Title: The Captain's Toll-Gate

Author: Frank R. Stockton

Contributor: Marian E. Stockton

Release date: September 2, 2004 [eBook #13356]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/13356

Credits: Produced by Stephen Schulze and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

With a Memorial Sketch by Mrs. Stockton

1903

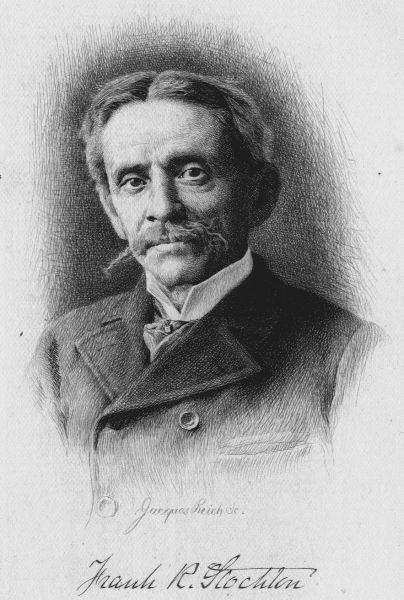

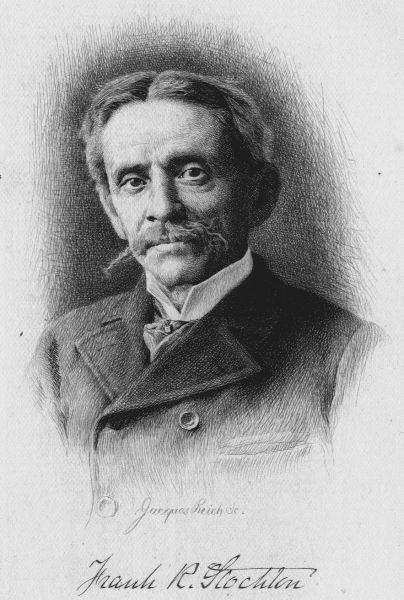

Portrait of Frank B. Stockton Etching by Jacques Reich from a photograph.

The Holt, Mr. Stockton's home near Convent, N.J.

Claymont, Mr. Stockton's home near Charles Town, West Virginia.

A corner in Mr. Stockton's study at Claymont.

The upper terraces of Mr. Stockton's garden at Claymont.

As this—The Captain's Toll-Gate—is the last of the works of Frank R. Stockton that will be given to the public, it is fitting that it be accompanied by some account of the man whose bright spirit illumined them all. It is proper, also, that something be said of the stories themselves; of the circumstances in which they were written, the influences that determined their direction, and the history of their evolution. It seems appropriate that this should be done by the one who knew him best; the one who lived with him through a long and beautiful life; the one who walked hand in hand with him along the whole of a wonderful road of ever-changing scenes: now through forests peopled with fairies and dryads, griffins and wizards; now skirting the edges of an ocean with its strange monsters and remarkable shipwrecks; now on the beaten track of European tourists, sharing their novel adventures and amused by their mistakes; now resting in lovely gardens imbued with human interest; now helping the young to make happy homes for themselves; now sympathizing with the old as they look longingly toward a heavenly home; and, oftenest, perhaps, watching girls and young men as they were trying to work out the problems of their lives. All this, and much more, crowded the busy years until the Angel of Death stood in the path; and the journey was ended.

In regard to the present story—The Captain's Toll-Gate—although it is now after his death first published, it was all written and completed by Mr. Stockton himself. No other hand has been allowed to add to, or to take from it. Mr. Stockton had so strong a feeling upon the literary ethics involved in such matters that he once refused to complete a book which a popular and brilliant author, whose style was thought to resemble his own, had left unfinished. Mr. Stockton regarded the proposed act in the light of a sacrilege. The book, he said, should be published as the author left it. Knowing this fact, readers of the present volume may feel assured that no one has been permitted to tamper with it. Although the last book by Mr. Stockton to be published, it is not the last that he wrote. He had completed The Captain's Toll-Gate, and was considering its publication, when he was asked to write another novel dealing with the buccaneers. He had already produced a book entitled Buccaneers and Pirates of our Coasts. The idea of writing a novel while the incidents were fresh in his mind pleased him, and he put aside The Captain's Toll-Gate, as the other book—Kate Bonnet—was wanted soon, and he did not wish the two works to conflict in publication. Steve Bonnet, the crazy-headed pirate, was a historical character, and performed the acts attributed to him. But the charming Kate, and her lover, and Ben Greenaway were inventions.

Francis Richard Stockton, born in Philadelphia in 1834, was, on his father's side, of purely English ancestry; on his mother's side, there was a mixture of English, French, and Irish. When he began to write stories these three nationalities were combined in them: the peculiar kind of inventiveness of the French; the point of view, and the humor that we find in the old English humorists; and the capacity of the Irish for comical situations.

Soon after arriving in this country the eldest son of the first American Stockton settled in Princeton, N.J., and founded that branch of the family; while the father, with the other sons, settled in Burlington County, in the same State, and founded the Burlington branch of the family, from which Frank R. Stockton was descended. On the female side he was descended from the Gardiners, also of New Jersey. His was a family with literary proclivities. His father was widely known for his religious writings, mostly of a polemical character, which had a powerful influence in the denomination to which he belonged. His half-brother (much older than Frank) was a preacher of great eloquence, famous a generation ago as a pulpit orator.

When Frank and his brother John, two years younger, came to the age to begin life for themselves, they both showed such decided artistic genius that it was thought best to start them in that direction, and to have them taught engraving; an art then held in high esteem. Frank chose wood, and John steel engraving. Both did good work, but their hearts were not in it, and, as soon as opportunity offered, they abandoned engraving. John went into journalism; became editorially connected with prominent newspapers; and had won a foremost place in his chosen profession; when he was cut off by death at a comparatively early age.

Frank chose literature. He had, while in the engraving business, written a number of fairy tales, some of which had been published in juvenile magazines; also a few short stories, and quite an ambitious long story, which was published in a prominent magazine. He was then sufficiently well known as a writer to obtain without difficulty a place on the staff of Hearth and Home, a weekly New York paper, owned by Orange Judd, and conducted by Edward Eggleston. Mrs. Mary Mapes Dodge had charge of the juvenile department, and Frank went on the paper as her assistant. Not long after Scribner's Monthly was started by Charles Scribner (the elder), in conjunction with Roswell Smith, and J.G. Holland. Later Mr. Smith and his associates formed The Century Company; and with this company Mr. Stockton was connected for many years: first on the Century Magazine, which succeeded Scribner's Monthly, and afterward on St. Nicholas, as assistant to Mrs. Mary Mapes Dodge, and, still later, when he decided to give up editorial work, as a constant contributor. After a few years he resigned his position in the company with which he had been so pleasantly associated in order to devote himself exclusively to his own work. By this time he had written and published enough to feel justified in taking, what seemed to his friends, a bold, and even rash, step, because so few writers then lived solely by the pen. He was never very strong physically; he felt himself unable to do his editorial work, and at the same time write out the fancies and stories with which his mind was full. This venture proved to be the wisest thing for him; and from that time his life was, in great part, in his books; and he gave to the world the novels and stories which bear his name.

I have mentioned his fairy stories. Having been a great lover of fairy lore when a child, he naturally fell into this form of story writing as soon as he was old enough to put a story together. He invented a goodly number; and among them the Ting-a-Ling stories, which were read aloud in a boys' literary circle, and meeting their hearty approval, were subsequently published in The Riverside Magazine, a handsome and popular juvenile of that period; and, much later, were issued by Hurd & Houghton in a very pretty volume. In regard to these, he wrote long afterward as follows:

"I was very young when I determined to write some fairy tales because my mind was full of them. I set to work, and in course of time produced several which were printed. These were constructed according to my own ideas. I caused the fanciful creatures who inhabited the world of fairy-land to act, as far as possible for them to do so, as if they were inhabitants of the real world. I did not dispense with monsters and enchanters, or talking beasts and birds, but I obliged these creatures to infuse into their extraordinary actions a certain leaven of common sense."

