President Li Yuan-Hung.

Title: The Fight for the Republic in China

Author: B. L. Putnam Weale

Release date: December 13, 2004 [eBook #14345]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Jonathan Ingram and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (https://www.pgdp.net)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Fight For The Republic in China, by Bertram Lenox Putnam Weale

This volume tells everything that the student or the casual reader needs to know about the Chinese Question. It is sufficiently exhaustive to show very clearly the new forces at work, and to bring some realisation of the great gulf which separates the thinking classes of to-day from the men of a few years ago; whilst, at the same time, it is sufficiently condensed not to overwhelm the reader with too great a multitude of facts.

Particular attention may be devoted to an unique feature—namely, the Chinese and Japanese documentation which affords a sharp contrast between varying types of Eastern brains. Thus, in the Memorandum of the Black Dragon Society (Chapter VII) we have a very clear and illuminating revelation of the Japanese political mind which has been trained to consider problems in the modern Western way, but which remains saturated with theocratic ideals in the sharpest conflict with the Twentieth Century. In the pamphlet of Yang Tu (Chapter VIII) which launched the ill-fated Monarchy Scheme and contributed so largely to the dramatic death of Yuan Shih-kai, we have an essentially Chinese mentality of the reactionary or corrupt type which expresses itself both on home and foreign issues in a naïvely dishonest way, helpful to future diplomacy. In the Letter of Protest (Chapter X) against the revival of Imperialism written by Liang Ch'i-chao—the most brilliant scholar living—we have a Chinese of the New or Liberal China, who in spite of a complete ignorance of foreign languages shows a marvellous grasp of political absolutes, and is a harbinger of the great days which must come again to Cathay. In other chapters dealing with the monarchist plot we see the official mind at work, the telegraphic despatches exchanged between Peking and the provinces being of the highest diplomatic interest. These documents prove conclusively that although the Japanese is more practical than the Chinese—and more concise—there can be no question as to which brain is the more fruitful.

Coupled with this discussion there is much matter giving an insight into the extraordinary and calamitous foreign ignorance about present-day China, an ignorance which is just as marked among those resident in the country as among those who have never visited it. The whole of the material grouped in this novel fashion should not fail to bring conviction that the Far East, with its 500 millions of people, is destined to play an important rôle in postbellum history because of the new type of modern spirit which is being there evolved. The influence of the Chinese Republic, in the opinion of the writer, cannot fail to be ultimately world-wide in view of the practically unlimited resources in man-power which it disposes of.

In the Appendices will be found every document of importance for the period under examination,—1911 to 1917. The writer desires to record his indebtedness to the columns of The Peking Gazette, a newspaper which under the brilliant editorship of Eugene Ch'en—a pure Chinese born and educated under the British flag—has fought consistently and victoriously for Liberalism and Justice and has made the Republic a reality to countless thousands who otherwise would have refused to believe in it.

PUTNAM WEALE.

PEKING, June, 1917.

I.—GENERAL INTRODUCTION

II.—THE ENIGMA OF YUAN SHIH-KAI

III.—THE DREAM REPUBLIC

(From the Manchu Abdication to the dissolution of Parliament)

IV.—THE DICTATOR AT WORK

(From the Coup d'état of the 4th Nov. 1913 to the outbreak of the

World-war, 1st August, 1914)

V.—THE FACTOR OF JAPAN

VI.—THE TWENTY-ONE DEMANDS

VII.—THE ORIGIN OF THE TWENTY-ONE DEMANDS

VIII.—THE MONARCHIST PLOT

1o The Pamphlet of Yang Tu

IX.—THE MONARCHY PLOT

2o Dr. Goodnow's Memorandum

X.—THE MONARCHY MOVEMENT IS OPPOSED

The Appeal of the Scholar Liang Chi-chao

XI.—THE DREAM EMPIRE

("The People's Voice" and the action of the Powers)

XII.—"THE THIRD REVOLUTION"

The Revolt of Yunnan

XIII.—"THE THIRD REVOLUTION" (continued)

Downfall and Death of Yuan Shih-kai

XIV.—THE NEW RÉGIME—FROM 1916 TO 1917

XV.—THE REPUBLIC IN COLLISION WITH REALITY: TWO TYPICAL INSTANCES OF

"FOREIGN AGGRESSION"

XVI.—CHINA AND THE WAR

XVII.—THE FINAL PROBLEM:—REMODELLING THE POLITICO-ECONOMIC

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CHINA AND THE WORLD

APPENDICES—DOCUMENTS AND MEMORANDA

The Provincial Troops of General Chang Hsun at his Headquarters of Hsuchowfu

The Funeral of Yuan Shih-kai: The Catafalque over the Coffin on its way to the Railway Station

A Manchu Country Fair: The figures in the foreground are all Manchu Women and Girls

Silk-reeling done in the open under the Walls of Peking

Modern Peking: A Run on a Bank

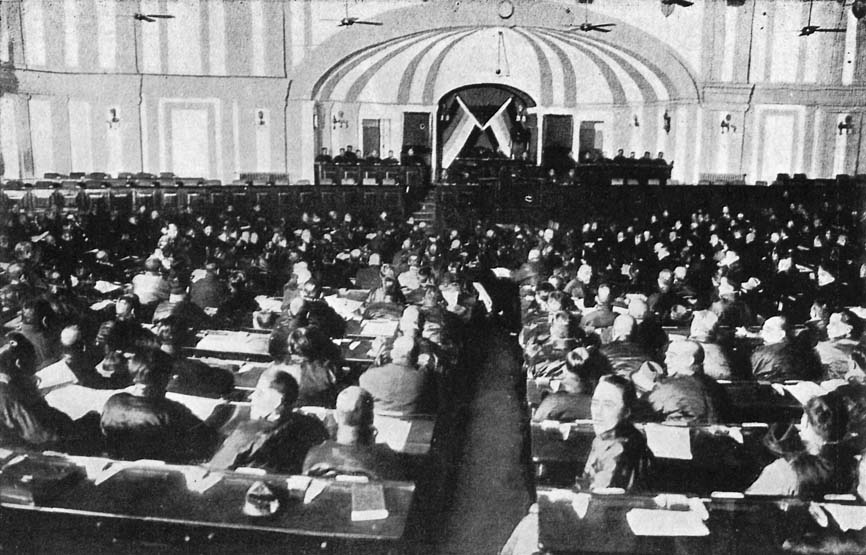

The Re-opening of Parliament on August 1st, 1916, after three years of dictatorial rule

