Title: The Olden Time Series, Vol. 5: Some Strange and Curious Punishments

Author: Henry M. Brooks

Release date: August 3, 2005 [eBook #16419]

Most recently updated: December 12, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

"Old and new make the warp and woof of every moment. There is no thread that is not a twist of these two strands. By necessity, by proclivity, and by delight, we all quote."—Emerson

BOSTON

TICKNOR AND COMPANY

1886

Copyright, 1886,

By Ticknor and Company.

All rights reserved.

University Press:

John Wilson and Son, Cambridge.

Yet, taught by time, my heart has learned to glow

For others' good, and melt at others' woe.

Pope: Odyssey.

But hushed be every thought that springs

From out the bitterness of things.

Wordsworth.

In the month of January, 1761, "Joseph Bennett, John Jenkins, Owen McCarty, and John Wright were publickly whipt at the Cart's Tail thro' the City of New York for petty Larceny,"—so the newspaper account states,—"pursuant to Sentence inflicted on them by the Court of Quarter Sessions held last Week for the Trial of Robbers," etc. In March the same year "One Andrew Cayto received 49 Stripes at the public Whipping Post" in Boston "for House-robbing; viz., 39 for robbing one House, and 10 for robbing another." In 1762 "Jeremiah Dexter, of Walpole, pursuant to Sentence, stood in the Pillory in that Town the space of one Hour for uttering two Counterfeit Mill'd Dollars, knowing them to be such." At Ipswich, Mass., June 16, 1763, "one Francis Brown, for stealing a large quantity of Goods, was found Guilty, and it being the second Conviction, he was sentenced by the Court to sit on the Gallows an Hour with a Rope about his Neck, to be whipt 30 Stripes, and pay treble Damages. He says he was born in Lisbon, and has been a great Thief."

We extract the following from the "Boston Chronicle," Nov. 20, 1769:—

We hear from Worceſter that on the eighth inſtant one Lindſay ſtood in the Pillory there one hour, after which he received 30 ſtripes at the public whipping poſt, and was then branded in the hand; his crime was forgery.

Lindsay was probably branded with the letter F, by means of a hot iron, on the palm of his right hand; this was the custom in such cases.

In Boston, in June, 1762, "the noted Dr. Seth Hudson and Joshua How stood a second Time in the Pillory for the space of one Hour, and the former received 20 and the latter 39 Stripes." In the same town in February, 1764, "one David Powers for Stealing was sentenced to be whip't 20 Stripes, to pay tripel Damages, being £30, and Costs. And one John Gray, Cordwainer, for endeavouring to spread the Infection of the Small Pox, was sentenced to pay a Fine of £6, to suffer three months' Imprisonment, and to pay Costs." In New York in January, 1767, "A Negro Wench was executed for stealing sundry Articles out of the House of Mr. Forbes; and one John Douglass was burnt in the Hand for Stealing a Copper Kettle." In the last half of the eighteenth century it appears to have been a capital crime for negroes to steal. At Springfield, Mass., in October, 1767, "one Elnathan Muggin was found Guilty of passing Counterfeit Dollars, and sentenced to have his Ears cropped," etc. On reading these quaint accounts we are led to inquire whether the punishment for crime in "olden times" was more severe than at the present time. Many people think it was, and justly so, and argue that crime has consequently greatly increased of late years, on account of the lightness of modern sentences or the uncertainty about punishment. This may be true. Crime is said to increase with population always. According to Mr. Buckle, it can be calculated with a considerable degree of accuracy. We can estimate, for instance, the probable number of murders which will take place in a year in a given number of inhabitants. Whether this theory is true or not would require a vast amount of study and observation to determine. We know that population in our time crowds in cities; especially is this true of the classes most likely to furnish criminals. Still, in spite of this, do not most of us feel that it has of late years been rather safer to reside in a city than in the country? Consider the numbers of lawless and too often cruel tramps which have overrun the country towns and villages for a few years past, making it so unsafe for women to walk unattended in woods and highways, even in the quietest parts of New England, where once they could go with perfect safety alone and at all hours. No laws can be too severe against cruel tramps. It has been affirmed that people who live in cities are in reality more moral than country people of the same class.

Is this state of things brought about by the infliction of light sentences, or is it caused by the increase among us of a bad foreign element? We have heard many serious and humane persons express themselves as in favor of a restoration of the whipping-post and stocks, really supposing that these things would lessen crime. But is it likely that the old methods of punishment would be considered by criminals themselves as severer than the present? Let us see what some of the last century rogues thought about the matter. At a session of the Supreme Judicial Court held at Salem, Mass., in December, 1788, one James Ray was sentenced, for stealing goods from the shop of Captain John Hathorne (a relative of Nathaniel Hawthorne), to sit upon the gallows with a rope about his neck for an hour, to be whipped with thirty-nine stripes, and to be confined to hard labor on Castle Island (Boston Harbor) for three years. "It is observable of this man," the account continues, "that he has been lately released from a two years' service at the Castle, that during the trial he was very merry and impudent, and continued in the same humor while his sentence was reading, holding up his head and looking boldly at the Court, till the three years' confinement was mentioned; when his countenance changed, his head dropped on his breast, and he fetched a deep groan,—an instance of how much more dreadful the idea of labor is to such villains than that of Corporal punishment."

At a session of the Court of Oyer and Terminer held at Norristown, Pa., for the county of Montgomery, Oct. 11, 1786, we are furnished with a case in point. "A bill was presented against Philip Hoosnagle for burglary, who was convicted by the traverse Jury on the clearest testimony. He was, after a very pathetick and instructing admonition from the bench, sentenced to five years' hard labour, under the new act of Assembly. It was with some difficulty that this reprobate was prevailed upon to make the election of labour instead of the halter, ... a convincing proof," the report says, "that the punishments directed by the new law are more terrifying to idle vagabonds than all the horrors of an ignominious death."

Probably there are many more cases on record where criminals preferred death to imprisonment. Burglary and forgery were once punished by death. We have all noticed on the old Continental currency these words: "Death to counterfeit this."

On the 17th June, 1791, Samuel Cook, in the eighty-fourth year of his age, was executed at Johnstown, N.Y., for forgery. On the 6th December, 1787, William Clarke was executed at Northampton for burglary; the same day Charles Rose and Jonathan Bly were executed at Lenox for robbery. On the 4th May, 1786, at Worcester, Johnson Green, indicted for three burglaries committed in one night within the space of about half a mile, was tried on one indictment, convicted, and received sentence of death. The papers contain numerous similar cases. It would be useless to enumerate them all; we give only a few in order to show what the punishment formerly awarded to these crimes really was. We do not, of course, know the circumstances attending all these cases; but robbery and burglary are usually premeditated, and the criminals are prepared to commit murder if it should be necessary for their purpose, so that we can have no sympathy with the perpetrators. Our sympathy ought, we think, to go to the victims.

OLD NEW ENGLAND.

Early in the settlement of New England, as is pretty generally known, some of the laws and punishments were singular enough. A few extracts from Felt's "Annals of Salem" may not be out of place here, as illustrating our subject:—

"In 1637, Dorothy Talby, for beating her husband, is ordered to be bound and chained to a post."

"In 1638, the Assistants order two Salem men to sit in the Stocks, on Lecture day, for travelling on the Sabbath."

"In 1644, Mary, wife of Thomas Oliver, was sentenced to be publickly whipped for reproaching the Magistrates."

"In August, 1646, for slandering the Elders, she had a cleft stick put on her tongue for half an hour." Felt says: "It is evident that her standing out for what she considered 'woman's rights' brought her into frequent and severe trouble. Mr. Winthrop says that she excelled Mrs. Hutchinson in zeal and eloquence."

She finally, in 1650, left the colony, after having caused much trouble to the Church and the authorities.

"In 1649, women were prosecuted in Salem for scolding," and probably in many cases whipped or ducked.

"May 15, 1672, the General Court of Massachusetts orders that Scolds and Railers shall be gagged or set in a ducking-stool and dipped over head and ears three times."

This treatment we should suppose would be likely to make the victims very pleasant, especially in cold weather.

"May 3, 1669, Thomas Maule is ordered to be whipped for saying that Mr. Higginson preached lies, and that his instruction was 'the doctrine of devils.'"

Josiah Southwick, Mrs. Wilson, Mrs. Buffum, and others, Quakers, for making disturbances in the meeting-house, etc., were whipped at the cart's tail through the town. Southwick, for returning after having been banished, was whipped through the towns of Boston, Roxbury, and Dedham. These are only a few of the cases of the punishments inflicted upon the Quakers. Mr. Felt says in reference to the persecution of the Quakers:

"Before any new denomination becomes consolidated, some of its members are apt to show more zeal than discretion. No sect who are regular and useful should have an ill name for the improprieties committed by a few of them."

