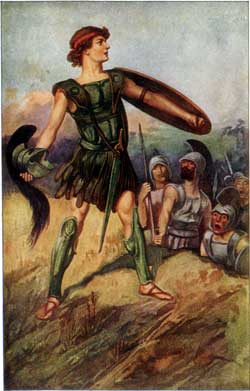

JASON SNATCHED OFF HIS HELMET AND HURLED IT.

Title: Young Folks' Treasury, Volume 2 (of 12)

Editor: Hamilton Wright Mabie

Release date: February 28, 2005 [eBook #15202]

Most recently updated: December 14, 2020

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/15202

Credits: E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Sandra Brown, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

NICHOLAS MURRAY BUTLER, President Columbia University.

WILLIAM R. HARPER, Late President Chicago University.

HON. THEODORE ROOSEVELT, Ex-President of the United States.

HON. GROVER CLEVELAND, Late President of the United States.

JAMES CARDINAL GIBBONS, American Roman Catholic prelate.

ROBERT C. OGDEN, Partner of John Wanamaker.

HON. GEORGE F. HOAR, Late Senator from Massachusetts.

EDWARD W. BOK, Editor "Ladies' Home Journal."

HENRY VAN DYKE, Author, Poet, and Professor of English Literature, Princeton University.

LYMAN ABBOTT, Author, Editor of "The Outlook."

CHARLES G.D. ROBERTS, Writer of Animal Stories.

JACOB A. RIIS, Author and Journalist.

EDWARD EVERETT HALE, Jr., English Professor at Union College.

[pg vi]JOEL CHANDLER HARRIS, Late Author and Creator of "Uncle Remus."

GEORGE GARY EGGLESTON, Novelist and Journalist.

RAY STANNARD BAKER, Author and Journalist.

WILLIAM BLAIKIE, Author of "How to Get Strong and How to Stay So."

WILLIAM DAVENPORT HULBERT, Writer of Animal Stories.

JOSEPH JACOBS, Folklore Writer and Editor of the "Jewish Encyclopedia."

MRS. VIRGINIA TERHUNE ("Marion Harland"), Author of "Common Sense in the Household," etc.

MARGARET E. SANGSTER, Author of "The Art of Home-Making," etc.

SARAH K. BOLTON, Biographical Writer.

ELLEN VELVIN, Writer of Animal Stories.

REV. THEODORE WOOD, F.E.S., Writer on Natural History.

W.J. BALTZELL, Editor of "The Musician."

HERBERT T. WADE, Editor and Writer on Physics.

JOHN H. CLIFFORD, Editor and Writer.

ERNEST INGERSOLL, Naturalist and Author.

DANIEL E. WHEELER, Editor and Writer.

IDA PRENTICE WHITCOMB, Author of "Young People's Story of Music," "Heroes of History," etc.

MARK HAMBOURG, Pianist and Composer.

MME. BLANCHE MARCHESI, Opera Singer and Teacher.

INTRODUCTION xiii

Baucis and Philemon 1

Adapted by C.E. Smith

Pandora 9

Adapted by C.E. Smith

Midas 15

Adapted by C.E. Smith

Cadmus 22

Adapted by C.E. Smith

Proserpina 30

Adapted by C.E. Smith

The Story of Atalanta 49

Adapted by Anna Klingensmith

Pyramus and Thisbe 51

Adapted by Alice Zimmern

Orpheus 53

Adapted by Alice Zimmern

Baldur 57

Adapted from A. and E. Keary's version

Thor's Adventure among the Jotuns 80

Adapted by Hamilton Wright Mabie

The Gifts of the Dwarfs 85

The Punishment of Loki 91

Adapted from A. and E. Keary's version

[pg viii]The Blind Man, The Deaf Man, and the Donkey 96

Adapted by M. Frere

Harisarman 103

Why the Fish Laughed 106

Muchie Lal 111

Adapted by M. Frere

How the Rajah's Son Won the Princess Labam 119

Adapted by Joseph Jacobs

The Jellyfish and the Monkey 129

Adapted by Yei Theodora Ozaki

The Old Man and-the Devils 137

Autumn and Spring 139

Adapted by Frank Kinder

The Vision of Tsunu 142

Adapted by Frank Kinder

The Star-Lovers 144

Adapted by Frank Kinder

The Two Brothers 147

Adapted by Alexander Chodsko

The Twelve Months 150

Adapted by Alexander Chodsko

The Sun; or, the Three Golden Hairs of the Old Man Vésèvde 156

Adapted by Alexander Chodsko

Hiawatha 166

Adapted from H.R. Schoolcraft's version

[pg ix]Perseus 187

Adapted by Mary Macgregor

Odysseus 202

Adapted by Jeanie Lang

The Argonauts 222

Adapted by Mary Macgregor

Theseus 246

Adapted by Mary Macgregor

Hercules 259

Adapted by Thomas Cartwright

The Perilous Voyage of Æneas 273

Adapted by Alice Zimmern

How Horatius Held the Bridge 282

Adapted by Alfred J. Church

How Cincinnatus Saved Rome 284

Adapted by Alfred J. Church

Beowulf 289

Adapted by H.E. Marshall

How King Arthur Conquered Rome 302

Adapted by E. Edwardson

Sir Galahad and the Sacred Cup 314

Adapted by Mary Macgregor

The Passing of Arthur 323

Adapted by Mary Macgregor

Robin Hood 328

Adapted by H.E. Marshall

Guy of Warwick 346

Adapted by H.E. Marshall

Whittington and His Cat 356

Adapted by Ernest Rhys

Tom Hickathrift 364

Adapted by Ernest Rhys

[pg x]The Story of Frithiof 370

Adapted by Julia Goddard

Havelok 383

Adapted by George W. Cox and E.H. Jones

The Vikings 394

Adapted by Mary Macgregor

Siegfried 405

Adapted by Mary Macgregor

Roland 429

Adapted by H.E. Marshall

The Cid 455

Adapted by Robert Southey

William Tell 474

Adapted by H.E. Marshall

Rustem 491

Adapted by Alfred J. Church

Jason Snatched off his Helmet and Hurled it.

Out Flew a Bright, Smiling Fairy.

The Princess Labam ... Shines so that She Lights Up all the Country.

So Danae was Comforted and Went Home With Dictys.

Orpheus Sang Till His Voice Drowned the Song of the Sirens.

They Leapt Across the Pool and came to Him.

Theseus Looked up into Her Fair Face.

The Hero's Shining Sword Pierced the Heart of the Monster.

(Many of the illustrations in this volume are reproduced by special permission of E.P. Dutton & Company, owners of American rights.)

With such a table of contents in front of this little foreword, I am quite sure that few will pause to consider my prosy effort. Nor can I blame any readers who jump over my head, when they may sit beside kind old Baucis, and drink out of her miraculous milk-pitcher, and hear noble Philemon talk; or join hands with Pandora and Epimetheus in their play before the fatal box was opened; or, in fact, be in the company of even the most awe-inspiring of our heroes and heroines.

For ages the various characters told about in the following pages have charmed, delighted, and inspired the people of the world. Like fairy tales, these stories of gods, demigods, and wonderful men were the natural offspring of imaginative races, and from generation to generation they were repeated by father and mother to son and daughter. And if a brave man had done a big deed he was immediately celebrated in song and story, and quite as a matter of course, the deed grew with repetition of these. Minstrels, gleemen, poets, and skalds (a Scandinavian term for poets) took up these rich themes and elaborated them. Thus, if a hero had killed a serpent, in time it became a fiery dragon, and if he won a great battle, the enthusiastic reciters of it had him do prodigious feats—feats beyond belief. But do not fancy from this that the heroes were every-day persons. Indeed, they were quite extraordinary and deserved highest praise of their fellow-men.

So, in ancient and medieval Europe the wandering poet or minstrel went from place to place repeating his wondrous narratives, adding new verses to his tales, changing his episodes to suit locality or occasion, and always skilfully shaping his fascinating romances. In court and cottage he was listened to [pg xiv] with breathless attention. He might be compared to a living novel circulating about the country, for in those days books were few or entirely unknown. Oriental countries, too, had their professional story-spinners, while our American Indians heard of the daring exploits of their heroes from the lips of old men steeped in tradition. My youngest reader can then appreciate how myths and legends were multiplied and their incidents magnified. We all know how almost unconsciously we color and change the stories we repeat, and naturally so did our gentle and gallant singers through the long-gone centuries of chivalry and simple faith.