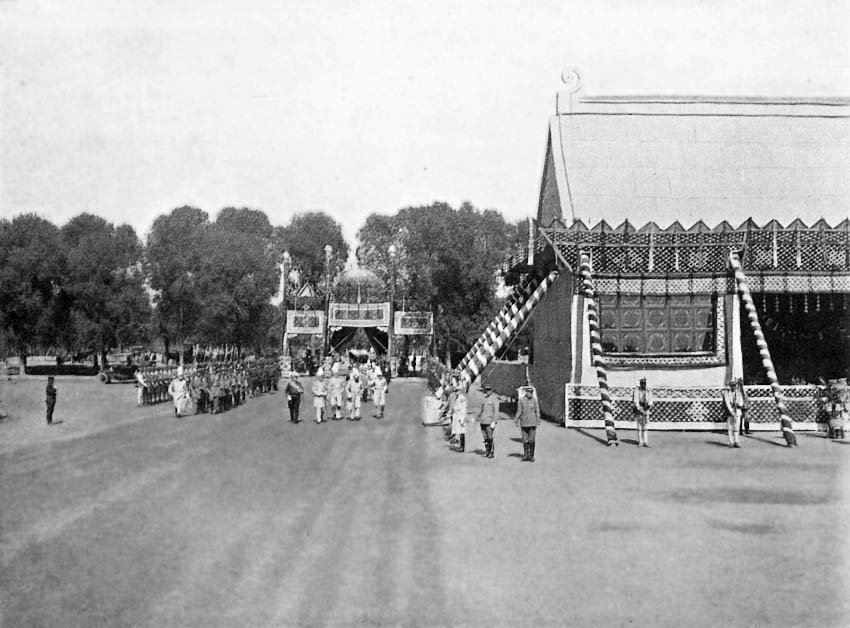

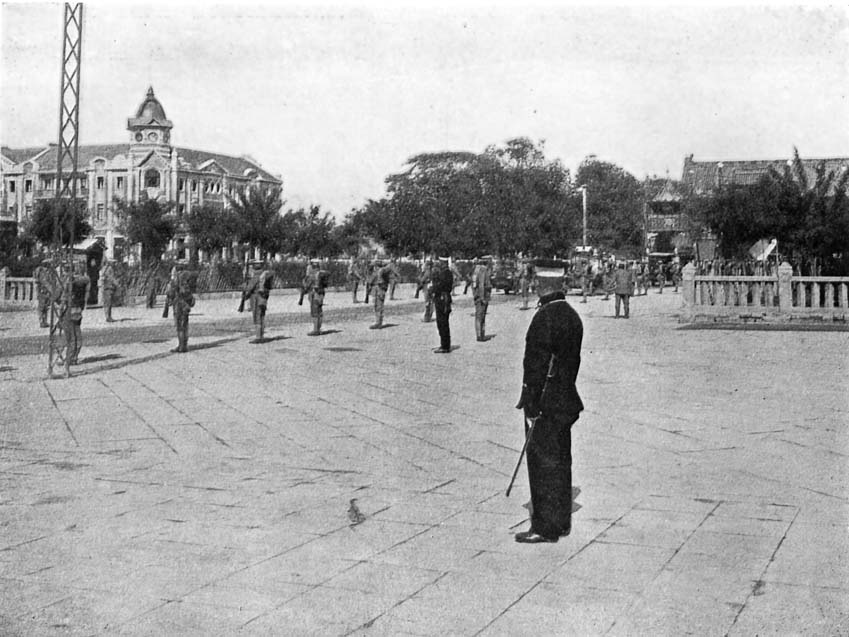

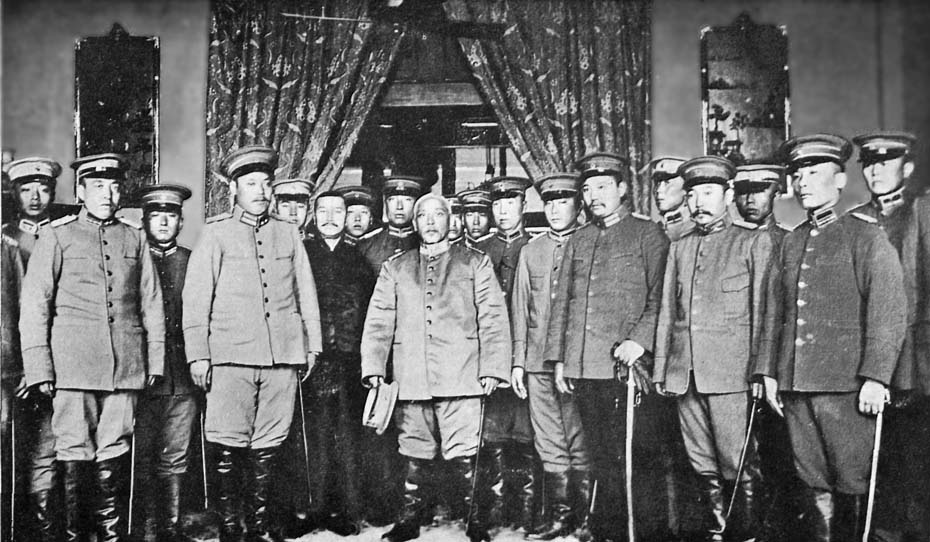

President Li Yuan-Hung and the General Staff watching the Review

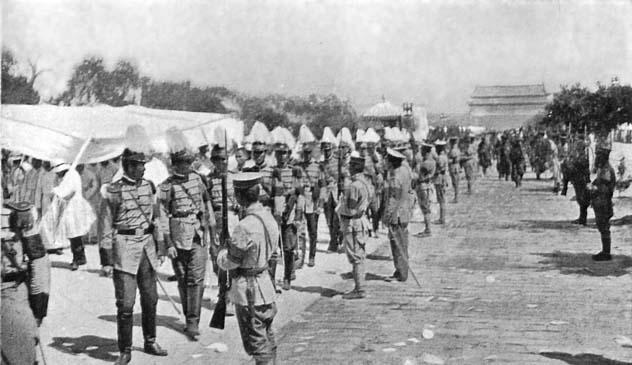

March-past of an Infantry Division

The Premier General Tuan Chi-Jui, Head of the Cabinet which decided to declare war on Germany.

General Feng Kuo-chang, President of the Republic.

The Scholar Liang Chi-chao, sometime Minister of Justice, and the foremost "Brain" in China

The Bas-relief in a Peking Temple, well illustrating Indo-Chinese Influences

The Late President Yuan Shih-kai

The revolution which broke out in China on the 10th October, 1911, and which was completed with the abdication of the Manchu Dynasty on the 12th February, 1912, though acclaimed as highly successful, was in its practical aspects something very different. With the proclamation of the Republic, the fiction of autocratic rule had truly enough vanished; yet the tradition survived and with it sufficient of the essential machinery of Imperialism to defeat the nominal victors until the death of Yuan Shih-kai.

The movement to expel the Manchus, who had seized the Dragon Throne in 1644 from the expiring Ming Dynasty, was an old one. Historians are silent on the subject of the various secret plots which were always being hatched to achieve that end, their silence being due to a lack of proper records and to the difficulty of establishing the simple truth in a country where rumour reigns supreme. But there is little doubt that the famous Ko-lao-hui, a Secret Society with its headquarters in the remote province of Szechuan, owed its origin to the last of the Ming adherents, who after waging a desperate guerilla warfare from the date of their expulsion from Peking, finally fell to the low level of inciting assassinations and general unrest in the vain hope that they might some day regain their heritage. 2 At least, we know one thing definitely: that the attempt on the life of the Emperor Chia Ching in the Peking streets at the beginning of the Nineteenth Century was a Secret Society plot and brought to an abrupt end the pleasant habit of travelling among their subjects which the great Manchu Emperors K'ang-hsi and Ch'ien Lung had inaugurated and always pursued and which had so largely encouraged the growth of personal loyalty to a foreign House.

From that day onwards for over a century no Emperor ventured out from behind the frowning Walls of the Forbidden City, save for brief annual ceremonies, such as the Worship of Heaven on the occasion of the Winter Solstice, and during the two "flights"—first in 1860 when Peking was occupied by an Anglo-French expedition and the Court incontinently sought sanctuary in the mountain Palaces of Jehol; and, again, in 1900, when with the pricking of the Boxer bubble and the arrival of the International relief armies, the Imperial Household was forced along the stony road to far-off Hsianfu.

The effect of this immurement was soon visible; the Manchu rule, which was emphatically a rule of the sword, was rapidly so weakened that the emperors became no more than rois fainéants at the mercy of their minister.[1] The history of the Nineteenth Century is thus logically enough the history of successive collapses. Not only did overseas foreigners openly thunder at the gateways of the empire and force an ingress, but native rebellions were constant and common. Leaving minor disturbances out 3 of account, there were during this period two huge Mahommedan rebellions, besides the cataclysmic Taiping rising which lasted ten years and is supposed to have destroyed the unbelievable total of one hundred million persons. The empire, torn by internecine warfare, surrendered many of its essential prerogatives to foreigners, and by accepting the principle of extraterritoriality prepared the road to ultimate collapse.

How in such circumstances was it possible to keep alive absolutism? The answer is so curious that we must be explicit and exhaustive.

The simple truth is that save during the period of vigour immediately following each foreign conquest (such as the Mongol conquest in the Thirteenth Century and the Manchu in the Seventeenth) not only has there never been any absolutism properly so-called in China, but that apart from the most meagre and inefficient tax-collecting and some rough-and-ready policing in and around the cities there has never been any true governing at all save what the people did for themselves or what they demanded of the officials as a protection against one another. Any one who doubts these statements has no inkling of those facts which are the crown as well as the foundation of the Chinese group-system, and which must be patiently studied in the village-life of the country to be fitly appreciated. To be quite frank, absolutism is a myth coming down from the days of Kublai Khan when he so proudly built his Khanbaligh (the Cambaluc of Marco Polo and the forebear of modern Peking) and filled it with his troops who so soon vanished like the snows of winter. An elaborate pretence, a deliberate policy of make-believe, ever since those days invested Imperial Edicts with a majesty which they have never really possessed, the effacement of the sovereign during the Nineteenth Century contributing to the legend that there existed in the capital a Grand and Fearful Panjandrum for whom no miracle was too great and to whom people and officials owed trembling obedience.

In reality, the office of Emperor was never more than a politico-religious concept, translated for the benefit of the masses into socio-economic ordinances. These pronouncements, cast in the form of periodic homilies called Edicts, were the ritual of government; their purpose was instructional rather than mandatory; 4 they were designed to teach and keep alive the State-theory that the Emperor was the High Priest of the Nation and that obedience to the morality of the Golden Age, which had been inculcated by all the philosophers since Confucius and Mencius flourished twenty-five centuries ago, would not only secure universal happiness but contribute to national greatness.

The office of Emperor was thus heavenly rather than terrestrial, and suasion, not arms, was the most potent argument used in everyday life. The amazing reply (i.e., amazing to foreigners) made by the great Emperor K'ang-hsi in the tremendous Eighteenth Century controversy between the Jesuit and the Dominican missionaries, which ruined the prospects of China's ever becoming Roman Catholic and which the Pope refused to accept—that the custom of ancestor-worship was political and not religious—was absolutely correct, politics in China under the Empire being only a system of national control exercised by inculcating obedience to forebears. The great efforts which the Manchus made from the end of the Sixteenth Century (when they were still a small Manchurian Principality striving for the succession to the Dragon Throne and launching desperate attacks on the Great Wall of China) to receive from the Dalai Lama, as well as from the lesser Pontiffs of Tibet and Mongolia, high-sounding religious titles, prove conclusively that dignities other than mere possession of the Throne were held necessary to give solidity to a reign which began in militarism and which would collapse as the Mongol rule had collapsed by a mere Palace revolution unless an effective moral title were somehow won.

