Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Volume 102, April 30, 1892

Author: Various

Release date: December 31, 2004 [eBook #14544]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Malcolm Farmer, William Flis, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 102, April 30, 1892, by Various, Edited by F. C. Burnand

(By Wullie White, Author of "They Taught Her to Death" "A Pauper in Tulle," "My Cloudy Glare," "Green Pasterns in Picalilli," "Ran Fast to Royston," &c., &c., &c.)

["I now send you," writes this popular and delightful Author, "the latest of the Novels in which I mingle delicate sentiment with Hebridean or Highland scenery, and bring the wisdom of a Londoner to bear directly upon the unsophisticated innocence of a kilt-wearing population. I am now republishing my books in a series. I'll take short odds about my salmon-flies as compared with anyone else's, and am prepared to back my sunsets and cloud-effects against the world. No takers. I thought not. Here goes!"]

I held it in my right hand, toying with it curiously, and not without pleasure. It was merely a long, wooden pen-holder, inky and inert to an unappreciative eye, but to me it was a bright magician, skilled in the painting of glowing pictures, a traveller in many climes, a tried and trusted friend, who had led me safely through many strange adventures and much uncouth dialect. "Old friend," I said, addressing it kindly, "shall you and I set out together on another journey? We have seen many countries, and the faces of many men, and yet, though we are advancing in years, the time has not yet come for me to lay you down, as having no need of you. What say you—shall we start once more?" I hear a confused sound as of men who murmur together, and say, "We have supped full of horrors, and have waded chin-deep in Zulu blood; we have followed the Clergy of the Established Church into the recesses of terrible crimes, and have endured them as they bared their too sensitive consciences to our gaze. We pine for simpler, and more wholesome pleasures. Now," I continued, "if only Queen TITA and the rest will help us, I think we can do something to satisfy this clamour." For all answer, my pen-holder nestled lovingly in my hand. I placed my patent sunset-nib in its mouth, waved it twice, dipped it once, and began.

The weary day was at length sinking peacefully to rest behind the distant hills. The packed and tumbled clouds lay heavily towards the West, where a gaunt jagged tower of rock rose sheer into the sky. And lo! suddenly a broad shaft of blood-red light shot through the brooding cumulus and rested gorgeously upon the landscape. On each side of this a thin silvery veil of mist crept slowly up and hung in impalpable folds. The Atlantic sand stretching away to the North shone with the effulgence of burnished copper. And now brilliant flickers of coloured light, saffron, purple, green and rose danced over the heaven's startled face. The piled clouds opened and showed in the interspace a lurid lake of blood tinged with the pale violet of an Irishwoman's eyes. Great pillars of flame sprang up rebelliously and spread over the burning horizon. Then a strange, soft, yellow and vaporous light raised its twelve bore breech-loading ejector to its shoulder and shot across the Cryanlaughin hills, and the cattle shone red in the green pastures, and everything else glowed, and the whole world burned with the bewildering glare of a stout publican's nose in a London fog. And silence came down upon the everlasting hills whose outlines gleamed in a prismatic—

"That will do," said a mysterious Voice, "the paint-box is exhausted!"

I was shocked at this rude interruption.

"Sir!" I said, "I cannot see you, though I hear your voice. Will you not disclose yourself?"

"Nonsense, man," said the aggravating, but invisible one, "do not waste time. Let us get on with the story. You know what comes next. Revenons à nos saumons. Ha, Ha! spare the rod and spoil the book!"

I was vexed, but I had to obey, and this was the result:

The pools were full of gleaming curves of silver, each one belonging to a separate salmon of gigantic size fresh run from the sea. The foaming Black Water tumbled headlong over its rocks and down its narrow channel. DONALD, the big keeper, stood industriously upon the bank arranging flies. "I hef been told," he observed, "tat ta English will be coming to Styornoway, and there will be no more Gaelic spoken. But perhaps it iss not true, for they will tell many lies. I am a teffle of a liar myself."

And lo! as we watched, the grey sky seemed to be split in two by an invisible wedge, and a purple gleam of light shot—

"Stow that!" said the Voice, "I have allowed you to put in a patch of Gaelic, but I really cannot let you do any more sun-pictures. Try and think that it is a close time for landscapes, and don't let the light shoot again for a bit."

"All right," I retorted, not without annoyance, "but you'll just have to make up your mind to lose that salmon. It was a magnificent forty-pounder, and, if it hadn't been for your ridiculous interruption, we should have landed him splendidly in another six pages."

"As you like," said the Voice.

And now our journey was drawing to a close. Out of the solemn hush of the purple mountains we had passed slowly southwards back to the roar and the turmoil of the London streets. And many friends had said farewell to us. SHEILA with her low, sweet brow, her exquisitely curved lips, and her soft blue eyes had held us enraptured, and we had wept with COQUETTE, and fiercely cheered the WHAUP while he held WATTIE by the heels, and made him say a sweer. And we had talked with MACLEOD and grown mournful with Madcap VIOLET, and had seen many another fresh and charming face, and had talked Gaelic with gusto and discrimination. And Queen TITA had sped with us, and we had adored BELLE, and yet we cried for more. But now the dream-journey was past, and lo! suddenly the whole heaven was blazing with light, and a bright saffron band lay across—

"Steady there!" said the Voice. "Remember your promise!"

MELBOURNE.—It is said, on good authority, that the favourite books of the interesting prisoner now in custody are, the Pilgrim's Progress, an Australian Summary of the Newgate Calendar, and the poetry of the late Dr. Watts. He has also expressed himself as pleased with Mrs. Humphrey Ward's latest work of fiction, though he does not quite approve of the theological opinions of the writer.

PARIS, Tuesday.—The supposed author of the dynamite outrages, is the recipient of numerous presents in prison, sent him by male and female admirers, and persons anxious for his conversion and his autograph. The edition of Thomas à Kempis, recently given him, is a most valuable antique copy; but he complains of the print as unsuited to his eyesight.

MELBOURNE. Later.—The Solicitor engaged on behalf of our interesting prisoner has requested the Government to allow a commission, consisting of the medical superintendents at Broadmore, Hanwell and Colney Hatch, with six other English experts in insanity, to come out to Australia to inquire into the mental condition of the prisoner. A telegram has also been despatched to Lord SALISBURY requesting that the LORD CHIEF JUSTICE OF ENGLAND and an Old Bailey Jury may be sent out to try the case; otherwise there will be "no chance of justice being done." The British PREMIER's reply has not yet been received. It is believed that he is consulting Mr. GOSCHEN about the probable cost of such a step.

