Title: Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves, Volume V, Indiana Narratives

Author: United States. Work Projects Administration

Release date: October 2, 2004 [eBook #13579]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jeannie Howse, Andrea Ball, Terry Gilliland and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team. Produced from images provided

by the Library of Congress, Manuscript Division

[TR: ***] = Transcriber Note

[HW: ***] = Handwritten Note

Illustrated with Photographs

WASHINGTON 1941

[TR: Federal Writer Anna Pritchett annotated her interviews by marking each paragraph to indicate whether the information was obtained from the respondent (A) or was a comment by the interviewer (B). Since the information was presented in sequence, it is presented here without these markings, with the interviewer's remarks set apart by the topic heading 'Interviewer's Comment'.]

[TR: Information listed separately as References, such as informant names and addresses, has been incorporated into the interview headers. In some cases, information has been rearranged for readability. Names in brackets were drawn from text of interviews.]

This is written from an interview with each of the following: George W. Arnold, Professor W.S. Best of the Lincoln High School and Samuel Bell, all of Evansville, Indiana.

George W. Arnold was born April 7, 1861, in Bedford County, Tennessee. He was the property of Oliver P. Arnold, who owned a large farm or plantation in Bedford county. His mother was a native of Rome, Georgia, where she remained until twelve years of age, when she was sold at auction.

Oliver Arnold bought her, and he also purchased her three brothers and one uncle. The four negroes were taken along with other slaves from Georgia to Tennessee where they were put to work on the Arnold plantation.

On this plantation George W. Arnold was born and the child was allowed to live in a cabin with his relatives and declares that he never heard one of them speak an unkind word about Master Oliver Arnold or any member of his family. "Happiness and contentment and a reasonable amount of food and clothes seemed to be all we needed," said the now white-haired man.

Only a limited memory of Civil War days is retained by the old man but the few events recalled are vividly described by him. "Mother, my young brother, my sister and I were walking along one day. I don't remember where we had started but we passed under the fort at Wartrace. A battle was in progress and a large cannon was fired above us and we watched the huge ball sail through the air and saw the smoke of the cannon pass over our heads. We poor children were almost scared to death but our mother held us close to her and tried to comfort us. The next morning, after, we were safely at home ... we were proud we had seen that much of the great battle and our mother told us the war was to give us freedom."

"Did your family rejoice when they were set free?" was the natural question to ask Uncle George.

"I cannot say that they were happy, as it broke up a lot of real friendships and scattered many families. Mother had a great many pretty quilts and a lot of bedding. After the negroes were set free, Mars. Arnold told us we could all go and make ourselves homes, so we started out, each of the grown persons loaded with great bundles of bedding, clothing and personal belongings. We walked all the way to Wartrace to try to find a home and some way to make a living."

George W. Arnold remembers seeing many soldiers going to the pike road on their way to Murfreesboro. "Long lines of tired men passed through Guy's Gap on their way to Murfreesboro," said he. "Older people said that they were sent out to pick up the dead from the battle fields after the bloody battle of Stone's river that had lately been fought at Murfreesboro. They took their comrades to bury them at the Union Cemetery near the town of Murfreesboro."

"Wartrace was a very nice place to make our home. It was located on the Nashville and Chattanooga and St. Louis railroad, just fifty-one miles from Nashville not many miles from our old home. Mother found work and we got along very well but as soon as we children were old enough to work, she went back to her old home in Georgia where a few years later she died. I believe she lived to be seventy-five or seventy six years of age, but I never saw her after she went back to Georgia."

"My first work was done on a farm (there are many fine farms in Tennessee) and although farm labor was not very profitable we were always fed wherever we worked and got some wages. Then I got a job on the railroad. Our car was side tracked at a place called Silver Springs," said Uncle George, "and right at that place came trouble that took the happiness out of my life forever." Here the story teller paused to collect his thoughts and conquer the nervous twitching of his lips. "It was like this: Three of us boys worked together. We were like three brothers, always sharing our fortunes with each other. We should never have done it, but we had made a habit of sending to Nashville after each payday and having a keg of Holland rum sent in by freight. This liquor was handed out among our friends and sometimes we drank too much and were unfit for work for a day or two. Our boss was a big strong Irishman, red haired and friendly. He always got drunk with us and all would become sober enough to soon return to our tasks."

"The time I'm telling you about, we had all been invited to a candy pulling in town and could hardly wait till time to go, as all the young people of the valley would be there to pull candy, talk, play games and eat the goodies served to us. The accursed keg of Holland rum had been brought in that morning and my chum John Sims had been drinking too much. About that time our Boss came up and said, 'John, it is time for you to get the supper ready!' John was our cook and our meals were served on the caboose where we lived wherever we were side tracked."

"All the time Johny was preparing the food he was drinking the rum. When we went in he had many drinks inside of him and a quart bottle filled to take to the candy pull. 'Hurry up boys and let's finish up and go' he said impatiently. 'Don't take him' said the other boy, 'Dont you see he is drunk?' So I put my arms about his shoulders and tried to tell him he had better sleep a while before we started. The poor boy was a breed. His mother was almost white and his father was a thoroughbred Indian and the son had a most aggravating temper. He made me no answer but running his hand into his pocket, he drew out his knife and with one thrust, cut a deep gash in my neck. A terrible fight followed. I remember being knocked over and my head stricking something. I reached out my hand and discovered it was the ax. With this awful weapon I struck my friend, my more than brother. The thud of the ax brought me to my senses as our blood mingled. We were both almost mortally wounded. The boss came in and tried to do something for our relief but John said, 'Oh, George? what an awful thing we have done? We have never said a cross word to each other and now, look at us both.'"

"I watched poor John walk away, darkness was falling but early in the morning my boss and I followed a trail of blood down by the side of the tracks. From there he had turned into the woods. We could follow him no further. We went to all the nearby towns and villages but we found no person who had ever seen him. We supposed he had died in the woods and watched for the buzzards, thinking thay would lead us to his body but he was never seen again."

"For two years I never sat down to look inside a book nor to eat my food that John Sims was not beside me. He haunted my pillow and went beside me night and day. His blood was on my hands, his presence haunted me beyond endurance. What could I do? How could I escape this awful presence? An old friend told me to put water between myself and the place where the awful scene occurred. So, I quit working on the railroad and started working on the river. People believed at that time that the ghost of a person you had wronged would not cross water to haunt you."

Life on the river was diverting. Things were constantly happening and George Arnold put aside some of his unhappiness by engaging in river activities.

"My first job on the river was as a roust-about on the Bolliver H Cook a stern wheel packet which carried freight and passengers from Nashville, Tennessee to Evansville, Indiana. I worked a round trip on her and then went from Nashville to Cairo, Illinois on the B.S. Rhea. I soon decided to go to Cairo and take a place on the Eldarado, a St. Louis and Cincinnati packet which crused from Cairo to Cincinnati. On that boat I worked as a roust-about for nearly three years."

"What did the roust-about have to do?" asked a neighbor lad who had come into the room. "The roust-about is no better than the mate that rules him. If the mate is kindly disposed the roust-about has an easy enough life. The negroes had only a few years of freedom and resented cruelty. If the mate became too mean, a regular fight would follow and perhaps several roust-abouts would be hurt before it was finished."

Uncle George said that food was always plentiful on the boats. Passengers and freight were crowded together on the decks. At night there would be singing and dancing and fiddle music. "We roust-abouts would get together and shoot craps, dance or play cards until the call came to shuffle freight, then we would all get busy and the mate's voice giving orders could be heard for a long distance."

"In spite of these few pleasures, the life of a roust-about is the life of a dog. I do not recall any unkindnesses of slavery days. I was too young to realize what it was all about, but it could never have equalled the cruelty shown the laborer on the river boats by cruel mates and overseers."

Another superstition advanced itself in the story of a boat, told by Uncle George Arnold. The story follows: "When I was a roust-about on the Gold Dust we were sailing out from New Orleans and as soon as we got well out on the broad stream the rats commenced jumping over board. 'See these rats' said an old river man, 'This boat will never make a return trip!'"

