Title: Wilt Thou Torchy

Author: Sewell Ford

Release date: December 17, 2005 [eBook #17333]

Most recently updated: December 13, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | ON THE WAY WITH CYBIL |

| II. | TOWING CECIL TO A SMEAR |

| III. | TORCHY HANDS OUT A SPILL |

| IV. | HOW HAM PASSED THE BUCK |

| V. | WITH ELMER LEFT IN |

| VI. | A BALANCE FOR THE BOSS |

| VII. | TORCHY FOLLOWS A HUNCH |

| VIII. | BREAKING ODD WITH MYRA |

| IX. | REPORTING BLANK ON RUPERT |

| X. | WHEN AUNTIE CRASHES IN |

| XI. | A JOLT FROM OLD HICKORY |

| XII. | TORCHY HITS THE HIGH SEAS |

| XIII. | WHEN THE NAVY HORNED IN |

| XIV. | AUNTIE TAKES A NIGHT OFF |

| XV. | PASSING THE JOKE BUCK |

| XVI. | TORCHY TAKES A RUNNING JUMP |

| XVII. | A LITTLE SPEED ON THE HOME STRETCH |

It was a case of declarin' time out on the house. Uh-huh—a whole afternoon. What's the use bein' a private sec. in good standin' unless you can put one over on the time-clock now and then? Besides, I had a social date; and, now Mr. Robert is back on the job so steady and is gettin' so domestic in his habits, somebody's got to represent the Corrugated Trust at these function things.

The event was the openin' of the Pill Box; you know, one of these dinky little theaters where they do the capsule drama at two dollars a seat. Not that I've been givin' my theatrical taste the highbrow treatment. I'm still strong for the smokeless war play where the coisèd spy gets his'n good and hard.

But I understand this one-act stuff is the thing to see just now, and I'd picked up a hunch that Vee and Auntie had planned to be in on this openin' until Auntie's sciatica developed so bad that they had to call it off. So it's me makin' the timely play with a couple of seats in E center and almost gettin' hugged for it. Even Auntie shoots me an approvin' glance as she hands down a favorable decision.

So we sits through five acts of piffle that was mostly talky junk to me. And, at that, I wa'n't sufferin' exactly; for when them actorines got too weird, all I had to do was swing a bit in my seat and I had a side view of a spiffy little white fur boa, with a pink ear-tip showin' under a ripple of corn-colored hair, and a—well, I had something worth watching that's all.

"Wasn't that last thing stupid?" says Vee.

"Didn't bother me any," says I. "Maybe I wa'n't followin' it real close."

"The idea!" says, she. "Why come to the theater, anyway?"

"Lean closer and I'll whisper," says I.

"Silly!" says she. "Here! Have a chocolate."

"Toss," says I, openin' my mouth.

Vee snickers. "Suppose I missed and hit the fat man beyond?"

"It's a sportin' chance he takes," says I. "Shoot."

I had to bump Fatty a bit makin' the catch; but when he sees what the game is, he comes back with the friendly grin.

"There!" says Vee, tintin' up. "Now behave."

"Sorry," says I, "but I had to field my position, didn't I? Once more, now."

"Certainly not," says Vee. "Besides, there goes the curtain."

And if it hadn't been for interruptions like that we might have had a perfectly good time. We generally do when we're let alone. To sort of string the fun out I suggests goin' somewhere for tea. And it was while we're swappin' josh over the toasted crumpets and marmalade that we discovers a familiar-lookin' couple on the dancin' surface.

"Why, there's Doris!" says Vee.

"And the happy hubby!" I adds. "Hey, Westy! Come nourish yourself."

Maybe you remember that pair? Sappy Westlake, anyway. He's the noble, fair-haired youth that for a long time Auntie had all picked out as the chosen one for Vee, and he hung around constant until one lucky day Vee had this Doris Ull come for a visit.

Kind of a pouty, peevish queen, Doris was, you know. Spoiled at home, and the job finished at one of these flossy girls' boardin'-schools where they get a full course in court etiquette and learn to call the hired girl Smith quite haughty.

But she looked good to Westy, and, what with the help Vee and I gave 'em, they made a match of it. Months ago that must 'a' been, nearly a year. So I signals a fray-juggler to pull up more chairs, and we has quite a reunion.

Seems they'd been on a long honeymoon trip: done the whole Pacific coast, stopped off a while at Banff, and worked hack home through Quebec and the White Mountains. Think of all the carfares and tips to bell-hops that means! He don't have to worry, though. Income is Westy's middle name. All he knows about it is that there's a trust company downtown somewheres that handles the estate and wishes on him quarterly a lot more'n he knows how to spend. Beastly bore!

"What a wonderful time you two must have had!" says Vee.

Doris shrugs her shoulders.

"Sightseeing always gives me a headache," says she. "And in the Canadian Rockies we nearly froze. I was glad to see New York again. But one tires of hotel life. Thank goodness, our house is ready at last. We moved in a week ago."

"Oh!" says Vee. "Then you're housekeeping?"

Doris nods. "It's quite thrilling," says she. "At ten-thirty every morning I have the butler bring me Cook's list. Then I 'phone for the things myself. That is, I've just begun. Let me see, didn't I put in to-day's order in my—yes, here it is." And she fishes a piece of paper out of a platinum mesh bag. "Think of our needing all that—just Harold and me," she goes on.

"I should say so," says Vee, startin' to read over the items. "'Sugar, two pounds; tea, two pounds—'"

"Cook leaves the amounts to me," explains Doris; "so I just order two pounds of everything."

"Oh!" says Vee, readin' on. "'Butter, two pounds; eggs, two—' Do they sell eggs that way, Doris?"

"Don't they?" asks Doris. "I'm sure I don't know."

"'Coffee, two pounds,'" continues Vee. "'Yeast cakes, two pounds—' Why, wouldn't that be a lot of yeast cakes? They're such little things!"

