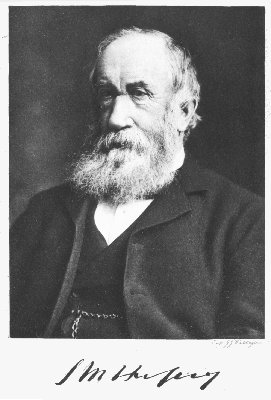

S.M. Hussey

Title: The Reminiscences of an Irish Land Agent

Author: Samuel Murray Hussey

Editor: Home Gordon

Release date: August 5, 2005 [eBook #16450]

Most recently updated: December 12, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Debbie Stoddart and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Probably the first criticism on this book will be that it is colloquial.

The reason for this lies in the fact that though Mr. Hussey has for two generations been one of the most noted raconteurs in Ireland, he has never been addicted to writing, and for that reason has always declined to arrange his memoirs, though several times approached by publishers and strongly urged to do so by his friends, notably Mr. Froude and Mr. John Bright. If his reminiscences are to be at all characteristic they must be conversational, and it is as a talker that he himself at length consents to appear in print.

In this volume he endeavours to supply some view of his own country as it has impressed itself on 'the most abused man in Ireland,' as Lord James of Hereford characterised Mr. Hussey. How little practical effect several attacks on his life and scores of threatening letters have had on him is shown by the fact that he survives at the age of eighty to express the wish that his recollections may open the eyes of many as well as prove diverting.

Possessing a retentive memory, he has been further able to assist me with seven large volumes of newspaper cuttings which he had collected since 1853, while the publishers kindly permit the use of two articles he contributed to Murray's Magazine in May and July 1887. To me the preparation of this book has been a delightful task, materially helped by Mr. Hussey's family as well as by a few others on either side of the Channel.

HOME GORDON.

13 OVINGTON SQUARE, S.W.

PREFACE

CHAP.

I. ANCESTRY

II. PARENTAGE AND EARLY YEARS

III. EDUCATION

IV. FARMING

V. LAND AGENT IN CORK

VI. FAMINE AND FEVER

VII. FENIANISM

VIII. MYSELF, SOME FACTS, AND MANY STORIES

IX. THE HARENC ESTATE

X. KERRY ELECTIONS

XI. DRINK

XII. PRIESTS

XIII. CONSTABULARY AND DISPENSARY DOCTORS

XIV. IRISH CHARACTERISTICS

XV. LORD-LIEUTENANTS AND CHIEF SECRETARIES

XVI. GLADSTONIAN LEGISLATION

XVII. THE STATE OF KERRY

XVIII. A GLANCE AT MY STEWARDSHIP

XIX. MURDER, OUTRAGE, AND CRIME

XX. THE EDENBURN OUTRAGE

XXI. MORE ATROCITIES AND LAND CRIMES

XXII. COMMISSIONS

XXIII. LATER DAYS

INDEX

PORTRAIT OF S.M. HUSSEY

PORTRAIT OF MRS. HUSSEY

'My father and mother were both Kerry men,' as the saying goes in my native land, and better never stepped.

It was my misfortune, but not my fault, that I was born at Bath and not in Kerry.

However, my earliest recollection is of Dingle, for I was only three months old when I was taken back to Ireland, and up to that time I did not study the English question very deeply, especially as I had an Irish nurse.

There is a lot of Hussey history before I was born, and some is worth preserving here.

It is a thousand pities that so many details of family history have been lost, and to my mind it is incumbent on one member of every reasonably old family in this generation to collect and set down what should be remembered about their ancestors for the unborn to come.

My contribution does not profess to be very exhaustive, but it will serve for want of a better.

When a man claims to be descended from Irish kings, it generally means that his forbears were bigger scoundrels than he is, for they were cattle-lifters and marauders, whilst his depredations are probably disguised under some of the many insidious forms of finance. Just as every Scotsman is not canny and every American is not cute, so every Irishman is not what the Saxon believes him to be. But there can be little doubt what type of men these ancient Irish sovereigns were, and I regretfully confess I cannot trace my descent from them.

The family of Hussey was of English extraction, according to that rather valuable book The Antient and Present State of the County of Kerry, by Charles Smith, 1756—the companion volumes dealing with Cork and Waterford are much less precious. Personally I always understood that the Husseys hailed from Normandy, as will be seen a few pages on, but tradition on such a point is not of much value.

Anyway the family of Hussey settled in very early times at Dingle, and also had several lands and castles in the barony of Corkaquiny.

Dingle was the only town in this barony, and it was incorporated by Queen Elizabeth in 1585, when she granted it the same privileges which were enjoyed by Drogheda, with a superiority over the harbours of Ventry and Smerwick. The Virgin Sovereign also presented the town with £300 for the purpose of making a wall round it.

The Irish formerly called Dingle Daingean in Cushy, or the fastness of the Husseys. One of the FitzGeralds, Earl of Desmond, had granted to an ancestor of my own a considerable tract of land in these parts, namely, from Castle-Drum to Dingle, or as others say, he gave him as much as he could walk over in his jackboots in one day. That Hussey built a castle, said to be the first erected at Dingle, the vaults of which were afterwards used as the county gaol.

There is mention of this in the grant of a charter to Dingle by King James I. in the fourth year of his reign: 'The house of John Hussey granted for a gaol and common hall to the corporation.'

A grim interest lurks in the fact that the dedication of Smith's History to Lord Newport, Lord Chancellor of Ireland, recites that 'this Kingdom, my lord, is a kind of Terra Incognita to the greater part of Europe.'

Is it not so to this day?

Do I not meet scores of people who tell me they would love to go to Kerry, but they have never been nearer than Killarney.

That is the sort of speech which makes me wonder how geography is taught.

It is on a par with the remark of a prominent Arctic explorer, that he had never been to Killarney because it was so far off.

People, however, who go there apparently like it.

The chief Elizabethan settlers in Kerry were William and Charles Herbert, Valentine Brown, ancestor of the Kenmares, Edmund Denny, and Captain Conway, whose daughter Avis married Robert Blennerhasset, while a little later, in 1600, John Crosbie was made Bishop of Ardfert and Aghadoe.

To-day the descendants of those settlers are still among the principal folk in Kerry, though that is more due to their own selves than to the support they had from any British Government.

This Valentine Brown, who was a worshipful and valiant knight, wrote a discourse for settling Munster in 1584. His plan was to exterminate the FitzGeralds and to protestantise Ireland; but by the irony of fate his own son married a daughter of the Earl of Desmond and became a Roman Catholic.

In the Carew Manuscript it is recorded that he estimated that one constable and six men would suffice for Cork, but for Ventry, 'a large harbour near Dingle,' one constable and fifty men were necessary; so he evidently had a clear apprehension of the villainous capabilities of the men of Kerry.

It is also recorded that in the parish of Killiney is a stronghold called Castle Gregory, which before the wars of 1641 was possessed by Walter Hussey, who was proprietor of the Magheries and Ballybeggan. Having a considerable party under his command, he made a garrison of his castle, whence having been long pressed by Cromwell's forces, he escaped in the night with all his men, and got into Minard Castle, in which he was closely beset by Colonels Lehunt and Sadler. After some time had been spent, the English observing that the besieged were making use of pewter bullets, powder was laid under the vaults of the castle, and both Walter Hussey and his men were blown up.

Prior to this, 'on January 31, 1641, Walter Hussey, with Florence MacCarthy and others, attacked Ballybeggan Castle, plundered and burnt the house of Mr. Henry Huddleston, and did the same to the house and haggards of Mr. Hore, where they built an engine called a saw, having its three sides made musket-proof with boards. It was drawn on four wheels, each a foot high, with folding doors to open inwards and several loopholes to shoot through, without a floor, so that ten or twelve men who went therein might drive it forwards. These machines were set against castle walls whilst the men within them attempted to make a breach with crows and pickaxes.'

Infernal machines are, after all, not confined to our own times, and this same rascally ancestor of my own appears to have had predatory habits more likely to be appreciated by his followers than by his foes.

