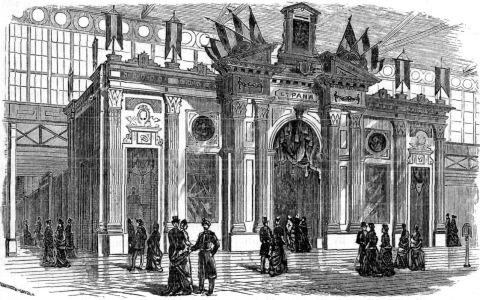

FAÇADE OF THE SPANISH DIVISION, MAIN BUILDING.

Title: Lippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Volume 17, No. 102, June, 1876

Author: Various

Release date: December 12, 2004 [eBook #14333]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Kathryn Lybarger and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team.

THE CENTURY—ITS FRUITS AND ITS FESTIVAL.

VI.—THE DISPLAY—INTRODUCTORY. 649

DOLORES by EMMA LAZARUS.666

GLIMPSES OF CONSTANTINOPLE by SHEILA HALE.

CONCLUDING PAPER. 668

THEE AND YOU by EDWARD KEARSLEY.

A STORY OF OLD PHILADELPHIA. IN TWO PARTS—I. 679

MODERN HUGUENOTS by JAMES M. BRUCE. 692

BLOOMING by MAURICE THOMPSON. 701

FELIPA by CONSTANCE FENIMORE WOOLSON. 702

AT CHICKAMAUGA by ROBERT LEWIS KIMBERLY. 713

THE ATONEMENT OF LEAM DUNDAS by MRS. E. LYNN LINTON.

CHAPTER XXXVII. UNWORTHY. 723

CHAPTER XXXVIII. BLOTTED OUT. 728

CHAPTER XXXIX. WINDY BROW. 733

CHAPTER XL. LOST AND NOW FOUND. 739

THE ITALIAN MEDIÆVAL WOOD-SCULPTORS by T. ADOLPHUS TROLLOPE. 746

REST by CHARLOTTE F. BATES. 754

LETTERS FROM SOUTH AFRICA by LADY BARKER. 755

OUR MONTHLY GOSSIP.

THE CABS OF PARIS by L.H.H. 764

A NEW MUSEUM AT ROME by T.A.T. 768

OUR FOREIGN SURNAMES by W.W.C. 770

THE NEW FRENCH ACADEMICIAN by R.W. 772

LITERATURE OF THE DAY. 774

BOOKS RECEIVED. 776

FAÇADE OF THE SPANISH DIVISION, MAIN BUILDING.

FAÇADE OF THE EGYPTION DIVISION, MAIN BUILDING.

FAÇADE OF THE SWEDISH DIVISION, MAIN BUILDING.

FAÇADE OF THE BRAZILIAN DIVISION, MAIN BUILDING.

FAÇADE OF THE DIVISION OF THE NETHERLANDS, MAIN BUILDING.

THE CORLISS ENGINE, FURNISHING MOTIVE-POWER FOR MACHINERY HALL.

INTERIOR OF COOK'S WORLD'S TICKET OFFICE.

SCENE AT ONE OF THE ENTRANCES TO THE GROUNDS—THE TURNSTILE.

CASTLE OF EUROPE, ON THE BOSPHORUS.

FORTRESS OF RIVA, AND THE BLACK SEA.

All things being ready for their reception, how were exhibits, exhibitors and visitors to be brought to the grounds? To do this with the extreme of rapidity and cheapness was essential to a full and satisfactory attendance of both objects and persons. In a large majority of cases the first consideration with the possessor of any article deemed worthy of submission to the public eye was the cost and security of transportation. Objects of art, the most valuable and the most attractive portion of the display, are not usually very well adapted to carriage over great distances with frequent transshipments. Porcelain, glass and statuary are fragile, and paintings liable to injury from dampness and rough handling; while an antique mosaic, like the [pg 650] "Carthaginian Lion," a hundred square feet in superficies, might, after resuscitation from its subterranean sleep of twenty centuries with its minutest tessera intact and every tint as fresh as the Phoenician artist left it, suffer irreparable damage from a moment's carelessness on the voyage to its temporary home in the New World. More solid things of a very different character, and far less valuable pecuniarily, though it may be quite as interesting to the promoter of human progress, exact more or less time and attention to collect and prepare, and that will not be bestowed upon them without some guarantee of their being safely and inexpensively transmitted. So to simplify transportation as practically to place the exposition buildings as nearly as possible at the door of each exhibitor, student and sight-seer became, therefore, a controlling problem.

In the solution of it there is no exaggeration in saying that the Centennial stands more than a quarter of a century in advance of even the latest of its fellow expositions. At Vienna a river with a few small steamers below and a tow-path above represented water-carriage. Good railways came in from every quarter of the compass, but none of them brought the locomotive to the neighborhood of the grounds. In the matter of tram-roads for passengers the Viennese distinguished themselves over the Londoners and Parisians by the possession of one. In steam-roads they had no advantage and no inferiority. At each and all of these cities the packing-box and the passenger were both confronted by the vexatious interval between the station and the exposition building—often the most trying part of the trip. Horsepower was the one time-honored resource, in '73 as in '51, and in unnumbered years before. Under the ancient divisions of horse and foot the world and its impedimenta moved upon Hyde Park, the Champ de Mars and the Prater, the umbrella and the oil-cloth tilt their only shield against Jupiter Pluvius, who seemed to take especial pleasure in demonstrating their failure, nineteen centuries after the contemptuous erasure of him from the calendar, to escape his power. It was reserved for the Philadelphia Commission to bring his reign (not the slightest intention of a pun) to a close. The most delicate silk or gem, and the most delicate wearer of the same, were enabled to pass under roof from San Francisco into the Main Building in Fairmount Park, and with a trifling break of twenty steps at the wharf might do so from the dock at Bremen, Havre or Liverpool. The hospitable shelter of the great pavilion was thus extended over the continent and either ocean. The drip of its eaves pattered into China, the Cape of Good Hope, Germany and Australia. Their spread became almost that of the welkin.

Let us look somewhat more into the detail of this unique feature of the American fair.

Within the limits of the United States the transportation question soon solved itself. Five-sixths of the seventy-four thousand miles of railway which lead, without interruption of track, to Fairmount Park are of either one and the same gauge, or so near it as to permit the use everywhere of the same car, its wheels a little broader than common. From the other sixth the bodies of the wagons, with their contents, are transferable by a change of trucks. The expected sixty or eighty thousand tons of building material and articles for display could thus be brought to their destination in a far shorter period than that actually allowed. Liberal arrangements were conceded by the various lines in regard to charges. Toll was exacted in one direction only, unsold articles to be returned to the shipper free. As the time for closing to exhibitors and opening to visitors approached the Centennial cars became more and more familiar to the rural watcher of the passing train. They aided to infect him, if free from it before, with the Centennial craze. Their doors, though sealed, were eloquent, for they bore in great black letters on staring white muslin the shibboleth of the day, "1776—International Exhibition—1876." The enthusiasm of those very hard and unimpressible entities, the railroad companies, thus [pg 651] manifesting itself in low rates and gratuitous advertising, could not fail to be contagious. Nor was the service done by the interior lines wholly domestic. Several large foreign contributions from the Pacific traversed the continent. The houses and the handicraft of the Mongol climbed the Sierra Nevada on the magnificent highway his patient labor had so large a share in constructing. Nineteen cars were freighted with the rough and unpromising chrysalis that developed into the neat and elaborate cottage of Japan, and others brought the Chinese display. Polynesia and Australia adopted the same route in part. The canal modestly assisted the rail, lines of inland navigation conducting to the grounds barges of three times the tonnage of the average sea-going craft of the Revolutionary era. These sluggish and smooth-going vehicles were employed for the carriage of some of the large plants and trees which enrich the horticultural department, eight boats being required to transport from New York a thousand specimens of the Cuban flora sent by a single exhibitor, M. Lachaume of Havana. Those moisture-loving shrubs, the brilliant rhododendra collected by English nurserymen from our own Alleghanies and returned to us wonderfully improved by civilization, might have been expected also to affect the canal, but they chose, with British taste, the more rapid rail. They had, in fact, no time to lose, for their blooming season was close at hand, and their roots must needs hasten to test the juices of American soil. Japan's miniature garden of miniature plants, interesting far beyond the proportions of its dimensions, was perforce dependent on the same means of conveyance.

