THE PHYSICIAN IN THE LABRADORToList

Title: The Story of Grenfell of the Labrador: A Boy's Life of Wilfred T. Grenfell

Author: Dillon Wallace

Release date: October 7, 2005 [eBook #16809]

Most recently updated: December 12, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by A www.PGDP.net Volunteer, Jeannie Howse and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note: Throughout the whole book, St.

John's (Newfoundland) is spelled St. Johns.

A list

of typos fixed in this text are listed at the end.

In a land where there was no doctor and no school, and through an evil system of barter and trade the people were practically bound to serfdom, Doctor Wilfred T. Grenfell has established hospitals and nursing stations, schools and co-operative stores, and raised the people to a degree of self dependence and a much happier condition of life. All this has been done through his personal activity, and is today being supported through his personal administration.

The author has lived among the people of Labrador and shared some of their hardships. He has witnessed with his own eyes some of the marvelous achievements of Doctor Grenfell. In the following pages he has made a poor attempt to offer his testimony. The book lays no claim to either originality or literary merit. It barely touches upon the field. The half has not been told.

He also wishes to acknowledge reference in compiling the book to old files and scrapbooks of published articles concerning Doctor Grenfell and his work, to Doctor Grenfell's book Vikings of Today, and to having verified dates and incidents through Doctor Grenfell's Autobiography, published by Houghton Mifflin & Company, of Boston.

D.W.

Beacon, N.Y.

| I. | The Sands of Dee | 11 |

| II. | The North Sea Fleets | 26 |

| III. | On the High Seas | 31 |

| IV. | Down on the Labrador | 39 |

| V. | The Ragged Man in the Rickety Boat | 52 |

| VI. | Overboard! | 61 |

| VII. | In the Breakers | 68 |

| VIII. | An Adventurous Voyage | 74 |

| IX. | In the Deep Wilderness | 83 |

| X. | The Seal Hunter | 99 |

| XI. | Uncle Willy Wolfrey | 109 |

| XII. | A Dozen Fox Traps | 116 |

| XIII. | Skipper Tom's Cod Trap | 126 |

| XIV. | The Saving of Red Bay | 135 |

| XV. | A Lad of the North | 146 |

| XVI. | Making a Home for the Orphans | 158 |

| XVII. | The Dogs of the Ice Trail | 171 |

| XVIII. | Facing an Arctic Blizzard | 183 |

| XIX. | How Ambrose Was Made to Walk | 193 |

| XX. | Lost on the Ice Floe | 203 |

| XXI. | Wrecked and Adrift | 213 |

| XXII. | Saving a Life | 219 |

| XXIII. | Reindeer and Other Things | 225 |

| XXIV. | The Same Grenfell | 233 |

| Facing Page |

|

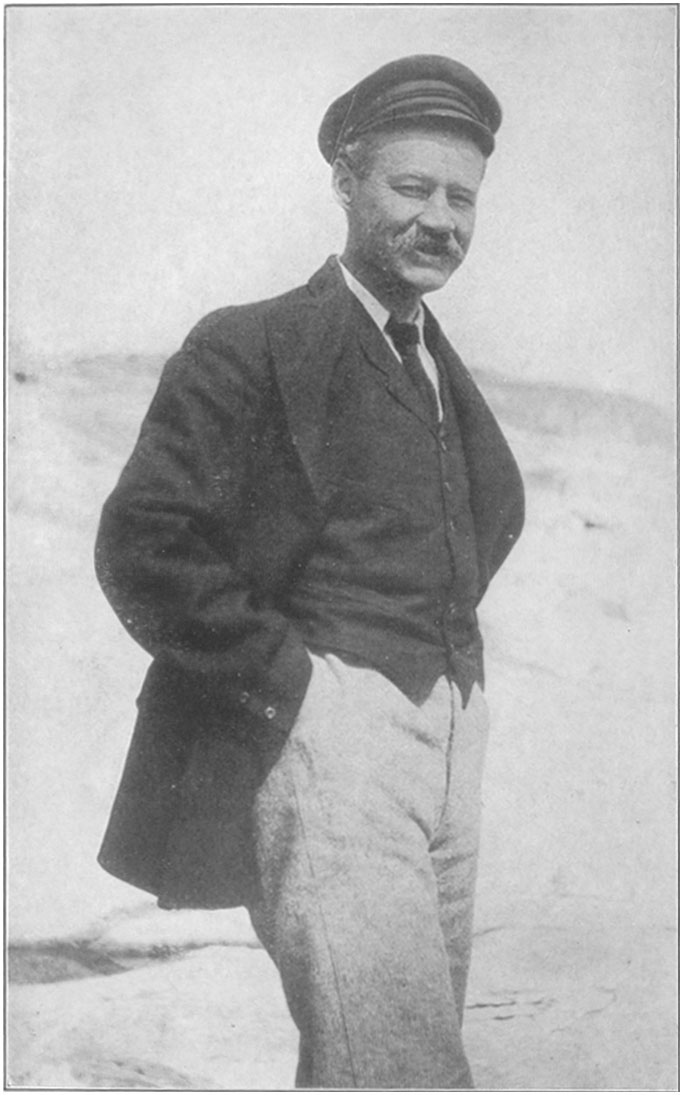

| The Physician in the Labrador | Title |

| The Labrador "Liveyere" | 40 |

| "Sails North to Remain Until the End of Summer, Catching Cod" | 46 |

| The Doctor on a Winter's Journey | 84 |

| "The Trap is Submerged a Hundred Yards or so from Shore" | 130 |

| "Next" | 172 |

| "Please Look at My Tongue, Doctor" | 172 |

| The Hospital Ship, Strathcona | 220 |

| "I Have a Crew Strong Enough to Take You into My District" | 234 |

The first great adventure in the life of our hero occurred on the twenty-eighth day of February in the year 1865. He was born that day. The greatest adventure as well as the greatest event that ever comes into anybody's life is the adventure of being born.

If there is such a thing as luck, Wilfred Thomason Grenfell, as his parents named him, fell into luck, when he was born on February twenty-eighth, 1865. He might have been born on February twenty-ninth one year earlier, and that would have been little short of a catastrophe, for in that case his birthdays would have been separated by intervals of four years, and every boy knows what a hardship it would be to wait four years for a birthday, when every one else is having one every year. There are people, to be sure, who would like their birthdays to be four years apart, but they are not boys.

Grenfell was also lucky, or, let us say, fortunate in the place where he was born and spent his early boyhood. His father was Head Master of Mostyn House, a school for boys at Parkgate, England, a little fishing village not far from the historic old city of Chester. By referring to your map you will find Chester a dozen miles or so to the southward of Liverpool, though you may not find Parkgate, for it is so small a village that the map makers are quite likely to overlook it.

Here at Parkgate the River Dee flows down into an estuary that opens out into the Irish Sea, and here spread the famous "Sands of Dee," known the world over through Charles Kingsley's pathetic poem, which we have all read, and over which, I confess, I shed tears when a boy:

Charles Kingsley and the poem become nearer and dearer to us than ever with the knowledge that he was a cousin of Grenfell, and knew the Sands o' Dee, over which Grenfell tramped and hunted as a boy, for the sandy plain was close by his father's house.

There was a time when the estuary was a wide deep harbor, and really a part of Liverpool Bay, and great ships from all over the world came into it and sailed up to Chester, which in those days was a famous port. But as years passed the sands, loosened by floods and carried down by the river current, choked and blocked the harbor, and before Grenfell was born it had become so shallow that only fishing vessels and small craft could use it.

Parkgate is on the northern side of the River Dee. On the southern side and beyond the Sands of Dee, rise the green hills of Wales, melting away into blue mysterious distance. Near as Wales is the people over there speak a different tongue from the English, and to young Grenfell and his companions it was a strange and foreign land and the people a strange and mysterious people. We have most of us, in our young days perhaps, thought that all Welshmen were like Taffy, of whom Mother Goose sings:

But it was Grenfell's privilege, living so near, to make little visits over into Wales, and he early had an opportunity to learn that Taffy was not in the least like Welshmen. He found them fine, honest, kind-hearted folk, with no more Taffys among them than there are among the English or Americans. The great Lloyd George, perhaps the greatest of living statesmen, is a Welshman, and by him and not by Taffy, we are now measuring the worth of this people who were the near neighbors of Grenfell in his young days.