Dingle is now a somewhat dilapidated town, but that was not always the case, for it is mentioned in my dear old friend Froude's History of England that the then Earl of Desmond called on the ambassador of Charles V. at his lodgings in Dingle. The old records of the place would be worth diligent antiquarian research, a matter even more difficult in Ireland than elsewhere. Should all be brought to light, I fancy the part played by my family would not grow smaller.

The Husseys spread away over the county, after having their lands forfeited under both Elizabeth and Cromwell, which was the most respectable thing to suffer in those times. In the reign of Queen Anne, Colonel Maurice Hussey sold Cahirnane to the Herberts, and there is a garden still called Hussey's Garden in the property. He built a mortuary chapel for himself on the top of a small hill just outside the gates of Muckross, where his own grave near that beautiful abbey can be seen to this day.

This Colonel Maurice Hussey resided for some time in England, and appears to have married an English lady; and it is odd that though a Roman Catholic he was trusted by the Governments of both William and Anne. There seems to have been something versatile about his rather mysterious career, the key to which may be found in the surmise that until the accession of King George he was a Jacobite at heart; which throws some doubt on his assertion in a letter that there are very few Tories—or outlaws—in Kerry, where the Whig rule was never enforced with great severity. He was, however, committed to 'Trally jail' (i.e. Tralee) on the fear of a landing by the Pretender, whence he wrote pleading letters, in one of which he mentions that his son-in-law, MacCartie, has taken the oaths of abjuration; and later, when released, he seems to have been disturbed at the large number of German Protestants, driven out of the Palatinate by Louis the Fourteenth, who settled at Bally M'Elligott.

Any one who rambles about Dingle and investigates the older buildings, so carefully examined by Mr. Hitchcock, will notice how frequent is the emblem of a tree; and that is a conspicuous feature of the Hussey armorial bearings.

With reference to the allusions made in Smith's book to my ancestors, it may be pointed out that he repeated the popular tradition at the very time when the Husseys, like the rest of their fellow Catholics all over the country, were disinherited and depressed, and when he could gain nothing by doing them honour.

As for my name, it seems to have really been Norman, and to have been De La Huse, De La Hoese, and later Husee, Huse, and, finally, Hussey.

Burke in his extinct Peerage states that Sir Hugh Husse came to Ireland, 17 Hen. II., and married the sister of Theobald FitzWalter, first Butler of Ireland, and that he died seized of large possessions in Meath. His son married the daughter of Hugh de Lacy, senior Earl of Ulster, and their great-grandson, Sir John Hussey, Knight, first Earl of Galtrim, was summoned to Parliament in 1374.

Moreover, the State Papers in the Public Record Office, quoted in the Journal of the Royal Society of Irish Antiquaries for September 1893, p. 266, prove beyond question that Nicholas de Huse or Hussy and his father, Herbert de Huse, were land-owners of some importance in Kerry in 1307. Stirring times they must have been, of which we have no fiction under the guise of history, though then men had to fight hard to preserve their lives and maintain their dignity. We can imagine the tussle, even in these degenerate days when no challenge follows the exchange of insults, even in the House of Commons, and when the perpetration of the most cowardly outrage in Ireland has to be induced by preliminary potations of whisky. Of course, those old times were bad times, but the badness was at least above board and the warfare pretty stoutly waged. There is some sense in fighting your foe hand to hand, but to-day when a battle is contested by armies which never see one another, and are decimated by silent bullets, the courage needed is of a different character, and the wicked murder of such combats is obvious.

But let us quit war and confiscation for the equally stormy region known as politics, wherein it may be noted that in 1613 Michael Hussey was Member of Parliament for Dingle.

Now for a coincidence in Christian names.

Only two Husseys forfeited in the Desmond Rebellion, and they were John and Maurice.

In the Irish Parliament of James II., when Kerry returned eight members, two of them were Husseys, and their names were John and Maurice.

My grandfather's name was John, and his father before him was Maurice, and I christened my two surviving sons John and Maurice.

We do not go in for much variety of nomenclature in our family.

My grandfather, John Hussey, lived at Dingle, his mother being a member of the well-known Galway family of Bodkin. He was an offshoot of the Walter Hussey who had been converted into an animated projectile by the underground machinations of Cromwell's colonels. He was a very little man, who had a landed property at Dingle, did nothing in particular, and received the usual pompous eulogy on his tombstone. I never heard that he left any papers or diaries, and I do not think that he ever went out of Kerry—he had too much sense.

A rather diverting story in which his sister was the heroine may be worth telling, if only because it was so characteristic of the period.

In those days, as now, Husseys and Dennys were closely associated, and both my great-aunt and Miss Denny, known locally as the 'Princess Royal,' were going to a ball. At that time it was the fashion for the girls of the period to wear muslin skirts edged with black velvet. The muslin was easily procured; not so the velvet, which was eventually obtained by sacrificing an ancient pair of nether garments belonging to my great-grandfather.

After the early dinner then fashionable, each of the damsels was departing for the Castle, with a swain at the door of her sedan-chair, when our kinswoman, Lady Donoughmore, who was on the door-step watching them off, enthusiastically shouted:—

'Success to the breeches! Success to the breeches!'

Imagine the horrified confusion of the poor 'Princess Royal,' not then eighteen.

This episode reminds me of the modern Scottish story of a tiresome small boy who wanted more cake at a tea-party, and threatened his parents with dire revelations if they did not comply with his demands. As they showed no signs of intimidation, he banged on the table to obtain attention, and then announced:—

'Ma new breeks are made out of the winter curtains.'

An incident connected with one of the earliest private carriages in Kerry is worth telling. The vehicle in question had just been purchased by a certain Miss Mullins, daughter of a former Lord Ventry, who regarded it on its arrival with almost sacred awe. A dance in the neighbourhood seemed an appropriate opportunity for impressing the county with her newly acquired grandeur, but the night proving wet, she insisted on reverting to a former mode of progression, and rode pillion behind her coachman.

The result was that she caught a violent chill, which turned to pneumonia, and as her relatives were assembled round her deathbed, the old lady exclaimed, between her last gasps for breath:—

'Thank God I never took out the carriage that wet night.'

My father, Peter Bodkin Hussey, was for a long time a barrister at the Irish Bar, practising in the Four Courts, where more untruths are spoken than anywhere else in the three kingdoms, except in the House of Commons during an Irish debate. All law in Ireland is a grave temptation to lying, and the greatest number of Courts produced a stupendous amount of mendacity—or it was so in earlier times, at all events.

Did you ever hear the tale of the old woman who came to Daniel O'Connell, outside the Four Courts, as he was walking down the steps, and said to him:—

'Would your honour be so kind as to tell me the name of an honest attorney?'

The Liberator stopped, scratched his head in a perplexed way, and replied:—

'Well now, ma'am, you bate me intoirely.'

My father had red hair, and was very impetuous. Therefore he was christened 'Red Precipitate' by Jerry Kellegher.

This legal luminary was a noted wit even at the Irish Bar of that time, a confraternity where humour was almost as rampant as creditors—irresponsible fun, and a light purse are generally allied; your wealthy fellow has too much care for his gold to have spirits to be mirthful.

The tales about him are endless. Here are just a few I have heard from my father's lips.

Jerry had a cousin, a wine merchant, who supplied the Bar mess, and a complaint was lodged that the bottles were very small.

To which Jerry retorted:—

'You idiot, don't you know they shrink in the washing,' which satisfied the grumbler. And that always seemed to me the strangest part of the story.

In those days religious feeling ran pretty high—I will not go so far as to say it has entirely died down to-day—and the usual Protestant toast was:—

'The Pope, the Devil, and the Pretender.'

Now, Jerry was a Roman Catholic, none the less earnest because he had a merry way with him. On a certain Friday he was seen to be fasting by a very foppish barrister, who thought a great deal of himself.