Our "pious forefathers," we must confess, were too apt to be a little hard towards those who annoyed them with their tongue and pen upon Church doctrine and discipline or the administration of the government. As early as 1631, one Philip Ratclif is sentenced by the Assistants to pay £40, to be whipped, to have his ears cropped, and to be banished. What had he done to merit such a punishment as this? He had made "hard speeches against Salem Church, as well as the Government." "The execution of this decision," Mr. Felt says, "was represented in England to the great disadvantage of Massachusetts." Jeffries was not yet on the bench in England.

In 1652 a man was fined for excess of apparel "in bootes, rebonds, gould and silver lace."

Mr. Charles W. Palfrey contributed in 1866 to the "Salem Register" the following interesting item on the Salem witchcraft trials:

Among the many attempts to remedy the mischiefs caused by the witchcraft delusion, the subjoined is not without interest. About eighteen years after the memorable year, 1692, four members, a committee of the Legislature, were sent to Salem to hear certain parties and receive certain petitions, and the following is the record, in the Journal, of their Report:—

October 26, 1711. Present in Council, His Excellency Joseph Dudley, Esqr., Governor, John Hathorne, Samuel Sewall, Jonathan Corwin, Joseph Lynde, Penn Townsend, John Higginson, Daniel Epes, Andrew Belcher, etc., etc.

Report of the Committee appointed, Relating to the Affair of Witchcraft in the year 1692; viz.—

We whose Names are subscribed in Obedience to your Honours' Act at a Court held the last of May, 1710, for our inserting the Names of the several Persons who were condemned for Witchcraft in the year 1692, & of the Damages they sustained by their prosecution; Being met at Salem, for the Ends aforesaid, the 13th Septem., 1710, Upon Examination of the Records of the several Persons condemned, Humbly offer to your Honours the Names as follows, to be inserted for the Reversing their Attainders: Elizabeth How, George Jacob, Mary Easty, Mary Parker, Mr. George Burroughs, Gyles Cory & Wife, Rebecca Nurse, John Willard, Sarah Good, Martha Carrier, Samuel Wardel, John Procter, Sarah Wild, Mary Bradbury, Abigail Falkner, Abigail Hobbs, Ann Foster, Rebecca Eams, Dorcas Hoar, Mary Post, Mary Lacy:

And having heard the several Demands of the Damages of the aforesaid Persons & those in their behalf; & upon Conference have so moderated their respective Demands that We doubt not but they will be readily complied with by your Honours.

Which respective Demands are as follows:—

Elizabeth How, Twelve Pounds; George Jacob, Seventy nine Pounds; Mary Easty, Twenty Pounds; Mary Parker, Eight Pounds; Mr. George Burroughs, Fifty Pounds; Gyles Core & Martha Core his Wife, Twenty one Pounds; Rebecca Nurse, Twenty five Pounds; John Willard, Twenty Pounds; Sarah Good, Thirty Pounds; Martha Carrier, Seven Pounds six shillings; Samuel Wardell & Sarah his Wife, Thirty six Pounds fifteen shillings; John Proctor & —— Proctor his Wife, One Hundred and fifty Pounds; Sarah Wilde, Fourteen Pounds; Mrs. Mary Bradbury, Twenty Pounds; Abigail Faulkner, Twenty Pounds; Abigail Hobbs, Ten Pounds; Ann Foster, Six Pounds ten shillings; Rebecca Eams, Ten Pounds; Dorcas Hoar, Twenty one Pounds seventeen shillings; Mary Post Eight Pounds fourteen shillings; Mary Lacey Eight Pounds ten shillings. The Whole amounting unto Five Hundred & seventy eight Pounds, & twelve shillings.

(Sign'd) Jno. Appleton, Thomas Noyes, John Burrill, Nehem'a Jewett.

Salem, Septemr. 14, 1711.

Read & Accepted in the House of Represent'ves

Signed JOHN BURRILL Speak'r

Read & Concur'd in Council

Consented to J. DUDLEY.

The following quaint memorandum of the expenses of the commission is minuted in the report, viz.:—

Ye Acct of gr servts

| Charges 3 days a peis ourselves & horses | 4.0.0. |

| Entertainment at Salem Mr. Pratts | 1.3.0. |

|

Major Sewals attendans & sendg notifications

to all Concerned |

1.0.0. |

| £6.3.0. |

It is a grave error into which many modern writers have been drawn, when alluding to Salem witchcraft, to lay the responsibility of that dire delusion entirely upon Salem people, as if they alone were to be held accountable for the dreadful occurrences of 1692. The laws of England in those days, all the authorities of New England, and, with but rare exceptions, all the people everywhere throughout the civilized world, recognized witchcraft as a fact and believed it to be a crime. The most learned men in England and in other countries believed fully in witchcraft. Sir Matthew Hale had given a legal opinion on the subject; Lord Bacon believed in witchcraft; and there are strong reasons for thinking that Shakspeare and other great men of the time of Queen Elizabeth and still later believed in it fully. Cotton Mather, Judge Sewall, Peter Sargent, Lieutenant-Governor Stoughton, all belonging to Boston, were the leaders in the proceedings against the witches of 1692.

HUNG IN CHAINS.

In the papers that we have examined we have not found any instances recorded of the old English law of hanging the remains of executed criminals in chains as having been carried into effect in our country. But from some investigations of Mr. James E. Mauran, of Newport, R.I., we learn that on March 12, 1715, one Mecum of that town was executed for murder and his body was hung in chains on Miantonomy Hill, where the remains of an Indian were then hanging, who had been executed Sept. 12, 1712. Mecum was a Scotchman, and lived at the head of Broad Street. A negro was hanged in Newport in 1679, and his remains were exposed on the same hill.

A BOOK ORDERED TO BE BURNED BY THE COUNCIL IN 1695.

The "Salem Observer" of Feb. 14, 1829, quotes from the Rev. Dr. Bentley's "Diary" as follows:—

Tho's Maule, shopkeeper of Salem, is brought before the Council to answer for his printing and publishing a pamphlet of 260 pages, entitled "Truth held forth and maintained," owns the book but will not own all, till he sees his copy which is at New-York with Bradford, who printed it. Saith he writt to ye Gov'r of N. York before he could get it printed. Book is ordered to be burnt—being stuff'd with notorious lyes and scandals, and he recognizes to answer it next Court of Assize and gen'l gaol delivery to be held for the County of Essex. He acknowledges that what was written concerning the circumstance of Major Gen. Atherton's death was a mistake (p. 112 and 113), was chiefly insisted on against him, which I believe was a surprize to him, he expecting to be examined in some point of religion, as should seem by his bringing his bible under his arm.

Thomas Maule was a Quaker who lived in Essex Street, Salem, on the spot now occupied by James B. Curwen, Esq., as a residence.

Imported books were ordered to be burned in Boston as early as 1653, by command of the General Court; but we believe this is the first instance of burning an American book.

Punishment for wearing long hair in New England. From an old Salem paper.

Puritanical Zeal. It is known that there was one of the statutes in our ancestors' code which imposed a penalty for the wearing of long hair. At the time Endicott was the magistrate of this town he caused the following order to be passed:—

"John Gatshell is fyened ten shillings for building upon the town's ground without leave; and in case he shall cutt of his loung hair of his head in to sevill frame (fewell flame?) in the meane time, shall have abated five shillings his fine, to be paid in to the Towne meeting within two months from this time, and have leave to go in his building in the meantime."

Purchas says of long hair that—

"It is an ornament to the female sex, a token of subjection, an ensign of modesty; but modesty grows short in men as their hair grows long, and a neat perfumed, frizled, pouldered bush hangs but as a token,—vini non vendibilis, of much wine, little wit, of men weary of manhood, of civility, of christianity, which would faine turn (as the least doe imitate) American salvages, infidels, barbarians, or women at the least and best."

Prynne, who wrote in 1632, considers men who nourish their hair like women, as an abomination to the Lord, and says—

"No wonder that the wearing of long haire should make men abominable unto God himselfe, since it was an abomination even among heathen men. Witnesse the examples of Heliogabalus, Sardanapalus, Nero, Sporus, Caius Caligula, and others."

He refers to the opinions of the fathers and the decrees of the Old Councils to prove that—

"Long hair and love locks are bushes of vanity whereby the Devil leads and holds men captive."

In a Boston paper, Aug. 11, 1789, we find the following ludicrous account of the unfaithfulness of an officer in the duty of whipping a culprit:—

On Thurſday, 11 culprits received the diſcipline of the poſt in this town. The perſon obtained by the High Sheriff to inflict the puniſhment, from ſympathetick feeling for his brother culprits, was very tender in dealing out his ſtrokes, and not adding weight to them, although repeatedly ordered; the Sheriff, to his honour, took the whip from his hand, by an application of it to his ſhoulders drove him from the ſtage, and with the aſſiſtance of his Deputies inflicted the puniſhment of the law on all the culprits. The citizens who were aſſembled, complimented the Sheriff with three cheers for the manly, determined manner in which he executed his duty.

