Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Volume 1, September 12, 1841

Author: Various

Release date: February 7, 2005 [eBook #14927]

Most recently updated: December 19, 2020

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/14927

Credits: Produced by Syamanta Saikia, Jon Ingram, Barbara Tozier and the PG

Online Distributed Proofreading Team

After the ceremony, the happy pair set off for Brighton.”

There is something peculiarly pleasing in the above paragraph. The imagination instantly conjures up an elegant yellow-bodied chariot, lined with pearl drab, and a sandwich basket. In one corner sits a fair and blushing creature partially arrayed in the garments of a bride, their spotless character diversified with some few articles of a darker hue, resembling, in fact, the liquid matrimony of port and sherry; her delicate hands have been denuded of their gloves, exhibiting to the world the glittering emblem of her endless hopes. In the other, a smiling piece of four-and-twenty humanity is reclining, gazing upon the beautiful treasure, which has that morning cost him about six pounds five shillings, in the shape of licence and fees. He too has deprived himself of the sunniest portions of his wardrobe, and has softened the glare of his white ducks, and the gloss of his blue coat, by the application of a drab waistcoat. But why indulge in speculative dreams when we have realities to detail!

Agamemnon Collumpsion Applebite and his beauteous Juliana Theresa (late Waddledot), for three days, experienced that—

“Love is heaven, and heaven is love.”

His imaginary dinner-party became a reality, and the delicate attentions which he paid to his invisible guest rendered his Juliana Theresa’s life—as she exquisitely expressed it—

“A something without a name, but to which nothing was wanting.”

But even honey will cloy; and that sweetest of all moons, the Apian one, would sometimes be better for a change. Juliana passed the greater portion of the day on the sofa, in the companionship of that aromatic author, Sir Edward; or sauntered (listlessly hanging on Collumpsion’s arm) up and down the Steine, or the no less diversified Chain-pier. Agamemnon felt that at home at least he ought to be happy, and, therefore, he hung his legs over the balcony and whistled or warbled (he had a remarkably fine D) Moore’s ballad of—

“Believe me, if all those endearing young charms;”

or took the silver out of the left-hand pocket of his trousers, and placed it in the right-hand receptacle of the same garment. Nevertheless, he was continually detecting himself yawning or dozing, as though “the idol of his existence” was a chimera, and not Mrs. Applebite.

The time at length arrived for their return to town, and, to judge from the pleasure depicted in the countenances of the happy pair, the contemplated intrusion of the world on their family circle was anything but disagreeable. Old John, under the able generalship of Mrs. Waddledot, had made every requisite preparation for their reception. Enamelled cards, superscribed with the names of Mr. and Mrs. Applebite, and united together with a silver cord tied in a true lover’s knot, had been duly enclosed in an envelope of lace-work, secured with a silver dove, flying away with a square piece of silver toast. In company with a very unsatisfactory bit of exceedingly rich cake, this glossy missive was despatched to the whole of the Applebite and Waddledot connexion, only excepting the eighteen daughters who Mrs. Waddledot had reason to believe would not return her visit.

The meeting of the young wife and the wife’s mother was touching in the extreme. They rushed into each other’s arms, and indulged in plentiful showers of “nature’s dew.”

“Welcome! welcome home, my dear Juliana!” exclaimed the doting mother. “It’s the first time, Mr. A., that she ever left me since she was 16, for so long a period. I have had all the beds aired, and all the chairs uncovered. She’ll be a treasure to you, Mr. A., for a more tractable creature was never vaccinated;” and here the mother overcame the orator, and she wept again.

“My dear mother,” said Agamemnon, “I have already had many reasons to be grateful for my happy fortune. Don’t you think she is browner than when we left town?”

“Much, much!” sobbed the mother; “but the change is for the better.”

“I’m glad you think so, for Aggy is of the same opinion,” lisped the beautiful ex-Waddledot. “Tell ma’ the pretty metaphor you indulged in yesterday, Aggy.”

“Why, I merely remarked,” replied Collumpsion, blushing, “that I was pleased to see the horticultural beauties of her cheek superseded by such an exquisite marine painting. It’s nothing of itself, but Juley’s foolish fondness called it witty.”

The arrival of the single sister of Mrs. Applebite, occasioned another rush of bodies and several gushes of tears; then titterings succeeded, and then a simultaneous burst of laughter, and a rapid exit. Agamemnon looked round that room which he had furnished in his bachelorhood. A thousand old associations sprung up in his mind, and a vague feeling of anticipated evil for a moment oppressed him. The bijouterie seemed to reproach him with unkindness for having placed a mistress over them, and the easy chair heaved as though with suppressed emotion, at the thought that its luxurious proportions had lost their charms. Collumpsion held a mental toss-up whether he repented of the change in his condition; and, as faithful historians, we are compelled to state that it was only the entrance, at that particular moment, of Juliana, that induced him to cry—woman.

On the following day the knocker of No. 24 disturbed all the other numerals in Pleasant-terrace; and Mr. and Mrs. A. bowed and curtsied until they were tired, in acknowledgment of their friends’ “wishes of joy,” and, as one unlucky old gentleman expressed himself, “many happy returns of the day.”

It was a matter of surprise to many of the said friends, that so great an alteration as was perceptible in the happy pair, should have occurred in such a very short space of time.

“I used to think Mr. Applebite a very nice young man,” said Miss—mind, Miss Scragbury—“but, dear me, how he’s altered.”

“And Mrs. Applebite used to be a pretty girl,” rejoined her brother Julius; “but now (Juliana had refused him three times)—but now she’s as ill-looking as her mother.”

“I’d no idea this house was so small,” said Mrs. Scragmore. “I’m afraid the Waddledots haven’t made so great a catch, after all. I hope poor Juley will be happy, for I nursed her when a baby, but I never saw such an ugly pattern for a stair-carpet in my born days;” and with these favourable impressions of their dear friends the Applebites, the Scragmores descended the steps of No. 24, Pleasant-terrace, and then ascended those of No. 5436 hackney-coach.

About ten months after their union, Collumpsion was observed to have a more jaunty step and smiling countenance, which—as his matrimonial felicity had been so frequently pronounced perfect—puzzled his friends amazingly. Indeed, some were led to conjecture, that his love for Juliana Theresa was not of the positive character that he asserted it to be; for when any inquiries were made after her health, his answer had invariably been, of late, “Why, Mrs. A.—is—not very well;” and a smile would play about his mouth, as though he had a delightful vision of a widower-hood. The mystery was at length solved, by the exhibition of sundry articles of a Lilliputian wardrobe, followed by an announcement in the Morning Post, under the head of

“BIRTHS.—Yesterday morning, the lady of Agamemnon Collumpsion Applebite, Esq., of a son and heir.”

Pleasant-terrace was strawed from one end to the other; the knocker of 24 was encased in white kid, a doctor’s boy was observed to call three times a-day, and a pot-boy twice as often.

Collumpsion was in a seventh heaven of wedded bliss. He shook hands with everybody—thanked everybody—invited everybody when Mrs. A. should be better, and noted down in his pocket-book what everybody prescribed as infallible remedies for the measles, hooping-cough, small-pox, and rashes (both nettle and tooth)—listened for hours to the praises of vaccination and Indian-rubber rings—pronounced Goding’s porter a real blessing to mothers, and inquired the price of boys’ suits and rocking-horses!

In this state of paternal felicity we must leave him till our next.

It is rumoured that Macready is desirous of disposing of his “manners” previous to becoming manager, when he will have no further occasion for them. They are in excellent condition, having been very little used, and would be a desirable purchase for any one expecting to move within the sphere of his management.

A point impossible for mind to reach—

To find the meaning of a royal speech.

The late Queen of the Sandwich Islands, and the first convert to Christianity in that country, was called Keopalani, which means—“the dropping of the clouds from Heaven.”

This name’s the best that could be given,

As will by proof be quickly seen;

For, “dropping from the clouds of Heaven,”

She was, of course, the raining Queen.

Our gallant friend Sibthorp backed himself on the 1st of September to bag a hundred leverets in the course of the day. He lost, of course; and upon being questioned as to his reason for making so preposterous a bet, he confessed that he had been induced to do so by the specious promise of an advertisement, in which somebody professed to have discovered “a powder for the removal of superfluous hairs.”

Chaos returns! no soul’s in town!

And darkness reigns where lamps once brightened;

Shutters are closed, and blinds drawn down—

Untrodden door-steps go unwhitened!

The echoes of some straggler’s boots

Alone are on the pavement ringing

While ’prentice boys, who smoke cheroots,

Stand critics to some broom-girl’s singing.

