Title: A Little Florida Lady

Author: Dorothy C. Paine

Release date: November 27, 2005 [eBook #17165]

Most recently updated: December 13, 2020

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Al Haines

E-text prepared by Al Haines

| I. | THE JOURNEY TO FLORIDA |

| II. | THE NEW HOME |

| III. | BETH'S FIRST FISHING LESSON |

| IV. | VISITING |

| V. | WALKING ON STILTS |

| VI. | HOUSE BUILDING |

| VII. | BETH'S NEW PLAYFELLOW |

| VIII. | LEARNING TO SWIM |

| IX. | THE LITTLE DRESSMAKER |

| X. | THE HORSE RACE |

| XI. | DON MEETS A SAD FATE |

| XII. | THE ARRIVAL OF DUKE |

| XIII. | ANXIOUS HOURS |

| XIV. | THE RESCUE |

New York was in the throes of a blizzard. The wind howled and shrieked, heralding the approach of March, the Wind King's month of the year. Mrs. Davenport stood at a second story window of a room of the Gilsey House, and looked down idly on the bleak thoroughfare. She was a young-looking woman for her thirty-five years, and had an extremely sweet face, denoting kindliness of heart.

The hall door opened, and Elizabeth Davenport entered, carrying in her arms a little ball of fluffy gray.

Elizabeth, or Beth, as she was more commonly called at the age of seven, might have been compared to a good fairy had she not been so plump. She almost always radiated sunshine, and her face was generally lighted with a smile, the outcome of a warm heart. Sometimes clouds slightly dimmed the sunshine, but they always proved to be summer clouds that quickly passed. Her face was now flushed, and her eyes sparkled.

Mrs. Davenport turned, and smiled in greeting, but, at the same time, brushed a tear from her eye.

"Why, mamma, dear, what's the matter?" cried Beth.

Mrs. Davenport's eyes filled, but she bravely smiled. "I'm a little unhappy over leaving all our friends, Beth. Florida seems very far away."

"I wouldn't be unhappy."

"How would you help it, dearie?"

"Why mamma," she answered triumphantly after a second's thought, "there are so many pleasant things to think about that I just never think of the unpleasant ones," and her face broke into a smile, so cheery that Mrs. Davenport's heart lightened.

"Mamma," she continued, "it's very easy for me to be happy. Every one is so good to me. The chambermaid just gave me this dear, dear kitty. Isn't it too cute for anything? I mean to take it to Florida with me."

"Why, Beth, that would never do."

Beth was about to demur, when a door into an adjoining room opened, and Mr. Davenport called:

"Mary, come here a minute, please."

Mrs. Davenport hastened to answer the call. She was hardly out of the room before Beth rushed to an open trunk. Impatiently, she began pulling things out. She burrowed almost to the very bottom. Lastly, she took out a skirt of her mother's, and wrapped something very carefully in it.

The door into the adjoining room creaked. Beth blushed scarlet, and dropped the bundle into the trunk. Then as no one came, she threw the other articles pell-mell on top of the bundle, and scampered guiltily to the other end of the room. Not an instant too soon to escape immediate detection, for Mrs. Davenport reëntered the room, followed by a girl of thirteen. This was Marian, Beth's sister. The two girls were totally unlike both in looks and in disposition. Marian was a tall blonde, and slight for her age. She had quiet, gentle ways.

"Mother, here's my red dress on the floor," she said, picking it up near the trunk.

"Beth, what have you been doing?"

Beth kept her blushing, telltale face turned from her mother, and did not answer. Without another word, Mrs. Davenport went to the trunk, and began smoothing things out.

"I declare, there's something alive in here," and she drew out a poor, half smothered kitten.

"I think you might let her go in the trunk," cried Beth, aggrieved.

"Child, it would kill the poor kitty. Marian, you take it back to the chambermaid." Marian left the room with it, and Beth began to pout, whereupon Mrs. Davenport said:

"Beth, you are so set upon having your own way, I hardly know what to do with you."

Immediately Beth's pouting gave place to a mischievous smile. "You'd better call in a policeman, and have me taken away."

Mrs. Davenport smiled too. "So my little girl remembers the policeman, does she? I was at my wits' end to know how to manage you when I thought of him. Even as a little bit of a thing, you would laugh instead of cry, if I punished you with a whipping."

"Well, I was afraid of the policeman, anyway. I thought you really meant it when you said I was a naughty child, and not your nice Beth, and that the policeman would take the naughty child away."

"It worked like magic," said Mrs. Davenport. "You stopped crying almost immediately, and held out towards me a red dress of which you were very proud, and cried, 'I'm your Beth. Don't you know my pretty red dress? Don't you see my curls?'" She sat down, having finished straightening out the trunk, and Beth crept up into her mother's lap.

"Beth, do you remember one night when you were ready for bed in your little canton-flannel night-drawers, that you lost your temper over some trifling matter? You danced up and down, yelling, 'I won't. I won't.' I could hardly keep from laughing. My young spitfire looked very funny capering around and around, her long curls rumpled about her determined, flushed face, and her feet not still an instant in her flapping night-drawers. Many and many a time you escaped punishment, Beth, because you were so very comical even in your naughtiness."

"I remember that night well," answered Beth. "You said, 'There, that bad girl has come back. Even though it's night, she'll have to go.'"

"And," interrupted Mrs. Davenport, "you threw yourself into my arms, crying, 'Mamma, whip me, but don't send me away.' I knew better than to whip you, but I punished you by not kissing you good-night."

"And I cried myself to sleep," put in Beth, snuggling more closely to her mother. "I thought I must be very naughty not to get my usual good-night kiss. I do try to be good, but it's very hard work sometimes. But I'll get the better of the bad girl, I'll leave her here in New York, so she won't bother you in Florida."——

Just then Mr. Davenport entered the room. He was a tall, dark man with a very kindly face.

"I think the snow is not deep enough to detain the trains," he said. "It's time for us to start. The porter is here to take the trunks."

"We'll be ready in a moment," answered his wife. "I fear we'll find it very disagreeable driving to the station."

And, in truth, outside the weather proved bitterly cold. The wind swept with blinding power up the now mostly deserted thoroughfare. The Davenports were glad of the shelter of the carriage which carried them swiftly along the icy pavement. Mrs. Davenport drew her furs around her, while the children snuggled together.

"I'm glad we're going, aren't you, Marian?" asked Beth, as they descended from the carriage at the station.

"I guess so," answered Marian doubtfully, remembering the friends she was leaving behind, perhaps forever.

Mr. Davenport already had their tickets, and the family immediately boarded a sleeper bound for Jacksonville.

Beth loved to travel, and soon was on speaking terms with every one on the car. She hesitated slightly about being friends with the porter. He made her think of the first colored person she had ever seen. She remembered even now how the man's rolling black eyes had frightened her, although it was the blackness of his skin that had impressed her the most. She believed that he had become dirty, the way she sometimes did, only in a greater degree.

"Mamma," she whispered, "I never get as black as that man, do I? Do you s'pose he ever washes himself?"

Mrs. Davenport explained that cleanliness had nothing to do with the man's blackness.

"Is he black inside?" Beth questioned in great awe.

"No. All people are alike at heart. Clean thinking makes even the black man white within, dear."

Beth had not seen another colored person from that time until this. Therefore, she was a little doubtful about making up with the porter. But he proved so very genial that before night arrived, he and "little missy," as he called Beth, were so very friendly that he considered her his special charge.

That night both children slept as peacefully as if they had been in their own home.

In the morning, Beth was wakened by Marian pulling up the shade. A stream of sunshine flooded their berth, blinding Beth for a second or two. Snow and clouds had been left far behind.

"It's almost like summer," cried Beth, hastening to dress.

After breakfast, the porter, whose name Beth learned was "Bob," took her out on the back platform while the engine was taking on water. To the left of the train were five colored children clustered around a stump.

"Bob, how many children have you?" asked Beth, and her eyes opened wide in astonishment.

"Law, honey," and Bob's grin widened, "I ain't got any chillun. I'se a bachelor."

Beth stamped her foot. She could not bear deceit. "Bob, it's very wrong to tell stories. These children must be yours; they're just like you."

He laughed so heartily at the idea, that Beth feared his mouth never would get into shape again. "Ha, ha, ha. Dem my chillun! Ha, ha, ha. Law, honey, dem ain't mine. Thank de Lord, I don't have to feed all dem hungry, sassy, little niggahs."

"Well, Bob, if they're not yours, whose are they?"

"Dem's jes' culled chillun."

A whistle sounded, and the train was soon under way again. Beth ran to her mother.

"Mamma, there were a lot of little Bobs outside, but he says they are not his children—that they're just colored children."

Mrs. Davenport had a hard time making her understand that Bob had told the truth. Beth sat very still for a while by a window. Suddenly, she cried out:

"What are those little specks of white? They look like little balls of snow, only they can't be. It's too warm, and then I never saw snow grow on bushes."