In the "Boston Courier," September, 1825, is an account of the conviction of a common drunkard at the age of 103! It seems hardly possible that such a case could have occurred, and in New England, too. This item is copied from the "Salem Observer." If it is true, it can hardly be said that the man shortened his days by the use of liquor. They had, however, good, pure rum in those days.

Police Court. Donald McDonald, a Scotchman reported to be one hundred and three years of age, was brought before the court yesterday charged with being a common drunkard, of which he had been convicted once before. Donald stated that he had been in various battles of the Revolution, had sailed with Paul Jones, and was at the taking of Quebec. He was found guilty and sentenced to the House of Correction for three months.

Donald M'Donald, the Scotchman, who has numbered upwards of 110 years, was sent to the House of Industry on Saturday of last week, in a state of intoxication. He had been suffered to go at large but four days previous, and during two of them was seen about our streets a drunken brawler.—Boston Patriot, 1829.

NEW ENGLAND IN 1686.

John Dunton, writing from Boston in 1686 to his friends in England, quotes some of the Province laws then in force. He says:—

For being drunk they either Whip or impoſe a Fine of Five ſhillings; And yet, notwithſtanding this Law, there are ſeveral of them ſo addicted to it that they begin to doubt whether it be a Sin or no, and ſeldom go to Bed without Muddy Brains.

For Curſing and Swearing they bore through the Tongue with a hot Iron.

For kiſſing a woman in the Street, though but in way of Civil Salute, Whipping or a Fine (Their way of Whipping Criminals is by Tying them to a Gun at the Town Houſe, and when ſo Ty'd whipping them at the pleaſure of the Magiſtrate and according to the Nature of the Offence).

For Adultery they are put to Death, and ſo for Witchcraft, For that, there are a great many Witches in this Country &c.

Scolds they gag and ſet them at their own Doors, for certain hours together for all comers and goers to gaze at. Were this a Law in England and well Executed it wou'd in a little Time prove an Effectual Remedy to cure the Noiſe that is in many Women's heads.

Stealing is puniſhed with Reſtoring four-fold if able; if not, they are ſold for ſome years, and ſo are poor Debtors. I have not heard of many Criminals of this ſort. But for Lying and Cheating they out-vye Judas and all the falſe other cheats in Hell. Nay, they make a Sport of it: Looking upon Cheating as a commendable Piece of Ingenuity, commending him that has the moſt ſkill to commit a piece of Roguery; which in their Dialect (like thoſe of our Yea-and-Nay-Friends in England) they call by the genteel Name of Out-Witting a Man and won't own it to be cheating.

After mentioning the case of a man in Boston who bought a horse of a countryman who could not read and gave him a note payable at the "Day of the Resurrection," etc. Dunton goes on to say: "In short, These Bostonians enrich themselves by the ruine of Strangers, etc.... But all these things pass under the Notion of Self-Preservation and Christian Policy."

It would hardly be fair to quote all this from Dunton's letters unless we added what he says of Boston in another place; namely, "And though the Generality are what I have described them, yet is there as sincere a Pious and truly Religious People among them as is any where in the Whole World to be found."

It seems to have been quite common at one time to sell prisoners. At the Supreme Judicial Court in Salem, in November, 1787, "Elizabeth Leathe of Lynn, for harbouring thieves and receiving stolen goods, was convicted and sentenced to be whipped twenty stripes and to be sold for six months." Also at a session of the same Court, held in Boston in September, 1791, six persons were convicted of theft and sentenced to be whipped and pay costs, or to be sold for periods of from six months to four years. At this same Court one Seth Johnson appears to have received what seems to us a rather severe sentence, although of course we do not know all the circumstances of the case. He was convicted of theft on three indictments and was sentenced to be "whipt 65 stripes and confined to hard labor for nine years." The Court at Salem, before referred to, passed on one Catharine Derby a very heavy sentence for stealing from Captain Hathorne's shop. It was, "To sit upon the gallows one hour with a rope about her neck, to be whipped 20 stripes, pay £14 to Capt. Hathorne, and costs of prosecution." This is almost as bad as the old saying, "being hung and paying forty shillings."

This practice of selling convicts was nothing more or less than making slaves of them,—for a limited period, of course; but perhaps it was in many instances a punishment more to be desired by the victims than being confined in prison, especially if they were well treated. The prisons in those days had not "modern conveniences," and probably in some cases were hardly decent. The condition of the jail in Portsmouth, N.H., in February, 1789, is thus described by a prisoner who made his escape from there by digging through the chimney. His account is interesting in this connection. The paper from which we take it says: "But for fear his quitting his lodgings in so abrupt a manner might lay him open to censure, he wrote the following on the wall:—

"The reason of my going is because I have no fire to comfort myself with, and very little provision. So I am sure, if I was to stay any longer I should perish to death. Look at that bed there! Do you think it fit for any person to lie on?

"If you are well, I am well;

Mend the chimney, and all's well!

"To the gentlemen and officers of Portsmouth from your humble servant,

"William Fall.

"N.B. I am very sorry that I did not think of this before, for if I had, your people should not have had the pleasure of seeing me take the lashes."

The whipping-post and stocks were discontinued in Massachusetts early in the present century. On the 15th of January, 1801, one Hawkins stood an hour in the pillory in Court Street (now Washington Street), Salem, and had his ear cropped for the crime of forgery, pursuant to the sentence of the Supreme Court.

It would be easy to multiply cases showing the old methods of dealing with criminals; but we think we have cited enough for our readers to be able to form some judgment as to the desirability of reviving the old and degrading systems, even if it could be done. It does seem sometimes that there are brutes in the shape of men whose cruelty, especially in the case of crimes against women, makes them deserving of the worst punishment that could be inflicted for the protection of society; but for the general run of such comparatively light offences as petty larceny, etc., beating and branding with hot irons must be considered barbarous in the extreme, and more after the manner of savages than Christians. We always thought that the beating of scholars—a practice once very common in schools—for such trifling offences as whispering and looking off the book, was a gross outrage, and the parent knowing and allowing it was in our opinion as guilty as the schoolmaster. Of course we will not deny that teachers did, then as now, have a great deal to put up with from saucy, "good-for-nothing" boys, to whom the rod could not well be spared; but we do not allude to such cases. We knew a master whose delight, apparently, was pounding and beating little boys,—he did not touch the large ones. And yet he was generally considered a first-rate teacher. Parents upheld him in anything he chose to do with the boys, and if they complained at home, they were told that it must have been their fault to be punished at all. This man every morning took the Bible in one hand and his rattan in the other and walked backward and forward on the floor in front of the desks while the boys read aloud, each boy reading two or three verses; and woe be to any boy who made a mistake, such as mispronouncing a word! Although he might never have been instructed as to its pronunciation, he was at once pounded on the head or rapped over the knuckles. Of course he never forgot that particular word. And this teacher was called only "strict"! If ever a man deserved the pillory, it was that teacher.

Possibly some of our readers may think that there is another side to this story; for the benefit of such we give some lines from the "Salem Gazette," Feb. 6, 1824.

From the Connecticut Centinel.

THE SCHOOLMASTER'S SOLILOQUY.

To whip, or not to whip?—that is the question.

Whether 'tis easier in the mind to suffer

The deaf'ning clamor of some fifty urchins,

Or take birch and ferule 'gainst the rebels,

And by opposing end it? To whip—to flog—

Each day, and by a whip to say we end

The whispering, shuffling, and ceaseless buzzing

Which a school is heir to—'tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished. To whip, to flog,

To whip, and not reform—aye, there's the rub.

For by severity what ills may come,

When we've dismissed and to our lodging gone,

Must give us pain. There's the respect

That makes the patience of a teacher's life.

For who would bear the thousand plagues of a school,—

The girlish giggle, the tyro's awkwardness,

The pigmy pedant's vanity, the mischief,

The sneer, the laugh, the pouting insolence,

With all the hum-drum clatter of a school,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare hickory? Who would willing bear

To groan and sweat under a noisy life,

But that the dread of something after school

(That hour of rumor, from whose slanderous tongue

Few Tutors e'er are free) puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear these lesser ills,

Than fly to those of greater magnitude.

Thus error does make cowards of us all;

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied over with undue clemency,

And pedagogues of great pith and spirit,

With this regard their firmness turn away,

And lose the name of government.

