It was his great arms that lifted her feather-weight with

extraordinary sureness and gentleness. (See page 165)

Title: Jaffery

Author: William John Locke

Illustrator: Fortunino Matania

Release date: January 11, 2005 [eBook #14669]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Rick Niles, Charlie Kirschner and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team.

This book on which it has pleased you to bestow your especial affection I dedicate to you with my love. It is a memory of many happy hours and many dreams that we have shared.

You remember how it was begun, one spring morning two years ago, with the opening scene of the first chapter gay before my eyes as I wrote. You remember the excitement of ending it before the Christmas of 1913; so that we could start with free consciences, early in the New Year, on our Egyptian journey.

C'est bien loin, tout cela! War overtook it in its serial course; and now, in book form, it must go out to the world as an expression of the moods and fancies almost of a past incarnation.

These dream figures with whom we delighted, like children, to people our home, are now replaced by other guests tragically real, as big-hearted as those most loved of our shadow-folk. Yet sometimes they seem still to live. . . . While correcting the final proofs we have been tempted to modify the end, to bring the story of Jaffery more or less up to date; but we have felt that any addition would be out of key, so far are we from that happy Christmastide when, in gaiety of heart, I wrote the last words.

Yet we know, you and I, that Jaffery Chayne is even now over there, across the Channel; no longer writing of war, but doing his soldier's work in the thick of it, like a gallant gentleman. And don't you feel that one day he will come again and we shall hear his mighty voice thundering across the lawn. . . ?

W.J.L.

| Facing | |

| Page | |

| It was his great arms that lifted her feather-weight with | |

| extraordinary sureness and gentleness | Frontispiece |

| Where the lonely figure in black and white sat brooding | 64 |

| Jaffery, considerably disconcerted, handled the cleek | 78 |

| He drew out a great thick clump of galley-proofs | 186 |

| "Go! You're nothing but a brute" | 228 |

| Before I realized the danger . . . I was flung aside | 300 |

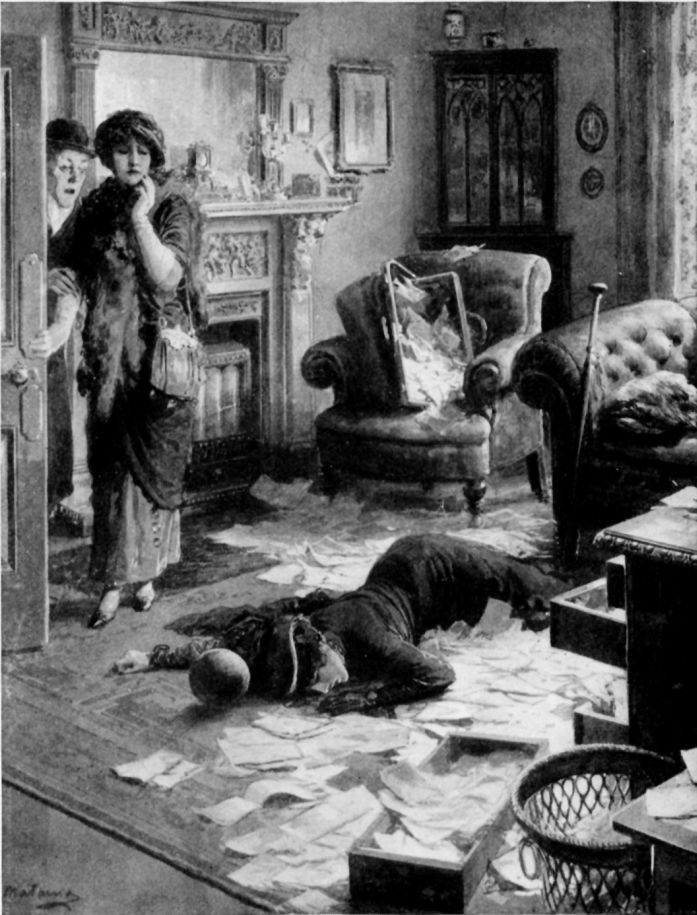

| And there, in a wilderness of ransacked drawers and | |

| strewn papers, . . . lay a tiny, black, moaning | |

| heap of a woman | 316 |

| There is war going on in the Balkans. Jaffery is there | |

| as war correspondent. Liosha is there, too | 350 |

I received a letter the day before yesterday from my old friend, Jaffery Chayne, which has inspired me to write the following account of that dear, bull-headed, Pantagruelian being. I must say that I have been egged on to do so by my wife, of whom hereafter. A man of my somewhat urbane and dilettante temperament does not do these things without being worried into them. I had the inspiration, however. I told Barbara (my wife), and she agreed, at the time, dutifully, that I ought to record our friend Jaffery's doings. But now, womanlike, she declares that the first suggestion, the root germ of the idea, came from her; that the "egging on" is merely the vain man's way of misdefining a woman's serene insistence; that she has given me, out of her intimate knowledge, all the facts of the story—although Jaffery Chayne and Adrian Boldero and poor Tom Castleton, and others involved in the imbroglio, counted themselves as my bosom cronies, while she, poor wretch (a man must get home somewhere), was in the nursery; and that, finally, if she had been taught English grammar and spelling at school, she would have dispensed entirely with my pedantic assistance and written the story herself. Anyhow, man-like, I am broad minded enough to proclaim that it doesn't very much matter. Man and wife are one. She thinks they are one wife. I know they are one husband. Between speculation and knowledge why so futile a thing as a quarrel? I proceed therefore to my originally self-appointed and fantastic task.

But on reflection, before beginning, I must honestly admit that if it had not been for Barbara I should write of these things with half-knowledge. Sex is a queer and incalculable solvent of human confidence. There are certain revelations that men will make only to a man, certain revelations likewise that women will make only to a man. On the other hand, a woman is told things by her sister women and her brother men which, but for her, would never reach a man's ears. So by combining the information obtained from our family encyclopædia under the feminine heading of China with that obtained under the masculine heading of Philosophy, I can, figuratively speaking, like the famous student, issue my treatise on Chinese Philosophy.

One miraculous morning in late May, not so very many years ago, when the parrot-tulips in my garden were expanding themselves wantonly to the sun, and the lilac and laburnum which I caught, as I sat at my table, with the tail of one eye, and the pink may which I caught with the tail of the other, bloomed in splendid arrogance, my quiet outlook on greenery and colour was obscured by a human form. I may mention that my study-table is placed in the bay of a window, on the ground floor. It is a French window, opening on a terrace. Beyond the parapet of the terrace, the garden, with its apple and walnut trees, its beeches, its lawn, its beds of tulips, its lilac and laburnum and may and all sorts of other pleasant things, slopes lazily upwards to a horizon of iron railings separating the garden from a meadow where now and then a cow, when she desires to be peculiarly agreeable to the sight, poses herself in silhouette against the sky. I like to gaze on that adventitious cow. Her ruminatory attitude falls in with mine. . . . But I digress. . . .

I glanced up at the obscuring human form and recognized my wife. She looked, I must confess, remarkably pretty, with her fair hair blond comme les blés, and her mocking cornflower blue eyes, and her mutinous mouth, which has never yet (after all these years) assumed a responsible parent's austerity. She wore a fresh white dress with coquettish bits of blue about the bodice. In her hand she grasped a dilapidated newspaper, the Daily Telegraph, which looked as if she had been to bed in it.

"Am I disturbing you, Hilary?"

She was. She knew she was. But she looked so charming, a petal of spring, a quick incarnation of pink may and forget-me-not and laburnum, that I put down my pen and I smiled.

"You are, my dear," said I, "but it doesn't matter."

"What are you doing?" She remained on the threshold.

"I am writing my presidential address," said I, "for the Grand Meeting, next month, of the Hafiz Society."

"I wonder," said Barbara, "why Hafiz always makes me think of sherbet."

I remonstrated, waving a dismissing hand.

"If that's all you've got to say—"

"But it isn't."

She crossed the threshold, stepped in, swished round the end of my long oak table and took possession of my library. I wheeled round politely in my chair.

"Then, what is it?" I asked.

"Have you read the paper this morning?"

"I've glanced through the Times," said I.

She patted her handful of bedclothing and let fall a blanket and a bed-spread or two—("Look at my beautifully, orderly folded Times," said I, with an indicatory gesture) She looked and sniffed—and shed Vallombrosa leaves of the Daily Telegraph about the library until she had discovered the page for which she was searching. Then she held a mangled sheet before my eyes.

"There!" she cried, "what do you think of that?"

"What do I think of what?" I asked, regarding the acre of print.

"Adrian Boldero has written a novel!"