"That is cotton."

Although the bushes were not in their full glory—only having on them a little of last year's fruitage that was not picked—Beth thought a cotton field a very pretty sight.

The pine trees of Georgia prove monotonous to most people, except that their perpetual green is restful to the eye in the midst of white sand and dazzling sunshine. Beth, however, liked even the pines, being a lover of all trees. They seemed almost human to her. She believed that trees could speak if they would. She often talked to them, and fondled their rough old bark. Children can have worse companions than trees. They were a great comfort to Beth all through life.

On the way through Georgia, the train was delayed by a hot box. While it was being fixed, Bob took Beth for a walk, and she saw a moss-laden oak for the first time.

"Oh, Bob," she cried, "I never before saw a tree with hair."

His hearty laugh broke out anew. "Ha, ha, ha. I'll jes' pull some of dat hair for you, missy," and he raised his great, black hand to grab the curling, greenish, gray moss.

"Don't, Bob," and when he gave her no heed, she added, "I'm afraid it'll hurt the tree. I know it hurts me greatly when any one pulls my hair."

He laughed more than ever at her, until Beth grew ashamed, and meekly accepted the moss that he piled up in her little arms.

The hot box so delayed the train that Jacksonville was not reached until the middle of the night.

Bob took a sleeping child in his arms, and carried her out to the bus.

"Good-bye, little missy," he murmured, before handing her to her father.

Her arms tightened around his neck while her eyes opened for a second.

"Don't leave me, Bob. I love you."

Then she did not remember anything more until she wakened in a strange room the next morning.

At first, she could not think where she was. Then it came to her that she was in a hotel in Jacksonville. She sprang out of bed, and ran to a window. The room faced a park, and afforded Beth her first glimpse of tropical beauty. Strange trees glistened in the glorious sunshine. From pictures she had seen, Beth recognized the palms, and the orange trees. Below, on the piazza, the band was playing "Dixie." Delighted as Beth was, she did not linger long by the window, but dressed as fast as she could.

Mr. Davenport entered the room.

"Do you know what time it is? It's fully eleven, and I was up at six this morning."

"At six, papa? What have you been doing?"

"I went down town, and then I drove far out into the country."

"Oh, why didn't you waken me and let me go?"

"I had business on hand. Come along down to the dining-room. Your mother had some breakfast saved for you. I have a surprise for you."

"A surprise, papa? What is it?"

"It wouldn't be as great a surprise if I told you." This was all the satisfaction she received until after she had breakfasted.

"We're going for a drive," said Mr. Davenport as she came out of the dining-room.

"Is the drive the surprise, papa?"

"You'll know all in good time, Beth. You must have patience," he answered as he led the way out to the piazza.

"Get your hats, and bring Beth's with you," he said to Mrs. Davenport and Marian who were listening to the music.

"What do you think of that man and the rig?" asked Mr. Davenport of Beth, indicating a middle-aged negro who stood holding a bay mare hitched to a surrey.

Beth noted that the man looked good-natured. There were funny little curves on his face suggestive of laughter even when in repose. Jolly wrinkles lurked around his eyes. Beth saw two rows of pearly teeth though his mouth was partly hidden by a mustache and beard. His nose was large and flat. It looked like a dirty piece of putty thrown at haphazard on a black background. Beth, however, did not mind his homeliness.

"He's nice, and the horse is beautiful," she said.

"Then let's go down and talk to the man."

As Mr. Davenport and Beth walked to the side of the darky, he lifted his stovepipe hat that had been brushed until the silk was wearing away. He revealed thereby a shock of iron-gray wool. He made a sweeping bow.

"Massa, am dis de little missy dat yo' wuz tellin' 'bout? I'se powerful glad to meet yo', missy."

He was so very polite that even irrepressible Beth was a little awed. She hid halfway behind her father.

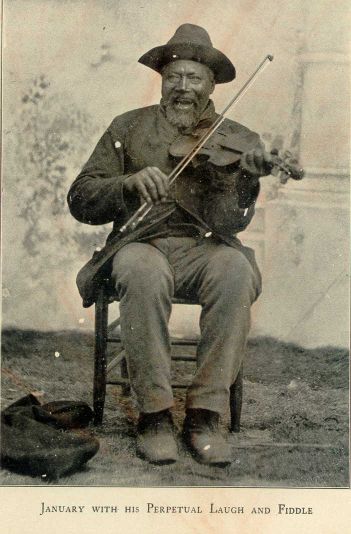

"This is January, Beth."

"What a very queer name," she whispered.

"It is queer, but you are in a strange land. For awhile you'll think you are in fairy-land. Everything will be so different. Do you want to stay with January while I go in to bring your mother?"

She nodded that she did. Mr. Davenport reëntered the hotel. Beth seated herself upon the curbstone, and looked at the bay horse behind which she was soon to have the bliss of driving. She thought it about as nice a horse as she had ever seen. Her curiosity overcame her momentary shyness. "Is it your horse, January?"

He smiled. "No, 'deed, missy, but I raised her from a colt, and she loves me like I wuz her massa. Why, she runs to me from de pasture when I jes' calls, while she's dat ornary wid odders, dey jes' can't cotch her. It takes old January to cotch dis horse, don't it, Dolly?"

The horse whinnied.

"Is Dolly her name?"

"Dat's what I calls her, honey. It ain't her real name. Her real name——"

"Oh, has she a nickname, too? She's like me then. My name isn't really Beth."

"'Deed?" he asked with polite interest.

"It's Elizabeth, but I'm called that only when I have tantrums."

"What am dem, missy?"

"Well," she blushingly stammered, "I sometimes forget to be good, and then I can't help having them—tantrums, you know. Just like the little girl with the curl who, when she was bad, was horrid. January, are you ever horrid?"

He looked self-conscious. "Law, missy, I nebber tinks I am, but Titus 'lows I am, but he don't know much nohow."

Dolly whinnied again, which recalled Beth's thoughts to the horse. "Who owns Dolly, January?"

"Law, missy, didn't I tole yo' dat she 'longs to yer paw now?"

Beth was so excited that she jumped to her feet, and began to clap her hands.

Her antics made her parents and Marian smile as they came from the hotel.

"Mamma, she's our horse. January said so. Dolly, do you like me?"

Dolly pricked up her ears as if she understood, and whinnied.

"She wants some sugar," declared Beth, believing that she understood horse language. She took a stale piece of candy out of her pocket, and gave it to Dolly. This attention sealed a never-ending friendship between the two.

"Dolly's the surprise, isn't she?" asked Beth, running up to her father. He smiled enigmatically, and that was all the answer she received.

Meantime, January, hat in hand, was bowing with Chesterfieldian politeness to Mrs. Davenport and Marian.

"All aboard," cried Mr. Davenport.

"Let me sit with January," begged Beth.

Marian, also, expressed a like wish. The two children, therefore, scrambled up in front beside the driver, while Mr. and Mrs. Davenport took the back seat.

January sat bolt upright. His dignity fitted the occasion. His driving, however, worried Beth.

She loved to go fast. She knew no fear of horses. She would have undertaken to drive the car of Phaeton, himself, had she been given the chance. She had little patience to poke along, and that was exactly what Dolly did when January drove.

"Can't she go faster?" she asked.

"She don't 'pear to go very fast, does she?" said January mildly. "Missy Beth, yo' jes' wait until her racing blood am up, and den she'll go so fast, yo'll wish she didn't go so fast."

Beth had her doubts of this, and even of Dolly's racing blood. Its truth, however, was to be proven by a later experience which will be told in due course.

"Has Dolly really racing blood?" asked Marian. Although January was sitting so straight that it seemed impossible for him to sit any straighter, he stiffened up at least an inch.

"Racing blood? Well, I jes' 'lows she has. Onct she wuz de fastest horse in dis State or any odder, I reckon. She could clean beat ebbery horse far and near. Many's de race I'se ridden her in, an' nebber onct lost. My ole massa wuz powerful proud of us. Now he's gone, an' Dolly an' me's gettin' old."

"How old are you, January?"

"Powerful ole, massa. I reckon I'm nigh on a hundred."

"That's impossible," interrupted Mrs. Davenport. "When were you born?"

He scratched his head to help his memory. "Well, de truf is, Miss Mary"—he had heard Mr. Davenport call her Mary, and so from the start he addressed her in Southern style—"I can't say 'xactly, but I know I'se powerful old. I wuz an ole man when de wah broke out. I must have been 'bout—well 'bout twenty then."

"The war was only about forty years ago, January," broke in Marian, "and that would make you sixty now."

"I reckon, I'm 'bout dat." He had no idea of his age. The longer the Davenports knew him, the more they realized the truth of this. Sometimes he would make himself out a centenarian, and then, by his own reckoning, he was not out of his teens.

