Title: Romance of California Life

Author: John Habberton

Release date: October 22, 2004 [eBook #13832]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Gene Smethers and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Romance of California Life, by John Habberton

Many of the sketches contained in "Some Folks" were written by me during the past five years, and some of them published by Mr. Leslie in his Illustrated Newspaper and his Chimney Corner, from which journals they have been collected by friends who believe that in these stories is displayed better workmanship than I have since done. For myself, I can claim for them only an unusual degree of that unliterary and unpopular quality called truthfulness. Although at present mildly tolerated in the East, I was "brought up" in the West, and have written largely from recollection of "some folks" I have known, veritable men and women, scenes and incidents, and otherwise through the memories of Western friends of good eyesight and hearing powers.

Should any one accuse me of having imitated Bret Harte's style, I shall accept the accusation as a compliment, for I know of no other American story writer so worthy to be taken as a teacher by men who acceptably tell the stories of new countries. For occasionally introducing characters and motives that would not be considered disgraceful in virtuous communities, I can only plead in excuse the fact that, even in the New West, some folks will occasionally be uniformly thoughtful, respectable and honest, just as individuals sometimes are in the East.

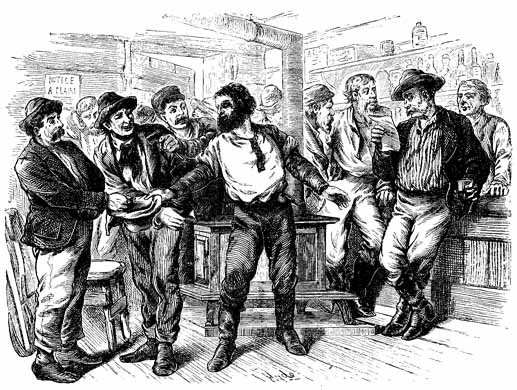

It certainly was hard. What was the freedom of a country in which the voice of the original founders was spent in vain? Had not they, the "Forty" miners of Bottle Flat, really started the place? Hadn't they located claims there? Hadn't they contributed three ounces each, ostensibly to set up in business a brother miner who unfortunately lost an arm, but really that a saloon might be opened, and the genuineness and stability of the camp be assured? Hadn't they promptly killed or scared away every Chinaman who had ever trailed his celestial pig-tail into the Flat? Hadn't they cut and beaten a trail to Placerville, so that miners could take a run to that city when the Flat became too quiet? Hadn't they framed the squarest betting code in the whole diggings? And when a 'Frisco man basely attempted to break up the camp by starting a gorgeous saloon a few miles up the creek, hadn't they gone up in a body and cleared him out, giving him only ten minutes in which to leave the creek for ever? All this they had done, actuated only by a stern sense of duty, and in the patient anticipation of the reward which traditionally crowns virtuous action. But now—oh, ingratitude of republics!—a schoolteacher was to be forced upon Bottle Flat in spite of all the protest which they, the oldest inhabitants, had made!

Such had been their plaint for days, but the sad excitement had not been productive of any fights, for the few married men in the camp prudently absented themselves at night from "The Nugget" saloon, where the matter was fiercely discussed every evening. There was, therefore, such an utter absence of diversity of opinion, that the most quarrelsome searched in vain for provocation.

On the afternoon of the day on which the opening events of this story occurred, the boys, by agreement, stopped work two hours earlier than usual, for the stage usually reached Bottle Flat about two hours before sundown, and the one of that day was to bring the hated teacher. The boys had wellnigh given up the idea of further resistance, yet curiosity has a small place even in manly bosoms, and they could at least look hatred at the detested pedagogue. So about four o'clock they gathered at The Nugget so suddenly, that several fathers; who were calmly drinking inside, had barely time to escape through the back windows.

The boys drank several times before composing themselves into their accustomed seats and leaning-places; but it was afterward asserted and Southpaw—the one-armed bar-keeper—cited as evidence, that none of them took sugar in their liquor. They subjected their sorrow to homeopathic treatment by drinking only the most raw and rasping fluids that the bar afforded.

The preliminary drinking over, they moodily whittled, chewed, and expectorated; a stranger would have imagined them a batch of miserable criminals awaiting transportation.

The silence was finally broken by a decided-looking red-haired man, who had been neatly beveling the door-post with his knife, and who spoke as if his words only by great difficulty escaped being bitten in two.

"We ken burn down the schoolhouse right before his face and eyes, and then mebbe the State Board'll git our idees about eddycation."

"Twon't be no use, Mose," said Judge Barber, whose legal title was honorary, and conferred because he had spent some time in a penitentiary in the East. "Them State Board fellers is wrong, but they've got grit, ur they'd never hev got the schoolhouse done after we rode the contractor out uv the Flat on one of his own boards. Besides, some uv 'em might think we wuz rubbin' uv it in, an' next thing you know'd they'd be buildin' us a jail."

"Can't we buy off these young uns' folks?" queried an angular fellow from Southern Illinois. "They're a mizzable pack of shotes, an' I b'leeve they'd all leave the camp fur a few ounces."

"Ye—es," drawled the judge, dubiously; "but thar's the Widder Ginneys—she'd pan out a pretty good schoolroom-full with her eight young uns, an' there ain't ounces enough in the diggin's to make her leave while Tom Ginneys's coffin's roostin' under the rocks."

"Then," said Mose, the first speaker, his words escaping with even more difficulty than before, "throw around keards to see who's to marry the widder, an' boss her young uns. The feller that gits the fust Jack's to do the job."

"Meanin' no insult to this highly respectable crowd," said the judge, in a very bland tone, and inviting it to walk up to the bar and specify its consolation, "I don't b'leeve there's one uv yer the widder'd hev." The judge's eye glanced along the line at the bar, and he continued softly, but in decided accents—"Not a cussed one. But," added the judge, passing his pouch to the barkeeper, "if anything's to be done, it must be done lively, fur the stage is pretty nigh here. Tell ye what's ez good ez ennything. We'll crowd around the stage, fust throwin' keards for who's to put out his hoof to be accidently trod onto by the infernal teacher ez he gits out. Then satisfaction must be took out uv the teacher. It'll be a mean job, fur these teachers hevn't the spunk of a coyote, an' ten to one he won't hev no shootin' irons, so the job'll hev to be done with fists."

"Good!" said Mose. "The crowd drinks with me to a square job, and no backin'. Chuck the pasteboards, jedge—The—dickens!" For Mose had got first Jack.

"Square job, and no backin'," said the judge, with a grin. "There's the stage now—hurry up, fellers!"

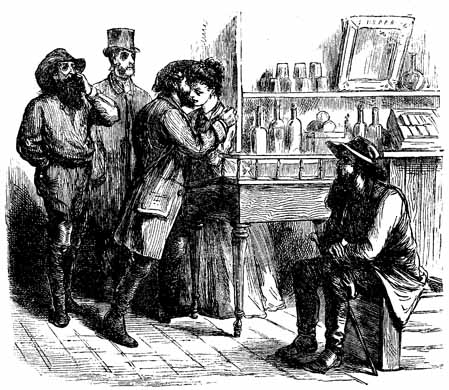

The stage drew up with a crash in front of The Nugget, and the passengers, outside and in, but none looking teacherish, hurried into the saloon. The boys scarcely knew whether to swear from disappointment or gratification, when a start from Mose drew their attention again to the stage. On the top step appeared a small shoe, above which was visible a small section of stocking far whiter and smaller than is usual in the mines. In an instant a similar shoe appeared on the lower step, and the boys saw, successively, the edge of a dress, a waterproof cloak, a couple of small gloved hands, a bright muffler, and a pleasant face covered with brown hair, and a bonnet. Then they heard a cheerful voice say:

"I'm the teacher, gentlemen—can any one show me the schoolhouse?"

The miserable Mose looked ghastly, and tottered. A suspicion of a wink graced the judge's eye, but he exclaimed in a stern, low tone: "Square job, an' no backin'," upon which Mose took to his heels and the Placerville trail.

The judge had been a married man, so he promptly answered:

"I'll take yer thar, mum, ez soon ez I git yer baggage."

"Thank you," said the teacher; "that valise under the seat is all."

The judge extracted a small valise marked "Huldah Brown," offered his arm, and he and the teacher walked off before the astonished crowd as naturally as if the appearance of a modest-looking young lady was an ordinary occurrence at the Flat.

The stage refilled, and rattled away from the dumb and staring crowd, and the judge returned.

"Well, boys," said he, "yer got to marry two women, now, to stop that school, an' you'll find this un more particler than the widder. I just tell yer what it is about that school—it's a-goin' to go on, spite uv any jackasses that wants it broke up; an' any gentleman that's insulted ken git satisfaction by—"

"Who wants it broke up, you old fool?" demanded Toledo, a man who had been named after the city from which he had come, and who had been from the first one of the fiercest opponents of the school. "I move the appointment uv a committee of three to wait on the teacher, see if the school wants anything money can buy, take up subscriptions to git it, an' lay out any feller that don't come down with the dust when he's went fur."

"Hurray!" "Bully!" "Good!" "Sound!" "Them's the talk!" and other sympathetic expressions, were heard from the members of the late anti-school party.

The judge, who, by virtue of age, was the master of ceremonies and general moderator of the camp, very promptly appointed a committee, consisting of Toledo and two miners, whose attire appeared the most respectable in the place, and instructed them to wait on the schoolmarm, and tender her the cordial support of the miners.

Early the next morning the committee called at the schoolhouse, attached to which were two small rooms in which teachers were expected to keep house.

