Title: Ancient Art and Ritual

Author: Jane Ellen Harrison

Release date: November 18, 2005 [eBook #17087]

Most recently updated: December 12, 2020

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/17087

Credits: Produced by Thierry Alberto, Juliet Sutherland, Louise

Pryor and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

JANE ELLEN HARRISON

Geoffrey Cumberlege

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

LONDON NEW YORK TORONTO

First published in 1913, and reprinted in 1918 (revised), 1919, 1927, 1935 and 1948

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN

It may be well at the outset to say clearly what is the aim of the present volume. The title is Ancient Art and Ritual, but the reader will find in it no general summary or even outline of the facts of either ancient art or ancient ritual. These facts are easily accessible in handbooks. The point of my title and the real gist of my argument lie perhaps in the word “and”—that is, in the intimate connection which I have tried to show exists between ritual and art. This connection has, I believe, an important bearing on questions vital to-day, as, for example, the question of the place of art in our modern civilization, its relation to and its difference from religion and morality; in a word, on the whole enquiry as to what the nature of art is and how it can help or hinder spiritual life.

I have taken Greek drama as a typical instance, because in it we have the clear historical case of a great art, which arose out of a very primitive and almost world-wide ritual. The rise of the Indian drama, or the mediæval and from it the modern stage, would have told us the samevi tale and served the like purpose. But Greece is nearer to us to-day than either India or the Middle Ages.

Greece and the Greek drama remind me that I should like to offer my thanks to Professor Gilbert Murray, for help and criticism which has far outrun the limits of editorial duty.

J. E. H.

Newnham College,

Cambridge, June 1913.

The original text has been reprinted without change except for the correction of misprints. A few additions (enclosed in square brackets) have been made to the Bibliography.

1947

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I | ART AND RITUAL | 9 |

| II | PRIMITIVE RITUAL: PANTOMIMIC DANCES | 29 |

| III | PERIODIC CEREMONIES: THE SPRING FESTIVAL | 49 |

| IV | THE PRIMITIVE SPRING DANCE OR DITHYRAMB, IN GREECE | 75 |

| V | THE TRANSITION FROM RITUAL TO ART: THE DROMENON AND THE DRAMA | 119 |

| VI | GREEK SCULPTURE: THE PANATHENAIC FRIEZE AND THE APOLLO BELVEDERE | 170 |

| VII | RITUAL, ART AND LIFE | 204 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 253 | |

| INDEX | 255 |

The title of this book may strike the reader as strange and even dissonant. What have art and ritual to do together? The ritualist is, to the modern mind, a man concerned perhaps unduly with fixed forms and ceremonies, with carrying out the rigidly prescribed ordinances of a church or sect. The artist, on the other hand, we think of as free in thought and untrammelled by convention in practice; his tendency is towards licence. Art and ritual, it is quite true, have diverged to-day; but the title of this book is chosen advisedly. Its object is to show that these two divergent developments have a common root, and that neither can be understood without the other. It is at the outset one 10and the same impulse that sends a man to church and to the theatre.

Such a statement may sound to-day paradoxical, even irreverent. But to the Greek of the sixth, fifth, and even fourth century B.C., it would have been a simple truism. We shall see this best by following an Athenian to his theatre, on the day of the great Spring Festival of Dionysos.

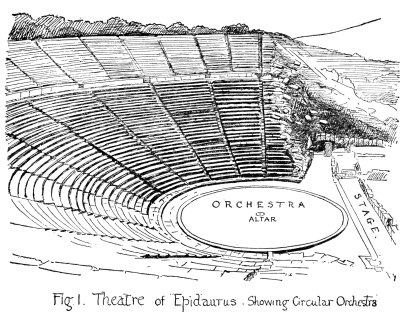

Passing through the entrance-gate to the theatre on the south side of the Acropolis, our Athenian citizen will find himself at once on holy ground. He is within a temenos or precinct, a place “cut off” from the common land and dedicated to a god. He will pass to the left (Fig. 2, p. 144) two temples standing near to each other, one of earlier, the other of later date, for a temple, once built, was so sacred that it would only be reluctantly destroyed. As he enters the actual theatre he will pay nothing for his seat; his attendance is an act of worship, and from the social point of view obligatory; the entrance fee is therefore paid for him by the State.

The theatre is open to all Athenian citizens, but the ordinary man will not venture to 11seat himself in the front row. In the front row, and that only, the seats have backs, and the central seat of this row is an armchair; the whole of the front row is permanently reserved, not for individual rich men who can afford to hire “boxes,” but for certain State officials, and these officials are all priests. On each seat the name of the owner is inscribed; the central seat is “of the priest of Dionysos Eleuthereus,” the god of the precinct. Near him is the seat “of the priest of Apollo the Laurel-Bearer,” and again “of the priest of Asklepios,” and “of the priest of Olympian Zeus,” and so on round the whole front semicircle. It is as though at His Majesty’s the front row of stalls was occupied by the whole bench of bishops, with the Archbishop of Canterbury enthroned in the central stall.

The theatre at Athens is not open night by night, nor even day by day. Dramatic performances take place only at certain high festivals of Dionysos in winter and spring. It is, again, as though the modern theatre was open only at the festivals of the Epiphany and of Easter. Our modern, at least our Protestant, custom is in direct contrast. We 12tend on great religious festivals rather to close than to open our theatres. Another point of contrast is in the time allotted to the performance. We give to the theatre our after-dinner hours, when work is done, or at best a couple of hours in the afternoon. The theatre is for us a recreation. The Greek theatre opened at sunrise, and the whole day was consecrated to high and strenuous religious attention. During the five or six days of the great Dionysia, the whole city was in a state of unwonted sanctity, under a taboo. To distrain a debtor was illegal; any personal assault, however trifling, was sacrilege.

Most impressive and convincing of all is the ceremony that took place on the eve of the performance. By torchlight, accompanied by a great procession, the image of the god Dionysos himself was brought to the theatre and placed in the orchestra. Moreover, he came not only in human but in animal form. Chosen young men of the Athenians in the flower of their youth—epheboi—escorted to the precinct a splendid bull. It was expressly ordained that the bull should be “worthy of the god”; he was, 13in fact, as we shall presently see, the primitive incarnation of the god. It is, again, as though in our modern theatre there stood, “sanctifying all things to our use and us to His service,” the human figure of the Saviour, and beside him the Paschal Lamb.

But now we come to a strange thing. A god presides over the theatre, to go to the theatre is an act of worship to the god Dionysos, and yet, when the play begins, three times out of four of Dionysos we hear nothing. We see, it may be, Agamemnon returning from Troy, Clytemnestra waiting to slay him, the vengeance of Orestes, the love of Phædra for Hippolytos, the hate of Medea and the slaying of her children: stories beautiful, tragic, morally instructive it may be, but scarcely, we feel, religious. The orthodox Greeks themselves sometimes complained that in the plays enacted before them there was “nothing to do with Dionysos.”

If drama be at the outset divine, with its roots in ritual, why does it issue in an art profoundly solemn, tragic, yet purely human? The actors wear ritual vestments like those of the celebrants at the Eleusinian mysteries.14 Why, then, do we find them, not executing a religious service or even a drama of gods and goddesses, but rather impersonating mere Homeric heroes and heroines? Greek drama, which seemed at first to give us our clue, to show us a real link between ritual and art, breaks down, betrays us, it would seem, just at the crucial moment, and leaves us with our problem on our hands.

Had we only Greek ritual and art we might well despair. The Greeks are a people of such swift constructive imagination that they almost always obscure any problem of origins. So fair and magical are their cloud-capp’d towers that they distract our minds from the task of digging for foundations. There is scarcely a problem in the origins of Greek mythology and religion that has been solved within the domain of Greek thinking only. Ritual with them was, in the case of drama, so swiftly and completely transmuted into art that, had we had Greek material only to hand, we might never have marked the transition. Happily, however, we are not confined within the Greek paradise. Wider fields are open to us; our subject is not only Greek, but ancient art and ritual. We can turn at 15once to the Egyptians, a people slower-witted than the Greeks, and watch their sluggish but more instructive operations. To one who is studying the development of the human mind the average or even stupid child is often more illuminating than the abnormally brilliant. Greece is often too near to us, too advanced, too modern, to be for comparative purposes instructive.

