Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Volume 100, April 11, 1891

Author: Various

Release date: August 25, 2004 [eBook #13283]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Malcolm Farmer, William Flis, and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team.

[The MS. of this remarkable novel was tied round with scarlet ribbons, and arrived in a case which had been once used for the packing of bottles of rum, or some other potent spirit. It is dedicated in highly uncomplimentary terms to "Messieurs les Marronneurs glacés de Paris." With it came a most extraordinary letter, from which we make, without permission, the following startling extracts. "Ha! Ha! likewise Fe Fo Fum. I smell blood, galloping, panting, whirling, hurling, throbbing, maddened blood. My brain is on fire, my pen is a flash of lightning. I see stars, three stars, that is to say, one of the best brands plucked from the burning. I'm going to make your flesh creep. I'll give you fits, paralytic fits, epileptic fits, and fits of hysteria, all at the same time. Have I ever been in Paris? Never. Do I know the taste of absinthe? How dare you ask me such a question? Am I a woman? Ask me another. Ugh! it's coming, the demon is upon me. I must write three murderous volumes. I must, I must! What was that shriek? and that? and that? Unhand me, snakes! Oh!!!!—M.M."]

I was asleep and dreaming—dreaming dreadful, horrible, soul-shattering dreams—dreams that flung me head-first out of bed, and then flung me back into bed off the uncarpeted floor of my chamber. But I did not wake—why should I?—it was unnecessary—I wanted to dream—I had to dream and therefore I dreamt. I was walking home from a cheap restaurant in one of the poorer quarters of Paris. "Poorer quarters" is a nice vague term. There are many poorer quarters in a large city. This was one of them. Let that suffice to the critical pedants who clamour for accuracy and local colour. Accuracy! pah! Shall the soaring soul of a three-volumer be restrained by the debasing fetters of a grovelling exactitude? Never! I will tell you what. If I choose, I who speak to you, moi qui vous parle, the Seine shall run red with the blood of murdered priests, and there shall be a tide in it where no tide ever was before, close to Paris itself, the home of the Marrons Glacés, and into the river I shall plunge a corpse with upturned face and glassy, staring, haunting, dreadful eyes, and the tide shall turn, the tide that never was on earth, or sky, or sea, it shall turn in my second volume for one night only, and carry the corpse of my victim back, back, back under bridges innumerable, back into the heart of Paris. Dreadful, isn't it? Allons, mon ami. Qu'est-ce-qu'il-y-a. Je ne sais quoi. Mon Dieu! There's idiomatic French for you, all sprinkled out of a cayenne pepper-pot to make the local colour hot and strong. Bah! let us return to our muttons!

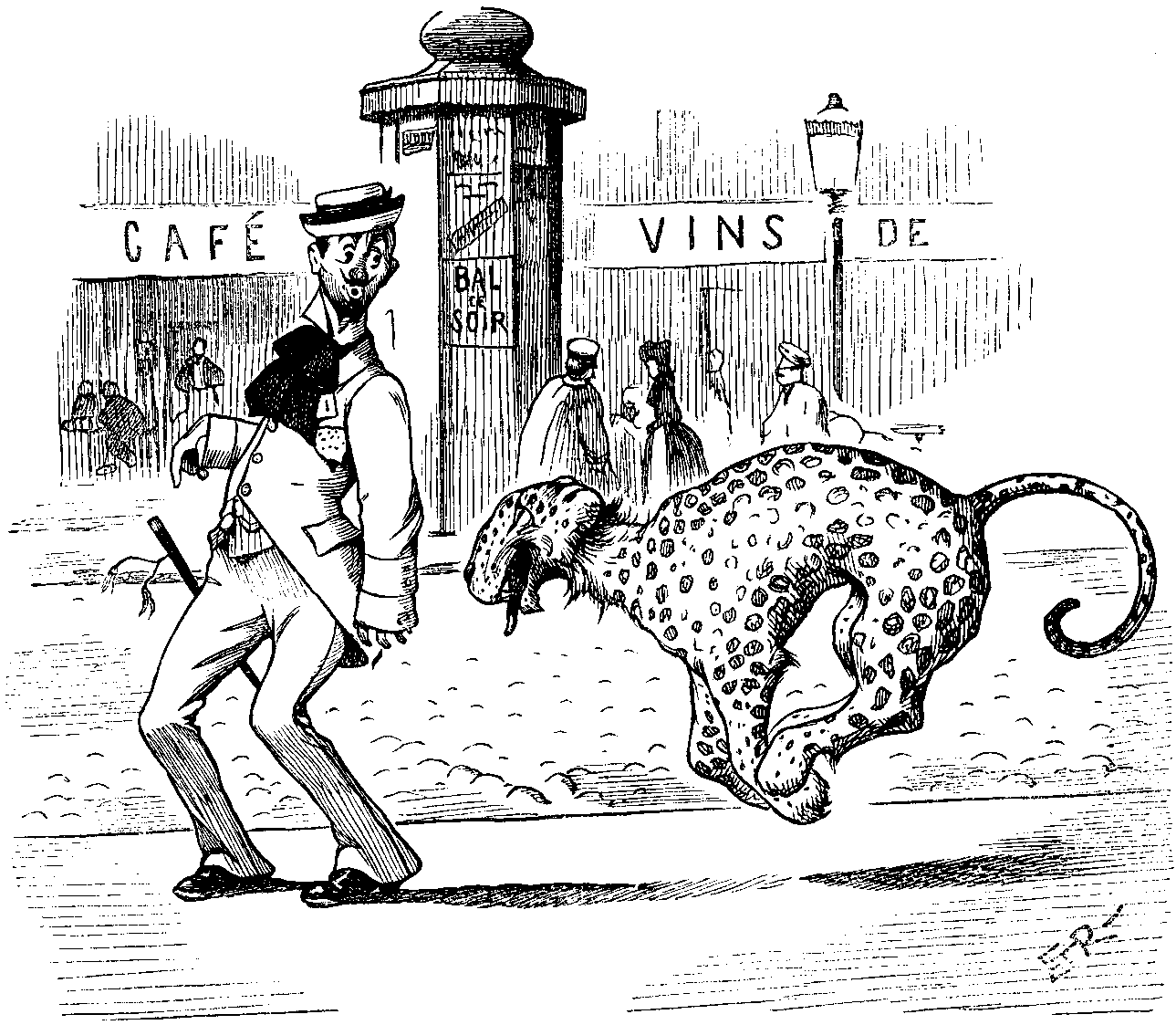

What was that? Something yellow, and spotted—something sinuous and lithe, with crawling, catlike motion. No, no! Yes, yes!! A leopard of the forest had issued from a side-street, a cul de sac, as the frivolous sons of Paris, the Queen of Vice, call it. It was moving with me, stopping when I stopped, galloping when I galloped, turning somersaults when I turned them. And then it spoke to me—spoke, yes, spoke, this thing of the desert—this wild phantasm of a brain distraught by over-indulgence in marrons glacés, the curse of ma patrie, and its speech was as the scent of scarlet poppies, plucked from the grave of a discarded mistress.

"Thou shalt write," it said, "for it is thine to reform the world." I shuddered. The conversational "thou" is fearful at all times; but, ah, how true to nature, even the nature of a leopard of the forest. The beast continued—"But thou shalt write in English."

"Spare me!" I ventured to interpose.

"In English," it went on, inexorably—"in hysterical, sad, mad, bad English. And the tale shall be of France—France, where the ladies always leave the dinner-table before the men. Note this, and use it at page ninety of thy first volume. And thy French shall be worse than thy English, for thou shalt speak of a frissonement, and thy friends shall say, "Nous blaguons le chose."

"Stop!" I cried, in despair, "stop, fiend!—this is too much!" I sprang at the monster, and seized it by the throat. Our eyes, peering into each other's, seemed to ravage out, as by fire, the secrets hidden in our hearts. My blood hurled itself through my veins. There was something clamorous and wild in it. Then I fell prone on the ground, and remembered that I had eaten one marron for dinner. This explained everything, and I remembered no more till I came to myself, and found the divisional surgeon busily engaged upon me with a pompe d'estomac.