The locomotive was summoned to the aid of foreign exhibitors on the Atlantic as on the Pacific side, though to a less striking extent, the largest steamships being able to lie within three miles of the exposition buildings. It stood ready on the wharves of the Delaware to welcome these stately guests from afar, indifferent whether they came in squadrons or alone. It received on one day, in this vestibule of the exposition, the Labrador from France and the Donati from Brazil. Dom Pedro's coffee, sugar and tobacco and the marbles and canvases of the Société des Beaux-Arts [pg 652] were whisked off in amicable companionship to their final destination. The solidarity of the nations is in some sort promoted by this shaking down together of their goods and chattels. It gives a truly international look to the exposition to see one of Vernet's battle-pieces or Meissonier's microscopic gems of color jostled by a package of hides from the Parana or a bale of India-rubber.

Yet more expressive was the medley upon the covered platforms for the reception of freight. Eleven of these, each one hundred and sixty by twenty-four feet, admitted of the unloading of fifty-five freight-cars at once. At this rate there was not left the least room for anxiety as to the ability of the Commission and its employés to dispose, so far as their responsibility was concerned, of everything presented for exhibition within a very few days. The movements of the custom-house officials, and the arrangements of goods after the passing of that ordeal, were less rapid, and there seemed some ground for anxiety when it was found that in the last days of March scarce a tenth of the catalogued exhibits were on the ground, and for the closing ten days of the period fixed for the receipt of goods an average of one car-load per minute of the working hours was the calculated draft on the resources of the unloading sheds. Home exhibitors, by reason of the very completeness of their facilities of transport, were the most dilatory. The United States held back until her guests were served, confident in the abundant efficiency of the preparations made for bringing the entertainers to their side. Better thus than that foreigners should have been behind time.

When the gates of the enclosure were at last shut upon the steam-horse, a broader and more congenial field of duty opened before him. From the rôle of dray-horse he passed to that of courser. Marvels from the ends of the earth he had, with many a pant and heave, forward pull and backward push, brought together and dumped in their allotted places. Now it became his task to bear the fiery cross over hill and dale and gather the clans, men, women and children. The London exhibition of 1851 had 6,170,000 visitors, and that of 1862 had 6,211,103. Paris in 1855 had 4,533,464, and in 1867, 10,200,000. Vienna's exhibition drew 7,254,867. The attendance at London on either occasion was barely double the number of her population. So it was with Paris at her first display, though she did much better subsequently. Vienna's was the greatest success of all, according to this test. The least of all, if we may take it into the list, was that of New York in 1853. Her people numbered about the same with the visitors to her Crystal Palace—600,000. Philadelphia's calculations went far beyond any of these figures, and she laid her plans accordingly.

Some trainbands from Northern and Southern cities might give their patriotic furor the bizarre form of a march across country, but the millions, if they came at all, must come by rail, and the problem was to multiply the facilities far beyond any previous experience, while reconciling the maximum of safety, comfort and speed with a reduction of fares. The arrangements are still to be tested, and are no doubt open to modification. On one point, however, and this an essential one, we apprehend no grounds of complaint. There will be no crowding. The train is practically endless, the word terminus being a misnomer for the circular system of tracks to which the station (six hundred and fifty by one hundred feet) at the main entrance of the grounds forms a tangent. The line of tourists is reeled off like their thread in the hands of Clotho, the iron shears that snip it at stated intervals being represented by the unmythical steam-engine. The same modern minister of the Fates has another shrine not far from the dome of Memorial Hall, where his acolytes are the officials of the Reading Railroad Company.

Care for the visitor's comfortable locomotion does not end with depositing him under the reception-verandah. The Commission did not forget that a pedestrian excursion over fifteen or twenty miles of aisles might sufficiently fatigue him without the additional trudge from hall to hall [pg 653] over a surface of four hundred acres under a sun which the century has certainly not deprived of any mentionable portion of its heat. Hence, the belt railway, three and a half miles long, with trains running by incessant schedule—a boon only to be justly appreciated by those who attended the European expositions or any one of them. His umbrella and goloshes pocketed in the form of a D.P.C. check, the visitor, more fortunate than Brummel or Bonaparte, cannot be stopped by the elements.

We shall have amply disposed of the subject of transportation when we add that the neighborhood or city supply to the thirteen entrance-gates is provided for by steam-roads capable of carrying twenty-four thousand persons hourly, and tram-roads seating seven thousand, besides an irregular militia or voltigeur force of light wagons, small steamers and omnibuses equal to a demand of two or three thousand more in the same time. It was not deemed likely that Philadelphia would require conveyance for half of her population every day. Should that supposition prove erroneous, the excess can fall back upon the safe and inexpensive vehicle of 1776, 1851, 1867 and 1873—sole leather.

Let us return to our packing-cases, and see where they go. To watch the gradual dispersal of a congregation to their several places of abode is always interesting. Especially is it so when those places of retreat bear the names and fly the flags of the several nations of the globe. This stout cube of deal, triple-bound with iron, disappears under the asp and winged sphere of the Pharaohs. That other, big with rich velvets and broideries, seeks the tricolor of France. Yonder, a wealth of silks and lacquer finds a resting-place in the carved black-walnut étagères of Japan. Here go, cased in the spoils of the fjelds, toward a pavilion seventy-five paces long and twenty wide, the bulky contributions of the Norsemen. Swedish carpentry in perfection offers to a deposit separate from that of the sister-kingdom a distinct receptacle. Close at hand stand the antipodes in the pavilion of Chili, that opens its graceful portal to bales sprinkled mayhap with the ashes of Aconcagua. There "crashes a sturdy box of stout John Bull;" and Russia, Tunis and Canada roll into close neighborhood with him and each other. A queer and not, let us hope, altogether transitory show of international comity is this. Many a high-sounding, much-heralded and more-debating Peace Congress has been held with less effect [pg 654] than that conducted by these humble porters, carpenters and decorators. This one has solidity. Its elements are palpable. The peoples not only bring their choicest possessions, but they also set up around them their local habitations. It is a cosmopolitan town that has sprung into being beneath the great roof and glitters in the rays of our republican sun. In its rectangularly-planned streets, alleys and plazas every style of architecture is represented—domestic, state and ecclesiastical, ancient, mediæval and modern. The spirit and taste of most of the races and climes find expression, giving thus the Sydenham and the Hyde Park palaces in one. The reproductions at the former place were the work of English hands: those before us are executed, for the most part, by workmen to whom the originals are native and familiar. In this feature of the interior of the Main Building we are amply compensated for the breaking up of the coup d'oeil by a multiplicity of discordant forms. The space is still so vast as to maintain the effect of unity; and this notwithstanding the considerable height of some of the national stalls, that of Spain, for example, sending aloft its trophy of Moorish shields and its effigy of the world-seeking Genoese to an elevation of forty-six feet. The Moorish colonnade of the Brazilian pavilion lifts its head in graceful rivalry of the lofty front reared by the other branch of the Iberian race. In so vast an expanse this friendly competition of Spaniards and Portuguese becomes, to the eye, a union of their pretensions; and a single family of thirty-three millions in Europe and America combines to present us with two of the handsomest structures in the hall.