It was about this time, while very young, that he and his brother became ambitious to write stories, poems, and essays for the world at large. They sent their effusions to various periodicals, with the result common to ambitious youths: all were returned. They decided at last that editors did not know a good thing when they saw it, and hit upon a brilliant scheme to prove their own judgment. One of them selected an extract from Paradise Regained (as being not so well known as Paradise Lost), and sent it to an editor, with the boy's own name appended, expecting to have it returned with some of the usual disparaging remarks, which they would greatly enjoy. But they were disappointed. The editor printed it in his paper, thereby proving that he did know a good thing if he did not know his Milton. Mr. Stockton was fond of telling this story, and it may have given rise to a report, extensively circulated, that he tried to gain admittance to periodicals for many years before he succeeded. This is not true. Some rebuffs he had, of course—some with things which afterward proved great successes—but not as great a number as falls to the lot of most beginners.

The Ting-a-Ling tales proved so popular that Mr. Stockton followed them at intervals with long and short stories for the young which appeared in various juvenile publications, and were afterward published in book form—Roundabout Rambles. Tales out of School, A Jolly Fellowship, Personally Conducted, The Story of Viteau, The Floating Prince, and others. Some years later, after he had begun to write for older readers, he wrote a series of stories for St. Nicholas, ostensibly for children, but really intended for adults. Children liked the stories, but the deeper meaning underlying them all was beyond the grasp of a child's mind. These stories Mr. Stockton took very great pleasure in writing, and always regarded them as some of his best work, and was gratified when his critics wrote of them in that way. They have become famous, and have been translated into several languages, notably Old Pipes and the Dryad, The Bee Man of Orne, and The Griffin and the Minor Canon. This last story was suggested by Chester Cathedral, and he wrote it in that venerable city. The several tales were finally collected into a volume under the title: The Bee Man of Orne and Other Stories, which is included in the complete edition of his novels and stories. During the whole of his literary career Mr. Stockton was an occasional contributor of short stories and essays to The Youth's Companion.

Mr. Stockton considered his career as an editor of great advantage to him as an author. In an autobiographical paper he writes: "Long-continued reading of manuscripts submitted for publication which are almost good enough to use, and yet not quite up to the standard of the magazine, can not but be of great service to any one who proposes a literary career. Bad work shows us what we ought to avoid, but most of us know, or think we know, what that is. Fine literary work we get outside the editorial room. But the great mass of literary material which is almost good enough to print is seen only by the editorial reader, and its lesson is lost upon him in a great degree unless he is, or intends to be, a literary worker."

The first house in which we set up our own household goods stood in Nutley, N.J. We had with us an elderly attaché of the Stockton family as maid-of-all-work; and to relieve her of some of her duties I went into New York, and procured from an orphans' home a girl whom Mr. Stockton described as "a middle-sized orphan." She was about fourteen years old, and proved to be a very peculiar individual, with strong characteristics which so appealed to Mr. Stockton's sense of humor that he liked to talk with her and draw out her opinions of things in general, and especially of the books she had read. Her spare time was devoted to reading books, mostly of the blood-curdling variety; and she read them to herself aloud in the kitchen in a very disjointed fashion, which was at first amusing, and then irritating. We never knew her real name, nor did the people at the orphanage. She had three or four very romantic ones she had borrowed from novels while she was with us, for she was very sentimental.

Mr. Stockton bestowed upon her the name of Pomona, which is now a household word in myriads of homes. This extraordinary girl, and some household experiences, induced Mr. Stockton to write a paper for Scribner's Monthly which he called Rudder Grange. This one paper was all he intended to write, but it attracted immediate attention, was extensively noticed, and much talked about. The editor of the magazine received so many letters asking for another paper that Mr. Stockton wrote the second one; and as there was still a clamor for more, he, after a little time, wrote others of the series. Some time later they were collected in a book. For those interested in Pomona I will add, that while the girl was an actual personage, with all the characteristics given to her by her chronicler, the woman Pomona was a development in Mr. Stockton's mind of the girl as he imagined she would become, for the original passed out of our lives while still a girl.

Rudder Grange was Mr. Stockton's first book for adult readers, and a good deal of comment has been made upon the fact that he had reached middle life when it was published. His biographers and critics assume that he was utterly unknown at that time, and that he suddenly jumped into favor, and they naturally draw the inference that he had until then vainly attempted to get before the public. This is all a misapprehension of the facts. It will be seen from what I have previously stated, that at this time he was already well known as a juvenile writer, and not only had no difficulty in getting his articles printed, but editors and publishers were asking him for stories. He had made but few slight attempts to obtain a larger audience. That he confined himself for so long a time to juvenile literature can be easily accounted for. For one thing, it grew out of his regular work of constantly catering for the young, and thinking of them. Then, again, editorial work makes urgent demands upon time and strength, and until freed from it he had not the leisure or inclination to fashion stories for more exacting and critical readers. Perhaps, too, he was slow in recognizing his possibilities. Certain it is that the public were not slow to recognize him. He did, however, experience difficulties in getting the collected papers of Rudder Grange published in book form. I will quote his own account, which is interesting as showing how slow he was to appreciate the fact that the public would gladly accept the writings of a humorist:

"The discovery that humorous compositions could be used in journals other than those termed comic marked a new era in my work. Periodicals especially devoted to wit and humor were very scarce in those days, and as this sort of writing came naturally to me, it was difficult, until the advent of Puck, to find a medium of publication for writings of this nature. I contributed a good deal to this paper, but it was only partly satisfactory, for articles which make up a comic paper must be terse and short, and I wanted to write humorous tales which should be as long as ordinary magazine stories. I had good reason for my opinion of the gravity of the situation, for the editor of a prominent magazine declined a humorous story (afterward very popular) which I had sent him, on the ground that the traditions of magazines forbade the publication of stories strictly humorous. Therefore, when I found an editor at last who actually wished me to write humorous stories, I was truly rejoiced. My first venture in this line was Rudder Grange. And, after all, I had difficulty in getting the series published in book form. Two publishers would have nothing to do with them, assuring me that although the papers were well enough for a magazine, a thing of ephemeral nature, the book-reading public would not care for them. The third publisher to whom I applied issued the work, and found the venture satisfactory."

The book-reading public cared so much for this book that it would not remain satisfied with it alone. Again and again it demanded of the author more about Pomona, Euphemia, and Jonas. Hence The Rudder Grangers Abroad and Pomona's Travels.

The most famous of Mr. Stockton's stories, The Lady or the Tiger?, was written to be read before a literary society of which he was a member. It caused such an interesting discussion in the society that he published it in the Century Magazine. It had no especial announcement there, nor was it heralded in any way, but it took the public by storm, and surprised both the editor and the author. All the world must love a puzzle, for in an amazingly short time the little story had made the circuit of the world. Debating societies everywhere seized upon it as a topic; it was translated into nearly all languages; society people discussed it at their dinners; plainer people argued it at their firesides; numerous letters were sent to nearly every periodical in the country; and public readers were expounding it to their audiences. It interested heathen and Christian alike; for an English friend told Mr. Stockton that in India he had heard a group of Hindoo men gravely debating the problem. Of course, a mass of letters came pouring in upon the author.

A singular thing about this story has been the revival of interest in it that has occurred from time to time. Although written many years ago, it seems still to excite the interest of a younger generation; for, after an interval of silence on the subject of greater or less duration, suddenly, without apparent cause, numerous letters in relation to it will appear on the author's table, and "solutions" will be printed in the newspapers. This ebb and flow has continued up to the present time. Mr. Stockton made no attempt to answer the question he had raised.