"Adrian?" said I. "Well, my dear, what of it? Poor old Adrian is capable of anything. Nothing he did would ever surprise me. He might write a sonnet to a Royal Princess's first set of false teeth or steal the tin cup from a blind beggar's dog, and he would be still the same beautiful, charming, futile Adrian."

Barbara pished and insisted. "But this is apparently a wonderful novel. There's a whole column about it. They say it's the most astounding book published in our generation. Look! A work of genius."

"Rubbish, darling," said I, knowing my Adrian.

"Take the trouble to read the notice," said Barbara, thrusting the paper at me in a superior manner.

I took it from her and read. She was right. Somebody calling himself Adrian Boldero had written a novel called "The Diamond Gate," which a usually sane and distinguished critic proclaimed to be a work of genius. He sketched the outline of the story, indicated its peculiar wonder. The review impressed me.

"Barbara, my dear," said I, "this is somebody else—not our Adrian."

"How many people in the world are called Adrian Boldero?"

"Thousands," said I.

She pished again and tossed her pretty head.

"I'll go and telephone straight away to Adrian and find out all about it."

She departed through the library door into the recesses of the house where the telephone has its being. I resumed consideration of my presidential address. But Hafiz eluded me, and Adrian occupied my thoughts. I took up the paper and read the review again; and the more I read, the more absurd did it seem to me that the author of "The Diamond Gate" and my Adrian Boldero could be one and the same person.

You see, we had, all four of us, Adrian, Jaffery Chayne, Tom Castleton and myself, been at Cambridge together, and formed after the manner of youth a somewhat incongruous brotherhood. We knew one another's shortcomings to a nicety and whenever three of the quartette were gathered together, the physical prowess, the morals and the intellectual capacity of the absent fourth were discussed with admirable lack of reticence. So it came to pass that we gauged one another pretty accurately and remained devoted friends. There were other men, of course, on the fringe of the brotherhood, and each of us had our little separate circle; we did not form a mutual admiration society and advertise ourselves as a kind of exclusive, Athos, Porthos, Aramis and d'Artagnan swashbucklery; but, in a quiet way, we recognised our quadruple union of hearts, and talked amazing rubbish and committed unspeakable acts of lunacy and dreamed impossible dreams in a very delightful, and perhaps unsuspected, intimacy. We were now in our middle and late thirties—all save poor Tom Castleton, over whom, in an alien grave, the years of the Lord passed unheeded. Poor old chap! He was the son of the acting-manager of a well-known theatre and used to talk to us of the starry theatre-folk, his family intimates, as though they were haphazard occupants of an omnibus. How we envied him! And he was forever writing plays which he read to us; which plays, I remember, were always on the verge of being produced by Irving. We believed in him firmly. He alone of the little crew had a touch of genius.

Blond, bull-necked Jaffery who rowed in the college boat, and would certainly have got his blue if he had been amenable to discipline and, because he was not, got sent down ingloriously from the University at the beginning of his third year, certainly did not show a sign of it. Adrian was a bit unaccountable. He wrote poems for the Cambridge Review, and became Vice-President of the Union; but he ran disastrously to fancy waistcoats, and shuddered at Dickens because his style was not that of Walter Pater. For myself, Hilary Freeth—well—I am a happy nonentity. I have a very mild scholarly taste which sufficient private means, accruing to me through my late father's acumen in buying a few founder's shares in a now colossal universal providing emporium, enable me to gratify. I am a harmless person of no account. But the other three mattered. They were definite—Jaffery, blatantly definite; Adrian Boldero, in his queer, silky way, incisively definite; Tom Castleton, romantically definite. And poor old Tom was dead. Dear, impossible, feckless fellow. He took a first class in the Classical Tripos and we thought his brilliant career was assured—but somehow circumstances baffled him; he had a terrible time for a dozen years or so, taking pupils, acting, free-lancing in journalism, his father having, in the meanwhile, died suddenly penniless; and then Fortune smiled on him. He secured a professorship at an Australian University. The three of us—Jaffery and Adrian and I—saw him off at Southampton. He never reached Australia. He died on the voyage. Poor old Tom!

So I sat, with the review of Adrian's book before me, looking out at my Pleasant garden, and my mind went irresistibly back to the old days and then wandered on to the present. Tom was dead: I flourished, a comfortable cumberer of the earth; Jaffery was doing something idiotically desperate somewhere or the other—he was a war-correspondent by trade (as regular an employment as that of the maker of hot-cross buns), and a desperado by predilection—I had not heard from him for a year; and now Adrian—if indeed the Adrian Boldero of the review was he—had written an epoch-making novel.

But Adrian—the precious, finnikin Adrian—how on earth could he have written this same epoch-making novel? Beyond doubt he was a clever fellow. He had obtained a First Class in the Law Tripos and had done well in his Bar examination. But after fourteen years or so he was making twopence halfpenny per annum at his profession. He made another three-farthings, say, by selling elegant verses to magazines. He dined out a great deal and spent much of his time at country houses, being a very popular and agreeable person. His other means of livelihood consisted of an allowance of four hundred a year made him by his mother. Beyond the social graces he had not distinguished himself. And now—

"It is Adrian," cried my wife, bursting into the library. "I knew it was. He has had several other glorious reviews which we haven't seen. Isn't it splendid?"

Her eyes danced with loyalty and gladness. Now that I too knew it was our Adrian I caught her enthusiasm.

"Splendid," I echoed. "To think of old Adrian making good at last! I'm more than glad. Telephone at once, dear, for a copy of the book."

"Adrian is bringing one with him. He's coming down to dine and stay the night. He said he had an engagement, but I told him it was rubbish, and he's coming."

Barbara had a despotic way with her men friends, especially with Adrian and Jaffery, who, each after his kind, paid her very pretty homage.

"And now, I've got a hundred things to do, so you must excuse me," said Barbara—for all the world as if I had invited her into my library and was detaining her against her will.

My reply was smilingly ironical. She disappeared. I returned to Hafiz. Soon a bumble-bee, a great fellow splendid in gold and black and crimson, blundered into the room and immediately made furious racket against a window pane. Now I can't concentrate my mind on serious things, if there's a bumble-bee buzzing about. So I had to get up and devote ten minutes to persuading the dunderhead to leave the glass and establish himself firmly on the piece of paper that would waft him into the open air and sunlight. When I lost sight of him in the glad greenery I again came back to my work. But two minutes afterwards my little seven year old daughter, rather the worse for amateur gardening, and holding a cage of white mice in her hand, appeared on the threshold, smiled at me with refreshing absence of apology, darted in, dumped the white mice on an open volume of my precious Turner Macan's edition of Firdusi, and clambering into my lap and seizing pencil and paper, instantly ordained my participation in her favourite game of "head, body and legs."

An hour afterwards a radiant angel of a nurse claimed her for purposes of ablution. I once more returned to Hafiz. Then Barbara put her head in at the door.

"Haven't you thought how delighted Doria will be?"

"I haven't," said I. "I've more important things to think about."

"But," said Barbara, entering and closing the door with soft deliberation behind her and coming to my side—"if Adrian makes a big success, they'll be able to marry."

"Well?" said I.

"Well," said she, with a different intonation. "Don't you see?"

"See what?"

It is wise to irritate your wife on occasion, so as to manifest your superiority. She shook me by the collar and stamped her foot.

"Don't you care a bit whether your friends get married or not?"

"Not a bit," said I.

Barbara lifted the Macan's Firdusi, still suffering the desecration of the forgotten cage of white mice, onto my manuscript and hoisted herself on the cleared corner of the table.

"Doria is my dearest friend. She did my sums for me at school, although I was three years older. If it hadn't been for us, she and Adrian would never have met."

"That I admit," I interrupted. "But having started on the path of crime we're not bound to pursue it to the end."

"You're simply horrid!" she cried. "We've talked for years of the sad story of these two poor young things, and now, when there's a chance of their marrying, you say you don't care a bit!"

"My dear," said I, rising, "what with you and Adrian and a bumble-bee and the child and two white mice, and now Doria, my morning's work is ruined. Let us go out into the garden and watch the starlings resting in the walnut trees. Incidentally we might discuss Doria and Adrian."

"Now you're talking sense," said Barbara.

So we went into the garden—and discussed the formation next autumn of a new rose-bed.

By the afternoon train came Adrian, impeccably vestured and feverish with excitement. Two evening papers which he brandished nervously, proclaimed "The Diamond Gate" a masterpiece. The book had been only out a week—(we country mice knew nothing of it)—and already, so his publisher informed him, repeat orders were coming in from the libraries and distributing agents.

"Wittekind, my publisher, declares it's going to be the biggest thing in first novels ever known. And though I say it as shouldn't, dear old Hilary,"—he clapped me on the shoulder—"it's a damned fine book."

