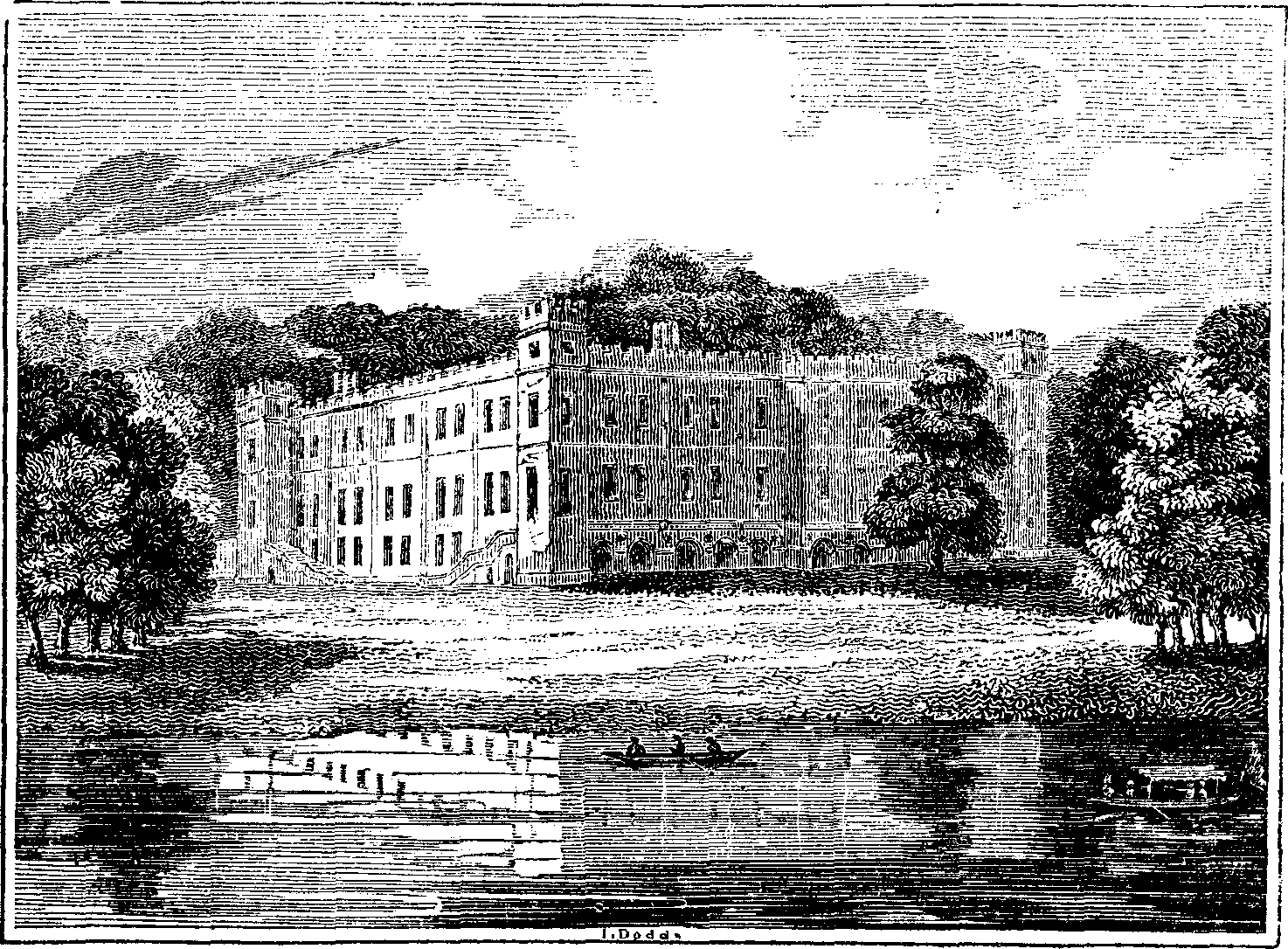

SION HOUSE.

Title: The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 14, No. 389, September 12, 1829

Author: Various

Release date: November 10, 2004 [eBook #14011]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Jonathan Ingram, David Garcia, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction, Vol. 14, Issue 389, September 12, 1829, by Various

| VOL. XIV., NO. 389.] | SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 12, 1829. | [PRICE 2d. |

Taylor, the water poet, or Samuel Ireland, the picturesque Thames tourist, could not, in all their enthusiasm of jingling rhymes and aquatint plates, have exceeded our admiration of Sion House. Its whitened towers and battlemented roof are known to all the swan-hopping and steam navigators of our day, and none who have floated

To where the silver Thames first rural grows,—

can be strangers to the magnificence of the river-front.

Sion House stands in the parish of Isleworth, on the Middlesex bank of the Thames, and opposite Richmond gardens. It is called Sion from a nunnery of Bridgetines of the same name, originally founded at Twickenham, by Henry V. in 1414, and removed to this spot in 1432. This conventual association consisted of sixty nuns, the abbess, thirteen priests, four deacons, and eight lay brethren; the whole thus corresponding, in point of number, with the Apostles and seventy-two disciples of Christ. But the inmates were neither sinless nor spotless; many irregularities existed in the foundation, and consequently, Sion was among the first of the larger monastic institutions suppressed by Henry VIII. The estimated yearly value was 1,944l. 11s. 8-1/2d., now worth 38,891l. 14s. 2d.

After the dissolution of this convent, in 1532, it continued in the crown during the remainder of Henry's reign; and the King confined here his unfortunate Queen, Catherine Howard, from November 14, 1541, to February 10, 1542, being three days before her execution. Edward VI. granted it to his uncle, the Duke of Somerset, who, in 1547, began to build this spacious structure, and finished the shell of it nearly as it now remains. The house is a majestic edifice of white stone, built in a quadrangular form, with a flat and embattled roof, with a square turret at each of the outward angles. In the centre is an enclosed area, now laid out as a flower garden. The gardens were originally enclosed by high walls before the east and west fronts, so as to exclude all prospect; but the Protector, [pg 162] to remedy this inconvenience, built a high terrace in the angle between the walls of the two gardens. After his execution, in 1552, Sion was forfeited; and the house, which was given to John, Duke of Northumberland, then became the residence of his son, Lord Guildford Dudley, and of his daughter-in-law, the unfortunate Lady Jane Grey, who resided at this place when the Duke of Northumberland and Suffolk, and her husband, came to prevail upon her to accept the fatal present of the crown. The duke being beheaded in 1553, Sion House reverted to the crown. Queen Mary restored it to the Bridgetines, who possessed it till they were finally expelled by Elizabeth. In 1604, Sion House was granted to Henry Percy, ninth Earl of Northumberland, in consideration of his eminent services. His son, Algernon, employed Inigo Jones to new face the inner court, and to finish the great hall in the manner in which it now appears. In 1682, Charles, Duke of Somerset, by his marriage with the only child of Joceline, Earl of Northumberland, became possessed of Sion House: he lent the mansion to the Princess Anne, who resided here during the misunderstanding between her and Queen Mary. Upon the duke's death, in 1748, his son, Algernon, gave Sion House to Sir Hugh and Lady Elizabeth Smithson, his son-in-law and daughter, afterwards Duke and Duchess of Northumberland, who made many fine improvements here, under the direction of Robert Adam, Esq. The late duke (who distinguished himself at the battle of Bunker's Hill) passed the principal part of his time at this seat; and here, also, he died, in the year 1815. The present duke has expended immense sums in the improvement of the mansion, grounds, and gardens.