MELBOURNE. Latest.—Through the instrumentality of an Official connected with the prison, I am enabled to send you some important information concerning our prisoner which you may take as absolutely authentic. His breakfast this morning consisted of buttered toast, coffee, and poached eggs. He complained that the latter were not new-laid, and became very excited. It has also transpired that he is strangely in favour of Imperial Federation, and he has declared to his gaolers that "The friendship between England and her Colonies ought to be cemented." This expression of opinion has created a profound sensation.

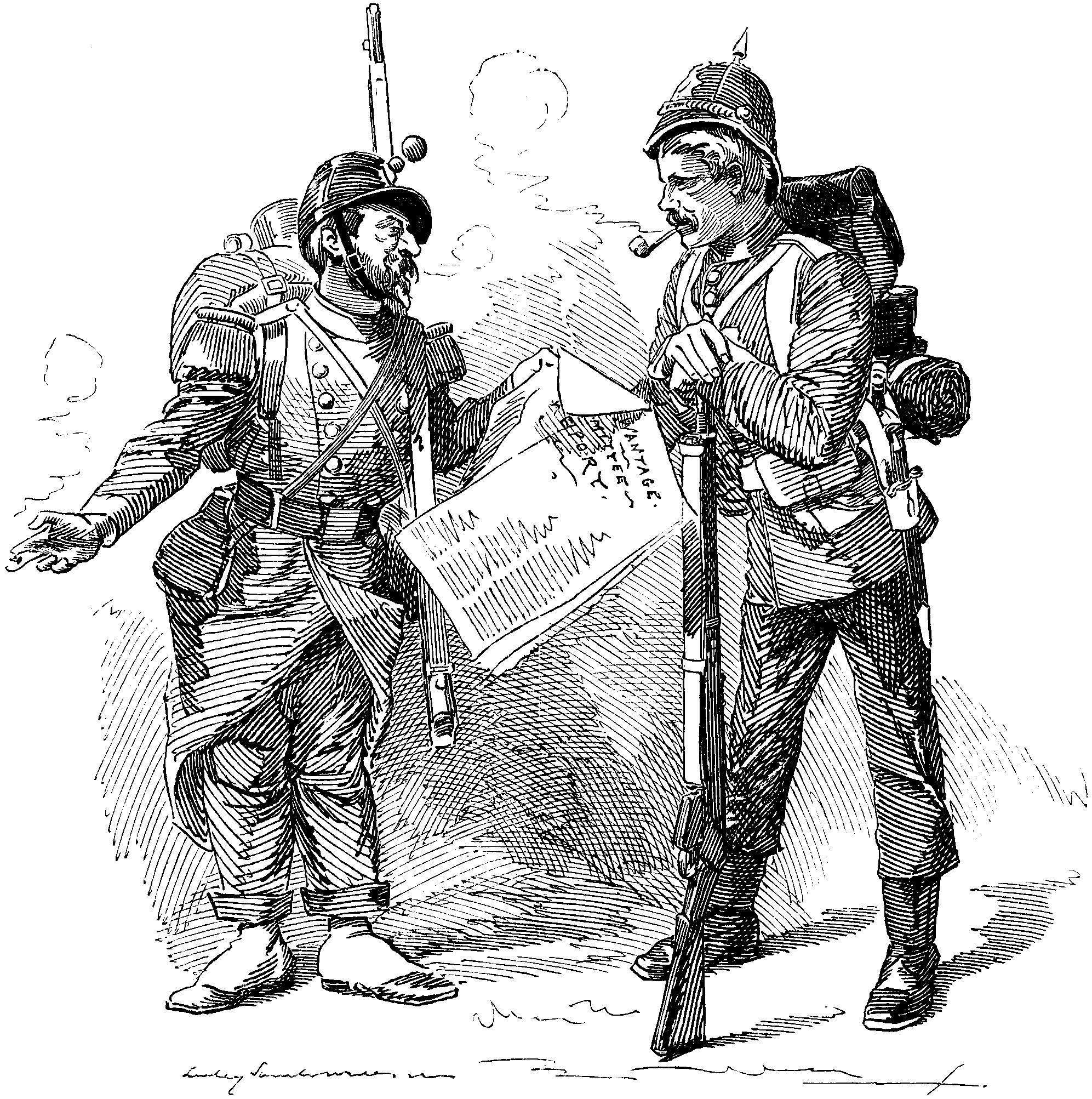

[In the Report of Lord WANTAGE's Committee, it appears that our Home Army costs seventeen and a-half millions per annum. The Duke of CAMBRIDGE doubts if we could rapidly mobilise one Army Corps. Sir EVELYN WOOD holds half the men under him at Aldershot are not equal to doing a day's service, even in England. The Duke of CONNAUGHT says half the battalions under his command are no good for service, cannot even carry their kits, and are not fit to march. Lord WOLSELEY, it is stated, compares the British Army to a "squeezed lemon."]

"Squeezed lemon!" That's encouraging!

Wish Wolseley knew 'ow much it's pleased us.

I'd like to arsk one little thing:

I wonder who it is who's squeezed us?

The whole Report's a thing to cheer;

Makes us feel proud and pleased, oh! very!

And won't the bloomin' furrineer

Over our horacles make merry?

Costs seventeen millions and a arf,

And carn't go nowhere, nor do nothink!

That tots it up! They wouldn't charf,

Eh, BILL, these Big Wigs! What do you think?

Therefore, we're just a useless lot.

After pipe-claying and stiff-starching,

We might be good for stopping shot,

Only that we're not fit for marching!

We cannot carry our own kits!

I say, Bill, ain't we awful duffers?

Not furrin foes, or Frenchy wits,

Could more completely give us snuffers.

CAMBRIDGE, CONNAUGHT, Sir EVELYN WOOD,

All of a mind, for once, about us!

What wonder Bungs dub us no good,

And lackeys, snobs, and street-boys flout us?

I see myself as others see;

A weedy, narrer-chested stripling,

Can't fight, can't march, can't 'ardly see!