He remarked to Jerry, with unnecessary impertinence:—

'Sir, it appears you have some of the Pope in your stomach.'

To which Jerry, quick as a pistol-shot, retorted:—

'And you have the whole of the Pretender in your head,' after which there was the devil to pay.

There was a certain Chancellor in Ireland who was born a few years after his father and mother had separated. As he did not like Jerry, he used to make a great fuss about how he should pronounce his name. At last in Court one day he burst out:—

'Pray tell me what you wish me to call you—Mr. Kellegher, or Mr. Kellaire?'

'Call me anything you like, my lud, so long as you call me born in wedlock.'

The Chancellor did not score that time.

At one time there were grave complaints made about the light-hearted way in which Jerry handled his cases, and his practice fell off. He was conversing with a very stupid judge, lately elevated to the Bench, and observed:—

'It's a very extraordinary world: you have risen by your gravity, and I have fallen by my levity.'

He had a son who, in my time, had a large practice at the Bar, but I never came across him, nor did I ever hear that there was anything remarkable about him, except that he was not so witty as his father, which was not wonderful.

After all, as Jerry was before my own experience, I must not delay over him, so I will only give one more tale about him, and pass on.

When Lord Avonmore got his peerage for voting for the Union, he had his patent of nobility read out at a dinner-party, and it commenced, 'George, of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.'

'Stop,' cried Jerry, 'I object to that. The consideration is set out too early in the deed.'

This long digression over, I revert to my father about whose respectable practice at the Four Courts I know nothing except that he allowed others to become judges, and did not find solicitors putting his services up to auction.

By the death of his elder brother, he succeeded to a property, near Dingle, on which he went to live and then got married, which was the wisest thing that he could do.

My mother was Mary Hickson, and her descent was this wise.

The Murrays were said to have come to Scotland from Moravia in the first century; and a pretty bulky history of the clan reveals as much truth about them as the author cared to put in when tired of inventing less probable facts. Sir Walter Murray, Lord of Drumshegrat, came to Ireland with Edward de Bruce and was killed in battle, leaving three sons, one of whom, christened Andrew, settled in County Down. Some of his descendants migrated to Bantry, where, in 1670, William Murray married Ann Hornswell, and was succeeded by his third son George, who was in turn succeeded by his eldest son William, who married Anne Grainger. Of the marriage, there was only one daughter Judith, who married Robert Hickson, heir to the property.

They had five sons and two daughters, the younger of whom married Sir William Cox, and the elder my father.

The superior of my dear mother never drew the breath of life. She lived until I was twenty-five, and I never met any man who could say more than I could for my mother, though equalled by what my own sons could say of theirs, and she too came of the same stock, for I married my first cousin, Julia Agnes Hickson. It is said no man is thoroughly happy until he is suitably married, an opinion I absolutely endorse; but happiness so great as my married life is not of public interest, and if it were, I should not wear my heart on my sleeve for general inspection. Any tribute from me to my dear wife would be superfluous; the devoted love of our children has been the endorsement by the next generation of the feelings which I have always felt towards her.

She was the daughter of my mother's eldest brother, John Hickson, called the Sovereign of Dingle. He had powers to collect customs, to hold a court, and to try cases in much the same way that a lord provost had.

On one occasion when a case was to be tried, two attorneys appeared from the town of Tralee, about thirty miles off. Now John Hickson had his own ideas about the attorneys of those days—ideas such as all honest men had, but dared not express. So he sent a crier through the town to say that the court was adjourned for a fortnight. When the appointed day arrived, the attorneys arrived also, so again the melodious tones of the crier proclaimed through the town that the court was adjourned for yet another fortnight, Captain Hickson remarking to his wife that he was not going to be helped to administer justice by those who earned their living on injustice. The attorneys gave it up in despair, leaving Captain Hickson to lay down the law as he liked, and to do him justice, his ideas were more conducive to peace and order than the arguments of Irish attorneys generally are.

He was loved and revered by the people, so that when the cholera raged in 1833 and 1834, and the constabulary were ordered to go into the houses to remove the corpses (this to prevent the people 'waking' the dead, and so spreading the contagion), they dared not enter the cabins unless Captain Hickson went with them, as the people were so enraged at their dead being molested that they would have killed the police. Fortunately Captain Hickson had enough moral influence to make the people obey the law.

In the eighties he would have been shot in the back by some scoundrel who had primed himself with Dutch courage from adulterated whisky.

He raised a Yeomanry Corps at the time of the Whiteboys to guard the country against these lawless bands, and against the dreaded French invasion. This regiment was called the Dingle Yeomanry, and the tales about it are many.

On one occasion when Captain Hickson was in London, the general from Dublin inspected the corps. In the absence of the commanding officer, his brother was ordered to parade the battalion, and being a nervous young man, he completely forgot all the words of command, so to the unconcealed amusement of the old martinet from the capital, he shouted:—

'Boys, do as you always do.'

It says well for the discipline of the regiment that they did not implicitly obey the order.

His mother, this Mrs. Judith Hickson, was the only one of my grand-parents I ever saw, and very little impression she has left on my memory, except a notion that she had less sense of humour than pertains to most Irishwomen by the blessing of God and their own mother wit.

My father was a Roman Catholic, and my mother a Protestant. By the terms of the marriage settlement, we were all brought up in her faith, which occasioned a tremendous row at that time, and nowadays would never be tolerated by the priests.

All the same my father was an obstinate man, not disposed to care much for the whole College of Cardinals, and indifferent if he were cursed with bell and book. Of course he was not a good-tempered man, or he would not have justified his nickname of Red Precipitate, but he spared the rod with me, and failed to keep me in order. I was the youngest of a pretty large family and the pet into the bargain.

My eldest brother, John, was drowned at St. Malo. He was unmarried, and his profession was to do nothing as handsomely as he could.

James was in the 13th Light Dragoons, and subsequently in the 11th. He saw no service, and was an excellent soldier at mess and off duty. I am not qualified to speak with authority about his fulfilment of the trumpery trivialities which fill up garrison life, but here is one anecdote about him.

Soon after Lord Cardigan took command of the 13th Light Dragoons, a great many of the officers left the corps, and a man wrote to the papers to say that this was chiefly due to the great expense of the mess.

My brother retorted in print that for his part the reason was due to its being 'incompatible with my feelings as a gentleman to remain in the regiment as it is equally impossible to exchange out of a regiment that has the undeserved misfortune to be commanded by his lordship.'

Edward lived at Dingle, and was much liked by the people there. He was an active magistrate and a conscientious man. He married and left two sons, one in the Horse Artillery and the other a colonel in the Engineers. They have all joined the great majority.

Robert, who chose to be an army surgeon, died in India, leaving me without a relation in the world of my own name.

It reminds me of the story in Charles O'Malley about the old family in which it was hereditary not to have any children. However, I altered that by having eleven of my own, two sons, John and Maurice, and four daughters being alive, at the present time. More power to them say I, in the current phrase of good-will in Kerry.

My sister Mary died at Bath when I was born. It was her health which prevented me from being by birth what I am at heart, a Kerry man.

Ellen was married to Robert, elder brother of the late Knight of Kerry, and her grand-daughter is married to Colonel Thorneycroft of Spion Kop fame.

Ellen's sister, Julia, married Sir Peter FitzGerald, Knight of Kerry. The two therefore married brothers, and if there had been any more they might have done the same.

I suppose I ought to give the date of my birth, but despite all the efforts of those in Ireland, who loved me so much that they became active agents to convey me to heaven, I cannot yet give you the date of my death.

My friend, Mr. Townshend Trench, is, I believe, writing a book to prove the world will come to an end in about thirty years' time, but that will see me out, and those then alive may discover that the Great Landlord has given the tenants an extension of the lease of the earth.

I was born on December 17, 1824, and I have none of those infantile recollections which are such an insult on the general attention when put in print.

Still my earliest memory is so characteristic of much that was to follow that I set it down.