I went to call on Madame Sims,

In a dark street, not far from Drury;

An Irish crone half-oped the door.

Whose head might represent a fury.

“At home, sir?” “No! (whisper)—but I’ll presume

To tell the truth, or know the raison.

She dines—tays—lives—in the back room,

Bekase ’tis not the London saison.”

From thence I went to Lady Bloom’s,

Where, after sundry rings and knocking,

A yawning, liveried lad appear’d,

His squalid face his gay clothes mocking

I asked him, in a faltering tone—

The house was closed—I guess’d the reason—

“Is Lady B.’s grand-aunt, then, gone?”—

“To Ramsgate, sir!—until next season!”

I sauntered on to Harry Gray’s,

The ennui of my heart to lighten;

His landlady, with, smirk and smile,

Said, “he had just run down to Brighton.”

When home I turned my steps, at last,

A tailor—whom to kick were treason—

Pressed for his bill;—I hurried past,

Politely saying—CALL NEXT SEASON!

We concluded our last article with a brief dissertation on the cut of the trousers; we will now proceed to the consideration of coats.

“The hour must come when such things must be made.”

For this quotation we are indebted to

There are three kinds of coats—the body, the surtout, and the great.

The body-coat is again divided into classes, according to their application, viz.—the drawing-room, the ride, and the field.

The cut of the dress-coat is of paramount importance, that being the garment which decorates the gentleman at a time when he is naturally ambitious of going the entire D’Orsay. There is great nicety required in cutting this article of dress, so that it may at one and the same moment display the figure and waistcoat of the wearer to the utmost advantage. None but a John o’Groat’s goth would allow it to be imagined that the buttons and button-holes of this robe were ever intended to be anything but opposite neighbours, for a contrary conviction would imply the absence of a cloak in the hall or a cab at the door. We do not intend to give a Schneiderian dissertation upon garments; we merely wish to trace outlines; but to those who are anxious for a more intimate acquaintance with the intricacies and mysteries of the delightful and civilising art of cutting, we can only say, Vide Stultz.11. Should any gentleman avail himself of this hint, we should feel obliged if he would mention the source from whence it was derived, having a small account standing in that quarter, for tailors have gratitude.

The riding-coat is the connecting link between the DRESS and the rest of the great family of coats, as one button, and one only of this garment, may be allowed to be applied to his apparent use.

It is so cut, that the waistcoat pockets may be easy of access. Any gentleman who has attended races or other sporting meetings must have found the convenience of this arrangement; for where the course is well managed, as at Epsom, Ascot, Hampton, &c., by the judicious regulations of the stewards, the fingers are generally employed in the distribution of those miniature argentine medallions of her Majesty so particularly admired by ostlers, correct card-vendors, E.O. table-keepers, Mr. Jerry, and the toll-takers on the road and the course. The original idea of these coats was accidentally given by John Day, who was describing, on Nugee’s cutting-board, the exact curvature of Tattenham Corner.

The shooting-jacket should be designed after a dovecot or a chest of drawers; and the great art in rendering this garment perfect, is to make the coat entirely of pockets, that part which covers the shoulders being only excepted, from the difficulty of carrying even a cigar-case in that peculiar situation.

The surtout (not regulation) admits of very little design. It can only be varied by the length of the skirts, which may be either as long as a fireman’s, or as short as Duvernay’s petticoats. This coat is, in fact, a cross between the dress and the driving, and may, perhaps, be described as a Benjamin junior.

Of the Benjamin senior, there are several kinds—the Taglioni, the Pea, the Monkey, the Box, et sui generis.

The three first are all of the coal-sackian cut, being, in fact, elegant elongated pillow-cases, with two diminutive bolsters, which are to be filled with arms instead of feathers. They are singularly adapted for concealing the fall in the back, and displaying to the greatest advantage those unassuming castors designated “Jerrys,” which have so successfully rivalled those silky impostors known to the world as

The box-coat has, of late years, been denuded of its layers of capes, and is now cut for the sole purpose, apparently, of supporting perpendicular rows of wooden platters or mother-of-pearl counters, each of which would be nearly large enough for the top of a lady’s work-table. Mackintosh-coats have, in some measure, superseded the box-coat; but, like carters’ smock-frocks, they are all the creations of speculative minds, having the great advantage of keeping out the water, whilst they assist you in becoming saturated with perspiration. We strongly suspect their acquaintance with India-rubber; they seem to us to be a preparation of English rheumatism, having rather more of the catarrh than caoutchouc in their composition. Everybody knows the affinity of India-rubber to black-lead; but when made into a Mackintosh, you may substitute the lum for the plumbago.

We never see a fellow in a seal-skin cap, and one of these waterproof pudding-bags, but we fancy he would make an excellent model for

The ornaments and pathology will next command our attention.

A friend insulted us the other day with the following:—“Billy Black supposes Sam Rogers wears a tightly-laced boddice. Why is it like one of Milton’s heroes?” Seeing we gave it up, he replied—“Because Sam’s-on-agony-stays.”—(Samson Agonistes.)

This morning, at an early hour, we were thrown into the greatest consternation by a column of boys, who poured in upon us from the northern entrance, and, taking up their-station near the pump, we expected the worst.

8 o’clock.—The worst has not yet happened. An inhabitant has entered the square-garden, and planted himself at the back of the statue; but everything is in STATUE QUO.

5 minutes past 8.—The boys are still there. The square-keeper is nowhere to be found.

10 minutes past 8.—The insurgents have, some of them, mounted on the fire-escape. The square-keeper has been seen. He is sneaking round the corner, and resolutely refuses to come nearer.

¼ past 8.—A deputation has waited on the square-keeper. It is expected that he will resign.

20 minutes past 8.—The square-keeper refuses to resign.

22 minutes past 8.—The square-keeper has resigned.

25 minutes past 8.—The boys have gone home.

½ past 8.—The square-keeper has been restored, and is showing great courage and activity. It is not thought necessary to place him under arms; but he is under the engine, which can he brought into play at a moment’s notice. His activity is surprising, and his resolution quite undaunted.

9 o’clock.—All is perfectly quiet, and the letters are being delivered by the general post-man as usual. The inhabitants appear to be going to their business, as if nothing had happened. The square-keeper, with the whole of his staff (a constable’s staff), may be seen walking quietly up and down. The revolution is at an end; and, thanks to the fire-engine, our old constitution is still preserved to us.

My dear Friend.—You are aware how long I have been longing to go up in a balloon, and that I should certainly have some time ago ascended with Mr. Green, had not his terms been not simply a cut above me, but several gashes beyond my power to comply with them. In a word, I did not go up with the Nassau, because I could not come down with the dust, and though I always had “Green in my eye,” I was not quite so soft as to pay twenty pounds in hard cash for the fun of going, on

nobody knows where, and coming down Heaven knows how, in a field belonging to the Lord knows who, and being detained for goodness knows what, for damage.

Not being inclined, therefore, for a nice and expensive voyage with Mr. Green, I made a cheap and nasty arrangement with Mr. Hampton, the gentleman who courageously offers to descend in a parachute—a thing very like a parasol—and who, as he never mounts much above the height of ordinary palings, might keep his word without the smallest risk of any personal inconvenience.

It was arranged and publicly announced that the balloon, carrying its owner and myself, should start from the Tea-gardens of the Mitre and Mustard Pot, at six o’clock in the evening; and the public were to be admitted at one, to see the process of inflation, it being shrewdly calculated by the proprietor, that, as the balloon got full, the stomachs of the lookers on would be getting empty, and that the refreshments would go off while the tedious work of filling a silken bag with gas was going on, so that the appetites and the curiosity of the public would be at the same time satisfied.

The process of inflation seemed to have but little effect on the balloon, and it was not until about five o’clock that the important discovery was made, that the gas introduced at the bottom had been escaping through a hole in the top, and that the Equitable Company was laying it on excessively thick through the windpipes of the assembled company.