We here record a curious affair which took place in the State of Georgia in the year 1811. At the Superior Court at Milledgeville a Mrs. Palmer, who, the account states, "seems to have been rather glib of the tongue, was indicted, tried, convicted, and, in pursuance of the sentence of the Court, was punished by being publicly ducked in the Oconee River for—scolding." This, we are told, was the first instance of the kind that had ever occurred in that State, and "numerous spectators attended the execution of the sentence." A paper copying this account says that the "crime is old, but the punishment is new," and that "in the good old days of our Ancestors, when an unfortunate woman was accused of Witchcraft she was tied neck and heels and thrown into a pond of Water: if she drowned, it was agreed that she was no witch; if she swam, she was immediately tied to a stake and burnt alive. But who ever heard that our pious ancestors ducked women for scolding?" This writer is much mistaken; for it is well known that in England (and perhaps in this country in early times) the "ducking-stool" was resorted to for punishing "scolds." This was before the days of "women's rights," for there is no record of any man having been punished in this way.

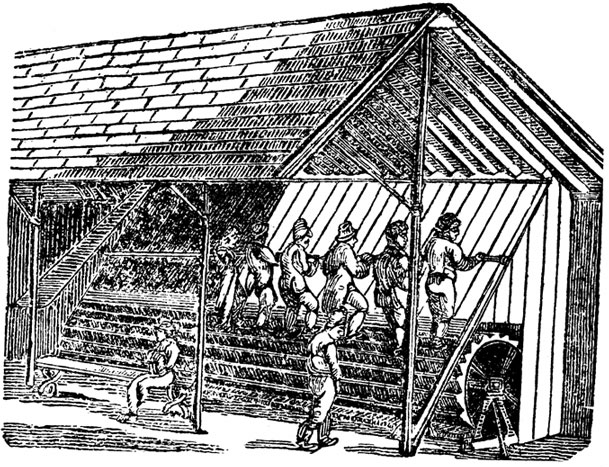

It is said that the ducking-stool was used in Virginia at one time. Thomas Hartley writes from there to Governor Endicott of Massachusetts in 1634, giving an account of the punishing a woman "who by the violence of her tongue had made her house and neighborhood uncomfortable." She was ducked five times before she repented; "then cried piteously, 'Let me go! let me go! by God's help I'll sin so no more.' They then drew back ye Machine, untied ye Ropes, and let her walk home in her wetted Clothes a hopefully penitent woman." In the "American Historical Record," vol. i., will be found a very interesting account of this singular affair, with an engraving of the "ducking-stool." Bishop Meade, in his "Old Churches," etc., says there was a law in Virginia against scolds and slanderers, and gives an instance of a woman ordered to be ducked three times from a vessel lying in James River. There must have been very severe practices in Virginia in the early days, according to Bishop Meade. We refer persons especially interested in this subject to Hone's "Day Book and Table Book," or Chambers's "Book of Days," both English publications, for a full account of the ducking-stool and scold's bridle, formerly used in England for the punishment of scolding women. It is not pleasant to think that such a shameful practice was ever resorted to, but it appears to be well authenticated. We cannot, however, read English history, or any other history, without finding a vast number of disagreeable facts which we are obliged to believe. Some things, too, have occurred in our own country that we should like to forget.

All over the country we are nowadays troubled with "strikes." Such "irregularities" must have been treated in a different spirit half a century ago from what they are now. In these days the "strikers" attempt to dictate terms, and in some cases succeed; although as a general thing they get the worst of the struggle. The method of dealing with such matters fifty years ago is briefly set forth in the "Salem Observer," March 29, 1829. It says: "Turn-out in New York. There has been a turn-out for higher wages among the laborers in the city of New York. Several of the ring-leaders have been arrested and ordered to give heavy bonds for their appearance at Court." In September, 1827, some sailors struck in Boston for higher wages, formed a procession, and marched through the city, making considerable noise with their cheers, etc. They issued the following proclamation, which was read by the leader now and then, and responded to with loud cheers: "Attention! We, the blue Jackets now in the city of Boston, agree that we will not ship for less than $15 a month, and that we will punish any one who shall ship for less in such way as we think proper, and strip the vessel [which he ships in]. What say you?" At the Common they were met by a militia company, who charged upon them; some men of both sides were knocked down, but no lives were lost or blood shed. In the afternoon the sailors were out again with drum and fife. The paper from which we obtain this information says that they probably would not get any advance, as it is assured by a shipper that he found no difficulty in procuring crews at the customary wages. Probably it was not intended that the military should do more than endeavor to keep order.

It is rather surprising that there should have been no conviction for felony in the County of Essex from 1692, when the witches were tried, until 1771,—a period of seventy-nine years. It would so appear, however, from the following extract from the "Essex Gazette," Nov. 12, 1771:—

Laſt Wedneſday Morning the Trial of Bryan Sheehen for committing a Rape on the Body of Mrs. Abial Hollowell, Wife of Mr. Benjamin Hollowell, of Marblehead, in September laſt, came on before the Superior Court of Judicature, at the Court-Houſe in this Town. The Trial laſted from between nine and ten o'Clock A.M. till three in the Afternoon, when the Jury withdrew, and in about one Hour brought in their Verdict, GUILTY. Mrs. Hollowell's Teſtimony againſt the Priſoner was fully corroborated by the Phyſician who attended her, and by the People who were in the Houſe, at and after the Perpetration of the Crime; by which the Guilt and Barbarity of the Priſoner was ſo fully demonſtrated, that the Verdict of the Jury has given univerſal Satisfaction.

This Bryan Sheehen (who has not yet received his Sentence) is the firſt Perſon, as far as we can learn, that has been convicted of Felony, in this large County, ſince the memorable Year 1692, commonly called Witch-Time.

From the "Boston Post-Boy," February, 1763.

BOSTON, January 31.

At the Superiour Court held at Charleſtown laſt Week, Samuel Bacon of Bedford, and Meriam Fitch, Wife of Benjamin Fitch of ſaid Bedford, were convicted of being notorious Cheats, and of having by Fraud, Craft and Deceit, poſſeſs'd themſelves of Fifteen Hundred Johannes, the property of a third Perſon; were Sentenced to be each of them ſet in the Pillory one Hour, with a Paper on each of their Breaſts with the Words a CHEAT wrote in Capitals thereon, to ſuffer three Months Impriſonment, and to be bound to their good Behaviour for one Year, and to pay Coſts.

From the "Massachusetts Gazette," May 1, 1786.

On Saturday evening the 22d ult. eight of the priſoners, confined at the Caſtle, broke from their confinement, and made their eſcape to the main. The day following five of them were taken in a barn at Dorcheſter, and immediately re-conducted to the Caſtle. The enſuing night the three others were apprehended at Sharon, near Stoughton, and were alſo ſent back to their place of confinement.

Richard Squire and John Matthews, the pirates, and Stephen Burroughs, a noted clerical character, were among the priſoners who made their eſcape from the Caſtle, as mentioned above. And on Saturday laſt, we are informed, the eight culprits ſhared among them the benefit of a diſtribution of 700 laſhes.

On Monday evening laſt, a perſon, in paſſing from the Long-Wharf to Dock-Square, was aſſaulted and knocked down, by a ſingle villain, who robbed him of a box, containing a coat, two waiſtcoats, a pair of corduroy breeches, a piece of calico, in which was wrapped up three watches, and a letter containing money.

On Thurſday laſt, at noon, ſeven fellows received the diſcipline of the poſt, in this town.

Curious list of punishments in the early days of New England. From "Salem Gazette," May 4, 1784.

The following (taken from a Boſton paper of laſt week) is a collection of a few of the many curious puniſhments, inflicted for a variety of offences, among the old records of this Commonwealth.

Between 1630 and 1650.

Sir Richard Saltonſtale fined four buſhels of malt for his abſence from court.

William Almy fined for taking away Mr. Glover's canoe without leave.

Joſias Plaſtoree ſhall (for ſtealing four baſkets of corn from the Indians) return them eight baſkets again, be fined 5l. and hereafter to be called by the name of Joſias, and not Mr. as formerly he uſed to be.

Joyce Bradwick ſhall give unto Alexander Beeks, 20ſ. for promiſing him marriage without her friends' conſent, and now refuſing to perform the ſame.

William James, for incontinency, was ſentenced to be ſet in the bilboes at Boſton and Salem, and bound in 20l.

Thomas Petet, for ſuſpicion of ſlander, idleneſs and ſtubbornneſs, is to be ſeverely whipt and kept in hold.

John Smith, of Medford, for ſwearing, being penitent, was ſet in bilboes.

Richard Turner, for being notoriouſly drunk, was fined 2l.

John Hoggs, for ſwearing God's foot, curſing his ſervant, wiſhing "a pox of God take you," was fined 5l.

Richard Ibrook, for tempting two or more maids to uncleanneſs, was fined 5l. to the country, and 20ſ. a piece to the two maids.

Thomas Makepeace, becauſe of his novel diſpoſition, was informed we were weary of him, unleſs he reformed.

Edward Palmer, for his extortion, taking 33ſ. 7d. for the plank and woodwork of Boſton ſtocks, is fined 5l. and cenſured to be ſet an hour in the ſtocks.

John White is bound in 10l. to be of good behaviour, and not to come into the company of Bull's wife alone.