The very first thing I remember is being placed on the seat of a trap beside the local R.M. (Resident Magistrate), and thus going out, escorted by a party of soldiers, to collect tithes.

I clapped my hands with glee, but an old woman by the road-side said that it was a shame to take out that innocent babe on such bloodthirsty work.

I could ride before I could walk, and was always fond of the exercise. What Irishman is not?

My taste for this was fostered by my father, who had broken his leg when young, and not only disliked walking, but had a slight limp, which did not prevent him being in the saddle for many hours each day.

As a child, I led a fresh, natural, out-of-doors, healthy life, exposed to wind and rain, and all the better for both. There are very few trees about Dingle, and I quite agree with the remark of an American that it was the most open country he had ever seen.

I was always bathing, but I never got drowned, not even in liquor, although I have sat with some of the best in that capacity. I have myself been pretty temperate in everything, to which I attribute my longevity. And yet I am not sure that any rule can be laid down in this respect, for I have known men who saturated themselves in alcohol until they ought to have been kept out of sight of all decent people live longer than those that have kept straight in every way.

In proof of this, let me quote the delightful account of a centagenarian out of Smith's History of Kerry, a book already referred to, and which can now be finally put back on its shelf, dry as dust, as Carlyle might say, 'but pregnant with food for thought, ay, and for grim mirth,'—those are not exactly the words of the Sage of Chelsea, but just have the rub of his tongue about them.

'Mr. Daniel MacCarty died in February 1751,' as the account said, 'in the 112th year of his age. He lived during his whole life in the barony of Iveragh, and buried four wives. He married a fifth in the eighty-fourth year of his age, and she but a girl of fourteen, by whom he had several children. He was always a very healthy man, no cold ever affecting him, and he could not bear the warmth of a shirt at night, but put it under his pillow. He drank for many of the last years of his life great quantities of rum and brandy, which he called the naked truth; and if, in compliance to other gentlemen, he drank claret or punch, he always took an equal quantity of spirits to qualify those liquors: this he called a wedge. No man ever saw him spit. His custom was to walk eight or ten miles in a winter's morning over mountains with greyhounds and finders, and he seldom failed to bring home a brace of hares. He was an innocent man, and inherited the social virtues of the antient Milesians. He was of a florid complexion, looked amazingly well for a person of his age and manners of life, for his use of spirituous liquors was prodigious, a custom that much prevails in these baronies.'

Indeed, no one who was slightly acquainted with the characteristics of the inhabitants of the Kingdom of Kerry would suggest that total abstinence was even to-day their predominant virtue.

It is the fashion to say that it is a good thing to be one of a large family. From a financial point of view I am quite certain that the reverse is preferable, and as I was the youngest of nine—two others besides those I mentioned, James and Anne, coming to early demises—I received as many kicks and cuffs from my brethren as I did halfpence and affection from my parents. So, like Thackeray, as a child I sympathised with Lord MacTurk who wished to cut off the heads of his brethren. Now I have survived them all, and I fondly regret the sounds of voices that are still.

But as I sit in my arm-chair and ruminate over the past, which every old man must do in the intervals of reading the Times, going to the club, or losing his money by careful attention to speculation, I have the consolation of remembering that I did as much mischief as any other child. To be a really good child means that the animal is a prig or unhealthy. To-day I am fond of all my grandchildren, but the one I like best is the one which proves himself or herself the naughtiest for the moment.

This is a hard saying for parents, and not a good precept for the young, but there is solid truth in it and a bit of common-sense too, for it is best to get the original sin out in the years of innocence.

Perhaps the biggest wrench in life is going to school. It may not seem so very much afterwards—as the boy said of the tooth when he looked at it in the dentist's forceps—but the wrench is really bad.

I learned my letters from my mother, and picked up a few other smatterings before I had daily lessons from a tutor at Dingle. Strange to say, a very good classical education could have been obtained there in the thirties, better, so far as I can estimate, than could have been expected from a town double the size at the same period in England.

At the age of ten I was sent to Huddard's, then a very sound school in Dublin. I was well enough taught, not caned enough for my deserts, though more than sufficed for my feelings, and sufficiently fed, but at the end of two years I had to leave owing to ill health.

An apothecary, who selfishly recollected that the more medicines I took the better for him if not for me, converted me into a human receptacle for his empirical abominations, but another surgeon, who was rather tardily called in, packed me off to the country.

One of the leading Dublin physicians certified that I had only one lung; but as the other has served me faithfully for sixty-nine years, I am rather sceptical as to the accuracy of his diagnosis.

I remember very little about Huddard's, except that it was in Mountjoy Square, and about a hundred boys were herded there in unsought proximity. We boarders always fought the town boys, but also had to cajole them in humiliating ways to smuggle us in contraband articles of food. The meals at Huddard's were fairly good, no doubt, as school fare goes, but the sugary stick-jaw stuff for which the soul of a boy longs was naturally not part of the official bill of fare. The bullying was of a reasonable nature, or at all events I could hold my own with the best of them, being indifferent to punishment so long as I could hit out effectively from the shoulder. One of the ushers, a dwarf of malignant disposition, was an awful tyrant, and we always had an ardent desire to tar and feather him, only we did not know how to set about the operation even if we had ventured to attempt it.

After a happy interval of convalescence at home, I was sent to a smaller school kept by Mr. Hogg at Limerick. One of the boys there subsequently became that illustrious ornament of the Bench, Lord Justice Barry.

He was a very eloquent man, counted so even at the Irish Bar, where a certain high-flown loquacity is pretty prevalent, and had a great repute. He arrived at Cork once, and had to fight his way through a dense throng to get into court. On inquiring the reason of the crowd, he was told that everybody wanted to hear the big speech that was expected from Councillor Barry.

'Well, unless you make way for me it's disappointed every mother's son of you will be, for I am twin to Councillor Barry, and I never heard tell he had a brother.'

He carried on the old-fashioned habit of after-dinner conviviality, and used to sit drinking three hours after the wine had been put on the table, which was why I never accepted his hospitality in after years, for, as I said before, I am a man of moderation.

In my young days it was the regular thing to bring in whisky-punch after dinner; and for many years I regularly took one tumbler and never had a second, not once to the best of my recollection.

There is a good deal of change in the habits of life. When I was a boy coffee was unknown for breakfast, cocoa had not become known as a beverage, and tea was regularly drunk. We seldom took lunch, nor did the ladies, and afternoon tea was unheard of. Instead, tea was brought into the drawing-room about eight in the evening, and was always drunk very weak and sweet. In those times it was invariably from China and pretty costly.

We dined at five. Dinners were very solid. Soup was a pretty regular opening, but could be dispensed with without comment, and it was almost always greasy. At Dingle fish was pretty plentiful, but sweets were regarded as a great extravagance.

I remember, when grown up, dining with an elderly man near Cahirciveen, who had a turbot for which he must have paid at least eight shillings, but he apologised for not having a pudding on account of the necessity for economy, though a pudding would not have cost him eightpence.

Made dishes were very few and badly cooked. The food was chiefly joints, and, in nine cases out of ten, roast mutton. Vegetables were not so much eaten as now, always excepting potatoes, which were consumed in large quantities. There was practically no fruit, except a few apples and oranges at Christmas.

Men sat very long over their wine. Sherry used to be served at dinner and often claret afterwards, but the great beverage was port. I am inclined to think that port has sensibly deteriorated since my young days. It was as a rule more fruity then, but we never talked of our livers, as subalterns and undergraduates do nowadays.

Port used to come direct to Dingle. It was an easy harbour 'to run,' and there was some smuggling.

On one occasion some soldiers were sent to protect the gauger, who was bent on making an important seizure. A few of the inhabitants of Dingle took the opportunity of entertaining the officer, and whilst he slumbered from the effects of their hospitality, the opportunity for making the seizure was lost.

There is no particular reason why I should tell the following story here, but it is worth recording, and I don't know any other part of my reminiscences where it is more likely to slip in appropriately.