"Get up, Dolly," he cried. She paid no more attention to this mild command than she would have to the buzzing of a fly—probably not so much.

"Papa, may I drive?" asked Marian in her quiet way. Receiving consent, she took the reins. Dolly soon noticed a difference in drivers. Presently she went so fast, that she satisfied even Beth as to speed.

"Look at the river," cried Beth. They were driving under great, over-arching trees. To the right of them, between the openings of the trees, the glorious St. Johns was to be seen gleaming under the brilliant tropical sun.

"That's a beautiful hammock yonder," said Mr. Davenport.

Beth could see no hammock. There was a wonderful, intricate growth of shrubs, trees, and vines which formed an almost impenetrable mass of green, but no hammock.

"Where is it?" she asked. "It seems a very queer place for a hammock."

Mr. Davenport laughed at her, and explained that such a mass of green is called a hammock in Florida, not hummock as in the North.

Very soon they were past the swamps. The banks of the river grew higher and nice houses were to be seen on either side of the road.

Dolly, of her own accord, turned in at the gate of an unusually beautiful place. There are no fine lawns in Florida. In this case, the lack of such green was made up by a waving mass of blooming cardinal phlox, behind which was an orange grove in full bearing. In the well-cultivated grounds there were many inviting drives through avenues of trees.

"What are we going in here for?" asked Beth.

"Do you think it a pretty place?" returned Mr. Davenport.

"I never saw a prettier place. It's grand."

"Guess who owns it."

"How should I know? I don't know any people in Florida."

"You know the Davenports. They are to live here. I bought the place this morning."

Beth could hardly believe her father. He had, indeed, greatly surprised her. That she was to be a little Florida lady henceforth, hardly seemed possible. She thought she must be a fairy-story princess, and that the fairies were vying with one another in showering upon her the good things of life.

"I'm so happy, I don't know what to say or do. Why, if a good fairy offered to grant me three wishes, I shouldn't know what to ask. I have everything," declared Beth.

"There aren't any fairies, and you know it. So what's the use of talking about them," interrupted practical Marian.

"Mamma says our thoughts are the real fairies," returned Beth, nothing daunted, and added, "papa has given me plenty of good ones to-day."

"I was in great luck to secure this place," said Mr. Davenport. "It had just been put on the market as Mr. Marlowe, the former owner, was called North by the death of his wife. The agent brought me out this morning, and I was so delighted with it that I would look no farther. I found the title all right, and so I signed the papers at once."

The house on the place just described was a rambling two-storied building with many porches—a typical vine-covered Southern cottage. It was picturesque from every side, and seemed to have no prosaic back. Marechal Niel roses, and honeysuckles, and some tropical vines, climbed over latticework almost to the roof. There were, also, many trees near the house, some of which were rare.

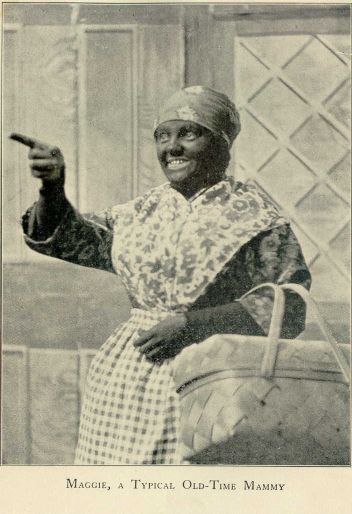

A colored woman bustled out of a side door, and looked down the road leading to the gate through which the Davenports' carriage had entered. Evidently, she was no common negro, but had served "quality" all her life—a typical old-time mammy. A red bandanna was drawn tightly over her short curly wool. Her dress was of flowered calico, and around her neck was a brilliant-hued shawl. A neat gingham apron covered her skirt. Her face broke into a smile, and she pointed to the palm-lined driveway.

"Yo' Titus—yo' Glory—Indianna—all yo' niggahs come hyere. De new massa and missus am comin'," she called.

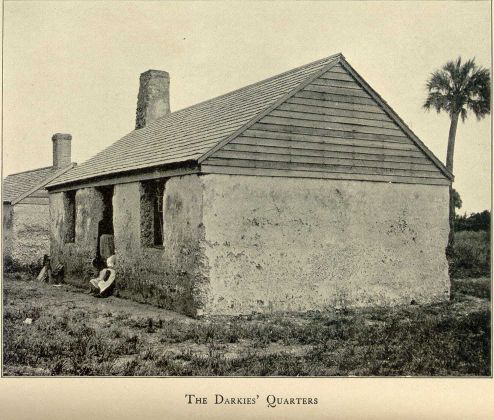

Out from the house, from the fields, from the quarters, they came trooping; old and young; weazened and pretty; black and yellow; all rolling their gleaming black eyes in the direction of the carriage which they saw come to a sudden standstill.

"What's de mattah?" they cried, and one young darky started down the road to see. He beheld January descend from the carriage, and walk to a persimmon tree and pluck some of the fruit.

The darky wondered what was to be done with the fruit that he knew was still green. His curiosity made him sneak up within earshot.

January returned to the carriage, and handed the fruit to Beth. The darky heard him say:

"I wouldn't eat dem, Missy Beth, if I wuz yo'. Dey am powerful green."

To her the little round fruit looked very tempting, especially the light yellow ones. Therefore she did not heed him. She selected one, but, instead of taking a dainty nibble, she put the whole fruit into her mouth, and bit down on it. Immediately, she set up a cry, and spit out the persimmon. "Ow-ow-ow, how it puckers!"

January chuckled, and, before driving on, he said: "I tole yo' so, Missy Beth."

Marian laughed until she was tired. "Beth, if you are drawn up inside the way your face is outside, it must be terrible."

"It is. It is." But she did not receive any sympathy. Even Mr. Davenport laughed at her. He had told her not to have January get them, but she had insisted on having her own way.

"Beth," he said, "I hope this may teach you a lesson. You must not taste things that you know nothing about."

Her mouth was still so drawn up that she did not care to do any more tasting—at least, not for the present. When she thought nobody was looking, she let the rest of the persimmons roll out of the carriage.

"What do they all do?" asked Beth as the carriage came to a standstill, and she noted the waiting negroes. As January helped her out, he chuckled, and swelled visibly with pride. "Dey all work for us, Missy Beth. She's de boss," he added in a low tone pointing to the colored woman with the bandanna. "Dat's Maggie; yo'd bettah make up with her."

The darkies courtesied. Their manners were of the old school. Beth ran up to Maggie.

"I hope you'll like me, Maggie, for I know I'll like you."

Maggie's face beamed. "Of cou'se, honey, I jes' kan't help likin' yo'. Yo'se de sweetest little missy I knows," and then she added: "Massa, I'se 'sidered yore proposition, an' me an' Titus 'cided to stay."

"All right, Maggie. You can show Mrs. Davenport and the children around the house."

Marian was willing to go with her mother, but Beth hung back.

"I don't care for the house. I want to see the front yard and river. May I go, papa?"

"If you'll come back in half an hour, you may go."

"All right, papa," and Beth was off like a flash around the corner of the house. She was impatient to see everything in that half hour. She felt that she needed a thousand eyes. The trees bewildered her. There were so many varieties she had never seen before—magnolias with their wonderful glossy foliage; bamboos with their tropical stalks covered with luxuriant green; pomegranates; live-oaks and water-oaks; the wild olive with its feathery white blossoms, and many others.

The moss on the oaks swayed back and forth, seeming to murmur, "Beth, these trees are the best of playfellows. Climb up here with us. We'll have great fun," but she would not heed them. There was too much to see.

All of a sudden, she stopped perfectly still. She thought there must be a fairy up in one of the trees with the most wonderful voice she had ever heard. Such singing, she thought, was too sweet to be human.

She looked up and beheld a bird of medium size, and of plain plumage. It cocked its little head to one side, and eyed the child as if it knew no fear. It sang on undisturbed.

"Beth," this is what the warbler said to her, "come up into this beautiful tree with us. Stay with us." The enticement of the bird, added to the fascination trees had for her, was almost too much for so little a girl to resist. However, she put her fingers into her ears, and ran on. But, she did not escape temptation thus. Countless beds of roses, of geraniums, and of many other flowers tempted her to linger, and gather the fragrant blossoms, but, still she did not succumb, for there was greater beauty ahead. She beheld a lovely avenue formed of orange trees and red and white oleanders trimmed to a perfect archway. The winter had been a mild one. Not only did luscious ripe oranges cling to the trees, but green fruit was forming, and there was, also, a wealth of fragrant blossoms. The oleanders, too, were coming into bloom.

Beth stopped for a moment to draw in some of the wonderful fragrance that filled the air. No perfume is more delightful than that of orange blossoms in their native grove. The fruit, too, looks more tempting on the trees. The glistening green leaves are just the right setting for the golden yellow balls. Beth wished to stop and eat some of the fruit, but again she proved firm. She ran on and on under the shade of the archway that extended a quarter of a mile at the very least. She ran so fast that her breath shortened and her cheeks flamed.

