Title: The Nursery, Volume 17, No. 101, May, 1875

Author: Various

Release date: December 13, 2004 [eBook #14335]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Charles Aldarondo, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Nursery, Volume 17, No. 101, May, 1875, by Various

| No. 101. | MAY, 1875. | Vol. XVII. |

THENURSERYA Monthly MagazineFOR YOUNGEST READERS.BOSTON:

|

|

| $1.60 a Year, in advance, Postage Included. | A single copy, 15 cts. |

| PAGE | ||

| EDITOR'S PORTFOLIO. | 128 | |

| THE DOG WHO LOST HIS MASTER | By Uncle Charles | 129 |

| ON A HIGH HORSE | By Josephine Pollard | 132 |

| CELEBRATING GRANDMOTHER'S BIRTHDAY | By Emily Carter | 133 |

| THE LITTLE CULPRIT | (From the German) | 136 |

| THE DOLL-BABY SHOW | By George Cooper | 138 |

| THE CHICKENS THAT WERE WISER THAN LOTTIE | By Ruth Kenyon | 140 |

| A HUNT FOR BOY BLUE | By A.L.T | 142 |

| A DRAWING-LESSON | 145 | |

| DAY AND NIGHT | By Aunt Winnie | 146 |

| VIEW FROM COOPER'S HILL | By E.W. | 147 |

| SATURDAY NIGHT | By Uncle Charles | 148 |

| THE CUCKOO | By Uncle Oscar | 150 |

| WORK AND SING! | By Emily Carter | 152 |

| ONE YEAR OLD | By A.B.C. | 153 |

| MY DOG | By Willie B. Marshall | 156 |

| MAY | 157 | |

| DOT AND THE LEMONS | By G. | 158 |

| DADDY DANDELION | (Music by T. Crampton) | 160 |

We think that the present number, both in its pictorial and its literary contents, will please our host of readers, young and old. The charming little story of "The Little Culprit," in its mixture of humor and pathos, has been rarely excelled.

The drawing lessons, consisting of outlines made by Weir from Landseer's pictures, seem to be fully appreciated by our young readers, and we have received from them several copies which are very creditable.

Remember that for teaching children to read there are no more attractive volumes than "The Easy Book" and "The Beautiful Book," published at this office.

The pleasant days of spring ought to remind canvassers that now is a good time for getting subscribers, and that "The Nursery" needs but to be shown to intelligent parents to be appreciated. See terms.

The use of "The Nursery" in schools has been attended with the best results. We have much interesting testimony on this point, which we may soon communicate. It will be worthy the attention of teachers and school committees.

Subscribers who do not receive "THE NURSERY" promptly, (making due allowance for the ordinary delay of the mail), are requested to notify us IMMEDIATELY. Don't wait two or three months and then write informing us that we have "not sent" the magazine, (which in most cases is not the fact): but state simply that you have not RECEIVED it; and be sure, in the first place, that the fault is not at your own Post-office. Always mention the DATE of your remittance and subscription as nearly as possible. Remember that WE are not responsible for the short-comings of the Post-office, and that our delivery of the magazine is complete when we drop it into the Boston office properly directed.

"Every house that has children in it, needs 'The Nursery' for their profit and delight: and every childless house needs it for the sweet portraiture it gives of childhood."—Northampton Journal.

pot was a little dog who had come all the way from Chicago to Boston,

in the cars with his master. But, as they were about to take the cars

back to their home, they entered a shop near the railroad-station; and

there, before Spot could get out to follow his master, a bad boy shut

the door, and kept the poor dog a prisoner.

pot was a little dog who had come all the way from Chicago to Boston,

in the cars with his master. But, as they were about to take the cars

back to their home, they entered a shop near the railroad-station; and

there, before Spot could get out to follow his master, a bad boy shut

the door, and kept the poor dog a prisoner.

The cars were just going to start. In vain did the master call "Spot, Spot!" In vain did poor Spot bark and whine, and scratch at the door, and plead to be let out of the shop. The bad boy kept him there till just as the bell rang; and then he opened the door, and poor Spot ran—oh, so fast!—but the cars moved faster than he.

Mile after mile poor Spot followed the cars, till they were far out of sight. Then, panting and tired, he stopped by the roadside, and wondered what he should do, without a home, without a master.