Mostyn House, where Grenfell lived, overlooked the estuary. From the windows of his father's house he could see the fishing smacks going out upon the great adventurous sea and coming back laden with fish.

Living by the sea where he heard the roar of the breakers and every day smelled the good salt breath of the ocean, it was natural that he should love it, and to learn, almost as soon as he could run about, to row and sail a boat, and to swim and take part in all sorts of water sports. Time and again he went with the fishermen and spent the night and the day with them out upon the sea. This is why it was fortunate that he was born at Parkgate, for his life there as a boy trained him to meet adventures fearlessly and prepared him for the later years which were destined to be years of adventure.

Far up the river, wide marshes reached; and over these marshes, and the Sands of Dee, Grenfell roamed at will. His father and mother were usually away during the long holidays when school was closed, and he and his brothers were left at these times with a vast deal of freedom to do as they pleased and seek the adventure that every boy loves, and on the sands and in the marshes there was always adventure enough to be found.

Shooting in the marshes and out upon the sands was a favorite sport, and when not with the fishermen Grenfell was usually to be found with his gun stalking curlew, oyster diggers, or some other of the numerous birds that frequented the marshes and shores. Barefooted, until the weather grew too cold in autumn, and wearing barely enough clothing to cover his nakedness, he would set out in early morning and not return until night fell.

As often as not he returned from his day's hunting empty handed so far as game was concerned, but this in no wise detracted from the pleasure of the hunt. Game was always worth the getting, but the great joy was in being out of doors and in tramping over the wide flats. With all the freedom given him to hunt, he early learned that no animals or birds were to be killed on any account save for food or purposes of study. This is the rule of every true sportsman. Grenfell has always been a great hunter and a fine shot, but he has never killed needlessly.

Young Grenfell through these expeditions soon learned to take a great deal of interest in the habits of birds and their life history. This led him to try his skill at skinning and mounting specimens. An old fisherman living near his home was an excellent hand at this and gave him his first lessons, and presently he developed into a really expert taxidermist, while his brother made the cases in which he mounted and exhibited his specimens.

His interest in birds excited an interest in flowers and plants and finally in moths and butterflies. The taste for nature study is like the taste for olives. You have to cultivate it, and once the taste is acquired you become extremely fond of it. Grenfell became a student of moths and butterflies. He captured, mounted and identified specimens. He was out of nights with his net hunting them and "sugaring" trees to attract them, and he even bred them. A fine collection was the result, and this, together with one of flowers and plants, was added to that of his mounted birds. In the course of time he had accumulated a creditable museum of natural history, which to this day may be seen at Mostyn House, in Parkgate; and to it have been added specimens of caribou, seals, foxes, porcupines and other Labrador animals, which in his busy later years he has found time to mount, for he is still the same eager and devoted student of nature.

During these early years, with odds and ends of boards that they collected, Grenfell and his brother built a boat to supply a better means of stealing upon flocks of water birds. It was a curious flat-bottomed affair with square ends and resembled a scow more than a rowboat, but it served its purpose well enough, and was doubtless the first craft which the young adventurer, later to become a master mariner, ever commanded. Up and down the estuary, venturing even to the sea, the two lads cruised in their clumsy craft, stopping over night with the kind-hearted fishermen or "sleeping out" when they found themselves too far from home. Many a fine time the ugly little boat gave them until finally it capsized one day leaving them to swim for it and reach the shore as best they could.

At the age of fourteen Grenfell was sent to Marlborough "College," where he had earned a scholarship. This was not a college as we speak of a college in America, but a large university preparatory school.

In the beginning he had a fight with an "old boy," and being victor firmly established his place among his fellow students. Whether at Mostyn House, or later at Marlborough College, Grenfell learned early to use the gloves. It was quite natural, devoted as he was to athletics, that he should become a fine boxer. To this day he loves the sport, and is always ready to put on the gloves for a bout, and it is a mighty good man that can stand up before him. In most boys' schools of that day, and doubtless at Marlborough College, boys settled their differences with gloves, and in all probability Grenfell had plenty of practice, for he was never a mollycoddle. He was perhaps not always the winner, but he was always a true sportsman. There is a vast difference between a "sportsman" and a "sport." Grenfell was a sportsman, never a sport. His life in the open taught him to accept success modestly or failure smilingly, and all through his life he has been a sportsman of high type.

The three years that Grenfell spent at Marlborough College were active ones. He not only made good grades in his studies but he took a leading part in all athletics. Study was easy for him, and this made it possible to devote much time to physical work. Not only did he become an expert boxer, but he had no difficulty in making the school teams, in football, cricket, and other sports that demanded skill, nerve and physical energy.

Like all youngsters running over with the joy of youth and life, he got into his full share of scrapes. If there was anything on foot, mischievous or otherwise, Grenfell was on hand, though his mischief and escapades were all innocent pranks or evasion of rules, such as going out of bounds at prohibited hours to secure goodies. The greater the element of adventure the keener he was for an enterprise. He was not by any means always caught in his pranks, but when he was he admitted his guilt with heroic candor, and like a hero stood up for his punishment. Those were the days when the hickory switch in America, and the cane in England, were the chief instruments of torture.

With the end of his course at Marlborough College, Grenfell was confronted with the momentous question of his future and what he was to do in life. This is a serious question for any young fellow to answer. It is a question that involves one's whole life. Upon the decision rests to a large degree happiness or unhappiness, content or discontent, success or failure.

It impressed him now as a question that demanded his most serious thought. For the first time there came to him a full realization that some day he would have to earn his way in the world with his own brain and hands. A vista of the future years with their responsibilities, lay before him as a reality, and he decided that it was up to him to make the most of those years and to make a success of life. No doubt this realization fell upon him as a shock, as it does upon most lads whose parents have supplied their every need. Now he was called upon to decide the matter for himself, and his future education was to be guided by his choice.

At various periods of his youthful career nearly every boy has an ambition to be an Indian fighter, or a pirate, or a locomotive engineer, or a fireman and save people from burning buildings at the risk of his own life, or to be a hunter of ferocious wild animals. Grenfell had dreamed of a romantic and adventurous career. Now he realized that these ambitions must give place to a sedate profession that would earn him a living and in which he would be contented.

All of his people had been literary workers, educators, clergymen, or officers in the army or navy. There was Charles Kingsley and "Westward Ho." There was Sir Richard Grenvil, immortalized by Tennyson in "The Revenge." There was his own dear grandfather who was a master at Rugby under the great Arnold, whom everybody knows through "Tom Brown at Rugby."

It was the wish of some of his friends and family that he become a clergyman. This did not in the least suit his tastes, and he immediately decided that whatever profession he might choose, it would not be the ministry. The ministry was distasteful to him as a profession, and he had no desire or intention to follow in the footsteps of his ancestors. He wished to be original, and to blaze a new trail for himself.

Grenfell was exceedingly fond of the family physician, and one day he went to him to discuss his problem. This physician had a large practice. He kept several horses to take him about the country visiting his patients, and in his daily rounds he traveled many miles. This was appealing to one who had lived so much out of doors as Grenfell had. As a doctor he, too, could drive about the country visiting patients. He could enjoy the sunshine and feel the drive of rain and wind in his face. He rebelled at the thought of engaging in any profession that would rob him of the open sky. But he also demanded that the profession he should choose should be one of creative work. This would be necessary if his life were to be happy and successful.

Observing the old doctor jogging along the country roads visiting his far-scattered patients, it occurred to Grenfell that here was not only a pleasant but a useful profession. With his knowledge of medicine the doctor assisted nature in restoring people to health. Man must have a well body if he would be happy and useful. Without a well body man's hands would be idle and his brain dull. Only healthy men could invent and build and administer. It was the doctor's job to keep them fit. Here then was creative work of the highest kind! The thought thrilled him!

