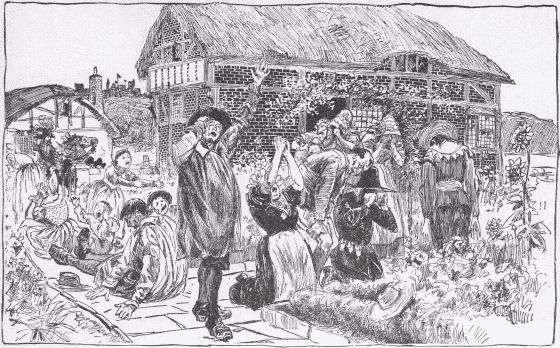

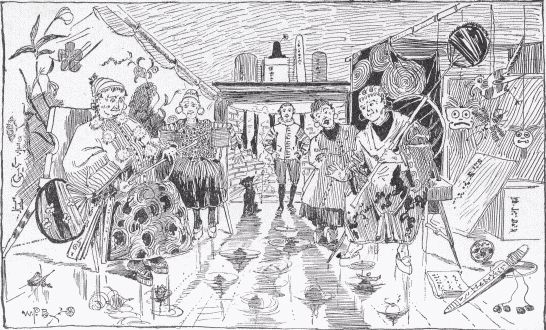

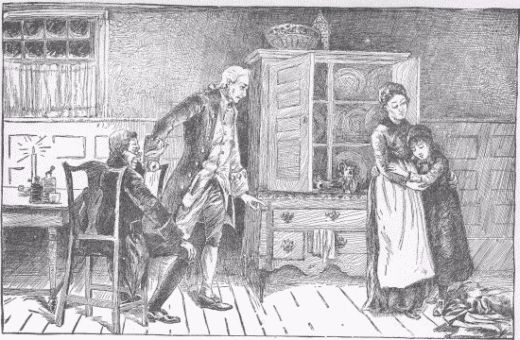

FLAX LOOKS INTO THE POT OF GOLD.

Title: The Pot of Gold, and Other Stories

Author: Mary Eleanor Wilkins Freeman

Release date: August 7, 2005 [eBook #16468]

Most recently updated: December 12, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Ted Garvin, Lesley Halamek and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

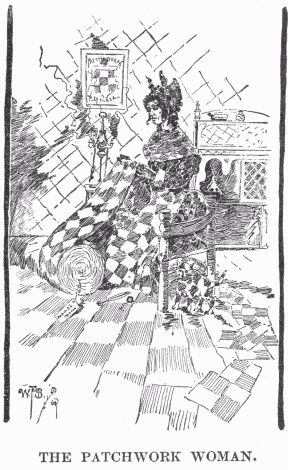

frontispiece

FLAX LOOKS INTO THE POT OF GOLD.

The Flower family lived in a little house in a broad grassy meadow, which sloped a few rods from their front door down to a gentle, silvery river. Right across the river rose a lovely dark green mountain, and when there was a rainbow, as there frequently was, nothing could have looked more enchanting than it did rising from the opposite bank of the stream with the wet, shadowy mountain for a background. All the Flower family would invariably run to their front windows and their door to see it.

The Flower family numbered nine: Father and Mother Flower and seven children. Father Flower was an unappreciated poet, Mother Flower was very much like all mothers, and the seven children were very sweet and interesting. Their first names all matched beautifully with their last name, and with their personal appearance. For instance, the oldest girl, who had soft blue eyes and flaxen curls, was called Flax Flower; the little boy, who came next, and had[Page 12] very red cheeks and loved to sleep late in the morning, was called Poppy Flower, and so on. This charming suitableness of their names was owing to Father Flower. He had a theory that a great deal of the misery and discord in the world comes from things not matching properly as they should; and he thought there ought to be a certain correspondence between all things that were in juxtaposition to each other, just as there ought to be between the last two words of a couplet of poetry. But he found, very often, there was no correspondence at all, just as words in poetry do not always rhyme when they should. However, he did his best to remedy it. He saw that every one of his children's names were suitable and accorded with their personal characteristics; and in his flower-garden—for he raised flowers for the market—only those of complementary colors were allowed to grow in adjoining beds, and, as often as possible, they rhymed in their names. But that was a more difficult matter to manage, and very few flowers were rhymed, or, if they were, none rhymed correctly. He had a bed of box next to one of phlox, and a trellis of woodbine grew next to one of eglantine, and a thicket of elder-blows was next to one of rose; but he was forced to let his violets and honeysuckles and many others go entirely unrhymed—this disturbed him considerably, but he reflected that it was not his fault, but that of the man who made the language and named the different[Page 13] flowers—he should have looked to it that those of complementary colors had names to rhyme with each other, then all would have been harmonious and as it should have been.

Father Flower had chosen this way of earning his

livelihood when he realized that he was doomed to be

an unappreciated poet, because it suited so well with

his name; and if the flowers had only rhymed a little

better he would have been very well contented. As it

was, he never grumbled. He also saw to it that the

furniture in his little house and the cooking utensils

rhymed as nearly as possible, though that too was

oftentimes a difficult matter to bring about, and required

a vast deal of thought and hard study. The

table always stood under the gable end of the roof, the

foot-stool always stood where it was cool, and the big

rocking-chair in a glare of sunlight; the lamp, too, he

kept down cellar where it was damp. But all these

were rather far-fetched, and sometimes quite inconvenient.

Occasionally there would be an article that

he could not rhyme until he had spent years of thought

over it, and when he did it would disturb the comfort

of the family greatly. There was the spider. He

puzzled over that exceedingly, and when he rhymed it

at last, Mother Flower or one of the little girls had

always to take the spider beside her, when she sat

[Page 14]

down, which was of course quite troublesome.

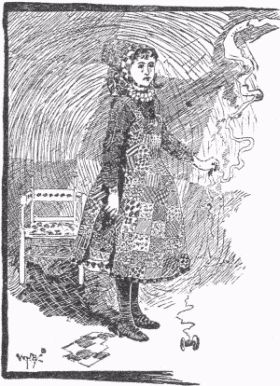

[plate 2]

The kettle he rhymed first with nettle, and hung a bunch

of nettle over it, till all the children got dreadfully

stung. Then he tried settle, and hung the kettle over

the settle. But that was no place for it; they had to

go without their tea, and everybody who sat on the settle bumped

his head against the kettle. At last it occurred to Father Flower

that if he should make a slight change in the language the kettle

could rhyme with the skillet, and sit beside it on the stove, as it ought,

leaving harmony out of the question, to do. Accordingly all the

children were instructed to call the skillet a skettle,

and the kettle stood by its side on the stove ever

afterward.

The kettle he rhymed first with nettle, and hung a bunch

of nettle over it, till all the children got dreadfully

stung. Then he tried settle, and hung the kettle over

the settle. But that was no place for it; they had to

go without their tea, and everybody who sat on the settle bumped

his head against the kettle. At last it occurred to Father Flower

that if he should make a slight change in the language the kettle

could rhyme with the skillet, and sit beside it on the stove, as it ought,

leaving harmony out of the question, to do. Accordingly all the

children were instructed to call the skillet a skettle,

and the kettle stood by its side on the stove ever

afterward.

The house was a very pretty one, although it was quite rude and very simple. It was built of logs and[Page 15] had a thatched roof, which projected far out over the walls. But it was all overrun with the loveliest flowering vines imaginable, and, inside, nothing could have been more exquisitely neat and homelike; although there was only one room and a little garret over it. All around the house were the flower-beds and the vine-trellises and the blooming shrubs, and they were always in the most beautiful order. Now, although all this was very pretty to see, and seemingly very simple to bring to pass, yet there was a vast deal of labor in it for some one; for flowers do not look so trim and thriving without tending, and houses do not look so spotlessly clean without constant care. All the Flower family worked hard; even the littlest children had their daily tasks set them. The oldest girl, especially, little Flax Flower, was kept busy from morning till night taking care of her younger brothers and sisters, and weeding flowers. But for all that she was a very happy little girl, as indeed were the whole family, as they did not mind working, and loved each other dearly.

Father Flower, to be sure, felt a little sad sometimes; for, although his lot in life was a pleasant one, it was not exactly what he would have chosen. Once in a while he had a great longing for something different. He confided a great many of his feelings to Flax Flower; she was more like him than any of the other children, and could understand him even better than[Page 16] his wife, he thought.

One day, when there had been a heavy shower and a beautiful rainbow, he and Flax were out in the garden tying up some rose-bushes, which the rain had beaten down, and he said to her how he wished he could find the Pot of Gold at the end of the rainbow. Flax, if you will believe me, had never heard of it; so he had to tell her all about it, and also say a little poem he had made about it to her.

The poem ran something in this way:

O what is it shineth so golden-clear

At the rainbow's foot on the dark green hill?

