Title: Literary Hearthstones of Dixie

Author: La Salle Corbell Pickett

Release date: August 30, 2005 [eBook #16622]

Most recently updated: December 12, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mark C. Orton and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

PHILADELPHIA & LONDON

J.B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

1912

COPYRIGHT, 1911, BY J.B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1912, BY J.B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER, 1912

PRINTED BY J.B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

AT THE WASHINGTON SQUARE PRESS

PHILADELPHIA, U.S.A.

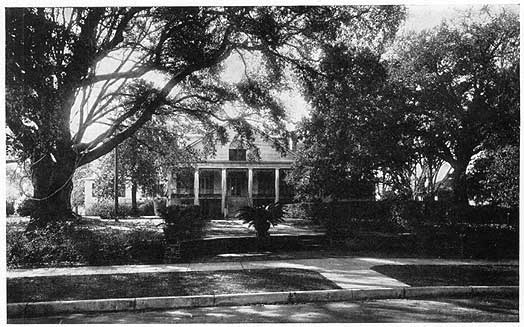

THE HOME OF AUGUSTA EVANS WILSON, ASHLAND PLACE

Now owned by Mrs. George Fearn, Jr.

| Transcriber's Note: There is an inconsistency in the fifth paragraph of the Forword where the author refers to Dr. Bagley's "The Old Fashioned Gentleman," and the reference to Dr. Bagby's "The Old Virginia Gentleman" in the chapter "Bacon and Greens". |

The fires still glow upon the hearthstones to which our southern writers in the olden days gave us friendly welcome. They are as bright to-day as when, "four feet on the fender," we talked with some gifted friend whose pen, dipped in the heart's blood of life, gave word to thoughts which had flamed within us and sought vainly to escape the walls of our being that they might go out to the world and fulfil their mission. They who built the shrines before which we offer our devotion have passed from the world of men, but the fires they kindled yet burn with fadeless light.

To us who have dwelt in the same environment and found beauty in the same scenes that inspired them to eloquent expression of the thoughts, the loves, the hopes, and the aspirations which were our own as well as theirs, these writers of our South are living still and will live through the long procession of the years. In the garden of our lives they planted the flowers of poesy, of fable, and of romance. With the changes of the years those flowers may have passed into the realm of the old-fashioned, like the blossoms in Grandmother's garden, but are there any sweeter or more royally blooming than these?

The lustre of our gifted ones is not dimmed by the passage of time, but in the rush of new books upon the world the readers of to-day lose sight of the volumes which wove threads of gold into the joys and sorrows of the generation now travelling the downward slope of life. Their starry radiance is sometimes lost to view in the electric flash of the present day. If these pages can in any slight way aid in keeping their memory bright they will have reached their highest aim.

The poets of Dixie in war days tended the flames that glowed upon the altar of patriotism. Their lives were given to their country as truly as if their blood had crimsoned the sod of hard-fought fields. They gave of their best to our cause. Their bugle notes echo through the years, and the mournful tones of the dirges they sang over the grave of our dreams yet thrill our hearts. Before our eyes "The Conquered Banner" sorrowfully droops on its staff and "The Sword of Lee" flashes in the lines of our Poet-Priest.

For the quotations with which are illustrated the varying phases of his poetic thought I am indebted to the kindness of the publishers of Father Ryan's poems, Messrs. P.J. Kenedy & Sons. For certain selections from the poems of Hayne I am indebted to the Lothrop, Lee & Shephard Company, and for selections from Dr. Bagley's "The Old Fashioned Gentleman," Messrs. Charles Schribner's Sons.

My thanks are due the Houghton, Mifflin Company for permission to include in my paper on Margaret Junkin Preston two poems and other quotations from the "Life and Letters of Margaret J. Preston," by Mrs. Allan, the step-daughter of Mrs. Preston.

The selections in the article on Georgia's doubly gifted son, Sidney Lanier, poet and musician, are given through the kind permission of Professor Edwin Mims and of Doubleday, Page & Company, publishers of Mrs. Clay's "A Belle of the Fifties."

EDGAR ALLAN POE

"I am a Virginian; at least, I call myself one, for I have resided all my life until within the last few years in Richmond."

Thus Edgar A. Poe wrote to a friend. The fact of his birth in Boston he regarded as merely an unfortunate accident, or perhaps the work of that malevolent "Imp of the Perverse" which apparently dominated his life. That it constituted any tie between him and the "Hub of the Universe," unless it might be the inverted tie of opposition, he never admitted. The love which his charming little actress mother cherished for the city in which she had enjoyed her greatest triumphs seemed to have turned to hatred in the heart of her brilliant and erratic son. In his short and disastrous sojourn in Boston, when his fortunes were at their lowest ebb, it is not likely that his thought once turned to the old house on Haskins, now Carver, Street, where his ill-starred life began.

The reason given by Poe, "I have resided there all my life until within the last few years," suggests but slight cause for his love of Richmond, the home of his childhood, the darkening clouds of which, viewed through the softening lens of years, may have shaded off to brighter tints, as the roughness of a landscape disappears and melts into mystic, dreamy beauty as we journey far from the scene.

The three women who had been the stars in the troubled sky of his youth irradiated his memory of the Queen City of the South. In the churchyard of historic old Saint John's, that once echoed to the words of Patrick Henry, "Give me liberty or give me death!" Poe's mother lay in an unidentified grave. In Hollywood slept his second mother, who had surrounded his boyhood with the maternal affection that, like an unopened rose in her heart, had awaited the coming of the little child who was to be the sunbeam to develop it into perfect flowering. On Shockoe Hill was the tomb of "Helen," his chum's mother, whose beauty of face and heart brought the boyish soul

To the Glory that was Greece

And the grandeur that was Rome.

Through the three-fold sanctification of the twin priestesses, Love and Sorrow, Richmond was his home.

So Virginia claims her poet son, the tragedy of whose life is a gloomy, though brilliant, page in the history of American literature.

There are varying stories told of Poe's Richmond home. The impression that he was the inmate of a stately mansion, where he was trained to extravagance which wrought disaster in later years, is not borne out by the evidence. When the loving heart and persistent will of Mrs. Allan opened her husband's reluctant door to the orphaned son of the unfortunate players, that door led into the second story of the building at the corner of Fourteenth Street and Tobacco Alley, in which Messrs. Ellis & Allan earned a comfortable, but not luxurious, living by the sale of the commodity which gave the alley its name. As it was customary in those days for merchants to live in the same building with their business, the fact that he did so does not argue that Mr. Allan was "down on his luck," but neither does it presuppose that he was the possessor of wealth. But it was a home in the truest sense for little Edgar, for it was radiant with the love of the tender-hearted woman who had brought him within its friendly walls.

From this home Mr. Allan went to London to establish a branch of the Company business. He was accompanied by Mrs. Allan and Edgar, and the boy was placed in the school of Stoke-Newington, shadowy with the dim procession of the ages and gloomed over by the memory of Eugene Aram. The pictured face of the head of the Manor School, Dr. Bransby, indicates that the hapless boys under his care had stronger than historic reasons for depression in that ancient institution.

England was thrilling with the triumph of Waterloo, and even Stoke-Newington must have awakened to the pulsing of the atmosphere. Not far away were Byron, Shelley, and Keats, at the beginning of their brief and brilliant careers, the glory and the tragedy of which may have thrown a prophetic shadow over the American boy who was to travel a yet darker path than any of these.

Under the elms that bordered the old Roman road, what forms of antique romance would lie in wait for the dreamy lad, joining him in his Saturday afternoon walks and telling him stories of their youth in the ancient days to mingle with the age-youth in the heart of the dual-souled boy. The green lanes were haunted by memories of broken-hearted lovers: Earl Percy, mourning for the fair and fickle Anne; Essex, calling vainly for the royal ring that was to have saved him; Leicester, the Lucky, a more contented ghost, returning in pleasing reminiscence to the scenes of his earthly triumphs, comfortably oblivious of his earthly crimes. What boy would not have found inspiration in gazing at the massive walls, locked and barred against him though they were, within which the immortal Robinson Crusoe sprang into being and found that island of enchantment, the favorite resort of the juvenile imagination in all the generations since?

At Stoke-Newington the introspective boy found little to win him from that self-analysis which later enabled him to mystify a world that rarely pauses to take heed of the ancient exhortation, "Know thyself." In the depths of his own being he found the story of "William Wilson," with its atmosphere of weird romance and its heart of solemn truth.

Incidentally, he uplifted the reputation of the American boy, so far as regarded Stoke-Newington's opinion, by assuring his mates when they marvelled over his athletic triumphs and feats of skill that all the boys in America could do those things.

