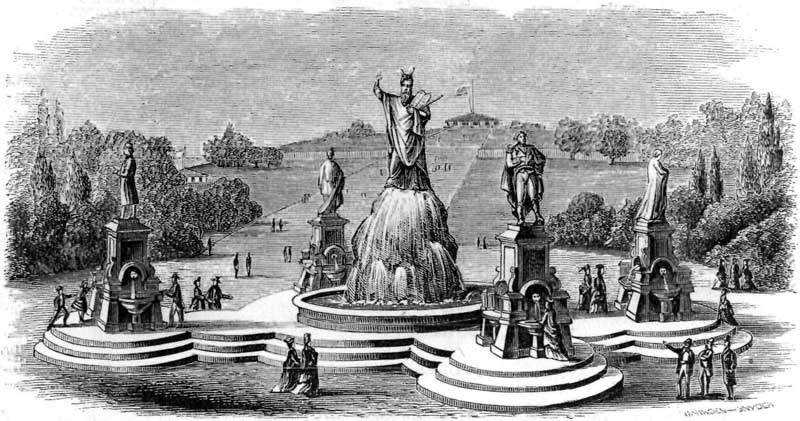

FOUNTAIN OF THE CATHOLIC TOTAL ABSTINENCE UNION.

FOUNTAIN OF THE CATHOLIC TOTAL ABSTINENCE UNION.

Title: Lippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Volume 17, No. 101, May, 1876

Author: Various

Release date: November 4, 2004 [eBook #13956]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Sandra Brown and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team.

THE CENTURY--ITS FRUITS AND ITS FESTIVAL.

V.--MINOR STRUCTURES OF THE EXHIBITION. [Illustrated] 521

GLIMPSES OF CONSTANTINOPLE by SHEILA HALE.

TWO PAPERS.--I. [Illustrated]539

THE BALLAD OF THE BELL-TOWER by MARGARET J. PRESTON. 551

BERLIN AND VIENNA by JAMES MORGAN HART. 553

THE ATONEMENT OF LEAM DUNDAS

By MRS. E. LYNN LINTON, AUTHOR OF "PATRICIA KEMBALL.

CHAPTER XXXIII. OUR MARRIAGE.563

CHAPTER XXXIV. IS THIS LOVE? 567

CHAPTER XXXV. DUNASTON CASTLE.574

CHAPTER XXXVI. IN LETTERS OF FIRE.581

ROSE-MORALS by SIDNEY LANIER.587

AN OLD HOUSE AND ITS STORY by K. T. T. 588

THE WATCH: AN OLD MAN'S STORY by IVAN TOURGUENEFF.594

TRANSLATIONS FROM HEINE by EMMA LAZARUS. 617

I.--CHILDE HAROLD.

II.--SPRING FESTIVAL.

LETTERS FROM SOUTH AFRICA by LADY BARKER. 618

THE LIFE OF GEORGE TICKNOR by T. S. PERRY. 630

OUR MONTHLY GOSSIP.

A REMINISCENCE OF MACAULAY by E. Y. 636

UNVEILING KEATS'S MEDALLION by T. A. T. 638

GINO CAPPONI by T. A. T. 640

A DINNER WITH ROSSI by L. H. H. 641

"FOUNDER'S DAY" AT RAINE'S HOSPITAL by B. M. 644

NOTES. 646

LITERATURE OF THE DAY. 647

Books Received. 649

FOUNTAIN OF THE CATHOLIC TOTAL ABSTINENCE UNION.

UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT BUILDING.

THE SULTAN'S NEW PALACE ON THE BOSPHORUS.

MARBLE STAIRCASE, PALACE OF BESKIK-TASCH.

INTERIOR OF THE MOSQUE OF ST. SOPHIA.

Compress it as you may, this globe of ours remains quite a bulky affair. The world in little is not reducible to a microscopic point. The nations collected to show their riches, crude and wrought, bring with them also their wants. For the display, for its comfort and good order, not only space, but a carefully-planned organization and a multiplicity of appliances are needed. Separate or assembled, men demand a home, a government, workshops, show-rooms and restaurants. For even so paternal and, within its especial domain, autocratic a sway as that of the Centennial Commission to provide all these directly would be impossible. A great deal is, as in the outer world, necessarily left to private effort, combined or individual.

Having in our last paper sketched the provision made by the management for sheltering and properly presenting to the eye the objects on exhibition, we shall now turn from the strictly public buildings [pg 522] to the more numerous ones which surround them, and descend, so to speak, from the Capitol to the capital.

Our circuit brought us back to the neighborhood of the principal entrance. Standing here, facing the interval between the Main Building and Machinery Hall, our eyes and steps are conducted from great to greater by a group of buildings which must bear their true name of offices, belittling as a title suggestive of clerks and counting-rooms is to dimensions and capacity exceeding those of most churches. Right and left a brace of these modest but sightly and habitable-looking foot-hills to the Alps of glass accommodate the executive and staff departments of the exposition. They bring together, besides the central administration, the post, police, custom-house, telegraph, etc. A front, including the connecting verandah, of five hundred feet indicates the scale on which this transitory government is organized. Farther back, directly opposite the entrance, but beyond the north line of the great halls, stands the Judges' Pavilion. In this capacious "box," a hundred and fifty-two by a hundred and fifteen feet, the grand and petit juries of the tribunal of industry and taste have abundant elbow—room for deliberation and discussion. The same enlightened policy which aimed at securing the utmost independence and the highest qualifications of knowledge and intelligence in the two hundred men who determine the awards, recognized also the advantage of providing for their convenience. Their sessions here can be neither cramped nor disturbed. So far as foresight can go, there is nothing to prevent their deciding quietly, comfortably and soundly, after mute argument from the vast array of objects submitted to their verdict, on the merits of each. The main hall of this building, or high court as it may be termed, is sixty by eighty feet, and forty-three feet high. In the rear of it is a smaller hall. A number of other chambers and committee-rooms are appropriated to the different branches as classified. Accommodation is afforded, besides, to purposes of a less arid nature—fêtes, receptions, conventions, international congresses and the like. This cosmopolitan forum might fitly have been modeled after

the tower that builders vain,

Presumptuous, piled on Shinar's plain.

Bricks from Birs Nimroud would have been a good material for the walks. Perhaps, order being the great end, anything savoring of confusion was thought out of place.

Fire is an invader of peace and property, [pg 523] defence against whose destructive forays is one of the first and most constant cares of American cities, old and new, great and small. Before the foundations of the Main Building were laid the means of meeting the foe on the threshold were planned. The Main Building alone contains seventy-five fire-plugs, with pressure sufficient to throw water over its highest point. Adjacent to it on the outside are thirty-three more. Seventy-six others protect Machinery Hall, within which are the head-quarters of the fire service. A large outfit of steam fire-engines, hose, trucks, ladders, extinguishers and other appliances of the kind make up a force powerful enough, one would think, to put out that shining light in the records of conflagration—Constantinople. Steam is kept up night and day in the engines, which, with their appurtenances, are manned by about two hundred picked men. The houses for their shelter, erected at a cost of eight thousand dollars, complete, if we except some architectural afterthoughts in the shape of annexes, the list of the buildings erected by the commission.

Place aux dames! First among the independent structures we must note the Women's Pavilion. After having well earned, by raising a large contribution to the Centennial stock, the privilege of expending thirty-five thousand dollars of their own on a separate receptacle of products of the female head and hand, the ladies selected for that a sufficiently modest site and design. To the trait of modesty we cannot say that the building has failed to add that of grace. In this respect, however, it does not strike us as coming up to the standard attained by some of its neighbors. The low-arched roofs give it somewhat the appearance of a union railway-depot; and one is apt to look for the emergence from the main entrances rather of locomotives than of ladies. The interior, however is more light and airy in effect than the exterior. But "pretty is that pretty does" was a favorite maxim of the Revolutionary dames; and the remarkable energy shown by their fair descendants, under the presidency of Mrs. E. D. Gillespie, in carrying through this undertaking will impart to it new force. The rule is quite in harmony with it that mere frippery should be avoided within and without, and the purely decorative architect excluded with Miss McFlimsey. The ground-plan is very simple, blending the cross and the square. Nave and transept [pg 524] are identical in dimensions, each being sixty-four by one hundred and ninety-two feet. The four angles formed by their intersection are nearly filled out by as many sheds forty-eight feet square. A cupola springs from the centre to a height of ninety feet. An area of thirty thousand square feet strikes us as a modest allowance for the adequate display of female industry. For the filling of the vast cubic space between floor and roof the managers are fain to invoke the aid of an orchestra of the sterner sex to keep it in a state of chronic saturation with music.