In Kerry in 1815, the farmers had been an extra long time fattening up their pigs. After the Peace, prices all fell, and though the farmers were reluctant, they had to yield to circumstances. One day the dealers were buying at extremely low rates in Tralee market, when the postman brought the news that Napoleon had escaped from Elba.

Instantly all the farmers broke off their bargains, and proceeded to start homeward with their swine, shouting:—

'Hurrah for Boney that rose the pigs.'

My mother often told me of this scene, which she herself witnessed.

There was always a distinct sympathy with France, owing to the smuggling from that land, and after the English had prohibited the exportation of wool, it was smuggled into France, whence were brought back silks and brandy.

The geography of Kerry is ideal for landing contraband store, and I should say even more was done in this respect locally than on the coast of Scotland.

There is a certain amount of good-will between people whose mutual interests are similar until they fall out, and the hope of a French landing in Ireland, though never very serious, always fanned the native disaffection to the Government in the West.

The veracity of an Irishman is never considerable, for as a rule he will say what he thinks likely to please you rather than state any unpleasant fact. Of course the gauger—excise officer—was an especially unpopular personage, and I doubt if a tithe of the lies told to him were ever considered worthy of being confessed at all.

O'Connell's family made much money by smuggling, which was a pursuit that carried not the slightest moral reproach. Indeed 'to go agin the Government' in any sort of way has always been an act of super-excellence.

The most lucrative side of the commercial enterprises of Morgan O'Connell was his trade in contraband goods. In Derrynane Bay, he and his brother landed cargoes which were sent over the hills on horses' backs to receivers in Tralee.

Of O'Connell himself most stories have been told, but it is difficult to indicate the enormous influence he had over the lower classes in his own country.

Years before George IV. had aptly expressed the situation amid his maudlin tears over Catholic emancipation.

'Wellington is King of England, O'Connell is King of Ireland, and I suppose I'm only considered Dean of Windsor.'

As an advocate, the Liberator had many of the attributes of Kenealy, and his popularity was so great that he was often briefed in every case at an assize.

There is no doubt that he bullied judges, was allowed enormous laxity in browbeating opposing counsel and witnesses, and, like Father O'Flynn, had a wonderful way with him, so far as the jury was concerned.

When I saw him in Dublin, I at once realised how true must be the bulk of the stories of his great conceit. He has been elevated into a superhuman being by the posthumous praise of hundreds of blatant mob orators.

Dan had two brothers, John and James. The latter was the first baronet, and noted for his witty sayings.

He presided at a dinner given for the purpose of presenting an address to the manager of a bank. On the toast of the Army and Navy being proposed, the only man who could return thanks for the former was a solicitor named Murphy, who said that if he were forced to respond to the toast, it clearly proved what a peaceful community they lived in, adding:—

'It is such a long time since I laid by the sash and the sword, that I have forgotten my drill.'

'But you have never forgotten the charge,' observed the chairman, who had a long bill from Murphy in his pocket at the time.

On another occasion, a lady spoke to James about subscribing to the Roman Catholic Cathedral at Killarney.

'For my part,' she observed, 'it's little I can do in my lifetime, but I have left all my money for the good of my soul.'

'I believe, ma'am,' says James, 'you were an original shareholder in the Provincial Bank. The shares are now quoted at eighty and they pay six per cent. That is very much like twenty-one per cent. on the original capital.'

'I am not a clever man like you at making these calculations,' replies the lady; 'I have higher and holier things to think about.'

'Don't say that again to me, ma'am,' says he. 'I put my money into farms, and I get five per cent, from a grumbling and unsatisfactory set of tenants. And what are you getting? Twenty-one per cent. in this world and salvation in the next. It's the most damnable interest I ever heard tell of, either in this world or any other.'

Yet another tale about him.

He had received an unconscionable bill of costs from an attorney, and happening to meet a Roman Catholic bishop in Cork, he asked him if an attorney could ever be saved.

'Why not? Even an extortioner can be if he make ample restitution in his life-time, and dies fortified with the rites of the Church.'

'May be so, my lord,' replied Sir James, 'you know more about these things than I do, but if it is as you say, you are taking a confounded amount of unnecessary trouble about the rest of us.'

The bishop was not a bit disconcerted.

'I am an honest labourer striving to be worthy of my hire,' he explained.

And at that Sir James left it, because he said it was not respectful to ask too many invidious questions about a man who had the making of your soul at his own will.

All this is a digression from my education, which was as desultory as these reminiscences.

After a spell at Limerick I was again sent home ill, and for six months I really had to be treated as an invalid. I was always very fond of books, notably history, and I think I have read pretty well every book published upon the history of Ireland. It was at this time I began teaching myself a bit, and that is the teaching which is better than any other, except what one has to learn against one's own will and for one's own advantage in the school of life. Like a good many other people I was led to history not only by a shortage of lighter books at home, but also by curiosity aroused by the novels of Sir Walter Scott. In the way of promoting better reading, I believe Scott has been far more beneficial than any other writer of fiction in English.

I was for a short time at school in Exeter, and then at a rather rough establishment at Woolwich, where my father wished me to have the tuition in mathematics which could be obtained from the masters in the Academy at irregular times. By all accounts the fagging and bullying in that establishment were appalling. The headmaster of the school I was at was an able fellow, and many of the cadets used to come to have a grind with him. Some of their tales were 'hair-erectors,' as the Americans say.

One new boy had the misfortune to sprain his ankle, and to incur the fury of the head of dormitory on the same evening. The latter tied his game ankle up to his thigh, and fastening him by the wrist to the bottom of the bed, made him stand the better part of the night on his bad ankle.

This reminds me of the story of a certain royal prince going to an educational establishment and being asked who his parents were. On his reply, the senior—or 'John'—gave him a terrific cuff on the side of the head saying:—

'That's for your father, the prince.'

And before the half-stunned boy recovered, he received a stinging blow on the other ear with:—

'That's for your mother, the princess, and now black my boots.'

His Highness could say nothing, but in time he grew to be the biggest and the worst bully.

Then the younger brother of his former tormentor came, and the prince sent for him, and telling him what his brother had done some years before, made him bend down and flogged him so unmercifully that he had to go into hospital.

Years after, when in an important position, he met his former victim, now a general, and congratulating him on his career said:—

'Perhaps I made your success by giving you that tanning at Sandhurst.'

I wonder whether there was murder in the heart of the grim old warrior at the recollection. Of course that would not be strange, for many a time officers have been actually shot in action by their own men.

Here is a perfectly true story, only neither the men nor the officer need be specified.

A colonel who had grossly mismanaged the regiment knew his fate was sealed.

So when the men paraded for the engagement, he said:—

'I know you mean to shoot me to-day, but for God's sake don't do so until we have won the battle.'

This was greeted with a cheer, and he came back safe to be decorated and to play whist at his club as badly as any member in it.

I am not sure that cards ought not to be considered part of every lad's training. If a man goes through life without touching a card, he probably loses a good deal of innocent amusement, and debars himself from much pleasant society. If he learns to play when grown up, he may find it a costly and unsatisfactory branch of education. But if he is taught to play reasonably well as a boy, and is shown that excellent games can be had without gambling—I do not consider an infinitesimal stake, in proportion to his means, gambling—he will have an extra amusement made for him and a relaxation after his day's work.

A near relative of my own gets his club cronies to play bridge with his son, aged eighteen, and pays his losses, in order that he may be thoroughly grounded in the game. The lad is a capital boy, and all the better for his early association with elder men on their own level.

One of the resources of my old age is three games of picquet every night after dinner with my wife, and very much I enjoy them. There is often the fashionable bridge played in the room by my children and their friends, but I have never taken a hand, though in younger days I derived a fair amount of diversion from whist.

My years of schooling having come to an end, I was back in Ireland in full enjoyment of youth, high spirits, and thoughtless carelessness. These holiday times were delightful. I could be in the saddle all day if I liked, was free to shoot or bathe as I pleased, had dogs at my disposal, could pass the time of day with all sorts and conditions of men—a thing which I have relished all my life—and in fact led the gay existence of the younger offshoot of an Irish squire.