"At every port some of our crew left the boat but the mate and the captain said they were all fools and begged us to stay. So a few of us stayed to do the necessary work but the rats kept leaving as fast as they could."

"When the boat was nearing Hickman, Kentucky, we smelled fire, and by the time we were in the harbor passengers were being held to keep them from jumping overboard. Then the Captain told us boys to jump into the water and save ourselves. Two of us launched a bale of cotton overboard and jumped onto it. As we paddled away we had to often go under to put out the fires as our clothing would blaze up under the flying brands that fell upon our bodies."

"The burning boat was docked at Hickman. The passengers were put ashore but none of the freight was saved, and from a nearby willow thicket my matey and I watched the Gold Dust burn to the water's edge."

"Always heed the warnings of nature," said Uncle George, "If you see rats leaving a ship or a house prepare for a fire."

George W. Arnold said that Evansville was quite a nice place and a steamboat port even in the early days of his boating experiences and he decided to make his home here. He located in the town in 1880. "The Court House was located at Third and Main streets. Street cars were mule drawn and people thought it great fun to ride them." He recalls the first shovel full of dirt being lifted when the new Courthouse was being erected, and when it was finished two white men finishing the slate roof, fell to their death in the Court House yard.

George W. Arnold procured a job as porter in a wholesale feed store on May 10, 1880. John Hubbard and Company did business at the place, at this place he worked thirty seven years. F.W. Griese, former mayor of Evansville has often befriended the negro man and is ready to speak a kindly word in his praise. But the face of John Sims still presents itself when George Arnold is alone. "Never do anything to hurt any other person," says he, "The hurt always comes back to you."

George Arnold was married to an Evansville Woman, but two years ago he became a widower when death claimed his mate. He is now lonely, but were it not for a keg of Holland gin his old age would be spent in peace and happiness. "Beware of strong drink," said Uncle George, "It causes trouble."

[Thomas Ash]

I have no way of knowing exactly how old I am, as the old Bible containing a record of my birth was destroyed by fire, many years ago, but I believe I am about eighty-one years old. If so, I must have been born sometime during the year, 1856, four years before the outbreak of the War Between The States. My mother was a slave on the plantation, or farm of Charles Ash, in Anderson county, Kentucky, and it was there that I grew up.

I remember playing with Ol' Massa's (as he was called) boys, Charley, Jim and Bill. I also have an unpleasant memory of having seen other slaves on the place, tied up to the whipping post and flogged for disobeying some order although I have no recollection of ever having been whipped myself as I was only a boy. I can also remember how the grown-up negroes on the place left to join the Union Army as soon as they learned of Lincoln's proclamation making them free men.

Ed. Note—Mr. Ash was sick when interviewed and was not able to do much talking. He had no picture of himself but agreed to pose for one later on. [TR: no photograph found.]

[Mrs. Mary Crane]

I was born on the farm of Wattie Williams, in 1855 and am eighty-two years old. I came to Mitchell, Indiana, about fifty years ago with my husband, who is now dead and four children and have lived here ever since. I was only a girl, about five or six years old when the Civil War broke out but I can remember very well, happenings of that time.

My mother was owned by Wattie Williams, who had a large farm, located in Larue county, Kentucky. My father was a slave on the farm of a Mr. Duret, nearby.

In those days, slave owners, whenever one of their daughters would get married, would give her and her husband a slave as a wedding present, usually allowing the girl to pick the one she wished to accompany her to her new home. When Mr. Duret's eldest daughter married Zeke Samples, she choose my father to accompany them to their home.

Zeke Samples proved to be a man who loved his toddies far better than his bride and before long he was "broke". Everything he had or owned, including my father, was to be sold at auction to pay off his debts.

In those days, there were men who made a business of buying up negroes at auction sales and shipping them down to New Orleans to be sold to owners of cotton and sugar cane plantations, just as men today, buy and ship cattle. These men were called "Nigger-traders" and they would ship whole boat loads at a time, buying them up, two or three here, two or three there, and holding them in a jail until they had a boat load. This practice gave rise to the expression, "sold down the river."

My father was to be sold at auction, along with all of the rest of Zeke Samples' property. Bob Cowherd, a neighbor of Matt Duret's owned my grandfather, and the old man, my grandfather, begged Col. Bob to buy my father from Zeke Samples to keep him from being "sold down the river." Col. Bob offered what he thought was a fair price for my father and a "nigger-trader" raised his bid "25 [TR: $25?]. Col. said he couldn't afford to pay that much and father was about to be sold to the "nigger-trader" when his father told Col. Bob that he had $25 saved up and that if he would buy my father from Samples and keep the "nigger-trader" from getting him he would give him the money. Col. Bob Cowherd took my grandfather's $25 and offered to meet the traders offer and so my father was sold to him.

The negroes in and around where I was raised were not treated badly, as a rule, by their masters. There was one slave owner, a Mr. Heady, who lived nearby, who treated his slave worse than any of the other owners but I never heard of anything so awfully bad, happening to his "niggers". He had one boy who used to come over to our place and I can remember hearing Massa Williams call to my grandmother, to cook "Christine, give Heady's Doc something to eat. He looks hungry." Massa Williams always said "Heady's Doc" when speaking of him or any other slave, saying to call him, for instance, Doc Heady would sound as if he were Mr. Heady's own son and he said that wouldn't sound right.

When President Lincoln issued his proclamation, freeing the negroes, I remember that my father and most all of the other younger slave men left the farms to join the Union army. We had hard times then for awhile and had lots of work to do. I don't remember just when I first regarded myself as "free" as many of the negroes didn't understand just what it was all about.

Ed. Note: Mrs. Crane will also pose for a picture.

Rosa Barber was born in slavery on the Fox Ellison plantation at North Carden[TR:?], in North Carolina, in the year 1861. She was four [HW: ?] years old when freed, but had not reached the age to be of value as a slave. Her memory is confined to that short childhood there and her experiences of those days and immediately after the Civil War must be taken from stories related to her by her parents in after years, and these are dimly retained.

Her maiden name was Rosa Fox Ellison, taken as was the custom, from the slave-holder who held her as a chattel. Her parents took her away from the plantation when they were freed and lived in different localities, supported by the father who was now paid American wages. Her parents died while she was quite young and she married Fox Ellison, an ex-slave of the Fox Ellison plantation. His name was taken from the same master as was hers. She and her husband lived together forty-three years, until his death. Nine children were born to them of which only one survives. After this ex-slave husband died Rosa Ellison married a second time, but this second husband died some years ago and she now remains a widow at the age of seventy-six years. She recalls that the master of the Fox Ellison plantation was spoken of as practicing no extreme discipline on his slaves. Slaves, as a prevailing business policy of the holder, were not allowed to look into a book, or any printed matter, and Rosa had no pictures or printed charts given her. She had to play with her rag dolls, or a ball of yarn, if there happened to be enough of old string to make one. Any toy or plaything was allowed that did not point toward book-knowledge. Nursery rhymes and folk-lore stories were censured severely and had to be confined to events that conveyed no uplift, culture or propaganda, or that conveyed no knowledge, directly or indirectly. Especially did they bar the mental polishing of the three R's. They could not prevent the vocalizing of music in the fields and the slaves found consolation there in pouring out their souls in unison with the songs of the birds.

Mrs. Blakeley was born, in Oxford, Missouri, in 1858.

Her mother died when Mittie was a baby, and she was taken into the "big house" and brought up with the white children. She was always treated very kindly.

Her duties were the light chores, which had to be well done, or she was chided, the same as the white children would have been.

Every evening the children had to collect the eggs. The child, who brought in the most eggs, would get a ginger cake. Mittie most always got the cake.

Her older brothers and sisters were treated very rough, whipped often and hard. She said she hated to think, much less talk about their awful treatment.

When she was old enough, she would have to spin the wool for her mistress, who wove the cloth to make the family clothes.

She also learned to knit, and after supper would knit until bedtime.