Of all Egyptian, perhaps of all ancient deities, no god has lived so long or had so wide and deep an influence as Osiris. He stands as the prototype of the great class of resurrection-gods who die that they may live again. His sufferings, his death, and his resurrection were enacted year by year in a great mystery-play at Abydos. In that mystery-play was set forth, first, what the Greeks call his agon, his contest with his enemy Set; then his pathos, his suffering, or downfall and defeat, his wounding, his death, and his burial; finally, his resurrection and “recognition,” his anagnorisis either as himself or as his only begotten son Horus. Now the meaning of this thrice-told tale we shall consider later: for the moment we are concerned 16only with the fact that it is set forth both in art and ritual.

At the festival of Osiris small images of the god were made of sand and vegetable earth, his cheek bones were painted green and his face yellow. The images were cast in a mould of pure gold, representing the god as a mummy. After sunset on the 24th day of the month Choiak, the effigy of Osiris was laid in a grave and the image of the previous year was removed. The intent of all this was made transparently clear by other rites. At the beginning of the festival there was a ceremony of ploughing and sowing. One end of the field was sown with barley, the other with spelt; another part with flax. While this was going on the chief priest recited the ritual of the “sowing of the fields.” Into the “garden” of the god, which seems to have been a large pot, were put sand and barley, then fresh living water from the inundation of the Nile was poured out of a golden vase over the “garden” and the barley was allowed to grow up. It was the symbol of the resurrection of the god after his burial, “for the growth of the garden is the growth of the divine substance.”

17The death and resurrection of the gods, and pari passu of the life and fruits of the earth, was thus set forth in ritual, but—and this is our immediate point—it was also set forth in definite, unmistakable art. In the great temple of Isis at Philæ there is a chamber dedicated to Osiris. Here is represented the dead Osiris. Out of his body spring ears of corn, and a priest waters the growing stalk from a pitcher. The inscription to the picture reads: This is the form of him whom one may not name, Osiris of the mysteries, who springs from the returning waters. It is but another presentation of the ritual of the month Choiak, in which effigies of the god made of earth and corn were buried. When these effigies were taken up it would be found that the corn had sprouted actually from the body of the god, and this sprouting of the grain would, as Dr. Frazer says, be “hailed as an omen, or rather as the cause of the growth of the crops.”1

Even more vividly is the resurrection set forth in the bas-reliefs that accompany the great Osiris inscription at Denderah. Here the god is represented at first as a mummy 18swathed and lying flat on his bier. Bit by bit he is seen raising himself up in a series of gymnastically impossible positions, till at last he rises from a bowl—perhaps his “garden”—all but erect, between the outspread wings of Isis, while before him a male figure holds the crux ansata, the “cross with a handle,” the Egyptian symbol of life. In ritual, the thing desired, i.e. the resurrection, is acted, in art it is represented.

No one will refuse to these bas-reliefs the title of art. In Egypt, then, we have clearly an instance—only one out of many—where art and ritual go hand in hand. Countless bas-reliefs that decorate Egyptian tombs and temples are but ritual practices translated into stone. This, as we shall later see, is an important step in our argument. Ancient art and ritual are not only closely connected, not only do they mutually explain and illustrate each other, but, as we shall presently find, they actually arise out of a common human impulse.

The god who died and rose again is not of course confined to Egypt; he is world-wide. When Ezekiel (viii. 14) “came to the gate of 19the Lord’s house which was toward the north” he beheld there the “women weeping for Tammuz.” This “abomination” the house of Judah had brought with them from Babylon. Tammuz is Dumuzi, “the true son,” or more fully, Dumuzi-absu, “true son of the waters.” He too, like Osiris, is a god of the life that springs from inundation and that dies down in the heat of the summer. In Milton’s procession of false gods,

Tammuz in Babylon was the young love of Ishtar. Each year he died and passed below the earth to the place of dust and death, “the land from which there is no returning, the house of darkness, where dust lies on door and bolt.” And the goddess went after him, and while she was below, life ceased in the earth, no flower blossomed and no child of animal or man was born.

We know Tammuz, “the true son,” best by one of his titles, Adonis, the Lord or King.20 The Rites of Adonis were celebrated at midsummer. That is certain and memorable; for, just as the Athenian fleet was setting sail on its ill-omened voyage to Syracuse, the streets of Athens were thronged with funeral processions, everywhere was seen the image of the dead god, and the air was full of the lamentations of weeping women. Thucydides does not so much as mention the coincidence, but Plutarch2 tells us those who took account of omens were full of concern for the fate of their countrymen. To start an expedition on the day of the funeral rites of Adonis, the Canaanitish “Lord,” was no luckier than to set sail on a Friday, the death-day of the “Lord” of Christendom.

The rites of Tammuz and of Adonis, celebrated in the summer, were rites of death rather than of resurrection. The emphasis is on the fading and dying down of vegetation rather than on its upspringing. The reason of this is simple and will soon become manifest. For the moment we have only to note that while in Egypt the rites of Osiris are represented as much by art as by ritual, in Babylon and Palestine in the feasts of Tammuz 21and Adonis it is ritual rather than art that obtains.

We have now to pass to another enquiry. We have seen that art and ritual, not only in Greece but in Egypt and Palestine, are closely linked. So closely, indeed, are they linked that we even begin to suspect they may have a common origin. We have now to ask, what is it that links art and ritual so closely together, what have they in common? Do they start from the same impulse, and if so why do they, as they develop, fall so widely asunder?

It will clear the air if we consider for a moment what we mean by art, and also in somewhat greater detail what we mean by ritual.

Art, Plato3 tells us in a famous passage of the Republic, is imitation; the artist imitates natural objects, which are themselves in his philosophy but copies of higher realities. All the artist can do is to make a copy of a copy, to hold up a mirror to Nature in which, as he turns it whither he will, “are reflected sun and heavens and earth and man,” any22thing and everything. Never did a statement so false, so wrong-headed, contain so much suggestion of truth—truth which, by the help of analysing ritual, we may perhaps be able to disentangle. But first its falsehood must be grasped, and this is the more important as Plato’s misconception in modified form lives on to-day. A painter not long ago thus defined his own art: “The art of painting is the art of imitating solid objects upon a flat surface by means of pigments.” A sorry life-work! Few people to-day, perhaps, regard art as the close and realistic copy of Nature; photography has at least scotched, if not slain, that error; but many people still regard art as a sort of improvement on or an “idealization” of Nature. It is the part of the artist, they think, to take suggestions and materials from Nature, and from these to build up, as it were, a revised version. It is, perhaps, only by studying those rudimentary forms of art that are closely akin to ritual that we come to see how utterly wrong-headed is this conception.

Take the representations of Osiris that we have just described—the mummy rising bit by bit from his bier. Can any one maintain 23that art is here a copy or imitation of reality? However “realistic” the painting, it represents a thing imagined not actual. There never was any such person as Osiris, and if there had been, he would certainly never, once mummified, have risen from his tomb. There is no question of fact, and the copy of fact, in the matter. Moreover, had there been, why should anyone desire to make a copy of natural fact? The whole “imitation” theory, to which, and to the element of truth it contains, we shall later have occasion to return, errs, in fact, through supplying no adequate motive for a widespread human energy. It is probably this lack of motive that has led other theorizers to adopt the view that art is idealization. Man with pardonable optimism desires, it is thought, to improve on Nature.

Modern science, confronted with a problem like that of the rise of art, no longer casts about to conjecture how art might have arisen, she examines how it actually did arise. Abundant material has now been collected from among savage peoples of an art so primitive that we hesitate to call it art at 24all, and it is in these inchoate efforts that we are able to track the secret motive springs that move the artist now as then.

