Title: McClure's Magazine, Vol. 6, No. 5, April, 1896

Author: Various

Release date: January 11, 2005 [eBook #14663]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Richard J. Shiffer, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

The Project Gutenberg eBook, McClure's Magazine, Vol. 6, No. 5, April, 1896, by Various

THE NEW MARVEL IN PHOTOGRAPHY. By H.J.W. Dam. 403

THE RÖNTGEN RAYS IN AMERICA. By Cleveland Moffett. 415

THE HOUSEHOLDERS. By "Q." 421

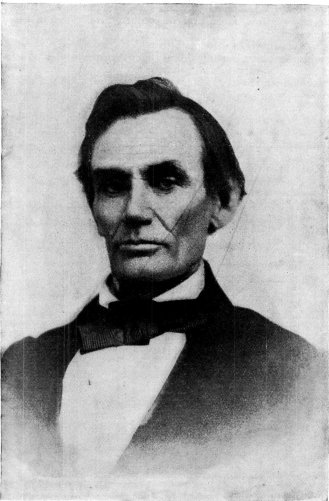

ABRAHAM LINCOLN. By Ida M. Tarbell. 428

Lincoln in the Campaign of 1840. 431

Lincoln's Engagement to Miss Todd. 435

The Lincoln and Shields Duel. 446

Marriage of Lincoln and Miss Todd. 448

"PHROSO." By Anthony Hope. 449

Chapter I. A Long Thing Ending in Poulos. 449

Chapter II. A Conservative Country. 454

Chapter III. The Fever of Neopalia. 459

A CENTURY OF PAINTING. By Will H. Low. 465

"SOLDIER AN' SAILOR TOO." By Rudyard Kipling. 481

RACHEL. By Mrs. E.V. Wilson. 483

CHAPTERS FROM A LIFE. By Elizabeth Stuart Phelps. 490

EDITORIAL NOTES. 496

Twenty Thousand Dollars for Short Stories.496

The McClure's "Early Life of Lincoln." 496

The McClure's New "Life of Grant." 496

New Pictures of Lincoln. 496

The Abraham Lincoln School of Science and Practical Arts. 496

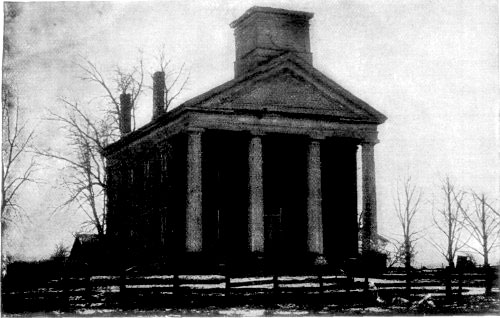

The House in which Lincoln's Parents Were Married--a Correction. 496

PICTURES SHOWING THE DIFFERENCES IN PENETRABILITY TO THE RÖNTGEN RAYS.

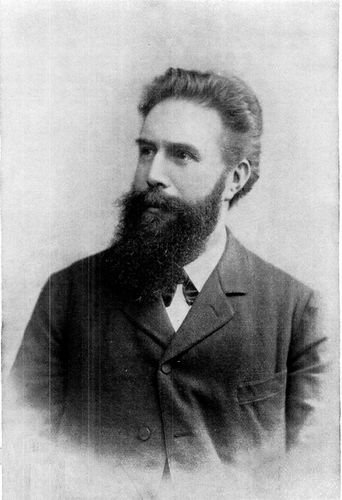

DR. WILLIAM KONRAD RÖNTGEN, DISCOVERER OF THE X RAYS.

PICTURE OF AN ALUMINIUM CIGAR-CASE, SHOWING CIGARS WITHIN.

PHOTOGRAPH OF A LADY'S HAND SHOWING THE BONES, AND A RING ON THE THIRD FINGER.

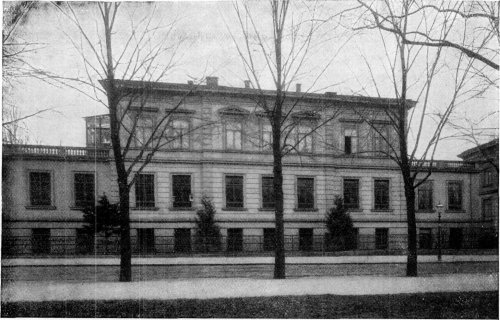

THE PHYSICAL INSTITUTE, UNIVERSITY OF WÜRZBURG.

SKELETON OF A FROG, PHOTOGRAPHED THROUGH THE FLESH.

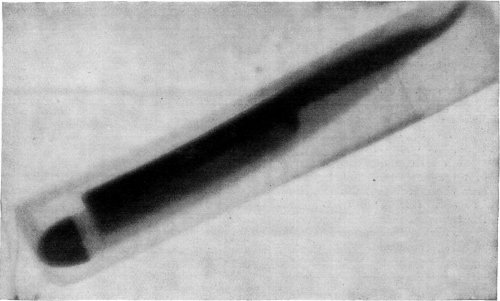

RAZOR-BLADE PHOTOGRAPHED THROUGH A LEATHER CASE AND THE RAZOR-HANDLE.

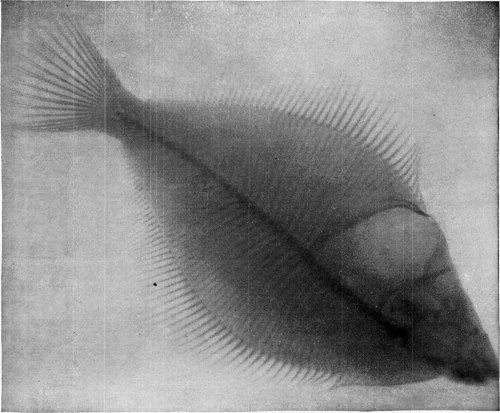

SKELETON OF A FISH PHOTOGRAPHED THROUGH THE FLESH.

A HUMAN FOOT PHOTOGRAPHED THROUGH THE SOLE OF A SHOE.

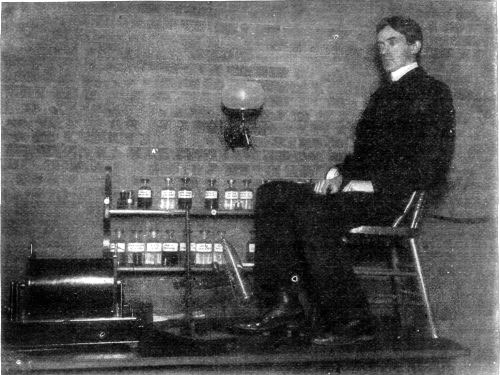

PHOTOGRAPHING A FOOT IN ITS SHOE BY THE RÖNTGEN PROCESS.

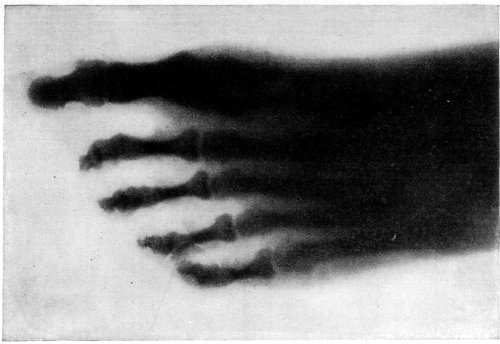

BONES OF A HUMAN FOOT PHOTOGRAPHED THROUGH THE FLESH.

CORK-SCREW, KEY, PENCIL WITH METALLIC PROTECTOR, AND PIECE OF COIN.

COINS PHOTOGRAPHED INSIDE A PURSE.

DR. WILLIAM J. MORTON PHOTOGRAPHING HIS OWN HAND UNDER RÖNTGEN.

A GROUP OF FAMILIAR ARTICLES UNDER THE RÖNTGEN RAYS.

THOMAS A. EDISON EXPERIMENTING WITH THE RÖNTGEN RAYS.

"I ... TRIED A STEP TOWARD THE STAIRS, WITH EYES ALERT"

"HE STOOD SIDEWAYS, ... AND LOOKED AT ME OVER HIS LEFT SHOULDER."

"FACE TO FACE WITH THE REAL HOUSEHOLDER."

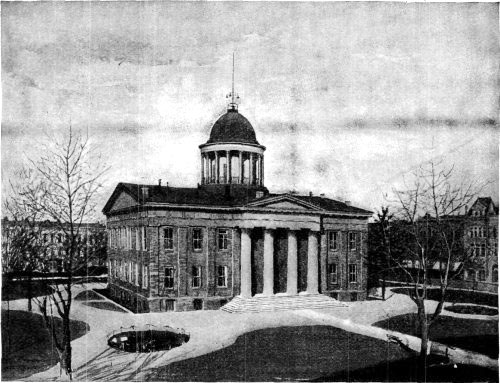

OLD STATE-HOUSE AT SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS.

