Title: The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 17, No. 479, March 5, 1831

Author: Various

Release date: November 11, 2004 [eBook #14022]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Jonathan Ingram, David Garcia, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction, Vol. 17, Issue 479, March 5, 1831, by Various

| VOL. XVII, NO. 479.] | SATURDAY, MARCH 5, 1831. | [PRICE 2d. |

Here is another of the resting-places of fallen royalty; and a happy haven has it proved to many a crowned head; a retreat where the plain reproof of flattery—

How can you say to me,—I am a king?

would sound with melancholy sadness and truth.

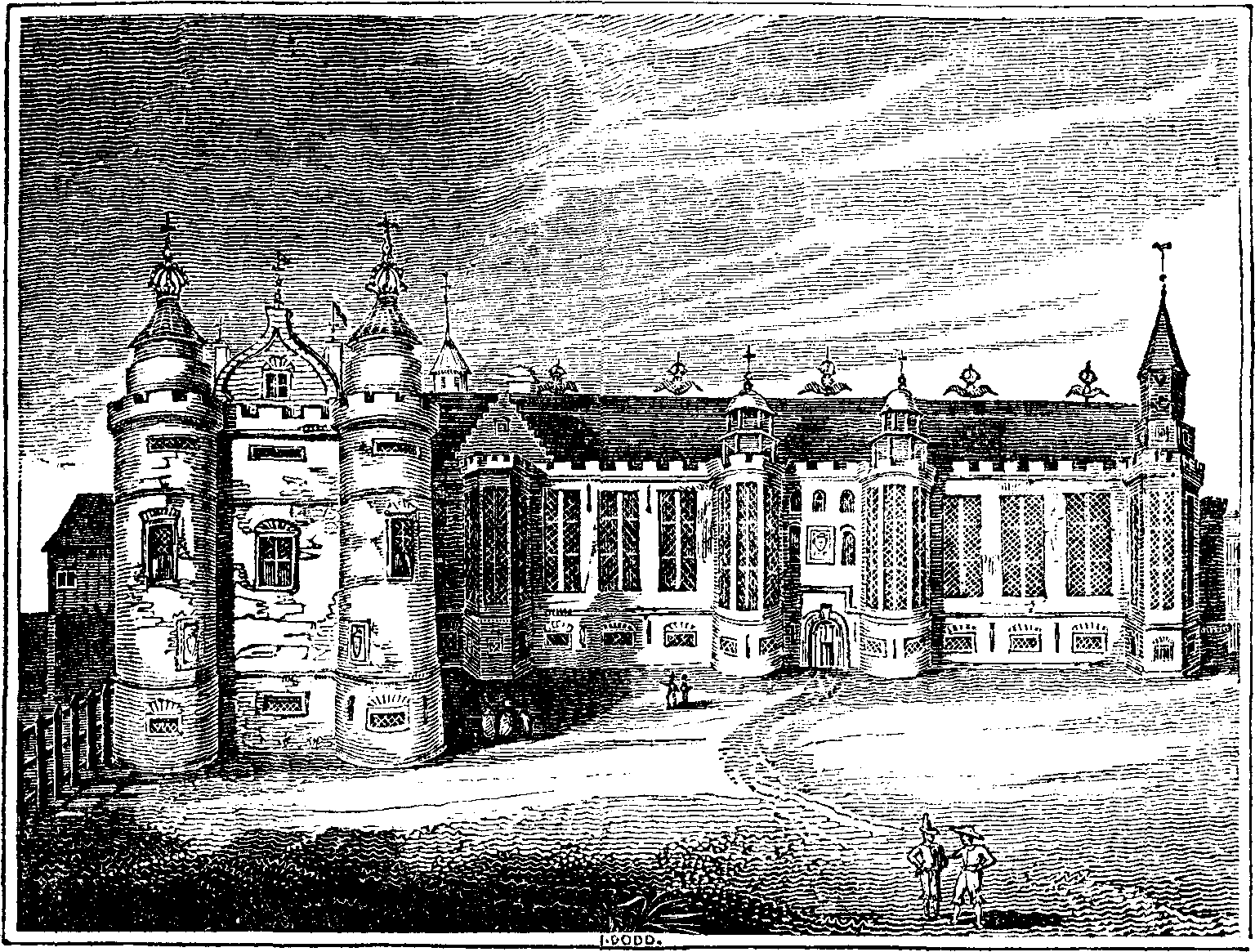

The reader of "the age and body of the time" need not be told that the tenancy of Holyrood by the Ex-King of France has suggested its present introduction, although the Engraving represents the Palace about the year 1640. The structure, in connexion with the Chapel,1 is thus described in Chambers's Picture of Scotland, vol. ii. p. 61.

The Chapel and Palace of Holyrood are situated at the extremity of the suburb called the Cannongate. The ordinary phrase "the Abbey," still popularly applied to both buildings, indicates that the former is the more ancient of the two. Like so many other religious establishments, it owns David I. for its founder. Erected in the twelfth century, and magnificently endowed by that monarch, it continued for about four centuries to flourish as an abbey, and to be, at least during the latter part of that time, the residence of the sovereign. In the year 1528, James V. added a palace to the conventual buildings. During the subsequent reign of Mary, this was the principal seat of the court; and so it continued in a great measure to be, till the departure of King James VI. for England. Previously to this period, the Abbey and Palace had suffered from fire, and they have since undergone such revolutions, that, as in the celebrated case of Sir John Cutler's stockings, which, in the course of darning, changed nearly their whole substance, it is now scarcely possible to distinguish what is really ancient from the modern additions.

As they at present stand, the Palace is a handsome edifice, built in the form of a quadrangle, with a front flanked by double towers, while the Abbey is reduced from its originally extensive dimensions to the mere ruin of the chapel, one corner of which adjoins to a posterior [pg 162] angle of the Palace. Of the palatial structure, the north-west towers alone are old. The walls were certainly erected in the time of James V. They contain the apartments in which Queen Mary resided, and where her minion, Rizzio, fell a sacrifice to the revenge of her brutal husband. A certain portion of the furniture is of the time, and a still smaller portion is said to be the handiwork of that princess. The remaining parts of the structure were erected in the time of Charles II. and have at no time been occupied by any royal personages, other than the Duke of York, Prince Charles Stuart, the Duke of Cumberland, the King of France, (in 1795-9,) and King George IV. in 1822. In the northern side of the quadrangle is a gallery one hundred and fifty feet in length, filled with the portraits of nearly as many imaginary Scottish kings. The south side contains a suite of state apartments, fitted up for the use of the last-mentioned monarch. These various departments of the Palace, as well as the Chapel, are shown to strangers, for a gratuity, by the servants of the Duke of Hamilton, who is hereditary keeper of the Palace. It may be mentioned, before dismissing this subject, that the precincts of these interesting edifices were formerly a sanctuary of criminals, and can yet afford refuge to insolvent debtors.

From the time of the departure of George the Fourth from Edinburgh, in 1822, Holyrood Palace remained without any distinguished inhabitant until last year, when Charles the Tenth, and his suite, took up their abode within its walls. In the same year too, died George IV.

Hark! on yonder blood-trod hill,

The sound of battle lingers still,—

But faint it comes, for every blow

Is feebled with the touch of woe:

Their limbs are weary, and forget

They stand upon the battle plain,—

But still their spirit flashes yet,

And dimly lights their souls again!

Like revellers, flush'd with dead'ning wine,

Measuring the dance with sluggish tread,

Their spirits for an instant shine,

Ashamed to show their pow'r hath fled.

Bat hark! e'en that faint sound hath died,

And sad and solemn up the vale

The silence steals, and far and wide

It tells of death the dreadful tale.