A moderate dip into statistics can no longer be evaded. We must map out the microcosm, and allot to each sovereign power its quota of the surface. The great European states which have assumed within the century the supreme direction of human affairs are assigned a prominent central position in the Main Building. Great Britain and her Asiatic possessions occupy just eighty-three feet less than a hundred thousand; her other colonies, including Canada, 48,150; [pg 655] France and her colonies, 43,314; Germany, 27,975; Austria, 24,070; Russia, 11,002; Spain, 11,253; Sweden and Belgium, each 15,358; Norway, 6897; Italy, 8167; Japan, 16,566; Switzerland, 6646; China, 7504; Brazil, 6397; Egypt, 5146; Mexico, 6504; Turkey, 4805; Denmark, 1462; and Tunis, 2015. These, with minor apportionments to Venezuela, the Argentine Confederation, Chili, Peru and the Orange Free State of South Africa, cover the original area of the structure, deducting the reservation of 187,705 feet for the United States, and excluding thirty-eight thousand square feet in the annexes. France must be credited, in explanation of her comparatively limited territory under the main roof, with her external pavilions devoted to bronzes, glass, perfumery and (chief of all) to her magnificent government exhibit of technical plans, drawings and models in engineering, civil and military, and architecture. These outside contributions constitute a link between her more substantial displays and the five hundred paintings, fifty statues, etc. she places in Memorial Hall.

In Machinery and Agricultural Halls, respectively, Great Britain has 37,125 and 18,745 feet; Germany, 10,757 and 4875; France, 10,139 and 15,574; Belgium, 9375 and 1851; Canada, 4300 and 10,094; Brazil, 4000 and 4657; Sweden, 3168 and 2603; Spain, 2248 and 5005; Russia, 1500 and 6785; Chili, 480 and 2493; Norway, 360 and 1590. Austria occupies 1536 feet in Mechanical Hall; and in that of Agriculture are the following additional allotments: Netherlands, 4276; Denmark, 836; Japan, 1665; Peru, 1632; Liberia, 1536; Siam, 1220; Portugal, 1020.

The foreign contributions in the department of machinery are, it will be seen, hardly so large as might have been anticipated. When the spacious annexes are added to the floor of the main hall, the great preponderance of home exhibitors—five to one in the latter—is shown to be still more marked. In Agricultural Hall the United States claim less than two-thirds. The unexpected interest taken in this branch by foreigners will enhance its prominence and value among the attractions of the exposition. The collection of tropical products for food and manufacturing is very complete. The development of the equatorial regions of the globe has barely commenced. Even our acquaintance with their natural resources remains but superficial. The country which takes the lead in utilizing them in its trade and manufactures will gain a great advantage over its fellows. England's commercial supremacy never rested more largely on that foundation than now. Brazil, the great power of South—as the Union is of North—America, possesses nearly half of the accessible virgin territory of the tropics. Our interest joins hers in retaining this vast endowment as far as possible for the benefit of the Western World. A perception of this fact is shown in the exceptional efforts made by Brazil to be fully represented in all departments of the exposition, and in the visit to it of her chief magistrate, as we may properly term her emperor, the only embodiment of hereditary power and the monarchical principle in a country that enjoys—and has for the half century since its erection into an independent state maintained—free institutions.

In art domestic exhibits utterly lose [pg 656] their preponderance. Our artists content themselves with a small fraction of the wall- and floor-space in Memorial Hall and its northern annex. In extent of both "hanging" and standing ground they but equal England and France, each occupying something over twenty thousand square feet. Italy in the æsthetic combat selects the chisel as her weapon, and takes the floor with a superb array of marble eloquence, some three hundred pieces of statuary being contributed by her sculptors. She might in addition set up a colorable claim to the works executed on her soil or under the teaching of her schools by artists of other nativities, and thus make, for example, a sweeping raid into American territory. But she generously leaves to that division the spoils swept from her coasts by the U.S. ship Franklin, together with the works bearing her imprint in other sections, satisfied with the wealth undoubtedly her own, itself but a faint adumbration of the vast hoard she retains at home. Italy does not view the occasion from a fine-art standpoint alone. Of her nine hundred and twenty-six exhibitors, only one-sixth are in this department.

Nor, on the art side of our own country, must we overlook the Historical division, the perfecting of which has been a labor of love with Mr. Etting. He allots space among the old Thirteen, and reserves a place at the feast of reunion to the mother of that rebellious sisterhood.

Forty acres of "floor-space" sub Jove remained to be awarded to foreign and domestic claimants. Gardening is one of the fine arts. Certainly nothing in Memorial Hall can excel its productions in richness, variety and harmony of color and form. Flower, leaf and tree are the models of the palette and the crayon. Their marvelous improvement in variety and splendor is one of the most striking triumphs of human ingenuity. A few hundred species have been expanded into many thousand forms, each finer than the parent. It is a new flora created by civilization, undreamed of by the savage, and voluminous in proportion to the mental advancement of the races among whom it has sprung up. Progress writes its record in flowers, and scrawls the autographs of the nations all over Lansdowne hill. No need of gilded show-cases to set off the German and Germantown roses, the thirty thousand hyacinths in another compartment, or the plot of seven hundred and fifty kinds of trees and shrubs planted by a single American contributor. The Moorish Kiosque, however, comes in well. The material is genuine Morocco, the building having been brought over in pieces from the realm of the Saracens, of "gul in its bloom" and of "Larry O'Rourke"—as Rogers punned down the poem of his Irish friend.

The nations comfortably installed, we must sketch the tactical system under which they are drawn up for peaceful contest. The classification of subjects adopted by the Commission embraces seven departments. Of these, the Main Building is devoted to I. Mining and Metallurgy; II. Manufactures; III. Education and Science; Memorial Hall and its appendages, to IV. Art; Machinery Hall, to V. Machinery; Agricultural Hall, to VI. Agriculture; and Horticultural Hall and its parterres, to VII. Horticulture. These habitats have, as we have heretofore seen, proved too contracted for the august and [pg 657] expansive inmates assigned them. All of the latter have overflowed; mining, for instance, into the mineral annex of thirty-two thousand square feet and the great pavilion (a hundred and thirty-five feet square) of Colorado and Kansas; education into the Swedish and Pennsylvania school-houses and others already noted; manufactures into breweries, glass-houses, etc.; and so on with an infinity of irrepressible outgrowths.

Department I. is subdivided into classes numbered from 100 to 129, and embracing the products of mines and the means of extracting and reducing them. II. extends from Class 200 to Class 296—chemical manufactures, ceramics, furniture, woven goods of all kinds, jewelry, paper, stationery, weapons, medical appliances, hardware, vehicles and their accessories. III. deals with the high province of educational systems, methods and libraries; institutions and organizations; scientific and philosophical instruments and methods; engineering, architecture in its technical and non-æsthetic aspect, maps; physical, moral and social condition of man. Fifty classes, 300 to 349 inclusive, fence in this field of pure reason. Department IV., Classes 400-459, covers sculpture, painting, photography, engraving and lithography, industrial and architectural designs, ceramic decorations, mosaics, etc. V., Classes 509-599, takes charge of machines and tools for mining, chemistry, weaving, sewing, printing, working metal, wood and stone; motors; hydraulic and pneumatic apparatus; railway stock or "plant;" machinery for preparing agricultural products; "aërial, pneumatic and water transportation," and "machinery and apparatus especially adapted to the requirements of the exhibition." VI., Classes 600-699, assembles arboriculture and forest products, pomology, agricultural products, land and marine animals, pisciculture and its apparatus, "animal and vegetable products," textile substances, machines, implements and products of manufacture, agricultural engineering and administration, tillage and general management. Under Department VII., Classes 700-739, come ornamental trees, shrubs and flowers, hothouses and conservatories, garden tools and contrivances, garden designing, construction and management.