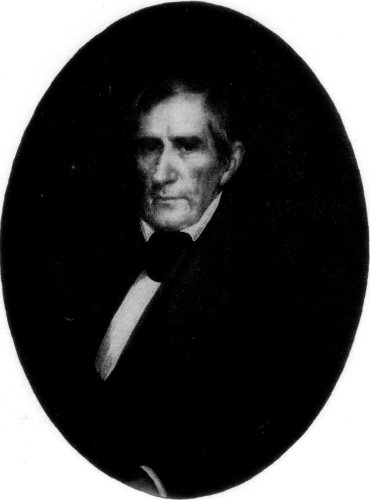

WILLIAM HENRY HARRISON, NINTH PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES.

MISS JULIA JAYNE, ONE OF MISS TODD'S BRIDESMAIDS.

COURT-HOUSE AT TREMONT WHERE LINCOLN RECEIVED WARNING OF SHIELDS'S CHALLENGE.

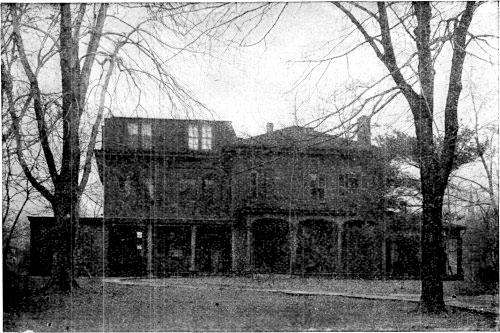

RESIDENCE OF NINIAN W. EDWARDS, SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS.

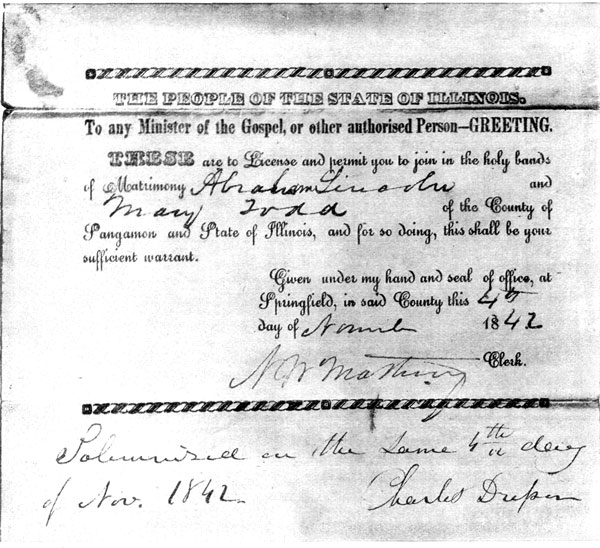

LINCOLN'S MARRIAGE LICENSE AND MARRIAGE CERTIFICATE.

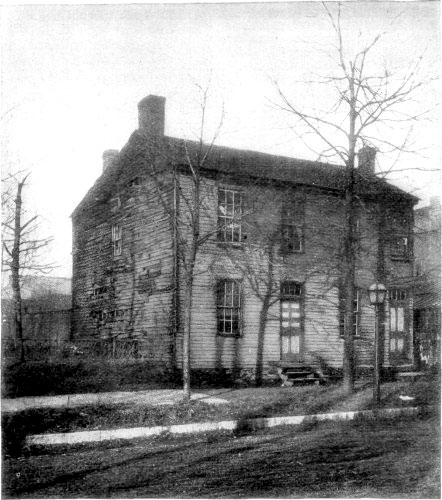

THE GLOBE HOTEL, SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS.

A BROOK IN THE DEPARTMENT OF VAR, FRANCE.

THE EDGE OF THE FOREST (FONTAINEBLEAU).

1 and 3. Flint glass prism (very opaque).

2. Quartz prism, showing transmission of the rays through the thin edges.

4. Prism of heavy glass, more opaque than flint glass.

5. One-cent coin, copper.

6. Five-cent coin, nickel.

7. White-crown glass, 1-1/2 millimetres thick.

8. Blue crown glass, 2 millimetres thick.

9. Yellow crown glass, 1-1/2 millimetres thick.

10. Crown glass, 1 millimetre thick, covered with a very thin layer of gold.

11. Red crown glass, 2 millimetres thick.

12. Block of Iceland spar (very transparent to ordinary light, but very opaque to Röntgen rays).

13. A bit of tinfoil.

14. Aluminium medal, showing faint traces of the design and lettering on both sides, as if it were translucent.

15. Metallic mirror, shows no effect of regular reflection.

16. Bit of sheet-lead, 1 millimetre thick.

17. Quarter-of-a-dollar coin, silver.

18. Piece of thin ebonite, such as is used for photographic plate-holder.

From a photograph by Hanfstaenge, Frankfort-on-the-Main.

From a photograph by A.A.C. Swinton, Victoria Street, London. Exposure, ten minutes.

N all the history of scientific discovery there has never been, perhaps, so general, rapid, and dramatic an effect wrought on the scientific centres of Europe as has followed, in the past four weeks, upon an announcement made to the Würzburg Physico-Medical Society, at their December meeting, by Professor William Konrad Röntgen, professor of physics at the Royal University of Würzburg. The first news which reached London was by telegraph from Vienna to the effect that a Professor Röntgen, until then the possessor of only a local fame in the town mentioned, had discovered a new kind of light, which penetrated and photographed through everything. This news was received with a mild interest, some amusement, and much incredulity; and a week passed. Then, by mail and telegraph, came daily clear indications of the stir which the discovery was making in all the great line of universities between Vienna and Berlin. Then Röntgen's own report arrived, so cool, so business-like, and so truly scientific in character, that it left no doubt either of the truth or of the great importance of the preceding reports. To-day, four weeks after the announcement, Röntgen's name is apparently in every scientific publication issued this week in Europe; and accounts of his experiments, of the experiments of others following his method, and of theories as to the strange new force which he has been the first to observe, fill pages of every scientific journal that comes to hand. And before the necessary time elapses for this article to attain publication in America, it is in all ways probable that the laboratories and lecture-rooms of the United States will also be giving full evidence of this contagious arousal of interest over a discovery so strange that its importance cannot yet be measured, its utility be even prophesied, or its ultimate effect upon long-established scientific beliefs be even vaguely foretold.

From a photograph taken by Mr. P. Spies, director of the "Urania," Berlin.

From a photograph by G. Glock, Würzburg.

The Röntgen rays are certain invisible rays resembling, in many respects, rays of light, which are set free when a high pressure electric current is discharged through a vacuum tube. A vacuum tube is a glass tube from which all the air, down to one-millionth of an atmosphere, has been exhausted after the insertion of a platinum wire in either end of the tube for connection with the two poles of a battery or induction coil. When the discharge is sent through the tube, there proceeds from the anode—that is, the wire which is connected with the positive pole of the battery—certain bands of light, varying in color with the color of the glass. But these are insignificant in comparison with the brilliant glow which shoots from the cathode, or negative wire. This glow excites brilliant phosphorescence in glass and many substances, and these "cathode rays," as they are called, were observed and studied by Hertz; and more deeply by his assistant, Professor Lenard, Lenard having, in 1894, reported that the cathode rays would penetrate thin films of aluminium, wood, and other substances and produce photographic results beyond. It was left, however, for Professor Röntgen to discover that during the discharge another kind of rays are set free, which differ greatly from those described by Lenard as cathode rays The most marked difference between the two is the fact that Röntgen rays are not deflected by a magnet, indicating a very essential difference, while their range and penetrative power are incomparably greater. In fact, all those qualities which have lent a sensational character to the discovery of Röntgen's rays were mainly absent from these of Lenard, to the end that, although Röntgen has not been working in an entirely new field, he has by common accord been freely granted all the honors of a great discovery.

From a photograph by Professors Imbert and Bertin-Sans; reproduced by the courtesy of the "Presse Medicale," Paris. In taking this photograph the experiment was tried of using a diaphragm interposed between the Crookes tube and the plate; and the superior clearness obtained is thought to result from this.

From a photograph taken by Dr. W.L. Robb of Trinity College. The shading in the picture indicates, what was the actual fact, that the blade, which was hollow ground, was thinner in the middle than near the edge.

From a photograph by A.A.C. Swinton, Victoria Street, London. Exposure, four minutes.

Exactly what kind of a force Professor Röntgen has discovered he does not know. As will be seen below, he declines to call it a new kind of light, or a new form of electricity. He has given it the name of the X rays. Others speak of it as the Röntgen rays. Thus far its results only, and not its essence, are known. In the terminology of science it is generally called "a new mode of motion," or, in other words, a new force. As to whether it is or not actually a force new to science, or one of the known forces masquerading under strange conditions, weighty authorities are already arguing. More than one eminent scientist has already affected to see in it a key to the great mystery of the law of gravity. All who have expressed themselves in print have admitted, with more or less frankness, that, in view of Röntgen's discovery, science must forth-with revise, possibly to a revolutionary degree, the long accepted theories concerning the phenomena of light and sound. That the X rays, in their mode of action, combine a strange resemblance to both sound and light vibrations, and are destined to materially affect, if they do not greatly alter, our views of both phenomena, is already certain; and beyond this is the opening into a new and unknown field of physical knowledge, concerning which speculation is already eager, and experimental investigation already in hand, in London, Paris, Berlin, and, perhaps, to a greater or less extent, in every well-equipped physical laboratory in Europe.