The name of Holborn is derived from an ancient village, built upon the bank of the rivulet, or bourne, of the same name.—Stowe says, "Oldborne, or Hilborne, was the water, breaking out about the place where now the Barres doe stand; and it ranne downe the whole street to Oldborne Bridge, and into the river of the Wels, or Turne-mill Brooke. This Boorne was long since stopped up at the head, and other places, where the same hath broken out; but yet till this day, the said street is there called high, Oldborne hill, and both sides thereof, (together with all the grounds adjoining, that lye betwixt it and the River of Thames,) remaine full of springs, so that water is there found at hand, and hard to be stopped in every house."

"Oldborne Conduit, which stood by Oldborne Crosse, was first builded 1498. Thomasin, widow to John Percival, maior, gave to the second making thereof twenty markes; Richard Shore, ten pounds; Thomas Knesworth, and others also, did give towards it.—But of late, a new conduit was there builded, in place of the old, namely, in the yeere 1577; by William Lambe, sometime a gentleman of the chappell to King Henry the Eighth, and afterwards a citizen and clothworker of London, which amounted to the sum of 1,500l.

"Scroops' Inne,2 sometime Sergeant's Inne, was situate against the church of St. Andrew, in Oldborne, in the city of London, with two gardens.

"On the High-streete of Oldborne (says Stowe) have ye many fair houses builded, and lodgings for gentlemen, innes for travellers, and such like, up almost (for it lacketh but little) to St. Giles's in the Fields."

Gerard, the famous herbalist, lived in Holborn, and had there a large botanic garden. Holborn was then in the outskirts of the town on that side. Richard the Third asked the Bishop of Ely to send for some of the good strawberries which he heard the bishop had in his garden in Holborn.

"In 1417, Lower Holborn (says Brayley) one of the great inlets to the city, was first paved, it being then described as a highway, so deep and miry, that many perils and hazards were thereby occasioned; and the King, at his own expense, is recorded to have [pg 163] employed two vessels, each of twenty tons burthen, for bringing stones for that purpose.

"In 1534 an act was passed for paving with stone the street between Holborn Bridge and Holborn Bars, at the west end thereof, and also the streets of Southwark; and every person was made liable to maintain the pavement before his door, under the forfeiture of sixpence to the king for every square yard."

On the south side of Holborn Hill was St. Andrew's Church, of considerable antiquity; but rebuilt in a plain, neat manner. Here was buried Thomas Wriothesley, lord chancellor in the latter part of the life of Henry the Eighth: a fiery zealot, who (says Pennant) not content with seeing the amiable Anne Askew put to the torture, for no other crime than difference of faith, flung off his gown, degraded the chancellor into the bureau, and with his own hands gave force to the rack.

"Furnival's Inn was one of the hosteries belonging to Lincoln's Inn, in old times the town abode of the Lords of Furnivals.

"Thaive's Inn was another, old as the time of Edward the Third. It took its name from John Tavye.

"Staples Inn; so called from its having been a staple in which the wool-merchants were used to assemble.

"Barnard's Inn, originally Mackworth's Inn, having been given by the executors of John Mackworth, dean of Lincoln, to the dean and chapter of Lincoln, on condition that they should find a pious priest to perform divine service in the cathedral of Lincoln—in which John Mackworth lies interred.

"Hatton Garden was the town house and gardens of the Lord Hatton, founded by Sir Christopher Hatton, lord-keeper in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. The place he built his house on was the orchard and garden belonging to Ely House.

"Brook House was the residence of Sir Fulke Greville, Lord Brooke.

"Southampton Buildings, built on the site of Southampton House, the mansion of the Wriothesleys, earls of Southampton. When Lord Russel passed by this house, on his way to execution, he felt a momentary bitterness of death, in recollecting the happy moments of the place. He looked (says Pennant) towards Southampton House, the tear started into his eye, but he instantly wiped it away.

"Gray's Inn is a place of great antiquity: it was originally the residence of the Lord Grays, from the year 1315, when John, the son of Reginold de Grey, resided here, till the latter end of the reign of Henry the Seventh, when it was sold, by Edmund Lord Grey, of Wilton, to Hugh Dennys, Esq., by the name of Portpole; and in eight years afterwards it was disposed of to the prior and convent of Shene, who again, disposed of it to the students of the law; not but that they were seated here much earlier, it appearing that they had leased a residence here from the Lord Grays, as early as the reign of Edward the Third. Chancery Lane gapes on the opposite side, to receive the numberless malheureuses who plunge unwarily on the rocks and shelves with which it abounds."

"O Freedom! first delight of human kind."

DRYDEN.

Sharon Turner, in his interesting "History of the Anglo-Saxons," says, "It was then (during the reign of Pope Gregory I.) the practice of Europe to make use of slaves, and to buy and sell them; and this traffic was carried on, even in the western capital of the Christian Church. Passing through the market at Rome, the white skins, the flowing locks, and beautiful countenances of some youths who were standing there for sale, interested Gregory's sensibility. To his inquiries from what country they had been brought, the answer was, from Britain, whose inhabitants were all of that fair complexion. Were they Pagans or Christians? was his next question: a proof not only of his ignorance of the state of England, but also, that up to that time it had occupied no part of his attention; but thus brought as it were to a personal knowledge of it by these few representatives of its inhabitants, he exclaimed, on hearing that they were still idolaters, with a deep sigh, 'What a pity that such a beauteous frontispiece should possess a mind so void of internal grace.' The name of their nation being mentioned to be Angles, his ear caught the verbal coincidence—the benevolent wish for their improvement darted into his mind, and he expressed his own feelings, and excited those of his auditors, by remarking—'It suits them well: they have angel faces, and ought to be the co-heirs of the angels in heaven.'

"The different classes of society among the Anglo-Saxons were such as belonged to birth, office, or property, and such as were occupied by a freeman, [pg 164] a freedman, or one of the servile description. It is to be lamented in the review of these different classes, that a large proportion of the Anglo-Saxon population was in a state of abject slavery: they were bought and sold with land, and were conveyed in the grants of it promiscuously with the cattle and other property upon it; and in the Anglo-Saxon wills, these wretched beings were given away precisely as we now dispose of our plate, our furniture, or our money. At length the custom of manumission, and the diffusion of Christianity, ameliorated the condition of the Anglo-Saxon slaves. Sometimes individuals, from benevolence, gave their slaves their freedom—sometimes piety procured a manumission. But the most interesting kind of emancipation appears in those writings which announce to us, that the slaves had purchased their own liberty, or that of their family. The Anglo-Saxon laws recognised the liberation of slaves, and placed them under legal protection. The liberal feelings of our ancestors to their enslaved domestics are not only evidenced in the frequent manumissions, but also in the generous gifts which they appear to have made them. The grants of lands from masters to their servants were very common; gilds, or social confederations, were established. The tradesmen of the Anglo-Saxons were, for the most part, men in a servile state; but, by degrees, the manumission of slaves increased the number of the independent part of the lower orders."

When the statute 1st. Edward VI. c. 3. was made, which ordained, that all idle vagabonds should be made slaves, and fed upon bread, water or small drink, and refuse of meat; should wear a ring round their necks, arms, or legs; and should be compelled, by beating, chaining, or otherwise, to perform the work assigned them, were it ever so vile;—the spirit of the nation could not brook this condition, even in the most abandoned rogues; and therefore this statute was repealed in two years afterwards, 3rd and 4th of Edward VI. c. 16.