Among the Huichol Indians,4 if the people fear a drought from the extreme heat of the sun, they take a clay disk, and on one side of it they paint the “face” of Father Sun, a circular space surrounded by rays of red and blue and yellow which are called his “arrows,” for the Huichol sun, like Phœbus Apollo, has arrows for rays. On the reverse side they will paint the progress of the sun through the four quarters of the sky. The journey is symbolized by a large cross-like figure with a central circle for midday. Round the edge are beehive-shaped mounds; these represent the hills of earth. The red and yellow dots that surround the hills are cornfields. The crosses on the hills are signs of wealth and money. On some of the disks birds and scorpions are painted, and on one are curving lines which mean rain. These disks are deposited on the altar of the god-house and left, and then all is well. The intention might 25be to us obscure, but a Huichol Indian would read it thus: “Father Sun with his broad shield (or ‘face’) and his arrows rises in the east, bringing money and wealth to the Huichols. His heat and the light from his rays make the corn to grow, but he is asked not to interfere with the clouds that are gathering on the hills.”

Now is this art or ritual? It is both and neither. We distinguish between a form of prayer and a work of art and count them in no danger of confusion; but the Huichol goes back to that earlier thing, a presentation. He utters, expresses his thought about the sun and his emotion about the sun and his relation to the sun, and if “prayer is the soul’s sincere desire” he has painted a prayer. It is not a little curious that the same notion comes out in the old Greek word for “prayer,” euchè. The Greek, when he wanted help in trouble from the “Saviours,” the Dioscuri, carved a picture of them, and, if he was a sailor, added a ship. Underneath he inscribed the word euchè. It was not to begin with a “vow” paid, it was a presentation of his strong inner desire, it was a sculptured prayer.

Ritual then involves imitation; but does 26not arise out of it. It desires to recreate an emotion, not to reproduce an object. A rite is, indeed, we shall later see (p. 42), a sort of stereotyped action, not really practical, but yet not wholly cut loose from practice, a reminiscence or an anticipation of actual practical doing; it is fitly, though not quite correctly, called by the Greeks a dromenon, “a thing done.”

At the bottom of art, as its motive power and its mainspring, lies, not the wish to copy Nature or even improve on her—the Huichol Indian does not vainly expend his energies on an effort so fruitless—but rather an impulse shared by art with ritual, the desire, that is, to utter, to give out a strongly felt emotion or desire by representing, by making or doing or enriching the object or act desired. The common source of the art and ritual of Osiris is the intense, world-wide desire that the life of Nature which seemed dead should live again. This common emotional factor it is that makes art and ritual in their beginnings well-nigh indistinguishable. Both, to begin with, copy an act, but not at first for the sake of the copy. Only when the emotion dies down and is 27forgotten does the copy become an end in itself, a mere mimicry.

It is this downward path, this sinking of making to mimicry, that makes us now-a-days think of ritual as a dull and formal thing. Because a rite has ceased to be believed in, it does not in the least follow that it will cease to be done. We have to reckon with all the huge forces of habit. The motor nerves, once set in one direction, given the slightest impulse tend always to repeat the same reaction. We mimic not only others but ourselves mechanically, even after all emotion proper to the act is dead; and then because mimicry has a certain ingenious charm, it becomes an end in itself for ritual, even for art.

It is not easy, as we saw, to classify the Huichol prayer-disks. As prayers they are ritual, as surfaces decorated they are specimens of primitive art. In the next chapter we shall have to consider a kind of ceremony very instructive for our point, but again not very easy to classify—the pantomimic dances which are, almost all over the world, so striking a feature in savage social and religious life. Are they to be classed as ritual or art?

28These pantomime dances lie, indeed, at the very heart and root of our whole subject, and it is of the first importance that before going further in our analysis of art and ritual, we should have some familiarity with their general character and gist, the more so as they are a class of ceremonies now practically extinct. We shall find in these dances the meeting-point between art and ritual, or rather we shall find in them the rude, inchoate material out of which both ritual and art, at least in one of its forms, developed. Moreover, we shall find in pantomimic dancing a ritual bridge, as it were, between actual life and those representations of life which we call art.

In our next chapter, therefore, we shall study the ritual dance in general, and try to understand its psychological origin; in the following chapter (III) we shall take a particular dance of special importance, the Spring Dance as practised among various primitive peoples. We shall then be prepared to approach the study of the Spring Dance among the Greeks, which developed into their drama, and thereby to, we hope, throw light on the relation between ritual and art.

1 Adonis, Attis, Osiris,2 p. 324.

2 Vit. Nik., 13.

3 Rep. X, 596-9.

4 C. H. Lumholtz, Symbolism of the Huichol Indians, in Mem. of the Am. Mus. of Nat. Hist., Vol. III, “Anthropology.” (1900.)

In books and hymns of bygone days, which dealt with the religion of “the heathen in his blindness,” he was pictured as a being of strange perversity, apt to bow down to “gods of wood and stone.” The question why he acted thus foolishly was never raised. It was just his “blindness”; the light of the gospel had not yet reached him. Now-a-days the savage has become material not only for conversion and hymn-writing but for scientific observation. We want to understand his psychology, i.e. how he behaves, not merely for his sake, that we may abruptly and despotically convert or reform him, but for our own sakes; partly, of course, for sheer love of knowing, but also,—since we realize that our own behaviour is based on instincts kindred to his,—in order that, by understanding his behaviour, we may understand, and it may be better, our own.

30Anthropologists who study the primitive peoples of to-day find that the worship of false gods, bowing “down to wood and stone,” bulks larger in the mind of the hymn-writer than in the mind of the savage. We look for temples to heathen idols; we find dancing-places and ritual dances. The savage is a man of action. Instead of asking a god to do what he wants done, he does it or tries to do it himself; instead of prayers he utters spells. In a word, he practises magic, and above all he is strenuously and frequently engaged in dancing magical dances. When a savage wants sun or wind or rain, he does not go to church and prostrate himself before a false god; he summons his tribe and dances a sun dance or a wind dance or a rain dance. When he would hunt and catch a bear, he does not pray to his god for strength to outwit and outmatch the bear, he rehearses his hunt in a bear dance.

Here, again, we have some modern prejudice and misunderstanding to overcome. Dancing is to us a light form of recreation practised by the quite young from sheer joie de vivre, and essentially inappropriate to the mature. But among the Tarahumares of Mexico the word31 nolávoa means both “to work” and “to dance.” An old man will reproach a young man saying, “Why do you not go and work?” (nolávoa). He means “Why do you not dance instead of looking on?” It is strange to us to learn that among savages, as a man passes from childhood to youth, from youth to mature manhood, so the number of his “dances” increase, and the number of these “dances” is the measure pari passu of his social importance. Finally, in extreme old age he falls out, he ceases to exist, because he cannot dance; his dance, and with it his social status, passes to another and a younger.

Magical dancing still goes on in Europe to-day. In Swabia and among the Transylvanian Saxons it is a common custom, says Dr. Frazer,5 for a man who has some hemp to leap high in the field in the belief that this will make the hemp grow tall. In many parts of Germany and Austria the peasant thinks he can make the flax grow tall by dancing or leaping high or by jumping backwards from a table; the higher the leap the taller will 32be the flax that year. There is happily little possible doubt as to the practical reason of this mimic dancing. When Macedonian farmers have done digging their fields they throw their spades up into the air and, catching them again, exclaim, “May the crop grow as high as the spade has gone.” In some parts of Eastern Russia the girls dance one by one in a large hoop at midnight on Shrove Tuesday. The hoop is decked with leaves, flowers and ribbons, and attached to it are a small bell and some flax. While dancing within the hoop each girl has to wave her arms vigorously and cry, “Flax, grow,” or words to that effect. When she has done she leaps out of the hoop or is lifted out of it by her partner.

Is this art? We shall unhesitatingly answer “No.” Is it ritual? With some hesitation we shall probably again answer “No.” It is, we think, not a rite, but merely a superstitious practice of ignorant men and women. But take another instance. Among the Omaha Indians of North America, when the corn is withering for want of rain, the members of the sacred Buffalo Society fill a large vessel with water and dance four times 33round it. One of them drinks some of the water and spirts it into the air, making a fine spray in imitation of mist or drizzling rain. Then he upsets the vessel, spilling the water on the ground; whereupon the dancers fall down and drink up the water, getting mud all over their faces. This saves the corn. Now probably any dispassionate person would describe such a ceremonial as “an interesting instance of primitive ritual.” The sole difference between the two types is that, in the one the practice is carried on privately, or at least unofficially, in the other it is done publicly by a collective authorized body, officially for the public good.