The accumulated experience of past expositions, seconded by the judgment and systematic thoroughness apparent in the preparations for the present one, makes this a good "working" classification. It has done away with confusion to an extent hardly to have been hoped for, and all the thousands of objects and subjects have dropped into their places in the exhibition with the precision [pg 658] of machinery, little adapted as some of them are to such treatment. Very impalpable and elusive things had to submit themselves to inspection and analysis, and have their elements tabulated like a tax bill or a grocery account. All human concerns were called on to be listed on the muster-roll and stand shoulder to shoulder on the drill-ground. Some curious comrades appear side by side in the long line. For example, we read: Class 286, brushes; 295, sleighs; 300, elementary instruction; 301, academies and high schools, colleges and universities; 305, libraries, history, etc.; 306, school-books, general and miscellaneous literature, encyclopædias, newspapers; 311, learned and scientific associations, artistic, biological, zoological and medical schools, astronomical observatories; 313, music and the drama. Then we find, closely sandwiched between, 335—topographical maps, etc.—and 400—figures in stone, metal, clay or plaster—340, physical development and condition (of the young of the genus Homo); 345, government and law; 346, benevolence, beginning with hospitals of all kinds and ending with—in the order we give them—emigrant-aid societies, treatment of aborigines and prevention of cruelty to animals! In the last-named subdivision the visitor will be stared out of countenance by Mr. Bergh's tremendous exposure of "various instruments used by persons in breaking the law relative to cruelty to animals," the glittering banner of the S.P.C.A., and its big trophy, eight yards square, that illuminates the east end of the north avenue of the Main Building, in opposition to the trophy at the other end of the same avenue illustrating the history of the American flag. But he will look in vain for selected specimens of the emigrant-runner, the luxuries of the steerage and Castle Garden, or for photographs of the well-fed post-trader and Indian agent, agricultural products from Captain Jack's lava-bed reservation and jars of semi-putrescent treaty-beef. He will alight, next door to the penniless immigrant, the red man and the omnibus-horse, on Class 348, religious organizations and systems, embracing everything that grows out of man's sense of responsibility to his Maker. It will perhaps occur to the observer that, though the juxtaposition is well enough, religion ought to have come in a little before. His surprise at the power of condensation shown in compressing eternity into a single class will not be lessened when he passes on to Class 632, sheep; 634, swine; and 636, dogs and cats!

A glance over the classification-list assists us in recognizing the advantages of the system of awards framed by the Commission and adopted after patient study and discussion. It discards the plan—if plan it could be called—of scattering diplomas and medals of gold, silver and bronze right and left, after the fashion of largesse at a mediæval coronation, heretofore followed at international expositions. These prizes were decided on and assigned by juries whose impartiality—by reason of the imperfect representation upon them of the nations which exhibited little in mass or little in certain classes, and also of their failure to make written reports and thus secure their responsibility—could not be assured, and whose action, therefore, was defective in real weight and value. The juries were badly constituted: they had too much to do of an illusory and useless description, and they had too little to do that was solid and instructive. Special mentions, diplomas, half a dozen grades of medals and other honors, formed a programme too large and complicated to be discriminatingly carried out. So it happened that to exhibit and to get a distinction of some kind came, at Vienna, to be almost convertible expressions; and who excelled in the competition in any of the classes, or who had contributed anything substantial to the stock of human knowledge or well-being, remained quite undetermined. What instruction the display could impart was confined to spectators who studied its specialties for themselves and used their deductions for their individual advantage, and to those who read the sufficiently general and cursory reports made to their several governments by the national commissions. The official [pg 659] awards and reports of the exposition authorities amounted to little or nothing.

A sharp departure from this practice was decided on at the Centennial. Two hundred judges, of undoubted character and intelligence and entire familiarity with the departments assigned to them, were chosen—half by the foreign bureaus and half by the U.S. Commission. These were made officers of the exposition itself, and thus separated from external influences. They were given a reasonable and fixed compensation of one thousand dollars each for their time and personal expenses. An equal division of the number of judges between the domestic and foreign sides gives the latter an excess, measured by the comparative extent of the display from the two sources. But this is favorable to us, as we shall be the better for an outside judgment on the merits of both our own and foreign exhibits. Were it otherwise, the excess of private observers from this country would counterbalance our deficit in judges. The foreign jurors have to see for the millions they represent. Our own will have vast numbers of their constituents on the ground.

Written reports are drawn up by these selected examiners and signed by the authors. The reports must be "based upon inherent and comparative merit. The elements of merit shall be held to include considerations relating to originality, invention, discovery, utility, quality, skill, workmanship, fitness for the purpose intended, adaptation to public wants, economy and cost." Each report, upon its completion, is delivered to the Centennial Commission for award and publication. The award comes in the shape of a diploma with a bronze medal and a special report of the judges [pg 660] upon its subject. This report may be published by the exhibitor if he choose. It will also be used by the Commission in such manner as may best promote the objects of the exposition. These documents, well edited and put in popular form, will constitute the most valuable publication that has been produced by any international exhibition. To this we may add the special reports to be made by the State and foreign commissions. These ought, with the light gained by time, to be at least not inferior to the similar papers scattered through the bulky records of previous exhibitions. Let us hope that brevity will rule in the style of all the reports, regular and irregular. There is a core to every subject, every group of subjects and every group of groups, however numerous and complex: let all the scribes labor to find it for us. When we recall the disposition of all committees to select the member most fecund of words to prepare their report, we are seized with misgivings—a feeling that becomes oppressive as we further reflect that the local committee which deliberately collected and sent for exhibition eighty thousand manuscripts written by the school-children of a Western city is at large on the exposition grounds.

The passion for independent effort characteristic of the American people led to the supplementing of the official list by sundry volunteer prizes. These are offered by associations, and in some cases individuals. They are not all, like the regular awards, purely honorary. They lean to the pecuniary form, those particularly which are offered in different branches of agriculture. Competition among poultry-growers, manufacturers of butter, reaping-and threshing-machines, cotton-planters, etc. is stimulated by money-prizes reaching in all some six or eight thousand dollars. Agricultural machinery needs the open field for its proper testing, and cannot operate satisfactorily in Machinery Hall. Without a sight of our harvest-fields and threshing-floors foreigners would carry away an incomplete impression of our industrial methods, the farm being our great factory. The oar, the rifle and the racer are as impatient of walls as the plough and its new-fangled allies. They demand elbow-room for the display of their powers, and the Commission was fain to let their votaries tempt it to pass the confines of its territory. The lusty undergraduates of both sides of Anglo-Saxondom escort it unresistingly down from its airy halls to the blue bosom of the Schuylkill, while "teams" picked from eighty English-speaking millions beckon it across the Jerseys to Creedmoor. And the horse—is he to call in vain? Is a strait-laced negative from the Commission to echo back his neigh? Is the blood of Eclipse and Godolphin to stagnate under a ticket in "Class 630, horses, asses and mules"? Why, the very ponies in front of Memorial Hall pull with extra vim against their virago jockeys and flap their little brass wings in indignation at the thought. The thoroughbred will be heard from, and the judges that sit on him will be "experts in their department."

Another specimen of the desert-born, the Western Indian, forms an exhibit as little suited as the improved Arab horse to discussion and award at a session fraught with that "calm contemplation and poetic ease" which ought to mark the deliberations of the judges. How are the representatives of fifty-three tribes to be put through their paces? These poor fragments of the ancient population of the Union have, if we exclude the Cherokees and Choctaws and two or three of the Gila tribes, literally nothing to show. The latter can present us with a faint trace of the long-faded civilization of their Aztec kindred, while the former have only borrowed a few of the rudest arts of the white, and are protected from extinction merely by the barrier of a frontier more and more violently assailed each year by the speculator and the settler, and already passed by the railway. If we cannot exactly say that the Indian, alone of all the throng at the exhibition, goes home uninformed and unenlightened, what ideas may reach his mind will be soon smothered out by the conditions which surround him on the Plains. It is singular that a population of three [pg 661] or four hundred thousand, far from contemptible in intellectual power, and belonging to a race which has shown itself capable of a degree of civilization many of the tribes of the Eastern continents have never approached, should be so absolutely an industrial cipher. The African even exports mats, palm-oil and peanuts, but the Indian exports nothing and produces nothing. He lacks the sense of property, and has no object of acquisition but scalps. Can the assembled ingenuity of the nineteenth century, in presence of this mass of waste human material, devise no means of utilizing it? There stands its Frankenstein, ready made, perfect in thews and sinews, perfect also in many of its nobler parts. It is not a creation that is demanded—simply a remodeling or expansion. For success in this achievement the United States can afford to offer a pecuniary prize that will throw into the shade all the other prizes put together. The cost of the Indian bureau for 1875-76 reached eight millions of dollars. The commission appointed to treat for the purchase of the Black Hills reports that the feeding and clothing of the Sioux cost the government thirteen millions during the past seven years; and that without the smallest benefit to those spirited savages. Says the report: "They have made no advancement whatever, but have done absolutely nothing but eat, drink, smoke and sleep."