Fitzstephen, in his Description of London, 1282, gives the following account of skating in Moor, or Finsbury Fields, which may afford amusement to the inquisitive reader:—

"When that vast lake which waters the walls of the city towards the north is hard frozen, the youths, in great numbers, go to divert themselves on the ice—some, taking a small run for an increment of velocity, place their feet at a proper distance, and are carried sideways a great way; others will make a large cake of ice, and seating one of their companions upon it, they take hold of one's hands, and draw him along, when it happens that moving swiftly on so slippery a plane, they all fall headlong; others there are who are still more expert in these amusements on the ice—they place certain bones (the leg-bones of animals) under the soles of their feet, by tying them round their ankles, and then taking a pole, shod with iron, with their hands they push themselves forward by striking it against the ice, and are carried on with a velocity equal to the flight of a bird, or a bolt discharged from a cross-bow."

This tract affords the earliest description of London; and Dr. Pegge, in his preface to said Description, says, "I conceive we may challenge any nation in Europe to produce an account of its capital, or any other of its great cities, at so remote a period as the 12th century."

No. 65 of Constable's Miscellany, just published, consists of A Journal of a Residence in Normandy, by J.A. St. John, Esq. This volume falls in opportunely enough for the further description of Mount St. Michael, engraved in No. 477 of The Mirror.

Breakfasting in haste, I procured a horse and a guide, and set out for the mount, no less celebrated for its historical importance, than for the peculiarity of its position. As soon as I had emerged from the streets of Avranches, I saw before me a vast bay, now entirely deserted by the tide, and consisting partly of sand, partly of slime, intersected by the waters of several rivers, and covered, during spring tides, at high water.—Two promontories, the one bluff and rocky, the other sandy and low, project, one on either hand, into the sea; and in the open space between these two points are two small islands, from around which the sea ebbs at low water: one of them is a desert rock, called the Tombelaine, and the other the Mont St. Michel.3 The space thus covered and deserted alternately by the sea is about eight square leagues, and is here called the Grève.

The Mont St. Michel, which is about the same height as the Great Pyramid of Egypt, and now stood, as that does, upon a vast plain of sand, which is here, however, skirted in its whole length by the sea, has a very striking and extraordinary aspect. It appeared, as the water was so close behind it, to rise out of the sea, upon the intense and dazzling blue of which its grey rocks and towers were relieved in a sharp and startling manner; and, as I descended lower and lower on the hill-side, and drew near the beach, its pinnacles seemed to increase in height, and the picturesque effect was improved.

At length I emerged from the shady road upon the naked beach, and saw the ferry-boat and the Charon that were to convey me and my charger over the first river. My Avranches guide here quitted me; but I had been told that the ferryman himself usually supplied his place in piloting strangers across the quicksands, which, owing to the shifting of the course of the rivers, are in constant change, and of the most dangerous character. Horses and their riders, venturing to select their own path over the sands, have been swallowed up together, and vessels, stranded here in a tempest, have in a short time sunk and disappeared entirely. The depth of what may perhaps be termed the unsolid soil, is hitherto unknown, though various attempts have been made to ascertain it. In one instance, a small mast, forty feet high, was fixed up in the sands, with a piece of granite of considerable weight upon the top of it; but mast, granite, and all, rapidly disappeared, leaving no trace behind. It is across several leagues of a beach of this nature that one has to approach the Mont St. Michel.

The scene which now presented itself was singular and beautiful. On the right the land, running out boldly into the sea, offered, with its rich verdure, a striking contrast to the pale yellow sands beneath. In front, the sea, blue, calm, waveless, and studded in the distance with a few white sails, glittering in the sun, ran in a straight line along the yellow plain, which was, moreover, intersected in various directions by numerous small rivers, whose shining waters looked like molten silver. To add to the effect of the landscape, silence the most absolute brooded over it, except when the scream of a seamew, wheeling about drowsily in the sunny air, broke upon the ear. The mount itself, with its ancient monastic towers, rearing their grey pinnacles towards heaven, in the midst of stillness and solitude, appeared to be formed by nature to be the abode of peace, and a soft and religious melancholy.

For some time I rode on musing, gazing delightedly at the scene, and recalling to mind the historical events which had taken place on those shores, and rendered them famous. The cannon of England had thundered on every side, and her banners had waved triumphantly from the towers before me. My reflections, however, were soon called off from these towering topics, being interrupted by the loud laugh of a party of soldiers and wagoners, who were regaling themselves with fresh air at the gate of the fortress.

Dismounting here, I entered the small town which clusters round the foot of the mount within the wall; and whatever romance might have taken lodging in my imagination, was quickly put to flight by the stink, and filth, and misery, which forced themselves upon my attention. I never beheld a more odious den. Leaving my horse and guide at a cabaret, I ascended the only street in the place, which winding about the foot of the mountain, leads directly to the castle. Toiling up this abominable street, and several long and very steep flights of steps, I at length reached the door, where, having rung, and waited for some time, I was admitted by a saucy gendarme, who demanded my business and my passport in the most insolent tone imaginable. I delivered up my passport; and while the rascal went to show it to the man in office—governor, sub-governor, or some creature of that sort—had to stand in the dismal passage, among a score or two of soldiers. In general, however, French soldiers are remarkably polite, and these, with the exception of the above individual, were so also. Even he, when he returned, had changed his tone; for, having learned from his superior that I was an Englishman, he came, with cap in hand, to conduct me round the building.

The first apartment, after the chapel, which is small, and by no means striking, into which I was led, was the ancient refectory, where there were some hundreds of criminals, condemned for several years to close imprisonment, or the galleys, weaving calico. I never in my life saw so many demoniacal faces together.

The apartment in which these miscreants were assembled, was a hall about one hundred feet long, by thirty-five or [pg 166] forty in breadth, and was adorned with two rows of massy, antique pillars, resembling those which we find in Gothic churches. From hence we proceeded to the subterranean chapel, where are seen those prodigious columns upon which the weight of the whole building reposes. The scanty light, which glimmers among these enormous shafts, is just sufficient to discover their magnitude to the eye, and to enable one to find his way among them. Having crossed this chapel, we entered the quadrangular court, around which the cloisters, supported by small, graceful pillars, of the most delicate workmanship, extend. Here the monks used to walk in bad weather, contriving the next day's dinner, or imagining excuses for detaining some of the many pretty female pilgrims who resorted, under various pretences, to this celebrated monastery. At present, it affords shelter to the veterans and gendarmes who keep guard over the prisoners below.

From various portions of the monastery, we obtain admirable views of sea and shore; but the most superb coup-d'oeil is from a tall slender tower, which shoots up above almost every other portion of the building. Hence are seen the hills and coasts of Brittany, the sea, the sandy plain stretching inland, with the rivers meandering through it, and the long sweep of shore which encompasses the Grève, with Avranches, and its groves and gardens, in the back ground. Close at hand, and almost beneath one's feet, as it were, is the barren rock called the Tombelaine, which, though somewhat larger than the Mont St. Michel, is not inhabited. Even this rock, however, was formerly fortified by the English; and several remains of the old towers are still found among the thorns and briers with which it is at present overrun. Several fanciful derivations of the word Tombelaine are given by antiquaries, some imagining it to have been formed of the words Tumba Beleni, or Tumba Helenae; and in support of the latter etymology, the following legend is told:—Helen, daughter of Hoël, King of Brittany, was taken away, by fraud or violence, from her father's court, by a certain Spaniard, who, having conducted her to this island, and compelled her to submit to his desires, seems to have deserted her there. The princess, overwhelmed with misfortune, pined away and died, and was buried by her nurse, who had accompanied her from Brittany.

At the Mont St. Michel was preserved, until lately, the enormous wooden cage in which state prisoners were sometimes confined under the old regime.