The committee found the teacher "putting to rights" the schoolroom. Her dress was tucked up, her sleeves rolled, her neck hidden by a bright handkerchief, and her hair "a-blowin' all to glory," as Toledo afterward expressed it. Between the exertion, the bracing air, and the excitement caused by the newness of everything, Miss Brown's pleasant face was almost handsome.

"Mornin', marm," said Toledo, raising a most shocking hat, while the remaining committee-men expeditiously ranged themselves behind him, so that the teacher might by no chance look into their eyes.

"Good-morning, gentlemen," said Miss Brown, with a cheerful smile, "please be seated. I suppose you wish to speak of your children?"

Toledo, who was a very young man, blushed, and the whole committee was as uneasy on its feet as if its boots had been soled with fly-blisters. Finally, Toledo answered:

"Not much, marm, seein' we ain't got none. Me an' these gentlemen's a committee from the boys."

"From the boys?" echoed Miss Brown. She had heard so many wonderful things about the Golden State, that now she soberly wondered whether bearded men called themselves boys, and went to school.

"From the miners, washin' along the crick, marm—they want to know what they ken do fur yer," continued Toledo.

"I am very grateful," said Miss Brown; "but I suppose the local school committee—"

"Don't count on them, marm," interrupted Toledo; "they're livin' five miles away, and they're only the preacher, an' doctor, an' a feller that's j'ined the church lately. None uv 'em but the doctor ever shows themselves at the saloon, an' he only comes when there's a diffikilty, an' he's called in to officiate. But the boys—the boys hez got the dust, marm, an' they've got the will. One uv us'll be in often to see what can be done fur yer. Good-mornin', marm."

Toledo raided his hat again, the other committee-men bowed profoundly to all the windows and seats, and then the whole retired, leaving Miss Brown in the wondering possession of an entirely new experience.

"Well?" inquired the crowd, as the committee approached the creek.

"Well," replied Toledo, "she's just a hundred an' thirty pound nugget, an' no mistake—hey, fellers?"

"You bet," promptly responded the remainder of the committee.

"Good!" said the judge. "What does she want?"

Toledo's countenance fell.

"By thunder!" he replied, "we got out 'fore she had a chance to tell us!"

The judge stared sharply upon the young man, and hurriedly turned to hide a merry twitching of his lips.

That afternoon the boys were considerably astonished and scared at seeing the schoolmistress walking quickly toward the creek. The chairman of the new committee was fully equal to the occasion. Mounting a rock, he roared:

"You fellers without no sherts on, git. You with shoes off, put 'em on. Take your pants out uv yer boots. Hats off when the lady comes. Hurry up, now—no foolin'."

The shirtless ones took a lively double-quick toward some friendly bushes, the boys rolled down their sleeves and pantaloons, and one or two took the extra precaution to wash the mud off their boots.

Meanwhile Miss Brown approached, and Toledo stepped forward.

"Anything wrong up at the schoolhouse?" said he.

"Oh, no," replied Miss Brown, "but I have always had a great curiosity to see how gold was obtained. It seems as if it must be very easy to handle those little pans. Don't you—don't you suppose some miner would lend me his pan and let me try just once?"

"Certingly, marm; ev'ry galoot ov'em would be glad of the chance. Here, you fellers—who's got the cleanest pan?"

Half a dozen men washed out their pans, and hurried off with them. Toledo selected one, put in dirt and water, and handed it to Miss Brown.

"Thar you are, marm, but I'm afeared you'll wet your dress."

"Oh, that won't harm," cried Miss Brown, with a laugh which caused one enthusiastic miner to "cut the pigeon-wing."

She got the miner's touch to a nicety, and in a moment had a spray of dirty water flying from the edge of the pan, while all the boys stood in a respectful semicircle, and stared delightedly. The pan empty, Toledo refilled it several times; and, finally, picking out some pebbles and hard pieces of earth, pointed to the dirty, shiny deposit in the bottom of the pan, and briefly remarked:

"Thar 'tis, marm."

"Oh!" screamed Miss Brown, with delight; "is that really gold-dust?"

"That's it," said Toledo. "I'll jest put it up fur yer, so yer ken kerry it."

"Oh, no," said Miss Brown, "I couldn't think of it—it isn't mine."

"You washed it out, marm, an' that makes a full title in these parts."

All of the traditional honesty of New England came into Miss Brown's face in an instant; and, although she, Yankee-like, estimated the value of the dust, and sighingly thought how much easier it was to win gold in that way than by forcing ideas into stupid little heads, she firmly declined the gold, and bade the crowd a smiling good-day.

"Did yer see them little fingers uv hern a-holdin' out that pan?—did yer see her, fellers?" inquired an excited miner.

"Yes, an' the way she made that dirt git, ez though she was useder to washin' than wallopin'," said another.

"Wallopin'!" echoed a staid miner. "I'd gie my claim, an' throw in my pile to boot, to be a young 'un an' git walloped by them playthings of han's."

"Jest see how she throwed dirt an' water on them boots," said another, extending an enormous ugly boot. "Them boots ain't fur sale now—them ain't."

"Them be durned!" contemptuously exclaimed another. "She tramped right on my toes as she backed out uv the crowd."

Every one looked jealously at the last speaker, and a grim old fellow suggested that the aforesaid individual had obtained a trampled foot by fraud, and that each man in camp had, consequently, a right to demand satisfaction of him.

But the judge decided that he of the trampled foot was right, and that any miner who wouldn't take such a chance, whether fraudulently or otherwise, hadn't the spirit of a man in him.

Yankee Sam, the shortest man in camp, withdrew from the crowd, and paced the banks of the creek, lost in thought. Within half an hour Sam was owner of the only store in the place, had doubled the prices of all articles of clothing contained therein, and increased at least six-fold the price of all the white shirts.

Next day the sun rose on Bottle Flat in his usual conservative and impassive manner. Had he respected the dramatic proprieties, he would have appeared with astonished face and uplifted hands, for seldom had a whole community changed so completely in a single night.

Uncle Hans, the only German in the camp, had spent the preceding afternoon in that patient investigation for which the Teutonic mind is so justly noted. The morning sun saw over Hans's door a sign, in charcoal, which read, "SHAVIN' DUN HIER"; and few men went to the creek that morning without submitting themselves to Hans's hands.

Then several men who had been absent from the saloon the night before straggled into camp, with jaded mules and new attire. Carondelet Joe came in, clad in a pair of pants, on which slender saffron-hued serpents ascended graceful gray Corinthian columns, while from under the collar of a new white shirt appeared a cravat, displaying most of the lines of the solar spectrum.

Flush, the Flat champion at poker, came in late in the afternoon, with a huge watch-chain, and an overpowering bosom-pin, and his horrid fingers sported at least one seal-ring each.

Several stove-pipe hats were visible in camp, and even a pair of gloves were reported in the pocket of a miner.

Yankee Sam had sold out his entire stock, and prevented bloodshed over his only bottle of hair-oil by putting it up at a raffle, in forty chances, at an ounce a chance. His stock of white shirts, seven in number, were visible on manly forms; his pocket combs and glasses were all gone; and there had been a steady run on needles and thread. Most of the miners were smoking new white clay pipes, while a few thoughtful ones, hoping for a repetition of the events of the previous day, had scoured their pans to a dazzling brightness.

As for the innocent cause of all this commotion, she was fully as excited as the miners themselves. She had never been outside of Middle Bethany, until she started for California. Everything on the trip had been strange, and her stopping-place and its people were stranger than all. The male population of Middle Bethany, as is usual with small New England villages, consisted almost entirely of very young boys and very old men. But here at Bottle Flat were hosts of middle-aged men, and such funny ones! She was wild to see more of them, and hear them talk; yet, her wildness was no match for her prudence. She sighed to think how slightly Toledo had spoken of the minister on the local committee, and she piously admitted to herself that Toledo and his friends were undoubtedly on the brink of the bottomless pit, and yet—they certainly were very kind. If she could only exert a good influence upon these men—but how?

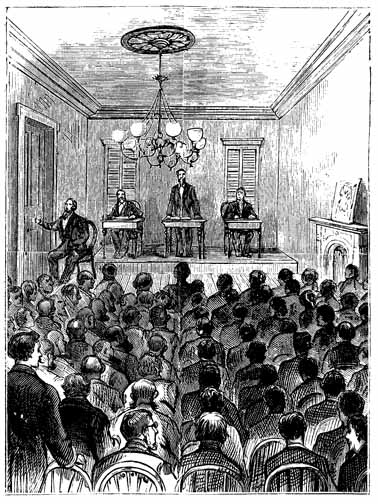

Suddenly she bethought herself, of the grand social centre of Middle Bethany—the singing-school. Of course, she couldn't start a singing-school at Bottle Flat, but if she were to say the children needed to be led in singing, would it be very hypocritical? She might invite such of the miners as were musically inclined to lead the school in singing in the morning, and thus she might, perhaps, remove some of the prejudice which, she had been informed, existed against the school.

She broached the subject to Toledo, and that faithful official had nearly every miner in camp at the schoolhouse that same evening. The judge brought a fiddle, Uncle Hans came with a cornet, and Yellow Pete came grinning in with his darling banjo.

There was a little disappointment all around when the boys declared their ignorance of "Greenville" and "Bonny Doon," which airs Miss Brown decided were most easy for the children to begin with; but when it was ascertained that the former was the air to "Saw My Leg Off," and the latter was identical with the "Three Black Crows," all friction was removed, and the melodious howling attracted the few remaining boys at the saloon, and brought them up in a body, led by the barkeeper himself.