Social and political questions like this point to a vast field of inquiry. For its proper cultivation the exposition provides data additional to those heretofore available. They should be used as far as possible upon the spot. At least, they can be examined, collated and prepared for full employment. To this end, meetings and discussions held by men qualified by intellect and study to deal with them are the obvious resort. There is room among the two hundred judges for some such men, but the juries are little more numerous than is required for the examination of and report on objects. For more abstract inquiries they will need recruits. These should be supplied by the leading philosophical associations of this country and Europe. The governments have all an interest in enlisting their aid, and the Centennial Commission has done what in it lay to promote their action. Ethnic [pg 662] characteristics, history, literature, education, crime, statistics as a science, hygiene and medicine generally are among the broad themes which are not apt to be adequately treated by the average committee of inspection. So with the whole range of the natural sciences. Dissertations based on the jury reports will doubtless be abundant after a while, but those reports themselves, being limited in scope, will not be as satisfactory material as that which philosophic specialists would themselves extract from direct observation and debate upon the ground.

For the study of the commanding subject of education the provision made at the present exhibition is exceptionally great. In bulk, and probably in completeness, it is immeasurably beyond the display made on any preceding occasion. The building erected by the single State of Pennsylvania for her educational department covers ten or eleven thousand square feet, and other States of the Union make corresponding efforts to show well in the same line. The European nations all manifest a new interest in this branch, and give it a much more prominent place in their exhibit than ever before. The school-systems of most of them are of very recent birth, and do not date back so far as 1851. The kingdom of Italy did not exist at that time or for many years after, yet we now see it pressing for a foremost place in the race of popular education, and multiplying its public schools in the face of all the troubles attendant upon the erection and organization of a new state.

The historian will find aliment less abundant. A century or two of Caucasian life in America is but a thing of yesterday to him, and, though far from uninstructive, is but an offshoot from modern European annals. For all that, he finds himself on our soil in presence of an antiquity which remains to be explored, and which clamors to be rescued from the domain of the pre-historic. It has no literary records beyond the scant remains of Mexico. It writes itself, nevertheless, strongly and deeply on the face of the land—in mounds, fortifications and tombs as distinct, if not so elaborate, as those of Etruria and Cyprus. These remains show the hand of several successive races. Who they were, what their traits, whence they came, what their relations with the now civilized Chinese and Japanese—whom, physically, their descendants so nearly resemble—are legitimate queries for the historian. Geologically, America is older than Europe, and was fitted for the home of the red man before the latter ceased to be the home of the whale. The investigation of its past, if impossible to be conducted in the light of its own records or even traditions, is capable of aiding in the verification of conclusions drawn from those of the Old World. If History, however, contemptuously relegates the Moundbuilders to the mattock of the antiquarian, she is still "Philosophy teaching by example." As thus allied with Philosophy, she finds something to look into at the Centennial, even though she look obliquely, after the fashion of the observant Hollanders, who have stuck the reflecting glasses of the Dutch street-windows into the sides of their compartment in the Main Building, and squint, without a change of position, upon the United States, Spain, South America, Egypt, Great Britain and several other countries.

Religion and philanthropy find the field inviting, and their representatives, individual and associated, are busy in preparing to till it. The enthusiasm of the leading religious societies took the concrete shape of statuary. Hence the Catholic Fountain, heretofore noticed; the Hebrew statue to Religious Liberty, as established in a land that never had a Ghetto or a Judenstrasse; the Presbyterian figure of Witherspoon; an Episcopalian of Bishop White; and others under way or proposed. The temperance movement, too, embodies itself in a fountain that runs ice-water instead of claret. The less tangible but perhaps more fruitful form of reunions and discussions must in a greater or less degree enhance the power for good of these organizations. They are led by men of mind and energy, seldom averse to enlightenment, and all professing to seek nothing else. [pg 663] When men of these qualities, aiming at the same or a like object, meet to compare their respective admeasurements of its parallax made from as many different points, they cannot fail to approach accuracy. Faith is a first element in all great undertakings. It removes mountains at Mont Cenis, as it walked the waves with Columbus. In our century even faith is progressive, and does not shrink from elbowing its way through what Bunyan would have styled Vanity Fair.

Modestly in the rear of the moral reformers, yet not wholly and uniformly unaggressive, nor guiltless altogether of isms and schisms, step forward the literary men. As a rule, they do not affect expositions, or exhibitions of any kind. But one general meeting, with some minor and informal ones, is on the programme for them. This is well. The world and the fullness thereof belongs to them, and they may care to come forward to scan this schedule of their inheritance. We do not hear of their having combined to put up a pavilion of their own, like the dairymen and the brewers, "to show the different processes of manufacture." The pen will be at work here, nevertheless, and has been from the beginning, before the foundations of the Corliss engine were laid or the granite of Memorial Hall left the quarry. Without this first of implements none of the other machinery would ever have moved. The pen is mightier than the piston. It is the invisible steam that impels all.

In a visible form also it is here. The publishers of the London Punch have selected as the most comprehensive motto for the case in which they exhibit copies of their various publications a sentence from Shakspeare: "Come and take choice of all my library, and so beguile thy sorrow." We do not know that to dull his sorrows is all that can be done for man. Literature assumes to do more than make him forget. The lotos-eater is not its one hero. School-books, piled aloft "in numbers without number numberless," may to the man be suggestive of hours without thought and void of grief, but they certainly are not to the boy. Blue books, ground out in a thousand bureaus, and contributed in like profusion, may be pronounced a weariness to the adult flesh, however sweet their ultimate uses. Unhappy those who wade through them for increasing the happiness of others! These humble but portly representatives of political literature are the log-books of the ship of state. They chart and chronicle the currents and winds along its course, so that from the mass of chaff a grain of guidance may be painfully winnowed out for the benefit of its next voyage, or for the voyages of other craft floundering on the same perilous and baffling sea. Everything comes pat to a log-book. As endless is the medley of memoranda in blue-books. They deal, like government itself, with everything. They take up the citizen on his entry into the cradle, and do not quite drop him at the grave. How to educate, clothe, feed and doctor him; how to keep him out of jail, and how, once there, to get him out again with the least possible moral detriment; how to adjust as lightly as possible to his shoulders the burden of taxation; how to economize him as food for powder; and how to free him from the miasm of crowded cities,—are but a small part of their contents. And the index is growing, if possible, larger, as the apparatus of government becomes more and more intricate. With such contributions and credentials do the rulers of the nations enroll [pg 664] themselves in the guild of authorship. They are proud of them, and exhibit them in profusion, in whole libraries, rich with gold and the primary colors.