'Tis the Pot of Gold, that for many a year

Has shone, and is shining and dazzling still.

And whom is it for, O Pilgrim, pray?

For thee, Sweetheart, should'st thou go that way.

Flax listened with her soft blue eyes very wide open. "I suppose if we should find that pot of gold it would make us very rich, wouldn't it, father?" said she.

"Yes," replied her father; "we could then have a grand house, and keep a gardener, and a maid to take care of the children, and we should no longer have to work so hard." He sighed as he spoke, and tears stood in his gentle blue eyes, which were very much like Flax's. "However, we shall never find it," he added.

"Why couldn't we run ever so fast when we saw[Page 17] the rainbow," inquired Flax, "and get the Pot of Gold?"

"Don't be foolish, child!" said her father; "you could not possibly reach it before the rainbow was quite faded away!"

"True," said Flax, but she fell to thinking as she tied up the dripping roses.

The next rainbow they had she eyed very closely, standing out on the front door-step in the rain, and she saw that one end of it seemed to touch the ground at the foot of a pine-tree on the side of the mountain, which was quite conspicuous amongst its fellows, it was so tall. The other end had nothing especial to mark it.

"I will try the end where the tall pine-tree is first," said Flax to herself, "because that will be the easiest to find—if the Pot of Gold isn't there I will try to find the other end."

A few days after that it was very hot and sultry, and at noon the thunder heads were piled high all around the horizon.

"I don't doubt but we shall have showers this afternoon," said Father Flower, when he came in from the garden for his dinner.

After the dinner-dishes were washed up, and the baby rocked to sleep, Flax came to her mother with a petition.

"Mother," said she, "won't you give me a holiday[Page 18] this afternoon?"

"Why, where do you want to go, Flax?" said her mother.

"I want to go over on the mountain and hunt for wild flowers," replied Flax.

"But I think it is going to rain, child, and you will get wet."

"That won't hurt me any, mother," said Flax, laughing.

"Well, I don't know as I care," said her mother, hesitatingly. "You have been a very good industrious girl, and deserve a little holiday. Only don't go so far that you cannot soon run home if a shower should come up."

So Flax curled her flaxen hair and tied it up with a blue ribbon, and put on her blue and white checked dress. By the time she was ready to go the clouds over in the northwest were piled up very high and black, and it was quite late in the afternoon. Very likely her mother would not have let her gone if she had been at home, but she had taken the baby, who had waked from his nap, and gone to call on her nearest neighbor, half a mile away. As for her father, he was busy in the garden, and all the other children were with him, and they did not notice Flax when she stole out of the front door. She crossed the river on a pretty arched stone bridge nearly opposite the house, and went directly into the woods on the side of the[Page 19] mountain.

Everything was very still and dark and solemn in the woods. They knew about the storm that was coming. Now and then Flax heard the leaves talking in queer little rustling voices. She inherited the ability to understand what they said from her father. They were talking to each other now in the words of her father's song. Very likely he had heard them saying it sometime, and that was how he happened to know i t,

"O what is it shineth so golden-clear

At the rainbow's foot on the dark green hill?"

Flax heard the maple leaves inquire. And the pine-leaves answered back:

"'Tis the Pot of Gold, that for many a year

Has shone, and is shining and dazzling still."

Then the maple-leaves asked:

"And whom is it for, O Pilgrim, pray?"

And the pine-leaves answered:

"For thee, Sweetheart, should'st thou go that way."

Flax did not exactly understand the sense of the last question and answer between maple and pine-leaves. But they kept on saying it over and over as she ran along. She was going straight to the tall pine-tree. She knew just where it was, for she had [Page 20] often been there. Now the rain-drops began to splash through the green boughs, and the thunder rolled along the sky. The leaves all tossed about in a strong wind and their soft rustles grew into a roar, and the branches and the whole tree caught it up and called out so loud as they writhed and twisted about that Flax was almost deafened, the words of the song:

"O what is it shineth so golden-clear?"

Flax sped along through the wind and the rain and the thunder. She was very much afraid that she should not reach the tall pine which was quite a way distant before the sun shone out, and the rainbow came.

The sun was already breaking through the clouds when she came in sight of it, way up above her on a rock. The rain-drops on the trees began to shine like diamonds, and the words of the song rushed out from their midst, louder and sweeter:

"O what is it shineth so golden-clear?"

Flax climbed for dear life. Red and green and golden rays were already falling thick around her, and at the foot of the pine-tree something was shining wonderfully clear and bright.

At last she reached it, and just at that instant the rainbow became a perfect one, and there at the foot of the wonderful arch of glory was the Pot of Gold.[Page 21] Flax could see it brighter than all the brightness of the rainbow. She sank down beside it and put her hand on it, then she closed her eyes and sat still, bathed in red and green and violet light—that, and the golden light from the Pot, made her blind and dizzy. As she sat there with her hand on the Pot of Gold at the foot of the rainbow, she could hear the leaves over her singing louder and louder, till the tones fairly rushed like a wind through her ears. But this time they only sang the last words of the song:

"And whom is it for, O Pilgrim, pray?

For thee, Sweetheart, should'st thou go that way."

At last she ventured to open her eyes. The rainbow had faded almost entirely away, only a few tender rose and green shades were arching over her; but the Pot of Gold under her hand was still there, and shining brighter than ever. All the pine needles with which the ground around it was thickly spread, were turned to needles of gold, and some stray couplets of leaves which were springing up through them were all gilded.

Flax bent over it trembling and lifted the lid off the pot. She expected, of course, to find it full of gold pieces that would buy the grand house and the gardener and the maid that her father had spoken about. But to her astonishment, when she had lifted the lid off and bent over the Pot to look into it, the first thing[Page 22] she saw was the face of her mother looking out of it at her. It was smaller of course, but just the same loving, kindly face she had left at home. Then, as she looked longer, she saw her father smiling gently up at her, then came Poppy and the baby and all the rest of her dear little brothers and sisters smiling up at her out of the golden gloom inside the Pot. At last she actually saw the garden and her father in it tying up the roses, and the pretty little vine-covered house, and, finally, she could see right into the dear little room where her mother sat with the baby in her lap, and all the others around her.

Flax jumped up. "I will run home," said she, "it is late, and I do want to see them all dreadfully."

So she left the Golden Pot shining all alone under the pine-tree, and ran home as fast as she could.

When she reached the house it was almost twilight, but her father was still in the garden. Every rose and lily had to be tied up after the shower, and he was but just finishing. He had the tin milk pan hung on him like a shield, because it rhymed with man. It certainly was a beautiful rhyme, but it was very inconvenient. Poor Mother Flower was at her wits' end to know what to do without it, and it was very awkward for Father Flower to work with it fastened to him.

Flax ran breathlessly into the garden, and threw her arms around her father's neck and kissed him. She bumped her nose against the milk pan, but she did not[Page 23] mind that; she was so glad to see him again. Somehow, she never remembered being so glad to see him as she was now since she had seen his face in the Pot of Gold.

"Dear father," cried she, "how glad I am to see you! I found the Pot of Gold at the end of the rainbow!"

Her father stared at her in amazement.

"Yes, I did, truly, father," said she. "But it was not full of gold, after all. You was in it, and mother and the children and the house and garden and—everything."

"You were mistaken, dear," said her father, looking at her with his gentle, sorrowful eyes. "You could not have found the true end of the rainbow, nor the true Pot of Gold—that is surely full of the most beautiful gold pieces, with an angel stamped on every one."

"But I did, father," persisted Flax.

"You had better go into your mother, Flax," said her father; "she will be anxious to see you. I know better than you about the Pot of Gold at the end of the rainbow."

So Flax went sorrowfully into the house. There was the tea-kettle singing beside the "skettle," which had some nice smelling soup in it, the table was laid for supper, and there sat her mother with the baby in her lap and the others all around her—just as they[Page 24] had looked in the Pot of Gold.

Flax had never been so glad to see them before—and if she didn't hug and kiss them all!

"I found the Pot of Gold at the end of the rainbow, mother," cried she, "and it was not full of gold, at all; but you and father and the children looked out of it at me, and I saw the house and garden and everything in it."

Her mother looked at her lovingly. "Yes, Flax dear," said she.

"But father said I was mistaken," said Flax, "and did not find it."

"Well, dear," said her mother, "your father is a poet, and very wise; we will say no more about it. You can sit down here and hold the baby now, while I make the tea."

Flax was perfectly ready to do that; and, as she sat there with her darling little baby brother crowing in her lap, and watched her pretty little brothers and sisters and her dear mother, she felt so happy that she did not care any longer whether she had found the true Pot of Gold at the end of the rainbow or not.

But, after all, do you know, I think her father was mistaken, and that she had.