At the end of the avenue was an arch of stone covered with climbing Cherokees spread in wild confusion. Beth did not stop to gather any of the pure, fragrant blossoms, for right in front of the arch was a wharf leading out on the beautiful St. Johns. The river was from one to two miles wide at this point. It glistened and rippled under the brilliant sunshine. As Beth ran out on the wharf, she thought she had never seen a sight more charming.

The wharf extended far out into the river, and near the end of it, Beth came suddenly upon a boy with a loaf of bread in his hand. She stopped undecided, and looked at the boy. He was, perhaps, three or four years older than Beth. His hair was as light as hers was dark. His eyes were blue, and his naturally fair skin was tanned. He looked up at Beth for an instant, and frowned.

"What are you doing here, little un? I don't like girls to bother me. Go away."

If there was one thing above another that made Beth's temper rise, it was to be called "little one," and to be twitted upon being a girl. She felt like making up a face at this boy, but, instead, she assumed as much dignity as she could command.

"I won't go away. This is my place. What are you doing here?"

The boy laughed incredulously. "Your place, indeed. The Marlowes own this place, and they are away. Good-bye."

This was too much for her. She stamped her foot in rage. "I won't go. My papa bought this place to-day."

He looked a little interested. "Indeed? What's your name?"

"Elizabeth Davenport;" she said 'Elizabeth' to be dignified, "and really my father owns the place."

"If what you say is so, I'd better go," he said somewhat sheepishly.

She relented. "Oh, I'll let you stay."

"I'm not sure I want to. I don't like girls. They're 'fraid-cats."

"I'm no 'fraid-cat," and her eyes snapped.

"How can you prove it, Elizabeth?"

"Don't call me that. I hate to be called Elizabeth."

"But you told me that was your name."

"Everybody calls me Beth. If you're nice, you may call me Beth."

"All right. How are you going to prove you're no 'fraid-cat, Eli—Beth?"

She pondered a moment. "'Fraid-cats cry when they're hurt, don't they?"

"Of course. So do girls."

"I don't cry when I'm hurt," and she looked triumphant as if that settled the matter. "Once when I was a little bit of a girl——"

"You're pretty small now."

"I'm a big girl, and you shouldn't interrupt. Well, once Marian——"

"Who's she?"

"She's my sister. Well, I wanted to light the gas, but Marian said I was too small, but I'd not listen. I jumped up on a rocker to light the gas. The chair rocked and, I fell against the windowsill. Marian screamed, 'Beth's killed. She's covered with blood!'"

"Were you really?"

"Yes." Beth felt she was arguing her case well. "Mamma thought I just had the nose bleed, but what do you s'pose? I had two mouths."

The boy's eyes grew big. "Two mouths—how jolly. How did it happen?"

"The window-sill had cut me right across here," she pointed to the space just below her nose. "The doctor took five stitches, and when it healed, took them out again. It hurt very much, but I didn't cry a bit."

"Didn't it leave a scar on your face?"

She threw back her head.

"There, do you see that little white line under my nose? You can hardly see it now."

The boy examined the spot critically. Then he changed the subject. "Where did you live before you came here?"

"New York."

"Did you like it there?"

"No, it was horrid. I hated to be dressed up and sent for a walk."

He looked incredulous. "Most girls like to be dressed up."

"I don't."

"Don't you like to be told you are a pretty little girl with nice clothes?"

"No, I don't."

He sniffed disdainfully. "Oh, go long. I don't believe that."

Beth grew very much in earnest, and thought of another little illustration.

"Truth 'pon honor. One day a strange lady in a store put her hand on my head, and said: 'What a pretty little girl.' It made me mad, so that I just grunted and made up a face at her. My mamma said, 'Why, Beth, that is very naughty.' I said, 'Well, mamma, what business is it of hers whether I am pretty or not? It isn't my fault if I am pretty and people shouldn't bother me.'"

The boy laughed. "I believe I rather like you, Beth, but I only have your word for it that you are not like other girls. I have a big mind to try you. Shall I?"

She was a little afraid to consent, but she was ashamed to show it. So she delayed matters by asking "How?"

The boy drew down his face until it was very long, and when he spoke it was in an awe-inspiring whisper.

"Swear never to tell what I tell you. Repeat after me, 'Harvey Baker——'"

"Is that your name?"

"Yes—don't interrupt me. 'Harvey Baker, if I tell what you show me, I hope I may be forever doomed and tortured.'"

Beth looked shocked. "I won't say that."

"'Fraid-cat. 'Fraid-cat."

Again she stamped her foot. "I won't be called that. It's not true. I will promise not to tell. Can't you believe me?"

The boy considered. "Girls are hardly ever to be trusted, but I'll try you. In this river there is a great, big, black animal that hates fraid-cats as much as I do. He eats them up. Why, he has such fierce jaws and sharp teeth that he could gobble up a little girl like you in one mouthful."

Beth felt that her hair must be standing up on end. She would have run away, had not pride detained her—and then the recital rather fascinated her. Harvey continued, relishing the effect of his story:

"Now I have only to whistle to have the awful animal appear. His head will slowly rise above the water. His jaws will open. His teeth will gleam. If any little girl cries, he will snap at her, and it will be good-bye girl. Now, if you are not a fraid-cat you'll say, 'Harvey Baker, whistle.'"

She wanted to run more than ever, but instead she repeated slowly:

"Harvey Baker, whistle."

The boy pursed up his lips, but he then made an impressive pause, and finally pointed his finger at Beth.

"Elizabeth Davenport, remember. If you give the least little bit of a cry, you die. But, if you keep perfectly still, and never tell what you see, I am your friend for life." Thereupon he whistled very shrilly.

Beth's eyes were glued upon the water. Every little ripple seemed to her excited imagination an awful head rising to gobble her up. However, nothing appeared. Beth gave a sigh of relief.

"Harvey Baker, you were fooling."

He motioned to her to be silent. Again, he whistled. Still no horrible head appeared. Beth was now fully convinced that he was only making believe, but still she could not take her eyes off the water.

For the third time, Harvey whistled. Suddenly the waters parted. There, right below them, was a head more fearful than anything Beth had imagined. There was no doubt of the reality of this fearful apparition. The jaws and teeth that Harvey had spoken about were even worse than he had predicted. Slowly, slowly, those loathsome jaws parted. Beth looked down into that awful gulf, like a great dark pit, opening to receive her. There were the two rows of gleaming white teeth ready to devour girls who screamed. How she kept from screaming she never knew. Perhaps she was too much paralyzed with fear. However, she kept so still that she hardly breathed. The color ebbed out of her face.

Harvey picked up some meat that lay on the wharf beside him, and threw that and the bread into the waiting mouth below. The jaws snapped together, and opened again as suddenly.

Beth shuddered a little, involuntarily. She wondered if she would have disappeared as quickly as the meat if she had screamed.

Harvey had no more food for the animal below. It waited an instant, then slowly sank. The waters closed where the head had been. Beth felt as though she were wakening from a horrible nightmare.

"Three cheers for Beth," cried Harvey so unexpectedly that she gave a great start.

"Was it a dragon?" asked Beth with her eyes unnaturally big.

He laughed. "A dragon—— No, indeed. It's only a 'gator."

"A 'gator—— Would it really have eaten me if I had screamed?"

"It might, although I said that to try you. They do say, though, that 'gators sometimes eat pickaninnies. The Northerners who come down here winters are killing off the 'gators pretty fast, so the pickaninnies are likely to live. Now mind, Beth, don't say a word about my 'gator. You see if my folks heard about it, they might put a stop to my feeding it. They don't think 'gators as nice as I do."

"I think they are just horrid."

Harvey laughed. "Oh, you'll like them in time."

She had her doubts about ever being fond of such pets, but did not say so.

"I can't whistle, but would it come if I could whistle, Harvey?"

He looked very superior. "No, indeed. It won't come for any one but me."

"How did you get it to come for you?"

"Well, you see, I used to watch that 'gator in the river; then began bringing food for it. I reckon it thought that an easy way to live, and it soon grew to know me. Then it learned my whistle. That's all."

Beth now remembered that her half hour must be more than over.

"Harvey, I must go. Good-bye."

"Wait a minute. I say, I really like you, and will teach you how to fish some day."

This was the greatest compliment he could pay her, for he was an expert angler, and had never allowed a girl to share in the sport with him. Such an invitation as he had just extended surprised even himself, but he actually hoped that it would be accepted. He even decided to set a definite time.

"Come here—well, say Monday afternoon between four and five."

"I'll come if mamma will let me."

"Remember, you mustn't tell any one about the 'gator."

"Not even mamma?"

"No, indeed. You wouldn't break your word, would you?"

"I never do that."

"You're a trump, Beth. Good-bye."