I shall always remember him as he said this, in the pride of his manhood, a defiant triumph in his eyes, his head thrown back, and a smile revealing the teeth below his well-trimmed moustache. He had conquered at last. He had put poor old Jaffery and fortune-favoured me in the shade. At one leap he had mounted to planes beyond our dreams. All this his attitude betokened. He removed the hand from my shoulder and flourished it in a happy gesture.

"My fortune's made," he cried.

"But, my dear fellow," I asked, "why have you sprung this surprise on us? I had no idea you were writing a novel."

He laughed. "No one had. Not even Doria. It was on her account I kept it secret. I didn't want to arouse possible false hopes. It's very simple. Besides, I like being a dark horse. It's exciting. Don't you remember how paralysed you all were when I got my First at Cambridge? Everybody thought I hadn't done a stroke of work—but I had sweated like mad all the time."

This was quite true, the sudden brilliance of the end of Adrian's University career had dazzled the whole of his acquaintance. Barbara, impatient of retrospect, came to the all-important point.

"How does Doria take it?"

He turned on her and beamed. He was one of those dapper, slim-built men who can turn with quick grace.

"She's as pleased as Punch. Gave it to old man Jornicroft to read and insisted on his reading it. He's impressed. Never thought I had it in me. Can't see, however, where the commercial value of it comes in."

"Wait till you show him your first thumping cheque," sympathised my wife.

"I'm going to," he exclaimed boyishly. "I might have done it this afternoon. Wittekind was off his head with delight and if I had asked him to give me a bogus cheque for ten thousand to show to old man Jornicroft, he would have written it without a murmur."

"How much did he really write a cheque for this afternoon?" I asked, knowing (as I have said before) my Adrian.

Barbara looked shocked. "Hilary!" she remonstrated.

But Adrian laughed in high good humour. "He gave me a hundred pounds on account."

"That won't impress Mr. Jornicroft at all," said I.

"It impressed my tailor, who cashed it, deducting a quarter of his bill."

"Do you mean to say, my dear Adrian," I questioned, "that you went to your tailor with a cheque for a hundred pounds and said, `I want to pay you a quarter of what I owe you, will you give me change?'"

"Of course."

"But why didn't you pass the cheque through your banking account and post him your own cheque?"

"Did you ever hear such an innocent?" he cried gaily. "I wanted to impress him, I did. One must do these things with an air. He stuffed my pockets with notes and gold—there has never been any one so all over money as I am at this particular minute—and then I gave him an order for half-a-dozen suits straight away."

"Good God!" I cried aghast. "I've never had six suits of clothes at a time since I was born."

"And more shame for you. Look!" said he, drawing my wife's attention to my comfortable but old and deliberately unfashionable raiment. "I love you, my dear Barbara, but you are to blame."

"Hilary," said my wife, "the next time you go to town you'll order half-a-dozen suits and I'll come with you to see you do it. Who is your tailor, Adrian?"

He gave the address. "The best in London. And if you go to him on my introduction—Good Lord!"—it seemed to amuse him vastly—"I can order half-a-dozen more!"

All this seemed to me, who am not devoid of a sense of humour and an appreciation of the pleasant flippancies of life, somewhat futile and frothy talk, unworthy of the author of "The Diamond Gate" and the lover of Doria Jornicroft. I expressed this opinion and Barbara, for once, agreed with me.

"Yes. Let us be serious. In the first place you oughtn't to allude to Doria's father as 'old man Jornicroft.' It isn't respectful."

"But I don't respect him. Who could? He is bursting with money, but won't give Doria a farthing, won't hear of our marriage, and practically forbids me the house. What possible feeling can one have for an old insect like that?"

"I've never seen any reason," said Barbara, who is a brave little woman, "why Doria shouldn't run away and marry you."

"She would like a shot," cried Adrian; "but I won't let her. How can I allow her to rush to the martyrdom of married misery on four hundred a year, which I don't even earn?"

I looked at my watch. "It's time, my friends," said I, "to dress for dinner. Afterwards we can continue the discussion. In the meanwhile I'll order up some of the '89 Pol Roger so that we can drink to the success of the book."

"The '89 Pol Roger?" cried Adrian. "A man with '89 Pol Roger in his cellar is the noblest work of God!"

"I was thinking," Barbara remarked drily, "of asking Doria to spend a few days here next week."

"All I can say is," he retorted, with his quick turn and smile, "that you are the Divinity Itself."

So, a short time afterwards, a very happy Adrian sat down to dinner and brought a cultivated taste to the appreciation of a now, alas! historical wine, under whose influence he expanded and told us of the genesis and the making of "The Diamond Gate."

Now it is a very odd coincidence, one however which had little, if anything, to do with the curious entanglement of my friend's affairs into which I was afterwards drawn, but an odd coincidence all the same, that on passing from the dining room with Adrian to join Barbara in the drawing room, I found among the last post letters lying on the hall table one which, with a thrill of pleasure, I held up before Adrian's eyes.

"Do you recognise the handwriting?"

"Good Lord!" cried he. "It's from Jaffery Chayne. And"—he scanned the stamp and postmark—"from Cettinje. What the deuce is he doing there?"

"Let us see!" said I.

I opened the letter and scanned it through; then I read it aloud.

"Dear Hilary,

"A line to let you know that I'm coming back soon. I haven't quite finished my job—"

"What was his job?"

"Heaven knows," I replied. "The last time I heard from him he was cruising about the Sargasso Sea."

I resumed my reading.

"—for the usual reason, a woman. If it wasn't for women what a thundering amount of work a man could get through. Anyhow—I'm coming back, with an encumbrance. A wife. Not my wife, thank Olympus, but another man's wife—"

"Poor old devil!" cried Adrian. "I knew he would come a mucker one of these days!"

"Wait," said I, and I read—

"—poor Prescott's wife. I don't think you ever knew Prescott, but he was a good sort. He died of typhoid. Only quaggas and yaks and other iron-gutted creatures like myself can stand Albania. I'm escorting her to England, so look out for us. How's everybody? Do you ever hear of Adrian? If so, collar him. I want to work the widow off on him. She has a goodish deal of money and is a kind of human dynamo. The best thing in the world for Adrian."

Adrian confounded the fellow. I continued—

"Prepare then for the Dynamic Widow. Love to Barbara, the fairy grasshopper—"

"Who's that?"

"My daughter, Susan Freeth. The last time he saw her, she was hopping about in a green jumper—Barbara would give you the elementary costume's commercial name."

"—and yourself," I read. "By the way, do you know of a granite-built, iron-gated, portcullised, barbicaned, really comfortable home for widows?

Yours, Jaffery."

Without waiting for comment from Adrian, I went with the letter into the drawing room, he following. I handed it to Barbara, who ran it through.

"That's just like Jaffery. He tells us nothing."

"I think he has told us everything," said I.

"But who and what and whence is this lady?"

"Goodness knows!" said I.

"Therefore, he has told us nothing," retorted Barbara. "My own belief is that she's a Brazilian."

"But what," asked Adrian, "would a lone Brazilian female be doing in the Balkans?"

"Looking for a husband, of course," said Barbara.

And like all wise men when staggered by serene feminine asseveration we bowed our heads and agreed that nothing could be more obvious.

Some weeks passed; but we heard no more of Jaffery Chayne. If he had planted his widow there, in Cettinje, and gone off to Central Africa we should not have been surprised. On the other hand, he might have walked in at any minute, just as though he lived round the corner and had dropped in casually to see us.

In the meantime events had moved rapidly for Adrian. Everybody was talking about his book; everybody was buying it. The rare phenomenon of the instantaneous success of a first book by an unknown author was occurring also in America. Golden opinions were being backed by golden cash. Adrian continued to draw on his publishers, who, fortunately for them, had an American house. Anticipating possible alluring proposals from other publishers, they offered what to him were dazzling and fantastic terms for his next two novels. He accepted. He went about the world wearing Fortune like a halo. He achieved sudden fame; fame so widespread that Mr. Jornicroft heard of it in the city, where he promoted (and still promotes) companies with monotonous success. The result was an interview to which Adrian came wisely armed with a note from his publisher as to sales up to date, and the amazing contract which he had just signed. He left the house with a father's blessing in his ears and an affianced bride's kisses on his lips. The wedding was fixed for September. Adrian declared himself to be the happiest of God's creatures and spent his days in joy-sodden idleness. His mother, with tears in her eyes, increased his allowance.