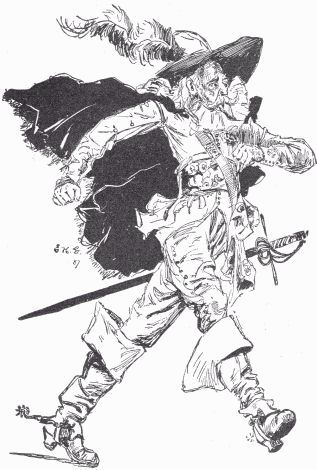

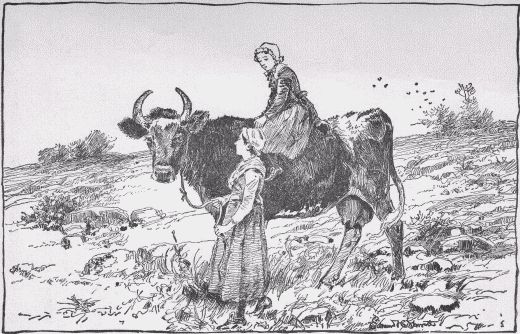

Once there was a farmer who had a very rare and valuable cow. There was not another like her in the whole kingdom. She was as white as the whitest lily you ever saw, and her horns, which curved very gracefully, were of gold.

She had a charming green meadow, with a silvery pool in the middle, to feed in. Almost all the grass was blue-eyed grass, too, and there were yellow lilies all over the pool.

The farmer's daughter, who was a milkmaid, used to tend the gold-horned cow. She was a very pretty girl. Her name was Drusilla. She had long flaxen hair, which hung down to her ankles in two smooth braids, tied with blue ribbons. She had blue eyes and pink cheeks, and she wore a blue petticoat, with garlands of rose-buds all over it, and a white dimity short gown, looped up with bunches of roses. Her hat was a straw flat, with a wreath of rose-buds around it, and she always carried a green willow branch in her hand to drive the cow with.

She used to sit on a bank near the silvery pool, and watch the gold-horned cow, and sing to herself all day from the time the dew was sparkling over the meadow[Page 26] in the morning, till it fell again at night. Then she would drive the cow gently home, with her green willow stick, milk her, and feed her, and put her into her stable, herself, for the night.

The farmer was feeble and old, so his daughter had to do all this. The gold-horned cow's stable was a sort of a "lean-to," built into the side of the cottage where Drusilla and her father lived. Its roof, as well as that of the cottage, was thatched and overgrown with moss, out of which had grown, in its turn, a little starry white flower, until the whole roof looked like a flower-bed. There were roses climbing over the walls of the cottage and stable, also, pink and white ones.

Drusilla used to keep the gold-horned cow's stable in exquisite order. Her trough to eat out of, was polished as clean as a lady's china tea-cup. She always had fresh straw, and her beautiful long tail was tied by a blue ribbon to a ring in the ceiling, in order to keep it nice.

[plate 3]

DRUSILLA AND HER GOLD-HORNED COW.

The gold-horned cow's milk was better than any other's, as one would reasonably suppose it to have been. The cream used to be at least an inch thick, and so yellow; and the milk itself had a peculiar and exquisite flavor—perhaps the best way to describe it, is to say it tasted as lilies smell. The gentry all about were eager to buy it, and willing to pay a good price for it. Drusilla used to go around to supply her customers, nights and mornings, a bright, shining milk-pail[Page 29] in each hand, and one on her head. She had learned to carry herself so steadily in consequence that she walked like a queen.

Everybody admired Drusilla, and all the young shepherds and farmers made love to her, but she did not seem to care for any of them, but to prefer tending her gold-horned cow, and devoting herself to her old father—she was a very dutiful daughter.

Everything went prosperously with them for a long time; the cow thrived, and gave a great deal of milk, customers were plenty, they paid the rent for their cottage regularly, and Drusilla who was a beautiful spinner, had her linen chest filled to the brim with the finest linen.

At length, however, a great misfortune befell them. One morning—it was the day after a holiday—Drusilla, who had been up very late the night before dancing on the village green, felt very sleepy, as she sat watching the cow in the green meadow. So she just laid her flaxen head down amongst the blue-eyed grasses, and soon fell fast asleep.

When she woke up, the dew was all dried off, and the sun almost directly overhead. She rubbed her eyes, and looked about for the gold-horned cow. To her great alarm, she was nowhere to be seen. She jumped up, distractedly, and ran over the meadow, but the gold-horned cow was certainly not there. The bars were up, just as she had left them, and there was not[Page 30] a gap in the stonewall which extended around the meadow. How could she have gotten out? It was very mysterious!

Drusilla, when she found, certainly, that the gold-horned cow was gone, lost no time in wonderment and conjecture; she started forth to find her. "I will not tell father till I have searched a long time," said she to herself.

So, down the road she went, looking anxiously on either side. "If only I could come in sight of her, browsing in the clover, beside the wall," sighed she; but she did not.

After a while, she saw a great cloud of dust in the distance. It rolled nearer and nearer, and finally she saw the King on horseback, with a large party of nobles galloping after him. The King, who was quite an old man, had a very long, curling, white beard, and had his breast completely covered with orders and decorations. No convenient board fence on a circus day was ever more thoroughly covered with elephants and horses, and trapeze performers, than the breast of the King's black velvet coat with jeweled stars and ribbons. But even then, there was not room for all his store, so he had hit upon the ingenious expedient of covering a black silk umbrella with the remainder. He held it in a stately manner over his head now, and it presented a dazzling sight; for it was literally blazing with gems, and glittering ribbons fluttered from it [Page 31] on all sides.

When the King saw Drusilla courtesying by the side of the road, he drew rein so suddenly, that his horse reared back on its haunches, and all his nobles, who always made it a point to do exactly as the King did—it was court etiquette—also drew rein suddenly, and all their horses reared back on their haunches.

"What will you, pretty maiden?" asked the King graciously.

"Please, your Majesty," said Drusilla courtesying and blushing and looking prettier than ever, "have you seen my gold-horned cow?"

"Pardy," said the King, for that was the proper thing for a King to say, you know, "I never saw a gold-horned cow in my life!"

Then Drusilla told him about her loss, and the King gazed at her while she was talking, and admired her more and more.

You must know that it had always been a great cross to the King and his wife, the Queen, that they had never had any daughter. They had often thought of adopting one, but had never seen any one who exactly suited them. They wanted a full-grown Princess, because they had an alliance with the Prince of Egypt in view.

The King looked at Drusilla now, and thought her the most beautiful and stately maiden he had ever seen.

"What an appropriate Princess she would make!"[Page 32] thought he.

"Suppose I should find the gold-horned cow for you," said he to Drusilla, when she had finished her pitiful story, "would you consent to be adopted by the Queen and myself, and be a princess?"

Drusilla hesitated a moment. She thought of her dear old father and how desolate he would be without her. But then she thought how terribly distressed he would be at the loss of the gold-horned cow, and that if he had her back, she would be company for him, even if his daughter was away, and she finally gave her consent.

The King always had his Lord Chamberlain lead a white palfrey, with rich housings, by the bridle, in case they came across a suitable full-grown Princess in any of their journeys; and now he ordered him to be brought forward, and commanded a page to assist Drusilla to the saddle.

But she began to weep. "I want to go back to my father, until you have found the cow, your Majesty," said she.

"You may go and bid your father good-by," replied the King, peremptorily, "but then you must go immediately to the boarding school, where all the young ladies of the Court are educated. If you are going to be a Princess, it is high time you began to prepare. You will have to learn feather stitching, and rick-rack and Kensington stitch, and tatting, and point lace, and[Page 33] Japanese patchwork, and painting on china, and how to play variations on the piano, and—everything a Princess ought to know."

"But," said Drusilla timidly, "suppose—your Majesty shouldn't—find the cow"—

"Oh! I shall find the cow fast enough," replied the King carelessly. "Why, I shall have the whole Kingdom searched. I can't fail to find her." So the page assisted the milkmaid to the saddle, kneeling gracefully, and presenting his hand for her to place her foot in, and they galloped off toward the farmer's cottage.

The old man was greatly astonished to see his daughter come riding home in such splendid company, and when she explained matters to him, his distress, at first, knew no bounds. To lose both his dear daughter and his precious gold-horned cow, at one blow, seemed too much to bear. But the King promised to provide liberally for him during his daughter's absence, and spoke very confidently of his being able to find the cow. He also promised that Drusilla should return to him if the cow was not found in one year's time, and after a while the old man was pacified.

Drusilla put her arms around her father's neck and kissed him tenderly; then the page assisted her gracefully into the saddle, and she rode, sobbing, away.

After they had ridden about an hour, they came to a large, white building.

"O dear!" said the King, "the seminary is asleep![Page 34] I was afraid of it!"