At the end of the year in which the family returned from Stoke-Newington Mr. Allan moved into a plain little cottage a story and a half high, with five rooms on the ground floor, at the corner of Clay and Fifth Streets. Here they lived until, in 1825, Mr. Allan inherited a considerable amount of money and bought a handsome brick residence at the corner of Main and Fifth Streets, since known as the Allan House. With the exception of two very short intervals, from June of this year until the following February was all the time that Poe spent in the Allan mansion.

The Allan House, in its palmy days, might appeal irresistibly to the mind of a poet, attuned to the harmonies of artistic design and responsive to the beauties of romantic environment. It was a two-story building with spacious rooms and appointments that suggested the taste of the cultivated mistress of the stately dwelling. On the second floor was "Eddie's room," as she lovingly called it, wherein her affectionate imagination as well as her skill expended themselves lavishly for the pleasure of the son of her heart.

A few years later, upon his sudden return after a long absence, it was his impetuous inquiry of the second Mrs. Allan as to the dismantling of this room that led to his hasty retreat from the house, an incident upon which his early biographers, led by Dr. Griswold, based the fiction that Mr. Allan cherished Poe affectionately in his home until his conduct toward "the young and beautiful wife" forced the expulsion of the poet from the Allan house. The fact is that Poe saw the second Mrs. Allan only once, for a moment marked by fiery indignation on his part, and on hers by a cold resentment from which the unfortunate visitor fled as from a north wind; the second Mrs. Allan's strong point being a grim and middle-aged determination, rather than "youth and beauty." Not that the thirty calendar years of that lady would necessarily have conducted her across the indefinite boundaries of the uncertain region known as "middle age," but the second Mrs. Allan was born middle-aged, and the almanac had nothing to do with it.

It was in the sunshine of youth and the warmth of love and the fragrance of newly opening flowers of poetry that Edgar Poe lived in the new Allan home and from the balcony of the second story looked out upon the varied scenes of the river studded with green islets, the village beyond the water, and far away the verdant slopes and forested hills into the depths of which he looked with rapt eyes, seeing visions which that forest never held for any other gaze. Mayhap, adown those dim green aisles he previsioned the "ghoul-haunted woodland of Weir" with the tomb of Ulalume at the end of the ghostly path through the forest—the road through life that led to the grave where his heart lay buried. Through the telescope on that balcony he may first have followed the wanderings of Al Araaf, the star that shone for him alone. In the dim paths of the moonlit garden flitted before his eyes the dreamful forms that were afterward prisoned in the golden net of his wondrous poesy.

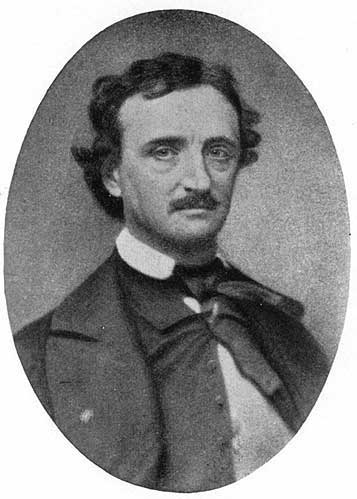

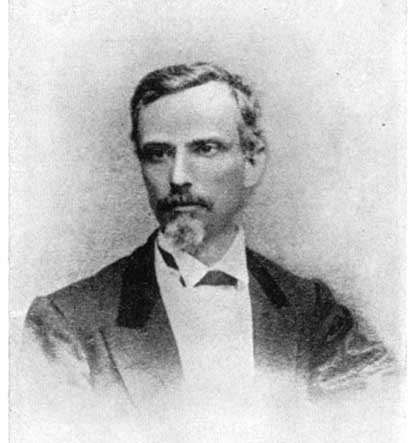

EDGAR ALLAN POE

From the daguerreotype formerly owned by Edmund Clarence Stedman

To these poetic scenes he soon bade farewell, and on St. Valentine's day, 1826, entered the University of Virginia, where Number 13, West Range, is still pointed out as the old-time abiding place of Virginia's greatest poet, whose genius has given rise to more acrimonious discussion than has ever gathered about the name of any other American man of letters. The real home of Poe at this time was the range of hills known as the Ragged Mountains, for it was among their peaks and glens and caverns and wooded paths and rippling streams that he roamed in search of strange tales and mystic poems that would dazzle his readers in after days. His rambles among the hills of the University town soon came to a close. Mr. Allan, being confronted by a gaming debt which he regarded as too large to fit the sporting necessities of a boy of seventeen, took him from college and put him into the counting-room of Ellis & Allan, a position far from agreeable to one accustomed to counting only poetic feet.

The inevitable rupture soon came, and Poe went to Boston, the city of his physical birth and destined to become the place of his birth into the tempestuous world of authorship. Forty copies of "Tamerlane and Other Poems" appeared upon the shelf of the printer—and nowhere else. It is said that seventy-three years later a single copy was sold for $2,250. Had this harvest been reaped by the author in those early days, who can estimate the gain to the field of literature?

Boston proving inhospitable to the firstling of her gifted son's imagination, the Common soon missed the solitary, melancholy figure that had for months haunted the old historic walks. Edgar A. Poe dropped out of the world, or perhaps out of the delusion of fancying himself in the world, and Edgar A. "Perry" appeared, an enlisted soldier in the First Artillery at Fort Independence. For two years "Perry" served his country in the sunlight, and Poe, under night's starry cover, roamed through skyey aisles in the service of the Muse and explored "Al Araaf," the abode of those volcanic souls that rush in fatal haste to an earthly heaven, for which they recklessly exchange the heaven of the spirit that might have achieved immortality.

A severe illness resulted in the disclosure of the identity of the young soldier, and a message was sent to Mr. Allan, who effected his discharge and helped secure for him an appointment to West Point. On his way to the Academy he stopped in Baltimore and arranged for the publication of a new volume, to contain "Al Araaf," a revised version of "Tamerlane," and some short poems.

Some months later No. 28 South Barracks, West Point, was the despair of the worthy inspector who spent his days and nights in unsuccessful efforts to keep order among the embryo protectors of his country. Poe, the leader of the quartette that made life interesting in Number 28, was destined never to evolve into patriotic completion. He soon reached the limit of the endurance of the officials, that being, in the absence of a pliant guardian, the only method by which a cadet could be freed from the walls of the Academy.

Soon after leaving the military school Poe made a brief visit to Richmond, the final break with Mr. Allan took place, and the poet went to Baltimore.

Number 9 Front Street, Baltimore, is claimed as the birthplace of Poe. There is a house in Norfolk that is likewise so distinguished. There are other places, misty with passing generations, similarly known to history. Poe, though not Homeric in his literary methods, had much the same post-mortem experience as the Father of the Epicists.

At the time of the Poet-wanderer's return to Baltimore his aunt, Mrs. Clemm, had her humble but neat and comfortable home on Eastern Avenue, then Wilks Street, and here he found the first home he had known since his childhood and, incidentally, his charming child cousin, Virginia, who was to make his home bright with her devotion through the remainder of her brief life.

In these early days no thought of any but a cousinly affection had rippled the smooth surface of Virginia's childish mind, and she was the willing messenger between Poe and his "Mary," who lived but a short distance from the home of the Clemms, and who, when the frosts of years had descended upon her, denied having been engaged to him—apparently because her elders were more discreet than she was—but admitted that she cried when she heard of his death.

In his attic room on Wilks Street he toiled over the poems and tales that some time would bring him fame.

Poe was living in Amity Street when he won the hundred-dollar prize offered by the Saturday Visitor, with his "Manuscript Found in a Bottle," and wrote his poem of "The Coliseum," which failed of a prize merely because the plan did not admit of making two awards to the same person. A better reward for his work was an engagement as assistant editor of the Southern Literary Messenger, which led to his removal to Richmond.

The Messenger was in a building at Fifteenth and Main Streets, in the second story of which Mr. White, the editor, and Poe, had their offices. The young assistant soon became sole editor of the publication, and it was in this capacity that he entered upon the critical work which was destined to bring him effective enemies to assail his reputation, both literary and personal, when the grave had intervened to prevent any response to their slanders. Not but that he praised oftener than he censured, but the thorn of censure pricks deeply, and the rose of praise but gently diffuses its fragrance to be wafted away on the passing breeze. The sharp satire attracted attention to the Messenger, as attested by the rapid growth of the subscription list.

Here Poe was surrounded by memories of his childhood. The building was next door to that in which Ellis & Allan had their tobacco store in Poe's school days in Richmond. The old Broad Street Theatre, on the site of which now stands Monumental Church, was the scene of his beautiful mother's last appearance before the public. Near Nineteenth and Main she died in a damp cellar in the "Bird in Hand" district, through which ran Shockoe Creek. Eighteen days later the old theatre was burned, and all Richmond was in mourning for the dead.