The entrance is from the great road through a fine gateway, having on each side an open colonnade, and on the top a lion passant, the crest of the noble house of Northumberland. A flight of steps leads into the great hall, sixty-six feet by thirty-one feet, and thirty-four in height, paved with white and black marble, and ornamented with colossal statues, and an extremely fine bronze cast of the Dying Gladiator, cast at Rome, by Valadier. A flight of veined marble steps leads to the vestibule, with a floor of scagliola, and twelve large Ionic columns and sixteen pilasters of verde antique. This leads to the dining room, ornamented with marble statues and paintings in chiaro oscuro, after the antique, with, at each end, a circular recess, separated by Corinthian columns, fluted, and a ceiling in stucco, gilt. The drawing room has a rich carved ceiling; and the sides are hung with three-coloured silk damask, the finest of the kind ever executed in England. The antique mosaic tables, and the chimney-piece of this apartment are very splendid, as are also the glasses, which are 108 inches by 65. The great gallery, serving for the library and museum, is 133-½ feet by 14, is in stucco, after the finest remains of antiquity, and is remarkable as the first specimen of stucco work finished in England. A series of medallion-paintings here represents the portraits of all the earls of Northumberland, in succession, and other principal persons of the houses of Percy and Seymour. At each end is a little pavilion, finished in exquisite taste; as is also a beautiful closet in one of the square turrets rising above the roof, which commands an enchanting prospect.

From the east end of the gallery is a suite of private apartments leading back to the great hall, and hung with valuable paintings, among which are the following portraits: Henry Percy, ninth Earl of Northumberland, who was implicated in the Gunpowder Plot, and imprisoned in the Tower; he died November 5, 1632, the anniversary of the day so fatal to his happiness. Lucy, Countess of Carlisle, his daughter, one of the most admired beauties of her time; she also died November 5, 1660. Algernon Percy, tenth Earl of Northumberland. Charles I. and one of his sons, by Sir P. Lely. Charles I. by Vandyke. Queen Henrietta Maria, Vandyke. The Duke of Gloucester, son of Charles I. The Princess Elizabeth, daughter of Charles I.; this is believed to be the only picture extant of this lady. The above portraits of the Stuart family are placed in the apartments in which Charles had so many tender interviews with his children, after the latter were committed to the charge of Earl Algernon Percy, and removed to Sion House, in August, 1646. The earl treated them with parental attention, and obtained a grant of Parliament for the king to be allowed to see them; and in consequence of this indulgence, the latter, who was then under restraint at Hampton Court, often dined with his family at Sion House.

Two of the principal fronts of Sion House command very beautiful scenery; for even the Thames itself appears to belong to the gardens, which are separated into two parts by a serpentine river that communicates with the Thames.

The gardens were principally laid out by Brown: they have, however, been lately improved and re-arranged; and the kitchen-garden is almost unequalled by any thing in the kingdom. Here is a range of hothouses upwards of 400 feet in length, constructed of metal, even to the wall-plates, the doors, and framing of the sashes; the whole being glazed with plate-glass. It is impossible for us to describe the extent and completeness of these improvements, connected with which, Mr. Loudon observes—"nothing can be more gratifying than to see a nobleman employing a part of his income in so judicious and spirited a manner."1

The following is said to have been the epitaph on the tomb of Fair Rosamond, at Godstow:—

Hic jacet in tomba, Rosamundae non Rosamundi,

Non redolet sed olet quae redolere solet.

Within this tomb lies the world's fairest rose;

Whose scent now charms not, but offends the nose.

The couplet on York Minster, translated.

As of all flowers the rose is still the sweetest,

So of all churches this is the completest.

On the stone in the coronation chair in Westminster Abbey.

Ni fallat fatum, Scoti quocunque loquitur,

Inveniant lapidem, regnare teneter ibidem.

Unless old proverbs fail, and wizard's wits be blind,

The Scots shall surely reign, where'er this stone they find.

Luther sent a glass to Dr. Justus Jonas, with the following verses:—

Dat vitrum vitro, Jonae, vitro ipse Lutherus,

Se similem ut fragili noscat uterque vitro.

Luther a glass, to Jonas Glass, a glass doth send,

That both may know ourselves to be but glass, my friend.

Prior's epitaph on himself was parodied as follows:—

Hold Mathew Prior, by your leave,

Your epitaph is very odd:

Bourbon and you are sons of Eve,

Nassau the offspring of a God.

Which being shewn to Swift he wrote the following:—

Hold, Mathew Prior, by your leave,

Your epitaph is barely civil;

Bourbon and you are sons of Eve,

Nassau the offspring of the devil.

In the "Spectator," is part of an epitaph by Ben Jonson, on Mary Herbert, Countess of Pembroke, and sister of Sir Philip Sidney. The following is the whole, taken from the first edition of Jonson's works, collected as they were published:—

Underneath this stone doth lie,

As much virtue as could die;

Which when alive did vigour give,

To as much beauty as could live;

If she had a single fault,

Leave it buried in this vault.

Another on the same, from the same source:—

Underneath this sable hearse,

Lies the subject of all verse,

Sidney's sister, Pembroke's mother,

Death ere thou hast slain another,

Fair, and good, and learn'd as she,

Time shall throw a dart at thee;

Marble piles, let no man raise

To her fame; for after days,

Some kind woman born as she,

Reading this, like Niobe,

Shall turn statue and become

Both her mourner and her tomb.

The Londiners pronounce woe to him, that buyes a horse in Smith-field, that takes a Seruant in Paul's Church, that marries a Wife out of Westminster. Londiners, and all within the sound of Bow-Bell, are in reproch called Cocknies, and eaters of buttered tostes. The Kentish men of old were said to haue tayles, because trafficking in the Low Countries, they neuer paid full payments of what they did owe, but still left some part vnpaid. Essex men are called calues, (because they abound there,) Lankashire eggepies, and to be wonne by an Apple with a red side. Norfolke wyles (for crafty litigiousness:) Essex stiles, (so many as make walking tedious,) Kentish miles (of the length.)

—Moryson's Itinerary, 1617.

This was a cant term that made some figure in the time of the Civil War, and during the Interregnum. It was formed of the initial letters of the names of five eminent Presbyterian ministers of that time, viz. Stephen Marshall, Edmund Calamy, Thomas Young, Matthew Newcomen, and William Spenstow; who, together, wrote a book against Episcopacy, in the year 1641, whence they and their retainers were called Smectymnuans. They wore handkerchiefs about their necks for a note of [pg 164] distinction (as the officers of the parliament-army then did) which afterwards degenerated into cravats.

In the court room of Salters' Hall there appears, framed and glazed, the following "Bill of fare for fifty people of the Company of Salters, A.D. 1506."

| s. | d. | ||

| Thirty-six chickens | 4 | 5 | |

| One swan and four geese | 7 | 0 | |

| Nine rabbits | 1 | 4 | |

| Two rumps of beef tails | 0 | 2 | |

| Six quails | 1 | 6 | |

| Two oz. of pepper | 0 | 2 | |

| Two oz. of cloves and mace | 0 | 4 | |

| One and a half oz. of saffron | 0 | 6 | |

| Eight lbs. of sugar | 0 | 8 | |

| Two lbs. of raisins | 0 | 4 | |

| One lb. of dates | 0 | 4 | |

| One and a half lb. of comfits | 0 | 2 | |

| Half a hundred eggs | 0 | 2½ | |

| Four gallons of curds | 0 | 4 | |

| One ditto gooseberries | 0 | 2 | |

| Bread for the company | 1 | 1 | |

| One kilderkin of ale | 2 | 3 | |

| Herbs | 1 | 0 | |

| Two dishes of butter | 0 | 4 | |

| Four breasts of veal | 1 | 5 | |

| Brawn | 0 | 6 | |

| Quarter load of coals | 0 | 4 | |

| Faggots | 0 | 2 | |

| Three and a half gallons of Gascoigne wine | 2 | 4 | |

| One bottle of Muscovadine | 0 | 8 | |

| Cherries and tarts | 0 | 8 | |

| Verjuice and vinegar | 0 | 2 | |

| Paid the cook | 3 | 4 | |

| Perfume | 0 | 2 | |

| One bushel and a half of meal | 0 | 8 | |

| Water | 0 | 3 | |

| Garnishing the vessels | 0 | 3 | |

| Total of feast for 50 people | £1 | 13 | 2½ |

We have a vulgar book called Frauds of London laid open, and Vidocq's fourth volume will serve for Paris, since he defines the nomenclature—nay the very craft of thieves with great minuteness: thus—

"The Chevaliers Grimpants, called also voleurs au bonjour, donneurs de bonjours, bonjouriers, are those who introduce themselves into a house and carry off in an instant the first movable commodity that falls in their way. The first bonjouriers were I am assured, servants out of place. They were at first few in number, but, soon acquiring pupils, their industry increased so rapidly, that from 1800 to 1812, there was scarcely a day that robberies were not committed in Paris of from a dozen to fifteen baskets of plate.