This is the present scientific aspect of the discovery. But, unlike most epoch-making results from laboratories, this discovery is one which, to a very unusual degree, is within the grasp of the popular and non-technical imagination. Among the other kinds of matter which these rays penetrate with ease is the human flesh. That a new photography has suddenly arisen which can photograph the bones, and, before long, the organs of the human body; that a light has been found which can penetrate, so as to make a photographic record, through everything from a purse or a pocket to the walls of a room or a house, is news which cannot fail to startle everybody. That the eye of the physician or surgeon, long baffled by the skin, and vainly seeking to penetrate the unfortunate darkness of the human body, is now to be supplemented by a camera, making all the parts of the human body as visible, in a way, as the exterior, appears certainly to be a greater blessing to humanity than even the Listerian antiseptic system of surgery; and its benefits must inevitably be greater than those conferred by Lister, great as the latter have been. Already, in the few weeks since Röntgen's announcement, the results of surgical operations under the new system are growing voluminous. In Berlin, not only new bone fractures are being immediately photographed, but joined fractures, as well, in order to examine the results of recent surgical work. In Vienna, imbedded bullets are being photographed, instead of being probed for, and extracted with comparative ease. In London, a wounded sailor, completely paralyzed, whose injury was a mystery, has been saved by the photographing of an object imbedded in the spine, which, upon extraction, proved to be a small knife-blade. Operations for malformations, hitherto obscure, but now clearly revealed by the new photography, are already becoming common, and are being reported from all directions. Professor Czermark of Graz has photographed the living skull, denuded of flesh and hair, and has begun the adaptation of the new photography to brain study. The relation of the new rays to thought rays is being eagerly discussed in what may be called the non-exact circles and journals; and all that numerous group of inquirers into the occult, the believers in clairvoyance, spiritualism, telepathy, and kindred orders of alleged phenomena, are confident of finding in the new force long-sought facts in proof of their claims. Professor Neusser in Vienna has photographed gall-stones in the liver of one patient (the stone showing snow-white in the negative), and a stone in the bladder of another patient. His results so far induce him to announce that all the organs of the human body can, and will, shortly, be photographed. Lannelougue of Paris has exhibited to the Academy of Science photographs of bones showing inherited tuberculosis which had not otherwise revealed itself. Berlin has already formed a society of forty for the immediate prosecution of researches into both the character of the new force and its physiological possibilities. In the next few weeks these strange announcements will be trebled or quadrupled, giving the best evidence from all quarters of the great future that awaits the Röntgen rays, and the startling impetus to the universal search for knowledge that has come at the close of the nineteenth century from the modest little laboratory in the Pleicher Ring at Würzburg.

From a photograph by Dr. W.L. Robb of Trinity College.

From a photograph by Dr. W.L. Robb of Trinity College. The subject's foot rests on the photographic plate.

On instruction by cable from the editor of this magazine, on the first announcement of the discovery, I set out for Würzburg to see the discoverer and his laboratory. I found a neat and thriving Bavarian city of forty-five thousand inhabitants, which, for some ten centuries, has made no salient claim upon the admiration of the world, except for the elaborateness of its mediæval castle and the excellence of its local beer. Its streets were adorned with large numbers [pg 410] of students, all wearing either scarlet, green, or blue caps, and an extremely serious expression, suggesting much intensity either in the contemplation of Röntgen rays or of the beer aforesaid. All knew the residence of Professor Röntgen (pronunciation: "Renken"), and directed me to the "Pleicher Ring." The various buildings of the university are scattered in different parts of Würzburg, the majority being in the Pleicher Ring, which is a fine avenue, with a park along one side of it, in the centre of the town. The Physical Institute, Professor Röntgen's particular domain, is a modest building of two stories and basement, the upper story constituting his private residence, and the remainder of the building being given over to lecture rooms, laboratories, and their attendant offices. At the door I was met by an old serving-man of the idolatrous order, whose pain was apparent when I asked for "Professor" Röntgen, and he gently corrected me with "Herr Doctor Röntgen." As it was evident, however, that we referred to the same person, he conducted me along a wide, bare hall, running the length of the building, with blackboards and charts on the walls. At the end he showed me into a small room on the right. This contained a large table desk, and a small table by the window, covered with photographs, while the walls held rows of shelves laden with laboratory and other records. An open door led into a somewhat larger room, perhaps twenty feet by fifteen, and I found myself gazing into a laboratory which was the scene of the discovery—a laboratory which, though in all ways modest, is destined to be enduringly historical.

There was a wide table shelf running along the farther side, in front of the two windows, which were high, and gave plenty of light. In the centre was a stove; on the left, a small cabinet, whose shelves held the small objects which the professor had been using. There was a table in the left-hand corner; and another small table—the one on which living bones were first photographed—was near the stove, and a Rhumkorff coil was on the right. The lesson of the laboratory was eloquent. Compared, for instance, with the elaborate, expensive, and complete apparatus of, say, the University of London, or of any of the great American universities, it was bare and unassuming to a degree. It mutely said that in the great march of science it is the genius of man, and not the perfection of appliances, that breaks new ground in the great territory of the unknown. It also caused one to wonder at and endeavor to imagine the great things which are to be done through elaborate appliances with the Röntgen rays—a field in which the United States, with its foremost genius in invention, will very possibly, if not probably, take the lead—when the discoverer himself had done so much with so little. Already, in a few weeks, a skilled London operator, Mr. A.A.C. Swinton, has reduced the necessary time of exposure for Röntgen photographs from fifteen minutes to four. He used, however, a Tesla oil coil, discharged by twelve half-gallon Leyden jars, with an alternating current of twenty thousand volts' pressure. Here were no oil coils, Leyden jars, or specially elaborate and expensive machines. There were only a Rhumkorff coil and Crookes (vacuum) tube and the man himself.

Professor Röntgen entered hurriedly, something like an amiable gust of wind. He is a tall, slender, and loose-limbed man, whose whole appearance bespeaks enthusiasm and energy. He wore a dark blue sack suit, and his long, dark hair stood straight up from his forehead, as if he were permanently electrified by his own enthusiasm. His voice is full and deep, he speaks rapidly, and, altogether, he seems clearly a man who, once upon the track of a mystery which appealed to him, would pursue it with unremitting vigor. His eyes are kind, quick, and penetrating; and there is no doubt that he much prefers gazing at a Crookes tube to beholding a visitor, visitors at present robbing him of much valued time. The meeting was by appointment, however, and his greeting was cordial and hearty. In addition to his own language he speaks French well and English scientifically, which is different from speaking it popularly. These three tongues being more or less within the equipment of his visitor, the conversation proceeded on an international or polyglot basis, so to speak, varying at necessity's demand.

It transpired, in the course of inquiry, that the professor is a married man and fifty years of age, though his eyes have the enthusiasm of twenty-five. He was born near Zurich, and educated there, and completed his studies and took his degree at Utrecht. He has been at Würzburg about seven years, and had made no discoveries which he considered of great importance prior to the one under consideration. These details were given under good-natured protest, he failing to understand why his personality should interest the public. He declined to admire himself or his results in any degree, and laughed at the idea of being famous. The professor is too deeply interested in science to waste any time in thinking about himself. His emperor had fêted, flattered, and decorated him, and he was loyally grateful. It was evident, however, that fame and applause had small attractions for him, compared to the mysteries still hidden in the vacuum tubes of the other room.

From a photograph by A.A.C. Swinton, Victoria Street, London. Exposure, fifty-five seconds.

"Now, then," said he, smiling, and with some impatience, when the preliminary questions at which he chafed were over, "you have come to see the invisible rays."

"Is the invisible visible?"

"Not to the eye; but its results are. Come in here."

He led the way to the other square room mentioned, and indicated the induction coil with which his researches were made, an ordinary Rhumkorff coil, with a spark of from four to six inches, charged by a current of twenty amperes. Two wires led from the coil, through an open door, into a smaller room on the right. In this room was a small table carrying a Crookes tube connected with the coil. The most striking object in the room, however, was a huge and mysterious tin box about seven feet high and four feet square. It stood on end, like a huge packing-case, its side being perhaps five inches from the Crookes tube.

The professor explained the mystery of the tin box, to the effect that it was a device of his own for obtaining a portable dark-room. When he began his investigations he used the whole room, as was shown by the heavy blinds and curtains so arranged as to exclude the entrance of all interfering light from the windows. In the side of the tin box, at the point immediately against the tube, was a circular sheet of aluminium one millimetre in thickness, and perhaps eighteen inches in diameter, soldered to the surrounding tin. To study his rays the professor had only to turn on the current, enter the box, close the door, and in perfect darkness inspect only such light or light effects as he had a right to consider his own, hiding his light, in fact, not under the Biblical bushel, but in a more commodious box.