Nor was the Manchu military Conquest, even after they had entered Peking, so complete as has been represented by historians. The Manchus were too small a handful, even with their Mongol and Chinese auxiliaries, to do more than defeat the Ming armies and obtain the submission of the chief cities of China. It is well-known to students of their administrative methods, that whilst they reigned over China they ruled only in company with the Chinese, the system in force being a dual control which, beginning on the Grand Council and in the various great Boards and Departments in the capital, proceeded as far as the provincial chief cities, but stopped short there so completely and absolutely that the huge chains of villages and burgs had their historic 5 autonomy virtually untouched and lived on as they had always lived. The elaborate system of examinations, with the splendid official honours reserved for successful students which was adopted by the Dynasty, not only conciliated Chinese society but provided a vast body of men whose interest lay in maintaining the new conquest; and thus Literature, which had always been the door to preferment, became not only one of the instruments of government, but actually the advocate of an alien rule. With their persons and properties safe, and their women-folk protected by an elaborate set of capitulations from being requisitioned for the harems of the invaders, small wonder if the mass of Chinese welcomed a firm administration after the frightful disorders which had torn the country during the last days of the Mings.[2]

It was the foreigner, arriving in force in China after the capture of Peking and the ratification of the Tientsin Treaties in 1860, who so greatly contributed to making the false idea of Manchu absolutism current throughout the world; and in this work it was the foreign diplomat, coming to the capital saturated with the tradition of European absolutism, who played a not unimportant part. Investing the Emperors with an authority with which they were never really clothed, save for ceremonial purposes (principally perhaps because the Court was entirely withdrawn from view and very insolent in its foreign intercourse) a conception of High Mightiness was spread abroad reminiscent of the awe in which Eighteenth Century nabobs spoke of the Great Mogul of India. Chinese officials, quickly discovering that their easiest means of defence against an irresistible pressure was to take refuge behind the august name of the sovereign, played their rôle so successfully that until 1900 it was generally believed by Europeans that no other form of government than a despotism sans phrase could be dreamed of. Finding that on the surface an Imperial Decree enjoyed the majesty of an Ukaze of the Czar, Europeans were ready enough to interpret as best suited their enterprises something which they entirely failed to construe in terms expressive of the negative nature of Chinese civilization; and so it 6 happened that though the government of China had become no government at all from the moment that extraterritoriality destroyed the theory of Imperial inviolability and infallibility, the miracle of turning state negativism into an active governing element continued to work after a fashion because of the disguise which the immense distances afforded.

Adequately to explain the philosophy of distance in China, and what it has meant historically, would require a whole volume to itself; but it is sufficient for our purpose to indicate here certain prime essentials. The old Chinese were so entrenched in their vastnesses that without the play of forces which were supernatural to them, i.e., the steam-engine, the telegraph, the armoured war-vessel, etc., their daily lives could not be affected. Left to themselves, and assisted by their own methods, they knew that blows struck across the immense roadless spaces were so diminished in strength, by the time they reached the spot aimed at, that they became a mere mockery of force; and, just because they were so valueless, paved the way to effective compromises. Being adepts in the art which modern surgeons have adopted, of leaving wounds as far as possible to heal themselves, they trusted to time and to nature to solve political differences which western countries boldly attacked on very different principles. Nor were they wrong in their view. From the capital to the Yangtsze Valley (which is the heart of the country), is 800 miles, that is far more than the mileage between Paris and Berlin. From Peking to Canton is 1,400 miles along a hard and difficult route; the journey to Yunnan by the Yangtsze river is upwards of 2,000 miles, a distance greater than the greatest march ever undertaken by Napoleon. And when one speaks of the Outer Dominions—Mongolia, Tibet, Turkestan—for these hundreds of miles it is necessary to substitute thousands, and add thereto difficulties of terrain which would have disheartened even Roman Generals.

Now the old Chinese, accepting distance as the supreme thing, had made it the starting-point as well as the end of their government. In the perfected viceregal system which grew up under the Ming Dynasty, and which was taken over by the Manchus as a sound and admirable governing principle, though they superimposed their own military system of Tartar Generals, we have 7 the plan that nullified the great obstacle. Authority of every kind was delegated by the Throne to various distant governing centuries in a most complete and sweeping manner, each group of provinces, united under a viceroy, being in everything but name so many independent linked commonwealths, called upon for matricular contributions in money and grain but otherwise left severely alone [3]. The chain which bound provincial China to the metropolitan government was therefore in the last analysis finance and nothing but finance; and if the system broke down in 1911 it was because financial reform—to discount the new forces of which the steam engine was the symbol—had been attempted, like military reform, both too late and in the wrong way, and instead of strengthening, had vastly weakened the authority of the Throne.

In pursuance of the reform-plan which became popular after the Boxer Settlement had allowed the court to return to Peking from Hsianfu, the viceroys found their most essential prerogative, which was the control of the provincial purse, largely taken from them and handed over to Financial Commissioners who were directly responsible to the Peking Ministry of Finance, a Department which was attempting to replace the loose system of matricular contributions by the European system of a directly controlled taxation every penny of which would be shown in an annual Budget. No doubt had time been vouchsafed, and had European help been enlisted on a large scale, this change could ultimately have been made successful. But it was precisely time which was lacking; and the Manchus consequently paid the 8 penalty which is always paid by those who delay until it is too late. The old theories having been openly abandoned, it needed only the promise of a Parliament completely to destroy the dignity of the Son of Heaven, and to leave the viceroys as mere hostages in the hands of rebels. A few short weeks of rebellion was sufficient in 1911 to cause the provinces to revert to their condition of the earlier centuries when they had been vast unfettered agricultural communities. And once they had tasted the joys of this new independence, it was impossible to conceive of their becoming "obedient" again.

Here another word of explanation is necessary to show clearly the precise meaning of regionalism in China.

What had originally created each province was the chief city in each region, such cities necessarily being the walled repositories of all increment. Greedy of territory to enhance their wealth, and jealous of their power, these provincial capitals throughout the ages had left no stone unturned to extend their influence in every possible direction and bring under their economic control as much land as possible, a fact which is abundantly proved by the highly diversified system of weights and measures throughout the land deliberately drawn-up to serve as economic barriers. River-courses, mountain-ranges, climate and soil, no doubt assisted in governing this expansion, but commercial and financial greed was the principal force. Of this we have an exceedingly interesting and conclusive illustration in the struggle still proceeding between the three Manchurian provinces, Fengtien, Kirin and Heilungchiang, to seize the lion's share of the virgin land of Eastern Inner Mongolia which has an "open frontier" of rolling prairies. Having the strongest provincial capital—Moukden—it has been Fengtien province which has encroached on the Mongolian grasslands to such an extent that its jurisdiction to-day envelops the entire western flank of Kirin province (as can be seen in the latest Chinese maps) in the form of a salamander, effectively preventing the latter province from controlling territory that geographically belongs to it. In the same way in the land-settlement which is still going on the Mongolian plateau immediately above Peking, much of what should be Shansi territory has been added to the metropolitan province of Chihli. Though adjustments of provincial boundaries 9 have been summarily made in times past, in the main the considerations we have indicated have been the dominant factors in determining the area of each unit.

Now in many provinces where settlement is age-old, the regionalism which results from great distances and bad communications has been greatly increased by race-admixture. Canton province, which was largely settled by Chinese adventurers sailing down the coast from the Yangtsze and intermarrying with Annamese and the older autochthonous races, has a population-mass possessing very distinct characteristics, which sharply conflict with Northern traits. Fuhkien province is not only as diversified but speaks a dialect which is virtually a foreign language. And so on North and West of the Yangtsze it is the same story, temperamental differences of the highest political importance being everywhere in evidence and leading to perpetual bickerings and jealousies. For although Chinese civilization resembles in one great particular the Mahommedan religion, in that it accepts without question all adherents irrespective of racial origin, politically the effect of this regionalism has been such that up to very recent times the Central Government has been almost as much a foreign government in the eyes of many provinces as the government of Japan. Money alone formed the bond of union; so long as questions of taxation were not involved, Peking was as far removed from daily life as the planet Mars.

As we are now able to see very clearly, fifty years ago—that is at the time of the Taiping Rebellion—the old power and spell of the National Capital as a military centre had really vanished. Though in ancient days horsemen armed with bows and lances could sweep like a tornado over the land, levelling everything save the walled cities, in the Nineteenth Century such methods had become impossible. Mongolia and Manchuria had also ceased to be inexhaustible reservoirs of warlike men; the more adjacent portions had become commercialized; whilst the outer regions had sunk to depopulated graziers' lands. The Government, after the collapse of the Rebellion, being greatly impoverished, had openly fallen to balancing province against province and personality against personality, hoping that by some means it would be able to regain its prestige and a portion of its former 10wealth. Taking down the ledgers containing the lists of provincial contributions, the mandarins of Peking completely revised every schedule, redistributed every weight, and saw to it that the matricular levies should fall in such a way as to be crushing. The new taxation, likin, which, like the income-tax in England, is in origin purely a war-tax, by gripping inter-provincial commerce by the throat and rudely controlling it by the barrier-system, was suddenly disclosed as a new and excellent way of making felt the menaced sovereignty of the Manchus; and though the system was plainly a two-edged weapon, the first edge to cut was the Imperial edge; that is largely why for several decades after the Taipings China was relatively quiet.