At the northwest corner of Fifth and Main Streets, opposite the Allan mansion, was the MacKenzie school for girls, which Rosalie Poe attended in Edgar's school days. He was the only young man who enjoyed the much-desired privilege of being received in that hall of learning, and some of the bright girls of the institution beguiled him into revealing the authorship of the satiric verses, "Don Pompioso," which caused their victim, a wealthy and popular young gentleman of Richmond, to quit the city with undue haste. The verses were the boy's revenge upon "Don Pompioso" for insulting remarks about the position of Poe as the son of stage people.

On Franklin Street, between First and Second, was the Ellis home, where Poe, with Mr. and Mrs. Allan, lived for a time after their return from England. On North Fifth Street, near Clay, still stood the cottage that was the next home of the Allans. At the southeast corner of Eleventh and Broad Streets was the school which Poe had attended, afterward the site of the Powhatan Hotel. Near it was the home of Mrs. Stanard, whose memory comes radiantly down to us in the lines "To Helen."

Ever since the tragedy of the Hellespont, it has been the ambition of poets to perform a noteworthy swimming feat, and one of Poe's schoolboy memories was of his six-mile swim from Ludlam's Wharf to Warwick Bar.

On May 16, 1836, in Mrs. Yarrington's boarding-house, at the corner of Twelfth and Bank Streets, Poe and Virginia Clemm were married. The house was burned in the fire of 1865.

In January, 1837, Poe left the Messenger and went north, after which most of his work was done in New York and Philadelphia. "The Fall of the House of Usher" was written when he lived on Sixth Avenue, near Waverley Place, and "The Raven" perched above his chamber door in a house on the Bloomingdale Road, now Eighty-Fourth Street.

When living in Philadelphia Poe went to Washington for the double purpose of securing subscribers for his projected magazine, and of gaining a government appointment. The house in which he stayed during his short and ill-starred sojourn in the Capital is on New York Avenue, on a terrace with steps to a landing whence a longer flight leads to a side entrance lost in a greenery of dark and heavy bushes. On the opposite side is a small, square veranda. The building, which is two stories and a half high, was apparently a cheerful yellow color in the beginning, but it has become dingy with time and weather. The scars of its long battle with fate give it the appearance of being about to crumble and crash, after the fashion of the "House of Usher." It has windows with gloomy casements, opening even with the ground in the first story, and in the second upon a narrow balcony. A sign on the front of the building invites attention to a popular make of glue.[1]

In 1849, about two years after the passing of the gentle soul of Virginia, Poe returned to Richmond. He went first to the United States Hotel, at the southwest corner of Nineteenth and Main Streets, in the "Bird in Hand" neighborhood where he had looked for the last time on the face of his young mother. He soon removed to the "Swan," because it was near Duncan Lodge, the home of his friends, the MacKenzies, where his sister Rose had found protection. The Swan was a long, two-storied structure with combed roof, tall chimneys at the ends, and a front piazza with a long flight of steps leading down to the street. It was famous away back in the beginning of the century, having been built about 1795. When it sheltered Poe it wore a look of having stood there from the beginning of time and been forgotten by the passing generations.

Duncan Lodge, now an industrial home, was then a stately mansion, shaded by magnificent trees. Here Poe spent much of his time, and one evening in this friendly home he recited "The Raven" with such artistic effect that his auditors induced him to give it as a public reading at the Exchange Hotel. Unfortunately, it was in midsummer, and both literary Richmond and gay Richmond were at seashore and mountain, and there were few to listen to the poem read as only its author could read it. Later in the same hall he gave, with gratifying success, his lecture on "The Poetic Principle."

In early September, with some friends, he spent a Sunday in the Hygeia Hotel at Old Point. At the request of one of the party he recited "The Raven," "Annabel Lee," and "Ulalume," saying that the last stanza of "Ulalume" might not be intelligible to them, as it was not to him and for that reason had not been published. Even if he had known what it meant, he objected to furnishing it with a note of explanation, quoting Dr. Johnson's remark about a book, that it was "as obscure as an explanatory note."

Miss Susan Ingram, an old friend of Poe, and one of the party at Old Point, tells of a visit he made at her home in Norfolk following the day at Point Comfort. Noting the odor of orris root, he said that he liked it because it recalled to him his boyhood, when his adopted mother kept orris root in her bureau drawers, and whenever they were opened the fragrance would fill the room.

Near old St. John's in Richmond was the home of Mrs. Shelton, who, as Elmira Royster, was the youthful sweetheart from whom Poe took a tender and despairing farewell when he entered the University of Virginia. Here he spent many pleasant evenings, writing to Mrs. Clemm with enthusiasm of his renewed acquaintance with his former lady-love.

Next to the last evening that Poe spent in Richmond he called on Susan Talley, afterward Mrs. Weiss, with whom he discussed "The Raven," pointing out various defects which he might have remedied had he supposed that the world would capture that midnight bird and hang it up in the golden cage of a "Collection of Best Poems." He was haunted by the "ghost" which "each separate dying ember wrought" upon the floor, and had never been able to explain satisfactorily to himself how and why, his head should have been "reclining on the cushion's velvet lining" when the topside would have been more convenient for any purpose except that of rhyme. But it cannot be demanded of a poet that he should explain himself to anybody, least of all to himself. To his view, the shadow of the raven upon the floor was the most glaring of its impossibilities. "Not if you suppose a transom with the light shining through from an outer hall," replied the ingenious Susan.

When Poe left the Talley home he went to Duncan Lodge, a short distance away, and spent the night. The next night he was at Sadler's Old Market Hotel, leaving early in the morning for Philadelphia, but stopping in Baltimore, where came to him the tragic, mysterious end of all things.

Poe knew men as little as he knew any of the other every-day facts of life. In the depths of that ignorance he left his reputation in the hands of the only being he ever met who would tear it to shreds and throw it into the mire.

SIDNEY LANIER

In my memory-gallery hangs a beautiful picture of the Lanier home as I saw it years ago, on High Street in Macon, Georgia, upon a hillock with greensward sloping down on all sides. It is a wide, roomy mansion, with hospitality written all over its broad steps that lead up to a wide veranda on which many windows look out and smile upon the visitor as he enters. One tall dormer window, overarched with a high peak, comes out to the very edge of the roof to welcome the guest. Two, smaller and more retiring, stand upon the verge of the high-combed house-roof and look down in friendly greeting. There are tall trees in the yard, bending a little to touch the old house lovingly.

Far away stretched the old oaks that girdled Macon with greenery, where Sidney Lanier and his brother Clifford used to spend their schoolboy Saturdays among the birds and rabbits. Near by flows the Ocmulgee, where the boys, inseparable in sport as well as in the more serious aspects of life, were wont to fish. Here Sidney cut the reed with which he took his first flute lesson from the birds in the woods. Above the town were the hills for which the soul of the poet longed in after life.

Macon was the "live" city of middle Georgia. She made no effort to rival Richmond or Charleston as an educational or literary centre, but she had an admirable commercial standing, and offered a generous hospitality that kept her in fond remembrance. In the Macon post-office Sidney Lanier had his first business experience, to offset the drowsy influence of sleepy Midway, the seat of Oglethorpe College, where he continued his studies after completing the course laid out in the "'Cademy" under the oaks and hickories of Macon.

January 6, 1857, Lanier entered the sophomore class of Oglethorpe, where it was unlawful to purvey any commodity, except Calvinism, "within a mile and a half of the University"—a sad regulation for college boys, who, as a rule, have several tastes unconnected with religious orthodoxy.

Lanier carried with him the "small, yellow, one-keyed flute" which had superseded the musical reed provided by Nature, and practised upon it so fervently that a college-mate said that he "would play upon his flute like one inspired."

Montvale Springs, in the mountains of Tennessee, where Sidney's grandfather, Sterling Lanier, built a hotel in which he gave his twenty-five grandchildren a vacation one summer, still holds the memory of that wondrous flute and yet more marvellous nature among the "strong, sweet trees, like brawny men with virgins' hearts." From its ferns and mosses and "reckless vines" and priestly oaks lifting yearning arms toward the stars, Lanier returned to Oglethorpe as a tutor. Here amid hard work and haunting suggestions of a coming poem, "The Jacquerie," he tried to work out the problem of his life's expression.

When the guns of Fort Sumter thundered across Sidney Lanier's dreams of music and poetry, he joined the Macon volunteers, the first company to march from Georgia into Virginia. It was stationed near Norfolk, camping in the fairgrounds in the time that Lanier describes as "the gay days of mandolin and guitar and moonlight sails on the James River." Life there seems not to have been "all beer and skittles," or the poetic substitutes therefor, for he goes on to say that their principal duties were to picket the beach, their "pleasures and sweet rewards of toil consisting in ague which played dice with our bones, and blue mass pills that played the deuce with our livers."