She remembers once an old woman slave had displeased her master about something. He had a pit dug, and boards placed over the hole. The woman was made to lie on the boards, face down, and she was beaten until the blood gushed from her body; she was left there and bled to death.

She also remembers how the slaves would go to some cabin at night for their dances; if one went without a pass, which often they did, they would be beaten severely.

The slaves could hear the overseers, riding toward the cabin. Those, who had come without a pass, would take the boards up from the floor, get under the cabin floor, and stay there until the overseers had gone.

Interviewer's Comment

Mrs. Blakeley is very serious and said she felt so sorry for those, who were treated so such worse than any human would treat a beast.

She lives in a very comfortable clean house, and said she was doing "very well."

This is a story of slavery, told by Carl Boone about his father, his mother and himself. Carl is the last of eighteen children born to Mrs. Stephen Boone, in Marion County, Kentucky, Sept. 15, 1850. He now resides with his children at 801 West 13th Street, Anderson, Madison County, Indiana. At the ripe old age of eighty-seven, he still has a keen memory and is able to do a hard day's work.

Carl Boone was born a free man, fifteen years before the close of the Civil War, his father having gained his freedom from slavery in 1829. He is a religious man, having missed church service only twice in twenty years. He was treated well during the time of slavery in the southland, but remembers well, the wrongs done to slaves on neighboring plantations, and in this story he relates some of the horrors which happened at that time.

Like his father, he is also the father of eighteen children, sixteen of whom are still living. He is grandfather of thirty-seven and great grandfather of one child. His father was born in the slave state of Maryland, in 1800, and died in 1897. His mother was born in Marion County, Kentucky, in 1802, and died in 1917, at the age of one hundred and fifteen years.

This story, word by word, is related by Carl Boone as follows: "My name is Carl Boone, son of Stephen and Rachel Boone, born in Marion County, Kentucky, in 1850. I am father of eighteen children sixteen are still living and I am grandfather of thirty-seven and great grandfather of one child. I came with my wife, now deceased, to Indiana, in 1891, and now reside at 801 West 13th street in Anderson, Indiana. I was born a free man, fifteen years before the close of the Civil War. All the colored folk on plantations and farms around our plantation were slaves and most of them were terribly mistreated by their masters.

After coming to Indiana, I farmed for a few years, then moved to Anderson. I became connected with the Colored Catholic Church and have tried to live a Christian life. I have only missed church service twice in twenty years. I lost my dear wife thirteen years ago and I now live with my son.

My father, Stephen Boone, was born in Maryland, in 1800. He was bought by a nigger buyer while a boy and was sold to Miley Boone in Marion County, Kentucky. Father was what they used to call "a picked slave," was a good worker and was never mistreated by his master. He married my mother in 1825, and they had eighteen children. Master Miley Boone gave father and mother their freedom in 1829, and gave them forty acres of land to tend as their own. He paid father for all the work he did for him after that, and was always very kind to them.

My mother was born in slavery, in Marion County, Kentucky, in 1802. She was treated very mean until she married my father in 1825. With him she gained her freedom in 1829. I was the last born of her eighteen children. She was a good woman and joined church after coming to Indiana and died in 1917, living to be one hundred and fifteen years old.

I have heard my mother tell of a girl slave who worked in the kitchen of my mother's master. The girl was told to cook twelve eggs for breakfast. When the eggs were served, it was discovered there were eleven eggs on the table and after being questioned, she admitted that she had eaten one. For this, she was beaten mercilessly, which was a common sight on that plantation.

The most terrible treatment of any slave, is told by my father in a story of a slave on a neighboring plantation, owned by Daniel Thompson. "After committing a small wrong, Master Thompson became angry, tied his slave to a whipping post and beat him terribly. Mrs. Thompson begged him to quit whipping, saying, 'you might kill him,' and the master replied that he aimed to kill him. He then tied the slave behind a horse and dragged him over a fifty acre field until the slave was dead. As a punishment for this terrible deed, master Thompson was compelled to witness the execution of his own son, one year later. The story is as follows:

A neighbor to Mr. Thompson, a slave owner by name of Kay Van Cleve, had been having some trouble with one of his young male slaves, and had promised the slave a whipping. The slave was a powerful man and Mr. Van Cleve was afraid to undertake the job of whipping him alone. He called for help from his neighbors, Daniel Thompson and his son Donald. The slave, while the Thompsons were coming, concealed himself in a horse-stall in the barn and hid a large knife in the manger.

After the arrival of the Thompsons, they and Mr. Van Cleve entered the stall in the barn. Together, the three white men made a grab for the slave, when the slave suddenly made a lunge at the elder Mr. Thompson with the knife, but missed him and stabbed Donald Thompson.

The slave was overpowered and tied, but too late, young Donald was dead.

The slave was tried for murder and sentenced to be hanged. At the time of the hanging, the first and second ropes used broke when the trap was sprung. For a while the executioner considered freeing the slave because of his second failure to hang him, but the law said, "He shall hang by the neck until dead," and the third attempt was successful."

Mrs. Bowman was born in Woodford County, Kentucky in 1859.

Her master, Joel W. Twyman was kind and generous to all of his slaves, and he had many of them.

The Twyman slaves were always spoken of, as the Twyman "Kinfolks."

All slaves worked hard on the large farm, as every kind of vegetation was raised. They were given some of everything that grew on the farm, therefore there was no stealing to get food.

The master had his own slaves, and the mistress had her own slaves, and all were treated very kindly.

Mrs. Bowman was taken into the Twyman "big house," at the age of six, to help the mistress in any way she could. She stayed in the house until slavery was abolished.

After freedom, the old master was taken very sick and some of the former slaves were sent for, as he wanted some of his "Kinfolks" around him when he died.

Interviewer's Comment

Mrs. Bowman was given the Twyman family bible where her birth is recorded with the rest of the Twyman family. She shows it with pride.

Mrs. Bowman said she never knew want in slave times, as she has known it in these times of depression.

Mrs. Angie Boyce here makes mention of facts as outlined to her by her mother, Mrs. Margaret King, deceased.

Mrs. Angie Boyce was born in slavery, Mar. 14, 1861, on the Breeding Plantation, Adair County, Kentucky. Her parents were Henry and Margaret King who belonged to James Breeding, a Methodist minister who was kind to all his slaves and no remembrance of his having ever struck one of them.

It is said that the slaves were in constant dread of the Rebel soldiers and when they would hear of their coming they would hide the baby "Angie" and cover her over with leaves.

The mother of Angie was married twice; the name of her first husband was Stines and that of her second husband was Henry King. It was Henry King who bought his and his wife's freedom. He sent his wife and baby Angie to Indiana, but upon their arrival they were arrested and returned to Kentucky. They were placed in the Louisville jail and lodged in the same cell with large Brutal and drunken Irish woman. The jail was so infested with bugs and fleas that the baby Angie cryed all night. The white woman crazed with drink became enraged at the cries of the child and threatened to "bash its brains out against the wall if it did not stop crying". The mother, Mrs. King was forced to stay awake all night to keep the white woman from carrying out her threat.

The next morning the Negro mother was tried in court and when she produced her free papers she was asked why she did not show these papers to the arresting officers. She replied that she was afraid that they would steal them from her. She was exonerated from all charges and sent back to Indiana with her baby.

Mrs. Angie Boyce now resides at 498 W. Madison St., Franklin, Ind.

Mrs. Boysaw has been a citizen of this community about sixty-five years. She resides on a small farm, two miles east of Brazil on what is known as the Pinkley Street Road. This has been her home for the past forty years. Her youngest son and the son of one of her daughters lives with her. She is still very active, doing her housework and other chores about the farm. She is very intelligent and according to statements made by other citizens has always been a respected citizen in the community, as also has her entire family. She is the mother of twelve children. Mrs. Boysaw has always been an active church worker, spending much time in missionary work for the colored people. Her work was so outstanding that she has been often called upon to speak, not only in the colored churches, but also in white churches, where she was always well received. Many of the most prominent people of the community number Mrs. Boysaw as one of their friends and her home is visited almost daily by citizens in all walks of life. Her many acts of kindness towards her neighbors and friends have endeared her to the people of Brazil, and because of her long residence in the community, she is looked upon as one of the pioneers.