Thomas Lechford acknowledging he had overſet himſelf and is ſorry for it, promiſing to attend his calling, and not to meddle with controverſies, was diſmiſſed.

Sarah Hales was cenſured for her miſcarriage to be carried to the gallows with a rope about her neck, and to ſit upon the ladder, the rope end flung over the gallows, and after to be baniſhed.

Wholesale sentences of death in London, in 1820.

At the October session of the Old Bailey, London, sentence of death was passed on thirty-seven persons, four of whom were females. Four were condemned for passing counterfeit notes, eleven for highway robberies, two for burglary, 11 for stealing in dwelling houses, 1 for horse-stealing, 2 for sacrilege, &c.

From the "Salem Mercury," July 28, 1788.

The following Extraordinary Occurrence is extracted from the European Magazine for 1787.

SAMUEL BURT, convicted of forgery a few ſeſſions ſince, was put to the bar, and informed that his Majeſty, in his royal clemency, had been graciouſly pleaſed to extend his mercy to him on condition that he ſhould be tranſported during his natural life. The priſoner bowed reſpectfully to the Court, and immediately addreſſed the Recorder with his "most humble and unfeigned thanks, for the kindneſs and humanity of the Recorder, the Sheriffs, and other gentlemen who had intereſted themſelves in his favour, and who had ſo effectually repreſented his unhappy caſe to the throne, that his Majeſty, whoſe humanity could only be equalled by his love of virtue, had extended his mercy; but however flattering the proſpect of preſerving life might be to a man in a different ſituation; yet that he, now he was ſunk and degraded in ſociety, was totally inſenſible of the bleſſing. Life was no longer an object with him, as it was utterly impoſſible that he could be joined in union with the perſon who was dearer to him than life itſelf. Under ſuch circumſtances, although he was truly ſenſible of his Majeſty's goodneſs and clemency, yet he muſt poſitively decline the terms offered him; preferring death to the prolongation of a life which could not be otherwiſe than truly miſerable." The whole Court was aſtoniſhed at his addreſs; and after conſultation, Mr. Recorder remanded the priſoner back to the jail, to be brought up again the firſt day of next ſeſſion.

The pillory appears to have been in use in Boston as lately as 1803; for we find in the "Chronicle" of that city that in March of that year Robert Pierpont, owner, and H.R. Story, master, of the brigantine "Hannah," for the crime of sinking the vessel at sea, and thus defrauding the underwriters (among whom were Joseph Taylor, Peter C. Brooks, Thomas Amory, David Greene, and Benjamin Bussey), were convicted before the Supreme Judicial Court, and the following sentence imposed: "That they should stand one hour in the Pillory in State Street on two several days, be confined in Prison for the term of two years, and pay Costs of Prosecution." Considering the magnitude of the crime, this was a light sentence. An underwriter in the "Chronicle" says: "It is a transaction exceeding in infamy all that has hitherto appeared in the commerce of our country."

Wholesale execution of pirates in Newport, R.I., in July, 1723.

CAPTURE OF PIRATES.

This year (1723) two Pirate sloops, called the Ranger and the Fortune, committed many piracies on the American Coast, having captured and sunk several vessels.—On the 6th of June, they captured a Virginia sloop, which they plundered and let go, who soon after fell in with his Majesty's Ship Grey Hound, Capt. Solgard, of 20 guns, who on being informed of the piracy, immediately went in pursuit of the Pirates, and on the 10th came up with them about 14 leagues south from the east end of Long Island. They mistaking her for a Merchant ship, immediately gave chase and commenced firing under the black flag.—The Grey Hound succeeded in capturing the Ranger, one of the sloops, after having 7 men wounded, but the other Pirate escaped. The Grey Hound and her prize arrived in the harbor of Newport, and the Pirates, 36 in number, were committed for trial.

Trial of the Pirates.

A Court of Admiralty, for the trial of Pirates, was held at Newport on the 10th, 11th and 12th of July. The Hon. William Dummer, Lt. Governor and Commander in Chief of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, President of the Court.

The thirty-six Pirates taken by Capt. Solgard, were tried, when Charles Harris, who acted as captain, and 25 of his men, were found guilty, and sentenced to suffer death, and 10 men were acquitted on the ground of having been forced into their service.

Execution of the Pirates.

On Friday the 19th of July, the 26 Pirates were taken to a place in Newport, called Bull's Point, (now Gravelly Point,) within the flux and reflux of the sea, and there hanged. The following are their names:—Charles Harris, Thomas Linnicar, Daniel Hyde, Stephen Mundon, Abraham Lacy, Edward Lawson, John Tomkins, Francis Laughton, John Fisgerald, Wm. Studfield, Owen Rice, Wm. Read, Wm. Blades, Tho's Hagget, Peter Cues, Wm. Jones, Edward Eaton, John Brown, James Sprinkly, Joseph Sound, Charles Church, John Waters, Tho's Powell, Joseph Libbey, Thomas Hazel, John Bright.

The Pirates were all young men, most of them were natives of England, Wm. Blades was from Rhode Island and Thomas Powell from Wethersfield, (Conn.); after the execution, their bodies were taken to the north end of Goat Island, and buried on the shore, between high and low water mark.

As this was the most extensive execution of Pirates that ever took place at one time in the Colonies, it was attended by a vast multitude from every part of New England.

From the Salem Observer, Nov. 11, 1843.

Description of "Villains" in the "Boston Post-Boy," Dec. 12, 1763.

Tueſday laſt a Gang of Villains were apprehended at a Houſe in Roxbury, and brought to Town & committed to Goal, they have been concerned in the late Robberies here, and 'tis ſuſpected in ſome of thoſe towards Pennſylvania, for which Reaſon it will be proper to advertiſe their Names, with ſome Deſcription of them, which are as follows, viz.

William Robinſon, a tall ſlim fellow, about 5 Feet 7 inches high, wears a blue Surtout Coat with metal Buttons, and his Hat commonly flopt before, and an old laced Waiſtcoat, has ſhort curled black Hair; when he ſpeaks he ſeems jaw-fallen and very effeminate, is about 35 Years of Age, walks much like a Foot-pad, and has a comely Woman with him whom he calls his Wife.—John Caſſady, a middling ſiz'd Fellow much pock-broken, ſquare-ſhoulder'd, wears a Wig upon the yellow caſt, and has a very guilty Countenance, is about 40 Years of Age, and calls himſelf a Shoe-maker.—John Willſon, a ſhort young Fellow, about 21 Years of Age, wears a blue Surtout Coat, and ſhort black Hair, of a pale Countenance, and calls himself a Sail-maker.—George Sears, a well-ſet Fellow, with a comely Face, black Hair twiſted with a black Ribbon, and ſays he ſerv'd 3 Years to an Attorney in England.

In the "Essex Gazette," Nov. 12, 1771, is the following news from England:—

A Correſpondent expreſſes great Surpriſe and indignation at the Diſproportion of Puniſhments in this Country. He ſays he read in a News paper that two Men were hanged together laſt Month in Kent, one of whom had committed a barbarous Murder on his Wife, and the other had ſtolen three Shillings and Sixpence. In the ſame Paper there followed immediately another Paragraph, that a Woman had been only whipped for ſtealing little Children and burning their Eyes out.

At this day we believe it is the custom of the English authorities to treat all prisoners alike, whatever the charges against them may be. It seems as if they were desirous of degrading men as much as possible. Mr. John Boyle O'Reilly, a poet and gentleman of culture, who was unfortunately a political prisoner, was chained to a wife-murderer. And this the English call "justice,"—as if there could be no difference in offences!

Severe punishment used to be inflicted for the crime of passing counterfeit coin. The "Essex Gazette," April 23, 1771, under news from Newport, April 15, says,—

William Carliſle was convicted of paſſing counterfeit Dollars, and ſentenced to ſtand One Hour in the Pillory, on Little-Reſt Hill, next Friday, to have both Ears cropped, to be branded on both Cheeks with the Letter R, to pay a Fine of One hundred Dollars and Coſt of Proſecution, and to ſtand committed till Sentence performed.

The letter R probably meant "rogue." The same account states that—

"Laſt Wedneſday Evening one Mr. ——, of this Town (Newport), was catched by a Number of Perſons in Diſguiſe, placed on an old Horſe, and paraded through the principal Streets for about an Hour as a Warning to all bad Huſbands."

In the "Massachusetts Gazette," Sept. 8, 1786, we find an account of the Dutch mode of executions.

NEW-JERSEY.