Six o’clock arrived, and, according to contract, the supply of gas was cut off, when the balloon, that had hitherto worn such an appearance as just to give a hope that it might in time be full, began to present an aspect which induced a general fear that it must very shortly be empty. The audience began to be impatient for the promised ascent, and while the aeronaut was running about in all directions looking for the hole, and wondering how he should stop it up, I was requested by the proprietor of the gardens to step into the car, just to check the growing impatience of the audience. I was received with that unanimous shout of cheering and laughter with which a British audience always welcomes any one who appears to have got into an awkward predicament, and I sat for a few minutes, quietly expecting to be buried in the silk of the balloon, which was beginning to collapse with the greatest rapidity. The spectators becoming impatient for the promised ascent, and seeing that it could not be achieved, determined, as enlightened British audiences invariably do, that if it was not to be done, it should at all events be attempted. In vain did Mr. Hampton come forward to apologise for the trifling accident; he was met by yells, hoots, hisses, and orange-peel, and the benches were just about to be torn up, when he declared, that under any circumstances, he was determined to go up—an arrangement in which I was refusing to coincide—when, just as he had got into the car, all means of getting out were withdrawn from under us—the ropes were cut, and the ascent commenced in earnest.

The majestic machine rose slowly to the height of about eight feet, amid the most enthusiastic cheers, when it rolled over among some trees, amid the most frantic laughter. Mr. Hampton, with singular presence of mind, threw out every ounce of ballast, which caused the balloon to ascend a few feet higher, when a tremendous gust of easterly wind took us triumphantly out of the gardens, the palings of which we cleared with considerable nicety. The scene at this moment was magnificent; the silken monster, in a state of flabbiness, rolling and fluttering above, while below us were thousands of spectators, absolutely shrieking with merriment. Another gust of wind carried us rapidly forward, and, bringing us exactly in a level with a coach-stand, we literally swept, with the bottom of our car, every driver from off his box, and, of course, the enthusiasm of a British audience almost reached its climax. We now encountered the gable-end of a station-house, and the balloon being by this time thoroughly collapsed, our aerial trip was brought to an abrupt conclusion. I know nothing more of what occurred, having been carried on a shutter, in a state of

to my own lodging, while my companion was left to fight it out with the mob, who were so anxious to possess themselves of some memento of the occasion, that the balloon was torn to ribbons, and a fragment of it carried away by almost every one of the vast multitude which had assembled to honour him with their patronage.

I have the honour to be, yours, &c.

A. SPOONEY.

A country gentleman informs us that he was horror-stricken at the sight of an apparently organised band, wearing fustian coats, decorated with curious brass badges, bearing exceedingly high numbers, who perched themselves behind the Paddington omnibuses, and, in the most barefaced and treasonable manner, urged the surrounding populace to open acts of daring violence, and wholesale arson, by shouting out, at the top of their voices, “O burn, the City, and the Bank.”

“We have lordlings in dozens,” the Tories exclaim,

“To fill every place from the throng;

Although the cursed Whigs, be it told to our shame,

Kept us poor lords in waiting too long.”

The Honourable Sambo Sutton begs us to state, that he is not the Honourable —— Sutton who is announced as the Secretary for the Home Department. He might have been induced to have stepped into Lord Cottenham’s shoes, on his

Feargus O’Connor passed his word last week at the London Tavern.

At the late collision between the Beacon brig and the Topaz steamer, one of the passengers, anticipating the sinking of both vessels, and being strongly embued with the great principle of self-preservation, immediately secured himself the assistance of the anchor! Did he conceive “Hope” to have been unsexed, or that that attribute originally existed as a “floating boy?”

“The Loves of Giles Scroggins and Molly Brown:” an Epic Poem. London: CATNACH.

The great essentials necessary for the true conformation of the sublimest effort of poetic genius, the construction of an “Epic Poem,” are numerically three; viz., a beginning, a middle, and an end. The incipient characters necessary to the beginning, ripening in the middle, and, like the drinkers of small beer and October leaves, falling in the end.

The poem being thus divided into its several stages, the judgment of the writer should emulate that of the experienced Jehu, who so proportions his work, that all and several of his required teams do their own share and no more—fifteen miles (or lengths) to a first canto, and five to a second, is as far from right as such a distribution of mile-stones would be to the overworked prads. The great fault of modern poetasters arises from their extreme love of spinning out an infinite deal of nothing. Now, as “brevity is the soul of wit,” their productions can be looked upon as little else than phantasmagorial skeletons, ridiculous from their extreme extenuation, and in appearance more peculiarly empty, from the circumstance of their owing their existence to false lights. This fault does not exist with all the master spirits, and, though “many a flower is born to blush unseen,” we now proceed to rescue from obscurity the brightest gem of unfamed literature.

Wisdom is said to be found in the mouths of babes and sucklings. So is the epic poem of Giles Scroggins. Is wisdom Scroggins, or is Scroggins wisdom? We can prove either position, but we are cramped for space, and therefore leave the question open. Now for our author and his first line—

“Giles Scroggins courted Molly Brown.”

Beautiful condensation! Is or is not this rushing at once in medias res? It is; there’s no paltry subterfuge about it—no unnecessary wearing out of “the waning moon they met by”—“the stars that gazed upon their joy”—“the whispering gales that breathed in zephyr’s softest sighs”—their “lover’s perjuries to the distracted trees they wouldn’t allow to go to sleep.” In short, “there’s no nonsense”—there’s a broad assertion of a thrilling fact—

“Giles Scroggins courted Molly Brown.”

So might a thousand folks; therefore (the reader may say) how does this establish the individuality of Giles Scroggins, or give an insight to the character of the chosen hero of the poem? Mark the next line, and your doubts must vanish. He courted her; but why? Ay, why? for the best of all possible reasons—condensed in the smallest of all possible space, and yet establishing his perfect taste, unequalled judgment, and peculiarly-heroic self-esteem—he courted her because she was

“The fairest maid in all the town.”

Magnificent climax! overwhelming reason! Could volumes written, printed, or stereotyped, say more? Certainly not; the condensation of “Aurora’s blushes,” “the Graces’ attributes,” “Venus’s perfections,” and “Love’s sweet votaries,” all, all is more than spoken in the emphatic words—

“The fairest maid in all the town.”

Nothing can go beyond this; it proves her beauty and her disinterestedness. The fairest maid might have chosen, nay, commanded, even a city dignitary. Does the so? No; Giles Scroggins, famous only in name, loves her, and—beautiful poetic contrivance!—we are left to imagine he does “not love unloved.” Why should she reciprocate? inquires the reader. Are not truth and generosity the princely paragons of manly virtue, greater, because unostentatious? and these perfect attributes are part and parcel of great Giles. He makes no speeches—soils no satin paper—vows no vows—no, he is above such humbug. His motto is evidently deeds, not words. And what does he do? Send a flimsy epistle, which his fair reader pays the vile postage for? Not he; he

“Gave a ring with posy true!”

Think of this. Not only does he “give a ring,” but he annihilates the suppositionary fiction in which poets are supposed to revel, and the ring’s accompaniment, though the child of a creative brain—the burning emanation from some Apollo-stricken votary of “the lying nine,” imbued with all his stern morality, is strictly “true.” This startling fact is not left wrapped in mystery. The veriest sceptic cannot, in imagination, grave a fancied double meaning on that richest gift. No—the motto follows, and seems to say—Now, as the champion of Giles Scroggins, hurl I this gauntlet down; let him that dare, uplift it! Here I am—

“If you loves I, as I loves you!”

Pray mark the syncretic force of the above line. Giles, in expressing his affection, felt the singular too small, and the vast plural quick supplied the void—Loves must be more than love.

“If you loves I, as I loves you,

No knife shall cut our loves in two!”

This is really sublime! “No knife!” Can anything exceed the assertion? Nothing but the rejoinder—a rejoinder in which the talented author not only stands proudly forward as a poet, but patriotically proves the amor propriæ, which has induced him to study the staple manufactures of his beloved country! What but a diligent investigation of the cutlerian process could have prompted the illustration of practical knowledge of the Birmingham and Sheffield artificers contained in the following exquisitely explanatory line. But—pray mark the but—

“But scissors cut as well as knives!”

Sublime announcement! startling information! leading us, by degrees, to the highest of all earthly contemplations, exalting us to fate and her peculiar shears, and preparing us for the exquisitely poetical sequel contained in the following line:—

“And so unsartain’s all our lives.”

Can anything exceed this? The uncertainty of life evidently superinduced the conviction of all other uncertainties, and the sublime poet bears out the intenseness of his impressions by the uncertainty of his spelling! Now, reader, mark the next line, and its context:—

“The very night they were to wed!”

Fancy this: the full blossoming of all their budding joys, anticipations, death, and hope’s accomplishment, the crowning hour of their youth’s great bliss, “the very night they were to wed,” is, with extra syncretic skill, chosen as the awful one in which

“Fate’s scissors cut Giles Scroggins’ thread!”