"Step inside," said he, opening the door, which was on the side of the box farthest from the tube. I immediately did so, not altogether certain whether my skeleton was to be photographed for general inspection, or my secret thoughts held up to light on a glass plate. "You will find a sheet of barium paper on the shelf," he added, and then went away to the coil. The door was closed, and the interior of the [pg 412] box became black darkness. The first thing I found was a wooden stool, on which I resolved to sit. Then I found the shelf on the side next the tube, and then the sheet of paper prepared with barium platino-cyanide. I was thus being shown the first phenomenon which attracted the discoverer's attention and led to the discovery, namely, the passage of rays, themselves wholly invisible, whose presence was only indicated by the effect they produced on a piece of sensitized photographic paper.

A moment later, the black darkness was penetrated by the rapid snapping sound of the high-pressure current in action, and I knew that the tube outside was glowing. I held the sheet vertically on the shelf, perhaps four inches from the plate. There was no change, however, and nothing was visible.

"Do you see anything?" he called.

"No."

"The tension is not high enough;" and he proceeded to increase the pressure by operating an apparatus of mercury in long vertical tubes acted upon automatically by a weight lever which stood near the coil. In a few moments the sound of the discharge again began, and then I made my first acquaintance with the Röntgen rays.

The moment the current passed, the paper began to glow. A yellowish-green light spread all over its surface in clouds, waves, and flashes. The yellow-green luminescence, all the stranger and stronger in the darkness, trembled, wavered, and floated over the paper, in rhythm with the snapping of the discharge. Through the metal plate, the paper, myself, and the tin box, the invisible rays were flying, with an effect strange, interesting, and uncanny. The metal plate seemed to offer no appreciable resistance to the flying force, and the light was as rich and full as if nothing lay between the paper and the tube.

"Put the book up," said the professor.

I felt upon the shelf, in the darkness, a heavy book, two inches in thickness, and placed this against the plate. It made no difference. The rays flew through the metal and the book as if neither had been there, and the waves of light, rolling cloud-like over the paper, showed no change in brightness. It was a clear, material illustration of the ease with which paper and wood are penetrated. And then I laid book and paper down, and put my eyes against the rays. All was blackness, and I neither saw nor felt anything. The discharge was in full force, and the rays were flying through my head, and, for all I knew, through the side of the box behind me. But they were invisible and impalpable. They gave no sensation whatever. Whatever the mysterious rays may be, they are not to be seen, and are to be judged only by their works.

I was loath to leave this historical tin box, but time pressed. I thanked the professor, who was happy in the reality of his discovery and the music of his sparks. Then I said: "Where did you first photograph living bones?"

"Here," he said, leading the way into the room where the coil stood. He pointed to a table on which was another—the latter a small short-legged wooden one with more the shape and size of a wooden seat. It was two feet square and painted coal black. I viewed it with interest. I would have bought it, for the little table on which light was first sent through the human body will some day be a great historical curiosity; but it was "nicht zu verkaufen." A photograph of it would have been a consolation, but for several reasons one was not to be had at present. However, the historical table was there, and was duly inspected.

"How did you take the first hand photograph?" I asked.

The professor went over to a shelf by the window, where lay a number of prepared glass plates, closely wrapped in black paper. He put a Crookes tube underneath the table, a few inches from the under side of its top. Then he laid his hand flat on the top of the table, and placed the glass plate loosely on his hand.

"You ought to have your portrait painted in that attitude," I suggested.

"No, that is nonsense," said he, smiling.

"Or be photographed." This suggestion was made with a deeply hidden purpose.

The rays from the Röntgen eyes instantly penetrated the deeply hidden purpose. "Oh, no," said he; "I can't let you make pictures of me. I am too busy." Clearly the professor was entirely too modest to gratify the wishes of the curious world.

"Now, Professor," said I, "will you tell me the history of the discovery?"

"There is no history," he said. "I have been for a long time interested in the problem of the cathode rays from a vacuum tube as studied by Hertz and Lenard. I had followed theirs and other researches with great interest, and determined, as soon as I had the time, to make some researches of my own. This time I found at the close of last October. I had been at work for some days when I discovered something new."

"What was the date?"

"The eighth of November."

"And what was the discovery?"

"I was working with a Crookes tube covered by a shield of black cardboard. A piece of barium platino-cyanide paper lay on the bench there. I had been passing a current through the tube, and I noticed a peculiar black line across the paper."

"What of that?"

"The effect was one which could only be produced, in ordinary parlance, by the passage of light. No light could come from the tube, because the shield which covered it was impervious to any light known, even that of the electric arc."

"And what did you think?"

"I did not think; I investigated. I assumed that the effect must have come from the tube, since its character indicated that it could come from nowhere else. I tested it. In a few minutes there was no doubt about it. Rays were coming from the tube which had a luminescent effect upon the paper. I tried it successfully at greater and greater distances, even at two metres. It seemed at first a new kind of invisible light. It was clearly something new, something unrecorded."

"Is it light?"

"No."

"Is it electricity?"

"Not in any known form."

"What is it?"

"I don't know."

And the discoverer of the X rays thus stated as calmly his ignorance of their essence as has everybody else who has written on the phenomena thus far.

"Having discovered the existence of a new kind of rays, I of course began to investigate what they would do." He took up a series of cabinet-sized photographs. "It soon appeared from tests that the rays had penetrative power to a degree hitherto unknown. They penetrated paper, wood, and cloth with ease; and the thickness of the substance made no perceptible difference, within reasonable limits." He showed photographs of a box of laboratory weights of platinum, aluminium, and brass, they and the brass hinges all having been photographed from a closed box, without any indication of the box. Also a photograph of a coil of fine wire, wound on a wooden spool, the wire having been photographed, and the wood [pg 414] omitted. "The rays," he continued, "passed through all the metals tested, with a facility varying, roughly speaking, with the density of the metal. These phenomena I have discussed carefully in my report to the Würzburg society, and you will find all the technical results therein stated." He showed a photograph of a small sheet of zinc. This was composed of smaller plates soldered laterally with solders of different metallic proportions. The differing lines of shadow, caused by the difference in the solders, were visible evidence that a new means of detecting flaws and chemical variations in metals had been found. A photograph of a compass showed the needle and dial taken through the closed brass cover. The markings of the dial were in red metallic paint, and thus interfered with the rays, and were reproduced. "Since the rays had this great penetrative power, it seemed natural that they should penetrate flesh, and so it proved in photographing the hand, as I showed you."

A detailed discussion of the characteristics of his rays the professor considered unprofitable and unnecessary. He believes, though, that these mysterious radiations are not light, because their behavior is essentially different from that of light rays, even those light rays which are themselves invisible. The Röntgen rays cannot be reflected by reflecting surfaces, concentrated by lenses, or refracted or diffracted. They produce photographic action on a sensitive film, but their action is weak as yet, and herein lies the first important field of their development. The professor's exposures were comparatively long—an average of fifteen minutes in easily penetrable media, and half an hour or more in photographing the bones of the hand. Concerning vacuum tubes, he said that he preferred the Hittorf, because it had the most perfect vacuum, the highest degree of air exhaustion being the consummation most desirable. In answer to a question, "What of the future?" he said:

"I am not a prophet, and I am opposed to prophesying. I am pursuing my investigations, and as fast as my results are verified I shall make them public."

"Do you think the rays can be so modified as to photograph the organs of the human body?"

In answer he took up the photograph of the box of weights. "Here are already modifications," he said, indicating the various degrees of shadow produced by the aluminium, platinum, and brass weights, the brass hinges, and even the metallic stamped lettering on the cover of the box, which was faintly perceptible.

"But Professor Neusser has already announced that the photographing of the various organs is possible."

"We shall see what we shall see," he said. We have the start now; the developments will follow in time."

"You know the apparatus for introducing the electric light into the stomach?"

"Yes."

"Do you think that this electric light will become a vacuum tube for photographing, from the stomach, any part of the abdomen or thorax?"

The idea of swallowing a Crookes tube, and sending a high frequency current down into one's stomach, seemed to him exceedingly funny. "When I have done it, I will tell you," he said, smiling, resolute in abiding by results.

"There is much to do, and I am busy, very busy," he said in conclusion. He extended his hand in farewell, his eyes already wandering toward his work in the inside room. And his visitor promptly left him; the words, "I am busy," said in all sincerity, seeming to describe in a single phrase the essence of his character and the watchword of a very unusual man.

Returning by way of Berlin, I called upon Herr Spies of the Urania, whose photographs after the Röntgen method were the first made public, and have been the best seen thus far. The Urania is a peculiar institution, and one which it seems might be profitably duplicated in other countries. It is a scientific theatre. By means of the lantern and an admirable equipment of scientific appliances, all new discoveries, as well as ordinary interesting and picturesque phenomena, when new discoveries are lacking, are described and illustrated daily to the public, who pay for seats as in an ordinary theatre, and keep the Urania profitably filled all the year round. Professor Spies is a young man of great mental alertness and mechanical resource. It is the photograph of a hand, his wife's hand, which illustrates, perhaps better than any other illustration in this article, the clear delineation of the bones which can be obtained by the Röntgen rays. In speaking of the discovery he said:

"I applied it, as soon as the penetration of flesh was apparent, to the photograph of a man's hand. Something in it had pained him for years, and the photograph at once exhibited a small foreign object, [pg 415] as you can see;" and he exhibited a copy of the photograph in question. "The speck there is a small piece of glass, which was immediately extracted, and which, in all probability, would have otherwise remained in the man's hand to the end of his days." All of which indicates that the needle which has pursued its travels in so many persons, through so many years, will be suppressed by the camera.