Elizabeth-Town, Aug. 16. The little influence which our preſent mode of executing criminals has in deterring others from the commiſſion of the ſame crimes, ariſes from a want of ſolemnity and terrifick circumſtances on ſuch occaſions. It is not the mere loſs of life which has ſo much a tendency to affect the ſpectator, as the dreadful apparatus, the awful preliminaries, which ought to attend publick executions; whoſe juſtifiable purpoſes is the prevention of crimes, and not the inflicting torment on the criminal. A variety of particulars might be adopted reſpecting the dreſs of the condemned, the ſolemnity of the proceſſion to the place of execution, and the apparatus there, to throw horrour on the ſcene without in reality giving the unhappy victim a more painful exit. The Dutch have a mode of execution which is well calculated to inſpire terror, without putting the ſufferer to extraordinary pain. The criminal is placed on a ſcaffold, oppoſite to the gigantick figure of a woman, with arms extended, filled with ſpikes, or long ſharpened nails, and a dagger pointed from her breaſt, ſhe is gradually moved towards him by machinery for the purpoſe, till he gets within her embrace, when her arms encircle him, and the dagger is preſſed through his heart. This is vulgarly called among them, kiſſing the Yſſrow, or woman, and excites more terror in the breaſts of the populace than any other mode of puniſhment.

Inhabitants of Boston severely punished (on paper) in April, 1774, for destruction of the tea.

A Curious Historical Item. In a recent English Chronological work, under the article of "Tea," we found the following brief notice of the American Revolution: "Tea destroyed at Boston by the inhabitants, 1773, in abhorrence of English Taxes; for which they were severely punished by the English Parliament, in April, 1774."

Salem Observer, April 28, 1827.

Sentences of death for robbery, May 6, 1788.

The Mulatto who, ſome time ſince, robbed Mr. Bacon, on the Cambridge road, was, at the late term of the Supreme Court at Concord, convicted of the crime, and had ſentence of death pronounced againſt him.

Thurſday next is the day appointed for the execution of the two Taylors, for the robbery of Mr. Cunningham, on Boſton-Neck.

Captain Phillips, of the British army, whipped in New York in 1784.

PHILADELPHIA, February 4, 1784.

On Saturday laſt, was whipped at the cart's tail, for robbery, one of George the Third's pretty ſubjects. This fellow, who now goes by the name of Captain Phillips, under his good friend Sir Harry Clinton, learned ſuch a knack of thieving while he commanded a whale-boat along this coaſt, under his good maſter, that now, having loſt his protection, he and a number more of thoſe lads called Loyaliſts are ſwarming amongſt us, and have ſet up buſineſs in a ſmall way; and though many of them may not chooſe to ſteal themſelves, yet, by harbouring and encouraging others, may do much miſchief to the good inhabitants of theſe ſtates.

Salem Gazette.

Sentences at the Supreme Court.

BOSTON, March 22, 1784.

At the Supreme Judicial Court, lately held here, the following perſons were arraigned, viz.

Thomas Haſtings, indicted for ſelling corrupt ſwine's fleſh, was found guilty.—He was ſentenced to pay a fine of twelve pounds for the uſe of the Commonwealth, recognize himſelf as principal in the ſum of thirty pounds, with ſufficient ſurety or ſureties in the like ſum, for his keeping the peace and being of good behaviour for the term of one year, pay coſts of proſecution, and ſtand committed till ſentence be performed.

John Boyd, for ſtealing, pled guilty:—ſentenced to pay to the perſon injured, treble the value of the goods ſtolen, receive 20 ſtripes at the public whipping poſt, ſit on the gallows one hour with a rope about his neck, pay coſts of prosecution, and ſtand committed till ſentence be performed.—He was, upon another indictment for theft, ſentenced to pay treble damages, whipped 15 ſtripes, and pay coſts of proſecution.—Upon declaring himſelf unable to pay damages, he was for the firſt offence ſentenced to be ſold for 9 months, and for the ſecond, 2 months.

Lewis Humphries, for ſtealing, pled guilty:—ſentenced to pay treble damages, receive 20 ſtripes, ſit on the gallows one hour with a rope about his neck, pay coſts of proſecution, and ſtand committed till ſentence be performed.—Upon declaring himſelf unable to pay damages, was ſentenced to be ſold for the term of 5 years.

William Padley, for an aſſault upon his wife, with an intent to kill her, was tried, found guilty, and ſentenced to ſit on the gallows one hour, there to receive 30 ſtripes, pay coſts of proſecution, and ſtand committed till ſentence be performed.

Sentences by the Supreme Judicial Court at Salem, Nov. 18, 1786.

At the Supreme Judicial Court, holden in this town, for the county of Eſſex, which adjourned on Thurſday laſt, ſeveral perſons, criminally indicted, were convicted and ſeverally ſentenced. Iſaac Coombs, an Indian, was found guilty, at laſt June term, at Ipſwich, of murdering his wife; at which time a motion was made to the Court, in arreſt of judgment, on which the Court ſuſpended giving judgment thereon until this term; but the ſaid motion being overruled, the Court gave judgment of death againſt him.

Beſides the ſentence of the Indian, as above, Thomas Kendry, for breaking into the ſtore of Iſrael Bartlet, and ſtealing ſundry goods, was ſentenced, on his confeſſion, to pay ſaid Bartlet £33-9-6, to ſit on the gallows one hour with a rope about his neck, to be whipped 30 ſtripes, and confined to hard labour on Caſtle-iſland two years.

Thomas Atwood & John Ranſum, for breaking open the ſtore of Knott Pedrick, and ſtealing dry fiſh, were each ſentenced to pay ſaid Pedrick £40-5-0, to ſit one hour on the gallows, be whipped 36 ſtripes, and confined to labour on Caſtle-iſland 3 years.

John Smith, for ſtealing goods from Abner Perkins, was ſentenced to pay ſaid Perkins £18-4-0, and be whipped 25 ſtripes.

The ſame John Smith, for breaking open a ſloop, and ſtealing goods of John Brooks, was ſentenced to pay ſaid Brooks £16-8-0, to ſit one hour on the gallows, be whipped 30 ſtripes, and confined 18 months on Caſtle-iſland.

John Scudder, for ſtealing from Eli Gale, was ſentenced to pay ſaid Gale £5-2-0, or if unable to pay, to be diſpoſed of by him, in ſervice, to any perſon, for 2 months.

Joseph Ballard, for ſtealing a horſe from Thomas Dodge, was ſentenced to pay £30, be whipped 20 ſtripes, pay coſts, &c. and, if unable to pay, that ſaid Dodge may diſpoſe of him in ſervice to any perſon for two years.

Calvin Newhall was indicted for aſſaulting Deborah Sarker, a negro woman, with intent to commit a rape upon her. He pleaded not guilty; and the jury found him guilty of the aſſault, but whether with an intent to raviſh they could not agree; whereupon the Attorney General would no further proſecute for ſaid intent to raviſh; and the Court ordered that ſaid Calvin ſhould be whipped 10 ſtripes, and recognize in £60, with ſufficient ſurety in a like ſum, to be of good behaviour for 3 months, and pay coſts.

Punishment in 1644 for criticising the preacher and the music, and for sleeping in "meeting."

The Hon. Wm. D. Northend, in a very interesting and valuable address before the Essex Bar Association, Dec. 8, 1885, mentions the following among other cases taken from the Essex County Court Records:—

"In 1644 William Hewes and John his son, for terming such as sing in the congregation fools, and William Hewes also for charging Reverend Mr. Corbitt with falsehood in his doctrine, were ordered to pay a fine of fifty shillings each, and to make humble confession in a public meeting at Lynn."

William Hewes and his son were probably only criticising the music and the preaching in the "meeting-house." If people nowadays were fined for similar offences, the county would grow so rich that there would be no necessity for the present heavy tax.

"In 1643 Roger Scott, for repeated sleeping in meeting on the Lord's Day, and for striking the person who waked him, was, at Salem, sentenced to be severely whipped."

It must be borne in mind that people in those days were not allowed to stay at home on the Lord's Day and do their sleeping there. Staying at home on Sunday is a modern innovation.

From the Massachusetts Colony Records, quoted by Mr. Northend, we learn that in March, 1761, Sir Christopher Gardner, who had passed much of his time "with roystering Morton of Merry Mount," and who was living with a lady he called his cousin, upon receipt by the Governor of information of two wives in England "whom he has carelessly left behind," after a long pursuit was captured and sent back to England.

It would seem, then, that there must have been, judging from this example, in "high places" some "indiscretions" and "unpleasant" gossip early in our history.

Mr. Northend finds that at "the same date one Nich. Knopp, for pretending to cure scurvy by water of no value, which he sold at a very dear rate, was ordered to pay a fine of five pounds or be whipped, and made liable to an action by any person to whom he had sold the water."

How would such a decree work in our day, if applied to the makers or venders of all the "water of no value" which is advertised on the fences and barns alongside of our railroads and highways?

Mr. Northend, speaking of the severity of the early laws, says:—

"The criminal laws were taken principally from the Mosaic code; and although many of them at the present day seem harsh and cruel, yet as a whole they were very much milder than the criminal laws of England at the time, and the number of capital offences was greatly reduced."

CURIOUS PUNISHMENTS IN SCHOOLS.