Every reader can feel the deep significance underlying the myths we present—the poetry and imperishable beauty of the Greek, the strange and powerful conceptions of the Scandinavian mind, the oddity and fantasy of the Japanese, Slavs, and East Indians, and finally the queer imaginings of our own American Indians. Who, for instance, could ever forget poor Proserpina and the six pomegranate seeds, the death of beautiful Baldur, the luminous Princess Labam, the stupid jellyfish and shrewd monkey, and the funny way in which Hiawatha remade the earth after it had been destroyed by flood?

Then take our legendary heroes: was ever a better or braver company brought together—Perseus, Hercules, Siegfried, Roland, Galahad, Robin Hood, and a dozen others? But stop, I am using too many question-marks. There is no need to query heroes known and admired the world over.

As true latter-day story-tellers, both Hawthorne and Kingsley retold many of these myths and legends, and from their classic pages we have adapted a number of our tales, and made them somewhat simpler and shorter in form. By way of apology for this liberty (if some should so consider it), we humbly offer a paragraph from a preface to the "Wonder Book" written by its author:

"A great freedom of treatment was necessary but it will be observed by every one who attempts to render these legends malleable in his intellectual furnace, that they are marvelously independent of all temporary modes and circumstances. They [pg xv] remain essentially the same, after changes that would affect the identity of almost anything else."

Now to those who have not jumped over my head, or to those who, having done so, may jump back to this foreword, I trust my few remarks will have given some additional interest in our myths and heroes of lands far and near.

One evening, in times long ago, old Philemon and his wife Baucis sat at their cottage door watching the sunset. They had eaten their supper and were enjoying a quiet talk about their garden, and their cow, and the fruit trees on which the pears and apples were beginning to ripen. But their talk was very much disturbed by rude shouts and laughter from the village children, and by the fierce barking of dogs.

"I fear," said Philemon, "that some poor traveler is asking for a bed in the village, and that these rough people have set the dogs on him."

"Well, I never," answered old Baucis. "I do wish the neighbors would be kinder to poor wanderers; I feel that some terrible punishment will happen to this village if the people are so wicked as to make fun of those who are tired and hungry. As for you and me, so long as we have a crust of bread, let us always be willing to give half of it to any poor homeless stranger who may come along."

"Indeed, that we will," said Philemon.

These old folks, you must know, were very poor, and had to work hard for a living. They seldom had anything to eat except bread and milk, and vegetables, with sometimes a little honey from their beehives, or a few ripe pears and apples from their little garden. But they were two of the kindest old people in the world, and would have gone without their dinner [pg 2] any day, rather than refuse a slice of bread or a cupful of milk to the weary traveler who might stop at the door.

Their cottage stood on a little hill a short way from the village, which lay in a valley; such a pretty valley, shaped like a cup, with plenty of green fields and gardens, and fruit trees; it was a pleasure just to look at it. But the people who lived in this lovely place were selfish and hard-hearted; they had no pity for the poor, and were unkind to those who had no home, and they only laughed when Philemon said it was right to be gentle to people who were sad and friendless.

These wicked villagers taught their children to be as bad as themselves. They used to clap their hands and make fun of poor travelers who were tramping wearily from one village to another, and they even taught the dogs to snarl and bark at strangers if their clothes were shabby. So the village was known far and near as an unfriendly place, where neither help nor pity was to be found.

What made it worse, too, was that when rich people came in their carriages, or riding on fine horses, with servants to attend to them, the village people would take off their hats and be very polite and attentive: and if the children were rude they got their ears boxed; as to the dogs—if a single dog dared to growl at a rich man he was beaten and then tied up without any supper.

So now you can understand why old Philemon spoke sadly when he heard the shouts of the children, and the barking of the dogs, at the far end of the village street.

He and Baucis sat shaking their heads while the noise came nearer and nearer, until they saw two travelers coming along the road on foot. A crowd of rude children were following them, shouting and throwing stones, and several dogs were snarling at the travelers' heels.

They were both very plainly dressed, and looked as if they might not have enough money to pay for a night's lodging.

"Come, wife," said Philemon, "let us go and meet these poor people and offer them shelter."

"You go," said Baucis, "while I make ready some supper," and she hastened indoors.

Philemon went down the road, and holding out his hand to the two men, he said, "Welcome, strangers, welcome."

"Thank you," answered the younger of the two travelers. "Yours is a kind welcome, very different from the one we got in the village; pray why do you live in such a bad place?"

"I think," answered Philemon, "that Providence put me here just to make up as best I can for other people's unkindness."

The traveler laughed heartily, and Philemon was glad to see him in such good spirits. He took a good look at him and his companion. The younger man was very thin, and was dressed in an odd kind of way. Though it was a summer evening, he wore a cloak which was wrapped tightly about him; and he had a cap on his head, the brim of which stuck out over both ears. There was something queer too about his shoes, but as it was getting dark, Philemon could not see exactly what they were like.

One thing struck Philemon very much, the traveler was so wonderfully light and active that it seemed as if his feet were only kept close to the ground with difficulty. He had a staff in his hand which was the oddest-looking staff Philemon had seen. It was made of wood and had a little pair of wings near the top. Two snakes cut into the wood were twisted round the staff, and these were so well carved that Philemon almost thought he could see them wriggling.

The older man was very tall, and walked calmly along, taking no notice either of naughty children or yelping dogs.

When they reached the cottage gate, Philemon said, "We are very poor folk, but you are welcome to whatever we have in the cupboard. My wife Baucis has gone to see what you can have for supper."

They sat down on the bench, and the younger stranger let his staff fall as he threw himself down on the grass, and then a strange thing happened. The staff seemed to get up from the ground of its own accord, and it opened a little pair of wings and half-hopped, half-flew and leaned itself against the wall of the cottage.

Philemon was so amazed that he feared he had been dreaming, but before he could ask any questions, the elder stranger [pg 4] said: "Was there not a lake long ago covering the spot where the village now stands?"

"Never in my day," said old Philemon, "nor in my father's, nor my grandfather's: there were always fields and meadows just as there are now, and I suppose there always will be."

"That I am not so sure of," replied the stranger. "Since the people in that village have forgotten how to be loving and gentle, maybe it were better that the lake should be rippling over the cottages again," and he looked very sad and stern.

He was a very important-looking man, Philemon felt, even though his clothes were old and shabby; maybe he was some great learned stranger who did not care at all for money or clothes, and was wandering about the world seeking wisdom and knowledge. Philemon was quite sure he was not a common person. But he talked so kindly to Philemon, and the younger traveler made such funny remarks, that they were all constantly laughing.

"Pray, my young friend, what is your name?" Philemon asked.

"Well," answered the younger man, "I am called Mercury, because I am so quick."

"What a strange name!" said Philemon; "and your friend, what is he called?"

"You must ask the thunder to tell you that," said Mercury, "no other voice is loud enough."

Philemon was a little confused at this answer, but the stranger looked so kind and friendly that he began to tell them about his good old wife, and what fine butter and cheese she made, and how happy they were in their little garden; and how they loved each other very dearly and hoped they might live together till they died. And the stern stranger listened with a sweet smile on his face.

Baucis had now got supper ready; not very much of a supper, she told them. There was only half a brown loaf and a bit of cheese, a pitcher with some milk, a little honey, and a bunch of purple grapes. But she said, "Had we only known you were coming, my goodman and I would have gone without anything in order to give you a better supper."

"Do not trouble," said the elder stranger kindly. "A hearty welcome is better than the finest of food, and we are so hungry that what you have to offer us seems a feast." Then they all went into the cottage.

And now I must tell you something that will make your eyes open. You remember that Mercury's staff was leaning against the cottage wall? Well, when its owner went in at the door, what should this wonderful staff do but spread its little wings and go hop-hop, flutter-flutter up the steps; then it went tap-tap across the kitchen floor and did not stop till it stood close behind Mercury's chair. No one noticed this, as Baucis and her husband were too busy attending to their guests.