Every boy of the right sort yearns to be of the greatest possible use in the world. Unselfishness is a natural instinct. Boys are not born selfish. They grow selfish because of association or training, and because they see others about them practicing selfishness. Grenfell's whole training had been toward unselfishness and usefulness. Here was a life calling that promised both unselfish and useful service and at the same time would gratify his desire to be a great deal out of doors, and he decided at once that he would study medicine and be a doctor.

His father was pleased with the decision. His course at Marlborough College was completed, and he immediately took special work preparatory to entering London Hospital and University.

In the University he did well. He passed his examinations creditably at the College of Physicians and Surgeons and at London University, and had time to take a most active part in the University athletics as a member of various 'Varsity teams. At one time or another he was secretary of the cricket, football and rowing clubs, and he took part in several famous championship games, and during one term that he was in residence at Oxford University he played on the University football team.

One evening in 1885 Grenfell, largely through curiosity, dropped into a tent where evangelistic meetings were in progress. The evangelists conducting the meeting happened to be the then famous D.L. Moody and Ira D. Sankey. Both Mr. Moody and Mr. Sankey were men of marvelous power and magnetism. Moody was big, wholesome and practical. He preached a religion of smiles and happiness and helpfulness. He lived what he preached. There was no humbug or hypocrisy in him. Sankey never had a peer as a leader of mass singing.

Moody was announcing a hymn when Grenfell entered. Sankey, in his illimitable style, struck up the music. In a moment the vast audience was singing as Grenfell had never heard an audience sing before. After the hymn Moody spoke. Grenfell told me once that that sermon changed his whole outlook upon life. He realized that he was a Christian in name only and not in fact. His religious life was a fraud.

There and then he determined that he must be either an out and out Christian or honestly renounce Christianity. With his home training and teachings he could not do the latter. He decided upon a Christian life. He would do nothing as a doctor that he could not do with a clear conscience as a Christian gentleman. This he also decided: a man's religion is something for him to be proud of and any one ashamed to acknowledge the faith of his fathers is a moral coward, and a moral coward is more contemptible than a physical coward. He also was convinced that a boy or man afraid or ashamed to acknowledge his religious belief could only be a mental weakling.

It was characteristic of Grenfell that whatever he attempted to do he did with courage and enthusiasm. He never was a slacker. The hospital to which he was attached was situated in the centre of the worst slums of London. It occurred to him that he might help the boys, and he secured a room, fitted it up as a gymnasium, and established a sort of boys' club, where on Sundays he held a Bible study class and where he gave the boys physical work on Saturdays. There was no Y.M.C.A. in England at that time where they could enjoy these privileges. In the beginning, there were young thugs who attempted to make trouble. He simply pitched them out, and in the end they were glad enough to return and behave themselves.

Grenfell and his brother, with one of their friends, spent the long holidays when college was closed cruising along the coast in an old fishing smack which they rented. In the course of his cruising, the thought came to him that it was hardly fair to the boys in the slums to run away from them and enjoy himself in the open while they sweltered in the streets, and he began at once to plan a camp for the boys.

This was long before the days of Boy Scouts and their camps. It was before the days of any boys' camps in England. It was an original idea with him that a summer camp would be a fine experience for his boys. At his own expense he established such a camp on the Welsh coast, and during every summer until he finished his studies in the University he took his boys out of the city and gave them a fine outing during a part of the summer holiday period. It was just at this time that the first boys' camp in America was founded by Chief Dudley as an experiment, now the famous Camp Dudley on Lake Champlain. We may therefore consider Grenfell as one of the pioneers in making popular the boys' camp idea, and every boy that has a good time in a summer camp should thank him.

But a time comes when all things must end, good as well as bad, and the time came when Grenfell received his degree and graduated a full-fledged doctor, and a good one, too, we may be sure. Now he was to face the world, and earn his own bread and butter. Pleasant holidays, and boys' camps were behind him. The big work of life, which every boy loves to tackle, was before him.

Then it was that Dr. Frederick Treves, later Sir Frederick, a famous surgeon under whom he had studied, made a suggestion that was to shape young Dr. Grenfell's destiny and make his name known wherever the English tongue is spoken.

The North Sea, big as it is, has no great depth. Geologists say that not long ago, as geologists calculate time, its bottom was dry land and connected the British Isles with the continent of Europe. Then it began to sink until the water swept in and covered it, and it is still sinking. The deepest point in the North Sea is not more than thirty fathoms, or one hundred eighty feet. There are areas where it is not over five fathoms deep, and the larger part of it is less than twenty fathoms.

Fish are attracted to the North Sea because it is shallow. Its bottom forms an extensive fishing "bank," we might say, though it is not, properly speaking, a bank at all, and here is found some of the finest fishing in the world.

From time immemorial fishing fleets have gone to the North Sea, and the North Sea fisheries is one of the important industries of Great Britain. Men are born to it and live their lives on the small fishing craft, and their sons follow them for generation after generation. It is a hazardous calling, and the men of the fleets are brave and hardy fellows.

The fishing fleets keep to the sea in winter as well as in summer, and it is a hard life indeed when decks and rigging are covered with ice, and fierce north winds blow the snow down, and the cold is bitter enough to freeze a man's very blood. Seas run high and rough, which is always the case in shallow waters, and great rollers sweep over the decks of the little craft, which of necessity have small draft and low freeboard.

The fishing fleets were like large villages on the sea. At the time of which we write, and it may be so to this day, fast vessels came daily to collect the fish they caught and to take the catch to market. Once in every three months a vessel was permitted to return to its home port for rest and necessary re-fitting, and then the men of her crew were allowed one day ashore for each week they had spent at sea. Now and again there came to the hospital sick or injured men returned from the fleet on these home-coming vessels.

When Grenfell passed his final examinations in 1886, and was admitted to the College of Physicians and Royal College of Surgeons of England, Sir Frederick Treves suggested that he visit the North Sea fishing fleets and lend his service to the fishermen for a time before entering upon private practice. The great surgeon, himself a lover of the sea and acquainted with Grenfell's inclinations toward an active outdoor life, was also aware that Grenfell was a good sailor.

"Don't go in summer," admonished Sir Frederick. "Go in winter when you can see the life of the men at its hardest and when they have the greatest need of a doctor. Anyhow you'll have some rugged days at sea if you go in winter."

He went on to explain that a few men had become interested in the fishermen of the fleets and had chartered a vessel to go among them to offer diversion in the hope of counteracting to some extent the attraction of the whiskey and rum traders whose vessels sold much liquor to the men and did a vast deal of harm. This vessel was open to the visits of the fishermen. Religious services were held aboard her on Sundays. There was no doctor in the fleet, and the skipper, who had been instructed in ordinary bandaging and in giving simple remedies for temporary relief, rendered first aid to the injured or sick until they could be sent away on some home-bound vessel and placed in a hospital for medical or surgical treatment. Thus a week or sometimes two weeks would elapse before the sufferer could be put under a doctor's care. Because of this long delay many men died who, with prompt attention, would doubtless have lived.

"The men who have fitted out this mission boat would like a young doctor to go with it," concluded Sir Frederick. "Go with them for a little while. You'll find plenty of high sea's adventure, and you'll like it."

In more than one way this suited Grenfell exactly. The opportunity for adventure that such a cruise offered appealed to him strongly, as it would appeal to any real live red-blooded man or boy. It also offered an opportunity to gain practical experience in his profession and at the same time render service to brave men who sadly needed it; and he could lend a hand in fighting the liquor evil among the seamen and thus share in helping to care for their moral, as well as their physical welfare. He had seen much of the evils of the liquor traffic during his student days in London, and he had acquired a wholesome hatred for it. In short, he saw an opportunity to help make the lives of these men happier. That is a high ideal for any one—to do something whenever possible to bring happiness into the lives of others.

This was too good an opportunity to let pass. It offered not only practice in his profession but service for others, and there would be the spice of adventure.

He applied without delay for the post, requesting to go on duty the following January. Whether Sir Frederick Treves said a word for him to the newly founded mission or not, I do not know, but at any rate Grenfell, to his great delight, was accepted, and it is probable the group of big hearted men who were sending the vessel to the fishermen were no less pleased to secure the services of a young doctor of his character.