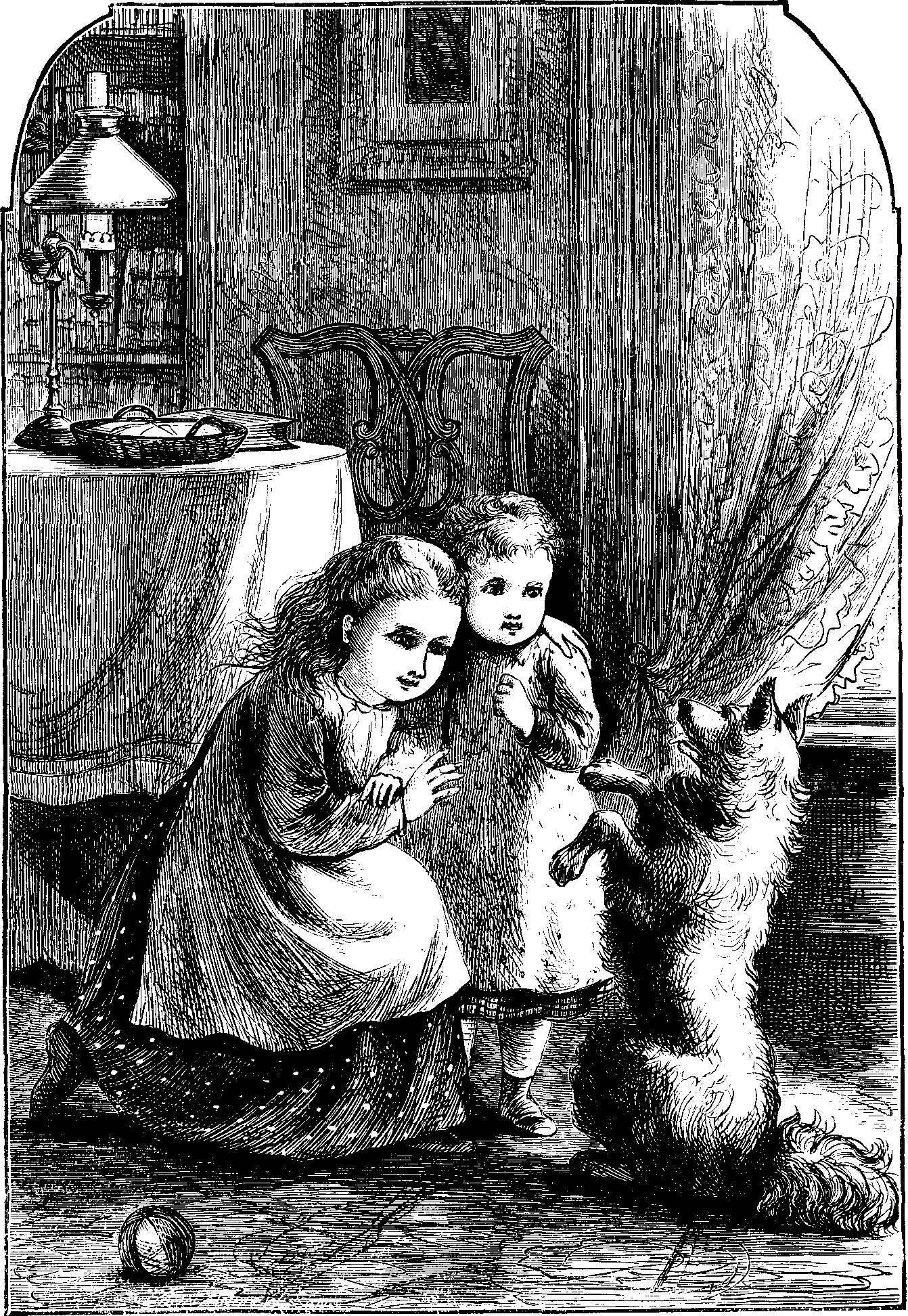

He had not rested many minutes, when he saw two little girls coming along the road that crossed the iron track. They were Nelly and Julia, two sisters. Spot thought he would try and make friends with them.

But they were afraid of strange dogs. Julia began to cry; and Nelly said, "Go away, sir; go home, sir: we don't want any thing to do with you, sir."

Spot was sorry to be thus driven off. He stopped, and began to whine in a pleading sort of way, as if saying, "I am a good dog, though a stranger to you. I have lost my master, and I am very hungry. Please let me follow you. I'll be very good. I know tricks that will please you."

The children were not so much afraid when they saw him stop as if to get permission to follow. "He is a good dog, after all," said Nelly: "he would not force his company on us; he wants his dinner. Come on, sir!"

Thus encouraged, Spot ran up, wagging his tail, and showing that he was very glad to find a friend. He barked at other dogs who came too near, and showed that he meant to defend the little girls at all risks.

When they arrived home, they gave him some milk and bread, and then took him into the sitting-room, and played with him. "Beg, sir!" said Nelly; and at once Spot stood upright on his hind-legs, and put out his fore-paws.

Then Julia rolled a ball along the floor; and Spot caught it almost before it left her hand. "Now, die, sir, die!" cried Nelly; and, much to her surprise, Spot lay down on the floor, and acted as if he were dead.

When papa came home, and saw what a good, wise dog Spot was, he told the children they might keep him till they could find the owner.

A week afterwards, they saw at the railroad-station a printed bill offering a reward of thirty dollars for Spot.

He was restored at once to his master, who proved to be a Mr. Walldorf, a German. But the little girls refused the offered reward; for they said they did not deserve it, and Spot had been no trouble to them.

Three weeks passed by, and then there came a box from New York, directed to Nelly and Julia. They opened it: and there were two beautiful French dolls, and two nice large dolls' trunks filled with dolls' dresses and bonnets,—dresses for morning and evening, for opera and ball-room, for the street and the parlor, for riding and walking.

The present was from Mr. Walldorf; and with it came a letter from him thanking the little girls for their kindness to his good dog, Spot, and promising to bring Spot to see them the next time he visited Boston.