In 1862, the Company went to Wilmington, North Carolina, where they indulged "for two or three months in what are called the 'dry shakes of the sand-hills,' a sort of brilliant tremolo movement." The time not required for the "tremolo movement" was spent in building Fort Fischer, until they were ordered to Drewry's Bluff, and then to the Chickahominy, where they took part in the Seven Days' fight.

Even war places were literary shrines for Lanier, for wherever he chanced to be he was constantly dedicating himself anew to the work of his life. In Petersburg he studied in the Public Library. In that old town he first saw General R.E. Lee, and watched his calm face until he "felt that the antique earth returned out of the past and some mystic god sat on a hill, sculptured in stone, presiding over a terrible, yet sublime, contest of human passions"—perhaps the most poetic conception ever awakened by the somewhat familiar view of an elderly gentleman asleep under the influence of a sermon on a drowsy mid-summer day. Writing to his father from Fort Boykin, he asks him to "seize at any price volumes of Uhland, Lessing, Schelling, Tieck."

In the spring of 1863, on a visit to his old home in Macon, Lanier met Miss Mary Day and promptly fell in love, a fortunate occurrence for him, in that he secured an inspiring companion in his short and brilliant life, and for us because it is to her loving care that we owe the preservation of much of his finest work. On the return to Virginia, he and his brother Clifford had as companions the charming Mrs. Clement C. Clay and her sister, who wanted escorts from Macon to Virginia. She claims to have bribed them with "broiled partridges, sho' 'nuf sugar, and sho' 'nuf butter and spring chickens, 'quality size,'" to which allurements the youthful poets are alleged to have succumbed with grace and gallantry. I recall an evening that General Pickett and I spent with Mrs. Clay at the Spotswood Hotel, when she told us of her trip from Macon, and her two poet escorts. I remember that Senator Vest was present and played the violin while Senator and Mrs. Clay danced.

Sidney Lanier said of his experience at Fort Boykin, on Burwell's Bay, that it was in many respects "the most delicious period" of his life. It may be that no other young soldier found so much of romance and poetry in the service of Mars or put so much of it into the lives of those around him. There are old men, now, who in their youth lived on the James River, in whose hearts the melody of Sidney Lanier's flute yet lingers in golden fire and dewy flowering. At Fort Boykin he decided the question of his vocation, writing to his father so eloquent a letter upon the desirability of pursuing his tastes, rather than trying to follow the paternal footsteps in a profession for which he had no talent, that his father relinquished all hope of making a lawyer of his gifted son.

In Wilmington, North Carolina, Lanier served as signal officer until he was captured and taken to the prison camp at Point Lookout, in which gloomy place was developed the disease which in a few years deprived literature and music of a light that would have sparkled in beauty through the mists of centuries. Imprisonment did not serve as an interruption to the work of the student, for even a prison cell was a shrine to the radiant gods of Lanier's vision. Probably Heine and Herder were never before translated in surroundings so little congenial to those masters of poesy. One of his fellow-prisoners said that Lanier's flute "was an angel imprisoned with us to cheer and console us." To the few who are left to remember him at that time, the waves of the Chesapeake, with the sandy beach sweeping down to kiss the waters, and the far-off dusky pines, are still melodious with that music.

After his release he was taken to the Macon home, where he was dangerously ill for two months, being there when General Wilson captured the town and Mr. Jefferson Davis and Senator Clement C. Clay were brought to the Lanier house on their gloomy journey to Fortress Monroe. In that month Lanier's mother died of consumption, and he spent the summer months at home with his father and sister. In the autumn he taught on a large plantation nine miles from Macon, where, with "mind fairly teeming with beautiful things," he was shut up in the "tare and tret" of the school-room. He spent the winter at Point Clear on Mobile Bay, breathing in health with the sea-breezes and the air that drifted fragrantly through the pines.

As clerk in the Exchange Hotel in Montgomery, the property of his grandfather and his uncles, he may have found no more advantageous a field for his "beautiful things" than in the Georgia school-room, but even in that "dreamy and drowsy and drone-y town" there was some life "late in the afternoon, when the girls come out one by one and shine and move, just as the stars do an hour later." But Lanier was as patient and self-contained in peace as he had been brave in war, and he accepted the drowsy life of Montgomery as he had accepted the romance and adventures of Fort Boykin, on Sundays playing the pipe-organ in the Presbyterian Church, and spending his leisure in finishing "Tiger Lilies," begun in the wild days of '63, on Burwell's Bay. In 1867 he returned to Macon, where in September he read the proof of his book, his one effort at romance-writing, chiefly noticeable for its musical element. The fluting of the author is recalled by the description of the hero's flute-playing: "It is like walking in the woods among wild flowers just before you go into some vast cathedral."

The next winter Sidney Lanier was teaching in Prattville, Alabama, a town built on a quagmire by Daniel Pratt, of whom one of his negroes said his "Massa seemed dissatisfied with the way God had made the earth and he was always digging down the hills and filling up the hollows." Prattville was a small manufacturing town, and Lanier was about as appropriately placed there as Arion would have been in a tin-shop, but he kept his humorous outlook on life, departing from his serenity so far as to make his only attempts at expressing in verse his political indignation, the results of which he did not regard as poetry, and they do not appear in the collection of his poems. His muse was better adapted to the harmonies than to the discords of life. Some lines written then furnish a graphic picture of conditions in the South at that time:

Young Trade is dead,

And swart Work sullen sits in the hillside fern

And folds his arms that find no bread to earn,

And bows his head.

In 1868, after Lanier's marriage, he took up the practice of law in his father's office in Macon. In that town he made his eloquent Confederate Memorial address, April 26, 1870.

Lanier, to whom "Home" meant all that was radiant and joyous in life, wrote to Paul Hamilton Hayne that he was "homeless as the ghost of Judas Iscariot." He was thrust upon a wandering existence by the always unsuccessful attempt to find strength enough to do his work. At Brunswick he found the scene of his Marsh poems in "the length and the breadth and the sweep of the marshes of Glynn," in which he reaches his depth of poetic feeling and his height of poetic expression.

From Lookout Mountain he wrote Hayne that at about midnight he had received his letter and poem, and had read the poem to some friends sitting on the porch, among them Mr. Jefferson Davis. From Alleghany Springs he wrote his wife that new strength and new serenity "continually flash from out the gorges, the mountains, and the streams into the heart and charge it as the lightnings charge the earth with subtle and heavenly fires." Lanier's soul belonged to music more than to any other form of art, and more than any other has he linked music with poetry and the ever-varying phenomena of Nature. Of a perfect day in Macon he wrote:

"If the year was an orchestra, to-day would be the calm, passionate, even, intense, quiet, full, ineffable flute therein."

In November, 1872, Lanier went to San Antonio in quest of health, which he did not find. Incidentally, he found hitherto unrevealed depths of feeling in his "poor old flute" which caused the old leader of the Maennerchor, who knew the whole world of music, to cry out with enthusiasm that he had "never heard de flude accompany itself pefore."

That part of his musical life which Sidney Lanier gave to the world was for the most part spent in Baltimore, where he played in the Peabody Orchestra, the Germania Maennerchor, and other music societies. An old German musician who used to play with him in the Orchestra told me that Lanier was the finest flutist he had ever heard.

It was in Baltimore, too, that he gave the lectures which resulted in his most important prose-writings, "The Science of English Verse," "The English Novel," "Shakespeare and His Forerunners."

In August, 1874, at Sunnyside, Georgia, amid the loneliness of abandoned farms, the glory of cornfields, and the mysterious beauty of forest, he wrote "Corn," the first of his poems to attract the attention of the country. It was published in Lippincott's in 1875. Charlotte Cushman was so charmed by it that she sought out the author in Baltimore, and the two became good friends.

At 64 Centre Street, Baltimore, Lanier wrote "The Symphony," which he said took hold of him "about four days ago like a real James River ague, and I have been in a mortal shake with the same, day and night, ever since," which is the only way that a real poem or real music or a real picture ever can get into the world. He says that he "will be rejoiced when it is finished, for it verily racks all the bones of my spirit." It appeared in Lippincott's, June, 1875.

Lanier was at 66 Centre Street, Baltimore, when he wrote the words of the Centennial Cantata, which he said he "tried to make as simple and candid as a melody of Beethoven." He wrote to a friend that he was not disturbed because a paper had said that the poem of the Cantata was like a "communication from the spirit of Nat Lee through a Bedlamite medium." It was "but a little grotesque episode, as when a catbird paused in the midst of the most exquisite roulades and melodies to mew and then take up his song again."

