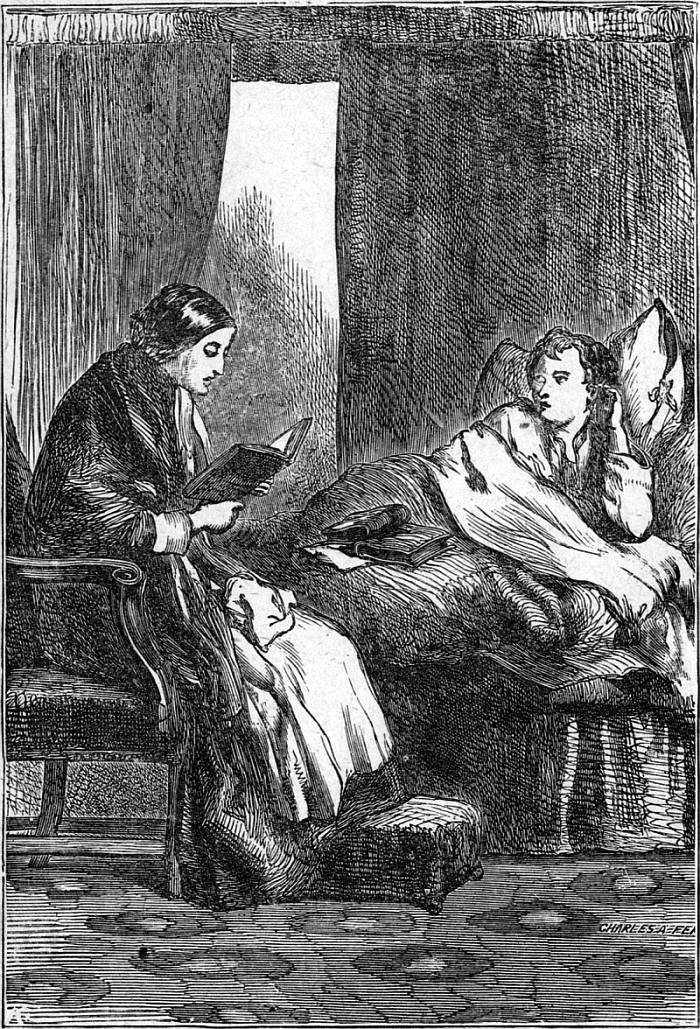

Lady Grange Reading To Her Son.

Page 19.

Title: False Friends, and The Sailor's Resolve

Author: Unknown

Release date: December 31, 2004 [eBook #14543]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Sherry Hamby, Ted Garvin, Melissa Er-Raqabi, Jeannie Howse, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (https://www.pgdp.net)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, False Friends, and The Sailor's Resolve, by Unknown

1884.

"Thorns and snares are in the way of the froward."—PROV. xxii. 5.

"Philip, your conduct has distressed me exceedingly," said Lady Grange, laying her hand on the arm of her son, as they entered together the elegant apartment which had been fitted up as her boudoir. "You could not but know my feelings towards those two men—I will not call them gentlemen—whose company you have again forced upon me. You must be aware that your father has shut the door of this house against them."

"My father has shut the door against better men than they are," said the youth carelessly; "witness my own uncles Henry and George."

The lip of the lady quivered, the indignant colour rose even to her temples; she attempted to speak, but her voice failed her, and she turned aside to hide her emotion.

"Well, mother, I did not mean to vex you," said Philip, who was rather weak in purpose than hardened in evil; "it was a shame to bring Jones and Wildrake here, but—but you see I couldn't help it." And he played uneasily with his gold-headed riding-whip, while his eye avoided meeting that of his mother.

"They have acquired some strange influence, some mysterious hold over you," answered the lady. "It cannot be," she added anxiously, "that you have broken your promise,—that they have drawn you again to the gaming-table,—that you are involved in debt to these men?"

Philip whistled an air and sauntered up to the window.

Lady Grange pressed her hand over her eyes, and a sigh, a very heavy sigh, burst from her bosom. Philip heard, and turned impatiently round.