Mrs. Boysaw's husband has been dead for thirty-five years. Her children are located in various cities throughout the country. She has a daughter who is a talented singer, and has appeared on programs with her daughter in many churches. She is not certain about her age, but according to her memory of events, she is about eighty-seven.

Her story as told to the writer follows:

"When the Civil War ended, I was living near Richmond, Virginia. I am not sure just how old I was, but I was a big, flat-footed woman, and had worked as a slave on a plantation. My master was a good one, but many of them were not. In a way, we were happy and contented, working from sun up to sun down. But when Lincoln freed us, we rejoiced, yet we knew we had to seek employment now and make our own way. Wages were low. You worked from morning until night for a dollar, but we did not complain. About 1870 a Mr. Masten, who was a coal operator, came to Richmond seeking laborers for his mines in Clay County. He told us that men could make four to five dollars a day working in the mines, going to work at seven and quitting at 3:30 each day. That sounded like a Paradise to our men folks. Big money and you could get rich in little time. But he did not tell all, because he wanted the men folk to come with him to Indiana. Three or four hundred came with Mr. Masten. They were brought in box cars. Mr. Masten paid their transportation, but was to keep it out of their wages. My husband was in that bunch, and the women folk stayed behind until their men could earn enough for their transportation to Indiana."

"When they arrived about four miles east of Brazil, or what was known as Harmony, the train was stopped and a crowd of white miners ordered them not to come any nearer Brazil. Then the trouble began. Our men did not know of the labor trouble, as they were not told of that part. Here they were fifteen hundred miles from home, no money. It was terrible. Many walked back to Virginia. Some went on foot to Illinois. Mr. Masten took some of them South of Brazil about three miles, where he had a number of company houses, and they tried to work in his mine there. But many were shot at from the bushes and killed. Guards were placed about the mine by the owner, but still there was trouble all the time. The men did not make what Mr. Masten told them they could make, yet they had to stay for they had no place to go. After about six months, my husband who had been working in that mine, fell into the shaft and was injured. He was unable to work for over a year. I came with my two children to take care of him. We had only a little furniture, slept in what was called box beds. I walked to Brazil each morning and worked at whatever I could get to do. Often did three washings a day and then walked home each evening, a distance of two miles, and got a dollar a day.

"Many of the white folks I worked for were well to do and often I would ask the Mistress for small amounts of food which they would throw out if left over from a meal. They did not know what a hard time we were having, but they told me to take home any of such food that I cared to. I was sure glad to get it, for it helped to feed our family. Often the white folks would give me other articles which I appreciated. I managed in this way to get the children enough to eat and later when my husband was able to work, we got along very well, and were thankful. After the strike was settled, things were better. My husband was not afraid to go out after dark. But the coal operators did not treat the colored folks very good. We had to trade at the Company store and often pay a big price for it. But I worked hard and am still alive today, while all the others are gone, who lived around here about that time. There has sure been a change in the country. The country was almost a wilderness, and where my home is today, there were very few roads, just what we called a pig path through the woods. We used lots of corn meal, cooked beans and raised all the food we could during them days. But we had many white friends and sure was thankful for them. Here I am, and still thankful for the many friends I have."

Mrs. Callie Bracey's mother, Louise Terrell, was bought, when a child, by Andy Ramblet, a farmer, near Jackson, Miss. She had to work very hard in the fields from early morning until as late in the evening, as they could possibly see.

No matter how hard she had worked all day after coming in from the field, she would have to cook for the next day, packing the lunch buckets for the field hands. It made no difference how tired she was, when the horn was blown at 4 a.m., she had to go into the field for another day of hard work.

The women had to split rails all day long, just like the men. Once she got so cold, her feet seemed to be frozen; when they warmed a little, they had swollen so, she could not wear her shoes. She had to wrap her foot in burlap, so she would be able to go into the field the next day.

The Ramblets were known for their good butter. They always had more than they could use. The master wanted the slaves to have some, but the mistress wanted to sell it, she did not believe in giving good butter to slaves and always let it get strong before she would let them have any.

No slaves from neighboring farms were allowed on the Ramblet farm, they would get whipped off as Mr. Ramblet did not want anyone to put ideas in his slave's heads.

On special occasions, the older slaves were allowed to go to the church of their master, they had to sit in the back of the church, and take no part in the service.

Louise was given two dresses a year; her old dress from last year, she wore as an underskirt. She never had a hat, always wore a rag tied over her head.

Interviewer's Comment

Mrs. Bracey is a widow and has a grandchild living with her. She feels she is doing very well, her parents had so little, and she does own her own home.

This paper was prepared after several interviews had been obtained with the subject of this sketch.

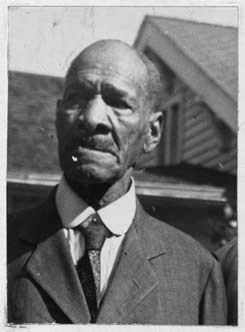

Dr. George Washingtin [TR: Washington] Buckner, tall, lean, whitehaired, genial and alert, answered the call of his door bell. Although anxious to oblige the writer and willing to grant an interview, the life of a city doctor is filled with anxious solicitation for others and he is always expecting a summons to the bedside of a patient or a professional interview has been slated.

Dr. Buckner is no exception and our interviews were often disturbed by the jingle of the door bell or a telephone call.

Dr. Buckner's conversation lead in ever widening circles, away from the topic under discussion when the events of his own life were discussed, but he is a fluent speaker and a student of psychology. Psychology as that philosophy relates to the mental and bodily tendencies of the African race has long since become one of the major subjects with which this unusual man struggles. "Why is the negro?" is one of his deepest concerns.

Dr. Buckner's first recollections center within a slave cabin in Kentucky. The cabin was the home of his step-father, his invalid mother and several children. The cabin was of the crudest construction, its only windows being merely holes in the cabin wall with crude bark shutters arranged to keep out snow and rain. The furnishings of this home consisted of a wood bedstead upon which a rough straw bed and patchwork quilts provided meager comforts for the invalid mother. A straw bed that could be pushed under the bed-stead through the day was pulled into the middle of the cabin at night and the wearied children were put to bed by the impatient step-father.

The parents were slaves and served a master not wealthy enough to provide adaquately for their comforts. The mother had become invalidate through the task of bearing children each year and being deprived of medical and surgical attention.

The master, Mr. Buckner, along with several of his relatives had purchased a large tract of land in Green County, Kentucky and by a custom or tradition as Dr. Buckner remembers; land owners that owned no slaves were considered "Po' White Trash" and were scarcely recognized as citizens within the state of Kentucky.

Another tradition prevailed, that slave children should be presented to the master's young sons and daughters and become their special property even in childhood. Adherring to that tradition the child, George Washington Buckner became the slave of young "Mars" Dickie Buckner, and although the two children were nearly the same age the little mulatto boy was obedient to the wishes of the little master. Indeed, the slave child cared for the Caucasian boy's clothing, polished his boots, put away his toys and was his playmate and companion as well as his slave.

Sickness and suffering and even death visits alike the just and the unjust, and the loving sympathetic slave boy witnessed the suffering and death of his little white friend. Then grief took possession of the little slave, he could not bear the sight of little Dick's toys nor books not [TR: nor?] clothing. He recalls one harrowing experience after the death of little Dick Buckner. George's grandmother was a housekeeper and kitchen maid for the white family. She was in the kitchen one late afternoon preparing the evening meal. The master had taken his family for a visit in the neighborhood and the mulatto child sat on the veranda and recalled pleasanter days. A sudden desire seized him to look into the bed room where little Mars Dickie had lain in the bed. The evening shadows had fallen, exagerated by the influence of trees, and vines, and when he placed his pale face near the window pane he thought it was the face of little Dickie looking out at him. His nerves gave away and he ran around the house screaming to his grandmother that he had seen Dickie's ghost. The old colored woman was sympathetic, dried his tears, then with tears coursing down her own cheeks she went about her duties. George firmly believed he had seen a ghost and never really convinced himself against the idea until he had reached the years of manhood. He remembers how the story reached the ears of the other slaves and they were terrorized at the suggestion of a ghost being in the master's home. "That is the way superstitions always started" said the Doctor, "Some nervous persons received a wrong impression and there were always others ready to embrace the error."