Reciprocity, however, obtains here. The votaries of harmony naturally seek the patronage of woman. Her territorial empire has accordingly far overstepped the narrow bounds we have been viewing. The Women's Centennial Music Hall on Broad street is designed for all the musical performances connected with the exposition save those forming part of the opening ceremonies. This is assuming for it a large office, and we should have expected so bold a calculation to be backed by floor-room for more than the forty-five hundred hearers the hall is able to seat. A garden into which it opens will accommodate an additional number, and may suggest souvenirs of al-fresco concerts to European travelers.

Nor does the sex extend traces of its sway in this direction alone. A garden of quite another kind, meant for blossoms other than those of melody, and still more dependent upon woman's nurture, finds a place in the exposition grounds near the Pavilion. Of the divers species of Garten—Blumen-, Thier-, Bier-, etc.—rife in Vaterland, the Kinder- is the latest selected for acclimation in America. If the mothers of our land take kindly to it, it will probably become something of an institution among us. But that is an If of portentous size. The mothers aforesaid will have first to fully comprehend the new system. It is not safe to say with any confidence at first sight that we rightly understand any conception of a German philosopher; but, so far as we can make it out, the Kindergarten appears to be based on the idea of formulating the child's physical as thoroughly as his intellectual training, and at the same time closely consulting his idiosyncrasy in the application of both. His natural disposition and endowments are to be sedulously watched, and guided or wholly repressed as the case may demand. The budding artist is supplied with pencil, the nascent musician with trumpet or tuning-fork, the florist with tiny hoe and trowel, and so on. The boy is never loosed, physically or metaphysically, quite out of leading-strings. They are made, however, so elastic as scarce to be felt, and yet so strong as never to break. Moral suasion, perseveringly applied, predominates over Solomon's system. It is a very nice theory, [pg 525] and we may all study here, at the point of the lecture-rod wielded by fair fingers, its merits as a specific for giving tone to the constitution of Young America.

At the side of the Kindergarten springs a more indigenous growth—the Women's School-house. In this reminder of early days we may freshen our jaded memories, and wonder if, escaped from the dame's school, we have been really manumitted from the instructing hand of women, or ever shall be in the world, or ought to be.

Is the "New England Log-house," devoted to the contrasting of the cuisine of this and the Revolutionary period, strictly to be assigned to the women's ward of the great extempore city? Is its proximity to the buildings just noticed purely accidental, or meant to imply that cookery is as much a female art and mystery as it was a century ago? However this may be, the erection of this temple to the viands of other days was a capital idea, and a blessed one should it aid in the banishment of certain popular delicacies which afflict the digestive apparatus of to-day. This kitchen of the forest epoch is naturally of logs, and logs in their natural condition, with the bark on. The planking of that period is represented by clap-boards or slabs. Garnished with ropes of onions, dried apples, linsey-woolsey garments and similar drapery, the aspect of the walls will remind us of Lowell's lines:

Crook-necks above the chimly hung,

While in among 'em rusted

The old Queen's-arm that Gran'ther Young

Brought hack from Concord busted.

The log-house is not by any means an abandoned feature of antiquity. It is still a thriving American "institution" North, West and South, only not so conspicuous in the forefront of our civilization as it once was. It turns out yet fair women and brave men, and more than that—if it be not treason to use terms so unrepublican—the highest product of this world, gentlemen and gentlewomen.

Uncle Sam confronts the ladies from over the way, a ferocious battery of fifty-seven-ton Rodman guns and other monsters of the same family frowning defiance to their smiles and wiles. His traditional dread of masked batteries may have something to do with this demonstration. He need not fear, however. His fair neighbors and nieces have their hands full with their own concerns, and leave him undisturbed in his stately bachelor's hall to "illustrate the functions and administrative faculties of the government in time of peace and its resources as a war-power." To do this properly, he has found two acres of ground none too much. The building, business-like and capable-looking, was erected in a style and with a degree of economy creditable to the officers of the board, selected from the Departments of War, Agriculture, the Treasury, Navy, Interior and Post-Office, and from the Smithsonian Institution. Appended to it are smaller structures for the illustration of hospital and laboratory work—a kill-and-cure association that is but one of the odd contradictions of war.

The sentiments prevalent in this era of perfect peace, harmony and balance of rights forbids the suspicion of any significance in the fact that the lordly palace of the Federal government at once overshadows and turns its back upon the humbler tenements of the States. A line of these, drawn up in close order, shoulder to shoulder, is ranged, hard by, against the tall fence that encloses the grounds. The Keystone State, as beseems her, heads the line by the left flank. Then come, in due order, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Massachusetts and Delaware. New Jersey and Kansas stand proudly apart, officer-like, on the opposite side of the avenue; the regimental canteen, in the shape of the Southern Restaurant, jostling them rather too closely. Somewhat in keeping with the over-prominence of the latter adjunct is the militia-like aspect of the array, wonderfully irregular as are its members in stature and style. Pennsylvania's pavilion, costing forty thousand dollars, or half as much as the United States building, plays the leading grenadier well; but little Delaware, not content with the obscure post of file-closer, swells at the opposite end of the line into dimensions of ninety by seventy-five feet, with a cupola that, if placed at Dover, would be visible from half her territory.

These buildings are all of wood, with the exception of that of Ohio, which exhibits some of the fine varieties of stone furnished by the quarries of that State, together with some crumbling red sandstone which ought, in our opinion, to have been left at home. All have two floors, save the Massachusetts cottage, a quaint affair modeled after the homes of the past. Virginia ought to have placed by its side one of her own old country-houses, long and low, with attic windows, the roof spreading with unbroken line over a portico the full length of the front, and a broad-bottomed chimney on the outside of each gable. The State of New York plays orderly sergeant, and stands in front of Delaware. She is very fortunate in the site assigned her, at the junction of State Avenue with several broad promenades, and her building is not unworthy so prominent a position.

From the Empire State we step into the domain of Old England. Three of her rural homesteads rise before us, red-tiled, many-gabled, lattice-windowed, and telling of a kindly winter with external chimneys that care not for the hoarding of heat. It is a bit of the island peopled by some of the islanders. They are colonized here, from commissioner in charge down to private, in a cheek-by-jowl fashion that shows their ability to unbend and republicanize on occasion. Great Britain's head-quarters [pg 527] are made particularly attractive, not more by the picturesqueness of the buildings than by the extent and completeness of her exhibit. In her preparations for neither the French nor the Austrian exposition did she manifest a stronger determination to be thoroughly well represented. Col. H.B. Sanford, of the Royal Artillery, heads her commission.

Japan is a common and close neighbor to the two competitors for her commercial good-will, England and New York. Modern Anglo-Saxondom and old Cathay touch eaves with each other. Hemlock and British oak rub against bamboo, and dwellings which at first sight may impress one as chiefly chimney stand in sharp contrast with one wholly devoid of that feature. The difference is that of nails and bolts against dovetails and wooden pins; of light and pervious walls with heavy sun-repelling roof against close and dense sides and roofs whose chief warfare is with the clouds; of saw and plane that work in Mongol and Caucasian hands in directions precisely reversed. To the carpenters of both England and Japan our winter climate, albeit far milder than usual, was alike astonishing. With equal readiness, though not with equal violence to the outer man, the craftsmen of the two nations accommodated themselves to the new atmospheric conditions. The moulting process, in point of dress, through which the Japanese passed was not untypical of the change the institutions of their country have been undergoing in obedience to similarly stern requirements. It did not begin at quite so rudimental a stage of costume as that of the porters and wrestlers presented to us on fans, admirably adapted as that style might be to our summer temperature. In preparing for that oscillation of the thermometer the English are called on for another change, whereas the Orientals may meet it by simply reverting to first principles.