Now, reader, do you see the subtle use of practical knowledge? Are you convinced of the impotent prescription from knives only? Can you not perceive in “Fate’s scissors” a parallel for the unthought-of host “that bore the mighty wood of Dunsinane against the blood-stained murderer of the pious Duncan?” Does not the fatal truth rush, like an unseen draught into rheumatic crannies, slick through your soul’s perception? Are you not prepared for this—to be resumed in our next?

Lord Lyndhurst is to have the seals; but it is not yet decided who is to be entrusted with the wafer-stamps. Gold-stick has not been appointed, and there are so many of the Conservatives whose qualities peculiarly fit them for the office of stick, that the choice will be exceedingly embarrassing.

Though the Duke of Wellington does not take office, an extra chair has been ordered, to allow of his having a seat in the Cabinet. And though Lord Melbourne is no longer minister, he is still to be indulged with a lounge on the sofa.

If the Duke of Beaufort is to be Master of the Horse, it is probable that a new office will be made, to allow Colonel Sibthorp to take office as Comptroller of the Donkeys: and it is said that Horace Twiss is to join the administration as Clerk of the Kitchen.

It was remarked, that after Sir Robert Peel had kissed hands, the Queen called for soap and water, for the purpose of washing them.

The Duchess of Buccleugh having refused the office of Mistress of the Robes, it will not be necessary to make the contemplated new appointment of Keeper of the Flannel Petticoats.

The Grooms of the Bedchamber are, for the future, to be styled Postilions of the Dressing-room; because, as the Sovereign is a lady, instead of a gentleman, it is thought that the latter title, for the officers alluded to, will be more in accordance with propriety. For the same excellent reason, it is expected that the Knights of the Bath will henceforth be designated the Chevaliers of the Foot-pan.

Prince Albert’s household is to be entirely re-modelled, and one or two new offices are to be added, the want of which has hitherto occasioned his Royal Highness much inconvenience. Of these, we are only authorised in alluding, at present, to Tooth-brush in Ordinary, and Shaving-pot in Waiting. There is no foundation for the report that there is to be a Lord High Clothes-brush, or Privy Boot-jack.

The following letter has been addressed to us by a certain party, who, as our readers will perceive, has been one of the sufferers by the late clearance made in a fashionable establishment at the West-end:—

DEAR PUNCH.—As you may not be awair of the mallancoly change wich as okkurred to the pore sarvunts here, I hassen to let you no—that every sole on us as lost our plaices, and are turnd owt—wich is a dredful klamity, seeing as we was all very comfittible and appy as we was. I must say, in gustis to our Missus, that she was very fond of us, and wouldn’t have parted with one of us if she had her will: but she’s only a O in her own howse, and is never aloud to do as she licks. We got warning reglar enuff, but we still thort that somethink might turn up in our fever. However, when the day cum that we was to go, it fell upon us like a thunderboat. You can’t imagine the kunfewshion we was all threw into—every body packing up their little afares, and rummidging about for any trifele that wasn’t worth leaving behind. The sarvunts as is cum in upon us is a nice sett; they have been a long wile trying after our places, and at last they have suckseeded in underminding us; but it’s my oppinion they’ll never be able to get through the work of the house;—all they cares for is the vails and purkussites. I forgot to menshun that they hadn’t the decency to wait till we was off the peremasses, wich I bleave is the etticat in sich cases, but rushed in on last Friday, and tuck possession of all our plaices before we had left the concirn. I leave you to judge by this what a hurry they was to get in. There’s one comfurt, however, that is—we’ve left things in sich a mess in the howse, that I don’t think they’ll ever be able to set them to rites again. This is all at present from your afflickted friend,

JOHN THE FOOTMAN.

“I declare I never knew a flatter companion than yourself,” said Tom of Finsbury, the other evening, to the lion of Lambeth. “Thank you, Tom,” replied the latter; “but all the world knows that you’re a flatter-er.” Tom, in nautical phrase, swore, if he ever came athwart his Hawes, that he would return the compliment with interest.

—“Here, methinks,

Truth wants no ornament.”—ROGERS.

We have the happiness to know a gentleman of the name of Tom, who officiates in the capacity of ostler. We have enjoyed a long acquaintance with him—we mean an acquaintance a long way off—i.e. from the window of our dormitory, which overlooks A—s—n’s stables. We believe we are the first of our family, for some years, who has not kept a horse; and we derive a melancholy gratification in gazing for hours, from our lonely height, at the zoological possessions of more favoured mortals.

“The horse is a noble animal,” as a gentleman once wittily observed, when he found himself, for the first time in his life, in a position to make love; and we beg leave to repeat the remark—“the horse is a noble animal,” whether we consider him in his usefulness or in his beauty; whether caparisoned in the chamfrein and demi-peake of the chivalry of olden times, or scarcely fettered and surmounted by the snaffle and hog-skin of the present; whether he excites our envy when bounding over the sandy deserts of Arabia, or awakens our sympathies when drawing sand from Hampstead and the parts adjacent; whether we see him as romance pictures him, foaming in the lists, or bearing, “through flood and field,” the brave, the beautiful, and the benighted; or, as we know him in reality, the companion of our pleasures, the slave of our necessities, the dislocator of our necks, or one of the performers at our funeral; whether—but we are not drawing a “bill in Chancery.”

With such impressions in favour of the horse, we have ever felt a deep anxiety about those to whom his conduct and comfort are confided.

The breeder—we envy.

The breaker—we pity.

The owner—we esteem.

The groom—we respect.

AND

The ostler—we pay.

Do not suppose that we wish to cast a slur upon the latter personage, but it is too much to require that he who keeps a caravansera should look upon every wayfarer as a brother. It is thus with the ostler: his feelings are never allowed to twine

“Around one object, till he feels his heart

Of its sweet being form a deathless part.”

No—to rub them down, give them a quartern and three pen’orth, and not too much water, are all that he has to connect him with the offspring of Childers, Eclipse, or Pot-8-o’s; ergo, we pay him.

My friend Tom is a fine specimen of the genus. He is about fifteen hands high, rising thirty, herring-bowelled, small head, large ears, close mane, broad chest, and legs à la parentheses ( ). His dress is a long brown-holland jacket, covering the protuberance known in Bavaria by the name of pudo, and in England by that of bustle. His breeches are of cord about an inch in width, and of such capacious dimensions, that a truss of hay, or a quarter of oats, might be stowed away in them with perfect convenience: not that we mean to insinuate they are ever thus employed, for when we have seen them, they have been in a collapsed state, hanging (like the skin of an elephant) in graceful festoons about the mid-person of the wearer. These necessaries are confined at the knee by a transverse row of pearl buttons crossing the genu patella. The pars pendula is about twelve inches wide, and supplies, during conversation or rumination, a resting-place for the thumbs or little fingers. His legs are encased either in white ribbed cotton stockings, or that peculiar kind of gaiter ’yclept kicksies. His feet know only one pattern shoe, the ancle-jack (or highlow as it is sometimes called), resplendent with “Day and Martin,” or the no less brilliant “Warren.” Genius of propriety, we have described his tail before that index of the mind, that idol of phrenologists, his pimple!—we beg pardon, we mean his head. Round, and rosy as a pippin, it stands alone in its native loveliness, on the heap of clothes beneath.

Tom is not a low man; he has not a particle of costermongerism in his composition, though his discourse savours of that peculiar slang that might be considered rather objectionable in the salons of the élite.

The bell which he has the honour to answer hangs at the gate of a west-end livery-stables, and his consequence is proportionate. To none under the degree of a groom does he condescend a nod of recognition—with a second coachman he drinks porter—and purl (a compound of beer and blue ruin) with the more respectable individual who occupies the hammer-cloth on court-days. Tom estimates a man according to his horse, and his civility is regulated according to his estimation. He pockets a gratuity with as much ease as a state pensioner; but if some unhappy wight should, in the plenitude of his ignorance, proffer a sixpence, Tom buttons his pockets with a smile, and politely “begs to leave it till it becomes more.”

With an old meerschaum and a pint of tolerable sherry, we seat ourselves at our window, and hold many an imaginative conversation with our friend Tom. Sometimes we are blest with more than ideality; but that is only when he unbends and becomes jocular and noisy, or chooses a snug corner opposite our window to enjoy his otium—confound that phrase!—we would say his indolence and swagger—

“A pound to a hay-seed agin’ the bay.”

Hallo! that’s Tom! Yes—there he comes laughing out of “Box 4,” with three others—all first coachmen. One is making some very significant motions to the potboy at the “Ram and Radish,” and, lo! Ganymede appears with a foaming tankard of ale. Tom has taken his seat on an inverted pail, and the others are grouped easily, if not classically, around him.