We both spent much time in the South at different periods. The dramatic and unconsciously humorous side of the negroes pleased his fancy. He walked and talked with them, saw them in their homes, at their "meetin's," and in the fields. He has drawn with an affectionate hand the genial, companionable Southern negro as he is—or rather as he was—for this type is rapidly passing away. Soon there will be no more of these "old-time darkies." They would be by the world forgot had they not been embalmed in literature by Mr. Stockton, and the best Southern writers.

There is one other notable characteristic that should be referred to in writing of Mr. Stockton's stories—the machines and appliances he invented as parts of them. They are very numerous and ingenious. No matter how extraordinary might be the work in hand, the machine to accomplish the end was made on strictly scientific principles, to accomplish that exact piece of work. It would seem that if he had not been an inventor of plots he might have been an inventor of instruments. This idea is sustained by the fact that he had been a wood-engraver only a short time when he invented and patented a double graver which cuts two parallel lines at the same time. It is somewhat strange that more than one of these extraordinary machines has since been exploited by scientists and explorers, without the least suspicion on their part that the enterprising romancer had thought of them first. Notable among these may be named the idea of going to the north pole under the ice, the one that the center of the earth is an immense crystal (Great Stone of Sardis), and the attempt to manufacture a gun similar to the Peace Compeller in The Great War Syndicate.

In all of Mr. Stockton's novels there were characters taken from real persons who perhaps would not recognize themselves in the peculiar circumstances in which he placed them. In the crowd of purely imaginative beings one could easily recognize certain types modified and altered. In The Casting away of Mrs. Leeks and Mrs. Aleshine he introduced two delightful old ladies whom he knew, and who were never surprised at anything that might happen. Whatever emergency arose, they took it as a matter of course, and prepared to meet it. Mr. Stockton amused himself at their expense by writing this story. He was not at first interested in the Dusantes, and had no intention of ever saying anything further about them. When there was a demand for knowledge of the Dusantes Mr. Stockton did not heed it. He was opposed to writing sequels. But when an author of distinction, whose work and friendship he highly valued, wrote to him that if he did not write something about the Dusantes, and what they said when they found the board money in the ginger jar, he would do it himself, Mr. Stockton set himself to writing The Dusantes.

I have been asked to give some account of the places in which Mr. Stockton's stories and novels were written, and their environments. Some of the Southern stories were written in Virginia, and, now and then, a short story elsewhere, as suggested by the locality, but the most of his work was done under his own roof-tree. He loved his home; it had to be a country home, and always had to have a garden. In the care of a garden and in driving, he found his two greatest sources of recreation.

I have mentioned Nutley, which lies in New Jersey, near New York. His dwelling there was a pretty little cottage, where he had a garden, some chickens, and a cow. This was his home in his editorial days, and here Rudder Grange was written. It was a rented place. The next home we owned. It stood at a greater distance from New York, at the place called Convent, half-way between Madison and Morristown, in New Jersey. Here we lived a number of years after Mr. Stockton gave up editorial work; and here the greater number of his tales were written. It was a much larger place than we had at Nutley, with more chickens, two cows, and a much larger garden.

Mr. Stockton dictated his stories to a stenographer. His favorite spot for this in summer was a grove of large fir-trees near the house. Here, in the warm weather, he would lie in a hammock. His secretary would be near, with her writing materials, and a book of her choosing. The book was for her own reading while Mr. Stockton was "thinking." It annoyed him to know he was being "waited for." He would think out pages of incidents, and scenes, and even whole conversations, before he began to dictate. After all had been arranged in his mind he dictated rapidly; but there often were long pauses, when the secretary could do a good deal of reading. In cold weather he had the secretary and an easy chair in the study—a room he had built according to his own fancy. A fire of blazing logs added a glow to his fancies.

I may state here that we always spent a part of every winter in New York. A certain amount of city life was greatly enjoyed. Mr. Stockton thus secured much intellectual pleasure. He liked his clubs, and was fond of society, where he met men noted in various walks of life.[1]

Edward Gary, the secretary of the Century Club, in the obituary notice of Mr. Stockton written by him for the club's annual report, says of Mr. Stockton as a member: "It was but a dozen years ago that Frank R. Stockton entered the fellowship of the Century, in which he soon became exceedingly at home, winning friends here, as he won them all over the land and in other lands, by the charm of his keen and kindly mind shining in all that he wrote and said. He had an extraordinary capacity for work and a rare talent for diversion, and the Century was honored by his well-earned fame, and fortunate in its share in his ever fresh and varying companionship."

I am now nearing the close of a life which had had its trials and disappointments, its struggles with weak health and with unsatisfying labor. But these mostly came in the earlier years, and were met with courage, an ever fresh-springing hope, and a buoyant spirit that would not be intimidated. On the whole, as one looks back through the long vista, much more of good than of evil fell to his lot. His life had been full of interesting experiences, and one of, perhaps, unusual happiness. At the last there came to pass the fulfilment of a dream in which he had long indulged. He became the possessor of a beautiful estate containing what he most desired, and with surroundings and associations dear to his heart.

He had enjoyed The Holt, his New Jersey home, and was much interested in improving it. His neighbors and friends there were valued companions. But in his heart there had always been a longing for a home, not suburban—a place in the real country, and with more land. Finally, the time came when he felt that he could gratify this longing. He liked the Virginia climate, and decided to look for a place somewhere in that State, not far from the city of Washington. After a rather prolonged search, we one day lighted upon Claymont, in the Shenandoah Valley. It won our hearts, and ended our search. It had absolutely everything that Mr. Stockton coveted. He bought it at once, and we moved into it as speedily as possible.

Claymont is a handsome colonial residence, "with all modern improvements"—an unusual combination. It lies near the historic old town of Charles Town, in West Virginia, near Harpers Ferry. Claymont is itself an historic place. The land was first owned by "the Father of his Country." This great personage designed the house, with its main building, two cottages (or lodges), and courtyards, for his nephew Bushrod, to whom he had given the land. Through the wooded park runs the old road, now grass grown, over which Braddock marched to his celebrated "defeat," guided by the youthful George Washington, who had surveyed the whole region for Lord Fairfax. During the civil war the place twice escaped destruction because it had once been the property of Washington.

But it was not for its historical associations, but for the place itself, that Mr. Stockton purchased it. From the main road to the house there is a drive of three-quarters of a mile through a park of great forest-trees and picturesque groups of rocks. On the opposite side of the house extends a wide, open lawn; and here, and from the piazzas, a noble view of the valley and the Blue Ridge Mountains is obtained. Besides the park and other grounds, there is a farm at Claymont of considerable size. Mr. Stockton, however, never cared for farming, except in so far as it enabled him to have horses and stock. But his soul delighted in the big, old terraced garden of his West Virginia home. Compared with other gardens he had had, the new one was like paradise to the common world. At Claymont several short stories were written. John Gayther's Garden was prepared for publication here by connecting stories previously published into a series, told in a garden, and suggested by the one at Claymont. John Gayther, however, was an invention. Kate Bonnet and The Captain's Toll-Gate were both written at Claymont.

Mr. Stockton was permitted to enjoy this beautiful place only three years. They were years of such rare pleasure, however, that we can rejoice that he had so much joy crowded into so short a space of his life, and that he had it at its close. Truly life was never sweeter to him than at its end, and the world was never brighter to him than when he shut his eyes upon it. He was returning from a winter in New York to his beloved Claymont, in good health, and full of plans for the summer and for his garden, when he was taken suddenly ill in Washington, and died three days later, on April 20, 1902, a few weeks after Kate Bonnet was published in book form.

Mr. Stockton passed away at a ripe age—sixty-eight years. And yet his death was a surprise to us all. He had never been in better health, apparently; his brain was as active as ever; life was dear to him; he seemed much younger than he was. He had no wish to give up his work; no thought of old age; no mental decay. His last novels, his last short stories, showed no falling-off. They were the equals of those written in younger years. Nor had he lost the public interest. He was always sure of an audience, and his work commanded a higher price at the last than ever before. His was truly a passing away. He gently glided from the homes he had loved to prepare here to one already prepared for him in heaven, unconscious that he was entering one more beautiful than even he had ever imagined.