My father, M. le Duc DI SPEPSION, belonged to one of the oldest French families. He had many old French customs, amongst others that of brushing his bearded lips against my cheek. He was a stern man, with a severe habit of addressing me as "Mon fils." Generally he disapproved of my proceedings, which was, perhaps, not unnatural, taking all the circumstances of the case into consideration. Why have I mentioned him? I know not, save that even now, degraded as I am, memories of better things sometimes steal over me like the solemn sound of church-bells pealing in a cathedral belfry. But I have done with home, with father, with patriotism, with claret, with walnuts, and with all simple pleasures. Ça va sans dire. They talk to me of Good, and Nature. The words are meaningless to me. Are there realities behind these words—realities that can touch the heart of a confirmed marroneur? Cold and pitiless, Nature sits aloft like a mathematician, with his balance regulating the storm-pulses of this troubled world. Bah! I fling myself in her teeth. I brazen it out. She quails. For, since the accursed food passed my lips, the strength of a million demons is in me. I am pitiless. I laugh to think of the fool I once was in the days when I fed myself on Baba au Rhum, and other innocent dishes. Now I have knowledge. I am my own good. I glance haughtily into—[Ten rhapsodical pages omitted.—ED. Punch.] But there came into my life a false priest, who was like the ghost of a fair lost god—and because he was a fair lost, the cabmen loved him not—and he had to die, and lie in the Morgue—the Morgue where murdered men and women love to dwell—and thus he should discover the Eternal Secret!

Again—again—again! The moon rose, shimmering like a Marron Glacé over Paris. Oh! Paris, beauteous city of the lost. Surely in Babylon or in Nineveh, where SEMIRAMIS of old queened it over men, never was such madness—madness did I say? Why? What did I mean? Tush! the struggle is over, and I am calm again, though my blood still hums tumultuously. The world is very evil. My father died choked by a marron. I, too, am dead—I who have written this rubbish—I am dead, and sometimes, as I walk, my loved one glides before me in aërial phantom shape, as on page 4, Vol. II. But I am dead—dead and buried—and over my grave an avenue of gigantic chestnuts reminds the passer-by of my fate: and on my tombstone it is written, "Here lies one who danced a cancan and ate marrons glacés all day. Be warned!" THE END.

QUITE EXCEPTIONAL THEATRICAL NEWS.—Next Thursday at the Vaudeville, the Press and the usual Free-Admissionaries will be let in for Money.

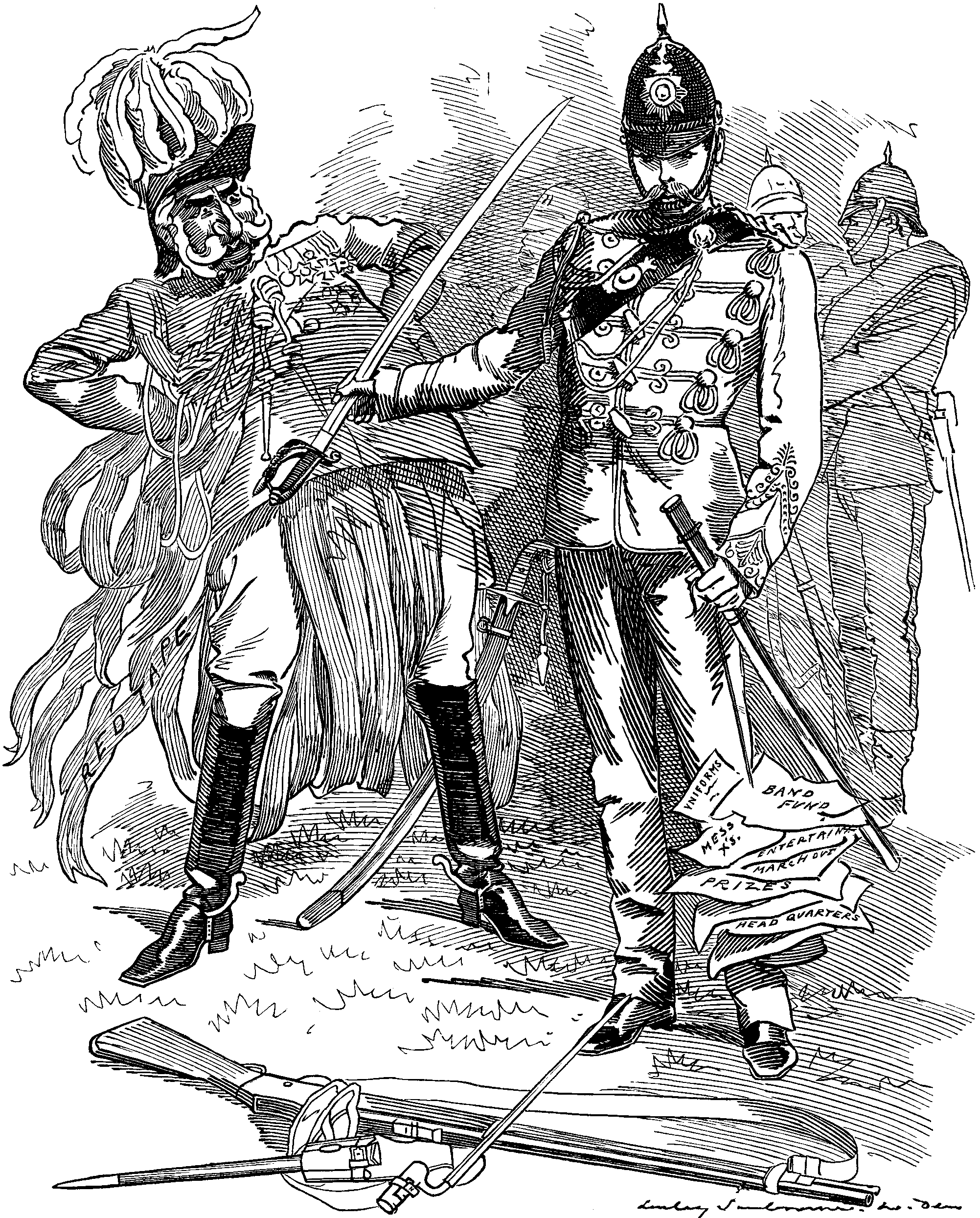

"The root of Volunteer inefficiency is to be ascribed to the Volunteer officer. The men are such as their officers make them ... The force is 1,100 officers short of its proper complement."—Times.

General Redtape (of the Intelligence Department, W.O.) "WHAT! GOING TO RESIGN!"

Volunteer Officer. "YES. WHY SHOULD I ONLY GET YOUR KICKS FOR MY HALFPENCE?"

Yes, take back the sword! Though the Times may expostulate,

Tired am I wholly of worry and snubs.

You'll find, my fine friend, what your folly has cost you, late,

Henceforth for me the calm comfort of Clubs!

To lounge on a cushion and hear the balls rattle

'Midst smoke-fumes, and sips on the field of green cloth,

Is better than leading slow troops to sham battle,

In stupid conditions that rouse a man's wrath.

Commissions, they say, go a-begging. Precisely!

Incapables take them, but capables shy.

For twenty-one years you have harried us nicely.

And now, like the rest, we're on Strike, Sir. And why?

The game, you old fossil, is not worth the candle,

Your kicks for my halfpence? The bargain's too bad!

If you want bogus leaders sham soldiers to handle,

You'll now have to take duffers, deadheads, and cads!

The Times wisely says you should make it attractive,

This Volunteer business. But that's not your game.

You're actively snubby, or coldly inactive:

We pay, and you pooh-pooh! 'Tis always the same.

We do not mind giving our time and our money,

Or facing March blasts, or the floods of July;

But till nettles bear grapes, Sir, or wasps yield us honey,

You won't get snubbed men to pay up and look spry.

The "multiplication of camps and manoeuvres"?

All right! Let us learn in a soldierlike school;

But what is the good of your Bisleys and Dovers.

If the whole game resolves into playing the fool?

To play that game longer and pay for it too, Sir,

Won't suit me at all. I'm disgusted and bored.

Your kicks for my halfpence? No, no, it won't do, Sir!

And therefore, old Tapenoddle—take back the sword!

"I'M WRITING TO MRS. MONTAGUE, GEORGIE,—THAT PRETTY LADY YOU USED TO TAKE TO SEE YOUR PIGS. HAVEN'T YOU SOME NICE MESSAGE TO SEND HER?"

"YES, MUMMIE; GIVE HER MY LOVE, AND SAY I NEVER LOOK AT A LITTLE BLACK PIG NOW WITHOUT THINKING OF HER!"