And yet young Mister RUDYARD KIPLING

Don't picture hus as kiddies slack,

Wot can't go out without our nurses,

But ups and pats us on the back

In very pooty potry-verses.1

We're much obliged to 'im, I'm sure,

(Though potry ain't my fav'rit reading,)

He's civil, kind and not cock-sure;

Good sense goes sometimes with good-breeding.

So Tommy's best respects to 'im,

At Aldershot we'd like to treat 'im.

Though if he bobs in Evelyn's swim,

He might not know us when we meet 'im!

But, Bill, if all this barney's true

Consarnin' "Our Poor Little Army,"

It must be nuts to Pollyvoo!

He needn't feel a mite alarmy.

Whose fault is it we cost a lot,

And, if war comes, must fail, or fly it?

Well facts is facts, and bounce is rot;

But, blarm it, BILL,—I'd like to try it!

Footnote 1: (return)Mr. Kipling dedicates his "Barrack-Room Ballads" to "TOMMY ATKINS" in these lines:—

I have made for you a song,

An' it may be right or wrong,

But only you can tell me if it's true;

I've tried for to explain.

Both your pleasure and your pain,

And, THOMAS, here's my best respects to you!

Oh, there'll surely come a day

When they'll grant you all your pay

And treat you as a Christian ought to do;

So, until that day comes round,

Heaven keep you safe and sound,

And, Thomas, here's my best respects to you!

Artist (to Customer, who has come to buy on behalf of a large Furnishing Firm in Tottenham Court Road). "HOW WOULD THIS SUIT YOU? 'SUMMER'!"

Customer. "H'M—'SUMMER.' WELL, SIR, THE FACT IS WE FIND THERE'S VERY LITTLE DEMAND FOR GREEN GOODS JUST NOW. IF YOU HAD A LINE OF AUTUMN TINTS NOW—THAT'S THE ARTICLE WE FIND MOST SALE FOR AMONG OUR CUSTOMERS!"

Oh, ain't the Copperashun jest a cummin out in the Hi Art line! Why, dreckly as they let it be nown as they was a willin to make room in their bewtifool Galery for any of the finest picters in the hole country as peepel was wantin to send there, jest to let the world no as they'd got 'em, and that they wos considered good enuff by the LORD MARE and the Sherriffs and all the hole Court of Haldermen, than they came a poring in in such kwantities, that pore Mr. WELSH, the Souperintendant, was obligated to arsk all the hole Court of common Counselmen, what on airth he was to do with 'em, and they told him to hinsult the Libery Committee on the matter, and they, like the lerned gents as they is, told him to take down sum of the werry biggest and the most strikingest as they'd got of their hone Picters and ang 'em up in the Gildhall Westybool, as they calls it, coz it's in the East, I spose, and so make room for a lot of the littel uns as had been sent to 'em, coz they was painted by "Old Marsters," tho' who "Old Marsters" was, I, for one, never could make out, xcep that he must have well deserved his Nickname, considering the number of picters as he must ha' painted. And now cums won of the [pg 207] werry cleverest dodges as even a Welsh Souperintendant of Gildhall picturs coud posserbly have thort on. Why what does he do? but he has taken down out of the Gallery, won of the werry biggest, and one of the werry grandest, Picters of moddern times, and has hung it up in the Westybool aforesaid, to take the whole shine out of all the little uns as so many hemnent swells had been ony too glad to send to Gildhall—"the paytron of the Harts," as I herd a hemnent Halderman call it,—to give 'em the reel stamp as fust rate.

And now what does my thousands of readers suppose was the subjeck of this werry grandest of all Picters? Why, no other than a most magniffisent, splendid, gorgeus, large as life representashun of the LORD MARE's Show, a cummin in all its full bewty and splender from the middel of the Royal Xchange!!

But ewen that isn't all. For the Painter of this trewly hartistic Picter, determined to make his grand work as truthful as it is striking, has lawished his hole sole, so to speak, upon what are undoubtedly the most commanding figures in the hole glorious display, and them is the LORD MARE's three Gentlemen! with their wands of power, and their glorious Unyforms, not forgetting their luvly silk stockins; on this occasion, too, spotless as the rising Sun! To say that they are the hobservd of all hobservers, and the hadmirashun of all the fare sex, and the henvy of the other wun, need not be said, tho they do try to hide their gelesy with a sickly smile.

Need I say that it is surrounded ewery day by a sercle of smiling admirers, who, I have no doubt, come agane and agane, to show it to their admiring friends; and, just to prove its grand success, the werry last time as I was there, I owerheard a smiling gent say to his friend,—"Well, TOM, as this is such a success, it would not supprise me if the same hemnent Hartis was to paint the LORD MARE's Bankwet next year, with all the Nobel Harmy of Waiters arranged in front!" Wich Harmy will be pussinelly konduktid by your faithful

Frenchman. "WELL, MON AMI, YOUR SIR EVELYN VOLSELEY SAY YOU CAN GO NOWHERES AND DO NOSING! YOU ARE A SKVEEZED LEMON!"

Tommy Atkins. "WELL, HANG IT, YOU BLOOMING FURRINEERS HAVEN'T ALWAYS FOUND IT SO!"

SCENE—The Exterior of the Telephone Music Room in the Egyptian Vestibule. The time is about eight. A placard announces, "Manchester Theatre now on"; inside the wickets a small crowd is waiting for the door to be opened. A Cautious Man comes up to the turnstile with the air of a fox examining a trap.

The Cautious Man (to the Commissionnaire). How long can I stay in for sixpence?

The Commissionnaire. Ten Minutes, Sir.

The C.M. Only ten minutes, eh? But, look here, how do I know there'll be anything going on while I'm in there?

Comm. You'll find out that from the instruments, Sir.

The C.M. Ah, I daresay—but what I mean is, suppose there's nothing to hear—between the Acts and all that?

Comm. Comp'ny guarantees there's a performance on while you're in the room, Sir.

The C.M. Yes, but all these other people waiting to get in—How'm I to know I shall get a place?

Comm. (outraged). Look 'ere, Sir, we're the National Telephone Comp'ny with a reputation to lose, and if you've any ideer we want to swindle you, all I can tell you is—stop outside!

The C.M. (suddenly subdued). Oh—er—all right, thought I'd make sure first, you know. Sixpence, isn't it?