The exact connection between melody and adoration is yet an unsolved religio-psychological problem. But we all know that everywhere in the habitable globe the two intermingle, and stimulate each other, whether the adoration be offered to heavenly or earthly objects. And so it came to pass that, at the Bottle Flat singing-school, the boys looked straight at the teacher while they raised their tuneful voices; that they came ridiculously early, so as to get front seats; and that they purposely sung out of tune, once in a while, so as to be personally addressed by the teacher.

And she—pure, modest, prudent, and refined—saw it all, and enjoyed it intensely. Of course, it could never go any further, for though there was in Middle Bethany no moneyed aristocracy, the best families scorned alliances with any who were undegenerate, and would not be unequally yoked with those who drank, swore, and gambled—let alone the fearful suspicion of murder, which Miss Brown's imagination affixed to every man at the Flat.

But the boys themselves—considering the unspeakable contempt which had been manifested in the camp for the profession of teaching, and for all who practiced it—the boys exhibited a condescension truly Christian. They vied with each other in manifesting it, and though the means were not always the most appropriate, the honesty of the sentiment could not be doubted.

One by one the greater part of the boys, after adoring and hoping, saw for themselves that Miss Brown could never be expected to change her name at their solicitation. Sadder but better men, they retired from the contest, and solaced themselves by betting on the chances of those still "on the track," as an ex-jockey tersely expressed the situation.

There was no talk of "false hearted" or "fair temptress," such as men often hear in society; for not only had all the tenderness emanated from manly breasts alone, but it had never taken form of words.

Soon the hopeful ones were reduced to half a dozen of these. Yankee Sam was the favorite among the betting men, for Sam, knowing the habits of New England damsels, went to Placerville one Friday, and returned next day with a horse and buggy. On Sunday he triumphantly drove Miss Brown to the nearest church. Ten to one was offered on Sam that Sunday afternoon, as the boys saw the demure and contented look on Miss Brown's face as she returned from church. But Samuel followed in the sad footsteps of many another great man, for so industriously did he drink to his own success that he speedily developed into a bad case of delirium tremens.

Then Carondelet Joe, calmly confident in the influence of his wonderful pants, led all odds in betting. But one evening, when Joe had managed to get himself in the front row and directly before the little teacher, that lady turned her head several times and showed signs of discomfort. When it finally struck the latter that the human breath might, perhaps, waft toward a lady perfumes more agreeable than those of mixed drinks, he abruptly quitted the school and the camp.

Flush, the poker champion, carried with him to the singing-school that astounding impudence which had long been the terror and admiration of the camp. But a quality which had always seemed exactly the thing when applied to poker seemed to the boys barely endurable when displayed toward Miss Brown.

One afternoon, Flush indiscreetly indulged in some triumphant and rather slighting remarks about the little teacher. Within fifteen minutes, Flush's final earthly home had been excavated, and an amateur undertaker was making his coffin.

An untimely proposal by a good-looking young Mexican, and his prompt rejection, left the race between Toledo and a Frenchman named Lecomte. It also left Miss Brown considerably frightened, for until now she had imagined nothing more serious than the rude admiration which had so delighted her at first.

But now, who knew but some one else would be ridiculous? Poor little Miss Brown suffered acutely at the thought of giving pain, and determined to be more demure than ever.

But alas! even her agitation seemed to make her more charming to her two remaining lovers.

Had the boys at the saloon comprehended in the least the cause of Miss Brown's uneasiness, they would have promptly put both Lecomte and Toledo out of the camp, or out of the world. But to their good-natured, conceited minds it meant only that she was confused, and unable to decide, and unlimited betting was done, to be settled upon the retirement of either of the contestants.

And while patriotic feeling influenced the odds rather in Toledo's favor, it was fairly admitted that the Frenchman was a formidable rival.

To all the grace of manner, and the knowledge of women that seems to run in Gallic blood, he was a man of tolerable education and excellent taste. Besides, Miss Brown was so totally different from French women, that every development of her character afforded him an entirely new sensation, and doubled his devotion.

Toledo stood his ground manfully, though the boys considered it a very bad sign when he stopped drinking, and spent hours in pacing the ground in front of his hut, with his hands behind him, and his eyes fixed on the ground.

Finally, when he was seen one day to throw away his faithful old pipe, heavy betters hastened to "hedge" as well as they might.

Besides, as one of the boys truthfully observed, "He couldn't begin to wag a jaw along with that Frenchman."

But, like many other young men, he could talk quite eloquently with his eyes, and as the language of the eyes is always direct, and purely grammatical, Miss Brown understood everything they said, and, to her great horror, once or twice barely escaped talking back.

The poor little teacher was about to make the whole matter a subject of special prayer, when a knock at the door startled her.

She answered it, and beheld the homely features of the judge.

"I just come in to talk a little matter that's been botherin' me some time. Ye'll pardon me ef I talk a little plain?" said he.

"Certainly," replied the teacher, wondering if he, too, had joined her persecutors.

"Thank ye," said the judge, looking relieved. "It's all right. I've got darters to hum ez big ez you be, an' I want to talk to yer ez ef yer was one uv 'em."

The judge looked uncertain for a moment, and then proceeded:

"That feller Toledo's dead in love with yer—uv course you know it, though 'tain't likely he's told yer.' All I want to say 'bout him is, drop him kindly. He's been took so bad sence you come, that he's stopped drinkin' an' chewin' an' smokin' an' cussin', an' he hasn't played a game at The Nugget sence the first singin'-school night. Mebbe this all ain't much to you, but you've read 'bout that woman that was spoke well uv fur doin' what she could. He's the fust feller I've ever seen in the diggin's that went back on all the comforts uv life, an'—an' I've been a young man myself, an' know how big a claim it's been fur him to work. I ain't got the heart to see him spiled now; but he will be ef, when yer hev to drop him, yer don't do it kindly. An'—just one thing more—the quicker he's out of his misery the better."

The old jail-bird screwed a tear out of his eye with a dirty knuckle, and departed abruptly, leaving the little teacher just about ready to cry herself.

But before she was quite ready, another knock startled her.

She opened the door, and let in Toledo himself.

"Good-evin', marm," said he, gravely. "I just come in to make my last 'fficial call, seein' I'm goin' away to-morrer. Ez there anything the schoolhouse wants I ken git an' send from 'Frisco?"

"Going away!" ejaculated the teacher, heedless of the remainder of Toledo's sentence.

"Yes, marm; goin' away fur good. Fact is, I've been tryin' to behave myself lately, an' I find I need more company at it than I git about the diggin's. I'm goin' some place whar I ken learn to be the gentleman I feel like bein'—to be decent an' honest, an' useful, an' there ain't anybody here that keers to help a feller that way—nobody."

The ancestor of the Browns of Middle Bethany was at Lexington on that memorable morning in '75, and all of his promptness and his courage, ten times multiplied, swelled the heart of his trembling little descendant, as she faltered out:

"There's one."

"Who?" asked Toledo, before he could raise his eyes.

But though Miss Brown answered not a word, he did not repeat his question, for such a rare crimson came into the little teacher's face, that he hid it away in his breast, and acted as if he would never let it out again.

Another knock at the door.

Toledo dropped into a chair, and Miss Brown, hastily smoothing back her hair, opened the door, and again saw the judge.

"I jest dropped back to say—" commenced the judge, when his eye fell upon Toledo.

He darted a quick glance at the teacher, comprehended the situation at once, and with a loud shout of "Out of his misery, by thunder!" started on a run to carry the news to the saloon.

Miss Brown completed her term, and then the minister, who was on the local Board, was called in to formally make her tutor for life to a larger pupil. Lecomte, with true French gallantry, insisted on being groomsman, and the judge gave away the bride. The groom, who gave a name very different from any ever heard at the Flat, placed on his bride's finger a ring, inscribed within, "Made from gold washed by Huldah Brown." The little teacher has increased the number of her pupils by several, and her latest one calls her grandma.

"Ye don't say?"

"I do though."

"Wa'al, I never."

"Nuther did I—adzackly."

"Don't be provokin', Ephr'm—what makes you talk in that dou'fle way?"

"Wa'al, ma, the world hain't all squeezed into this yere little town of Crankett. I've been elsewheres, some, an' I've seed some funny things, and likewise some that wuzn't so funny ez they might be."

"P'r'aps ye hev, but ye needn't allus be a-settin' other folks down. Mebbe Crankett ain't the whole world, but it's seed that awful case of Molly Capins, and the shipwreck of thirty-four, when the awful nor'easter wuz, an'—"

"Wa'al, wa'al, ma—don't let's fight 'bout it," said Ephr'm, with a sigh, as he tenderly scraped down a new ax-helve with a piece of glass, while his wife made the churn-dasher hurry up and down as if the innocent cream was Ephr'm's back, and she was avenging thereon Ephr'm's insults to Crankett and its people.

Deacon Ephraim Crankett was a descendant of the founder of the village, and although now a sixty-year old farmer, he had in his lifetime seen considerable of the world. He had been to the fishing-banks a dozen times, been whaling twice, had carried a cargo of wheat up the Mediterranean, and had been second officer of a ship which had picked up a miscellaneous cargo in the heathen ports of Eastern Asia.

He had picked up a great many ideas, too, wherever he had been, and his wife was immensely proud of him and them, whenever she could compare them with the men and ideas which existed at Crankett; but when Ephr'm displayed his memories and knowledge to her alone—oh, that was a very different thing.

"Anyhow," resumed Mrs. Crankett, raising the lid of the churn to see if there were any signs of butter, "it's an everlastin' shame. Jim Hockson's a young feller in good standin' in the Church, an' Millie Botayne's an unbeliever—they say her father's a reg'lar infidel."