Expositions, as we have before remarked, come into the same worshipful guild by right of a special literature they have brought into being. They come, moreover, into the blue-book range by their bearing upon certain topics generally assigned to it. It is found, for example, that, like other great gatherings, they are apt to be followed by a temporary local increase of crime. The police-records of London show that the arrests in 1851 outnumbered those of the previous year by 1570, and that in 1862 the aggregate exceeded by 5043 that of 1861. It will at once occur that the population of the city was greatly increased on each occasion, and that the influx of thieves and lawbreakers generally must have thinned out that class elsewhere, and in that way very probably reduced, rather than added to, the sum-total of crime, the preventive arrangements in London having been exceptionally thorough. The drawback that would consist in an increase of crime is therefore only an apparent result. An opposite effect cannot but result, if only from the evidence that so vast and heterogeneous an assemblage can be held without marked disorder. The police as well as the criminals and the savants of all nations come together, compare notes and enjoy a common improvement.

This is the first opportunity the physicians of Europe have had to become fully acquainted with the advances in surgery and pathology their American brethren have the credit of having made within the past few years. They will find it illustrated in the government buildings and elsewhere; and they have an ample quid pro quo to offer from their own researches. The balancing of opinions at the proposed medical congress and in private intercourse must tend to free medical science from what remnants of empiricism still disfigure it, to perfect diagnosis and to trace with precision the operation of all remedial agents. Means remain to be found of administering the coup de grâce to the few epidemics which have not yet been extirpated, but linger in a crippled condition. This will be aided by the illustrations afforded of processes of draining, ventilation, etc.

Man's health rests in that of his stomach. The food question is a concern of the physician as well as of the publicist. The race began life on a vegetable diet, and to that it reverts when compelled by enfeebled digestion or by the increasing difficulty of providing animal food for a dense population. But it likes flesh when able to assimilate it or to procure it, and demands at least the compromise of fish. Hence, the revived attention to fish-breeding, an art wellnigh forgotten since the Reformation emptied the carp-ponds of the monks. Maryland, New York and other States illustrate this device for enhancing the food-supply, and the aquaria at Agricultural Hall, containing twelve or fifteen thousand gallons of salt and fresh water, present a congress of the leaders, gastronomically speaking, of the finny people. The shad remains not only to be naturalized in Europe, but to be reintroduced to the water-side dwellers above tide, who [pg 665] once met him regularly at table. He is joined by delegates from the mountain, the great lakes and the Pacific coast in the trout, the salmon and the whitefish, and by that quiet, silent and slow-going cousin of the fraternity, the oyster, most valuable of all, as possessors of those qualities not unfrequently are. Europe does not dream, and we ourselves do not realize until we come carefully to think of it, what the oyster does for us. He sustains the hardiest part of our coasting marine, paves our best roads, fertilizes our sands, enlivens all our festivities, and supports an army of packers, can-makers, etc., cased in whose panoply of tin he traverses the globe like a mail-clad knight-errant in the cause of commerce and good eating. Yet he needs protection. All this burden is greater than he can bear, and it is growing. System and science are invoked to his rescue ere he go the way of the inland shad and the salmon that became a drug to the Pilgrim Fathers. It is not easy to frame a medal or diploma for the fostering of the oyster. More effective is a consideration of the impending penalty for neglecting to do so. Ostrea edulis is one of the grand things before which prizes sink into nothingness.

Another of them is that triumph of pure reason, chess, an unadulterated product of the brain—i.e., of phosphorus—i.e., of fish. Nobody stakes money on chess or offers a prize to the best player. Honor at that board is its own reward. So when we are told of the Centennial Chess Tournament we recognize at once the fitness of the word borrowed from the chivalric joust. It is the culmination of human strife. The thought, labor and ardor spread over three hundred and fifty acres sums itself in that black and white board the size of your handkerchief. War and statecraft condense themselves into it. Armies and nations move with the chessman. Sally, leaguer, feint, flank-march, triumphant charge are one after another rehearsed. There, too, moves the game of politics in plot and counterplot. It is the climax of the subjective. From those lists the trumpet-blare, the crowd, the glitter, the banners, "the boast of heraldry and pomp of power," melt utterly away. To the world-champions who bend above the little board the big glass houses and all the treasures stared at by admiring thousands are as naught.

But man is an animal, and not by any means of intellect all compact. The average mortal confesses to a craving for the stimulus of great shows, of material purposes, substantial objects of study and palpable prizes. It is so in 1876, as it was in 1776, and as it will be in a long series of Seventy-sixes.

[pg 666] It is the concrete rather than the abstract which draws him in through the turnstiles of the exposition enclosure. Separated by the divisions of those ingeniously-contrived gates into taxed and untaxed spectators, the masses stream in with small thought of the philosophers or the chess-players. Their minds are reached, but reached through the eye, and the first appeal is to that. Each visitor constitutes himself a jury of one to consider and compare what he sees. The hundreds of thousands of verdicts so reached will be published only by word of mouth, if published at all. Their value will be none the less indubitable, though far from being in all cases the same. The proportion of intelligent observers will be greater than on like occasions heretofore. So will, perhaps, be that of solid matter for study, although in some specialties there may be default. He who enters with the design of self-education will find the text-books in most branches abundant, wide open before him and printed in the clearest characters. What shortcomings there may have been in the selection and arrangement of them he will have, if he can, himself to remedy. There stands the school, founded and furnished with great labor. The would-be scholar can only be invited to use it. The centennial that is to turn out scholars ready-made has not yet rolled round.

A light at her feet and a light at her head,

How fast asleep my Dolores lies!

Awaken, my love, for to-morrow we wed—

Uplift the lids of thy beautiful eyes.

Too soon art thou clad in white, my spouse:

Who placed that garland above thy heart

Which shall wreathe to-morrow thy bridal brows?

How quiet and mute and strange thou art!

And hearest thou not my voice that speaks?

And feelest thou not my hot tears flow

As I kiss thine eyes and thy lips and thy cheeks?

Do they not warm thee, my bride of snow?

Thou knowest no grief, though thy love may weep.

A phantom smile, with a faint, wan beam,

Is fixed on thy features sealed in sleep:

Oh tell me the secret bliss of thy dream.

Does it lead to fair meadows with flowering trees,

Where thy sister-angels hail thee their own?

Was not my love to thee dearer than these?

Thine was my world and my heaven in one.

I dare not call thee aloud, nor cry,

Thou art so solemn, so rapt in rest,

But I will whisper: Dolores, 'tis I:

My heart is breaking within my breast.

Never ere now did I speak thy name,

Itself a caress, but the lovelight leapt

Into thine eyes with a kindling flame,

And a ripple of rose o'er thy soft cheek crept.

But now wilt thou stir not for passion or prayer,

And makest no sign of the lips or the eyes,

With a nun's strait band o'er thy bright black hair—

Blind to mine anguish and deaf to my cries.

I stand no more in the waxen-lit room:

I see thee again as I saw thee that day,

In a world of sunshine and springtide bloom,

'Midst the green and white of the budding May.

Now shadow, now shine, as the branches ope,

Flickereth over my love the while:

From her sunny eyes gleams the May-time hope,

And her pure lips dawn in a wistful smile.

As one who waiteth I see her stand,

Who waits though she knows not what nor whom,

With a lilac spray in her slim soft hand:

All the air is sweet with its spicy bloom.

I knew not her secret, though she held mine:

In that golden hour did we each confess;

And her low voice murmured, Yea, I am thine,

And the large world rang with my happiness.

To-morrow shall be the blessedest day

That ever the all-seeing sun espied:

Though thou sleep till the morning's earliest ray,

Yet then thou must waken to be my bride.

Yea, waken, my love, for to-morrow we wed:

Uplift the lids of thy beautiful eyes.

A light at her feet and a light at her head,

How fast asleep my Dolores lies!