The most unfortunate of the poor wretches who inhabited this cage was Dubourg, a Dutch editor of a newspaper. This man having, in the exercise of his duty, written something which offended the majesty of Louis XIV., or some one of his mistresses, was marked out by the magnanimous monarch for vengeance; and the means which, according to tradition, he employed to effect his purpose, was every way worthy of the royal miscreant. A villain was sent from Avranches to Holland, a neutral state, with instructions to worm himself into the friendship and confidence of Dubourg, and, in an unguarded moment, to lead him into the French territories, where a party of soldiers was kept perpetually in readiness to kidnap him and carry him off. For two years this modern Judas is said to have carried on the intrigue, at the end of which period he prevailed upon Dubourg to accompany him on a visit into France, when the soldiers seized upon their victim, and hurried him off to the Mont St. Michel.

Confinement and solitude do not always kill. The Dutchman, accustomed, perhaps, to a life of indolence, existed twenty years in his cage, never enjoying the satisfaction of beholding "the human face divine," or of hearing the human voice, except when the individual entered who was charged with the duty of bringing him his provisions and cleaning his cell. Some faint rays of light, just such as enable cats and owls to mouse, found their way into the dungeon; and, by their aid, Dubourg, whom accident or the humanity of his keeper had put in possession of an old nail, and who inherited the passion of his countrymen for flowers, contrived to sculpture roses and other flowers upon the beams of his cage. Continual inaction, however, though it could not destroy life, brought on the gout, which rendered the poor wretch incapable of moving himself about from one side of the cage to the other; and he observed to his keeper, that the greatest misery he endured was inflicted by the rats, which came in droves, and gnawed away at his gouty legs, without his being able to move out of their reach or frighten them away.

Having examined the principal objects of curiosity at the mount, and learning that the tide was rising rapidly on the Grève, I descended from the fortress, and mounting my horse, set out on my return to Avranches.

My guide informed me that I had staid somewhat too long, and in fact, the sea, flowing and foaming furiously over the vast plain of sand, quickly surrounded the mount, and was at our heels in a twinkling. However, the guide sprang off with that long trot peculiar to fishermen, and was followed with great good will by the beast which had been so obstinate in the morning. We were joined in our retreat by a party of sportsmen, who appeared to have been shooting gulls upon the sands; but they could not keep up with the young fisherman, who stepped out like a Newmarket racer, and in a short time landed me safe at the Point of Pontorson, near the village of Courtils, where he resided.

By the way, we have just received Mr. St. John's Anatomy of Society, which we hope to notice in our next or subsequent number.

Once the object of general praise, from its loftiness and beauty, and till now the subject of censure, even among Protestants, from that inscription of which the Papists always complained, was the offspring of this period, and realized one of those decorations which Wren had lavished upon his air-drawn Babylon. This lofty column was ordered by the Commons, in commemoration of the extinction of the great fire and the rebuilding of the city: it stands on the site of the old church of St. Margaret, and within a hundred feet of the spot where the conflagration began. It is of the Doric order, and rises from the pavement to the height of two hundred and two feet, containing within its shaft a spiral stair of black marble of three hundred and forty-five steps. The plinth is twenty-one feet square, and ornamented with sculpture by Cibber, representing the flames subsiding on the appearance of King Charles;—beneath his horse's feet a figure, meant to personify religious malice, crawls out vomiting fire, and above is that unjustifiable legend which called forth the indignant lines of Pope—

"Where London's column pointing to the skies,

Like a tall bully, lifts his head and lies."4

The shaft, deeply fluted, measures fifteen feet diameter at the base, and diminishing according to the proportion of its order, terminates in a capital, crowned with a balcony, from the centre of which rises a circular pedestal, bearing a flaming urn of gilt bronze. The various notions of the architect concerning a suitable termination, are worth relating:—"I cannot," said he, "but commend a large statue as carrying much dignity with it, and that which would be more valuable in the eyes of foreigners and strangers. It hath been proposed to cast such a one in brass of twelve feet high for a thousand pounds. I hope we may find those who will cast a figure for that money of fifteen feet high, which will suit the greatness of the pillar, and is, as I take it, the largest at this day extant. And this would undoubtedly be the noblest finishing that can be found answerable to so goodly a work in all men's judgments." The King preferred a large ball of metal gilt. A phoenix was introduced in the wooden model of the pillar, but afterwards rejected by the architect himself, "because it would be costly, not easily understood at that height, and worse understood at a distance; and lastly, dangerous by reason of the sail the spread wings would carry in the wind." A statue of Charles, fifteen feet high, on a pedestal of two hundred, would have looked small and mean; the King resisted the compliment. This work, begun in 1671, was not completed till 1677; stone was scarce, and the restoration of London and its Cathedral swallowed up the produce of the quarries. "It was at first used," says Elmes, "by the members of the Royal Society, for astronomical experiments, but was abandoned on account of its vibrations being too great for the nicety required in their observations. This occasioned a report that it was unsafe; but its scientific construction may bid defiance to the attacks of all but earthquakes for centuries."

H. Morland, wine merchant, brother of the painter, says, "that his brother died while his servant was holding a glass of gin (his favourite liquor) over his shoulder. And he was so prodigal at times that he had not enough to buy ultra-marine with, although a few hours before he had invited a great number of his associates to a general debauch."

Cowley retired to these premises at Chertsey, in Surrey, a few years before his death, which took place here in 1667, in his 49th year. The premises are called the Porch House, and were for many years occupied by the late Richard Clark, Esq., Chamberlain of London, who died a short time since. Mr. Clark, in honour of the Poet, took much pains to preserve the premises in their original state, kept an original portrait of Cowley, and had affixed a tablet in front, containing Cowley's Latin Epitaph on himself. In the year 1793, it was supposed that the ruinous state of the house rendered it impossible to support the building, but it was found practicable to preserve the greater part of it, to which some rooms have been added. Mr. Clark also placed a tablet in front of the building where the porch stood, with the following inscription:—"The Porch of this House, which projected ten feet into the highway, was, in the year 1792, removed for the safety and accommodation of the public.

"Here the last accents flowed from Cowley's tongue."

We received the substance of this information from the venerable Mr. Clark himself, in the year 1822, about which time there appeared, in the Monthly Magazine, a view of the original premises, from a drawing by the late Mr. Samuel Ireland. The above view was taken by a Correspondent, in the summer of 1828, and represents the original portion of the mansion. Cowley's study is here pointed out, being a closet in the back part of the house, towards the garden.

How delightfully must COWLEY have passed his latter days in the rural seclusion of Chertsey! How he must have loved that earthly paradise—his garden—who could write thus for his epitaph:

From life's superfluous cares enlarg'd,

His debt of human toil discharg'd,

Here COWLEY lies, beneath this shed,

To ev'ry worldly interest dead;

With decent poverty content;

His hours of ease not idly spent;

To fortune's goods a foe profess'd,

And, hating wealth, by all caress'd

'Tis sure he's dead; for, lo! how small

A spot of earth is now his all!

O! wish that earth may lightly lay,

And ev'ry care be far away!

Bring flow'rs, the short-liv'd roses bring,

To life deceased fit offering!

And sweets around the poet strow,

Whilst yet with life his ashes glow.

Again:

Sweet shades, adieu! here let my dust remain,

Covered with flowers, and free from noise and pain;

Let evergreens the turfy tomb adorn,

And roseate dews (the glory of the morn)

My carpet deck; then let my soul possess

The happier scenes of an eternal bliss.

Then, too, the delightful chapter Of Gardens which he addressed to the virtuous John Evelyn.

