Title: Golden Days for Boys and Girls, Vol. XII, Jan. 3, 1891

Author: Various

Editor: James Elverson

Release date: December 2, 2005 [eBook #17199]

Most recently updated: December 13, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Louise Hope, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

| Vol. XII—No. 6. | January 3, 1891. |

PHILADELPHIA:JAMES ELVERSON,PUBLISHER. |

|

|

"BIRTH IS MUCH, BUT BREEDING MORE." |

|

|

Complete Outfit for learning Telegraphy, and operating Short Lines of Telegraph, from a few feet to several miles in length. Consists of full size, well made Giant Sounder with Curved Key Combination Set as above, together with Battery, Book of Instruction, insulated Wire, Chemicals, and all necessary materials for operating. Price $3.75. Sent by express upon receipt of amount by Registered Letter, Money Order, Express Order or Postage Stamps. Morse Pamphlet of practical Telegraph Instructions free to any address. J. H. BUNNELL & CO., 76 Cortlandt Street, New York. Largest and Best Telegraph Supply House in America. MAGIC LANTERNS WANTED AND FOR SALE OR EXCHANGE. HARBACH & CO. 809 Filbert St. Phila. Pa.

CIRCULARS to young people only. Money for you. Address Novelty Typewriter Co., Oswego, N. Y.

CARDS Send 2c. Stamp for Sample Book of all the FINEST and Latest Style CARDS for 1891. We sell Genuine Cards, not Trash. UNION CARD CO., COLUMBUS, OHIO.

And STEREOPTICONS, all prices. Views

illustrating every subject for PUBLIC

EXHIBITIONS, etc. WORLD'S Fair Railway Puzzle. Lots of fun: sample 10c.; 3 for 25c. Morton & Co., Box 848, Chicago MINIATURE PHOTOGRAPHS 12 for 25c. Sample 2c. Copied from photographs or tintypes, which we return. THE BARTHOLOMEW STUDIO, Wallingford, Co. Advertising Rates for "Golden Days."

Single Insertions, ... 75c. per Agate line.

Eight Words average a line. Fourteen lines make one inch. Philadelphia, Pa. STAMPS.

STAMPS we lead; others follow. We are the world wreckers on low prices. Ten-cent sets—3 Malta, 2 Montserrat, 5 Newfoundland, 2 Paraguay, 4 Dominica Republic, 2 St. Vincent, 2 Sierra Leone, 5 Straits Settlements, 3 Suriname, 2 Tobago. 40-page price list, 2c. New coin catalogue, 10c. E. F. GAMBS, Coin and Stamp Dealer, 4 Sutter Street, San Francisco, Cal. STAMPS 100 all different, 10c.; 300 all different. $1.25; 500 all different, $2.25. price lists free. Agents wanted to sell stamps from my unequalled sheets at 33-1/3 per cent, com. Wm. E. Baitzell, 412 N. Howard St., Baltimore, Md 300 Mixed, rare Australian, etc., 10c.: 75 fine varieties and nice album, 10c. Illustrated list free. Agents wanted, 40 p.c. com. F. P. Vincent, Chatham, N. Y. STAMPS Agents! Approval Sheets, 1-3d com. List free. Conrath & Co., 1334 Lasalle St., St. Louis, Mo. STAMPS Price list FREE. Approval sheets 50 per ct. com. E. A. OBORNE, Jamaica, New York. STAMPS—Agents wanted for the very best approval sheets at 40 per ct. com. Putnam Bros., Lewiston, Me |

15 CENT PACKAGE OF GAMES

Game of Authors, 48 cards with directions. To introduce our goods and get new customers, we will send the whole lot to any address, freight paid, on receipt of 15c.; 2 lots for 25c.; 5 lots, 50c. Stamps taken. STAYNER & CO., Providence, R. I. CARDS FINEST GOODS, LATEST STYLES, LOWEST PRICES, SAMPLES FREE LAUREL CARD CO., CLINTONVILLE, CONN.

USE BOILING WATER OR MILK. CARDS NEW SAMPLE BOOK of Hidden Name, Silk Fringe, Gold, Silver and Tinted Edge Cards. The Finest ever offered for 2 cent stamp. NATIONAL CARD CO., SCIO, OHIO.

MAGIC LANTERN VIEWS

FOR SMALL LANTERNS. COMIC, BIBLE SCENERY, NOTED

PLACES SEND ONE CENT FOR NEW PRICE LIST

CAEL BROWN

155 WASHINGTON ST., CHICAGO, ILL.

CARDS! 30 Samples Free. Jewel Co., Clintonville, Conn.

ASTHMA

CURED

DR. TAFT'S ASTHMALENE never fails; send us your address, we will mail

trial BOTTLE

FREE

CARDS

LATEST STYLES, BEST PREMIUMS, 100 Popular Songs, 32 complete Love Stories, 11 thrilling Detective Stories and large catalogue, all for 10c silver. Handford & Co., Lincoln Park, N. J.

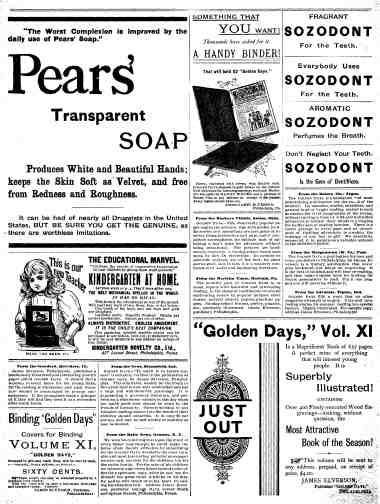

I CURE FITS! PLAYS Dialogues, Tableaux, Speakers, for School, Club & Parlor. Best out. Catalogue free. T. S. Denison, Chicago, Ill. THIS BINDER is light, strong and handsome, and the weekly issues of Golden Days are held together by it in the convenient form of a book, which can be kept lying on the reading-table. It is made of two white wires joined together in the centre, with slides on either

end for pressing the wires together, thus holding the papers together by pressure without mutilating them. We will furnish the Binders at Ten Cents apiece, postage prepaid. Address JAMES ELVERSON, Publisher, Philadelphia, Pa. |

|

DOCTORS RECOMMEND Ayer's Cherry Pectoral in preference to any other preparation designed for the cure of colds and coughs, because it is safe, palatable, and always efficacious.

"After an extensive practice of nearly one-third of a century, Ayer's

Cherry Pectoral is my cure for recent colds and coughs. I prescribe it,

and believe it to be the very best expectorant now offered to the

people. Ayer's medicines are constantly increasing in

popularity." —Dr. John C. Levis, Druggist, West Bridgewater,

Pa.

Ayer's Cherry Pectoral, |

|

|

The Western Pearl Co. will give away

1000 or more first-class safety bicycles (boy's or girl's style) for

advertising purposes. If you want one on very easy conditions, without

one cent of money for it. Address, enclosing 2 cent stamp for

particulars, SAMPLES 2c. World CARD Co. 47 Elder Cin'ti O.

To introduce our Watches and Jewelry, we will send the above beautiful Scarf Pin free to anyone. Cut this ad. out and return to us. Large illustrated catalogue sent free with pin. W. HILL & CO., Wholesale Jewelers, 11b Madison St., Chicago, Ill. 100 NEW SONGS (no 2 alike). 1 pk. May I. C. U. Home Cards. All the late flirtations, etc. 20 Fine Photos, large Ill. Cat., Lovers' Telegraph and 15 Versions of Love, all 10c. EASTERN SUPPLY CO. Laceyville, O.

32 COMPLETE Love Stories, 11 Thrilling Detective Stories and 100 Popular Songs, postpaid, 10c. (silver). J. Roush, L. Box 615, Frankfort, Ind.

10

CENTS (silver) pays for your address

in the "Agent's Directory," which goes

whirling all over the United States, and you will get hundreds of

samples, circulars, books, newspapers, magazines, etc., from those who

want agents. You will get lots of good reading free and will be WELL

PLEASED with the small investment. DO YOU PLAY CARDS? No game complete without our Patent Counters. Scores any game. Send 10 cents for a pair. 30 cents buys fine pack Cards and 100 Poker Chips. REED & CO., 84 Market St., Chicago, Ill. CATARRH CURED I will send FREE to every reader of this paper a copy of the original recipe for preparing the best and surest remedy ever discovered for the permanent and speedy cure of Catarrh. Over one million cures in five years. Send your name and address to Prof. J. A. LAWRENCE, 58 Warren Street, New York, and receive this free Recipe. Write to-day. A Postal Card will cost you but ONE CENT!!