March 11.—I shall have to be pretty careful in my speech to the Council. Must butter up Billsbury like fun. How would this do? "I am young, Gentlemen, but I should have studied the political history of my country to little purpose if I did not know that, up to the time of the last election, the vote of Billsbury was always cast on the side of enlightenment, and Constitutional progress. The rash and foolish experiments of those who sought to impair the glorious fabric of our laws and our Constitution found no favour in Billsbury. It was not your fault, I know, that this state of things has not been maintained, and that Billsbury is now groaning under the heavy burden of a distasteful representation. Far be it from me to say one word personally against the present Member for Billsbury. This is a political fight, and it is because his political opinions are mistaken that you have decided to attack him"—&c., &c., &c. Must throw in something about Conservatives being the true friends of working-men. CHUBSON is not an Eight Hours' man, so I can go a long way. What shall I say next? Church and State, of course, Ireland pacified and contented, glorious financial successes of present Government, steady removal of all legitimate grievances, and triumphs of our diplomacy in all parts of the world. Shall have to say a good word for Liberal-Unionists. TOLLAND says there are about thirty of them, all very touchy. Must try to work in the story of the boy and the plum-cake. It made them scream at the Primrose League meeting at Crowdale.

By the way, Uncle HENRY said, "What about the Bar?" I told him I meant to keep on working at it—which won't be difficult if I don't get more work. I got just two Statements of Claim, and a Motion before a Judge in Chambers, all last year, the third year after my call. Sleepy. To bed.

March 12, "George Hotel," Billsbury.—Left London by 2.15 to-day, and got to Billsbury at 5.30. TOLLAND met me at the station with half a dozen other "leaders of the Party." One was Colonel CHORKLE, a Volunteer Colonel; another was Alderman MOFFATT, a Scotchman with a very broad dialect. Then there was JERRAM, the Editor of the Billsbury Standard, "the organ of the Party in Billsbury," so TOLLAND said, and a couple of others. I was introduced to them all, and forgot which was which immediately afterwards, which was most embarrassing, as I had to address them all as "you," a want of distinction which I am afraid they felt. Tipped two porters, who carried my bag and rug, a shilling each. They looked knowing, but old TOLLAND had hinted that the other side had got a character for meanness of which we could take a perfectly proper advantage without in any way infringing the Corrupt Practices Act. Must look up that Act. It may be a help. From the station we went straight to the "George." There I was introduced to half a dozen more leaders of the Party. Can't remember one of them except BLISSOP, the Secretary of the Association, a chap about my own age, who told me his brother remembered me at Oxford. There was a fellow of that name, I think, who came up in my year, a scrubby-faced reading man. We made hay in his room after a Torpid "rag," which he didn't like. Hope it isn't the same. I said I remembered him well. Dined with TOLLAND; nobody but leaders of the Party present, all as serious as judges, and full of importance. CHORKLE, who drops his "h's" frightfully, asked me "'ow long it would be afore a General Election," and seemed rather surprised when I said I had no information on the matter.

The meeting of the Council came off in the large hall of the Billsbury Beaconsfield Club. TOLLAND was in the chair, and made a long speech in introducing me. I didn't take in a word of it, as I was repeating my peroration to myself all the time. My speech went off pretty well, except that I got mixed up in the middle, and forgot that blessed story. However, when I got into the buttering part, it took them by storm. I warmed old GLADSTONE up to-rights, and asked them to contrast the state of England now with what it was when he was in power. "Hyperion to a Satyr," I said. Colonel CHORKLE, in proposing afterwards that I was a fit and proper person to represent Billsbury, said, "Mr. PATTLE's able and convincing speech proves 'im not only a master of English, but a consummate orator, able to wield the harmoury" (why he put the "h" there I don't know) "of wit and sarcasm like a master. I'm not given to boasting," he continued. "I never indulge in badinage" (query, braggadocio?); "but, with such a Candidate, we must win." JERRAM seconded the resolution, which was carried nem. con. Must get local newspapers, to show to mother. She'll like that. Shall go back to London to-morrow.

"FORTNIGHTLY" V. SO-CALLED "NINETEENTH CENTURY."—Change of Author's name. Mr. FREDERIC HARRISON to be known in future as "FREDERIC HARRASIN' KNOWLES."

The Room, with the cheap Art-furniture as before—except that the candles on the Christmas-tree have guttered down and appear to have been lately blown out. The cotton-wool frogs and the chenille monkeys are disarranged, and there are walking things on the sofa. NORA alone.

Nora (putting on a cloak and taking it off again). Bother KROGSTAD! There, I won't think of him. I'll only think of the costume ball at Consul STENBORG's, over-head, to-night, where I am to dance the Tarantella all alone, dressed as a Capri fisher-girl. It struck TORVALD that, as I am a matron with three children, my performance might amuse the Consul's guests, and, at the same time, increase his connection at the Bank. TORVALD is so practical. (To Mrs. LINDEN, who comes in with a large cardboard box.) Ah, CHRISTINA, so you have brought in my old costume? Would you mind, as my husband's new Cashier, just doing up the trimming for me?

Mrs. L. Not at all—is it not part of my regular duties? (Sewing.) Don't you think, NORA, that you see a little too much of Dr. RANK?

Nora. Oh, I couldn't see too much of Dr. RANK! He is so amusing—always talking about his complaints, and heredity, and all sorts of indescribably funny things. Go away now, dear; I hear TORVALD. [Mrs. LINDEN goes. Enter TORVALD from the Manager's room. NORA runs trippingly to him.

Nora (coaxing). Oh, TORVALD, if only you won't dismiss KROGSTAD, you can't think how your little lark would jump about and twitter!

Helmer. The inducement would be stronger but for the fact that, as it is, the little lark is generally engaged in that particular occupation. And I really must get rid of KROGSTAD. If I didn't, people would say I was under the thumb of my little squirrel here, and then KROGSTAD and I knew each other in early youth; and when two people knew each other in early youth—(a short pause)—h'm! Besides, he will address me as, "I say, TORVALD"—which causes me most painful emotion! He is tactless, dishonest, familiar, and morally ruined—altogether not at all the kind of person to be a Cashier in a Bank like mine.

Nora. But he writes in scurrilous papers,—he is on the staff of the Norwegian Punch. If you dismiss him, he may write nasty things about you, as wicked people did about poor dear Papa!

Helmer. Your poor dear Papa was not impeccable—far from it. I am—which makes all the difference. I have here a letter giving KROGSTAD the sack. One of the conveniences of living close to the Bank is, that I can use the housemaids as Bank-messengers. (Goes to door and calls.) ELLEN! (Enter parlourmaid.) Take that letter—there is no answer. (ELLEN takes it and goes.) That's settled—so now, NORA; as I am going to my private room, it will be a capital opportunity for you to practise the tambourine—thump away, little lark, the doors are double! [Nods to her and goes in, shutting door.

Nora (stroking her face). How am I to get out of this mess! (A ring at the Visitors' bell.) Dr. RANK's ring! He shall help me out of it! (Dr. RANK appears in doorway, hanging up his great-coat.) Dear Dr. RANK, how are you? [Takes both his hands.

Rank (sitting down near the stove). I am a miserable, hypochondriacal wretch—that's what I am. And why am I doomed to be dismal? Why? Because my father died of a fit of the blues! Is that fair—I put it to you?

Nora. Do try to be funnier than that! See, I will show you the flesh-coloured silk tights that I am to wear to-night—it will cheer you up. But you must only look at the feet—well, you may look at the rest if you're good. Aren't they lovely? Will they fit me, do you think?

Rank (gloomily). A poor fellow with both feet in the grave is not the best authority on the fit of silk stockings. I shall be food for worms before long—I know I shall!

Nora. You mustn't really be so frivolous! Take that! (She hits him lightly on the ear with the stockings; then hums a little.) I want you to do me a great service, Dr. RANK. (Rolling up stockings,) I always liked you. I love TORVALD most, of course—but, somehow, I'd rather spend my time with you—you are so amusing!

Rank. If I am, can't you guess why? (A short silence.) Because I love you! You can't pretend you didn't know it!

Nora. Perhaps not—but it was really too clumsy of you to mention it just as I was about to ask a favour of you! It was in the worst taste! (With dignity.) You must not imagine because I joke with you about silk stockings, and tell you things I never tell TORVALD, that I am therefore without the most delicate and scrupulous self-respect! I am really quite a good little doll, Dr. RANK, and now—(sits in rocking-chair and smiles)—now I shan't ask you what I was going to! [ELLEN comes in with a card.

Nora (terrified). Oh, my goodness! [Puts it in her pocket.

Dr. Rank. Excuse my easy Norwegian pleasantry—but—h'm—anything disagreeable up?

Nora (to herself). KROGSTAD's card! I must tell another whopper! (To RANK.) No. nothing, only—only my new costume. I want to try it on here. I always do try on my dresses in the drawing-room—it's cosier, you know. So go into TORVALD and amuse him till I'm ready. [RANK goes into HELMER's room, and NORA bolts the door upon him, as KROGSTAD enters from hall in a fur cap.