"The Almanach du commerce, l'Almanach royal, and that with twenty-five thousand addresses in it, are, for bonjouriers, the most interesting works that can be published. Every morning, before they go out, they consult them; and when they propose visiting any particular house, it is very seldom that they are not acquainted with the names of at least two persons in it; and that they may effect an entrance, they inquire for one when they see the porter, and endeavour to rob the other.

"A bonjourier has always a gentlemanly appearance, and his shoes always well made and thin. He gives the preference to kid before any other leather, and takes care to bruise and break the sole that it may not creak or make any noise; sometimes the sole is made of felt; at other times, and especially in winter, the kid slipper, or dogskin shoe, is replaced by list shoes, with which they can walk, go up stairs, or descend a staircase, without any noise. The theft au bonjour, is effected without violence, without skeleton keys, without burglariously entering. If a thief sees a key in a door of a room, he first knocks very gently, then a little harder, then very loudly; if no person answers, he turns the handle, and thus enters the antechamber. He then advances to the eating-room, penetrates even to the adjoining apartments, to see if there be any person there; returns, and if the key of the sideboard is not to be seen, he looks in all the places in which he knows it is generally deposited, and if he finds it, he instantly uses it to open the drawers, and taking out the plate, he places it generally in his hat, after which, he covers it with a napkin, or fine cambric handkerchief, which, by its texture and whiteness, announces the gentleman. Should the bonjourier, whilst on his enterprise, hear any person coming, he goes straight towards him, and accosting him, wishes him good morning (le bonjour) with a smiling [pg 165] and almost familiar air, and inquires if it be not Monsieur 'such a one,' to whom he has the honour of addressing himself. He is directed to the story higher or lower, and, then still smiling, evincing the utmost politeness and making a thousand excuses and affected bows, he withdraws. It may so happen, that he has not had time to consummate his larceny, but most frequently the business is perfected, and the discovery of loss only made too late to remedy it.

"The majority of the thieves in this particular line commence their incursions with morning, at the hour when the housekeepers go out for their cream, or have a gossip whilst their masters and mistresses are in bed. Other bonjouriers do not open the campaign until near dinner time; they pitch upon the moment when the plate is laid upon the table. They enter, and in the twinkling of an eye, they cause spoons, forks, ladles, &c. to vanish. This is technically termed goupiner à la desserte, (clearing the cloth).

"One day one of these goupineurs à la desserte was on the look out in a dining room, when a servant entered carrying two silver dishes, between which were some fish. Without being at all disconcerted, he went up to her, and said—'Well, go and bring up the soup, the gentlemen are in a hurry.'

"'Yes, sir,' said the maid, taking him for one of the guests, 'it is quite ready, and if you please you can announce the dinner.'

"At the same time she ran to the kitchen, and the goupineur, after having hastily emptied the dishes, thrust them between his waistcoat and shirt. The girl returned with the broth, the pretended guest had retired, and there was not a single piece of silver left on the table. They denounced this theft to me, and from the statement given, as well as the description of the person committing the robbery, I thought I had recognised my man. He was called Cheinaux, alias Bayer, and was discovered and apprehended in Saint Catherine's market. His shirt was marked with the circumference of the dishes, in consequence of the remains of the sauce left in them.

"Another body of bonjouriers more particularly direct their talents to furnished houses.

"The individuals forming this class are on foot from the dawn of day. Their talent is evinced by the adroit mode in which they baffle the vigilance of the porters. They go up the staircase, sometimes on one pretext, and sometimes on another, look round them, and if they find any keys in the doors, which is common enough, they turn them with the least possible noise. Once in the room, if the occupant be asleep, farewell to his purse, his watch, his jewels, and all that he has that is valuable. If he awakes, the visiter has a thousand excuses ready.

"'A thousand pardons, sir, I thought this was No. 13;' or, 'Was it you, sir, who sent for a bootmaker, tailor, hairdresser,'" &c. &c.

"The robbery à la detourne is that which is effected whilst making purchases at a shop. This species of plunder is practised by individuals of both sexes; but the détourneuses, or lady prigs, are generally esteemed more expert than the detourneurs, or gentlemen prigs. The reason of this superiority consists entirely in the difference of dress; women can easily conceal a very large parcel.

"In retail shops it would be an advisable plan, when there are many customers to serve, that from time to time the shopmen should say to each other, deux sur dix (two on ten), or else allumez les gonzesses (twig the prigs). I will bet a thousand to one, that on hearing these words, the thieves, who have very fine ears, will make haste to take themselves away.

"Shopkeepers of what class soever, particularly retailers, cannot be too much on their guard; they should never forget that in Paris there are thousands of male and female thieves à la detourne, I here only speak of robbers by profession; but there are also amateurs, who, beneath the cover of a well-established reputation, make small acquisitions slyly and unsuspectedly. They are very honest people they say, who with little scruple indulge their propensity for a rare book, a miniature, a cameo, a mosaic, a manuscript, a print, a medal, or a jewel that pleases them; they are called Chipeurs. If the Chipeur be rich, no heed is paid to him, he is too much above such a larceny to impute it to him as a crime; if he be poor, he is denounced to the attorney-general, and sent to the galleys, because he robbed from necessity. It must be owned that we have strange ideas as to honesty and dishonesty."

This is what we call Shoplifting. A milliner once told us that ribands and flowers not unfrequently attach themselves to the cuffs and sleeves of fair purchasers.

Belong to the same class of thieves, and are gipsies, Italians, or Jews. The female Careurs are very expert in robbing priests; and Vidocq apprehended a mother and daughter for more than sixty such offences.

"The gipsies do not confine themselves to these means of appropriating to themselves the property of another: they frequently commit murder, and they have the less objection to commit a murder, because they have no feeling of any kind of remorse; and they have a peculiar kind of expiation whereby they purify themselves. For a year they wear a coarse woollen shirt, and abstain from 'work' (robbing). This period elapsed, they believe themselves white as snow. In France, the majority of the persons of this caste call themselves Catholics, and have every external show of great devotion. They always carry about them rosaries and a crucifix; they say their prayers night and morning, and follow the service with much attention and precision. In Germany, they seldom exercise any other calling than that of horse doctor, or herbalist: some addict themselves to medicine, that is to say, profess to be in possession of secret means of effecting cures. A vast number of them travel in bodies, some tell fortunes, others mend glass, china, pots, and pans; woe to the inhabitants of the country overrun by these vagabonds. There will infallibly be a mortality amongst the cattle, for the gipsies are very clever in killing them, without leaving any traces which can be converted into a charge of malevolence against them. They kill the cows by piercing them to the heart with a long and very fine needle, so that the blood flowing inwardly, it may be supposed that the animal died of disease. They stifle poultry with brimstone; they know that then they will give them the dead birds; and whilst they imagine that they have a taste for carrion, they make good cheer, and eat delicious meat. Sometimes they want hams, and then they take a red herring and hold it under the nose of a pig, which, allured by the smell, would follow them to the world's end."