"Perhaps," says Doris. "But then, I sha'n't have to bother ordering any more for a month, you see. Now, take the next item. 'Champagne wafers, ten pounds.' I'm fond of those. But that is the only time I broke my rule. See—'flour, two pounds; roast beef, two pounds,' and so on. Oh, I mean to be quite systematic in my housekeeping!"

"Isn't she a wonder?" asks Westy, gazin' at her proud and mushy.

"I say, though, Vee," goes on Doris enthusiastic, "you must come home with us for dinner to-night. Do!"

At which Westy nudges her and whispers something behind his hand.

"Oh, yes," adds Doris. "You too, Torchy."

Vee had to 'phone Auntie and get Doris to back her up before the special dispensation was granted; but at six-thirty the four of us starts uptown for this brownstone bird-cage of happiness that Westy has taken a five-year lease of.

"Just think!" says Vee, as we unloads from the taxi. "You with a house of your own, and managing servants, and—"

"Oh!" remarks Doris, as she pushes the button. "I do hope you won't mind Cyril."

"Mind who?" says Vee.

"He—he's our butler," explains Westy. "I suppose he's a very good butler, too—the man at the employment agency said he was; but—er—"

"I'm sure he is," puts in Doris, "even if he does look a little odd. Then there is his name—Cyril Snee. Of course, Cyril doesn't sound just right for a butler, does it? But Snee is so—so—"

"Isn't it?" says Vee. "I should call him Cyril."

"We started in that way," says Doris, "but he asked us not to; said he preferred to be called Snee. It was unusual, and besides he had private reasons. So between ourselves we speak of him as Cyril, and to his face— Well, I suppose we shall get used to saying Snee, though— Why, where can he be? I've rung twice and— Oh, here he comes!"

And, believe me, when Doris described him as lookin' a little odd she's said sumpun. Cyril was all of that. As far as figures goes he's big and impressive enough, with sort of a dignified bulge around the equator. But that face of his, with the white showin' through the pink, and the pink showin' through the white in the most unexpected places! Like a scraped radish. No, that don't give you the idea of his color scheme exactly. Say a half parboiled baby. For the pink spots on his chin and forehead was baby pink, and the white of his cheeks and ears was a clear, waxy white, like he'd been made up by an artist. Then, the thin gray hair, cropped so close the pink scalp glimmered through; and the wide mouth with the quirky corners; and the greenish pop-eyes with the heavy bags underneath—well, that was a map to remember.

And the worst of it was, I couldn't. Sure, I'd met it. No doubt about that. But I follows the bunch into the house like I was in a trance, starin' at Cyril over Westy's shoulder and askin' myself urgent, "Where have I seen that face before?" No, I couldn't place him. And you know how a thing like that will bother you. It got me in the appetite.

Maybe it was just as well, too, for I'd got half way through the soup before I notices anything the matter with it. My guess was that it tasted scorchy. I glances around at Vee, and finds she's just makin' a bluff at eatin' hers. Doris and Westy ain't even doin' that, and when I drops my spoon Doris signals to take it away. Which Cyril does, movin' as solemn and dignified as if he was usherin' at a funeral. Then there's a stage wait for three or four minutes before the fish is brought in, Cyril paddin' around ponderous with the plates. Doris beckons him up and demands in a whisper:

"Where is Helma?"

"Helma, ma'am," says he, "is taking the evening out."

"But—" begins Doris, then stops and bites her lip.

The fish could have stood some of the surplus cookin' that the soup got. It wa'n't exactly eatable fish, and the potato marbles that come with it should have been numbered; then they'd be useful in Kelley pool. Yes, they was a bit hard. Doris gets red under the eyes and waves out the fish.

She stands it, though, until that two-pound roast is put before Westy. Not such a whale of a roast, it ain't. It's a one-rib affair, like an overgrown chop, and it reposes lonesome in the middle of a big silver platter. It's done, all right. Couldn't have been more so if it had been cooked in a blast-furnace. Even the bone was charred through.

Westy he gazes at it in his mild, helpless way, and pokes it doubtful with the carvin'-fork.

"I say, Cyr—er—Snee," says he, "what's this?"

"The roast, sir," says the butler.

"The deuce it is!" says Westy. "Do—do I use a saw or dynamite?" And he stares across at Doris inquirin'.

"Snee," says Doris, her upper lip trembling "you—you may take it away."

"Back to the kitchen, ma'am?" asks Cyril.

"Ye-es," says Doris. "Certainly."

"Very well, ma'am," says Cyril, sort of tragic and mysterious.

He hadn't more'n got through the swing-door before Doris slumps in her chair, puts her face into her hands, and begins lettin' out the sobs reckless. Course, Westy jumps to the rescue and starts pattin' her on the back and offerin' soothin' words. So does Vee.

"There, there!" says Vee. "We don't mind a bit. Such things are bound to happen."

"But I—I don't know what to do," sobs Doris. "It's—it's been getting worse every day. They began all right—the servants, I mean. But yesterday Marie was impudent, and to-night Helma has gone out when she shouldn't, and now Cook has spoiled everything, and—"

We ain't favored with the rest of the sad tale, for just then there's a quick scuff of feet, and Cyril comes skatin' through the pantry door and does a frantic dive behind the sideboard.

Doris straightens up, brushes her eyes clear, and makes a brave stab at bein' dignified.

"Snee," says she, real reprovin'.

"I—I beg pardon, ma'am," says Cyril, edgin' out and revealin' a broad black smooch on his shirt-front as well as a few other un-butlery signs.

"Why, whatever has happened to yon?" demands Doris.

"I'm not complaining, ma'am," says Cyril; "but Cook, you see, she—she didn't like it because of my bringing back the roast. And I'm not very good at dodging, ma'am."

"Oh!" says Doris, shudderin'.

"It struck me here, ma'am," says Cyril, indicatin' the exact spot.