At last the time came for departure. The mission ship was to sail from Yarmouth. Grenfell had been impatiently awaiting orders to begin his duties, when suddenly he received directions to join his vessel prepared to go to sea at once. Filled with enthusiasm and keen for the adventure he boarded the first train for Yarmouth.

It was a dark and rainy night when he arrived. Searching down among the wharves he found the mission ship tied to her moorings. She proved to be a rather diminutive schooner of the type and class used by the North Sea fishermen, and if the young doctor had pictured a large and commodious vessel he was disappointed. But Grenfell had been accustomed in his boyhood to knocking about with fishermen and now he was quite content with nothing better than fell to the lot of those he was to serve.

The little vessel was neat as wax below deck. The crew were big-hearted, brawny, good-natured fellows, and gave the Doctor a fine welcome. Of course his quarters were small and crowded, but he was bound on a mission and an adventure, and cramped quarters were no obstacle to his enthusiasm. Grenfell was not the sort of man to growl or complain at little inconveniences. He was thinking only of the duties he had assumed and the adventures that were before him.

At last he was on the seas, and his life work, though he did not know it then, had begun.

The skipper of the vessel was a bluff, hearty man of the old school of seamen. At the same time he was a sincere Christian devoted to his duties. At the beginning he made it plain that Grenfell was to have quite enough to do to keep him occupied, not only in his capacity as doctor, but in assisting to conduct afloat a work that in many respects resembled that of our present Young Men's Christian Association ashore.

The mission steamer was now to run across to Ostend, Belgium, where supplies were to be taken aboard before joining the fishing fleets.

It was bitterly cold, and while they lay at Ostend taking on cargo the harbor froze over, and they found themselves so firm and fast in the ice that it became necessary to engage a steamer to go around them to break them loose. At last, cargo loaded and ice smashed, they sailed away from Ostend and pointed their bow towards the great fleets, not again to see land for two full months, save Heligoland and Terschelling in the far distant offing.

The little vessel upon which Grenfell sailed was the first sent to the fisheries by the now famous Mission to Deep-Sea Fishermen; and the young Doctor on her deck, hardly yet realizing all that was expected of him, was destined to do no small part in the development of the splendid service that the Mission has since rendered the fishermen.

On the starboard side of the vessel's bow appeared in bold carved letters the words, "Heal the sick," on the port side of the bow, "Preach the Word."

"Preaching the Word" does not necessarily mean, and did not mean here, getting up into a pulpit for an hour or two and preaching orthodox sermons, sometimes as dry as dead husks, on Sundays. Sometimes just a smile and a cheery greeting is the best sermon in the world, and the finest sort of preaching. Just the example of living honestly and speaking truthfully and always lending a hand to the fellow who is in trouble or discouraged, is a fine sermon, for there is not a man or boy living whose life and actions do not have an influence for good or bad on some one else. We do not always realize this, but it is true.

Grenfell little dreamed of the future that this voyage was to open to him. He knew little or nothing at that time of Labrador or Newfoundland. He had never seen an Eskimo nor an American Indian, unless he had chanced to visit a "wild west" show. He had no other expectation than that he should make a single winter cruise with the mission schooner, and then return to England and settle in some promising locality to the practice of his profession, there to rise to success or fade into hum-drum obscurity, as Providence might will.

The fishermen of the North Sea fleet were as rough and ready as the old buccaneers. They were constantly risking their lives and they had not much regard for their own lives or the lives of others. With them life was cheap. Night and day they faced the dangers of the sea as they worked at the trawls, and when they were not sleeping or working there was no amusement for them. Then they were prone to resort to the grog ships, which hovered around them, and they too often drank a great deal more rum than was good for them. They were reared to a rough and cruel life, these fishermen. Hard punishments were dealt the men by the skippers. It was the way of the sea, as they knew it.

There were more than twenty thousand of these men in the North Sea fleets. Grenfell must have been overwhelmed with the thought that he was to be the only doctor within reach of that great number of men. "Heal the sick"—that was his job!

But he resolved to do much more than that! He was going to "Preach the Word" in smiles and cheering words, and was going to help the men in other ways than with his pill box and surgical bandages. As a doctor he realized how harmful liquor was to them, and he was going to fight the grog ships and do his best to put them out of business. In a word, he was not only going to doctor the men but he was going to help them to live straight, clean lives. He was going to play the game as he had played foot ball or pulled his oar with the winning crew at college. He was going to put into it the best that was in him!

That was the way Grenfell always did everything he undertook. When he had to pummel the "old boy" at Marlborough College he did it the best he knew how. Now he had a big job on his hands. He resolved, figuratively, to pummel the rum ships, and he was already planning and inventing ways that would make the men's lives easier. He went into the thing with his characteristic zeal, determined to make good. It is a mighty fine thing to make good. Any of us can make good if we go at things in the way Grenfell went at them—determined, whatever obstacles arise, not to fail. Grenfell never whined about luck going against him. He made his own luck. That is the mark of every successful and big man.

"There are the fleets," said the skipper one day, pointing out over the bow. "We'll make a round of the fleets, and you'll have a chance to get busy patching the men up."

And he was busy. There came as many patients every day as any young doctor could wish to treat. But that was what Grenfell wanted.

As the skipper suggested, the mission boat made a tour of the fleets, of which there were several, each fleet with its own name and colours and commanded by an Admiral. There were the Columbias, the Rashers, the Great Northerners and many others. It was finally with the Great Northerners that the mission boat took its station.

Grenfell visited among the vessels and made friends among the men, who were like big boys, rough and ready. They were always prepared to go into daring ventures. They never flinched at danger. Few of them had ever enjoyed the privilege of going to school, and none of the men and few of the skippers could write. They could read the compass just as men who cannot read can tell the time of day from the clock. But they had their method of dead reckoning and always appeared to know where they were, even though land had not been sighted for days.

Most of these men had been apprentised to the vessels as boys and had followed the sea all their lives. There were always many apprentised boys on the ships, and these worked without other pay than clothing, food and a little pocket money until they were twenty-one years of age. In many cases they received little consideration from the skippers and sometimes were treated with unnecessary roughness and even cruelty.

From the beginning Doctor Grenfell devoted himself not only to healing the sick, but also to bettering the condition of the fishermen. His skill was applied to the healing of their moral as well as their physical ills. Of necessity their life was a rough and rugged one, but there were opportunities to introduce some pleasure into it and to make it happier in many ways. Here was a strong human call that, from the beginning, Grenfell could not resist.

Using his own influence together with the influence of other good men, necessary funds were raised to meet the expenses of additional mission ships, and additional doctors and workers were sent out. Those selected were not only doctors, but men who were qualified by character and ability to guide the seamen to better and cleaner and more wholesome living. Queen Victoria became interested. The grog ships were finally driven from the sea. Laws were enacted to better conditions upon the fishing vessels that the lives of the fishermen might be easier and happier. In the course of time, as the result of Grenfell's tireless efforts, a marvelous change for the better took place.

Thus the years passed. Dr. Grenfell, who in the beginning had given his services to the Mission for a single winter, still remained. He felt it a duty that he could not desert. The work was hard, and it denied him the private practice and the home life to which he had looked forward so hopefully. He never had the time to drive fine horses about the country as he visited patients. But he had no regrets. He had chosen to accept and share the life of the fishermen on the high seas. It was no less a service to his country and to mankind than the service of the soldier fighting in the trenches. When he saw the need and heard the call he was willing enough to sacrifice personal ambitions that he might help others to become finer, better men, and live nobler happier lives.

Looking back over that period there is no doubt that Doctor Grenfell feels a thousand times repaid for any sacrifices he may have made. It is always that way. When we give up something for the other fellow, or do some fine thing to help him, our pleasure at the happiness we have given him makes us somehow forget ourselves and all we have given up.

And so came the year 1891. It was in that year that a member of the Mission Board returned from a visit to Canada and Newfoundland and reported to the Board great need of work among the Newfoundland fishermen similar to that that had been done by Grenfell in the North Sea.

The members of the Board were stirred by what they heard, and it was decided to send a ship across the Atlantic. It was necessary that the man in command be a doctor understanding the work to be done. It was also necessary that he should be a man of high executive and administrative ability, capable of organizing and carrying it on successfully. The man that has made good is the man always looked for to occupy such a post. Grenfell had made good in the North Sea. His work there indeed had been a brilliant success. He was the one man the Board thought of, and he was asked to go.