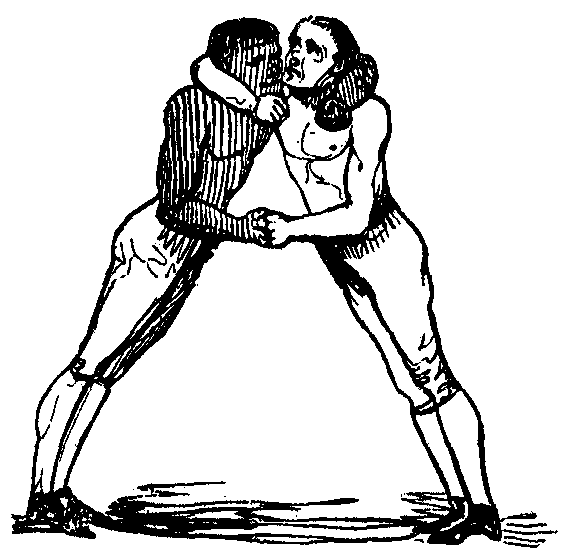

One is resting his head between the prongs of a stable-fork; another is spread out like the Colossus of Rhodes; whilst a gentleman in a blue uniform has thrown himself into an attitude à la Cribb, with the facetious intention of “letting daylight into the wittling department” of the pot-boy of the “Ram and Radish.”

Tom has blown the froth from the tankard, and (as he elegantly designates it) “bit his name in the pot.” A second has “looked at the maker’s name;” and another has taken one of those positive draughts which evince a settled conviction that it is a last chance.

Our friend has thrust his hands into the deepest depths of his breeches-pocket, and cocking one eye at the afore-named blue uniform, asks—

“Will you back the bay?”

The inquiry has been made in such a do-if-you-dare tone, that to hesitate would evince a cowardice unworthy of the first coachman to the first peer in Belgrave-square, and a leg of mutton and trimmings are duly entered in a greasy pocket-book, as dependent upon the result of the Derby.

“The son of Tros, fair Ganymede,” is again called into requisition, and the party are getting, as Tom says, “As happy as Harry Stockracy.”

“I’ve often heerd that chap mentioned,” remarks the blue uniform, “but I never seed no one as know’d him.”

“No more did I,” replies Tom, “though he must be a fellow such as us, up to everything.”

All the coachmen cough, strike an attitude, and look wise.

“Now here comes a sort of chap I despises,” remarks Tom, pointing to a steady-looking man, without encumbrance, who had just entered the yard, evidently a coachman to a pious family; “see him handle a hoss. Smear—smear—like bees-waxing a table. Nothing varminty about him—nothing of this sort of thing (spreading himself out to the gaze of his admiring auditory), but I suppose he’s useful with slow cattle, and that’s a consolation to us as can’t abear them.” And with this negative compliment Tom has broken up his conversazione.

I once knew a country ostler—by name Peter Staggs—he was a lower species of the same genus—a sort of compound of my friend Tom and a waggoner—the delf of the profession. He was a character in his way; he knew the exact moment of every coach’s transit on his line of road, and the birth, parentage, and education of every cab, hack, and draught-horse in the neighbourhood. He had heard of a mane-comb, but had never seen one; he considered a shilling for a “feed” perfectly apocryphal, as he had never received one. He kept a rough terrier-dog, that would kill anything in the country, and exhibited three rows of putrified rats, nailed at the back of the stable, as evidences of the prowess of his dog. He swore long country oaths, for which he will be unaccountable, as not even an angel could transcribe them. In short, he was a little “varminty,” but very little.

We will conclude this “lytle historie” with the epitaph of poor Peter Staggs, which we copied from a rail in Swaffham churchyard.

“EPITAPH ON PETER STAGGS.

Poor Peter Staggs now rests beneath this rail,

Who loved his joke, his pipe, and mug of ale;

For twenty years he did the duties well,

Of ostler, boots, and waiter at the ‘Bell.’

But Death stepp’d in, and order’d Peter Staggs

To feed his worms, and leave the farmers’ nags.

The church clock struck one—alas! ’twas Peter’s knell,

Who sigh’d, ‘I’m coming—that’s the ostler’s bell!’”

Peace to his manes!

“If you won’t turn, I will,” as the mill-wheel said to the stream.

“Why did not Wellington take a post in the new Cabinet?” asked Dicky Sheil of O’Connell.—“Bathershin!” replied the head of the tail, “the Duke is too old a soldier to lean on a rotten stick.”

Lord Morpeth intends proceeding to Canada immediately. The object of his journey is purely scientific; he wishes to ascertain if the Fall of Niagara be really greater than the fall of the Whigs.

“When is Peel not Peel?”—“When he’s candi(e)d.”

We have heard of the very dead being endowed, by galvanic action, with the temporary powers of life, and on such occasions the extreme force of the apparatus has ever received the highest praise. The Syncretic march of mind rectifies the above error—with them, weakness is strength. Fancy the alliterative littleness of a “Stephens” and a “Selby,” as the tools from which the drama must receive its glorious resuscitation!

Bedlam, the celebrated receptacle for lunatics, is situated in St. George’s-fields, within five minutes’ walk of the King’s Bench. There is also another noble establishment in the neighbourhood of Finsbury-square, where the unhappy victims of extraordinary delusions are treated with the care and consideration their several hallucinations require.

At length, PEEL is called in “in a regular way.” Being assured of his quarterly fee, the state physician may now, in the magnanimity of his soul, prescribe new life for moribund John Bull. Whether he has resolved within himself to emulate the generous dealing of kindred professors—of those sanative philosophers, whose benevolence, stamped in modest handbills, “crieth out in the street,” exclaiming “No cure no pay,”—we know not; certain we are, that such is not the old Tory practice. On the contrary, the healing, with Tory doctors, has ever been in an inverse ratio to the reward. Like the faculty at large, the Tories have flourished on the sickness of the patient. They have, with Falstaff, “turned diseases to commodity;” their only concern being to keep out the undertaker. Whilst there’s life, there’s profit,—is the philosophy of the Tory College; hence, poor Mr. Bull, though shrunk, attenuated,—with a blister on his head, and cataplasms at his soles,—has been kept just alive enough to pay. And then his patience under Tory treatment—the obedience of his swallow! “Admirable, excellent!” cried a certain doctor (we will not swear that his name was not PEEL), when his patient pointed to a dozen empty phials. “Taken them all, eh? Delightful! My dear sir, you are worthy to be ill.” JOHN BULL having again called in the Tories, is “worthy to be ill;” and very ill he will be.

The tenacity of life displayed by BULL is paralleled by a case quoted by LE VAILLANT. That naturalist speaks of a turtle that continued to live after its brain was taken from its skull, and the cavity stuffed with cotton. Is not England, with spinning-jenny PEEL at the head of its affairs, in this precise predicament? England may live; but inactive, torpid; unfitted for all healthful exertion,—deprived of its grandest functions—paralyzed in its noblest strength. We have a Tory Cabinet, but where is the brain of statesmanship?

Now, however, there are no Tories. Oh, no! Sir ROBERT PEEL is a Conservative—LYNDHURST is a Conservative—all are Conservative. Toryism has sloughed its old skin, and rejoices in a new coat of many colours; but the sting remains—the venom is the same; the reptile that would have struck to the heart the freedom of Europe, elaborates the self-same poison, is endowed with the same subtilty, the same grovelling, tortuous action. It still creeps upon its belly, and wriggles to its purpose. When adders shall become eels, then will we believe that Conservatives cannot be Tories.

When folks change their names—unless by the gracious permission of the Gazette—they rarely do so to avoid the fame of brilliant deeds. It is not the act of an over-sensitive modesty that induces Peter Wiggins to dub himself John Smith. Be certain of it, Peter has not saved half a boarding-school from the tremendous fire that entirely destroyed “Ringworm House”—Peter has not dived into the Thames, and rescued some respectable attorney from a death hitherto deemed by his friends impossible to him. It is from no such heroism that Peter Wiggins is compelled to take refuge in John Smith from the oppressive admiration of the world about him. Certainly not. Depend upon it, Peter has been signalised in the Hue and Cry, as one endowed with a love for the silver spoons of other men—as an individual who, abusing the hospitality of his lodgings, has conveyed away and sold the best goose feathers of his landlady. What then, with his name ripe enough to drop from the tree of life, remains to Wiggins, but to subside into Smith? What hope was there for the well-known swindler, the posted pickpocket, the callous-hearted, slug-brained Tory? None: he was hooted, pelted at; all men stopped the nose at his approach. He was voted a nuisance, and turned forth into the world, with all his vices, like ulcers, upon him. Well, Tory adopts the inevitable policy of Wiggins; he changes his name! He comes forth, curled and sweetened, and with a smile upon his mealy face, and placing his felon hand above the vacuum on the left side of his bosom—declares, whilst the tears he weeps would make a crocodile blush—that he is by no means the Tory his wicked, heartless enemies would call him. Certainly not. His name is—Conservative! There was, once, to be sure, a Tory—in existence;

“But he is dead, and nailed in his chest!”