The delicacy of the Asiatic touch is exemplified in the wood-carving upon the doorways and pediments of the Japanese dwelling. Arabesques and reproductions of subjects from Nature are executed with a clearness and precision such as we are accustomed to admire on the lacquered-ware cabinets and bronzes of Japan. With us, wood has almost completely disappeared as a glyptic material. The introduction of mindless automatic machinery has starved out the chisel. Mouldings are run out for us by the mile, like iron from the rolling-mill or tunes from a musical-box, as cheap and as soulless. Forms innately beautiful thus become almost hateful, because hackneyed. If all the women we see were at once faultlessly beautiful and absolute duplicates of each other in the minutest details of feature, complexion, dress and figure, we should be in danger of conceiving an aversion to the sex. So there is a certain pleasure in tracing in a carven object, even though it be hideous, the patient, faithful, watchful work of the human hand guided at every instant by the human eye. And this [pg 528] Japanese tracery is by no means hideous. The plants and animals are well studied from reality, and truer than the average of popular designs in Europe a century ago, if not now. It is simple justice to add that for workmanlike thoroughness this structure does not suffer in comparison with those around it.

Besides this dwelling for its employés, the Japanese government has in a more central situation, close to the Judges' Pavilion, another building. The style of this is equally characteristic. Together, the two structures will do what houses may toward making us acquainted with the public and private ménage of Japan.

In the neat little Swedish School-house, of unpainted wood, that stands next to the main Japanese building, we have another meeting of antipodes. Northern Europe is proud to place close under the eye of Eastern Asia a specimen of what she is doing for education. Sweden has indeed distinguished herself by the interest she has shown in the exposition. At the head of her commission was placed Mr. Dannfeldt, who supervised her display at Vienna. His activity and judgment have obviously not suffered from the lapse of three years. This school-house is attractive for neatness and peculiarity of construction. It was erected by Swedish carpenters. The descendants of the hardy sea-rovers, convinced that their inherited vigor and thrift could not be adequately illustrated by an exclusively in-doors exhibition, sent their portable contributions in a fine steamer of Swedish build, the largest ever sent to sea from the Venice of the North, and not unworthy her namesake of the Adriatic. To compete in two of its specialties with the cradle of the common school and the steamship is a step that tells of the bold Scandinavian spirit.

The contemporaries and ancient foes of the Northmen, who overthrew the Goths on land and checkmated the Vikings in the southern seas, have a memorial in the beautiful Alhambra-like edifice of the Spanish government. Spain has no architecture so distinctive as that of the Moors, and the selection of their style for the present purpose was in good taste. It lends itself well to this class of building, designed especially for summer use; and many other examples of it will be found upon the grounds. The Mohammedan arch is suited better to materials, like wood and iron, which sustain themselves in part by cohesion, than to stone, which depends upon gravitation alone. Although it stands in stone in a long cordon of colonnades from the Ganges to the Guadalquivir, the eye never quite reconciles itself to the suggestion of untruth and feebleness in the recurved base of the arch. This defect, [pg 529] however, is obtrusive only when the weight supported is great; and the Moorish builders have generally avoided subjecting it to that test.

Spain also has taken the liberty of widening the range of her contributions. Soldiers, for instance, find no place in the official classification of subjects for exhibition. She naturally thought it worth while to show that the famous infanteria of Alva, Gonsalvo, and Cuesta "still lived." So she sends us specimens of the first, if not just now the foremost, of all infantry. This microscopic invasion of our soil by an armed force will be useful in reminding us of the untiring tenacity which takes no note of time or of defeat, and which, indifferent whether the struggle were of six, fifty, or seven hundred years, wore down in succession the Saracens, the Flemings and the French.

Samples in this particular walk of competition come likewise from the battle-ground of Europe, Belgium sending a detachment of her troops for police duty. We may add that the Centennial has brought back the red-coats, a detachment of Royal Engineers, backed by part of Inspector Bucket's men, doing duty in the British division.

After these first drops of the military shower one looks instinctively for the gleam of the spiked helmet at the portals of the German building, seated not far from that of Spain, and side by side with that of Brazil. It does not appear, however. Possibly, Prince Bismarck scorns to send his veterans anywhere by permission. Neither does he indulge us, like Brazil, with the sight of an emperor, or even with cæsarism in the dilute form of a crown prince. Such exotics do not transplant well, even for temporary potting, in this republican soil. It is impossible, at the same time, not to reflect what a capital card for the treasury of the exposition would have been the catching of some of them in full bloom, as at the openings of 1867 and 1873. A week of Wilhelm would have caused "the soft German accent," with its tender "hochs!" to drown all other sounds between Sandy Hook and the Golden Gate.

Let us step over the Rhine, or rather, alas! over the Moselle, and look up at the tricolor. It floats above a group of structures—one for the general use of the French commission, another for the special display of bronzes, and a third for another art-manufacture for which France is becoming eminent—stained glass. This overflowing from her great and closely-occupied area in Memorial Hall, hard by, indicates the wealth of France in art. She is largely represented, moreover, in another outlying province of the same domain—photography.

Photographic Hall, an offshoot from Memorial Hall, and lying between it and the Main Building, is quite a solid structure, two hundred and fifty-eight feet by one hundred and seven, with nineteen thousand feet of wall-space. Conceding this liberally to foreign exhibitors, an association of American photographers erected a hall of their own in another direction, upon Belmont Avenue beyond the Judges' Pavilion. This will serve to exhibit the art in operation under an American sun, and enable our photographers to compare notes and processes with their European fellows, who treat under different atmospheric conditions a wider range of subjects. This is the largest studio the sun, in his capacity of artist on paper, has ever set up, as the hall provided for him by the exposition is the largest gallery he has ever filled. Combined, they may reasonably be expected to bear some fruit in the way of drawing from him the secret he still withholds—the addition of color to light and shade in the fixed images of the camera. This further step seems, when we view within the camera the image in perfect panoply of all its hues, so very slight in comparison with the original discovery of Daguerre, that we can hardly refer it to a distant future.

Questions of finance naturally associate themselves with sitting for one's portrait, even to the sun. A national bank becomes a necessity to their readier solution, be they suggested by this or any other item of expense. Such an institution has consequently a place in the outfit of the Centennial. Here it stands within its own walls, under its own roof and behind its own counter. The traditional cashier is at home in his parlor, the traditional teller observes mankind from his rampart of wire and glass, and the traditional clerk busy in the rear studies over his shoulder the strange accent and the strange face. Over and above the conveniences for exchange afforded by the bank, it will introduce to foreigners the charms of one of our newest inventions—the greenback. This humble but heterodox device, not pleasant in the eyes of the old school of conservative financiers, is yet unique and valuable as having accomplished the task of absolutely equalizing the popular currency of so large a country as the Union. That gap of twelve or thirteen per cent. between greenbacks and gold is no doubt an hiatus valde deflendus—a gulf which has swallowed up many an ardent and confident Curtius, and will swallow more before it disappears; but the difference is uniform everywhere, and discounts itself. Whatever the faults of our paper-money, it claims a prominent place among the illustrations of the close of the century, for it is the only currency save copper and Mr. Memminger's designs in blue that a majority of American youth have ever seen. Should these young inquirers wish to unearth the money of their fathers, they can find the eagles among other medals of antiquity in the Mint department of the United States Government Building.