The distinction is one of high importance, but for the moment what concerns us is, to see the common factor in the two sets of acts, what is indeed their source and mainspring. In the case of the girl dancing in the hoop and leaping out of it there is no doubt. The words she says, “Flax, grow,” prove the point. She does what she wants done. Her intense desire finds utterance in an act. She obeys the simplest possible impulse. Let anyone watch an exciting game of tennis, or better still perhaps a game of billiards, he 34will find himself doing in sheer sympathy the thing he wants done, reaching out a tense arm where the billiard cue should go, raising an unoccupied leg to help the suspended ball over the net. Sympathetic magic is, modern psychology teaches us, in the main and at the outset, not the outcome of intellectual illusion, not even the exercise of a “mimetic instinct,” but simply, in its ultimate analysis, an utterance, a discharge of emotion and longing.

But though the utterance of emotion is the prime and moving, it is not the sole, factor. We may utter emotion in a prolonged howl, we may even utter it in a collective prolonged howl, yet we should scarcely call this ritual, still less art. It is true that a prolonged collective howl will probably, because it is collective, develop a rhythm, a regular recurrence, and hence probably issue in a kind of ritual music; but for the further stage of development into art another step is necessary. We must not only utter emotion, we must represent it, that is, we must in some way reproduce or imitate or express the thought which is causing us emotion. Art is not imitation, but art and also ritual frequently and legitimately contain an element of imita35tion. Plato was so far right. What exactly is imitated we shall see when we come to discuss the precise difference between art and ritual.

The Greek word for a rite as already noted is dromenon, “a thing done”—and the word is full of instruction. The Greek had realized that to perform a rite you must do something, that is, you must not only feel something but express it in action, or, to put it psychologically, you must not only receive an impulse, you must react to it. The word for rite, dromenon, “thing done,” arose, of course, not from any psychological analysis, but from the simple fact that rites among the primitive Greeks were things done, mimetic dances and the like. It is a fact of cardinal importance that their word for theatrical representation, drama, is own cousin to their word for rite, dromenon; drama also means “thing done.” Greek linguistic instinct pointed plainly to the fact that art and ritual are near relations. To this fact of crucial importance for our argument we shall return later. But from the outset it should be borne in mind that in these two Greek words, dromenon and36 drama, in their exact meaning, their relation and their distinction, we have the keynote and clue to our whole discussion.

For the moment we have to note that the Greek word for rite, dromenon, “thing done,” is not strictly adequate. It omits a factor of prime importance; it includes too much and not enough. All “things done” are not rites. You may shrink back from a blow; that is the expression of an emotion, that is a reaction to a stimulus, but that is not a rite. You may digest your dinner; that is a thing done, and a thing of high importance, but it is not a rite.

One element in the rite we have already observed, and that is, that it be done collectively, by a number of persons feeling the same emotion. A meal digested alone is certainly no rite; a meal eaten in common, under the influence of a common emotion, may, and often does, tend to become a rite.

Collectivity and emotional tension, two elements that tend to turn the simple reaction into a rite, are—specially among primitive peoples—closely associated, indeed scarcely separable. The individual among savages 37has but a thin and meagre personality; high emotional tension is to him only caused and maintained by a thing felt socially; it is what the tribe feels that is sacred, that is matter for ritual. He may make by himself excited movements, he may leap for joy, for fear; but unless these movements are made by the tribe together they will not become rhythmical; they will probably lack intensity, and certainly permanence. Intensity, then, and collectivity go together, and both are necessary for ritual, but both may be present without constituting art; we have not yet touched the dividing line between art and ritual. When and how does the dromenon, the rite done, pass over into the drama?

The genius of the Greek language felt, before it consciously knew, the difference. This feeling ahead for distinctions is characteristic of all languages, as has been well shown by Mr. Pearsall Smith6 in another manual of our series. It is an instinctive process arising independently of reason, though afterwards justified by it. What, then, is the distinction between art and ritual which the genius of the38 Greek language felt after, when it used the two words dromenon and drama for two different sorts of “things done”? To answer our question we must turn for a brief moment to psychology, the science of human behaviour.

We are accustomed for practical convenience to divide up our human nature into partitions—intellect, will, the emotions, the passions—with further subdivisions, e.g. of the intellect into reason, imagination, and the like. These partitions we are apt to arrange into a sort of order of merit or as it is called a hierarchy, with Reason as head and crown, and under her sway the emotions and passions. The result of establishing this hierarchy is that the impulsive side of our nature comes off badly, the passions and even the emotions lying under a certain ban. This popular psychology is really a convenient and perhaps indispensable mythology. Reason, the emotions, and the will have no more separate existences than Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva.

A more fruitful way of looking at our human constitution is to see it, not as a bundle of separate faculties, but as a sort of 39continuous cycle of activities. What really happens is, putting it very roughly, something of this sort. To each one of us the world is, or seems to be, eternally divided into two halves. On the one side is ourself, on the other all the rest of things. All our action, our behaviour, our life, is a relation between these two halves, and that behaviour seems to have three, not divisions, but stages. The outside world, the other half, the object if we like so to call it, acts upon us, gets at us through our senses. We hear or see or taste or feel something; to put it roughly, we perceive something, and as we perceive it, so, instantly, we feel about it, towards it, we have emotion. And, instantly again, that emotion becomes a motive-power, we re-act towards the object that got at us, we want to alter it or our relation to it. If we did not perceive we should not feel, if we did not feel we should not act. When we talk—as we almost must talk—of Reason, the Emotions, or the Passions and the Will leading to action, we think of the three stages or aspects of our behaviour as separable and even perhaps hostile; we want, perhaps, to purge the intellect from all infection of the emotions. But in reality, though at a given 40moment one or the other element, knowing, feeling, or acting, may be dominant in our consciousness, the rest are always immanent.

When we think of the three elements or stages, knowing, feeling, striving, as all being necessary factors in any complete bit of human behaviour, we no longer try to arrange them in a hierarchy with knowing or reason at the head. Knowing—that is, receiving and recognizing a stimulus from without—would seem to come first; we must be acted on before we can re-act; but priority confers no supremacy. We can look at it another way. Perceiving is the first rung on the ladder that leads to action, feeling is the second, action is the topmost rung, the primary goal, as it were, of all the climbing. For the purpose of our discussion this is perhaps the simplest way of looking at human behaviour.

Movement, then, action, is, as it were, the goal and the end of thought. Perception finds its natural outlet and completion in doing. But here comes in a curious consideration important for our purpose. In animals, in so far as they act by “instinct,” as we say, perception, knowing, is usually followed im41mediately and inevitably by doing, by such doing as is calculated to conserve the animal and his species; but in some of the higher animals, and especially in man, where the nervous system is more complex, perception is not instantly transformed into action; there is an interval for choice between several possible actions. Perception is pent up and becomes, helped by emotion, conscious representation. Now it is, psychologists tell us, just in this interval, this space between perception and reaction, this momentary halt, that all our mental life, our images, our ideas, our consciousness, and assuredly our religion and our art, is built up. If the cycle of knowing, feeling, acting, were instantly fulfilled, that is, if we were a mass of well-contrived instincts, we should hardly have dromena, and we should certainly never pass from dromena to drama. Art and religion, though perhaps not wholly ritual, spring from the incomplete cycle, from unsatisfied desire, from perception and emotion that have somehow not found immediate outlet in practical action. When we come later to establish the dividing line between art and ritual we shall find this fact to be cardinal.