We quote these few illustrations of Cowley's character from Mr. Felton's very interesting volume "on the Portraits of English Authors on Gardening."—By the way, at page 100, in a Note, Mr. Felton makes a flattering reference to one of our earliest works, which we are happy to learn has not escaped his observation.

The idea of the character of Paul Pry was suggested by the following anecdote, related to me several years ago, by a beloved friend:—An idle old lady, living in a narrow street, had passed so much of her time in watching the affairs of her neighbours, that she, at length, acquired the power of distinguishing the sound of every knocker within hearing. It happened that she fell ill, and was, for several days, confined to her bed. Unable to observe in person what was going on without, she stationed her maid at the window, as a substitute for the performance of that duty. But Betty soon grew weary of the occupation: she became careless in her reports—impatient and tetchy when reprimanded for her negligence.

"Betty, what are you thinking about? don't you hear a double knock at No. 9? Who is it?"

"The first-floor lodger, Ma'am."

"Betty! Betty!—I declare I must give you warning. Why don't you tell me what that knock is at No. 54!"

"Why, Lord! Ma'am, it is only the baker, with pies."

"Pies, Betty! what can they want with pies at 54?—they had pies yesterday!"

Of this very point I have availed myself. Let me add that Paul Pry was never intended as the representative of any one individual, but a class. Like the melancholy of Jaques, he is "compounded of many Simples;" and I could mention five or six who were unconscious contributors to the character.—That it should have been so often, though erroneously, supposed to have been drawn after some particular person, is, perhaps, complimentary to the general truth of the delineation.

With respect to the play, generally, I may say that it is original: it is original in structure, plot, character, and dialogue—such as they are. The only imitation I am aware of is to be found in part of the business in which Mrs. Subtle is engaged: whilst writing those scenes I had strongly in my recollection Le Vieux Celibataire. But even the little I have adopted is considerably altered and modified by the necessity of adapting it to the exigencies of a different plot.—New Monthly Magazine.

The cottage is here as of old I remember,

The pathway is worn as it always hath been;

On the turf-piled hearth there still lives a bright ember;—

But where is Maureen?

The same pleasant prospect still lieth before me,

The river—the mountain—the valley of green,

And Heaven itself (a bright blessing!) is o'er me;—

But where is Maureen?

Lost! Lost!—Like a dream that hath come and departed,

(Ah, why are the loved and the lost ever seen!)

She has fallen—hath flown, with a lover false-hearted;—

So, mourn for Maureen.

And she who so loved her is slain—(the poor mother!)

Struck dead in a day by a shadow unseen,

And the home we once loved is the home of another,

And lost is Maureen.

Sweet Shannon, a moment by thee let me ponder,

A moment look back at the things that have been,

Then, away to the world where the ruin'd ones wander,

To seek for Maureen.

Pale peasant—perhaps, 'neath the frown of high Heaven,

She roams the dark deserts of sorrow unseen,

Unpitied—unknown; but I—I shall know even

The ghost of Maureen.

How weeps yon gallant Band

O'er him their valour could not save!

For the bayonet is red with gore,

And he, the beautiful and brave,

Now sleeps in Egypt's sand.—WILSON.

In the shadow of the Pyramid

Our brother's grave we made,

When the battle-day was done,

And the Desert's parting sun

A field of death survey'd.

The blood-red sky above us

Was darkening into night,

And the Arab watching silently

Our sad and hurried rite.

The voice of Egypt's river

Came hollow and profound,

And one lone palm-tree, where we stood,

Rock'd with a shivery sound:

While the shadow of the Pyramid

Hung o'er the grave we made,

When the battle-day was done,

And the Desert's parting sun

A field of death survey'd.

The fathers of our brother

Were borne to knightly tombs,

With torch-light and with anthem-note,

And many waving plumes:

But he, the last and noblest

Of that high Norman race,

With a few brief words of soldier-love

Was gather'd to his place;

In the shadow of the Pyramid,

Where his youthful form we laid,

When the battle-day was done,

And the Desert's parting sun

A field of death survey'd.

But let him, let him slumber

By the old Egyptian wave!

It is well with those who bear their fame

Unsullied to the grave!

When brightest names are breathed on,

When loftiest fall so fast,

We would not call our brother back

On dark days to be cast,

From the shadow of the Pyramid,

Where his noble heart we laid,

When the battle-day was done,

And the Desert's parting sun

A field of death survey'd.

Her life seemed to be the same in sleep. Often at midnight, by the light of the moon shining in upon her little bed beside theirs, her parents leant over her face, diviner in dreams, and wept as she wept, her lips all the while murmuring, in broken sentences of prayer, the name of Him who died for us all. But plenteous as were his penitential tears—penitential, in the holy humbleness of her stainless spirit, over thoughts that had never left a dimming breath on its purity, yet that seemed, in those strange visitings, to be haunting her as the shadows of sins—soon were they all dried up in the lustre of her returning smiles! Waking, her voice in the kirk was the sweetest among many sweet, as all the young singers, and she the youngest far, sat together by themselves, and within the congregational music of the psalm, uplifted a silvery strain that sounded like the very spirit of the whole, even like angelic harmony blent with a mortal song. But sleeping, still more sweetly sang the "Holy Child;" and then, too, in some diviner inspiration than ever was granted to it while awake, her soul composed its own hymns, and set the simple scriptural words to its own mysterious music—the tunes she loved best gliding into one another, without once ever marring the melody, with pathetic touches interposed never heard before, and never more, to be renewed! For each dream had its own breathing, and many-visioned did then seem to be the sinless creature's sleep!

The love that was borne for her, all over the hill-region and beyond its circling clouds, was almost such as mortal creatures might be thought to feel for some existence that had visibly come from heaven! Yet all who looked on her saw that she, like themselves, was mortal; and many an eye was wet, the heart wist not why, to hear such wisdom falling from her lips; for dimly did it prognosticate, that as short as bright would be her walk from the cradle to the grave. And thus for the "Holy Child" was their love elevated by awe, and saddened by pity—and as by herself she passed pensively by their dwellings, the same eyes that smiled on her presence, on her disappearance wept!

Not in vain for others—and for herself, oh! what great gain!—for these few years on earth, did that pure spirit ponder on the word of God! Other children became pious from their delight in her piety—-for she was simple as the simplest among them all, and walked with them hand in hand, nor spurned companionship with any one that was good. But all grew good by being with her—-and parents had but to whisper her name—and in a moment the passionate sob was hushed—-the lowering brow lighted—and the household in peace. Older hearts owned the power of the piety, so far surpassing their thoughts; and time-hardened sinners, it is said, when looking and listening to the "Holy Child," knew the errors of their ways, and returned to the right path, as at a voice from heaven.

Bright was her seventh summer—the brightest, so the aged said, that had ever, in man's memory, shone over Scotland. One long, still, sunny, blue day followed another; and in the rainless weather, though the dews kept green the hills, the song of the streams was low. But paler and paler, in sunlight and moonlight, became the sweet face that had been always pale; and the voice that had been always something mournful, breathed lower and sadder still from the too perfect whiteness of her breast. No need—no fear—-to tell her thai she was about to die! Sweet whispers had sung it to her in her sleep, and waking she knew it in the look of the piteous skies. But she spoke not to her parents of death more than she had often done—and never of her own. Only she seemed to love them with a more exceeding love—and was readier, even sometimes when no one was speaking, with a few drops of tears. Sometimes she disappeared—nor, when sought for, was found in the woods about the hut. And one day that mystery was cleared; for a shepherd saw her sitting by herself on a grassy mound in a nook of the small, solitary kirkyard, miles off among the hills, so lost in reading the Bible, that shadow or sound of his feet awoke her not; and, ignorant of his presence, she knelt down and prayed—for awhile weeping bitterly—but soon comforted by a heavenly calm—that her sins might be forgiven her!