In December of that year he was compelled to seek a milder climate in Florida, taking with him a commission to write a book about Florida for the J.B. Lippincott Company. Upon arriving at Tampa, he wrote to a friend:

Tampa is the most forlorn collection of little one-story frame houses imaginable, and as May and I walked behind our landlord, who was piloting us to Orange Grove Hotel, our hearts fell nearer and nearer towards the sand through which we dragged. Presently we turned a corner and were agreeably surprised to find ourselves in front of a large three-story house with old nooks and corners, clean and comfortable in appearance and surrounded by orange trees in full fruit. We have a large room in the second story, opening upon a generous balcony fifty feet long, into which stretch the liberal arms of a fine orange tree holding out their fruitage to our very lips. In front is a sort of open plaza containing a pretty group of gnarled live-oaks full of moss and mistletoe.

In May he made an excursion of which he wrote:

For a perfect journey God gave us a perfect day. The little Ocklawaha steamboat Marion—a steamboat which is like nothing in the world so much as a Pensacola gopher with a preposterously exaggerated back—had started from Palatka some hours before daylight, having taken on her passengers the night previous; and by seven o'clock of such a May morning as no words could describe, unless words were themselves May mornings, we had made the twenty-five miles up the St. John's to where the Ocklawaha flows into that stream nearly opposite Welaka, one hundred miles above Jacksonville.

It was on this journey that he saw the most magnificent residence that he had ever beheld, the home of an old friend of his, an alligator, who possessed a number of such palatial mansions and could change his residence at any time by the simple process of swimming from one to another.

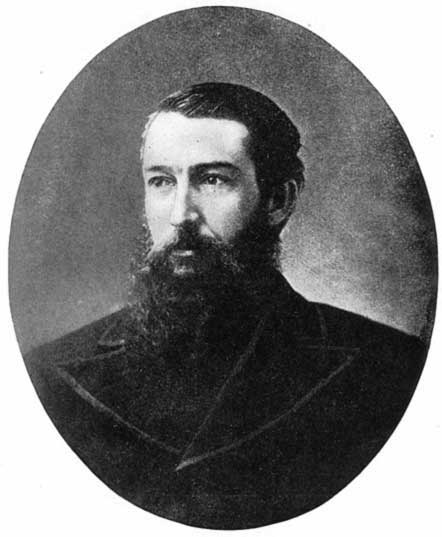

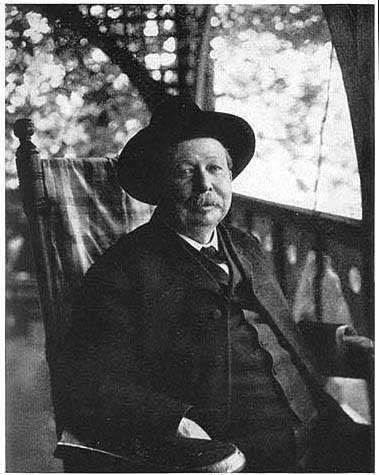

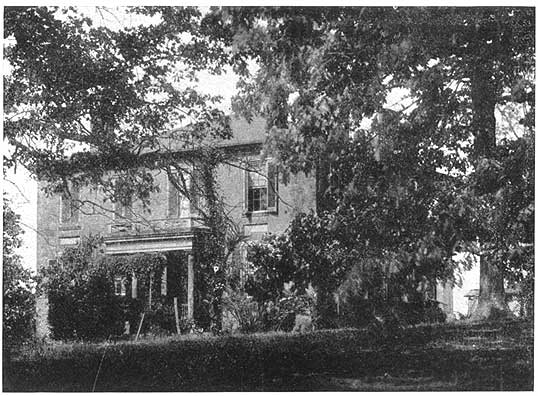

SIDNEY LANIER

From a photograph owned by H.W. Lanier

On his return to Baltimore he lived at 55 Lexington in four rooms arranged as a French flat. He makes mention of a gas stove "on which my comrade magically produces the best coffee in the world, and this, with fresh eggs (boiled through the same handy little machine), bread, butter, and milk, forms our breakfast." December 3 he writes from the little French flat, announcing that he "has plunged in and brought forth captive a long Christmas poem for Every Saturday," a Baltimore weekly publication. The poem was "Hard Times in Elfland." He says, "Wife and I have been to look at a lovely house with eight rooms and many charming appliances," whereof the rent was less than that of the four rooms.

The next month he writes from 33 Denmead Street, the eight-room house, to which he had gone, with the attendant necessity of buying "at least three hundred twenty-seven household utensils" and "hiring a colored gentlewoman who is willing to wear out my carpets, burn out my range, freeze out my water-pipes, and be generally useful." He mentions having written a couple of poems, and part of an essay on Beethoven and Bismarck, but his chief delight is in his new home, which invests him with the dignity of paying taxes and water rates. He takes the view that no man is a Bohemian who has to pay water rates and street tax.

In addition to supporting his new dignity he finds time and strength for his usual work, and he writes on January 30, 1878, "I have been mainly at work on some unimportant prose matter for pot-boilers, but I get off a short poem occasionally, and in the background of my mind am writing my Jacquerie." Unfortunately, "Jacquerie" remained in the background of his mind, with the exception of two songs—all we have to indicate what a stirring presentation our literature might have had of the fourteenth century awakening of "Jacques Bonhomme," that early precursor of the more terrible arousing in 'Ninety-Three.

In the latter part of the year Lanier was living at Number 180 St. Paul Street, and in December he wrote to a friend:

"Bayard Taylor's death slices a huge cantle out of the world.... It only seems that he has gone to some other Germany a little farther off.... He was such a fine fellow, one almost thinks he might have talked Death over and made him forego his stroke."

At Bayard Taylor's home, where Lanier visited, were two immense chestnut trees, much loved by the two poets. Mrs. Taylor wrote that one of the trees died soon after the death of its poet owner. The other lingered until a short time after the passing of Lanier. It was in connection with the lines of the "Cantata," written in the Baltimore home of the Southern poet, that the poet friends began a long-continued series of letters which one loves to read on a winter night, when the winds are battling with the world outside, and the fire gleams redly in the open grate, and the lamp burns softly on the library table, and all things invite to poetic dreams.

November 12, 1880, Sidney Lanier wrote to his publisher a letter of appreciation of the beautiful work done upon his volume, "The Boy's King Arthur." It is dated at Number 435 North Calvert Street, the latest Baltimore address that we have.

The distinction Sidney Lanier achieved as first flutist in the orchestra of the Peabody Institute led to an offer of a position in the Thomas Orchestra, which the condition of his health did not permit him to accept.

In the summer of 1880 his "Science of English Verse" was published. "Shakespeare and His Forerunners" resulted from his work with his classes in Elizabethan Poetry. "The English Novel" is the course of lectures on "Personality Illustrated by the Development of Fiction," delivered at Johns Hopkins University in the winter of 1880-'81. As we read the printed work in its depth and strength, we do not realize that his wife took the notes from his whispered dictation, and that his auditors as they listened trembled lest, with each sentence, that deep musical voice should fall on eternal silence. All this while he had been working at lectures and boys' books, when, as he said, "a thousand songs are singing in my heart that will certainly kill me if I do not utter them soon." One of the thousand, "Sunrise," he uttered with a temperature of 104 degrees burning out his life, but it is full of the rapture of the dawn.

To the pines of North Carolina the poet was taken, in the hope that they might give him of their strength. But the wind-song through their swaying branches lulled him to his last earthly sleep. On the 7th of September the narrow stream of his earthly existence broadened and deepened and flowed triumphantly into the great ocean of Eternal Life.

PAUL HAMILTON HAYNE

"Why are not your countrymen all poets, surrounded as they are by beautiful things to inspire them?" I asked a young Swiss.

"Because," he replied, "my people are so accustomed to beauty that it has no influence upon them."

They had never known anything but beauty: there were no sharp contrasts to clash, flint-like, and strike out sparks of divine fire.

Had the beauty of old Charleston produced the same negative effect, Southern literature would have suffered a distinct loss—if that may be regarded as lost which has never been possessed. For centuries the Queen of the Sea stood in a vision of splendor, the tumultuous waves of the Atlantic dashing at her feet, eternal sunshine crowning her royal brow. Her gardens were stately with oleanders and pomegranates, brilliant with jonquils and hyacinths, myrtle and gardenia. Roses of the olden time, Lancaster and York and the sweet pink cinnamon, breathed the fragrance of days long past. The hills that environed her were snowy with Cherokee roses and odorous with jasmine and honeysuckle. Her people dwelt in mansions in the corridors of which ancestral ghosts from Colonial days kept guard.