Krogs. Well, I've got the sack, and so I came to see how you are getting on. I mayn't be a nice man, but—(with feeling)—I have a heart! And, as I don't intend to give up the forged I.O.U. unless I'm taken back, I was afraid you might be contemplating suicide, or something of that kind; and so I called to tell you that, if I were you, I wouldn't. Bad thing for the complexion, suicide, and silly, too, because it wouldn't mend matters in the least. (Kindly.) You must not take this affair too seriously. Mrs. HELMER. Get your husband to settle it amicably by taking me back as Cashier; then I shall soon get the whip-hand of him, and we shall all be as pleasant and comfortable as possible together!

Nora. Not even that prospect can tempt me! Besides, TORVALD wouldn't have you back at any price now!

Krogs. All right, then. I have here a letter, telling your husband all. I will take the liberty of dropping it in the letter-box at your hall-door as I go out. I'll wish you good evening! [He goes out; presently the dull sound of a thick letter dropping into a wire box is heard.

Nora (softly, and hoarsely). He's done it! How am I to prevent TORVALD from seeing it?

Helmer (inside the door, rattling). Hasn't my lark changed its dress yet? (NORA unbolts door.) What—so you are not in fancy costume, after all? (Enters with RANK.) Are there any letters for me in the box there?

Nora (voicelessly). None—not even a postcard! Oh, TORVALD, don't, please, go and look—promise me you won't! I do assure you there isn't a letter! And I've forgotten the Tarantella you taught me—do let's run over it. I'm so afraid of breaking down—promise me not to look at the letter-box. I can't dance unless you do.

Helmer (standing still, on his way to the letter-box). I am a man of strict business habits, and some powers of observation; my little squirrel's assurances that there is nothing in the box, combined with her obvious anxiety that I should not go and see for myself, satisfy me that it is indeed empty, in spite of the fact that I have not invariably found her a strictly truthful little dicky-bird. There—there. (Sits down to piano.) Bang away on your tambourine, little squirrel—dance away, my own lark!

Nora (dancing, with a long gay shawl). Just won't the little squirrel! Faster—faster! Oh, I do feel so gay! We will have some champagne for dinner, won't we, TORVALD? [Dances with more and more abandonment.

Helmer (after addressing frequent remarks in correction). Come, come—not this awful wildness! I don't like to see quite such a larky little lark as this ... Really it is time you stopped!

Nora (her hair coming down as she dances more wildly still, and swings the tambourine). I can't ... I can't! (To herself, as she [pg 173] dances.) I've only thirty-one hours left to be a bird in; and after that—(shuddering)—after that, KROGSTAD will let the cat out of the bag! [Curtain.

N.B.—The final Act,—containing scenes of thrilling and realistic intensity, worked out with a masterly insight and command of psychology, the whole to conclude with a new and original dénoûment—unavoidably postponed to a future number. No money returned.

As I have but a limited holding in the Temple, and, moreover, slept on the evening of the 5th of April at Burmah Gardens, I considered it right and proper to fill in the paper left me by the "Appointed Enumerator" at the latter address. And here I may say that the title of the subordinate officer intrusted with the addition of my household to the compilation of the Census pleased me greatly—"Appointed Enumerator" was distinctly good. I should have been willing (of course for an appropriate honorarium) to have accepted so well-sounding an appointment myself. To continue, the general tone of the instructions "to the Occupier" was excellent. Such words as "erroneous," "specification," and the like, appeared frequently, and must have been pleasant strangers to the householder who was authorised to employ some person other than himself to write, "if unable to do so himself." To be captious, I might have been better pleased had the housemaid who handed me the schedule been spared the smile provoked by finding me addressed by the "Appointed Enumerator" as "Mr. BEEFLESS," instead of "Mr. BRIEFLESS." But this was a small matter.

I need scarcely say that I took infinite pains to fill in my paper accurately. I have great sympathy with the "Census (England and Wales) Act, 1890," and wished, so far as I was personally concerned, to carry out its object to the fullest extent attainable. I had no difficulty about inserting my own "name and surname," and "profession or occupation." I rather hesitated, however, to describe myself as an "employer," because the "examples of the mode of filling-up" rather suggested that domestic servants were not to count, and for the rest my share in the time of PORTINGTON, to say the least, is rather shadowy. For instance, I could hardly fairly suggest that in regard to the services of my excellent and admirable clerk, I am as great an employer of labour as, say, the head of a firm of railway contractors, or the managing director of a cosmopolitan hotel company. Then, although I am distinctly of opinion that I rightly carried out the intentions of the statute by describing myself as "the head of the family," my wife takes an opposite view of the question. In making the other entries, I had no great difficulty. The ages of my domestics, however, caused me some surprise. I had always imagined (and they have given me their faithful and valuable services I am glad to say for a long time) that the years in which they were born varied. But no, I was wrong. I found they were all of the same age—two-and-twenty. To refer to another class of my household—I described my son, SHALLOW NORTH BRIEFLESS (the first is an old family name of forensic celebrity, and the second an appropriate compliment to a distinguished member of the judicial Bench, whose courtesy to the Junior Bar is proverbial) as a "scholar," but rejected his (SHALLOW's) suggestion that I should add to the description of his brother (one of my younger sons, GEORGE LEWIS VAN TROMP CHESTER MOTE BOLTON BRIEFLESS—I selected his Christian names in anticipated recognition of possible professional favours to be conferred on him in after-life) the words "imbecile from his birth," as frivolous, untrue, and even libellous. We had but one untoward incident. In the early morning of Monday we found in our area a person who had evidently passed the night there in a condition of helpless intoxication. As she could offer no satisfactory explanation of her presence, I handed her over to the police, and entered her on the Census Paper as, "a supposed retired laundress, seemingly living on her own means, and apparently blind from the date of her last drinking-bout." I rejected advisedly her own indistinctly but frequently reiterated assertion that "she was a lady," because I had been warned by "the general instructions" to avoid such "indefinite terms as Esquire or Gentleman."

As I wished to deliver my completed schedule to the "Appointed Enumerator" in person, I desired that he might be shown into my study when he called for the paper.

"Excuse me, Sir," he said, after looking through the document at my request; "but you see there is a fine of a fiver for wilfully giving false information."

"Yes," I returned, somewhat surprised at the suggestion; "and the proposed penalty has rendered me doubly anxious to be absolutely accurate. Do you notice any slip of the pen?"

"Well, Sir," he answered, with some hesitation, "as the young chap who does the boots tells me that he has never heard of you having had a single brief while he's been with you, and that's coming three years, hadn't you better put 'retired' after 'Barrister-at-Law'? It will do no harm, and certingly would be safer!"

Put "retired" after Barrister-at-Law! "Do no harm!" and be "safer!"

I silently intimated by a dignified gesture to the "Appointed Enumerator." that our interview was at an end, and then, taking my walking-stick with me, went in earnest and diligent search of "the young chap who does the boots!"

Pump-Handle Court, April 7, 1891.

The "them" in this adapted quotation must be taken to mean "Burlesques;" and if these gay and lighthearted soldiers continue their histrionics as victoriously as they have done up to now, they will become celebrated as "The Grinny-diers-and-Burlesque-Line-Regiments." Private MCGREEVY, as a cockatoo, capital: his disguise obliterated him, but as Ensign and Lieutenant WAGGIBONE stealthily observed, "What the eye doesn't see, the heart doesn't MCGREEVY for." The music, by the talented descendant of Israel's wise King SOLOMON, was of course good throughout, and in the Cockatoo Duet better than ever. The ladies were exceptionally good. Mrs. CRUTCHLEY defied the omen of her name, which is not suggestive of dancing, and "Jigged away muchly Did Mrs. CRUTCHLEY." The Misses SAVILE CLARKE,—the Savilians among the Military,—were charming. Lieutenant NUGENT is an old hand at this, and his Paul Prior was not a whit behind his former performances. There's one more Guard O, Major RICARDO. He played Crusoe, And well did he do so! Three cheers for everybody! With the Guards' Burlesque, we fear no foe. Chorus, Gentlemen, if you please, "We fear no foe!"

Fifty, not out! A good start beyond doubt,

In a Twenty-four field, Doctor W.G.

And may Ninety-one bring us lots of good fun,

With you at the Wickets for Figures of Three,

To see the Old 'Oss stir in good time to foster

The coming-on "Colts," should give courage to Glo'ster!

The enclosed was cut from The Field of last week:—

R. —— —— WANTS some friend to give him a small BULLDOG with a smile, for a house pet.—To be sent for inspection to, &c.

It is to be hoped that the advertiser will not get an animal that (to quote from Hamlet) "may smile and smile and be a villain!"