"My next object is to photograph the bones of the entire leg," continued Herr Spies. "I anticipate no difficulty, though it requires some thought in manipulation."

It will be seen that the Röntgen rays and their marvellous practical possibilities are still in their infancy. The first successful modification of the action of the rays so that the varying densities of bodily organs will enable them to be photographed, will bring all such morbid growths as tumors and cancers into the photographic field, to say nothing of vital organs which may be abnormally developed or degenerate. How much this means to medical and surgical practice it requires little imagination to conceive. Diagnosis, long a painfully uncertain science, has received an unexpected and wonderful assistant; and how greatly the world will benefit thereby, how much pain will be saved, and how many lives saved, the future can only determine. In science a new door has been opened where none was known to exist, and a side-light on phenomena has appeared, of which the results may prove as penetrating and astonishing as the Röntgen rays themselves. The most agreeable feature of the discovery is the opportunity it gives for other hands to help; and the work of these hands will add many new words to the dictionaries, many new facts to science, and, in the years long ahead of us, fill many more volumes than there are paragraphs in this brief and imperfect account.

AT the top of the great Sloane laboratory of Yale University, in an experimenting room lined with curious apparatus, I found Professor Arthur W. Wright experimenting with the wonderful Röntgen rays. Professor Wright, a small, low-voiced man, of modest manner, has achieved, in his experiments in photographing through solid substances, some of the most interesting and remarkable results thus far attained in this country. His success is, no doubt, largely due to the fact that for years he had been experimenting constantly with vacuum tubes similar to the Crookes tubes used in producing the cathode rays.

When I arrived, Professor Wright was at work with a Crookes tube, nearly spherical in shape, and about five inches in diameter—the one with which he has taken all his shadow pictures. His best results have been obtained with long exposures—an hour or an hour and a half—and he regards it as of the first importance that the objects through which the Röntgen rays are to be projected be placed as near as possible to the sensitized plate.

It is from a failure to observe this precaution that so many of the shadow pictures show blurred outlines. It is with these pictures as with a shadow of the hand thrown on the wall—the nearer the hand is to the wall, the more distinct becomes the shadow; and this consideration makes Professor Wright doubt whether it will be possible, with the present facilities, to get clearly cut shadow images of very thick objects, or in cases where the pictures are taken through a thick board or other obstacle. The Röntgen rays will doubtless traverse the board, and shadows will be formed upon the plate, but there will be an uncertainty or dimness of outline that will render the results unsatisfactory. It is for this reason that Professor Wright has taken most of his shadow pictures through only the thickness of ebonite in his plate-holder. A most successful shadow picture taken by Professor Wright in this way, shows five objects laid side by side on a large plate—a saw, a case of pocket tools in their cover, a pocket lense opened out as for use, a pair of eye-glasses inside their leather case, and an awl. As will be seen from the accompanying reproduction of this picture, all the objects are photographed with remarkable distinctness, the leather case of the eye-glasses being almost transparent, the wood of the handles of the awl and saw being a little less so, while the glass in the eye-glasses is less transparent than either. In [pg 416] the case of the awl and the saw, the iron stem of the tool shows plainly inside the wooden handle. This photograph is similar to a dozen that have been taken by Professor Wright with equal success. The exposure here was fifty-five minutes.

A more remarkable picture is one taken in the same way, but with a somewhat longer exposure—of a rabbit laid upon the ebonite plate, and so successfully pierced with the Röntgen rays that not only the bones of the body show plainly, but also the six grains of shot with which the animal was killed. The bones of the fore legs show with beautiful distinctness inside the shadowy flesh, while a closer inspection makes visible the ribs, the cartilages of the ear, and a lighter region in the centre of the body, which marks the location of the heart.

Like most experimenters, Professor Wright has taken numerous shadow pictures of the human hand, showing the bones within, and he has made a great number of experiments in photographing various metals and different varieties of quartz and glass, with a view to studying characteristic differences in the shadows produced. A photograph of the latter sort is reproduced on page 401. Aluminium shows a remarkable degree of transparency to the Röntgen rays; so much so that Professor Wright was able to photograph a medal of this metal, showing in the same picture the designs and lettering on both sides of the medal, presented simultaneously in superimposed images. The denser metals, however, give in the main black shadows, which offer little opportunity of distinguishing between them.

As to the nature of the Röntgen rays, Professor Wright is inclined to regard them as a mode of motion through the ether, in longitudinal stresses; and he thinks that, while they are in many ways similar to the rays discovered by Lenard a year or so ago, they still present important characteristics of their own. It may be, he thinks, that the Röntgen rays are the ordinary cathode rays produced in a Crookes tube, filtered, if one may so express it, of the metallic particles carried in their electrical stream from the metal terminal, on passing through the glass. It is well known that the metal terminals of a Crookes tube are steadily worn away while the current is passing; so much so that sometimes portions of the interior of the tube become coated with a metallic deposit almost mirror-like.

As to the future, Professor Wright feels convinced that important results will be achieved in surgery and medicine by the use of these new rays, while in physical science they point to an entirely new field of investigation. The most necessary thing now is to find some means of producing streams of Röntgen rays of greater volume and intensity, so as to make possible greater penetration and distinctness in the images. Thus far only small Crookes tubes have been used, and much is to be expected when larger ones become available; but there is great difficulty in the manufacture of them. It might be possible, Professor Wright thinks, to get good results by using, instead of the Crookes tube, a large sphere of aluminium, which is more transparent to the new rays than glass and possesses considerable strength. It is a delicate question, however, whether the increased thickness of metal necessary to resist the air pressure upon a vacuum would not offset the advantage gained from the greater size. Moreover, it is a matter for experiment still to determine, what kind of an electric current would be necessary to excite such a larger tube with the best results.

Among the most important experiments in shadow photography made thus far in America are those of Dr. William J. Morton of New York, who was the first in this country to use the disruptive discharges of static electricity in connection with the Röntgen discovery, and to demonstrate that shadow pictures may be successfully taken without the use of Crookes tubes. It was the well-known photographic properties of ordinary lightning that made Dr. Morton suspect that cathode rays are produced freely in the air when there is an electric discharge from the heavens. Reasoning thus, he resolved to search for cathode rays in the ten-inch lightning flash he was able to produce between the poles of his immense Holtz machine, probably the largest in this country.

On January 30th he suspended a glass plate, with a circular window in the middle, between the two poles. Cemented to this plate of glass was one of hard rubber, about equal in size, which of course covered the window in the glass. Back of the rubber plate was suspended a photographic plate in the plate-holder, and outside of this, between it and the rubber surface, were ten letters cut from thin copper. Dr. Morton proposed to see if he could not prove the existence of cathode rays between the poles by causing them to picture in shadow, upon the sensitized plate, the letters thus exposed.

In order to do this it was necessary to separate the ordinary electric sparks from [pg 417] the invisible cathode rays which, as Dr. Morton believed, accompanied them. It was to accomplish this that he used the double plates of glass and hard rubber placed, as already described, between the two poles; for while the ordinary electric spark would not traverse the rubber, any cathode rays that might be present would do so with great ease, the circular window in the glass plate allowing them passage there.

In this case the vacuum bulb is charged from Leyden jars which, in their turn, are excited by an induction coil.

The current being turned on, it was found that the powerful electric sparks visible to the eye, unable to follow a straight course on account of the intervening rubber plate, jumped around the two plates in jagged, lightning-like lines, and thus reached the other pole of the machine. But it was noticed that at the same time a faint spray of purplish light was streaming straight through the rubber between the two holes, as if its passage was not interfered with by the rubber plate. It was in company with this stream of violet rays, known as the brush discharge, that the doctor conceived the invisible Röntgen rays to be projected at each spark discharge around the plate; and presently, when the photographic plate was developed, it was found that his conception was based on fact. For there, dim in outline, but unmistakable, were shadow pictures of the ten letters which stand as historic, since they were probably the first shadow pictures in the world taken without any bulb or vacuum tube whatever. These shadow pictures Dr. Morton carefully distinguished from the ordinary blackening effects on the film produced by electrified objects.

Pursuing his experiments with static electricity, Dr. Morton soon found that better results could be obtained by the use of Leyden jars influenced by the Holtz machine, and discharging into a vacuum bulb, as shown in the illustration on this page. This arrangement of the apparatus has the advantage of making it much easier to regulate the electric supply and to modify its intensity, and Dr. Morton finds that in this way large vacuum tubes, perhaps twenty inches in diameter, may be excited to the point of doing practical work without danger of breaking the glass walls. But certain precautions are necessary. When he uses tin-foil electrodes on the outside of the bulb, he protects the tin-foil edges, and, [pg 418] what is more essential, uses extremely small Leyden jars and a short spark gap between the poles of the discharging rods. The philosophy of this is, that the smaller the jars, the greater their number of oscillations per second (easily fifteen million, according to Dr. Lodge's computations), the shorter the wave length, and, therefore, the greater the intensity of effects.