"There's no use in making the worst of matters," said he; "what's done can't be helped; and my debts, such as they are, won't ruin a rich man like my father."

"It is not that which I fear," said the mother faintly, with a terrible consciousness that her son,—her hope, her pride, the delight of her heart,—had entered on a course which, if persevered in, must end in his ruin both of body and soul. "I tremble at the thought of the misery which you are bringing on yourself. These men are making you their victim: they are blinding your eyes; they are throwing a net around you, and you have not the resolution to break from the snare."

"They are very pleasant, jovial fellows!" cried Philip, trying to hide under an appearance of careless gaiety the real annoyance which he felt at the words of his mother.

"I've asked them to dine here to-day and—"

"I shall not appear at the table," said Lady Grange, drawing herself up with dignity; "and if your father should arrive—"

"Oh! he won't arrive to-night; he never travels so late."

"But, Philip," said the lady earnestly again laying her cold hand on his arm. She was interrupted by her wayward and undutiful son.

"Mother, there's no use in saying anything more on the subject; it only worries you, and puts me out of temper. I can't, and I won't be uncivil to my friends;" and turning hastily round, Philip quitted the apartment.

"Friends!" faintly echoed Lady Grange, as she saw the door close behind her misguided son. "Oh!" she exclaimed, throwing herself on a sofa, and burying her face, "was there ever a mother—ever a woman so unhappy as I am!"

Her cup was indeed very bitter; it was one which the luxuries that surrounded her had not the least power to sweeten. Her husband was a man possessing many noble qualities both of head and heart; but the fatal love of gold, like those petrifying springs which change living twigs to dead stone, had made him hardened, quarrelsome, and worldly. It had drawn him away from the worship of his God; for there is deep truth in the declaration of the apostle, that the covetous man is an idolater. It was this miserable love of gold which had induced Sir Gilbert to break with the family of his wife, and separate her from those to whom her loving heart still clung with the fondest affection. Lady Grange yearned for a sight of her early home; but gold had raised a barrier between her and the companions of her childhood. And what had the possession of gold done for the man who made it his idol? It had put snares in the path of his only son; it had made the weak-minded but head-strong youth be entrapped by the wicked for the sake of his wealth, as the ermine is hunted down for its rich fur. It had given to himself heavy responsibilities, for which he would have to answer at the bar of Heaven; for from him unto whom much has been given, much at the last day will be required.

Yes, Lady Grange was very miserable. And how did she endeavour to lighten the burden of her misery? Was it by counting over her jewels,—looking at the costly and beautiful things which adorned her dwelling,—thinking of her carriages and horses and glittering plate, or the number of her rich and titled friends? No; she sought comfort where Widow Green had sought it when her child lay dangerously ill, and there was neither a loaf on her shelf nor a penny in her purse. The rich lady did what the poor one had done,—she fell on her knees and with tears poured out her heart to the merciful Father of all. She told him her sorrows, she told him her fears; she asked him for that help which she so much required. Her case was a harder one than the widow's. A visit from the clergyman, a present from a benevolent friend, God's blessing on a simple remedy, had soon changed Mrs. Green's sorrow into joy. The anguish of Lady Grange lay deeper; her faith was more sorely tried; her fears were not for the bodies but the souls of those whom she loved;—and where is the mortal who can give us a cure for the disease of sin?

While his mother was weeping and praying, Philip was revelling and drinking. Fast were the bottles pushed round, and often were the glasses refilled. The stately banqueting-room resounded with laughter and merriment; and as the evening advanced, with boisterous song. It was late before the young men quitted the table; and then, heated with wine, they threw the window wide open, to let the freshness of the night air cool their fevered temples.

Beautiful looked the park in the calm moonlight. Not a breath stirred the branches of the trees, their dark shadows lay motionless on the green sward: perfect silence and stillness reigned around. But the holy quietness of nature was rudely disturbed by the voices of the revellers.