She skipped back towards the house, revelling in her adventure now that it was over. Being called a trump by Harvey pleased her, but even this praise only half reconciled her for keeping any secret from her mother.

Halfway up the avenue, a homely, impudent, scraggy little dog, sprang from among the trees and yelped at Beth. A ragged little darky followed. Beth had never seen any human being quite so ragged.

"Come 'way, Fritz. What yo' mean by jumpin' on de missy?"

Beth eyed doubtfully both the dog and his master. The latter looked at her reassuringly.

"Yo' needn't be 'fraid, missy. I won't let Fritz hurt yo'."

"I—afraid—of him! He don't look as if he could harm anything," and Beth laughed.

The boy appeared grieved.

"Really, missy, he's a wonderful dog. I'll show yo' what he can do. Come, Fritz, dance for missy."

The ragged leader held up a warning finger. Fritz wagged his stubby tail, but did not budge.

"Come, come, Fritz. Dance for de missy."

Fritz wagged his stubby tail more vigorously, but gave no other response. The boy looked wise.

"He's bashful, missy, jes' like me. Perhaps, if I whipped him like my mother whips me——"

"Does she whip you?"

"Yes, 'deed she does—if she kotches me," added the boy laughingly. "If I'd whip Fritz, he'd dance, but I likes him too well to whip him."

Beth liked all dogs, with or without pedigree, and said warmly:

"I wouldn't whip him either, but it's too bad he won't dance. I'd really like to see him."

Again the boy said coaxingly, "Fritz, do dance," but the dog was not to be coaxed.

The boy frowned. "Yo'll think he can't dance, but 'deed he can. Maybe, if I dance, he'll dance too."

At the word, the ragged pickaninny began whistling, and then he capered around and around performing some wonderful steps. Whereupon Fritz began to bark and caught at his master's heels.

"Stop, Fritz, stop," but the dog would not heed, and so the dancing came to a sudden stand-still.

The pickaninny cocked his head on one side and whispered to Beth:

"He's out of sorts with me. I'm disgraced in his sight. He can dance so much bettah 'n me."

"Can he really?"

"Oh, a hundred times bettah."

"He must be a wonderful dog"—Beth was about to add, "Although he doesn't look it," and then desisted out of consideration for the dog's master.

"He's mighty smart. Why, 'less yo'd see all the tricks he does, yo'd never believe dem. Besides dancin', he jumps the rope, plays ball, says his prayers, gives his paw, jumps that high yo' wouldn't b'lieve it possible, rolls over——"

"What kind of dog is he?"

The boy scratched his head. "Well, missy, I can't jes' 'xactly say."

"If he is so very wonderful, you ought to know."

The boy was nonplused for a moment. Then he declared triumphantly; "Angels am very wonderful, ain't they? But yo' can't say 'xactly what they am."

Beth had not been much impressed by the dog, but now she began to feel astounded that she had had so little discernment.

"I'd like to own such a dog," she said.

"I'd give him to yo', only I couldn't spare him. Fritz never goes any place widout me. But, I'll tell yo' what: I'll let yo' play with him when yo' want to."

"Do you work for us?"

Again the boy laughed. "I work for yo'? No, 'deed; I'se too no 'count to work for the likes of yo'. I wuz jes' cuttin' 'cross fields through yo'r yard. If Titus found me here, he'd kick me an' Fritz out."

"What is your name?"

"Caesar Augustus Jones, but they calls me Gustus. I wish I could work for yo'."

Beth pondered a moment. "If you did, would you keep Fritz here?"

Gustus caught the trend of her thoughts. His eyes sparkled and his teeth gleamed.

"Me and Fritz 'd stay all the time—nights, too, if yo' wanted."

"I'll ask papa. He'll take you to please me, I know. Come on."

Gustus hung back, and his face sobered.

"Why, what's the matter?"

"Titus 'll kick me."

"I won't let him. Come on."

Thus encouraged, Gustus and Fritz followed her as she ran to the front steps, and on into a large old-fashioned hall. She stopped, momentarily, to peek into rooms on either side. There were two apartments on the right. She afterwards learned that they were parlor and library. On the left was one spacious room designed either for a sitting-room or a bedroom.

At the end of the hall was the dining-room, running two-thirds of the way across the house. To Beth's surprise, she found the table unset, and no one within. She feared she had missed luncheon. Chancing, however, to look out through an open door, she immediately gave a little cry of delight, for she beheld Mr. and Mrs. Davenport and Marian seated at a table on the roomy piazza that ran between the dining-room and the kitchen.

Beth seized Gustus by the hand and drew him towards the family party. Fritz bounded and yelped at their heels. His cries attracted the attention of the occupants of the piazza.

"Why, Elizabeth Davenport, what——"

"Oh, papa, this is Gustus, and I want you to let him work for us. This wonderful, wonderful dog is his, and if Gustus works for us, I can have Fritz to play with."

Beth stopped an instant for breath, which gave some of the others a chance to speak.

"Mamma, aren't his rags disgraceful?" whispered Marian to her mother.

"James, what shall we do?"

Mr. Davenport addressed the boy. "Are you looking for work?"

Gustus hung his head, but managed to say:

"Yes, massa, an' little missy 'lowed yo'd hire me and Fritz."

"Oh, papa, please, please hire them. Fritz is such a very wonderful dog."

Whereupon Indianna Scott, who was acting as waitress, spoke up:

"Don't yo' b'lieve dat, missy. Dat dog am nothin' but a no 'count fice."

Beth had never heard a dog called a fice. She feared it might be something very terrible. Afterwards she learned that it was a Southern provincialism for a common dog.

"Do you know the boy, Indianna?"

"I know of him, massa. His paw am dead, an' his maw has a dozen or so of chilun, an' dey are so pooh dat the maw can't get clothes 'nuff to cover dem. Dey say as how dis boy am always braggin' of his dog, and dat the dog am no 'count."

Gustus lost his hang-dog appearance. His eyes snapped.

"Dat ain't true. Fritz kin do all I say, only he's bashful."

Fritz did not appear very bashful, but was capering around Beth. However, her heart was won, and she cried:

"Anyway, Gustus, you and I love Fritz, don't we? Dear papa, please, please keep them."

"What can you do, Gustus?" he asked slowly.

"I—I kin brush flies," cried he exultantly.

"The boy must have some clothes, anyway. Come with me, and we'll see what we can do for you," said Mrs. Davenport.

Beth felt that she had won. In her joy she cried:

"Here, Fritz, you stay with me."

Fritz gladly obeyed. His hungry little stomach craved some of the chicken a la Creole which was being passed to Beth. As she started to put some of it into her mouth, she felt something pawing her lap. Fritz was making his wants known. Needless to say, he got some chicken from her, and from that time on these two became fast friends.

On Monday morning, Gustus came to Beth, bringing a cat with three kittens. The cat was of only a common breed, but Beth was delighted with the present.

Gustus was no longer ragged, but he looked very comical. There had been no boy's clothes in the house for him, and so Mrs. Davenport had fitted him out in an old suit of her husband's until another could be had. Of course, everything was much too large for Gustus, but he was as proud as Lucifer. He strutted up and down before Beth with his hands in his pockets and Fritz as usual tagging at his heels.

"Missy, I looks like de quality now shure, don't I?" he asked, grinning from ear to ear; and, not waiting for an answer, he added, "Yo'se been powerful good to me, missy, an' I'm goin' to give yo' Fritz, too."

Such generosity quite overcame Beth. "But, Gustus, I couldn't think of taking him away from you."

"Don't yo' worry, missy," he answered with a chuckle. "Yo' ain't takin' him 'way from me. I'se yo'r niggah now. Yo' owns Fritz an' me."

Beth hardly knew what to say. She thought it would be wrong to "own" Gustus. Slave days were a thing of the past. However, his devotion made her feel self-important.

"Well, Gustus, you must be a good boy," was all she could think to say.

"Yes, 'deed, missy. Come with me, an' I'll show yo' a bird's nest."

"I can't, Gustus. Mamma told me I must play indoors unless it clears. You know she's gone to town with Marian to see about a school for her. I'm not to go until next winter.

"I went to school once for a little while," she continued presently. "It happened this way: Marian attended a private school kept by a poor lady that mamma felt sorry for. Marian was not well, so mamma let me go in her place, so the lady wouldn't lose money. They didn't think I'd study hard, but, Gustus, I like to know things, and learning to read was a great help. So I studied very hard. Then I was taken very sick and was out of my head. I talked about books all the time. The doctor said I came near having brain fever, and it wouldn't do for me to go for awhile. I don't believe it would hurt me, but that's why I'm not going to school this year. Did you ever go to school, Gustus?"

"No, missy; me an' Fritz don't need no larnin'."

"But you do, Gustus, and I'm going to teach you."

He did not look particularly pleased at the offer. Nevertheless, Beth put the cat and the kittens down, and started to run for her books.