The book that created all this commotion, I frankly admit, held me spellbound. It deserved the highest encomiums by the most enthusiastic reviewers. It was one of the most irresistible books I had ever read. It was a modern high romance of love and pity, of tears iridescent with laughter, of strong and beautiful though erring souls; it was at once poignant and tender; it vibrated with drama; it was instinct with calm and kindly wisdom. In my humility, I found I had not known my Adrian one little bit. As the shepherd of old who had a sort of patronizing affection for the irresponsible, dancing, flute-playing, goat-footed creature of the woodland was stricken with panic when he recognised the god, so was I convulsed when I recognised the genius of my friend Adrian. And the fellow still went on dancing and flute-playing and I stared at him open-mouthed.

Mr. Jornicroft, who was a widower, gave a great dinner party at his house in Park Crescent, in honour of the engagement. My wife and I attended, fishes somewhat out of water amid this brilliant but solid assembly of what it pleased Barbara to call "merchantates." She expressed a desire to shrink out of the glare of the diamonds; but she wore her grandmother's pearls, and, being by far the youngest and prettiest matron present, held her own with the best of them. There were stout women, thin women, white-haired women, women who ought to have been white-haired, but were not; sprightly and fashionable women; but besides Barbara, the only other young woman was Doria herself.

She took us aside, as soon as we were released from the formal welcome of Mr. Jornicroft, a thickset man with a very bald head and heavy black moustache.

"The sight of you two is like a breath of fresh air. Did you ever meet with anything so stuffy?"

Now, considering that all these prosperous folks had come to do her homage I thought the remark rather ungracious.

"It's apt to be stuffy in July in London," I said.

She laid her hand on Barbara's wrist and pointed at me with her fan.

"He thinks he's rebuking me. But I don't care. I'm glad to see him all the same. These people mean nothing but money and music-halls and bridge and restaurants—I'm so sick of it. You two mean something else."

"Don't speak sacrilegiously of restaurants, even though you are going to marry a genius," said I. "There is one in Paris to which Adrian will take you straight—like a homing bird."

"Wherever Adrian takes me, it will be beautiful," she said defiantly.

My little critical humour vanished, for she looked so valiantly adorable in her love for the man. She was very small and slenderly made, with dark hair, luminous eyes, and ivory-white complexion, a sensitive nose and mouth, a wisp of nerves and passion. She carried her head high and, for so diminutive a person, appeared vastly important.

Adrian, released from an ex-Lady Mayoress, came up all smiles, to greet us. Doria gave him a glance which in spite of my devotion to Barbara and my abhorrence of hair's breadth deviation from strict monogamy dealt me a pang of unregenerate jealousy. There is only one man in the universe worthy of being so regarded by a woman; and he is oneself. Every true-minded man will agree with me. She was inordinately proud of him; proud too of herself in that she had believed in him and given him her love long before he became famous. Adrian's eyes softened as they met the glance. He turned to Barbara.

"It's in a crowd like this that she looks so mysterious—an Elemental; but whether of Earth, Air, Fire or Water, I shall spend my life trying to discover."

The faintest flush possible mounted to that pure ivory-white cheek of hers. She laughed and caught me by the arm.

"I must carry you to Lady Bagshawe—you're taking her in to dinner. Her husband is Master of the Organ-Grinders' Company—"

"No, no, Doria," said I.

"—Well, it's some city company—I don't know—and she is a museum of diseases and a gazetteer of cure places. Now you know where you are."

She led me to Lady Bagshawe. Soon afterwards we trooped down to dinner, during which I learned more of my inside than I knew before, and more of that of Lady Bagshawe than any of her most fervent adorers in their wildest dreams could have ever hoped to ascertain; during which, also, I endeavoured to convince an unknown, but agreeable lady on my left that I did not play polo, whereat, it seemed, her eight brothers were experts; and that Omar Khayyam was a contemporary not of the Prophet Isaiah, but of William the Conqueror. As for the setting—I am not an observant man—but I had an impression of much gold and silver and rare flora on the table, great gold frames enclosing (I doubt not) costly pictures on the walls, many desirable jewels on undesirable bosoms, strong though unsympathetic masculine faces, and such food and drink as Lucullus, poor fellow, did not live long enough to discover.

When the ladies retired, and we moved up towards our host, I found myself between two groups; one discussing the mercantile depravity of a gentleman called Wilmot, of whom I had never heard, the other arguing on dark dilemmas connected with an Abyssinian loan. A vacant chair happening to be by my side, Adrian, glass in hand, came round the table and sat down.

"How are you getting on?"

"Well," said I. "Very well." I sipped my port. I recognised Cockburn 1870.

"You seemed rather at a loose end."

"When one has 1870 port to drink," said I, "why fritter away its flavour in vain words?"

"It is damned good port," Adrian admitted.

"Earth holds nothing better," said I.

We lapsed into silence amid the talk on each side of us. I confess that I rather surrendered myself to the wine. A little taper for cigarettes happened to be in front of me; I held my glass in its light and lost myself in the wine's pure depths of mystery and colour; and my mind wandered to the lusty sunshine of "Lusitanian summers" that was there imprisoned. I inhaled its fragrance, I accepted its exquisite and spacious generosity. Wine, like bread and oil—"God's three chief words"—is a thing of itself—a thing of earth and air and sun—one of the great natural things, such as the stars and the flowers and the eyes of a dog. Even the most mouth-twisting new wine of Northern Italy has its fascination for me, in that it is essentially something apart from the dust and empty racket of the world; how much more then this radiant vintage suddenly awakened from its slumber in the darkness of forty years. So I mused, as I think an honest man is justified in musing, soberly, over a great wine, when suddenly my left eye caught Adrian's face. He too was musing; but musing on unhappy things, for a hand seemed to have swept his face and wiped the joy from it. He was gazing at his half-emptied glass, with the short stem of which his fingers were nervously toying. There was a quick snap. The stem broke and the wine flowed over the cloth. He started, and with a flash the old Adrian came back, manifesting itself in his smiling dismay, his boyish apology to Mr. Jornicroft for smashing a rare glass, spoiling the tablecloth and wasting precious wine. The incident served to disequilibrate, as one might say, the two discussions on Wilmot and Abyssinia. Coffee came and liqueurs. I bade farewell to Lusitanian dreams and found myself in heart to heart conversation with my neighbour on the right, a florid, simple-minded sugar-broker, a certain next-year's Sheriff of the City of London, whose consuming ambition was to become a member of the Athenæum Club. When I informed him that I was privileged to enter that Valley of Dry Bones—my late father, an eminent Assyriologist and a disastrous Master of Fox hounds, had put me up for all sorts of weird institutions, I think, before I was born—my sugar broker almost fell at my feet and worshipped me. Although I told him that the premises were overrun with Bishops and that we had laid down all kinds of episcopicide to no avail, he refused to be disillusioned. I told him that on the occasion of my last visit to the Megatherium—Thackeray, I explained—a Royal Academician, with whom I had a slight acquaintance, reading desolate "The Hibbert Journal" in the smoking-room, embraced me as fondly as the austerity of the place permitted and related a non-drawing-room story which was current at my preparatory school—and that in the library I ran into an equally desolate, though even less familiar Archdeacon, who seized me, like the Ancient Mariner, and never let me go until he had impressed upon my mind the name and address of the only man in London who could cut clerical gaiters. But the simple child of sugar would have his way. There was but one Valhalla in London, and it was built by Decimus Burton.

After that we joined the ladies for an unimportant half hour or so, and then Barbara and I took our leave. As we were motoring home—we live some thirty miles out of London—we discussed the dinner party, according to the way of married folks, home-bound after a feast, and I mentioned the trivial incident of Adrian and the broken glass. Why should his face have been so haggard when he had everything to make him happy?

"He was thinking of Mr. Jornicroft's previous insulting behaviour."

"How do you know?"

"He told me," said Barbara.

"I never knew Adrian to be seriously vindictive," said I.

"It strikes me, my dear," replied Barbara, taking my hand, "that you are an old ignoramus."

And this from a woman who actively glories in not knowing how many "r's" there are in "harassed."

She nestled up to me. "We're not going abroad in August, are we?"

"What?" I cried, "leave the English country during the only part of the year that is not 'deformed with dripping rains or withered by a frost'? Certainly not."

"But we did last year, and the year before."

"Pure accident. The year before, Susan was recovering from the measles and you had some pretty frocks which you thought would look lovely at Dinard. And last year you also had some frocks and insisted that Houlgate was the only place where Susan could avoid being stricken down by scarlet-fever."

"Anyhow," said my wife, "we're not going away this year, for I've fixed up with Doria and Adrian to spend August at Northlands."

"Why didn't you tell me so at once? Why did you ask me whether we were going away?"

"Because I knew we weren't," she answered.

In putting two questions at the same time, I blundered. The first was a poser and might have elicited some interesting revelation of feminine mental process. In forlorn hope I repeated it.

"Why, I've told you, stupid," said Barbara. "You've no objection to their coming, have you?"

"Good Lord, no. I'm delighted."