His fiscal affairs brought into comfortable shape, the tourist from abroad may be desirous of seeing more of the United States than is included in the view from the great Observatory. The landscape visible from that point, as he will find after being wound to the top by steam, is not flecked with buffaloes or even the smoke of the infrequent wigwam, as the incautious reader of some Transatlantic books of travel might expect. For the due exploration of at least a portion of the broad territory that lies inside of the buffalo range he needs a railway-ticket and information. These are at his command in the "World's Ticket and Inquiry Office," the abundantly comprehensive name of a building near the north-east corner of Machinery Hall. In a central area sixty feet in diameter tickets to every known point are offered to him by polyglot clerks. Here, too, a wholesome interchange of ideas in regard to the merits of the various traveling regulations of different countries may be expected. Baggage-checks or none, compartment or saloon cars, ventilation or swelter in summer, freezing or hot-water-pipes in winter, and other like differences of practice will come under consideration with travelers in general council assembled. Give and take will prevail between our voyagers and railway officials and those of the Old World. Both sides may teach and learn. Should the carriage of goods instead of persons be in question, the American side of the materials for its discussion will be found in the building of the Empire Transportation Company, where the economies of system and "plant," which have for a series of years been steadily reducing the expenses of railway-traffic until the cost of carrying a ton one mile now falls within one cent, will be fully detailed. A further reduction of this charge may result from the exposition if exhibitors from Europe succeed in explaining to our engineers and machinists how they manage to lighten their cars, and thereby avoid carrying the excess of dead weight which contributes so much to the annihilation of our tracks and dividends.

The telegraph completes the mastery over space in the conveyance of thought that the railway attains in that of persons and property. Its facilities here are commensurable with its duty of placing thousands of all countries in instantaneous communication with their homes. Those from over-sea will find that, instead of dragging "at each remove a lengthening chain," they are, on the exposition grounds, in point of intercourse nearer home than they were when half a day out from the port of embarkation, and ten days nearer than when they approached our shores after a sail of three thousand miles. To get out of call from the wire it is necessary to go to sea—and stay there. Another hundred years, and even the seafarer will fail of seclusion. Floating telegraph-offices will buoy the cable. Latitude 40° will "call" the [pg 533] Equator, and warn Grand Banks that "Sargasso is passing by." Not only will the march of Morse be under the mountain-wave, but his home will be on the deep.

The submarine and terrestrial progress of the telegraph was in '67 and '73 already an old story. At the Centennial it presents itself in a new role—that of interpreter of the weather and general storm-detector. This application of its powers is due to American science. Indeed, the requisites for experiments were not elsewhere at command. A vast expanse of unbroken territory comprising many climates and belts of latitude and longitude, and penetrated throughout by the wire under one and the same control, did not offer itself to European investigators. These singular advantages have been well employed by the United States Signal Service within the past five years. Its efforts were materially aided by the antecedent researches of such men as Espy and Maury, the latter of whom led European savants into the recognition of correct theories of both air- and ocean-currents. Daily observations at a hundred stations scattered over the continent, exactly synchronized by telegraph, yielded deductions that steadily grew more and more consistent and reliable, until at length those particularly fickle instruments, the weather-vane, the thermometer, the barometer and the magnetic fluid, have formed, in combination, almost an "arm of precision." The predictions put forth in the "small hours" each morning by the central office in Washington assume only the modest title of "Probabilities." Some additional expenditure, with a doubling of the number of stations, would within a few years make that heading more of a misnomer. Meanwhile, the saving of life and property on sea and land already effected is a solid certainty and no mere "probability." At the station on the exposition grounds the weather of each day, storm or shine, in most of the cities of the Old and New Worlds will be bulletined. "Storm in Vlaenderlandt" will be as surely announced to the Dutch stroller on Belmont Avenue as though he were within hearing of his cathedral bell. Should such a "cautionary signal" from beyond the ocean reach him, he may ascertain in what, if any, danger of submergence his home stands, by stepping into one of the branch telegraph-offices dispersed over the grounds. Or he may satisfy all possible craving for news from that or any other quarter in the Press Building. This metropolis of the fourth estate occupies a romantic site on the south side of the avenue and the north bank of the lake. Such a focus of the news and newspapers of all nations [pg 534] was not paralleled at either of the preceding expositions. American journalism will be additionally represented in the different State buildings, where files of all the publications of each commonwealth will be found, embracing in most cases a greater number of journals than the entire continent boasted in 1776, and in each of the States of Ohio, New York and Pennsylvania more than the extra-metropolitan press of either France, Austria, Prussia or Russia can now boast.

The commercial idea is so prominent in this, as in all expositions, that it is difficult to draw the line between public and private interest among its different features, and particularly among what may be called its outgrowths, overflowings or addenda. Here is half a square mile dotted with a picturesque assemblage of shops and factories, among which everything may be found, from a soda-fountain or a cigar-stand up to a monster brewery, all devoted at once to the exemplification and the rendering immediately profitable of some particular industry. In one ravine an ornate dairy, trim and Arcadian in its appurtenances and ministers as that of Marie Antoinette and her attendant Phillises at the Petit Trianon, offers a beverage presumably about as genuine as that of '76, and much above the standard of to-day. A Virginia tobacco-factory checkmates that innocent tipple with "negrohead" and "navy twist." A bakery strikes the happy medium between the liquid sustenance and the narcotic luxury by teaching Cisatlantic victims of baking-powders and salæratus how to make Vienna bread. Recurring to fluids, we find unconquered soda popping up, or down, from innumerable fonts—how many, may be inferred from the fact that a royalty of two dollars on each spigot is estimated to place thirty-two thousand dollars in the strong box of the exposition. Nor does this measure the whole tribute expected to be offered at these dainty shrines of marble and silver. The two firms that bought the monopoly of them pay in addition the round sum of twenty thousand dollars. It speaks well for the condition of the temperance cause that beer is the nearest rival of aerated water. An octroi of three dollars per barrel is estimated to yield fifty thousand dollars, or two thousand dollars less than soda-water. Seventy-five thousand dollars is the aggregate fee of the restaurants. Of these last-named establishments, the French have two. The historic sign of the Trois Frères Provençaux is assumed by a vast edifice in one of the most conspicuous parts of the enclosure, sandwiched between the Press and the Government. The "Sudreau" affects the fine arts and cultivates with like intimacy the society of Memorial Hall. [pg 535] The German refectory, Lauber's, a solid, beery sort of building, shows a fine bucolic sense by choosing a hermitage in the grove between Agricultural and Horticultural Halls. A number of others, of greater or less pretensions, will enable the visitor to exclaim, with more or less truth, toward the dusty evening, "Fate cannot harm me: I have dined to-day."

"Dusty," did we say? The ceaseless sob of engines that rob the Schuylkill daily of six millions of gallons to sprinkle over asphaltum, gravel and greensward demands recantation of the word. Everything has been foreseen and considered, even the dust of the earth. George's Hill Reservoir can, on occasion, give the pumps several days' holiday, and keep all fresh and dewy as the dawn.

Some industries meet us in the Centennial list that are not to be detected in the United States census or any other return we are acquainted with. What train of ideas, for example, is suggested to the average reader by the Roll-Chair Company? The rolling-stock of this association turns out, on inquiry, to be an in-door variety of the conveyance wherein Mrs. Skewton was wont to take the air under the escort of Major Bagstock. It is meant for the relief of those who wish to see everything in the Main Building without trudging eleven miles. Given an effective and economical motive-power, the roll-chair system would seem to meet this want. The reader of Dombey and Son will recollect the pictorial effect, in print and etching, of the popping up of the head of the propellent force when Mrs. S. called a halt, and its sudden disappearance on her directing a resumption of movement. The bobbing up and down of four hundred and fifty heads, like so many seals, will impart a unique aspect to the vista from one of the interior galleries of the great hall. The stipulated tax of forty dollars on each of these vehicles will necessitate a tolerably active undulation of polls if the company is to make both ends meet—granting that a rotatory movement can have an end.

Another startling item is the pop-corn privilege. A business-man of Dayton, Ohio, finds himself justified in venturing the heavy sum of seven thousand dollars on this very light article. Parched corn was well known in Ohio in 1776. The Miamis and Shawnees had, however, a monopoly of it. It composed their commissariat for a campaign against the whites. Such is the progress of the century.

This explosive cereal does not satiate the proverbially sweet tooth of our people. Their craving for confectionery is laid under further contribution by the financial managers of the exposition to the tune, for instance, of five thousand dollars for the privilege of manufacturing chocolate and candy. Dyspepsia insists on asserting its position among the other acquisitions of the century. The treasures of the American bonbonnière are said to be richer and more varied than in any other country. Paris gets up her delicacies of this kind in more tasteful and tempting style, but our consumers care little for such superficial vanities. They look for solid qualities in everything—even in their lollipops.