[He passes into the enclosure, and joins the crowd.

A Comic Man (in an undertone to his Fiancée). That's a careful bloke, that is. Know the value o' money, he does. It'll have to be a precious scientific sort o' telephone that takes 'im in. He'll 'ave his six-pennorth, if it bursts the machine! Hullo, they're letting us in now.

[The door is slightly opened from within, causing an expectant movement in crowd—the door is closed again.

A Superior Young Lady (to her Admirer). I just caught a glimpse of the people inside. They were all sitting holding things like opera-glasses up to their ears—they did look so ridiculous!

Her Admirer. Well, it's about time they gave us a chance of looking ridiculous, their ten minutes must be up now. I've been trying to think what this put me in mind of. I know. Waiting outside the Pit doors! doesn't it you?

The Sup. Y.L. (languidly, for the benefit of the bystanders). Do they make you wait like this for the Pit?

Her Admirer. Do they make you wait! Why, weren't you and I three-quarters of an hour getting into the Adelphi the other evening?

The Sup. Y.L. (annoyed with him). I don't see any necessity to bawl it out like that if we were.

[The discreetly curtained windows are thrown back, revealing persons inside reluctantly tearing themselves away from their telephones. As the door opens, there is a frantic rush to get places.

An Attendant (soothingly). Don't crush, Ladies and Gentlemen—plenty of room for all. Take your time!

[The crowd stream in, and pounce eagerly on chairs and telephones; the usual Fussy Family waste precious minutes in trying to get seats together, and get separated in the end. Undecided persons flit from one side to another. Gradually they all settle down, and stop their ears with the telephone-tubes, the prevailing expression being one of anxiety, combined with conscious and apologetic imbecility. Nervous people catch the eye of complete strangers across the table, and are seized with suppressed giggles. An Irritable Person finds himself between the Comic Man and a Chatty Old Gentleman.

The Comic Man (to his Fiancée, putting the tube to his ear). Can't get my telephone to tork yet! (Shakes it.) I'll wake 'em up! (Puts the other tube to his mouth.) Hallo—hallo! are you there? Look alive with that Show o' yours, Guv'nor—we ain't got long to stop! (Pretends to listen, and reply.) If you give me any of your cheek, I'll come down and punch your 'ead! (Applies a tube to his eye.) All right, POLLY, they've begun—I can see the 'ero's legs!

Polly. Be quiet, can't you? I can't hold the tubes steady if you will keep making me laugh so. (Listening.) Oh, ALF, I can hear singing—can't you? Isn't it lovely!

The Com. M. It seems to me there's a bluebottle, or something, got inside mine—I can 'ear im!

The Irr. P. (angrily, to himself). How the deuce do they expect—and that infernal organ in the nave has just started booming again—they ought to send out and stop it!

The Chatty O.G. (touching his elbow). I beg your pardon, Sir, but can you inform me what opera it is they're performing at Manchester? The Prima Donna seems to be just finishing a song. Wonderful how one can hear it all!

The Irr. P. (snapping). Very wonderful indeed, under the circumstances! (He corks both ears with the tubes). It's too bad—now there's a confounded string-band beginning outs—(Removes the tube.) Eh, what? (More angrily than ever.) Why, it's in the blanked thing! (He fumbles with the tubes in trying to readjust them. At last he succeeds, and, after listening intently, is rewarded by hearing a muffled and ghostly voice, apparently from the bowels of the earth, say—"Ha, say you so? Then am I indeed the hooshiest hearsher in the whole of Mumble-land!")

The Chatty O.G. (nudging him). How very distinctly you hear the dialogue, Sir, don't you?

[The Irritable Person, without removing the tubes, turns and glares at him savagely, without producing the slightest impression.

Another Ghostly Voice (very audibly). The devil you are!

A Careful Mother. MINNIE, put them down at once, do you hear? I can't have you listening to such language.

Minnie. Why, it's only at Manchester, Mother!

Ghostly Voices and Sounds (as they reach the Irritable Person). "You cursed scoundrel! So it was you who burstled the billiboom, was it? Stand back, there, I'll hork every gordle in his—!" (... Sounds of a scuffle ... A loud female scream, and firing ...) "What have you done?"

The Ch. O.G. Have you any sort of idea what he has done, Sir?

[To the Irritable Person.

The Irr. P. No, Sir, and I'm not likely to have as long as—

[He listens with fierce determination.

First Ghostly Voice. Stop! Hear me—I can explain everything!

Second Do. Do. I will hear nothing, I tell you!

First Do. Do. You shall—you must! Listen. I am the only surviving mumble of your unshle groolier.

The Ch. O.G. (as before). I think it must be a Melodrama and not an Opera after all—from the language!

An Innocent Matron (who is listening, with her eyes devoutly fixed on the Libretto of "The Mountebanks," under the firm conviction that she is in direct communication with the Lyric Theatre.) I always understood The Mountebanks was a musical piece, my dear, didn't you? and even as it is, they don't seem to keep very close to the words, as far as I can follow!

Ghostly Voices (in the Irritable Person's ear as before). "Your wife?" "Yes, my wife, and the only woman in the world I ever loved!"

The Irr. P. (pleased, to himself.) Come, now I'm getting accustomed to it, I can hear capitally!

The Voices. Then why have you—?...I will tell you all. Twenty-five years ago, when a shinder foodle in the Borjeezlers I—

A Still Small Voice (in everybody's ear). TIME, PLEASE.

Everybody (dropping the tubes, startled.) Where did that come from?

The Com. M. They've been and cut it off at the main—just when it was getting interesting!

His Fiancée. Well, I can't say I made out much of the plot myself.

[pg 209]The Com. M. I made out enough to cover a sixpence, anyhow. You didn't expect the telephone to explain it all to you goin' along, and give you cawfee between the Acts, did you?

The Ch. O.G. (sidling affably up to the Irritable Person as he is moving out). Marvellous strides Science has made of late, Sir! Almost incredible. I declare to you, while I was sitting there, I positively felt inclined to ask myself the question—

The Irr. P. Allow me to say, Sir, that another time, if you will obey that inclination, and put the question to yourself instead of other people, you will be a more desirable neighbour in a Telephone Room than, I confess I found you!