"Easy, ma, easy," gently remonstrated Ephr'm. "When he seed you lookin' at his pet rose-bush on yer way to church las' Sunday, didn't he hurry an' pull two or three an' han' 'em to ye?"

"Yes, an' what did he hev' in t'other han'?—a Boasting paper, an' not a Sunday one, nuther! Millicent ain't a Christian name, nohow ye can fix it—it amounts to jest 'bout's much ez she does, an' that's nothing. She's got a soft face, an' purty hair—ef it's all her own, which I powerfully doubt—an' after that ther's nothin' to her. She's never been to sewin' meetin', an' she's off a boatin' with that New York chap every Saturday afternoon, instead of goin' to the young people's prayer-meetin's."

"She's most supported Sam Ransom's wife an' young uns since Sam's smack was lost," suggested Ephr'm.

"That's you, Deac'n Crankett," replied his wife, "always stick up for sinners. P'r'aps you'd make better use of your time ef you'd examine yer own evidences."

"Wa'al, wife," said the deacon, "she's engaged to that New York feller, ez you call Mr. Brown, so there's no danger of Jim bein' onequally yoked with an onbeliever. An' I wish her well, from the bottom of my heart."

"I don't," cried Mrs. Crankett, giving the dasher a vicious push, which sent the cream flying frantically up to the top of the churn; "I hope he'll turn out bad, an' her pride'll be tuk down ez—"

The deacon had been long enough at sea to know the signs of a long storm, and to know that prudence suggested a prompt sailing out of the course of such a storm, when possible; so he started for the door, carrying the glass and ax-helve with him. Suddenly the door opened, and a female figure ran so violently against the ax-helve, that the said figure was instantly tumbled to the floor, and seemed an irregular mass of faded pink calico, and subdued plaid shawl.

"Miss Peekin!" exclaimed Mrs. Crankett, dropping the churn-dasher and opening her eyes.

"Like to ha' not been," whined the figure, slowly arising and giving the offending ax-helve a glance which would have set it on fire had it not been of green hickory; "but—hev you heerd?"

"What?" asked Mrs. Crankett, hastily setting a chair for the newcomer, while Ephr'm, deacon and sixty though he was, paused in his almost completed exit.

"He's gone!" exclaimed Miss Peekin.

"Oh, I heerd Jim hed gone to Califor—"

"Pshaw!" said Miss Peekin, contemptuously; "that was days ago! I mean Brown—the New York chap—Millie Botayne's lover!"

"Ye don't?"

"But I do; an' what's more, he had to. Ther wuz men come after him in the nighttime, but he must hev heard 'em, fur they didn't find him in his room, an' this mornin' they found that his sailboat was gone, too. An' what's more, ther's a printed notice up about him, an' he's a defaulter, and there's five thousand dollars for whoever catches him, an' he's stole twenty-five, an' he's all described in the notice, as p'ticular as if he was a full-blood Alderney cow."

"Poor fellow," sighed the deacon, for which interruption he received a withering glance from Miss Peekin.

"They say Millie's a goin' on awful, and that she sez she'll marry him now if he'll come back. But it ain't likely he'll be such a fool; now he's got so much money, he don't need hern. Reckon her an' her father won't be so high an' mighty an' stuck up now. It's powerful discouragin' to the righteous to see the ungodly flourishin' so, an' a-rollin' in ther wealth, when ther betters has to be on needles all year fur fear the next mack'ril catch won't 'mount to much. The idee of her bein' willin' to marry a defaulter! I can't understand it."

"Poor girl!" sighed Mrs. Crankett, wiping one eye with the corner of her apron. "I'd do it myself, ef I was her?"

The deacon dropped the ax-helve, and gave his wife a tender kiss on each eye.

Perhaps Mr. Darwin can tell inquirers why, out of very common origin, there occasionally spring beings who are very decided improvements on their progenitors; but we are only able to state that Jim Hockson was one of these superior beings, and was himself fully aware of the fact. Not that he was conceited at all, for he was not, but he could not help seeing what every one else saw and acknowledged.

Every one liked him, for he was always kind in word and action, and every one was glad to be Jim Hockson's friend; but somehow Jim seemed to consider himself his best company.

His mackerel lines were worked as briskly as any others when the fish were biting; but when the fish were gone, he would lean idly on the rail, and stare at the waves and clouds; he could work a cranberry-bog so beautifully that the people for miles around came to look on and take lessons; yet, when the sun tried to hide in the evening behind a ragged row of trees on a ridge beyond Jim's cranberry-patch, he would lean on his spade, and gaze until everything about him seemed yellow.

He read the Bible incessantly, yet offended alike the pious saints and critical sinners by never preaching or exhorting. And out of everything Jim Hockson seemed to extract what it contained of the ideal and the beautiful; and when he saw Millicent Botayne, he straightway adored the first woman he had met who was alike beautiful, intelligent and refined. Miss Millie, being human, was pleased by the admiration of the handsome, manly fellow who seemed so far the superior of the men of his class; but when, in his honest simplicity, he told her that he loved her, she declined his further attentions in a manner which, though very delicate and kind, opened Jim's blue eyes to some sad things he had never seen before.

He neither got drunk, nor threatened to kill himself, nor married the first silly girl he met; but he sensibly left the place where he had suffered so greatly, and, in a sort of sad daze, he hurried off to hide himself in the newly discovered gold-fields of California. Perhaps he had suddenly learned certain properties of gold which were heretofore unknown to him; at any rate, it was soon understood at Spanish Stake, where he had located himself, that Jim Hockson got out more gold per week than any man in camp, and that it all went to San Francisco.

"Kind of a mean cuss, I reckon," remarked a newcomer, one day at the saloon, when Jim alone, of the crowd present, declined to drink with him.

"Not any!" replied Colonel Two, so called because he had two eyes, while another colonel in the camp had but one. "An' it's good for you, stranger," continued the colonel, "that you ain't been long in camp, else some of the boys 'ud put a hole through you for sayin' anything 'gainst Jim; for we all swear by him, we do. He don't carry shootin'-irons, but no feller in camp dares to tackle him; he don't cuss nobody, but ev'rybody does just as he asks 'em to. As to drinkin', why, I'd swear off myself, ef 'twud make me hold a candle to him. Went to old Bermuda t'other day, when he was ravin' tight and layin' for Butcher Pete with a shootin'-iron, an' he actilly talked Bermuda into soakin' his head an' turnin' in—ev'rybody else was afeared to go nigh old Bermuda that day."

The newcomer seemed gratified to learn that Jim was so peaceable a man—that was the natural supposition, at least—for he forthwith cultivated Jim with considerable assiduity, and being, it was evident, a man of considerable taste and experience, Jim soon found his companionship very agreeable and he lavished upon his new acquaintance, who had been nicknamed Tarpaulin, the many kind and thoughtful attentions which had endeared Jim to the other miners.

The two men lived in the same hut, staked claims adjoining each other, and Tarpaulin, who had been thin and nervous-looking when he first came to camp, began to grow peaceable and plump under Jim's influence.

One night, as Jim and Tarpaulin lay chatting before a fire in their hut, they heard a thin, wiry voice in the next hut inquiring:

"Anybody in this camp look like this?"

Tarpaulin started.

"That's a funny question," said he; "let's see who and what the fellow is."

And then Tarpaulin started for the next hut. Jim waited some time, and hearing low voices in earnest conversation, went next door himself.

Tarpaulin was not there, but two small, thin, sharp-eyed men were there, displaying an old-fashioned daguerreotype of a handsome-looking young man, dressed in the latest New York style; and more than this Jim did not notice.

"Don't know him, mister," said Colonel Two, who happened to be the owner of the hut. "Besides ef, as is most likely, he's growed long hair an' a beard since he left the States, his own mother wouldn't know him from George Washington. Brother o' yourn?"

"No," said one of the thin men; "he's—well, the fact is, we'll give a thousand dollars to any one who'll find him for us in twenty-four hours."

"Deppity sheriffs?" asked the colonel, retiring somewhat hastily under his blankets.

"About the same thing," said one of the thin men, with a sickly smile.

"Git!" roared the colonel, suddenly springing from his bed, and cocking his revolver. "I b'lieve in the Golden Rule, I do!"

The detectives, with the fine instinct peculiar to their profession, rightly construed the colonel's action as a hint, and withdrew, and Jim retired to his own hut, and fell asleep while waiting for his partner.

Morning came, but no Tarpaulin; dinner-time arrived, but Jim ate alone, and was rather blue. He loved a sociable chat, and of late Tarpaulin had been almost his sole companion.

Evening came, but Tarpaulin came not.

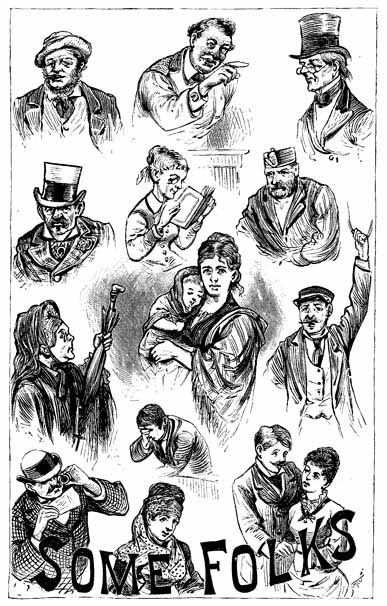

Jim couldn't abide the saloon for a whole evening, so he lit a candle in his own hut, and attempted to read.

Tarpaulin was a lover of newspapers—it seemed to Jim he received more papers than all the remaining miners put together.