Mr. Stockton was the most lovable of men. He shed happiness all around him, not from conscious effort but out of his own bountiful and loving nature. His tender heart sympathized with the sad and unfortunate, but he never allowed sadness to be near, if it were possible to prevent it. He hated mourning and gloom. They seemed to paralyze him mentally until his bright spirit had again asserted itself, and he had recovered his balance. He usually looked either upon the best, or the humorous side of life. Pie won the love of every one who knew him—even that of readers who did not know him personally, as many letters testify. To his friends his loss is irreparable, for never again will they find his equal in such charming qualities of head and heart.

This is not the place for a critical estimate of the work of Frank R. Stockton.[2] His stories are, in great part, a reflex of himself. The bright outlook on life; the courageous spirit; the helpfulness; the sense of the comic rather than the tragic; the love of domestic life; the sweetness of pure affection; live in his books as they lived in himself. He had not the heart to make his stories end unhappily. He knew that there is much of the tragic in human lives, but he chose to ignore it as far as possible, and to walk in the pleasant ways which are numerous in this tangled world. There is much philosophy underlying a good deal that he wrote, but it has to be looked for; it is not insistent, and is never morbid. He could not write an impure word, or express an impure thought, for he belonged to the "pure in heart," who, we are assured, "shall see God."

I may, however, properly quote from the sketch prepared by Mr. Gary for the Century Club: "He brought to his later work the discipline of long and rather tedious labor, with the capital amassed by acute observation, on which his original imagination wrought the sparkling miracles that we know. He has been called the representative American humorist. He was that in the sense that the characters he created had much of the audacity of the American spirit, the thirst for adventures in untried fields of thought and action, the subconscious seriousness in the most incongruous situations, the feeling of being at home no matter what happens. But how amazingly he mingled a broad philosophy with his fun, a philosophy not less wise and comprehending than his fun was compelling! If his humor was American, it was also cosmopolitan, and had its laughing way not merely with our British kinsmen, but with alien peoples across the usually impenetrable barrier of translation. The fortune of his jesting lay not in his ears, but in the hearts of his hearers. It was at once appealing and revealing. It flashed its playful light into the nooks and corners of our own being, and wove close bonds with those at whom we laughed. There was no bitterness in it. He was neither satirist nor preacher, nor of set purpose a teacher, though it must be a dull reader that does not gather from his books the lesson of the value of a gentle heart and a clear, level outlook upon our perplexing world."

MARIAN E. STOCKTON.

CLAYMONT, May 15, 1903.

A long, wide, and smoothly macadamized road stretched itself from the considerable town of Glenford onward and northward toward a gap in the distant mountains. It did not run through a level country, but rose and fell as if it had been a line of seaweed upon the long swells of the ocean. Upon elevated points upon this road, farm lands and forests could be seen extending in every direction. But there was nothing in the landscape which impressed itself more obtrusively upon the attention of the traveler than the road itself. White in the bright sunlight and gray under the shadows of the clouds, it was the one thing to be seen which seemed to have a decided purpose. Northward or southward, toward the gap in the long line of mountains or toward the wood-encircled town in the valley, it was always going somewhere.

About two miles from the town, and at the top of the first long hill which was climbed by the road, a tall white pole projected upward against the sky, sometimes perpendicularly, and sometimes inclined at a slight angle. This was a turnpike gate or bar, and gave notice to all in vehicles or on horses that the use of this well-kept road was not free to the traveling public. At the approach of persons not known, or too well known, the bar would slowly descend across the road, as if it were a musket held horizontally while a sentinel demanded the password.

Upon the side of the road opposite to the great post on which the toll-gate moved, was a little house with a covered doorway, from which toll could be collected without exposing the collector to sun or rain. This tollhouse was not a plain whitewashed shed, such as is often seen upon turnpike roads, but a neat edifice, containing a comfortable room. On one side of it was a small porch, well shaded by vines, furnished with a settle and two armchairs, while over all a large maple stretched its protecting branches. Back of the tollhouse was a neatly fenced garden, well filled with old-fashioned flowers; and, still farther on, a good-sized house, from which a box-bordered path led through the garden to the tollhouse.

It was a remark that had been made frequently, both by strangers and residents in that part of the country, that if it had not been for the obvious disadvantages of a toll-gate, this house and garden, with its grounds and fields, would be a good enough home for anybody. When he happened to hear this remark Captain John Asher, who kept the toll-gate, was wont to say that it was a good enough home for him, even with the toll-gate, and its obvious disadvantages.

It was on a morning in early summer, when the garden had grown to be so red and white and yellow in its flowers, and so green in its leaves and stalks, that the box which edged the path was beginning to be unnoticed, that a girl sat in a small arbor standing on a slight elevation at one side of the garden, and from which a view could be had both up and down the road. She was rather a slim girl, though tall enough; her hair was dark, her eyes were blue, and she sat on the back of a rustic bench with her feet resting upon the seat; this position she had taken that she might the better view the road.

With both her hands this girl held a small telescope which she was endeavoring to fix upon a black spot a mile or more away upon the road. It was difficult for her to hold the telescope steadily enough to keep the object-glass upon the black spot, and she had a great deal of trouble in the matter of focusing, pulling out and pushing in the smaller cylinder in a manner which showed that she was not accustomed to the use of this optical instrument.

"Field-glasses are ever so much better," she said to herself; "you can screw them to any point you want. But now I've got it. It is very near that cross-road. Good! it did not turn there; it is coming along the pike, and there will be toll to pay. One horse, seven cents."

She put down the telescope as if to rest her arm and eye. Presently, however, she raised the glass again. "Now, let us see," she said, "Uncle John? Jane? or me?" After directing the glass to a point in the air about two hundred feet above the approaching vehicle, and then to another point half a mile to the right of it, she was fortunate enough to catch sight of it again. "I don't know that queer-looking horse," she said. "It must be some stranger, and Jane will do. No, a little boy is driving. Strangers coming along this road would not be driven by little boys. I expect I shall have to call Uncle John." Then she put down the glass and rubbed her eye, after which, with unassisted vision, she gazed along the road. "I can see a great deal better without that old thing," she continued. "There's a woman in that carriage. I'll go myself." With this she jumped down from the rustic seat, and with the telescope under her arm, she skipped through the garden to the little tollhouse.

The name of this girl was Olive Asher. Captain John Asher, who took the toll, was her uncle, and she had now been living with him for about six weeks. Olive was what is known in certain social circles as a navy girl. About twenty years before she had come to her uncle's she had been born in Genoa, her father at the time being a lieutenant on an American war-vessel lying in the harbor of Villa Franca. Her first schooldays were passed in the south of France, and she spent some subsequent years in a German school in Dresden. Here she was supposed to have finished her education but when her father's ship was stationed on our Pacific coast and Olive and her mother went to San Francisco they associated a great deal with army people, and here the girl learned so much more of real life and her own country people that the few years she spent in the far West seemed like a post-graduate course, as important to her true education as any of the years she had spent in schools.

After the death of her mother, when Olive was about eighteen, the girl had lived with relatives, East and West, hoping for the day when her father's three years' cruise would terminate, and she could go and make a home for him in some pleasant spot on shore. Now, in the course of these family visits she had come to stay with her father's brother, John Asher, who kept the toll-gate on the Glenford pike.

Captain John Asher was an older man than his brother, the naval officer, but he was in the prime of life, and able to hold the command of a ship if he had cared to do it. But having been in the merchant service for a long time, and having made some money, he had determined to leave the sea and to settle on shore; and, finding this commodious house by the toll-gate, he settled there. There were some people who said that he had taken the position of toll-gate keeper because of the house, and there were others who believed that he had bought the house on account of the toll-gate. But no matter what people thought or said, the good captain was very well satisfied with his home and his official position. He liked to meet with people, and he preferred that they should come to him rather than that he should go to them. He was interested in most things that were going on in his neighborhood, and therefore he liked to talk to the people who were going by. Sometimes a good talking acquaintance or an interesting traveler would tie his horse under the shade of the maple-tree and sit a while with the captain on the little porch. Certain it was, it was the most hospitable toll-gate in that part of the country.