Then Drusilla saw that the building was like a great solid mass, with not a door or window visible.

"It is asleep," explained the King. "It is not a common house; a great professor designed it. It goes to sleep, and you can't see any doors or windows, and such work as it is to wake it up! But we may as well begin."

Then he gave a signal, and all the nobles shouted as loud as they possibly could, but the seminary still remained asleep.

"It's asleep most of the time!" growled the King. "They don't want the young ladies disturbed at their feather stitching and rick-rack, by anything going on outside. I wish I could shake it."

Then he gave the signal again, and all the nobles shouted together, as loud as they could possibly scream. Suddenly, doors and windows appeared all over the seminary, like so many opening eyes.

"There," cried the King, "the seminary has woke up, and I am glad of it!"

Then he ushered Drusilla in, and introduced her to the lady principal and the young ladies, and she was at once set to making daisies in Kensington stitch, for the King was very anxious for her education to begin at once.

So now, the milkmaid, instead of sitting, singing, in a green meadow, watching her beautiful gold-horned[Page 35] cow, had to sit all day in a high-backed chair, her feet on a little foot-stool with an embroidered pussy cat on it, and do fancy work. The young ladies worked by electric light; for the seminary was asleep nearly all the time, and no sunlight could get in at the windows, for boards clapped down over them like so many eye-lids when the seminary began to doze.

Drusilla had left off her pretty blue petticoat and white short gown now, and was dressed in gold-flowered satin, with an immense train, which two pages bore for her when she walked. Her pretty hair was combed high and powdered, and she wore a comb of gold and pearls in it. She looked very lovely, but she also looked very sad. She could not help thinking, even in the midst of all this splendor, of her dear father, and her own home, and wishing to see them.

She was a very apt pupil. Her tatting collars were the admiration of the whole seminary, and she made herself a whole dress of rick-rack. She painted a charming umbrella stand for the King, and actually worked the gold-horned cow in Kensington stitch, on a blue satin tidy, for the Queen. It was so natural that she wept over it, herself, when it was finished; but the Queen was delighted, and put it on her best stuffed rocking-chair in her parlor, and would run and throw it back every time the King sat down there, for fear he would lean his head against it and soil it.

Drusilla also worked an elegant banner of old gold[Page 36] satin, with hollyhocks, for the King to carry at the head of his troops when he went to battle; also a hat-band for the Prince of Egypt. This last was sent by a special courier with a large escort, and the Prince sent an exquisite shopping-bag of real alligator's skin to Drusilla in return. She was the envy of the whole seminary when it came.

The young ladies fared very delicately. Their one article of diet was peaches and cream. It was thought to improve their complexions. Once in a while, they went out to drive by moonlight; they were afraid of sunburn by day, and they wore white gauze veils, even in the moonlight, and they all had embroidered afghans of their own handiwork.

They used to sit around a large table over which hung a chandelier of the electric light, to work, and some young lady either played "Home, sweet Home, and variations," or else "The Maiden's Prayer," on the piano for their entertainment.

It seemed as if Drusilla ought to have been happy in a place like this; but although she was diligent and dutiful, she grieved all the time for her father.

Meantime, the King was keeping up an energetic search for the gold-horned cow. Every stable and pasture in the Kingdom was searched, spies were posted everywhere, but the King could not find her. She had disappeared as completely as if she had vanished altogether from the face of the earth. It at last [Page 37] began to be whispered about that there never had been any gold-horned cow, but that the whole had been a clever trick of Drusilla's, that she might become a Princess. An envious schoolmate, who had been very desirous of becoming Princess and marrying the Prince of Egypt herself, started the report; and it soon spread over the whole Kingdom. The King heard it and began to believe it; for he could not see why he failed to find the cow. It always exasperated the King dreadfully to fail in anything, and he never allowed that it was his own fault, if he could possibly help it.

At last the end of the year came, and still no signs of the gold-horned cow. Then the King became convinced that Drusilla had cheated him, that there never had been any such wonderful cow, and that she had used this trick in order to become a Princess. Of course, the King felt more comfortable to believe this, for it accounted satisfactorily for his own failure to find her, and it is extremely mortifying for a King to be unable to do anything he sets out to.

So Drusilla was dismissed from the seminary in disgrace, and sent home. Her jewels and fine clothes were all taken away from her, even her rick-rack dress, and she put on her blue petticoat and short gown, and straw flat again. Still, she was so happy at the prospect of seeing her dear old father again, that she did not mind the loss of all her fine things much. She[Page 38] did not ride the white palfrey now, but went home on foot, in the dewy morning, as fast as she could trip.

When she came in sight of the cottage, there was her father sitting in his old place at the window. When he saw his beloved daughter coming, he ran out to meet her as fast as he could hobble, and they tenderly embraced each other.

The King had provided liberally for the old man while Drusilla was in the seminary, but now that he was so angry at her alleged deception, his support would probably cease, and, since the gold-horned cow was lost, it was a question how they would live. The father and daughter sat talking it over after they had entered the cottage. It was a puzzling question, and Drusilla was weeping a little, when her father gave a joyful cry:

"Look, look, Drusilla!"

Drusilla looked up quickly, and there was the milk-white face and golden horns of the cow peering through the vines in the window. She was eating some of the pink and white roses.

Drusilla and her father hastened out with joyful exclamations, and there was the cow, sure enough. A couple of huge wicker baskets were slung across her broad back, and one was filled to the brim with gold coins, and the other with jewels, diamonds, pearls and rubies.

When Drusilla and her father saw them, they both[Page 39] threw their arms around the gold-horned cow's neck, and cried for joy. She turned her head and gazed at them a moment with her calm, gentle eyes; then she went on eating roses.

When the King heard of all this, he came with the Queen in a golden coach, to see Drusilla and her father. "I am convinced now of your truthfulness," he said majestically, when the Court Jeweler had examined the cow's horns to see if they were true gold, and not merely gilded, and he had seen with his own eyes the two baskets full of coins and jewels. "And, if you would like to be Princess, you can be, and also marry the Prince of Egypt."

But Drusilla threw her arms around her father's neck. "No; your Majesty," she said timidly, "I had rather stay with my father, if you please, than be a Princess, and I rather live here and tend my dear cow, than marry the Prince of Egypt."

The King sighed, and so did the Queen; they knew they never should find another such beautiful Princess. But, then, the King had not kept his part of the contract and found the gold-horned cow, and he could not compel her to be a Princess without breaking the royal word.

So the cow was again led out to pasture in the little meadow of blue-eyed grasses, and Drusilla, though she was very rich now, used to find no greater happiness than to sit on the banks of the silvery pool where the[Page 40] yellow lilies grew, and watch her.

They had their poor little cottage torn down and a grand castle built instead: but the roof of that was thatched and over-grown with moss, and pink and white roses clustered thickly around the walls. It was just as much like their old home as a castle can be like a cottage. The gold-horned cow had, also, a magnificent new stable. Her eating-trough was the finest moss rose-bud china, she had dried rose leaves instead of hay to eat, and there were real lace curtains at all the stable windows, and a lace portière over her stall.

The King and Queen used to visit Drusilla often; they gave her back her rick-rack dress, and grew very fond of her, though she would not be a Princess. Finally, however, they prevailed upon her to be made a countess. So she was called "Lady Drusilla," and she had a coat of arms, with the gold-horned cow rampant on it, put up over the great gate of the castle.

The Bee Festival was held on the sixteenth day of May; all the court went. The court-ladies wore green silk scarfs, long green floating plumes in their bonnets, and green satin petticoats embroidered with apple-blossoms. The court-gentlemen wore green velvet tunics with nose-gays in their buttonholes, and green silk hose. Their little pointed shoes were adorned with knots of flowers instead of buckles.

As for the King himself, he wore a thick wreath of cherry and peach-blossoms instead of his crown, and carried a white thorn-branch instead of his scepter. His green velvet robe was trimmed with a border of blue and white violets instead of ermine. The Queen wore a garland of violets around her golden head, and the hem of her gown was thickly sown with primroses.

But the little Princess Rosetta surpassed all the rest. Her little gown was completely woven of violets and other fine flowers. There was a very skillful seamstress in the court who knew how to do this kind[Page 42] of work, although no one except the Princess Rosetta was allowed to wear a flower-cloth gown to the Bee Festival. She wore also a little white violet cap, and two of her nurses carried her between them in a little basket lined with rose and apple-leaves.

All the company, as they danced along, sang, or played on flutes, or rang little glass and silver bells. Nobody except the King and Queen rode. They rode cream-colored ponies, with silken ropes wound with flowers for bridle-reins.