From a photograph by Professor Arthur W. Wright of Yale College, taken through an ebonite plate-holder with fifty-five minutes exposure. It shows a pair of spectacles in their leather case; an awl and a saw, with the iron stem, plainly visible through the wooden handles; a magnifying-glass; and a combination wooden tool-handle with metallic tools stored in the head, and the metallic clamp visible through the lower half.

The next step was to bring more energy into play, still using Leyden jars; and for this purpose Dr. Morton placed within the circuit between the jars a Tesla oscillating coil. He was thus able to use in his shadow pictures the most powerful sparks the machine was capable of producing (twelve inches), sending the Leyden-jar discharge through the primary of the coil, and employing for the excitation of the vacuum tube the "step up" current of the secondary coil with a potential incalculably increased.

While Dr. Morton has in some of his experiments excited his Leyden jars from an induction coil, he thinks the best promise lies in the use of powerful Holtz machines; and he now uses no Leyden jars or converters, thus greatly adding to the simplicity of operations.

In regard to the bulb, Dr. Morton has tested various kinds of vacuum tubes, the ordinary Crookes tubes, the Geissler tubes, and has obtained excellent results from the use of a special vacuum lamp adapted by himself to the purpose. One of his ingenious expedients was to turn to use an ordinary radiometer of large bulb, and, having fitted this with tin-foil electrodes, he found that he was able to get strongly marked shadow pictures. This application of the Röntgen principle will commend itself to many students who, being unable to provide themselves with the rare and expensive Crookes tubes, may buy a radiometer which will serve their purpose excellently in any laboratory supply store, the cost being only a few dollars, while the application of the tin foil electrodes is perfectly simple.

In the-well equipped Jackson laboratory at Trinity College, Hartford, I found Dr. W.L. Robb, the professor of physics, surrounded by enthusiastic students, who were assisting him in some experiments with the new rays. Dr. Robb is the better qualified for this work from the fact that he pursued his electrical studies at the Würzburg University, in the very laboratory where Professor Röntgen made his great discovery. The picture reproduced herewith, showing a human foot inside the shoe, was taken by Dr. Robb. The Crookes tubes used in this and in most of Dr. Robb's experiments are considerably larger than any I have seen elsewhere, being pear-shaped, about eight inches long, and four inches wide at the widest part. It is, perhaps, to the excellence of this tube that Dr. Robb owes part of his success. At any rate, in the foot picture the bones are outlined through shoe and stocking, while every nail in the sole of the shoe shows plainly, although the rays came from above, striking the top of the foot first, the sole resting upon the plate-holder. In other of Dr. Robb's pictures equally fine results were obtained; notably in one of a fish, reproduced herewith, and showing the bony structure of the body; one of a razor, where the lighter shadow proves that the hollow ground portion is almost as thin as the edge; and one of a man's hand, taken for use in a lawsuit, to prove that the bones of the thumb, which had been crushed and broken in an accident, had been improperly set by the attending physician.

Dr. Robb has made a series of novel and important experiments with tubes from which the air has been exhausted in varying degrees, and has concluded from these that it is impossible to produce the Röntgen phenomena unless there is present in the tube an almost perfect vacuum. Through a tube half exhausted, on connecting it with an induction coil, he obtained merely the ordinary series of sparks; in a tube three-quarters exhausted, he obtained a reddish [pg 420] glow from end to end, a torpedo-shaped stream of fire; through a tube exhausted to a fairly high degree—what the electric companies would call "not bad"—he obtained a beautiful steaked effect of bluish striæ in transverse layers. Finally, in a tube exhausted as highly as possible, he obtained a faint fluorescent glow, like that produced in a Crookes tube. This fluorescence of the glass, according to Dr. Robb, invariably accompanies the discharge of Röntgen rays, and it is likely that these rays are produced more abundantly as the fluorescence increases. Just how perfect a vacuum is needed to give the best results remains a matter of conjecture. It is possible, of course, as Tesla believes, that with an absolutely perfect vacuum no results whatever would be obtained.

Dr. Robb has discovered that in order to get the best results with shadow pictures it is necessary to use special developers for the plates, and a different process in the dark-room from the one known to ordinary photographers. In a general way, it is necessary to use solutions designed to affect the ultra-violet rays, and not the visible rays of the spectrum. Having succeeded, after much experiment, in thus modifying his developing process to meet the needs of the case, Dr. Robb finds that he makes a great gain in time of exposure, fifteen minutes being sufficient for the average shadow picture taken through a layer of wood or leather, and half an hour representing an extreme case. In some shadow pictures, as, for instance, in taking a lead-pencil, it is a great mistake to give an exposure exceeding two or three minutes; for the wood is so transparent that with a long exposure it does not show at all, and the effect of the picture is spoiled. Indeed, Dr. Robb finds that there is a constant tendency to shorten the time of exposure, and with good results. For instance, one of the best shadow pictures he had taken was of a box of instruments covered by two thicknesses of leather, two thicknesses of velvet, and two thicknesses of wood; and yet the time of exposure, owing to an accident to the coil, was only five minutes.

Dr. Robb made one very interesting experiment a few days ago in the interest of a large bicycle company which sent to him specimens of carbon steel and nickel steel for the purpose of having him test them with the Röntgen rays, and see if they showed any radical differences in the crystalline structure. Photographs were taken as desired, but at the time of my visit only negative results had been obtained.

Dr. Robb realizes the great desirability of finding a stronger source of Röntgen rays, and has himself begun experimenting with exhaustive bulbs made of aluminium. One of these he has already finished, and has obtained some results with it, but not such as are entirely satisfactory, owing to the great difficulty in obtaining a high vacuum without special facilities.

I also visited Professor U.I. Pupin of Columbia College, who has been making numerous experiments with the Röntgen rays, and has produced at least one very remarkable shadow picture. This is of the hand of a gentleman resident in New York, who, while on a hunting trip in England a few months ago, was so unfortunate as to discharge his gun into his right hand, no less than forty shot lodging in the palm and fingers. The hand has since healed completely; but the shot remain in it, the doctors being unable to remove them, because unable to determine their exact location. The result is that the hand is almost useless, and often painful.

Hearing of this case, Professor Pupin induced the gentleman to allow him to attempt a photograph of the hand. He used a Crookes tube. The distance from the tube to the plate was only five inches, and the hand lay between. After waiting fifty minutes the plate was examined. Not only did every bone of the hand show with beautiful distinctness, but each one of the forty shot was to be seen almost as plainly as if it lay there on the table; and, most remarkable of all, a number of shot were seen through the bones of the fingers, showing that the bones were transparent to the lead.

In making this picture, Professor Pupin excited his tube by means of a powerful Holtz machine, thus following Dr. Morton in the substitution of statical electricity for the more common induction coil.

Professor Pupin sees no reason why the whole skeleton of the human body should not be shown completely in a photograph as soon as sufficiently powerful bulbs can be obtained. He thinks that it would be possible to make Crookes tubes two feet in diameter instead of a few inches, as at present.

Thomas A. Edison has also been devoting himself, with his usual energy, to experiments with the Röntgen rays, and announces confidently that in the near future he will be able to photograph the human brain, through the heavy bones of the skull, and perhaps even to get a shadow picture showing the human skeleton through the tissues of the body.

WILL say this—speaking as accurately as a man may, so long afterwards—that when first I spied the house it put no desire in me but just to give thanks.

For conceive my case. It was near midnight by this; and ever since dusk I had been tracking the naked moors a-foot, in the teeth of as vicious a nor'wester as ever drenched a man to the skin, and then blew the cold home to his marrow. My clothes were sodden; my coat-tails flapped with a noise like pistol shots; my boots squeaked as I went. Overhead the October moon was in her last quarter, and might have been a slice of finger-nail for all the light she afforded. Two-thirds of the time the wrack blotted her out altogether; and I, with my stick clipped tight under my arm-pit, eyes puckered up, and head bent like a butting ram's, but a little aslant, had to keep my wits agog to distinguish the glimmer of the road from the black heath to right and left. For three hours I had met neither man nor man's dwelling, and (for all I knew) was desperately lost. Indeed, at the cross roads, two miles back, there had been nothing for me but to choose the way that kept the wind on my face, and it gnawed me like a dog.

Mainly to allay the stinging of my eyes, I pulled up at last, turned right-about face, leant back against the blast with a hand on my hat, and surveyed the blackness I had traversed. It was at this instant that, far away to the left, a point of light caught my notice, faint but steady; and at once I felt sure it burnt in the window of a house. "The house," thought I, "is a good mile off, beside the other road, and the light must have been an inch over my hat-brim for the last half hour," for my head had been sloped that way. This reflection—that on so wide a moor I had come near missing the information I wanted (and perhaps a supper) by one inch—sent a strong thrill down my back.

I cut straight across the heather towards the light, risking quags and pitfalls. Nay, so heartening was the chance to hear a fellow-creature's voice that I broke into a run, skipping over the stunted gorse that cropped up here and there, and dreading every moment to see the light quenched. "Suppose it burns in an upper window, and the family is going to bed, as would be likely at this hour"—the apprehension kept my eyes fixed on the bright spot, to the frequent scandal of my legs, that [pg 422] within five minutes were stuck full of gorse-prickles.