There were three little sisters and one little brother; and their names were Emma, Ruth, Linda, and John. And these children had a grandmother, whose seventieth birthday was near at hand.

"What shall we do to celebrate our dear grandmother's birthday?" asked Emma, the eldest.

"Get some crackers and torpedoes, and fire them off," said Johnny.

"Oh, that will never do!" cried Linda. "Let us give her a serenade."

"But we none of us sing well enough," said Ruth; "and grandmother, you know, is a very good musician. Let us do this: Let us come to her as the 'Four Seasons,' and each one salute her with a verse."

"Yes: that's a very pretty idea," cried Linda. "And I'll be Spring; for they say my eyes are blue as violets."

"Then I'll be Summer," cried Emma. "I like summer best."

"I'll be Autumn," said Johnny; "for, if there's any thing I like, it is grapes. Peaches, too, are not bad; and what fun it is to go a-nutting!"

"There's but one season left for me," said Ruth. "I must be Winter. No matter! Winter has its joys as well as the rest."

"But who'll write the verses for us?" asked Emma. "There must be a verse for every season."

"Oh, the teacher will write them for us!" cried Ruth. "No one could do it better."

And so, on the morning of grandmother's birthday, as she sat in her large armchair, with her own pussy on a stool at her side, the "Four Seasons" entered the room, one after another, and formed a semicircle in front of her. Grandmother was not a bit frightened. She smiled kindly; and then the "Seasons" spoke as follows:—

School had begun. The boys and girls were in their places, and the master was hearing them spell; when all at once there was a soft, low knock at the door.

"Come in!" said the master; and a little cleanly-dressed girl, about six years old, stood upon the threshold, with downcast eyes.

She held out before her, as if trying to hide behind it, a satchel, so large that it seemed hard to decide whether the child had brought it, or it had brought the child; and the drops on her cheeks showed how she had been running.

"Why, Katie!" cried the schoolmaster, "why do you come so late? Come here to me, little culprit. It is the first time you have been late. What does it mean?"

Little Katie slowly approached him, while her chubby face grew scarlet. "I—I had to pick berries," she faltered, biting her berry-stained lips.

"O Katie!" said the master, raising his forefinger, "that is very strange. You had to? Who, then, told you to?"

Katie still looked down; and her face grew redder still.

"Look me in the face, my child," said the master gravely. "Are you telling the truth?"

Katie tried to raise her brown roguish eyes to his face: but, ah! the consciousness of guilt weighed down her eyelids like lead. She could not look at her teacher: she only shook her curly head.

"Katie," said the master kindly, "you were not sent to pick berries: you ran into the woods to pick them for yourself. Perhaps this is your first falsehood, as it is the first time you have been late at school. Pray God that it may be your last."

"Oh, oh!" broke forth the little culprit, "the neighbor's boy, Fritz, took me with him; and the berries tasted so good that I staid too long."

The other children laughed; but a motion of the master's hand restored silence, and, turning to Katie, he said, "Now, my child, for your tardiness you will have a black mark, and go down one in your class; but, Katie, for the falsehood you will lose your place in my heart, and I cannot love you so much. But I will forgive you, if you will go stand in the corner of your own accord. Which will you do,—lose your place in my heart, or go stand in the corner for a quarter of an hour?"

The child burst into a flood of tears, and sobbing out, "I'd rather go stand in the corner," went there instantly, and turned her dear little face to the wall.

In a few minutes the master called her, and, as she came running to him, he said: "Will you promise me, Katie, never again to say what is not true?"

"Oh, yes, I will try—I will try never, never to do it again," was the contrite answer.

Then the master took up the rosy little thing, and set her on his knee, and said: "Now, my dear child, I will love you dearly. And, if you are ever tempted to say what is not true, think how it would grieve your old teacher if he knew it, and speak the truth for his sake."

"Yes, yes!" cried the child, her little heart overflowing with repentance; and, throwing her arms around the master's neck, she hugged him, and said again, "Yes, yes!"

Lottie is always asking, "Why?"

When mamma calls from the window, "Lottie, Lottie!" she answers, very pleasantly, "What, ma'am?" for she hopes mamma will say, "Here's a nice turnover for you;" or, "Cousin Alice has come to see you." But when the answer is "It is time to come in," the wrinkles appear on Lottie's forehead, and her voice is a very different one, as she says, "Oh, dear, I don't want to! Why need I come in now?"

When papa says, "Little daughter, I want you to do an errand for me," Lottie whines, and asks, "Why can't Benny do it?"

Out in the field Old Biddy Brown has four wee chickens, little soft downy balls, scarcely bigger than the eggs they came from just one week ago.

They are very spry, and run all about. When the mother Biddy finds any nice bit, she clucks; and every little chick comes running to see what is wanting.

When it grows chilly, and she fears they will take cold, she says, "Cluck, cluck, cluck!" and they all run under her warm feathers as fast as they can.

Just now Mother Biddy gave a very loud call, and every chicken was under her wings in a minute; and up in the sky I saw a hawk, who had been planning to make a good dinner of these same chickens. I could not help thinking, how well for them, that they did not stop, like Lottie, to ask, "Why?"