Baucis filled up two bowls of milk from the pitcher, while her husband cut the loaf and the cheese. "What delightful milk, Mother Baucis," said Mercury, "may I have some more? This has been such a hot day that I am very thirsty."

"Oh dear, I am so sorry and ashamed," answered Baucis, "but the truth is there is hardly another drop of milk in the pitcher."

"Let me see," said Mercury, starting up and catching hold of the handles, "why here is certainly more milk in the pitcher." He poured out a bowlful for himself and another for his companion. Baucis could scarcely believe her eyes. "I suppose I must have made a mistake," she thought, "at any rate the pitcher must be empty now after filling both bowls twice over."

"Excuse me, my kind hostess," said Mercury in a little while, "but your milk is so good that I should very much like another bowlful."

Now Baucis was perfectly sure that the pitcher was empty, and in order to show Mercury that there was not another drop in it, she held it upside down over his bowl. What was her surprise when a stream of fresh milk fell bubbling into the bowl and overflowed on to the table, and the two snakes that were twisted round Mercury's staff stretched out their heads and began to lap it up.

"And now, a slice of your brown loaf, pray Mother Baucis, and a little honey," asked Mercury.

Baucis handed the loaf, and though it had been rather a [pg 6] hard and dry loaf when she and her husband ate some at tea-time, it was now as soft and new as if it had just come from the oven. As to the honey, it had become the color of new gold and had the scent of a thousand flowers, and the small grapes in the bunch had grown larger and richer, and each one seemed bursting with ripe juice.

Although Baucis was a very simple old woman, she could not help thinking that there was something rather strange going on. She sat down beside Philemon and told him in a whisper what she had seen.

"Did you ever hear anything so wonderful?" she asked.

"No, I never did," answered Philemon, with a smile. "I fear you have been in a dream, my dear old wife."

He knew Baucis could not say what was untrue, but he thought that she had not noticed how much milk there had really been in the pitcher at first. So when Mercury once more asked for a little milk, Philemon rose and lifted the pitcher himself. He peeped in and saw that there was not a drop in it; then all at once a little white fountain gushed up from the bottom, and the pitcher was soon filled to the brim with delicious milk.

Philemon was so amazed that he nearly let the jug fall. "Who are ye, wonder-working strangers?" he cried.

"Your guests, good Philemon, and your friends," answered the elder traveler, "and may the pitcher never be empty for kind Baucis and yourself any more than for the hungry traveler."

The old people did not like to ask any more questions; they gave the guests their own sleeping-room, and then they lay down on the hard floor in the kitchen. It was long before they fell asleep, not because they thought how hard their bed was, but because there was so much to whisper to each other about the wonderful strangers and what they had done.

They all rose with the sun next morning. Philemon begged the visitors to stay a little till Baucis should milk the cow and bake some bread for breakfast. But the travelers seemed to be in a hurry and wished to start at once, and they asked Baucis and Philemon to go with them a short distance to show them the way.

So they all four set out together, and Mercury was so full of fun and laughter, and made them feel so happy and bright, that they would have been glad to keep him in their cottage every day and all day long.

"Ah me," said Philemon, "if only our neighbors knew what a pleasure it was to be kind to strangers, they would tie up all their dogs and never allow the children to fling another stone."

"It is a sin and shame for them to behave so," said Baucis, "and I mean to go this very day and tell some of them how wicked they are."

"I fear," said Mercury, smiling, "that you will not find any of them at home."

The old people looked at the elder traveler and his face had grown very grave and stern. "When men do not feel towards the poorest stranger as if he were a brother," he said, in a deep, grave voice, "they are not worthy to remain on the earth, which was made just to be the home for the whole family of the human race of men and women and children."

"And, by the bye," said Mercury, with a look of fun and mischief in his eyes, "where is this village you talk about? I do not see anything of it."

Philemon and his wife turned towards the valley, where at sunset only the day before they had seen the trees and gardens, and the houses, and the streets with the children playing in them. But there was no longer any sign of the village. There was not even a valley. Instead, they saw a broad lake which filled all the great basin from brim to brim, and whose waters glistened and sparkled in the morning sun.

The village that had been there only yesterday was now gone!

"Alas! what has become of our poor neighbors?" cried the kind-hearted old people.

"They are not men and women any longer," answered the elder traveler, in a deep voice like distant thunder. "There was no beauty and no use in lives such as theirs, for they had no love for one another, and no pity in their hearts for those who were poor and weary. Therefore the lake that was here [pg 8] in the old, old days has flowed over them, and they will be men and women no more."

"Yes," said Mercury, with his mischievous smile, "these foolish people have all been changed into fishes because they had cold blood which never warmed their hearts, just as the fishes have."

"As for you, good Philemon, and you, kind Baucis," said the elder traveler, "you, indeed, gave a hearty welcome to the homeless strangers. You have done well, my dear old friends, and whatever wish you have most at heart will be granted."

Philemon and Baucis looked at one another, and then I do not know which spoke, but it seemed as if the voice came from them both. "Let us live together while we live, and let us die together, at the same time, for we have always loved one another."

"Be it so," said the elder stranger, and he held out his hands as if to bless them. The old couple bent their heads and fell on their knees to thank him, and when they lifted their eyes again, neither Mercury nor his companion was to be seen.

So Philemon and Baucis returned to the cottage, and to every traveler who passed that way they offered a drink of milk from the wonderful pitcher, and if the guest was a kind, gentle soul, he found the milk the sweetest and most refreshing he had ever tasted. But if a cross, bad-tempered fellow took even a sip, he found the pitcher full of sour milk, which made him twist his face with dislike and disappointment.

Baucis and Philemon lived a great, great many years and grew very old. And one summer morning when their friends came to share their breakfast, neither Baucis nor Philemon was to be found!

The guests looked everywhere, and all in vain. Then suddenly one of them noticed two beautiful trees in the garden, just in front of the door. One was an oak tree and the other a linden tree, and their branches were twisted together so that they seemed to be embracing.

No one had ever seen these trees before, and while they were all wondering how such fine trees could possibly have grown up in a single night, there came a gentle wind which [pg 9] set the branches moving, and then a mysterious voice was heard coming from the oak tree. "I am old Philemon," it said; and again another voice whispered, "And I am Baucis." And the people knew that the good old couple would live for a hundred years or more in the heart of these lovely trees. And oh, what a pleasant shade they flung around! Some kind soul built a seat under the branches, and whenever a traveler sat down to rest he heard a pleasant whisper of the leaves over his head, and he wondered why the sound should seem to say, "Welcome, dear traveler, welcome."

Long, long ago, when this old world was still very young, there lived a child named Epimetheus. He had neither father nor mother, and to keep him company, a little girl, who was fatherless and motherless like himself, was sent from a far country to live with him and be his playfellow. This child's name was Pandora.

The first thing that Pandora saw, when she came to the cottage where Epimetheus lived, was a great wooden box. "What have you in that box, Epimetheus?" she asked.

"That is a secret," answered Epimetheus, "and you must not ask any questions about it; the box was left here for safety, and I do not know what is in it."

"But who gave it you?" asked Pandora, "and where did it come from?"

"That is a secret too," answered Epimetheus.

"How tiresome!" exclaimed Pandora, pouting her lip. "I wish the great ugly box were out of the way;" and she looked very cross.

"Come along, and let us play games," said Epimetheus; "do not let us think any more about it;" and they ran out to [pg 10] play with the other children, and for a while Pandora forgot all about the box.

But when she came back to the cottage, there it was in front of her, and instead of paying no heed to it, she began to say to herself: "Whatever can be inside it? I wish I just knew who brought it! Dear Epimetheus, do tell me; I know I cannot be happy till you tell me all about it."

Then Epimetheus grew a little angry. "How can I tell you, Pandora?" he said, "I do not know any more than you do."

"Well, you could open it," said Pandora, "and we could see for ourselves!"

But Epimetheus looked so shocked at the very idea of opening a box that had been given to him in trust, that Pandora saw she had better not suggest such a thing again.