There was a road which branched off from the turnpike, about a mile from the town, and which, after some windings, entered the pike again beyond the toll-gate, and although this road was not always in very good condition, it had seen a good deal of travel, which, in time, gave it the name of the shunpike. But since Captain Asher had lived at the toll-gate it was remarked that the shunpike was not used as much as in former times. There were penurious people who had once preferred to go a long way round and save money whose economical dispositions now gave way before the combined attractions of a better road, and a chat with Captain Asher.

It had been predicted by some of her relatives that Olive would not be content with her life in her uncle's somewhat peculiar household. He was a bachelor, and seldom entertained company, and his ordinary family consisted of an elderly housekeeper and another servant. But Olive was not in the least dissatisfied. From her infancy up, she had lived so much among people that she had grown tired of them; and her good-natured uncle, with his sea stories, the garden, the old-fashioned house, the fields and the woods beyond, the little stream, which came hurrying down from the mountains, where she could fish or wade as the fancy pleased her, gave her a taste of some of the joys of girlhood which she had not known when she was really a girl.

Another thing that greatly interested her was the toll-gate. If she had been allowed to do so, she would have spent the greater part of her time taking money, making change, and talking to travelers. But this her uncle would not permit. He did not object to her doing some occasional toll-gate work, and he did not wonder that she liked it, remembering how interesting it often was to himself, but he would not let her take toll indiscriminately.

So they made a regular arrangement about it. When the captain was at his meals, or shaving, or otherwise occupied, old Jane attended to the toll-gate. At ordinary times, and when any of his special friends were seen approaching, the captain collected toll himself, but when women happened to be traveling on the road, then it was arranged that Olive should go to the gate.

Two or three times it had happened that some young men of the town, hearing their sisters talk of the pretty girl who had taken their toll, had thought it might be a pleasant thing to drive out on the pike, but their money had always been taken by the captain, or else by the wooden-faced Jane, and nothing had come of their little adventures.

The garden hedge which ran alongside the road was very high.

Olive stood impatiently at the door of the little tollhouse. In one hand she held three copper cents, because she felt almost sure that the person approaching would give her a dime or two five-cent pieces.

"I never knew horses to travel so slowly as they do on this pike!" she said to herself. "How they used to gallop on those beautiful roads in France!"

In due course of time the vehicle approached near enough to the toll-gate for Olive to take an observation of its occupant. This was a middle-aged woman, dressed in black, holding a black fan. She wore a black bonnet with a little bit of red in it. Her face was small and pale, its texture and color suggesting a boiled apple dumpling. She had small eyes of which it can be said that they were of a different color from her face, and were therefore noticeable. Her lips were not prominent, and were closely pressed together as if some one had begun to cut a dumpling, but had stopped after making one incision.

This somewhat somber person leaned forward in the seat behind her young driver, and steadily stared at Olive. When the horse had passed the toll-bar the boy stopped it so that his passenger and Olive were face to face and very near each other.

"Seven cents, please," said Olive.

The cleft in the dumpling enlarged itself, and the woman spoke. "Bless my soul," she said, "are you Captain Asher's niece?"

"I am," said Olive in surprise.

"Well, well," said the other, "that just beats me! When I heard he had his niece with him I thought she was a plain girl, with short frocks and her hair plaited down her back."

Olive did not like this woman. It is wonderful how quickly likes and dislikes may be generated.

"But you see I am not," she replied. "Seven cents, please."

"Don't you suppose I know what the toll is?" said the woman in the carriage. "I'm sure I've traveled over this road often enough to know that. But what I'm thinkin' about is the difference between what I thought the captain's niece was and what she really is."

"It does not make any difference what the difference is," said Olive, speaking quickly and with perhaps a little sharpness in her voice, "all I want is for you to pay me the toll."

"I'm not goin' to pay any toll," said the other.

Olive's face flushed. "Little boy," she exclaimed, "back that horse!" As the youngster obeyed her peremptory request Olive gave a quick jerk to a rope and brought down the toll-gate bar so that it stretched itself across the road, barely missing in its downward sweep the nose of the unoffending horse. "Now," said Olive, "if you are ready to pay your toll you can go through this gate, and if you are not, you can turn round and go back where you came from."

"I'm not goin' to pay any toll," said the other, "and I don't want to go through the gate. I came to see Captain Asher.—Johnny, turn your horse a little and let me get out. Then you can stop in the shade of this tree and wait until I'm ready to go back.—I suppose the captain's in," she said to Olive, "but if he isn't, I can wait."

"Oh, he's at home," said Olive, "and, of course, if I had known you were coming to see him, I would not have asked you for your toll. This way, please," and she stepped toward a gate in the garden hedge.

"When I've been here before," said the visitor, "I always went through the tollhouse. But I suppose things is different now."

"This is the entrance for visitors," said Olive, holding open the gate.

Captain Asher had heard the voices, and had come out to his front door. He shook hands with the newcomer, and then turned to Olive, who was following her.

"This is my niece, my brother Alfred's daughter," he said, "and Olive, let me introduce you to Miss Maria Port."

"She introduced herself to me," said Miss Port, "and tried to get seven cents out of me by letting down the bar so that it nearly broke my horse's nose. But we'll get to know each other better. She's very different from what I thought she was."

"Most people are," said Captain Asher, as he offered a chair to Miss Port in his parlor, and sat down opposite to her. Olive, who did not care to hear herself discussed, quietly passed out of the room.

"Captain," said Miss Port, leaning forward, "how old is she, anyway?"

"About twenty," was the answer.

"And how long is she going to stay?"

"All summer, I hope," said Captain John.

"Well, she won't do it, I can tell you that," remarked Miss Port. "She'll get tired enough of this place before the summer's out."

"We shall see about that," said the captain, "but she is not tired yet."

"And her mother's dead, and she's wearin' no mournin'."

"Why should she?" said the captain. "It would be a shame for a young girl like her to be wearing black for two years."

"She's delicate, ain't she?"

"I have not seen any signs of it."

"What did her mother die of?"

"I never heard," said the captain; "perhaps it was the bubonic plague."

Miss Port pushed back her chair and drew her skirts about her.

"Horrible!" she exclaimed. "And you let that child come here!"

The captain smiled. "Perhaps it wasn't that," he said. "It might have been an avalanche, and that is not catching."

Miss Port looked at him seriously. "It's a great pity she's so handsome," she said.

"I don't think so; I am glad of it," replied the captain.

Miss Port heaved a sigh. "What that girl is goin' to need," she said, "is a female guardeen."

"Would you like to take the place?" asked the captain with a grin.

At that instant it might have been supposed that a certain dumpling which has been mentioned was made of very red apples and that its covering of dough was somewhat thin in certain places. Miss Port's eyes were bent for an instant upon the floor.

"That is a thing," she said, "which would need a great deal of consideration."

A sudden thrill ran through the captain which was not unlike a moment in his past career when a gentle shudder had run through his ship as its keel grazed an unsuspected sand-bar, and he had not known whether it was going to stick fast or not; but he quickly got himself into deep water again.

"Oh, she is all right," said he briskly; "she has been used to taking care of herself almost ever since she was born. And by the way, Miss Port, did you know that Mr. Easterfield is at his home?"

Miss Port was not pleased with the sudden change in the conversation, and she remembered, too, that in other days it had been the captain's habit to call her Maria.

"I did not know he had a home," she answered. "I thought it was her'n. But since you've mentioned it, I might as well say that it was about him I came to see you. I heard that he came to town yesterday, and that her carriage met him at the station, and drove him out to her house. I hoped he had stopped a minute as he drove through your toll-gate, and that you might have had a word with him, or at least a good look at him. Mercy me!" she suddenly ejaculated, as a look of genuine disappointment spread over her face; "I forgot. The coachman would have paid the toll as he went to town, and there was no need of stoppin' as they went back. I might have saved myself this trip."