In some of the old schools in Salem (no doubt it was the same in other places) the teachers whose business it was to teach youths the "three R's,"—Reading, 'Riting, and 'Rithmetic,—were too apt to be occupied, as we have been told, in scolding, devising or practising some mode of punishment. We remember hearing of a school where the master kept a long cane pole (something like a fishing-rod) which he used for the purpose of reaching boys who needed correction; on account of the length of the pole he was enabled to do business without leaving his seat. It was never suspected at the time how lazy this master was.

Another teacher kept for use as a punishment a common walnut, which when occasion required he first put into the mouth of a colored boy, and after it had remained there for five minutes or so, it was taken out and put into the mouth of the white boy, who was thus to be punished by holding it in his mouth for a certain length of time. This same teacher had a round smooth stone, weighing perhaps ten or fifteen pounds, which very small boys were required to hold in their arms for some time, and stand up straight before the whole school. These with a good rattan and a cowhide furnished this master's equipment for teaching.

There was another master who had what he called "the mansion of misery," which was simply a line drawn with chalk on the floor in front of his desk, where for trifling offences such as whispering, etc., scholars were required to "toe the mark," standing perfectly still and upright for a long time. This was often to a little boy painful enough. This master had a stock of cowhides and rattans besides.

Another teacher, a woman, had the floor of the school-room kept very clean; consequently no boys were allowed to come in at all with heavy boots, and the other children in wet weather were compelled to remove their boots and shoes and put on slippers before entrance. If any of the scholars were too small to take off and put on their own boots they were punished by being "blindfolded" and stood upon a cricket in the middle of the floor. Apparently the worst offence scholars could be guilty of was to bring in mud or wet upon the polished floor of the school-room. At this school one very small boy who wore high boots, but who was unable to take them off without assistance, having been punished for his "stubbornness," was taken away from the school by his parents, who resented such an act of injustice and oppression. The "school-marm," however, said she would rather lose all her scholars than have any mud or wet upon her floor.

These cases are simply curious. It may be doubted whether we can in this country show anything so bad as the record furnished by Dickens in describing some of the schools of England.

THE BRANK.

An instrument of punishment formerly much used in England, but never, we think, introduced into this country, called the "brank," or "scold's bridle," or "gossip's bridle," is thus described by Mr. L. Jewitt, F.S.A., in Mr. William Andrews's "Book of Oddities,"—a very interesting and instructive book recently published in London:—

"It consisted of a kind of crown or framework of iron, which was locked upon the head, and was armed in front with a gag, a plate, or a sharp cutting knife or point, which was placed in the poor woman's mouth so as to prevent her moving her tongue, or it was so placed that if she moved it or attempted to speak, the tongue was cut in a most frightful manner. With this cage upon her head, and with the gag firmly pressed and locked against her tongue, the miserable creature, whose sole offence, perhaps, was that she had raised her voice in defence of her social rights against a brutal and besotted husband, or had spoken honest truth of some one high in office in the town, was paraded through the streets, led by a chain held in the hand of the bellman, the beadle, or the constable, or, chained to the pillory, the whipping-post, or market-cross, was subjected to every conceivable insult and degradation, without even the power left her of asking for mercy or of promising amendment for the future; and when the punishment was over, she was turned out from the town hall (or other place where the brutal punishment had been inflicted), maimed, disfigured, faint, and degraded, to be the subject of comment and jeering amongst her neighbors, and to be reviled by her persecutors."

Mr. Andrews adds that the use of the brank was not sanctioned by law, but was altogether illegal; and he concludes his remarks on the subject by saying that "to everybody it must be a matter of deep regret that the instrument should ever have been used at all."

Dr. Henry Heginbotham, of Stockport, England, says in speaking of the brank preserved in that town: "There is no evidence of its having been actually used for many years; but there is testimony to the fact that within the last forty years the brank was brought to a termagant market-woman, who was effectually silenced by its threatened application."

It is hard for those of us who live in New England to-day to believe that such cruelties were ever practised in a Christian land; but the evidence is too conclusive to admit of doubt. Mr. Andrews, in the book referred to, gives engravings of a dozen or more different kinds of branks and bridles which can now be seen in England and Scotland. At Congleton, Cheshire, a woman for scolding and abusing the town officers had the "town bridle" put upon her, and was led through every street in the town, as lately as the year 1824.

It is said that Chaucer wrote these lines:

"But for my daughter Julian,

I would she were well bolted with a Bridle,

That leaves her work to play the clack,

And lets her wheel stand idle;

For it serves not for she-ministers,

Farriers nor Furriers,

Cobblers nor Button-makers,

To descant on the Bible."

Mr. Andrews has confined his account of curious punishments mainly to England and Scotland. Our Puritan ancestors must, we think, have seen some of the instruments of torture here described, and perhaps some of our great-great, etc., grandmothers may have been "ducked" or "silenced by a brank" many years before the sailing of the "Mayflower" or the "Lyon" or the "Angel Gabriel."

It was once the custom in New England for a sermon to be preached before the prisoner upon the day of his execution. In the "Massachusetts Gazette," Dec. 26, 1786, is the following notice:—

Salem, Dec. 23. Thurſday laſt, being the day appointed for the execution of Iſaac Coombs, an Indian, with whoſe crime and ſentence the publick have before been made acquainted, the unfortunate criminal was in the forenoon conducted to the Tabernacle, where a Sermon, which we are told was well adapted to the melancholy occaſion, was preached by the Rev. Mr. Spalding, from Luke xviii. 13,—"God be merciful to me a ſinner!" After which he was returned to the priſon. Between the hours of 2 and 3 in the afternoon, he was guarded to the place of execution by a company of 40 volunteers (conſiſting principally of the members of the Artillery Company lately formed in this town, and commanded by Captain Zadock Buffinton) under the direction of the proper civil officers. The Rev. Mr. Hopkins prayed at the gallows; and at 3 o'clock the cart was led off, and the unhappy ſufferer made the expiation which the law required for his horrid and unnatural crime.

His behaviour, through the whole, was firm, but decent, penitent and devotional.

This is the only execution which has taken place in the county of Eſſex for near 15 years, and but the ſecond ſince about the cloſe of the laſt century. The concourſe of people was conſequently great; and the general decorum which was obſerved, evinced their ſympathy for a ſuffering individual of the ſpecies.

The conduct of the military corps was highly applauded.

On the way to execution the following paper was delivered to the Rev. Mr. Bentley, by one of the officers, with a requeſt from Iſaac, that he would read it publickly at the place of execution, at the time he ſhould ſignify to him; accordingly, when the ſheriff told the criminal his time was expired, as the laſt thing, he made the motion, and it was read to the people. As it is ſo contradictory to the declaration he made before of himſelf, we have printed it verbatim as it is written, to avoid the charge of any alteration.

"I Who has ben Called by the name of Iſaac Cumbs Being Now Called to the place of Execution in the 39th year of my age, I Declare I was born at South hampton Long Iſland and am a Native of the ſaid South hampton and my Right Name is John Peters and Leaving the ſaid South hampton about 14 years ago, and comeing to St. Mertains Vineyard am Ben a traveller Everſince till I have Now arrived to this unhappy Place of Execution My advice is to all Spectators to Refrain from lying Stealing and all ſuchlike things But in particular Not to Break the Sabbath of the Lord or Game at Cerds or get Drunk as I have Don. this is My advice and more in particular to mixt coulard people and youths of Every Kind. May the Bleſſing of god Deſend upon you all Amen."

In the "Essex Gazette," Jan. 15, 1771, is an advertisement of a poem upon an execution.

To be sold at the Printing-Office, Salem.

A POEM on the Execution of

William Shaw, at Springfield, December 13, 1770, for the Murder of Edward East, in Springfield Gaol.

We have seen an account of an execution where a sermon was preached at the prisoner's request.

BOSTON COMMON AS A PLACE OF EXECUTION.

Boston Common was formerly often used for such a purpose. Quakers were hanged there in the middle of the seventeenth century, and we find in the "Salem Mercury" for Tuesday, Nov. 27, 1787, that the previous Thursday one John Sheehan was executed for burglary in this noted locality. Sheehan was a native of Cork in Ireland. With its cows and its executions, the Common must have presented a somewhat different appearance in those days from what it does at this time.

British convicts shipped to America in 1788.

Laſt week arrived at Fiſher's Iſland, the brig Nancy, belonging to this port, Capt. Robert W—— (a half-pay Britiſh officer) maſter, and landed his cargo, conſiſting of 140 convicts, taken out of the Britiſh jails. Capt. W. it is ſaid, received 5l. ſterling a head from government for this job; and, we hear, he is diſtributing them about the country. Stand to it, houſes, ſtores, &c., theſe gentry are acquainted with the buſineſs. Quere, whether a ſuit of T—— and F—— ſhould not be provided for Capt. W. as a ſuitable compliment for this piece of ſervice done his country?