With the conversation that passed I shall not soil my pages. The window opened into a broad stone balcony, and seating themselves upon its parapet, the young men exchanged stories and jests. After many sallies of so-called wit, Wildrake rallied Philip on the quantity of wine which he had taken, and betted that he could not walk steadily from the one end of the balcony to the other. Philip, with that insane pride which can plume itself on being mighty to mingle strong drink, maintained that his head was as clear and his faculties as perfect as though he had tasted nothing but water; and declared that he could walk round the edge of the parapet with as steady a step as he would tread the gravel-path in the morning!

Wildrake laughed, and dared him to do it: Jones betted ten to one that he could not.

"Done!" cried Philip, and sprang up on the parapet in a moment.

"Come down again!" called out Wildrake, who had enough of sense left to perceive the folly and danger of the wager.

Philip did not appear to hear him. Attempting to balance himself by his arms, with a slow and unsteady step he began to make his way along the lofty and narrow edge.

The two young men held their breath. To one who with unsteady feet walks the slippery margin of temptation, the higher his position, the greater his danger; the loftier his elevation, the more perilous a fall!

"He will never get to the end!" said Jones, watching with some anxiety the movements of his companion.

The words had scarcely escaped his lips when they received a startling fulfilment. Philip had not proceeded half way along the parapet when a slight sound in the garden below him attracted his attention. He glanced down for a moment; and there, in the cold, clear moonlight, gazing sternly upon him, he beheld his father! The sudden start of surprise which he gave threw the youth off his balance,—he staggered back, lost his footing, stretched out his hands wildly to save himself, and fell with a loud cry to the ground!

All was now confusion and terror. There were the rushing of footsteps hither and thither, voices calling, bells loudly ringing, and, above all, the voice of a mother's anguish, piercing to the soul! Jones and Wildrake hurried off to the stables, saddled their horses themselves, and dashed off at full speed to summon a surgeon, glad of any excuse to make their escape from the place.

The unfortunate Philip was raised from the ground, and carried into the house. His groans showed the severity of his sufferings. The slightest motion was to him torture, and an hour of intense suspense ensued before the arrival of the surgeon. Lady Grange made a painful effort to be calm. She thought of everything, did all that she could do for the relief of her son, and even strove to speak words of comfort and hope to her husband, who appeared almost stupified by his sorrow. Prayer was still her support—prayer, silent, but almost unceasing.

The surgeon arrived,—the injuries received by the sufferer were examined, though it was long before Philip, unaccustomed to pain and incapable of self-control, would permit necessary measures to be taken. His resistance greatly added to his sufferings. He had sustained a compound fracture of his leg, besides numerous bruises and contusions. The broken bone had to be set, and the pale mother stood by, longing, in the fervour of her unselfish love, that she could endure the agony in the place of her son. The pampered child of luxury shrank sensitively from pain, and the thought that he had brought all his misery upon himself by his folly and disobedience rendered it yet more intolerable. When the surgeon had at length done his work, Lady Grange retired with him to another apartment, and, struggling to command her choking voice, asked him the question on the reply to which all her earthly happiness seemed to hang,—whether he had hope that the life of her boy might be spared.

"I have every hope", said the surgeon, cheerfully, "if we can keep down the fever." Then, for the first time since she had seen her son lie bleeding before her, the mother found the relief of tears.

Through the long night she quitted not the sufferer's pillow, bathing his fevered brow, relieving his thirst, whispering comfort to his troubled spirit. Soon after daybreak Philip sank into a quiet, refreshing sleep; and Lady Grange, feeling as if a mountain's weight had been lifted from her heart, hurried to carry the good news to her husband.

She found him in the spacious saloon, pacing restlessly to and fro. His brow was knit, his lips compressed; his disordered dress and haggard countenance showed that he, too, had watched the live-long night.

"He sleeps at last, Gilbert, thank God!" Her face brightened as she spoke; but there was no corresponding look of joy on that of her husband.

"Gilbert, the doctor assures me that there is every prospect of our dear boy's restoration!"

"And to what is he to be restored?" said the father gloomily; "to poverty—misery—ruin!"