Dr. Buckner remembers that when a young daughter of his master married, his sister was given to her for a bridal gift and went away from her own mother to live in the young mistress' new home. "It always filled us with sorrow when we were separated either by circumstances of marriage or death. Although we were not properly housed, properly nourished nor properly clothed we loved each other and loved our cabin homes and were unhappy when compelled to part."

"There are many beautiful spots near the Green River and our home was situated near Greensburgh, the county seat of Dreen [TR: Green?] County." The area occupied by Mr. Buckner and his relatives is located near the river and the meanderings of the stream almost formed a peninsula covered with rich soil. Buckner's hill relieved the landscape and clear springs bubled through crevices affording much water for household use and near those springs white and negro children met to enjoy themselves.

"Forty years after I left Greensburg I went back to visit the springs and try to meet my old friends. The friends had passed away, only a few merchants and salespeople remembered my ancestors."

A story told by Dr. Buckner relates an evening at the beginning of the Civil War. "I had heard my parents talk of the war but it did not seem real to me until one night when mother came to the pallet where we slept and called to us to 'Get up and tell our uncles good-bye.' Then four startled little children arose. Mother was standing in the room with a candle or a sort of torch made from grease drippings and old pieces of cloth, (these rude candles were in common use and afforded but poor light) and there stood her four brothers, Jacob, John, Bill, and Isaac all with the light of adventure shining upon their mulatto countenances. They were starting away to fight for their liberties and we were greatly impressed."

Dr. Buckner stated that officials thought Jacob entirely too aged to enter the service as he had a few scattered white hairs but he remembers he was brawny and unafraid. Isaac was too young but the other two uncles were accepted. One never returned because he was killed in battle but one fought throughout the war and was never wounded. He remembers how the white men were indignant because the negroes were allowed to enlist and how Mars Stanton Buckner was forced to hide out in the woods for many months because he had met slave Frank Buckner and had tried to kill him. Frank returned to Greensburg, forgave his master and procurred a paper stating that he was at fault, after which Stanton returned to active service. "Yes, the road has been long. Memory brings back those days and the love of my mother is still real to me, God bless her!"

Relating to the value of an education Dr. Buckner hopes every Caucassian and Afro-American youth and maiden will strive to attain great heights. His first efforts to procure knowledge consisted of reciting A.B.S.s [TR: A.B.C.s?] from the McGuffy's [HW: ?] Blue backed speller with his unlettered sister for a teacher. In later years he attended a school conducted by the Freemen's Association. He bought a grammar from a white school boy and studied it at home. When sixteen years of age he was employed to teach negro children and grieves to recall how limited his ability was bound to have been. "When a father considers sending his son or daughter to school, today, he orders catalogues, consults his friends and considers the location and surroundings and the advice of those who have patronized the different schools. He finally decides upon the school that promises the boy or girl the most attractive and comfortable surroundings. When I taught the African children I boarded with an old man whose cabin was filled with his own family. I climbed a ladder leading from the cabin into a dark uncomfortable loft where a comfort and a straw bed were my only conveniences."

Leaving Greensburg the young mulatto made his way to Indianapolis where he became acquainted with the first educated Negro he had ever met. The Negro was Robert Bruce Bagby, then principal of the only school for Negroes in Indianapolis. "The same old building is standing there today that housed Bagby's institution then," he declares.

Dr. Buckner recalls that when he left Bagby's school he was so low financially he had to procure a position in a private residence as house boy. This position was followed by many jobs of serving tables at hotels and eating houses, of any and all kinds. While engaged in that work he met Colonel Albert Johnson and his lovely wife, both natives of Arkansas and he remembers their congratulations when they learned that he was striving for an education. They advised his entering an educational institution at Terre Haute. His desire had been to enter that institution of Normal Training but felt doubtful of succeeding in the advanced courses taught because his advantages had been so limited, but Mrs. Johnson told him that "God gives his talents to the different species and he would love and protect the negro boy."

After studying several years at the Terre Haute State Normal George W. Buckner felt assured that he was reasonably prepared to teach the negro youths and accepted the professorship of schools at Vincennes, Washington and other Indiana Villages. "I was interested in the young people and anxious for their advancement but the suffering endured by my invalid mother, who had passed into the great beyond, and the memory of little Master Dickie's lingering illness and untimely death would not desert my consciousness. I determined to take up the study of medical practice and surgery which I did."

Dr. Buckner graduated from the Indiana Electic Medical College in 1890. His services were needed at Indianapolis so he practiced medicine in that city for a year, then located at Evansville where he has enjoyed an ever increasing popularity on account of his sympathetic attitude among his people.

"When I came to Evansville," says Dr. Buckner, "there were seventy white physicians practicing in the area, they are now among the departed. Their task was streneous, roads were almost impossible to travel and those brave men soon sacrificed their lives for the good of suffering humanity." Dr. Buckner described several of the old doctors as "Striding [TR: illegible handwritten word above 'striding'] a horse and setting out through all kinds of weather."

Dr. Buckner is a veritable encyclopedia of negro lore. He stops at many points during an interview to relate stories he has gleaned here and there. He has forgotten where he first heard this one or that one but it helps to illustrate a point. One he heard near the end of the war follows, and although it has recently been retold it holds the interest of the listener. "Andrew Jackson owned an old negro slave, who stayed on at the old home when his beloved master went into politics, became an American soldier and statesman and finally the 7th president of the United States. The good slave still remained through the several years of the quiet uneventful last years of his master and witnessed his death, which occurred at his home near Nashville, Tennessee. After the master had been placed under the sod, Uncle Sammy was seen each day visiting Jackson's grave.

"Do you think President Jackson is in heaven?" an acquaintance asked Uncle Sammy.

"If-n he wanted to go dar, he dar now," said the old man. "If-n Mars Andy wanted to do any thing all Hell couldn't keep him from doin' it."

Dr. Buckner believes each Negro is confident that he will take himself with all his peculiarities to the land of promise. Each physical feature and habitual idiosyncrasy will abide in his redeemed personality. Old Joe will be there in person with the wrinkle crossing the bridge of his nose and little stephen will wear his wool pulled back from his eyes and each will recognize his fellow man. "What fools we all are," declared Dr. Buckner.

Asked his views concerning the different books embraced in the Holy Bible, Dr. Buckner, who is a student of the Bible said, "I believe almost every story in the Bible is an allegory, composed to illustrate some fundemental truth that could otherwise never have been clearly presented only through the medium of an allegory."

"The most treacherous impulse of the human nature and the one to be most dreaded is jealousy." With these words the aged Negro doctor launched into the expression of his political views. "I'm a Democrat." He then explained how he voted for the man but had confidence that his chosen party possesses ability in choosing proper candidates. He is an ardent follower of Franklin D. Roosevelt and speaks of Woodrow Wilson with bated breath.

Through the influence of John W. Boehne, Sr., and the friendly advice of other influential citizens of Evansville Dr. Buckner was appointed minister to Liberia, on Woodrow Wilson's cabinet, in the year 1913. Dr. Buckner appreciated the confidence of his friends in appointing him and cherishes the experineces gained while abroad. He noted the expressions of gratitude toward cabinet members by the citizens of that African coast. One Albino youth brought an offering of luscious mangoes and desired to see the minister from the United States of America. Some natives presented palm oils. "The natives have been made to understand that the United States has given aid to Liberia in a financial way and the customs-service of the republic is temporarily administered headed by an American." "A thoroughly civilized Negro state does not exist in Liberia nor do I believe in any part of West Africa. Superstition is the interpretation of their religion, their political views are a hodgepodge of unconnected ideas. Strength over rules knowledge and jealousy crowds out almost all hope of sympathetic achievement and adjustment." Dr. Buckner recounted incidents where jealousy was apparent in the behavior of men and women of higher civilizations than the African natives. While voyaging to Spain on board a Spanish vessel, he witnessed a very refined, polite Jewish woman being reduced to tears by the taunts of a Spanish officer, on account of her nationality. "Jealousy," he said, "protrudes itself into politics, religion and prevents educational achievement."