"From the way you've argued, any one would have thought you didn't want them."

Outraged by the illogic, I gasped; but she broke into a laugh.

"You silly old Hilary," she said. "Don't you see that Doria must get her trousseau together and Adrian must find a house or a flat, that has to be decorated and furnished, and the poor child hasn't a mother or any sensible woman in the world to look after her but me?"

"I see," said I, "that you intend having the time of your life."

My prevision proved correct. In August came the engaged couple and every day Barbara took them up to town and whirled them about from house-agent to house-agent until she found a flat to suit them, and then from emporium to emporium until she found furniture to suit the flat, and from raiment-vendor to raiment-vendor until she equipped Doria to suit the furniture. She used to return almost speechless with exhaustion; but pantingly and with the glaze of victory in her eyes, she fought all her battles o'er again and told of bargains won. In the meantime had it not been for Susan, I should have lived in the solitude of an anchorite. We spent much time in the garden which we (she less conscious of irony than I) called our desert island. I was Robinson Crusoe and she was Man Friday, and on the whole we were quite happy; perhaps I should have been happier in a temperature of 80° in the shade if I had not been forced to wear the Polar bear rug from the drawing-room in representation of Crusoe's goatskins. I did suggest that I should be Robinson Crusoe's brother, who wore ordinary flannels, and that she should be Woman Wednesday. But Susan saw through the subterfuge and that game didn't work. One afternoon, however, Barbara, returning earlier than usual, caught us at it and expressing horror and indignation at the uses to which the bearskin was put, metaphorically whipped me and sent me to bed as being the elder of the naughty ones. After that we played at fairies in a glade, which was much cooler.

It was in the evenings that I was loneliest; for then Barbara went early to bed, and the lovers strolled about together in the moonlight. With the intention, half-malicious, half-pitiful, of filling up my time, Doria taught me a new and complicated Patience. Then finally, when Doria, having spent a couple of polite minutes in the drawing-room, had retired, and when I was tired out from the strain of the day and half-asleep through weariness, Adrian would mix himself the longest possible brandy and soda, light the longest possible cigar and try to keep me up all night listening to his conversation.

At last, one Friday evening, while I was engaged in my forlorn and unprofitable game, the butler entered the drawing-room with unperturbed announcement:

"Mr. Chayne on the telephone, sir."

I sent the card table flying amid the wreckage of my lay-out and rushed to the telephone.

"Hullo! That you, Jaff?"

"Yes, old man. Very much me. A devil of a lot of me. How are you?"

His strong bass boomed through the receiver. I have always found a queer comfort in Jaffery's voice. It wraps you round about in thundering waves. We exchanged the commonplaces of delighted greeting. I asked:

"When did you arrive?"

"A couple of days ago."

"Why on earth didn't you let me know at once?"

I heard him laugh. "I'll tell you when I see you. By the way, can Barbara have me for the week-end?"

This was like Jaffery. Most men would have asked me, taking Barbara for granted.

"Barbara would have you for the rest of time," said I. "And so would Susan. I'll expect you by the 11 o'clock train."

"Right," said he.

"And, I say!"

"Yes?"

"Talking of fair ladies—what about—?"

"Oh, Hell!" came Jaffery's great voice. "She's here right enough."

"Where?" I asked.

"The Savoy. So is Euphemia—"

Euphemia was Jaffery's unmarried sister, as like to her brother as a little wizened raisin is to a fat, bursting muscat grape.

"Euphemia has taken her on. Wants to convert her."

"Good Lord!" I cried. "Is she a Turk?"

"She's a problem." And his great laugh vibrated in my ears.

"Why not bring her down with Euphemia?"

"I want a couple of days off. I want a good quiet time, with no female women about save Barbara and my fairy grasshopper whom, as you know, I love to distraction."

"But will Euphemia be all right with her?"

I had not the faintest notion what kind of a creature the "problem" was.

"Right as rain. Euphemia has fixed up to take her to-morrow night to a lecture on Tolstoi at the Lyceum Club, and to the City Temple on Sunday. Ho! ho! ho!"

His Homeric laughter must have shattered the Trunk Telephone system of Great Britain, for after that there was silence cold and merciless. Well, perhaps it was just as well, for if we had been allowed to converse further I might have told him that another female woman, Doria Jornicroft, was staying at Northlands, and he might not have come. Jaffery was always a queer fish where women were concerned. Not a chilly, fishy fish, but a sort of Laodicean fish, now hot, now cold. I have seen him shrink like a sensitive plant in the presence of an ingenue of nineteen and royster in Pantagruelian fashion with a mature member of the chorus of the Paris Opera; I ham e also known him to fly, a scared Joseph, from the allurements of the charming wife of a Right Honourable Sir Cornifer Potiphar, G.C.M.G., and sigh like a furnace in front of an obdurate little milliner's place of business in Bond Street. I do not, for the world, wish it to be supposed that I am insinuating that my dear old Jaffery had no morals. He had—lots of them. He was stuffed with them. But what they were, neither he nor I nor any one else was ever able to define. As a general rule, however, he was shy of strange women, and to that category did Doria belong.

When the lovers came in I told them my news. Adrian expressed extravagant delight. A little tiny cloud flitted over Doria's brow.

"Shall I like him?" she asked.

"You'll adore him," cried Adrian.

"I'll try to, dear, because he seems to mean so much to you. Are you going up to town with us to-morrow?"

"There's only a morning's fitting at a dressmaker—no place for me," he laughed. "I'll stay and welcome old Jaffery."

Again the most transient of tiny little clouds. But I could not help thinking that if Jaffery had been a woman instead of a mere man, there would have been a thunderstorm.

When we were alone Adrian threw himself into a chair.

"Women are funny beings," he said. "I do believe Doria is jealous of old Jaffery."

"You have every reason to be proud," said I, "of your psychological acumen."

A fair-bearded, red-faced, blue-eyed, grinning giant got out of the train and catching sight of us ran up and laid a couple of great sun-glazed hands on my shoulders.

"Hullo! hullo! hullo!" he shouted, and gripping Adrian in his turn, shouted it again. He made such an uproar that people stuck wondering heads out of the carriage windows. Then he thrust himself between us, linked our arms in his and made us charge with him down the quiet country platform. A porter followed with his suit-case.

"Why didn't you tell me that the Man of Fame was with you?"

"I thought I'd give you a pleasant surprise," said I.

"I met Robson of the Embassy in Constantinople—you remember Robson of Pembroke—fussy little cock-sparrow—he'd just come from England and was full of it. You seem to have got 'em in the neck. Bully! Bully!"

Adrian took advantage of the narrow width of the exit to release himself and I, who went on with Jaffery, looking back, saw him rub himself ruefully, as though he had been mauled by a bear.

"And how's everybody?" Jaffery's voice reverberated through the subway. "Barbara and the fairy grasshopper? I'm longing to see 'em. That's the pull of being free. You can adopt other fellows' wives and families. I'm coming home now to my adopted wife and daughter. How are they?"

I answered explicitly. He boomed on till we reached the station yard, where his eye fell upon a familiar object.

"What?" cried he. "Have you still got the Chinese Puffhard?"

The vehicle thus disrespectfully alluded to was an ancient, ancient car, the pride of many a year ago, which sentiment (together with the impossibility of finding a purchaser) would not allow me to sell. It had been a splendid thing in those far-off days. It kept me in health. It made me walk miles and miles along unknown and unfrequented roads. In the aggregate I must have spent months of my life doing physical culture exercises underneath it. You got into it at the back; it was about ten feet high, and you started it at the side by a handle in its midriff. But I loved it. It still went, if treated kindly. Barbara loathed it and insulted it, so that with her as passenger, it sulked and refused to go. But Susan's adoration surpassed even mine. Its demoniac groans and rattles and convulsive quakings appealed to her unspoiled sense of adventure.

"Barbara has gone away with the Daimler," said I, "and as I don't keep a fleet of cars, I had to choose between this and the donkey-cart. Get in and don't be so fastidious—unless you're afraid—"

He took no account of my sarcasm. His face fell. He made no attempt to enter the car.

"Barbara gone away?"

I burst out laughing. His disappointment at not being welcomed by Barbara at Northlands was so genuine and so childishly unconcealed.

"She'll be back in time for lunch. She had to run up to town on business. She sent you her love and Susie will do the honours."

His face brightened. "That's all right. But you gave me a shock. Northlands without Barbara—" He shook his head.