Down came the hawk with a fierce swoop, as if he meant to take the old hen and the chickens too; but Mother Biddy sprang up and faced him so boldly, that he did not know what to make of it.

She seemed to say, "Come on my fine fellow, if you dare. You have got to eat me before you eat my chicks; and you'll find me rather tough."

So the hawk changed his mind at the last moment. He thought he would wait till he could catch the chickens alone. The chickens were saved, though one of them was nearly dead with fright.

We have a little three-year-old boy at our house, who likes to hear stories, and his mother tells him a great many. But there is one which pleases him more than all the rest, and perhaps the little readers of "The Nursery" will like it too.

You have all heard of little Boy Blue, and how he was called upon to blow his horn; but I don't think any of you know what a search his father had to find him. This is the story.

Boy Blue lived on a large farm, and took care of the sheep and cows. One day the cows got into the corn, and the sheep into the meadow; and Boy Blue was nowhere to be seen. His father called and called, "Boy Blue, Boy Blue, where are you? Why do you not look after the sheep and cows? Where are you?" But no one answered.

Then Boy Blue's father went to the pasture, and said, "Horse, horse, have you seen Boy Blue?" The old horse pricked up his cars, and looked very thoughtful, but neighed, and said, "No, no: I have not seen Boy Blue."

Next he went to the field where the oxen were ploughing, and said, "Oxen, oxen, have you seen Boy Blue?" They rolled their great eyes, and looked at him; but shook their heads, and said, "No, no: we have not seen Boy Blue."

Next, he went to the pond; and a great fat duck came out to meet him; and he said, "Duck, duck, have you seen Boy Blue?" And she said, "Quack, quack, quack! I have not seen Boy Blue." And all the other ducks said, "Quack, quack!"

Then Boy Blue's father visited the turkeys, and asked the old gobbler if he had seen Boy Blue. The old gobbler strutted up and down, saying, "Gobble, gobble, gobble! I have not seen Boy Blue."

He then asked the cockerel if he had seen Boy Blue. And the cockerel answered, "Cock-coo-doodle-doo! I haven't seen Boy Blue: cock-coo-doodle-doo!"

Then an old hen was asked if she had seen Boy Blue. She said, "Cluck, cluck, cluck! I haven't seen Boy Blue; but I will call my chicks, and you can ask them. Cluck, cluck, cluck!" And all the chicks came running, but only said, "Peep, peep, peep! We haven't seen Boy Blue. Peep, peep, peep!"

Boy Blue's father then went to the men who were making hay, and said, "Men, men, have you seen my Boy Blue?" But the men answered, "No, no: we have not seen Boy Blue." But just then they happened to look under a haycock; and there, all curled up, lay Boy Blue, and his dog Tray, fast asleep.

His father shook him by the arm, saying, "Boy Blue, wake up, wake up! The sheep are in the meadow, and the cows are in the corn." Boy Blue sprang to his feet, seized his tin horn, and ran as fast as he could to the cornfield, with his little dog running by his side.

He blew on his horn, "Toot, toot, toot!" and all the cows came running up, saying, "Moo, moo!" He drove them to the barn to be milked. Then he ran to the meadows, and blew once more, "Toot, toot, toot!" and all the sheep came running up, saying, "Baa, baa!" and he drove them to their pasture.

Then Boy Blue said to his dog, "Little dog, little dog, it's time for supper," and his little dog said "Bow, wow! Bow, wow!" So they went home to supper.

After Boy Blue had eaten a nice bowl of bread and milk, his father said: "Now Boy Blue, you had better go to bed, and have a good night's rest, so that you may be able to keep awake all day to-morrow; for I don't want to have such a hunt for you again." Then Boy Blue said, "Good night," and went to bed, and slept sweetly all night long.

Blue-eyed Charley Day had a cousin near his own age, whose name was Harry Knight. When they were about eight years old, and began to go to the public school, the boys called them, "Day and Night."

Charley did not object to the puns the schoolboys made; but Harry was quite vexed by them. Having quite a dark skin, and very dark eyes and hair, he thought the boys meant to insult him by calling him, "Night."

One large boy, about twelve years old, seemed to delight in teasing Harry. He would say to him, "Come here, 'Night,' and shade my eyes, the day is so bright." Then, seeing that Harry was annoyed, he would say, "Oh, what a dark night!"

Poor Harry would get angry, and that made matters worse; for then Tom Smith would call him a "stormy night," or a "cloudy night," or the "blackest night" he ever saw.

Harry talked with his mother about it; and she told him the best way would be to join with the boys in their jokes, or else not notice them at all. She said if he never got out of temper, the boys would not call him any thing worse than a "bright starry night." And if he went through the world with as good a name as that she should be perfectly satisfied.

"Don't take offence at trifles, Harry," said Mrs. Knight. "Don't be teased by a little nonsense. All the fun that the boys can make out of your name will not hurt you a bit."

Harry was wise enough to do as his mother advised, and he found that she was right. The boys soon became tired of their jokes, when they found that no one was disturbed by them. But the little cousins were alway good-naturedly called "Day and Night."

When grandma was a little girl, she lived in England, where she was born. She lived in the town of Windsor, twenty-three miles south-west of London, the greatest city in the world.