Are fellows who plunder carriages of portmanteaus, imperials, &c.

"One day I followed a famous rouletier named Gosnet. On reaching the Rue Saint Denis, he jumped up on a coach, put on a cloak and cotton cap which he found lying close to his hand, and in this dress got down again with a portmanteau under his arm. It was not later than two o'clock in the afternoon; but to elude all suspicion, Gosnet, on alighting, went straight to the conducteur (guard), and after having spoken to him, turned down a street close at hand. I was in waiting for him, he was apprehended and sentenced."

Or pickpockets are as abundant as mushrooms.

"There was in Paris a thief of such incredible dexterity that he robbed without an accomplice. He placed himself in front of a person, put his hand behind him, and took either a watch or some other valuable. This species of thievery is called the vol à la chicane.

"A fellow named Molin, alias Moulin le Chapelier, being under the portico des Français, was desirous of stealing a gentleman's purse: the sufferer, who was near the wall, thought he felt some one picking his pocket; Molin, full of presence of mind, effected his object in an instant, the purse was torn from the pocket, he opened it, and taking out a coin, asked for a ticket for the play. At the same moment the person robbed said to him—'But, sir, you have taken my purse, give it to me.'—'The devil I have,' replied Molin with an air of affected surprise, 'are you quite sure?' Then looking attentively at it—'By heavens! I thought it was mine. Oh! sir, I ask your pardon.'

"At the same time he returned the purse, and all the bystanders were persuaded that he had done it involuntarily. This is being fly, or I know nothing about it.

"At the time of the great fog, Molin and a pal named Dorlé were stationed at the environs of the Place des Italiens. An old gentleman passed, and Dorlé stole his watch which he passed to Molin. The darkness was so great that he could not discern if it were a repeater or not, and to ascertain this, Molin pressed down the spring: the hammer instantly struck on the bell, and by the sound the old man knew his watch, and instantly cried out—'My watch! my watch! pray restore me my watch, it belonged to my grandfather, and is a family piece.'

"Whilst uttering these lamentations, he endeavoured to go in the direction whence the sound had proceeded, to get his watch as he expected and hoped to do. He came close up to Molin, who, under cover of the dense fog, put his hand with the watch in it close to the [pg 167] old gentleman's ear, and pushing the spring again, said, whilst the watch was striking—'Listen then to its sounds for the last time;' and with this cruel advice the two thieves then went away, leaving the worthy undone elderly to bewail his loss.

"The ancient voleurs à la tire cite still, as amongst the celebrated personages of their profession, two Italians, the brothers Verdure, the eldest of whom, convicted of forming one of a band of chauffeurs, was sentenced to death. On the day of execution, the younger, who was at liberty, wished to see his brother as he left the prison, and with several of his comrades took his station on the road. When thieves go out in the evening into a crowd they generally have a preconcerted word of alarm or summons, by which to call or distinguish their accomplices. Young Verdure, on seeing the fatal car, uttered his, which was lorge, to which the criminal, looking about him, replied lorge. This singular salute given and returned, it may be imagined that young Verdure retired. On his road he had already stolen two watches; he saw his brother's head fall from the block, and either before or afterwards he was determined to carry matters to their utmost.

"The crowd having dispersed he returned to the cabaret with his comrades. 'Well, well,' said he, laying down on the table four watches and a purse, 'I think I have not played my cards amiss. I never thought to have made such a haul at my frater's death; I am only sorry he's not here to have his share of the swag.'"

Ring-droppers, and Emporteurs ("gentlemen who lose themselves") are next shown up: to the latter class belong the fellows who, under pretence of inquiring their road, fall into conversation with you, invite you to billiards, and cheat you.2 Ring-droppers are very troublesome in Paris, especially in the Champs Elyseés, where you may be teazed to buy a copper-framed eye-glass which they have just "found."

Were thieves assuming the garb of country dealers, or travelling hawkers; and they sought to wring from their victims a confession of where they had concealed their treasure, by applying fire to the soles of their feet.

The Fourth Volume closes abruptly with a story of a gang of them, which has all the horrors of rack and torture. In the Translator's sequel we find the following:—

"Since the commencement of these Memoirs, M. Vidocq has given up his paper manufactory at St. Mandé, and has been subsequently confined in Sainte Pelagie for debt. His embarrassments are stated to have arisen from a passion for gambling, a propensity which, once indulged, takes deep root in the human mind; and few indeed, lamentably few, are those who can effectually eradicate the fatal passion. Vidocq, who could assume all shapes like a second Proteus, who underwent bitter hardships, and unsparingly jeopardized his life at any time, could not resist the fell temptation which has brought him to distress and a prison.

"It has been stated in some of the Journals that Vidocq has a son named Julius, who was condemned to the galleys, and when liberated was employed by his father at Sainte Mandé. This must be another bitter in his life's cup, which Vidocq seems condemned to drain to the very dregs."

We need hardly be told why Vidocq has withheld the information respecting the state of crime in France, which he promised, and made a grand parade of possessing. The length to which his Memoirs have been spun out is tedious, and the air of romance which he has given to some scenes in the concluding volume, almost invalidates its forerunners. Still we are bound to confess that his adventures are equal in interest to any work of fact or fiction that has appeared for several years. We omit the translations of some slang songs, one of which appeared recently in Blackwood's Magazine; still, they are exceedingly clever in their way.

The present volume has a portrait of Vidocq, upon which we hope the physiognomists will speculate; for with all his peccadilloes, (and a hard set of features which the engraver has probably hardened) the author must be a clever and a very pleasant fellow; and we wish some myrmidon of our police—some English Vidocq—would write four pretty pocket volumes like those of the French policeman. Perhaps some of the new appointed will take this hint.

To conclude, after what we have said, our readers need not be recommended to turn to Vidocq's Memoirs. They will find the translation generally well executed, although we have detected several slips in the last volume.

The town of Southwell, in the county of Nottingham, is situated in the midst of an amphitheatre of well-wooded hills; the soil is rich, and the air, from the vicinity of the River Trent, is remarkably pure. It is fourteen miles north-east of Nottingham, about as many south-east of Mansfield, and eight south-west from Newark; the River Greet, famous for red trout, runs by the side of the town, falling into the Trent, at about three miles distance.

The most ancient part of the church is of the order usually called Saxon, and from tradition is said to have been built in the time of Harold, predecessor of William I. But there is no history or written instrument of any kind now extant, concerning the origin of this structure. The two side aisles are of pure Norman architecture. The choir was built in the reign of Edward III. as appears by a license of the eleventh year of that king's reign, to the chapter, to get stones from a quarry in Shirewood Forest for building the choir. The chapter-house is a detached building, connected by a cloister with the north aisle of the choir, and is on the model of that at York. The arch of entrance from the aisle, is said to exceed in elegance and correctness of execution, almost every thing of the kind in the kingdom; the chapter-house is of Gothic architecture, and the arch forming the approach is considered of modern insertion, the sculpture being finer and more delicate than any thing near it. This church and Ripon are said to be the only parochial, as well as collegiate, churches now in England, the rest having been dissolved by Henry VIII. or his successors.