FUN Game of Forfeit, with full directions, 275 Autograph Album Selections, 11 Parlor Games, 50 Conundrums. Game of Fortune. Mystic Age Table. Magic Music, Game of Letters. FREE The new book, Order of the Whistle. Language of Flowers, Morse Telegraph Alphabet, Game of Shadow Buff and 13 Magical Experiments. All the above on receipt of 3 cents for postage, etc. Address, NASSAU NOVELTY WORKS, 58 & 60 Fulton St., New York. SAMPLE BOOK of Cards, 2c. Globe Co., Wallingford, Ct.

A WHOLE PRINTING OUTFIT, COMPLETE AND PRACTICAL, Just as shown in cut. 3 Alphabets of neat Type. Bottle of Indelible Ink, Pad, Tweezers, in neat case with catalogue and directions "HOW TO BE A PRINTER." Sets up any name, prints cards, paper, envelopes, etc. marks linen. Worth 50c. The best gift for young people. Postpaid, only 25c., 3 for 60c., 6 for $1. Ag'ts wanted. Ingersol & Bro., 65 Cortlandt St., N. Y. City. 4 CTS. 100 Assorted U. S. and Foreign Stamps 4 cents; 500, 18 cents; 1000, 33 cents HANDFORD & CO., Lincoln Park, N. J. |

THE DOLLAR TYPEWRITER

A perfect and practical Type Writing machine for only ONE DOLLAR.

Exactly like cut; regular Remington type; does the same quality of work;

takes a fools cap sheet. Complete with paper holder, automatic feed,

perfect type wheel & inking roll; uses copying ink. Size 3x4x9

inches; weight, 12 oz. Satisfaction guaranteed. Circulars free;

AGENTS WANTED. Sent by express for $1.00; by mail,

15c. extra for postage. MOUTH ORGAN Chart teaches a tune in 10 minutes. Agts. watd. 2c. stamp. Music Novelty Co., Detroit, Mich.

GUNS

DOUBLE MOTHERS Be sure und use "Mrs. Winslow's Soothing Syrup" for your children while Teething.

FORCE BEARD OR HAIR. $25 A WEEK to LADY AGENTS "Victoria Protector" and rubber goods for ladies and children. Victoria by mail $... Circulars free. Mrs. L. E. Singleton, Box 865, Chicago, Ill. For boy or man, as an educator or as a source of amusement or income, at a small expense, get one of our PRINTING PRESSES

Specimen Book of type,

... cents.

Circular sent free. Amateur Printers' Guide Book. 15 cents.

SEND 30 CENTS

in stamps for elegant Concert Harmonica, worth $1.00. Money

refunded if not satisfactory. 100 SCRAP PICTURES & AGENT'S CARD OUTFIT 2c AND PRESENT FREE E. H. PARDEE, MONTOWESE, CONN.

PLAYS! OPIUM Morphine Habit Cured in 10 to 20 days. No pay till cured. Dr. J. Stephens, Lebanon, Ohio.

BARNEY & BERRY

Cards FREE Send your name and address on a postal card for all the Latest Styles of Silk Fringe, Photograph, Envelope, Beveled Edge, Crazy Edge Cards &c., Samples of all free. HOME and YOUTH, Cadiz, Ohio.

FREE SAMPLE CARDS. THE FINEST, CHEAPEST AND BEST. COSTLY OUTFIT FREE to all who will act as AGENT. Send 2c stamp for postage. U. S. CARD CO., CADIZ, OHIO.

DEAF

NESS & HEAD NOISES

CURED |

|

Children Cry for Pitcher's Castoria |

|

(Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1891, by James Elverson, in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C.)

| VOL. XII. | JAMES ELVERSON, Publisher. |

N. W. corner Ninth and Spruce Sts. |

| PHILADELPHIA, JANUARY 3, 1891. | ||

| TERMS | $3.00 Per Annum, In Advance. |

No. 6. |

"Discharged from your last situation, young man? For what reason?"

And the busy superintendent of the Pen Yan Road, one of the largest railway systems in the country, turned from his maps and statistics to glance suspiciously at the slight figure, before him.

Clear and prompt came the answer:

"For doing my duty, sir."

"Humph!" replied the official, shrugging his shoulders and eying the youthful speaker more closely. "Men—nor boys, for that matter—never lose situations from attention to business. You will have to find another excuse."

"I have no other, sir."

By this time the notice of the subordinate officials and clerks, of whom there were twenty or more in the company's spacious rooms, was fixed upon him who stood at the iron railing encircling the chief's desk.

He was not over sixteen years of age, of medium size, poorly clad, and evidently used to hard work. But his features, though browned with a deep coat of tan and bountifully sprinkled with freckles, made up an honest, manly-looking countenance, while the blue eyes met the railroad superintendent's sterner gaze with an unflinching light.

Everything had seemed to work that day at cross-purposes with Superintendent Lyons, and he was in no humor to parley with the poor boy, who had thrust himself into his presence with more boldness than discretion.

But the very attitude of the youthful applicant, as he stood there with uncovered head, respectfully waiting for his answer, showed he was not to be put off with the ordinary excuse.

General Lyons was so favorably impressed with his appearance of quiet determination that he was fain to ask:

"You say you have come from Woodsville, a hundred miles, for a situation on the road?"

"Yes, sir."

"And that you have recently been discharged from our employ? I must say, your audacity is only equaled by your frankness."

"But, sir, it was no fault of mine. I was trying to do my duty."

"Give me the particulars in as few words as possible."

"Thank you, sir. I have worked on Section 66 nearly two years—"

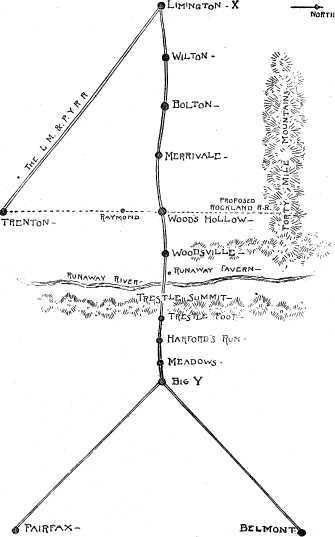

"Let me see," interrupted the superintendent, "that extends from Trestle Summit to Wood's Hollow."

"Yes, sir."

"The most troublesome section on the entire line of the road. But go on with your story."

"It's a bad section, sir, and it usually takes five regular hands to keep it in repair. But for two weeks a couple of the men have been off on account of illness, while our foreman, Mr. Gammon, has not been on duty half of the time. This left one man, with myself, to look after the road. That, with the rains we have been having, has given us more than we could do as it ought to be done. But Mr. Gammon refused to put on any more help, so Mr. Baxter and I have done the best we could.

"Day before yesterday it was after dark when we had finished a repair which had taken us all the afternoon, at Trestle Summit, the extreme upper end of our section.

"The northern mail train was then due, and we were waiting for that to pass, so we could have a clear track to go home, when a man, coming from the direction of Woodsville, told us the bridge, two miles beyond the station, had been washed away. The stranger didn't look like an honest man; and we knew, if he had been, he would told them at the station. But the bridge had been threatened for several days, and, as we had not seen it for thirty-six hours, we knew there was more than an even chance that the tramp was right.

|

"Mr. Gammon had promised to look to it that day; but he so seldom did as he would talk that we did not believe he had been near it. If it was so, every life on the train was in peril, and, as I have said, it was then time for it to come along. "So Mr. Baxter and I decided to signal the train, and tell them of the situation. But it was raining hard then, the wind was blowing furiously, and our matches were damp, so we worked in vain to make a torch. It was too dark for our flag to be seen. We had no way to stop the train. At that moment we heard its whistle in the distance and knew it would soon reach us. "We were on the backbone of Trestle Summit, where, either way, the track descends at a sharp grade for over three miles. It was nearly six miles to Woodsville; but I knew while the mail was climbing the up grade we could get well on toward the station. So I said to Mr. Baxter: |

"'Let's take our hand-car and go on ahead of the train. It's our only chance.'

"We weren't long in getting the car upon the track. But we had barely sprung aboard when the mail head-light burst into sight less than half a mile away!

"'We are too late!' gasped Mr. Baxter; and, whether from fright, excitement or illness, he fell in a swoon.

"The car had started down the grade. Pulling Mr. Baxter on, so he would not fall off, I lent my strength to the car's momentum, and we shot down the track like lightning.