"Yes, yes, I see," says Doris. "I—I'm sorry, Snee."

"Not at all, ma'am," objects Cyril. "My fault entirely. I should have jumped quicker. And it might have been the pudding. That wouldn't have hit so hard, but it would have splashed more. You see, ma'am, I—"

"Never mind, Snee," cuts in Doris, tryin' to stop him.

"I don't, ma'am, I assure you," says Cyril, pluckin' a spray of parsley off his collar. "I was only going to remark what a wonderful true eye Cook has, ma'am; and her in liquor, at that."

"Oh, oh!" squeals Doris panicky.

"It began when I brought her the brandy for the pudding sauce, ma'am," goes on Cyril, real chatty. "She'd had only one glass when she begins chucking me under the chin and calling me Dearie. Not that I ever gave her any cause, ma'am, to—"

"Please!" wails Doris. "Harold! Stop him, can't you?"

And say, can you see Sappy Westlake stoppin' anything? Specially such a runnin' stream as this here now Cyril. But he comes to life for one faint effort.

"I say, you know," he starts in, "perhaps you'd best say no more about it, Snee."

"As you like, sir," says Cyril. "Only, I don't wish my feelings considered. Not in the least. If you care to send back the salad I will gladly—"

Westy glances appealin' towards me.

"Torchy," says he, "couldn't you—"

Couldn't I, though! Say, I'd just been yearnin' to crash into this affair for the last five minutes. I'd remembered Cyril. At least, I thought I had. And I proceeds to rap for order with a table-knife.

"Excuse me, Mr. Snee," says I, "but you ain't been called on for a monologue. You can print the whole story of how kitchen neutrality was violated, issue a yellow book, if you like; but just for the minute try to forget that assault with the roast and see if you can remember ever havin' met me before. Can you?"

Don't seem to faze Cyril a bit. He takes a good look at me and then shakes his head.

"I'm sorry, sir," says he, "but I'm afraid I'm stupid about such things. I can sometimes recall names very readily, but faces—"

"How long since you quit jugglin' pies and sandwiches at the quick-lunch joint?" says I.

"Three months, sir," says he prompt.

"Tied the can to you, did they?" says I.

"I was discharged, sir," says Cyril. "The proprietor objected to my talking so much to customers. I suppose he was quite right. One of my many failings, sir."

"I believe you," says I. "So you took up buttling, eh? Wa'n't that some nervy jump?"

"I considered it a helpful step in my career," says he.

"Your which?" says I.

"Perhaps I should put it," says he, "that the work seemed to offer the discipline which would make me most useful to our noble order."

And as he says the last two words he puts his palms at right angles to his ears, thumbs in, and bows three times.

"Eh?" says I, gawpin'.

"I refer," says Cyril, "to the Brotherhood of the Sacred Owls, which is also named the Sublime Order of Humility and Wisdom."

And once more he does the ear wigwag. Believe me, he had us all gaspin'.

"Vurra good, Eddie!" says I. "Sacred Owls, eh? What is that—one of these insurance schemes?"

"There are both mortuary and sick benefits appertaining to membership," says Cyril, "but our chief aim and purpose is to acquire humility and wisdom. It so happens that I have been named as candidate for Grand Organizer of the East, and at our next solemn conclave, to be held—"

"I get you," says I. "I can see where you might find some practice in bein' humble by buttlin', but how about gettin' wise?"

"With humility comes wisdom, as our public ritual has it," says Cyril. "In the text-book which I studied—'The Perfect Butler'—there was very little about being humble, however. But my cousin, who conducts an employment agency, assured me that could only be acquired by practice. So he secured me several positions. He was wholly correct. I have been discharged on an average of once a week for the last two months, and on each occasion I have discovered newer and deeper depths of humility."

I draws a long breath and gazes admiring at Cyril. Then I turns to the Westlakes.

"Westy," says I, "do you want to accommodate Mr. Snee with a fresh chance of perfectin' himself for the Sublime Order?"

He nods. So does Doris.

"It's a unanimous vote, Cyril," says I. "You're fired. Not for failin' to duck the roast, understand, but because you're too gabby."

"Thank you, sir," says he, actin' a little disappointed. "I am to leave at once, I suppose?"

"No," says I. "Stop long enough in the kitchen to tell Cook she gets the chuck, too. After that, if you ain't qualified as Grand Imperial Organizer of the whole United States, then the Sacred Owls don't know their business. By-by, Cyril. We're backin' you to win, remember."

And as I pushes him through the pantry door I locks it behind him. Followin' which, Doris uses the powder-puff under her eyes a little and we adjourns to the Plutoria palm-room, where we had a perfectly good dinner, all the humility Westy could buy with a two-dollar tip, and no folksy chatter on the side.

Next day the Westlakes calls up another agency, and by night they had an entire new line of help on the job.

What do you guess, though? Here yesterday afternoon I leaves the office on the jump and chases up to the apartment house where Vee and Auntie are settled for the winter. My idea was that I might catch Vee comin' home from a shoppin' orgie, or the matinée, or something, and get a few minutes' conversation in the lobby.

The elevator-boy says she's out, too, so it looks like I was a winner. I waits half an hour and she don't show up, and I'm just about to take a chance on ringin' up Auntie for information, when in she comes, chirky and smilin', with rose leaves sprinkled on both cheeks and her eyes sparklin'. Also she has a bundle of books under one arm.

"Why the literature?" says I. "Goin' to read Auntie to sleep?"

"There!" says she, poutin' cute. "I wasn't going to let anyone know. I've started in at college."

"Wha-a-at!" says I. "You ain't never goin' to be a lady doctor or anything like that, are you?"

"I am taking a course at Columbia," says Vee, "in domestic science. Doris is doing it, too. And such fun! To-day we learned how to make a bed—actually made it up, too. To-morrow I am going to boil potatoes."