He accepted. Here was a new field of work and adventure offering ever greater possibilities than the old, and he never hesitated about it.

He began preparations for the new enterprise at once. The Albert, a little ketch-rigged vessel of ninety-seven tons register, was selected. Iron hatches were put into her, she was sheathed with greenhart to withstand the pressure of ice, and thoroughly refitted. Captain Trevize, a Cornishman, was engaged as skipper. Though Doctor Grenfell was himself a master mariner and thoroughly qualified as a navigator, he had never crossed the Atlantic, and in any case he was to be fully occupied with other duties. There was a crew of eight men including the mate, Skipper Joe White, a famous skipper of the North Sea fleets.

On June 15, 1892, the Albert was towed out of Great Yarmouth Harbor, and that day she spread her sails and set her course westward. The great work of Doctor Grenfell's life was now to begin. All the years of toil on the North Sea had been but an introduction to it and a preparation for it. His little vessel was to carry him to the bleak and desolate coast of Labrador and into the ice fields of the North. He was to meet new and strange people, and he was destined to experience many stirring adventures.

Heavy seas and head winds met the Albert, and she ran in at the Irish port of Cookhaven to await better weather. In a day or two she again spread her canvas, Fastnet Rock, at the south end of Ireland, the last land of the Old World to be seen, was lost to view, and in heavy weather she pointed her bow toward St. Johns, Newfoundland.

Twelve days later, in a thick fog, a huge iceberg loomed suddenly up before them, and the Albert barely missed a collision that might have ended the mission. It was the first iceberg that Doctor Grenfell had ever seen. Presently, and through the following years, they were to become as familiar to him as the trees of the forests.

Four hundred years had passed since Cabot on his voyage of discovery had, in his little caraval, passed over the same course that Grenfell now sailed in the Albert. Nineteen days after Fastnet Rock was lost to view, the shores of Newfoundland rose before them. That was fine sailing for the landfall was made almost exactly opposite St. Johns.

The harbor of St. Johns is like a great bowl. The entrance is a narrow passage between high, beetling cliffs rising on either side. From the sea the city is hidden by hills flanked by the cliffs, and a vessel must enter the narrow gateway and pass nearly through it before the city of St. Johns is seen rising from the water's edge upon sloping hill-sides on the opposite side of the harbor. It is one of the safest as well as most picturesque harbors in the world.

As the Albert approached the entrance Doctor Grenfell and the crew were astonished to see clouds of smoke rising from within and obscuring the sky. As they passed the cliffs waves of scorching air met them.

The city was in flames. Much of it was already in ashes. Stark, blackened chimneys rose where buildings had once stood. Flames were still shooting upward from those as yet but partly consumed. Some of the vessels anchored in the harbor were ablaze. Everything had been destroyed or was still burning. The Colonial public buildings, the fine churches, the great warehouses that had lined the wharves, even the wharves themselves, were smouldering ruins, and scarcely a private house remained. It was a scene of complete and terrible desolation. The fire had even extended to the forests beyond the city, and for weeks afterward continued to rage and carry destruction to quiet, scattered homes of the country.

The cause or origin of the fire no one knew. It had come as a devastating scourge. It had left the beautiful little city a mass of blackened, smoking ruins.

The Newfoundlanders are as fine and brave a people as ever lived. Deep trouble had come to them, but they met it with their characteristic heroism. No one was whining, or wringing his hands, or crying out against God. They were accepting it all as cheerfully as any people can ever accept so sweeping a calamity. Benjamin Franklin said, "God helps them that help themselves." That is as true of a city as it is of a person. That is what the St. Johns people were doing, and already, while the fire still burned, they were making plans to take care of themselves and rebuild their city.

Of course Doctor Grenfell could do little to help with his one small ship, but he did what he could. The officials and the people found time to welcome him and to tell him how glad they were that he was to go to Labrador to heal the sick of their fleets and make the lives of the fishermen and the natives of the northern coast happier and pleasanter.

A pilot was necessary to guide the Albert along the uncharted coast of Labrador. Captain Nicholas Fitzgerald was provided by the Newfoundland government to serve in this capacity. Doctor Grenfell invited Mr. Adolph Neilson, Superintendent of Fisheries for Newfoundland, to accompany them, and he accepted the invitation, that he might lend his aid to getting the work of the mission started. He proved a valuable addition to the party. Then the Albert sailed away to cruise her new field of service.

It will be interesting to turn to a map and see for ourselves the country to which Doctor Grenfell was going. We will find Labrador in the northeastern corner of the North American continent, just as Alaska is in the northwestern corner.

Like Alaska, Labrador is a great peninsula and is nearly, though not quite, so large as Alaska. Some maps will show only a narrow strip along the Atlantic east of the peninsula marked "Labrador." This is incorrect. The whole peninsula, bounded on the south by the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Straits of Belle Isle, the east by the Atlantic Ocean, the north by Hudson Straits, the west by Hudson Bay and James Bay and the Province of Quebec, is included in Labrador. The narrow strip on the east is under the jurisdiction of Newfoundland, while the remainder is owned by Quebec. Newfoundland is the oldest colony of Great Britain. It is not a part of Canada, but has a separate government.

The only people living in the interior of Labrador are a few wandering Indians who live by hunting. There are still large parts of the interior that have never been explored by white men, and of which we know little or no more than was known of America when Columbus discovered the then new world.

The people who live on the coast are white men, half-breeds and Eskimos. None of these ever go far inland, and they live by fishing, hunting, and trapping animals for the fur. Those on the south, as far east as Blanc Sablon, on the straits of Belle Isle, speak French. Eastward from Blanc Sablon and northward to a point a little north of Indian Harbor at the northern side of the entrance of Hamilton Inlet, English is spoken. The language on the remainder of the coast is Eskimo, and nearly all of the people are Eskimos. Once upon a time the Eskimos lived and hunted on the southern coast along the Straits of Belle Isle, but only white people and half-breeds are now found south of Hamilton Inlet.

The Labrador coast from Cape Charles in the south to Cape Chidley in the north is scoured as clean as the paving stones of a street. Naked, desolate, forbidding it lies in a somber mist. In part it is low and ragged but as we pass north it gradually rises into bare slopes and finally in the vicinity of Nachbak Bay high mountains, perpendicular and grey, stand out against the sky.

Behind the storm-scoured rocky islands lie the bays and tickles and runs and at the head of the bays the forest begins, reaching back over rolling hills into the mysterious and unknown regions beyond. There is not one beaten road in all the land. There is no sandy beach, no grassy bank, no green field. Nature has been kind to Labrador, however, in one respect. There are innumerable harbors snugly sheltered behind the islands and well out of reach of the rolling breakers and the wind. There is an old saying down on the Labrador that "from one peril there are two ways of escape to three sheltered places." The ice and fog are always perils but the skippers of the coast appear to hold them in disdain and plunge forward through storm and sea when any navigator on earth would expect to meet disaster. For the most part the coast is uncharted and the skippers, many of whom never saw an instrument of navigation in their life, or at least never owned one, sail by rhyme:

It is an evil coast, with hidden reefs and islands scattered like dust its whole length. "The man who sails the Labrador must know it all like his own back yard—not in sunny weather alone, but in the night, when the headlands are like black clouds ahead, and in the mist, when the noise of breakers tells him all that he may know of his whereabouts. A flash of white in the gray distance, a thud and swish from a hidden place: the one is his beacon, the other his fog-horn. It is thus, often, that the Doctor gets along."

Labrador has an Arctic climate in winter. The extreme cold of the country is caused by the Arctic current washing its shores. All winter the ocean is frozen as far as one can see. In June, when the ice breaks away, the great Newfoundland fishing fleet of little schooners sails north to remain until the end of September catching cod, for here are the finest cod fishing grounds in the world.

In 1892 there were nearly twenty-five thousand Newfoundlanders on this fleet. Doctor Grenfell's mission was to aid and assist these deep sea fishermen. In those days there was no doctor with the fleet and none on the whole coast, and any one taken seriously ill or badly injured usually died for lack of medical or surgical care. Of course, Grenfell was also to help the people who lived on the coast, that is, the native inhabitants, who needed him. This service he was giving free.