There is a continuous fascination about this old city. The guide-book says, "A week or ten days are required to see the sights," but though we make daily expeditions we seem in no danger of exhausting them. Neither does one have to go far to seek amusement. I never look down into the street below my windows without being attracted by some object of interest. The little donkeys with their great panniers of long slim loaves of bread (oh, tell it not, but I once saw the driver use one as a stick to belabor the lazy animal with, and then leave it, with two or three other loaves, at the opposite house, where a pretty Armenian, that I afterward saw taking the air on the roof with her bright-eyed little girl, perhaps had it for her breakfast!); the fierce, lawless Turkish soldiers stalking along, their officers mounted, and looking much better in their baggy trousers and frock-coats on their fine horses than on foot; Greek and Armenian ladies in gay European costumes; veiled Turkish women in their quiet street-dress; close carriages with gorgeously-dressed beauties from the sultan's harem followed by black eunuchs on horseback,—these and similar groups in every variety of costume form a constant stream of strange and picturesque sights.

One morning, attracted by an unusual noise, I looked out and found it proceeded from a funeral procession. First came a man carrying the lid of the coffin; then several Greek priests; after them boys in white robes with lighted candles, followed by choir-boys in similar dresses who chanted as they walked along. Such sounds! Greek chanting is a horrible nasal caterwauling. Get a dozen boys to hold their noses, and then in a high key imitate the gamut performed by several festive cats as they prowl over the housetops on a quiet night, and you have Greek, Armenian or Turkish chanting and singing to perfection. There is not the first conception of music in the souls of these barbarians. Behind this choir came four [pg 669]men carrying the open coffin. The corpse was that of a middle-aged man dressed in black clothes, with a red fez cap on the head and yellow, red and white flowers scattered over the body. The hot sun shone full on the pinched and shriveled features, and the sight was most revolting. Several mourners followed the coffin, the ladies in black clothes, with black lace veils on their heads and their hair much dressed. The Greeks are obliged to carry their dead in this way, uncovered, because concealed arms were at one time conveyed in coffins to their churches, and then used in an uprising against the government. We witnessed a still more dreadful funeral outside the walls. A party, evidently of poor people, were approaching an unenclosed cemetery, and we waited to see the interment. The body, in its usual clothes, was carried on a board covered by a sheet. When they reached the grave the women shrieked, wept and kissed the face of the dead man: then his clothes were taken off, the body wrapped in the sheet and laid in the grave, which was only two feet deep. The priest broke a bottle of wine over the head, the earth was loosely thrown in, and the party went away. There is no more melancholy spot to me than a Turkish cemetery. The graves are squeezed tightly together, and the headstones, generally in a tumble-down state, are shaped like a coffin standing on end, or like a round hitching-post with a fez cap carved on the top. Weeds and rank wild-flowers cover the ground, and over all sway the dark, stiff cypresses.

A little way down the street is a Turkish pastry-shop. Lecturers and writers have from time to time held forth on the enormities of pie-eating, and given the American people "particular fits" for their addiction to it. Now, while I fully endorse all I ever heard said on the subject, I beg leave to remark that the Americans are not the worst offenders in this way. If you want to see pastry, come to Constantinople: seeing will satisfy you—you won't risk a taste. Mutton is largely eaten, and the mutton fat is used with flour to make the crust, which is so rich that the grease fairly oozes out and "smells to Heaven." Meat-pies are in great demand. The crust is baked alone in a round flat piece, and laid out on a counter, which is soon very greasy, ready to be filled. A large dish of hash is also ready, and when a customer calls the requisite amount of meat is clapped on one side of the paste, the other half doubled over it, and he departs eating his halfmoon-shaped pie. On the counters you see displayed large egg-shaped forms of what look like layers of tallow and cooked meat, cheesy-looking cakes of many kinds and an endless variety of confectionery. The sweetmeats are perfection, the fresh Turkish paste with almonds in it melts in your mouth, and the sherbet, compounded of the juice of many fruits and flowers and cooled with snow, is the most delicious drink I ever tasted. There are also many kinds of nice sweet-cakes; but, on the whole, I should prefer not to board in a Turkish family or employ a Turkish cook. No wonder the women are pale and sallow if they indulge much in such food!

Being anxious to see a good display of Turkish rugs, and our party having some commissions to execute, we sallied forth one afternoon on this errand. If you intend to visit a Turkish carpet warehouse, and your purse or your judgment counsels you not to purchase, put yourself under bonds to that effect before you go; for, unless you possess remarkable strength of character, the beautiful rugs displayed will prove irresistible temptations. Near the bazaar in Stamboul is a massive square stone house, looking like a fortress compared with the buildings around it. Mosses and weeds crop out of every uneven part of its walls. A heavy door that might stand a siege admitted us to a small vestibule, and from this we passed into a paved court with a moss-grown fountain in the centre. Around this court ran a gallery, its heavy arches and columns supporting a second, to which we ascended by a broad flight of steps. A double door admitted us to the wareroom, where, tolerably secure from fire (the doors alone were of wood), were stored Turkish and Persian rugs of all [pg 670] sizes and colors. The Turkish were far handsomer than the Persian, and the colors more brilliant than those I have usually seen. The attendants unrolled one that they said was a hundred years old. It had a dusty, faded look, as if it had been in the warehouse quite that length of time, and made the modern ones seem brighter by contrast. Several rugs having been selected, we returned to the office, where a carpet was spread and we were invited to seat ourselves on it. Coffee was passed around, and we proceeded to bargain for our goods through our interpreter. The merchant, as usual, asked an exorbitant price to start with, and we offered what was equally ridiculous the other way; and so we gradually approached the final price—he coming gracefully down, and we as affably ascending in the scale, till a happy medium was reached, and we departed with our purchases following us on the back of an ammale.

Three days of each week are observed as holy days. Friday is the Turkish Sabbath, Saturday the Jewish, and the Greeks and Armenians keep Sunday. The indolent government officials, glad of an excuse to be idle, keep all three—that is, they refrain from business—so there are only four days out of the seven in which anything is accomplished.

One of the great sights is to see the sultan go to the mosque; so one Friday we took a caïque and were rowed up the Bosphorus to Dolma Backté, and waited on the water opposite the palace. The sultan's caïque was at the principal entrance on the water-side of the palace, and the steps and marble pavement were carpeted from the caïque to the door. Presently all the richly-dressed officers of the household, who were loitering around, formed on either side the steps, and, bending nearly double, remained so while the sultan passed down to his caïque. Abdul Assiz is quite stout and rather short, with a pleasant face and closely-cut beard. He was dressed in a plain black uniform, his breast covered with orders. The sultan's caïque was a magnificent barge—white, profusely ornamented with gilt, and rowed by twenty-four oarsmen dressed in white, who rose to their feet with each stroke, bowed low, and settled back in their seats as the stroke was expended. The sultan and grand vizier seated themselves under the plum-colored velvet canopy, and the caïque proceeded swiftly toward the mosque, followed by three other caïques with his attendants. A gun from an iron-clad opposite the palace announced that the sultan had started. The shore from the palace to the mosque was lined with soldiers; the bands played; the people cheered; the ships ran up their flags; all the war-vessels were gay with bunting, had their yards manned and fired salutes, which were answered by the shore-batteries. The mosque selected for that day's devotions was in Tophaneh, near the water. Several regiments were drawn up to receive the sultan, and an elegant carriage and a superb Arab saddle-horse were in waiting, so that His Majesty might return to the palace as best suited his fancy. After an hour spent in devotion the sultan reappeared, and entering his carriage was driven away. We saw [pg 671] him again on our way home, when he stopped to call on an Austrian prince staying at the legation. The street leading up to the embassy was too narrow and steep for a carriage, so, mounting his horse at the foot, he rode up, passing very close to us.