Jim thought he would read some of these same papers, and unrolled Tarpaulin's blankets to find them, when out fell a picture-case, opening as it fell. Jim was about to close it again, when he suddenly started, and exclaimed:

"Millicent Botayne!"

He held it under the light, and examined it closely.

There could be no doubt as to identity—there were the same exquisite features which, a few months before, had opened to Jim Hockson a new world of beauty, and had then, with a sweet yet sad smile, knocked down all his fair castles, and destroyed all his exquisite pictures.

Strange that it should appear to him now, and so unexpectedly, but stranger did it seem to Jim that on the opposite side of the case should be a portrait which was a duplicate of the one shown by the detectives!

"That rascal Brown!" exclaimed Jim. "So he succeeded in getting her, did he? But I shouldn't call him names; he had as much right to make love to her as I. God grant he may make her happy! And he is probably a very fine fellow—must be, by his looks."

Suddenly Jim started, as if shocked by an electric battery. Hiding all the hair and beard of the portrait, he stared at it a moment, and exclaimed:

"Tarpaulin!"

"Both gone!" exclaimed Colonel Two, hurrying into the saloon, at noon.

"Both gone?" echoed two or three men.

"Yes," said the colonel; "and the queerest thing is, they left ev'rything behind—every darned thing! I never did see such a stampede afore—I didn't! Nobody's got any idee of whar they be, nor what it's 'bout neither."

"Don't be too sartain, colonel!" piped Weasel, a self-contained mite of a fellow, who was still at work upon his glass, filled at the last general treat, although every one else had finished so long ago that they were growing thirsty again—"don't be too sartain. Them detectives bunked at my shanty last night."

"The deuce they did!" cried the colonel. "Good the rest of us didn't know it."

"Well," said Weasel, moving his glass in graceful circles, to be sure that all the sugar dissolved, "I dunno. It's a respectable business, an' I wanted to have a good look at 'em."

"What's that got to do with Jim and Tarpaulin?" demanded the colonel, fiercely.

"Wait, and I'll tell you," replied Weasel, provokingly, taking a leisurely sip at his glass. "Jim come down to see 'em—"

"What?" cried the colonel.

"An' told 'em he knew their man, an' would help find him," continued Weasel. "They offered him the thousand dollars—"

"Oh, Lord! oh, Lord!" groaned the colonel; "who's a feller to trust in this world! The idee of Jim goin' back on a pardner fur a thousand! I wouldn't hev b'lieved he'd a-done it fur a million!"

"An' he told 'em he'd cram it down their throats if they mentioned it again."

"Bully! Hooray fur Jim!" shouted the colonel. "What'll yer take, fellers? Fill high! Here's to Jim! the feller that b'lieves his friend's innercent!"

The colonel looked thoughtfully into his glass, and remarked, as if to his own reflection therein, "Ain't many such men here nur nowhars else!" after which he drank the toast himself.

"But that don't explain what Tarpaulin went fur," said the colonel, suddenly.

"Yes, it does," said the exasperating Weasel, shutting his thin lips so tightly that it was hard to see where his mouth was.

"What?" cried the colonel. "'Twould take a four-horse corkscrew to get anything out o' you, you dried-up little scoundrel!"

"Why!" replied Weasel, greatly pleased by the colonel's compliment, "after what you said about hair and beard hidin' a man, one of them fellers cut a card an' held it over the picture, so as to hide hair an' chin. The forehead an' face an' nose an' ears wuz Tarpaulin's, an' nobody else's."

"Lightning's blazes!" roared the colonel, "Ha, ha, ha! why, Tarpaulin hisself came into my shanty, an' looked at the pictur', an' talked to them 'bout it! Trot out yer glassware, barkeeper—got to drink to a feller that's ez cool ez all that!"

The boys drank with the colonel, but they were too severely astonished to enjoy the liquor particularly. In fact, old Bermuda, who had never taken anything but plain rye, drank three fingers of claret that day, and did not know of it until told.

The colonel's mind was unusually excited. It seemed to him there were a number of probabilities upon which to hang bets. He walked outside, that his meditation might be undisturbed, but in an instant he was back, crying:

"Lady comin'!"

Shirt-sleeves and trowsers-legs were hurriedly rolled down, shirt-collars were buttoned, hats were dusted, and then each man went leisurely out, with the air of having merely happened to leave the saloon—an air which imposed upon no disinterested observer.

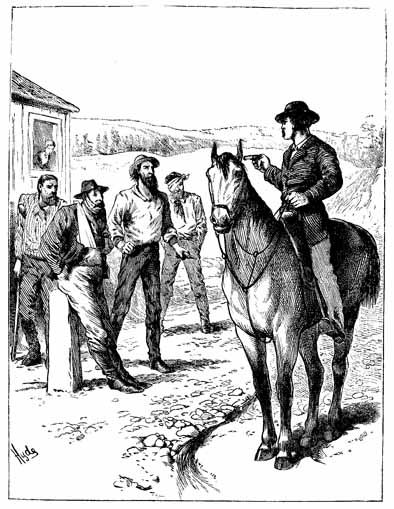

Coming up the trail beside the creek were a middle-aged gentleman and a young lady, both on horseback.

The gentleman's dress and general style plainly indicated that he was not a miner, nor a storekeeper, nor a barkeeper; while it was equally evident that the lady was neither a washerwoman, a cook, nor a member of either of the very few professions which were open to ladies on the Pacific Coast in those days.

This much every miner quickly decided for himself; but after so deciding, each miner reached the uttermost extremity of his wits, and devoted himself to staring.

The couple reined up before the saloon, and the gentleman drew something small and black and square from his pocket.

"Gentlemen," said he, "we are looking for an old friend of ours, and have traced him to this camp. We scarcely know whether it would be any use to give his name, but here is his picture. Can any one remember having seen the person here?"

Every one looked toward Colonel Two, he being the man with the most practical tongue in camp.

The colonel took the picture, and Weasel slipped up behind him and looked over his shoulder. The colonel looked at the picture, abruptly handed it back, looked at the young lady, and then gazed vacantly into space, and seemed very uncomfortable.

"Been here, but gone," said the colonel, at length.

"Where did he go, do you know?" asked the gentleman, while the lady's eyes dropped wearily.

"Nobody knows—only been gone a day or two," replied the colonel.

The colonel had a well-developed heart, and, relying on what he considered the correct idea of Jim Hockson's mission, ventured to say:

"He'll be back in a day or two—left all his things."

Suddenly Weasel raised his diminutive voice, and said:

"The detec—"

The determined grip of the colonel's hand interrupted the communication which Weasel attempted to make, and the colonel hastily remarked:

"Ther's a feller gone for him that's sure to fetch him back."

"Who—who is it?" asked the young lady, hesitatingly.

"Well, ma'am," said the colonel, "as yer father—I s'pose, leastways—said, 'tain't much use to give names in this part of the world, but the name he's goin' by is Jim Hockson."

The young lady screamed and fell.

"Whether to do it or not, is what bothers me," soliloquized Mr. Weasel, pacing meditatively in front of the saloon. "The old man offers me two thousand to get Tarpaulin away from them fellers, and let him know where to meet him an' his daughter. Two thousand's a pretty penny, an' the bein' picked out by so smart a lookin' man is an honor big enough to set off agin' a few hundred dollars more. But, on t'other hand, if they catch him, they'll come back here, an' who knows but what they'll want the old man an' girl as bad as they wanted Tarpaulin? A bird in the hand's worth two in the bush—better keep near the ones I got, I reckon. Here they come now!"

As Mr. Weasel concluded his dialogue with himself, Mr. Botayne and Millicent approached, in company with the colonel.

The colonel stopped just beyond the saloon, and said:

"Now, here's your best p'int—you can see the hill-trail fur better'n five miles, an' the crick fur a mile an' a half. I'll jest hev a shed knocked together to keep the lady from the sun. An' keep a stiff upper lip, both of yer—trust Jim Hockson; nobody in the mines ever knowed him to fail."

Millicent shivered at the mention of Jim's name, and the colonel, unhappily ignorant of the cause of her agitation, tried to divert her mind from the chances of harm to Tarpaulin by growing eloquent in praise of Jim Hockson.

Suddenly the colonel himself started and grew pale. He quickly recovered himself, however, and, with the delicacy of a gentleman, walked rapidly away, as Millicent and her father looked in the direction from which the colonel's surprise came.

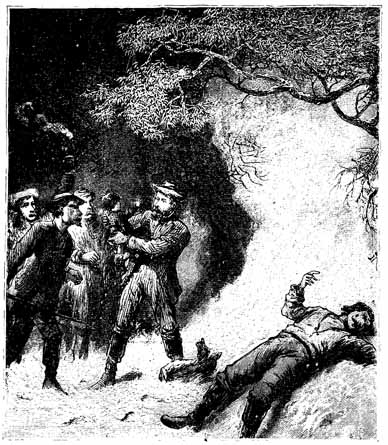

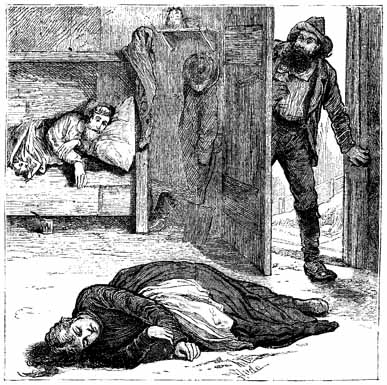

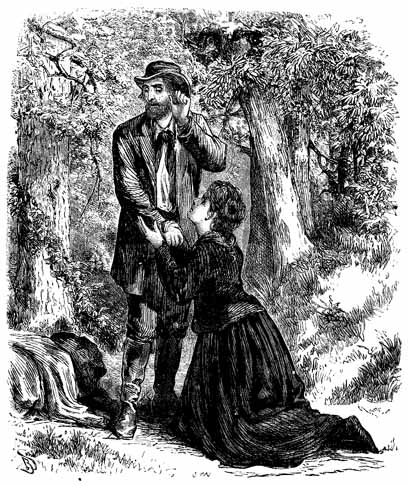

There, handcuffed, with beard and hair singed close, clothes torn and face bleeding, walked Ethelbert Brown between the two detectives, while Jim Hockson, with head bowed and hands behind his back, followed a few yards behind.