We drove off. The Chinese Puffhard excelled herself, and though she choked asthmatically did not really stop once until we were half way up the drive, when I abandoned her to the gardeners, who later on harnessed the donkey to her and pulled her into the motor-house. We dismounted, however, in the drive. A tiny figure in a blue smock came scuttling over the sloping lawn. The next thing I saw was the small blue patch somewhere in the upland region of Jaffery's beard. Then boomed forth from him idiotic exclamations which are not worth chronicling, accompanied by a duet of bass and treble laughter. Then he set her astride of his bull neck and pitched his soft felt hat to Adrian to hold.

"Hang on to my hair. It won't hurt," he commanded.

She obeyed literally, clawing two handfuls of his thick reddish shock in her tiny grasp, and Jaffery lumbered along like an elephant with a robin on his head, unconscious of her weight. We mounted to the terrace in front of the house and having established my guests in easy chairs, I went indoors to order such drink as would be refreshing on a sultry August noon. When I returned I found Jaffery, with Susan on his knee, questioning Adrian, after the manner of a primitive savage, on the subject of "The Diamond Gate," and Adrian, delighted at the opportunity, dazzling our simple-minded friend with publisher's statistics.

"And you're writing another? Deep down in another?" asked Jaffery. "Do you know, Susie, Uncle Adrian has just got to take a pen and jab it into a piece of paper, and—tchick!—up comes a golden sovereign every time he does it."

Susan turned her serene gaze on Adrian. "Do it now," she commanded.

"I haven't got a pen," said he.

"I'll fetch you one from Daddy's study," she said, sliding from Jaffery's knee.

Both Jaffery and Adrian looked scared. I, who was not the father of a feminine thing of seven years old for nothing, interposed, I think, rather tactfully.

"Uncle Adrian can only do it with a great gold pen, and poor old daddy hasn't got one."

"I call that silly," replied my daughter. "Uncle Jaffery, have you got one?"

"No," said he, "You have to be born, like Uncle Adrian, with a golden pen in your mouth."

The lucky advent of the Archangel Gabriel, with a grin on his face and a doll in his mouth—the Archangel Gabriel, commonly known as Gabs, and so termed on account of his archi-angelic disposition, a hideous mongrel with a white patch over one eye and a brown patch over the other, with the nose of a collie and the legs of a Great Dane and the tail of a fox-terrier, whose mongreldom, however, Adrian repudiated by the bold assertion that he was a Zanzibar bloodhound—the lucky advent of this pampered and over-affectionate quadruped directed Susan's mind from the somewhat difficult conversation. She ran off, forthwith, to the rescue or her doll; but later (I heard) her nurse was sore put to it to explain the mystery of the golden pen.

"So much for Adrian. I'm tired of the auriferous person," said I, waving a hand. "What about yourself? What about the dynamic widow?"

"Oh, damn the dynamic widow," he replied, corrugating his serene and sunburnt forehead. "I've come down here to forget her. I'll tell you about her later." Then he grinned, in his silly, familiar way, showing two rows of astonishingly white, strong teeth, between the hair on lip and chin.

"Well," said I, "at any rate give some account of yourself. What were you doing in Albania, for instance?"

"Prospecting," said he.

"In what—gold, coal, iron?"

"War," said he. "There's going to be a hell of a bust-up one of these days—and one of these days very soon—in the Balkans. From Scutari to Salonica to Rodosto, the whole blooming triangle—it's going to be a battlefield. The war correspondent who goes out there not knowing his ground will be a silly ass. The slim statesman like me won't. See? So poor old Prescott—you must know Prescott of Reuter's?—anyhow that was the chap—poor old Prescott and I went out exploring. When he pegged out with enteric I hadn't finished, so I dumped his widow down at Cettinje where I have some pals, and started out again on my own. That's all."

He filled another pint tumbler with the iced liquid (one always had to provide largely for Jaffery's needs) and poured it down his throat.

"I don't call that a very picturesque account of your adventures," said Adrian.

Jaffery grinned. "I'll tell you all sorts of funny things, if you'll give me time," said he, wiping his lips with a vast red and white handkerchief about the size of a ship's Union Jack.

But we did not give him time; we plied him with questions and for the next hour he entertained us pleasantly with stories of his wanderings. He had a Rabelaisian way of laughing over must of his experiences, even those which had a touch of the gruesome, and the laughter got into his speech, so that many amusing episodes were told in the roars of a hilarious lion.

Presently the familiar sound of the horn announced the return of Barbara. We sprang to our feet and descended to meet the car at the front porch. Jaffery, grinning with delight, opened the door, appeared to lift a radiant Barbara out of the car like a parcel and almost hugged her. And there they stood holding on to each other's hands and smiling into each other's faces and saying how well they looked, regardless of the fact that they were blocking the way for Doria, who remained in the car, I had to move them on with the reminder that they had the whole week-end for their effusions. Adrian helped Doria to alight, and to Doria then, for the first time, was presented Jaffery Chayne. Jaffery blinked at her oddly as he held her little gloved fingers in his enormous hand. And, indeed, I could excuse him; for she was a very striking object to come suddenly into the immediate range of a man's vision, with her chiffon and her slenderness, and her black hat beneath which her great eyes shone from the startling, nervous, ivory-white face.

She smiled on him graciously. "I'm so glad to meet you." Then after a fraction of a second came the explanation. "I've heard so much of you."

He murmured something into his beard. Meeting his childlike gaze of admiration, she turned away and put her arm round Barbara's waist. The ladies went indoors to take off their things, accompanied by Adrian, who wanted a lover's word with Doria on the way. Jaffery followed her with his eyes until she had disappeared at the corner of the hall-stairs. Then he took me by the arm and led me up towards the terrace.

"Who is that singularly beautiful girl?" he asked.

"Doria Jornicroft," said I.

"She's the most astonishing thing I've ever seen in my life."

"I wouldn't find her too astonishing, if I were you," said I with a laugh, "because there might be complications. She's engaged to Adrian."

He dropped my arm. "Do you mean—she's going to marry him?"

"Next month," said I.

"Well, I'm damned," said Jaffery. I asked him why. He did not enlighten me. "Isn't he a lucky devil?" he asked, instead. "The most pestilentially lucky devil under the sun. But why the deuce didn't you tell me before?"

"You expressed such a distaste for female women that we thought we would give you as long a respite as possible."

"That's all very well," he grumbled. "But if I had known that Adrian's fiancée was knocking around I'd have lumped her in my heart with Barbara and Susie."

"You're not prevented from doing that now," said I.

His brow cleared. "True, sonny." He broke into a guffaw. "Fancy old Adrian getting married!"

"I see nothing funny in it," said I. "Lots of people get married. I'm married."

"Oh, you—you were born to be married," he said crushingly.

"And so are you," I retorted.

"I? I tie myself to the stay-strings of a flip of a thing in petticoats, whom I should have to swear to love, honour and obey—?"

"My good fellow," I interrupted, "it is the woman who swears obedience."

"And the man practises it. Ho! Ho! Ho!"

His laughter (at this very poor repartee) so resounded that the adventitious cow, in the field some hundred yards away, lifted her tail in the air and scampered away, in terror.

"And as to the stay-strings, to continue your delicate metaphor, you can always cut them when you like."

"Yes. And then there's the devil to pay. She shows you the ends and makes you believe they're dripping blood and tears. Don't I know 'em? They're the same from Cape Horn to Alaska, from Dublin to Rio."

He bellowed forth his invective. He had no quarrel with marriage as an institution. It was most useful and salutary—apparently because it provided him, Jaffery, with comfortable conditions wherein to exist. The multitude of harmless, necessary males (like myself) were doomed to it. But there was a race of Chosen Ones, to which he belonged, whose untamable and omni-concupiscent essence kept them outside the dull conjugal pale. For such as him, nineteen hundred women at once, scattered within the regions of the seven circumferential seas. He loved them all. Woman as woman was the joy of the earth. It was only the silly spectrum of civilisation that broke Woman up into primary colours—black, yellow, brunette, blonde—he damned civilisation.

"To listen to you," said I, when he paused for breath, "one would think you were a devil of a fellow."

"I am," he declared. "I'm a Universalist. At any rate in theory, or rather in the conviction of what best suits myself. I'm one of those men who are born to be free, who've got to fill their lungs with air, who must get out into the wilds if they're to live—God! I'd sooner be snowed up on a battlefield than smirk at a damned afternoon tea-party any day in the week! If I want a woman, I like to take her by her hair and swing her up behind me on the saddle and ride away with her—"

"Lord! That's lovely," said I. "How often have you done it?"

"I've never done that exactly, you silly ass," said he. "But that's my attitude, my philosophy. You see how impossible it would be for me to tie myself for life to the stay-strings of one flip of a thing in petticoats."

"You're a blessed innocent," said I.