[He turns on his heel, indignantly.

The Ch. O.G. (to himself). 'Strordinary what unsociable people one does come across at times! Now I 'm always ready to talk to anybody, I am—don't care who they are. Well—well— [He walks on, musing.

Mamma. "ETHEL DEAR, WHY WON'T YOU SAY GOOD-BYE TO THIS GENTLEMAN? HE IS VERY KIND!"

Ethel. "BECAUSE, MUMMY DEAR, YOU TOLD HIM JUST NOW HE IS 'THE LION OF THE SEASON,'—AND I AM SO FRIGHTENED!"

A masterpiece, worthy of TURNER,

Was mine, there my friends all agree,

No work of a pot-boiling learner,

My "View on the Dee."

A place on the line I expected,

Associate shortly to be!

Hang me, if it isn't rejected,

And marked with a D!

I will not repeat what I uttered

When this was reported to me;

The mere monosyllable muttered

Begins with a D.

["Sir JAMES FERGUSSON does not hesitate to declare his opinion that rudeness or incivility on the part of a Post-Office servant is, next to dishonesty, one of the worst offences he can commit. This notice is not addressed to men alone. Of the young women employed by the department, there are, he says, some, if not many, whom it is impossible to acquit of inattention and levity in the discharge of their official duties. It is Sir JAMES FERGUSSON's intention to ascertain, at short intervals, the effect of this notice on the behaviour of Post-Office officials generally."—Daily Paper.]

SCENE—Interior of a Post Office. Female Employees engaged in congenial pursuits.

First Emp. (ending story). And so she never got the bouquet, after all, and he went to Margate, without even saying good-bye.

Second Emp. (her Friend). Well, that was hard upon her!

First Member of the Public (entering briskly and putting coppers on the counter). Now then, three penny stamps, please!

First Emp. (to her Friend). Yes, as you say, it was hard, as of course the matter of the pic-nic was no affair of hers.

Second Emp. (sympathetically). Of course not! They are all alike, my dear!—all alike!

First Mem. of the Pub. (impatiently). Now then, three penny stamps please!

First Emp. Well, you are in a hurry! (To her Friend). And from that day to this she has never heard from him.

Second Emp. And it would have been so easy to drop her a postcard from Herne Bay.

First Mem. of the Pub. Am I to be kept waiting all day? Three penny postage-stamps, please.

First Emp. (leisurely). What do you want?

First Mem. of the Pub. (angrily). Three penny postage-stamps, and look sharp about it!

First Emp. (giving stamp). Threepence.

First Mem. of the Pub. (furious). A threepenny stamp! I want three penny stamps. Three stamps costing a penny each. See?

First Emp. (with calm unconcern). Then why didn't you say so before? (Supplies stamps and turns to Friend.) Then MARIA of course wanted to go to Birchington.

Second Emp. Why Birchington? Why did she want to go to Birchington?

First Emp. Well—he of course was at Herne Bay.

Second Emp. Ah, now I begin to understand her artfulness.

First Emp. Ah, there you are right, my dear! She was artful! [Enter Second Member of the Public, covered up in cloaks and only showing the tip of his nose.

Second Mem. of the Pub. (in a feeble voice). Can you tell me, please, when the Mail starts for India?

First Emp. Well, the sea air is the sea air. And that reminds me, what do you think of this tobacco-pouch for—

Second Emp. (archly). For I know who! Why, you have got his initials in forget-me-nots!

First Emp. I think them so pretty, and they are very easy to do.

Second Mem. of the Pub. (in a rather louder voice). Can you tell me, please, when the Mail starts for India?

Second Emp. I must say, dear, you have the most perfect taste. Well, he will be ungrateful if he isn't charmed with them! Absolutely charmed!

Second Mem, of the Pub. (louder still). Will you be so good as to say when the Mail starts for India?

First Emp. Oh, you are in a hurry! (To Friend.) Yes, I took a lot of trouble in getting the gold beads. There is only one place where you can get them. They don't sell them at the Stores.

Second Mem. of the Pub. (in a loud tone of voice). Again I ask you when the Mail leaves for India?

Second Emp. And yet you can get almost anything you want there. Only it's a terrible nuisance going from one place to another.

Second Mem. of the Pub. (in a voice of thunder). Silence! You are an impudent set! You are calculated to injure the class to whom you belong! I am ashamed of you!

First Emp. And who may you be?

Second Mem. of the Pub. Whom may I be? I will tell you! (Throws off his disguise.) I am the Postmaster-General!!!

[Scene closes in upon a tableau suggestive of astonishment, contrition and excitement.

ITS LATEST APPLICATION.—Chorus for Royal Academicians, for Monday next:—"Ta-R.A.-R.A.-Boom-to-day!"

["For the third time the International mobilises its battalions.... Already the mere mention of the magical word 'May-Day' throws the bourgeoisie into a state of nervous trembling, and its cowardice only finds refuge in cynicism and ferocity. But whether the wretch (the bourgeoisie) likes it or not, the end draws nigh. Capitalist robbery is going to perish in mud and shame.... The conscious proletariat organises itself, and marches towards its emancipation. You can have it all your own way presently; proletarians of the whole world, serfs of the factory, the men of the workshop, the office, and the shop, who are mercilessly exploited and pitilessly assassinated.... For, lo! '93 reappears on the horizon.... 'Vive l'Internationale des Travailleurs!'"—Manifesto of the May-Day Labour Demonstration Executive Committee.]

Have we lived long enough to have seen one thing, that hate hath no end?

Goddess, and maiden, and queen, must we hail you as Labour's true friend?—

Will you give us a prosperous morrow, and comfort the millions who weep?

Will you give them joy for their sorrow, sweet labour, and satisfied sleep?

Sweet is the fragrance of flowers, and soft are the wings of the dove,

And no goodlier gift is there given than the dower of brotherly love;

But you, O May-Day Medusa, whose glance makes the heart turn cold,

Art a bitter Goddess to follow, a terrible Queen to behold.

We are sick of spouting—the words burn deep and chafe: we are fain,

To rest a little from clap-trap, and probe the wild promise of gain.

For new gods we know not of are acclaimed by all babbledom's breath,

And they promise us love-inspired life—by the red road of hatred and death.