"In my excitement, I had forgotten that it would require my arm to hold in check the speed of the car. In fact, it had been known to get beyond the management of its drivers at one point several times. But I had given it a start, and it wasn't long before it was beyond my control. Then, all I could do was to cling to the platform, expecting every moment to be my last. We went so fast the wheels didn't seem to touch the tracks, only now and then, and we appeared to be flying through the air, going faster and faster.

"Glancing back once, I saw the engine-light as the train thundered over the summit, and at increased speed shot down after us! But we were not likely to be overtaken, going at our flying rate.

"How the hand-car kept the track I do not know; but, before I could realize it, we had reached the valley, crossed Runaway Bridge, and were rushing up the ascent toward the station.

"As we began to lose speed, the train began to gain on us, and I knew the engineer was doing his best to make up for lost time.

"For the last half-mile it looked as though we should be overtaken, but we came in with the cow's nose at our heels.

"I told them what we had done, and as soon as they got over their surprise a party went ahead to examine the bridge."

"Well, what was the result?" asked the superintendent, who had listened with great interest to the boy's thrilling, yet straightforward, account of his hazardous ride. "You took a fearful risk."

"The bridge was not gone, sir, and the train passed over in safety. The tramp had lied to us."

"And you had your dangerous ride for nothing?"

"Yes, sir, unless you could consider a notice to quit work a reward. Mr. Gammon accused Mr. Baxter of being intoxicated, and said we had got caught on the track to tell that story to get out of a bad scrape. I knew it was useless to talk with him, so I have come to you."

"What sort of a job do you want?" asked General Lyons, showing by his tone that he had not been displeased by the boy's story.

"Anything that is honest, sir, and will give me fair wages, with a chance to rise."

"So you have an eye to the future. Perhaps you hope to have the management of a road yourself some time."

"It shall be no fault of mine, sir, if I do not."

"Nobly said, my boy; and it is possible you hope to be superintendent of the Pen Yan."

"I mean to do my best for it, sir." And then, as if frightened by the boldness of his speech, he added, "I only meant to say I am going to do my duty."

"And if you stick to that purpose as faithfully as I think you will, success will at last crown your efforts. I will speak to Mr. Minturn of you and he will doubtless give you a situation. Good-day."

The superintendent turned back to his business problems, and the others in the room followed the example of their chief, disappointed at the sudden termination of the interview.

The boy, however, seemed loth to leave. He started away, went a few steps and paused.

Then coming back to the railing, he said, with less firmness than formerly:

"If you, please, sir, I had rather you would not leave my case in Mr. Minturn's hands."

"So Mr. Minturn knows you?" asked the railroad king, sharply, vexed at this second interruption.

"He does not like me, and he would never give me a situation. I—"

"Well, that is no fault of mine. But I haven't any more time to lose with you."

Seeing it was useless to say more, the boy made his departure, trying to feel hopeful, but fearing the worst.

Scarcely had the youth left the railroad company's headquarters, when a tall, spare man, with faultless dress and cleanly-shaven face, entered the apartment, going straight to the superintendent's desk, smiling and nodding to the clerks as he passed them.

He was Donald Minturn, the assistant superintendent, who had a smile for every one, but as treacherous as the charm of the serpent.

"Hilloa Minturn!" greeted his chief; "you are back sooner than I expected. By-the-way, you must have met a boy as you came in. He was after a situation, and I was careless enough not to ask him his name. Call him back if it is not too late. I think we might do worse than—"

"What!" exclaimed Mr. Minturn, "has that fellow had the audacity to come here for another job? He has been discharged from his section this very week."

"Then you know him, Minturn? Come to think of it, he told me so. How stupid I am to-day! What is his name?"

"That he couldn't have told you himself, if you had asked him, general. He is a sort of waif of the switch-yard. Jack Ingleside—you knew Jack—he was engineer on the old Greyhound, afterwards took to drink and went to the bad—well, as I started to say, Jack found this boy in the caboose one morning as he was starting from Wood's Hollow. He wasn't more than three years old, and how he got there is yet a mystery. Jack took a fancy to him and gave him a home while he lived. I think the young scamp still lives with the widow at Runaway Tavern."

"He seems like a more than commonly smart boy."

"Oh, he can appear well enough when he is a mind to. But Mr. Gammon had to turn him off of his section for downright disobedience of orders. Why, only yesterday he and a man named Baxter jumped on to the hand-car in the very teeth of the northern-bound mail, and came very near wrecking the train, to say nothing of ending their own worthless lives."

"Oh, well, if you know the boy, of course you are more competent to judge of him than I. But I must confess he impressed me very favorably. What news from Draco?"

So the august officials of the great Pen Yan gave no employment to the poor boy who had come so far for a situation, whether he deserved a better fate or not.

Meanwhile, the boy, unconscious that his fate had already been decided upon, hastened to the Fairfax Station, to take the homeward-bound train, which would be due in a few minutes.

The Pen Yan railway system forms upon the map of that part of the country a stupendous letter Y. The Fairfax Fork running north-northwest makes one branch of the arm meeting at the Big Y, as the junction is called—the line of the upper arm, where the two tracks unite in one to reach across a mountainous, often sparsely-settled, country for over three hundred miles. At the time we write it was a single-track road from the Big Y to its terminus.

The boy had to wait but a little while for the accommodation, which was on time, and stepping aboard, he was soon homeward bound. He was absorbed in meditations when he was roused from his rather unpleasant reverie by the voice of the conductor, who had taken a seat near by him to chat a few minutes with a friend.

"It is a strange coincidence, Sam, and it puts me in mind of an adventure I had several years ago, and which came near punching my through ticket."

"An adventure, Henry? Give us the story."

"As soon as we have passed Greenburn. I shall have plenty of leisure then."

Without dreaming how soon he should recall it with startling vividness, our hero, with a boy's interest, listened to the conductor's story:

"Ten years ago I was engineer on the Tehicipa and Los Angeles Road, a branch of the Southern Pacific. Those were troublesome times. What with the guerillas and Indians that infested the country, to say nothing of other dangers, we never knew when we were safe, if we ever were.

"One evening—just about such an evening as this, too—we had barely stopped at a way station when some one rushed up to the train and said Gray Gerardo's band was coming to attack us.

"Gerardo was considered the worst desperado in that lawless country, and knowing we had a lot of the yellow ore on board, I knew the outlaw was after it.

"The conductor cut our stop short, but before I could get under way the outlaws were upon us. From their sounds one would have thought all the fiends from the lower world had been let loose.

"The boys fought like tigers, and it was a wild scene for a few minutes. My fireman—a plucky little fellow he was, too—was snatched from my very side, and with a volley of shot whistling about my head, I was pulled from the cab.

"The wheels had begun to revolve and the train was moving on. Struggling desperately with my captors, I succeeded in breaking from them and sprang back upon the engine. Three or four of the outlaws followed me, and among them was Gerardo himself, whom I knew by sight.

"He was a tall, stalwart fellow, with burning black eyes, and a countenance that would have been handsome, had it not been for a long scar under his right jaw. It looked like a sabre-wound, and quite spoiled the beauty of that side of the face.

"Well, knowing it was life or death with me, I pitched one after another of those fellows off the cab, until only Gerardo was left. It surprises me now that I could have done it; but a man never knows his strength until put to the test. Then, you see, being on my own footing gave me an advantage, while some of them, losing their hold on the moving engine, fell off without any assistance of mine.

"I grappled with Gerardo, just as he was boarding the cab and before he could establish his position, I hurled him, heels over head, down the side of the track. At the same moment, however, I heard a sharp report and felt a stinging sensation in my right arm, where the outlaw's bullet had struck me.

"The firing had nearly ceased at the rear of the train, and feeling that in another minute we should be safe, I sprang to the lever and threw the valve wide open. With snorts and shrieks of defiance to our enemies, the old engine obeyed me, soon gaining a rate of speed which I knew would out-distance the baffled outlaws, whose yells I could still hear above the thunder of the train.

"As my excitement abated my arm began to pain me fearfully, and I found the member disabled for further use. My fireman gone, my situation was critical, and I was wondering how the rest of the boys had fared when I heard some one behind me.

"Half expecting to meet one of the outlaws, I turned, and was glad to see one of the brakemen, who had come to my assistance.

"'We have repulsed them, but they are following us,' he said, in reply to my anxious questions.

"'Well, let them follow,' I answered, 'if they think they can overtake my Bonny Bess. Give her more fuel, Ned. You will have to be my—'

"I did not finish my sentence, for at that moment, as we shot around a curve, great tongues of fire leaped from the track ahead of us. It was a bridge in a blaze of flame, and in the light of the burning structure I saw a dozen of Gerardo's band waiting our coming.