Another description of fuel, employed for the external and not the internal feeding of the animal machine, and quite as evanescent as candy, claims a factory to itself. This is a French invention called the Loiseau Compressed Fuel. To bring it to Philadelphia, the mart of the anthracite region, would seem to be carrying coals to Newcastle. The relation between demand and supply in fuel is happily, for the present, on too sound a basis to leave much room for artificial substitutes. Our anthracite deposits are circumscribed, but bid fair to last until the virtually untouched seams of bituminous and semibituminous coal shall be made amply accessible to every point of consumption. We are not yet in the slightest perceptible danger of the coal-famine that threatens Great Britain.

In regard to the accommodations provided outside of the exhibition buildings by individual enterprise for the display of various products and processes of manufacture, it will here suffice to say [pg 536] that they notably exceed the corresponding array at any of the European expositions. Illustrations of the social and industrial life of different races and nations are, on the other hand, inferior to what was seen at Vienna and Paris. Mankind and their manners are more homogeneous within an available circle around Philadelphia than around either of those capitals. The rude populations of the lower Danube, the Don, the Caucasus, the Steppes, Albania, Syria, Barbary, etc. cannot be so fully represented here. That they should be, were it practicable, would be more to their advantage than to ours perhaps, the probability being slight that we should deem it desirable to adopt many of their methods. Nor will the eating and drinking of the nations be so variously illustrated as in the cordon of restaurants that so largely contributed to the spectacular effect at Paris. The French genius for the dramatic was quite at home in arranging that part of the display; and they did not allow the full effect to suffer for want of some artificial eking out. The kibaubs, pilau and sherbet that were served up in fine Oriental style were not in all cases prepared by Turks, Persians and Tunisians. The materials were abundant in Paris for these and any other outlandish dainties that might be called for. So were costumers. There was no reason, therefore, why imitations should not be got up capable of serving every purpose, and of giving more amusement than the genuine dishes and divans of Islam would have done. The negro waiters in the American saloon doubtless outnumbered all the other representatives of the dark or semi-civilized races that appeared in a similar character. They proved a success, their genial bearing and ever-ready smile pleasing the mass of the guests more than did the triste and impassive Moslem. The theatrical can just as well be done here, and quant. suff. of Cossacks and Turks be manufactured to order. Then we have John and Sambo in unadulterated profusion; the former ready at the shortest notice and for very small compensation to indoctrinate all comers in the art of plying the chopsticks, and the latter notoriously in his element in the kitchen and the dining-room, and able to aid the chasse-café with a song—lord alike of the carving-knife, the cocktail and the castanets.

Water, the simplest, most healthful and most indispensable of all refreshments, is provided without stint and without price. Foreigners are struck with the immense consumption of water as a beverage in this country. They do not realize the aridity of our summer climate, which makes it sometimes as much of a luxury here as it is in the desert. A rill of living water, let it issue from a mossy rift in the hillside or the mouth of a bronze lion, comes to us often like the shadow of a great rock in a weary land. We lead fevered lives, too, and this is the natural relief. Fountains are among the first decorations that show themselves in public or private grounds. They give an excuse and a foothold for sculpture, and thus open the way for high art. In the Centennial grounds and in all the buildings upon them, of whatever character, the fountain, in more or less pretentious style, plays its part. Led from the bosom of a thousand hills, drawn from under the foot of the fawn and the breast of the summer-duck, it springs up into the midst of this hurly-burly of human toil and pleasure, the one unartificial thing there, pure and pellucid as when hidden in its mother rock.

It is not remarkable, then, that the most ambitious effort of monumental art upon the exposition grounds should have taken the shape of a fountain. The erection is due to the energy and public spirit of the Catholic Total Abstinence Union. The site chosen is at the extreme western end of Machinery Hall. It looks along Fountain Avenue to the Horticultural Building. Mated thus with that fine building, it becomes a permanent feature of the Park. The central figure is Moses—not the horned athlete we are apt to think of when we associate the great lawgiver with marble, but staid and stately in full drapery. He strikes the rock of Meribah, and water exudes from its crevices into a marble basin. [pg 537] Outside the circular rim of this are equidistantly arranged the rather incongruous effigies of Archbishop Carroll, his relative the Signer, Commodore Barry and Father Mathew. Each of these worthies presides over a small font designed for drinking purposes—unless that of the old sea-dog be salt. The central basin is additionally embellished with seven medallion heads of Catholics prominent in the Revolution, the selections being La Fayette, his wife, De Grasse, Pulaski, Colonel S. Moylan, Thomas Fitzsimmons and Kosciusko. The artist is Hermann Kirn, a pupil of Steinhäuser, one of the first of the modern romantic school of German sculptors. Kirn is understood to have enjoyed his instructor's aid in completing the statues in the Tyrol.

Another religious body ranges itself in the cause of art by the side of one with which it does not habitually co-operate. Dr. Witherspoon, the only clerical Signer, is its contribution in bronze. The Geneva gown supplies the grand lines lacking in the secular costume of the period, and indues the patriot with the silken cocoon of the Calvinist. The good old divine had well-cut features, which take kindly to the chisel. The pedestal is of granite.

Of other statues we shall take another occasion to speak. The tinkle of fountains leads us on to Horticultural Hall, where they give life and charm to the flowers. Painted thus in water-colors, the blossoms and leaves of the tropics glow with a freshness quite wonderful in view of the very short time the plants have been in place and the exposure they unavoidably encountered in reaching it. From the interior and exterior galleries of this exquisite structure one can look down, on one side, upon the palms of the Equator and on the other upon the beech and the fir, which interlock their topmost sprays at his feet. Beyond and beneath the silvery beeches railway-trains whisk back and forth, like hares athwart the covert—the tireless locomotive another foil to the strangers from the land of languor and repose.

The manufacture of a torrid climate on so large a scale will strike the visitor as one of the most curious triumphs of ingenuity in the whole exposition. Moisture is an essential only second in importance to heat. The two must be associated to create the normal atmosphere of most of the vegetation of the central zone. Art, in securing that end, reverses the process of Nature. The heat here is supplied from below and moisture from [pg 538] above, thus transposing the sun and the swamp. In summer, indeed, the sun of our locality, reinforced by glass, will as a rule furnish an ample supply of warmth. Very frequently it will be in excess, and allow the imprisoned strangers the luxury of all the fresh air they can crave. Our summer climate is in this way more favorable than that of Kew, which in turn has the advantage in winter. The inferior amount of light throughout the year and the long nights of winter in a high latitude again operate against the English horticulturists, and leave, altogether, a balance in our favor which ought to make the leading American conservatory the most successful in the world.

Standing by the marble fountain in the great hall, with its attendant vases and statuary, the visitor will not suspect that the pavement beneath his feet is underlaid by four miles of iron pipe four inches in diameter and weighing nearly three hundred tons. Through this immense arterial and venous system circulates the life-blood of the plants, hot water being the vehicle of warmth in winter. These invisible streams will flow when the brooks at the foot of the hill are sealed by frost and the plash of the open-air fountains is heard no longer.

Another current, more conspicuous and abounding—that of hurrying human feet—will make this magnificent conservatory the centre of one of its principal eddies. A second will be the Japanese head-quarters, and a third Memorial Hall. The outlandish and the beautiful in Nature and in art take chief hold of our interest. It wanders elsewhere, but reverts to what typifies the novel and the charming. From the Mongols and the palms it will drift to the granite portals that are flanked by the winged Viennese horses and the colossal figures of Minerva in the act of bridling them. Pegasus is not very worthily represented by these bronzes. The horses, however, are the better part of the two groups; the goddesses being too tall in proportion and heavy and ungraceful in build. The finer things which they sentinel, in bronze, marble or canvas, do not belong to the scope of this article. Yet we cannot postpone to the occasion of their notice in detail a tribute to him to whose energy and judgment we owe the filling of the Art Building with works fit to be there. For the accomplishment of this task the principal credit is due to John Sartain of Philadelphia, the Nestor of American engravers. But for Mr. Sartain's efforts, the studios of the best artists of America, especially, would have been much less adequately represented, while the walls would have been in danger of defacement by a flood of inferior productions. To secure the best, and the best only, of what artists and collectors could give, committees were appointed to inspect the offerings of the principal cities and select works of real merit. The difficulties in the way are appreciable only by those familiar with the diversities of feeling and opinion which are apt to make shipwreck of art-exhibitions. They have been overcome, and American artists have united in the practical measures needed to ensure them as fair a position by the side of foreign competitors as their actual merits can sustain.