Some one gave the word at the saloon, and the boys hurried out, but the colonel pointed significantly toward the sorrowful couple, while with the other hand he pointed an ugly pistol, cocked, toward the saloon.

Millicent hurried from her father's side, and flung her arms about the sorry figure of her lover; and Jim Hockson, finding his pathway impeded, raised his eyes, and then blushed violently.

"Sorry for you, sir," said one of the detectives, touching his hat to Mr. Botayne, "but can't help being glad we got a day ahead of you."

"What amount of money will buy your prisoner?" demanded the unhappy father.

"Beg pardon, sir—very sorry, but—we'd be compounding felony in that case, you know," replied one of the officers, gazing with genuine pity on the weeping girl.

"Don't worry," whispered the colonel in Mr. Botayne's ear; "we'll clean out them two fellers, and let Tarpaulin loose again. Ev'ry feller come here for somethin' darn it!" with which sympathizing expression the colonel again retired.

"I'll give you as much as the bank offers," said Mr. Botayne.

"Very sorry, sir; but can't," replied the detective. "We'd be just as bad then in the eyes of the law as before. Reward, five thousand, bank lose twenty-five thousand—thirty thousand, in odd figures, is least we could take. Even that wouldn't be reg'lar; but it would be a safe risk, seeing all the bank cares for's to get its money back."

Mr. Botayne groaned.

"We'll make it as pleasant as we can for you, sir," continued the detective, "if you and the lady'll go back on the ship with us. We'll give him the liberty of the ship as soon as we're well away from land. We'd consider it our duty to watch him, of course; but we'd try to do it so's not to give offense—we've got hearts, though we are in this business. Hope you can buy him clear when you get home, sir?"

"I've sacrificed everything to get here—I can never clear him," sighed Mr Botayne.

"I can!" exclaimed a clear, manly voice.

Millicent raised her eyes, and for the first time saw Jim Hockson.

She gave him a look in which astonishment, gratitude and fear strove for the mastery, and he gave her a straightforward, honest, respectful look in return.

The two detectives dropped their lower jaws alarmingly, and raised their eyebrows to their hat-rims.

"The bank at San Francisco has an agent here," said Jim. "Colonel, won't you fetch him?"

The colonel took a lively double-quick, and soon returned with a business-looking man.

"Mr. Green," said Jim, "please tell me how much I have in your bank?"

The clerk looked over a small book he extracted from his pocket, and replied, briefly:

"Over two thousand ounces."

"Please give these gentlemen a check, made whatever way they like it, for the equivalent of thirty thousand dollars. I'll sign it," said Jim.

The clerk and one of the detectives retired to an adjacent hut, and soon called Jim. Jim joined them, and immediately he and the officer returned to the prisoner.

"It's all right, Maxley," said the officer; "let him go."

The officer removed the handcuffs, and Ethelbert Brown was free. His first motion was to seize Jim's hand.

"Hockson, tell me why you helped those detectives," said he.

"Revenge!" replied Jim.

"For what?" cried Brown, changing color.

"Gaining Millie Botayne's love," replied Jim.

Brown looked at Millicent, and read the story from her face.

He turned toward Jim a wondering look, and asked, slowly:

"Then, why did you free me?"

"Because she loved you," said Jim, and then he walked quietly away.

"Why, Miss Peekin!"

"It's a fact: Eben Javash, that went out better'n a year ago, hez got back, and he wuz at the next diggins an' heerd all about it. 'T seems the officers ketched Brown, an' Jim Hockson gave 'em thirty thousand dollars to pay them an' the bank too, and then they let him go. Might's well ha kept his money, though, seein' Brown washed overboard on the way back.

"I ain't a bettin' man," said the deacon, "but I'd risk our white-faced cow that them thirty thousand dollars preached the greatest sermon ever heerd in Californy—ur in Crankett either."

Miss Peekin threw a withering glance at the deacon; it was good he was not on trial for heresy, with Miss Peekin for judge and jury. She continued:

"Eben says there was a fellow named Weasel that hid close by, an' heerd all 'twas said, and when he went to the rum-shop an' told the miners, they hooray'd for Jim ez ef they wuz mad. Just like them crazy fellers—they hain't no idee when money's wasted."

"The Lord waste all the money in the world that way!" devoutly exclaimed the deacon.

"An' that feller Weasel," continued Miss Peekin, giving the deacon's pet cat a vicious kick, "though he'd always been economical, an' never set a bad example before by persuadin' folk to be intemprit, actilly drored a pistol, and fit with a feller they called Colonel Two—fit for the chance of askin' the crowd to drink to Jim Hockson, an' then went aroun' to all the diggins, tellin' about Jim, an' wastin' his money treatin' folks to drink good luck to Jim. Disgraceful!"

"It's what I'd call a powerful conversion," remarked the deacon.

"But ther's more," said Miss Peekin, with a sigh, and yet with an air of importance befitting the bearer of wonderful tidings.

"What?" eagerly asked Mrs. Crankett.

"Jim's back," said Miss Peekin.

"Mercy on us!" cried Mrs. Crankett.

"The Lord bless and prosper him!" earnestly exclaimed the deacon.

"Well," said Miss Peekin, with a disgusted look, "I s'pose He will, from the looks o' things; fur Eben sez that when Weasel told the fellers how it all wuz, they went to work an' put gold dust in a box fur Jim till ther wus more than he giv fur Brown, an' fellers from all round's been sendin' him dust ever since. He's mighty sight the richest man anywhere near this town."

"Good—bless the Lord!" said the deacon, with delight.

"Ye hain't heerd all of it, though," continued Miss Peekin, with a funereal countenance. "They're going to be married."

"Sakes alive '" gasps Mrs. Crankett.

"It's so," said Miss Peekin; "an' they say she sent for him, by way of the Isthmus, an' he come back that way. Bad enough to marry him, when poor Brown hain't been dead six months, but to send for him—"

"Wuz a real noble, big-hearted, womanly thing to do," declared Mrs. Crankett, snatching off her spectacles; "an' I'd hev done it myself ef I'd been her."

The deacon gave his old wife an enthusiastic hug; upon seeing which Miss Peekin hastily departed, with a severely shocked expression of countenance and a nose aspiring heavenward.

Black Hat was, in 1851, about as peaceful and well-regulated a village as could be found in the United States.

It was not on the road to any place, so it grew but little; the dirt paid steadily and well, so but few of the original settlers went away.

The march of civilization, with its churches and circuses, had not yet reached Black Hat; marriages never convulsed the settlement with the pet excitement of villages generally, and the inhabitants were never arrayed at swords' point by either religion, politics or newspapers.

To be sure, the boys gambled every evening and all day Sunday; but a famous player, who once passed that way on a prospecting-trip, declared that even a preacher would get sick of such playing; for, as everybody knew everybody else's game, and as all men who played other than squarely had long since been required to leave, there was an utter absence of pistols at the tables.

Occasional disagreements took place, to be sure—they have been taking place, even among the best people, since the days of Cain and Abel; but all difficulties at Black Hat which did not succumb to force of jaw were quietly locked in the bosoms of the disputants until the first Sunday.

Sunday, at Black Hat, orthodoxically commenced at sunset on Saturday, and was piously extended through to working-time on Monday morning, and during this period of thirty-six hours there was submitted to arbitrament, by knife or pistol, all unfinished rows of the week.

On Sunday was also performed all of the hard drinking at Black Hat; but through the week the inhabitants worked as steadily and lived as peacefully as if surrounded by church-steeples court-houses and jails.

Whether owing to the inevitable visitations of the great disturber of affairs in the Garden of Eden, or only in the due course of that developement which affects communities as well as species, we know not, but certain it is that suddenly the city fathers at Black Hat began to wear thoughtful faces and wrinkled brows, to indulge in unusual periods of silence, and to drink and smoke as if these consoling occupations were pursued more as matters of habit than of enjoyment.

The prime cause of the uneasiness of these good men was a red-faced, red-haired, red-whiskered fellow, who had been nicknamed "Captain," on account of the military cut of the whiskers mentioned above.

The captain was quite a good fellow; but he was suffering severely from "the last infirmity of noble minds"—ambition.

He had gone West to make a reputation, and so openly did he work for it that no one doubted his object; and so untiring and convincing was he, that, in two short weeks, he had persuaded the weaker of the brethren at Black Hat that things in general were considerably out of joint. And as a, little leaven leaveneth the whole lump, every man at Black Hat was soon discussing the captain's criticisms, and was neglecting the more peaceable matters of cards and drink, which had previously occupied their leisure hours.

The captain was always fully charged with opinions on every subject, and his eloquent voice was heard at length on even the smallest matter that interested the camp. One day a disloyal miner remarked:

"Captain's jaw is a reg'lar air-trigger; reckon he'll run the camp when Whitey leaves."

Straightway a devout respecter of the "powers that be" carried the remark to Whitey, the chief of the camp.