Bent as usual on mischief, Fritz made a dive and, catching the prettiest kitten by the neck, started away with it. The mother cat was after him in an instant. Her back was ruffled, and she struck Fritz with her sharp paw. He dropped the kitten and ran howling from the room. Gustus thought it a good opportunity to escape and started after Fritz.

"Gustus, come back," called Beth.

He looked crestfallen, but felt in duty bound to do as his little mistress bade. She brought her books, and had Gustus sit down beside her. Then she tried him with the alphabet. He proved woefully ignorant. After pointing out to him, A, B, and C, many, many times, she said:

"Show me A, Gustus."

He grinned. "A what, missy?"

"The letter A, of course, g——" She almost said "goosie," but thought in time that such a word would not be dignified for a teacher to use.

She did not find the fun in teaching that she had expected. Nevertheless, she persevered. Her face grew flushed as Gustus proved himself more and more ignorant.

When Mrs. Davenport returned from town, she found Beth at her self-imposed task.

"Mamma, Gustus ought to go to school."

"I don't wants to go," he cried, his eyes rolling so there was hardly any black visible in them.

Mrs. Davenport did not press the point. She intended to talk it over with her husband.

"Mr. Davenport and I bought these for you," she said, untying a package and drawing out a suit of boy's clothes, stockings, shoes, and underwear.

Gustus's pride now passed all bounds. He let forth a perfect avalanche of thanks, using large words, the meaning of which he had little idea. Even young darkies like big-sounding speech.

The morning passed quickly to Beth. To her delight, towards noon the sun broke through the clouds. This reminded her of Harvey Baker's invitation to fish.

"Mamma, may I go down to the wharf?" she asked immediately after luncheon. "Harvey Baker asked me to fish with him. He's a neighbor's boy I met Saturday."

"Well, I declare. Why didn't you tell me before?"

"I forgot." She had had so many things to think of and talk about, that she had not thought much about Harvey except at night. Then that awful alligator haunted her until she wanted to call her mamma, but she had not dared because of her promise.

"May I go, mamma?"

"But I do not know anything about him. He may not be nice at all."

Maggie, who chanced to be present, now spoke up:

"De Bakers am quality, Miss Mary. I wouldn't be feared to let missy go wid any Baker. I'se s'prised, do, dat Harvey axed her, 'cause he don't like girls. Are yo' sure, honey, he axed yo'?"

"Of course I am."

"Den yo' needn't fear, Miss Mary. Harvey's a big boy, and he'll take good care of her."

With this assurance, Mrs. Davenport gave her consent.

Beth put on her hat and hurried down the avenue to the river. On the end of the wharf sat Harvey, holding a fishing pole. He turned his head at her approach.

"Hello, Beth. I hardly expected you. I thought your mamma might be 'fraid to let you come."

She smiled. "Maggie said you were 'quality,' and would take care of me."

Harvey gave a grunt. "Don't know about quality, but as long as your mamma trusted me, she shan't repent. Take this line, and go to fishing."

He handed one to her and she dropped the end into the water. Harvey broke into a hearty laugh.

"You don't 'spect to catch fish without bait, do you?"

She answered meekly: "I s'pose not, but what is bait?"

Harvey laughed harder than ever. "Well, you are silly."

Beth felt aggrieved over being called silly, but she tried to look dignified.

"Don't care, you're just as silly as me. My papa says if people don't keep quiet, they'll scare all the fish away. You're laughing awful loud."

He immediately sobered down. "True for you, Beth. It is silly to laugh and you're a wise girl. You'll make a good fisher. Here, I'll put the bait on for you."

He baited her line and threw it out into deep water for her.

She waited patiently for the fish to bite, but it seemed as if her patience was to go unrewarded. She wished for Harvey's good opinion, and so she did not even speak. It proved pretty dull work and to make matters worse, Harvey pulled in a number of fish, while she did not get even a nibble.

She would have given up in despair had not her pride prevented. Harvey felt sorry for her and proved himself magnanimous.

"Beth, the fish are biting lively here. You take my place—yes, you must, and I'll go around on the other side."

Matters did not mend for Beth even with the change. The fish seemed to follow the boy. He caught several on the other side of the wharf, while the patient little fisher maiden waited in vain for the fish to take pity on her.

Presently, she almost feel asleep, fishing proved so uninteresting. Then there was a terrible jerk on her line, followed by a steady pull. Beth was afraid the alligator had swallowed the line, and that she would be dragged into the river. Nevertheless, she hung on bravely.

"Harvey, Harvey, come quick. I can't pull it in. Come quick."

He rushed to her assistance. The two children began pulling together. Harvey's eyes grew almost as big as his companion's.

"Beth, I believe you've caught a whale."

It was a very hard tug for them, but finally something black wiggled out of the water. Beth gave a little cry.

"Harvey, it's a snake. I don't want it, do you?"

His eyes sparkled. "It's no snake, Beth. It's an eel and a beauty too. My, what a monster!"

"Are you sure it is not a snake?"

"Of course I am. Darkies call them second cousins to snakes and won't eat them, but they are fine eating. My, just see him squirm. Isn't he big, though? You're a brick, Beth, to catch him."

By this time, the eel was safely landed on the wharf, and proved to be indeed a monster. It was a wonder that the children had ever been able to pull him in. Harvey tried to unhook him, but failed; for just as the boy thought he had him, the eel would slip away.

"Let's take him up to the house on the line. I want to show him to mamma," cried Beth.

"All right, but first we'll fix some lines for crabs."

"What are crabs?"

"My, don't you know? Well, we'll catch some when we come back and then you'll see."

He took some lines without hooks and tied raw beef on the ends of them. Then he threw them into the water.

Beth, as proud as if she had caught a tarpon, took up her line with the eel on it, and away marched the children to the house.

"Mamma, just see what I caught."

"Well, I declare," cried Mrs. Davenport at sight of the eel. "Did you really catch that all by yourself, child?"

"Yes, mamma, except that Harvey had to help me pull it in, or else the eel would have pulled me into the water. It tugged awfully hard, but I wouldn't let go. Mamma, this is Harvey and we're just having heaps of fun." She had forgotten, already, that a few minutes before she thought she was having a very stupid time.

Harvey raised his cap. Mrs. Davenport liked the boy's appearance.

"Mamma, you keep the eel to show papa. Harvey and I are going back to catch crabs. Come on, Harvey."

Mrs. Davenport detained them a moment. "Harvey, you'll take good care of my little girl, won't you?"

"Yes, ma'am," and back the children scampered to the wharf.

"You see if there is anything on this line, Beth, while I go around to the other lines. If there is, call me, and I'll come with the net, and help you land him."

Away went Harvey. Beth began pulling in the line. There, hanging on the meat with two awful claws, was a great big greenish crab. His eyes bulged out, and altogether he looked so fierce that Beth was somewhat frightened at him, but she wished to surprise Harvey. Therefore she overcame her fear, and continued pulling up the line. For a wonder, the crab hung on all the way from the water to the wharf. Beth was delighted to think she had caught something without Harvey's aid. Mr. Crab, however, as soon as he felt himself trapped, let go of the meat, and began crawling towards the side of the wharf. Beth saw her prize vanishing, and made a dive for it. Up went the crab's claws, and caught the child by the fingers. A scream immediately rent the air.

Harvey came running to find the cause of the commotion. He had to laugh, notwithstanding tears were streaming down Beth's face. She looked so ludicrous, dancing up and down with that awful crab hanging on like grim death.

"'Beware of the Jabberwock that bites, my child,'" quoted Harvey.

Beth stopped screaming an instant. "I thought it was a crab."

"So it is. I was just repeating a line from Alice in Wonderland."

While Harvey spoke, he was trying to loosen the crab. The harder he pulled, the more angry it grew, and the harder it bit. Finally, he pulled so desperately that the crab came, but a claw was left hanging to poor Beth's finger.

Harvey started to drop the crab. Again Beth ceased her yelling.

"Harvey, don't you dare let my crab go. Put it in the basket and then come and get this awful claw off my finger."

He did as he was bid, secretly admiring his little friend's pluck. They had a great time getting off the dismembered claw, but, finally, they succeeded. Poor Beth's finger was bitten to the bone. Harvey really felt very sympathetic, but, boy-like, was somewhat bashful about expressing it.

"Beth, does it hurt much?" was all he said.

"Pretty bad," she admitted, forcing back the tears. "Say, Harvey, were there any other crabs?"

"I had time to look at only two of the lines, I got three crabs from the two. There were two on one line, so with yours we have four. But never mind the crabs; we must go up to the house and have your finger dressed."

"No, we must first see if there are any other crabs. Here, tie my handkerchief around my finger. I guess I can stand it awhile."