"We were going at lightning-like speed, and we were within twenty rods of the fire when I discovered it, so I had no time to hesitate upon my course of action. Quick as a flash I realized the trap Gerardo had laid—our situation. To stop was to throw ourselves into the hands of his followers, which meant death. The bridge was still standing. It might hold us to cross over. There was at least a chance. To stop was hopeless.

"All this seemed to come to me at one thought. I would keep on. Bonny Bess was doing her prettiest and I gave her a free bit; that is, in our parlance, 'linked her up.' My left hand was on the lever and my gaze was fixed on the burning bridge, which hung, a network of fire, over the glowing river, thirty feet below.

"I heard the shouts of the amazed outlaws above the roar of the train, and then I felt the bridge quiver and tremble beneath me, as we were borne over its swaying spans, amid a cloud of ashes, smoke and cinders, which fairly blinded me.

"The blazing girders overhead sent out their forked tongues of fire, and from the timbers below leaped up the sheets of flame until we were enveloped in the fiery shroud. Blinded, stifled for a moment, I then felt the cool night air fan my face, and the engine no longer shook as if upon uncertain footing.

"We had passed the bridge in safety, and I drew a breath of relief. Then another curve in the track brought us into full view of the burning structure, and feeling we were now safe from pursuit, I checked the engine's speed, so we could watch the fire.

"We hadn't watched long before a cloud of sparks flew into the darkness, and one span of the doomed bridge fell into the water. The other must soon follow.

"I felt a dizziness creeping over me then, and the next I knew I was lying on the ground, with an anxious circle of men and women bending over me. You see my arm had been bleeding all of the time, and the loss of blood, with the strain of the awful ordeal, had been too much for me.

"But my arm had been bandaged, and I was soon able to resume my old post, which I did, running the train to Los Angeles without further adventure.

"Strange enough, Gerardo and his followers were not seen after that night. But I had got tired of that country, and I soon after came up this way. I have never regretted it, either.

"But now comes the strange part of my story, and which recalled my adventure so vividly. There is a man on this train who is the exact image of Gerardo!"

"Whew!" exclaimed the other. "Do you really think it is he?"

"I can't say. The likeness is perfect, even to the scar."

"I have heard of cases where two persons looked so much alike you could not tell them apart."

"Very true, and this may be one of them. There is a slight difference here, too, for this man wears side-whiskers. But his beard is not heavy enough to conceal the scar."

"Do you remember where he is going?"

"To Woodsville; and he inquired for Jack Ingleside. Seemed surprised when I told him Jack was dead. Said he was a relative, and he asked all about the family. Here we are at the Big Y. This is as far as I go."

An impatient crowd was waiting at the Big Y station for the northern mail, which was half an hour overdue.

Finally, when the engine thundered into the depot, puffing and panting like an over-driven steed, there was a rush to board the train, as if the time was limited to the shortest possible space.

"It's going to be a rough night," muttered the old engineer, as he peered out of the cab window into the gathering gloom of storm and darkness. "I never felt so uneasy in my life, and I have a presentiment something is going to happen—as if it wasn't enough to be half an hour behind time and your engine in the sulks. But how are you feeling, Gilly?" addressing his fireman. "Any better?"

"No, Jockey; and I am afraid I won't be able to go through. I don't understand it, for I felt well enough when I started."

"I tell you everything is wrong to-night. If Jim were here—Hilloa! there's Jack Ingleside's boy, as true as I live! We're in luck. Hi, Rock! aren't you lost?"

At the sound of the engineer's voice, our hero, who was following leisurely the crowd to one of the cars, looked in that direction to see the soot-begrimed countenance of his old friend.

"Lost, Jockey? Never where you are," replied the youth.

"Going up? Jump in here, then. It won't be like riding in a parlor-car, but it will suit you just as well, I'm thinking."

Rock showed his willingness by springing quickly into the cab.

Railroad companies have a rule forbidding persons to ride with the engineer without permission from the president or superintendent, though at the time we write this matter was not as rigidly looked after as now.

Rock, however, who had passed nearly all his young life on the foot-board, would have been deemed an exception to any rule. At least, so thought Jockey Playfair, the veteran "knight of the lever" on the Pen Yan mail and accommodation.

But Jockey's usual good-humor had been relegated to the background on that evening, as Rock soon saw.

The signal to start was given, and with a full head of steam on, the old engine, trembling and groaning from her pent-up power, began to creep ahead, as if feeling her way along the switches and through the yard, going faster and faster at every revolution of her wheels, until the station-lights faded in the distance, and she plowed boldly into the night.

The tall form of the engineer, clothed in greasy overalls and jumper, stood at his post like a grim sentinel on duty, his right hand on the reversing lever, his left on the throttle, while his steely gray eyes peered into the gloom, as if expecting to see spring from the regions of darkness the hosts of danger and death.

A drizzling rain was falling, so altogether it was a disagreeable night.

"I have a favor to ask of you, Rock," said Gilly, the fireman, as the engine fairly gained her feet and increased her progress at every beat of her piston heart. "I want you to take my place until we get to Trestle Foot. I am used up."

"Of course I will," replied Rock, taking the fireman's place. "Is she very hungry to-night?"

"Hungry and cross, Rock," said the other. "But I'll risk you to feed her."

No engineer who has stood at the lever for any length of time refuses to believe that his trusty servant is without her faults, however he may care for her. She is subject to her ill-moods as well as himself.

The engine, so good-natured on his last run, so prompt to obey his will, on this trip is stubborn and hard to manage.

He can see no reason for her change of spirit. Her wonderful mechanism is in perfect working order, her groom has arrayed her for a dazzling passage, her fireman has fed her with the best of fuel, the flames dart ardently along her brazen veins, she bounds off like a charger, eager for conquest. Her first spurt over, she falters, sulks.

No coaxing can change her mood. In vain her master bestows greatest care upon her; with each effort she grows more sullen.

Jockey Playfair's engine was in the sulks on the trip of which we write. The Silver Swan had never seemed in better temper than at the start. Delays in making connections, the bad condition of the track at places on account of the recent heavy rains, with other difficulties, had caused them to lose time. The engineer, however, had confidently expected to make up for this before reaching Wood's Hollow, sixty miles above the Big Y junction.

In the midst of his anxiety his fireman was taken suddenly ill. Then his engine began to fail him. This last gave him more uneasiness than all the rest.

"Behind time, with a sulky engine and a sick fireman!" he muttered, to himself. "I see it coming—something dreadful! Never mind, old Jockey! You are on your through trip to-night, but stand to your post like a man."

During the next ten miles nothing was said by the three, and then, as they stopped long enough at a way-station to take on a solitary passenger, Jockey merely remarked:

"One minute gained. If we can't do better than that on our next run I'll never touch the lever again."

As Jockey knew, he was now on the most favorable section of the road. No signals were to be expected for a long distance, and there was no reason why he should not regain a good part of the lost time. If he didn't he resolved it should be no fault of his.

As soon as he was fairly under way again, he "linked her up." That means he drew the reversing-rod back until the catch held it near the centre, so the steam, instead of being allowed to follow the length of the piston-rod, beat alternately the heads of the cylinders, giving the highest momentum acquired.

Rock understood his duty perfectly and was determined the Silver Swan should not hunger for fuel under his care.

"Mind how well the boy fires," said Gilly, forgetting for a moment his pain.

"So he should; for wasn't he Tommy Green's pupil? And Tommy was the best fireman ever on the Pen Yan, not even excepting you, Gilly."

"I know it; but she is pulling for all she is worth now, Jockey. You'll get there on time, after all."

The Silver Swan was behaving beautifully now. Apparently she had gotten over her sulks. Nothing occurred to disturb the even tenor of their progress until the lights of Haford's Run came into sight.

At this place they must stop to refill the engine's boiler, and while Rock looked after this matter, Jockey carefully examined each part of the wonderful machine, talking to it and patting it as he would a child.

When he had run his practiced eye over the bars, joints, connecting-rods, cylinders and steam-chests, then around the pilot to the other side to find everything in fine working order, he came back to the cab-step and consulted his watch.

"Ten minutes gained," he murmured, exultantly. "If you hold out like this, old Swan, we'll make Wood's Hollow on time."

"Good! So you will, Jockey!" exclaimed the conductor, coming forward with his lantern. "You have an excellent run ahead of you; do the best you can. If we can gain ten minutes before getting to Trestle Foot, we'll venture to Woodsville. Are you ready?"