It could hardly have been a recognition of carriage-making as one of the fine arts that caused the placing of an immense receptacle for such vehicles in so prominent a position near Memorial Hall. This structure stands opposite the western half of the Main Building. Combined with the annex erected for a like purpose by the Bureau of Agriculture, which covers three acres, it would seem to afford room for specimens of every construction ever placed on wheels since Pharaoh's war-chariots limbered up for the Red Sea campaign. These collections have no trifling significance as a sign of progress. They are the product of good roads, one of the surest traces of civilization. A century ago, a really good road was almost an unknown thing. So recently as half so long since one of the light equipages now so familiar to us would have been a simple impossibility. What words of ecstasy Dr. Johnson, who pronounced the height of bliss to be a drive over a turnpike of his day in a cranky post-chaise, would have applied [pg 539] to a "spin" in one of these wagons, no imagination can guess.

Let us not boast ourselves over the sages who had the misfortune of living too soon. It would be falling into the same blunder Macaulay ascribed to Johnson in alleging that the philosopher thought the Athenian populace the inferiors of Black Frank his valet, because they could not read and Frank could. Our heads are apt to be turned by our success in throwing together iron, timber, stone and other dead matter. Let us remember that we are still at school, with no near prospect of graduating. Many of our contemporary nations, to say nothing of those who are to come after us, claim the ability to teach us, as their being here proves. The assumption speaks from the stiff British chimneys, the pert gables of the Swedes and the laboriously wrought porticoes of the Japanese. This is well. It would be a bad thing for its own future and for that of general progress could any one people pronounce itself satisfied with what it had accomplished and ready to set the seal to its labors.

We sailed from Trieste in the Venus, one of the Austrian Lloyds, with a very agreeable captain, who had been all over the world and spoke English perfectly. There were very few passengers—only one lady besides myself, and she was a bride on her way to her new home in Constantinople. She was a very pretty young Austrian, only seventeen, but such an old "Turk of a husband" as she had! Her mother was a Viennese, and her father a wealthy Englishman: what could have induced them to marry their pretty young daughter to such a man? He was a Greek by descent, but had always lived in Constantinople. Short, stout, cross-eyed, with a most sinister expression of countenance, old enough to be her father, the contrast was most striking. His wife seemed very happy, however, and remarked in a complacent tone that her husband was quite European. So he was, except that he wore a red fez cap, which was, to say the least, not "becoming" to his "style of beauty."

We had a smooth passage to Corfu, where we touched for an hour or two. N—— and I went on shore, climbed to the old citadel, and were rewarded with a glorious view of the island and the harbor at our feet. We picked a large bouquet of scarlet geraniums and other [pg 540] flowers which grew wild on the rocks around the old fortress, took a short walk through the town, and returned to our boat loaded with delicious oranges fresh from the trees. Several fine English yachts lay in the harbor. We passed close to one, and saw on the deck three ladies sitting under an awning with their books and work. The youngest was a very handsome girl, in a yacht-dress of dark-blue cloth and a jaunty sailor hat. What a charming way to spend one's winter! After our taste of the English climate in February, I should think all who could would spend their winters elsewhere; and what greater enjoyment than, with bright Italian skies above, to sail over the blue waters of the Mediterranean, running frequently into port when one felt inclined for society and sight-seeing, or when a storm came on! for the "blue Mediterranean" does not always smile in the sunlight, as we found to our sorrow after leaving Corfu.

Our state-room was on the main deck, with a good-sized window admitting plenty of light and air, and the side of the ship was not so high but we could see over and have a fine view of the high rocky coast we were skirting—so much pleasanter than the under-deck state-rooms, where at best you only get a breath of fresh air and a one-eyed glimpse out of the little port-holes in fine weather, and none at all in a storm. Imagine, therefore, my disgust when, on returning from our trip on shore at Corfu, I found twilight pervading our delightful state-room, caused by an awning being stretched from the edge of the deck overhead to the side of the ship, and under this tent, encamped beneath my window, the lesser wives, children and slaves of an old Turk who was returning to Constantinople with his extensive family! His two principal wives were in state-rooms down below, and invisible. Well, if I had lost the view from my state-room of the grand mountainous coast of Greece, I had an opportunity of studying one phase of Oriental manners and costume at my leisure. There were three pale, sallow-looking women of twenty or twenty-five years of age, with fine black eyes—their only attraction; two old shriveled hags; four fat, comfortable, coal-black slave-women; and several children. They had their fingernails colored yellow, and all, black and white, wore over their faces the indispensable yashmak, and over their dress the ferraja, or cloak, without which no Turkish woman stirs abroad. As it was cold, they wore under their ferrajas quilted sacques of woolen and calico coming down below the knee, and trousers that bagged over, nearly covering their feet, which were cased in slippers, though one of the negresses rejoiced in gorgeous yellow boots with pointed toes. The children had their hair cut close, and wore their warm sacques down to their feet, made of the gayest calico I ever saw—large figures or broad stripes of red, yellow and green. The boys were distinguished by red fez caps, and the girls wore a colored handkerchief as a turban. They covered the deck with beds and thick comforters, and on these they constantly sat or reclined. When it was absolutely necessary a negress would reluctantly rise and perform some required act of service. They had their own food, which seemed to consist of dark-looking bread, dried fish, black coffee and a kind of confectionery which looked like congealed soapsuds with raisins and almonds in it. Most of their waking hours were employed in devouring oranges and smoking cigarettes.

We had rough weather for several days, and the ship rolled a good deal. The captain made us comfortable in a snug corner on the officers' private deck, where, under the shelter of the bridge, we could enjoy the view. One amusement was to watch the officer of the deck eat his dinner seated on a hatchway just in front of the wheel, and waited on by a most obsequious seaman. The sailor, cap under his arm, would present a plate of something: if the officer ate it the man would retire behind him, and with the man at the wheel watch the disappearance of the contents. If the officer left any or refused a dish, the sailor would go down to the kitchen for the next course, first slipping what was left or [pg 541] rejected behind the wheel, and after presenting the next course to the officer would retire and devour with great gusto the secreted dish; the helmsman sometimes taking a sly bite when the officer was particularly engaged.

The Dardanelles were reached very early in the morning. The night before I had declared my intention to go on deck at daylight and view the Hellespont, but when I awoke and found it blowing a gale, I concluded it would not "pay," and turned in for another nap. All that day we were crossing the Sea of Marmora with the strong current and wind against us, so it was dark before we reached Constantinople, and our ship was obliged to anchor in the outer harbor till the next morning. Seraglio Point rose just before us, and on the left the seven towers were dimly visible in the starlight. We walked the deck and watched the lights glimmer and stream out over the Sea of Marmora, and listened to the incessant barking of the dogs.

Next morning, bright and early, we entered the Bosphorus, rounded Seraglio Point and were soon anchored, with hundreds of other vessels, at the mouth of the Golden Horn. Steam ferryboats of the English kind were passing to and fro, and caïques flitted in and out with the dexterity and swiftness of sea-gulls. Quite a deputation of fez caps came on board to receive the bride and groom, and when we went ashore they were still smoking cigarettes and sipping at what must have been in the neighborhood of their twentieth cup of Turkish coffee. Madame A—— was very cordial when we parted, saying she should call soon upon me, and that I must visit her. We bade adieu to our captain with regret. He was a very intelligent and entertaining man. The officers of the Austrian Lloyd line ought certainly to be very capable seamen. Educated in the government naval schools, they are obliged to serve as mates a certain time, then command a sailing vessel for several years, and finally pass a very strict examination before being licensed as captains of steamers. Amongst other qualifications, every captain acts as his own pilot in entering any port to which he may be ordered. They sail under sealed orders, and our captain said that not until he reached Constantinople would he know the ship's ultimate destination, or whether he would retain command or be transferred to another vessel. It is the policy of the company seldom to send the same steamer or captain over the same route two successive trips. In time of war both captains and ships are liable to naval duty. As we passed the island of Lissa the captain pointed out the scene of a naval engagement between the Austrians and Italians in 1866, in which he had participated. The salary of these officers is only about a thousand dollars a year.

