To an American of analytical tendencies a few years in

the Philippines present not only an interesting study of Filipino life,

but a novel consciousness of our own. The affairs of these people are

so simple where ours are complex, so complex where ours are simple,

that one’s angle of view is considerably enlarged.

The general construction of society is mediæval and

aristocratic. The aristocracy, with the exception of a few wealthy

brewers and cigar manufacturers of Manila, is a land-holding one. There

is practically no bourgeoisie—no commercial class—between

the rich and the poor. In Manila and all the large coast towns trade is

largely in the hands of foreigners, chiefly Chinese, some few of whom

have become converted to the Catholic faith, and established themselves

permanently [233]in the country;—all of whom have found

Filipino helpmates, either with or without the sanction of the Church,

and have added their contingent of half-breeds, or mestizos, to

the population.

The land-owning aristocracy, though it must have been in possession

of its advantages for several generations, seems deficient in jealous

exclusiveness on the score of birth. I do not remember to have heard

once here the expression “of good family,” as we hear it in

America, and especially in the South. But I have heard “He is a

rich man” so used as to indicate that this good fortune carried

with it unquestioned social prerogative. Yet there must be some

clannishness based upon birth, for your true Filipino never repudiates

his poor relations or apologizes for them. At every social function

there is a crowd of them in all stages of modest apparel, and with

manners born of social obscurity, asserting their right to be

considered among the elect. I am inclined to think that Filipinos

concern themselves with the present rather than the past, and that the

parvenu finds it even easier to win his way with them than with

us. Even under Spanish rule poor men had a chance, and sometimes rose

to the top. I remember the case, in particular, of one family which

claimed and held social leadership in Capiz. Its head was a

long-headed, cautious, shrewd old fellow, with so many Yankee traits

that I sometimes almost forgot, and addressed him in English. My

landlady, who was an heiress in her own right, and the last of a family

of former repute, told me that the old financier came to Capiz

“poor as wood.” She [234]did not use that homely

simile, however, but the typical Filipino statement that his pantaloons

were torn. She took me behind a door to tell me, and imparted the

information in a whisper, as if she were afraid of condign punishment

if overheard.

“Money talks” in the Philippines just as blatantly as it

does in the United States. In addition to the social halo imparted by

its possession, there is a condition grown out of it, known locally as

“caciquism.” Caciquism is the social and political prestige

exercised by a local man or family. There are examples in America,

where every village owns its leading citizen’s and its leading

citizen’s wife’s influence. Booth Tarkington has pictured

an American cacique in “The Conquest of Canaan.” Judge Pike

is a cacique. His power, however, is vested in his capacity to deceive

his fellowmen, in the American’s natural love for what he regards

as an eminent personality, and his clinging to an ideal.

A Filipino cacique is quite a different being. He owes his prestige

to fear—material fear of the consequences which his wealth and

power can bring down on those that cross him. He does not have to play

a hypocritical role. He need neither assume to be, nor be, a saint in

his private or public life. He must simply be in control of enough

resources to attach to him a large body of relatives and friends whose

financial interests are tied up with his. Under the Spanish regime he

had to stand in by bribery with the local governor. Under the American

regime, with its illusions of democracy, he simply points to his

clientèle [235]and puts forward the plea that he

is the natural voice of the people. The American Government, helpless

in its great ignorance of people, language, and customs, is eager to

find the people’s voice, and probably takes him at his word.

Fortified by Government backing, he starts in to run his province

independently of law or justice, and succeeds in doing so. There are no

newspapers, there is no real knowledge among the people of what popular

rights consist in, and no idea with which to combat his usurpations.

The men whom he squeezes howl, but not over the principle. They simply

wait the day of revolution. Even where there is a real public sentiment

which condemns the tyrant, it is half the time afraid to assert itself,

for the tyrant’s first defence is that they oppose him because he

is a friend of the American Government. Local justice of the peace

courts are simply farcical, and most of the cacique’s violations

of right keep him clear at least of the courts of first instance, where

the judiciary, Filipino or American, is reliable. Thus our Government,

in its first attempts to introduce democratic institutions, finds

itself struggling with the very worst evil of democracy long before it

can make the virtues apparent.