Lady Grange stood mute with surprise scarcely believing the evidence of her senses almost deeming that the words must have been uttered in a dream. But it was no dream, but one of those strange, stern realities which we meet with in life. Her husband indeed stood before her a ruined man! A commercial crash, like those which have so often reduced the rich to poverty, coming almost as suddenly as the earthquake which shakes the natural world, had overthrown all his fortune! The riches in which he had trusted had taken to themselves wings and flown away.

Here was another startling shock, but Lady Grange felt it far less than the first. It seemed to her that if her son were only spared to her, she could bear cheerfully any other trial. When riches had increased, she had not set her heart upon them; she had endeavoured to spend them as a good steward of God and to lay up treasure in that blessed place where there is no danger of its ever being lost. Sir Gilbert was far more crushed than his wife was by this misfortune. He saw his idol broken before his eyes, and where was he to turn for comfort? Everything upon which his eye rested was a source of pain to him; for must he not part with all, leave all in which his heart had delighted, all in which his soul had taken pride? He forgot that poverty was only forestalling by a few years the inevitable work of death!

The day passed wearily away. Philip suffered much pain, was weak and low, and bitterly conscious how well he had earned the misery which he was called on to endure. It was a mercy that he was experiencing, before it was too late, that thorns and snares are in the way of the froward. He liked his mother to read the Bible to him, just a few verses at a time, as he had strength to bear it; and in this occupation she herself found the comfort which she needed. Sir Gilbert, full of his own troubles, scarcely ever entered the apartment of his son.

Towards evening a servant came softly into the sick-room, bringing a sealed letter for her lady. There was no post-mark upon it, and the girl informed her mistress that the gentleman who had brought it was waiting in the garden for a reply. The first glance at the hand-writing, at the well-known seal, brought colour to the cheek of the lady. But it was a hand-writing which she had been forbidden to read; it was a seal which she must not break! She motioned to the maid to take her place beside the invalid who happened at that moment to be sleeping and with a quick step and a throbbing heart she hurried away to find her husband.

He was in his study, his arms resting on his open desk, and his head bowed down upon them. Bills and papers, scattered in profusion on the table, showed what had been the nature of the occupation which he had not had the courage to finish. He started from his posture of despair as his wife laid a gentle touch on his shoulder; and, without uttering a word, she placed the unopened letter in his hand.

My reader shall have the privilege of looking over Sir Gilbert's shoulder, and perusing the contents of that letter:—

"Dearest Sister,—We have heard of your trials, and warmly sympathize in your sorrow. Let Sir Gilbert know that we have placed at his banker's, after having settled it upon you, double the sum which caused our unhappy differences. Let the past be forgotten; let us again meet as those should meet who have gathered together round the same hearth, mourned over the same grave, and shared joys and sorrows together, as it is our anxious desire to do now. I shall be my own messenger, and shall wait in person to receive your reply.—Your ever attached brother,

"Henry Latour."

A few minutes more and Lady Grange was in the arms of her brother; while Sir Gilbert was silently grasping the hand of one whom, but for misfortune, he would never have known as a friend.

All the neighbourhood pitied the gentle lady, the benefactress of the poor, when she dismissed her servants, sold her jewels, and quitted her beautiful home to seek a humbler shelter. Amongst the hundreds who crowded to the public auction of the magnificent furniture and plate, which had been the admiration of all who had seen them, many thought with compassion of the late owners, reduced to such sudden poverty, though the generosity of the lady's family had saved them from want or dependence.

And yet truly, never since her marriage had Lady Grange been less an object of compassion.