The captain laughed. "It stands to reason that it might have been that way," he said, "but it wasn't. He stopped, and I talked to him for about five minutes."

The face of Miss Port now grew radiant, and she pulled her chair nearer to Captain Asher. "Tell me," said she, "is he really anybody?"

"He is a good deal of a body," answered the captain. "I should say he is pretty nearly six feet high, and of considerable bigness."

"Well!" exclaimed Miss Port, "I'd thought he was a little dried-up sort of a mummy man that you might hang up on a nail and be sure you'd find him when you got back. Did he talk?"

"Oh, yes," said the captain, "he talked a good deal."

"And what did he tell you?"

"He did not tell me anything, but he asked a lot of questions."

"What about?" said Miss Port quickly.

"Everything. Fishing, gunning, crops, weather, people."

"Well, well!" she exclaimed. "And don't you suppose his wife could have told him all that, and she's been livin' here—this is the second summer. Did he say how long he's goin' to stay?"

"No."

"And you didn't ask him?"

"I told you he asked the questions," replied the captain.

"Well, I wish I'd been here," Miss Port remarked fervently. "I'd got something out of him."

"No doubt of that," thought the captain, but he did not say so.

"If he expects to pass himself off as just a common man," continued Miss Port, "that's goin' to spend the rest of his summer here with his family, he can't do it. He's first got to explain why he never came near that young woman and her two babies for the whole of last summer, and, so far as I've heard, he was never mentioned by her. I think, Captain Asher, that for the sake of the neighborhood, if you don't care about such things yourself, you might have made use of this opportunity. As far as I know, you're the only person in or about Glenford that's spoke to him."

The captain smiled. "Sometimes, I suppose," said he, "I don't say enough, and sometimes I say too much, but—"

"Then I wish he'd struck you more on an average," interrupted Miss Port. "But there's no use talkin' any more about it. I hired a horse and a carriage and a boy to come out here this mornin' to ask you about that man. And what's come of it? You haven't got a single thing to tell anybody except that he's big."

The captain changed the subject again. "How is your father?" he asked.

"Pop's just the same as he always is," was the answer. "And now, as I don't want to lose the whole of the seventy-five cents I've got to pay, suppose you call in that niece of yours, and let me have a talk with her. Perhaps I can get something interesting out of her."

The captain left the room, but he did not move with alacrity. He found Olive with a book in a hammock at the back of the house. When he told her his errand she sat up with a sudden bounce, her feet upon the ground.

"Uncle," she said, "isn't that woman a horrid person?"

The captain was a merry-minded man, and he laughed. "It is pretty hard for me to answer that question," said he; "suppose you go in and find out for yourself."

Olive hesitated; she was a girl who had a very high opinion of herself and a very low opinion of such a person as this Miss Port seemed to be. Why should she go in and talk to her? Still undecided, she left the hammock and made a few steps toward the house. Then, with a sudden exclamation, she stopped and dropped her book.

"Buggy coming," she exclaimed, "and that thing is running to take the toll!" With these words she started away with the speed of a colt.

An approaching buggy was on the road; Miss Maria Port, walking rapidly, had nearly reached the back door of the tollhouse when Olive swept by her so closely that the wind of her fluttering garments almost blew away the breath of the elder woman.

"Seven cents!" cried Olive, standing in the covered doorway, but she might have saved herself the trouble of repeating this formula, for the man in the buggy was not near enough to hear her.

When Olive saw it was a man, she turned, and perceiving her uncle approaching the tollhouse, she hurried by him up the garden path, looking neither to the right nor to the left.

"A pretty girl that is of yours!" exclaimed Miss Port. "She might just as well have slapped me in the face!"

"But what were you going to do in here?" asked Captain Asher. "You know that's against the rules."

"The rules be bothered," replied the irate Maria. "I thought it was Mr. Smiley. He's been away from his parish for a week, and there are a good many things I want to ask him."

"Well, it is the Roman Catholic priest from Marlinsville," said Captain Asher, "and he wouldn't tell you anything if you asked him."

The captain had a cheerful little chat with the priest, who was one of his most valued road friends; and when he returned to his garden he found Miss Port walking up and down the main path in a state of agitation.

"I should think," said she, "that the company would have something to say about your takin' up your time talkin' to people on the road. I've heard that sometimes they get out, and spend hours talkin' and smokin' with you. I guess that's against the rules."

"It is all right between the company and me," replied the captain. "You know I am a stockholder in a small way."

"You are!" exclaimed Miss Port. "Well, I've got somethin' by comin' here, anyway." Stowing away this bit of information in regard to the captain's resources in her mind for future consideration, she continued: "I don't think much of that niece of your'n. Has she never lived anywhere where the people had good manners?"

Olive, who had gone to her room in order to be out of the way of this queer visitor, now sat by an upper window, and it was impossible that she should fail to hear this remark, made by Miss Port in her most querulous tones. Olive immediately left the window, and sat down on the other side of the room.

"Good manners!" she ejaculated, and fell to thinking. Her present situation had suddenly presented itself to her in a very different light from that in which she had previously regarded it. She was living in a very plain house in a very plain way, with a very plain uncle who kept a tollhouse; but she liked him; and, until this moment, she had liked the life. But now she asked herself if it were possible for her longer to endure it if she were to be condemned to intercourse with people like that thing down in the garden. If her uncle's other friends in Glenford were of that grade she could not stay here. She smiled in spite of her irritation as she thought of the woman's words—"Anywhere where the people had good manners."

Good manners, indeed! She remembered the titled young officers in Germany with whom she had talked and danced when she was but seventeen years old, and who used to send her flowers. She remembered the people of rank in the army and navy and in the state who used to invite her mother and herself to their houses. She remembered the royal prince who had wished to be presented to her, and whose acquaintance she had declined because she did not like what she had heard of him. She remembered the good friends of her father in Europe and America, ladies and gentlemen of the army and navy. She remembered the society in which she had mingled when living with her Boston aunt during the past winter. Then she thought of Miss Port's question. Good manners, indeed!

"Well," said the perturbed Maria, after having been informed by the captain that his niece was accustomed to move in the best circles, "I don't want to go into the house again, for if I was to meet her, I'm sure I couldn't keep my temper. But I'll say this to you, Captain Asher, that I pity the woman that's her guardeen. And now, if you'll help my boy turn round so he won't upset the carriage, I'll be goin'. But before I go I'll just say this, that if you'd been in the habit of takin' advantage of the chances that come to you, I believe that you'd be a good deal better off than you are now, even if you do own shares in the turnpike company."

It was not difficult for the captain to recognize some of the chances to which she alluded; one of them she herself had offered him several times.

"Oh, I am very well off as I am," he answered, "but perhaps some day I may have something to tell you of the Easterfields and about their doings up on the mountain."

"About her doin's, you might as well say," retorted Miss Port. "No matter what you tell me, I don't believe a word about his ever doin' anything." With this she walked to the little phaeton, into which the captain helped her.

"Uncle John," said Olive, a few minutes later, "are there many people like that in Glenford?"

"My dear child," said the captain, "the people in Glenford, the most of them, I mean, are just as nice people as you would want to meet. They are ladies and gentlemen, and they are mighty good company. They don't often come out here, to be sure, but I know most of them, and I ought to be ashamed of myself that I have not made you acquainted with them before this. As to Maria Port, there is only one of her in Glenford, and, so far as I know, there isn't another just like her in the whole world. Now I come to think of it," he continued, "I wonder why some of the young people have not come out to call on you. But if that Maria Port has been going around telling them that you are a little girl in short frocks it is not so surprising."