"At least you can tell me how it came here," she said.

"It was left at the door," answered Epimetheus, "just before you came, by a queer person dressed in a very strange cloak; he had a cap that seemed to be partly made of feathers; it looked exactly as if he had wings."

"What kind of a staff had he?" asked Pandora.

"Oh, the most curious staff you ever saw," cried Epimetheus: "it seemed like two serpents twisted round a stick."

"I know him," said Pandora thoughtfully. "It was Mercury, and he brought me here as well as the box. I am sure he meant the box for me, and perhaps there are pretty clothes in it for us to wear, and toys for us both to play with."

"It may be so," answered Epimetheus, turning away; "but until Mercury comes back and tells us that we may open it, neither of us has any right to lift the lid;" and he went out of the cottage.

"What a stupid boy he is!" muttered Pandora, "I do wish he had a little more spirit." Then she stood gazing at the box. She had called it ugly a hundred times, but it was really a very handsome box, and would have been an ornament in any room.

It was made of beautiful dark wood, so dark and so highly polished that Pandora could see her face in it. The edges and [pg 11] the corners were wonderfully carved. On these were faces of lovely women, and of the prettiest children, who seemed to be playing among the leaves and flowers. But the most beautiful face of all was one which had a wreath of flowers about its brow. All around it was the dark, smooth-polished wood with this strange face looking out from it, and some days Pandora thought it was laughing at her, while at other times it had a very grave look which made her rather afraid.

The box was not fastened with a lock and key like most boxes, but with a strange knot of gold cord. There never was a knot so queerly tied; it seemed to have no end and no beginning, but was twisted so cunningly, with so many ins and outs, that not even the cleverest fingers could undo it.

Pandora began to examine the knot just to see how it was made. "I really believe," she said to herself, "that I begin to see how it is done. I am sure I could tie it up again after undoing it. There could be no harm in that; I need not open the box even if I undo the knot." And the longer she looked at it, the more she wanted just to try.

So she took the gold cord in her fingers and examined it very closely. Then she raised her head, and happening to glance at the flower-wreathed face, she thought it was grinning at her. "I wonder whether it is smiling because I am doing wrong," thought Pandora, "I have a good mind to leave the box alone and run away."

But just at that moment, as if by accident, she gave the knot a little shake, and the gold cord untwisted itself as if by magic, and there was the box without any fastening.

"This is the strangest thing I have ever known," said Pandora, rather frightened, "What will Epimetheus say? How can I possibly tie it up again?"

She tried once or twice, but the knot would not come right. It had untied itself so suddenly she could not remember in the least how the cord had been twisted together. So there was nothing to be done but to let the box remain unfastened until Epimetheus should come home.

"But," thought Pandora; "when he finds the knot untied he will know that I have done it; how shall I ever make him [pg 12] believe that I have not looked into the box?" And then the naughty thought came into her head that, as Epimetheus would believe that she had looked into the box, she might just as well have a little peep.

She looked at the face with the wreath, and it seemed to smile at her invitingly, as much as to say: "Do not be afraid, what harm can there possibly be in raising the lid for a moment?" And then she thought she heard voices inside, tiny voices that whispered: "Let us out, dear Pandora, do let us out; we want very much to play with you if you will only let us out?"

"What can it be?" said Pandora. "Is there something alive in the box? Yes, I must just see, only one little peep and the lid will be shut down as safely as ever. There cannot really be any harm in just one little peep."

All this time Epimetheus had been playing with the other children in the fields, but he did not feel happy. This was the first time he had played without Pandora, and he was so cross and discontented that the other children could not think what was the matter with him. You see, up to this time everybody in the world had always been happy, no one had ever been ill, or naughty, or miserable; the world was new and beautiful, and the people who lived in it did not know what trouble meant. So Epimetheus could not understand what was the matter with himself, and he stopped trying to play games and went back to Pandora.

On the way home he gathered a bunch of lovely roses, and lilies, and orange-blossoms, and with these he made a wreath to give Pandora, who was very fond of flowers. He noticed there was a great black cloud in the sky, which was creeping nearer and nearer to the sun, and just as Ejpimetheus reached the cottage door the cloud went right over the sun and made everything look dark and sad.

Epimetheus went in quietly, for he wanted to surprise Pandora with the wreath of flowers. And what do you think he saw? The naughty little girl had put her hand on the lid of the box and was just going to open it. Epimetheus saw this quite well, and if he had cried out at once it would have given [pg 13] Pandora such a fright she would have let go the lid. But Epimetheus was very naughty too. Although he had said very little about the box, he was just as curious as Pandora was to see what was inside: if they really found anything pretty or valuable in it, he meant to take half of it for himself; so that he was just as naughty, and nearly as much to blame as his companion.

When Pandora raised the lid, the cottage had grown very dark, for the black cloud now covered the sun entirely and a heavy peal of thunder was heard. But Pandora was too busy and excited to notice this: she lifted the lid right up, and at once a swarm of creatures with wings flew out of the box, and a minute after she heard Epimetheus crying loudly: "Oh, I am stung, I am stung! You naughty Pandora, why did you open this wicked box?"

Pandora let the lid fall with a crash and started up to find out what had happened to her playmate. The thunder-cloud had made the room so dark that she could scarcely see, but she heard a loud buzz-buzzing, as if a great many huge flies had flown in, and soon she saw a crowd of ugly little shapes darting about, with wings like bats and with terribly long stings in their tails. It was one of these that had stung Epimetheus, and it was not long before Pandora began to scream with pain and fear. An ugly little monster had settled on her forehead, and would have stung her badly had not Epimetheus run forward and brushed it away.

Now I must tell you that these ugly creatures with stings, which had escaped from the box, were the whole family of earthly troubles. There were evil tempers, and a great many kinds of cares: and there were more than a hundred and fifty sorrows, and there were diseases in many painful shapes. In fact all the sorrows and worries that hurt people in the world to-day had been shut up in the magic-box, and given to Epimetheus and Pandora to keep safely, in order that the happy children in the world might never be troubled by them. If only these two had obeyed Mercury and had left the box alone as he told them, all would have gone well.

But you see what mischief they had done. The winged [pg 14] troubles flew out at the window and went all over the world: and they made people so unhappy that no one smiled for a great many days. It was very strange, too, that from this day flowers began to fade, and after a short time they died, whereas in the old times, before Pandora opened the box, they had been always fresh and beautiful.

Meanwhile Pandora and Epimetheus remained in the cottage: they were very miserable and in great pain, which made them both exceedingly cross. Epimetheus sat down sullenly in a corner with his back to Pandora, while Pandora flung herself on the floor and cried bitterly, resting her head on the lid of the fatal box.

Suddenly, she heard a gentle tap-tap inside. "What can that be?" said Pandora, raising her head; and again came the tap, tap. It sounded like the knuckles of a tiny hand knocking lightly on the inside of the box.

"Who are you?" asked Pandora.

A sweet little voice came from inside: "Only lift the lid and you will see."

But Pandora was afraid to lift the lid again. She looked across to Epimetheus, but he was so cross that he took no notice. Pandora sobbed: "No, no, I am afraid; there are so many troubles with stings flying about that we do not want any more?"

"Ah, but I am not one of these," the sweet voice said, "they are no relations of mine. Come, come, dear Pandora, I am sure you will let me out."

The voice sounded so kind and cheery that it made Pandora feel better even to listen to it. Epimetheus too had heard the voice. He stopped crying. Then he came forward, and said: "Let me help you, Pandora, as the lid is very heavy."

So this time both the children opened the box, and out flew a bright, smiling little fairy, who brought light and sunshine with her. She flew to Epimetheus and with her finger touched his brow where the trouble had stung him, and immediately the pain was gone.

Then she kissed Pandora, and her hurt was better at once.

"Pray who are you, kind fairy?" Pandora asked.

"I am called Hope," answered the sunshiny figure. "I was shut up in the box so that I might be ready to comfort people when the family of troubles got loose in the world."

"What lovely wings you have! They are just like a rainbow. And will you stay with us," asked Epimetheus, "for ever and ever?"