"All ready," answered Rock, who had shut off the flow of water and flung back the dangling leather arm to spring from the tender to the footboard.

"Ho!" called out the conductor, "who's firing to-night?" as Rock, jerking open the furnace door, stood in the glow of the fiery light. "Where's Gilly?"

"Here; but he's sick," answered Jockey. "Rock took his place at the Big Y."

"What! Jack's boy? Well, he is good for it. If Gilly is sick he had better come back into a passenger."

But the old fireman wouldn't think of deserting his post so far as that.

The next instant the conductor's lantern waved back and forth, dense volumes of smoke rolled from the smoke-stack, and snorting as if with rage at being driven on again, the engine forged on along its iron pathway.

"Where have you been to-day, Rock?" asked the engineer, as they were once more spinning along at a flying rate.

"Down to Fairfax to see if I could get a job. You know I got turned off the section."

"No—you don't mean it! I'll bet Gammon was at the bottom of it."

"I am sure of it. He has boasted I shouldn't stay there long."

"Zounds! I'd like to shake the rascal out of his jacket. He's been wanting Gilly's place; but he can't get it. What do you want?"

"To brake."

"Get it?"

"Nothing certain. I have little hope, for Donald Minturn will never let me get there if be can help it."

"The old snake! I never did like him. So he isn't over fond of you?"

"No; he is opposed to me on account of an old enmity he bears Mrs. Ingleside."

"Rock, you deserve a place on this road. Why, bless you, you are fit to take my place. Not many trips did old Jack make without taking you with him. I used to fire for him, you know. He had a mat for you at his feet, and when too tired to keep awake longer you slept curled up on the footboard. Ah, it was something such a night as this when poor Jack made his last trip! It wasn't quite so dark it may be, but he was behind time, as we are, and he was trying to make up.

"He was swinging down the long grade beyond Woodsville at a humming rate. There was no station at the Hollow then, and he was counting on a clean sweep to Owls' Nest. Leaving the air-line grade he swooped around the curve, when right in his face and eyes he saw a string of loose cars, which had broken from the special on the highlands.

"He must have been going at the rate of fifty miles an hour, and the runaways were coming toward him at scarcely less speed. I caught a gleam of his white face as he reversed, and then he was beside me at the brake.

"'Stand by!' he cried. 'We'll die at our post.'

"The shock came the next moment. I felt myself lifted into the air, and the next I knew I was lying at the foot of the embankment, a dozen yards from the place where we had met.

"Jack died at his post, and his sufferings could not have lasted long, for he was crushed beyond recognition. Fortunately no other lives were lost, though the passengers were terribly shaken up, and two of the freight cars were piled up on the engine.

"Jack's fidelity, I am sure, averted a worse catastrophe. He met the fate of a hero, and it was always a mystery to me the company never did more for his family.

"Hey! As I live, the Swan is falling into another ugly mood!"

They were rushing along at a tremendous rate, and an inexperienced eye would have seen nothing amiss.

In fact, the engineer himself could not. The driving-rods were shooting back and forth in perfect play, while the large drivers were revolving with clock-like regularity. Every now and then Jockey would give the lever a slight pressure, which would be instantly felt by the iron steed.

Despite all this the Silver Swan was not doing as well as she ought. She was barely keeping her course at the usual speed.

Jockey glanced to the boiler. The index finger pointed to the gauge at 122 degrees. Three more degrees was all she could stand. Rock was doing his duty. The track was straight and level. Still the Swan showed no disposition to gain the twenty minutes coveted time.

The old engineer shook his grizzled head and the furrows deepened on his careworn visage.

"The fates are against us to-night," he muttered. "We can never make Wood's Hollow in time to escape the down express. That is always on time."

Just then the little gong over his head sounded, in response to the conductor's pull upon the cord.

Jockey quickly answered this with a blast from the whistle, which the other would understand to mean that the engine was already crowded to her utmost.

The old engineer was losing his temper by this time, and with his hand still on the lever he leaned forward to peer into the gloom, parting before the dull rays of the headlight, as if to let them pass.

A drizzling rain was yet falling, but he did not notice this, for at his first glance a cry of horror left his lips, and he staggered back, exclaiming:

"It is coming! Someone has blundered!"

Rock started forward with surprise, and he uttered a cry of terror as he saw the gleam of a headlight and the shadowy outlines of an engine and train, less than a rod in front of them.

It is a safe assertion to make that every girl has at some time or other played with dolls; in fact, it is almost impossible to imagine a girl without a doll. Of course, the older ones have outgrown their dolls, and only keep the old favorites as souvenirs of childish days and pretty playthings, and it is quite likely that they would be puzzled to explain why they call the little image a "doll," and not, as the French do, a "puppet," or, with the Italians, a "bambino," or baby.

What is the meaning of the word "doll?" To explain, it is necessary to go back to the Middle Ages, when it was the fashion all over the Christian world for mothers to give their little children the name of a patron saint. Some saints were more popular than others, and St. Dorothea was at one period more popular than all.

Dorothea, or Dorothy, as the English have it, means a "gift from God." But Dorothea or Dorothy is much too long a name for a little, toddling baby, and so it was shortened to Dolly and Doll, and from giving the babies a nickname it was an easy step to give the name to the little images of which the babies were so fond.

In this age of enlightenment it is not often that one meets with an adult who cannot read and write, and the encounter is generally as amusing as it is amazing. In one of the interior towns of Pennsylvania there lives a farmer who brings butter, eggs and produce to market, and, being illiterate, also brings with him his son to do the "figuring." The other day the son was ill, and the old man had to venture alone. For awhile he got along very well by letting his customers do the figuring; but presently he sold two rolls of butter to a woman who could not figure any better than he. The farmer was much puzzled, but, being resolved that she should not know that his early education had been neglected, he took a scrap of paper from his pocket and began. He put down a lot of marks on the paper, and then said, "Let's see; dot's a dot, figure's a figure, two from one and none remains, with three to carry—$1.50, madam, please." She paid over the $1.50, took the butter home, had it weighed and "figured up" by her daughter, who discovered that the price should have been $2.10 instead of $1.50.

A small Detroit boy was given a drum for a Christmas present, and was beating it vociferously on the sidewalk, when a nervous neighbor appeared, and asked, "How much did your father pay for that drum, my little man?" "Twenty-five cents, sir," was the reply. "Will you take a dollar for it?" "Oh, yes, sir," said the boy, eagerly. "Ma said she hoped I'd sell it for ten cents." The exchange was made, and the drum put where it wouldn't make any more noise, and the nervous man chuckled over his stratagem. But, to his horror, when he got home that night there were four drums beating in front of his house, and as he made his appearance, the leader stepped up and said, cheerfully, "These are my cousins, sir. I took that dollar and bought four new drums. Do you want to give us four dollars for them?" The nervous neighbor rushed into the house in despair, and the drum corps is doubtless beating yet in front of his house.

Photography is an art that looks to be easier than it is, but some beginners add to their difficulties by inexcusable carelessness. A young lady bought a Kodak at a dealer's before she went on her summer vacation, and was so confident of her own ability that she took only the book of directions and went off. She took seventy or eighty shots in picturesque places, and promised copies to all her friends. When she came home, she left the camera to have the film developed and printed. The artist developed on and on, but found none but blanks. In great surprise, he sent for the amateur photographer, and when she came he asked, "How did you operate this camera?" "Operate it? Why, I pulled the string as the book says, and touched the button." "But what did you do with this little black cap here?" "Why, I didn't do anything with it," she replied. And then the artist roared with laughter. She had never once removed the cap that covered the lens, and had, of course, taken not a single picture, and when she found what she had done, or rather not done, she wept bitter tears.

One of the most amusing accidents imaginable happened recently to an old gentleman in one of our large Eastern cities. He was asked to buy a ticket to a fireman's ball and good-naturedly complied. The next question was what to do with it. He had two servants, either one of whom would be glad to use it, but he did not wish to show favoritism. Then it occurred to him that he might buy another ticket and give both his servants a pleasure. Not knowing where the tickets were sold, he inquired of a policeman, and the officer suggested that he go to the engine house. So the old gentleman went to the engine house that evening, but there was no one in sight. He had never been in such a place before, and stood for a moment or so uncertain how to make his presence known. Presently he saw an electric button on the side of the room, and he put his thumb on it. The effect was electrical in every sense of the word. Through the ceiling, down the stairs and from every other direction firemen came running and falling, the horses rushed out of their stalls, and, in short, all the machinery of a modern engine house was instantly in motion. Amid all this uproar stood the innocent old gentleman, who did not suspect that he had touched the fire-alarm until the men clamored around him for information as to the locality of the fire. Then he said, mildly, "I should like to buy another ticket for the ball, if you please." The situation was so ludicrous that there was a general shout of laughter, and the old gentleman bought his ticket and the engine house resumed its former state of quiet.

|

A Happy New Year, and a new beginning

For hands that have wavered and steps that fall;

New time for toil and new space for winning

The guerdon of happiness free to all.