"Oh, don't bother yourself, Uncle John, about calls and society," said Olive. "If you can only manage that that woman takes the shunpike whenever she drives this way, I shall be perfectly satisfied with everything just as it is."

On the side of the mountain, a few miles to the west of the gap to which the turnpike stretched itself, there was a large estate and a large house which had once belonged to the Sudley family. For a hundred years or more the Sudleys had been important people in this part of the country, but it had been at least two decades since any of them had lived on this estate. Some of them had gone to cities and towns, and others had married, or in some other fashion had melted away so that their old home knew them no more.

Although it was situated on the borders of the Southern country, the house, which was known as Broadstone, from the fact that a great flat rock on the level of the surrounding turf extended itself for many feet at the front of the principal entrance, was not constructed after ordinary Southern fashions. Some of the early Sudleys were of English blood and proclivities, and so it was partly like an English house; some of them had taken Continental ideas into the family, and there was a certain solidity about the walls; while here and there the narrowness of the windows suggested southern Europe. Some parts of the great stone walls had been stuccoed, and some had been whitewashed. Here and there vines climbed up the walls and stretched themselves under the eaves. As the house stood on a wide bluff, there was a lawn from which one could see over the tree tops the winding river sparkling far below. There were gardens and fields on the open slopes, and beyond these the forests rose to the top of the mountains.

The ceilings of the house were high, and the halls and rooms were wide and airy; the trees on the edge of the woods seemed always to be rustling in a wind from one direction or another, and a lady; Mrs. Easterfield; who several years before had been traveling in that part of the country; declared that Broadstone was the most delightful place for a summer residence that she had ever seen, either in this country or across the ocean. So, with the consent and money of her husband, she had bought the estate the summer before the time of our story, and had gone there to live.

Mr. Easterfield was what is known as a railroad man, and held high office in many companies and organizations. When his wife first went to Broadstone he was obliged to spend the summer in Europe, and had agreed with her that the estate on the mountains would be the best place for her and the two little girls while he was away. This state of affairs had occasioned a good deal of talk, especially in Glenford, a town with which the Easterfields had but little to do, and which therefore had theorized much in order to explain to its own satisfaction the conduct of a comparatively young married woman who was evidently rich enough to spend her summers at any of the most fashionable watering-places, but who chose to go with her young family to that old barracks of a house, and who had a husband who never came near her or his children, and who, so far as the Glenford people knew, she never mentioned.

Mrs. Margaret Easterfield was a very fine woman, both to look at and to talk to, but she did not believe that her duty to her fellow-beings demanded that she should devote her first summer months at her new place to the gratification of the eyes and ears of her friends and acquaintances, so she had gone to Broadstone with her family—all females—with servants enough, and for the whole of the summer they had all been very happy.

But this summer things were going to be a little different at Broadstone, for Mrs. Easterfield had arranged for some house parties. Her husband was very kind and considerate about her plans, and promised her that he would make one of the good company at Broadstone whenever it was possible for him to do so.

So now it happened that he had come to see his wife and children and the house in which they lived; and, having had some business at a railroad center in the South, he had come through Glenford, which was unusual, as the intercourse between Broadstone and the great world was generally maintained through the gap in the mountains.

With his wife by his side and a little girl on each shoulder, Mr. Tom Easterfield walked through the grounds and the gardens and out on the lawn, and looked down over the tops of the trees upon the river which sparkled far below, and he said to his wife that if she would let him do it he would send a landscape-gardener, with a great company of Italians, and they would make the place a perfect paradise in about five days.

"It could be ruined a great deal quicker by an army of locusts," she said, "and so, if you do not mind, I think I will wait for the locusts."

It was not time yet for any of the members of the house parties to make their appearance, and it was the general desire of his family that Mr. Easterfield should remain until some of the visitors arrived, but he could not gratify them. Three days after his arrival he was obliged to be in Atlanta; and so, soon after breakfast one fine morning, the Easterfield carriage drove over the turnpike to the Glenford station, Mr. and Mrs. Easterfield on the back seat, and the two little girls sitting opposite, their feet sticking out straight in front of them.

When they stopped at the toll-gate Captain Asher came down to collect the toll—ten cents for two horses and a carriage. Olive was sitting in the little arbor, reading. She had noticed the approaching equipage and saw that there was a lady in it, but for some reason or other she was not so anxious as she had been to collect toll from ladies. If she could have arranged the matter to suit herself she would have taken toll from the male travelers, and her Uncle John might attend to the women; she did not believe that men would have such absurd ideas about people or ask ridiculous questions.

There was no conversation at the gate on this occasion, for the carriage was a little late, but as it rolled on Mrs. Margaret said to Mr. Tom:

"It seems to me as though I have just had a glimpse of Dresden. What do you suppose could have suggested that city to me?"

Mr. Tom could not imagine, unless it was the dust. She laughed, and said that he had dust and ballast and railroads on the brain; and when the oldest little girl asked what that meant, Mrs. Margaret told her that the next time her father came home she would make him sit down on the floor and then she would draw on that great bald spot of his head, which they had so often noticed, a map of the railroad lines in which he was concerned, and then his daughters would understand why he was always thinking of railroad-tracks and that sort of thing with the inside of his head, which, as she had told them, was that part of a person with which he did his thinking.

"Don't they sell some sort of annual or monthly tickets for this turnpike?" asked Mr. Tom. "If they do, you would save yourself the trouble of stopping to pay toll and make change."

"I so seldom use this road," she said, "that it would not be worth while. One does not stop on returning, you know."

But notwithstanding this speech, when Mrs. Easterfield returned from the Glenford station, one little girl sitting beside her and the other one opposite, both of them with their feet sticking out, she ordered her coachman to stop when he reached the toll-gate.

Olive was still sitting in the arbor, reading. The captain was not visible, and the wooden-faced Jane, noticing that the travelers were a lady and two little girls, did not consider that she had any right to interfere with Miss Olive's prerogatives; so that young lady felt obliged to go to the toll-gate to see what was wanted.

"You know you do not have to pay going back," she said.

"I know that," answered Mrs. Easterfield, "but I want to ask about tickets or monthly payments of toll, or whatever your arrangements are for that sort of thing."

"I really do not know," said Olive, "but I will go and ask about it."

"But stop one minute," exclaimed Mrs. Easterfield, leaning over the side of the carriage. "Is it your father who keeps this toll-gate?"

For some reason or other which she could not have explained to herself, Olive felt that it was incumbent upon her to assert herself, and she answered: "Oh, no, indeed. My father is Lieutenant-Commander Alfred Asher, of the cruiser Hopatcong."

Without another word Mrs. Easterfield pushed open the door of the carriage and stepped to the ground, exclaiming: "As I passed this morning I knew there was something about this place that brought back to my mind old times and old friends, and now I see what it was; it was you. I caught but one glimpse of you and I did not know you. But it was enough. I knew your father very well when I was a girl, and later I was with him and your mother in Dresden. You were a girl of twelve or thirteen, going to school, and I never saw much of you. But it is either your father or your mother that I saw in your face as you sat in that arbor, and I knew the face, although I did not know who owned it. I am Mrs. Easterfield, but that will not help you to know me, for I was not married when I knew your father."

Olive's eyes sparkled as she took the two hands extended to her. "I don't remember you at all," she said, "but if you are the friend of my father and mother—"

"Then I am to be your friend, isn't it?" interrupted Mrs. Easterfield.

"I hope so," answered Olive.

"Now, then," said Mrs. Easterfield, "I want you to tell me how in the world you come to be here."

There were two stools in the tollhouse, and Olive, having invited her visitor to seat herself on the better one, took the other, and told Mrs. Easterfield how she happened to be there.

"And that handsome elderly man who took the toll this morning is your uncle?"

"Yes, my father's only brother," said Olive.

"A good deal older," said Mrs. Easterfield.

"Oh, yes, but I do not know how much."

"And you call him captain. Was he also in the navy?"