Grandma showed us, the other day, this picture of a view from Cooper's Hill, near Windsor, and said, "Many a time and oft, dear children, have I stood there by the old fence, and looked down on the beautiful prospect,—the winding Thames, the gardens, the fields, and Windsor Castle in the distance.

"This noble structure was originally built by William the Conqueror, as far back as the eleventh century. It has been embellished by most of the succeeding kings and queens. It is the principal residence of Queen Victoria in our day. The great park, not far distant, has a circuit of eighteen miles; and west from the park is Windsor Forest, having a circuit of fifty-six miles.

"It is many a year since I saw these places. I cannot expect to visit them again; but this picture brings them vividly before me.

"And so, dear children, should you ever go to England, don't forget to go to Cooper's Hill, and, for grandma's sake, to look round upon the charming prospect which she loved so much when a child."

Bring on the boots and shoes, Tommy; for this is Saturday night, and I must make things clean for Sunday.

Here is my old jacket, to begin with. Whack, whack, whack! As I beat it with my stick, how the dust flies!

The jacket looks a little the worse for wear; and that patch in the elbow is more for show than use. But it is a good warm jacket still, and mother says that next Christmas I shall have a new one.

Whack, whack, whack! I wish Christmas was not so far off. If somebody would make me a present now of a handsome new jacket, without a patch in it, I should take it as an especial kindness. I do hate to wear patched clothes.

Stop there, Master Frank! You deserve to be beaten, instead of your jacket. Look in the glass at your fat figure and rosy checks. Are you not well fed and well taken care of? Is not good health better than fine clothes? Are you the one to complain?

Ah, Frank! Just look at poor Tim Morris, as he goes by in his carriage. See his fine rich clothes, and his new glossy hat. But see, too, how pale and thin he looks. How gladly would he put on your patched jacket, and give you his new one, if he could have your health!

Whack, whack, whack! I'm an ungrateful boy. I'll not complain again. Christmas may be as long as it pleases in coming. I'll tell mother she mustn't pinch herself to buy me a new jacket. I'll tell her this one will serve me a long time yet; that I have got used to it, and like it. It will look almost as good as new when I get the dust out of it. Whack, whack, whack!

"Tell me what bird this is a picture of," said Arthur.

"That," said Uncle Oscar, "is the cuckoo, a bird which arrives in England, generally, about the middle of April, and departs late in June, or early in July."

"Why does it go so early?" asked Arthur.

"Well, I think it is because it likes a warm climate; and, as soon as autumn draws near, it wants to go back to the woods of Northern Africa."

"Why is it called the cuckoo?"

"Because the male bird utters a call-note which sounds just like the word kuk-oo. In almost every language, this sound has suggested the name of the bird. In Greek, it is kokkux; in Latin, coccyx; in French, coucou; in German, kukuk."

"What does the bird feed on?" asked Arthur.

"It feeds on soft insects, hairy caterpillars, and tender fruits."

"Where does it build its nest?"

"The cuckoo, I am sorry to say, is not a very honest bird. Instead of taking the trouble to build a nest for herself, the female bird lays her eggs in the nest of other birds, and to them commits the care of hatching and rearing her offspring."

"I should not call that acting like a good parent," said Arthur. "Do the other birds take care of these young ones that are not their own?"

"Oh, yes! they not only take care of them and feed them for weeks, but sometimes they even let the greedy young cuckoos push their own children out of the nest."

"That's a hard case," said Arthur. "Is there any American bird that acts like the cuckoo?"

"Oh, yes!" said Uncle Oscar. "There is a little bird called the 'cow-bunting,' about as large as a canary-bird: she, too, makes other birds hatch her young and take care of them."

"I don't like such lazy behavior. Did you ever hear the note of the cuckoo?" said Arthur.

"Oh, yes!" replied Uncle Oscar. "I have heard it in England; and there, too, I have heard the skylark and the nightingale, neither of which birds we have in America. But we have the mocking-bird, one of the most wonderful of song-birds."

"I wonder if the cuckoo would not live in America," said Arthur. "I should like to get one and try it. I would take good care of it."

"It would not thrive in this climate, Arthur."

WORK AND SING!

You must work, and I must sing, That's the way the birdies do: See the workers on the wing; See the idle singers too.

Yet not wholly idle these, They the toilers do not wrong; For the weary heart they ease With the rapture of their song.

If our work of life to cheer We no music had, no flowers, Life would hardly seem so dear, Longer then would drag the hours.

Like the birdies let us be; Let us not the singers chide; There's a use in all we see: Work and sing! the world is wide. |

Hold her up, mamma, and let us all have a look at her. Is she not a dear little thing?

She is not a bit afraid, but only puzzled at being stared at by so many people. She does not know what to make of it.

She clutches at her mother's chin, as much as to say, "Tell me what this means."

[Pg 154]It means, baby, that you are one year old. This is your birthday, and we have come to call on you.

But here is Jane, the nurse. Has she come to take you away from us? We are not ready to part with you.

[Pg 155]You want to go with her? Well, that is too bad! You like her better than you do me. I must see what she does that makes you so fond of her.

She takes you to the barn, and shows you the horse and the cow. Then she lets you look out of the barn-window. There you spy the kitten.