In those days things were not so impecunious in Ireland as they subsequently became, but there was always a vivacious Hibernian scorn for false pretension, and a determination to have the best possible time, such as you can read in Lever's novels of old, and the capital tales of those two clever ladies, Miss Martin and Miss Somerville, to-day.

It is perfectly true that there are many Irish landlords in sporting counties who cannot have three hundred a year, and yet all their sons and daughters manage to hunt four days a week.

This would be impossible out of Ireland, and is absolutely incomprehensible even there; but the fact remains that it is done, and all one can remark is to echo the patter of the conjuror:—

'Wonderful, isn't it?'

I, however, was not destined to be left a derelict at home, as falls to the hapless lot of far too many good fellows in Ireland.

There were a good many family counsels, and the authorities could not make up their minds what to do with me. However, I thought farming was the idlest occupation, and suggested it should be my profession—an idea hailed with rapture, principally because it saved everybody the trouble of racking their brains about me.

Personally, I have often regretted that what in modern phrase may be called the 'Stevenson boom' did not coincide with my search for a career. Big posts were in due time going for engineers; and those young men who had the stamp of apprenticeship to, or association with, the great man could get almost anything in the days of the fever for railway construction.

Even later than the period I am now recalling, the journey from Dublin to Dingle would take more than two days, and, so far as I can recollect, it certainly took five from Dingle to London. Those coaching journeys were terrible experiences in wet weather, for you were drenched outside and suffocated inside, whilst you paid more than three times the present railway fare for the miserable privilege of this uncomfortable means of transit.

The old posting hotels used to be uncommonly good and comfortable, whilst they did a thriving trade. The coach purported to give you ample time to breakfast and dine at certain capital hostels, but by a private arrangement between mine host and the guard and driver, the meals used to be abruptly closured in order to save the landlord's larder.

On the way down from Dublin, a thirty minutes' pause was allowed at Naas for breakfast; but on the occasion of my story, as well as on every other, after a quarter of an hour the waiter announced the coach was just starting.

Everybody ran out to regain their seats, except one commercial traveller, who picked up all the teaspoons and put them in the teapot before calmly resuming his meal.

Back came the waiter with:—

'Not a moment to spare, sir.'

'All right,' said the traveller; 'which of the passengers has taken the teaspoons?'

The waiter gave one glance of horror, and then proceeded to have every one on the coach examined for the missing articles.

By the time that the commercial traveller had calmly finished a hearty meal there was nearly a riot, and then he emerged from the coffee-room, and suggested that the waiter had better look in the teapot.

By the way, I don't fancy that he regularly travelled on that road, for he would have been a marked man at Naas for years to come.

I was seventeen at the time when I had decided, with parental acquiescence, to be a farmer, and I was sent to learn my profession to the south of Scotland, to a farmer named Bogue.

I there acquired, at all events, one curious fact, which has stuck in my head ever since, and it is thus:—

Scotland and Ireland are governed by the same Sovereign, Lords, and Commons. Scotland is the best farmed country in Europe, and Ireland about the worst.

One pair of horses in Scotland were then supposed to cultivate fifty acres of tillage, and in Ireland the average was one horse to five acres. Indeed it is in both cases much the same to-day.

In reality a farm is a workshop from which you turn out as much produce as possible. But on an Irish farm it is the habit to squeeze out the last possible ounce without putting anything in, for it is not run with an eye on future years, but only in a hand-to-mouth, beggar-the-soil kind of way, without a thought beyond contemporary exigencies.

There were several other pupils with Bogue, but I stuck to the business more than the rest, who were perpetually gallivanting into Kelso, or even going up to Edinburgh, where they learnt nothing which taught them their trade or put money into their pockets. Therefore it happened that I was selected by Bogue to have an excellent practical demonstration of farming, after this wise. He had a pretty sharp illness, and left me for a short time full management of all his six hundred acres, and that bit of responsibility made a man of me once and for all. I stepped out of boyhood instantly, and became an adult in feelings and bearing; but to this day I hope my sense of fun is only keener than it was as a lad.

I acquired a good deal of common sense in Scotland, and learnt to observe for myself, a thing many men never acquire, and on their deathbeds they will never be able to enumerate the opportunities they have consequently lost.

As I was to be a farmer, I thought it was no use to confine my attention to the one I was on, but contracted the habit, when work was at all slack, of going about to pick up what wrinkles I could from other proprietors, as well as to make observations on my own account.

Subsequently I have made two agricultural tours through Scotland for the same purpose, getting as far north as Sutherland, in order to find out how the Highland farmer dealt with more barren soil under a less propitious climate. I have noted more improvement in farming in Ayrshire in the interval than in any other county. Yet there is a letter in existence by Burns in which he observes that Ayrshire lairds are getting English and East Lothian notions about rents, and raising them so high that it will soon be a wilderness.

The fact is that the Scotsman is a farmer by nature, but the Irishman is a farmer by inclination.

An Irishman tries to exist on land cultivated by the minimum amount of labour, and does not farm a bit better if his land is cheaper.

Every farmer in Scotland and England is laying down his land in grass, and giving up tillage as fast as he can. It is notorious that Ireland is more suitable for pasture than tillage, and yet the Government have constituted a Board to break up the rich grazing lands in Ireland and divide them into small tillage farms, on which the tenants could not get a decent living even if they had it free of rent and taxes.

Old Bogue was a bachelor by profession, and his polygamistic tendencies were duly concealed, though pretty generally known, as most things are in the country. He had as housekeeper a woman so skinny that it made you feel cold to look at her, and her disposition was on a par with her appearance. Of course, it suited the national thrift, particularly congenial to Bogue, to feed us meanly, but we did not relish her parsimonious economies.

There was one thing none of us might shirk, and that was regular attendance at kirk on Sunday. I have been a church-going man all my life—in my late years in London I have especially appreciated the beautiful services at St. Anne's, Soho—but the kirk has always been the breaking of precious ointment over an unworthy head, so far as I am concerned. The improvised prayer, that is always so carefully prepared, and is often one delivered in regular rotation, always seems to me rather humbugging for that reason, and the tremendously long sermons, which have a minimum of three quarters of an hour, no matter what the text or the ability of the preacher, are to me a vexation of spirit. I have occasionally heard good sermons in kirk, but I think the standard of Scottish preaching has always been overrated.

Moreover, I agree in the main with the American critic of sermons, who said if a preacher can't strike ile in ten minutes he has got a bad organ, or he is boring in the wrong place. It is always unfair to bore in the pulpit, because the congregation have no means of retaliation except by subsequently staying away, and in the country that is not compatible with the public worship of their Maker.

We have all heard the traditional stories about the divines who, having found the sand of the hour-glass exhausted, calmly reversed it and continued for a second spell, to the complete satisfaction of the congregations. But in my experience only one preacher could have done that without unendurably provoking me, and he was Archbishop Magee, of whom I shall have something to say when I am dealing with County Cork.

For the Scots in character I conceived much respect and little enthusiasm. If there is anything more remarkable than the hard-working powers of the Scottish farmer it is his capacity for hard drinking. But that only makes him offensive in his brief conviviality and morose in the long subsequent sulkiness. Whereas I defy you to be seriously angry with a drunken Irishman, if you have a due sense of humour—and without that you have lost the salt of life. To my mind there is something austere in the better characteristics of the Scot, and also something hypocritical about his morality. You always hear that professed in Scotland, and never in Ireland. But in the latter fewer illegitimate children are born than in any other country in Europe, and in Scotland—notably Glasgow—the high percentage has become sadly proverbial. Yet, despite these adverse points, the Scottish character has a native grandeur which must provoke admiration, though all my warmth of feelings goes to my own oft-erring countrymen.