"No," said Olive, "he was in the merchant service, and has retired. It seems queer that he should be keeping a toll-gate, but my father has often told me that Uncle John does not care for appearances, and likes to do things that please him. He likes to keep the tollhouse because it brings him in touch with the world."

"Very sensible in him," said Mrs. Easterfield. "I think I would like to keep a toll-gate myself."

Captain Asher had seen the carriage stop, and knew that Mrs. Easterfield was talking to Olive, but he did not think himself called upon to intrude upon them. But now it was necessary for him to go to the tollhouse. Two men in a buggy with a broken spring and a coffee bag laid over the loins of an imperfectly set-up horse had been waiting for nearly a minute behind Mrs. Easterfield's carriage, desiring to pay their toll and pass through. So the captain went out of the garden-gate, collected the toll from the two men, and directed them to go round the carriage and pass on in peace, which they did.

Then Mrs. Easterfield rose from her stool, and approached the tollhouse door, and, as a matter of course, the captain was obliged to step forward and meet her. Olive introduced him to the lady, who shook hands with him very cordially.

"I have found the daughter of an old friend," said she, and then they all went into the tollhouse again, where the two ladies reseated themselves, and after some explanatory remarks Mrs. Easterfield said:

"Now, Captain Asher, I must not stay here blocking up your toll-gate all the morning, but I want to ask of you a very great favor. I want you to let your niece come and make me a visit. I want a good visit—at least ten days. You must remember that her father and I, and her mother, too, were very good friends. Now there are so many things I want to talk over with Miss Olive, and I am sure you will let me have her just for ten short days. There are no guests at Broadstone yet, and I want her. You do not know how much I want her."

Captain Asher stood up tall and strong, his broad shoulders resting against the frame of the open doorway. It was a positive delight to him to stand thus and look at such a beautiful woman. So far as he could see, there was nothing about her with which to find fault. If she had been a ship he would have said that her lines were perfect, spars and rigging just as he would have them. In addition to her other perfections, she was large enough. The captain considered himself an excellent judge of female beauty, and he had noticed that a great many fine women were too small. With Olive's personal appearance he was perfectly satisfied, although she was slight, but she was young, and would probably expand. If he had had a daughter he would have liked her to resemble Mrs. Easterfield, but that feeling did not militate in the least against Olive. In his mind it was not necessary for a niece to be quite as large as a daughter ought to be.

"But what does Olive say about it?" he asked.

"I have not been asked yet," replied Olive, "but it seems to me that I—"

"Would like to do it," interrupted Mrs. Easterfield. "Now, isn't that so, dear Olive?"

The girl looked at the captain. "It depends upon what you say about it, Uncle John."

The captain slightly knitted his brows. "If it were for one night, or perhaps a couple of days," he said, "it would be different. But what am I to do without Olive for nearly two weeks? I am just beginning to learn what a poor place my house would be without her."

At this minute a man upon a rapidly trotting pony stopped at the toll-gate.

"Excuse me one minute," continued the captain, "here is a person who can not wait," and stepping outside he said good morning to a bright-looking young fellow riding a sturdy pony and wearing on his cap a metal plate engraved "United States Rural Delivery."

The carrier brought but one letter to the tollhouse, and that was for Captain Asher himself. As the man rode away the captain thought he might as well open his letter before he went back. This would give the ladies a chance to talk further over the matter. He read the letter, which was not long, put it in his pocket, and then entered the tollhouse. There was now no doubt or sign of disturbance on his features.

"I have considered your invitation, madam," said he, "and as I see Olive wants to visit you, I shall not interfere."

"Of course she does," cried Mrs. Easterfield, springing to her feet, "and I thank you ever and ever so much, Captain Asher. And now, my dear," said she to Olive, "I am going to send the carriage for you to-morrow morning." And with this she put her arm around the girl and kissed her. Then, having warmly shaken hands with the captain, she departed.

"Do you know, Uncle John," said Olive, "I believe if you were twenty years older she would have kissed you."

With a grim smile the captain considered; would he have been willing to accept those additional years under the circumstances? He could not immediately make up his mind, and contented himself with the reflection that Olive did not think him old enough for the indiscriminate caresses of young people.

When Olive came down to breakfast the next morning she half repented that she had consented to go away and leave her uncle for so long a time. But when she made known her state of mind the captain laughed at her.

"My child," said he, "I want you to go. Of course, I did not take to the notion at first, but I did not consider then what you will have to tell when you come home. The people of Glenford will be your everlasting debtors. It might be a good thing to invite Maria Port out here. You could give her the best time she ever had in her life, telling her about the Broadstone people."

"Maria Port, indeed!" said Olive. "But we won't talk of her. And you really are willing I should go?"

"I speak the truth when I say I want you to go," replied the captain.

Whereupon Olive assured him that he was truly a good uncle.

After the Easterfield carriage had rolled away with Olive alone on the back seat, waving her handkerchief, the captain requested Jane to take entire charge of the toll-gate for a time; and, having retired to his own room, he took from his pocket the letter he had received the day before.

"I must write an answer to this," he said, "before the postman comes."

The letter was from one of the captain's old shipmates, Captain Richard Lancaster, the best friend he had had when he was in the merchant service. Captain Lancaster had often been asked by his old friend to visit him at the toll-gate, but, being married and rheumatic, he had never accepted the invitation. But now he wrote that his son, Dick, had planned a holiday trip which would take him through Glenford, and that, if it suited Captain Asher, the father would accept for the son the long-standing invitation. Captain Lancaster wrote that as he could not go himself to his old friend Asher, the next best thing would be for his son to go, and when the young man returned he could tell his father all about Captain Asher. There would be something in that like old times. Besides, he wanted his former shipmate to know his son Dick, who was, in his eyes, a very fine young fellow.

"There never was such a lucky thing in the world," said Captain Asher to himself, when he had finished rereading the letter. "Of course, I want to have Dick Lancaster's son here, but I could not have had him if Olive had been here. But now it is all right. The young fellow can stay here a few days, and he will be gone before she gets back. If I like him I can ask him to come again; but that's my business. Handsome women, like that Mrs. Easterfield, always bring good luck. I have noticed that many and many a time."

Then he set himself to work to write a letter to invite young Richard Lancaster to spend a few days with him.

For the rest of that day, and the greater part of the next, Captain Asher gave a great deal of thinking time to the consideration of the young man who was about to visit him, and of whom, personally, he knew very little. He was aware that Captain Lancaster had a son and no other children, and he was quite sure that this son must now be a grown-up young man. He remembered very well that Captain Lancaster was a fine young fellow when he first knew him, and he did not doubt at all that the son resembled the father. He did not believe that young Dick was a sailor, because he and old Dick had often said to each other that if they married their sons should not go to sea. Of course he was in some business; and Captain Lancaster ought to be well able to give him a good start in life; just as able as he himself was to give Olive a good start in housekeeping when the time came.

"Now, what in the name of common sense," ejaculated Captain Asher, "did I think of that for? What has he to do with Olive, or Olive with him?" And then he said to himself, thinking of the young man in the bosom of his family and without reference to anybody outside of it: "Yes, his father must be pretty well off. He did a good deal more trading than ever I did. But after all, I don't believe he invested his money any better than I did mine, and it is just as like as not if we were to show our hands, that Olive would get as much as Dick's son. There it is again. I can't keep my mind off the thing." And as he spoke he knocked the ashes out of his pipe, and began to stride up and down the garden walk; and as he did so he began to reproach himself.

What right had he to think of his niece in that way? It was not doing the fair thing by her father, and perhaps by her, for that matter. For all he knew she might be engaged to somebody out West or down East, or in some other part of the world where she had lived. But this idea made very little impression on him. Knowing Olive as he did, he did not believe that she was engaged to anybody anywhere; he did not want to think that she was the kind of girl who would conceal her engagement from him, or who could do it, for that matter. But, everything considered, he was very glad Olive had gone to Broadstone, for, whatever the young fellow might happen to be, he wanted to know all about him before Olive met him.