At the Reformation, its chantries were dissolved, and the order of priests expelled about the year 1536. In 1542, Lee, then Archbishop of York, granted, by indenture to the king, the manor of Southwell. In the thirty-fourth year of his reign, Henry VIII., by act of parliament, declared Southwell the head and mother church of the town and county of Nottingham, and soon afterwards re-founded and re-endowed it, probably at the instance of Cranmer, at that time in the height of favour, who was a native of Nottinghamshire, not far from Southwell. Soon after the accession of Edward VI. the chapter was again dissolved, and its prebendal, and other estates granted to John, Earl of Warwick, afterwards made Duke of Northumberland; by him they were sold to John Beaumont, Master of the Rolls, and coming soon afterwards to the crown, by escheat, were granted to the favourite Northumberland, who retained them until his attainder in 1553, when they again reverted to the crown; and by Queen Mary were restored to the Archbishop of York, in as ample manner as they had before been holden. It appears from the Registrum Album, a register of the church, that in the latter end of the reign of William I. there were at least ten prebends. In the office of augmentation, an estimate of Southwell College, in the first of Edward VI. states King Edgar to have been the founder of the church, which consisted of sixteen prebends, and sixteen vicars. There are now sixteen [pg 169] prebends, of which the Archbishop of York is sole patron, a vicar-general appointed out of the prebendaries by the chapter, six vicars, and six choristers. Alfric, appointed to the See of York in 1023, gave two large bells to the church of Southwell (William of Malmsbury.) This was about the time of bells coming generally into use. King Stephen granted that the canons of Southwell should hold the woods of their prebends, in their own hands, which succeeding monarchs, Henry II. Richard, John, and Henry III. confirmed. There are two fellowships, and two scholarships, founded in St. John's College, Cambridge, by Dr. Keton, canon of Sarum, twenty-second Henry VI. to be presented by the master, fellows, and scholars of that college, to persons having served as choristers in the chapter of Southwell. In the civil wars nearly all the records of Southwell Church were destroyed, the Registrum Album escaping, which contains grants of most of the revenues belonging to the church, from soon after the conquest, nearly to the end of Henry VIII. Southwell is supposed by antiquarians to be the "Ad Pontem" of the Romans, one of the stations on the Roman Way from London to Lincoln, situated at a distance from any route of importance between the most frequented part of the kingdom. For many centuries it was hardly known by name—and, till within thirty years there was no turnpike road to it in any direction. Thus denied access to the rest of the world, the people of Southwell lived a separate and distinct society, retaining their own manners untainted by the world; and among them traditions were handed down pure and unadulterated by the speculations of the learned, or the discoveries of antiquarians.

Anthony Dumps, the father of my hero (the subject matter of a story being always called the hero, however little heroic he may personally have been) married Dora Coffin on St. Swithin's day in the first year of the last reign.

Anthony was then comfortably off, but through a combination of adverse circumstances he went rapidly down in the world, became a bankrupt, and being obliged to vacate his residence in St. Paul's Churchyard, he removed to No. 3, Burying Ground Buildings, Paddington Road, where Mrs. Dumps was delivered of a son.

The depressed pair agreed to christen their babe Simon, but the name was registered in the parish book with the first syllable spelt "S—I—G—H;"—whether the trembling hand of the afflicted parent orthographically erred, or whether a bungling clerk caused the error I know not; but certain it is that the infant Dumps was registered SIGHMON.

Sighmon sighed away his infancy like other babes and sucklings, and when he grew to be a hobedy-hoy, there was a seriousness in his visage, and a much-ado-about-nothing-ness in his eye, which were proclaimed by good natured people to be indications of deep thought and profundity; while others less "flattering sweet," declared they indicated naught but want of comprehension, and the dulness of stupidity.

As he grew older he grew graver, sad was his look, sombre the tone of his voice, and half an hour's conversation with him was a very serious affair indeed.

Burying Ground Buildings, Paddington Road, was the scene of his infant sports. Since his failure, his father had earned his livelyhood, by letting himself out as a mute, or mourner, to a furnisher of funerals.

"Mute" and "voluntary woe" were his stock in trade.

Often did Mrs. Dumps ink the seams of his small-clothes, and darken his elbows with a blacking brush, ere he sallied forth to follow borrowed plumes; and when he returned from his public performance (oft rehearsed) Master Sighmon did innocently crumple his crapes, and sport with his weepers.

His melancholy outgoings at length were rewarded by some pecuniary incomings. The demise of others secured a living for him, and after a few unusually propitious sickly seasons, he grimly smiled as he counted his gains: the mourner exulted, and, in praise of his profession, the mute became eloquent.

Another event occurred: after burying so many people professionally, he at length buried Mrs. Dumps; that, of course, was by no means a matter of business. I have before remarked that she was descended from the Coffins; she was now gathered to her ancestors.

Dumps had long been proud of gentility of appearance, a suit of black had been his working day costume, nothing therefore could be more easy than for Dumps to turn gentleman. He did so; took a villa at Gravesend, chose for his [pg 170] own sitting room a chamber that looked against a dead wall, and whilst he was lying in state upon the squabs of his sofa, he thought seriously of the education of his son, and resolved that he should be instantly taught the dead languages.

Sighmon Dumps was decidedly a young man of a serious turn of mind. The metropolis had few attractions for him, he loved to linger near the monument; and if ever he thought of a continental excursion, the Catacombs and Père la Chaise were his seducers.

His father died, his old employer furnished him with a funeral; the mute was silenced, and the mourner was mourned.

Sighmon Dumps became more serious than ever; he had a decided nervous malady, an abhorrence of society, and a sensitive shrinking when he felt that any body was looking at him. He had heard of the invisible girl; he would have given worlds to have been an invisible young gentleman, and to have glided in and out of rooms, unheeded and unseen, like a draft through a keyhole. This, however, was not to be his lot; like a man cursed with creaking shoes, stepping lightly, and tiptoeing availed not; a creak always betrayed him when he was most anxious to creep into a corner.

At his father's death he found himself possessed of a competency and a villa; but he was unhappy, he was known in the neighbourhood, people called on him, and he was expected to call on them, and these calls and recalls bored him. He never, in his life, could abide looking any one straight in the face; a pair of human eyes meeting his own was actually painful to him. It was not to be endured. He sold his villa, and determined to go to some place where, being a total stranger, he might pass unnoticed and unknown, attracting no attention, no remarks.

He went to Cheltenham and consulted Boisragon about his nerves, was recommended a course of the waters, and horse exercise.

The son of the weeper very naturally thought he had already "too much of water;" he, however, hired a nag, took a small suburban lodging, and as nobody spoke to him, nor seemed to care about him, he grew better, and felt sedately happy. This blest seclusion, "the world forgetting, by the world forgot," was not the predestined fate of Sighmon: odd circumstances always brought him into notice. The horse he had hired was a piebald, a sweet, quiet animal, warranted a safe support for a timid invalid. On this piebald did Dumps jog through the green lanes in brown studies.

One day as he passed a cottage, a face peered at him through an open window; he heard an exclamation of delight, the door opened, and an elderly female ran after him, entreating him to stop; much against the grain he complied.

"'Twas heaven sent you, sir," said his pursuer, out of breath; "give me for the love of mercy the cure for the rhumatiz."

"The what?" said Dumps.

"The rhumatiz, sir; I've the pains and the aches in my back and my bones—give me the dose that will cure me."

In vain Dumps declared his ignorance of the virtues of "medicinal gums." The more he protested, the more the old woman sued; when to his horror a reinforcement joined her from the cottage, and men, women, and children implored him to cure the good dame's malady. At length watching a favourable opportunity, he insinuated his heel into the side of the piebald, and trotted off, while entreaties mingled with words of anger were borne to him on the wind.

He determined to avoid that green lane in future, and rode out the next day in an opposite direction: as he trotted through a village a girl ran after him, shouting for a cure for the hooping cough, a dame with a low curtsey solicited a remedy for the colic, and an old man asked him what was good for the palsy. These unforeseen, these unaccountable attacks were fearful annoyances to so retiring a personage as Dumps. Day after day, go where he would, the same things happened. He was solicited to cure "all the ills that flesh is heir to." He was not aware (any more than the reader very possibly may be) that in some parts of England the country people have an idea that a quack doctor rides a piebald horse; why, I cannot explain, but so it is, and that poor Dumps felt to his cost. Life became a burthen to him; he was a marked man; he, whose only wish was to pass unnoticed, unheard, unseen; he, who of all the creeping things on the earth, pitied the glowworm most, because the spark in its tail attracted observation. He gave up his lodgings and his piebald, and went "in his angry mood to Tewksbury."