"Yes," said Hope, "I shall stay with you as long as you live. Sometimes you will not be able to see me, and you may think I am dead, but you will find that I come back again and again when you have given up expecting me, and you must always trust my promise that I will never really leave you."

"Yes, we do trust you," cried both children. And all the rest of their lives when the troubles came back and buzzed about their heads and left bitter stings of pain, Pandora and Epimetheus would remember whose fault it was that the troubles had ever come into the world at all, and they would then wait patiently till the fairy with the rainbow wings came back to heal and comfort them.

Once upon a time there lived a very rich King whose name was Midas, and he had a little daughter whom he loved very dearly. This King was fonder of gold than of anything else in the whole world: or if he did love anything better, it was the one little daughter who played so merrily beside her father's footstool.

But the more Midas loved his daughter, the more he wished to be rich for her sake. He thought, foolish man, that the best thing he could do for his child was to leave her the biggest pile of yellow glittering gold that had ever been heaped together since the world began. So he gave all his thoughts and all his time to this purpose.

When he worked in his garden, he used to wish that the [pg 16] roses had leaves made of gold, and once when his little daughter brought him a handful of yellow buttercups, he exclaimed, "Now if these had only been real gold they would have been worth gathering." He very soon forgot how beautiful the flowers, and the grass, and the trees were, and at the time my story begins Midas could scarcely bear to see or to touch anything that was not made of gold.

Every day he used to spend a great many hours in a dark, ugly room underground: it was here that he kept all his money, and whenever Midas wanted to be very happy he would lock himself into this miserable room and would spend hours and hours pouring the glittering coins out of his money-bags. Or he would count again and again the bars of gold which were kept in a big oak chest with a great iron lock in the lid, and sometimes he would carry a boxful of gold dust from the dark corner where it lay, and would look at the shining heap by the light that came from a tiny window.

To his greedy eyes there never seemed to be half enough; he was quite discontented. "What a happy man I should be," he said one day, "if only the whole world could be made of gold, and if it all belonged to me!"

Just then a shadow fell across the golden pile, and when Midas looked up he saw a young man with a cheery rosy face standing in the thin strip of sunshine that came through the little window. Midas was certain that he had carefully locked the door before he opened his money-bags, so he knew that no one, unless he were more than a mortal, could get in beside him. The stranger seemed so friendly and pleasant that Midas was not in the least afraid.

"You are a rich man, friend Midas," the visitor said. "I doubt if any other room in the whole world has as much gold in it as this."

"May be," said Midas in a discontented voice, "but I wish it were much more; and think how many years it has taken me to gather it all! If only I could live for a thousand years, then I might be really rich.

"Then you are not satisfied?" asked the stranger. Midas shook his head.

"What would satisfy you?" the stranger said.

Midas looked at his visitor for a minute, and then said, "I am tired of getting money with so much trouble. I should like everything I touch to be changed into gold."

The stranger smiled, and his smile seemed to fill the room like a flood of sunshine. "Are you quite sure, Midas, that you would never be sorry if your wish were granted?" he asked.

"Quite sure," said Midas: "I ask nothing more to make me perfectly happy."

"Be it as you wish, then," said the stranger: "from to-morrow at sunrise you will have your desire—everything you touch will be changed into gold."

The figure of the stranger then grew brighter and brighter, so that Midas had to close his eyes, and when he opened them again he saw only a yellow sunbeam in the room, and all around him glittered the precious gold which he had spent his life in gathering.

How Midas longed for the next day to come! He scarcely slept that night, and as soon as it was light he laid his hand on the chair beside his bed; then he nearly cried when he saw that nothing happened: the chair remained just as it was. "Could the stranger have made a mistake," he wondered, "or had it been a dream?"

He lay still, getting angrier and angrier each minute until at last the sun rose, and the first rays shone through his window and brightened the room. It seemed to Midas that the bright yellow sunbeam was reflected very curiously from the covering of his bed, and he sat up and looked more closely.

What was his delight when he saw that the bedcover on which his hands rested had become a woven cloth of the purest and brightest gold! He started up and caught hold of the bed-post—instantly it became a golden pillar. He pulled aside the window-curtain and the tassel grew heavy in his hand—it was a mass of gold! He took up a book from the table, and at his first touch it became a bundle of thin golden leaves, in which no reading could be seen.

Midas was delighted with his good fortune. He took his spectacles from his pocket and put them on, so that he might [pg 18] see more distinctly what he was about. But to his surprise he could not possibly see through them: the clear glasses had turned into gold, and, of course, though they were worth a great deal of money, they were of no more use as spectacles.

Midas thought this was rather troublesome, but he soon forgot all about it. He went downstairs, and how he laughed with pleasure when he noticed that the railing became a bar of shining gold as he rested his hand on it; even the rusty iron latch of the garden door turned yellow as soon as his fingers pressed it.

How lovely the garden was! In the old days Midas had been very fond of flowers, and had spent a great deal of money in getting rare trees and flowers with which to make his garden beautiful.

Red roses in full bloom scented the air: purple and white violets nestled under the rose-bushes, and birds were singing happily in the cherry-trees, which were covered with snow-white blossoms. But since Midas had become so fond of gold he had lost all pleasure in his garden: this morning he did not even see how beautiful it was.

He was thinking of nothing but the wonderful gift the stranger had brought him, and he was sure he could make the garden of far more value than it had ever been. So he went from bush to bush and touched the flowers. And the beautiful pink and red color faded from the roses: the violets became stiff, and then glittered among bunches of hard yellow leaves: and showers of snow-white blossoms no longer fell from the cherry-trees; the tiny petals were all changed into flakes of solid gold, which glittered so brightly in the sunbeams that Midas could not bear to look at them.

But he was quite satisfied with his morning's work, and went back to the palace for breakfast feeling very happy.

Just then he heard his little daughter crying bitterly, and she came running into the room sobbing as if her heart would break. "How now, little lady," he said, "pray what is the matter with you this morning?"

"Oh dear, oh dear, such a dreadful thing has happened!" answered the child. "I went to the garden to gather you [pg 19] some roses, and they are all spoiled; they have grown quite ugly, and stiff, and yellow, and they have no scent. What can be the matter?" and she cried bitterly.

Midas was ashamed to confess that he was to blame, so he said nothing, and they sat down at the table. The King was very hungry, and he poured out a cup of coffee and helped himself to some fish, but the instant his lips touched the coffee it became the color of gold, and the next moment it hardened into a solid lump. "Oh dear me!" exclaimed the King, rather surprised.

"What is the matter, father?" asked his little daughter.

"Nothing, child, nothing," he answered; "eat your bread and milk before it gets cold."

Then he looked at the nice little fish on his plate, and he gently touched its tail with his finger. To his horror it at once changed into gold. He took one of the delicious hot cakes, and he had scarcely broken it when the white flour changed into yellow crumbs which shone like grains of hard sea-sand.

"I do not see how I am going to get any breakfast," he said to himself, and he looked with envy at his little daughter, who had dried her tears and was eating her bread and milk hungrily. "I wonder if it will be the same at dinner," he thought, "and if so, how am I going to live if all my food is to be turned into gold?"

Midas began to get very anxious and to think about many things he had never thought of before. Here was the very richest breakfast that could be set before a King, and yet there was nothing that he could eat! The poorest workman sitting down to a crust of bread and a cup of water was better off than King Midas, whose dainty food was worth its weight in gold.

He began to doubt whether, after all, riches were the only good thing in the world, and he was so hungry that he gave a groan.

His little daughter noticed that her father ate nothing, and at first she sat still looking at him and trying to find out what was the matter. Then she got down from her chair, and running to her father, she threw her arms lovingly round his knees.

Midas bent down and kissed her. He felt that his little [pg 20] daughter's love was a thousand times more precious than all the gold he had gained since the stranger came to visit him. "My precious, precious little girl!" he said, but there was no answer.

Alas! what had he done? The moment that his lips had touched his child's forehead, a change took place. Her sweet, rosy face, so full of love and happiness, hardened and became a glittering yellow color; her beautiful brown curls hung like wires of gold from the small head, and her soft, tender little figure grew stiff in his arms.