The Bee Festival was held in a beautiful park a mile distant from the city. The young grass there was green and velvety, and spangled all over with fallen apple and cherry and peach and plum and pear blossoms; for the park was set with fruit-trees in even rows. The blue sky showed between the pink and white branches, and the air was very sweet and loud with the humming of bees. The trees were all full of bees. There was something peculiar about the bees of this country; none of them had stings.

When the court reached the park, they all tinkled their bells in time, whistled on their flutes, and sang a song which they always sang on these occasions. Then they played games and enjoyed themselves. They played hide-and-seek among the trees, and formed rings and danced. The bees flew around them, and seemed to know them. The little Princess, lying in her basket, crowed and laughed, and caught at them[Page 43] when they came humming over her face. Her nurses stood around her, and waved great fans of peacock-feathers, but that did not frighten the bees at all.

The court's lunch was spread on a damask-cloth, in an open space between the trees. There were biscuits of wheaten flour, plates of honey-comb, and cream in tall glass ewers. That was the regulation lunch at the Bee Festival. The Bee Festival was nearly as old as the kingdom, and there was an ancient legend about it, which the Poet Laureate had put into an epic poem. The King had it in his royal library, printed in golden letters and bound in old gold plush.

Centuries ago, so the legend ran, in the days of the very first monarch of the royal family of which this king was a member, there were no bees at all in the kingdom. Not a child in the whole country, not even the little princes and princesses in the palace, had ever tasted a bit of bread and honey.

But, while there were no bees in this kingdom, one just across the river was swarming with them. That kingdom was governed by a king who was the tenth cousin of the first, and not very well disposed toward him. He had stationed lines of sentinels with ostrich-feather brooms on his bank of the river to keep the bees from flying over, and he would not export a single bee, nor one ounce of honey, although he had been offered immense sums.

However, the inhabitants of this second country[Page 44] were so cruel and tormenting in their dispositions, and the children so teased the bees, which were stingless and could not defend themselves, that they rebelled. They stopped making honey, and one day they swarmed, and flew in a body across the river in spite of the frantic waving of the ostrich-feather brooms.

The other King was overjoyed. He ordered beautiful hives to be built for them, and instituted a national festival in their honor, which ever since had been observed regularly on the sixteenth day of May.

Up to this day there were no bees in the kingdom across the river. Not one would return to where its ancestors had been so hardly treated; here everybody was kind to them, and even paid them honor. The present King had established an order of the "Golden Bee." The Knights of the Golden Bee wore ribbons studded with golden bees on their breasts, and their watchword was a sort of a "buzz-z-z," like the humming of a bee. When they were in full regalia they wore also some curious wings made of gold wire and lace. The Knights of the Golden Bee comprised the finest nobles of the court.

In addition to them were the "Bee Guards." They were the King's own body-guards. Their uniform was white with green cuffs and collar and facings. On the green were swarms of embroidered bees. They carried a banner of green silk worked with bees and roses.

So the bee might fairly have been considered the[Page 45]

national emblem of Romalia, for that was the name of

the country. The first word which the children

[plate 4]

learned to spell in school was "b-e-e, bee," instead of

"b-o-y, boy." The poorest citizen had a bush of roses

and a bee-hive in his yard, and the people were very forlorn

who could not have a bit of honey-comb at least once a day.

The court preferred it to any other food. Indeed it was this

particular Queen who was in the kitchen eating bread and honey,

in the song.

learned to spell in school was "b-e-e, bee," instead of

"b-o-y, boy." The poorest citizen had a bush of roses

and a bee-hive in his yard, and the people were very forlorn

who could not have a bit of honey-comb at least once a day.

The court preferred it to any other food. Indeed it was this

particular Queen who was in the kitchen eating bread and honey,

in the song.

But to return to the Bee Festival, on this especial sixteenth of May. At sunset when the bees flew back to their hives for the last time with their loads of honey, the court also went home. They danced along in a splendid merry procession. The cream-colored ponies the King and Queen rode pranced lightly in advance, their slender hoofs keeping time to the flutes and the bells; and the gallants, leading the ladies by the tips of their dainty fingers, came after them with gay waltzing steps. The nurses who carried the Princess[Page 46] Rosetta held their heads high, and danced along as bravely as the others, waving their peacock-feather fans in their unoccupied hands. They bore the little Princess in her basket between them as lightly as a feather. Up and down she swung. When they first started she laughed and crowed; then she became very quiet. The nurses thought she was asleep. They had laid a little satin coverlet over her, and put a soft thick veil over her face, that the damp evening-air might not give her the croup. The Princess Rosetta was quite apt to have the croup.

The nurses cast a glance down at the veil and satin coverlet which were so motionless. "Her Royal Highness is asleep," they whispered to each other with nods. The nurses were handsome young women, and they wore white lace caps, and beautiful long darned lace aprons. They swung the Princess's basket along so easily that finally one of them remarked upon it.

"How very light her Royal Highness is," said she.

"She weighs absolutely nothing at all," replied the other nurse who was carrying the Princess, "absolutely nothing at all."

"Well, that is apt to be the case with such high-born infants," said the first nurse. And they all waved their fans again in time to the music.

When they reached the palace, the massive doors were thrown open, and the court passed in. The nurses bore the Princess Rosetta's basket up the grand[Page 47] marble stair, and carried it into the nursery.

"We will lift her Royal Highness out very carefully, and possibly we can put her to bed without waking her," said the Head-nurse.

But her Royal Highness's ladies-of-the-bed-chamber who were in waiting set up such screams of horror at her remark, that it was a wonder that the Princess did not awake directly.

"O-h!" cried a lady-of-the-bed-chamber, "put her Royal Highness to bed, in defiance of all etiquette, before the Prima Donna of the court has sung her lullaby! Preposterous! Lift her out without waking her, indeed! This nurse should be dismissed from the court!"

"O-h!" cried another lady, tossing her lovely head scornfully, and giving her silken train an indignant swish; "the idea of putting her Royal Highness to bed without the silver cup of posset, which I have here for her!"

"And without taking her rose-water bath!" cried another, who was dabbling her lily fingers in a little ivory bath filled with rose-water.

"And without being anointed with this Cream of Lilies!" cried one with a little ivory jar in her hand.

"And without having every single one of her golden ringlets dressed with this pomade scented with violets and almonds!" cried one with a round porcelain box.

"Or even having her curls brushed!" cried a lady[Page 48] as if she were fainting, and she brandished an ivory hair-brush set with turquoises.

"I suppose," remarked a lady who was very tall and majestic in her carriage, "that this nurse would not object to her Royal Highness being put to bed without—her nightgown, even!"

And she held out the Princess's little embroidered nightgown, and gazed at the Head-nurse with an awful air.

"I beg your pardon humbly, my Ladies," responded the Head-nurse meekly. Then she bent over the basket to lift out the Princess.

Every one stood listening for her Royal Highness's pitiful scream when she should awake. The lady with the cup of posset held it in readiness, and the ladies with the Cream of Lilies, the violet and almond pomade and the ivory hair-brush looked anxious to begin their duties. The Prima Donna stood with her song in hand, and the first court fiddler had his bow raised all ready to play the accompaniment for her. Writing a fresh lullaby for the Princess every day, and setting it to music, were among the regular duties of the Poet Laureate and the first musical composer of the court.

The Head-nurse with her eyes full of tears because of the reproaches she had received, reached down her arms and attempted to lift the Princess Rosetta—suddenly she turned very white, and tossed aside the [Page 49] veil and the satin coverlet. Then she gave a loud scream, and fell down in a faint.

The ladies stared at one another.

"What is the matter with the Head-nurse?" they asked. Then the second nurse stepped up to the basket and reached down to clasp the Princess Rosetta. Then she gave a loud scream, and fell down in a faint.

The third nurse, trembling so she could scarcely stand, came next. After she had stooped over the basket, she also gave a loud scream and fainted. Then the fourth nurse stepped up, bent over the basket, and fainted. So all the Princess Rosetta's nurses lay fainting on the floor beside her basket.

It was contrary to the rules of etiquette for any one except the nurses to approach nearer than five yards to her Royal Highness before she was taken from her basket. So they crowded together at that distance and craned their necks.

"What can ail the nurses?" they whispered in terrified tones. They could not go near enough to the basket to see what the trouble was, and still it seemed very necessary that they should.

"I wish I had a telescope," said the lady with the hair-brush.

But there was none in the room, and it was contrary to the rules of etiquette for any person to leave it until the Princess was taken from the basket.

There seemed to be no proper way out of the difficulty.[Page 50] Finally the first fiddler stood up with an air of resolution, and began unwinding the green silk sash from his waist. It was eleven yards long. He doubled it, and launched it at the basket, like a lasso.

"There is nothing in the code of etiquette to prevent the Princess approaching us before she is taken from her basket," he said bravely. All the ladies applauded.