In old Charleston that goes back in history almost a century before the Revolution and extends to the opening of the Sixties—the old Queen City by the Sea, which now few are left to remember—was a circle of congenial creative souls just before the first shot at Fort Sumter heralded the destruction of the old-time life of the Colonial city. William Gilmore Simms was the head and mentor of the brilliant little band, and the much younger men, Paul Hamilton Hayne and Henry Timrod, were the fiery souls that gave it the mental electricity necessary to furnish the motive power. Through all the coming days of trial and hardship, of aspiration and defeat, of watching from the towers of high achievement or lying prone in the valley of failure, not one of that little circle ever lost the golden memory of those magic evenings in the home of the novelist and poet, the thinker and dreamer, William Gilmore Simms, the intellectual father of them all.

At that time in the old city was another picturesque home that harked back to Colonial days—stately, veranda-circled, surrounded by that fascinating atmosphere of history and poetry known to those old dwellings alone of all the structures of the New World: the home of the Southern poet of Nature, Paul Hamilton Hayne. Its many-windowed front looked cheerfully out upon a wide lawn radiant with flowers of bygone fashion, loved by the poets of olden times, and bright with the greenery that kept perpetual summer around the historic dwelling. This beautiful pre-Revolutionary home was burned in the bombardment of Charleston, and with it was destroyed the library that had been the pride of the poet's heart.

In this old home the Poet of the Pines was born of a family that looked back to the opening days of the eighteenth century, when Charleston was young, glowing with the beauty of her birth into the forests of the New World, wearing proudly the tiara of her loyalty to King and Crown. Looking back along the road that stretched between the first Hayne, who helped to make of the old city a memory to be cherished on the page of history and a picture on the canvas of the present to awaken admiration, and the young soul that looked with poetic vision on the beginning of the new era, one sees a long succession of brilliant names and powerful figures.

Paul Hayne was the great-grand-nephew of "the Martyr Hayne," who has given to Charleston her only authentic ghost-story, the scene of which was a brick dwelling which stood till 1896 at the corner of Atlantic and Meeting Streets. Colonel Isaac H. Hayne, a soldier of the Revolution, secured a parole, that he might be with his dying wife. While on parole he was ordered to fight against his country. Rather than be forced to the crime of treason, he broke his parole, was captured and condemned to death. From her beautiful, mahogany-panelled drawing-room in that old home where the two streets cross, his sister-in-law, who had gone with his two little children to plead for his life, watched as he passed on his way from the vault of the old Custom House, used then as a prison, to the gallows. "Return, return to us!" she called in an agony of grief. As he walked on he replied, "If I can I will." It is said that his old negro mammy, to whom he was always "my chile," ran out to the gate with the playthings she had fondly cherished since the days when they were to him irresistible attractions, crying, "Come back! Come back!" To both calls his heart responded with such longing love that when the soul was released, the old home knew the step and the voice again. Ever afterward when eventide fell, one standing at that window would hear a ghostly voice from the street below and steps upon the stairs and in the hall; footsteps of one coming—never going.

Paul Hamilton Hayne's uncle, Colonel Arthur P. Hayne, fought under Jackson at New Orleans, and was afterward United States Senator. Paul was nephew of Robert Y. Hayne, whose career as a statesman and an orator won for him a fame that has not faded with the years. With this uncle, Paul found a home in his orphaned childhood.

Of his sailor father, Lieutenant Hayne, his shadowy memory takes form in a poem, one stanza of which gives us a view of the brave seaman's life and death:

He perished not in conflict nor in flame,

No laurel garland rests upon his tomb;

Yet in stern duty's path he met his doom;

A life heroic, though unwed to fame.

Though he pathetically mourns:

Never in childhood have I blithely sprung

To catch my father's voice, or climb his knee,

still

Love limned his wavering likeness on my soul,

Till through slow growths it waxed a perfect whole

Of clear conceptions, brightening heart and mind.

That clear conception remained a lifelong treasure in the poet's heart.

Through a great ancestral corridor had Paul Hamilton Hayne descended, with soul enjewelled with all the gems of character and thought that had sparkled in the long gallery through which he had travelled into the earth-light.

In the school of Mr. Coates, in Charleston, he was fitted to enter Charleston College, a plain, narrow-fronted structure with six severely classic columns supporting the façade. It stood on the foundation of the "old brick barracks" held by the Colonial troops through a six-weeks siege by twelve thousand British regulars under Sir Henry Clinton.

Hayne satisfied the hunger and thirst of his excursive and ardent mind by browsing in the Charleston Library on Broad and Church streets. It may be that sometimes, on his way to that friendly resort, he passed the old house on Church Street which once sheltered General Washington; a substantial three-storied building with ornamental woodwork which might cause its later use as a bakery to seem out of harmony to any but chefs with high ideals of their art.

The Library of old Charleston was composed chiefly of English classics and the literature of France in the olden time when Europe furnished us with something more than anarchy, clothes, and bargain-counter titles. A sample of the Young America of that early day asked an old gentleman, "Why are you always reading that old Montaigne?" The reply was, "Why, child, there is in this book all that a gentleman needs to think about," with the discreet addition, "Not a book for little girls, though." If we find in our circle of poets a certain stateliness of style scarcely to be looked for in a somewhat new republic that might be expected to rush pell-mell after an idea and capture it by the sudden impact of a lusty blow, after the manner of the minute-men catching a red-coat at Lexington; if we observe in their writing old world expressions that woo us subtly, like the odor of lavender from a long-closed linen chest, we may attribute it to the fact that aristocratic old Charleston, though the first to assert her independence of the political yoke, yet clung tenaciously to the literary ideals of the Old World.

On Meeting Street was Apprentices' Library Hall, where Glidden led his hearers through the intricacies of Egyptian Archæology. Here Agassiz sometimes lectured on Zoölogy, and our youthful poet may have watched animals from the jungle climb up the blackboard at the touch of what would have been only a piece of chalk in any other hand, but became a magic creative force under the guidance of that wizard of science. Here he could have followed with Thackeray the varying fortunes and ethic vagaries of the royal Georges. His poetic soul may have kindled with the fire of Macready's "Hamlet" when, thinking that he was too far down the slope of life to hark back to the days of the youthful Dane, he proved that he still had the glow of the olden time in his soul by reading the part as only Macready could. In this old hall he may have looked upon the paintings which inspired him to create his own pictures, luminous with softly tinted word-colors.

Meeting Street seems to have been named with reference to its uses, for here, too, was the old theatre, gone long ago, where Fannie Ellsler danced with a wavering, quivering, shimmering grace that drove humming-birds to despair. In that theatre it may be that Paul Hayne heard Jenny Lind fill the night with a melody which would irradiate his soul throughout life and reproduce itself in the music-tones of his gently cadenced verse. There the ill-fated Adrienne Lecouvreur lived and died again in her wondrous transmigration into the soul of the great Rachel.

When a boy, Hayne's heart may have often thrilled to the voice of the scholarly Hugh Swinton Legare, as he made the heart of some classic old poem live in the music of his organ-tones.

A sensitive soul surrounded by the influences of life in old Charleston had many incentives to high and harmonious expression.

That the Queen City of the Sea did not claim the privilege of the fickleness alleged to be incident to the feminine character is illustrated by the fact that she had but two postmasters in seventy years, a circumstance worthy of note "in days like these, when ev'ry gate is thronged with suitors, all the markets overflow," and the disbursing counter is crowded with claimants for the rewards due for commendable activity in the campaign. One of those two was Peter Bascot, an appointee of Washington. The other was Alfred Huger, "the last of the Barons," who had refused to take the office in the time of Bascot.

In old Charleston the servants were the severest sticklers for propriety, and the butlers of the old families rivalled each other in the loftiness of their standards. Jack, the butler of "the last of the Barons," was wide awake to the demands of his position, and when an old sea captain, an intimate friend of Mr. Huger, dining with the family, asked for rice when the fish was served he was first met with a chill silence. Thinking that he had not been heard, he repeated the request. Jack bent and whispered to him. With a burst of laughter, the captain said, "Judge, you have a treasure. Jack has saved me from disgrace, from exposing my ignorance. He whispered, 'That would not do, sir; we never eats rice with fish.'"