During a political campaign I was compelled to pay a robust Negro man to follow me about my professional visits and my social evenings with my friends and family, to prevent meeting physical violence to myself or family when political factions were virtually at war within the area of Evansville. The influence of political captains had brought about the dreadful condition and ignorant Negroes responded to their political graft, without realizing who had befriended them in need."

"The negro youths are especially subject to propoganda of the four-flusher for their home influence is, to say the least, negative. Their opportunities limited, their education neglected and they are easily aroused by the meddling influence of the vote-getter and the traitor. I would to God that their eyes might be opened to the light."

Dr. Buckner's influence is mostly exhibited in the sick room, where his presence is introduced in the effort to relieve pain.

The gradual rise from slavery to prominence, the many trials encountered along the road has ripened the always sympathetic nature of Dr. Buckner into a responsive suffer among a suffering people. He has hope that proper influences and sympathetic advice will mould the plastic character of the Afro-American youths of the United States into proper citizens and that their immortal souls inherit the promised reward of the redeemed through grace.

"Receivers of emancipation from slavery and enjoyers of emancipation from sin through the sacrifice of Abraham Lincoln and Jesus Christ; Why should not the negroes be exalted and happy?" are the words of Dr. Buckner.

Note: G.W. Buckner was born December 1st, 1852. The negroes in Kentucky expressed it, "In fox huntin' time" one brother was born in "Simmon time", one in "Sweet tater time," and another in "Plantin' time."

—Negro lore.

Ox-carts and flat boats, and pioneer surroundings; crowds of men and women crowding to the rails of river steamboats; gay ladies in holiday attire and gentleman in tall hats, low cut vests and silk mufflers; for the excursion boats carried the gentry of every area.

A little negro boy clung to the ragged skirts of a slave mother, both were engrossed in watching the great wheels that ploughed the Mississippi river into foaming billows. Many boats stopped at Gregery's Landing, Missouri to stow away wood, for many engines were fired with wood in the early days.

The Burns brothers operated a wood yard at the Landing and the work of cutting, hewing and piling wood for the commerce was performed by slaves of the Burns plantation.

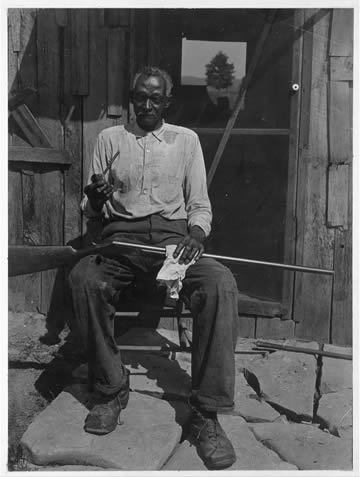

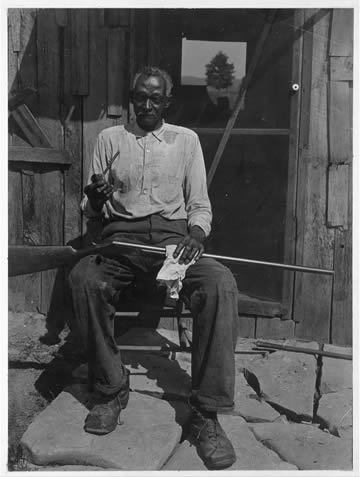

George Taylor Burns was five years of age and helped his mother all day as she toiled in the wood yards. "The colder the weather, the more hard work we had to do," declares Uncle George.

George Taylor Burns, the child of Missouri slave parents, recalls the scenes enacted at the Burns' wood yards so long ago. He is a resident of Evansville, Indiana and his snow white hair and beard bear testimony that his days have been already long upon the earth.

Uncle George remembers the time when his infant hands reached in vain for his mother, the kind and gentle Lucy Burns: Remembers a long cold winter of snow and ice when boats were tied up to their moorings. Old master died that winter and many slaves were sold by the heirs, among them was Lucy Burns. Little George clung to his mother but strong hands tore away his clasp. Then he watched her cross a distant hill, chained to a long line of departing slaves. George never saw his parents again and although the memory of his mother is vivid he scarcely remembers his father's face. He said, "Father was black but my mother was a bright mulatto."

Nothing impressed the little boy with such unforgettable imagery as the cold which descended upon Greogery's Landing one winter. Motherless, hungry, desolate and unloved, he often cried himself to sleep at night while each day he was compelled to carry wood. One morning he failed to come when the horn was sounded to call the slaves to breakfast. "Old Missus went to the Negro quarters to see what was wrong" and "She was horrified when she found I was frozen to the bed."

She carried the small bundle of suffering humanity to the kitchen of her home and placed him near the big oven. When the warmth thawed the frozen child the toes fell from his feet. "Old Missus told me I would never be strong enough to do hard work, and she had the neighborhood shoemaker fashion shoes too short for any body's feet but mine," said Uncle George.

Uncle George doesn't remember why he left Missouri but the sister of Greene Taylor brought him to Troy, Indiana. Here she learned that she could not own a slave within the State of Indiana so she indentured the child to a flat boat captain to wash dishes and wait on the crew of workers.

George was so small of stature that the captain had a low table and stool made that he might work in comfort. George's mistress received $15,00 [TR: $15.00?] per month for the service of the boy for several years.

From working on the flat boats George became accustomed to the river and soon received employment as a cabin boy on a steam boat and from that time through out the most active days of his life George Taylor Burns was a steam-boat man. In fact he declares, "I know steamboats from wood box to stern wheel."

"The life of a riverman is a good life and interesting things happen on the river," says Uncle George.

Uncle George has been imprisoned in the big jail at New Orleans. He has seen his fellow slaves beaten into insensibility while chained to the whipping post in Congo Square at New Orleans.

He was badly treated while a slave but he has witnessed even more cruel treatment administered to his fellow slaves.

Among other exciting occurrences remembered by the old negro man when he recalls early river adventures is one in which a flat boat sunk near New Orleans. After clinging for many hours to the drifting wreckage he was rescued, half dead from exhaustion.

In memory, George Taylor Burns stands in the slave mart at New Orleans and hears the Auctioneers' hammer, for he was sold like a beast of burden by Greene Taylor, brother of his mistress. Greene Taylor, however, had to refund the money and return the slave to his mistress when his crippled feet were discovered.

"Greene Taylor was like many other people I have known. He was always ready to make life unhappy for a negro."

Uncle George, although possessing an unusual amount of intelligence and ability to learn, has a very limited education. "The Negroes were not allowed an education," he relates. "It was dangerous for any person to be caught teaching a Negro and several Negroes were put to death because they could read."

Uncle George recalls a few superstitions entertained by the rivermen. "It was bad luck for a white cat to come aboard the boat." "Horse shoes were carried for good luck." "If rats left the boat the crew was uneasy, for fear of a wreck." Uncle George has very little faith in any superstition but remembers some of the crews had.

Among other boats on which this old river man was employed are "The Atlantic" on which he was cabin boy. The "Big Gray Eagle" on which he assisted in many ways. He worked where boats were being constructed while he lived at New Albany.

Many soldiers were returned to their homes by means of flat boats and steam boats when the Civil War had ended and many recruits were sent by water during the war. Just after peace was declared George met Elizabeth Slye, a young slave girl who had just been set free. "Liza would come to see her mother who was working on a boat." "People used to come down to the landings to see boats come in," said Uncle George. George and Liza were free, they married and made New Albany their home, until 1881 when they came to Evansville.

Uncle George said the Eclipse was a beautiful boat, he remembers the lettering in gold and the bright lights and polished rails of the longest steam boat ever built in the West. Measuring 365 feet in length and Uncle George declares, "For speed she just up and hustled."