The kitten sees you, and jumps up on the basket, and looks in your face. You put out your little hand, and try to reach her.

Jane has the pig and the chickens to show you yet. But I cannot stay any longer. I must leave you playing with the kitten.

I have a dog, and his name is Don. He is nine years old. His master is in Boston, and I call Don my dog, because I like to have him here. He is a black-and-white dog, and measures six feet in length, and about two feet in height.

When I go on errands, Don takes the basket or pail, and trots away to the store; and sometimes I have to pull him, or he will go the wrong way.

He is a lazy old fellow, and he likes to sleep almost all the time, except when he is asked if he wants to go anywhere; and then he frisks around, and seems as if he had never been asleep.

When he wants a drink, he goes around to the store-room door, and asks for it by looking up in our faces; and I dare say he would say, if he could speak, "Please give me a drink?"

I have a little brother, and he sits on my dog a good deal. And I have a cousin of whom the dog is very fond and when she is at the table, he will put his paw on her lap, and want her to take it.

My little baby-brother tumbles over the dog, and sits on him; and sometimes when I am tired, I lie down and take a nap with my head on Don's back. He likes to have me do it, and he always keeps watch while I am asleep.

Dot's father is a funny man. One night, he brought home some lemons for mamma,—twelve long, fat, yellow lemons, in a bag. Dot was sitting at the piano with mamma when his father came in, and did not run, as usual, to greet him with a kiss. So Dot's father opened the bag, and let the lemons drop one by one, and roll all over the floor.

Then Dot looked around, and cried, "Lemons, lemons! Get down; Dot get down!" And he ran and picked up the lemons one by one, and put them all together in the great black arm-chair. As he picked them up, he counted them: "One, two, three, five, six, seven, nine, ten!"

When Dot got tired of seeing them on the chair, he began to put them on the floor again, one at a time, and all in one spot. While he was doing this, his father stooped down, and when the little boy's back was turned, took the lemons, slily from the spot where Dot was placing them, and put them behind his own back,—some behind his right foot, and some behind his left.

He took only a few of them at first, so that Dot should not miss them. But, when Dot came to put the last lemon on the floor, he could not see any thing of the others, and was very much surprised. Then mamma, grandmamma, and grandpapa all burst out laughing. His father stepped aside, and there Dot saw the lemons in two rows.

Then father said, "That was only a joke. Now, Dot, put them back again on the chair—quick!" And Dot ran and began to take away the lemons from the first row, and lay them on the black cushion of grandpapa's great arm-chair, one by one. One—two—three—four—five: he had only one more lemon to pick up from the first row; but when he came for it—my! there were two.

Well, to tell the truth, Dot didn't notice this at first. He picked up one of the two, and thought to himself, "Only one left, Dot." But, I declare! there were two left when he came back. "This is a long row," thought Dot. And every time he left one, he found two, till papa had quite used up the second row, from which he had been filling up the first.

At last Dot did see the last lemon, and then again he didn't see it, for when he looked for it, it wasn't two, as before, it wasn't there at all!

"O papa! you have it behind you; and Dot will pull at your hand till you give up the lemon; and then you can't play any more tricks with your bright little boy."

But Dot will go up to bed with Alice, and in the middle of the night mamma will hear him saying in his sleep, "Five, six, nine, 'lemon!" For Dot always says 'lemon, when he means eleven.

Words by T. Hood. Music by T. Crampton

Allegretto. mf

Good Commissions or valuable premiums are given to agents for three first-class union religious papers and one agricultural monthly. Canvassers are making excellent wages. Agents wanted. Send for sample copy and terms. Address,

will not subscribe

THE RURAL HOME from April 4th to January, but

will, since the subscription for that period—THIRTY-NINE WEEKS—will cost him only

Specimens free. Address

Rochester, N.Y.

A book by which children can teach themselves to read, with but little help from parent or teacher.

The most beautiful Primer in the market. Containing upwards of a hundred fine pictures. 96 Pages of the size of The Nursery. The word-system of teaching explained and applied.

36 Bromfield Street, Boston.

Any of the following articles will be sent by mail, postpaid, on receipt of the price named, viz:—

The Kindergarten Alphabet and Building Blocks, PAINTED: PRICE

Roman Alphabets, large and small letters, numerals, and animals, .75

" " " 1.00

" " " 1.50

Crandall's Acrobat or Circus Blocks, with which hundreds of queer, fantastic

figures may be formed by any child, 1.15

Table-Croquet. This can be used on any table—making a Croquet-Board, at

trifling expense 1.50

Game of Bible Characters and Events .50

Dissected Map of the United States 1.00

Boys and Girls Writing-Desk 1.00

Initial Note-Paper and Envelopes 1.00

Game of Punch And Judy 1.00

BOOKS will be sent postpaid, also, at publishers prices. Send orders and remittances to

[Pg 162]CONSTANTINES PINE TAR SOAP For Toilet, Bath and Nursery Cures Diseases of Skin and Scalp and Mucous Coating. Sold by Druggists and Grocers.