Her son was slowly but surely recovering, and his preservation from meeting sudden death unprepared was to her a source of unutterable thankfulness. Her own family appeared to regard her with even more tender affection than if no coldness had ever arisen between them; and their love was to her beyond price. Even Sir Gilbert's harsh, worldly character, was somewhat softened by trials, and by the unmerited kindness which he met with from those whom, in his prosperity, he had slighted and shunned. Lady Grange felt that her prayers had been answered indeed, though in a way very different from what she had hoped or expected. The chain by which her son had been gradually drawn down towards rum, by those who sought his company for the sake of his money, had been suddenly snapped by the loss of his fortune. The weak youth was left to the guidance of those to whom his welfare was really dear. Philip, obliged to rouse himself from his indolence, and exert himself to earn his living, became a far wiser and more estimable man than he would ever have been as the heir to a fortune; and he never forgot the lesson which pain, weakness, and shame had taught him,—that the way of evil is also the way of sorrow. Thorns and snares are in the way of the froward.

"An angry man stirreth up strife, and a furious man aboundeth in transgression."—PROV. xxix. 22.

The old sailor Jonas sat before the fire with his pipe in his mouth, looking steadfastly into the glowing coals. Not that, following a favourite practice of his little niece, he was making out red-hot castles and flaming buildings in the grate, or that his thoughts were in any way connected with the embers: he was doing what it would be well if we all sometimes did,—looking into himself, and reflecting on what had happened in relation to his own conduct.

"So," thought he, "here am I, an honest old fellow,—I may say it, with all my faults; and one who shrinks from falsehood more than from fire; and I find that I, with my bearish temper, am actually driving those about me into it—teaching them to be crafty, tricky, and cowardly! I knew well enough that my gruffness plagued others, but I never saw how it tempted others until now; tempted them to meanness, I would say, for I have found a thousand times that an angry man stirreth up strife, and that a short word may begin a long quarrel. I am afraid that I have not thought enough on this matter. I've looked on bad temper as a very little sin, and I begin to suspect that it is a great one, both in God's eyes and in the consequences that it brings. Let me see if I can reckon up its evils! It makes those miserable whom one would wish to make happy; it often, like an adverse gale, forces them to back, instead of steering straight for the port. It dishonours one's profession, lowers one's flag, makes the world mock at the religion which can leave a man as rough and rugged as a heathen savage. It's directly contrary to the Word of God,—it's wide as east from west of the example set before us! Yes, a furious temper is a very evil thing; I'd give my other leg to be rid of mine!" and in the warmth of his self-reproach the sailor struck his wooden one against the hearth with such violence as to make Alie start in terror that some fierce explosion was about to follow.

"Well, I've made up my mind as to its being an evil—a great evil," continued Jonas, in his quiet meditation; "the next question is, how is the evil to be got rid of? There's the pinch! It clings to one like one's skin. It's one's nature,—how can one fight against nature? And yet, I take it, it's the very business of faith to conquer our evil nature. As I read somewhere, any dead dog can float with the stream; it's the living dog that swims against it. I mind the trouble I had about the wicked habit of swearing, when first I took to trying to serve God and leave off my evil courses. Bad words came to my mouth as natural as the very air that I breathed. What did I do to cure myself of that evil? Why, I resolved again and again, and found that my resolutions were always snapping like a rotten cable in a storm; and I was driven from my anchorage so often, that I almost began to despair. Then I prayed hard to be helped; and I said to myself, 'God helps those who help themselves, and maybe if I determine to do something that I should be sorry to do every time that an oath comes from my mouth, it would assist me to remember my duty.' I resolved to break my pipe the first time that I swore; and I've never uttered an oath from that day to this, not even in my most towering passions! Now I'll try the same cure again; not to punish a sin, but to prevent it. If I fly into a fury, I'll break my pipe! There Jonas Colter, I give you fair warning!" and the old sailor smiled grimly to himself, and stirred the fire with an air of satisfaction.

Not one rough word did Jonas utter that evening; indeed he was remarkably silent, for the simplest way of saying nothing evil, he thought, was to say nothing at all. Jonas looked with much pleasure at his pipe when he put it on the mantle-piece for the night. "You've weathered this day, old friend," said he; "we'll be on the look out against squalls to-morrow."

The next morning Jonas occupied himself in his own room with his phials, and his nephew and niece were engaged in the kitchen in preparing for the Sunday school, which their mother made, them regularly attend. The door was open between the two rooms and as the place was not large, Jonas heard every word that passed between Johnny and Alie almost as well as if he had been close beside them.