But the light did not go out, and soon a flicker of moonlight gave me a glimpse of the house's outline. It proved to be a deal more imposing than I looked for—the outline, in fact, of a tall-square barrack with a cluster of chimneys at either end, like ears, and a high wall, topped by the roofs of some outbuildings, concealing the lower windows. There was no gate in this wall, and presently I guessed the reason. I was approaching the place from behind, and the light came from a back window on the first floor.

The faintness of the light also was explained by this time. It shone behind a drab-colored blind, and in shape resembled the stem of a wine-glass, broadening out at the foot—an effect produced by the half-drawn curtains within. I came to a halt, waiting for the next ray of moonlight. At the same moment a rush of wind swept over the chimney-stacks, and on the wind there seemed to ride a human sigh.

On this last point I may err. The gust had passed some seconds before I caught myself detecting this peculiar note, and trying to disengage it from the natural chords of the storm. From the next gust it was absent. And then, to my dismay, the light faded from the window.

I was half-minded to call out when it appeared again, this time in two windows—those next on the right to that where it had shone before. Almost at once it increased in brilliance, as if the person who carried it from the smaller room to the larger were lighting more candles; and now the illumination was strong enough to make fine gold threads of the rain that fell within its radiance, and fling two shafts of warm yellow over the coping of the back wall into the night. During the minute or more that I stood watching, no shadow fell on either blind.

Between me and the wall ran a ditch, into the black obscurity of which the ground at my feet broke sharply away. Setting my back to the storm again, I followed the lip of this ditch around the wall's angle. Here was shelter, and here the ditch seemed to grow shallower. Not wishing, however, to mistake a bed of nettles or any such pitfall for solid earth, I kept pretty wide as I went on. The house was dark on this side, and the wall, as before, had no opening. Close beside the next angle grew a mass of thick gorse bushes, and pushing through these I found myself suddenly on a sound high road, with the wind tearing at me as furiously as ever.

But here was the front; and I now perceived that the surrounding wall advanced some way before the house, so as to form a narrow curtilage. So much of it, too, as faced the road had been whitewashed; which made it an easy matter to find the gate. But as I laid hand on its latch, I had a surprise.

A line of paving-stones led from the gate to the heavy porch; and along the wet surface of these fell a streak of light from the front door, which stood ajar.

That a door should remain six inches open on such a night was astonishing enough, until I entered the court and found it was as still as a room, owing to the high wall, and doubtless the porch gave additional protection. But looking up and assuring myself that all the rest of façade was black as ink, I wondered at the inmates who could be thus careless of their property.

It was here that my professional instincts received the first jog. Abating the sound of my feet on the paving-stones, I went up to the door and pushed it softly. It opened without noise.

I stepped into a fair-sized hall of modern build, paved with red tiles and lit with a small hanging lamp. To right and left were doors leading to the ground-floor rooms. Along the wall by my shoulder ran a line of pegs, on which hung half a dozen hats and great coats, every one of clerical shape; and full in front of me a broad staircase ran up, with a staring Brussels carpet, the colors and pattern of which I can recall as well as to-day's breakfast. Under this staircase was set a stand full of walking-sticks, and a table littered with gloves, brushes, a hand-bell, a riding-crop, one or two dog-whistles, and a bed-room candle, with tinder-box beside it. This, with one notable exception, was all the furniture.

The exception—which turned me cold—was the form of a yellow mastiff dog, curled on a mat beneath the table. The arch of his back was towards me, and one forepaw lay over his nose in a natural posture of sleep. I leant back on the wainscoting, with my eyes tightly fixed on him, and my thoughts flying back, with something of regret, to the storm I had come through.

But a man's habits are not easily denied. At the end of three minutes the dog had not moved, and I was down on the doormat unlacing my soaked boots. [pg 423] Slipping them off, and taking them in my left hand, I stood up, and tried a step towards the stairs, with eyes alert for any movement of the mastiff; but he never stirred. I was glad enough, however, on reaching the stairs, to find them newly built and the carpet thick. Up I went with a glance at every step for the table which now hid the brute's form from me, and never a creak did I wake out of that staircase till I was almost at the first landing, when my toe caught a loose stair-rod, and rattled it in a way that stopped my heart for a moment, and then set it going in double-quick time.

I stood still, with a hand on the rail. My eyes were now on a level with the floor of the landing, out of which branched two passages—one by my right hand, the other to the left, at the foot of the next flight, so placed that I was gazing down the length of it. And almost at the end there fell a parallelogram of light across it from an open door.

A man who has once felt it knows there is only one kind of silence that can fitly be called "dead." This is only to be found in a great house at midnight. I declare that for a few seconds after I rattled the stair-rod you might have cut the silence with a knife. If the house held a clock it ticked inaudibly.

Upon this silence, at the end of a minute, broke a light sound—the clink, clink of a decanter on the rim of a wine-glass. It came from the room where the light was.

Now, perhaps it was that the very thought of liquor put warmth into my cold bones. It is certain that all of a sudden I straightened my back, took the remaining stairs at two strides, and walked down the passage, as bold as brass, with out caring a jot for the noise I made.

In the doorway I halted. The room was long, lined for the most part with books bound in what they call "divinity calf," and littered with papers like a barrister's table on assize day. Before the fireplace, where a few coals burned sulkily, was drawn a leathern elbow chair, and beside it, on the corner of a writing-table, were set an unlit candle and a pile of [pg 424] manuscripts. At the opposite end of the room a curtained door led (I guessed) to the chamber that I had first seen illuminated. All this I took in with the tail of my eye, while staring straight in front, where, in the middle of a great square of carpet between me and the windows, was a table with a red cloth upon it. On this cloth were a couple of wax candles, lit, in silver stands, a tray, and a decanter three parts full of brandy. And between me and the table stood a man.

He stood sideways, leaning a little back, as if to keep his shadow off the threshold, and looked at me over his left shoulder—a bald, grave man, slightly under the common height, with a long clerical coat of preposterous fit hanging loosely from his shoulders, a white cravat, black breeches, and black stockings. His feet were loosely thrust into carpet-slippers. I judged his age at fifty, or thereabouts; but his face rested in the shadow, and I could only note a pair of eyes, very small and alert, twinkling above a large expanse of cheek.

He was lifting a wine-glass from the table at the moment when I appeared, and it trembled now in his right hand. I heard a spilt drop or two fall on the carpet, and this was all the evidence he showed of discomposure.

Setting the glass back, he felt in his breast-pocket for a handkerchief, failed to find one, and rubbed his hands together to get the liquor off his fingers.

"You startled me," he said, in a matter-of-fact tone, turning his eyes upon me, as he lifted his glass again, and emptied it. "How did you find your way in?"

"By the front door," said I, wondering at his unconcern.

He nodded his head slowly.

"Ah! yes; I forgot to lock it. You came to steal, I suppose?"

"I came because I lost my way. I've been travelling this God-forsaken moor since dusk—"

"With your boots in your hand," he put in quietly.

"I took them off out of respect to the yellow dog you keep."

"He lies in a very natural attitude—eh?"

"You don't tell me he was stuffed!"

The old man's eyes beamed a contemptuous pity.

"You are indifferently sharp, my dear sir, for a housebreaker. Come in. Set down those convicting boots, and don't drip pools of water in the very doorway, of all places. If I must entertain a burglar, I prefer him tidy."

He walked to the fire, picked up a poker, and knocked the coals into a blaze. This done, he turned round on me with the poker still in his hand. The serenest gravity sat on his large, pale features.

"Why have I done this?" he asked.

"I suppose to get possession of the poker."

"Quite right. May I inquire your next move?"

"Why," said I, feeling in my tail pocket, "I carry a pistol."

"Which I suppose to be damp?"

"By no means. I carry it, as you see, in an oil-cloth case."

He stopped, and laid the poker carefully in the fender.

"That is a stronger card than I possess. I might urge that by pulling the trigger you would certainly alarm the house and the neighborhood, and put a halter round your neck. I say, I might urge this, and assume you to be an intelligent auditor. But it strikes me as safer to assume you capable of using a pistol with effect at three paces. With what might happen subsequently I will not pretend to be concerned. It is sufficient that I dislike the notion of being perforated. The fate of your neck—" He waved a hand. "Well, I have known you for just five minutes, and feel but moderate interest in your neck. As for the inmates of this house, it will refresh you to hear that there are none. I have lived here two years with a butler and a female cook, both of whom I dismissed yesterday at a moment's notice for conduct which I will not shock your ears by explicitly naming. Suffice it to say, I carried them off yesterday to my parish church, two miles away, married them, and dismissed them in the vestry without characters. I wish you had known that butler—but excuse me; with the information I have supplied, you ought to find no difficulty in fixing the price you will take to clear out of my house instanter."

"Sir," I answered, "I have held a pistol at one or two heads in my time; but never at one stuffed with nobler discretion. Your chivalry does not, indeed, disarm me, but prompts me to desire more of your acquaintance. I have found a gentleman, and must sup with him before I make terms."