He is a creature extinct, gone with the wolves annihilated by the Saxon monarch. There may be the skeleton of the animal in some rare collections in the kingdom; but for the living creature, you shall as soon find a phoenix building in the trees of Windsor Park, as a Tory kissing hands in Windsor Castle!

The lie is but gulped as a truth, and Conservative is taken into service. Once more, he is the factotum to JOHN BULL. But when the knave shall have worn out his second name—when he shall again be turned away—look to your feather-beds, oh, JOHN! and foolish, credulous, leathern-eared Mr. BULL—be sure and count your spoons!

Can it be supposed that the loss of office, that the ten years’ hunger for the loaves and fishes endured by the Tory party, has disciplined them into a wiser humanity? Can it be believed that they have arrived at a more comprehensive grasp of intellect—that they are ennobled by a loftier consideration of the social rights of man—that they are gifted with a more stirring sympathy for the wants that, in the present iniquitous system of society, reduce him to little less than pining idiotcy, or madden him to what the statutes call crime, and what judges, sleek as their ermine, preach upon as rebellion to the government—the government that, in fact, having stung starvation into treason, takes to itself the loftiest praise for refusing the hangman—a task—for appeasing Justice with simple transportation?

Already the Tories have declared themselves. In the flush of anticipated success, PEEL at the Tamworth election denounced the French Revolution that escorted Charles the Tenth—with his foolish head still upon his shoulders—out of France, as the “triumph of might over right.” It was the right—the divine right of Charles—(the sacred ampoule, yet dropping with the heavenly oil brought by the mystic dove for Clovis, had bestowed the privilege)—to gag the mouth of man; to scourge a nation with decrees, begot by bigot tyranny upon folly—to reduce a people into uncomplaining slavery. Such was his right: and the burst of indignation, the irresistible assertion of the native dignity of man, that shivered the throne of Charles like glass, was a felonious might—a rebellious, treasonous potency—the very wickedness of strength. Such is the opinion of Conservative PEEL! Such the old Tory faith of the child of Toryism!

Since the Tamworth speech—since the scourging of Sir ROBERT by the French press—PEEL has essayed a small philanthropic oration. He has endeavoured to paint—and certainly in the most delicate water-colours—the horrors of war. The premier makes his speech to the nations with the palm-branch in his hand—with the olive around his brow. He has applied arithmetic to war, and finds it expensive. He would therefore induce France to disarm, that by reductions at home he may not be compelled to risk what would certainly jerk him out of the premiership—the imposition of new taxes. He may then keep his Corn Laws—he may then securely enjoy his sliding scale. Such are the hopes that dictate the intimation to disarm. It is sweet to prevent war; and, oh! far sweeter still to keep out the Wigs!

The Duke of WELLINGTON, who is to be the moral force of the Tory Cabinet, is a great soldier; and by the very greatness of his martial fame, has been enabled to carry certain political questions which, proposed by a lesser genius, had been scouted by the party otherwise irresistibly compelled to admit them. (Imagine, for instance, the Marquis of Londonderry handling Catholic Emancipation.) Nevertheless, should “The follies of the Wise”—a chronicle much wanted—be ever collected for the world, his Grace of Wellington will certainly shine as a conspicuous contributor. In the name of famine, what could have induced his Grace to insult the misery at this moment, eating the hearts of thousands of Englishmen? For, within these few days, the Victor of Waterloo expressed his conviction that England was the only country in which “the poor man, if only sober and industrious, WAS QUITE CERTAIN of acquiring a competency!” And it is this man, imbued with this opinion, who is to be hailed as the presiding wisdom—the great moral strength—the healing humanity of the Tory Cabinet. If rags and starvation put up their prayer to the present Ministry, what must be the answer delivered by the Duke of Wellington? “YE ARE DRUNKEN AND LAZY!”

If on the night of the 24th of August—the memorable night on which this heartless insult was thrown in the idle teeth of famishing thousands—the ghosts of the victims of the Corn Laws,—the spectres of the wretches who had been ground out of life by the infamy of Tory taxation, could have been permitted to lift the bed-curtains of Apsley-House,—his Grace the Duke of Wellington would have been scared by even a greater majority than ultimately awaits his fellowship in the present Cabinet. Still we can only visit upon the Duke the censure of ignorance. “He knows not what he says.” If it be his belief that England suffers only because she is drunken and idle, he knows no more of England than the Icelander in his sledge: if, on the other hand, he used the libel as a party warfare, he is still one of the “old set,”—and his “crowning carnage, Waterloo,” with all its greatness, is but a poor set-off against the more lasting iniquities which he would visit upon his fellow-men. Anyhow, he cannot—he must not—escape from his opinion; we will nail him to it, as we would nail a weasel to a barn-door; “if Englishmen want competence, they must be drunken—they must be idle.” Gentlemen Tories, shuffle the cards as you will, the Duke of Wellington either lacks principle or brains.

Next week we will speak of the Whigs; of the good they have done—of the good they have, with an instinct towards aristocracy—most foolishly, most traitorously, missed.

Q.

Who Kill’d Cock Russell?

I, said Bob Peel,

The political eel,

I kill’d Cock Russell.

Who saw him die?

We, said the nation,

At each polling station,

We saw him die.

Who caught his place?

I, for I can lie,

Said turn-about Stanley,

I caught his place.

Who’ll make his shroud?

We, cried the poor

From each Union door,

We’ll make his shroud.

Who’ll dig his grave?

Cried the corn-laws, The fool

Has long been our tool,

We’ll dig his grave.

Who’ll be the parson?

I, London’s bishop,

A sermon will dish up,

I’ll be the parson.

Who’ll be the clerk?

Sibthorp, for a lark,

If you’ll all keep it dark,

He’ll be the clerk.

Who’ll carry him to his grave?

The Chartists, with pleasure,

Will wait on his leisure,

They’ll carry him to his grave.

Who’ll carry the link?

Said Wakley, in a minute,

I must be in it,

I’ll carry the link.

Who’ll be chief mourners?

We, shouted dozens

Of out-of-place cousins,

We’ll be chief mourners.

Who’ll bear the pall?

As they loudly bewail,

Both O’Connell and tail,

They’ll bear the pall.

Who’ll go before?

I, said old Cupid,

I’ll still head the stupid,

I’ll go before.

Who’ll sing a psalm?

I, Colonel Perceval,

(Oh, Peel, be merciful!)

I’ll sing a psalm.

Who’ll throw in the dirt?

I, said the Times,

In lampoons and rhymes,

I’ll throw in the dirt.

Who’ll toll the bell?

I, said John Bull,

With pleasure I’ll pull,—

I’ll toll the bell.

All the Whigs in the world

Fell a sighing and sobbing,

When wicked Bob Peel

Put an end to their jobbing.

Collected and elaborated expressly for “PUNCH,” by Tiddledy Winks, Esq., Hon. Sec., and Editor of the Peckham Evening Post and Camberwell-Green Advertiser.

Previously to placing the results of my unwearied application before the public, I think it will be both interesting and appropriate to trace, in a few words, the origin of this admirable society, by whose indefatigable exertions the air-pump has become necessary to the domestic economy of every peasant’s cottage; and the Budelight and beer-shops, optics and out-door relief, and Daguerrotypes and dirt, have become subjects with which they are equally familiar.

About the close of last year, a few scientific labourers were in the habit of meeting at a “Jerry” in their neighbourhood, for the purpose of discussing such matters as the comprehensive and plainly-written reports of the British Association, as furnished by the Athenæum, offered to their notice, in any way connected with philosophy or the belles lettres. The numbers increasing, it was proposed that they should meet weekly at one another’s cottages, and there deliver a lecture on any scientific subject; and the preliminary matters being arranged, the first discourse was given “On the Advantage of an Air-gun over a Fowling-piece, in bringing Pheasants down without making a noise.” This was so eminently successful, that the following discourses were delivered in quick succession:—

On the Toxicological Powers of Coculus Indicus in Stupifying Fish.