Salem Mercury, July 15, 1788.

From the "Salem Gazette," 1784.

July 30. During the long reign of Queen Elizabeth, it does not appear on record, that forty perſons ſuffered death for crimes againſt the community, treaſon only excepted.

BOSTON, September 16, 1784.

At the Supreme Court held here on Thurſday laſt, Direck Grout was tried for Burglary, and found guilty: ſentence has not yet been paſſed upon him.

The following priſoners were also tried last week for various thefts, found guilty, and received ſentence, viz.

Cornelius Arie, to be whipt 25 ſtripes, and ſet one hour on the gallows.

Thomas Joice, to be whipt 25 ſtripes, and branded.

William Scott, to be whipt 25 ſtripes, and ſet one hour on the gallows.

John Goodbread, and Edward Cooper, 15 ſtripes each.

James Campbell, to be whipt 30 ſtripes, and ſet one hour on the gallows.

Michael Tool, to be whipt 20 ſtripes.

Three notorious villains yet remain to be tried for burglary, and ſeveral others for theft.

BOSTON, September 27.

Thurſday laſt ten notorious villains received publick whipping, after which three of them were eſcorted, with halters round their necks, to the gallows, on which they ſat one hour. They are again committed for coſts, &c.

"Massachusetts Gazette," 1786.

Johnſon Green was executed, on Thurſday laſt, at Worceſter, for burglary. A greater thief and burglar was perhaps never hanged in this country.

From "Massachusetts Centinel," Oct. 6, 1786.

BACKS "DRESS'D."

HARTFORD, October 2.

On Wedneſday laſt, David Stillman, John Hawley and Thomas Gibbs were committed to jail in this city, for counterfeiting and paſſing publick ſecurities; and on Thurſday laſt, Jonathan Denſmore, of Eaſt-Hartford, was committed for ſtealing a horſe. Stillman and Hawley belong to the county of Hampſhire, ſtate of Maſſachuſetts. They are now in a fair way to have their grievances (and backs) dreſs'd and re-dreſs'd.

From "Massachusetts Gazette," May 15, 1786.

NEW-YORK, May 6.

Extract of a letter from Washington (North-Carolina), March 27.

"On Thurſday laſt made his appearance in this town, a certain John Hamlen, who, in the late war, left the ſtate of Maryland, and joined the enemies of America. After joining them, he fitted out a galley, and cruiſed in the Delaware and Cheſapeak, where he was very ſucceſsful in capturing a number of American veſſels. He was very fond of exerciſing every ſpecies of cruelty on thoſe unhappy people who fell into his hands; among other things, he took great delight in cutting off the ears of ſome, and noſes of others. Unluckily for him he was known by ſome honeſt Jack Tars, belonging to veſſels in this harbour, who, in the time of the war, had been made priſoners by him; theſe honeſt fellows very kindly furniſhed him with a coat of Tar and Feathers; and that he might not in a ſhort time forget them, they took off one of his ears; they then kindly ſhewed him the way out of town, without doing him any further injury.—It is ſupposed he will bend his courſe for Newbern, and endeavour to take a paſſage in some veſſel bound to the northern ſtates."

FROM THE AUGUSTA CHRONICLE.

A GEORGIA SHREW.

"Why, sirs, I trust I may have leave to speak,

And speak I will; I am no child, no babe:

Your betters have endur'd me say my mind;

And if you cannot, best you stop your ears."

The Grand Jury of Burke have presented Mary Cammell as a common scold and disturber of the peaceable inhabitants of that county.[1] We do not know the penalty, or if there be any attached to the offence of scolding: but for the information of our Burke neighbours, we would inform them that the late lamented and distinguished Judge Early decided, some years since, when a modern Xantippe was brought before him, that she should undergo the punishment of lustration, by immersion three several times in the Oconee. Accordingly she was confined to the tail of a cart, and, accompanied by the hooting of the mob, conducted to the river, where she was publickly ducked, in conformity with the sentence of the court. Should this punishment be awarded Mary Cammell, we hope, however, it may be attended with a more salutary effect than in the case we have just alluded to—the unruly subject of which, each time as she arose from the watery element, impiously exclaimed, with a ludicrous gravity of countenance, "glory to G—d."

Boston Palladium, 1819.

[1]

She must have been an extraordinary scold to have disturbed a large county, where the houses are perhaps a half mile apart.

Criminals after a whipping sent to the Castle to make nails. From "Salem Mercury," Nov. 25, 1786.

Four convicts, doomed by the Superiour Court, at their late ſeſſion here, to the uſeful branch of nail making at the Caſtle, yeſterday morning took their departure hence, to enter on their new employment, having, with others, previouſly received the diſcipline of the poſt.

A REVEREND FORGER.

The "Providence Gazette" is our authority for the following obituary notice:—

Died in March, 1805, in Wayne County, N.C., Rev. Thomas Hines, an itinerant preacher. A Newbern paper says: "In the saddle-bags of this servant of God and Mammon were found his Bible and a complete apparatus for the stamping and milling of Dollars."

THE SUPREME JUDICIAL COURT

Was held at Ipſwich on Tueſday laſt. At this Court the noted Josiah Abbot was found guilty of knowingly paſſing a forged and altered State Note, and was ſentenced to pay a fine of 40l. in 20 days; if not then paid, to be ſet in the pillory.—[The penalty of ſuch an offence againſt the United States is DEATH.]

The ſame perſon was found guilty of a fraud, in ſtealing a ſummons, after it had been left by an officer, by reaſon of which he recovered a judgment by default, and was ſentenced to pay a fine of 15l. in 20 days; if not then paid, to be whipped.

Salem Gazette, June 25, 1793.

In a paper of 1819 is mentioned the singular case of a man literally condemned "to eat his own words."

INCREDIBLE PUNISHMENT.

"A great book is a great evil," said an ancient writer,—an axiom which an unfortunate Russian author felt to his cost. "Whilst I was at Moscow," says a pleasant traveller, "a quarto volume was published in favor of the liberties of the people,—a singular subject when we consider the place where the book was printed. In this work the iniquitous venality of the public functionaries, and even the conduct of the sovereign, was scrutinized and censured with great freedom. Such a book, and in such a country, naturally attracted general notice, and the offender was taken into custody. After being tried in a very summary way, his production was determined to be a libel, and the writer was condemned to eat his own words. The singularity of such a sentence induced me to see it put into execution. A scaffold was erected in one of the most public streets of the city; the imperial provost, the magistrates, the physicians and surgeons of the Czar attended; the book was separated from its binding, the margin cut off, and every leaf rolled up like a lottery ticket when taken out of the wheel at Guildhall. The author was then served with them leaf by leaf by the provost, who put them into his mouth, to the no small diversion of the spectators; he was obliged to swallow this unpalatable food on pain of the knout,—in Russia more dreadful than death. As soon as the medical gentlemen were of opinion that he had received into his stomach as much at the time as was consistent with his safety, the transgressor was sent back to prison, and the business resumed the two following days. After three very hearty but unpleasant meals, I am convinced by ocular proof that every leaf of the book was actually swallowed."

Lon. Pa.

Boston Palladium.

Here is a clever mode of punishing a wife-beater without the aid of counsel:—

A woman in New-York, who had been beaten by her husband, finding him fast asleep, sewed him up in the bed-clothes, and in that situation thrashed him soundly.

Salem Observer, April 24, 1827.

Conviction of a common scold, Sept. 11, 1821; sentence not reported.

Common Scold.—Catharine Fields was indicted and convicted for being a common ſcold. The trial was exceſſively amuſing, from the variety of teſtimony and the diverſified manner in which this Xantippe purſued her virulent propenſities. "Ruder than March wind, ſhe blew a hurricane;" and it was given in evidence that after having ſcolded the family individually, the bipeds and quadrupeds, the neighbours, hogs, poultry, and geeſe, ſhe would throw the window open at night to ſcold the watchmen. Her countenance was an index to her temper,—ſharp, peaked, ſallow, and ſmall eyes. To be ſentenced on Saturday week.—Nat. Adv.

Women Gossips.—Among the many ordinances promulgated at St. Helena in 1709, we find the following:—

Whereas several idle, gossiping women make it their business to go from house [to house] about the island, inventing and spreading false and scandalous reports of the good people thereof, and thereby sow discord and debate among neighbors, and often between men and their wives, to the great grief and trouble of all good and quiet people, and to the utter extinguishing of all friendship, amity, and good neighborhood: for the punishment and suppression whereof, and to the intent that all strife may be ended, charity revived, and friendship continued,—we do order that, if any woman, from henceforward, shall be convicted of tale bearing, mischief making, scolding, drunkenness, or any other notorious vice, that they shall be punished by ducking, or whipping, or such other punishment as their crimes or transgressions shall deserve, or as the Governor and Council shall think fit.

Essex Register, 1820.

IMPRISONMENT FOR DEBT.