I returned to Ireland in 1843 with the intention of farming in Kerry on the scientific system I had learned in Berwickshire. However, I found the land so subdivided that it was not only difficult, but impossible, to obtain a farm of sufficient size to return a reasonable percentage on the necessary outlay. The population of Kerry was then 293,880, and the land was divided into 25,848 farms, the holders of which, I may say, entirely depended for existence on 26,030 acres of potatoes. To give an example of the intense love of subdivision, I knew a case where one horse was the property of three 'farmers,' and as they differed as to who was to pay for the fourth shoe, they sold the horse, which was bought by an uncle of mine.

Few farmers ate meat except at Christmas. They wore homespun flannel and frieze, and their only luxury, whisky, was obtainable at a quarter of its present price. A young couple were considered ready to start in married life when they had obtained a 'farm,' consisting of a couple of acres for potatoes and a mud hovel for themselves; and thus a population, dependent on a precarious root, increased very rapidly. It was thicker near the sea coast than inland. The rents then were about double what they are now (though half what they had been at the beginning of the nineteenth century), yet, with good potato crops, people seemed content and times were fairly good. I should say there was not such general drunkenness as in later times, and very little porter was consumed in those days—at all events outside Dublin. What schools there were were shockingly bad, and reading, not to say writing, was an exceptional accomplishment, not only among the labouring classes, but among those who held their heads much higher. This of course impressed me coming straight from Scotland, where a really grand education has been the national birthright for generations.

I began to farm about sixty acres near Dingle, and gave my entire time to it, an assiduity I have compared in my mind to that of the Norwegian reclaiming the little arable spots on the mountain. We both worked pretty hard for very scanty results. I did not even live on my tiny property, but with my mother—my father had died after I returned from my English schools and before I went to Kelso.

Still matters were not long satisfactory, owing to the failure of the potato crop in 1845, when the mortality became fearful in consequence.

So at the very end of the year I migrated from Kerry to become an assistant land agent in Cork, and thus really embarked on the profession of my life—one which, on the whole, I have most thoroughly and heartily enjoyed.

I hoped then that I had not done with my beloved Kerry, and my association with that great kingdom has indeed been lifelong. I have always understood the feeling of the Irish emigrants who have had sods of their native earth sent out to them to the New World. Heimweh is after all a good thing, and Kerry to me would always seem to be appealing, however far I had roamed.

Had I been able to obtain a reasonably large farm near Dingle, I should never have become a land agent, and I most certainly should never have given evidence before any Commission.

In default of adequate land accommodation, I embarked on my profession by becoming assistant land agent to my brother-in-law, the Knight of Kerry, who was agent to Sir George Colthurst. I lived with the Knight at Inniscarra in County Cork, not far from Blarney.

From that time onward I worked steadily, and as I take my ease at the Carlton to-day, I really feel I have done as much honest labour in my career as has any man.

In proof I may cite a day's record some years later, taken almost at random from my diary.

I began with an hour in my Cork office, went by train to Killarney, a journey of three and a half hours, where I spent three hours in my office, and then by train on to Tralee, a further one and a quarter hours, where I had an hour and a half in my office in that town, and then drove out to Edenburn, seven miles, to sleep. That done fairly often makes a decided strain on endurance and mental concentration, because the affairs at each place were of course for different landlords and needed the memorising of a fresh section of business all absolutely intrusted to me, whilst the train service in Kerry then and now is not calculated to promote mental tranquillity or facilitate business.

Having alluded to my diary, I had better explain that I kept no journal until 1852, and subsequently to that year it consisted merely of bald memoranda of my movements; therefore it has not been of the least use in preparing these reminiscences.

In 1846 I became a Government Inspector of Land Improvements and Drainage Works, and in that capacity went to Bantry, where I saw the appalling destitution caused by the famine, with which I shall deal in the next chapter.

I had made application for this post before I left Kerry, directly I had found my farm too small for my requirements, and I received the appointment from the Chairman of the Irish Board of Works. Practically speaking the pay was about a pound a day with allowances.

This post in no way interfered with my duties as a land agent then, but I afterwards resigned it owing to the increasing exigencies of my profession.

It may be as well to detail for readers other than Irish what are the avocations of a land agent, especially as the class in Ireland will probably soon be as extinct as the dodo.

The duties of an Irish land agent comprise a great deal of office work, drawing up agreements with tenants, receiving rent, superintending agricultural and all landlords' improvements, sitting as magistrate and representing the landlord when the latter is absent at poor-law meetings, road sessions, and on grand juries.

With very rare exceptions the salary has been five per cent, on the rents received. So the agent has been paid five per cent, on all the money he has put into the landlord's pockets, whilst an architect has always received five per cent. on all he took out of them, an arrangement which in the latter instance has not worked at all well for the landlords.

The tendency has gradually been to consolidate and amalgamate land agencies, for as the difficulty of getting rents increased, more competent men of experience and judgment were needed by the landlords. As a proof of the trust reposed in me, I may mention that at one time I received the rents of one-fifth of the whole county of Kerry—and that in the worst times.

Such a task is not one to be envied, however joyously a man may take up the burden of his daily toil, and of course the agents as the outward and visible signs of the distant or absentee landlords obtained the greater share of the hatred felt for the latter.

In the worst period Lord Derby received threats that if he did not reduce his rents, his agent would be murdered.

He coolly replied:—

'If you think you will intimidate me by shooting my agent you are greatly mistaken.'

That is exactly the reply the agents desired the landlords to make, but it did not conduce to making their own existences any the more secure or enviable.

Of course in the due working out of the Wyndham Act, land agents will be utterly ruined.

There are no openings for them because they are too old to commence learning another profession, and they will not get employment under the County Council because they belong to the landlord class and have unflinchingly fought the battles of the landlords.

The agents are a class who have devoted their time and risked their lives in order to get in the rents due to their employers, and there is not the smallest chance—save in a few isolated and exceptional cases—of their being kept on when the landlords will have only their own demesne in their own hands and employ some underling, such as a bailiff in England, to collect the stray rents of the few cottagers who may still chance to be tenants.

Judge Ross stated that there was no more deserving or painstaking class in Ireland than the land agents, and he considered it a great hardship that under the Wyndham Act they obtain no compensation.

By agreement in most cases they receive three per cent. of the purchase money, but that is a very poor sinking fund to provide for a middle-aged gentleman, who has probably a family to support; and absolute bankruptcy must be the result if there is, as on several large properties, an agent with a couple of assistants.

When the Ashbourne Act was passed in 1885, it was never contemplated that the purchases would be on a wholesale scale. As a matter of fact only a few estates were sold, and on the purchase price of one of those for which I was agent I received two per cent. It should be also borne in mind that the profession of a land agent in Ireland is on a far higher social plane than in England. In many cases the younger son or brother of the landlord is the agent for the family property; and in some instances this has worked uncommonly well. In other cases, gentlemen by birth conducted the business, or else the administration of several estates was consolidated and carried on from one office.

In every case the billet was regarded as one for life, only forfeited by gross misconduct, and the relations between landlord and agent have been nearly always of an intimate and cordial character. Each agent began as an assistant, obtaining an independent post by selection and influence, and few entered the profession unless they had reasonable prospects of a definite post on their own account in due course.

In my time the landlord was the sole judge of the agent's qualifications, but the profession has become a branch of the Engineering Surveyor's Institution.

As may be imagined, there are now remarkably few candidates for the necessary examinations, because it is virtually annihilated.

Things were very different when I embarked without mistrust on a career which has landed me comfortably into my eighties, although under Government every appointment has to be compulsorily vacated at the age of sixty-five. No one starting now could anticipate any such result in old age, and so without affectation I can say autres temps autres moeurs, which may be freely translated as 'present times much the worst.'

More pleasant is it to turn to a few brief memories of Cork. It was a cheerful place at the time I am speaking of, for there was plenty of entertaining and truly genial hospitality. The general depression caused by famine, fever, and Fenians hardly affected the great town, and after those funereal shadows had once passed, Cork was as gay as any one could reasonably desire.

The townsfolk are very witty and clever at giving nicknames, as the following little tales will show.