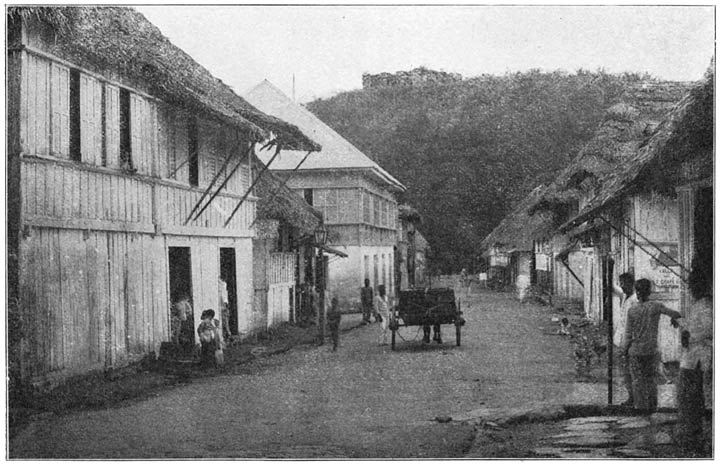

The poor people among the Filipinos live in a poverty, a misery, and

a happiness inconceivable to our people who have not seen it. Their

poverty is real—not only relative. Their houses are barely a

covering from rain or sun. A single rude bamboo bedstead and a stool or

two constitute their furniture. There is an earthen water jar, another

earthen pot for cooking [236]rice, a bolo for cutting, one or

two wooden spoons, and a cup made of cocoanut shells. The stove

consists of three stones laid under the house, or back of it, where a

rice-pot may be balanced over the fire laid between. There are no

tables, no linen, no dishes, no towels. The family eat with their

fingers while sitting about on the ground with some broken banana

leaves for plates. Coffee, tea, and chocolate are unknown luxuries to

them. Fish and rice, with lumps of salt and sometimes a bit of fruit,

constitute their only diet. In the babies this mass of undigested

half-cooked rice remains in the abdomen and produces what is called

“rice belly.” In the adults it brings beriberi, from which

they die quickly. They suffer from boils and impure blood and many skin

diseases. Consumption is rife, and rheumatism attacks old and young

alike. They are tormented by gnats and mosquitoes, and frequently to

rid themselves of the pests build fires under the house and sleep away

the hot tropical night in the smoke. While the upper classes are

abstemious, the lower orders drink much of the native vino,

which is made from the sap of cocoanut and nipa trees, and the men are

often brutal to women and children.

I think the most hopeful person must admit that this is an

enumeration of real and not fancied evils, that the old saw about

happiness and prosperity being relative terms is not applicable. The

Filipino laborer is still far below even the lowest step of the

relative degree of prosperity and happiness. Yet in spite of these ills

he is happy because he has not developed enough to achieve either

self-pity or self-analysis. He [237]bears his pain, when it

comes, as a dumb animal does, and forgets it as quickly when it goes.

When the hour of death descends, he meets it stoically, partly because

physical pain dulls his senses, partly because the instinct of fatalism

is there in spite of his Catholicism.

Of course this poverty-stricken condition is largely his own fault.

He has apparently an ineradicable repugnance to continued labor. He

does not look forward to the future. Fathers and mothers will sit the

whole day playing the guitar and singing or talking, after the fashion

of the country, with not a bite of food in the house. When their own

desires begin to reinforce the clamors of the children, they will start

out at the eleventh hour to find an errand or an odd bit of work. There

may be a single squash on the roof vine waiting to be plucked and to

yield its few centavos, or they can go out to the beach and dig a few

cents’ worth of clams.