Prate not about Fame! I've addressed half the world,

In Court and in cottage, in Castle and slum!

I've been warbled, and chorussed, and tootled, and skirled,

Yet, for kudos, I might just as well have been dumb.

Though familiar to all men, I'm wholly unknown;

You're inclined to pooh-pooh, and to say I am wrong?

Nay, listen, and you my correctness will own:

'Tis I wrote the words of a Popular Song!

NEW AND INTERESTING WORK.—As a companion to Dr. WRIGHT's The Ice Ages in North America and its bearing upon the Antiquity of Man, will shortly appear The Penny-Ice Age in London and its bearing on the Youth of the Metropolis.

An "ill-starred abortion" WEG christened our party;

At present, as JOE hints, that sounds quite ironic.

True, lately our health did appear far from hearty,

But Aston has acted As-tonic!

NOTE FOR CRITICS.—How can any of us expect the truth from a historian who himself tells us that he merely "transcribes from MSS. lying before him!"

WHAT THE ITALIANS SEEM TO WANT IN LOUISIANA.—An unfair field, or no FAVA!

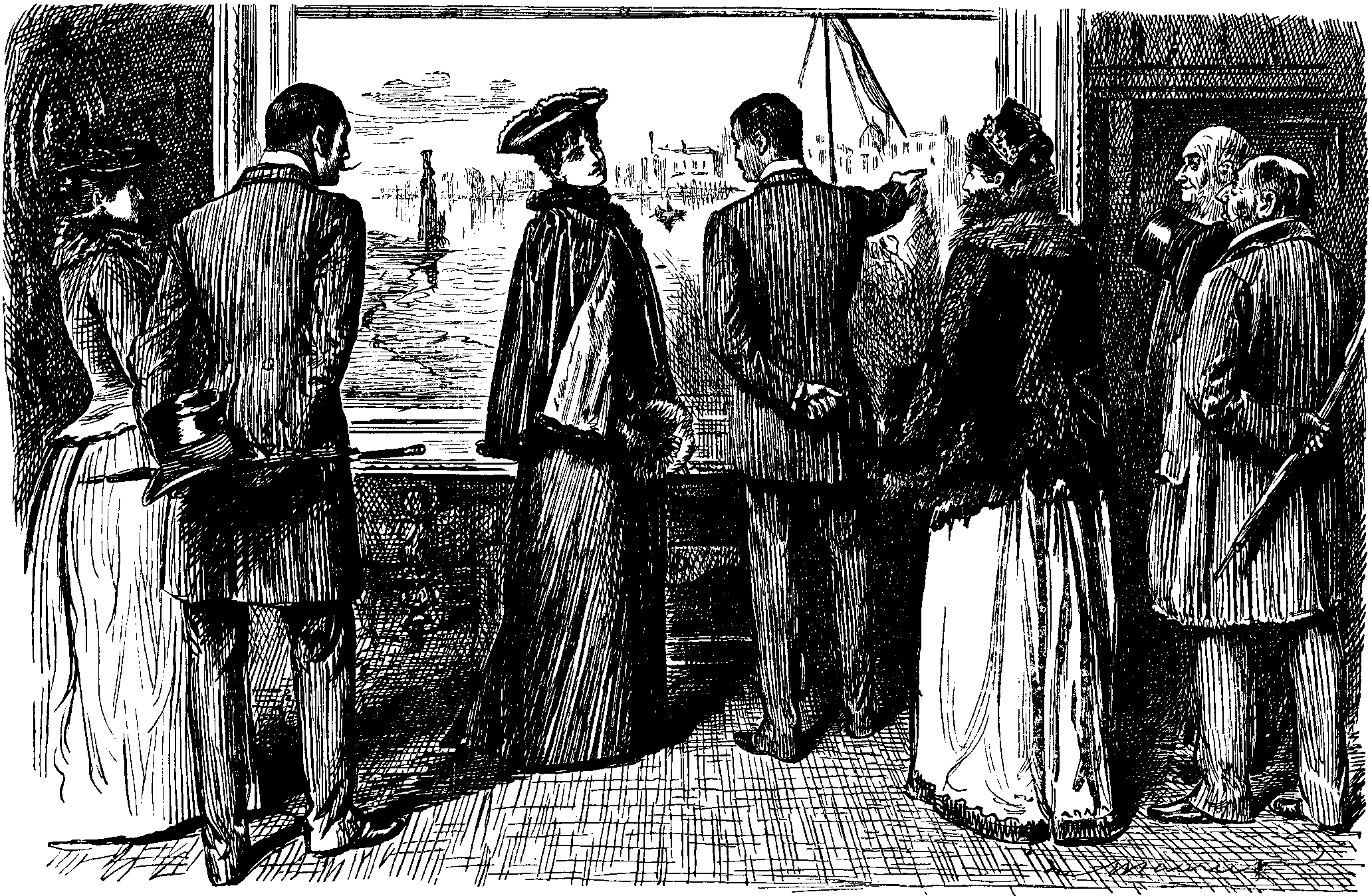

Fair Damsel (to Our Artist, who is explaining the beauties of his Picture). "CHARMING! CHARMING! BUT, OH, MR. FITZMADDER, WHAT A DELIGHTFUL ROOM THIS WOULD BE FOR A DANCE,—WITH THE MUSICIANS IN THE GALLERY, AND ALL THE EASELS AND PICTURES AND THINGS CLEARED AWAY!"

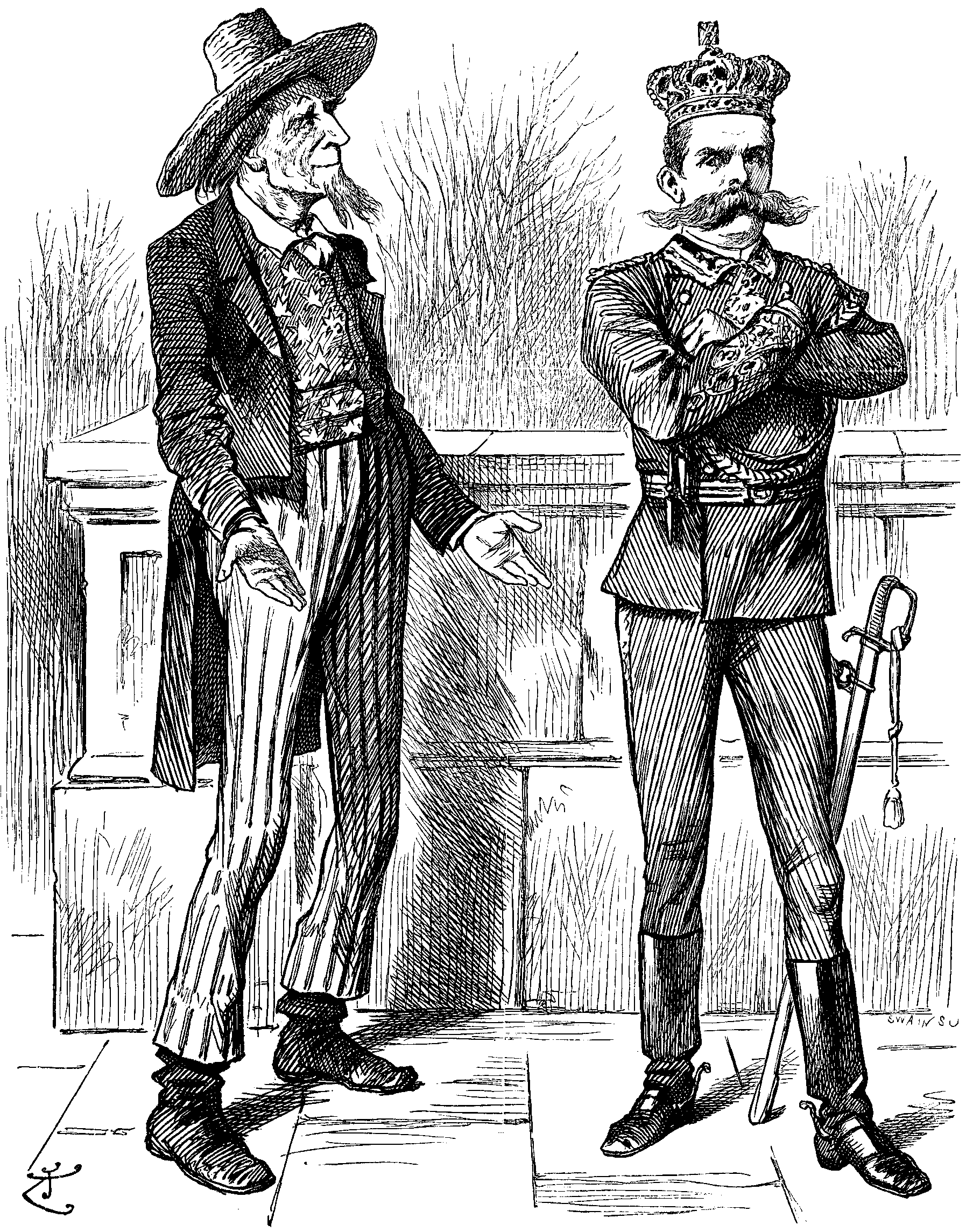

HOSEA BIGLOW speaks up on the situation:—

Here we stan' on the Constitution, by thunder!