In the afternoon we drove to the "Sweet Waters of Europe" to see the Turkish ladies, who in pleasant weather always go out there in carriages or by water in caïques. Compared with our parks, with their lovely lakes and streams and beautiful lawns, the far-famed Sweet Waters of Europe are only fields with a canal running through them; but here, where this is the only stream of fresh water near the city, and in a country destitute of trees, it is a charming place. The stream has been walled up to the top of its banks, which are from three to six feet above the water, and there are sunny meadows and fine large trees on each side. The sultan has a summer palace here with a pretty garden, and the stream has been dammed up by blocks of white marble cut in scallops like shells, over which the water falls in a cascade. The road to the Sweet Waters, with one or two others, was made after the sultan's return from his European trip, and in anticipation of the empress Eugénie's visit. European carriages were also introduced at that time. The ladies of the sultan's harem drive out in very handsome coupés, with coachmen wearing the sultan's livery, but you more frequently see the queer one-horse Turkish carriage, and sometimes a "cow-carriage." This last is drawn by cows or oxen: it is an open wagon, with a white cloth awning ornamented with gay fringes and tassels. Many people go in caïques, and all carry bright-colored rugs, which they spread on the grass. There they sit for several hours and gossip with each other, or take their luncheons and spend the afternoon. A Turkish woman is never seen to better advantage than when "made up" for such an excursion. Her house-dress is always hidden by a large cloak, which comes down to the ground and has loose sleeves and a cape. The cloak is left open at the neck to show the lace and necklace worn under it, and is generally made of silk, often of exquisite shades of pink, blue, purple or any color to suit the taste of the wearer. A small silk cap, like the low turbans our ladies wore eight or nine years ago, covers the head, and on it are fastened the most brilliant jewels—diamond pins, rubies, anything that will flash. The wearer's complexion is heightened to great brilliancy by toilet arts, and over all, covering deficiencies, is the yashmak or thin white veil, which conceals only in part and greatly enhances her beauty. You think your "dream of fair women" realized, and go home and read Lalla Rookh and rave of Eastern peris. Should some female friend who has visited a harem and seen these radiant beauties face to face mildly suggest that paint, powder and the enchantment of distance have in a measure deluded you, you dismiss the unwelcome information as an invention of the "green-eyed monster," and, remembering the brilliant beauties who reclined beside the Sweet Waters or floated by you on the Golden Horn, cherish the recollection as that of one of the brightest scenes of the Orient.

These I have spoken of are the upper classes from the harems of the sultan and rich pashas, but those you see constantly on foot in the streets are the middle and lower classes, and not so attractive. They have fine eyes, but the yashmaks are thicker, and you feel there is less beauty hidden under them. The higher the rank the thinner the yashmak is the rule. They also wear the long cloak, but it is made of black or colored alpaca or a similar material. Gray is most worn, but black, brown, yellow, green, blue and scarlet are often seen. The negresses dress like their mistresses in the street, and if you see a pair of bright yellow boots under a brilliant scarlet ferraja and an unusually white yashmak, you will generally find the wearer is a jet-black negress. Sitting so much in the house à la Turque is not conducive to grace of motion, nor are loose slippers to well-shaped feet, and I must confess that a Turkish woman walks like a goose, and the size of her "fairy feet" would rejoice the heart of a leather-dealer.

We have been to see the Howling Dervishes, and I will endeavor to give you some idea of their performances. Crossing to Scutari in the steam ferryboat, we walked some distance till we reached the mosque, where the services were just commencing. The attendant who admitted us intimated that we must remove our boots and put on the slippers provided. N—— did so, but I objected, and the man was satisfied with my wearing them over my boots. We were conducted up a steep, ladder-like staircase to a small gallery, with a low front only a foot high, with no seats but sheepskins on the floor, where we were expected to curl ourselves up in Turkish fashion. Both my slippers came off during my climb up stairs, and were rescued in their downward career by N——, who by dint of much shuffling managed to keep his on. Below us were seated some thirty or forty dervishes. The leader repeated portions of the Koran, in which exercise others occasionally took part in a quiet manner. After a while they knelt in line opposite their leader and began to chant in louder tones, occasionally bowing forward full length. Matters down below progressed slowly at first, and were getting monotonous. One of my feet, unaccustomed to its novel position, had gone to sleep, and I was in a cramped state generally. Moreover, we were not the sole occupants of the gallery: the sheepskins were full of them, and I began to think that if the dervishes did not soon begin to howl, I should. Some traveler has said that on the coast of Syria the Arabs have a proverb that the "sultan of fleas holds his court in Jaffa, and the grand vizier in Cairo." Certainly some very [pg 673] high dignitary of the realm presides over Constantinople, and makes his head-quarters in the mosque of the Howling Dervishes.

The dervishes now stood up in line, taking hold of hands, and swayed backward, forward and sideways, with perfect uniformity, wildly chanting, or rather howling, verses of the Koran, and keeping time with their movements. They commenced slowly, and increased the rapidity of their gymnastics as they became more excited and devout. The whole performance lasted an hour or more, and at the end they naturally seemed quite exhausted. Then little children were brought in, laid on the floor, and the head-dervish stepped on their bodies. I suppose he stepped in such a manner as not to hurt them, as they did not utter a sound. Perhaps the breath was so squeezed out of them that they could not. One child was quite a baby, and on this he rested his foot lightly, leaning his weight on a man's shoulder. I could not find out exactly what this ceremony signified, but was told it was considered a cure for sickness, and also a preventive.

We concluded to do the dervishes, and so next day went to see the spinning ones. They have a much larger and handsomer mosque than their howling brethren. First they chanted, then they indulged in a "walk around." Every time they passed the leader, who kept his place at the head of the room, they bowed profoundly to him, then passed before him, and, turning on the other side, bowed again. After this interchange of courtesies had lasted a while, they sailed off around the room, spinning with the smooth, even motion of a top—arms folded, head on one side and eyes shut. Sometimes this would be varied by the head being thrown back and the arms extended. The rapid whirling caused their long green dresses to spread out like a half-open Japanese umbrella, supposing the man to be the stick, and they kept it up about thirty minutes to the inspiring music of what sounded like a drum, horn and tin pan. We remained to witness the first set: whether they had any more and wound up with the German, I cannot say. We were tired and went home, satisfied with what we had seen. I should think they corresponded somewhat with our Shakers at home, as far as their "muscular Christianity" goes, and are rather ahead on the dancing question.

[pg 674] One of the prominent objects of interest on the Bosphorus is Roberts College. It stands on a high hill three hundred feet above the water, and commands an extensive view up and down the Bosphorus. For seven years Dr. Hamlin vainly endeavored to obtain permission to build it, and the order was not given till Farragut's visit. The gallant admiral, while breakfasting with the grand vizier, inquired what was the reason the government did not allow Dr. Hamlin to build the college, when the grand vizier hastily assured him that all obstacles had been removed, and that the order was even then as good as given. Americans may well be proud of so fine and well-arranged a building and the able corps of professors. We visited it in company with Dr. Wood and his agreeable wife, who are so well known to all who take any interest in our foreign missions. After going over the college and listening to very creditable declamations in English from some of the students, we were hospitably entertained at luncheon by Professor Washburn, who is in charge of the institution, and his accomplished wife. Within a short distance of the college is the Castle of Europe, and on the opposite side of the Bosphorus the Castle of Asia. They were built by Mohammed II. in 1451, and the Castle of Europe is still in good preservation. It consists of two large towers and several small ones connected by walls, and is built of a rough white stone, to which the ivy clings luxuriantly.

A pleasant excursion is to take a little steamer, which runs up the Bosphorus and back, touching at Beicos (Bey Kos), and visit the Giant Mountain, from which is a magnificent view of the Black Sea and nearly the whole length of the Bosphorus. We breakfasted early, but when ready to start found our guide had disappointed us, and his place was not to be supplied. The day was perfect, and rather than give up our trip we determined to go by ourselves, trusting that the success which had attended similar expeditions without a commissionnaire would not desert us on this occasion. The sail up on the steamer was charming. There are many villages on the shores of the Bosphorus, and between them are scattered palaces and summer residences, the latter often reminding us of Venetian houses, built directly on the shore with steps down to the water, and caïques moored at the doors, as the gondolas are in Venice. The houses are surrounded by beautiful gardens, with a profusion of flowers blooming on the very edge of the shore, their gay colors reflected in the waves beneath.