"Louisville was one of the busiest towns in the Ohio Valley," says Uncle George, but he remembers New Orleans as the market place where almost all the surplus products were marketed.

Uncle George has many friends along the water-front towns. He admires the Felker family of Tell City, Indiana. He is proud of his own race and rejoices in their opportunities. He remembers his fear of the Ku Klux, his horror of the patrol and other clans united to make life dangerous for newly emancipated Negroes.

George Taylor Burns draws no old age pension. He owns a building located at Canal and Evans Streets that houses a number of Negro families. He is glad to say his credit is good in every market in the city. Although lamed by rheumatic pains and hobbling on feet toeless from his young childhood he has led a useful life. "Don't forget I knew Pilot Tom Ballard, and Aaron Ballard on the Big Eagle in 1858," warns Uncle George. "We Negroes carried passes so we could save our skins if we were caught off the boats but we had plenty of good food on the boats."

Uncle George said the roustabouts sang gay songs while loading boats with heavy freight and provisions but on account of his crippled feet he could not be a roustabout.

Interviewer's Comment

Belle Butler, the daughter of Chaney Mayer, tells of the hardships her mother endured during her days of slavery.

Interview

Chaney was owned by Jesse Coffer, "a mean old devil." He would whip his slaves for the slightest misdemeanor, and many times for nothing at all—just enjoyed seeing them suffer. Many a time Jesse would whip a slave, throw him down, and gouge his eyes out. Such a cruel act!

Chaney's sister was also a slave on the Coffer plantation. One day their master decided to whip them both. After whipping them very hard, he started to throw them down, to go after their eyes. Chaney grabbed one of his hands, her sister grabbed his other hand, each girl bit a finger entirely off of each hand of their master. This, of course, hurt him so very bad he had to stop their punishment and never attempted to whip them again. He told them he would surely put them in his pocket (sell them) if they ever dared to try *anthing like that again in life.

Not so long after their fight, Chaney was given to a daughter of their master, and her sister was given to another daughter and taken to Passaic County, N.C.

On the next farm to the Coffer farm, the overseers would tie the slaves to the joists by their thumbs, whip them unmercifully, then salt their backs to make them very sore.

When a slave slowed down on his corn hoeing, no matter if he were sick, or just very tired, he would get many lashes and a salted back.

One woman left the plantation without a pass. The overseer caught her and whipped her to death.

No slave was ever allowed to look at a book, for fear he might learn to read. One day the old mistress caught a slave boy with a book, she cursed him and asked him what he meant, and what he thought he could do with a book. She said he looked like a black dog with a breast pin on, and forbade him to ever look into a book again.

All slaves on the Coffer plantation were treated in a most inhuman manner, scarcely having enough to eat, unless they would steal it, running the risk of being caught and receiving a severe beating for the theft.

Interviewer's Comment

Mrs. Butler lives with her daughters, has worked very hard in "her days."

She has had to give up almost everything in the last few years, because her eyesight has failed. However, she is very cheerful and enjoys telling the "tales" her mother would tell her.

This information was gained through an interview with Joseph William Carter and several of his daughters. The data was cheerfully given to the writer. Joseph William Carter has lived a long and, he declares, a happy life, although he was born and reared in bondage. His pleasing personality has always made his lot an easy one and his yoke seemed easy to wear.

Joseph William Carter was born prior to the year 1836. His mother, Malvina Gardner was a slave in the home of Mr. Gardner until a man named D.B. Smith saw her and noticing the physical perfection of the child at once purchased her from her master.

Malvina was agrieved at being compelled to leave her old home, and her lovely young mistress. Puss Gardner was fond of the little mullato girl and had taught her to be a useful member of the Gardner family; however, she was sold to Mr. Smith and was compelled to accompany him to his home.

Both the Gardner and Smith families lived near Gallatin, Tennessee, in Sumner County. The Smith plantation was situated on the Cumberland River and commanded a beautiful view of river and valley acres but Malvina was very unhappy. She did not enjoy the Smith family and longed for her old friends back in the Gardner home.

One night the little girl gathered together her few personal belongings and started back to her old home.

Afraid to travel the highway the child followed a path she knew through the forest; but alas, she found the way long and beset with perils. A number of uncivil Indians were encamped on the side of the Cumberland mountains and a number of the young braves were out hunting that night. Their stealthy approach was heard by the little fugitive girl but too late for her to make an escape. An Indian called "Buck" captured her and by all the laws of the tribe was his own property. She lived for almost a year in the teepe with Buck and during that time learned much about Indian habits.

When Malvina was missed from her new home, Mr. Smith went to the Gardner plantation to report his loss, not finding her there a wide search was made for her but the Indians kept her thoroughly concealed. Miss Puss, however, kept up the search. She knew the Indians were encamped on the mountain and believed she would find the girl with them. The Indians finally broke camp and the members of the Gardner home watched them start on their journey and Miss Puss soon discovered Malvina among the other maidens in the procession.

The men of the Gardner plantation, white and black, overtook the Indians and demanded the girl be given up to them. The Indians reluctantly gave her to them. Miss Puss Gardner took her back and Mr. Gardner paid Mr. Smith the original purchase price and Malvina was once more installed in her old home.

Malvina Gardner was not yet twelve years of age when she was captured by the Indians and was scarcely thirteen years of age when she became the mother of Joseph William, son of the uncivil Indian, "Buck". The child was born in the Gardner home and mother and child remained there. The mother was a good slave and loved the members of the Gardner family and her son and she were loved by them in return.

Puss Gardner married a Mr. Mooney and Mr. Gardner allowed her to take Joseph William to her home. The Mooney estate was situated up on the Carthridge road and some of Joseph William's most vivid memories of slavery and the curse of bondage embrace his life's span with the Mooneys.

One story that the aged man relates is of an encounter with an eagle and follows: "George Irish, a white boy near my own age, was the son of the miller. His father operated a sawmill on Bledsoe Creek near where it empties into the Coumberland river. George and I often went fishing together and had a good dog called Hector. Hector was as good a coon dog as there was to be found in that part of the country. That day we boys climbed up on the mill shed to watch the swans in Bledsoe Creek and we soon noticed a great big fish hawk catching the goslings. It made us mad and we decided to kill the hawk. I went back to the house and got an old flint lock rifle Mars. Mooney had let me carry when we went hunting. When I got back where George was, the big bird was still busy catching goslings. The first shot I fired broke its wing and I decided I would catch it and take it home with me. The bird put up a terrible fight, cutting me with its bill and talons. Hector came running and tried to help me but the bird cut him until his howls brought help from the field. Mr. Jacob Greene was passing along and came to us. He tore me away from the bird but I could not walk and the blood was running from my body in dozens of places. Poor old Hector, was crippled and bleeding for the bird was a big eagle and would have killed both of us if help had not come." The old negro man still shows signs of his encounter with the eagle. He said it was captured and lived about four months in captivity but its wing never healed. The body of the eagle was stuffed with wheat bran, by Greene Harris, and placed in the court yard in Sumner County. "The Civil War changed things at the Mooney plantation," said the old man. "Before the War Mr. Mooney never had been cruel to me. I was Mistress Puss's property and she would never have allowed me to be abused, but some of the other slaves endured the most cruel treatment and were worked nearly to death."

Uncle Joe's memory of slavery embraces the whole story of bondage and the helpless position held by strong bodied men and women of a hardy race, overpowered by the narrow ideals of slave owners and cruel overseerers. "When I was a little bitsy child and still lived with Mr. Gardner," said the old man, "I saw many of the slaves beaten to death. Master Gardner didn't do any of the whippin' but every few months he sent to Mississippi for negro rulers to come to the plantation and whip all the negroes that had not obeyed the overseers. A big barrel lay near the barn and that was always the whippin place." Uncle Joe remembers two or three professional slave whippers and recalls the death of two of the Mississippi whippers. He relates the story as follows: "Mars Gardner had one of the finest black smiths that I ever saw. His arms were strong, his muscles stood out on his breast and shoulders and his legs were never tired. He stood there and shoed horses and repaired tools day after day and there was no work ever made him tired."