"Hel-lup!" says I. "You are? Say, how long does this last?"

"It's a two-year course," says Vee.

"Stick to it," says I. "That'll give me time to take lessons from Westy on how to get an income wished onto me."

As it stands, though, Vee's got me distanced. Please, ain't somebody got a plute aunt to spare?

Just think! If it had turned out a little different I might have been called to stand on a platform in front of City Hall while the Mayor wished a Victoria Cross or something like that on me.

No, I ain't been nearer the front than Third Avenue, but at that I've come mighty near gettin' on the firin' line, and the only reason I missed out on pullin' a hero stunt was that Maggie wa'n't runnin' true to form.

It was like this. Here the other mornin', as I'm sittin' placid at my desk dictatin' routine correspondence into a wax cylinder that's warranted not to yank gum or smell of frangipani—sittin' there dignified and a bit haughty, like a highborn private sec. ought to, you know—who should come paddin' up to my elbow but the main wheeze, Old Hickory Ellins.

"Son," says he, "can any of that wait?"

"Guess it wouldn't spoil, sir," says I, switchin' off the duflicker.

"Good!" says he. "I think I can employ your peculiar talents to better advantage for the next few hours. I trust that you are prepared to face the British War Office?"

Suspectin' that he's about to indulge in his semi-annual josh, I only grins expectant.

"We have with us this morning," he goes on, "one Lieutenant Cecil Fothergill, just arrived from London. Perhaps you saw him as he was shown in half an hour or so ago?"

"The solemn-lookup gink with the long face, one wanderin' eye, and the square-set shoulders?" says I. "Him in the light tan ridin'-breeches and the black cutaway?"

"Precisely," says Mr. Ellins.

"Huh!" says I. "Army officer? I had him listed as a rail-bird from the Horse Show."

"He presents credentials signed by General Kitchener," says Old Hickory. "He's looking up munition contracts. Not the financial end. Nor is he an artillery expert. Just exactly what he is here for I've failed to discover, and I am too busy to bother with him."

"I get you," says I. "You want him shunted."

Old Hickory nods.

"Quite delicately, however," he goes on.

"The Lieutenant seems to have something on his mind—something heavy. I infer that he wishes to do a little inspecting."

"Oh!" says I.

You see, along late in the summer, one of our Wall Street men had copped out a whalin' big shell-case contract for us, gayly ignorin' the fact that this was clean out of our line.

How Old Hickory did roast him for it at the time! But when he come to figure out the profits, Mr. Ellins don't do a thing but rustle around, lease all the stray factories in the market, from a canned gas plant in Bayonne to a radiator foundry in Yonkers, fit 'em up with the proper machinery, and set 'em to turnin' out battle pills by the trainload.

"I gather," says Mr. Ellins, "that the Lieutenant suspects we are not taking elaborate precautions to safeguard our munition plants from—well, Heaven knows what. So if you could show him around and ease his mind any it would be helpful. At least, it would be a relief to me just now. Come in and meet him."

My idea was to chirk him up at the start.

"Howdy, Lieutenant," says I, extendin' the cordial palm.

But both the Lieutenant's eyes must have been wandering for he don't seem to notice my friendly play.

"Ha-ar-r-r yuh," he rumbles from somewhere below his collar-button, and with great effort he manages to focus on me with his good lamp. For a single-barreled look-over, it's a keen one, too—like bein' stabbed with a cheese-tester. But it's soon over, and the next minute he's listenin' thoughtful while Old Hickory is explainin' how I'm the one who can tow him around the munition shops.

"Torchy," Mr. Ellins winds up with, shootin' me a meanin' look from under his bushy eyebrows, "I want you to show the Lieutenant our main works."

"Eh?" says I, gawpin'. For he knew very well there wasn't any such thing.

His left eyelid does a slow flutter.

"The main works, you understand," he repeats. "And see that Lieutenant Fothergill is well taken care of. You will find the limousine waiting."

"Yes, sir," says I. "I'm right behind you."

Course, if Mr. Robert had been there instead of off honeymoonin', this would have been his job. He'd have towed Cecil to his club, fed him Martinis and vintage stuff until he couldn't have told a 32-inch shell from an ashcan; handed him a smooth spiel about capacity, strain tests, shipping facilities, and so on, and dumped him at his hotel entirely satisfied that all was well, without having been off Fifth Avenue.

The best I can do, though, is to steer him into a flossy Broadway grill, shove him the wine-card with the menu, and tell him to go the limit.

He orders a pot of tea and a combination chop.

"Oh, say, have another guess," says I. "What's the matter with that squab caserole and something in a silver ice-bucket?"

"Thank you, no," says he. "I—er—my nerves, you know."

I couldn't deny that he looked it, either. Such a high-strung, jumpy party he is, always glancin' around suspicious. And that wanderin' store eye of his, scoutin' about on its own hook independent of the other, sort of adds to the general sleuthy effect. Kind of weird, too.

But I tries to forget that and get down to business.

"Surprisin' ain't it," says I, "how many of them shells can be turned out by—"

"S-s-s-sh!" says he, glancin' cautious at the omnibus-boy comin' to set up our table.

"Eh?" says I, after we've been supplied with rolls and sweet butter and ice water. "Why the panic?"

"Spies!" he whispers husky.

"What, him?" says I, starin' after the innocent-lookin' party in the white apron.

"There's no telling," says Cecil. "One can't be too careful. And it will be best, I think, for you to address me simply as Mr. Fothergill. As for the—er—goods you are producing, you might speak of them as—er—hams, you know."

I expect I gawped at him some foolish. Think of springin' all that mystery dope right on Broadway! And, as I'm none too anxious to talk about shells anyway, we don't have such a chatty luncheon. I'm just as satisfied. I wanted time to think what I should exhibit as the main works.

