, mais ce n'est pas

magnifique."

NOTICE—Rejected Communications or Contributions,

whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any

description, will in no case be returned, not even when

accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or

Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.