Adrian sauntering through the French window of my library joined us on the terrace. Jaffery, forgetful of his attitude, his philosophy, caught him by the shoulders and shook him in pain-dealing exuberance. Old Adrian was going to be married. He wished him joy. Yet it was no use his wishing him joy because he already had it—it was assured. That exquisite wonder of a girl. Adrian was a lucky devil, a pestilentially lucky devil. He, Jaffery, had fallen in love with her on sight. . . .

"And if I hadn't told him that Miss Jornicroft was engaged to you," said I, "he would have taken her by the hair of her head and swung her up behind him on the saddle and ridden away with her. It's a little way Jaffery has."

In spite of sunburn, freckles and pervading hairiness of face, Jaffery grew red.

"Shut up, you silly fool!" said he, like the overgrown schoolboy that he was.

And I shut up—not because he commanded, but because Barbara, like spring in deep summer, and Doria, like night at noontide, appeared on the terrace.

Soon afterwards lunch was announced. By common conspiracy Jaffery and Susan upset the table arrangements, insisting that they should sit next each other. He helped the child to impossible viands, much to my wife's dismay, and told her apocalyptic stories of Bulgaria, somewhat to her puzzledom, but wholly to her delight. But when he proposed to fill her silver mug (which he, as godfather, had given her on her baptism) with the liquefied dream of Paradise that Barbara, sola mortalium, can prepare, consisting of hock and champagne and fruits and cucumber and borage and a blend of liqueurs whose subtlety transcends human thought, Barbara's Medusa glare petrified him into a living statue, the crystal jug of joy poised in his hand.

"Why mayn't I have some, mummy?"

"Because Uncle Jaff's your godfather," said I. "And your mother's hock-cup is a sinful lust of the flesh. Spare the child and fill up your own glass."

"Don't you know," said Barbara, "that this is Berkshire, not the Balkans? We don't intoxicate infants here to make a summer holiday!"

At this rebuke he exchanged winks with my daughter, and refusing a handed dish of cutlets asked to be allowed to help himself to some cold beef on the sideboard. The butler's assistance he declined. No Christian butler could carve for Jaffery Chayne. After a longish absence he returned to the table with half the joint on his plate. Susan regarded it wide-eyed.

"Uncle Jaff, are you going to eat all that?" she asked in an audible whisper.

"Yes, and you too," he roared, "and mummy and daddy and Uncle Adrian, if I don't get enough to eat!"

"And Aunt Doria?"

Again he reddened—but he turned to Doria and bowed.

"In my quality of ogre only—a bonne bouche," said he.

It was said very charmingly, and we laughed. Of course Susan began the inevitable question, but Barbara hurriedly notified some dereliction with regard to gravy, and my small daughter was, so to speak, hustled out of the conversation. Jaffery by way of apology for his Gargantuan appetite discoursed on the privations of travel in uncivilised lands. A lump of sour butter for lunch and a sardine and a hazelnut for dinner. We were to fancy the infinite accumulation of hunger-pangs. And as he devoured cold beef and talked, Doria watched him with the somewhat aloof interest of one who stands daintily outside the railed enclosure of a new kind of hippopotamus.

The meal over we sought the deep shade of the terrace which faces due east. Jaffery, in his barbaric fashion, took Doria by the elbow and swept her far away from the wistaria arbour beneath which the remaining three of us were gathered, and when he fondly thought he was out of earshot, he set her beside him on the low parapet. My wife, with the responsibilities of all the Chancelleries of Europe knitted in her brow, discussed wedding preparations with Adrian. I, to whom the quality of the bath towels wherewith Adrian and his wife were to dry themselves and that of the sheets between which their housemaid was to lie, were matters of black and awful indifference, gave my more worthily applied attention to one of a new brand of cigars, a corona corona, that had its merits but lacked an indefinable soul-satisfying aroma; and I was on the pleasurable and elusive point of critical formulation, when Jaffery's voice, booming down the terrace, knocked the discriminating nicety out of my head. I lazily shifted my position and watched the pair.

"You're subtle and psychological and introspective and analytic and all that," Jaffery was saying—his light word about an ogre at lunch was not a bad one; sitting side by side on the low parapet they looked like a vast red-bearded ogre and a feminine black-haired elf—she had taken off her hat—engaged in a conversation in which the elf looked very much on the defensive—"and you're always tracking down motives to their roots, and you're not contented, like me, with the jolly face of things—"

"For an accurate diagnosis," I reflected, "of an individual woman's nature, the blatant universalist has his points."

"Whereas, I, you see," he continued, "just buzz about life like a dunderheaded old bumble-bee. I'm always busting myself up against glass panes, not seeing, as you would, the open window a few inches off. Do you see what I'm driving at?"

Apparently she didn't; for while she was speaking, he threw away his corona corona—a dream of a cigar for nine hundred and ninety-nine men out of a thousand (I glanced at Adrian who had religiously preserved two inches of ash on his)—and hauled out pipe and tobacco-pouch. I could not hear what she said. When she had finished, he edged a span nearer.

"What I want you to understand," said he, "is that I'm a simple sort of savage. I can't follow all these intricate henry Jamesian complications of feeling. I've had in my life"—he stuck pouch and pipe on the stone beside him—"I've had in my life just a few men I've loved—I don't count women—men—men I've cared for, God knows why. Do you know why one cares for people?"

She smiled, shrugged her shoulders and shook her head.

"The latest was poor Prescott—he has just pegged out—you'll hear soon enough about Prescott. There was Tom Castleton—has Adrian told you about Castleton—?"

Again she shook her head.

"He will—of course—a wonder of a fellow—up with us at Cambridge. He's dead. There only remains Hilary, our host, and Adrian."

As far as I could gather—for she spoke in the ordinary tones of civilised womanhood, whereas Jaffery, under the impression that he was whispering confidentially, bellowed like an honest bull—as far as I could gather, she said:

"You must have met hundreds of men more sympathetic to you than Mr. Freeth and Adrian."

"I haven't," he cried. "That's the funny devil of it. I haven't. If I was struck a helpless paralytic with not a cent and no prospect of earning a cent, I know I could come to those two and say, 'Keep me for the rest of my life'—and they would do it"

"And would you do the same for either of them?"

Jaffery rose and stuffed his hands in his jacket pockets and towered over her.

"I'd do it for them and their wives and their children and their children's children."

He sat down again in confusion at having been led into hyperbole. But he took her shoulders in his huge but kindly hands, somewhat to her alarm—for, in her world, she was not accustomed to gigantic males laying unceremonious hold of her—

"All I wanted to convey to you, my dear girl, is this—that if Adrian's wife won't look on me as a true friend, I'm ready to go away and cut my throat"

Doria smiled at him with pretty civility and assured him of her willingness to admit him into her inner circle of friends; whereupon he caught up his pouch and pipe and lumbered down the terrace towards us, shouting out his news.

"I've fixed it up with Doria"—he turned his head—"I can call you Doria, can't I?" She nodded permission—what else could she do? "We're going to be friends. And I say, Barbara, they'll want a wedding-present. What shall I give 'em? What would you like?"

The latter question was levelled direct at Doria, who had followed demurely in his footsteps. But it was not answered; for from the drawing-room there emerged Franklin, the butler, who marched up straight to Jaffery.

"A lady to see you, sir"

"A lady? Good God! What kind of a lady?"

He stared at Franklin, in dismay.

"She came in a taxi, sir. The driver mistook the way, and put her down at the back entrance. She would not give her name."

"Tall, rather handsome, dressed in black?"

"Yes, sir."

"Lord Almighty!" cried Jaffery, including us all in the sweep of a desperate gaze. "It's Liosha! I thought I had given her the slip."

Barbara rose, and confronted him. "And pray who is Liosha?"

Adrian hugged his knee and laughed:

"The dynamic widow," said he.

"I'll go and see what in thunder she wants," said Jaffery.

But Barbara's eyes twinkled. "You'll do nothing of the sort. She has no business to come running after you like this. She must be taught manners. Franklin, will you show the lady out here?"

She drew herself up to her full height of five feet nothing, thereby demonstrating the obvious fact that she was mistress in her own house.

Presently Franklin reappeared.

"Mrs. Prescott," said he.

That there should have been in the uncommon-tall young woman of buxom stateliness and prepossessing features, attired (to the mere masculine eye) in quite elegant black raiment—a thing called, I think, a picture hat, broad-brimmed with a sweeping ostrich feather, tickled my especial fancy, but was afterwards reviled by my wife as being entirely unsuited to fresh widowhood—what there should have been in this remarkable Junoesque young person who followed on the heels of Franklin to strike terror into Jaffery's soul, I could not, for the life of me, imagine. In the light of her personality I thought Barbara's coup de théâtre rather cruel. . . . Of course Barbara received her courteously. She, too, was surprised at her outward aspect, having expected to behold a fantastic personage of comic opera.