Time was also giving birth to another important development—important in the sense that it was to prove finally decisive. It would have been impossible for Peking, unless men of outstanding genius had been living, to have foreseen that not only had the real bases of government now become entirely economic control, but that the very moment that control faltered the central government of China would openly and absolutely cease to be any government at all. Modern commercialism, already invading China at many points through the medium of the treaty-ports, was a force which in the long run could not be denied. Every year that passed tended to emphasize the fact that modern conditions were cutting Peking more and more adrift from the real centres of power—the economic centres which, with the single exception of Tientsin, lie from 800 to 1,500 miles away. It was these centres that were developing revolutionary ideas—i.e., ideas at variance with the Socio-economic principles on which the old Chinese commonwealth had been slowly built up, and which foreign dynasties such as the Mongol and the Manchu had never touched. The Government of the post-Taiping period still imagined that by making their hands lie more heavily than ever on the people and by tightening the taxation control—not by true creative work—they could rehabilitate themselves.

It would take too long, and would weary the indulgence of the reader to establish in a conclusive manner this thesis which had long been a subject of inquiry on the part of political students. Chinese society, being essentially a society organized 11on a credit-co-operative system, so nicely adjusted that money, either coined or fiduciary, was not wanted save for the petty daily purchases of the people, any system which boldly clutched the financial establishments undertaking the movement of sycee (silver) from province to province for the settlement of trade-balances, was bound to be effective so long as those financial establishments remained unshaken.

The best known establishments, united in the great group known as the Shansi Bankers, being the government bankers, undertook not only all the remittances of surpluses to Peking, but controlled by an intricate pass-book system the perquisites of almost every office-holder in the empire. No sooner did an official, under the system which had grown up, receive a provincial appointment than there hastened to him a confidential clerk of one of these accommodating houses, who in the name of his employers advanced all the sums necessary for the payment of the official's post, and then proceeded with him to his province so that moiety by moiety, as taxation flowed in, advances could be paid off and the equilibrium re-established. A very intimate and far-reaching connection thus existed between provincial money-interests and the official classes. The practical work of governing China was the balancing of tax-books and native bankers' accounts. Even the "melting-houses," where sycee was "standardized" for provincial use, were the joint enterprises of officials and merchants; bargaining governing every transaction; and only when a violent break occurred in the machinery, owing to famine or rebellion, did any other force than money intervene.

There was nothing exceptional in these practices, in the use of which the old Chinese empire was merely following the precedent of the Roman Empire. The vast polity that was formed before the time of Christ by the military and commercial expansion of Rome in the Mediterranean Basin, and among the wild tribes of Northern Europe, depended very largely on the genius of Italian financiers and tax-collectors to whom the revenues were either directly "farmed," or who "assisted" precisely after the Chinese method in financing officials and local administrations, and in replenishing a central treasury which no wealth could satisfy. The Chinese phenomenon was 12therefore in no sense new; the dearth of coined money and the variety of local standards made the methods used economic necessities. The system was not in itself a bad system: its fatal quality lay in its woodenness, its lack of adaptability, and in its growing weakness in the face of foreign competition which it could never understand. Foreign competition—that was the enemy destined to achieve an overwhelming triumph and dash to ruins a hoary survival.

War with Japan sounded the first trumpet-blast which should have been heeded. In the year 1894, being faced with the necessity of finding immediately a large sum of specie for purpose of war, the native bankers proclaimed their total inability to do so, and the first great foreign loan contract was signed.[4] Little attention was attracted to what is a turning-point in Chinese history. There cannot be the slightest doubt that in 1894 the Manchus wrote the first sentences of an abdication which was only formally pronounced in 1912: they had inaugurated the financial thraldom under which China still languishes. Within a period of forty months, in order to settle the disastrous Japanese war, foreign loans amounting to nearly fifty-five million pounds were completed. This indebtedness, amounting to nearly three times the "visible" annual revenues of the country—that is, the revenues actually accounted for to Peking—was unparalleled in Chinese history. It was a gold indebtedness subject to all sorts of manipulations which no Chinese properly understood. It had special political meaning and special political consequences because the loans were virtually guaranteed by the Powers. It was a long-drawn coup d'état of a nature that all foreigners understood because it forged external chains.

13The internal significance was even greater than the external. The loans were secured on the most important "direct" revenues reaching Peking—the Customs receipts, which were concerned with the most vital function in the new economic life springing up, the steam-borne coasting and river-trade as well as the purely foreign trade. That most vital function tended consequently to become more and more hall-marked as foreign; it no longer depended in any direct sense on Peking for protection. The hypothecation of these revenues to foreigners for periods running into decades—coupled with their administration by foreigners—was such a distinct restriction of the rights of eminent domain as to amount to a partial abrogation of sovereignty.

That this was vaguely understood by the masses is now quite certain. The Boxer movement of 1900, like the great proletarian risings which occurred in Italy in the pre-Christian era as a result of the impoverishment and moral disorder brought about by Roman misgovernment, was simply a socio-economic catastrophe exhibiting itself in an unexpected form. The dying Manchu dynasty, at last in open despair, turned the revolt, insanely enough, against the foreigner—that is against those who already held the really vital portion of their sovereignty. So far from saving itself by this act, the dynasty wrote another sentence in its death-warrant. Economically the Manchus had been for years almost lost; the Boxer indemnities were the last straw. By more than doubling the burden of foreign commitments, and by placing the operation of the indemnities directly in the hands of foreign bankers by the method of monthly quotas, payable in Shanghai, the Peking Government as far back as fifteen years ago was reduced to being a government at thirty days' sight, at the mercy of any shock of events which could be protracted over a few monthly settlements. There is no denying this signal fact, which is probably the most remarkable illustration of the restrictive power of money which has ever been afforded in the history of Asia.

The phenomenon, however, was complex and we must be careful to understand its workings. A mercantile curiosity, to find the parallel for which we must go back to the Middle Ages in Europe, when "free cities" such as those of the 14Hanseatic League plentifully dotted river and coast line, served to increase the general difficulties of a situation which no one formula could adequately cover. Extraterritoriality, by creating the "treaty port" in China, had been the most powerful weapon in undermining native economics; yet at the same time it had been the agent for creating powerful new counter-balancing interests. Though the increasingly large groups of foreigners, residing under their own laws, and building up, under their own specially protected system of international exchange, a new and imposing edifice, had made the hovel-like nature of Chinese economics glaringly evident, the mercantile classes of the New China, being always quick to avail themselves of money-making devices, had not only taken shelter under this new and imposing edifice, but were rapidly extending it of their own accord. In brief, the trading Chinese were identifying themselves and their major interests with the treaty-ports; they were transferring thither their specie and their credits; making huge investments in land and properties, under the aegis of foreign flags in which they absolutely trusted. The money-interests of the country knew instinctively that the native system was doomed and that with this doom there would come many changes; these interests, in the way common to money all the world over, were insuring themselves against the inevitable.

The force of this—politically—became finally evident in 1911; and what we have said in our opening sentences should now be clear. The Chinese Revolution was an emotional rising against the Peking System because it was a bad and inefficient and retrograde system, just as much as against the Manchus, who after all had adopted purely Chinese methods and who were no more foreigners than Scotchmen or Irishmen are foreigners to-day in England. The Revolution of 1911 derived its meaning and its value—as well as its mandate—not from what it proclaimed, but for what it stood for. Historically, 1911 was the lineal descendant of 1900, which again was the offspring of the economic collapse advertised by the great foreign loans of the Japanese war, loans made necessary because the Taipings had disclosed the complete disappearance of the only raison d'être of Peking sovereignty, i.e. the old-time military power. 15The story is, therefore, clear and well-connected and so logical in its results that it has about it a finality suggesting the unrolling of the inevitable.

During the Revolution the one decisive factor was shown to be almost at once—money, nothing but money. The pinch was felt at the end of the first thirty days. Provincial remittances ceased; the Boxer quotas remained unpaid; a foreign embargo was laid upon the Customs funds. The Northern troops, raised and trained by Yuan Shih-kai, when he was Viceroy of the Metropolitan province, were, it is true, proving themselves the masters of the Yangtsze and South China troops; yet that circumstance was meaningless. Those troops were fighting for what had already proved itself a lost cause—the Peking System, as well as the Manchu dynasty. The fight turned more and more into a money-fight. It was foreign money which brought about the first truce and the transfer of the so-called republican government from Nanking to Peking. In the strictest sense of the words every phase of the settlement then arrived at was a settlement in terms of cash.[5]

Had means existed for rapidly replenishing the Chinese Treasury without having recourse to European stockmarkets (whose actions are semi-officially controlled when distant regions are involved) the Republic might have fared better. But placed almost at once through foreign dictation under a species of police-control, which while nominally derived from Western conceptions, was primarily designed to rehabilitate the semblance of the authority which had been so sensationally extinguished, the Republic remained only a dream; and the world, taught to believe that there could be no real stability until the scheme of government approximated to the conception long formed of Peking absolutism, waited patiently for the rude awakening which came with the Yuan Shih-kai coup d'état of 4th November, 1913. Thus we had this double paradox; on the one hand the Chinese people awkwardly trying to be western in a Chinese way and failing: on the other, foreign officials and foreign governments trying to be Chinese and making the confusion 16worse confounded. It was inevitable in such circumstances that the history of the past six years should have been the history of a slow tragedy, and that almost every page should be written over with the name of the man who was the selected bailiff of the Powers—Yuan Shih-kai.