State rights won't be hurried by any one's hoofs;

UMBERTO, old hoss, would you like, I wonder,

To 'pologise first, and then bring up yer proofs?

Uncle SAM is free, and he sez, sez he:—

"The Mafia's no more

Right to come to this shore,

No more'n the Molly Maguires," sez he.

Uncle SAM ain't no kind o' bisness with nothin'

Like stabs in the back,—that may do for slaves.

We ain't none riled by their frettin' an' frothin'

Who shriek, in Hitalian, across the waves.

Uncle SAM is free, but he sez, sez he:—

"He will put down his foot

On the right to shoot

As claimed by the Mafia gang!" sez he.

Freedom's keystone is Law, yes; that there's no doubt on,

It's sutthin that's—wha' d'ye call it?—divine,—

The brutes who break it hain't nutthin' to boast on

On your side or mine o' the seethin' brine.

Uncle Sam is free, and he sez, sez he:—

"If assassins gang 'em

I'm game to hang 'em,

An' so git rid on 'em soon," sez he.

'Tis well for sleek cits for to lounge on their soffies,

And chat about "Law and Order," an' sich.

A formula pleasant for them in office,

Home-stayin' idlers, well-guarded rich.

Uncle SAM is free, but he sez, sez he:—

"Whar life's a fight,

Law, based on right,

May need the 'strong arm' of a Man," sez he.

Now don't go to say I'm the friend of force;

Best keep all your spare breath for coolin' your broth;

And when just Law has a fair clar course,

All talk of "wild justice" is frenzy and froth.

Uncle SAM is free, but he sez, sez he:—

"If he gits within hail

Of the Glan-na-Gael,

Or the Mafia either, he shoots," sez he.

This ain't no matter for sauce or swagger—

Too summary judgment both scout, I hope;

Though ef it's a chice betwixt rope and dagger,

I can't help sayin' I prefer the rope.

Uncle SAM is free, and he sez, sez he:—

"At a pinch I'll not flinch

From a touch of Lynch,—

That is—at a very hard pinch!" sez he.

But Lynch Law, UMBERTO, or Secret Society,

Both are bad, though the latter's wust;

We'll soon get shut of either variety,

You and me, UMBERTO, or so I trust.

Uncle SAM is free, but he sez, sez he:—

"Assassination

Won't build a nation,

Nor yet the unlegalised rope," sez he.

Withdraw your Ambassador! Wal, that air summary!

Italian irons so soon git hot!

Ironclads? Sure that's mere militant flummery.

Don't want to rile, but I'll tell you what:

Uncle SAM is free, but he sez, sez he:—

"Let FAVA stay,

Take the Mafia away,

And we'll call it aright square deal!" sez he.

PRESENTED AT COURT.—Acting upon the suggestions made in these columns a week ago, the Author of The Volcano, and the company of the Court Theatre have effected the most valuable alterations in the play of the evening. The Second Act now concludes with the interrupted singing of The Wolf, which brings down the Curtain with a roar of laughter, and the Third Act is also generally improved. Mrs. JOHN WOOD is seen at her best as the interviewing lady-journalist, which is condensing in a sentence a volume of praise. Mr. ARTHUR CECIL, as the Duke, is equally admirable; and Mr. WEEDON GROSSMITH, although scarcely in his element as a Member of Parliament of noble birth, is distinctly amusing. Altogether, The Volcano causes explosions of merriment in all parts of the house, and has entirely escaped the once-impending danger of fizzling out like a damp squib.

[For the first time the sixth column in the Census Schedule is simply headed "Profession or Occupation."]

Oh! I'm a reg'lar rightdown Duke:

The trying part I act and look

Right nobly, so they tell me.

Yet I would have you understand

Why I am thoroughly unmanned

At what of late befell me.

A week or something less ago,

A schedule came to let me know

The Census Day was Sunday.

The many details, one and all,

Must he filled in, and then they'd call

To fetch it on the Monday.

I found it easy to contrive

To answer columns one to five—

I filled them up discreetly;

But when I came to column six

I got into an awful fix,

And lost my head completely.

For "Rank" alas! had disappeared.

I'd never for an instant feared

It wouldn't really be there.

Your "Occupation" you could state,

"Profession," too, you might relate,

But I—a Duke—had neither!

His Grace the Duke of PLAZA-TOR'

Would call himself, I'm pretty sure,

A "public entertainer."

But I and my blue-blooded wife,

We lead a simple blameless life,

No life could well be plainer.

In such a plight what could I do?

I searched the paper through and through,

Each paragraph I read. You'll

Scarce credit it but those who "live

On their own means" had got to give

This statement in the schedule!

I put it, but my ducal pen

I saw distinctly sputtered when

I did so. All of which he

Will please remember when I say

I thought it in a minor way

Unkind of Mr. RITCHIE!

As to the incident which recently appeared in the papers under the head-line "Insulting an Ambassador," our old friend MICKY writes us as follows:—"Be jabers then, ye must know the truth. Me and Count MUNSTER was drivin' together. The Count's every bit a true-born son of Ould Ireland for ever, and descended from the Kings of Munster by both sides, and more betoken wasn't he wearin' an Ulster at the very moment, and isn't he the best of chums with the Dukes of CONNAUGHT and LEINSTER? Any way we were in our baroosh passin' the time o' day to one another as we were drivin' in the Bore, when whack comes a loaf o' bread, shied at our heads by an unknown military blaygaird. It missed me noble friend, the Count, and, as if to give him a lesson in politeness, it just took off the hat of a domestic alongside the coachman on the box. 'Tunder and turf!' says I, preparing to descend, and give the scoundrels a taste of my blackthorn all round. 'Whist! be aisy now, MICKY,' says the Ambassador to me, in what is, betune ourselves, his own native tongue; and with that he picks up the loaf, sniffs at it, makes a wry face ('it's a rye loaf,' says I), and then says he, out loud, with a supercilious look, 'Ill-bred!' Begorra, there was a whoop o' delight went up all round, which same was a sign of their purliteness, as divil a one of the ignoramuses could onderstand a wurrd the Court said in English or German, let alone Irish. 'Goot,' says MUNSTER to me, dropping into his German accent, which, on occasion, comes quite natural to him—the cratur! 'I'll give the loaf to the dog;' and he whistles up the mastiff, own brother to BISMARCK's. 'Eh, MICKY, ye gossoon, isn't the proverb, "Loaf me, loaf my dog"?' Ah! then was cheers for ould Ireland, and a mighty big dhrink entirely we had that same night.

Why tye I about thy wrist,

JULIA, this my silken twist?

For what other reason is't,

But to show (in theorie)

Thou sweet captive art to me;

Which, of course, is fiddlededee!

Runne and aske the nearest Judge,

He will tell thee 'tis pure fudge;

When thou willest, thou mayst trudge;

I'm thy Bondslave, Hymen's pact

Bindeth me in law and fact;

Thou art free in will and act;

'Tis but silke that bindeth thee,

Snap the thread, and thou art free:

But 'tis otherwise with me.

I am bound, and bound fast so

That from thee I cannot go.

(Hah! We'll have this altered, though.

Man must be a wing-clipp'd goose

If he bows to Hymen's noose,—

Heads you winne, and tails I lose!)

Editor to Eminent Writer.—Review promises to be deadly slow next month. Can you do something slashing for us? Pitch into somebody or other—you know the style.

Eminent Writer to Editor.—Happy to oblige. Got old article handy advocating cession of Canada and India to the French. Never wrote anything more ripping. Pitches into everybody. Touching it up, and will let you have it in two days. By the bye, telegraph people put a K to my Christian name. Tell them not to do it again.

Editor to Eminent Writer (a week later).—Sorry about the K. Got your article. Not quite what I wanted. Style all right, but arguments idiotic. Can't you take the other side? Much more popular.