I ought ere this to have described my hero. He was rather embonpoint, but fat was not with him, as it sometimes is, twin brother to fun; his fat was weighty, [pg 171] he was inclined to blubber. He wore a wig, and carried in his countenance an expression indicative of the seriousness of his turn of mind.

He alighted from the coach at the principal inn at Tewksbury; the landlady met him in the hall, started, smiled, and escorted him into a room with much civility. He took her aside, and briefly explained that retirement, quiet, and a back room to himself were the accommodations he sought.

"I understand you sir," replied the landlady, with a knowing wink, "a little quiet will be agreeable by way of change; I hope you'll find every thing here to your liking." She then curtseyed and withdrew.

"Frank," said the hostess to the head waiter, "who do you think we've got in the blue parlour? you'll never guess! I knew him the minute I clapped eyes on him; dressed just as I saw him at the Haymarket Theatre, the only night I ever was at a London stage play. The gray coat, and the striped trousers, and the hessian boots over them, and the straw hat out of all shape, and the gingham umbrella!"

"Who is he, ma'am?" said Frank. "Why, the great comedy actor, Mr. Liston," replied the landlady, "come down for a holiday; he wants to be quiet, so we must not blab, or the whole town will be after him."

This brief dialogue will account for much disquietude which subsequently befell our ill fated Dumps. People met him, he could not imagine why, with a broad grin on their features. As they passed they whispered to each other, and the words "inimitable," "clever creature," "irresistibly comic," evidently applied to himself, reached his ears.

Dumps looked more serious than ever; but the greater his gravity, the more the people smiled, and one young lady actually laughed in his face as she said aloud, "Oh, that mock heroic tragedy look is so like him!"

Sighmon sighed for the seclusion of number three, Burying Ground Buildings, Paddington Road.

One morning his landlady announced, with broader grin than usual, that a gentleman desired to speak with him; he grumbled, but submitted, and the gentleman was announced.

"My name, sir, is Opie," said the stranger; "I am quite delighted to see you here. You intend gratifying the good people of Tewksbury of course?"

"Gratifying! what can you mean?"

"If your name is announced, there'll not be a box to be had."

"I always look after my own boxes, I can tell you," replied Dumps.

"By all means, you will come out here of course?"

"Come out? to be sure, I sha'n't stay within doors always."

"What do you mean to come out in?"

"Why, what I've got on will do very well."

"Oh, that's so like you," said Opie, shaking his sides with laughter, "you really are inimitable!—What character do you select here?"

"Character!" said Dumps, "the stranger."

"The Stranger! you?"

"Yes, I."

"And you really mean to come out here as the Stranger?" said Opie.

"Why, yes to be sure—I'm but just come."

"Then I shall put your name in large letters immediately, we will open this evening; and as to terms, you shall have half the receipts of the house."

Off ran Mr. Opie, who was no less a personage than the manager of the theatre, leaving Dumps fully persuaded that he had been closeted with a lunatic.

Shortly afterwards he saw a man very busy pasting bills against a wall opposite his window, and so large were the letters that he easily deciphered, "THE CELEBRATED MR. LISTON IN TRAGEDY. This evening THE STRANGER, the Part of THE STRANGER BY MR. LISTON." Dumps had never seen the inimitable Liston, indeed comedy was quite out of his way. But now that the star was to shine forth in tragedy, the announcement was congenial to the serious turn of his mind, and he resolved to go.

He ate an early dinner, went by times to the theatre, and established himself in a snug corner of the stage box. The house filled, the hour of commencement arrived, the fiddlers paused and looked towards the curtain, but hearing no signal they fiddled another strain. The audience became impatient; they hissed, they hooted, and they called for the manager: another pause, another yell of disapprobation, and the manager pale and trembling appeared, and walked hat in hand to the front of the stage. To Dumps's great surprise it was the very man who visited him in the morning. Mr. Opie cleared his throat, bowed repeatedly, moved his lips, but was inaudible amid the shouts of "hear him." At length silence was obtained, and he spoke as follows:—

"Ladies and Gentlemen,

"I appear before you to entreat your kind and considerate forbearance; I lament as much, nay more than you, the absence of Mr. Liston; but, in the anguish of the moment, one thought supports me, the consciousness of having done my duty. (Applause.) I had an interview with your deservedly favourite performer this morning, and every necessary arrangement was made between us. I have sent to his hotel, and he is not to be found. (Disapprobation.) I have been informed that he dined early, and left the house, saying that he was going to the theatre; what accident can have prevented his arrival I am utterly unable to—"

Mr. Opie now happened to glance towards the stage box, surprise! doubt! anger! certainty! were the alternate expressions of his pale face, and widely opened eyes; and at length pointing to Dumps he exclaimed—

"Ladies and gentlemen, it is my painful duty to inform you that Mr. Liston is now before you; there he sits at the back of the stage box, and I trust I may be permitted to call upon him for an explanation of his very singular conduct."

Every eye turned towards Dumps, every voice was uplifted against him; the man who could not endure the scrutiny of one pair of eyes, now beheld a house full of them glaring at him with angry indignation. His head became confused, he had a slight consciousness of being elbowed through the lobby, of a riot in the crowded street, and of being protected by the civil authorities against the uncivil attacks of the populace. He was conveyed to bed, and awoke the next morning with a very considerable accession of nervous malady.

He soon heard that the whole town vowed vengeance against the infamous and unprincipled impostor who had so impudently played off a practical joke on the public, and at dead of night did he escape from the town of Tewksbury, in a return mourning coach, with which he was accommodated by his tender hearted landlady.

Our persecuted hero next occupied private apartments at a boarding-house at Malvern. Privacy was refreshing, but, alas! its duration was doomed to be short. A young officer who had witnessed the embarrassment of "the stranger" at Tewksbury, recognised the sufferer at Malvern, and knowing his nervous antipathy to being noticed, he wickedly resolved to make him the lion of the place.

He dined at the public table, spoke of the gentleman who occupied the private apartments, wondered that no one appeared to be aware who he was, and then in confidence informed the assembled party that the recluse was the celebrated author of the "Pleasures of Memory," now engaged in illustrating "HIS ITALY" with splendid embellishments from the pencils of Stothard and Turner.

Dumps again found himself an object of universal curiosity, every body became officiously attentive to him, he was waylaid in his walks, and intentionally intruded upon by accident in his private apartments; a travelling artist requested to be permitted to take his portrait for the exhibition, a lady requested him to peruse her manuscript romance and to give his unbiassed opinion, and the master of the boarding-house waited upon him by desire of his guests to request that he would honour the public table with his company. Several ladies solicited his autograph for their albums, and several gentlemen called a meeting of the inhabitants, and resolved to give him a public dinner; a craniologist requested to be permitted to take a cast of his head, and as a climax to his misery, when he was sitting in his bedchamber thinking himself at least secure for the present, the door being bolted; he looked towards the Malvern Hills, which rise abruptly immediately at the back of the boarding-house, and there he discovered a party of ladies eagerly gazing at him with long telescopes through the open windows!

He left Malvern the next morning, and went to a secluded village on the Welsh coast, not far from Swansea.

The events of the last few weeks had rendered poor Sighmon Dumps more sensitively nervous than ever. His seclusion became perpetual, his blind always down, and he took his solitary walks in the dusk of the evening. He had been told that sea sickness was sometimes beneficial in cases resembling his own; he, therefore, bargained with some boatmen, who engaged to take him out into the channel, on a little experimental medicinal trip. At a very early hour in the morning he went down to the beach, and prepared to embark. He had observed two persons who appeared to be watching him, he felt certain they were dogging him, and just as he was stepping into the boat they seized him, saying, "Sir, we know you to be the great defaulter who has been so long concealed on this coast; we know you are trying to escape to America, but you must come with us."