The Funeral of Yuan Shih-kai: The Procession passing down the great Palace Approach, with the famous Ch'ien Men (Gate) in the distance.

The Funeral of Yuan Shih-kai: The Procession passing down the great Palace Approach, with the famous Ch'ien Men (Gate) in the distance.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] As there is a good deal of misunderstanding on the subject of the Manchus an explanatory note is useful.

The Manchu people, who belong to the Mongol or Turanian Group, number at the maximum five million souls. Their distribution at the time of the revolution of 1911 was roughly as follows: In and around Peking say two millions; in posts through China say one-half million,—or possibly three-quarters of a million; in Manchuria Proper—the home of the race—say two or two and a half millions. The fighting force was composed in this fashion: When Peking fell into their hands in 1644 as a result of a stratagem combined with dissensions among the Chinese themselves, the entire armed strength was reorganized in Eight Banners or Army Corps, each corps being composed of three racial divisions, (1) pure Manchus, (2) Mongols who had assisted in the conquest and (3) Northern Chinese who had gone over to the conquerors. These Eight Banners, each commanded by an "iron-capped" Prince, represented the authority of the Throne and had their headquarters in Peking with small garrisons throughout the provinces at various strategic centres. These garrisons had entirely ceased to have any value before the 18th Century had closed and were therefore purely ceremonial and symbolic, all the fighting being done by special Chinese corps which were raised as necessity arose.

[2] This most interesting point—the immunity of Chinese women from forced marriage with Manchus—has been far too little noticed by historians though it throws a flood of light on the sociological aspects of the Manchu conquest. Had that conquest been absolute it would have been impossible for the Chinese people to have protected their women-folk in such a significant way.

[3] A very interesting proof—and one that has never been properly exposed—of the astoundingly rationalistic principles on which the Chinese polity is founded is to be seen in the position of priesthoods in China. Unlike every other civilization in the world, at no stage of the development of the State has it been necessary for religion in China to intervene between the rulers and the ruled, saving the people from oppression. In Europe without the supernatural barrier of the Church, the position of the common people in the Middle Ages would have been intolerable, and life, and virtue totally unprotected. Buckle, in his "History of Civilization," like other extreme radicals, has failed to understand that established religions have paradoxically been most valuable because of their vast secular powers, exercised under the mask of spiritual authority. Without this ghostly restraint rulers would have been so oppressive as to have destroyed their peoples. The two greatest monuments to Chinese civilization, then consist of these twin facts; first, that the Chinese have never had the need for such supernatural restraints exercised by a privileged body, and secondly, that they are absolutely without any feeling of class or caste—prince and pauper meeting on terms of frank and humorous equality—the race thus being the only pure and untinctured democracy the world has ever known.

[4] (a) This loan was the so-called 7 per cent. Silver loan of 1894 for Shanghai Taels 10,000,000 negotiated by the Hongkong & Shanghai Bank. It was followed in 1895 by a £3,000,000 Gold 6 per cent. Loan, then by two more 6 per cent. loans for a million each in the same year, making a total of £6,635,000 sterling for the bare war-expenses. The Japanese war indemnity raised in three successive issues—from 1895 to 1898—of £16,000,000 each, added £48,000,000. Thus the Korean imbroglio cost China nearly 55 millions sterling. As the purchasing power of the sovereign is eight times larger in China than in Europe, this debt economically would mean 440 millions in England—say nearly double what the ruinous South African war cost. It is by such methods of comparison that the vital nature of the economic factor in recent Chinese history is made clear.

[5] There is no doubt that the so-called Belgian loan, £1,800,000 of which was paid over in cash at the beginning of 1912, was the instrument which brought every one to terms.

Yuan Shih-kai's career falls into two clear-cut parts, almost as if it had been specially arranged for the biographer; there is the probationary period in Korea, and the executive in North China. The first is important only because of the moulding-power which early influences exerted on the man's character; but it is interesting in another way since it affords glimpses of the sort of things which affected this leader's imagination throughout his life and finally brought him to irretrievable ruin. The second-period is choke-full of action; and over every chapter one can see the ominous point of interrogation which was finally answered in his tragic political and physical collapse.

Yuan Shih-kai's origin, without being precisely obscure, is unimportant. He came of a Honanese family who were nothing more distinguished than farmers possessing a certain amount of land, but not too much of the world's possessions. The boy probably ran wild in the field at an age when the sons of high officials and literati were already pale and anaemic from over-much study. To some such cause the man undoubtedly owed his powerful physique, his remarkable appetite, his general roughness. Native biographers state that as a youth he failed to pass his hsiu-tsai examinations—the lowest civil service degree—because he had spent too much time in riding and boxing and fencing. An uncle in official life early took charge of him; and when this relative died the young man displayed 18filial piety in accompanying the corpse back to the family graves and in otherwise manifesting grief. Through official connections a place was subsequently found for him in that public department under the Manchus which may be called the military intendancy, and it was through this branch of the civil service that he rose to power. Properly speaking Yuan Shih-kai was never an army-officer; he was a military official—his highest rank later on being that of military judge, or better, Judicial Commissioner.

Yuan Shih-kai first emerges into public view in 1882 when, as a sequel to the opening of Korea through the action of foreign Powers in forcing the then Hermit kingdom to sign commercial treaties, China began dispatching troops to Seoul. Yuan Shih-kai, with two other officers, commanding in all some 3,000 men, arrived from Shantung, where he had been in the train of a certain General Wu Chang-ching, and now encamped in the Korean capital nominally to preserve order, but in reality, to enforce the claims of the suzerain power. For the Peking Government had never retreated from the position that Korea had been a vassal state ever since the Ming Dynasty had saved the country from the clutches of Hideyoshi and his Japanese invaders in the Sixteenth Century. Yuan Shih-kai had been personally recommended by this General Wu Chang-ching as a young man of ability and energy to the famous Li Hung Chang, who as Tientsin Viceroy and High Commissioner for the Northern Seas was responsible for the conduct of Korean affairs. The future dictator of China was then only twenty-five years old.

His very first contact with practical politics gave him a peculiar manner of viewing political problems. The arrival of Chinese troops in Seoul marked the beginning of that acute rivalry with Japan which finally culminated in the short and disastrous war of 1894-95. China, in order to preserve her influence in Korea against the growing influence of Japan, intrigued night and day in the Seoul Palaces, allying herself with the Conservative Court party which was led by the notorious Korean Queen who was afterwards assassinated. The Chinese agents aided and abetted the reactionary group, constantly inciting them to attack the Japanese and drive them out of the country.

19Continual outrages were the consequence. The Japanese legation was attacked and destroyed by the Korean mob not once but on several occasions during a decade which furnishes one of the most amazing chapters in the history of Asia. Yuan Shih-kai, being then merely a junior general officer under the orders of the Chinese Imperial Resident, is of no particular importance; but it is significant of the man that he should suddenly come well under the limelight on the first possible occasion. On 6th December, 1884, leading 2,000 Chinese troops, and acting in concert with 3,000 Korean soldiers, he attacked the Tong Kwan Palace in which the Japanese Minister and his staff, protected by two companies of Japanese infantry, had taken refuge owing to the threatening state of affairs in the capital. Apparently there was no particular plan—it was the action of a mob of soldiery tumbling into a political brawl and assisted by their officers for reasons which appear to-day nonsensical. The sequel was, however, extraordinary. The Japanese held the Palace gates as long as possible, and then being desperate exploded a mine which killed numbers of Koreans and Chinese soldiery and threw the attack into confusion. They then fought their way out of the city escaping ultimately to the nearest sea-port, Chemulpo.

The explanation of this extraordinary episode has never been made public. The practical result was that after a period of extreme tension between China and Japan which was expected to lead to war, that political genius, the late Prince Ito, managed to calm things down and arrange workable modus vivendi. Yuan Shih-kai, who had gone to Tientsin to report in person to Li Hung Chang, returned to Seoul triumphantly in October, 1885, as Imperial Resident. He was then twenty-eight years old; he had come to the front, no matter by what means, in a quite remarkable manner.