The gods, dethroned and deceased, cast forth—so the chatterers say—

Are banished with Flora and Pan, and behold our new Queen of the May!

New Queen, fresh crowned in the city, flower-drest, her snake-sceptre a rod,

Her orb a decked dynamite bomb, which shall shatter all earth at her nod;

But for us their newest device seems barren, and did they but dare

To bare the new Queen of the May, were she angel or demon when bare?

Time and old gods are at strife; we dwell in the midst thereof,

And they are but foolish who curse, and they are but shallow who scoff.

Let hate die out, take rest, poor workers, be all at peace;

Let the angry battle abate, and the barren bitterness cease!

Ah, pleasant and pastoral picture! Thrice welcome whoever shall bring

The sunshine of love after Winter, the blossoms of joy with the Spring!

Wilt THOU bring it, O new May Queen? If thou canst, come and rule us, and take

The laurel, the palm, and the pæan; all bondage but thine we would break,

And welcome the branch and the dove. But we look, and we hold our breath,

That is not the visage of Love, and beneath the piled blossoms lurks—Death!

A Society all of Love and of Brotherhood! Beautiful dream!

But alas for this Promise of May! Do not Labour's Floralia seem

As flower-feasts fair to her followers? Look on the wreaths at her feet,

Flung by enthusiast hands from the mine, and the mill, and the street,

Piled flower-offerings, thine, Proletariat Queen of the May!

And what means the new Bona Dea? and what would her suppliants say?

Organised strength, solidarity, power to band and to strike,

Hope that is native to Spring,—and Hate, in all seasons alike;

Mutual trust of the many—and menace malign for the few.

Citizen, capitalist,—ah! the hours of your empire seem few,

An empire ill-gendered, unjust, blindly selfish, and heartlessly strong

For the crushing of famishing weakness, the rearing of wealth-founded wrong.

Few, if these throngs have their will, for the fierce proletariat throbs

For revenge on the full-fed Bourgeoisie which ruthlessly harries and robs.

'Tis fired with alarms, and it arms with hot haste for the imminent fray,

For it quakes at the tramp of King Mob, and the thought of this Queen of the May.

The bandit of Capital falls, and shall perish in shame and in filth!

The harvest of Labour's at hand!—The harvest; but red is the tilth,

And the reapers are wrathful and rash, and the swift-wielded sickle that strives

For the sheaves, not the gleaners' scant ears, seems agog for the reaping of—lives!

Assassins of Capital? Aye! And their weakening force will ye meet

With assassins of Labour? Shall Brotherhood redden the field and the street?

Beware of the bad black old lesson! Behold, and look close, and beware!

There are flowers at your newly-built shrine, is the evil old serpent not there?

The sword-edge and snake-bite, though hidden in blossoms, are hatred's old arms.

And what is your May Queen at heart, oh, true hearts, that succumb to her charms?

Dropped and deep in the blossoms, with eyes that flicker like fire,

The asp of Murder lies hid, which with poison shall feed your desire.

More than these things will she give, who looks fairer than all these things?

Not while her sceptre's a snake, and her orb the red horror that rings

Devilish, foul, round the world; while the hiss and the roar are the voice

Of this monstrous new Queen of the May, in whose rule you would bid us rejoice.

LITTLE JACK HORNER,

He sat in the corner,

And cried for his "Mummy!" and "Nuss!"

For, while eating his cake,

He had got by mistake

In a horrid piratical 'bus.

Now, some ten minutes back,

You'd have seen little JACK

From an Aërated Bread Shop emerge,

And proceed down the Strand—

Slice of cake in his hand—

In a crumb-covered suit of blue serge.

To be perfectly frank,

He was bound for the Bank,

For it chanced to be dividend day,

And he jumped on the 'bus,

After reasoning thus—

In his logical juvenile way:—

"Here's a 'bus passing by,

And I cannot see why

I should weary my infantile feet;

I've a copper to spare,

And the authorised fare

Is a penny to Liverpool Street."

As the 'bus cantered on,

Little cake-eating JOHN

In the corner contentedly sat,

And with that one and this

(Whether Mister or Miss)

Had a meteorological chat.

Came a bolt from the blue

When, collecting his due,

The conductor remarked, "Though I thank

That young cake-eating gent

For the penny he's sent,

It's a tuppenny ride to the Bank!"

"You're a pirate!" sobbed JACK,

"And your colours are black!"

But he heard—as he struggled to speak—

The conductor observe,

With remarkable verve,

That he didn't want none of his cheek!

With a want of regard,

He demanded JACK's card.

And young HORNER was summoned next day,

When the poor little lad

Lost the battle, and had

All the costs in addition to pay.

Now the Moral is this:

Little Master and Miss,

Whom I'm writing these verses to please;

If your tiny feet ache,

Then a 'bus you may take,

But be sure it's an L.G.O.C.'s!

From the Figaro for Dimanche, April 17, we make this extract:—

"SPORTS ATHLÉTIQUES.—Le match international de foot ball entre le Stade Français et le Rosslyn Park foot ball Club de Londres sera joué demain sur le terrain du Cursing Club de France à Levallois. L'équipe anglaise est arrivée à Paris hier soir. Le match sera présidé par le marquis de Dufferin."

"The Cursing Club!" What an awful name! For what purpose are they banded together? Is it to curse one another by their gods? to issue forth on premières to damn a new play? What fearful language would be just audible, curses, not loud but deep, during the progress of the Foot-ball Match over which the Marquis of DUFFERIN is to preside! It is all over by now; but the result we have not seen. We hope there is no Cursing Club in England. There existed, once upon a time, in London, a Club with an awful Tartarian name, which might have been a parent society to a Cursing Club. Let us trust—

[*** The Editor puts short the article at this point, being of opinion that "Cursing" is only a misprint for "Coursing;" or, if not, he certainly gives Le Figaro the benefit of the doubt. Note, also, that the match was to be played on "Cursing Club Ground," lent for the occasion, and was not to be played by Members of the "C.C."]

When books and magazines appear,

With heigh! the hopes of a big sale!—

Why, then comes in the cheat o' the year,

And picks their plums, talk, song, or tale.

The white sheets come, each page my "perk,"

With heigh! sweet bards, O how they sing!—

With paste and scissors I set to work;

Shall a stolen song cost anything?