Sighmon's heart was broken. He felt it would be useless to endeavour to explain or to expostulate; he spoke not, but was passively hurried to a carriage in which he was borne to the metropolis as fast as four horses could carry him, without rest or refreshment. Of course, after a minute examination, he was declared innocent, and was released; but justice smiled too late, the bloom of Sighmon's happiness had been prematurely nipped.

He called in the aid of the first medical advice, grew a little better; and when the doctor left him he prescribed a medicine which he said he had no doubt would restore the patient to health. The medicine came, the bottle was shaken, the contents taken—Sighmon died!

It was afterwards discovered that a mistake had occasioned his premature departure; a healing liquid had been prescribed for him, but the careless dispenser of the medicine had dispensed with caution on the occasion, and Dumps died of a severe oxalic acidity of the stomach! By his own desire he was interred in the churchyard opposite to Burying Ground Buildings, Paddington Road. His funeral was conducted with almost as much decorum as if his late father the mute had been present, and he was left with—

"At his head a green grass turf,

And at his heels a stone."

But even there he could not rest! The next morning it was discovered that the body of Sighmon Dumps had been stolen by resurrection men!—Sharpe's Mag.

Who says that Maria Gray is dead,

And that I in this world can see her never?

Who says she is laid in her cold death-bed,

The prey of the grave and of death for ever?

Ah! they know little of my dear maid,

Or kindness of her spirit's giver!

For every night she is by my side,

By the morning bower, or the moonlight river.

Maria was bonny when she was here,

When flesh and blood was her mortal dwelling;

Her smile was sweet, and her mind was clear,

And her form all human forms excelling.

But O! if they saw Maria now,

With her looks of pathos and of feeling,

They would see a cherub's radiant brow,

To ravish'd mortal eyes unveiling.

The rose is the fairest of earthly flowers—

It is all of beauty and of sweetness—

So my dear maid, in the heavenly bowers,

Excels in beauty and in meetness.

She has kiss'd my cheek, she has komb'd my hair,

And made a breast of heaven my pillow,

And promised her God to take me there,

Before the leaf falls from the willow.

Farewell, ye homes of living men!

I have no relish for your pleasures—

In the human face I nothing ken

That with my spirit's yearning measures.

I long for onward bliss to be,

A day of joy, a brighter morrow;

And from this bondage to be free,

Farewell thou world of sin and sorrow!

Blackwood's Magazine.

Bewick's first tendency to drawing was noticed by his chalking the floors and grave-stones with all manner of fantastic figures, and by sketching the outline of any known character of the village, dogs, or horses, which were instantly recognised as faithful portraits. The halfpence he got were always laid out in chalk or coarse pencils; with which, when taken to church, he scrawled over the ledges of the bench ludicrous caricatures of the parson, clerk, and the more prominent of the congregation. These boards are now in the possession of the Duke of Northumberland, by whom they were replaced; and when his chalk was exhausted, he resorted to a pin or a nail as a substitute. In consequence of this propensity to drawing, some liberal people, of whom he says, there were many in Newcastle, got him bound apprentice to a Mr. Bielby, an engraver on copper and brass. During this period he walked most Sundays to Ovingham (ten miles,) to see his parents; and, if the Tyne was low, crossed it on stilts; but, if high-flowing, hollaed across to inquire their health, and returned. This infant genius (but it was the infant Hercules struggling with the snakes) was bound down by his master to cut clock-faces and door-knockers—ay, clock-faces and door-knockers!—and he actually showed me several in the streets of Newcastle he had cut. At this time he was employed by Bielby to cut on wood the blocks for Dr. Hutton's great work on Mensuration. Hutton was then a schoolmaster at Newcastle (1770.)

After his apprenticeship, he worked a short time for a person in Hatton Garden; but he disliked London extremely, still panting for his native home, to whose braes and bonny banks he joyously returned; where he was occupied in cutting figures and ornaments for books; and now received his first prize from the Society of Arts for [pg 174] the "Old Hound," in an edition of Gay's Fables. A glance at this cut will show what a low state wood-engraving was at, when a public society deemed it worthy a reward; yet even in this are readily visible some lines and touches of the future great master of this delicious art. He never omitted visiting itinerant caravans of animals, from whose living looks and attitudes he made spirited drawings. This led to his History of Quadrupeds, 1790; the first block, however, of which, he cut the very day of his father's death, Nov. 15, 1785. From this work he obtained very considerable celebrity; which led him shortly to draw and engrave the wild bull at Chillingham, Lord Tankerville's, the largest of all his wood-cuts, impressions of which have actually been sold at twenty guineas each; and also the zebra, elephant, lion, and tiger, for Pidcock (Exeter 'Change,) copies whereof are now extremely scarce and valuable. He also executed some curious works on copper, to illustrate a Tour through Lapland, by Matthew Consett, Esq.; and his Quadrupeds having passed through seven editions, his fame was widely and well established. The famous typographer, Bulmer, of the Shakspeare Press (a native of Newcastle,) now employed John Bewick, who, at the age of fourteen, had also been aprenticed to Bielby, in co-operation with his brother Thomas, to embellish a splendid edition of Goldsmith's Deserted Village and Hermit, Parnell's Poems, and Somerville's Chase. The designs and execution of these were so admirable and ingenious, that the late king, George III. doubted their being worked on wood, and requested a sight of the blocks, at which he was equally delighted and astonished. It is deeply to be lamented we have so few specimens of the talents of John Bewick, who died of a pulmonary complaint, 1795, at the early age of thirty-five.

I now, in this hasty, feeble, and divaricated biographical sketch, approach the great and favourite work of my admired friend, The History of British Birds. The first volume of this all-delighting work was published in 1797, jointly by Bielby and Bewick, but was afterwards continued by Bewick. This beautiful, accurate, animated, and (I may really add) wonderful production, having passed through six editions, each of very numerous impressions, is now universally known and admired.

The first time I had personal interview with my venerable friend was at Newcastle upon Tyne, on Wednesday, October 1, 1823, after perambulating the romantic regions of Cumberland and Westmoreland, with my friend, John E. Bowman, Esq., F.L.S. We had been told that he retired from his workbench on evenings to the "Blue Bell on the side," for the purpose of reading the news. To this place we repaired, and readily found ourselves in the presence of the great man. For my part, so warm was my enthusiasm, that I could have rushed into his arms, as into those of a parent or benefactor. He was sitting by the fire in a large elbow-chair, smoking. He received us most kindly, and in a very few minutes we felt as old friends. He appeared a large, athletic man, then in his seventy-first year, with thick, bushy, black hair, retaining his sight so completely as to read aloud rapidly the smallest type of a newspaper. He was dressed in very plain, brown clothes, but of good quality, with large flaps to his waistcoat, grey woollen stockings, and large buckles. In his under-lip he had a prodigious large quid of tobacco, and he leaned on a very thick oaken cudgel, which, I afterwards learned, he cut in the woods of Hawthornden. His broad, bright, and benevolent countenance at one glance, bespoke powerful intellect and unbounded good-will, with a very visible sparkle of merry wit. The discourse at first turned on politics (for the paper was in his hand,) on which he at once openly avowed himself a warm whig, but clearly without the slightest wish to provoke opposition. I at length succeeded in turning the conversation into the fields of natural history, but not till after he had scattered forth a profusion of the most humorous anecdotes, that would baffle the most retentive memory to enumerate, and defy the most witty to depict. I succeeded by mentioning an error in one of his works; for which, when I had convinced him, he thanked me, and took the path in conversation we wished. In many instances, I must remark, though frequently succeeding to the broadest humour, his countenance and conversation assumed the emitted flashes and features of absolutely the highest sublimity; indeed, to an excitement of awful amazement, particularly when speaking on the works of the Deity.