Now hope for the souls long clouded over

With possible sorrows and actual pain;

New joys for comrade, and friend and lover,

The year is bringing them all again!

New days and hours for the patient building

Of noble character, pure and true;

For faith and love, with their radiant gliding,

To make the temple of life anew.

A Happy New Year, and a truce to sadness,

Its every moment by God is planned;

Whatever may come, whether grief or gladness,

Must come aright from a Father's hand.

He blessed the old in its dawning—thenceforth

His love was true to us all the way,

And now in the hitherto shines the henceforth,

And out of the yesterdays smiles to-day.

We would have power In this year to brighten

Each lot less blessed and fair than ours;

The woe to heal, and the load to lighten,

The waste soul-garden to plant with flowers.

May every day be a royal possession

To high-born purpose and steadfast aim,

And every hour in its swift progression

Make life more worthy than when it came. |

If you simply desire to get a picture from your negative in the easiest and quickest way, without going through the necessary processes which are involved in toning, you can use cyanotype paper, which requires but one process for the completion of the picture and that process simply a bath in clean water.

Prints made upon this cyanotype paper have a beautiful blue tone, and are so simple and easily made that they are very popular. This cyanotype paper is sold in any desired quantity and size, and it is never worth while for the amateur to prepare his own paper, as it is a tedious and uncertain process.

When you are sure the negative is thoroughly dry, place it in the printing frame with the film side uppermost, and upon it lay a sheet of the cyanotype paper cut the right size, with the prepared side next to the film of the negative.

The frame should then be put where the sun's rays will fall upon the glass, and allowed to remain there till the cyanotype paper has turned to a dull bronze in the shadows.

It will be necessary to look at the print from time to time to see when this point is reached. If the paper is not allowed to print long enough, the result will be that the picture will wash off the paper when it is put in water.

When you think it is done, place it in running water, or in several changes of water, and wash it thoroughly. It should be washed till the water that drips from it is no longer discolored, but is perfectly clear. The picture then should stand out in blue tones on a clear white ground.

If you prefer to use the ready sensitized paper, there is a preliminary process through which the paper must pass before you print it. This process is called "fuming," and consists in exposing the paper to the fumes of ammonia for a short time.

A fuming-box is needful, but one can easily be constructed, without the expense of purchasing this convenience. Take a wooden box about two feet cube, and, with hinges, make a door of the cover. Close all the cracks with strips of cloth so that the box will be both light and air tight, and fasten corresponding strips around the edges of the door so that no light will make its way in there.

Stretch two or three strings across the box near the top, on which to hang the paper that is to be fumed, and put a small flat dish in the bottom of the box.

When you are ready to fume your paper, pin two sheets together, back to back, and hang them on one of the strings. Several sheets can be fumed at once in this manner. Fill the dish with ammonia, and closing the door tightly, let the paper absorb the fumes for fifteen or twenty minutes.

After fuming, the paper should be given a short time to dry before it is used for printing. It should then be put in the printing frame in the same way as the cyanotype paper and exposed to the sun.

If your negative is a thin one, a diffused light is better for printing than the direct rays of the sun. Diffused light is a strong light that is not sunlight.

If the negative is exceedingly thin, the light indoors, away from the window, will be sufficient. Satisfactory results cannot of course be achieved with too thin a negative, but this diffused light will give the best print that you can obtain.

In examining the print from time to time be sure that you do not open both sides of the printing frame at once, for if you should do this, you will find it impossible to replace the print in exactly the same position, and so it will be spoiled by being printed with double lines.

No exact rule can be given for the length of time which should be allowed for the printing of a negative. It should, however, be allowed to become twice as dark as it ought to be after the picture is toned and mounted. The after processes of toning bleach the print very much, as the amateur will discover for himself.

If a negative is very dense or thick, as over-development will sometimes cause it to become, the time for printing will be considerably extended. While in a good light, with a negative of the right density, five minutes or less is sufficient to print a negative, three or four hours will sometimes be required.

When the print has become dark enough, it should be removed from the printing frame and put at once in a dark place where the light cannot reach it. It is what is known as a proof at this stage, and the light will turn it black.

About twenty prints can be toned at once, and, as it is a long process, it is better to wait until several have accumulated than to go through the various operations with only one or two prints.

They should first be trimmed to the required size. Some amateurs leave the trimming until after they have finished the toning process, but this is not advisable for several reasons. In the first place, it is easier to trim them beforehand, because they lie flat and are not curled up, as they generally are after toning. None of the toning solution is wasted in toning the parts that are of no use, and if the accumulated clippings are saved, they are of some value on account of the silver in them.

The trimming cannot be satisfactorily done with a pair of scissors, as it is impossible to cut perfectly straight. A thick piece of glass called a cutting mould is used, and a convenient little instrument called Robinson's trimmer. If you do not wish to go to the expense of these articles, however, you can manage very well by using a sharp pen-knife to cut with and any piece of glass with straight edges to trim by.

You should have a firm, hard substance to cut on (glass is preferable), and on this should be put a piece of paper. Upon this paper the print should be laid face downward, and after you have decided how much of it you are going to cut away, draw your knife firmly along by the edge of the glass, pressing down well, and the strips will be cut off leaving a smooth, straight edge.

After the prints have been trimmed, they should be soaked in water for fifteen minutes. If you have not running water in which to place them, the water should be changed several times. This preliminary washing must be very thorough, or the toning will not be satisfactory.

To prepare your toning bath, make up first a stock solution of fifteen ounces of water and fifteen grains of chloride of gold and sodium. The chloride of gold and sodium can be obtained in small bottles which come for the convenience of the amateur prepared in just the desired quantity.

For a toning bath for twenty prints, take ten ounces of water, three grains of sodic bicarbonate, six grains of sodic chloride (common salt), and three ounces of your stock solution of gold. Add to this bath three ounces of the stock solution of gold that has had three drops of saturated solution of bicarbonate of soda added to it. This bath should be alkaline, and you can test it with red litmus paper. If it turns the paper slightly blue, it is ready for use. Put this bath in a flat tray (porcelain preferably), and then lay the prints in it face down. Move them all the time, to insure evenness of tone and to prevent spots. It is a good plan to keep drawing out the undermost one, and putting it on the top.

The prints are of a reddish-brown color when they are put into the toning bath, and in about fifteen or twenty minutes they begin to turn to a rich purplish black. Experience will teach the amateur at what point the prints should be removed from this bath. They should lie long enough to have every tinge of red entirely removed, and yet not long enough to turn the prints to a dull gray.

When the prints have been sufficiently toned, they should be thoroughly washed and then put into the fixing bath. This bath is made of one gallon of water, one pound of sodic hyposulphite, one tablespoonful sodic bicarbonate, and one tablespoonful common salt.

These ingredients should be thoroughly dissolved, and then a portion put in a tray. This tray must be kept for the fixing bath and not be used for any other purpose. The prints are put in the tray in the same manner as in the toning bath, and moved continually until they are fixed.

This process should take fifteen minutes, or, if the bath is rather cool, the time may be extended to twenty minutes.

After the prints have been removed from the fixing bath they are put in a strong solution of salt and water, to prevent their blistering. After they have been in this solution for about five minutes they are then ready for their final washing. The prints should be left in running water for some hours, and there is very little danger of washing them too long or too thoroughly.

After every trace of the fixing bath has been removed, the prints may be taken from the water and dried between sheets of chemically-pure blotting paper. They will not curl up when dried in this way, as they do when simply exposed to the air.

The prints are now ready to mount. This is by no means the least difficult nor the least important of the many processes necessary to secure a successful picture. Even if care has been exercised in all the other processes, yet if the prints are carelessly mounted they will not look well.

The prints should be wet in clean water and laid in a pile upon each other, with their faces down. It is necessary to have a very adhesive paste to make the prints stick well to the mounts. There are some pastes that are manufactured for this purpose, but it is very easy to make one which will work equally well.