The Poet tirra-lirra chants,

With heigh! with heigh! he must be a J.—

His Summer songs supply my wants;

They cost me nought—but, ah! they pay.

I have served Literature in my time, but now Literature is in my service.

But shall I pay for what comes dear,

To the pale scribes who write,—

For news, and jokes, and stories queer?

Walker! my friends, not quite!

Since filchers may have leave to live,

And vend their "borrowed" budget,

For all my "notions" nix I'll give,

Then sell them as I trudge it.

My traffic is (news) sheets. My father named me AUTOLYCUS, who, being as I am, littered under Mercury, was likewise a snapper-up of unconsidered trifles. With paste and scissors I procured this caparison; and my revenue is the uninquiring public; gallows and gaol are too powerful on the highway; picking and treadmilling are terrors to burglars; but in my line of theft I sleep free from the thought of them. A prize! a prize!...

Jog on, jog on, the foot-pad way,

In the modern Sikes's style-a:

Punctilious fools prefer to pay;

But I at scruples smile-a.

... Ha, ha! what a fool Honesty is! and Trust, his sworn brother, a very simple gentleman ... I understand the business, do it; to have an open ear, a quick eye, and a nimble hand with the shears is necessary for a (literary) cutpurse; a good nose is requisite also, to smell out the good work of other people. I see this is the time that the unjust man doth thrive.

At last! How long ago the time

When England's paltry meanness killed

Her greatest Sculptor in his prime.

And hid his work, now called sublime,

In narrow space so nearly filled!

When, using Art beyond her taste,

Her greatest Captain's tomb he wrought,

That noblest effort was disgraced,—

It seemed to her a needless waste,

The Budget Surplus was her thought.

Now may she, with some sense of shame,

Amend the errors of the past,

Show honour to the Great Duke's name,

Repair the wrong to STEPHENS' fame,

And move the Monument at last!

It is believed that the Rossendale Union of Liberal Clubs, having given a pair of slippers, a rug, and two pieces of cretonne to Mr. GLADSTONE, will also make the following presents, in due course:—

Sir W. L-ws-n.—Twelve dozen Tea-cosies, and ten yards of blue Ribbon.

Mr. L-b-ch-re.—A Jester's cap.

Sir W.V. H-rc-rt.—A Spencer, without arms, but emblazoned with those of the Plantagenets.

Mr. M-cl-re.—A Hood.

Mr. McN-ll.—A knitted Respirator, to be worn in the House.

Lord R. Ch-rch-ll.—Twelve dozen table-cloths, twenty-four dozen Dinner-napkins, and thirty-six dozen Pudding-cloths.

Sir E. Cl-rke.—A scarlet Jersey, inscribed "Salvation Army."

Mr. R. Sp-nc-r.—A Smock Frock.

Mr. B-lf-r.—Some Collars of Irish linen, and one of hemp, the latter to be supplied by the Irish patriots in America.

Mr. E. St-nh-pe.—A Necktie of green poplin, embroidered with shamrocks.

Mr. M. H-ly.—An Ulster.

Col. S-nd-rs-n.—A Cork jacket.

Mr. W. O'Br-n.—A pair of Tr——rs, in fancy cretonne.

Sir G.O. Tr-v-ly-n.—A Coat (reversible).

Mr. C. C-nyb-re.—A Waistcoat (strait).

"I SAY, DUBOIS, YOU DO KNOW HOW TO LAY IT ON THICK, OLD MAN! I LIKE YOUR CHEEK TELLING MISS BROWN SHE SPOKE FRENCH WITHOUT THE LEAST ACCENT!"

"VY, CERTAINEMENT, MON AMI—VIZOUT ZE LEAST FRENCH ACCENT!"

Chairman. I think your name is RICHARD REDMOND?

Witness. I beg pardon, my Lord and Gentlemen—DICK REDMOND—simple, gushing, explosive DICK.

Chair. Have you been known by any other name?

Wit. Off duty, my Lord, I have been called CHARLES WARNER. Nay, why should I not confess it?—CHARLIE WARNER. Yes, my Lord, CHARLIE WARNER!

Chair. You wish to describe how you were enlisted?

Wit. Yes, my Lord. It was in this way. I had returned from some races in a dog-cart with a villain. We stopped at a wayside public-house kept by a comic Irishman.

Chair. Are these details necessary?

Wit. Hear me, my Lord; hear me! I confess it, I took too much to drink. Yes, my Lord, I was drunk! And then a Sergeant in the Dragoon Guards gave me a shilling, and placed some ribands in my pot-hat, and—well—I was a soldier! Yes, a soldier! And as a soldier was refused permission to visit my dying mother!

Chair. Were there no other legal formalities in connection with your enlistment? For instance—Were you not taken before an attesting Magistrate?

Wit. No, my Lord, no! I was carried off protesting, while my villanous friend disappeared with my sweetheart! It was cruel, my Lord and Gentlemen! It was very cruel!

Chair. Did you desert?

Wit. I did, my Lord—after I had obtained a uniform fitting closely to the figure; but it was only that I might obtain the blessing of my mother! And when I returned home the soldiers followed me—and might have killed me!

Chair. How was that?

Wit. When I had taken refuge in a haystack, they prodded the haystack with their swords! And this is life in the Army!

Chair. Were you arrested on discovery?

Wit. No; they spared me that indignity! They saw, my Lord, that my mother was dying, and respectfully fell back while I assisted the old Lady to pass away peacefully. But then, after all, they were men. In spite of their red patrol jackets, brass helmets, and no spurs, they were men, my Lord,—men! And, as soldiers, after I had broken from prison, and was accused of murder, they again released me, because some one promised to buy my discharge!

Chair. And where are you quartered?

Wit. At the Royal Princess's Theatre, Oxford Street, where I have these strange experiences of discipline, and where I am enlisted in the unconventional, not to say illegal, way I have described, nightly; nay, sometimes twice daily!

Chair. And why have you proffered your evidence?

Wit. Because I think the Public ought to know, my Lord, the great services afforded by the most recent Melodrama to the popularity of the Army, and—yes, the cause of recruiting!

[The Witness then withdrew.

All the papers teeming

With, the news of DEEMING

On the shore or ship;

Telling of his tearing

Hair that he was wearing

From his upper lip.

(T-SS-D, rush! Pursue it!