The more intelligent of the laboring class attach themselves as

cliente to the rich land-holding families. They are by no means

slaves in law, but they are in fact; and they like it. The men are

agricultural laborers; the women, seamstresses, house servants, and wet

nurses, and they also do the beautiful embroideries, the hat-plaiting,

the weaving of piña, sinamay, and jusi, and the other local

industries which are carried on by the upper class. The poor themselves

have nothing to do with commerce; that is in the hands of the

well-to-do.

As the children of the clientèle grow up, they are

[238]scattered out among the different branches of

the ruling family as maids and valets. In a well-to-do Filipino family

of ten or twelve children, there will be a child servant for every

child in the house. The little servants are ill-fed creatures (for the

Filipinos themselves are merciless in what they exact and parsimonious

in what they give), trained at seven or eight years of age to look

after the room, the clothing, and to be at the beck and call of another

child, usually a little older, but ofttimes younger than themselves.

They go to school with their little masters and mistresses, carry their

books, and play with them. For this they receive the scantiest dole of

food on which they can live, a few cast-off garments, and a stipend of

a medio-peso (twenty-five cents cents U.S. currency) per annum, which

their parents collect and spend. Parents and child are satisfied,

because, little as they get, it is certain. Parents especially are

satisfied, because thus do they evade the duties and responsibilities

of parenthood.

It was at first a source of wonder to me how the rich man came out

even on his scores of retainers, owing to their idleness and the

demands for fiestas which he is compelled to grant. But he does succeed

in getting enough out of them to pay for the unhulled rice he gives

them, and he more than evens up on the children. If ever there was a

land where legislation on the subject of child labor is needed, it is

here. Children are overworked from infancy. They do much of the work of

the Islands, and the last drop of energy and vitality is gone before

they reach manhood or womanhood. [239]Indeed, the first privilege

of manhood to them is to quit work.

The feeling between these poor Filipinos and their so-called

employers is just what the feeling used to be between Southerners and

their negroes. The lower-class man is proud of his connection with the

great family. He guards its secrets and is loyal to it. He will fight

for it, if ordered, and desist when ordered.

The second house I lived in in Capiz was smaller than the first, and

had on the lower floor a Filipino family in one room. I demanded that

they be ejected if I rented the house, but the owner begged me to

reconsider. They were, she said, old-time servants of hers to whom she

felt it her duty to give shelter. They had always looked after her

house and would look after me.

I yielded to her insistence, but doubtingly. In six weeks I was

perfectly convinced of her wisdom and my foolishness. Did it rain,

Basilio came flying up to see if the roof leaked. If a window stuck and

would not slide, I called Basilio. For the modest reward of two pesos a

month (one dollar gold) he skated my floors till they shone like

mirrors. He ran errands for a penny or two. His wife would embroider

for me, or wash a garment if I needed it in a hurry. If I had an errand

which took me out nights, Basilio lit up an old lantern, unsolicited,

and went ahead with the light and a bolo. If a heavy rain came up when

I was at school, he appeared with my mackintosh and rubbers. And while

a great many small coins went from me to him, I could never see that

the pay was proportional to [240]his care. Yet there was no

difficulty in comprehending it. Pilar (my landlady) had told him to

take care of me, and he was obeying orders. If she had told him to come

up and bolo me as I slept, he would have done it unhesitatingly.

The result of American occupation has been a rise in the price of

agricultural labor, and in the city of Manila in all labor. But in the

provinces the needle-woman, the weaver, and the house servant work

still for inconceivably small prices, while there has been a decided

rise in the price of local manufactures. Jusi, which cost three dollars

gold a pattern in 1901, now costs six and nine dollars. Exquisite

embroideries on piña, which is thinner than bolting cloth, have

quadrupled their prices, but the provincial women servants, who weave

the jusi and do the embroidering, still work for a few cents a day and

two scanty meals.