The old negro man so vividly described the noble blacksmith that he almost appeared in person, as the story advanced. "I don't know what he had done to rile up Mars Gardner, but all of us knew that the Blacksmith was going to be flogged. When the whippers from Mississippi got to the plantation. The blacksmith worked on day and night. All day he was shoein horses and all the spare time he had he was makin a knife. When the whippers got there all of us were brought out to watch the whippin but the blacksmith, Jim Gardner did not wait to feel the lash, he jumped right into the bunch of overseers and negro whippers and knifed two whippers and one overseer to death; then stuck the sharp knife into his arm and bled to death."

Suicide seemed the only hope for this man of strength. He could not humble himself to the brutal ordeal of being beaten by the slave whippers.

"When the war started, we kept hearing about the soldiers and finally they set up their camp in the forest near us. The corn was ready to bring into the barn and the soldiers told Mr. Mooney to let the slaves gather it and put it into the barns. Some of the soldiers helped gather and crib the corn. I wanted to help but Miss Puss was afraid they would press me into service and made me hide in the cellar. There was a big keg of apple cider in the cellar and every day Miss Puss handed down a big plate of fresh ginger snaps right out of the oven, so I was well fixed." The old man remembers that after the corn was in the crib the soldiers turned in their horses to eat what had fallen to the ground.

Before the soldiers became encamped at the Mooney plantation they had camped upon a hill and some skirmishing had occurred. Uncle Joe remembers the skirmish and seeing cannon balls come over the fields. The cannon balls were chained together and the slave children would run after the missils. Sometimes the chains would cut down trees as the balls rolled through the forest.

"Do you believe in witchcraft?" was asked while interviewing the aged negro. "No" was the answer. "I had a cousin that was a full blooded Indian and a Voodoo doctor. He got me to help him with his Voodoo work. A lot of people both white and black sent for the Indian when they were sick. I told him I would do the best I could, if it would help sick people to get well. A woman was sick with rhumatism and he was going to see her. He sent me into the woods to dig up poke roots to boil. He then took the brew to the house where the sick woman lived. Had her to put both feet in a tub filled with warm water, into which he had placed the poke root brew. He told the woman she had lizards in her body and he was going to bring them out of her. He covered the woman with a heavy blanket and made her sit for a long time, possibly an hour, with her feet in the tub of poke root brew and water. He had me slip a good many lizards into the tub and when the woman removed her feet, there were the lizards. She was soon well and believed the lizards had come out of her legs. I was disgusted and would not practice with my cousin again."

"So you didn't fight in the Civil War," was asked Uncle Joe.

"Of course I did, when I got old enough I entered the service and barbacued meat until the war closed." Barbacueing had been Uncle Joe's specialty during slavery days and he followed the same profession during his service with the federal army. He was freed by the emancuapation proclamation, and soon met and married Sadie Scott, former Slave of Mr. Scott, a Tennessee planter. Sadie only lived a short time after her marriage. He later married Amy Doolins. Her father was named Carmuel. He was a blacksmith and after he was free, the countrymen were after him to take his life. He was shot nine times and finally killed himself to prevent meeting death at the hands of the clansmen.

Joseph William Carter is a cripple. In 1933 he fell and broke his right thigh-bone and since that time he has walked with a crutch. He stays up quite a lot and is always glad to welcome visitors. He possesses a noble character and is admired by his friends and neighbors. Tall, straight, lean of body, his nose is aquiline; these physical characteristics he inherited from his Indian ancesters. His gentle nature, wit, and good humor are characteristics handed to him by his mother and fostered by the gentle rearing of his southern mistress.

When Uncle Joe Carter celebrated the 100dth aniversary of his birth a large cake was presented to him, decorated with 100 candles. The party was attended by children and grandchildren, friends and neighbors. "What is your political viewpoint?" was asked the old man.

"My politics is my love for my country". "I vote for the man, not the party."

Uncle Joe's religion is the religion of decency and virtue. "I don't want to be hard in my judgement," said he, "But I wish the whole world would be decent. When I was a young man, women wore more clothes in bed than they now wear on the street."

"Papa has always been a lover of horses but he does not care for Automobiles nor aeroplanes," said a daughter of Uncle Joe. Uncle Joe has seven daughters, he says they have always been obedient and attentive to their parents. Their mother passed away seven years ago. The sons and daughters of Uncle Joe remember their grand-mother and recall stories recounted by her of her captivity among the Indians.

"Papa had no gray hairs until after mama died. His hair turned gray from grief at her loss," said Mrs. Della Smith, one of his daughters. Uncle Joe's smile reveals a set of unusually sound teeth from which only one tooth is missing.

Like all fathers and grandfathers, Uncle Joe recounts the cute deeds and funny sayings of the little children he has been associated with: how his own children with feather bedecked crowns enacted the capture of their grandmother and often played "Voo-Doo Doctor."

Uncle Joe stresses the value of work, not the enforced labor of the slave but the cheerful toil of free people. He is glad that his sons and daughters are industrious citizens and is proud they maintain clean homes for their families. He is happy because his children have never known bondage, and he respects the laws of his country and appreciates the interest that the citizens of Evansville have always showed in the negro race.

After Uncle Joe became a young man he met many Indians from the tribe that had held his mother captive. Through them he learned much about his father which his mother had never told him.

Though he was a Gardner slave and would have been Joseph Gardner, he took the name of Carter from a step father and is known as Joseph Carter.

Assistant editor of "The Rising Sun Recorder" furnished the following story which had appeared in the paper, March 19, 1937.

Mrs. Cave was in slavery for twelve years before she was freed by the Emancipation Proclamation. When she gave her story to Aubrey Robinson she was living in a temporary garage home back of the Rising Sun courthouse having lost everything in the 1937 flood.

Mrs. Cave was born on a plantation in Taylor County Kentucky. She was the property of a man who did not live up to the popular idea of a Southern gentleman, whose slaves refused to leave them, even after their freedom was declared.

When she was a year old her mother was sold to someone in Louisana and she did not see her again until 1867, when they were re-united in Carrolton, Kentucky. Her father died when she was a baby.

Mrs. Cave told of seeing wagon loads of slaves sold down the river. She, herself was put on the block several times but never actually sold, although she would have preferred being sold rather than the continuation of the ordeal of the block.

Her master was a "mean man" who drank heavily, he had twenty slaves that he fed now and then, and gave her her freedom after the war only when she would remain silent about it no longer. He was a Southern sympathiser but joined the Union army where he became a captain and was in charge of a Union commissary. Finally he was suspected and charged with mustering supplies to the rebels. He was imprisoned for some time, then courtmartialed and sentenced to die. He escaped by bribing his negro guard.

Mrs. Cave said that her master's father had many young women slaves and sold his own half-breed children down the river to Louisiana plantations where the work was so severe that the slaves soon died.

While in slavery, Mrs. Cave worked as a maid in the house until she grew older when she was forced to do all kinds of outdoor labor. She remembered sawing logs in the snow all day. In the summer she pitched hay or any other man's work in the field. She was trained to carry three buckets of water at the same time, two in her hands and one on her head and said she could still do it.

On this plantation the chief article of food for the slaves was bran-bread, although the master's children were kind and often slipped them out meat or other food.

Mrs. Cave remembered seeing General Woolford and General Morgan of the Southern forces when they made friendly visits to the plantation. She saw General Grant twice during the war. She saw soldiers drilling near the plantation. Later she was caught and whipped by night riders, or "pat-a-rollers", as she tried to slip out to negro religious meetings.

Mrs. Cave was driven from her plantation two years after the war and came to Carrollton [TR: earlier, Carrolton] Kentucky, where she found her mother and soon married James Cave, a former slave on a plantation near hers in Taylor county. Mrs. Cave had thirteen children.

For many years Mrs. Cave has lived on a farm about two and one half mi. south of Rising Sun. Everything she had was washed away in the flood and she lived in the court house garage until her home could be rebuilt.

Interviewer's Comment