42We have next to watch how out of representation repeated there grows up a kind of abstraction which helps the transition from ritual to art. When the men of a tribe return from a hunt, a journey, a battle, or any event that has caused them keen and pleasant emotion, they will often re-act their doings round the camp-fire at night to an attentive audience of women and young boys. The cause of this world-wide custom is no doubt in great part the desire to repeat a pleasant experience; the battle or the hunt will not be re-enacted unless it has been successful. Together with this must be reckoned a motive seldom absent from human endeavour, the desire for self-exhibition, self-enhancement. But in this re-enactment, we see at once, lies the germ of history and of commemorative ceremonial, and also, oddly enough, an impulse emotional in itself begets a process we think of as characteristically and exclusively intellectual, the process of abstraction. The savage begins with the particular battle that actually did happen; but, it is easy to see that if he re-enacts it again and again the particular battle or hunt will be forgotten, the representation 43cuts itself loose from the particular action from which it arose, and becomes generalized, as it were abstracted. Like children he plays not at a funeral, but at “funerals,” not at a battle, but at battles; and so arises the war-dance, or the death-dance, or the hunt-dance. This will serve to show how inextricably the elements of knowing and feeling are intertwined.

So, too, with the element of action. If we consider the occasions when a savage dances, it will soon appear that it is not only after a battle or a hunt that he dances in order to commemorate it, but before. Once the commemorative dance has got abstracted or generalized it becomes material for the magical dance, the dance pre-done. A tribe about to go to war will work itself up by a war dance; about to start out hunting they will catch their game in pantomime. Here clearly the main emphasis is on the practical, the active, doing-element in the cycle. The dance is, as it were, a sort of precipitated desire, a discharge of pent-up emotion into action.

In both these kinds of dances, the dance that commemorates by re-presenting and the dance that anticipates by pre-presenting, Plato would have seen the element of imitation, 44what the Greeks called mimesis, which we saw he believed to be the very source and essence of all art. In a sense he would have been right. The commemorative dance does especially re-present; it reproduces the past hunt or battle; but if we analyse a little more closely we see it is not for the sake of copying the actual battle itself, but for the emotion felt about the battle. This they desire to re-live. The emotional element is seen still more clearly in the dance fore-done for magical purposes. Success in war or in the hunt is keenly, intensely desired. The hunt or the battle cannot take place at the moment, so the cycle cannot complete itself. The desire cannot find utterance in the actual act; it grows and accumulates by inhibition, till at last the exasperated nerves and muscles can bear it no longer; it breaks out into mimetic anticipatory action. But, and this is the important point, the action is mimetic, not of what you see done by another; but of what you desire to do yourself. The habit of this mimesis of the thing desired, is set up, and ritual begins. Ritual, then, does imitate, but for an emotional, not an altogether practical, end.

45Plato never saw a savage war-dance or a hunt-dance or a rain-dance, and it is not likely that, if he had seen one, he would have allowed it to be art at all. But he must often have seen a class of performances very similar, to which unquestionably he would give the name of art. He must have seen plays like those of Aristophanes, with the chorus dressed up as Birds or Clouds or Frogs or Wasps, and he might undoubtedly have claimed such plays as evidence of the rightness of his definition. Here were men imitating birds and beasts, dressed in their skins and feathers, mimicking their gestures. For his own days his judgment would have been unquestionably right; but again, if we look at the beginning of things, we find an origin and an impulse much deeper, vaguer, and more emotional.

The beast dances found widespread over the savage world took their rise when men really believed, what St. Francis tried to preach: that beasts and birds and fishes were his “little brothers.” Or rather, perhaps, more strictly, he felt them to be his great brothers and his fathers, for the attitude of the Australian towards the kangaroo, the North American towards the grizzly bear, is one of 46affection tempered by deep religious awe. The beast dances look back to that early phase of civilization which survives in crystallized form in what we call totemism. “Totem” means tribe, but the tribe was of animals as well as men. In the Kangaroo tribe there were real leaping kangaroos as well as men-kangaroos. The men-kangaroos when they danced and leapt did it, not to imitate kangaroos—you cannot imitate yourself—but just for natural joy of heart because they were kangaroos; they belonged to the Kangaroo tribe, they bore the tribal marks and delighted to assert their tribal unity. What they felt was not mimesis but “participation,” unity, and community. Later, when man begins to distinguish between himself and his strange fellow-tribesmen, to realize that he is not a kangaroo like other kangaroos, he will try to revive his old faith, his old sense of participation and oneness, by conscious imitation. Thus though imitation is not the object of these dances, it grows up in and through them. It is the same with art. The origin of art is not mimesis, but mimesis springs up out of art, out of emotional expression, and constantly and closely neigh47bours it. Art and ritual are at the outset alike in this, that they do not seek to copy a fact, but to reproduce, to re-enact an emotion.

We shall see this more clearly if we examine for a moment this Greek word mimesis. We translate mīmēsis by “imitation,” and we do very wrongly. The word mimesis means the action or doing of a person called a mime. Now a mime was simply a person who dressed up and acted in a pantomime or primitive drama. He was roughly what we should call an actor, and it is significant that in the word actor we stress not imitating but acting, doing, just what the Greek stressed in his words dromenon and drama. The actor dresses up, puts on a mask, wears the skin of a beast or the feathers of a bird, not, as we have seen, to copy something or some one who is not himself, but to emphasize, enlarge, enhance, his own personality; he masquerades, he does not mimic.

The celebrants in the very primitive ritual of the Mountain-Mother in Thrace were, we know, called mimes. In the fragment of his lost play, Æschylus, after describing the din made by the “mountain gear” of the Mother, 48the maddening hum of the bombykes, a sort of spinning-top, the clash of the brazen cymbals and the twang of the strings, thus goes on:

“And bull-voices roar thereto from somewhere out of the unseen, fearful mimes, and from a drum an image, as it were, of thunder underground is borne on the air heavy with dread.”

Here we have undoubtedly some sort of “bull-roaring,” thunder-and wind-making ceremony, like those that go on in Australia to-day. The mimes are not mimicking thunder out of curiosity, they are making it and enacting and uttering it for magical purposes. When a sailor wants a wind he makes it, or, as he later says, he whistles for it; when a savage or a Greek wants thunder to bring rain he makes it, becomes it. But it is easy to see that as the belief in magic declines, what was once intense desire, issuing in the making of or the being of a thing, becomes mere copying of it; the mime, the maker, sinks to be in our modern sense the mimic; as faith declines, folly and futility set in; the earnest, zealous act sinks into a frivolous mimicry, a sort of child’s-play.

5 These instances are all taken from The Golden Bough,3 The Magic Art, I, 139 ff.

6 “The English Language,” Home University Library, p. 28.

We have seen in the last chapter that whatever interests primitive man, whatever makes him feel strongly, he tends to re-enact. Any one of his manifold occupations, hunting, fighting, later ploughing and sowing, provided it be of sufficient interest and importance, is material for a dromenon or rite. We have also seen that, weak as he is in individuality, it is not his private and personal emotions that tend to become ritual, but those that are public, felt and expressed officially, that is, by the whole tribe or community. It is further obvious that such dances, when they develop into actual rites, tend to be performed at fixed times. We have now to consider when and why. The element of fixity and regular repetition in rites cannot be too strongly emphasized. It is a factor of paramount importance, essential to the development from ritual to art, from dromenon to drama.

50The two great interests of primitive man are food and children. As Dr. Frazer has well said, if man the individual is to live he must have food; if his race is to persist he must have children. “To live and to cause to live, to eat food and to beget children, these were the primary wants of man in the past, and they will be the primary wants of men in the future so long as the world lasts.” Other things may be added to enrich and beautify human life, but, unless these wants are first satisfied, humanity itself must cease to exist. These two things, therefore, food and children, were what men chiefly sought to procure by the performance of magical rites for the regulation of the seasons. They are the very foundation-stones of that ritual from which art, if we are right, took its rise. From this need for food sprang seasonal, periodic festivals. The fact that festivals are seasonal, constantly recurrent, solidifies, makes permanent, and as already explained (p. 42), in a sense intellectualizes and abstracts the emotion that prompts them.