The handkerchief was tied about the sore finger, and then Beth watched Harvey while he pulled up the lines. There were crabs on every one, and on some of them there were two. Harvey would pull the crabs to the surface of the water and then scoop the net under them. In moving the crabs from the net to the basket, he held them by the hind legs, because, in this position, a crab cannot reach around with its claws to bite.

Altogether, the children caught about fifteen crabs, and they took them up to the house with them. Arriving there, they found that Mrs. Davenport had driven to town to bring home Mr. Davenport and Marian.

Beth therefore went to Maggie about the finger, and Harvey accompanied her. Maggie proved very sympathetic.

"Yo' precious little honey, yo'. Dat finger jes' am awful, but I knows what'll cure it in no time. Here, yo', Gustus, yo' run and fetch me some tar. Hurry, yo' lazy niggah yo'. Dar, dar, honey chile, it'll be all right in no time. Tar am jes' fine for a sore."

For a wonder, Gustus did hurry and was back in no time with the tar. Maggie dressed the wound with it very gently and Beth began to feel easier immediately.

"Now, honey, it'll be all right. If yo'd only known, and jes' held yo'r finger with dat crab out over the watah, it 'd have seen its shadah and gone aftah it."

"Here, Beth," Harvey now said, "you can have all of the crabs; I guess I'd better go."

"Please don't go, Harvey; I want you to stay. Say, Harvey, are crabs good to eat?"

"Of course, they are. You just put them in water and boil them and they are dandy."

"Oh, how I wish we could boil them. Wouldn't papa be surprised? Maggie, can't we boil them?" and Beth seized the cook's hand and held it, pressing it coaxingly.

"Law, honey, dar ain't no room on de stove. I's gettin' de dinnah."

"Please, Maggie, make room," continued Beth, already having learned her power of persuasion over her new mammy.

"I can't, honey, but I'll tell yo' what. Yo' an' Harvey kin do it if he knows how to boil dem."

"Of course, I know how."

"Well, I'll let yo' take dis big iron kettle into de library. Yo' kin put de kettle on de fire, dar, an' boil dem."

Beth danced up and down for joy. "Oh, won't that be fun. Thank you, Maggie. You're a lovely Maggie."

"Dar ain't no hot watah, but I'll take dis cold watah in fur yo', an' it'll heat in no time."

Maggie carried the kettle, half-filled with water, and placed it securely, as she thought, on the big open wood-fire in the library. Then she left the children to their own devices, Fritz alone keeping them company. A watched kettle never boils, and the children did not have the patience to test the truth of this.

"I hate to wait for water to boil," said Beth.

Just then Harvey conceived a brilliant idea.

"Say, Beth, we'll put in the crabs before it begins to boil. Then we can play until they're done."

"And the cold water won't hurt them like hot, will it, Harvey?"

Without answering, he emptied the crabs into the kettle. Beth viewed them critically.

"There's the horrid old thing that bit me. I know him by his one claw."

"He shall be the first one eaten to show how mean he was. What shall we play?"

"Let's play stage."

He accepted the suggestion, and while they played, Fritz snoozed comfortably before the fire.

The water began to get hot, and the crabs became lively. They crawled around so vigorously that a log slipped and upset the kettle. There was a sizzling of water, and, in an instant, fifteen crabs were loose in the Davenport library.

This avalanche of crabs awakened Fritz, who opened his eyes halfway and beheld a crab at his very nose. Perhaps in his sleepiness, he thought it another kind of kitten ready for a frolic. At any rate, he put out his paw towards the crab, which met his advances more than halfway. With a wild howl, Fritz jumped up on three feet while the crab clung grimly to the fourth.

"Poor Fritz! You, too, should beware of the Jabberwock that bites," cried Beth from the lounge where she had taken refuge.

Around and around whirled Fritz in a most lively manner.

"Just see him," cried Beth triumphantly. "Gustus always said he could dance, and this proves it."

Harvey, who was trying to catch some of the crabs, grunted disdainfully, but continued his unsuccessful chase without any other comment.

Fortunately for Fritz, the crab dropped of its own accord, and the frightened dog tore like a streak of lightning through the house and on outdoors.

Once Harvey stooped and thought he surely had a crab, when Beth beheld another crab with claws upstretched right behind.

"Harvey, come here quick," cried Beth; "a crab's going to bite you in the back."

Thereupon, he, too, jumped upon the lounge to escape the threatening claws. Immediately, however, he said:

"Oh, pshaw, it's silly to be afraid of crabs. I'm going to get down again." Beth, however, caught hold of his hand, saying:

"No, I won't let you. I wish somebody would come to help us. I'm going to try to make Maggie hear me. Maggie. Maggie."

Back from the kitchen floated the slow tones of Maggie.

"What am it, honey?"

"Maggie, come here, quick."

Then they heard the soft tread of her feet crossing the piazza.

"She's coming, Harvey."

Maggie poked her head through the door and beheld the children upon the lounge.

"Laws a massy, what am yo' doin' thar, honeys?"

Then she saw the crabs on the floor, and she began to laugh.

Now when Maggie laughed it meant more than ordinary merriment. Her eyes rolled and her sides shook.

"Ha, ha, ha. Oh my, oh me. Ha, ha, ha. Well, dis am a sight. I jes' 'lows I must go to Titus about dis yere. Ha, ha, ha," and away she went.

"But, Maggie," cried Beth in protest, "I think you're real mean. We want you to help us catch them."

But Maggie paid no attention to the appeal.

The one-clawed crab stopped for a moment in front of the lounge.

"Harvey, he's making fun of us, too,"

"The impudent thing," exclaimed Harvey, jumping down.

By a dexterous move, he captured the crab.

"Don't you come back here with it," commanded Beth.

There was a space free from crabs between Harvey and the window. He ran to the window and threw the crab out.

January chanced to be working not far away, and Harvey spied him.

"Come in here quick, January," he cried. "There are a lot of crabs after us."

January, for a wonder, came running, and his valor for once proved remarkable. He showed no fear of the crabs, and darted around so quickly that he caught every one in the room. The one-legged one that Harvey had thrown out of the window was never found. Perhaps it made its way back to the river, and told of its harrowing experiences on land, and especially how it had lost its claw.

Fritz limped for several days after his experience with the crab and Beth had a terrible nightmare that night in which crabs were giants with claws of iron.

Beth was seated with Fritz and the kittens in a large Mexican hammock on the front porch. She held up a warning finger to her mother who stood in the doorway.

"Mamma, do not frighten birdie away. He is not the least bit afraid of me, and I love to hear him sing."

Mrs. Davenport was surprised to see a mocking bird perched on the railing directly by the side of Beth. His little head was cocked sidewise, and floods of sweet sounds issued from his throat.

His spouse, who was guarding their nest up in the big live oak in the front yard, trilled her limited paeon of praise.

Beth, who often acted as interpreter for beast and bird, thought the proud wife-bird meant to say:

"Bravo. Isn't he the most wonderful tenor that ever lived? Are you surprised that I love him so? He is the best and smartest husband in all the world."

Fritz and black pussy grew restless. She spit at him, and he barked at her.

"Now, my dears, do let me enjoy this beautiful music in peace," Beth said reprovingly.

Hardly had she spoken, before black pussy sprang away, and Fritz was after her in an instant.

Beth did not dare follow for fear of frightening away Mr. Mocking Bird, who stopped singing as cat and dog scampered away, but who had not yet flown back to his mate. He was watching fearfully every move of the frolicsome pair.

Away scurried kitty to the other end of the porch with Fritz a close second. Suddenly, she turned, settling down on her back with her claws out-stretched, ready to receive Fritz. In an instant he was on her. Over and over they rolled in their wild play. Fritz became too rough to suit puss, and she gave him a sudden dab with her sharp little claws. The blow disabled him for a moment, allowing puss to spring away from him. She scampered down the steps and towards the big tree with Fritz again after her.

Mr. Mocking Bird was up in arms in an instant. How dared the impudent creatures approach that tree where dwelt his wife and children! He flew to the rescue.

Mrs. Mocking Bird, too, had grown so nervous that she, also, left her young, and joined in the fray. Together Mr. and Mrs. Mocking Bird dived and pecked at the cat and the dog in a most ferocious manner.

Beth rushed out, ready to assist the birds, if necessary, but her aid was not needed.

Black puss and Fritz were so taken by surprise at the fierce onslaught of the birds that they turned and sneaked away as fast as they could go. Thus, through the power of love, the weaker triumphed over the stronger. Later on the mocking birds also came out victors in another contest, and against greater numbers, too. It happened in this wise:

As the days went by, Beth grew somewhat restless. She did not exactly tire of Fritz, puss, and Arabella, but she longed for diversion. Then one evening Mr. Davenport brought home a large coop of chickens, and calling Beth to him, he said:

"You are to tend these, daughter, and hunt eggs every day."

"Oh you dear, good papa. I want to take one of the sweet things in my arms."