On the Combustion of Park-palings and loose Gate-posts.

On the tendency of Out-of-door Spray-piles to Spontaneous Evaporation, during dark nights.

On the Comparative Inflammatory properties of Lucifer Matches, Phosphorus Bottles, Tinder-boxes, and Congreves, as well as Incandescens Short Pipes, applied to Hay in particular and Ricks in general.

On the value of Cheap Literature, and Intrinsic Worth (by weight) of the various Publications of the Society for the Confusion of Useless Knowledge.

The lectures were all admirably illustrated, and the society appeared to be in a prosperous state. At length the government selected two or three of its most active members, and despatched them on a voyage of discovery to a distant part of the globe. The institution now drooped for a while, until some friends of education firmly impressed with the importance of their undertaking, once more revived its former greatness, at the same time entirely reorganizing its arrangements. Subscriptions were collected, sufficient to erect a handsome turf edifice, with a massy thatched roof, upon Timber Common; a committee was appointed to manage the scientific department, at a liberal salary, including the room to sit in, turf, and rushlights, with the addition, on committee nights, of a pint of intermediate beer, a pipe, and a screw, to each member. Gentlemen fond of hearing their own voices were invited to give gratuitous discourses from sister institutions: a museum and library were added to the building already mentioned, and an annual meeting of illuminati was agreed upon.

Amongst the papers contributed to be read at the evening meetings of the society, perhaps the most interesting was that communicated by Mr. Octavius Spiff, being a startling and probing investigation as to whether Sir Isaac Newton had his hat on when the apple tumbled on his head, what sort of an apple it most probably was, and whether it actually fell from the tree upon him, or, being found too hard and sour to eat, had been pitched over his garden wall by the hand of an irritated little boy. I ought also to make mention of Mr. Plummycram’s “Narrative of an Ascent to the summit of Highgate-hill,” with Mr. Mulltour’s “Handbook for Travellers from the Bank to Lisson-grove,” and “A Summer’s-day on Kennington-common.” Mr. Tinhunt has also announced an attractive work, to be called “Hackney: its Manufactures, Economy, and Political Resources.”

It is the intention of the society, should its funds increase, to take a high place next year in the scientific transactions of the country. Led by the spirit of enterprise now so universally prevalent, arrangements are pending with Mr. Purdy, to fit up two punts for the Shepperton expedition, which will set out in the course of the ensuing summer. The subject for the Prize Essay for the Victoria Penny Coronation Medal this year is, “The possibility of totally obliterating the black stamp on the post-office Queen’s heads, so as to render them serviceable a second time;” and, in imitation of the learned investigations of sister institutions, the Copper Jinks Medal will also be given to the author of the best essay upon “The existing analogy between the mental subdivision of invisible agencies and circulating decompositions.”—(To be continued.)

“Be still, my mighty soul! These ribs of mine

Are all too fragile for thy narrow cage.

By heaven! I will unlock my bosom’s door.

And blow thee forth upon the boundless tide

Of thought’s creation, where thy eagle wing

May soar from this dull terrene mass away,

To yonder empyrean vault—like rocket (sky)—

To mingle with thy cognate essences

Of Love and Immortality, until

Thou burstest with thine own intensity,

And scatterest into millions of bright stars,

Each one a part of that refulgent whole

Which once was ME.”

Thus spoke, or thought—for, in a metaphysical point of view, it does not much matter whether the passage above quoted was uttered, or only conceived—by the sublime philosopher and author of the tragedy of “Martinuzzi,” now being nightly played at the English Opera House, with unbounded success, to overflowing audiences22. Has this paragraph been paid for as an advertisement?—PRINTER’S DEVIL.—Undoubtedly.—ED.. These were the aspirations of his gigantic mind, as he sat, on last Monday morning, like a simple mortal, in a striped-cotton dressing-gown and drab slippers, over a cup of weak coffee. (We love to be minute on great subjects.) The door opened, and a female figure—not the Tragic muse—but Sally, the maid of-all-work, entered, holding in a corner of her dingy apron, between her delicate finger and thumb, a piece of not too snowy paper, folded into an exact parallelogram.

“A letter for you, sir,” said the maid of-all-work, dropping a reverential curtsey.

George Stephens, Esq. took the despatch in his inspired fingers, broke the seal, and read as follows:—

Surrey Theatre.

SIR,—I have seen your tragedy of “Martinuzzi,” and pronounce it magnificent! I have had, for some time, an idea in my head (how it came there I don’t know), to produce, after the Boulogne affair, a grand Inauguration of the Statue of Shakspere, on the stage of the Surrey, but not having an image of him amongst our properties, I could not put my plan into execution. Now, sir, as it appears that you are the exact ditto of the bard, I shouldn’t mind making an arrangement with you to undertake the character of our friend Billy on the occasion. I shall do the liberal in the way of terms, and get up the gag properly, with laurels and other greens, of which I have a large stock on hand; so that with your popularity the thing will be sure to draw. If you consent to come, I’ll post you in six-feet letters against every dead wall in town.

Yours,

WILLIS JONES.

When the author of the “magnificent poem” had finished reading the letter he appeared deeply moved, and the maid of-all-work saw three plump tears roll down his manly cheek, and rest upon his shirt collar. “I expected nothing less,” said he, stroking his chin with a mysterious air. “The manager of the Surrey, at least, understands me—he appreciates the immensity of my genius. I will accept his offer, and show the world—great Shakspere’s rival in myself.”

Having thus spoken, the immortal dramatist wiped his hands on the tail of his dressing-gown, and performed a pas seul “as the act directs,” after which he dressed himself, and emerged into the open air.

The sun was shining brilliantly, and Phoebus remarked, with evident pleasure, that his brother had bestowed considerable pains in adorning his person. His boots shone with unparalleled splendour, and his waistcoat—

[We omit the remainder of the inventory of the great poet’s wardrobe, and proceed at once to the ceremony of the Inauguration at the Surrey Theatre.]

Never on any former occasion had public curiosity over the water been so strongly excited. Long before the doors of the theatre were opened, several passengers in the street were observed to pause before the building, and regard it with looks of profound awe. At half-past six, two young sweeps and a sand-boy were seen waiting anxiously at the gallery entrance, determined to secure front seats at any personal sacrifice. At seven precisely the doors were opened, and a tremendous rush of four persons was made to the pit; the boxes had been previously occupied by the “Dramatic Council” and the “Syncretic Society.” The silence which pervaded the house, until the musicians began to tune their violins in the orchestra, was thrilling; and during the performance of the overture, expectation stood on tip-toe, awaiting the great event of the night.

At length the curtain slowly rose, and we discovered the author of “Martinuzzi” elevated on a pedestal formed of the cask used by the celebrated German tub-runner (a delicate compliment, by the way, to the genius of the poet). On this appropriate foundation stood the great man, with his august head enveloped in a capacious bread-bag. At a given signal, a vast quantity of crackers were let off, the envious bag was withdrawn, and the illustrious dramatist was revealed to the enraptured spectators, in the statuesque resemblance of his elder, but not more celebrated brother, WILLIAM SHAKSPERE. At this moment the plaudits were vigorously enthusiastic. Thrice did the flattered statue bow its head, and once it laid its hand upon its grateful bosom, in acknowledgment of the honour that was paid it. As soon as the applause had partially subsided, the manager, in the character of Midas, surrounded by the nine Muses, advanced to the foot of the pedestal, and, to use the language of the reporters of public dinners, “in a neat and appropriate speech,” deposed a laurel crown upon the brows of Shakspere’s effigy. Thereupon loud cheers rent the air, and the statue, deeply affected, extended its right hand gracefully towards the audience. In a moment the thunders of applause sank into hushed and listening awe, while the author of the “magnificent poem” addressed the house as follows:—

“My friends,—You at length behold me in the position to which my immense talents have raised me, in despite of ‘those laws which press so fatally on dramatic genius,’ and blight the budding hopes of aspiring authors.”

This commencement softened the hearts of his auditors, who clapped their handkerchiefs to their noses.

“The world,” continued the statue, “may regard me with envy; but I despise the world, particularly the critics who have dared to laugh at me. (Groans.) The object of my ambition is attained—I am now the equal and representative of Shakspere—detraction cannot wither the laurels that shadow my brows—Finis coronat opus!—I have done. To-morrow I retire into private life; but though fortune has made me great, she has not made me proud, and I shall be always happy to shake hands with a friend when I meet him.”