It appears from well authenticated documents, that the mean term of Roman [pg 175] life, among the citizens, was 30 years—that is to say, taking 1,000 persons, adding the years together they each attained, and dividing the total by the number of persons, the result is 30. In England, at the present time, the expectation of life, for persons similarly situated, is at least 50 years, giving a superiority of 20 years above the Roman citizen. The mean term of life among the easy classes at Paris is at present 42. At Florence, to the whole population, it is still not more than 30.

We have gleaned these interesting facts from a review of Dr. Hawkins's Elements of Medical Statistics; and as the subject is like human life itself, of exhaustless interest, we shall proceed with a few more:

In 1780, the annual mortality of England and Wales was 1 in 40. By the last census (of 1821,) the yearly mortality had fallen to 1 in 58, nearly one-third. The rate of mortality is of course not equal throughout the country. According to Dr. Hawkins, this is mainly influenced by the proportion of large towns which any district or county contains. The lowest well-ascertained rate of mortality in any part of Europe is that of Pembrokeshire and Anglesey, in Wales, where only one death takes place annually out of eighty-three individuals. Sussex enjoys the lowest rate of mortality of any English county; it is there 1 in 72. Middlesex, on the other hand, affords the other extreme, 1 in 47; yet here, where the rate of mortality is higher than in any part of England, great improvements in the mean duration of life are taking place; for in 1811, the mortality was as great as 1 in 36. Kent, Surrey, Lancashire, Warwickshire, and Cheshire, are the counties where, next to Middlesex, the deaths are most numerous. The three last named counties enjoy many natural advantages, but these are more than counterbalanced by the number and density of their manufacturing towns. It is a circumstance well worthy of note, that the aguish counties of England do not, as might have been expected, stand high in the list. In Lincolnshire, the rate of mortality is only 1 in 62. Dr. Hawkins hesitates whether to attribute this to the large proportion of dry and elevated district which that county possesses, or to the exemption of fenny countries generally from consumption. We are strongly inclined to suspect that the latter is the true explanation of the fact. The notion was originally thrown out by the late ingenious physician, Dr. Wells, who even went so far as to advise the removal of consumptive patients to the heart of the Cambridgeshire fens, rather than to Hastings or Sidmouth.

The author goes on to remark, "that the decline in the mortality is even more striking in our cities than in our rural districts. While the metropolis has extended itself in all directions, and multiplied its inhabitants to an enormous amount,—in other words, while the seeming sources of its unhealthiness have been largely augmented, it has actually become more friendly to health." In the middle of the last century, the annual mortality was about 1 in 20. By the census of 1821, it appeared as 1 in 40: so that in the space of seventy years, the chances of existence are exactly doubled in London,—a progress and final result, adds the author, without a parallel in the history of any other age or country. The high rate of mortality in London about the year 1750, exceeding considerably that of former years, has been attributed to the great, abuse of spirituous liquors, which were then sold without the very necessary check of high duties. One of the results of these statistical investigations which, a priori, we should least have been prepared for, is the uncommon healthiness of Manchester. The rate of mortality there at the present time does not appear to exceed 1 in 74.

The statistics of the sexes afford some curious results. The relative numbers of the sexes are the same in all parts of the world,—namely, at birth, twenty-one males to twenty females, but as the mortality among males during infancy exceeds that of females, the sexes at the age of fifteen are nearly equal. A late French writer, M. Giron, thinks himself warranted in the opinion, that agricultural pursuits favour an increase in the male, while commerce and manufactures encourage the female population. There exists throughout the world considerable variety in the proportion of births to marriages, but, upon an average, we may state it at about four to one. It has been uniformly found, however, that improvements in the public health are attended by a diminution of marriages and births. The great principle is this: as the number of men cannot exceed their means of subsistence, if men live longer, a less number is born, and the human race is maintained at its due complement with fewer deaths and fewer [pg 176] births, a contingency favourable in every respect to happiness. The author illustrates this very important principle by the population returns both of England and France.

A snapper up of unconsidered trifles.

SHAKSPEARE.

On reading in a provincial paper,3 a passage entitled, "Ornaments of the Bench and Bar."

Imitate no one you despise,

Said one whose mind was great,

Did he not think? despise not him

You cannot imitate.

Major R—— was not long since riding near a building which presented to his admiring gaze a fine specimen of antique Saxon architecture. Desirous to learn something respecting it, he made some inquiries of a man, who as it happened was the souter of the village. This learned wight informed the inquisitive stranger that the building in question was reckoned a noble specimen of Gothic architecture, and was built by the Romans, who came over with Julius Caesar. "Friend," said the Major, "you make anachronisms." "No, no, Sir," replied the man, "indeed I don't make anachronisms, for I never made any thing but shoes in my life."

The same gentleman, one day fitting on a new under-waistcoat, which he had ordered to be made of a material that should resist rain and damp, said to the tailor in attendance, "But are you sure that it is impervious." "O dear, no, Sir," replied the man, with a look of astonishment, "I certainly can't pretend to say that it is impervious, for it is wash-leather."

Some men make a vanity of telling their faults; they are the strangest men in the world; they cannot dissemble; they own it is a folly; they have lost abundance of advantage by it; but if you would give them the world, they cannot help it.

In Paris, small lumps of mixed meats sold in the market for cats, dogs, and the poor, are called Arlequins. They are the relics collected from the plates of the rich, and from the restaurateurs.

By love's delightful influence the attack of ill-humour is resisted; the violence of our passions abated; the bitter cup of affliction sweetened; all the injuries of the world alleviated; and the sweetest flowers plentifully strewed along the path of life.

At the meeting on the Covent Garden stage, the other day, a gentleman inquired for Mr. Kemble: "He's just gone off," replied another, evidently connected with the theatre. Such is the force of habit.

The late Murgravine of Anspach wrote an impromptu charade, and presented it to her husband, Lord C., as the person most interested in the subject of it, and most capable of judging of its truth:—

"Mon premier est un tyran— mari-

Mon second est un monstre— age;

Et mon tout est—le diable— mariage."

A farmer applied to a county magistrate for a warrant:—"A warrant, for what?" says the magistrate, "To take up the weather, please your worship."

N.B. Warrant refused.

Nature hath left every man a capacity of being agreeable, though not of shining in company; and there are a hundred men sufficiently qualified for both, who, by a very few faults, that they might correct in half an hour, are not so much as tolerable.

| s. | d. | |

| Mackenzie's Man of Feeling | 0 | 6 |

| Paul and Virginia | 0 | 6 |

| The Castle of Otranto | 0 | 6 |

| Almoran and Hamet | 0 | 6 |

| Elizabeth, or the Exiles of Siberia | 0 | 6 |

| The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne | 0 | 6 |

| Rasselas | 0 | 8 |

| The Old English Baron | 0 | 8 |

| Goldsmith's Vicar of Wakefield | 0 | 10 |

| Sicilian Romance | 1 | 0 |

| The Man of the World | 1 | 0 |

| A Simple Story | 1 | 4 |

| Joseph Andrews | 1 | 6 |

| Humphry Clinker | 1 | 8 |

| The Romance of the Forest | 1 | 8 |

| The Italian | 2 | 0 |

| Zeluco, by Dr. Moore | 2 | 6 |

| Edward, by Dr. Moore | 2 | 6 |

| Roderick Random | 2 | 6 |

| The Mysteries of Udolpho | 3 | 6 |

| Peregrine Pickle | 4 | 6 |

Footnote 1: (return) Mr Loudon promises an account of these improvements for the next number of his valuable Gardener's Magazine.

Footnote 2: (return) A ruse of this description will be found in the MIRROR, vol. X. page. 305, prefixed to a paper on French Gaming Houses.

Footnote 3: (return) The Manchester Courier, 25th July.

Printed and Published by J. LIMBIRD 143, Strand, (near Somerset House,) London; sold by ERNEST FLEISCHER, 626, New Market, Leipsic; and by all Newsmen and Booksellers.