The seasons are indeed only of value to primitive man because they are related, as he swiftly and necessarily finds out, to his 51food supply. He has, it would seem, little sensitiveness to the æsthetic impulse of the beauty of a spring morning, to the pathos of autumn. What he realizes first and foremost is, that at certain times the animals, and still more the plants, which form his food, appear, at certain others they disappear. It is these times that become the central points, the focuses of his interest, and the dates of his religious festivals. These dates will vary, of course, in different countries and in different climates. It is, therefore, idle to attempt a study of the ritual of a people without knowing the facts of their climate and surroundings. In Egypt the food supply will depend on the rise and fall of the Nile, and on this rise and fall will depend the ritual and calendar of Osiris. And yet treatises on Egyptian religion are still to be found which begin by recounting the rites and mythology of Osiris, as though these were primary, and then end with a corollary to the effect that these rites and this calendar were “associated” with the worship of Osiris, or, even worse still, “instituted by” the religion of Osiris. The Nile regulates the food supply of Egypt, the monsoon that of certain South Pacific islands; 52the calendar of Egypt depends on the Nile, of the South Pacific islands on the monsoon.

In his recent Introduction to Mathematics7 Dr. Whitehead has pointed out how the “whole life of Nature is dominated by the existence of periodic events.” The rotation of the earth produces successive days; the path of the earth round the sun leads to the yearly recurrence of the seasons; the phases of the moon are recurrent, and though artificial light has made these phases pass almost unnoticed to-day, in climates where the skies are clear, human life was largely influenced by moonlight. Even our own bodily life, with its recurrent heart-beats and breathings, is essentially periodic.8 The presupposition of periodicity is indeed fundamental to our very conception of life, and but for periodicity the very means of measuring time as a quantity would be absent.

Periodicity is fundamental to certain departments of mathematics, that is evident; it is perhaps less evident that periodicity is a factor that has gone to the making of ritual, and hence, as we shall see, of art.53 And yet this is manifestly the case. All primitive calendars are ritual calendars, successions of feast-days, a patchwork of days of different quality and character recurring; pattern at least is based on periodicity. But there is another and perhaps more important way in which periodicity affects and in a sense causes ritual. We have seen already that out of the space between an impulse and a reaction there arises an idea or “presentation.” A “presentation” is, indeed, it would seem, in its final analysis, only a delayed, intensified desire—a desire of which the active satisfaction is blocked, and which runs over into a “presentation.” An image conceived “presented,” what we call an idea is, as it were, an act prefigured.

Ritual acts, then, which depend on the periodicity of the seasons are acts necessarily delayed. The thing delayed, expected, waited for, is more and more a source of value, more and more apt to precipitate into what we call an idea, which is in reality but the projected shadow of an unaccomplished action. More beautiful it may be, but comparatively bloodless, yet capable in its turn of acting as an initial motor impulse in the 54cycle of activity. It will later (p. 70) be seen that these periodic festivals are the stuff of which those faded, unaccomplished actions and desires which we call gods—Attis, Osiris, Dionysos—are made.

To primitive man, as we have seen, beast and bird and plant and himself were not sharply divided, and the periodicity of the seasons was for all. It will depend on man’s social and geographical conditions whether he notices periodicity most in plants or animals. If he is nomadic he will note the recurrent births of other animals and of human children, and will connect them with the lunar year. But it is at once evident that, at least in Mediterranean lands, and probably everywhere, it is the periodicity of plants and vegetation generally which depends on moisture, that is most striking. Plants die down in the heat of summer, trees shed their leaves in autumn, all Nature sleeps or dies in winter, and awakes in spring.

Sometimes it is the dying down that attracts most attention. This is very clear in the rites of Adonis, which are, though he rises again, essentially rites of lamentation. The details 55of the ritual show this clearly, and specially as already seen in the cult of Osiris. For the “gardens” of Adonis the women took baskets or pots filled with earth, and in them, as children sow cress now-a-days, they planted wheat, fennel, lettuce, and various kinds of flowers, which they watered and tended for eight days. In hot countries the seeds sprang up rapidly, but as the plants had no roots they withered quickly away. At the end of the eight days they were carried out with the images of the dead Adonis and thrown with them into the sea or into springs. The “gardens” of Adonis became the type of transient loveliness and swift decay.

“What waste would it be,” says Plutarch,9 “what inconceivable waste, for God to create man, had he not an immortal soul. He would be like the women who make little gardens, not less pleasant than the gardens of Adonis in earthen pots and pans; so would our souls blossom and flourish but for a day in a soft and tender body of flesh without any firm and solid root of life, and then be blasted and put out in a moment.”

56Celebrated at midsummer as they were, and as the “gardens” were thrown into water, it is probable that the rites of Adonis may have been, at least in part, a rain-charm. In the long summer droughts of Palestine and Babylonia the longing for rain must often have been intense enough to provoke expression, and we remember (p. 19) that the Sumerian Tammuz was originally Dumuzi-absu, “True Son of the Waters.” Water is the first need for vegetation. Gardens of Adonis are still in use in the Madras Presidency.10 At the marriage of a Brahman “seeds of five or nine sorts are mixed and sown in earthen pots which are made specially for the purpose, and are filled with earth. Bride and bridegroom water the seeds both morning and evening for four days; and on the fifth day the seedlings are thrown, like the real gardens of Adonis, into a tank or river.”

Seasonal festivals with one and the same intent—the promotion of fertility in plants, animals and man—may occur at almost any time of the year. At midsummer, as we have seen, we may have rain-charms; in autumn we shall have harvest festivals; in late autumn 57and early winter among pastoral peoples we shall have festivals, like that of Martinmas, for the blessing and purification of flocks and herds when they come in from their summer pasture. In midwinter there will be a Christmas festival to promote and protect the sun’s heat at the winter solstice. But in Southern Europe, to which we mainly owe our drama and our art, the festival most widely celebrated, and that of which we know most, is the Spring Festival, and to that we must turn. The spring is to the Greek of to-day the “ánoixis,” “the Opening,” and it was in spring and with rites of spring that both Greek and Roman originally began their year. It was this spring festival that gave to the Greek their god Dionysos and in part his drama.

In Cambridge on May Day two or three puzzled and weary little boys and girls are still to be sometimes seen dragging round a perambulator with a doll on it bedecked with ribbons and a flower or two. That is all that is left in most parts of England of the Queen of the May and Jack-in-the-Green, though here and there a maypole survives and is resuscitated by enthusiasts about folk-58dances. But in the days of “Good Queen Bess” merry England, it would seem, was lustier. The Puritan Stubbs, in his Anatomie of Abuses,11 thus describes the festival:

“They have twentie or fortie yoke of oxen, every oxe havyng a sweete nosegaie of flowers tyed on the tippe of his hornes, and these oxen draw home this Maiepoole (this stinckying idoll rather), which is covered all over with flowers and hearbes, bound round aboute with stringes from the top to the bottome, and sometyme painted with variable colours, with two or three hundred men, women, and children, following it with great devotion. And thus beyng reared up, with handkerchiefes and flagges streaming on the toppe, they strewe the ground about, binde greene boughs about it, set up summer haules, bowers, and arbours hard by it. And then fall they to banquet and feast, to leap and daunce aboute it, as the heathen people did at the dedication of their idolles, whereof this is a perfect patterne or rather the thyng itself.”

The stern old Puritan was right, the maypole was the perfect pattern of a heathen59 “idoll, or rather the thyng itself.” He would have exterminated it root and branch, but other and perhaps wiser divines took the maypole into the service of the Christian Church, and still12 on May Day in Saffron Walden the spring song is heard with its Christian moral—

The maypole was of course at first no pole cut down and dried. The gist of it was that it should be a “sprout, well budded out.” The object of carrying in the May was to bring the very spirit of life and greenery into the village. When this was forgotten, idleness or economy would prompt the villagers to use the same tree or branch year after year. In the villages of Upper Bavaria Dr. Frazer13 tells us the maypole is renewed once every three, four, or five years. It is a fir-tree fetched from the forest, and amid all the wreaths, flags, and inscriptions with which it is bedecked, an 60essential part is the bunch of dark green foliage left at the top, “as a memento that in it we have to do, not with a dead pole, but with a living tree from the greenwood.”