That Bayonne plant wa'n't much to look at, just a few sheds and a spur track. I hadn't been to the Yonkers foundry, but I had an idea it wa'n't much more impressive. Course, there was the joint on East 153d Street. I knew that well enough, for I'd helped negotiate the lease.

It had been run by a firm that was buildin' some new kind of marine motors, but had gone broke. Used to be a stove works, I believe.

Anyway, it's only a two-story cement-block affair, jammed in between some car-barns on one side and a brewery on the other. Hot proposition to trot out as the big end of a six-million-dollar contract! But it was the best I had to offer, and after the Lieutenant had finished his Oolong and lighted a cigarette I loads him into the limousine again and we shoots uptown.

"Here we are," says I, as we turns into a cross street just before it ends in the East River. "The main works," and I waves my band around casual.

"Ah, yes," says he, gettin' his eye on the tall brick stack of the brewery and then lettin' his gaze roam across to the car-barns.

"Temporary quarters," says I. "Kind of miscellaneous, ain't they? Here's the main entrance. Let's go in here first." And I steers him through the office door of the middle buildin'. Then I hunts up the superintendent.

"Just takin' a ramble through the works," says I. "Don't bother. We'll find our way."

Some busy little scene it is, too, with all them lathes and things goin', belts whirrin' overhead, and workmen in undershirts about as thick as they could be placed.

I towed Cecil in and out of rooms, up and down stairs, until he must have been dizzy, and ends by leadin' him into the yard.

"Storage sheds," says I, pointin' to the neat rows of shell-cases piled from the ground to the roof. "And a dozen motor-trucks haulin' 'em away all the time."

The Lieutenant he inspects some of 'em, lookin' wise; and then he walks to the back, where there's a high board fence with barbed wire on top. "What's over there?" says he.

"Blamed if I know," says I.

"It's rather important," says he. "Let's have a look."

I didn't get the connection, but I helped him shove a packin'-case up against the fence, so he could climb up. For a minute or so he stares, then he ducks down and beckons to me.

"I say," he whispers. "Come up here. Don't show your head. There! What do you make of that?"

So I'm prepared for something tragic and thrillin'. But all I can see is an old slate-roofed house, one of these weather-beaten, dormer-windowed relics of the time when that part of town was still in the suburbs. There's quite a big yard in the back, with a few scrubby old pear trees, a double row of mangy box-bushes, and other traces of what must have been a garden.

In the far corner is a crazy old summer-house with a saggin' roof and the sides covered with tar paper. There's a door to it, fastened with a big red padlock.

Standin' on the back porch of the house are two of the help, so I judged. One is a square-built female with a stupid, heavy face, while the other is a tall, skinny old girl with narrow-set eyes and a sharp nose.

"Well," says I, "where's your riot?"

"S-s-s-sh!" says he. "They're up to some mischief. One of them is hiding something under her shawl. Watch."

Sure enough, the skinny one did have her left elbow stuck out, and there was a bulge in the shawl.

"Looks like a case of emptyin' the ashes," says I.

"Or of placing a bomb," whispers the Lieutenant.

"Mooshwaw!" says I. "Bomb your aunt! What for should they—"

"Look now!" he breaks in. "There!"

They're advancin' in single file, slow and stealthy, and gazin' around cautious. Mainly they seem to be watchin' the back fire-escapes of the flat buildin' next door, but now and then one of 'em turns and glances towards the old house they've just left. They make straight for the shack in the corner of the yard, and in a minute more the fat one has produced a key and is fumblin' with the red padlock.

She opens the door only far enough to let the slim one slip in, then stands with her back against it, her eyes rollin' first one way and then the other.

Two or three minutes the slim one was in there, then she slides out, the door is locked, and she scuttles off towards the house, the wide one waddlin' behind her.

"My word!" gasps the Lieutenant. "Right against the wing of your factory, that shed is. And a bomb of that size would blow it into match-wood."

"That's so," says I.

Course, we hadn't really seen any bomb; but, what with the odd notions of them two females and the Lieutenant's panicky talk, I was feelin' almost jumpy myself.

"A time-fuse, most likely," says he, "set for midnight. That should give us several hours. We must find out who lives in that house."

"Ought to be simple," says I. "Come on."

We chases around the block and rings up the janitor of the flat buildin'. He's a wrinkled, blear-eyed old pirate, just on his way to the corner with a tin growler.

"Yah! You won't git in to sell him no books," says he, leerin' at us.

"Think so?" says I, displayin' a quarter temptin'. "Maybe if we had his name, though, and knew something about him, we might—"

"It's Bauer," says the janitor, eyein' the two bits longin'. "Herman Z. Bauer; a big brewer once, but now—yah, an old cripple. Gout, they say. And mean as he is rich. See that high fence? He built that to shut off our light—the swine! Bauer, his name is. You ask for Herman Bauer. Maybe you get in."

"Thanks, old sport," says I, slippin' him the quarter. "Give him your best regards, shall I?"

And as he goes off chucklin' the Lieutenant whispers hoarse:

"Hah! I knew it. Bauer, eh? And to-night he'll be sitting at one of those back windows, his ears stuffed with cotton, watching to see your plant blown up. We must have the constables here right away."

"On what charge?" says I. "That two of the kitchen maids was seen in their own back yard? You know you can't spring that safety-of-the-realm stuff over here. The police would only give us the laugh. We got to have something definite to tell the sergeant. Let's go after it."

"But I say!" protests Cecil. "Just how, you know?"

"Not by stickin' here, anyway," says I. "Kick in and use your bean, is my program. Come along and see what happens."

So first off we strolls past and has a look at the place. It's shut in by a rusty iron fence with high spiked pickets. The house sets well back from the sidewalk, and the front is nearly covered by some sort of vine. At the side there are double gates openin' into a grass-grown driveway.