FRAGRANT SOZODONT

Is a composition of the purest and choicest ingredients of the vegetable kingdom. It cleanses, beautifies, and preserves the TEETH, hardens and invigorates the gums, and cools and refreshes the mouth. Every ingredient of this Balsamic dentifrice has a beneficial effect on the Teeth and Gums. Impure Breath, caused by neglected teeth, catarrh, tobacco, or spirits, is not only neutralized, but rendered fragrant, by the daily use of SOZODONT. It is as harmless as water, and has been indorsed by the most scientific men of the day.

Sold by all Druggists, at 75 cents.

Tells who want agents, and what for. 8 page monthly, 10c. a year postpaid. Jas. P. Scott, 125 Clark-st., Chicago.

ILLUSTRATED SPRING CATALOGUE FOR 1875. NOW READY.

Sent, with a specimen copy of THE AMERICAN GARDEN, a new Illustrated Journal of Garden Art, edited by James Hogg, on receipt of ten cents.

BEACH, SON & CO., Seedsmen, 76 Fulton St., Brooklyn, N.Y.

Each, number is complete, and everybody likes it. Gives a weekly record of the world's doings. In its columns will be found a choice variety of Gems in every department of Literature, of interest to the general reader. Its contents embrace the best Stories, Tales of Adventure, Thrilling Deeds, Startling Episodes, Sketches of Home and Social Life, Sketches of Travel, Instructive Papers on Science and Art, Interesting Articles on Agriculture, Horticulture, Gardening and Housekeeping, Choice Poetry, Essays, Correspondence, Anecdotes, Wit and Humor, Valuable Recipes, Market Reviews, Items of Interesting and Condensed Miscellany. Free from Sectarianism, there is always something to please all classes of readers, both grave and gay.

As a Family Paper, it has merits that no similar publication possesses. The large amount and great variety of popular and valuable reading matter in each number is not excelled by any other paper.

Sample 6 cents; with two chromos, 25 cents. $2 a year. Try it three months for 50 cents. Say where you saw this. Value and satisfaction guaranteed. More agents and subscribers wanted everywhere.

Both one year, postpaid, for $2.25.

Address L.W. MAUCK, Cheshire, Ohio.

30 FANCY CALLING CARDS, 9 styles, 20 cts. with names, or 40 Blank Scroll Cards 5 designs and colors 20 cts. Outfit 19 styles 10 cts. Address J.B. HUSTED, Nassau, Kens Co., N.Y.

$57.60 Agents' Profits per week. Will prove it or forfeit $500. New articles are just patented. Samples sent free to all. Address W.H. CHIDESTER, 267 Broadway, N.Y.

FREE Sample copy of CHEAPEST PAPER IN AMERICA! Eight large pages, (Ledger size.) Monthly; only 50 cents a year. Choice Reading, Nice Premiums. AGENTS WANTED. LITERARY REPORTER, Quincy, Mich.

The most elaborate work of the kind, contains an "Alphabetical Index of Representative words, such as are liable to be misspelled or mispronounced."

These words are not technical absurdities, such as no one uses, but honest useful words, which every scholar ought to know.

No better collection to test spellers at the matches now in vogue can be found.

Price 32 cents, postpaid. Published by

Send 15 cents, and get 20 varieties by mail. C.W. JENCKS & BRO., Providence, R.I.

For three new subscribers, at $1.60 each, we will give any one of the following articles: a heavily-plated gold pencil-case, a rubber pencil-case with gold tips, silver fruit-knife, a pen-knife, a beautiful wallet, any book worth $1.50. For five, at $1.60 each, any one of the following: globe microscope, silver fruit-knife, silver napkin-ring, book or books worth $2.50. For six, at $1.60 each, we will give any one of the following: a silver fruit-knife (marked), silver napkin-ring, pen-knives, scissors, backgammon-board, note-paper and envelopes stamped with initials, books worth $3.00. For ten, at $1.60 each, select any one of the following: morocco travelling-bag, stereoscope with six views, silver napkin-ring, compound microscope, lady's work-box, sheet-music or books worth $5.00. For twenty, at $1.60 each, select any one of the following: a fine croquet-set, a powerful opera-glass, a toilet case, Webster's Dictionary (unabridged), sheet-music or books worth $10.00.

Any other articles equally easy to transport may be selected as premiums, their value being in proportion to the number of subscribers sent. Thus, we will give for three new subscribers, at $1.60 each, a premium worth $1.50; for four, a premium worth $2.00; for five, a premium worth $2.50; and so on.

BOOKS for premiums may be selected from any publisher's catalogue; and we can always supply them at catalogue prices. Under this offer, subscriptions to any periodical or newspaper are included.