Russell's book-shop on King Street was a favorite place of meeting for the Club which recognized Simms as king by divine right. From these pleasant gatherings grew the thought of giving to Charleston a medium through which the productions of her thought might go out to the world. In April, 1857, appeared Russell's Magazine, bearing the names of Paul Hamilton Hayne and W.B. Carlisle as editors, though upon Hayne devolved all the editorial work and much of the other writing for the new publication. He had helped to keep alive the Southern Literary Messenger after the death of Mr. White and the departure of Poe for other fields of labor, had assisted Richards on the Southern Literary Gazette and had been associate editor of Harvey's Spectator. For Charleston had long been ambitious to become the literary centre of the South. The object of Russell's Magazine was to uphold the cause of literature in Charleston and in the South, and incidentally to stand by the friends of the young editor, who carried his partisanship of William Gilmore Simms so far as to permit the publication of a severe criticism of Dana's "Household Book of Poetry" because it did not include any of the verse of the Circle's rugged mentor. Russell's had a brilliant and brief career, falling upon silence in March, 1860; probably not much to the regret of Paul Hayne, who, while too conscientious to withhold his best effort from any enterprise that claimed him, was too distinctly a poet not to feel somewhat like Pegasus in pound when tied down to the editorial desk.

This quiet life, in which the gentle soul of Hayne, with its delicate sensitiveness, poetic insight, and appreciation of all beauty, found congenial environment, soon suffered a rude interruption. As Charleston was the first to throw off the yoke of Great Britain and draw up a constitution which she thought adapted to independent government, so did she first express the determination of South Carolina to break the bonds that held her turbulent political soul in uncongenial association.

Hayne heard the twelve-hour cannonade of Fort Sumter's hundred and forty guns echoing over the sea, and saw the Stars and Bars flutter above the walls of the old fort. He saw Generals Bee and Johnson come back from Manassas, folded in the battle flag for which they had given their lives, to lie in state in the City Hall at the marble feet of Calhoun, the great political leader whom they had followed to the inevitable end. General Lee was in the old town for a little while. A man said to him, "It is difficult for so many men to abandon their business for the war." The general replied, "Believe me, sir, the business of this generation is the war." In the spirit of this answer Charleston met the crisis so suddenly come upon her.

All the young poet's patriotic love and inherited martial instinct urged him to the battle, but his frail physique withheld him from the field, and he took service as an aide on the staff of Governor Pickens.

At the close of the war, wrecked in health, with only the memory of his beautiful home and library left to him, with not even a piece of the family silver remaining from the "march to the sea," Hayne went to the pine-barrens of Georgia, eighteen miles from Augusta, to build a new home.

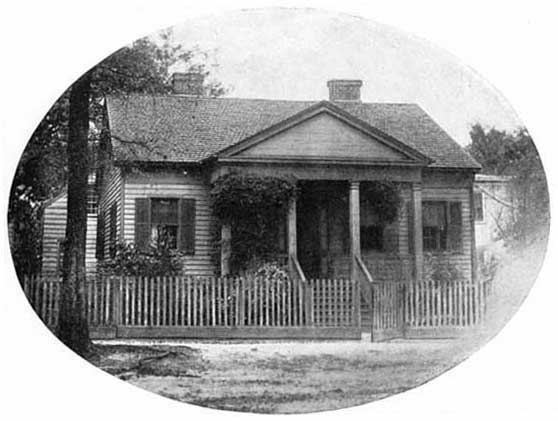

When the first man and woman were sent out from their garden home, it was not as a punishment for sin, but as an answer to their ambitious quest for knowledge and their new-born longing for a wider life. It was not that the gate of Eden was closed upon them; it was that the gates of all the Edens of the world were opened for them and for the generations of their children. One of those gates opened upon the Eden of Copse Hill, where the poet of Nature found a home and all friendly souls met a welcome that filled the pine-barrens with joy for them. Of Copse Hill the poet says:

A little apology for a dwelling was perched on the top of a hill overlooking in several directions hundreds of leagues of pine-barrens there was as yet neither garden nor inclosure near it; and a wilder, more desolate and savage-looking home could hardly have been seen east of the prairies.

What that "little apology of a dwelling" was to him is best pictured in his own words:

On a steep hillside, to all airs that blow,

Open, and open to the varying sky,

Our cottage homestead, smiling tranquilly,

Catches morn's earliest and eve's latest glow;

Here, far from worldly strife and pompous show,

The peaceful seasons glide serenely by,

Fulfil their missions and as calmly die

As waves on quiet shores when winds are low.

Fields, lonely paths, the one small glimmering rill

That twinkles like a wood-fay's mirthful eye,

Under moist bay-leaves, clouds fantastical

That float and change at the light breeze's will,—

To me, thus lapped in sylvan luxury,

Are more than death of kings, or empires' fall.

Here with "the bonny brown hand" in his that was "dearer than all dear things of earth" Paul Hayne found a life that was filled with beauty, notwithstanding its moments of discouragement and pain. We like to remember that always with him, helping him bear the burdens of life, was that wifely hand of which the poet could say, "The hand which points the path to heaven, yet makes a heaven of earth."

On sunny days he paced to and fro under the pines, the many windows of his mind opened to the studies in light and shade and his soul attuned to the music of the drifting winds and the whispering trees. When Nature was in darkened mood and gave him no invitation to the open court wherein she reigned, he walked up and down his library floor, engrossed with some beautiful thought which, in harmonious garb of words, would go forth and bless the world with its music.

The study, of which he wrote:

This is my world! within these narrow walls

I own a princely service

was perhaps as remarkable a room as any in which student ever spent his working hours, the walls being papered wholly with cuts from papers and periodicals. The furniture was decorated in the same way, even to the writing desk, which was an old work bench left by some carpenters. All had been done by the "bonny brown hands" that never wearied in loving service.

Many of his friends made pilgrimages to the little cottage on the hill, where they were cordially welcomed by the poet, who, happy in his home with his wife and little son, lived among the flowers which he tended with his own hands, surrounded by the majesty of the pines whose

Passion and mystery murmur through the leaves,—

Passion and mystery touched by deathless pain,

Whose monotone of long, low anguish grieves

For something lost that shall not live again.

Hither came Henry Timrod, doomed to failure, loss, and early death, but with soul eternally alive with the fires of genius. In the last days of his sad and broken life William Gilmore Simms came to renew old memories and recount the days when life in old Charleston was iridescent as the waves that washed the feet of the Queen of the Sea. Congenial spirits they were who met in that charming little study where Paul Hayne walked "the fields of quiet Arcadies" and

... gleamings of the lost, heroic life

Flashed through the gorgeous vistas of romance.

Hayne had the subtle power of touching the friendliness in the hearts of those who were far away, as well as of the comrades who had walked with him along the road of life. Often letters came from friends in other lands, known to him only by that wireless intuitional telegraphy whereby kindred souls know each other, though hands have not met nor eyes looked into eyes. Many might voice the thought expressed by one: "I may boast that Paul Hayne was my friend, though it was never my good fortune to meet him." Many a soul was upheld and strengthened by him, as was that of a man who wrote that he had been saved from suicide by reading the "Lyric of Action." His album held autographed photographs of many writers, among them Charles Kingsley, William Black, and Wilkie Collins. He cherished an ivy vine sent him by Blackmore from Westminister Abbey.

Hayne's many-windowed mind looked out upon all the phases of the beauty of Nature. Her varied moods found in him a loving response. He awaited her coming as the devotee at the temple gate waits for the approach of his Divinity:

I felt, through dim, awe-laden space,

The coming of thy veiled face;

And in the fragrant night's eclipse

The kisses of thy deathless lips,

Like strange star-pulses, throbbed through space!

Whether it is drear November and

But winds foreboding fill the desolate night

And die at dawning down wild woodland ways,

or in May "couched in cool shadow" he hears

The bee-throngs murmurous in the golden fern,

The wood-doves veiled by depths of flickering green,

for him the music of the spheres is in it all. Whether at midnight

The moon, a ghost of her sweet self,

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Creeps up the gray, funereal sky wearily, how wearily,

or morning comes "with gracious breath of sunlight," it is a part of glorious Nature, his star-crowned Queen, his sun-clad goddess.

To no other heart has the pine forest come so near unfolding its immemorial secret. That poet-mind was a wind-harp, and its quivering strings echoed to every message that came from the dim old woods on the "soft whispers of the twilight breeze," the flutterings of the newly awakened morn or the crash of the storm. "The Dryad of the Pine" bent "earth-yearning branches" to give him loving greeting and receive his quick response:

Leaning on thee, I feel the subtlest thrill

Stir thy dusk limbs, tho' all the heavens are still,

And 'neath thy rings of rugged fretwork mark

What seems a heart-throb muffled in the dark.

"The imprisoned spirits of all winds that blow" echoed to his ear from the heart of the pine-cone fallen from "the wavering height of yon monarchal pine."

When a glorious pine, to him a living soul, falls under the axe he hears "the wail of Dryads in their last distress."