When I arrived here a seamstress worked nine hours a day for twenty

cents gold and her dinner. Now in Manila a seamstress working for

Americans receives fifty cents gold and sometimes seventy-five cents

and her dinner, though the Spanish, Filipinos, and Chinese pay less. In

the province of Capiz twelve and a half cents gold per day for a

seamstress is the recognized price for an American to pay—natives

get one for less. A provincial Filipino pays his coachman two and a

half dollars gold a month, and a cook one dollar and a half. An

American for the same labor must pay from four to eight dollars for the

cook and three to six dollars for the coachman. As before stated, the

[241]subordinate servants in a Filipino house cost

next to nothing, because of the utilization of child labor.

A provincial Filipino can support quite an establishment, and keep a

carriage on an income of forty dollars gold a month where to an

American it would cost sixty or eighty dollars. This is due partly to

our own consumption of high-priced tinned foods, partly to the better

price paid for labor, but chiefly to our desire to feed our servants

into good healthy condition. We not only see that they have more food,

but we look more closely to its variety and nutritious qualities. We

employ adults and demand more labor, because our housekeeping is more

complex than Filipino housekeeping, and we expect to employ fewer

servants than Filipinos do.

The Filipinos, the Spanish, and even the English who are settled

here cling to mediæval European ideas in the matter of service.

If they have any snobbish weakness for display, it is in the number of

retainers they can muster. Just as in our country rural prosperity is

evinced by the upkeep of fences and buildings, the spic and span new

paint, and the garish furnishings, here it is written in the number of

servants and hangers-on. The great foreign trading firms like to boast

of the tremendous length of their pay rolls. They would rather employ

four hundred underworked mediocrities at twenty pesos a month than half

a hundred abilities at four times that amount. The land-holders like to

think of the mouths they are responsible for feeding so very poorly,

and the busy housewife jingles her keys from weaving-room to

[242]embroidery frame, from the little tienda

on the ground floor, where she sells vino, cigars, and

betel-nut, to the extemporized bakery in the kitchen, where they are

making rice cakes and taffy candy, which an old woman will presently

hawk about the streets for her.

One of the curious things here is the multiplicity of resource which

the rich classes possess. A rich land-holder will have his rice fields,

sugar mill, vino factory, and cocoanut and hemp plantations. He will

own a fish corral or two, and be one of the backers of a deep-sea

fishing outfit. He speculates a little in rice, and he may have some

interest in pearl fisheries. On a bit of land not good for much else he

has the palm tree, which yields buri for making mats and sugar

bags. His wife has a little shop, keeps several weavers at work, and an

embroidery woman or two. If she goes on a visit to Manila, the day

after her return her servants are abroad, hawking novelties in the way

of fans, knick-knacks, bits of lace, combs, and other things which she

has picked up to earn an honest penny. If a steamer drops in with a

cargo of Batangas oranges, she invests twenty or thirty pesos, and has

her servants about carrying the trays of fruit for sale. According to

her lights, which are not hygienic, she is a good housekeeper and a

genuine helpmeet. She keeps every ounce of food under lock and key, and

measures each crumb that is used in cooking. She keeps the housekeeping

accounts, handles the money, never pries into her husband’s

affairs, bears him a child every year, and is content, in return for

all this devotion, with an ample supply of pretty clothes and her

jewels. [243]She herself does not work, busy as she is, and

it speaks well for the faith and honor of the Filipino people that she

can secure labor in plenty to do all these things for her, to handle

moneys and give a faithful account of them. It is pitiful to see how

little the Filipino laboring class can do for itself, how dependent it

is upon the head of its superiors, and how content it is to go on

piling up wealth for them on a mere starvation dole.

As before said, the laboring man who attaches himself to a great

family does so because it gives him security. He is nearly always in

debt to it, but if he is sick and unable to work he knows his rice will

come in just the same. Under the old Spanish system, a servant in debt

could not quit his employer’s service till the debt was paid. The

object of an employer was to get a man in debt and keep him so, in

which case he was actually, although not nominally, a slave. While this

law is no longer in force, probably not ten per cent of the laboring

population realize it. They know that an American cannot hold them in

his employ against their will, but they do not know that this is true

of Filipinos and Spaniards. Nor is the upper class anxious to have them

informed. The poor frequently offer their children or their younger

brothers and sisters to work out their debts.