One Sabbath evening, soon after, as she was sitting beside her parents, at the door of their hut, looking first for a long while on their faces, and then for a long while on the sky, though it was not yet the stated hour of worship, she suddenly knelt down, and leaning on their knees, with hands clasped more fervently than her wont, she broke forth into tremulous singing of that hymn, which from her lips they now never heard without unendurable tears.

"The hour of my departure's come,

I hear the voice that calls me home;

At last, O Lord! let trouble cease,

And let thy servant die in peace."

They carried her fainting to her little bed, and uttered not a word to one another till she revived. The shock was sudden, but not unexpected, and they knew now that the hand of death was upon her, although her eyes soon became brighter and brighter, they thought, than they had ever been before. But forehead, cheeks, lips, neck, and breast, were, all as white, and, to the quivering hands that touched them, almost as cold, as snow. Ineffable was the bliss in those radiant eyes; but the breath of words was frozen, and that hymn was almost her last farewell. Some few words she spake, and named the hour and day she wished to be buried. Her lips could then just faintly return the kiss, and no more—a film came over the now dim blue of her eyes—the father listened for her breath—and then the mother took his place, and leaned her ear to the unbreathing mouth, long deluding herself with its lifelike smile; but a sudden darkness in the room, and a sudden stillness—most dreadful both—convinced their unbelieving hearts at last—that it was death!

All the parish, it may be said, attended her funeral—for none staid away from the kirk that Sabbath—though many a voice was unable to join in the psalm. The little grave was soon filled up, and you hardly knew that the turf had been disturbed beneath which she lay. The afternoon service consisted but of a prayer—for he who ministered, had loved her with love unspeakable—and, though an old grey-haired man, all the time he prayed he wept. In the sobbing kirk her parents were sitting, but no one looked at them—and when the congregation rose to go, there they remained sitting—and an hour afterwards, came out again into the open air—and parting with their pastor at the gate, walked away to their hut, overshadowed with the blessing of a thousand prayers!

And did her parents, soon after she was buried, die of broken hearts, or pine away disconsolately to their graves?—Think not that they, who were Christians indeed, could be guilty of such ingratitude. "The Lord giveth, and the Lord taketh away—blessed be the name of the Lord!" were the first words they had spoken by that bedside; during many, many long years of weal or woe, duly every morning and night, these same blessed words did they utter when on their knees together in prayer—and many a thousand times besides, when they were apart, she in her silent hut, and he on the hill—neither of them unhappy in their solitude, though never again, perhaps, was his countenance so cheerful as of yore—and though often suddenly amidst mirth or sunshine, her eyes were seen to overflow! Happy had they been—as we mortal beings ever can be happy—during many pleasant years of wedded life before she had been born. And happy were they—on to the verge of old age—after she had here ceased to be! Their Bible had indeed been an idle book—the Bible that belonged to "the Holy Child,"—and idle all their kirk-goings with "the Holy Child," through the Sabbath-calm—had those intermediate seven years not left a power of bliss behind them triumphant over death and the grave!

We cordially add our note of commendation to those already bestowed on a little Manual, entitled "Plain Advice to Landlords and Tenants, Lodging-house Keepers, and Lodgers; with a comprehensive Summary of the Law of Distress," &c. It is likewise pleasant to see "third edition" in its title-page. Accompanying we have "A Familiar Summary of the Laws respecting Masters and Servants," &c.

On looking into these little books we find much of the plain sense of law. There is no mystification by technicalities, but all the information is practical, all ready to hand, we mean mouth; so that, as Mrs. Fixture says in the farce of A Roland for an Oliver—"If there be such a thing as la' in the land," you may "ha' it." Joking apart, they are sensible books, and of good authority.

Suppose we throw ourselves back in our chair, and for a minute or two think of the good which the spread of common sense by such means as the [pg 172] above must produce among men: how much bile and bickering they may keep down, which in nine law-suits out of ten arise from want of "a proper understanding." The reader may say that in recommending those fire-and-water folks, landlords and tenants, and masters and servants, and those half-agreeable persons, lodging-house keepers and lodgers—to purchase such books, we advise every man to act with an attorney at his elbow. We can but reply with Swift:—

"The only fault is with mankind."

A very laudable work appears quarterly, entitled "The Voice of Humanity: for the communication and discussion of all subjects relative to the conduct of man towards the inferior animal creation." The number (3) before us, contains a paper on the Abolition of Slaughter-houses, and the substitution of Abattoirs, a point to which we adverted and illustrated in vol. xi. of the Mirror. The Amended Act to prevent the cruel and improper treatment of cattle, follows; and among the other articles is a Table of the Prosecutions of the Society against Cruelty to Animals, from November 1830, to January 1831, drawn up by our occasional correspondent, the benevolent Mr. Lewis Gompertz.

We have been somewhat amused with the piquancy and humour of the following introduction of a Notice of a volume of Poems, "by John Jones, an old servant," which has just appeared under the editorship of Mr. Southey and the Quarterly Review:—

Shakspeare has said, "What's in a name?—a rose, by any other name, would smell as sweet!" But here we have a convincing proof of the necessity of attending strictly to names, as the commonest regard to the fitting attributes of a "John Jones," would have kept the victim of such an appellation quite clear of poetry. It is next to impossible that a John Jones should be a poet;—and some kind friend should have broken the truth to the butler, before he endeavoured to share unpolished glory with uneducated bards.

An inspired serving-man, in a livery of industry, turned up with morality, is a species of bard which we never expected to find in the service of the Muses, or bringing a written character from his last place, and vaunting of his readiness and ability to write epics and wait at table. The work we should have looked to meet with, emanating from the butler's pantry, was a miscellaneous volume full of religious scraps, essays on dress, receipts for boot-tops, wise cooking cogitations, remedies for bugs, cures for ropy beer, hints for blacking, ingredients for punch, thoughts on tapping ale, early rising and killing fleas. The mischief of the wide dissemination of education is now becoming apparent, for, poor as authors confessedly are, they have generally been gentlemen, even in rags—learned men of some degree, though with exposed elbows—folk only a little lower than the angels! But never until the schoolmaster was so abundantly abroad, distributing his spelling-soup to the poor, did we ever hear of a butler writing poetry, and committing it to the press. The order of things is becoming reversed. The garret is beginning to lose its literary celebrity, and the kitchen is taking the matter up. A floor near the sky in Grub-street is no pen-spot now; but down fifty fathoms deep in Portland Place, or Portman Square, or some far-retired old country house, you shall find the author: his red cuffs turned up over his light blue jacket sleeves, the pen in his hand, and his inspired eye looking out upon the area. There doth he correct the brain-work which is to carry his name up above the earth, and keep it there, bright as cleaned plate. In the housekeeper's room, inspiration gives a double knock at his heart. An author in a pantry certainly writes under great disadvantages, for it cannot be said that he is there writing for his bread. In such a place, the loaf is in his eye—the larder is so near, he may almost dip his pen into it by mistake—and positive beef gleams through the veil of the safe, softened to his eye, yet still solider than beef of the imagination. In truth, a man has much to overcome in preparing food for the mind, in the very thick of food for the body;—for a good authority (no less a man than Mr. Bayes) has strenuously advised that the belly should be empty when the brain is to be unloaded. How can a gentleman's gentleman, with a corpus that banishes his backbone nearly four feet from the table at which he sits, betake himself to his cogitations over a tankard of October, and expect to beat your true thin garret-haunting devil, with an inside like a pea-shooter, who can scarcely be said to be one remove from the ethereal, and who writes from that best of inspirations—an empty pantry? We shall presently see whether an author from below is better [pg 173] than one from above—whether it will be more eligible that the Muses should have several more stories to descend, when their nine ladyships are invoked so to do—and that the pen should be taken out of the scraggy hand of a gentleman in rags, and be placed in the plump gripe of a gentleman in tags.