At the ritual of May Day not only was the fresh green bough or tree carried into the village, but with it came a girl or a boy, the Queen or King of the May. Sometimes the tree itself, as in Russia, is dressed up in woman’s clothes; more often a real man or maid, covered with flowers and greenery, walks with the tree or carries the bough. Thus in Thuringia,14 as soon as the trees begin to be green in spring, the children assemble on a Sunday and go out into the woods, where they choose one of their playmates to be Little Leaf Man. They break branches from the trees and twine them about the child, till only his shoes are left peeping out. Two of the other children lead him for fear he should stumble. They take him singing and dancing from house to house, asking for gifts of food, such as eggs, cream, sausages, cakes. Finally, they sprinkle the Leaf Man with water and feast on the food. Such a Leaf Man is our English Jack-in-the-Green, a chimney-sweeper 61who, as late as 1892, was seen by Dr. Rouse walking about at Cheltenham encased in a wooden framework covered with greenery.

The bringing in of the new leafage in the form of a tree or flowers is one, and perhaps the simplest, form of spring festival. It takes little notice of death and winter, uttering and emphasizing only the desire for the joy in life and spring. But in other and severer climates the emotion is fiercer and more complex; it takes the form of a struggle or contest, what the Greeks called an agon. Thus on May Day in the Isle of Man a Queen of the May was chosen, and with her twenty maids of honour, together with a troop of young men for escort. But there was not only a Queen of the May, but a Queen of Winter, a man dressed as a woman, loaded with warm clothes and wearing a woollen hood and fur tippet. Winter, too, had attendants like the Queen of the May. The two troops met and fought; and whichever Queen was taken prisoner had to pay the expenses of the feast.

In the Isle of Man the real gist of the ceremony is quite forgotten, it has become a mere play. But among the Esquimaux1562 there is still carried on a similar rite, and its magical intent is clearly understood. In autumn, when the storms begin and the long and dismal Arctic winter is at hand, the central Esquimaux divide themselves into two parties called the Ptarmigans and the Ducks. The ptarmigans are the people born in winter, the ducks those born in summer. They stretch out a long rope of sealskin. The ducks take hold of one end, the ptarmigans of the other, then comes a tug-of-war. If the ducks win there will be fine weather through the winter; if the ptarmigans, bad. This autumn festival might, of course, with equal magical intent be performed in the spring, but probably autumn is chosen because, with the dread of the Arctic ice and snow upon them, the fear of winter is stronger than the hope of spring.

The intense emotion towards the weather, which breaks out into these magical agones, or “contests,” is not very easy to realize. The weather to us now-a-days for the most part damps a day’s pleasuring or raises the price of fruit and vegetables. But our main supplies come to us from other lands and other weathers, and we find it hard to think 63ourselves back into the state when a bad harvest meant starvation. The intensely practical attitude of man towards the seasons, the way that many of these magical dramatic ceremonies rose straight out of the emotion towards the food-supply, would perhaps never have been fully realized but for the study of the food-producing ceremonies of the Central Australians.

The Central Australian spring is not the shift from winter to summer, from cold to heat, but from a long, arid, and barren season to a season short and often irregular in recurrence of torrential rain and sudden fertility. The dry steppes of Central Australia are the scene of a marvellous transformation. In the dry season all is hot and desolate, the ground has only patches of wiry scrub, with an occasional parched acacia tree, all is stones and sand; there is no sign of animal life save for the thousand ant-hills. Then suddenly the rainy season sets in. Torrents fill the rivers, and the sandy plain is a sheet of water. Almost as suddenly the rain ceases, the streams dry up, sucked in by the thirsty ground, and as though literally by magic a luxuriant vegetation bursts forth, the desert blossoms 64as a rose. Insects, lizards, frogs, birds, chirp, frisk and chatter. No plant or animal can live unless it live quickly. The struggle for existence is keen and short.

It seems as though the change came and life was born by magic, and the primitive Australian takes care that magic should not be wanting, and magic of the most instructive kind. As soon as the season of fertility approaches he begins his rites with the avowed object of making and multiplying the plants, and chiefly the animals, by which he lives; he paints the figure of the emu on the sand with vermilion drawn from his own blood; he puts on emu feathers and gazes about him vacantly in stupid fashion like an emu bird; he makes a structure of boughs like the chrysalis of a Witchetty grub—his favourite food, and drags his body through it in pantomime, gliding and shuffling to promote its birth. Here, difficult and intricate though the ceremonies are, and uncertain in meaning as many of the details must probably always remain, the main emotional gist is clear. It is not that the Australian wonders at and admires the miracle of his spring, the bursting of the flowers and the singing of birds; it is not 65that his heart goes out in gratitude to an All-Father who is the Giver of all good things; it is that, obedient to the push of life within him, his impulse is towards food. He must eat that he and his tribe may grow and multiply. It is this, his will to live, that he utters and represents.

The savage utters his will to live, his intense desire for food; but it should be noted, it is desire and will and longing, not certainty and satisfaction that he utters. In this respect it is interesting to note that his rites and ceremonies, when periodic, are of fairly long periods. Winter and summer are not the only natural periodic cycles; there is the cycle of day and night, and yet among primitive peoples but little ritual centres round day and night. The reason is simple. The cycle of day and night is so short, it recurs so frequently, that man naturally counted upon it and had no cause to be anxious. The emotional tension necessary to ritual was absent. A few peoples, e.g. the Egyptians, have practised daily incantations to bring back the sun. Probably they had at first felt a real tension of anxiety, and then—being 66a people hidebound by custom—had gone on from mere conservatism. Where the sun returns at a longer interval, and is even, as among the Esquimaux, hidden for the long space of six months, ritual inevitably arises. They play at cat’s-cradle to catch the ball of the sun lest it should sink and be lost for ever.

Round the moon, whose cycle is long, but not too long, ritual very early centred, but probably only when its supposed influence on vegetation was first surmised. The moon, as it were, practises magic herself; she waxes and wanes, and with her, man thinks, all the vegetable kingdom waxes and wanes too, all but the lawless onion. The moon, Plutarch16 tells us, is fertile in its light and contains moisture, it is kindly to the young of animals and to the new shoots of plants. Even Bacon17 held that observations of the moon with a view to planting and sowing and the grafting of trees were “not altogether frivolous.” It cannot too often be remembered that primitive man has but little, if any, interest in sun and moon and heavenly bodies for their inherent beauty or wonder; he cares for them, he holds them 67sacred, he performs rites in relation to them mainly when he notes that they bring the seasons, and he cares for the seasons mainly because they bring him food. A season is to him as a Hora was at first to the Greeks, the fruits of a season, what our farmers would call “a good year.”

The sun, then, had no ritual till it was seen that he led in the seasons; but long before that was known, it was seen that the seasons were annual, that they went round in a ring; and because that annual ring was long in revolving, great was man’s hope and fear in the winter, great his relief and joy in the spring. It was literally a matter of death and life, and it was as death and life that he sometimes represented it, as we have seen in the figures of Adonis and Osiris.

Adonis and Osiris have their modern parallels, who leave us in no doubt as to the meaning of their figures. Thus on the 1st of March in Thüringen a ceremony is performed called “Driving out the Death.” The young people make up a figure of straw, dress it in old clothes, carry it out and throw it into the river. Then they come back, tell 68the good news to the village, and are given eggs and food as a reward. In Bohemia the children carry out a straw puppet and burn it. While they are burning it they sing—

In other parts of Bohemia the song varies; it is not Summer that comes back but Life.

In both these cases it is interesting to note that though Death is dramatically carried out, the coming back of Life is only announced, not enacted.

Often, and it would seem quite naturally, the puppet representing Death or Winter is reviled and roughly handled, or pelted with stones, and treated in some way as a sort of scapegoat. But in not a few cases, and these are of special interest, it seems to be the seat of a sort of magical potency which can be and is transferred to the figure of Summer or Life, thus causing, as it were, a sort of Resur69rection. In Lusatia the women only carry out the Death. They are dressed in black themselves as mourners, but the puppet of straw which they dress up as the Death wears a white shirt. They carry it to the village boundary, followed by boys throwing stones, and there tear it to pieces. Then they cut down a tree and dress it in the white shirt of the Death and carry it home singing.