Midas had often said to people that his little daughter was worth her weight in gold, and it had become really true. Now when it was too late, he felt how much more precious was the warm tender heart that loved him than all the gold that could be piled up between the earth and sky.

He began to wring his hands and to wish that he was the poorest man in the wide world, if the loss of all his money might bring back the rosy color to his dear child's face.

While he was in despair he suddenly saw a stranger standing near the door, the same visitor he had seen yesterday for the first time in his treasure-room, and who had granted his wish.

"Well, friend Midas," he said, "pray how are you enjoying your new power?"

Midas shook his head. "I am very miserable," he said.

"Very miserable, are you?" exclaimed the stranger. "And how does that happen: have I not faithfully kept my promise; have you not everything that your heart desired?"

"Gold is not everything," answered Midas, "and I have lost all that my heart really cared for."

"Ah!" said the stranger, "I see you have made some discoveries since yesterday. Tell me truly, which of these things do you really think is most worth—a cup of clear cold water and a crust of bread, or the power of turning everything you touch into gold; your own little daughter, alive and loving, or that solid statue of a child which would be valued at thousands of dollars?"

"O my child, my child!" sobbed Midas, wringing his hands. "I would not have given one of her curls for the power of [pg 21] changing all the world into gold, and I would give all I possess for a cup of cold water and a crust of bread."

"You are wiser than you were, King Midas," said the stranger. "Tell me, do you really wish to get rid of your fatal gift?"

"Yes," said Midas, "it is hateful to me."

"Go then," said the stranger, "and plunge into the river that flows at the bottom of the garden: take also a pitcher of the same water, and sprinkle it over anything that you wish to change back again from gold to its former substance."

King Midas bowed low, and when he lifted his head the stranger was nowhere to be seen.

You may easily believe that King Midas lost no time in getting a big pitcher, then he ran towards the river. On reaching the water he jumped in without even waiting to take off his shoes. "How delightful!" he said, as he came out with his hair all dripping, "this is really a most refreshing bath, and surely it must have washed away the magic gift."

Then he dipped the pitcher into the water, and how glad he was to see that it became just a common earthen pitcher and not a golden one as it had been five minutes before! He was conscious, also of a change in himself: a cold, heavy weight seemed to have gone, and he felt light, and happy, and human once more. Maybe his heart had been changing into gold too, though he could not see it, and now it had softened again and become gentle and kind.

Midas hurried back to the palace with the pitcher of water, and the first thing he did was to sprinkle it by handfuls all over the golden figure of his little daughter. You would have laughed to see how the rosy color came back to her cheeks, and how she began to sneeze and choke, and how surprised she was to find herself dripping wet and her father still throwing water over her.

You see she did not know that she had been a little golden statue, for she could not remember anything from the moment when she ran to kiss her father.

King Midas then led his daughter into the garden, where he sprinkled all the rest of the water over the rose-bushes, and [pg 22] the grass, and the trees; and in a minute they were blooming as freshly as ever, and the air was laden with the scent of the flowers.

There were two things left, which, as long as he lived, used to remind King Midas of the stranger's fatal gift. One was that the sands at the bottom of the river always sparkled like grains of gold: and the other, that his little daughter's curls were no longer brown. They had a golden tinge which had not been there before that miserable day when he had received the fatal gift, and when his kiss had changed them into gold.

Cadmus, Phoenix, and Cilix, the three sons of King Agenor, were playing near the seashore in their father's kingdom of Phoenicia, and their little sister Europa was beside them.

They had wandered to some distance from the King's palace and were now in a green field, on one side of which lay the sea, sparkling brightly in the sunshine, and with little waves breaking on the shore.

The three boys were very happy gathering flowers and making wreaths for their sister Europa. The little girl was almost hidden under the flowers and leaves, and her rosy face peeped merrily out among them. She was really the prettiest flower of them all.

While they were busy and happy, a beautiful butterfly came flying past, and the three boys, crying out that it was a flower with wings, set off to try to catch it.

Europa did not run after them. She was a little tired with playing all day long, so she sat still on the green grass and very soon she closed her eyes.

For a time she listened to the sea, which sounded, she thought, just like a voice saying, "Hush, hush," and telling her to go to [pg 23] sleep. But if she slept at all it was only for a minute. Then she heard something tramping on the grass and, when she looked up, there was a snow-white bull quite close to her!

Where could he have come from? Europa was very frightened, and she started up from among the tulips and lilies and cried out, "Cadmus, brother Cadmus, where are you? Come and drive this bull away." But her brother was too far off to hear her, and Europa was so frightened that her voice did not sound very loud; so there she stood with her blue eyes big with fear, and her pretty red mouth wide open, and her face as pale as the lilies that were lying on her golden hair.

As the bull did not touch her she began to peep at him, and she saw that he was a very beautiful animal; she even fancied he looked quite a kind bull. He had soft, tender, brown eyes, and horns as smooth and white as ivory: and when he breathed you could feel the scent of rosebuds and clover blossoms in the air.

The bull ran little races round Europa and allowed her to stroke his forehead with her small hands, and to hang wreaths of flowers on his horns. He was just like a pet lamb, and very soon Europa quite forgot how big and strong he really was and how frightened she had been. She pulled some grass and he ate it out of her hand and seemed quite pleased to be friends. He ran up and down the field as lightly as a bird hopping in a tree; his hoofs scarcely seemed to touch the grass, and once when he galloped a good long way Europa was afraid she would not see him again, and she called out, "Come back, you dear bull, I have got you a pink clover-blossom." Then he came running and bowed his head before Europa as if he knew she was a King's daughter, and knelt down at her feet, inviting her to get on his back and have a ride.

At first Europa was afraid: then she thought there could surely be no danger in having just one ride on the back of such a gentle animal, and the more she thought about it, the more she wanted to go.

What a surprise it would be to Cadmus, and Phoenix, and Cilix if they met her riding across the green field, and what fun it would be if they could all four ride round and round the [pg 24] field on the back of this beautiful white bull that was so tame and kind!

"I think I will do it," she said, and she looked round the field. Cadmus and his brothers were still chasing the butterfly away at the far end. "If I got on the bull's back I should soon be beside them," she thought. So she moved nearer, and the gentle white creature looked so pleased, and so kind, she could not resist any longer, and with a light bound she sprang up on his back: and there she sat holding an ivory horn in each hand to keep her steady.

"Go very gently, good bull," she said, and the animal gave a little leap in the air and came down as lightly as a feather. Then he began a race to that part of the field where the brothers were, and where they had just caught the splendid butterfly. Europa shouted with delight, and how surprised the brothers were to see their sister mounted on the back of a white bull!

They stood with their mouths wide open, not sure whether to be frightened or not. But the bull played round them as gently as a kitten, and Europa looked down all rosy and laughing, and they were quite envious. Then when he turned to take another gallop round the field, Europa waved her hand and called out "Good-by," as if she was off for a journey, and Cadmus, Phoenix, and Cilix shouted "Good-by" all in one breath. They all thought it such good fun.

And then, what do you think happened? The white bull set off as quickly as before, and ran straight down to the seashore. He scampered across the sand, then he took a big leap and plunged right in among the waves. The white spray rose in a shower all over him and Europa, and the poor child screamed with fright. The brothers ran as fast as they could to the edge of the water, but it was too late.

The white bull swam very fast and was soon far away in the wide blue sea, with only his snowy head and tail showing above the water. Poor Europa was holding on with one hand to the ivory horn and stretching the other back towards her dear brothers.

And there stood Cadmus and Phoenix and Cilix looking [pg 25] after her and crying bitterly, until they could no longer see the white head among the waves that sparkled in the sunshine.

Nothing more could be seen of the white bull, and nothing more of their beautiful sister.

This was a sad tale for the three boys to carry back to their parents. King Agenor loved his little girl Europa more than his kingdom or anything else in the world, and when Cadmus came home crying and told how a white bull had carried off his sister, the King was very angry and full of grief.

"You shall never see my face again," he cried, "unless you bring back my little Europa. Begone, and enter my presence no more till you come leading her by the hand;" and his eyes flashed fire and he looked so terribly angry that the poor boys did not even wait for supper, but stole out of the palace wondering where they should go first.