I was just noticin' that they was chained and locked when the Lieutenant gives me a nudge and pulls me along by the coat sleeve. I gets a glimpse of the square-built female waddlin' around the corner of the house. We passes by innocent and hangs up in front of a plumbery shop, starin' in at a fascinatin' display of one bathtub and a second-hand hot-water boiler. Out of the corner of my eye, though, I could see her scout up and down the street, unfasten the gate, and then disappear.

"Huh!" says I. "Kitchen company expected."

"Or more conspirators," adds Cecil. "By Jove! Isn't this one now?"

There's no denyin' he looked the part, this short-legged, long-armed, heavy-podded gent with the greasy old derby tilted rakish over one ear. Such a hard face he has, a reg'lar low-brow map, and a neck like a choppin'-block. His stubby legs are sprung out at the knees, and his arms have a good deal the same curve.

"Built like a dachshund, ain't he?" I remarks.

"Quite so," says Fothergill. "See, he's stopping. And he has a bundle under one arm."

"Overalls," says I. "Plumber, maybe."

"Isn't that a knife-handle sticking out of the end of the bundle?" asks the Lieutenant.

So it was; a butcher knife, at that. He has stopped opposite the double gates and is scowlin' around. Then he glances quick at the house. A side shutter opens just then and a dust-cloth is shaken vigorous. Seein' which, he promptly pushes through the gates.

"Ha!" says the Lieutenant. "A signal. He'll be the one to attach the fuse and light it, eh?"

Well, I admit that up to that time I hadn't been takin' all this very serious, discountin' most of Cecil's suspicions as due to an over-worked imagination. But now I'm beginnin' to feel thrills down my spine.

What if this was a bomb plot? Some sort of bunk was being put over here—no gettin' away from that. And if one of our shell factories was in danger of being dynamited, here was my cue to make a medal play, wa'n't it?

"I am for telephoning the authorities at once," announces Cecil.

"Ah, you don't know our bonehead cops," says I. "Besides, if we can block the game ourselves, what's the use? Let's get 'em in the act. I'm going to pipe off our friend with the meat-knife."

"I—I've only a .34-caliber automatic with me," says the Lieutenant, reachin' into his side pocket.

"Well, you don't want a machine-gun, do you?" says I. "And don't go shootin' reckless. Here, lemme get on the other side. Close to the house, now, on the grass, until we can get a peek around the—"

"S-s-s-sh!" says Cecil, grippin' my arm. He was strong on shushin' me up, the Lieutenant was. This time, though, he had the right dope; for a few steps more and we got a view of the back porch.

And there are the two maids, hand in hand, watchin' the motions of the squatty gent, who is unlockin' the summer-house. He disappears inside.

At that Cecil just has to cut loose. Before I can stop him, he's stepped out, pulled his gun, and is wavin' it at the two females.

"I say, now! Hands up! No nonsense," he orders.

"Howly saints!" wails the square-built party, clutchin' the slim one desperate. "Maggie! Maggie!"

Maggie she's turned pale in the gills, her mouth is hangin' open, and her eyes are bugged, but she ain't too scared to put up an argument.

"Have yez a warrant?" she demands. "Annyways, my Cousin Tim Fealey'll go bail for us. An' if it was that Swede janitor next door made the complaint on us I'll—"

"Woman!" breaks in the Lieutenant. "Don't you know that you have been apprehended in a grave offense? You'd best tell all. Now, who put you up to this? Your master, eh?"

"Howly saints! Mr. Bauer!" groans the fat one.

"For the love of the saints, don't tell him!" says Maggie. "Don't tell Mr. Bauer, there's a dear. It was off'm Cousin Tim we got it."

"That miscreant in the shed there?" asks the Lieutenant.

"Him?" says Maggie. "Lord love ye, no. That's only Schwartzenberger, from the slaughter-house. And please, Mister, it'll be gone the mornin'—ivry bit gone."

"Oh, will it!" says Cecil sarcastic. "But you'll be in prison first."

"Wurra! Wurra!" moans the fat female. "Save us, Maggie! Let him have it for the takin's."

"I will not, then," says Maggie. "Not if he's the president of the Board of Health himself."

"Enough of this," says the Lieutenant. "Hands up, you bomb plotters!"

But about then I'd begun to acquire the hunch that we might be makin' a slight mistake, and that it was time for me to crash in. Which I does.

"Excuse me," says I; "but maybe it would help, Maggie, if you'd say right out what it is you've got in the shed there."

"What is ut?" says she, tossin' her head defiant. "As though you didn't know! Well, it's a pig, then."

"A pig!" sneers the Lieutenant. "Very likely, that is!"

"Yez didn't think it was a hip-pot-ta-mus, did ye?" comes back Maggie. "An' why should you be after botherin' us with your health ordinances—two poor girls that has a chance to turn a few pennies, with pork so dear? 'Look at all that good swill goin' to waste,' says I to Katie here. 'An' who's to care if I do boil some extra praties now an' then? Mr. Bauer's that rich, ain't he? An' what harm at all should there be in raisin' one little shoat in th' back yard?' So there, Mister! Do your worst. An' maybe it's only a warnin' I'll get from th' justice when he hears how Schwartzenberger's killed and dressed and taken him off before daylight. There he goes, the poor darlint! That's his last squeal."

We didn't need to stretch our ears to catch it. I looks over at the Lieutenant and grins foolish. But he wouldn't be satisfied until Maggie had towed him out to view the remains. He's pink behind the ears when he comes back, too.

"Please, Mister Inspector," says Maggie, "you'll not have us up this time, will yez?"

"Bah!" says Cecil.

"Seein' it's you," says I, "he won't. Course, though, a report of this plot of yours'll have to be made to the British War Office."

"Oh, I say now!" protests the Lieutenant.

And all the way down to his hotel he holds that vivid neck tint.

"Well," says Old Hickory, as I drifts back to the office, "did you and the Lieutenant discover any serious plot of international character?"

"Sure thing!" says I. "We found a contraband Irish pig in Herman Bauer's back yard.