He threw the lasso very successfully. It went quite around the basket. Then he drew it gently over the five yards. They all crowded around, and looked[Page 51] into it.

The Princess was not in the basket!

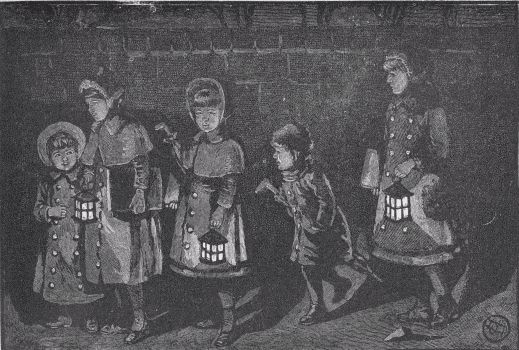

[plate 5]

THE PRINCESS WAS NOT IN THE BASKET.

That night the whole kingdom was in a turmoil. The Bee Guards were called out, and patrolled the city, alarm-bells rung, signal fires burned, and everybody was out with a lantern. They searched every inch of the road to the park where the Bee Festival had been held, for it did seem at first as if the Princess had possibly been spilled out of the basket, although the nurses were confident that it was not so. So they searched carefully, and the nurses were in the meantime placed in custody. But nothing was found. The people held their lanterns low, and looked under every bush, and even poked aside the grasses, but they could not find the Princess on the road to the park.

Then a regular force of detectives was organized, and the search continued day after day. Every house in the country was examined in every nook and corner. The cupboards even were all ransacked, and the bureau drawers. The King had a favorite book of philosophy, and one motto which he had learned in his youth recurred to him. It was this:

"When a-seeking, seek in the unlikely places, as[Page 52] well as the likely; for no man can tell the road that lost things may prefer."

So he ordered search to be made in unlikely as well as likely places, for the Princess; and it was carried so far that the people had all to turn their pockets inside out, and shake their shawls and table-cloths. But it was all of no use. Six months went by, and the Princess Rosetta had not been found. The King and Queen were broken-hearted. The Queen wept all day long, and her tears fell into her honey, until it was no longer sweet, and she could not eat it. The King sat by himself and had no heart for anything.

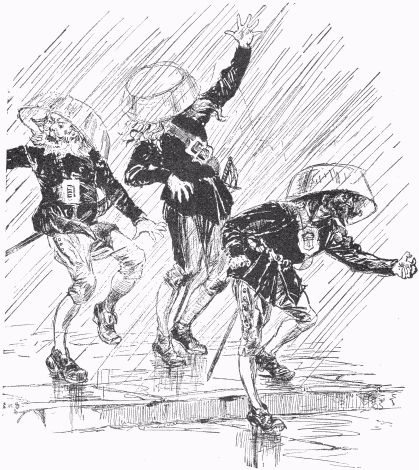

But the four nurses were in nearly as much distress. Not only had they been very fond of the little Princess, and were grieving bitterly for her loss, but they had also a punishment to endure. They had been released from custody, because there was really no evidence against them, but in view of their possible carelessness, and in perpetual reminder of the loss of the Princess, a sentence had been passed upon them. They had been condemned to wear their bonnets the wrong way around, indoors and out, until the Princess should be found. So the poor nurses wept into the crowns of their bonnets. They had little peep-holes in the straw that they might see to get about, and they lifted up the capes in order to eat; but it was very trying. The nurses were all pretty young women too, and the Head-nurse who came of quite a distinguished [Page 55] family was to have been married soon. But how could she be a bride and wear a veil with her face in the crown of her bonnet?

The Head-nurse was quite clever, and she thought about the Princess's disappearance, until finally her thoughts took shape. One day she put on her shawl—her bonnet was always on—and set out to call on the Baron Greenleaf. The Baron was an old man who was said to be versed in white magic, and lived in a stone tower with his servants and his house-keeper.

When the Head-nurse came into the tower-yard, the dog began to bark; he was not used to seeing a woman with her face in the crown of her bonnet. He thought that her head must be on the wrong way, and that she was a monster, and had designs upon his master's property. So he barked and growled, and caught hold of her dress, and the Head-nurse screamed. The Baron himself came running downstairs, and opened the door. "Who is there?" cried he.

But when he saw the woman with her bonnet on wrong he knew at once that she must be one of the Princess's nurses. So he ordered off the dog, and ushered the nurse into the tower. He led her into his study, and asked her to sit down. "Now, madam, what can I do for you?" he inquired quite politely.

"Oh, my lord!" cried the Head-nurse in her muffled voice, "help me to find the Princess."

The Baron, who was a tall lean old man and wore[Page 56] a very large-figured dressing-gown trimmed with fur, frowned, and struck his fist down upon the table. "Help you to find the Princess!" he exclaimed; "don't you suppose I should find her on my own account if I could? I should have found her long before this if the idiots had not broken all my bottles, and crystals, and retorts, and mirrors, and spilled all the magic fluids, so that I cannot practice any white magic at all. The idea of looking for a princess in a bottle—that comes of pinning one's faith upon philosophy!"

"Then you cannot find the Princess by white magic?" the Head-nurse asked timidly.

The Baron pounded the table again. "Of course I cannot," he replied, "with all my magical utensils smashed in the search for her."

The Head-nurse sighed pitifully.

"I suppose that you do not like to go about with your face in the crown of your bonnet?" the Baron remarked in a harsh voice.

The Head-nurse replied sadly that she did not.

"It doesn't seem to me that I should mind it much," said the Baron.

The Head-nurse looked at his grim old face through the peep-holes in her bonnet-crown, and thought to herself that if she were no prettier than he, she should not mind much either, but she said nothing.

Suddenly there was a knock at the tower-door.

"Excuse me a moment," said the Baron; "my housekeeper is deaf, and my other servants have gone out." And he ran down the tower-stair, his dressing-gown sweeping after him.

Presently he returned, and there was a young man with him. This young man was as pretty as a girl, and he looked very young. His blue eyes were very sharp and bright, and he had rosy cheeks and fair curly hair. He was dressed very poorly, and around his shoulders were festooned strings of something that looked like fine white flowers, but it was in reality pop-corn. He carried a great basket of pop-corn, and bore a corn-popper over his shoulder.

When he entered he bowed low to the Head-nurse; her bonnet did not seem to surprise him at all. "Would you like to buy some of my nice pop-corn, madam?" he asked.

She curtesied. "Not to-day," she replied.

But in reality she did not know what pop-corn was. She had never seen any, and neither had the Baron. That indeed was the reason why he had admitted the man—he was curious to see what he was carrying. "Is it good to eat?" he inquired.

"Try it, my lord," answered the man. So the Baron put a pop-corn in his mouth and chewed it critically. "It is very good indeed," he declared.

The man passed the basket to the Head-nurse, and she lifted the cape of her bonnet and put a pop-corn in[Page 58] her mouth, and nibbled it delicately. She also thought it very good.

"But there is no use in discussing new articles of food when the kingdom is under the cloud that it is at present, and my retorts and crystals all smashed," said the Baron.

"Why, what is the cloud, my lord?" inquired the Pop-corn man. Then the Baron told him the whole story.

"Of course it is necromancy," remarked the Pop-corn man thoughtfully, when the Baron had finished.

The Baron pounded on the table until it danced. "Necromancy!" he cried, "of course it's necromancy! Who but a necromancer could have made a child invisible, and stolen her away in the face and eyes of the whole court?"

"Have you any idea where she is?" ask the Pop-corn man.

The Baron stared at him in amazement.

"Idea where she is?" he repeated scornfully. "You are just of a piece with the idiots who broke my mirrors to see if the Princess was not behind them! How should we have any idea where she is if she is lost, pray?"

The Pop-corn man blushed, and looked frightened, but the Head-nurse spoke up quite bravely, although her voice was so muffled, and said that she really did have some idea of the Princess's whereabouts. She[Page 59] propounded her views which were quite plausible. It was her opinion that only an enemy of the King would have caused the Princess to be stolen, and as the King had only one enemy of whom anybody knew, and he was the King across the river, she thought the Princess must be there.

"It seems very likely," said the Baron after she had finished, "but if she is there it is hopeless. Our King could never conquer the other one, who has a much stronger army."

"Do you know," asked the Pop-corn man, "if they have ever had any pop-corn on the other side of the river?"

"I don't think they have," replied the Baron.

"Then," said the Pop-corn man, "I think I can free the Princess."

"You!" cried the Baron scornfully.