While they were standing at the gate, the Queen came hurrying after them. "Dear children," she said, "I will come with you."

"Oh no, mother," the boys answered, "it is a dark night, and there is no knowing what troubles we may meet with; the blame is ours, and we had better go alone."

"Alas!" said the poor Queen, weeping, "Europa is lost, and if I should lose my three sons as well, what would become of me? I must go with my children."

The boys tried to persuade her to stay at home, but the Queen cried so bitterly that they had to let her go with them.

Just as they were about to start, their playfellow Theseus came running to join them. He loved Europa very much, and longed to search for her too. So the five set off together: the Queen, and Cadmus, and Phoenix, and Cilix, and Theseus, and the last they heard was King Agenor's angry voice saying, "Remember this, never may you come up these steps again, till you bring back my little daughter."

The Queen and her young companions traveled many a weary mile: the days grew to months, and the months became years, and still they found no trace of the lost Princess. Their clothes were worn and shabby, and the peasant people looked curiously at them when they asked, "Have you seen a snow-white [pg 26] bull with a little Princess on its back, riding as swiftly as the wind?"

And the farmers would answer, "We have many bulls in our fields, but none that would allow a little Princess to ride on its back: we have never seen such a sight."

At last Phoenix grew weary of the search. "I do not believe Europa will ever be found, and I shall stay here," he said one day when they came to a pleasant spot. So the others helped him to build a small hut to live in, then they said good-by and went on without him.

Then Cilix grew tired too. "It is so many years now since Europa was carried away that she would not know me if I found her. I shall wait here," he said. So Cadmus and Theseus built a hut for him too, and then said good-by.

After many long months Theseus broke his ankle, and he too had to be left behind, and once more the Queen and Cadmus wandered on to continue the search.

The poor Queen was worn and sad, and she leaned very heavily on her son's arm. "Cadmus," she said one day, "I must stay and rest."

"Why, yes, mother, of course you shall, a long, long rest you must have, and I will sit beside you and watch."

But the Queen knew she could go no further. "Cadmus," she said, "you must leave me here, and, go to the wise woman at Delphi and ask her what you must do next. Promise me you will go!"

And Cadmus promised. The tired Queen lay down to rest, and in the morning Cadmus found that she was dead, and he must journey on alone.

He wandered for many days till he came in sight of a high mountain which the people told him was called Parnassus, and on the steep side of this mountain was the famous city of Delphi for which he was looking. The wise woman lived far up the mountain-side, in a hut like those he had helped his brothers to build by the roadside.

When he pushed aside the branches he found himself in a low cave, with a hole in the wall through which a strong wind was blowing. He bent down and put his mouth to the [pg 27] hole and said, "O sacred goddess, tell me where I must look now for my dear sister Europa, who was carried off so long ago by a bull?"

At first there was no answer. Then a voice said softly, three times, "Seek her no more, seek her no more, seek her no more."

"What shall I do, then?" said Cadmus. And the answer came, in a hoarse voice, "Follow the cow, follow the cow, follow the cow."

"But what cow," cried Cadmus, "and where shall I follow?"

And once more the voice came, "Where the stray cow lies down, there is your home;" and then there was silence.

"Have I been dreaming?" Cadmus thought, "or did I really hear a voice?" and he went away thinking he was very little wiser for having done as the Queen had told him.

I do not know how far he had gone when just before him he saw a brindled cow. She was lying down by the wayside, and as Cadmus came along she got up and began to move slowly along the path, stopping now and then to crop a mouthful of grass.

Cadmus wondered if this could be the cow he was to follow, and he thought he would look at her more closely, so he walked a little faster; but so did the cow. "Stop, cow," he cried, "hey brindle, stop," and he began to run; and much to his surprise so did the cow, and though he ran as hard as possible, he could not overtake her.

So he gave it up. "I do believe this may be the cow I was told about," he thought. "Any way, I may as well follow her and surely she will lie down somewhere."

On and on they went. Cadmus thought the cow would never stop, and other people who had heard the strange story began to follow too, and they were all very tired and very far away from home when at last the cow lay down. His companions were delighted and began to cut down wood to make a fire, and some ran to a stream to get water. Cadmus lay down to rest close beside the cow. He was wishing that his mother and brothers and Theseus had been with him now, [pg 28] when suddenly he was startled by cries and shouts and screams.

He ran towards the stream, and there he saw the head of a big serpent or dragon, with fiery eyes and with wide open jaws which showed rows and rows of horrible sharp teeth. Before Cadmus could reach it, the monster had killed all his poor companions and was busy devouring them. The stream was an enchanted one, and the dragon had been told to guard it so that no mortal might ever touch the water, and the people round about knew this, so that for a hundred years none of them had ever come near the spot.

The dragon had been asleep and was very hungry, and when he saw Cadmus he opened his huge jaws again, ready to devour him too. But Cadmus was very angry at the death of all his companions, and drawing his sword he rushed at the monster. With one big bound he leaped right into the dragon's mouth, so far down that the two rows of terrible teeth could not close on him or do him any harm. The dragon lashed with his tail furiously, but Cadmus stabbed him again and again, and in a short time the great monster lay dead.

"What shall I do now?" he said aloud. All his companions were dead, and he was alone once more. "Cadmus," said a voice, "pluck out the dragon's teeth and plant them in the earth."

Cadmus looked round and there was nobody to be seen. But he set to work and cut out the huge teeth with his sword, and then he made little holes in the ground and planted the teeth. In a few minutes the earth was covered with rows of armed men, fierce-looking soldiers with swords and helmets who stood looking at Cadmus in silence.

"Throw a stone among these men," came the voice again, and Cadmus obeyed. At once all the men began to fight, and they cut and stabbed each other so furiously that in a short time only five remained alive out of all the hundreds that had stood before him. "Cadmus," said the voice once more, "tell these men to stop fighting and help you to build a palace." And as soon as Cadmus spoke, the five big men sheathed their swords, and they began to carry stones, and to carve these for [pg 29] Cadmus, as if they had never thought of such a thing as fighting each other!

They built a house for each of themselves, and there was a beautiful palace for Cadmus made of marble, and of fine kinds of red and green stone, and there was a high tower with a flag floating from a tall gold flag-post.

When everything was ready, Cadmus went to take possession of his new house, and, as he entered the great hall, he saw a lady coming slowly towards him. She was very lovely and she wore a royal robe which shone like sunbeams, with a crown of stars on her golden hair, and round her neck was a string of the fairest pearls.

Cadmus was full of delight. Could this be his long lost sister Europa coming to make him happy after all these weary years of searching and wandering?

How much he had to tell her about Phoenix, and Cilix, and dear Theseus and of the poor Queen's lonely grave in the wilderness! But as he went forward to meet the beautiful lady he saw she was a stranger. He was thinking what he should say to her, when once again he heard the unknown voice speak.

"No, Cadmus," it said, "this is not your dear sister whom you have sought so faithfully all over the wide world. This is Harmonia, a daughter of the sky, who is given to you instead of sister and brother, and friend and mother. She is your Queen, and will make happy the home which you have won by so much suffering."

So King Cadmus lived in the palace with his beautiful Queen, and before many years passed there were rosy little children playing in the great hall, and on the marble steps of the palace, and running joyfully to meet King Cadmus as he came home from looking after his soldiers and his workmen.

And the five old soldiers that sprang from the dragon's teeth grew very fond of these little children, and they were never tired of showing them how to play with wooden swords and to blow on a penny trumpet, and beat a drum and march like soldiers to battle.

Mother Ceres was very fond of her little daughter Proserpina. She did not of ten let her go alone into the fields for fear she should be lost. But just at the time when my story begins she was very busy. She had to look after the wheat and the corn, and the apples and the pears, all over the world, and as the weather had been bad day after day she was afraid none of them would be ripe when harvest-time came.

So this morning Mother Ceres put on her turban made of scarlet poppies and got into her car. This car was drawn by a pair of winged dragons which went very fast, and Mother Ceres was just ready to start, when Proserpina said, "Dear mother, I shall be very lonely while you are away, may I run down to the sands, and ask some of the sea-children to come out of the water to play with me?"