At this season there is more fog than sunshine in those northern latitudes. It settles in a dense pall over the sea, adding to the dangers of navigation. Now the fog was so thick that they could scarcely see the length of the vessel. On the fourth day out the fog lifted for a brief time, and Cape Bauld the northeasterly point of Newfoundland Island, showed his grim old head, as if to bid them goodbye and to wish them good luck "down on The Labrador." Then they were again swallowed by the fog and plunged into the rough seas where the Straits of Belle Isle meet the wide ocean.

No more land was seen, as they ploughed northward through the fog, until August 4th. This was a Thursday. Like the lifting of a curtain on a stage the fog, all at once, melted away, to reveal a scene of marvellous though rugged beauty. As though touched by a hand of magic, the atmosphere, for so many days dank and thick, suddenly became brilliantly clear and transparent, and the sun shone bright and warm.

Off the port bow lay The Labrador, the great silent peninsula of the north. Doctor Grenfell turned to it with a thrill. Here was the land he had come so far to see! Here he would find the people to whom he was to devote his life work!

There before him lay her scattered islands, her grim and rocky headlands and beetling cliffs, and beyond the islands, rolling away into illimitable blue distances her seared hills and the vast unknown region of her interior, whose mysterious secrets she had kept locked within her heart through all time. Back there, hidden from the world, were numberless lakes and rivers and mountains that no white man had ever seen.

The sea rose and fell in a lazy swell. Not far away a school of whales were playing, now and again spouting geysers of water high into the air. Shoals of caplin[A] gave silver flashes upon the surface of the sea where thousands of the little fish crowded one another to the surface of the water. Countless birds and sea fowl hovered before the face of the cliffs and above the placid sea.

A half hundred icebergs, children of age-old glaciers of the far North, were scattered over the green-blue waters. Some of them were of gigantic proportions and strange outlines. There were hills with lofty summits, marvellous castles, turreted and towered, and majestic cathedrals, their icy pinnacles and spires reaching high above the top-masts of the ship and their polished adamantine surfaces sparkling in the brilliant sunshine and scintillating fire and colour with the wondrous iridescent beauty of mammoth opals.

"There's Domino Run," said the pilot.

"Domino Run? What is that?"

"'Tis a fine deep run behind the islands," explained the pilot. "All the fleets of schooners cruisin' north and south go through Domino Run. There's a fine tidy harbor in there, and we'd be findin' some schooners anchored there now."

"We'll go in and see."

"I think 'twould be well and meet some of the fleet. There's liviyeres in there too. There's some liviyeres handy to most of the harbors on the coast."

"Liveyeres? What are liveyeres?"

"They're the folk that live on the coast all the time,—the whites and half-breeds. Newfoundlanders only come to fish in summer, but liveyeres stay the winter. The shop keepers we calls planters. They're set up by traders that has fishin' places. The liveyeres has their homes up the heads of bays in winter, and when the ice fastens over they trap fur. In the summer they come out to the islands to fish."

Doctor Grenfell had heard all this before, but now as he looked at the dreary desolation of the rocks it seemed almost incredible that children could be born and grow to manhood and womanhood and live their lives here, forever fighting for mere existence, and die at last without ever once knowing the comforts that we who live in kindlier warmer lands enjoy.

Presently a beautiful and splendid harbor opened before the Albert. Several schooners were lying at anchor within the harbor's shelter, and the strange new ship created a vast sensation as she hove to and dropped her anchor among them, and hoisted the blue flag of the Deep Sea Mission.

From masthead after masthead rose flags of greeting. It was a glorious welcome for any visitor to receive. A warmer or more cordial greeting could scarcely have been offered the Governor General himself. It was given with the fine hearty fervour and characteristic hospitality of the Newfoundland fishermen and seamen.

The Albert's anchor chains had scarce ceased to rattle before boats were pulling toward her from every vessel in the harbor. Ships enough sailed down the coast, to be sure, but if they were not fishing vessels they were traders looking to barter for fish, bearing sharp men who drove hard bargains with the fishermen, as we shall see. But here was a different vessel from any of them. Everybody knew that this was not a fisherman, and that she was not a trader. What was her business? What had she come for? What did her blue flag mean? These were questions to which everybody must needs find the answer for himself.

Great was their joy when it was learned that the Albert was a hospital ship with a real doctor aboard come to care for and heal their sick and injured, and that the doctor made no charge for his services or his medicine. This was a big point that went to their hearts, for there was scarce a man among them with any money in his pocket, and if Doctor Grenfell had charged them money they could not have called upon him to help them, for they could not have paid him. But here he was ready to serve them without money and without price. The richest, who were poor enough, and the poorest, could alike have his care and medicine. Here, indeed, was cause to wonder and rejoice.

Many of the fishermen took their families with them to live in little huts at the fishing places during the summer, and to help them prepare the fish for market. Forty or fifty men, women and children were packed, like figs in a box, on some of the schooners, with no other sleeping place than under the deck, on top of the cargo of provisions and salt in the hold, wherever they could find a place big enough to squeeze and stow themselves. Under such conditions there were ailing people enough on the schooners who needed a doctor's care.

The mail boat from St. Johns came once a fortnight, to be sure, and she had a doctor aboard her. But he could only see for a moment the more serious cases, and not all of them, hurriedly leave some medicine and go, and then he would not return to see them again in another two weeks. The mail boat had a schedule to make, and the time given her for the voyage between St. Johns and The Labrador was all too short, and she never reached the northernmost coast.

There were calls enough from the very beginning to keep Doctor Grenfell busy with the sick folk of the schooners. All that day the people came, and it was late that evening when the sick on the schooners had been cared for and the last of the visitors had departed.

Thus, on that first day in this new land, in the Harbor of Domino Run, Doctor Grenfell's life work among the deep sea fishermen of The Labrador began in earnest.

But even yet Doctor Grenfell's day's work was not to end. He was to witness a scene that would sicken his heart and excite his deepest pity. An experience awaited him that was to guide him to new and greater plans and to bigger things than he had yet dreamed of.

For a long while a rickety old rowboat had been lying off from the Albert. A bronzed and bearded man sat alone in the boat, eyeing the strange vessel as though afraid to approach nearer. He was thin and gaunt. The evening was chilly, but he was poorly clad, and his clothing was as ragged and as tattered as his old boat.

Finally, as though fearing to intrude, and not sure of his reception, he hailed the Albert.

[A] A small fish about the size of a smelt.

Grenfell, who had been standing at the rail for some time watching the decrepid old boat and its strange occupant, answered the hail cheerily.

"Be there a doctor aboard, sir?" asked the man.

"Yes," answered Grenfell. "I'm a doctor."

"Us were hearin' now they's a doctor on your vessel," said the man with satisfaction. "Be you a real doctor, sir?"

"Yes," assured the Doctor. "I hope I am."

"They's a man ashore that's wonderful bad off, but us hasn't no money," suggested the man, adding expectantly, "You couldn't come to doctor he now could you, sir?"

"Certainly I will," assured the Doctor. "What's the matter with the man? Do you know?"

"He have a distemper in his chest, sir, and a wonderful bad cough," explained the man.

"All right," said the Doctor. "I'll go at once. How far is it?"

"Right handy, sir," said the man with evident relief.

"Pull alongside and I'll be with you in a jiffy," and the Doctor hurried below for his medicine case.

The man was alongside waiting for him when he returned a few moments later, and he stepped into the rickety old boat. As the liveyere rowed away Grenfell may have thought of his own famous flat-boat that sank with him and his brother in the estuary below Parkgate years before when they were left to swim for it. But in his mental comparison it is probable that the flat-boat, even in her oldest and most decrepid days, would have passed for a rather fine and seaworthy craft in contrast to this rickety old rowboat. The boat kept afloat, however, and presently the liveyere pulled it alongside the gray rock that served for a landing. They stepped out and the guide led the way up the rocks to a lonely and miserable little sod hut. At the door he halted.

"Here we is, sir," he announced. "Step right in. They'll be wonderful glad to see you, sir."