When a citizen in Cork makes money, he generally builds a house, and the higher up the hill his house is situated, the more is thought of him.

Mr. Doneghan, a highly respectable tallow chandler, built a fine residence early in the nineteenth century, which he called Waterloo.

The populace said it should have been named Talavera (i.e. Tallow-vera), and as that it is known to this day.

Mr. Maguire, who was Member for Cork, and Lord Mayor of the City into the bargain, was very influential in the promotion of a gas company. With the money he made out of it, he reared a rather lofty mansion, which was promptly christened the Lighthouse.

All butter in Cork is sold at the wharves, and the casks are branded with the quality of the butter they contain. One man made a fortune out of the first class butter on its merits, and out of the sixth class butter, which he put in the first class casks and sold on the testimony of the brand on the wood. This became in time notorious to most people except the more unsophisticated of his clients, and when he embarked on bricks and mortar his house was generally known as Brandenburg.

One more and I have done with these baptismal sobriquets.

A lady on a Queenstown steamer had put her foot down the bunker's hole, and broke her ankle through the accident. She brought an action against the company, duly proved negligence on the part of the employés, and obtained substantial damages. These considerably assisted her in erecting a rather attractive mansion, which she decidedly resented being called Bunker's Hill.

Some people have their own ideas about the definition of a gentleman, as a certain rather diminutive racing man found to his cost.

It was at a meeting close to Cork, and he was standing next a burly farmer close to the rails when the horses were nearly ready to start.

Pointing to one disreputable-looking ruffian about to mount, he observed:—

'That fellow has no pretensions to be a gentleman-rider.'

The farmer caught him by the collar of his coat and the seat of his breeches, and shook him as a mastiff would a rat.

'Mind yourself, small man,' said he, 'that's a recognised gentleman in these parts.'

There was a mighty shindy, and when the farmer was told his victim was a prominent English peer, he retorted:—

'Well, that won't make him a judge of an Irish gentleman.'

In the last chapter I mentioned that the preacher I most admired was Archbishop Magee. I had the privilege of frequently hearing him in Cork, where he drew crowded congregations to a temporary church—the cathedral being under repair.

I never heard any one who so magnetised me from the pulpit, and I am by no means prone to admire sermons. There was a sort of mesmerism in the very eloquence of Magee which kept my eyes riveted on his lips—rather big, bulgy lips in an expressive, sensitive face. An hour beneath him sped marvellously fast, and more than once in Cork I have heard him preach for that length. The impression he made on me has never been effaced, and it was with no surprise I learnt in due course that he became Archbishop of York.

The late Lord Derby said that the most eloquent speech he ever heard in or out of the House of Lords was Magee's speech on the Church Act, the peroration of which—quoting from memory after many years—ran:—'My Lords, I will not, I cannot, and I dare not vote for that most unhallowed bill which lies on your Lordships' table.'

Have all Magee stories been told?

I am afraid so. Yet in the hope that a few may be new to some, though old to others—who are invited to skip them—here are just a small batch.

When he was a dean, he one day attended a debate on tithes in the House of Commons, and was subsequently putting on his overcoat, when a Radical Member courteously assisted him, whereupon he remarked:—

'I am very much obliged to you, sir, for reversing the policy of your friends inside, who are taking the coats off our backs.'

This was equalled by the wife of an Irish landlord who lost her purse in the Ladies' Gallery of the House of Commons.

Mrs. Gladstone, who had been sitting next her, after kindly assisting in the ineffectual search, observed:—

'I hope there was not much in it.'

'No, it was a nice little purse I had had for a long time, but thanks to your husband there was nothing in it.'

An Irish story of Magee's concerns an Orange clergyman in Fermanagh, who asked leave to preach a sermon by Magee. Now, this clergyman, who was an ambitious man, was rather ashamed of his mother, and would not let her live at the parsonage, but had taken lodgings for her in the town. Magee, moreover, always a moderate man, did not like Orange sermons, and most certainly had never composed one. As he good naturedly did not want to offend the other, he said he would give him a capital sermon to deliver if he—Magee—might select the text.

'Of course, of course,' assented the other; 'what is it?'

'"From that time His disciple took her to his own house."'

Even this was hardly so cutting as his remark, when a bishop, to a clergyman of whom he did not think highly, but who upbraided him for not giving him a living.

'Sir, if it were raining livings, the utmost I could do would be to lend you an umbrella.'

Mention of Magee suggests an ecclesiastical tale concerning a most convivial attorney—George Faith by name—who had rather a red nose, which he explained was caused by wearing tight boots.

His father in old age got married a second time, and George was asked why his stepmother was like Dr. Newman.

The answer was because she had embraced the ancient Faith.

Among old time Irish members, Joe Ronayne, M.P. for Cork, was among the most diverting.

He was a railway contractor, and much wanted some additional ground at the terminus of the line, which the proprietor, Lord Ventry, would not sell.

The size of the coveted patch was only seven feet long by three broad. Mr. Ronayne grimly retorted:—

'That's very strange, for it is exactly the amount of ground I'd like to give him,' i.e. for his grave.

Another experience of Ronayne's was to the following tune.

He had obtained advances from a local bank for his railway contract to the satisfaction of both parties, and when asked by the manager for some wrinkles about the making of a railway, replied:—

'The best thing is to run it into a soft bank.'

He was a plucky chap as well as a witty one, for owing to some internal malady, from which he died, he had to have his leg amputated, at the same time resigning his seat for Cork.

Addressing the surgeon, he observed:—

'I cannot stand for the borough any longer, but I shall certainly stump the constituency as a county candidate.'

Poor fellow, he was all too soon an accepted candidate for his passage over to the great majority.

A certain attorney named Nagle used to do most of his work.

Speaking of another attorney this Nagle remarked:—

'He has the heart of a vulture.'

'I know what's worse,' was Ronayne's comment.

'Indeed!'

'Yes; the bill of an aigle' (which is the broad Cork pronunciation of eagle).

This Nagle was not remarkable for the extent of his ablutions.

At one period, when he was becoming an ardent Radical, an obsequious toady said:—

'You'll become a second Marat.'

'There's no fear that he will die in the same place,' promptly came from Ronayne.

On another occasion the two were waiting for the judges outside their lodgings during the Assizes.

Suddenly Ronayne, in the hearing of a number of acquaintances, called out:—

'You had better come away at once, Nagle.'

'Why should I?' indignantly.

'If you stop five minutes longer there's a shower of rain coming on and you might get washed.'

On a third occasion, Nagle told Ronayne he was going to invest some money in a mining exploration.

'Explore your own landed property, my dear fellow,' was Ronayne's advice.

'But you know I have not got any.'

'Good Heavens, you don't mean to say you have cleaned your nails?'

Though he was an out-and-out Fenian, Ronayne was as honest a man as I ever met, and he was considered one of the most amusing men in the House of Commons.

The attorneys in Cork at one time formed quite a small coterie, who divided all the business until it grew too much for them, one, Mr. Paul Wallace, being especially harassed with briefs.

At length a barrister named Graves came down from Dublin, and was introduced to Wallace by another attorney with the remark:—

'Counsel are very necessary.'

'Yes,' said Wallace; 'as a matter of fact, we are all being driven to our graves.'

At Kanturk Sessions, Mr. Philip O'Connell was consulted by a client about the recovery of a debt. He at once saw that the defence would be a pleading of the statute of limitations, so he told his client that if he could get a man to swear that the debtor had admitted the debt within the last six years, he would succeed, but not otherwise.

O'Connell went off to take the chair at a Bar dinner to a new County Court judge.

As the dessert was being set on the table, a loud knock came at the door, which was immediately behind the chairman.

'What is it?' cried O'Connell.

A head appeared, and the voice from it explained:—

'I'm Tim Flaherty, your honour, as was consulting you outside, and I want you to come this way for a while.'

'Don't you see I am engaged and cannot come?'

'But it's pressing and important.'

'I tell you I won't come.'