Johnny. I say, Alie—

Alie. Please, Johnny, let me learn this quietly. If I do not know it my teacher will be vexed. My work being behind-hand yesterday has put me quite back with my tasks. You know that I cannot learn so fast as you do.

Johnny. Oh! you've plenty of time. I want you to do something for me. Do you know that I have lost my new ball?

Alie. Why, I saw you take it out of your pocket yesterday, just after we crossed the stile on our way back from the farm.

Johnny. That's it! I took it out of my pocket, and I never put it in again. I want you to go directly and look for the ball. That stile is only three fields off, you know. You must look carefully along the path all the way; and lose no time, or some one else may pick it up.

Alie. Pray, Johnny, don't ask me to go into the fields.

Johnny. I tell you, you have plenty of time for your lessons.

Alie. It is not that, but—

Johnny. Speak out, will you?

Alie. You know—there are—cows!

Johnny burst into a loud, coarse laugh of derision. "You miserable little coward!" he cried; "I'd like to see one chasing you round the meadow! How you'd scamper! how you'd scream! rare fun it would be,—ha! ha! ha!"

"Rare fun would it be, sir!" exclaimed an indignant voice, as Jonas stumped from the next room, and, seizing his nephew by the collar of his jacket, gave him a hearty shake; "rare fun would it be,—and what do you call this? You dare twit your sister with cowardice!—you who sneaked off yesterday like a fox because you had not the spirit to look an old man in the face!—you who bully the weak and cringe to the strong!—you who have the manners of a bear with the heart of a pigeon!" Every sentence was accompanied by a violent shake, which almost took the breath from the boy; and Jonas, red with passion, concluded his speech by flinging Johnny from him with such force that, but for the wall against which he staggered, he must have fallen to the ground.

The next minute Jonas walked up to the mantle-piece, and exclaiming, in a tone of vexation, "Run aground again!" took his pipe, snapped it in two, and flung the pieces into the fire! He then stumped back to his room, slamming the door behind him.

"The old fury!" muttered the panting Johnny between his clenched teeth, looking fiercely towards his uncle's room.

"To break his own pipe!" exclaimed Alie. "I never knew him do anything like that before, however angry he might be!"

Johnny took down his cap from its peg, and, in as ill humour as can well be imagined, went out to search for his ball. He took what revenge he could on his formidable uncle, while amusing himself that afternoon by looking over his "Robinson Crusoe." Johnny was fond of his pencil, though he had never learned to draw; and the margins of his books were often adorned with grim heads or odd figures by his hand. There was a picture in "Robinson Crusoe" representing a party of cannibals, as hideous as fancy could represent them, dancing around their fire. Johnny diverted his mind and gratified his malice by doing his best so to alter the foremost figure as to make him appear with a wooden leg, while he drew on his head a straw hat, unmistakably like that of the old sailor, and touched up the features so as to give a dim resemblance to his face. To prevent a doubt as to the meaning of the sketch, Johnny scribbled on the side of the picture,—

He secretly showed the picture to Alie.

"O Johnny! how naughty! What would uncle say if he saw it?"

"We might look out for squalls indeed! but uncle never by any chance looks at a book of that sort."

"I think that you had better rub out the pencilling as fast as you can," said Alie.

"Catch me rubbing it out!" cried Johnny; "it's the best sketch that ever I drew, and as like the old savage as it can stare!"

Late in the evening their mother returned from Brampton, where she had been nursing a sick lady. Right glad were Johnny and Alie to see her sooner than they had ventured to expect. She brought them a few oranges, to show her remembrance of them. Nor was the old sailor forgotten; carefully she drew from her bag and presented to him a new pipe.

The children glanced at each other. Jonas took the pipe with a curious expression on his face, which his sister was at a loss to understand.

"Thank'ee kindly," he said; "I see it'll be a case of—

What he meant was a riddle to every one else present, although not to the reader.