At the conclusion of this pathetic address, loud cheers, mingled with tears and sighs, arose from the audience, one-half of whom sunk into the arms of the other half, and were borne out of the house in a fainting state; and thus terminated this imposing ceremony, which will be long remembered with delight by every lover of

Mr. Levy, of Holywell-street, perceiving that his neighbour JACOB FAITHFUL’S farce, entitled “The Cloak and Bonnet,” has not given general satisfaction, begs respectfully to offer to the notice of the committee, his large and carefully-assorted stock of second-hand wearing apparel, from which he will undertake to supply any number of dramas that may be required, at a moment’s notice.

Mr. L. has at present on hand the following dramatic pieces, which he can strongly recommend to the public:—

“The Dressing Gown and Slippers.”—A fashionable comedy, suited for a genteel neighbourhood.

“The Breeches and Gaiters.”—A domestic drama. A misfit at the Adelphi.

“The Wig and Wig-box.”—A broad farce, made to fit little Keeley or anybody else.

“The Smock-frock and Highlows.”—A tragedy in humble life, with a terrific dénouement.

*∗* The above will be found to be manufactured out of the best materials, and well worthy the attention of those gentlemen who have so nobly come forward to rescue the stage from its present degraded position.

The scarcity of money is frightful. As much as a hundred per cent., to be paid in advance, has been asked upon bills; but we have not yet heard of any one having given it. There was an immense run for gold, but no one got any, and the whole of the transactions of the day were done in copper. An influential party created some sensation by coming into the market late in the afternoon, just before the close of business, with half-a-crown; but it was found, on inquiry, to be a bad one. It is expected that if the dearth of money continues another week, buttons must be resorted to. A party, whose transactions are known to be large, succeeded in settling his account with the Bulls, by means of postage-stamps; an arrangement of which the Bears will probably take advantage.

A large capitalist in the course of the day attempted to change the direction things had taken, by throwing an immense quantity of paper into the market; but as no one seemed disposed to have anything to do with it, it blew over.

The parties to the Dutch Loan are much irritated at being asked to take their dividends in butter; but, after the insane attempt to get rid of the Spanish arrears by cigars, which, it is well known, ended in smoke, we do not think the Dutch project will be proceeded with.

The “mysterious and melodramatic silence” which Mr. C. Mathews promised to observe as to his intentions in regard to the present season, has at length been broken. On Monday last, September the sixth, Covent Garden Theatre opened to admit a most brilliant audience. Amongst the company we noticed Madame Vestris, Mr. Oxberry, Mr. Harley, Miss Rainsforth, and several other distingué artistes. It would seem, from the substitution of Mr. Oxberry for Mr. Keeley, that the former gentleman is engaged to take the place of the latter. Whispers are afloat that, in consequence, one of the most important scenes in the play is to be omitted. Though of little interest to the audience, it was of the highest importance to the gentleman whose task it has hitherto been to perform the parts of Quince, Bottom, and Flute.

We, who are conversant with all the mysteries of the flats’ side of the green curtain, beg to assure our readers, that the Punch scene hath taken wing, and that the dressing-room of the above-named characters will no longer be redolent of the fumes of compounded bowls. We may here remark that, had our hint of last season been attended to, the Punch would have still been continued:—Mr. Harley would not consent to have the flies picked out of the sugar. Rumour is busy with the suggestion that for this reason, and this only, Keeley seceded from the establishment.

We think it exceedingly unwise in the management not to have secured the services of Madame Corsiret for the millinery department. Mr. Wilson still supplies the wigs. We have not as yet been able to ascertain to whom the swords have been consigned. Mr. Emden’s assistant superintends the blue-fire and thunder, but it has not transpired who works the traps.

With such powerful auxiliaries, we can promise Mr. C. Mathews a prosperous season.

Quoth Will, “On that young servant-maid

My heart its life-string stakes.”

“Quite safe!” cries Dick, “don’t be afraid—

She pays for all she breaks.”

The iniquities of the Tories having become proverbial, the House of Lords, with that consideration for the welfare of the country, and care for the morals of the people, which have ever characterised the compeers of the Lord Coventry, have brought in a bill for the creation of two Vice-Chancellors. Brougham foolishly proposed an amendment, considering one to be sufficient, but found himself in a singular minority when the House

In the Egyptian room of the British Museum is a statue of the deity IBIS, between two mummies. This attracted the attention of Sibthorp, as he lounged through the room the other day with a companion. “Why,” said his friend, “is that statue placed between the other two?” “To preserve it to be sure,” replied the keenly-witted Sib. “You know the old saying teaches us, ‘In medio tutissimus Ibis.’”

Mercy on us, what a code of morality—what a conglomeration of plots (political, social, and domestic)—what an exemplar of vice punished and virtue rewarded—is the “Newgate Calendar!” and Newgate itself! what tales might it not relate, if its stones could speak, had its fetters the gift of tongues!

But these need not be so gifted: the proprietor of the Victoria Theatre supplies the deficiency: the dramatic edition of Old-Bailey experience he is bringing out on each successive Monday, will soon be complete; and when it is, juvenile Jack Sheppards and incipient Turpins may complete their education at the moderate charge of sixpence per week. The “intellectualization of the people” must not be neglected: the gallery of the Victoria invites to its instructive benches the young, whose wicked parents have neglected their education—the ignorant, who know nothing of the science of highway robbery, or the more delicate operations of picking pockets. National education is the sole aim of the sole lessee—money is no object; but errand-boys and apprentices must take their Monday night’s lessons, even if they rob the till. By this means an endless chain of subjects will be woven, of which the Victoria itself supplies the links; the “Newgate Calendar” will never be exhausted, and the cause of morality and melodrama continue to run a triumphant career!

The leaf of the “Newgate Calendar” torn out last Monday for the delectation and instruction of the Victoria audience, was the “Life and Death of James Dawson,” a gentleman rebel, who was very properly hanged in 1746.

The arrangement of incidents in this piece was evidently an appeal to the ingenuity of the audience—our own penetration failed, however, in unravelling the plot. There was a drunken, gaming, dissipated student of St. John’s, Cambridge—a friend in a slouched hat and an immense pair of jack-boots, and a lady who delicately invites her lover (the hero) “to a private interview and a cold collation.” There is something about a five-hundred-pound note and a gambling-table—a heavy throw of the dice, and a heavier speech on the vices of gaming, by a likeness of the portrait of Dr. Dilworth that adorns the spelling-books. The hero rushes off in a state of distraction, and is followed by the jack-boots in pursuit; the enormous strides of which leave the pursued but little chance, though he has got a good start.

At another time two gentlemen appear in kilts, who pass their time in a long dialogue, the purport of which we were unable to catch, for they were conversing in stage-Scotch. A man then comes forward bearing a clever resemblance to the figure-head of a snuff-shop, and after a few words with about a dozen companions, the entire body proceed to fight a battle; which is immediately done behind the scenes, by four pistols, a crash, and the double-drummer, whose combined efforts present us with a representation of—as the bills kindly inform us—the “Battle of Culloden!” The hero is taken prisoner; but the villain is shot, and his jack-boots are cut off in their prime.

James Dawson is not despatched so quickly; he takes a great deal of dying,—the whole of the third act being occupied by that inevitable operation. Newgate—a “stock” scene at this theatre—an execution, a lady in black and a state of derangement, a muffled drum, and a “view of Kennington Common,” terminate the life of “James Dawson,” who, we had the consolation to observe, from the apathy of the audience, will not be put to the trouble of dying for more than half-a-dozen nights longer.

Before the “Syncretic Society” publishes its next octavo on the state of the Drama, it should send a deputation to the Victoria. There they will observe the written and acted drama in the lowest stage it is possible for even their imaginations to conceive. Even “Martinuzzi” will bear comparison with the “Life and Death of James Dawson.”

At the “Boarding School” established by Mr. Bernard in the Haymarket Theatre, young ladies are instructed in flirting and romping, together with the use of the eyes, at the extremely moderate charges of five and three shillings per lesson; those being the prices of admission to the upper and lower departments of Mr. Webster’s academy, which is hired for the occasion by that accomplished professor of punmanship Bayle Bernard. The course of instruction was, on the opening of the seminary, as follows:—

The lovely pupils were first seen returning from their morning walk in double file, hearts beating and ribbons flying; for they encountered at the door of the school three yeomanry officers. The military being very civil, the eldest of the girls discharged a volley of glances; and nothing could exceed the skill and precision with which the ladies performed their eye-practice, the effects of which were destructive enough to set the yeomanry in a complete flame; and being thus primed and loaded for closer engagements with their charming adversaries, they go off.