The address seemed to please him. He shuffled across the room to a sideboard, and produced a plate of biscuits, another [pg 425] of almonds and dried raisins, a glass and two decanters.

"Sherry and Madeira," he said. "There is also a cold pie in the larder, if you care for it."

"A biscuit will serve," I replied. "To tell the truth, I'm more for the bucket than the manger, as the grooms say; and, by your leave, the brandy you were testing just now is more to my mind than wine."

"There is no water handy."

"There was plenty out of doors to last me with this bottle."

I pulled over a chair, and laid my pistol on the table, and held out the glass for him to fill. Having done so, he helped himself to a glass and a chair, and sat down facing me.

"I was talking, just now, of my late butler," he began, with a sip at his brandy. "Has it struck you that, when confronted with moral delinquency, I am apt to let my indignation get the better of me?"

"Not at all," I answered heartily, refilling my glass.

It appeared that another reply would have pleased him better.

"H'm. I was hoping that, perhaps, I had visited his offence too strongly. As a clergyman, you see, I was bound to be severe; but upon my word, sir, since he went I have felt like a man who has lost a limb."

He drummed with his fingers on the cloth for a few moments, and went on:

"One has a natural disposition to forgive butlers—Pharaoh, for instance, felt it. There hovers around butlers that peculiar atmosphere which Shakespeare noticed as encircling kings, an atmosphere in which common ethics lose their pertinence. But mine was a rare bird—a black swan among butlers. He was more than a butler: he was a quick and brightly-gifted man. Of the accuracy of his taste, and the unusual scope of his endeavor, you will be able to form some opinion when I assure you he modelled himself upon me."

I bowed over my brandy.

"I am a scholar; yet I employed him to read aloud to me, and derived pleasure from his intonation. I talk as a scholar; yet he learned to answer me in language as precise as my own. My cast-off garments fitted him not more irreproachably than did my amenities of manner. Divest him of his tray, and you would find his mode of entering a room hardly distinguishable from my own—the same urbanity, the same alertness of carriage, the same superfine deference towards the weaker sex. All—all my idiosyncrasies I saw reflected in this my mirror; and can you doubt that I was gratified? He was my alter ego—which, by the way, makes it the more extraordinary that it should have been necessary to marry him to the cook."

"Look here," I broke in; "you want a butler."

"Oh, you really grasp that fact, do you?" he retorted.

"And you wish to get rid of me as soon as may be."

"I hope there is no impoliteness in complimenting you on your discernment."

"Your two wishes," said I, "may be reconciled. Let me cease to be your burglar, and let me continue here as your butler."

He leant back, spreading out the fingers of each hand as if the table's edge was a harpsichord, and he stretching octaves upon it.

"Believe me," I went on, "you might do worse. I have been a demy of Magdalen College, Oxford, in my time, and retain some Greek and Latin. I'll undertake to read the Fathers with an accent that shall not offend you. My knowledge of wine is none the worse for having been cultivated in other men's cellars. Moreover, you shall engage the ugliest cook in Christendom, so long as I'm your butler. I've taken a liking to you—that's flat—and I apply for the post."

"I give forty pounds a year," said he.

"And I'm cheap at that price."

He filled up his glass, looking up at me while he did so with the air of one digesting a problem. From first to last his face was grave as a judge's.

"We are too impulsive, I think," was his answer, after a minute's silence. "And your speech smacks of the amateur. You say, 'Let me cease to be your burglar, and let me be your butler.' The mere aspiration is respectable; but a man might as well say, 'Let me cease to write poems; let me paint pictures.' And truly, sir, you impressed me as no expert in your present trade, but a journeyman-housebreaker, if I may say so."

"On the other hand," I argued, "consider the moderation of my demands; that alone should convince you of my desire to turn over a new leaf. I ask for a month's trial; if, at the end of that time, I don't suit, you shall say so, and I'll march from your door with nothing in my pocket but my month's wages. Be hanged, sir! but [pg 426] when I reflect on the amount you'll have to pay to get me to face to-night's storm again, you seem to be getting off dirt-cheap!" cried I, slapping my palm on the table.

"Ah, if you had only known Adolphus!" he exclaimed.

Now, the third glass of clean spirits has always a deplorable effect on me. It turns me from bright to black, from lightness of spirits to extreme sulkiness. I have done more wickedness over this third tumbler than in all the other states of comparative inebriety within my experience. So now I glowered at my companion and rapped out a curse.

"Look here, I don't want to hear any more of Adolphus, and I've a pretty clear notion of the game you're playing. You want to make me drunk, and you're ready to sit prattling there till I drop under the table."

"Do me the favor to remember that you came, and are staying, at your own invitation. As for the brandy, I would remind you that I suggested a milder drink. Try some Madeira."

He handed me the decanter, as he spoke, and I poured out a glass.

"Madeira!" said I, taking a gulp. "Ugh! it's the commonest Marsala!"

I had no sooner said the words than he rose up, and stretched a hand gravely across to me.

"I hope you'll shake it," he said; "though, as a man who after three glasses of neat spirit can distinguish between Madeira and Marsala, you have every right to refuse me. Two minutes ago you offered to become my butler, and I demurred. I now beg you to repeat that offer. Say the word, and I employ you gladly; you shall even have the second decanter (which contains genuine Madeira) to take to bed with you."

We shook hands on our bargain, and catching up a candlestick, he led the way from the room.

Picking up my boots, I followed him along the passage and down the silent staircase. In the hall he paused to stand on tiptoe, and turn up the lamp, which was burning low. As he did so, I found time to fling a glance at my old enemy, the mastiff. He lay as I had first seen him—a stuffed dog, if ever there was one. "Decidedly," thought I, "my wits are to seek, to-night;" and with the same, a sudden suspicion made me turn to my conductor, who had advanced to the left-hand door, and was waiting for me, with hand on the knob.

"One moment," I said; "this is all very pretty, but how am I to know you're not sending me to bed while you fetch in all the countryside to lay me by the heels?"

"I'm afraid," was his answer, "you must be content with my word, as a gentleman, that never, to-night or hereafter, will I breathe a syllable about the circumstances of your visit. However, if you choose, we will return upstairs."

"No; I'll trust you," said I; and he opened the door.

It led into a broad passage, paved with slate, upon which three or four rooms opened. He paused by the second, and ushered me into a sleeping-chamber which, though narrow, was comfortable enough—a vast improvement, at any rate, on the mumper's lodgings I had been used to for many months past.

"You can undress here," he said. "The sheets are aired, and if you'll wait a moment I'll fetch a nightshirt—one of my own."

"Sir, you heap coals of fire on me."

"Believe me that for ninety-nine of your qualities I do not care a tinker's curse: but as a man who, after three tumblers of neat brandy, can tell Marsala from Madeira you are to be taken care of."

He shuffled away, but came back in a couple of minutes with the nightshirt.

"Good-night," he called to me, flinging it in at the door; and without giving me time to return the wish, went his way upstairs.

Now it might be supposed that I was only too glad to toss off my clothes and climb into the bed I had so unexpectedly acquired a right to. But, as a matter of fact, I did nothing of the kind. Instead, I drew on my boots and sat on the bed's edge, blinking at my candle till it died down in its socket, and afterwards at the purple square of window as it slowly changed to gray with the coming of dawn. I was cold to the heart, and my teeth chattered with an ague. Certainly I never suspected my host's word; but was even occupied in framing good resolutions and shaping out an excellent future, when I heard the front door gently pulled to, and a man's footsteps moving quietly to the gate.

The treachery knocked me in a heap for the moment. Then leaping up and flinging my door wide, I stumbled through the uncertain light of the passage into the front hall.

There was a fan-shaped light over the door, and the place was very still and [pg 427] gray. A quick thought, or rather a sudden prophetic guess at the truth, made me turn to the figure of the mastiff curled under the hall table.

I laid my hand on the scruff of his neck. He was quite limp, and my fingers sank into the flesh on either side of the vertebrae. Digging them deeper, I dragged him out into the middle of the hall, and pulled the front door open to see the better.

His throat was gashed from ear to ear.

How many seconds passed after I dropped the senseless lump on the floor, and before I made another movement, it would puzzle me to say. Twice I stirred a foot as if to run out at the door. Then, changing my mind, I stepped over the mastiff, and ran up the staircase. The light no longer shone out into the left-hand passage; but groping down it, I found the study door open, as before, and passed in. A sick light stole through the blinds—enough for me to distinguish the glasses and decanters on the table, and find my way to the curtain that hung before the room where the light had first attracted me.

I pushed the curtain aside, paused for a moment, and listened to the violent beat of my heart; then felt for the door handle and turned it.

All I could see at first; was that the chamber was small; next, that the light patch in a line with the window was the white coverlet of a bed; and next, that somebody, or something, lay on the bed.

I listened again. There was no sound in the room; no heart beating but my own. I reached out a hand to pull up the blind, and drew it back again. I dared not.

The daylight grew, minute by minute, on the dull parallelogram of the blind, and minute by minute that horrible thing on the bed took something of distinctness. The strain beat me at last. I fetched a veritable yell to give myself courage, and, reaching for the cord, pulled up the blind as fast as it would go.