The "try" was very successful on that evening and the following day. Never had Johnny and Alie found their uncle so agreeable. His manner almost approached to gentleness,—it was a calm after a storm.

"Uncle is so very good and kind," said Alie to her brother, as they walked home from afternoon service, "that I wonder how you can bear to have that naughty picture still in your book. He is not in the least like a cannibal, and it seems quite wrong to laugh at him so."

"I'll rub it all out one of these days," replied Johnny; "but I must show it first to Peter Crane. He says that I never hit on a likeness: if he sees that, he'll never say so again!"

The next morning Jonas occupied himself with gathering wild flowers and herbs in the fields. He carried them into his little room, where Johnny heard him whistling "Old Tom Bowling," like one at peace with himself and all the world.

Presently Jonas called to the boy to bring him a knife from the kitchen; a request made in an unusually courteous tone of voice, and with which, of course, Johnny immediately complied.

He found Jonas busy drying his plants, by laying them neatly between the pages of a book, preparatory to pressing them down. What was the terror of Johnny when he perceived that the book whose pages Jonas was turning over for this purpose was no other than his "Robinson Crusoe"!

"Oh! if I could only get it out of his hands before he comes to that horrid picture! Oh! what shall I do? what shall I do?" thought the bewildered Johnny. "Uncle, I was reading that book," at last he mustered courage to say aloud.

"You may read it again to-morrow," was the quiet reply of Jonas.

"Perhaps he will not look at that picture," reflected Johnny. "I wish that I could see exactly which part of the book he is at! He looks too quiet a great deal for any mischief to have been done yet! Dear! dear! I would give anything to have that 'Robinson Crusoe' at the bottom of the sea! I do think that my uncle's face is growing very red!—yes! the veins on his forehead are swelling! Depend on't he's turned over to those unlucky cannibals, and will be ready to eat me like one of them! I'd better make off before the thunder-clap comes!"

"Going to sheer off again, Master Johnny?" said the old sailor, in a very peculiar tone of voice, looking up from the open book on which his finger now rested.

"I've a little business," stammered out Johnny.

"Yes, a little business with me, which you'd better square before you hoist sail. Why, when you made such a good figure of this savage, did you not clap jacket and boots on this little cannibal beside him, and make a pair of 'em 'at home'? I suspect you and I are both in the same boat as far as regards our tempers, my lad!"

Johnny felt it utterly impossible to utter a word in reply.

"I'm afraid," pursued the seaman, closing the book, "that we've both had a bit too much of the savage about us,—too much of the dancing round the fire. But mark me, Jack,—we learn even in that book that a savage, a cannibal may be tamed; and we learn from something far better, that principle,—the noblest principle which can govern either the young or the old,—may, ay, and must, put out the fire of fierce anger in our hearts, and change us from wild beasts to men! So I've said my say," added Jonas with a smile; "and in token of my first victory over my old foe, come here, my boy, and give us your hand!"

"O uncle, I am so sorry!" exclaimed Johnny, with moistened eyes, as he felt the kindly grasp of the old man.

"Sorry are you? and what were you on Saturday when I shook you as a cat shakes a rat?"

"Why, uncle, I own that I was angry."

"Sorry now, and angry then? So it's clear that the mild way has the best effect, to say nothing of the example." And Jonas fell into a fit of musing.

All was fair weather and sunshine in the home on that day, and on many days after. Jonas had, indeed, a hard struggle to subdue his temper, and often felt fierce anger rising in his heart, and ready to boil over in words of passion or acts of violence; but Jonas, as he had endeavoured faithfully to serve his Queen, while he fought under her flag, brought the same earnest and brave sense of duty to bear on the trials of daily life. He never again forgot his resolution, and every day that passed made the restraint which he laid upon himself less painful and irksome to him.

If the conscience of any of my readers should tell him that, by his unruly temper, he is marring the peace of his family, oh! let him not neglect the evil as a small one, but, like the poor old sailor in my story, resolutely struggle against it. For an angry man stirreth up strife, and a furious man aboundeth in transgression.