[Page 61]

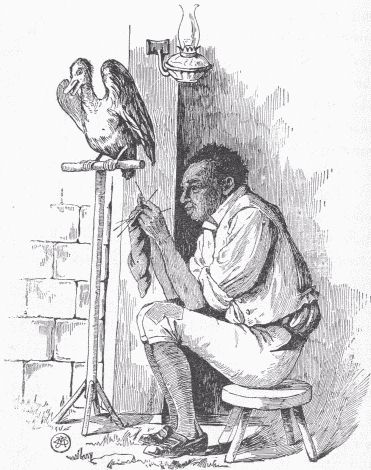

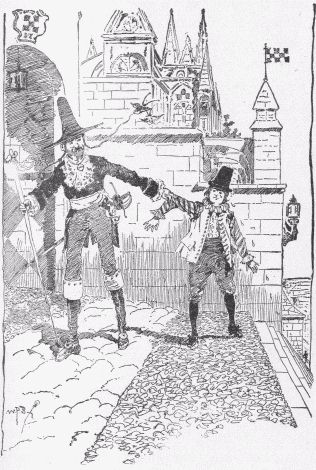

[plate 7]

'YOU!' CRIED THE BARON SCORNFULLY.

But the Pop-corn man said nothing more. He bowed low to the Baron and the Head-nurse, and left the tower.

"The idea of his talking as he did," said the Baron. But the nurse was pinning her shawl, and she hurried out of the tower and overtook the Pop-corn man.

"How are you going to manage it?" whispered she, touching his sleeve.

The Pop-corn man started. "Oh, it's you?" he said. "Well, you wait a little, and you will see. Do you suppose you could find six little boys who would[Page 60] be willing to go over the river with me to-morrow?"

"Would it be quite safe?"

"Quite safe."

"I have six little brothers who would go," said the Head-nurse.

So it was arranged that the six little brothers should go across the river with the Pop-corn man; and the next morning they set out. They were all decorated with strings of Pop-corn, they carried baskets of pop-corn, and bore corn-poppers over their shoulders, and they crossed the river in a row boat.

Once over the river they went about peddling pop-corn. The man sent the boys all over the city, but he himself went straight to the palace.

He knocked at the palace-door, and the maid-servant came. "Is the King at home?" asked the Pop-corn man.

The maid said he was, and the Pop-corn man asked to see him. Just then a baby cried.

"What baby is that crying?" asked he.

"A baby that was brought here at sunset, several months ago," replied the maid; and he knew at once that he had found the Princess.

"Will you find out if I can see the King?" he said.

"I'll see," answered the maid. And she went in to find the King. Pretty soon she returned and asked the Pop-corn man to step into the parlor, which he[Page 63] did, and soon the King came downstairs.

The Pop-corn man displayed his wares, and the King tasted. He had never seen any pop-corn before, and he was both an epicure and a man of hobbies. "It is the nicest food that ever I tasted," he declared, and he bought all the man's stock.

"I can buy corn for you for seed, and I can order poppers enough to supply the city," suggested the Pop-corn man.

"So do," cried the King. And he gave orders for seven ships' cargoes of seed corn and fifty of poppers. "My people shall eat nothing else," said the King, "and the whole kingdom shall be planted with it. I am satisfied that it is the best national food."

That day the court dined on pop-corn, and as it was very light and unsatisfying, they had to eat a long time. They were all the after-noon dining. Right after dinner the King wrote out his royal decree that all the inhabitants should that year plant pop-corn instead of any other grain or any vegetable, and that as soon as the ships arrived they should make it their only article of food. For the King, when he had learned from the Pop-corn man that the corn needed to be not only ripe but well dried before it would pop, could not wait, but had ordered five hundred cargoes of pop-corn for immediate use.

So as soon as the ships arrived the people began at once to pop corn and eat it. There was a sound[Page 64] of popping corn all over the city, and the people popped all day long. It was necessary that they should, because it took such a quantity to satisfy hunger, and when they were not popping they had to eat. People shook the poppers until their arms were tired, then gave them to others, and sat down to eat. Men, women and children popped. It was all that they could do, with the exception of planting the seed-corn, and then they were faint with hunger as they worked. The stores and schools were closed. In the palace the King and Queen themselves were obliged to pop in order to secure enough to eat, and the nobles and the court-ladies toiled and ate, day and night. But the little stolen Princess and the King's son, the little Prince, could not pop corn, for they were only babies.

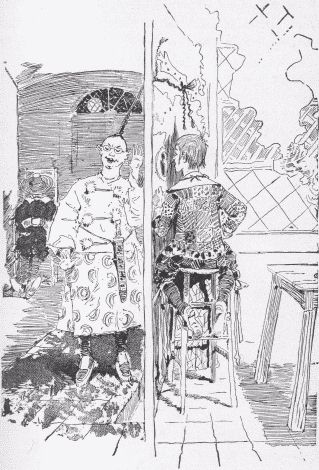

[plate 8]

BOTH THE KING AND QUEEN WERE OBLIGED TO POP.

When the people across the river had been popping corn for about a month, the Pop-corn man went to the King of Romalia's palace, and sought an audience. He told him how he had discovered his daughter in the palace of the King across the river.

The King of Romalia clasped his hands in despair. "I must make war," said he, "but my army is nothing to his."

However, he at once went about making war. He ordered the swords to be cleaned with sand-paper until they shone, and new bullets to be cast. The Bee Guards were drilled every day, and the people[Page 65] could not sleep for the drums and the fifes.

When everything was ready the King of Romalia and his army crossed the river and laid siege to the city. They had expected to have the passage of the river opposed, but not a foeman was stationed on the opposite bank. All the spears they could see were the waving green ones of pop-corn fields. They marched straight up to the city walls and laid siege. The inhabitants fought on the walls and in the gate-towers, but not very many could fight at a time, because they would have to stop and pop corn and eat.

The defenders grew fewer and fewer, some were[Page 66] killed, and all of them were growing too tired and weak to fight. They could not eat enough pop-corn to give them strength and have any time left to fight. They filled their pockets and tried to eat pop-corn as they fought, but they could not manage that very well.

On the third day the city surrendered with very little loss of life on either side, and the little Princess Rosetta was restored to her parents. There was great rejoicing all through Romalia; in the evening there was an illumination and a torch-light procession. The nurses marched with their bonnets on the right way, and the Knights of the Golden Bee were out in full regalia.

The next day the Head-nurse was married, and the King gave her a farm and a dozen bee-hives for a wedding present, and the Queen a beautiful bridal bonnet trimmed with white plumes and hollyhocks.

All the court, the Baron and the Pop-corn man went to the wedding, and wedding-cake and corn-balls were passed around.

After the wedding the Pop-corn man went home. He lived in another country on the other side of a mountain. The King pressed him to take some reward. "I am puzzled," he said to the Pop-corn man, "to know what to offer you. The usual reward in such cases is the hand of the Princess in marriage, but Rosetta is not a year old. If there is anything else[Page 67] you can think of"—

The Pop-corn man kissed the King's hand and replied that there was nothing that he could think of except a little honey-comb. He should like to carry some to his mother. So the King gave him a great piece of honey-comb in a silver dish, and the Pop-corn man departed.

He never came to Romalia again, but the Poet Laureate celebrated him in an epic poem, describing the loss of the Princess and the war for her rescue. The Princess was never stolen again—indeed the necromancer across the river who had kidnaped her was imprisoned for life on a diet of pop-corn which he popped himself.

The King across the river became tired of pop-corn, as it had caused his defeat, and forbade his people to eat it. He paid tribute to the King of Romalia as long as he lived; but after his death, when his son, the young prince, came to reign, affairs were on a very pleasant footing between the two kingdoms. The new King was very different from his father, being generous and amiable, and beloved by every one. Indeed Rosetta, when she had grown to be a beautiful maiden, married him and went to live as a Queen where she had been a captive.

And when Rosetta went across the river to live, the King, her father, gave her some bee-hives for a wedding present, and the bees thrived equally in both[Page 68] countries. All the difference in the honey was this: in Romalia the bees fed more on clover, and the honey tasted of clover: and in the country across the river on peppermint, and that honey tasted of peppermint. They always had both kinds at their Bee Festivals.

All children have wondered unceasingly from their very first Christmas up to their very last Christmas, where the Christmas presents come from. It is very easy to say that Santa Claus brought them. All well regulated people know that, of course; but the reindeer, and the sledge, and the pack crammed with toys, the chimney, and all the rest of it—that is all true, of course, and everybody knows about it; but that is not the question which puzzles. What children want to know is, where do these Christmas presents come from in the first place? Where does Santa Claus get them? Well the answer to that is, In the garden of the Christmas Monks. This has not been known until very lately; that is, it has not been known till very lately except in the immediate vicinity of the Christmas Monks. There, of course, it has been known for ages. It is rather an out-of-the-way place; and that accounts for our never hearing of it before.