Children are sold here also. Twice in my first year at Capiz, I

refused to buy small children who were offered for sale by their

parents lest the worse evil of starvation should befall them; and once,

on my going into a friend’s house, she showed me a child of three

[244]or four years that she had bought for five

pesos. She remarked that it was a pity to let the child starve, and

that in a year or two its labor would more than pay for its keep.

Filipinos who have capital enough all keep one or more pigs. These

are yard scavengers, and, as sanitary measures are little observed by

this race, have access to filth that makes the thought of eating their

flesh exceedingly repulsive. When the owners are ready to kill,

however, the pig is brought upstairs into the kitchen, where it lives

luxuriously on boiled rice, is bathed once a day, and prepared for

slaughter like a sacrificial victim. If you are personally acquainted

with a pig of this sort and know the day set for his decease, you may

send your servant out to buy fresh pork; otherwise you had better stick

to chicken and fish.

Before the Insurrection, when the rinderpest had not yet destroyed

the herds, beef cattle were plenty, and meat was cheap enough for even

the poorest to enjoy. A live goat, full grown, was not worth more than

a peso (fifty cents gold). Now there are practically no beef cattle at

all, so the only meat available is goats’ flesh, which is sold at

from twenty to sixty cents a pound (ten to thirty cents gold).

Americans living in the provinces rely largely upon chicken, though in

the coast towns there is always plenty of delicious fish. There are

also oysters (not very good), clams, crabs, shrimps, and crayfish.

One of the most irritating features of housekeeping here is the lack

of any fixed value, especially for market produce. There are no grocery

stores, every article [245]must be chaffered over, and is

valued according to the owner’s pressing needs, his antipathy for

Americans, or his determination to get everything he can.

You may be driving in the country and see a flock of chickens

feeding under or near a house. You ask the price. The owner has just

dined. There is still enough palay (unhulled rice) to furnish

the evening meal. He has no pressing need of money, and he

doesn’t want to disturb himself to run down chickens. His fowls

simply soar as to price. They are worth anywhere from seventy-five

cents to a dollar apiece. The current price of chickens varies

according to size and season from twenty to fifty cents. You may offer

the latter price and be refused. The next day the very same man may

appear at your home, offering for twenty or thirty cents the fowls for

which the day before he refused fifty.

Except in the cold storage and the Chino grocery shops of Manila,

nothing can be bought without chaffering. The Filipinos love this; they

realize that we are impatient and seldom can hold out long at it, and

in many cases they overcharge us from sheer race hatred. Also they have

the idea, as they would express it, that our money is two times as much

as theirs, and that therefore we should pay two prices. Often they put

a price from sheer caprice or effrontery and hang to it from obstinacy.

In the same market I have found mangoes of the same quality ranging all

the way from thirty cents to a dollar and fifty cents a dozen.

In the provinces market produce is very limited. In fresh foods

there is nothing but sweet potatoes, several [246]varieties of squash, a kind of string bean, lima