Grenfell entered. Within was a room perhaps twelve by fourteen feet in size. A single small window of pieces of glass patched together was designed to admit light and at the same time to exclude God's good fresh air. The floor was of earth, partially paved with small round stones. Built against the walls were six berths, fashioned after the model of ship's berths, three lower and three upper ones. A broken old stove, with its pipe extending through the roof into a mud protection rising upon the peak outside in lieu of a chimney, made a smoky attempt to heat the place. The lower berths and floor served as seats. There was no furniture.

The walls of the hut were damp. The atmosphere was dank and unwholesome and heavy with the ill-smelling odor of stale seal oil and fish. The place was dirty and as unsanitary and unhealthful as any human habitation could well be.

Six ragged, half-starved little children huddled timidly into a corner upon the entrance of the visitor from the ship and gazed at the Doctor with wide-open frightened eyes. In one of the lower bunks lay the sick man coughing himself to death. At his side a gaunt woman, miserably and scantily clothed, was offering him water in a spoon.

It was evident to the trained eye of the Doctor that the man was fatally ill and could live but a short time. He was a hopeless consumptive, and a hasty examination revealed the fact that he was also suffering from a severe attack of pneumonia.

Doctor Grenfell's big sympathetic heart went out to the poor sufferer and his destitute family. What could he do? How could he help the man in such a place? He might remove him to one of the clean, white hospital cots on the Albert, but it would scarcely serve to make easier the impending death, and the exposure and effort of the transfer might even hasten it. Then, too, the wife and children would be denied the satisfaction of the last moments with the departing soul of the husband and father, for the Albert was to sail at once. The summer was short, and up and down the coast many others were in sore need of the Doctor's care, and delay might cost some of them their lives.

Grenfell sat silently for several minutes observing his patient and asking himself the question: "What can I do for this poor man?" If there had only been a doctor that the man could have called a few days earlier his life, at least might have been prolonged.

There was but one answer to the question. There was nothing to do but leave medicine and give advice and directions for the man's care, and to supply the ill-nourished family much-needed food and perhaps some warmer clothing.

If there were only a hospital on the coast where such cases could be taken and properly treated! If there were only some place where fatherless and orphaned children could be cared for! These were some of the thoughts that crowded upon Doctor Grenfell as he left the hut that evening and was rowed back to the Albert. And in the weeks that followed his mind was filled with plans, for never did the picture of the dying man and helpless little ones fade as he saw it that first day in Domino Run.

Another call to go ashore came that evening, and the Doctor answered it promptly. Again he was guided to a little mud hut, but this had an advantage over the other in that it was well ventilated. The one window which it boasted was an open hole in the side wall with no glass or other covering to exclude the fresh air. There was no stove, and an open fire on the earthen floor supplied warmth, while a large opening in the roof, for there was no chimney, offered an escape for the smoke, an offer of which the smoke did not freely take advantage.

On a wooden bench in a corner of the room a man sat doubled up with pain. Here too was a family consisting of the man's wife and several children.

"What's the trouble?" asked the Doctor.

"I'm wonderful bad with a distemper in my insides, sir," answered the man with a groan.

"Been ill long?"

"Aye, sir, for three weeks."

"We'll see what can be done."

"Thank you, sir."

"We'll patch you up and make you as well as ever in a little while," assured the Doctor after a thorough examination, for this proved to be a curable case.

"That'll be fine, sir."

Medicine was provided, with directions for taking, and, as the Doctor had promised, and as he later learned, the man soon recovered his health and returned to his fishing.

The Albert sailed north. Into every little harbor and settlement she dropped her anchor for a visit. She called at the trading posts of the old Hudson's Bay Company at Cartwright, Rigolet and Davis Inlet and the Moravian Missions among the Eskimos in the North. She was welcomed everywhere, and everywhere Doctor Grenfell found so many sick or injured people that the whole summer long he was kept constantly busy.

The waters of this coast were unknown to him. He knew nothing of their tides or reefs or currents. But with confidence in himself and a courage that was well-nigh reckless, he sought out the people of every little harbor that he might give them the help that he had come to give. If there was too great a hazard for the schooner, he used a whale-boat. Once this whale-boat was blown out to sea, once it was driven upon the rocks, once it capsized with all on board, and before the summer ended it became a complete wreck.

Nine hundred cases were treated, some trivial though perhaps painful enough maladies, others most serious or even hopeless. Here was a tooth to be extracted, there a limb to be amputated,—cases of all kinds and descriptions, with never a doctor to whom the people could turn for relief until Doctor Grenfell providentially appeared.

With all the work, the voyage was one of pleasure. Not only the pleasure of making others happier,—the greatest pleasure any one can know,—but it was a rattling fine adventure finding the way among islands that had never appeared on any map and were still unnamed. It was fine fun, too, cruising deep and magnificent fjords past lofty towering cliffs, and exploring new channels. And there were the Eskimos and their great wolfish dogs, and their primitive manner of living and dressing. It was all interesting and fascinating.

Never, however, since that August night in Domino Run, had the little mud hut, the dying man, the grief-stricken, miserable mother, and the neglected and starving little ones been out of Doctor Grenfell's thoughts, and often enough his big heart had ached for the stricken ones. He had never before witnessed such awful depths of poverty.

In other harbors that he had visited in his northern voyage similar heartrending cases had, to be sure, fallen under his attention. In one harbor he found a poor Eskimo both of whose hands had been blown off by the premature discharge of a gun. For days and days the man had endured indescribable agony. Nothing had been done for him, save to bathe the stubs of his shattered arms in cold water, until Doctor Grenfell appeared, for there was no surgeon to call upon to relieve the sufferer.

Everywhere there was a mute cry for help. The people were in need of doctors and hospitals. They were in need of hospital ships to cruise the coast and visit the sick of the harbors. They were in need of clothing that they were unable to purchase for themselves. They were in great need of some one to devise a way that would help them to free themselves from the ancient truck system that kept them forever hopelessly in debt to the traders.

The case of the man in the little mud hut at Domino Run, however, first suggested to Grenfell the need of these things and the thought that he might do something to bring them about. As a result of this visit, he made, during his northward cruise, a most thorough investigation of the requirements of the coast.

It was early October, and snow covered the ground, when the Albert, sailing south, again entered Domino Run and anchored in the harbor. Grenfell was put ashore and walked up the trail to the hut. The man had long since died and been laid to rest. The wife and children were still there. They had no provisions for the winter, and Grenfell, we may be sure, did all in his power to help them and make them more comfortable.

His plans had crystalized. He had determined upon the course he should take. He would go back to England and exert himself to the utmost to raise funds to build hospitals and to provide additional doctors and nurses for The Labrador. He would return to Labrador himself and give his life and strength and the best that was in him for the rest of his days in an attempt to make these people happier. Grenfell the athlete, the football player, the naturalist, and, above all, the doctor, was ready to answer the human call and to sacrifice his own comfort and ease and worldly possessions to the needs of these people. The man that will freely give his life to relieve the suffering of others represents the highest type of manhood. It is divine. It was characteristic of Grenfell.

And so it came about that the ragged man in the rickety boat who led Doctor Grenfell to the dying man in the mud hut was the indirect means of bringing hospitals and stores and many fine things to The Labrador that the coast had never known before. The ragged man in going for the doctor was simply doing a kindly act, a good turn for a needy neighbor. What magnificent results may come from one little act of kindness! This one laid the foundation for a work whose fame has encircled the world.

When Grenfell set out to do a thing he did it. He never in all his life said, "I will if I can." His motto has always been, "I can if I will." He had determined to plant hospitals on the Labrador coast and to send doctors and nurses there to help the people. When he determined to do a thing there was an end of it. It would be done. A great many people plan to do things, but when they find it is hard to carry out their plans, they give them up. They forget that anything that is worth having is hard to get. If diamonds were as easy to find as pebbles they would be worth no more than pebbles.

That was a hard job that Grenfell had set himself, and he knew it. When you have a hard job to do, the best way is to go at it just as soon as ever you can and work at it as hard as ever you can until it is done. That was Grenfell's way, and as soon as he reached St. Johns he began to start things moving. Someone else might have waited to return to England to make a formal report to the Deep Sea Missions Board, and await the Board's approval. Not so with Grenfell. He knew the Board would approve, and time was valuable.