The history of the next nine years furnishes plenty of minor incidents, but nothing of historic importance. As the faithful lieutenant of Li Hung Chang, Yuan Shih-kai's particular business was simply to combat Japanese influence and hold the threatened advance in check. He failed, of course, since he was playing a losing game; and yet he succeeded where he undoubtedly wished to succeed. By rendering faithful service 20he established the reputation he wished to win; and though he did nothing great he retained his post right up to the act which led to the declaration of war in 1894. Whether he actually precipitated that war is still a matter of opinion. On the sinking by the Japanese fleet of the British steamer Kowshing, which was carrying Chinese reinforcements from Taku anchorage to Asan Bay to his assistance, seeing that the game was up, he quietly left the Korean capital and made his way overland to North China. That swift, silent journey home ends the period of his novitiate.

It took him a certain period to weather the storm which the utter collapse of China in her armed encounter with Japan brought about—and particularly to obtain forgiveness for evacuating Seoul without orders. Technically his offence was punishable by death—the old Chinese code being most stringent in such matters. But by 1896 he was back in favour again, and through the influence of his patron Li Hung Chang, he was at length appointed in command of the Hsiaochan camp near Tientsin, where he was promoted and given the task of reforming a division of old-style troops and making them as efficient as Japanese soldiery. He had already earned a wide reputation for severity, for willingness to accept responsibility, for nepotism, and for a rare ability to turn even disasters to his own advantage—all attributes which up to the last moment stood him in good stead.

In the Hsiaochan camp the most important chapter of his life opens; there is every indication that he fully realized it. Tientsin has always been the gateway to Peking: from there the road to high preferment is easily reached. Yuan Shih-kai marched steadily forward, taking the very first turning-point in a manner which stamped him for many of his compatriots in a way which can never be obliterated.

It is first necessary to say a word about the troops of his command, since this has a bearing on present-day politics. The bulk of the soldiery were so-called Huai Chun—i.e., nominally troops from the Huai districts, just south of Li Hung Chang's native province Anhui. These Kiangu men, mixed with Shantung recruits, had earned a historic place in the favour of the Manchus owing to the part they had played in the suppression of the 21Taiping Rebellion, in which great event General Gordon and Li Hung Chang had been so closely associated. They and the troops of Hunan province, led by the celebrated Marquis Tseng Kuo-fan, were "the loyal troops," resembling the Sikhs during the Indian Mutiny; they were supposed to be true to their salt to the last man. Certainly they gave proofs of uncustomary fidelity.

In those military days of twenty years ago Yuan Shih-kai and his henchmen were, however, concerned with simpler problems. It was then a question of drill and nothing but drill. In his camp near Tientsin the future President of the Chinese Republic succeeded in reorganizing his troops so well that in a very short time the Hsiaochan Division became known as a corps d'élite. The discipline was so stern that there were said to be only two ways of noticing subordinates, either by promoting or beheading them. Devoting himself to his task Yuan Shih-kai gave promise of being able to handle much bigger problems.

His zeal soon attracted the attention of the Manchu Court. The circumstances in Peking at that time were peculiar. The famous old Empress Dowager, Tzu-hsi, after the Japanese war, had greatly relaxed her hold on the Emperor Kwanghsu, who though still in subjection to her, nominally governed the empire. A well-intentioned but weak man, he had surrounded himself with advanced scholars, led by the celebrated Kang Yu Wei, who daily studied with him and filled him with new doctrines, teaching him to believe that if he would only exert his power he might rescue the nation from international ignominy and make for himself an imperishable name.

The sequel was inevitable. In 1898 the oriental world was electrified by the so-called Reform Edicts, in which the Emperor undertook to modernize China, and in which he exhorted the nation to obey him. The greatest alarm was created in Court circles by this action; the whole vast body of Metropolitan officialdom, seeing its future threatened, flooded the Palace of the Empress Dowager with Secret Memorials praying her to resume power. Flattered, she gave her secret assent.

Things marched quickly after that. The Empress, nothing loth, began making certain dispositions. Troops were moved, men were shifted here and there in a way that presaged action; 22and the Emperor, now thoroughly alarmed and yielding to the entreaties of his followers, sent two members of the Reform Party to Yuan Shih-kai bearing an alleged autograph order for him to advance instantly on Peking with all his troops; to surround the Palace, to secure the person of the Emperor from all danger, and then to depose the Empress Dowager for ever from power. What happened is equally well-known. Yuan Shih-kai, after an exhaustive examination of the message and messengers, as well as other attempts to substantiate the genuineness of the appeal, communicated its nature to the then Viceroy of Chihli, the Imperial Clansman Jung Lu, whose intimacy with the Empress Dowager since the days of her youth has passed into history. Jung Lu lost no time in acting. He beheaded the two messengers and personally reported the whole plot to the Empress Dowager who was already fully warned. The result was the so-called coup d'état of September, 1898, when all the Reformers who had not fled were summarily executed, and the Emperor Kwanghsu himself closely imprisoned in the Island Palace within that portion of the Forbidden City known as the Three Lakes, having (until the Boxer outbreak of 1900 carried him to Hsianfu), as sole companions his two favourites, the celebrated odalisques "Pearl" and "Lustre."

This is no place to enter into the controversial aspect of Yuan Shih-kai's action in 1898 which has been hotly debated by partisans for many years. For onlookers the verdict must always remain largely a matter of opinion; certainly this is one of those matters which cannot be passed upon by any one but a Chinese tribunal furnished with all the evidence. Those days which witnessed the imprisonment of Kwanghsu were great because they opened wide the portals of the Romance of History: all who were in Peking can never forget the counter-stroke; the arrival of the hordes composed of Tung Fu-hsiang's Mahommedan cavalry—men who had ridden hard across a formidable piece of Asia at the behest of their Empress and who entered the capital in great clouds of dust. It was in that year of 1898 also that Legation Guards reappeared in Peking—a few files for each Legation as in 1860—and it was then that clear-sighted prophets saw the beginning of the end of the Manchu Dynasty.

Yuan Shih-kai's reward for his share in this counter-revolution 23was his appointment to the governorship of Shantung province. He moved thither with all his troops in December, 1899. Armed cap-à-pie he was ready for the next act—the Boxers, who burst on China in the Summer of 1900. These men were already at work in Shantung villages with their incantations and alleged witchcraft. There is evidence that their propaganda had been going on for months, if not for years, before any one had heard of it. Yuan Shih-kai had the priceless opportunity of studying them at close range and soon made up his mind about certain things. When the storm burst, pretending to see nothing but mad fanatics in those who, realizing the plight of their country, had adopted the war-cry "Blot out the Manchus and the foreigner," he struck at them fiercely, driving the whole savage horde head-long into the metropolitan province of Chihli. There, seduced by the Manchus, they suddenly changed the inscription on their flags. Their sole enemy became the foreigner and all his works, and forthwith they were officially protected. Far and wide they killed every white face they could find. They tore up railways, burnt churches and chapels and produced a general anarchy which could only have one end—European intervention. The man, sitting on the edge of Chinese history but not yet identifying himself with its main currents because he was not strong enough for that had once again not judged wrongly. With his Korean experience to assist him, he had seen precisely what the end must inevitably be.

The crash in Peking, when the siege of the Legations had been raised by an international army, found him alert and sympathetic—ready with advice, ready to shoulder new responsibilities, ready to explain away everything. The signature of the Peace Protocol of 1901 was signalized by his obtaining the viceroyalty of Chihli, succeeding the great Li Hung Chang himself, who had been reappointed to his old post, but had found active duties too wearisome. This was a marvellous success for a man but little over forty. And when the fugitive Court at length returned from Hsianfu in 1902, honours were heaped upon him as a person particularly worthy of honour because he had kept up appearances and maintained the authority of the distressed Throne. As if in answer to this he flooded the Court with memorials praying that in order to restore the power of the Dynasty a complete 24army of modern troops be raised—as numerous as possible but above all efficient.

His advice was listened to. From 1902 until 1907 as Minister of the Army Reorganization Council—a special post he held simultaneously with that of metropolitan Viceroy—Yuan Shih-kai's great effort was concentrated on raising an efficient fighting force. In those five years, despite all financial embarrassments, North China raised and equipped six excellent Divisions of field-troops—75,000 men—all looking to Yuan Shih-kai as their sole master. So much energy did he display in pushing military reorganization throughout the provinces that the Court, warned by jealous rivals of his growing power, suddenly promoted him to a post where he would be powerless. One day he was brought to Peking as Grand Councillor and President of the Board of Foreign Affairs, and ordered to hand over all army matters to his noted rival, the Manchu Tieh Liang. The time had arrived to muzzle him. His last phase as a pawn had come.

Few foreign diplomats calling at China's Foreign Office to discuss matters during that short period which lasted barely a twelve-month, imagined that the square resolute-looking man who as President of the Board gave the same energy and attention to consular squabbles as to the reorganization of a national-fighting force, was almost daily engaged in a fierce clandestine struggle to maintain even his modest position. Jealousy, which flourishes in Peking like the upas tree, was for ever blighting his schemes and blocking his plans. He had been brought to Peking to be tied up; he was constantly being denounced; and even his all powerful patroness, the old Empress Dowager, who owed so much to him, suffered from constant premonitions that the end was fast approaching, and that with her the Dynasty would die.