"I am very pleased to see you, Mrs. Prescott."

Liosha—I must call her that from the start, for she exists to me as Liosha and as nothing else—shook hands with Barbara, making a queer deep formal bow, and turned her calm, brown eyes on Jaffery. There was just a little quarter-second of silence, during which we all wondered in what kind of outlandish tongue she would address him. To our gasping astonishment she said with an unmistakable American intonation: "Mr. Chayne, will you have the kindness to introduce me to your friends?"

I broke into a nervous laugh and grasped her hand "Pray allow me. I am Mr. Freeth, your much honoured host, and this is my wife, and . . . Miss Jornicroft . . . and Mr. Boldero. Mr. Chayne has been deceiving us. We thought you were an Albanian."

"I guess I am," said the lady, after having made four ceremonious bows, "I am the daughter of Albanian patriots. They were murdered. One day I'm going back to do a little murdering on my own account."

Barbara drew an audible short breath and Doria instinctively moved within the protective area of Adrian's arm. Jaffery, with knitted brow, leaned against one of the posts supporting the old wistaria arbour and said nothing, leaving me to exploit the lady.

"But you speak perfect English," said I.

"I was raised in Chicago. My parents were employed in the stockyards of Armour. My father was the man who slit the throats of the pigs. He was a dandy," she said in unemotional tones—and I noticed a little shiver of repulsion ripple through Barbara and Doria. "When I was twelve, my father kind of inherited lands in Albania, and we went back. Is there anything more you'd like to know?"

She looked us all up and down, rather down than up, for she towered above us, perfectly unconcerned mistress of the situation. Naturally we made mute appeal to Jaffery. He stirred his huge bulk from the post and plunged his hands into his pockets.

"I should like to know, Liosha," said he, in a rumble like thunder, "why you have left my sister Euphemia and what you are doing here?"

"Euphemia is a damn fool," she said serenely. "She's a freak. She ought to go round in a show."

"What have you been quarrelling about?" he asked.

"I never quarrel," she replied, regarding him with her calm brown eyes. "It is not dignified."

"Then I repeat, most politely, Liosha—what are you doing here?"

She looked at Barbara. "I guess it isn't right to talk of money before strangers."

Barbara smiled—glanced at me rebukingly. I pulled forward a chair and invited the lady to sit—for she had been standing and her astonishing entrance had flabbergasted ceremonious observance out of me. Whilst she was accepting my belated courtesy, Barbara continued to smile and said:

"You mustn't look on us as strangers, Mrs. Prescott. We are all Mr. Chayne's oldest and most intimate friends."

"Do tell us what the row was?" said Jaffery.

Liosha took calm stock of us, and seeing that we were a pleasant-faced and by no means an antagonistic assembly—even Doria's curiosity lent her a semblance of a sense of humour—she relaxed her Olympian serenity and laughed a little, shewing teeth young and strong and exquisitely white.

"I am here, Jaff Chayne," she said, "because Euphemia is a damn fool. She took me this morning to your big street—the one where all the shops are—"

"My dear lady," said Adrian, "there are about a hundred miles of such streets in London."

"There's only one—" she snapped her fingers, recalling the name—"only one Regent Street, I ever heard of," she replied crushingly. "It was Regent Street. Euphemia took me there to shew me the shops. She made me mad. For when I wanted to go in and buy things she dragged me away. If she didn't want me to buy things why did she shew me the shops?" She bent forward and laid her hand on Barbara's knee. "She must he a damn fool, don't you think so?"

Said Barbara, somewhat embarrassed:

"It's an amusement here to look at shops without any idea of buying."

"But if one wants to buy? If one has the money to buy?—I did not want anything foolish. I saw jewels that would buy up the whole of Albania. But I didn't want to buy up Albania. Not yet. But I saw a glass cage in a shop window full of little chickens, and I said to Euphemia: 'I want that. I must have those chickens.' I said, 'Give me money to go in and buy them.' Do you know, Jaff Chayne, she refused. I said, 'Give me my money, my husband's money, this minute, to buy those chickens in the glass cage.' She said she couldn't give me my husband's money to spend on chickens."

"That was very foolish of her," said Adrian solemnly, "for if there's one thing the management of the Savoy Hotel love, it's chicken incubators. They keep a specially heated suite of apartments for them."

"I was aware of it," said Liosha seriously. "Euphemia was not. She knows less than nothing. I asked her for the money. She refused. I saw an automobile close by. I entered. I said, 'Drive me to Mr. Jaff Chayne, he will give me the money.' He asked where Mr. Jaff Chayne was. I said he was staying with Mr. Freeth, at Northlands, Harston, Berkshire. I am not a fool like Euphemia. I remember. I left Euphemia standing on the sidewalk with her mouth open like that"—she made the funniest grimace in the world—"and the automobile brought me here to get some money to buy the chickens." She held out her hand to Jaffery.

"Confound the chickens," he cried. "It's the taxi I'm thinking of—ticking out tuppences, to say nothing of the mileage. Liosha," said he, in a milder roar, "it's no use thinking of buying chickens this afternoon. It's Saturday and the shops are shut. You go home before that automobile has ticked out bankruptcy and ruin. Go back to the Savoy and make your peace with Euphemia, like a good girl, and on Monday I'll talk to you about the chickens."

She sat up straight in her chair.

"You must take me somewhere else. I've got no use for Euphemia."

"But where else can I take you?" cried Jaffery aghast.

"I don't know. You know best where people go to in England. Doesn't he?" She included us all in a smile.

"But you must go back to Euphemia till Monday, at any rate."

"And she has arranged such a nice little programme for you," said Adrian. "A lecture on Tolstoi to-night and the City Temple to-morrow. Pity to miss 'em."

"If I saw any more of Euphemia, I might hurt her," said Liosha.

"Oh, Lord!" said Jaffery. "But you must go somewhere." He turned to me with a groan. "Look here, old chap. It's awfully rough luck, but I must take her back to the Savoy and mount guard over her so that she doesn't break my poor sister's neck."

"I wouldn't go so far as that," said Liosha.

"How far would you go?" Adrian asked politely, with the air of one seeking information.

"Oh, shut up, you idiot," Jaffery turned on him savagely. "Can't you see the position I'm in?"

"I'm very sorry you're angry, Jaff Chayne," said Liosha with a certain kind dignity. "But these are your friends. Their house is yours. Why should I not stay here with you?"

"Here? Good God!" cried Jaffery.

"Yes, why not?" said Barbara, who had set out to teach this lady manners.

"The very thing," said I.

Jaffery declared the idea to be nonsense. Barbara and I protested, growing warmer in our protestations as the argument continued. Nothing would give us such unimaginable pleasure as to entertain Mrs. Prescott. Liosha laid her hand on Jaffery's arm.

"But why shouldn't they have me? When a stranger asks for hospitality in Albania he is invited to walk right in and own the place. Is it refused in England?"

"Strangers don't ask," growled Jaffery.

"It would make life much more pleasant if they did," said Barbara, smiling. "Mrs. Prescott, this bear of a guardian or trustee or whatever he is of yours, makes a terrible noise—but he's quite harmless."

"I know that," said Liosha.

"He does what I tell him," the little lady continued, drawing herself up majestically beside Jaffery's great bulk. "He's going to stay here, and so will you, if you will so far honour us."

Liosha rose and bowed. "The honour is mine."

"Then will you come this way—I will shew you your room."

She motioned to Liosha to precede her through the French window of the drawing-room. Before disappearing Liosha bowed again. I caught up Barbara.

"My dear, what about clothes and things?"

"My dear," she said, "there's a telephone, there's a taxi, there's a maid, there's the Savoy hotel, and there's a train to bring back maid and clothes."

When Barbara takes command like this, the wise man effaces himself. She would run an Empire with far less fuss than most people devote to the running of a small sweet-stuff shop. I smiled and returned to the others. Jaffery was again filling his huge pipe.

"I'm awfully sorry, old man," he said gloomily.

Adrian burst out laughing "But she's immense, your widow! The most refreshing thing I've seen for many a day. The way she clears the place of the cobwebs of convention! She's great. Isn't she, Doria?"

"I can quite understand Mr. Chayne finding her an uncomfortable charge."

"Thank you," said Jaffery, with rather unnecessary vehemence. "I knew you would be sympathetic." He dropped into a chair by her side. "You can't tell what an awful thing it is to be responsible for another human being."

"Heaps of people manage to get through with it—every husband and wife—every mother and father."

"Yes; but not many poor chaps who are neither father nor husband are responsible for another fellow's grown-up widow."

Doria smiled. "You must find her another husband."

"That's a great idea. Will you help me? Before I knew of Adrian's great good fortune, I wrote to Hilary—ho! ho! ho! But we must find somebody else."