Now, it happened that Whitey, an immense but very peaceable and sensible fellow, had just been discussing with some of his adherents the probable designs of the captain, and this new report seemed to arrive just in time, for Whitey instantly said:

"Thar he goes agin, d'ye see, pokin' his shovel in all aroun'. Now, ef the boys want me to leave, they kin say so, an' I'll go. 'Tain't the easiest claim in the world to work, runnin' this camp ain't, an' I'll never hanker to be chief nowhar else; but seein' I've stuck to the boys, an' seen 'em through from the fust, 'twouldn't be exactly gent'emanly, 'pears to me."

And for a moment Whitey hid his emotions in a tin cup, from which escaped perfumes suggesting the rye-fields of Kentucky.

"Nobody wants you to go, Whitey," said Wolverine, one of the chief's most faithful supporters. "Didn't yer kick that New Hampshire feller out of camp when he kept a-sayin' the saloon wuz the gate o' hell?"

"Well," said the chief, with a flush of modest pride, "I don't deny it; but I wont remind the boys of it, ef they've forgot it."

"An' didn't yer go to work," said another, "when all the fellers was a-askin' what was to be done with them Chinesers—didn't yer just order the boys to clean 'em out to wunst?"

"That ain't the best thing yer dun, neither!" exclaimed a third. "I wonder does any of them galoots forgit how the saloon got a-fire when ev'rybody was asleep—how the chief turned out the camp, and after the barkeeper got out the door, how the chief rushed in an' rolled out all three of the barrels, and then went dead-bent fur the river with his clothes all a-blazin'? Whar'd we hev been for a couple of weeks ef it hadn't bin fur them bar'ls?"

The remembrance of this gallant act so affected Wolverine, that he exclaimed:

"Whitey, we'll stick to yer like tar-an'-feather, an' ef cap'n an' his friends git troublesome we'll jes' show 'em the trail, an' seggest they're big enough to git up a concern uv their own, instid of tryin' to steal somebody else's."

The chief felt that he was still dear to the hearts of his subjects, and so many took pains that day to renew their allegiance that he grew magnanimous—in fact, when the chief that evening invited the boys to drink, he pushed his own particular bottle to the captain—an attention as delicate as that displayed by a clergyman when he invites into his pulpit the minister of a different creed.

Still the captain labored. So often did the latter stand treat that the barkeeper suddenly ran short of liquor, and was compelled, for a week, to restrict general treats to three per diem until he could lay in a fresh stock.

The captain could hit corks and half-dollars in the air almost every time, but no opportunity occurred in which he could exercise his markmanship for the benefit of the camp.

He also told any number of good stories, at which the boys, Whitey included, laughed heartily; he sang jolly songs, with a very fair tenor voice, and all the boys joined in the chorus; and he played a banjo in style, which always set the boys to capering as gracefully as a crowd of bachelor bears.

But still Whitey remained in camp and in office, and the captain, who was as humane as he was ambitious, had no idea of attempting to remove the old chief by force.

On Monday night the whole camp retired early, and slept soundly. Monday had at all times a very short evening at Black Hat, for the boys were generally weary after the duties and excitements of Sunday; but on this particular Monday a slide had threatened on the hillside, and the boys had been hard at work cutting and carrying huge logs to make a break or barricade.

So, soon after supper they took a drink or two, and sprinkled to their several huts, and Black Hat was at peace, There were no dogs or cats to make night hideous—no uneasy roosters to be sounding alarm at unearthly hours—no horrible policemen thumping the sidewalks with clubs—no fashionable or dissipated people rattling about in carriages. Excepting an occasional cough, or sneeze, or over-loud snore, the most perfect peace reigned at Black Hat.

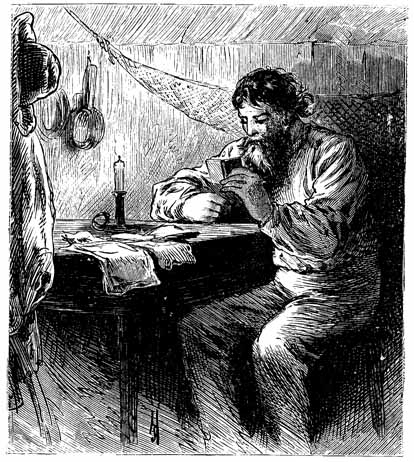

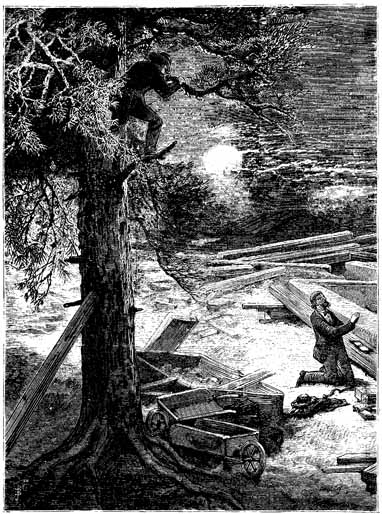

Suddenly a low but heavy rumble, and a trembling of the ground, roused every man in camp, and, rushing out of their huts, the miners saw a mass of stones and earth had been loosened far up the hillside, and were breaking over the barricade in one place, and coming down in a perfect torrent.

They were fortunately moving toward the river on a line obstructed by no houses, though the hut of old Miller, who was very sick, was close to the rocky torrent.

But while they stared, a young pine-tree, perhaps a foot thick, which had been torn loose by the rocks and brought down by them, suddenly tumbled, root first, over a steep rock, a few feet in front of old Miller's door. The leverage exerted by the lower portion of the stem threw the whole tree into a vertical position for an instant; then it caught the wind, tottered, and finally fell directly on the front of old Miller's hut, crushing in the gable and a portion of the front door, and threatening the hut and its unfortunate occupant with immediate destruction.

A deep groan and many terrible oaths burst from the boys, and then, with one impulse, they rushed to the tree and attempted to move it; but it lay at an angle of about forty-five degrees from the horizontal, its roots heavy with dirt, on the ground in front of the door, and its top high in the air.

The boys could only lift the lower portion; but should they do so, then the hut would be entirely crushed by the full weight of the tree.

There was no window through which they could get Miller out, and there was no knowing how long the frail hut could resist the weight of the tree.

Suddenly a well-known voice was heard shouting;

"Keep your head level, Miller, old chap—we'll hev you out of that in no time. Hurry up, somebody, and borrow the barkeeper's ropes. While I'm cuttin', throw a rope over the top, and when she commences to go, haul all together and suddenly, then 'twill clear the hut."

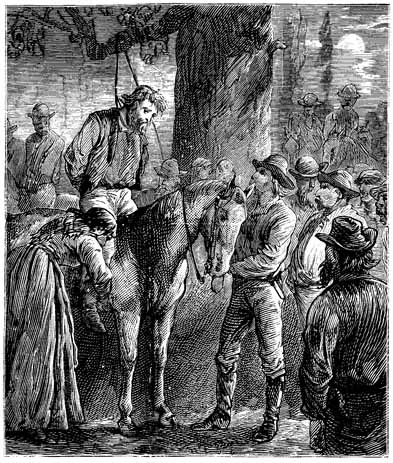

In an instant later the boys saw, by the bright moonlight, the captain, bareheaded, barefooted, with open shirt, standing on the tree directly over the crushed gable, and chopping with frantic rapidity.

"Hooray for cap'en!" shouted some one.

"Hooray!" replied the crowd, and a feeble "hooray"' was heard from between the logs of old Miller's hut.

Two or three men came hurrying back with the ropes, and one of them was dexterously thrown across a branch of the tree. Then the boys distributed themselves along both ends of the rope.

"Easy!" screamed the captain. "Plenty of time. I'll give the word. When I say, 'Now,' pull quick and all together. I won't be long."

And big chips flew in undiminished quantity, while a commendatory murmur ran along both lines of men, and Whitey, the chief, knelt with his lips to one of the chinks of the hut, and assured old Miller that he was perfectly safe.

"Now!" shrieked the captain, suddenly.

In his excitement, he stepped toward the top instead of the root of the tree; in an instant the top of the tree was snatched from the hut, but it tossed the unfortunate captain into the air as easily as a sling tosses a stone.

Every one rushed to the spot where he had fallen. They found him senseless, and carried him to the saloon, where the candles were already lighted. One of the miners, who had been a doctor, promptly examined his bruises, and exclaimed:

"He's two or three broken ribs, that's all. It's a wonder he didn't break every bone in his body. He'll be around all right inside of a month."

"Gentlemen," said Whitey, "I resign. All in favor of the cap'en will please say 'I.'"

"I," replied every one.

"I don't put the noes," continued Whitey, "because I'm a peaceable man, and don't want to hev to kick any man mean enough to vote no. Cap'en, you're boss of this camp, and I'm yourn obediently."

The captain opened his eyes slowly, and replied:

"I'm much obliged, boys, but I won't give Whitey the trouble. Doctor's mistaken—there's someting broken inside, and I haven't got many minutes more to live."

"Do yer best, cap'en," said the barkeeper, encouragingly. "Promise me you'll stay alive, and I'll go straight down to 'Frisco, and get you all the champagne you can drink."

"You're very kind," replied the captain, faintly; "but I'm sent for, and I've got to go. I've left the East to make my mark, but I didn't expect to make it in real estate. Whitey, I was a fool for wanting to be chief of Black Hat, and you've forgiven me like a gentleman and a Christian. It's getting dark—I'm thirsty—I'm going—gone!"

The doctor felt the captain's wrist, and said:

"Fact, gentlemen, he's panned his last dirt."