BOOKS.—For two new subscribers, at $1.60 each, we will give any half-yearly volume of THE NURSERY; for three, any yearly volume; for two, OXFORD'S JUNIOR SPEAKER; for two, THE EASY BOOK; for two, THE BEAUTIFUL BOOK; for three, OXFORD'S SENIOR SPEAKER; for three, SARGENT'S ORIGINAL DIALOGUES; for three, an elegant edition of SHAKSPEARE, complete in one volume, full cloth, extra gilt, and gilt-edged; or any one of the standard BRITISH POETS, in the same style. GLOBES.—For two new subscribers, we will give a beautiful GLOBE three inches in diameter; for three, a GLOBE four inches in diameter; for five, a GLOBE six inches in diameter. PRANG'S CHROMOS will be given as premiums at the publisher's prices. Send stamp for a catalogue. GAMES, &c.—For two new subscribers, we will give any one of the following: The Checkered Game of Life, Alphabet and Building Blocks, Dissected Maps, &c., &c. For three new subscribers, any one of the following: Japanese Backgammon or Kakeba, Alphabet and Building Blocks (extra). Croquet, Chivalrie, Ring Quoits, and any other of the popular games of the day may be obtained on the most favorable terms, by working for THE NURSERY. Send stamp to us for descriptive circulars.

Either of these large and superbly executed steel engravings will be sent, postpaid, as a premium for three new subscribers at $1.60 each.

Do not wait to make up the whole list before sending. Send the subscriptions as you get them, stating that they are to go to your credit for a premium; and, when your list is completed, select your premium, and it will be forthcoming.

Take notice that our offers of premiums apply only to subscriptions paid at the full price: viz., $1.60 a year. We do not offer premiums for subscriptions supplied at club-rates. We offer no premiums for one subscription only. We offer no premiums in money.

SUBSCRIPTIONS,—$1.60 a year, in advance. Three copies for 4.30 a year; four for $5.40; five for $6.50; six for $7.60: seven fur $8.70; eight for $9.80; nine for $10.90; each additional copy for $1.20; twenty copies for $22.00, always in advance.

POSTAGE is included in the above rates. All magazines are sent postpaid.

A SINGLE NUMBER will be mailed for 15 cents. One sample number will be mailed for 10 cents.

VOLUMES begin with January and July. Subscriptions may commence with any month, but, unless the time is specified, will date from the beginning of the current volume.

BACK NUMBERS can always be supplied. The Magazine commenced January, 1867.

BOUND VOLUMES, each containing the numbers for six months, will be sent by mail, postpaid, for $1.00 per volume; yearly volumes for $1.75.

COVERS, for half-yearly volume, postpaid, 35 cents; covers for yearly volume, 40 cents,

PRICES OF BINDING.—In the regular half-yearly volume, 40 cents; in one yearly volume (12 Nos. in one), 50 cents. If the volumes are to be returned by mail, add 14 cents for the half-yearly, and 22 cents for the yearly volume, to pay postage.

REMITTANCES may be made at our risk, if made by check, or money-order.

(ALL POSTPAID.)

| Scribner's Monthly | $4.00, and The Nursery, | $4.75 |

| Harper's Monthly | 4.00, and The Nursery, | 4.75 |

| Harper's Weekly | 4.00, and The Nursery, | 4.75 |

| Harper's Bazar | 4.00, and The Nursery, | 4.75 |

| Atlantic Monthly | 4.00, and The Nursery, | 4.75 |

| Galaxy | 4.00, and The Nursery, | 4.75 |

| Old and New | 4.00, and The Nursery, | 4.75 |

| Lippincott's Magazine | 4.00, and The Nursery, | 4.75 |

| Appleton's Journal | 4.00, and The Nursery, | 4.75 |

| Living Age | 8.00, and The Nursery, | 9.00 |

| Phrenological Journal | 3.10, and The Nursery, | 4.00 |

| The Science of Health | 2.00, and The Nursery, | 3.10 |

| The Sanitarian | 3.00, and The Nursery, | 4.00 |

| St. Nicholas | $3.00, and The Nursery, | $4.00 |

| The Household | 1.00, and The Nursery, | 2.20 |

| Mother's Journal | 2.00, and The Nursery, | 3.25 |

| Demorest's Monthly | 3.10, and The Nursery, | 4.25 |

| Little Corporal | 1.50, and The Nursery, | 2.70 |

| Leslie's Illustrated | 4.00, and The Nursery, | 4.75 |

| Optic's Magazine | 3.00, and The Nursery, | 4.25 |

| Lady's Journal | 4.00, and The Nursery, | 4.75 |

| Godey's Lady's Book | 3.00, and The Nursery, | 4.00 |

| Hearth and Home | 3.00, and The Nursery, | 4.00 |

| Young People's Mag. | 1.50, and The Nursery, | 2.70 |

| The Horticulturist | 2.10, and The Nursery, | 3.20 |

| Ladies Floral Cabinet | 1.30, and The Nursery, | 2.60 |

N.B.—When any of these Magazines is desired in club with "The Nursery" at the above rates, both Magazines must be subscribed for at the same time; but they need not be to the same address. We furnish our own Magazine, and agree to pay the subscription for the other. Beyond this we take no responsibility. The publisher of each Magazine is responsible for its prompt delivery; and complaints must be addressed accordingly.

The number of the Magazine with which your subscription expires is indicated by the number annexed to the address on the printed label. When no such number appears, it will be understood that the subscription ends with the current year. No notice of discontinuance need be given, as the Magazine is never sent after the term of subscription expires. Subscribers will oblige us by sending their renewals promptly. State always that your payment is for a renewal, when such is the fact. In changing the direction, the old as well as the new address should be given. The sending of "The Nursery" will be regarded as a sufficient receipt.