Before we proceed to give an account of the book before us, we must yet take leave to indulge in a few reflections on the effect of this mental explosion in the noddles of John and James and Richard, upon reviewers, publishers, and the world in general. This change of lodging in the author will turn many things topsy-turvy, and conjure the spirit out of much long-established facetiousness. Pictures of poets in garrets will soon not be understood; bathos will be at a premium! the bard will be known, not by the brownness of his beaver, but by the gold band that encircles it. The historian shall go about in black plush breeches; and the great inspired writers of the age "have a livery more guarded than their fellows." Authors shall soon be, indeed, even more easily known by their dress. How often, too, shall we see Mr. Murray or Mr. Colburn descending "with the nine" to the hireling scribe, who is correcting the press and locking up the tea-spoons, against his coming; or they may have occasionally to wait below, while their authors are waiting above. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green (almost a batch of he-muses in themselves), will get a new cookery-book, well done, from a genuine cook,5 who divides his time between the spit and the pen; and the firm need not, therefore, set Mrs. Rundell's temper upon the simmer, as they are said to have done in days past. Reviewers too!—-will they ever dine together anon?—surely not. Authors are known to be in the malicious habit of speaking ill of their friends and judges behind their backs; and at dinner-time they will soon have every opportunity of so doing. How unpleasant to call for beer from the poet you have just set in a foam; or to ask for the carving-knife from the man you have so lately cut up! We reviewers shall then never be able to shoot our severity, without the usual coalman's memento of "take care below!" One advantage, however, from the new system must be conceded, and that is, that when an author waits in a great man's hall, or stands at his door, he will be pretty sure of being paid for it; which, in the case of your dangling garreteers, has never hitherto happened. Crabbe's story of "The Patron" will become obsolete. High Life will, indeed, be below stairs!

There is a lively spirit of banter in these observations, which is extremely amusing. They are from the Athenaeum of last week, which, by the way, has more of the intellectual gladiatorship in its columns than any of its critical contemporaries.

A Mr. Josph Hardaker has sung the praises of this gigantic power in thirty-five stanzas, entitled "the Aeropteron; or, Steam Carriage." If his lines run not as glibly as a Liverpool prize engine, they will afford twenty minutes pleasant reading, and are an illustration of the high and low pressure precocity of the march of mechanism.

Has appeared in somewhat better style than its predecessors. The paper is of better quality, the print is in better taste, and there are a few delicate copper-plate engravings. The old plan or chronological arrangement is, however, nearly worn threadbare, and to supply this defect there are in the present volume many specimens of contemporary literature. Few of them, however, are first-rate. The most original portion consists of the Astronomical Occurrences, which extend to 150 pages.

Such is the title of the fifth part or portion of Knowledge for the People: or, the Plain Why and Because: containing Attraction or Affinity—Crystallization—Heat—Electricity—Light and Flame—Combustion—Charcoal—Gunpowder and Volcanic Fire. We quote a few articles from most of the heads:—

Why is the science of chemistry so named?

Because of its origin from the Arabic, in which language it signifies "the knowledge of the composition of bodies."

The following definitions of chemistry have been given by some of our best writers:—

"Chemistry is the study of the effects of heat and mixture, with the view of [pg 174] discovering their general and subordinate laws, and of improving the useful arts."—Dr. Black.

"Chemistry is that science which examines the constituent parts of bodies, with reference to their nature, proportions, and method of combination."—Bergman.

"Chemistry is that science which treats of those events or changes, in natural bodies, which are not accompanied by sensible motions."—Dr. Thompson.

"Chemistry is a science by which we become acquainted with the intimate and reciprocal action of all the bodies in nature upon each other."—Fourcroy.

The four preceding definitions are quoted by Mr. Parkes, in his Chemical Catechism.

Dr. Johnson (from Arbuthnot) defines "chymistry" as "philosophy by fire."

Mr. Brande says, "It is the object of chemistry to investigate all changes in the constitution of matter, whether effected by heat, mixture, or other means."—Manual, 3rd edit. 1830.

Dr. Ure says, "Chemistry may be defined the science which investigates the composition of material substances, and the permanent changes of constitution which their mutual actions produce."—Dictionary, edit. 1830.

Sir Humphry Davy, in his posthumous work,6 says, "There is nothing more difficult than a good definition of chemistry; for it is scarcely possible to express, in a few words, the abstracted view of an infinite variety of facts. Dr. Black has defined chemistry to be that science which treats of the changes produced in bodies by motions of their ultimate particles or atoms; but this definition is hypothetical; for the ultimate particles or atoms are mere creations of the imagination. I will give you a definition which will have the merit of novelty, and which is probably general in its application. Chemistry relates to those operations by which the intimate nature, of bodies is changed, or by which they acquire new properties. This definition will not only apply to the effects of mixture, but to the phenomena of electricity, and, in short, to all the changes which do not merely depend upon the motion or division of masses of matter."

Cuvier, in one of a series of lectures, delivered at Paris, in the spring of last year, says, "the name chemistry, itself, comes from the word chim, which was the ancient name of Egypt;" and he states that minerals were known to the Egyptians "not only by their external characters, but also by what we at the present day call their chemical characters." He also adds, that what was afterwards called the Egyptian science, the Hermetic art, the art of transmuting metals, was a mere reverie of the middle ages, utterly unknown to antiquity. "The pretended books of Hermes are evidently supposititious, and were written by the Greeks of the lower Empire."

Why are the crystals collected in camphor bottles in druggists' windows always most copious upon the surface exposed to the light?

Because the presence of light considerably influences the process of crystallization. Again, if we place a solution of nitre in a room which has the light admitted only through a small hole in the window-shutter, crystals will form most abundantly upon the side of the basin exposed to the aperture through which the light enters, and often the whole mass of crystals will turn towards it.—Brande.

Why is sugar-candy crystallized on strings, and verdigris on sticks?

Because crystallization is accelerated by introducing into the solution a nucleus, or solid body, (like the string or stick) upon which the process begins.

The ornamental alum baskets, whose manufacture was once so favourite a pursuit of lady-chemistry, were made upon this principle; the forms of the baskets being determined by wire framework, to which the crystals readily adhere.

Why is sugar-candy sometimes in large and regular crystals?

Because the concentrated syrup has been kept for several days and nights undisturbed, in a very high temperature; for, if perfect rest and a temperature of from 120° to 190° be not afforded, regular crystals of candy will not be obtained.

The manufacture of barley-sugar is a familiar example of crystallization. The syrup is evaporated over a slow heat, till it has acquired the proper consistence, when it is poured on metal to cool, and when nearly so, cut into lengths with shears, then twisted, and again left to harden.

Why does hay, if stacked when damp, take fire?

Because the moisture elevates the [pg 175] temperature sufficiently to produce putrefaction, and the ensuing chemical action causes sufficient heat to continue the process; the quantity of matter being also great, the heat is proportional.

Why is the air warm in misty or rainy weather?

Because of the liberation of the latent heat from the precipitated vapour.

Why is heated air thinner or lighter than cold air?

Because it is a property of heat to expand all bodies; or rather we should say, that we call air hot or cold, according as it naturally is more or less expanded.

Why is a tremulous motion observable over chimney-pots, and slated roofs which have been heated by the sun?