Boiled laundry starch, with the addition of a little white glue, is perhaps the best; it can be easily made, and with the addition of a few drops of carbolic acid will keep well. It is made in the proportion of one and three-quarter ounces of starch, mixed with one ounce of water, till it is a smooth paste, as thin as cream, and eighty grains of glue added with fourteen ounces of water. The whole should be well boiled and six drops of carbolic acid added. This can be put in a bottle and will keep a long time.

After the water is pressed from the wet prints a bristle brush is dipped in the paste and drawn back and forth over the print, till it is thoroughly covered.

The position on the mount should have been previously marked with a pencil or with pin-pricks, and when the print is well covered with paste it should be carefully lifted and put in place. With a piece of paper laid over it and a flat paper-cutter, all the unnecessary paste and any bubbles of air may be pressed out from between the print and the mount. With a soft cloth wipe away the paste that is pressed out around the edges of the print and then put it under a weight to dry.

If it is desired to mount prints in an album, a piece of cardboard, an eighth of an inch smaller than the print, should be placed upon the back of the print and the exposed edge covered with paste. Put on just as little as possible and lift it in place at once, before the paste has time to dry. Pass a soft cloth over it to press it into place and then close the album. In less than an hour it will be dry, and if properly mounted will be firmly adhering to the page.

The one important factor for success in photography is care. Without it, you can accomplish nothing, no matter how complete and costly your outfit may be. With care and patience you may achieve results that will be a pleasure to your friends as well as yourself, and will give permanent existence to pleasant scenes and occasions that otherwise must be only memory pictures.

Elizabeth Brightwen describes, in "Nature Notes," her method of collecting birds' feathers, by grouping them artistically in the page of a large album.

"The book," she says, "should be a blank album of about fifty pages, eleven inches wide by sixteen, so as to make an upright page, which will take in long tail feathers. Cartridge paper of various pale tints is best, as one can choose the ground that will best set off the colors of the feathers. Every other page may be white, and about three black sheets will be useful for swan, albatross and other white-plumaged birds.

"The only working tools required are sharp scissors and a razor, some very thick, strong gum arabic, a little water and a duster, in case of fingers becoming sticky.

"Each page is to receive the feathers of only one bird; then they are sure to harmonize, however you may combine them.

"A common wood-pigeon is an easy bird to begin with, and readily obtained at any poulterer's. Draw out the tail feathers and place them quite flat in some paper till required. Do the same with the right wing and the left, keeping each separate and putting a mark on the papers that you may know which each contains.

"The back, the breast, the fluffy feathers beneath, all should be neatly folded in paper and marked; and this can be done in the evening or at odd times, but placing the feathers on the pages ought to be daylight work, that the colors may be studied. Now open the tail-feather packet, and with the razor carefully pare away the quill at the back of each feather.

"This requires much practice, but at last it is quickly done, and only the soft web is left, which will be perfectly flat when gummed upon the page. When all the packets are thus prepared (it is only the quill feathers that require the razor) then we may begin.

"I will describe a specimen page, but the arrangement can be varied endlessly, and therein lies one of the charms of the work. One never does two pages alike—there is such scope for taste and ingenuity—and it becomes at last a most fascinating occupation.

"Toward the top of the page, place a thin streak of gum, lay upon it a tail feather (the quill end downward), and put one on either side. The best feathers of one wing may be put down, one after the other, till one has sufficiently covered the page; then the other wing feathers may be placed down the other side; the centre may be filled in with the fluffy feathers, and the bottom can be finished off with some breast feathers neatly placed so as to cover all quill ends.

"When one works with small plumage, a wreath looks very pretty, or a curved spray beginning at the top with the very smallest feathers and gradually increasing in size to the bottom of the page.

"Butterflies or moths made of tiny feathers add much to the effect, and they are made thus. It is best, I find, to fill a wide-mouthed bottle with dry gum, and just cover the gum with the water, allow it to melt, keep stirring and adding a few drops of water till just right—no bought liquid gum equals one's own preparation.

"To make the book complete, there should be a careful water-color study of the bird on the opposite page, its Latin and English name, and a drawing of the egg. It may interest some to know how I obtained the ninety-one birds which fill my books. Some were the dried skins of foreign birds, either given me by kind friends or purchased at bird-stuffers'. The woodpecker and nut-hatch were picked up dead in the garden. The dove and budgerigars were moulted feathers saved up until there were sufficient to make a page.

"Years after the death of our favorite parrot, I found that his wings had been preserved; so they appear as a memento of an old friend who lived as a cheery presence in my childhood's home for thirty years. It is a pleasure to me to be able to say no bird was ever killed to enrich my books."

"Oh, what a lonesome day it will be!" sighed Lilian, looking wistfully out across the snow-bright prairie.

"Not unless you make it so," responded her mother, cheerily.

"Make it so!" rejoined Lilian. "How can I make it anything else? It is always lonesome here, and to-day will be the worst of all. Only think of the fun the girls will be having in dear old Deerfield, while I am off out here in this—"

She stopped short, fearing she might say too much. What she had been about to say was "this horrid, desolate Kansas ranch."

"Perhaps the boys can take you for a drive, dear; and you know we're invited to Uncle Abner's for the evening."

"A drive!" replied Lilian, scornfully. "I hate driving, all alone, along these endless roads. Nothing but snow, snow, until I am nearly blind."

"You have your books, Lilian; and your father likes perfect lessons."

"Yes, I can have books any day. But think of the girls at home—what they are having. They are getting their tables ready, this very minute. They will darken the parlors and have gas-light, and pretty dresses and lots of callers."

Here Lilian broke down and sobbed. Her mother came to her side and stroked her hair.

"Be brave, daughter," she whispered. "I know it is a great change. But I have often told you we must bear in mind why we left the East, and why we are here. Father would not have been alive but for this change of climate and open-air life. You know he is getting well, and is so happy in that. We ought not to mind anything if he can be well again."

Lilian felt ashamed, and tried to dry her tears. Yet she was unwilling to quite give up her discontent.

"If only something would happen!" she said. Then, desperately, "I wish there would be a cyclone or a blizzard, or a prairie fire! I wish the Indians would make a raid!"

"We don't have cyclones and prairie fires in winter," her mother said, calmly.

Just then Lilian heard a great stamping of feet and gay voices outside on the kitchen threshold.

Her four brothers were coming in from doing their morning chores. As they entered they let in a great rush of cold air. Jack spied Lilian through the half-open sitting room door.

"Hello, Lil!" he called.

She did not answer.

"Lil in the dumps again?" he asked his mother.

"She is a little homesick this morning."

"Why doesn't she get out, as we do, and stir up her spirits?" said Harry. "It's nothing but moping makes her homesick."

"This is a thousand times better than poky old Deerfield," asserted Ben. "There was nothing to do there but slide down hill on a hand-sled, and here we have the ponies, and the cattle, and—"

"But you are a boy, Ben," interposed Mrs. Wyman, "and can do a great variety of things. Lilian isn't strong enough for hard riding, and, besides, she misses her friends."

"Let her make new ones," piped up Jamie. "There's lots of nice people all over these prairies."

"She will find them in time," said Mrs. Wyman. "But you must cheer her all you can meanwhile."

Lilian overheard herself discussed, and began to sob afresh.

Jack went into the sitting-room and playfully pulled her ears, and tried to laugh her out of her gloom.

"Come now, Lil. What is it you want—a gallop, a sleigh-ride?"

Lilian could confess anything to Jack.

She told him all that had been in her thoughts—how the Deerfield girls were getting ready for callers, what pretty dresses they would have, and what gay, good times.

"Do you want callers? Is that what you want, Lilian?"

"Oh, you stupid fellow! I want anything except this awful experience. I told mother I even wished the Indians would drop down on us."

"Why, Lilian, if you saw even one Indian coming down the road, you'd run and hide under the bed."

"No, indeed I wouldn't. I'd make my very best courtesy and wish him a Happy New Year. I would spread the table with the rose-bud china, make coffee for him, and—"

"Y-e-s—but before you'd half done, he would whip out his tomahawk, grasp you by the hair—this way—and, w-h-o-o-p! off would come your scalp. Then he'd tuck your braids into his belt, and away he'd go to the reservation to hang them up on the ridge-pole of his wigwam!"

"All the same, I wish he'd come."

Jack laughed.

"Say, Ben," he called, "Sis wants visitors so badly, she even wishes a Comanche would call."

"I do," persisted Lilian. "I wish a whole tribe would come!"

Harry stormed into the sitting-room, in search of his heavy leather gloves.

"Where are you going, Harry?" asked Lilian, eagerly.

"Out on business," he answered. "Are you ready, Jack?"