The Convent of the Christmas Monks is a most charmingly picturesque pile of old buildings; there are towers and turrets, and peaked roofs and arches, and everything which could possibly be thought of in the architectural line, to make a convent picturesque.[Page 70] It is built of graystone; but it is only once in a while that you can see the graystone, for the walls are almost completely covered with mistletoe and ivy and evergreen. There are the most delicious little arched windows with diamond panes peeping out from the mistletoe and evergreen, and always at all times of the year, a little Christmas wreath of ivy and hollyberries is suspended in the center of every window. Over all the doors, which are likewise arched, are Christmas garlands, and over the main entrance Merry Christmas in evergreen letters.

The Christmas Monks are a jolly brethren; the robes of their order are white, gilded with green garlands, and they never are seen out at any time of the year without Christmas wreaths on their heads. Every morning they file in a long procession into the chapel, to sing a Christmas carol; and every evening they ring a Christmas chime on the convent bells.

[plate 9]

GOING INTO THE CHAPEL.

They eat roast turkey and plum pudding and mince-pie for dinner all the year round; and always carry what is left in baskets trimmed with evergreen, to the poor people. There are always wax candles lighted and set in every window of the convent at nightfall; and when the people in the country about get uncommonly blue and down-hearted, they always go for a cure to look at the Convent of the Christmas Monks after the candles are lighted and the chimes are ringing. It brings to mind things which never fail to[Page 73] cheer them.

But the principal thing about the Convent of the Christmas Monks is the garden; for that is where the Christmas presents grow. This garden extends over a large number of acres, and is divided into different departments, just as we divide our flower and vegetable gardens; one bed for onions, one for cabbages, and one for phlox, and one for verbenas, etc.

Every spring the Christmas Monks go out to sow the Christmas-present seeds after they have ploughed the ground and made it all ready.

There is one enormous bed devoted to rocking-horses. The rocking-horse seed is curious enough; just little bits of rocking-horses so small that they can only be seen through a very, very powerful microscope. The Monks drop these at quite a distance from each other, so that they will not interfere while growing; then they cover them up neatly with earth, and put up a sign-post with "Rocking-horses" on it in evergreen letters. Just so with the penny-trumpet seed, and the toy-furniture seed, the skate-seed, the sled-seed, and all the others.

Perhaps the prettiest and most interesting part of the garden, is that devoted to wax dolls. There are other beds for the commoner dolls—for the rag dolls, and the china dolls, and the rubber dolls, but of course wax dolls would look much handsomer growing. Wax dolls have to be planted quite early in the season; for[Page 74] they need a good start before the sun is very high. The seeds are the loveliest bits of microscopic dolls imaginable. The Monks sow them pretty close together, and they begin to come up by the middle of May. There is first just a little glimmer of gold, or flaxen, or black, or brown as the case may be, above the soil. Then the snowy foreheads appear, and the blue eyes, and black eyes, and, later on, all those enchanting little heads are out of the ground, and are nodding and winking and smiling to each other the whole extent of the field; with their pinky cheeks and sparkling eyes and curly hair there is nothing so pretty as these little wax doll heads peeping out of the earth. Gradually, more and more of them come to light, and finally by Christmas they are all ready to gather. There they stand, swaying to and fro, and dancing lightly on their slender feet which are connected with the ground, each by a tiny green stem; their dresses of pink, or blue, or white—for their dresses grow with them—flutter in the air. Just about the prettiest sight in the world, is the bed of wax dolls in the garden of the Christmas Monks at Christmas time.

Of course ever since this convent and garden were established (and that was so long ago that the wisest man can find no books about it) their glories have attracted a vast deal of admiration and curiosity from the young people in the surrounding country; but as the garden is enclosed on all sides by an immensely[Page 75] thick and high hedge, which no boy could climb, or peep over, they could only judge of the garden by the fruits which were parcelled out to them on Christmas-day.

You can judge, then, of the sensation among the young folks, and older ones, for that matter, when one evening there appeared hung upon a conspicuous place in the garden-hedge, a broad strip of white cloth trimmed with evergreen and printed with the following notice in evergreen letters:

"WANTED:—By the Christmas Monks, two good boys to assist in garden work. Applicants will be examined by Fathers Anselmus and Ambrose, in the convent refectory, on April 10th."

This notice was hung out about five o'clock in the evening, some time in the early part of February. By noon, the street was so full of boys staring at it with their mouths wide open, so as to see better, that the king was obliged to send his bodyguard before him to clear the way with brooms, when he wanted to pass on his way from his chamber of state to his palace.

There was not a boy in the country but looked upon this position as the height of human felicity. To work all the year in that wonderful garden, and see those wonderful things growing! and without doubt any boy who worked there could have all the toys he wanted, just as a boy who works in a candy-shop always has[Page 76] all the candy he wants!

But the great difficulty, of course, was about the degree of goodness requisite to pass the examination. The boys in this country were no worse than the boys in other countries, but there were not many of them that would not have done a little differently if he had only known beforehand of the advertisement of the Christmas Monks. However, they made the most of the time remaining, and were so good all over the kingdom that a very millennium seemed dawning. The school teachers used their ferrules for fire wood, and the King ordered all the birch-trees cut down and exported, as he thought there would be no more call For them in his own realm.

When the time for the examination drew near, there were two boys whom every one thought would obtain the situation, although some of the other boys had lingering hopes for themselves; if only the Monks would examine them on the last six weeks, they thought they might pass. Still all the older people had decided in their minds that the Monks would choose these two boys. One was the Prince, the King's oldest son; and the other was a poor boy named Peter. The Prince was no better than the other boys; indeed, to tell the truth, he was not so good; in fact, was the biggest rogue in the whole country; but all the lords and the ladies, and all the people who admired the lords and ladies, said it was[Page 79] their solemn belief that the Prince was the best boy in the whole kingdom; and they were prepared to give in their testimony, one and all, to that effect to the Christmas Monks.

Peter was really and truly such a good boy that there was no excuse for saying he was not. His father and mother were poor people; and Peter worked every minute out of school hours, to help them along. Then he had a sweet little crippled sister whom he was never tired of caring for. Then, too, he contrived to find time to do lots of little kindnesses for other people. He always studied his lessons faithfully, and never ran away from school. Peter was such a good boy, and so modest and unsuspicious that he was good, that everybody loved him. He had not the least idea that he could get the place with the Christmas Monks, but the Prince was sure of it.

When the examination day came all the boys from far and near, with their hair neatly brushed and parted, and dressed in their best clothes, flocked into the convent. Many of their relatives and friends went with them to witness the examination.

The refectory of the convent where they assembled, was a very large hall with a delicious smell of roast turkey and plum pudding in it. All the little boys sniffed, and their mouths watered.

The two fathers who were to examine the boys were perched up in a high pulpit so profusely trimmed with[Page 80] evergreen that it looked like a bird's nest; they were remarkably pleasant-looking men, and their eyes twinkled merrily under their Christmas wreaths. Father Anselmus was a little the taller of the two, and Father Ambrose was a little the broader; and that was about all the difference between them in looks.

The little boys all stood up in a row, their friends stationed themselves in good places, and the examination began.

Then if one had been placed beside the entrance to the convent, he would have seen one after another, a crestfallen little boy with his arm lifted up and crooked, and his face hidden in it, come out and walk forlornly away. He had failed to pass.

The two fathers found out that this boy had robbed birds' nests, and this one stolen apples. And one after another they walked disconsolately away till there were only two boys left: the Prince and Peter.

"Now, your Highness," said Father Anselmus, who always took the lead in the questions, "are you a good boy?"

"O holy Father!" exclaimed all the people—there were a good many fine folks from the court present. "He is such a good boy! such a wonderful boy! we never knew him to do a wrong thing."

"I don't suppose he ever robbed a bird's nest?" said Father Ambrose a little doubtfully.

"No, no!" chorused the people.

"Nor tormented a kitten?"

"No, no, no!" cried they all.

At last everybody being so confident that there could be no reasonable fault found with the Prince, he was pronounced competent to enter upon the Monks' service. Peter they knew a great deal about before—indeed a glance at his face was enough to satisfy any one of his goodness; for he did look more like one of the boy angels in the altar-piece than anything else. So after a few questions, they accepted him also; and the people went home and left the two boys with the Christmas Monks.

The next morning Peter was obliged to lay aside his homespun coat, and the Prince his velvet tunic, and both were dressed in some little white robes with evergreen girdles like the Monks. Then the Prince was set to sewing Noah's Ark seed, and Peter picture-book seed. Up and down they went scattering the seed. Peter sang a little psalm to himself, but the Prince grumbled because they had not given him gold-watch or gem seed to plant instead of the toy which he had outgrown long ago. By noon Peter had planted all his picture-books, and fastened up the card to mark them on the pole; but the Prince had dawdled so his work was not half done.

"We are going to have a trial with this boy," said the Monks to each other; "we shall have to set him a penance at once, or we cannot manage him[Page 84] at all."