Eminent Writer to Editor.—Idea insulting. Any more telegrams of that sort, and I contribute in future to the Shortsprightly Review, not yours!

Editor to Eminent Writer.—No offence meant. Is there any other Review besides mine? Never heard of the one you mentioned.

Eminent Writer to Editor (a month later).—I say, what's this? Virulent personal attack on me in your Review, signed with your name! Pretends my article on giving up Canada, &c., was all a joke! Am I the sort of man who would joke about anything? Reply at once, with apology, or I skin you alive in next Number of Shortsprightly.

Editor to Eminent Writer.—Sorry you're offended. I thought my Article rather a moderate one. Quite true that I talk about falsehood, hypocrites, effrontery, demagogues, Pharisees, and so on; but expressions to be taken in strictly Pickwickian sense, and of course not intended for you.

Eminent Writer to Editor.—Explanation unsatisfactory. You first insert contribution, and then slate it. Do you call yourself an Editor?

Editor to Eminent Writer.—Rather think I do call myself Editor. Couldn't insert that humbug about India and Canada without reply. By the bye, have forgotten if you spell Christian name with or without K? Important. Wire back.

Eminent Writer to Editor.—Yah! Look out for next Shortsprightly, that's all! Article entitled, "Editorial Horseplay." It'll give you fits, or my name isn't—FREDERIC, without the K.

Yes! Thou must be another's. Oh,

Such anguish stands alone!

I'd always fancied thou wert so

Peculiarly mine own;

No welcome doubt my soul can free;

A convict may not choose—

Yet, since another's thou must be,

Most kindly tell me whose?

Is it the Lord of Shilling Thrills

Who penned The Black that Mails—

That martial man who from the hills

Excogitates his tales?

Is it ubiquitous A. LANG?

Nay, shrink not but explain

To which of all the writing gang

Dost properly pertain?

Perchance to some provincial churl,

Who blushes quite unseen?

Perchance to some ambitious Earl

Or Stockbroker, I ween?

Such things have frequently occurred,

And gems like thee have crowned

The titular and moneyed herd,

And made them nigh renowned.

I know not, this alone is clear,

Thou wert my sole delight;

I pored on thee by sunshine, dear,

I dreamed of thee at night.

Thou wert so good—too splendid for

The common critic's praise—

And I was thy proprietor—

And all the world must gaze!

But Punch, that autocrat, decrees

That thou another's art:

I cannot choose but bow my knees

And lacerate my heart.

Thou must be someone's else, alack!

The truth remains confessed—

For Mr. P. hath sent thee back,

My cherished little Jest.

FROM A FLY-LEAF.—"Buzziness first, pleasure after," as the bluebottle said when, after circling three times about the breakfast-table, he alighted on a lump of sugar.

How slow is fate from fatal friends to free us!

Still, still, alas! 'tis "Ego et RAIKES meus."

"THE OXFORD MOVEMENT."—Not much to choose between this and the Cambridge movement in the last race.

PLACE OF BANISHMENT FOR MISTAKEN PERSONS.—The Isle of Mull.

The coarser Cyclops now combine

To push the Olympians from their places;

And dead as Pan seems the old line

Of greater gods and gentler graces.

Pleasant, amidst the clangour crude

Of smiting hammer, sounding anvil,

As bland Arcadian interlude,

The courtly accents of a GRANVILLE!

A strenuous time's pedestrian muse

Shouts pæans to the earth-born giant,

Whose brows Apollo's wreath refuse,

Whose strength to Charis is unpliant.

Demos distrusts the debonair,

Yet Demos found himself disarming

To gracious GRANVILLE; unaware

Won by the calm, witched by the charming.

Bismarckian vigour, stern and stark

As Brontes self, was not his dower;

Not his to steer a storm-tost bark

Through waves that whelm, and clouds that lower.

Temper unstirred, unerring tact,

Were his. He could not "wave the banner,"

But he could lend to steely act

The softly silken charm of manner.

Kindly, accomplished, with a wit

Lambent yet bland, like summer lightning;

Venomless rapier-point, whose "hit"

Was palpable, yet painless. Brightening

E'en, party conflict with a touch

Of old-world grace fight could not ruffle!

Faith, GRANVILLE, we shall miss thee much

Where kites and crows of faction scuffle!

AN IRISH DIAMOND.—The Cork Examiner of 28th ultimo contained an official advertisement, signed by the High Sheriff of the County of the City of Cork, requesting certain persons connected with the Spring Assizes to attend at the Model Schools, as the Court House had been destroyed by fire. Amongst those thus politely invited to be present on so interesting an occasion were the Prisoners!

Head of the Family! That makes me quail.

I am the Head—and thereby hangs a tale!

This big blue paper, ruled in many a column,

Gives rise to some misgivings sad and solemn.

Relation to that Head? That Head's buzz-brained,

And its "relations" are—just now—"much strained."

Citizen-duty I've no wish to shirk,

But would the State do its own dirty work—

(My daughters swear 'tis dirty). I'd be grateful.

Instructions? Yes! Imperative and fateful!

But, oh! I wish they would "instruct" me how

To tell the truth without a family row.

"Best of my knowledge and belief"! Ah well

If Aunt MEHITABEL her age won't tell;

If Cook will swear she's only thirty-three,

And rather fancies she was born at sea

(Where I am now) my "knowledge and belief"

Are not worth much to the official chief,

BRIDGES P. HENNIKER, if he only knew it.

A True Return? Well, if it is not true, it

Is not my fault. Inquisitorial band,

I've done my level best—Witness my Hand!

The bothering business makes me feel quite bilious,

Peace now—for ten years more!

"Of the best! of the very best!" as ZERO or CIRO is perpetually affirming of everything eatable and drinkable that is for his own benefit and his customers' refreshment at the little bar, not a hundred miles from the Monte Carlo tables, where he himself and his barristers practise day and night; and, as this famous cutter of sandwiches and confectioner of drinks says of his stock in trade, so say we of L'Enfant Prodigue, which, having been translated by HORATIUS COCLES SEDGER from Paris to London, has gone straight to the heart and intelligence of our Theatre-loving public.

It is a subject for curious reflection that, just when the comic scenes of our English Pantomime have been crushed out by overpowering weight of gorgeous spectacle, there should re-appear in our midst a revival of the ancient Pierrot who pantomimed himself into public favour with the Parisians towards the close of the seventeenth century. Red-hot poker, sausages, and filching Clown have had their day, and lo! when everyone said we were tired of the "comic business" of Pantomime, here in our midst re-appear almost in their habits as they lived, certainly with their white faces and black skull-caps "as they appeared," a pair of marvellously clever Pierrots. Mlle. JANE MAY as Pierrot Junior, "the Prodigy son," and M. COURTÈS as Pierrot Senior, are already drawing the town to Matinées at the Prince of Wales's, causing us to laugh at them and with them in their joys, and to weep with them in their mimic sorrows. Yes! Pierrot redivivus!

Mind you, it is not a piece for children; make no mistake about that; they will only laugh at the antics, be ignorant of the story, and be untouched by its truth and pathos. All are good. We like the naughty blanchisseuse the least of the characters, and wish she had been plus petite que ça. But is it not in nature that the prodigal infant (veritable boy is Mlle. JANE MAY) should fall in love with a young woman some years his senior, and far beyond him in experience of the world? Why certainly. Then the Baron, played with great humour by M. LOUIS GOUGET, who wins the Mistress with his diamonds, and the inimitable Black Servant, M. JEAN ARCUEIL, who laughs at poor little Pierrot, and cringes to his wealthy rival and successor,—are they not both admirable? As for the acting of Madame SCHMIDT as Madame Pierrot, loving wife and devoted mother, it is, as it should be, "too good for words." Her pantomimic action is so sympathetic throughout, so—well, in fact, perfect. Who wants to hear them speak? Facta non verba is their motto. Yet with what gusto the Black, heavily bribed, mouths out the titled Baron's name, though never a syllable does he utter! It is all most excellent make-believe.

Vive Pierrot à Londres! We see him much the same as he was when he delighted the Parisians in 1830,—"Avec sa grand casaque à gros boutons, son large pantalon flottant, ses souliers blancs comme le rests, son visage enfariné, sa tête couverte d'un serre-tête noir ... le véritable Pierrot avec sa bonhomie naïve ... ses joies d'enfant, et ses chagrins d'un effet si comique"—and also so pathetic.

If this entertainment could be given at night, the house would be crammed during a long run; but afternoon possibilities are limited. More than a word of praise must be given to M. ANDRÉ WORMSER's music, which, personally conducted by Mr. CROOK, goes hand in hand with the story written by MICHEL CARRÉ FILS, and illustrated by these clever pantomimists. No amateur of good acting should fail to see this performance. Verb. sap.