Down on The Labrador winter begins in earnest in October. Already the fishing fleets had returned from Labrador when the Albert reached St. Johns, and the fishermen had brought with them the news of the Albert's visit to The Labrador and the wonderful things Doctor Grenfell had done in the course of his summer's cruise. Praise of his magnificent work was on everybody's lips. The newspapers, always hungry for startling news, had published articles about it. Doctor Grenfell was hailed as a benefactor. All creeds and classes welcomed and praised him,—fishermen, merchants, politicians. Even the dignified Board of Trade had recorded its praise.

It was November when Grenfell arrived in St. Johns. He immediately waited upon the government officials with the result that His Excellency, the Governor of the Colony, at once called a meeting in the Government House that Grenfell might present his plans for the future to the people. All the great men of the Colony were there. They listened with interest and were moved with enthusiasm. Some fine things were said, and then with the unanimous vote of the meeting resolutions were passed in commendation of Doctor Grenfell's summer's work and expressing the desire that it might continue and grow in accordance with Doctor Grenfell's plans. The resolutions finally pledged the "co-operation of all classes of this community." Here was an assurance that the whole of the fine old Colony was behind him, and it made Grenfell happy.

But this was not all. It is not the way of Newfoundland people to hold meetings and say fine things and pass high-sounding resolutions and then let the whole matter drop as though they felt they had done their duty. Doctor Grenfell would need something more than fine words and pats on the back if he were to put his plans through successfully, though the fine words helped, too, with their encouragement. He would need the help of men of responsibility who would work with him, and His Excellency, the Governor, recognizing this fact, appointed a committee composed of some of Newfoundland's best men for this purpose.

Then it was that Mr. W. Baine Grieve arose and began to speak. Mr. Grieve was a famous merchant of the Colony, and a member of the firm of Baine Johnston and Company, who owned a large trading station and stores at Battle Harbor, on an island near Cape Charles, at the southeastern extremity of Labrador. He was a man of importance in St. Johns and a leader in the Colony. As he spoke Grenfell suddenly realized that Mr. Grieve was presenting the Mission with a building at Battle Harbor which was to be fitted as a hospital and made ready for use the following summer.

What a thrill must have come to Grenfell at that moment! The whole Newfoundland government was behind him! His first hospital was already assured! We can easily imagine that he was fairly overwhelmed and dazed with the success that he had met so suddenly and unexpectedly.

But Grenfell was not a man to lose his head. This was only a beginning. He must have more hospitals than one. He must have doctors and nurses, medicines and hospital supplies, food and clothing, and a steam vessel that would take him quickly about to see the sick of the harbors. A great deal of money would be required, and when the Albert sailed out of St. John's Harbor and turned back to England he knew that he had assumed a stupendous job, and that the winter was not to be an idle one for him by any means.

It was December first when the Albert reached England. With the backing and assistance of the Mission Board, Doctor Grenfell and Captain Trevize of the Albert arranged a speaking tour for the purpose of exciting interest in the Labrador work. Men and women were moved by the tale of their experiences and the suffering and needs of the fishermen and liveres. Gifts were made and sufficient funds subscribed to purchase necessary supplies and hospital equipment, and a fine rowboat was donated to replace the Albert's whaleboat which had been smashed during the previous summer.

Then word came from St. Johns that the great shipping firm of Job Brothers, who owned a fisheries' station at Indian Harbor, had donated a hospital to the Newfoundland committee. This was to be erected at Indian Harbor, at the northern side of the entrance to Hamilton Inlet, two hundred miles north of Battle Harbor, and was to be ready for use during the summer. This was fine news. Not only were there large fishery stations at both Battle Harbor and Indian Harbor, but both were regular stopping places for the fishing schooners when going north and again on their homeward voyage. With two hospitals on the coast a splendid beginning for the work would be made.

But there was still one necessity lacking,—a little steamer in which Doctor Grenfell could visit the folk of the scattered harbors. At Chester on the River Dee and not far from his boyhood home at Parkgate Grenfell discovered a boat one day that was for sale and that he believed would answer his purpose. It was a sturdy little steam launch, forty-five feet over all. It was, however, ridiculously narrow, with a beam of only eight feet, and was sure to roll terribly in any sea and even in an ordinary swell.

But Grenfell was a good seaman, and he could make out in a boat that did a bit of tumbling. He was the sort of man to do a good job with a tool that did not suit him if he could not get just the sort of tool he wanted, and never find fault with it either. The necessary amount to purchase the launch was subscribed by a friend of the Mission. Grenfell bought it and was mightily pleased that this last need was filled. Later the little launch was christened the "Princess May."

Then the Albert was made ready for her second voyage to Labrador. The Mission Board appointed two young physicians to accompany Doctor Grenfell, Doctor Arthur O. Bobardt and Doctor Eliott Curwen, and two trained nurses, Miss Cecilia Williams and Miss Ada Cawardine, that there might be a doctor and a nurse for the hospital at Battle Harbor and a doctor and a nurse for the hospital at Indian Harbor. The launch Princess May was swung aboard the big Allan liner Corean and shipped to St. John's, and on June second Doctor Grenfell and his staff sailed from Queenstown on the Albert.

Grenfell was as fond of sports as ever he was in his boyhood and college days, and now, when the weather permitted, he played cricket with any on board who would play with him. The deck of so small a vessel as the Albert offers small space for a game of this sort, and one after another the cricket balls were lost overboard until but one remained. Then, one day, in the midst of a game in mid-ocean, that last ball unceremoniously followed the others into the sea.

Grenfell ran to the rail. He could see the ball rise on a wave astern.

"Tack back and pick me up!" he yelled to the helmsman, and to the astonishment and consternation of everyone, over the rail he dived in pursuit of the ball.

Grenfell could swim like a fish. He learned that in the River Dee and the estuary, when he was a boy, and he always kept himself in athletic training. But he had never before jumped into the middle of so large a swimming pool as the Atlantic ocean, with the nearest land a thousand miles away!

The steersman lost his head. He put over the helm, but failed to cut Grenfell off, and the Doctor presently found himself a long way from the ship struggling for life in the icy cold waters of the North Atlantic.

The young adventurer did not lose his head, and he did not waste his strength in desperate efforts to overtake the vessel. He calmly laid-to, kept his head above water, and waited for the helmsman to bring the ship around again.

A man less inured to hardships, or less physically fit, would have surrendered to the icy waters or to fatigue. Grenfell was as fit as ever a man could be.

In school and college he had made a record in athletic sports, and since leaving the university he had not permitted himself to get out of training. An athlete cannot keep in condition who indulges in cigarettes or liquor or otherwise dissipates, and Grenfell had lived clean and straight.

It was this that saved his life now. He knew he was fit and he had confidence in himself, and was unafraid. While he appreciated his peril, he never lost his nerve, and when finally he was rescued and found himself on deck he was little the worse for his experience, and with a change of dry clothing was ready to resume the interrupted game of cricket with the rescued ball.

With no further adventure than once coming to close quarters with an iceberg and escaping without serious damage, the Albert arrived in due time at St. John's, and Grenfell was at once occupied in preparation for his summer's work on The Labrador. Materials with which to construct the Indian Harbor hospital were shipped north by steamer. Supplies were taken aboard the Albert, and with Dr. Curwin and nurses Williams and Cawardine she sailed for Battle Harbor, where the building to be utilized as a hospital was already erected.

Then the launch Princess May, which had been landed from the Corean, was made ready for sea, and with an engineer and a cook as his crew and Dr. Bobardt as a companion, Dr. Grenfell as skipper put to sea in the tiny craft on July 7th.

There were many pessimistic prophets to see the Princess May off. From skipper to cook not a man aboard her was familiar with the coast, or could recognize a single landmark or headland either on the Newfoundland coast or on The Labrador.

They were going into rugged, fog-clogged seas. They might encounter an ice-pack, and the sea was always strewn with menacing icebergs. True, they had charts, but the charts were most incomplete, and no Newfoundlander sails by them.