In the greenery of his loved and loving pines, with memories happy, though touched to tender sadness by the sorrows that had come to the old-time group of friends, blessed with the companionship of the two loving souls who were dearest to him of all the world, he sang the melodies of his heart till a cold hand swept across the strings of his wonderful harp and chilled them to silence.

In his last year of earth he was invited to deliver at Vanderbilt University a series of lectures on poetry and literature. Before the invitation reached him he had "fallen into that perfect peace that waits for all."

HENRY TIMROD

A writer on Southern poets heads his article on one of the most gifted of our children of song, "Henry Timrod, the Unfortunate Singer."

At first glance the title may seem appropriate. Viewed by the standard set up by the world, there was little of the wine of success in Timrod's cup of life. Bitter drafts of the waters of Marah were served to him in the iron goblet of Fate. But he lived. Of how many of the so-called favorites of Fortune could that be said? Through the mists of his twilit life, he caught glimpses of a sun-radiant morning of wondrous glory.

Thirty years after Timrod's death a Northern critic, writing of the new birth of interest in Timrod's work, said: "Time is the ideal editor." Surely, Editor Time's blue pencil has dealt kindly with our flame-born poet.

In Charleston, December 8, 1829, the "little blue-eyed boy" of his father's verse first opened his eyes upon a world that would give him all its beauty and much of its sadness, verifying the paternal prophecy:

And thy full share of misery

Must fall in life on thee!

In early childhood he was destined to lose the loving father to whom his "shouts of joy" were the sweetest strain in life's harmony.

Henry Timrod and Paul Hayne, within a month of the same age, were seat-mates in school. Writing of him many years later, Hayne tells of the time that Timrod made the thrilling discovery that he was a poet; that being, perhaps, the most exciting epoch in any life. Coming into school one morning, he showed Paul his first attempt at verse-writing, which Hayne describes as "a ballad of stirring adventures and sanguinary catastrophe," which he thought wonderful, the youthful author, of course, sharing that conviction. Convictions are easy at thirteen, even when one has not the glamour of the sea and the romance of old Charleston to prepare the soul for their riveting.

Unfortunately, the teacher of that school thus honored by the presence of two budding poets had not a mind attuned to poesy. Seeing the boys communing together in violation of the rules made and provided for school discipline, he promptly and sharply recalled them to the subjects wisely laid down in the curriculum. Notwithstanding this early discouragement, the youthful poet, abetted by his faithful fellow song-bird, persevered in his erratic way, and Charleston had the honor of being the home of one who has been regarded as the most brilliant of Southern poets.

When Henry Timrod finished his course of study in the chilling atmosphere in which his poetic ambition first essayed to put forth its tender leaflets, he entered Franklin College, in Athens, the nucleus of what is now the University of Georgia. A few years ago a visitor saw his name in pencil on a wall of the old college. The "Toombs oak" still stood on the college grounds, and it may be that its whispering leaves brought to the youthful poet messages of patriotism which they had garnered from the lips of the embryonic Georgia politician. Timrod spent only a year in the college, quitting his studies partly because his health failed, and partly because the family purse was not equal to his scholastic ambition.

Returning to Charleston at a time when that city cherished the ambition to become to the South what Boston was to the North, he helped form the coterie of writers who followed the leadership of that burly and sometimes burry old Mentor, William Gilmore Simms. The young poet seems not to have been among the docile members of the flock, for when Timrod's first volume of poems was published Hayne wrote to Simms, requesting him to write a notice of Timrod's work, not that he (Timrod) deserved it of Simms, but that he (Hayne) asked it of him. It may be that Timrod's recognition of the fact that he could write poetry and that Simms could only try to write it led to a degree of youthful assumption which clashed with the dignity of the older man. The Nestor of Southern literature seems not to have cherished animosity, for he not only noticed Timrod favorably, but in after years, when the poet's misfortunes pressed most heavily upon him, made every possible exertion to give him practical and much needed assistance.

Upon his return from college, Timrod, with some dim fancies concerning a forensic career circling around the remote edges of his imagination, entered the office of his friend, Judge Petigru. The "irrepressible conflict" between Law and Poesy that has been waged through the generations broke forth anew, and Timrod made the opposite choice from that reached by Blackstone. Judging from the character of the rhythmic composition in which the great expounder of English law took leave of the Lyric Muse, his decision was a judicious one. Doubtless that of our poet was equally discreet. When the Club used to gather in Russell's book-shop on King Street, Judge Petigru and his recalcitrant protégé had many pleasant meetings, unmarred by differences as to the relative importance of the Rule in Shelley's Case and the flight of Shelley's Lark.

Henry Timrod was thrust into the literary life of Charleston at a time when that life was most full of impelling force. It was a Charleston filled with memories quite remote from the poetry and imaginative literature which represented life to the youthful writers. It was a Charleston with an imposing background of history and oratory, forensic and legislative, against which the poetry and imagination of the new-comers glittered capriciously, like the glimmering of fireflies against the background of night, with swift, uncertain vividness that suggested the early extinguishing of those quivering lamps. But the heart of Charleston was kindled with a new ambition, and the new men brought promise of its fulfilment.

Others have given us a view of the literary life of Charleston, of her social position, of her place in the long procession of history. To Timrod it was left to give us martial Charleston, "girt without and garrisoned at home," looking "from roof and spire and dome across her tranquil bay." With him, we see her while

Calm as that second summer which precedes

The first fall of the snow,

In the broad sunlight of heroic deeds

The City bides the foe.

Through his eyes we look seaward to where

Dark Sumter, like a battlemented cloud,

Looms o'er the solemn deep.

We behold the Queen City of the Sea standing majestically on the sands, the storm-clouds lowering darkly over her, the distant thunders of war threatening her, and the pale lightnings of the coming tempest flashing nearer,

And down the dunes a thousand guns lie couched,

Unseen, beside the flood—

Like tigers in some Orient jungle crouched

That wait and watch for blood.

We see her in those dark days before the plunge into the darkness has been taken, as

Meanwhile, through streets still echoing with trade,

Walk grave and thoughtful men,

Whose hands may one day wield the patriot's blade

As lightly as the pen.

Thus he gives us the picture of the beautiful city of his love as

All untroubled in her faith, she waits

The triumph or the tomb.

Hayne said that of all who shared the suppers at the hospitable home of Simms in Charleston none perhaps enjoyed them as vividly as Timrod. He chooses the word that well applies to Timrod's life in all its variations. He was vivid in all that he did. Being little of a talker, he was always a vivid listener, and when he spoke, his words leaped forth like a flame.

Russell's book-shop, where the Club used to spend their afternoons in pleasant conversation and discourse of future work, was a place of keen interest to Timrod, and when their discussions resulted in the establishment of Russell's Magazine he was one of the most enthusiastic contributors to the ambitious publication.

While Charleston was not the place of what would be called Timrod's most successful life, it was the scene in which he reached his highest exemplification of Browning's definition of poetry: "A presentment of the correspondence of the universe to the Deity, of the natural to the spiritual, and of the actual to the ideal."

In the environments of Charleston he roamed with his Nature-worshipping mother, who taught him the beauties of clouds and trees and streams and flowers, the glory of the changeful pageantry of the sky, the exquisite grace of the bird atilt on a swaying branch. Through the glowing picture which Nature unfolded before him he looked into the heart of the truth symbolized there and gave us messages from woods and sky and sea. While it may be said that a poet can make his own environment, yet he is fortunate who finds his place where nature has done so much to fit the outward scene to the inward longing.

In Charleston he met "Katie, the Fair Saxon," brown-eyed and with

Entangled in her golden hair

Some English sunshine, warmth and air.

He straightway entered into the kingdom of Love, and that sunshine made a radiance over the few years he had left to give to love and art.

In the city of his home he answered his own "Cry to Arms" when the "festal guns" roared out their challenge. Had his physique been as strong as his patriotism, his sword might have rivaled his pen in reflecting honor upon his beautiful city. Even then the seeds of consumption had developed, and he was discharged from field service. Still wishing to remain in the service of his country, he tried the work of war correspondent, reaching the front just after the battle of Shiloh. Overcome by the horrors of the retreat, he returned to Charleston, and was soon after appointed assistant editor of the Daily South Carolinian, published in Columbia. He removed to the capital, where his prospects became bright enough to permit his marriage to Kate Goodwin, the English girl to whom his Muse pays such glowing tribute.

In May, 1864, Simms was in Columbia, and on his return to "Woodlands" wrote to Hayne that Timrod was in better health and spirits than for years, saying: "He has only to prepare a couple of dwarf essays, making a single column, and the pleasant public is satisfied. These he does so well that they have reason to be so. Briefly, our friend is in a fair way to fatten and be happy."