"Do the honors, boys," said the barkeeper, placing glasses along the bar.

Each man filled his glass, and all looked at Whitey.

"Boys," said Whitey, solemnly, "ef the cap'en hed struck a nugget, good luck might hev spiled him; ef he'd been chief of Black Hat, or any other place, he might hev got shot. But he's made his mark, so nobody begrudges him, an' nobody can rub it out. So here's to 'the cap'en's mark, a dead sure thing.' Bottoms up."

The glasses were emptied in silence, and turned bottoms uppermost on the bar.

The boys were slowly dispersing, when one, who was strongly suspected of having been a Church member remarked:

"He was took of a sudden, so he shouldn't be stuck up."

Whitey turned to him, and replied, with some asperity:

"Young man, you'll be lucky ef you're ever stuck up as high as the captain."

And all the boys understood what Whitey meant.

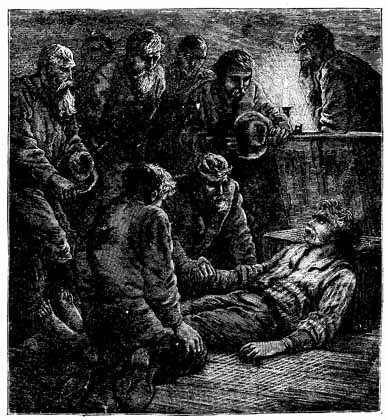

Two o'clock A.M. is supposed to be a popular sleeping hour the world over, and as Flatfoot Bar was a portion of the terrestrial sphere, it was but natural to expect its denizens to be in bed at that hour.

Yet, on a certain morning twenty years ago, when there was neither sickness nor a fashionable entertainment to excuse irregular hours in camp, a bright light streamed from the only window of Chagres Charley's residence at Flatfoot Bar, and inside of the walls of Chagres Charley's domicile were half a dozen miners engaged in earnest conversation.

Flatfoot Bar had never formally elected a town committee, for the half-dozen men aforesaid had long ago modestly assumed the duties and responsibilities of city fathers, and so judicious had been their conduct, that no one had ever expressed a desire for a change in the government.

The six men, in half a dozen different positions, surrounded Chagres Charley's fire, and gazed into it as intently as if they were fire-worshipers awaiting the utterances of a salamanderish oracle.

But the doughty Puritans of Cromwell's time, while they trusted in God, carefully protected their powder from moisture, and the devout Mohammedan, to this day, ties up his camel at night before committing it to the keeping of the higher powers; so it was but natural that the anxious ones at Flatfoot Bar vigorously ventilated their own ideas while they longed for light and knowledge.

"They ain't ornaments to camp, no way you can fix it, them Greasers ain't," said a tall miner, bestowing an effective kick upon a stick of firewood, which had departed a short distance from his neighbors.

"Mississip's right, fellers," said the host. "They ain't got the slightest idee of the duties of citizens. They show themselves down to the saloon, to be sure, an' I never seed one of 'em a-waterin.' his liquor; but when you've sed that, you've sed ev'rythin'."

"Our distinguished friend, speaks truthfully," remarked Nappy Boney, the only Frenchman in camp, and possessing a nickname playfully contracted from the name of the first emperor. "La gloire is nothing to them. Comprehends any one that they know not even of France's most illustrious son, le petit caporal?"

"That's bad, to be sure," said Texas, cutting an enormous chew of tobacco, and passing both plug and knife; "but that might be overlooked; mebbe the schools down in Mexico ain't up with the times. What I'm down on is, they hain't got none of the eddication that comes nateral to a gentleman, even, ef he never seed the outside of a schoolhouse. Who ever heerd of one of 'em hevin' a difficulty with any gentleman, at the saloon or on the crick? They drar a good deal of blood, but it's allers from some of their own kind, an' up there by 'emselves. Ef they hed a grain of public spirit, not to say liberality, they'd do some of their amusements before the rest of us, instead of gougin' the camp out of its constitutional amusements. Why, I've knowed the time when I've held in fur six hours on a stretch, till there could be fellers enough around to git a good deal of enjoyment out of it."

"They wash out a sight of dust!" growled Lynn Taps, from the Massachusetts shoe district; "but I never could git one of 'em to put up an ounce on a game—they jest play by 'emselves, an' keep all their washin's to home."

"Blarst 'em hall! let's give 'em tickets-o'-leave, an' show em the trail!" roared Bracelets, a stout Englishman, who had on each wrist a red scar, which had suggested his name and unpleasant situations. "I believe in fair play, but I darsn't keep my eyes hoff of 'em sleepy-lookin' tops, when their flippers is anywheres near their knives, you know."

"Well, what's to be done to 'em?" demanded Lynn Taps. "All this jawin's well enough, but jaw never cleared out anybody 'xcep' that time Samson tried, an' then it came from an individual that wasn't related to any of this crowd."

"Let 'em alone till next time they git into a muss, an' then clean 'em all out of camp," said Chagres Charley. "Let's hev it onderstood that while this camp cheerfully recognizes the right of a gentleman to shoot at sight an' lay out his man, that it considers stabbin' in the dark's the same thing as murder. Them's our principles, and folks might's well know 'em fust as last. Good Lord! what's that?"

All the men started to their feet at the sound of a long, loud yell.

"That's one of 'em now!" ejaculated Mississip, with a huge oath. "Nobody but a Greaser ken holler that way—sounds like the last despairin' cry of a dyin' mule. There's only eight or nine of 'em, an' each of us is good fur two Greasers apiece—let's make 'em git this minnit."

And Mississip dashed out of the door, followed by the other five, revolvers in hand.

The Mexicans lived together, in a hut made of raw hides, one of which constituted the door.

The devoted six reached the hut, Texas snatched aside the hide, and each man presented his pistol at full cock.

But no one fired; on the contrary, each man slowly dropped his pistol, and opened his eyes.

There was no newly made corpse visible, nor did any Greasers savagely wave a bloody stiletto.

But on the ground, insensible, lay a Mexican woman, and about her stood seven or eight Greasers, each looking even more dumb, incapable, and solemn than usual.

The city fathers felt themselves in an awkward position, and Mississip finally asked, in the meekest of tones:

"What's the matter?"

"She Codago's wife," softly replied a Mexican. "They fight in Chihuahua—he run away—she follow. She come here now—this minute—she fall on Codago—she say something, we know not—he scream an' run."

"He's a low-lived scoundrel!" said Chagres Charley, between his teeth. "Ef my wife thort enough of me to follow me to the diggin's, I wouldn't do much runnin' away. He's a reg'lar black-hearted, white-livered—"

"Sh—h—h!" whispered Nappy, the Frenchman. "The lady is recovering, and she may have a heart."

"Maria, Madre purissima!" low wailed the woman. "Mi nino—mi nino perdido!"

"What's she a-sayin'?" asked Lynn Taps, in a whisper.

"She talk about little boy lost," said the Mexican.

"An' her husband gone, too, poor woman!" said Chagres Charley, in the most sympathizing tones ever heard at Flatfoot Bar. "But a doctor'd be more good to her jes' now than forty sich husbands as her'n. Where's the nearest doctor, fellers?" continued Chagres Charley.

"Up to Dutch Hill," said Texas; "an' I'll see he's fetched inside of two hours."

Saying which, Texas dropped the raw-hide door, and hurried off.

The remaining five strolled slowly back to Chagres Charley's hut.

"Them Greasers hain't never got nothin'," said Mississip, suddenly; "an' that woman'll lay thar on the bare ground all night 'fore they think of makin' her comfortable. Who's got an extra blanket?"

"I!" said each of the four others; and Nappy Boney expressed the feeling of the whole party by exclaiming:

"The blue sky is enough good to cover man when woman needs blankets."

Hastily Mississip collected the four extra blankets and both of his own, and, as he sped toward the Mexican hut, he stopped several times by the way to dexterously snatch blankets from sleeping forms.

"Here you be," said he, suddenly entering the Mexican hut, and startling the inmates into crossing themselves violently. "Make the poor thing a decent bed, an' we'll hev a doctor here pretty soon."

Mississip had barely vanished, when a light scratching was heard on the door.

A Mexican opened it, and saw Nappy Boney, with extended hand and bottle.

"It is the eau-de-vie of la belle France," he whispered. "Tenderly I have cherished, but it is at the lady's service."

Chagres Charley, Lynn Taps and Bracelets were composing their nerves with pipes about the fire they had surrounded early in the morning. Lynn Taps had just declared his disbelief of a soul inside of the Mexican frame, when the door was thrown open and an excited Mexican appeared.

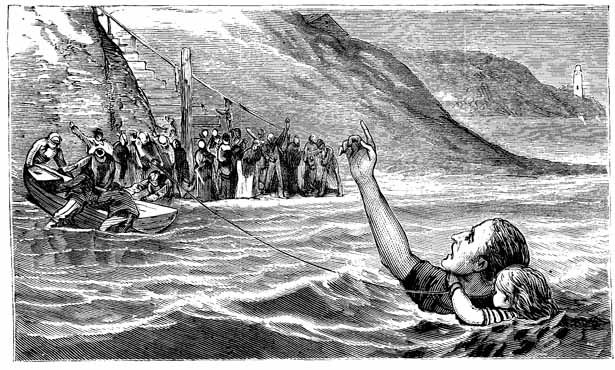

"Her tongue come back!" he cried. "She say she come over mountain—she bring little boy—she no eat, it was long time. Soon she must die, boy must die. What she do? She put round boy her cloak, an' leave him by rock, an' hurry to tell. Maybe coyote get him. What can do?"