So at the Feast of the Ascension in Transylvania. After morning service the girls of the village dress up the Death; they tie a threshed-out sheaf of corn into a rough copy of a head and body, and stick a broomstick through the body for arms. Then they dress the figure up in the ordinary holiday clothes of a peasant girl—a red hood, silver brooches, and ribbons galore. They put the Death at an open window that all the people when they go to vespers may see it. Vespers over, two girls take the Death by the arms and walk in front; the rest follow. They sing an ordinary church hymn. Having wound through the village they go to another house, shut out the boys, strip the Death of its clothes, and throw the straw body out of the window to the boys, who fling it into a river. Then 70one of the girls is dressed in the Death’s discarded clothes, and the procession again winds through the village. The same hymn is sung. Thus it is clear that the girl is a sort of resuscitated Death. This resurrection aspect, this passing of the old into the new, will be seen to be of great ritual importance when we come to Dionysos and the Dithyramb.

These ceremonies of Death and Life are more complex than the simple carrying in of green boughs or even the dancing round maypoles. When we have these figures, these “impersonations,” we are getting away from the merely emotional dance, from the domain of simple psychological motor discharge to something that is very like rude art, at all events to personification. On this question of personification, in which so much of art and religion has its roots, it is all-important to be clear.

In discussions on such primitive rites as “Carrying out the Death,” “Bringing in Summer,” we are often told that the puppet of the girl is carried round, buried, burnt; brought back, because it “personifies the Spirit of Vegetation,” or it “embodies the71 Spirit of Summer.” The Spirit of Vegetation is “incarnate in the puppet.” We are led, by this way of speaking, to suppose that the savage or the villager first forms an idea or conception of a Spirit of Vegetation and then later “embodies” it. We naturally wonder that he should perform a mental act so high and difficult as abstraction.

A very little consideration shows that he performs at first no abstraction at all; abstraction is foreign to his mental habit. He begins with a vague excited dance to relieve his emotion. That dance has, probably almost from the first, a leader; the dancers choose an actual person, and he is the root and ground of personification. There is nothing mysterious about the process; the leader does not “embody” a previously conceived idea, rather he begets it. From his personality springs the personification. The abstract idea arises from the only thing it possibly can arise from, the concrete fact. Without perception there is no conception. We noted in speaking of dances (p. 43) how the dance got generalized; how from many commemorations of actual hunts and battles there arose the hunt dance and the war dance. So, from 72many actual living personal May Queens and Deaths, from many actual men and women decked with leaves, or trees dressed up as men and women, arises the Tree Spirit, the Vegetation Spirit, the Death.

At the back, then, of the fact of personification lies the fact that the emotion is felt collectively, the rite is performed by a band or chorus who dance together with a common leader. Round that leader the emotion centres. When there is an act of Carrying-out or Bringing-in he either is himself the puppet or he carries it. Emotion is of the whole band; drama—doing—tends to focus on the leader. This leader, this focus, is then remembered, thought of, imaged; from being perceived year by year, he is finally conceived; but his basis is always in actual fact of which he is but the reflection.

Had there been no periodic festivals, personification might long have halted. But it is easy to see that a recurrent perception helps to form a permanent abstract conception. The different actual recurrent May Kings and “Deaths,” because they recur, get a sort of permanent life of their own and become beings apart. In this way a concep73tion, a kind of daimon, or spirit, is fashioned, who dies and lives again in a perpetual cycle. The periodic festival begets a kind of not immortal, but perennial, god.

Yet the faculty of conception is but dim and feeble in the mind even of the peasant to-day; his function is to perceive the actual fact year by year, and to feel about it. Perhaps a simple instance best makes this clear. The Greek Church does not gladly suffer images in the round, though she delights in picture-images, eikons. But at her great spring festival of Easter she makes, in the remote villages, concession to a strong, perhaps imperative, popular need; she allows an image, an actual idol, of the dead Christ to be laid in the tomb that it may rise again. A traveller in Eubœa18 during Holy Week had been struck by the genuine grief shown at the Good Friday services. On Easter Eve there was the same general gloom and despondency, and he asked an old woman why it was. She answered: “Of course I am anxious; for if Christ does not rise to-morrow, we shall have no corn this year.”

74The old woman’s state of mind is fairly clear. Her emotion is the old emotion, not sorrow for the Christ the Son of Mary, but fear, imminent fear for the failure of food. The Christ again is not the historical Christ of Judæa, still less the incarnation of the Godhead proceeding from the Father; he is the actual figure fashioned by his village chorus and laid by the priests, the leaders of that chorus, in the local sepulchre.

So far, then, we have seen that the vague emotional dance tends to become a periodic rite, performed at regular intervals. The periodic rite may occur at any date of importance to the food-supply of the community, in summer, in winter, at the coming of the annual rains, or the regular rising of a river. Among Mediterranean peoples, both in ancient days and at the present time, the Spring Festival arrests attention. Having learnt the general characteristics of this Spring Festival, we have now to turn to one particular case, the Spring Festival of the Greeks. This is all-important to us because, as will be seen, from the ritual of this and kindred festivals arose, we believe, a great form of Art, the Greek drama.

7 Chapter XII: “Periodicity in Nature.”

8 Ibid.

9 De Ser. Num. 17.

10 Frazer, Adonis, Attis, and Osiris,3 p. 200.

11 Quoted by Dr. Frazer, The Golden Bough,2 p. 203.

12 E. K. Chambers, The Mediæval Stage, I, p. 169.

13 The Golden Bough,2 p. 205.

14 The Golden Bough,2 p. 213.

15 Resumed from Dr. Frazer, Golden Bough,2 II, p. 104.

16 De Is. et Os., p. 367.

17 De Aug. Scient., III, 4.

18 J. C. Lawson, Modern Greek Folk-lore and Ancient Religion, p. 573.

The tragedies of Æschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides were performed at Athens at a festival known as the Great Dionysia. This took place early in April, so that the time itself makes us suspect that its ceremonies were connected with the spring. But we have more certain evidence. Aristotle, in his treatise on the Art of Poetry, raises the question of the origin of the drama. He was not specially interested in primitive ritual; beast dances and spring mummeries might even have seemed to him mere savagery, the lowest form of “imitation;” but he divined that a structure so complex as Greek tragedy must have arisen out of a simpler form; he saw, or felt, in fact, that art had in some way risen out of ritual, and he has left us a memorable statement.

In describing the “Carrying-out of Summer” we saw that the element of real drama, real 76impersonation, began with the leaders of the band, with the Queen of the May, and with the “Death” or the “Winter.” Great is our delight when we find that for Greek drama Aristotle19 divined a like beginning. He says:

“Tragedy—as also Comedy—was at first mere improvisation—the one (tragedy) originated with the leaders of the Dithyramb.”

The further question faces us: What was the Dithyramb? We shall find to our joy that this obscure-sounding Dithyramb, though before Aristotle’s time it had taken literary form, was in origin a festival closely akin to those we have just been discussing. The Dithyramb was, to begin with, a spring ritual; and when Aristotle tells us tragedy arose out of the Dithyramb, he gives us, though perhaps half unconsciously, a clear instance of a splendid art that arose from the simplest of rites; he plants our theory of the connection of art with ritual firmly with its feet on historical ground.

When we use the word “dithyrambic” we certainly do not ordinarily think of spring.77 We say a style is “dithyrambic” when it is unmeasured, too ornate, impassioned, flowery. The Greeks themselves had forgotten that the word Dithyramb meant a leaping, inspired dance. But they had not forgotten on what occasion that dance was danced. Pindar wrote a Dithyramb for the Dionysiac festival at Athens, and his song is full of springtime and flowers. He bids all the gods come to Athens to dance flower-crowned.

“Look upon the dance, Olympians; send us the grace of Victory, ye gods who come to the heart of our city, where many feet are treading and incense steams: in sacred Athens come to the holy centre-stone. Take your portion of garlands pansy-twined, libations poured from the culling of spring....