"Wha-a-at?" he demands.

"If the pig had been a bomb, and its tail a time-fuse," says I, "it would have wrecked our main works. As it, is, we've had a narrow escape. But I don't think Cecil will bother us any more. He's too good for the army, anyway. He ought to be writin' for the movies."

Maybe I've indulged, now and then, in a few remarks on Auntie. But, say, there's no danger of exhaustin' the subject—not a chance. For she's some complicated old girl, take it from me. First off, there's that stick-around disposition of hers. Now, I expect that just naturally grew on her, same as my pink thatch did on me. She can't help it; and what's the use blamin' her for it?

So, when I drop in for my reg'lar Wednesday and Sunday night calls, the main object of the expedition being to swap a little friendly chatter with Vee, and I find Auntie planted prominent and permanent in the sittin'-room, why, I just grins and makes the best of it.

A patient and consistent sitter-out, Auntie is. And you know that face of hers ain't exactly the chirky sort. Don't encourage you to get chummy, or tip her the confidential wink, or chuck her under the chin. Nothing like that—no.

Not a regular battle-ax, you understand. For all that, she ain't such a bad-lookin' old dame, when you get her in a dim light. Though the expression she generally favors me with, while it ain't so near assault and battery as it used to be, wouldn't take the place of two lumps in a cup of tea.

But you kind of get used to that acetic acid stuff after a while; and, since I'm announced by a reg'lar name now—"Meestir Beel-lard" is Helma's best stab at Ballard—and Auntie knowin' that I got a perfectly good uncle behind me, besides bein' a private sec. myself, why, she don't mean more'n half of it.

Besides, even with her sittin' right there in the room, there's a lot doin' that she ain't in on. Trust Vee. Say, she can drum out classical stuff on the piano and fire a snappy line of repartee at me all the while, just loud enough for me to catch and no more, without battin' an eye. Say, I'm gettin' quite a musical education, just helpin' to stall off Auntie that way. And you should see the cute schemes Vee puts over—settin' a framed photo so it throws the light in the old girl's eyes, or shiftin' our chairs so she has to stretch her neck to keep track of us.

Makes an evenin' call quite an excitin' game; and when we work in a few minutes of hand-holdin', or I get away with a hasty clinch, why, that scores for our side. So, for a personally conducted affair, it ain't so poor. I'm missin' no dates, I notice. And tuck this away; if it was a case of Vee and a whole squad of aunts, or an uninterrupted two-some with one of these nobody-home dolls, I'd pick Vee and the gallery. Uh-huh! I'm just that good to myself.

All was goin' along smooth and merry, too, until one Wednesday night I discovers another lid ahead of mine on the hall table. It's a glossy silk tile, with a pair of gray castor gloves folded neat alongside. Seein' which I reaches past Helma for the silver card-tray.

"Huh!" says I under my breath. "Now, who the giddy gallowampuses is Clyde Creighton?"

"Vair nice gentlemans, Meester Creeton," whispers Helma.

"I know," says I; "you're judgin' by the hat."

She springs that silly grin of hers, as usual. No matter what I say, it gets open-faced motions out of Helma. But I really wasn't feelin' so humorous. Whoever he was, this Creighton guy had come the wrong evenin'. Course, I judged it must be Vee he's callin' on, and I wasn't strong for a three-handed session just then. There was something special I wanted to talk over with Vee this particular evenin', and I couldn't see why—

But, my first glimpse of Clyde soothes me down a lot. He has curly gray hair, also a mustache that's well frosted up. He's a tall, slim built party, with a wide black ribbon to tie him to his eyeglasses. Seems to be entertainin' Auntie.

"Ah!" says he, inspectin' me casual over the shell rims. "Mr. Ballard?" And, with a skimpy little nod, he turns back to Auntie and goes on where he broke off, leavin' me to shake hands with myself if I wanted to.

I expect it served me right, cuttin' in abrupt on such a highbrow conversation as that. Something about the pre-Raphael tendencies of the Barbizon school, I think.

Culture! Say, if I'm any judge, Claude was battin' about 400. It fairly dripped from him. Talk about broad o's—he spilled 'em easy and natural, a font to a galley; and he couldn't any more miss the final g than a telephone girl would overlook rollin' her r's. And such graceful gestures with the shell-rimmed glasses, wavin' 'em the whole length of the ribbon when he got real interested.

I don't think I ever saw Auntie come so near beamin' before. She seems right at home, fieldin' that line of chat. And Vee, too, is more or less under the spell. As for me, I'm on the outside lookin' in. I did manage though, after doin' the dummy act for half an hour, to lead Vee off to the window alcove and get in a few words.

"Who's the professor?" says I.

"Why, he isn't a professor," says Vee.

"He's got the patter," says I. "Old friend of Auntie's, I take it?"

No, it wasn't quite that. Seems the late Mrs. Creighton had been a chum of Auntie's 'way back when they was girls, and the fact had only been discovered when Clyde and Auntie got together a few days before at some studio tea doins'.

"About how late was the late Mrs. C. C.?" says I.

"Oh, he has been a widower for several years, I think," says Vee. "Poor man! Isn't he distinguished-looking?"

"Ye-e-es," says I. "A bit stagey."

"How absurd!" says she. "Isn't it fascinating to hear him talk?"

"Reg'lar paralyzin'," says I. "I was gettin' numb from the knees down."

"Silly!" says Vee, givin' me a reprovin' pat. "Do be quiet; he is telling Auntie about his wife now."

Yep, he was. Doin' it beautiful too, sayin' what a lovely character she had, how congenial they was, and what an inspiration she'd been to him in his career.

"Indeed," he goes on, "if it had not been for the gentle influence of my beloved Alicia, I should not be what I am to-day."

"Say," I whispers, nudgin' Vee, "what is he to-day?"

"Why," says she, "why—er—I don't quite know. He collects antiques, for one thing."