Buy it, bring it, glue it

On your model! Quick!)

Telling how he's looking,

How he likes the cooking,—

Bah, it makes one sick!

Telling of his bearing,

How the crowds are staring,

What may be his fate,

Just what clothes he wore the

Days he came before the

Local Magistrate.

And, verbatim printed

All he's said or hinted

As to any deeds;

Such a chance as this is

Not a paper misses!

Everybody reads!

Would they give such latest

News of best and greatest

Folks? What's that you say?

Who would read of virtue,

Or such news insert? You

Know it would not pay.

So, demand creating

Such supply, they're stating

All that they can tell;

Spite of School-Board teaching,

Culture, science, preaching,

This is sure to sell.

I can quite understand that a young girl may not care much for the mere material dinner. The palate is a pleasure of maturity. The woman of fifty probably includes a menu or two among her most sacred memories; but the young girl is capable of dining on part of a cutlet, any pink sweetmeat, and some tea. But I must confess that I was surprised at another objection to dining-out that a young girl, only at the end of her second season, once made to me. She said that she positively could not stand any longer the conversation of the average young man of Society. I asked her why, and she then asserted that this sort of young man confined himself to flat badinage and personal brag, which he was mistaken in believing to be veiled. What she said was, of course, perfectly true. Civilisation is responsible for the flat badinage, for civilisation requires that conversation shall be light and amusing, but can provide no remedy for slow wits; on the other hand, the personal brag is a relic of the original man. The badinage is the young man's defect in art; the brag is his defect in nature. But I fail to see any objection to such conversation; on the contrary, it is charming because it is so average; you know beforehand just what you will hear and just what you will say, and everything is consequently made easy. The man puts on that kind of talk just as he puts on his dress-coat; both are part of the evening uniform. The motto of the perfect young man of Society is "I resemble." I pointed all this out to the young girl in question, and she retorted that it was a pity that silence was a lost art. However, she continued to dine-out and to take her part in the only possible conversation, and after all Society rather encourages theoretical rebellion, provided that it is accompanied by practical submission.

From the point of view of sentiment, a dinner has less potentialities than a dance; but the dinner may begin what the dance will end; you set light to the fuse in the dining-room, and the explosion takes place six weeks afterwards in someone-else's conservatory. Nothing much can be done on the staircase; but, if you can decently pretend that you have heard of the young man who is taking you in, he will probably like it. If, after a few minutes, you decide that it is worth while to interest the young man, discourage his flat badinage, and encourage his personal brag. The only thing in which it is quite certain that every man will be interested is, the interest someone else takes in him. Later on, he will probably be induced to illustrate the topic of conversation by telling you (if it would not bore you) of a little incident which happened to himself. The incident will be prettily coloured for dinner-table use, and he will make the story prove a merit in himself, which he will take care to disclaim vainly. When he has finished, look very meditatively at your plate, as if you saw visions in it, and then turn on him suddenly with wide eyes—with the right kind of eyelashes, this is effective.

"I suppose you don't know it, Mr. BLANK," you tell him, "but really I can't help saying it. You behaved splendidly—splendidly!"

Droop the eyelashes quickly, and become meditative again. He will deprecate your compliment a little incoherently.

"Not at all, not at all—Miss—er—ASTERISK—I really—assure you—nothing more than any—er—other man would have done. Some other people at the time told me"—(laughs nervously)—"very much—er—what you have just said, but—er—personally, I—really—could never see it, or of course I wouldn't have mentioned it to you."

Your rejoinder will depend a good deal on how far you mean to go, and how much of that kind of thing you think you can stand. If you like, you can drop your handkerchief or your glove when you rise; it will please him to pick it up for you, and he will feel, for a moment, as if he had saved your life.

If you do not want to please the man, but only to show your own superiority, it may perhaps be as well to remember that women are better than men, as a rule, in flat badinage. Men talk best when they are by themselves, but they are liable to be painfully natural at such times. I had some little difficulty in finding this out, but I thought it my duty to know, and—well, I do know.

The correspondence that I have received has not been altogether pleasant. I have had one letter from ETHEL (aged thirteen) saying that she thinks me a mean sneak for prying into other people's Diaries. I can only reply that I was acting for the public good. I have had a sweet letter, however, from "AZALEA." She has been absolutely compelled, by force of circumstances, to allow the distinct attentions of three different men. She does not give the names of the men, only descriptions, but I should advise her to keep the dark one. She can see the will at Somerset House. "JANE" writes to ask what is the best cure for freckles. I do not answer questions of that kind. I have replied to my other correspondents privately.

Arming the Amazons against the Greeks?

That PRIAM SALISBURY tried some few short weeks

Before the present fray. FAWCETTA fair

Had prayed; the question then seemed "in the air,"

And PRIAM proffered then the Franchise-spear,

(A shadowy one, that gave no grounds for fear,)

To poor PENTHESILEA.

Now, ah, now

ROLLITTUS moves, there's going to be a row,

And lo! the mingled ranks of Greece and Troy

Close 'gainst the Amazons. Her steed, a toy,

A hobby-horse, that any maid may mount,

Is not—just now—of any great account.

Her phantom spear will pierce no stout male mail;

But should ROLLITTUS not—(confound him!)—fail,

A female host, well armed, and not on hobbies,

Might prove as dangerous as a batch of Bobbies.

The fair FAWCETTA then must be thrown over;

PENTHESILEA finds no hero-lover

In either host. PRIAM, abroad, is dumb.

Ah, maiden-hosts, man's love for you's a hum.

Each fears you—in the foeman's cohorts thrown,

But neither side desires you in its own!

The false GLADSTONIUS first, he whom you nourish,

A snake in your spare bosoms, dares to flourish

Fresh arms against you; potent, though polite,

He fain would bow you out of the big fight,

Civilly shelve you. "Don't kick up a row,

And—spoil my game! Another day, not now,

There's a dear creature!" CHAMBERLAINIUS, too,

Hard as a nail, and squirmy as a screw,

Sides with the elder hero, just for once;

CHAPLINIUS also, active for the nonce

On the Greek side, makes up the Traitrous Three,

One from each faction! Ah! 'tis sad to see

PENTHESILEA, fierce male foes unite

In keeping female warriors from the fight;

Yet think, look round, and—you may find they're right!

NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.