In the Autumn of 1908 she took sick. The gravest fears quickly spread. It was immediately reported that the Emperor Kwanghsu was also very ill—an ominous coincidence. Very suddenly both personages collapsed and died, the Empress Dowager slightly before the Emperor. There is little doubt that the Emperor himself was poisoned. The legend runs that as he expired not only did he give his Consort, who was to succeed him in the exercise of the nominal power of the Throne, a last secret Edict to behead Yuan Shih-kai, but that his faltering hand 25described circle after circle in the air until his followers understood the meaning. In the vernacular the name of the great viceroy and the word for circle have the same sound; the gesture signified that the dying monarch's last wish was revenge on the man who had failed him ten years before.

An ominous calm followed this great break with the past. It was understood that the Court was torn by two violent factions regarding the succession which the Empress Tzu-hsi had herself decided. The fact that another long Regency had become inevitable through the accession of the child Hsuan Tung aroused instant apprehensions among foreign observers, whilst it was confidently predicted that Yuan Shih-kai's last days had come.

The blow fell suddenly on the 2nd January, 1909. In the interval between the death of the old Empress and his disgrace, Yuan Shih-kai was actually promoted to the highest rank in the gift of the Throne, that is, made "Senior Guardian of the Heir Apparent" and placed in charge of the Imperial funeral arrangements—a lucrative appointment. During that interval it is understood that the new Regent, brother of the Emperor Kwanghsu, consulted all the most trusted magnates of the empire regarding the manner in which the secret decapitation Decree should be treated. All advised him to be warned in time, and not to venture on a course of action which would be condemned both by the nation and by the Powers. Another Edict was therefore prepared simply dismissing Yuan Shih-kai from office and ordering him to return to his native place.

Every one remembers that day in Peking when popular rumour declared that the man's last hour had come. Warned on every side to beware, Yuan Shih-kai left the Palace as soon as he had read the Edict of dismissal in the Grand Council and drove straight to the railway-station, whence he entrained for Tientsin, dressed as a simple citizen. Rooms had been taken for him at a European hotel, the British Consulate approached for protection, when another train brought down his eldest son bearing a message direct from the Grand Council Chamber, absolutely guaranteeing the safety of his life. Accordingly he duly returned to his native place in Honan province, and for two years—until the outbreak of the Revolution—devoted himself sedulously to the development of the large estate he had acquired with the fruits of office. 26Living like a patriarch of old, surrounded by his many wives and children, he announced constantly that he had entirely dropped out of the political life of China and only desired to be left in peace. There is reason to believe, however, that his henchmen continually reported to him the true state of affairs, and bade him bide his time. Certain it is that the firing of the first shots on the Yangtsze found him alert and issuing private orders to his followers. It was inevitable that he should have been recalled to office—and actually within one hundred hours of the first news of the outbreak the Court sent for him urgently and ungraciously.

From the 14th October, 1911, when he was appointed by Imperial Edict Viceroy of Hupeh and Hunan and ordered to proceed at once to the front to quell the insurrection, until the 1st November, when he was given virtually Supreme Power as President of the Grand Council in place of Prince Ching, a whole volume is required to discuss adequately the maze of questions involved. For the purposes of this account, however, the matter can be dismissed very briefly in this way. Welcoming the opportunity which had at last come and determined once for all to settle matters decisively, so far as he was personally concerned, Yuan Shih-kai deliberately followed the policy of holding back and delaying everything until the very incapacity marking both sides—the Revolutionists quite as much as the Manchus—forced him, as man of action and man of diplomacy, to be acclaimed the sole mediator and saviour of the nation.

The detailed course of the Revolution, and the peculiar manner in which Yuan Shih-kai allowed events rather than men to assert their mastery has often been related and need not long detain us. It is generally conceded that in spite of the bravery of the raw revolutionary levies, their capacity was entirely unequal to the trump card Yuan Shih-kai held all the while in his hand—the six fully-equipped Divisions of Field Troops he himself had organized as Tientsin Viceroy. It was a portion of this field-force which captured and destroyed the chief revolutionary base in the triple city of Hankow, Hanyang and Wuchang in November, 1911, and which he held back just as it was about to give the coup de grâce by crossing the river in force and sweeping the last remnants of the revolutionary army to perdition. Thus it is 27correct to declare that had he so wished Yuan Shih-kai could have crushed the revolution entirely before the end of 1911; but he was sufficiently astute to see that the problem he had to solve was not merely military but moral as well. The Chinese as a nation were suffering from a grave complaint. Their civilization had been made almost bankrupt owing to unresisted foreign aggression and to the native inability to cope with the mass of accumulated wrongs which a superimposed and exhausted feudalism—the Manchu system—had brought about. Yuan Shih-kai knew that the Boxers had been theoretically correct in selecting as they first did the watchword which they had first placed on their banners—"blot out the Manchus and all foreign things." Both had sapped the old civilization to its foundations. But the programme they had proposed was idealistic, not practical. One element could be cleared away—the other had to be endured. Had the Boxers been sensible they would have modified their programme to the extent of protecting the foreigners, whilst they assailed the Dynasty which had brought them so low. The Court Party, as we have said, seduced their leaders to acting in precisely the reverse sense.

Yuan Shih-kai was neither a Boxer, nor yet a believer in idealistic foolishness. He had realized that the essence of successful rule in the China of the Twentieth Century was to support the foreign point of view—nominally at least—because foreigners disposed of unlimited monetary resources, and had science on their side. He knew that so long as he did not openly flout foreign opinion by indulging in bare-faced assassinations, he would be supported owing to the international reputation he had established in 1900. Arguing from these premises, his instinct also told him that an appearance of legality must always be sedulously preserved and the aspirations of the nation nominally satisfied. For this reason he arranged matters in such a manner as to appear always as the instrument of fate. For this reason, although he destroyed the revolutionists on the mid-Yangtsze, to equalize matters, on the lower Yangtsze he secretly ordered the evacuation of Nanking by the Imperialist forces so that he might have a tangible argument with which to convince the Manchus regarding the root and branch reform which he knew was necessary. That reform had been accepted in principle by the Throne when it 28agreed to the so-called Nineteen Fundamental Articles, a corpus of demands which all the Northern Generals had endorsed and had indeed insisted should be the basis of government before they would fight the rebellious South in 1911. There is reason to believe that provided he had been made de facto Regent, Yuan Shih-kai would have supported to the end a Manchu Monarchy. But the surprising swiftness of the Revolutionary Party's action in proclaiming the Republic at Nanking on the 1st January, 1912, and the support which foreign opinion gave that venture confused him. He had already consented to peace negotiations with the revolutionary South in the middle of December, 1911, and once he was drawn into those negotiations his policy wavered, the armistice in the field being constantly extended because he saw that the Foreign Powers, and particularly England, were averse from further civil war. Having dispatched a former lieutenant, Tong Shao-yi, to Shanghai as his Plenipotentiary, he soon found himself committed to a course of action different from what he had originally contemplated. South China and Central China insisted so vehemently that the only solution that was acceptable to them was the permanent and absolute elimination of the Manchu Dynasty, that he himself was half-convinced, the last argument necessary being the secret promise that he should become the first President of the united Republic. In the circumstances, had he been really loyal, it was his duty either to resume his warfare or resign his appointment as Prime Minister and go into retirement. He did neither. In a thoroughly characteristic manner he sought a middle course, after having vaguely advocated a national convention to settle the matter. By specious misrepresentation the widow of the Emperor Kwanghsu—the Dowager Empress Lung Yu who had succeeded the Prince Regent Ch'un in her care of the interests of the child Emperor Hsuan Tung—was induced to believe that ceremonial retirement was the only course open to the Dynasty if the country was to be saved from disruption and partition. There is reason to believe that the Memorial of all the Northern Generals which was telegraphed to Peking on the 28th January, 1912, and which advised abdication, was inspired by him. In any case it was certainly Yuan Shih-kai who drew up the so-called Articles of Favourable Treatment for the Manchu House and caused them 29to be telegraphed to the South, whence they were telegraphed back to him as the maximum the Revolutionary Party was prepared to concede: and by a curious chance the attempt made to assassinate him outside the Palace Gates actually occurred on the very day he had submitted an outline of these terms on his bended knees to the Empress Dowager and secured their qualified acceptance. The pathetic attempt to confer on him as late as the 25th January the title of Marquess, the highest rank of nobility which could be given a Chinese, an attempt which was four times renewed, was the last despairing gesture of a moribund power. Within very few days the Throne reluctantly decreed its own abdication in three extremely curious Edicts which are worthy of study in the appendix. They prove conclusively that the Imperial Family believed that it was only abdicating its political power, whilst retaining all ancient ceremonial rights and titles. Plainly the conception of a Republic, or a People's Government, as it was termed in the native ideographs, was unintelligible to Peking.

Yuan Shih-kai had now won everything he wished for. By securing that the Imperial Commission to organize the Republic and re-unite the warring sections was placed solely in his hands, he prepared to give a type of Government about which he knew nothing a trial. It is interesting to note that he held to the very end of his life that he derived his powers solely from the Last Edicts, and in nowise from his compact with the Nanking Republic which had instituted the so-called Provisional Constitution. He was careful, however, not to lay this down categorically until many months later, when his dictatorship seemed undisputed. But from the day of the Manchu Abdication almost, he was constantly engaged in calculating whether he dared risk everything on one throw of the dice and ascend the Throne himself; and it is precisely this which imparts such dramatic interest to the astounding story which follows.