Thereupon she tried to get a chicken, but somehow, in so doing, she upset the coop. Away flurried the chickens in every direction. Beth felt ready to cry.

"Never mind," said Mr. Davenport; "when they go to roost to-night, we can catch them, and put them in the chicken house."

That night, some of the chickens perched on sheds, and some on trees. A few had the hardihood to fly up on the branches of the live oak in the front yard.

Mrs. Mocking Bird was just falling asleep in the nest with her young, and Mr. Mocking Bird was already asleep not far from her side. The chickens aroused the mother bird in an instant.

"Dearest," she piped, "I hear a dreadful noise down-stairs. I think there must be burglars in the house. You must go down and see."

Now, every one knows that a man hates to be disturbed from a sound sleep, and Mr. Mocking Bird proved no exception.

"Oh, birdie," he grumbled, "do leave me alone; you're always imagining things."

"Imagining things, am I?" she answered shrilly. "Just hear that awful noise. You're so lazy that you would see me and the children murdered before you'd move. If you don't want me to think you a coward, you'll go down this instant. This instant, I say."

Now Mr. Mocking Bird was, as Mrs. Mocking Bird knew, very brave, and he also loved her praise. So he only blinked his eyes once more, and literally flew down-stairs. There he spied the chickens settling down for a good night's rest. Such impudence aroused his ire. He did not hesitate a second, but dived into their midst and pecked furiously at the poor, unsuspecting intruders. The chickens, taken utterly by surprise, fluttered to the ground without offering any resistance. They cackled so loudly, however, that the noise brought Titus to their rescue, and he succeeded in capturing the badly frightened hens.

Mr. Mocking Bird, triumphant, ascended to his anxious spouse.

"Dearest," she cried, "you're not hurt, are you?"

"Hurt!" he repeated boastfully, "hurt? Well, I should say not. It was only some upstart chickens who dared to sneak into the house, and I'm more than a match for any number of such. I guess we shan't be disturbed again by chickens or by impudent dogs and cats."

Mr. Mocking Bird proved right in his surmise. The birds thereafter enjoyed their home without further intrusion.

Under Beth's care, the chickens flourished finely. They laid many an egg which in due time were placed beneath mamma hens.

There was a very proud little girl in the Davenport family when finally balls of yellow broke through the egg shells.

Then Beth began saving eggs for Easter, and, on Easter Day, she found that she had enough to give every darky one, besides having all that were wanted for her own family.

This Eastertide brought new diversions to Beth. For one thing, she received an invitation to spend a night in town with a little girl named Laura Corner. The Davenports and the Corners had been friends in the North before the two families moved South.

Beth had never before spent a night away from home. She thought it would be a "sperience" to go, and prevailed upon Mrs. Davenport to let her accept the invitation.

The momentous day arrived at last. Beth wished to take all her belongings with her, from Fritz to a small trunk. She had to be content, however, with a valise.

Fritz and Arabella were admonished to be good during her absence, and the chickens were entrusted to Marian's care.

Mrs. Davenport drove Beth to town. Upon reaching the Corners' home, Beth's heart sank unaccountably, and she had a hard time to keep the tears back, when she kissed her mother good-bye. However, Laura and the Corners were so very cordial that her spirits soon revived.

In the afternoon several little girls, who had been invited to play, came in. Among the number was one who especially attracted Beth. She was slight and graceful. Her hair was golden and her eyes were blue. Beth, of course, was introduced to all the girls, but did not catch the name of this one.

"She looks like that picture of the cherub we have at home," decided Beth. "I wonder what her name is. I guess I'll call her 'Cherub' to myself. Cherub, you're very pretty, but you're too quiet to be much fun."

Most of the little girls had their dolls with them; all, in fact, excepting Beth and the "Cherub." The latter sat apart from the other children. She looked so very demure that Beth thought her bashful, and took pity on her. Seating herself beside her, she asked:

"Wouldn't your mamma let you bring your doll? My mamma thought I had better not bring mine so far."

The "Cherub" showed little interest in the conversation. She answered curtly:

"I haven't a doll."

Beth's eyes opened in surprise. "You haven't any doll? What a pity."

Then she hesitated. She feared the "Cherub" might be too poor to afford dolls. She was soon undeceived, however, by the "Cherub" exclaiming:

"I don't think it a pity. I don't care for dolls; they're a nuisance. I like to play outdoors."

"So do I."

The "Cherub" grew animated. "Do you? Say, can you climb trees and walk on stilts and——"

"What are stilts?"

"Don't you know?" There was a slight contempt expressed for such woeful ignorance. "They are long pieces of wood with places for your feet up from the ground. It's just as if you had wooden legs, only they make you tall so that you feel quite grown up."

"I'd like to walk on stilts."

"Would you? Where do you live?"

"Out on the old shell road."

"What! are your folks the people who bought the place near us?"

"Do you live on the shell road, too?" Beth was delighted. She was beginning to think the "Cherub" might prove very companionable.

"Yes. Your name is Beth Davenport, isn't it? Mine's Julia Gordon. Say, Beth, I'll come to see you and teach you how to walk on stilts if you like."

"Will you, really? When will you come?"

"To-morrow morning."

Beth's face fell. "Oh, that's a pity. I shan't be home. I'm going to stay here all night."

"Well, never mind. I'll come the morning after."

"All right, don't forget."

"No, I'll be there right after breakfast."

Games were started at this juncture, and then came refreshments. Soon afterwards, the guests took their departure. The "Cherub" said in parting:

"We'll have a jolly time with the stilts, Beth. I've been wanting to teach somebody for a long time."

Laura and Beth had a merry time together until tea-time. Then, after tea, Laura's older sister, Florrie, told them stories. Beth was simply fascinated. She could listen forever, she thought, and not grow weary. Florrie made her characters live by the magic of her voice and words.

Just before it was time for the children to retire, Florrie took down the Bible and read a chapter to them.

Then the children went up-stairs to bed. They had a pillow fight after they were in their night-dresses. Sad to relate, in the scuffle, their clothes were strewn around the room, and Beth carelessly failed to gather hers together again.

They talked in bed until Mrs. Corner called to them to stop. Laura soon fell asleep, but Beth's heart, again, grew heavy. She missed the good-night kiss from her mamma, and tears rose to her eyes. She tried not to sob for fear of awakening Laura. Minutes seemed hours to her. She realized more than ever the depth of her love for her mother, and she resolved in future to be the best girl alive. That resolve somehow quieted her so that she fell asleep and forgot her heartache in pleasant dreams. She dreamed that it was the day after the morrow, and that Julia had come with stilts so high that they touched the clouds. Beth walked on them without the least difficulty; then, all of a sudden, she dropped them, and found herself flying with the utmost ease. She wondered she had never tried it before; it was so very delightful to fly. But, suddenly, the clouds turned into smoke and fire. Beth awakened with a start. The room was very light, as light as if it was broad daylight.

Beth gave Laura a poke, "Laura, it must be late. See how light it is."

Laura jumped out of bed, and, running to one of the windows, raised the curtain. Both of the children cried out in fright then. Flames shot and curled to the very window of their room. Laura could not tell whether their house was on fire or not. She feared so, and the house next door was one mass of flames.

Beth sprang out of bed, too.

"Mamma, mamma," screamed Laura. Nobody answered. "Come quick or we'll burn." Still only the crackling of the flames could be heard.

"They've forgotten us," cried Beth with chattering teeth. "Laura, you know the way down-stairs, don't you? Let's go."

"We must dress first," answered Laura.

Beth stamped her foot. "I'm not going to wait to dress. Besides, I don't know where my things are. Oh, why didn't I mind mamma and put them away carefully. Now they'll burn."

The more prudent Laura gathered up her clothes from a chair where she had laid them, and led the way into the hall. They found it pitch dark there.

Suddenly Laura stopped. "Oh, Beth, I can't let it burn."

"What will burn, Laura?"

"My beautiful new Easter hat. I must go for it."

"Laura Corner, you must not go back for it. We ourselves might burn while you were getting it."

But Laura had thrust her clothes into Beth's unwilling arms, and was off like a flash to rescue her Easter hat. Beth did not know the way sufficiently well to go on by herself, and so, trembling, she awaited Laura's return.

Laura was soon back, pressing the precious hat close to her side. Such treatment was likely to do it great damage, but, in her excitement, Laura did not stop to think of this.

Down-stairs a light shone in the parlor. Guided by its friendly beams, Laura led the way there. No one was within. The house was deserted but for the two trembling girls.

"Beth, God alone can help us," and Laura's face was almost as white as the Easter hat under her arm.

Beth's lip trembled. "He's so far away. I wish mamma were here."

"Beth, God will hear us if we pray. Get down on your knees beside me."

"I'd rather run out into the street," answered Beth, who always believed in action rather than words.

"You're a wicked little girl. My mamma says I must never go on the street without some grown-up person. So get on your knees this minute."