"Yes, child, you may," answered Mother Ceres, "but you must take care not to stray away from them, and you are not to play in the fields by yourself with no one to take care of you."

Proserpina promised to remember what her mother said, and by the time the dragons with their big wings had whirled the car out of sight she was already on the shore, calling to the sea-children to come to play with her.

They knew Proserpina's voice and came at once: pretty children with wavy sea-green hair and shining faces, and they sat down on the wet sand where the waves could still break over them, and began to make a necklace for Proserpina of beautiful shells brought from their home at the bottom of the sea.

Proserpina was so delighted when they hung the necklace round her neck that she wanted to give them something in return. "Will you come with me into the fields," she asked, "and I will gather flowers and make you each a wreath?"

"Oh no, dear Proserpina," said the sea-children, "we may [pg 31] not go with you on the dry land. We must keep close beside the sea and let the waves wash over us every minute or two. If it were not for the salt water we should soon look like bunches of dried sea-weed instead of sea-children."

"That is a great pity," said Proserpina, "but if you wait for me here, I will run to the fields and be back again with my apron full of flowers before the waves have broken over you ten times. I long to make you some wreaths as beautiful as this necklace with all its colored shells."

"We will wait, then," said the sea-children: "we will lie under the water and pop up our heads every few minutes to see if you are coming."

Proserpina ran quickly to a field where only the day before she had seen a great many flowers; but the first she came to seemed rather faded, and forgetting what Mother Ceres had told her, she strayed a little farther into the fields. Never before had she found such beautiful flowers! Large sweet-scented violets, purple and white; deep pink roses; hyacinths with the biggest of blue bells; as well as many others she did not know. They seemed to grow up under her feet, and soon her apron was so full that the flowers were falling out of the corners.

Proserpina was just going to turn back to the sands to make the wreaths for the sea-children, when she cried out with delight. Before her was a bush covered with the most wonderful flowers in the world. "What beauties!" said Proserpina, and then she thought, "How strange! I looked at that spot only a moment ago; why did I not see the flowers?"

They were such lovely ones too. More than a hundred different kinds grew on the one bush: the brightest, gayest flowers Proserpina had ever seen. But there was a shiny look about them and about the leaves which she did not quite like. Somehow it made her wonder if this was a poison plant, and to tell the truth she was half inclined to turn round and run away.

"How silly I am!" she thought, taking courage: "it is really the most beautiful bush I ever saw. I will pull it up by the roots and carry it home to plant in mother's garden."

Holding her apron full of flowers with one hand, Proserpina seized the large shrub with the other and pulled and pulled.

What deep roots that bush had! She pulled again with all her might, and the earth round the roots began to stir and crack, so she gave another big pull, and then she let go. She thought there was a rumbling noise right below her feet, and she wondered if the roots went down to some dragon's cave. Then she tried once again, and up came the bush so quickly that Proserpina nearly fell backwards. There she stood, holding the stem in her hand and looking at the big hole which its roots had left in the earth.

To her surprise this hole began to grow wider and wider, and deeper and deeper, and a rumbling noise came out of it. Louder and louder it grew, nearer and nearer it came, just like the tramp of horses' feet and the rattling of wheels.

Proserpina was too frightened now to run away, and soon she saw a wonderful thing. Two black horses, with smoke coming out of their nostrils and with long black tails and flowing black manes, came tearing their way out of the earth, and a splendid golden chariot was rattling at their heels.

The horses leaped out of the hole, chariot and all, and came close to the spot where Proserpina stood.

Then she saw there was a man in the chariot. He was very richly dressed, with a crown on his head all made of diamonds which sparkled like fire. He was a very handsome man, but looked rather cross and discontented, and he kept rubbing his eyes and covering them with his hand, as if he did not care much for the bright sunshine.

As soon as he saw Proserpina, the man waved to her to come a little nearer. "Do not be afraid," he said. "Come! would you not like to ride a little way with me in my beautiful chariot?"

But Proserpina was very frightened, and no wonder. The stranger did not look a very kind or pleasant man. His voice was so gruff and deep, and sounded just like the rumbling Proserpina had heard underneath the earth.

She at once began to cry out, "Mother, mother! O Mother Ceres, come quickly and save me!"

But her voice was very shaky and too faint for Mother Ceres to hear, for by this time she was many thousands of miles away making the corn grow in another country.

No sooner did Proserpina begin to cry out than the strange man leaped to the ground; he caught her in his arms and sprang into the chariot, then he shook the reins and shouted to the two black horses to set off. They began to gallop so fast that it was just like flying, and in less than a minute Proserpina had lost sight of the sunny fields where she and her mother had always lived.

She screamed and screamed and all the beautiful flowers fell out of her apron to the ground.

But Mother Ceres was too far away to know what was happening to her little daughter.

"Why are you so frightened, my little girl?" said the strange man, and he tried to soften his rough voice. "I promise not to do you any harm. I see you have been gathering flowers? Wait till we come to my palace and I will give you a garden full of prettier flowers than these, all made of diamonds and pearls and rubies. Can you guess who I am? They call me Pluto, and I am the King of the mines where all the diamonds and rubies and all the gold and silver are found: they all belong to me. Do you see this lovely crown on my head? I will let you have it to play with. Oh, I think we are going to be very good friends when we get out of this troublesome sunshine."

"Let me go home," sobbed Proserpina, "let me go home."

"My home is better than your mother's," said King Pluto. "It is a palace made of gold, with crystal windows and with diamond lamps instead of sunshine; and there is a splendid throne; if you like you may sit on it and be my little Queen, and I will sit on the footstool."

"I do not care for golden palaces and thrones," sobbed Proserpina. "O mother, mother! Take me back to my mother."

But King Pluto only shouted to his horses to go faster.

"You are very foolish, Proserpina," he said, rather crossly. "I am doing all I can to make you happy, and I want very [pg 34] much to have a merry little girl to run upstairs and downstairs in my palace and make it brighter with her laughter. This is all I ask you to do for King Pluto."

"Never" answered Proserpina, looking very miserable. "I shall never laugh again, till you take me back to my mother's cottage."

And the horses galloped on, and the wind whistled past the chariot, and Proserpina cried and cried till her poor little voice was almost cried away, and nothing was left but a whisper.

The road now began to get very dull and gloomy. On each side were black rocks and very thick trees and bushes that looked as if they never got any sunshine. It got darker and darker, as if night was coming, and still the black horses rushed on leaving the sunny home of Mother Ceres far behind.

But the darker it grew, the happier King Pluto seemed to be. Proserpina began to peep at him, she thought he might not be such a wicked man after all.

"Is it much further," she asked, "and will you carry me back when I have seen your palace?"

"We will talk of that by and by," answered Pluto. "Do you see these big gates? When we pass these we are at home; and look! there is my faithful dog at the door! Cerberus; Cerberus, come here, good dog."

Pluto pulled the horses' reins, and the chariot stopped between two big tall pillars. The dog got up and stood on his hind legs, so that he could put his paws on the chariot wheel. What a strange dog he was! A big, rough, ugly-looking monster, with three heads each fiercer than the other.

King Pluto patted his heads and the dog wagged his tail with delight. Proserpina was much afraid when she saw that his tail was a live dragon, with fiery eyes and big poisonous teeth.

"Will the dog bite me?" she asked, creeping closer to King Pluto. "How very ugly he is."

"Oh, never fear," Pluto answered; "he never bites people unless they try to come in here when I do not want them. Down, Cerberus. Now, Proserpina, we will drive on."

The black horses started again and King Pluto seemed very happy to find himself once more at home.

All along the road Proserpina could see diamonds, and rubies and precious stones sparkling, and there were bits of real gold among the rocks. It was a very rich place.

Not far from the gateway they came to an iron bridge. Pluto stopped the chariot and told Proserpina to look at the river which ran underneath. It was very black and muddy, and flowed slowly, very slowly, as if it had quite forgotten which way it wanted to go, and was in no hurry to flow anywhere.

"This is the river Lethe," said King Pluto; "do you not think it a very pleasant stream?"

"I think it is very dismal," said Proserpina.