beans, lettuce, radishes, cucumbers (in season), spinach, and field

corn. Potatoes and onions can be procured only from Manila, bought by

the crate. If there be no local commissary, tinned foods must be sent

in bulk from Manila. The housekeeper’s task is no easy one, and

the lack of fresh beef, ice, fresh butter, and milk wears hard on a

dainty appetite. The Philippines are no place for women or men who

cannot thrive and be happy on plain food, plenty of work, and

isolation. Nor is there any sadder lot than that of the American

married woman in the provinces who is unemployed. Her housekeeping

takes very little time, for the cheapness of native servants obviates

the necessity of all labor but that of supervision. There is nowhere to

go, nothing to do, nothing to read, nothing to talk about. She has

nothing to do but to lie in a steamer chair and to think of home. Most

women break down under it very quickly; they lose appetite and flesh

and grow fretful or melancholy. But to a woman who loves her home and

is employed, provincial life here is a boon. Remember that for an

expenditure of forty or fifty dollars a month the single woman can

maintain an establishment of her own—a genuine home—where

after a day’s toil she can find order and peace and idleness

awaiting her. Filipino servants are not ideal, but any woman with a

capacity for organization can soon train them into keeping her house in

the outward semblance at least of order and cleanliness. She had better

investigate it pretty closely on Saturdays and Sundays; if she does so,

she can leave it to run itself [247]very well during the five

days of her labor. And what a joy it is—I speak in the bitter

remembrance of a long line of hotels and boarding-houses—to go

back to one’s home after a day’s labor instead of to a hall

bedroom; to sit at one’s own well-ordered if simple table, and

escape the chatter of twenty or thirty people who have no reason for

association except their economic necessities!

In the six years I have lived in these Islands, I have never heard

of indignity or disrespect shown to American women.1 They are

perfectly safe, and if they choose to exercise any common sense, need

not be nervous. Housebreaking outside of Manila is unknown. I myself

lived for four years in a provincial town, the greater part of the time

quite removed from the neighborhood of other Americans, with only two

little girls in the house with me. I remember one evening having a

couple of civil engineers, who had been fellow passengers on the

transport and were temporarily in town, to dinner. When they were ready

to leave, at half-past ten, the little girls had both gone to sleep, so

I went downstairs to let them out and bar the door after them. One

burst out laughing and remarked that my bolting the door was a

formality, and that I must have confidence in the honesty of the

natives. The door was of bamboo, tied on with strips of rattan in place

of hinges, which any one could have cut with a knife. I admitted

[248]that the man was right, but the closed door was

the symbol that my house was my castle, and I had no fear of Filipino

thieves. The only time I was ever really afraid was when there were two

or three disreputable Americans in town.

The two girls from Radcliffe were in a town in Negros where there

was no other American, man or woman, and held their position for over a

year; nor were they once affrighted in all that time.

After five years of this peace and security in the

“wilds,” I went back to the United States and met the

pitying ejaculations of the community on my exile. Well, there was a

difference. I noted it first on the dining-car of the Canadian-Pacific

Railroad, where one’s plate was surrounded by a host of little

dishes, where the clatter of service was deafening (so different from

the noiselessness of the Oriental), and the gentleman who filled my

water glass held it about three feet from the water bottle, and

manipulated both in sympathetic curves which expressed his entire

mastery of the art. I found it again on the Northwestern, where the

colored porter, observing some Chinese coins in my purse when I tipped

him, said, “Le’s see,” with a confidence born of

democracy, and sat down on the arm of the Pullman seat to get a better

view of them.

But it was in Chicago—the busy, noisy, dusty, hustling

Chicago—that all the joys of civilization fell on me at once. It

seemed to be in a state of siege with house thieves, assassins, and

“hold-ups.” There had been several murders of women, so

revolting that the newspapers would not print the details. I found my

brother’s [249]flat equipped with special bolts on all

outside doors, so that they could be opened for an inch or two without

giving anybody an opportunity to push in. Once when a police officer

called at the door to ask for subscriptions for the sufferers of the

San Francisco disaster, I locked him out on the back porch while I did

some telephoning to see if it was all right. Women were afraid to be on

the streets in the early dusk. Extra policemen had been sworn in,

preachers had delivered sermons on the frightful condition of the

city.

At night I locked my bedroom door, and dreamed of masked burglars

standing over me threatening with drawn revolver. For the thirty days I

remained there, I knew more of nervousness and terror than the whole

time I spent in the Philippines, and I came back to resume the old life

where there is security in all things, barring a very remote

insurrection and the possibility of hearing the roar of Japanese guns

some fine morning. And through and through a grateful system I felt the

lifting of the tremendous pressure, the agonizing strain, competition,

and tumult of American life. Thank Heaven! there is still a

mañana country—a fair, sunny land, where rapid

transportation and sky-scrapers do not exist. [250]