To describe briefly and intelligibly the series of transactions from the 1st January, 1912, when the Republic was proclaimed at Nanking by a handful of provincial delegates, and Dr. Sun Yat Sen elected Provisional President, to the coup d'état of 4th November, 1913, when Yuan Shih-kai, elected full President a few weeks previously, after having acted as Chief Executive for twenty months, boldly broke up Parliament and made himself de facto Dictator of China, is a matter of extraordinary difficulty.

All through this important period of Chinese history one has the impression that one is in dreamland and that fleeting emotions take the place of more solid things. Plot and counter-plot follow one another so rapidly that an accurate record of them all would be as wearisome as the Book of Chronicles itself; whilst the amazing web of financial intrigue which binds the whole together is so complex—and at the same time so antithetical to the political struggle—that the two stories seem to run counter to one another, although they are as closely united as two assassins pledged to carry through in common a dread adventure. A huge agglomeration of people estimated to number four hundred millions, being left without qualified leaders and told that the system of government, which had been laid down by the Nanking Provisional Constitution and endorsed by the Abdication Edicts, was a system in which every man was as good as neighbour, swayed meaninglessly to and fro, vainly seeking to regain the equilibrium which had been so sensationally lost. A litigious 31spirit became so universal that all authority was openly derided, crimes of every description being so common as to force most respectable men to withdraw from public affairs and leave a bare rump of desperadoes in power.

Long embarrassed by the struggle to pay her foreign loans and indemnities, China was also virtually penniless. The impossibility of arranging large borrowings on foreign markets without the open support of foreign governments—a support which was hedged round with conditions—made necessary a system of petty expedients under which practically every provincial administration hypothecated every liquid asset it could lay hands upon in order to pay the inordinate number of undisciplined soldiery who littered the countryside. The issue of unguaranteed paper-money soon reached such an immense figure that the market was flooded with a worthless currency which it was unable to absorb. The Provincial leaders, being powerless to introduce improvement, exclaimed that it was the business of the Central Government as representative of the sovereign people to find solutions; and so long as they maintained themselves in office they went their respective ways with a sublime contempt for the chaos around them.

What was this Central Government? In order successfully to understand an unparalleled situation we must indicate its nature.

The manoeuvres to which Yuan Shih-kai had so astutely lent himself from the outbreak of the Revolution had left him at its official close supreme in name. Not only had he secured an Imperial Commission from the abdicating Dynasty to organize a popular Government in obedience to the national wish, but having brought to Peking the Delegates of the Nanking Revolutionary Body he had received from them the formal offer of the Presidency.

These arrangements had, of course, been secretly agreed to en bloc before the fighting had been stopped and the abdication proclaimed, and were part and parcel of the elaborate scenery which officialdom always employs in Asia even when it is dealing with matters within the purview of the masses. They had been made possible by the so-called "Article of Favourable Treatment" drawn-up by Yuan Shih-kai himself, after consultation 32with the rebellious South. In these Capitulations it had been clearly stipulated that the Manchu Imperial Family should receive in perpetuity a Civil List of $4,000,000 Mexican a year, retaining all their titles as a return for the surrender of their political power, the bitter pill being gilded in such fashion as to hide its real meaning, which alone was a grave political error.

In spite of this agreement, however, great mutual suspicion existed between North and South China. Yuan Shih-kai himself was unable to forget that the bold attempt to assassinate him in the Peking streets on the 17th January, when he was actually engaged in negotiating these very terms of the Abdication, had been apparently inspired from Nanking; whilst the Southern leaders were daily reminded by the vernacular press that the man who held the balance of power had always played the part of traitor in the past and would certainly do the same again in the near future.

When the Delegates came to Peking in February, by far the most important matter which was still in dispute was the question of the oath of office which Yuan Shih-kai was called upon to take to insure that he would be faithful to the Republic. The Delegates had been charged specifically to demand on behalf of the seceding provinces that Yuan Shih-kai should proceed with them to Nanking to take that oath, a course of action which would have been held tantamount by the nation to surrender on his part to those who had been unable to vanquish him in the field. It must also not be forgotten that from the very beginning a sharp and dangerous cleavage of opinion existed as to the manner in which the powers of the new government had been derived. South and Central China claimed, and claimed rightly, that the Nanking Provincial Constitution was the Instrument on which the Republic was based: Yuan Shih-kai declared that the Abdication Edicts, and not the Nanking Instrument had established the Republic, and that therefore it lay within his competence to organize the new government in the way which he considered most fit.

The discussion which raged was suddenly terminated on the night of the 29th February (1912) when without any warning there occurred the extraordinary revolt of the 3rd Division, a picked Northern corps who for forty-eight hours plundered and 33 burnt portions of the capital without any attempts at interference, there being little doubt to-day that this manoeuvre was deliberately arranged as a means of intimidation by Yuan Shih-kai himself. Although the disorders assumed such dimensions that foreign intervention was narrowly escaped, the upshot was that the Nanking Delegates were completely cowed and willing to forget all about forcing the despot of Peking to proceed to the Southern capital. Yuan Shih-kai as the man of the hour was enabled on the 10th March, 1912, to take his oath in Peking as he had wished thus securing full freedom of action during the succeeding years.[6]

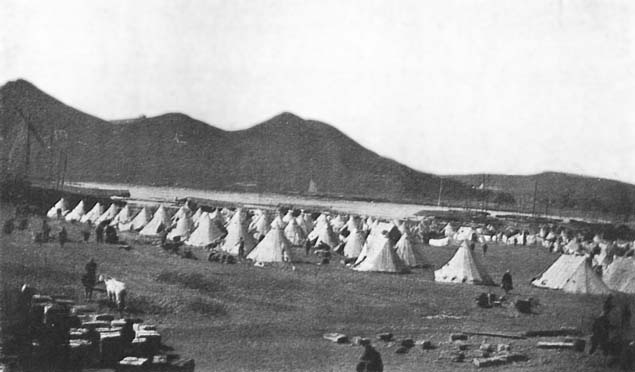

An Encampment of "The Punitive Expedition" of 1910 on the Upper Yangtsze.

By courtesy of Major Isaac Newell, U.S. Military Attaché.

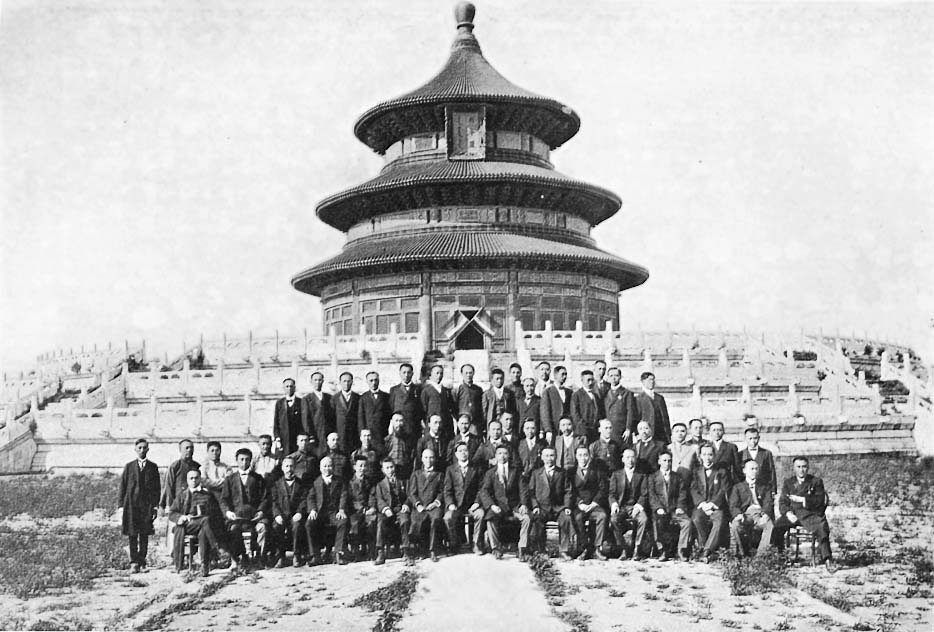

Revival of the Imperialistic Worship of Heaven by Yuan Shih-kai in 1914: Scene on the Altar of Heaven, with Sacrificial Officers clothed in costumes dating from 2,000 years ago.

It was on this astounding basis—by means of an organized revolt—that the Central Government was reorganized; and every act that followed bears the mark of its tainted parentage. Accepting readily as his Ministers in the more unimportant government Departments the nominees of the Southern Confederacy (which was now formally dissolved), Yuan Shih-kai was careful to reserve for his own men everything that concerned the control of the army and the police, as well as the all-important ministry of finance. The framework having been thus erected, attention was almost immediately concentrated on the problem of finding money, an amazing matter which would weary the stoutest reader if given in all its detail but which being part and parcel of the general problem must be referred to.