We embarked with our baggage in a caïque, which is much like an open gondola, only lighter and narrower, and generally painted in light colors, yellow being the favorite one, and were soon landed at the custom-house. A franc satisfied the Turk in attendance that our baggage was all right, and it was immediately transferred to the back of an ammale, [pg 542] or carrier. These men take the places of horses and carts with us. A sort of pack-saddle is fastened on their backs, and the weights they carry are astonishing. Our ammale picked up a medium-sized trunk as if it was a mere feather: on top of this was put a hat-box, and with a bag in one hand he marched briskly off as if only enjoying a morning constitutional. We made our way through the dirty streets and narrow alleys to the Hôtel de Byzance in the European quarter. This is a very comfortable hotel, kept in French style, and most of the attendants speak French. Our chambermaid, however, is a man, a most remarkable old specimen in a Turco-Greek dress—long blue stockings and Turkish slippers, very baggy white trousers, a blue jacket, white turban twisted around his fez cap and a voluminous shawl about his waist. His long moustache is quite gray, but his black eyes are keen as a hawk's, and as he moves quickly and silently about my room, arranging and dusting, I fancy how he would look in the same capacity in our house at home.

Our hotel stands in the Rue de Pera, the principal street of the European quarter, and as it is narrow the lights from the shops make it safe and agreeable to walk out in the evening. This is one of the few streets accessible to carriages, though in some parts it is difficult for two to pass each other. Most of the shops are French and display Paris finery, but the most attractive are the fruit-shops with their open fronts, so you take in their inviting contents at a glance. Broad low counters occupy most of the floor, with a narrow passage leading between from the street to the back part of the shop, and counters and shelves are covered with tempting fruits and nuts. Orange boughs with the fruit on decorate the front and ceiling of the shop, and over all presides a venerable Turk. In the evening the shop is lighted by a torch, which blazes and smokes and gives a still more picturesque appearance to the proprietor and his surroundings. You stand in the street and make your purchases, looking well to your bargains, for the old fellow, with all his dignity, will not hesitate to cheat a "dog of a Christian" if he can. From every dark alley as we walked along several dogs would rush out, bark violently, and after following us a little way slink back to their own quarter again. Each alley and street of the city has its pack of dogs, and none venture on the domain of their neighbors. During the day they sleep, lying about the streets so stupid that they will hardly move; in fact, horses and donkeys step over them, and pedestrians wisely let them alone. After dark they prowl about, and are the only scavengers of the city, all garbage being thrown into the streets. The dogs of Pera have experienced, I suppose, the civilizing effects of constant contact with Europeans, as they are not at all as fierce as those of Stamboul. They soon learn to know the residents of their own streets and vicinity, and bark only at strangers.

Quite a pretty English garden has been laid out in Pera, commanding a fine view of the Bosphorus. There is a coffee-house in the centre, with tables and chairs outside, where you can sip your coffee and enjoy the view at the same time. The Turks make coffee quite differently from us. The berry is carefully roasted and then reduced to powder in a mortar. A brass cup, in shape like a dice-box with a long handle, is filled with water and brought to a boil over a brasier of coals: the coffee is placed in a similar brass dice-box and the boiling water poured on it. This boils up once, and is then poured into a delicate little china cup half the size of an after-dinner coffee-cup, and for a saucer you have what resembles a miniature bouquet-holder of silver or gilt filigree. If you take it in true Turkish style, you will drink your coffee without sugar, grounds and all; but a little sugar, minus the coffee-mud at the bottom, is much nicer. Coffee seems to be drunk everywhere and all the time by the Turks. The cafés are frequent, where they sit curled up on the divans dreamily smoking and sipping their fragrant coffee or hearing stories in the flowery style of the Arabian Nights. At the street corners the coffee-vender squats before his little charcoal brasier [pg 543] and drives a brisk business. If you are likely to prove a good customer at the bazaar, you are invited to curl yourself up on the rug on the floor of the booth, and are regaled with coffee. Do you make a call or visit a harem, the same beverage is immediately offered. Even in the government offices, while waiting for an interview with some grandee, coffee is frequently passed round. Here it is particularly acceptable, for without its sustaining qualities one could hardly survive the slow movements of those most deliberate of all mortals, the Turkish officials.

A few days after our arrival my friend of the steamer, Madame A——, the pretty Austrian bride, invited me to breakfast, and sent her husband's brother, a fine-looking young Greek, to escort me to her house. He spoke only Greek and Italian—I neither: however, he endeavored to beguile the way by conversing animatedly in Italian. As he gazed up at the sun several times, inhaled with satisfaction the exhilarating air and pointed to the sparkling waters of the Bosphorus and the distant hills, I presumed he was dilating on the fine weather and the glorious prospect. Not to be outdone in politeness, I smiled a great deal and replied to the best of my ability in good square English, to which he always assented, "Yes, oh yes!" which seemed to be all the English he knew. Fortunately, our walk was not long, and Madame A—— was our interpreter during the breakfast. Her husband was absent.

The breakfast was half German, half Turkish. Here is the bill of fare: Oysters on the shell from the Bosphorus—the smallest variety I have ever seen, very dark-looking, without much flavor; fried goldfish; a sort of curry of rice and mutton, without which no Turkish meal would be complete; cauliflower fritters seasoned with cheese; mutton croquettes and salad; fruit, confectionery and coffee. With a young housekeeper's pride, Madame A—— took me over her house, which was furnished in European style, with an occasional touch of Orientalism. In the centre of the reception-room was a low brass tripod on [pg 544] which rested a covered brass dish about the size of a large punch-bowl. In cold weather this is filled with charcoal to warm the room. "Cold comfort," I should think, when the snow falls, as it sometimes does in Constantinople, and the fierce, cold winds sweep down the Bosphorus from the Black Sea and the Russian steppes. As in all the best houses in Pera, there were bow-windows in the principal rooms of each story. A large divan quite fills each window, and there the Greek and Armenian ladies lean back on their cushions, smoke their cigarettes and have a good view up and down the street. There was a pretty music-room with cabinet piano and harp, and opening from that the loveliest little winter garden. The bow-window was filled with plants, and orange trees and other shrubs were arranged in large pots along the side of the room. The wall at one end was made of rock-work, and in the crevices were planted vines, ferns and mosses. Tiny jets of water near the ceiling kept the top moist, and dripped and trickled down over the rocks and plants till they reached the pebbly basin below. The floor was paved with pebbles—white, gray, black and a dark-red color—laid in cement in pretty patterns, and in the centre was a fountain whose spray reached the glass roof overhead. There were fish in the wide basin around the fountain, which was edged with a broad border of lycopodium. A little balcony opening out of an upper room was covered with vines, and close to the balustrade were boxes filled with plants in full bloom.

But the housetop was my especial admiration. It was flat, with a stone floor and high parapet. On all four sides close to this were wide, deep boxes where large plants and shrubs were growing luxuriantly. Large vases filled with vines and exotics were placed at intervals along the top of the parapet. Part of the roof was covered with a light wooden awning, and a dumb-waiter connected with the kitchen, so that on warm evenings dinner was easily served in the cool fresh air of the roof. The view from here was magnificent—the Golden Horn, Stamboul with its mosques and white minarets, and beyond the Sea of Marmora. Where a woman's life is so much spent in the house, such a place for air and exercise is much to be prized, but I fear my pretty Austrian friend will sigh for the [pg 545] freedom of Vienna after the novelty of the East has worn off.