In the Salon this year, the Athenæum says, "a Grand Salon de Repos will be provided." For pictures of "still life" only, we suppose. Will Sir FREDERICK, P.R.A., act on the suggestion, and set aside one of the rooms in Burlington House as a Dormitory?

Aha! special attraction in The New Review! "April Fool's Day Poem," by ALFRED AUSTIN, and, an announcement on the cover that "This number contains a Picture of Miss ELLEN TERRY in one of her earliest parts." Oh, dear! I wish it didn't contain this picture, which is a bleared red photograph of Misses KATE and ELLEN TERRY, "as they appeared" (as they never could appear, I'm sure) in an entertainment which achieved a great success in the provinces—but not with this red-Indian picture as a poster. Of course it may be intended as compliment-terry; it may mean "always entertaining and ever reddy." However, the picture is naught, except as a curiosity; but the first instalment of our ELLEN's reminiscences is delightfully written, because given quite naturally, just as the celebrated actress herself would dictate—(of course she never has to "dictate," as her scarcely-breathed wish is a law)—to her pleasantly-tasked amanuensis. Next lot, please!

In Macmillan's for this month, ANDRÉ HOPE tells a fluttering tale in recounting "A Mystery of Old Gray's Inn." It would have come well from that weird old clerk, to whom Mr. Pickwick listened with interest during the convivialities at the "Magpie and Stump." It should take a prominent place in the proposed new issue of Half Hours with Jumpy Authors.

The Baron has just read a delightful paper on "The Bretons at Home," by CHARLES G. WOOD, in the Argosy, for this month. The Baron who has been there, and still would go if he could, but, as he can't, he is contented to let "WOOD go" without him, and to read the latter's tales of a traveller.

Turf Celebrities I have Known, by WILLIAM DAY, is a gossipy, snarly sort of book; casting a rather murky or grey Day-light on a considerable number of Celebrities who were once on the turf, and are now under it. But the Baron not being himself either on the turf or under it, supposes that this DAY is an authority, as was once upon a time, that is, only the other day, the Dey of ALGIERS. But this DAY is not of Algiers, but of All-gibes. Ordinarily it is true that "Every dog has his day." Exceptions prove the rule, and it would appear from this book—"not the first 'book,' I suppose," quoth the Baron, "that Mr. DAY has 'made' or assisted in 'making,'"—that not every dog did not 'have' this particular Day, but that some dogs did. The writer has missed the chance of a good title—not for himself, but for his book. He should have it an autobiography, and then call it, "De Die in Diem; or, Day by Day."

And so Mr. ELLERSDEE approached his proposed recruit, and invited him to lunch to discuss the matter quietly.

"You are very good," returned the other, "but I can assure you I eat nothing before dinner. Won't you have a cigar?"

Mr. ELLERSDEE accepted the proffered kindness, and remarked upon the excellent quality of the tobacco.

"Yes," assented his companion, "it is not half bad, for we get all our supplies from the Stores; and now what can I do for you?"

Then Mr. ELLERSDEE unfolded his sad story. England was losing her commercial prosperity, owing to a scarcity of labourers, artisans, nay, even clerks. The Empire was in as bad a condition as those foreign countries in which forced military service was established. Like France and Germany, trade was being ruined by the Army. Would not the young man desert, and become a recruit in the Labour League?

"My dear friend," was the reply, "I hope I am as patriotic as most people, but I cannot sacrifice my just interest entirely to sentiment. What can you give me in exchange for my present life? I have recreation-rooms, libraries, polytechnics, and every sort of amusement?"

"But also drill and discipline," urged the other.

"Which I am told by my medical attendant (whose services by the way are gratuitous), are excellent for my health. This being so, I can scarcely complain of those institutions. Then I have excellent pay and ample food. Now, I ask you frankly, can the advantages offered by Trade compare for a moment with the privileges, as a soldier, I now enjoy? Tell me frankly, shall I improve my position by giving up the Army?"

And Mr. ELLERSDEE was compelled to answer in the negative!

April 1.—My birthday; have no idea which. Old as the hills, but not quite so pointed; venerable, but broken down, and used up; not the Joke I used to be; once the rich darling of Society: but it (Society) didn't pay, so had to work hard for a living. Tit Bits, the National Observer, and the Chancery Judges, have impoverished me. Never mind—I'll be revenged—resolve to keep a Diary—"weekly diary of a weakly"—oh dear! my old infirmity again. Must really be more careful.

April 2.—In with the rest of them, for a (North-) Easter outing. HACKING, in the train, tried to palm me off upon HORNBLOWER, who had actually the impudence to affect that he "couldn't see me"; as if I hadn't obviously made his reputation for years! The best of it is, that HORNBLOWER is always airing me in public, and dropping me in private. Blow HORNBLOWER!

April 3.—Out to dinner. What a hypocrite Society is! Everyone pretended never to have heard me before. I was allotted to Miss HORNBLOWER (worse luck!) and she positively called me "Her own!"—at my age, too! It's indecent. Complained to HORNBLOWER, who now faced round, and maintained that he was the first to bring me out. I could almost have cried. No wonder I fell flat, and injured myself. Why, Sir, SIDNEY SMITH was my godfather, and was always trotting me out as a prodigy, and trading on me. I supported him, Sir, when I was but an infant phenomenon; I supported him—but I can't support HORNBLOWER.

April 4.—Went to the theatre, as I was told I figured in the play; claimed a free pass to the Stalls from the box-office boy, who was rude; showed him my card; he looked scared, and said it was all right. The actors were full of me: very gratifying; but everybody laughed! Just like their cheek! There's nothing laughable, I should fancy, about anything so played out as I've become. Ugh! how I detest irreverence! HORNBLOWER and HACKING have both written to the papers, maintaining that I belong to them, and that the theatre has no right to have me impersonated on the Stage; they term it "Thought Transference," "The Brain-Wave," or something outlandish; and to think that HACKING, who reviews HORNBLOWER's effusions, once spoke of me as stale! They had better not try my patience too far, I can tell them.

April 5.—Sunday. Want change, and rest. Made for the O'WILDE's sanctum. Cabman took the change, and O'WILDE the rest. Have known all the celebrities of the century, but like O'W. the most. For one so young, he's truly affable; made me quite at home; promised to put me up—or in, I forget which; and then he uttered this remarkable "preface"—"Jokes are neither old nor young: they are simply mine or thine—that is all." Nevertheless. I'm sure to be in his bad books before long.

April 6.—"Horrible outrage—an Old Joke, in trouble again"—so run the newspaper placards—was collared forcibly by two masked ruffians in Grub Street, and dispatched post-haste to Punch office. Mr. P., however, had known me from a boy, and was not to be imposed upon. He sent me back promptly, on Her Majesty's Service, warning me that, unless I went off, I should probably be knocked on the head. Dear EVERGREEN POLICINELLO! but not so evergreen as all that. He knows my constitution won't stand these liberties. The desperadoes turn out to be HORNBLOWER and HACKING, as I suspected. In defence they alleged I had struck them forcibly! Mr. P. vows he'll proceed against them for nuisance—interfering with Ancient Lights.

April 7.—Very weak, from effects of yesterday. The heart taken out of me. Consult my Doctor. To judge from the prints in his waiting-room, I'm popular enough still with his patients. Says I'm suffering from a bad attack of Printer's Devils, but can't make me younger; replied that my desire was to be older. He looked grave, and rejoined, "Impossible"; prescribed a course of Attic salts; as I came out, met Sir WILFRID LAWSON. He declares I don't look a day older than when he first knew me; but then, he's licensed to be sober on the premises! Ah, how I love the House of Commons!

April 8.—Worn to a skeleton; sinking fast, but I'll die hard. Make my will. Bequeath Autographs of TALLEYRAND and JOE MILLER to Madame Tussaud's; everything else to be sold for the foundation of an Asylum for Old Jokes. A knock at the door. Heaven help me!—two Interviewers! "Come in," I said, with the conventional "cheery voice." Anticipated the worst, but worse than I anticipated. HORNBLOWER and HACKING are brooding over me; assert they have been sent by the LORD MAYOR. "Thought Transference" again! Well, I should have committed suicide, and now I can be released without crime. It won't last long. If I might suggest my obsequies, I should like to be cremated in Type. HACKING begs my blessing, and pretends to weep at hearing the last of me. Hope I shan't ever have to haunt HORNBLOWER!

Editor's Postscript.—We have paid a pious visit to his last Jesting-place; on the urn is inscribed,—

NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.