Because the warm air rises, and its refracting power being less than that of the colder air, the currents are rendered visible by the distortion of objects viewed through them.

Within doors, a similar example occurs above the foot-lights of the stage of a theatre; the flame of a candle, or the smoke of a lamp.

Why are the gas chandeliers in our theatres placed under a large funnel?

Because the funnel, by passing through the roof into the outer air, operates as a very powerful ventilator, the heat and smoke passing off with a large proportion of the air of the house.

The ventilation of rooms and buildings can only be perfectly effected, by suffering the heated and foul air to pass off through apertures in the ceiling, while fresh air, of any desired temperature, is admitted from below.—Brande.

Why do heated sea-sand and soda form glass?

Because, by heating the mixture, the cohesion of the particles of each substance to those of its own kind is so diminished, that the mutual attractions of the two substances come into play, melt together, and unite chemically into the beautiful compound called glass.

Why is sand used in glass?

Because it serves for stone; it being said, that all white transparent stones which will not burn to lime are fit to make glass.

Why is an arrangement of several Leyden jars called an electrical battery?

Because by a communication existing between all their interior coatings, their exterior being also united, they may be charged and discharged as one jar.

The discharge of the battery is attended by a considerable report, and if it be passed through small animals, it instantly kills them; if through fine metallic wires, they are ignited, melted, and burned; and gunpowder, cotton sprinkled with powdered resin, and a variety of other combustibles, may be inflamed by the same means.

Why is the fireside an unsafe place in a thunder-storm?

Because the carbonaceous matter, or soot, with which the chimney is lined, acts as a conductor for the lightning.

Why is the middle of an apartment the safest place during a thunder-storm?

Because, should a flash of lightning strike a building, or enter at any of the windows, it will take its direction along the walls, without injuring the centre of the room.

Why does amàdou, or German tinder, readily inflame from flint and steel, or from the sudden condensation of air?

Because it consists of a vegetable substance found on old trees, boiled in water to extract its soluble parts, then dried and beat with a mallet, to loosen its texture; and lastly, impregnated with a solution of nitre.—-Ure.

Why is a piece of paper lighted, by holding it in the air which rushes out of a common lamp-glass?

Because of the high temperature of the current of air above the flame, the condensation of which is by the chimney of the glass.

We do not quote these specimens in the precise order in which they occur in the work, or to show the consecutive or connected interest of the several articles. In many cases we select them for their brevity and point of illustration.

A snapper up of unconsidered trifles.

SHAKSPEARE.

To give an idea of the enormous quantity of timber necessary to construct a ship of war, we may observe that 2,000 tons, or 3,000 loads, are computed to be required for a seventy-four. Now, reckoning fifty oaks to the acre, of 100 years' standing, and the quantity in each tree to be a load and a half, it would require forty acres of oak forest to build one seventy-four; and the quantity increases in a great ratio, for the largest class of line of battle ships. The average duration of these vast machines, when employed, is computed to be fourteen [pg 176] years. It is supposed, that all the full grown oaks now in Scotland would not build two ships of the line.

Quoth Dermot, (a lodger of Mrs. O'Flynn's),

"How queerly my shower bath feels!

It shocks like a posse of needles and pins,

Or a shoal of electrical eels."

Quoth Murphy, "then mend it, and I'll tell you how,

Its all your own fault, my good fellow;

I used to be bothered as you are, but now

I'm wiser—I take my umbrella."

Some of the following inscriptions are to be found in the "Beauchamp Tower."

In the third recess on the left hand is "T.C. I leve in hope, and I gave q credit to mi frinde, in time did stande me most in hande, so wolde I never doe againe, excepte I hade him suer in bande, and to al men wishe I so, unles ye sussteine the leike lose as I do.

"Unhappie is that mane whose actes doth procuer,

The miseri of this house imprison to induer.

"1576, Thomas Clark."

Just opposite the same is

"Hit is the poynt of a wyse man to try and then truste,

For Hapy is he who fyndeth one that is juste.

"T. Clarke."

In the same part of the room between the two last recesses is this, in old English:

"Ano. Dni ... Mens. As.

1568 J.H.S. 23

"No hope is hard or vayne

That happ doth ous attayne."

And on the wall on the top of the Beauchamp Tower, are the following lines on a Goldfinch:—

"Where Raleigh pined within a prison's gloom,

I chearful sung, nor murmur'd at my doom,

Where heroes bold and patriots firm could dwell,

A Goldfinch in Content his note might swell;

But death more gentle than the law's decree,

Hath paid my ransom from captivity.

"Buried June 23rd, 1794, by a fellow-prisoner

in the Tower of London."

One day, when Lord Thurlow was very busy at his house in Great Ormondstreet, a poor curate applied to him for a living then vacant, "Don't trouble me," said the chancellor, turning from him with a frowning brow; "don't you see I am busy, and can't listen to you?" The poor curate lifted up his eyes, and with dejection said, "he had no Lord to recommend him but the Lord of Hosts!" "The Lord of Hosts," replied the chancellor, "The Lord of Hosts! I believe I have had recommendations from most lords, but do not recollect one from him before, and so do you hear, young man, you shall have the living;" and accordingly presented him with the same.

The East India Company was established 1600, their stock then consisting of £72,000, when they fitted out four ships, and meeting with success, they have continued ever since; in 1683, India Stock sold from 360 to 500 per cent. A new company was established in 1698; re-established, and the two united, 1700, agreed to give government £400,000. per annum, for four years, on condition they might continue unmolested, 1769. In 1773, in great confusion, and applied to parliament for assistance; judges sent from England by government, faithfully to administer the laws there to the company's servants, 1774, April 2nd.

A country paper says, "The Corporation are about to build two free schools, one of which is finished."

Early in March will be published, price 5s.

ARCANA of SCIENCE, and ANNUAL REGISTER of the USEFUL ARTS for 1831.

Comprising POPULAR INVENTIONS, IMPROVEMENTS, and DISCOVERIES Abridged from the Transactions of Public Societies and Scientific Journals of the past year. With several Engravings.

"One of the best and cheapest books of the day."—Mag. Nat. Hist.

"An annual register of new inventions and improvements, in a popular form like this, cannot fail to be useful."—Lit. Gaz.

Printing for JOHN LIMBIRD, 143, Strand;—of whom may be had the Volumes for the three preceding years.

Footnote 1: (return) A view of the Chapel, from the Diorama, in the Regent's Park, with ample descriptive details, will be found in vol. v. of The Mirror.

Footnote 2: (return) From Lord Scroops, of Bolton.

Footnote 3: (return) Why is the a omitted?

Footnote 4: (return) The original inscription, ascribing to the Roman Catholics the fire which consumed the city, obliterated during the reign of James II. and restored with much pomp on the coming of King William, is now ordered, I hear, to be erased by the Common Council. Fiction is truth and truth is fiction as party prevails.

Footnote 5: (return) There is a cookery-book, by "a Lady," and a cookery-book by a Physician; but Mrs. Rundell and Dr. Kitchiner will soon be warned off the gridiron by the erudite genuine practical cook, who has a right to the kitchen stuff of literature. Mrs. R. must show herself to be what she professes, and take "her chops out of the frying-pan;" and the "good doctor" must "put his tongue into plenty of cold water" to cool its boiling, broiling ardour.

Footnote 6: (return) Consolations in Travel; or, the Last Days of a Philosopher. 1830.

Printed and Published by J. LIMBIRD, 143, Strand, (near Somerset House,) London; sold by ERNEST FLEISCHER, 626, New Market, Leipsic; G.G. BENNIS, 55, Rue Neuve, St. Augustin, Paris; and by all Newsmen and Booksellers.