Of course we paid a visit to Seraglio Point, whose palmy days, however, have passed away. The great fire of 1865 burned the palace, a large district on the Marmora, and swept around the walls of St. Sophia, leaving the mosque unharmed, but surrounded by ruins. The sultan never rebuilds: it is not considered lucky to do so. Indeed, he is said to believe that if he were to stop building he would die. Seraglio Point has been abandoned by the court, and the sultan lives in a palace on the Bosphorus, and one of the loveliest spots on earth is left to decay. We entered through the magnificent gate of the Sublime Porte, passed the barracks, which are still occupied by the soldiers, visited the arsenal and saw the wax figures of the Janizaries and others in Turkish costume. The upper part of the pleasure-grounds is in a neglected state, and those near the water are entirely destroyed. In one of the buildings are the crown-jewels and a valuable collection of other articles. There were elegant toilet sets mounted in gold; the most exquisitely delicate china; daggers, swords and guns of splendid workmanship and sparkling with jewels; Chinese work and carving; golden dishes, cups and vases, and silver pitchers thickly encrusted with precious stones; horse trappings and velvet hangings worked stiff with pearls, gold and silver thread, bits of coral, and jewels; three emeralds as large as small hen's eggs, forming the handle of a dirk; and in a large glass case magnificent ornaments for the turban. There must have been thousands of diamonds in these head-pieces, besides some of the largest pearls I have ever seen; a ruby three-quarters of an inch square; four emeralds nearly two inches long; and a great variety of all kinds of precious stones. The handle and sheath of one sword were entirely covered with diamonds and rubies. There were rings and clasps, and antique bowls filled with uncut stones, particularly emeralds. It recalled the tales of the Arabian Nights. The collection is poorly arranged, and the jewels dusty, so that you cannot examine closely or judge very well of the quality. Those I have mentioned interested me most, but there were many elegant articles of European manufacture which had been presented to the sultan by various monarchs. Near the treasury is a very handsome pavilion, built of white marble, one story high, with fine large plate-glass windows. A broad hall runs through the centre, with parlors on each side. The walls were frescoed, and on the handsomely-inlaid and highly-polished floors were beautiful rugs. The divans were gilt and heavy silk damask—one room crimson, one blue and another a delicate buff. A few large vases and several inlaid Japanese cabinets completed the furniture: the Koran does not allow pictures or statuary. The view from the windows, and especially from the marble terrace in front, is one of the finest I have ever seen. The pavilion [pg 546] stands on the highest part of Seraglio Point, two hundred feet above the water: below it are the ruins of the palace, and the gardens running down to the shore. Just before you the Bosphorus empties into the Marmora; in a deep bay on the Asiatic shore opposite are the islands of Prinkipo, Prote and several others; and on the mainland the view is bounded by the snow-capped mountains of Olympus. On the right is the Sea of Marmora. To the left, as far as you can see, the Bosphorus stretches away toward the Black Sea, its shores dotted with towns, cemeteries and palaces; on the extreme left the Golden Horn winds between the cities of Stamboul and Pera; while behind you is St. Sophia and the city of Stamboul. It is a magnificent view, never to be forgotten. There are several other pavilions near the one just described. A small one in the Chinese style, with piazza around it has the outer wall covered with blue and white tiles, and inside blinds inlaid with mother of pearl. The floor was matted, and the divans were of white silk embroidered with gilt thread and crimson and green floss. A third pavilion was a library.

From the Seraglio we drove to St. Sophia. Stamboul can boast of one fine street, and a few others that are wide enough for carriages. When the government desires to widen a street a convenient fire generally occurs. At the time they proposed to enlarge this, the principal street, it is said the fire broke out simultaneously at many points along the line. As the houses are generally of wood, they burn quickly, and a fire is not easily extinguished by their inefficient fire department. Then the government seizes the necessary ground and widens the street, the owners never receiving any indemnification for their losses. I need not attempt a minute description of St. Sophia. We took the precaution to carry over-shoes, which we put on at the door, instead of being obliged to take off our boots and put on slippers. A firman from the sultan admitted us without difficulty. We admired the one hundred and seventy columns of marble, granite and porphyry, many of which were taken from ancient temples, and gazed up at the lofty dome where the four Christian seraphim executed in mosaic still remain, though the names of the four archangels of the Moslem faith are inscribed underneath them. [pg 547] Behind where the high altar once stood may still be faintly discerned the figure of our Saviour. Several little Turks were studying their Korans, and sometimes whispering and playing much like school-boys at home.

The mosques of Suleiman the Magnificent, Sultan Achmed and Mohammed II. were visited, but next to St. Sophia the mosque which interested me most was one to which we could not gain admittance—a mosque some distance up the Golden Horn, where the sultan is crowned and where the friend of Mohammed and mother of a former sultan are buried. It is considered so very sacred that Christian feet are not allowed to enter even the outer court. As I looked through the grated gate a stout negress passed me and went in. The women go to the mosques at different hours from the men.

Not far from here is a remarkable well which enables a fortune-teller to read the fates of those who consult her. Mr. R——, who has lived for thirty years in Constantinople and speaks Turkish and Arabic as fluently as his own language, told me he was once walking with an effendi to whom he had some months before lent a very valuable Arabic book. He did not like to ask to have it returned, and was wondering how he should introduce the subject when they reached the well. Half from curiosity and half for amusement, he proposed that they should see what the well would reveal to them. The oracle was a wild-looking, very old Nubian woman, and directing Mr. R—— to look steadily down into the well, she gazed earnestly into his eyes to read the fate there reflected. After some minutes she said, "What you are thinking of is lost: it has passed from the one to whom you gave it, and will be seen no more." The effendi asked what the oracle had said, and when Mr. R—— told him he had been thinking of his book, and repeated what the Nubian had uttered, the effendi confessed that he had lent the book to a dervish and feared it was indeed lost. It was a lucky hit of the old darkey's, at any rate.

An opportunity came at last to gratify a long-cherished wish by visiting a harem. Madame L——, a French lady who has lived here many years, visits in the harems of several pashas, and invited me to accompany her. I donned [pg 548] the best my trunk afforded, and at eleven o'clock we set out, each in a sedan chair. I had often wondered why the ladies I saw riding in them sat so straight and looked so stiff, but I wondered no longer when the stout Cretans stepped into the shafts, one before and the other behind, and started off. The motion is a peculiar shake, as if you went two steps forward and one back. It struck me as so ludicrous, my sitting bolt upright like a doll in my little house, that I drew the curtains and had a good laugh at my own expense. Half an hour's ride brought us to the pasha's house in Stamboul—a large wooden building with closely-latticed windows. We were received at the door by a tall Ethiopian, who conducted us across a court to the harem. Here a slave took our wraps, and we passed into a little reception-room. A heavy rug of bright colors covered the centre of the floor, and the only furniture was the divans around the sides. The pasha's two wives, having been apprised of our intended visit, were waiting to receive us. Madame L—— was an old friend and warmly welcomed, and as she spoke Turkish the conversation was brisk. She presented me, and we all curled ourselves up on the divans. Servants brought tobacco in little embroidered bags and small sheets of rice paper, and rolling up some cigarettes, soon all were smoking. The pasha is an "old-style" Turk, and frowns on all European innovations, and his large household is conducted on the old-fashioned principles of his forefathers. His two wives were young and very attractive women. One, with a pale clear complexion, dark hair and eyes, quite came up to my idea of an Oriental beauty. Not content, however, with her good looks, she had her eyebrows darkened, while a delicate black line under her eyes and a little well-applied rouge and powder (I regret to confess) made her at a little distance a still more brilliant beauty. I doubt if any women understand the use of cosmetics as well as these harem ladies. Her dress was a bright-cherry silk, the waist cut low in front, the skirt reaching to her knees. Trousers of the same and slippers to match completed her costume. The other wife was equally attractive, with lovely blue eyes and soft wavy hair. She was dressed in a white Brousa silk waist, richly embroidered with crimson and gold braid, blue silk skirt, white trousers and yellow slippers. They both had on a great deal of jewelry. Several sets, I should think, were disposed about their persons with great effect, though not in what we should consider very good taste. Being only able to wear one pair of earrings, they had the extra pairs fastened to their braids, which were elaborately arranged about their heads and hung down behind. There were half a dozen slaves in the room, who when not waiting on their mistresses squatted on the floor, smoked, and listened to the conversation. Coffee was brought almost immediately, the cups of lovely blue and white china in pretty silver holders on a tray of gilt filigree.