"Are you all going off?" cried Lilian, in alarm, lest she should lose even the doubtful pleasure of her brothers' company.

"We're going on the ponies, to look up some stray cattle for Uncle Abner."

"But mamma said you would take me for a drive?"

"Can't this morning—too busy!"

"We're all to go this evening, you know," comforted Jamie.

"This evening! What am I to do alone all day?"

A flood of tears again threatened.

"Oh, entertain your callers!" said Harry, with scant sympathy.

Lilian watched the four boys on their ponies go down the poplar-lined lane to the highway, and then, too desperate for reading or study, or even helping her mother, she flung herself on a sofa and hid her face.

The day was a dazzling one. The rolling prairie on every side looked like a white ocean, with great, sweeping billows of snow as far as eye could see.

The widely separated farm-houses, with their wind-breaks of Lombardy poplars and interspersing clusters of evergreens, looked like ships on this endless, shining, cold sea.

One needed a happy heart and busy hands not to be affected by the vastness and isolation.

Neither of these did Lilian have, and it took her nearly the entire forenoon to get through her bitter struggle with self.

When she finally roused herself she found her mother had put the rooms to rights, and besides her own work, had done all the little tasks Lilian had been used to assume.

This made her remorseful. She got her books and began to study. But somehow the brilliant sunshine kept drawing her to the window to look out.

The sky was of an intense blue that was almost purple. The blue-jays were flitting and calling. A few stray crows hovered over a distant corn-stubble—these were all the signs of life she saw.

She stood tapping a tune on the window panes. Presently she noticed, on the far crest of one of the snow billows, some moving black figures.

They were mere specks against the intense blue beyond, but they fixed her attention. Almost as soon as she saw them, however, they disappeared in an intervening valley.

"That is on the Hardin road," she said, trying to fix the direction. "It can't be the boys, for Uncle Abner's road is to the south."

|

Almost immediately her curiosity was stimulated again by the re-appearance of the figures on the next rise. She could not distinguish numbers, but she felt certain it was horsemen. |

Again they vanished from the crest into the lower-lying space between the land-billows. And so she watched them until they were near enough for her to see it was indeed horsemen.

"Mother," she called, "come here! There's somebody coming along the Hardin road."

Her mother came.

"Who can it be?"

"One, two, three, four, five, six, seven," counted Lilian. "There are seven of them! Perhaps they will turn at the Climbing Hill Corners. They can't be coming here."

"Get the glass," said Mrs. Wyman. "See if we can make them out before they strike the valley."

Lilian ran after the glass. She adjusted it and raised it to her eyes. She had only one glimpse, however, before the descending riders were again hidden by an intervening ridge.

"They ride so wildly, mother!" she said, in a kind of breathless wonder.

"They must be skirting that hill along the creek," said Mrs. Wyman. "We'll see in a minute if they come up from the Corners."

It seemed a long time before they came again in sight. Lilian had just said, "They've turned on the Climbing Hill road," when they burst into full view on a not-distant summit and halted.

Lilian could distinctly see them pointing, as if discussing the way to take. Then, of one accord, they put spurs to their ponies and came wildly dashing down the slope.

Lilian turned deadly pale.

"Mother," she gasped, "they are Indians!"

Mrs. Wyman grew pale also. During her short life in the West she had seen only one or two isolated Indians, and those always at railway stations—dull, commonplace creatures enough, and with nothing suggestive of the warrior about them.

"Where is your father?" she asked, with something of a tremor in her voice.

"Probably over at the sheep-sheds," faltered Lilian. "He's always there near noon. I wish—I wish the boys were here."

"They'll be coming directly. Look again now, Lilian. They are approaching very fast."

Indeed the Indians were coming on fast. They were now in plain sight on the long incline and were riding at a full gallop, gesticulating and pressing forward with what looked to Lilian like savage fierceness.

"They will go by no doubt," said Mrs. Wyman, her native courage reasserting itself. "They are probably out in search of lost ponies or—"

"Look, mother! See! They are not going by. They have halted, and are pointing to the house. See! They are turning in at the lane. Oh, mother!"

"Never mind, dear. They want to inquire, perhaps—"

But while she was speaking, the Indians had wheeled into the gateway and swept up with a headlong pace to the very door.

They swung themselves from their saddles, tethered their ponies to the hitching rails and came quickly up on the porch.

Mrs. Wyman had thrown off her momentary fear. She stepped to the door and opened it. Lilian trembled in every muscle. The leader of the party was a huge fellow, much taller than his followers. He was more fantastic in his dress, too, and had streaks of paint on his cheeks. The rest had turkey feathers stuck into the bands of their slouch hats, and all had blankets over their shoulders.

The chief uttered a surly "How!" and made a motion of his hand to his mouth that he would like something to eat.

Mrs. Wyman smiled cordially, and said, "Come in."

He obeyed directly, the rest stalking after him in perfect silence. They went at once through the sitting-room to the kitchen stove and held out their hands to warm.

This done, they squatted on the floor, with various low guttural sounds to each other, as if exchanging views. They apparently approved of the comfort, for a stolid silence ensued.

Lilian was absolutely spellbound with terror and could not move. Mrs. Wyman went to the pantry to prepare them food.

The chief was restless. He kept his eyes roving over everything. Finally he began to move about.

He went into the sitting-room. He spied the china closet door and opened it.

"Ugh!" he said, as if in delight at the pretty dishes. He waved his hand at Lilian and pointed to the rosebud china, making an imperative gesture, as if to say, "We want to eat off those."

Lilian, anxious to seem to want to please these terrible visitors, nodded and smiled a ghastly smile. The very fact that she must do something seemed to relieve the spell of cold horror that had settled on her.

She took a fresh cloth from a drawer, and spread it deftly on the table. As she straightened the corners daintily, to see if they were quite even, the Indian grumbled his approval.

She took out the dishes and set seven places. She recalled, with a great thump of her heart, what Jack had said about scalping, but as yet there had been no warlike demonstrations.

She began to be more at ease. But what was that uneasy chief doing? He was prying into everything. Lilian distinctly saw him put her scissors into his pocket. But she dared not protest.

While thus distracted, she heard her mother in the kitchen burst into a merry laugh. She ran hastily out to see what had come over her.

Mrs. Wyman was in the pantry, holding a corner of her apron over her mouth, as if to smother her amusement.

There sat the six Indians on the floor, with hats drawn down surlily over their faces, and with blankets shrugged about their shoulders. "Mother, what is it?" was Lilian's whispered inquiry.

Mrs. Wyman pointed silently at the ludicrous row of savages, and covered her lips again with her apron.

Lilian could not help laughing, too.

"New Year's callers, after all," she said, to herself.

Mrs. Wyman had made the circle of waiting braves move somewhat away from the stove, so that she could cook ham and warm potatoes. Lilian returned to her table-setting. She placed a spoon-holder on the cloth, full of bright tea-spoons.

The inquisitive chief gave a genuine whoop of delight at sight of them. He sprang to her side and openly began putting them in his pocket.

This was too much. Lilian flew at him and tried to snatch them away from him. He scowled fiercely, and jabbered at her in excited gutturals.

At once she heard a great scuffling of feet in the kitchen. The other Indians, attracted by the sound, were coming to his rescue.

In they filed in formidable line.

"He shan't have them!" cried Lilian, struggling to prevent the last instalment going into his pocket. "He has my thimble and scissors already. Here," to the others, "your chief is stealing. But he can't have my spoons. You—" catching hold of the nearest one— "Jack! Ben! Harry!" (for as soon as she got one good look at the faces of her callers she knew them), "Jack—Ben—Harry! hold him! He's just a common thief!"

A roar of laughter followed.

"Good for you, Lilian!" cried Jack, flinging off his hat and blanket, and leaping on the offender's shoulders to pinion his arms. "He shan't have your spoons, Lilian. But allow me to present to you our cousin, Harold Wyman, just arrived from Wyoming. We found him at Uncle Abner's, come to spend New Year's with us."

Lilian, who had captured part of the spoons, blushed and dropped them on the floor.

"It's real mean of you to scare me so," she stammered. "Mother, did you know it was the boys?"

"Not until Jamie winked at me from the floor, and then it was all so ridiculously clear I could not help laughing aloud. I saw you were well over your first fright, so I thought I'd let the boys carry out their fun."

"My, but I'm hot!" ejaculated Ben. "Sis has good grit, hasn't she Harold?"

"Yes," cried Jack, "and she kept her promise about the rosebud china. Let's have dinner. All we lack now is the coffee, Lilian."