"Does he?" says I. "Then maybe he's after Auntie."

First off Vee snickers, after which she lets on to be peeved and proceeds to rumple my hair. Clyde catches her at it too, and looks sort of pained. But Auntie's too much interested in the reminiscences to notice. Yes, there's no discountin' the fact that the old girl was fallin' for him hard.

Not that we thought much about it at that time. But later on, when I finds he's been droppin' in for tea, been there for dinner Saturday, and has beat me to it again Sunday evenin', I begins to sprout suspicions.

"He seems to be gettin' the habit, eh?" I suggests to Vee.

She don't deny it.

"Who's doin' the rushin'," says I, "him or Auntie?"

Vee shrugs her shoulders. "He came around to-night," says she, "to show Auntie some miniatures of the late Alicia. She asked to see them. Look! They are examining one now."

Sure enough they were, with their heads close together. And Auntie is pattin' him soothin' on the arm.

"Kind of kittenish motions, if you ask me," says I. "She's gazin' at him mushy, too."

"I never knew Auntie to be quite so absurd," says Vee.

"Say," I whispers, "how about givin' 'em a sample of the butt-in act, so they'll know how it seems?"

Vee smothers a giggle.

"Let's!" says she.

So we leaves the alcove and crashes in on this close-harmony duet. Vee has to see the miniatures of Alicia, and she has to show 'em to me. Also we pulls up chairs and sits there, listenin' with our mouths open, right in the midst of things.

Auntie does her best to shunt us, too.

"Verona," says she, "why don't you and Torchy get out the chafing-dish and make some of that delicious maple fudge you are so fond of."

"Why, Aunty!" says Vee. "When you know I've stopped eating candy for a month."

"You might play something for him," is Auntie's next suggestion. "That new chanson."

"But we'd much rather listen to you and Mr. Creighton," says Vee. "Hadn't we, Torchy?"

"Uh-huh," says I.

"Quite flattering, I'm sure," puts in Clyde, smilin' sarcastic, while Auntie shoots a doubtful look at me.

But we hung around just the same, and before ten o'clock Creighton announces that he must really be going.

"Me too," says I, cheerful. "I'll ride down with you if you don't mind."

"Oh, charmed!" says Clyde.

It wasn't that I was so strong for his comp'ny, but I'd just annexed the idea that it might be a good hunch to get a little line on exactly who this Mr. Clyde Creighton was. Vee don't seem to know anything very definite about him, outside of the Alicia incident; and it struck me that if there was a prospect of havin' him in the fam'ly, as it were, someone ought to see his credentials. Anyway, it wouldn't do any harm to pump him a bit.

"Pardon me for changing my mind," says Clyde, as we hits the sidewalk, "but I think I prefer to walk downtown."

"Just what I was goin' to spring on you," says I. "Fine evenin' for a little thirty-block saunter, too. Let's see, the Plutoria's where you're staying ain't it?"

"Why—er—yes," says he, hesitatin'.

I couldn't make out why he should choke over it, for I'd heard him say distinctly he was livin' there. But it was amazin' what an effect the night air had on his conversation works. Seemed to dry 'em up.

"Interested in antiques, are you?" says I, sort of folksy.

"Somewhat," says Clyde, steppin' out brisk.

"Odd line," says I. "Now, I could never see much percentage in havin' grandfathers' clocks and old spinning-wheels and such junk around."

"Really," says he.

"One of your fads, I expect?" says I.

"M-m-m," says he.

"Shouldn't think you'd find room in a hotel for such stuff," I goes on, doin' a hop-skip across a curb, "or do you have another joint, too?"

"Quite so," says he. "Studio."

"Oh!" says I. "Whereabouts?"

"In town," says he.

"Yes, most of 'em are," says I. "But I expect you'll be gettin' married again some of these days and settin' up a reg'lar home, eh?"

He stops short and gives me a stare.

"If I feel the need of discussing the project," says he, "I shall remember that you are available."

"Oh, don't mention it," says I.

Somehow, I didn't tap Clyde for so much real information. In fact, if I'd been at all touchy I might have worked up the notion that I was bein' snubbed.

I keeps step with Mr. Creighton clear to his hotel, where he swings in the Fifth Avenue entrance without wastin' any breath over fond adieus. I can't say why I didn't go on home then, instead of hangin' up outside. Maybe it was because the sidewalk taxi agent had sort of a familiar look, or perhaps I had an idea I was bein' sleuthy.

Must have been four or five minutes I'd been standin' there, starin' at the entrance, when out through the revolvin' door breezes Clyde, puffin' a cigarette and swingin' his walkin'-stick jaunty. He don't spot me until he's about to brush by, and then he stops short.

"Forgot something?" I suggests.

"Ah—er—evidently," says he, and whirls and marches back into the hotel.

"Huh!" says I, indicatin' nothin' much.

"Where to, sir?" says someone at my elbow.

It's the taxi agent, who has drifted up and mistaken me for a foolish guest.

Kind of a throaty, husky voice he has, that you wouldn't forget easy; and I knew them aëroplane ears of his couldn't be duplicated.

"Why, hello, Loppy!" says I. "How long since you quit runnin' copy in the Sunday room?"

"Well, blow me!" says he. "Torchy, eh?"

That's what comes of havin' been in the newspaper business once. You never know when you're going to run across one of the old crowd. I cut short the reunion, though, to ask about Creighton.

"The swell in the silk lid I just had words with," says I.

"Don't place him," says Loppy. "Never turned a flag for him, anyway. Why?"

"Oh, I'd kind of like to get a sketch of him," says I.

"That's easy," says Loppy. "Remember Scanlon, that used to be doorman at Headquarters?"

"Squint?" says I.

"Same one," says he. "Well, he's inside—one of the house detective squad. His night on, too. And say, if your man's one that hangs out here you can bank on Squint to give you the story of his life. Just step in and send a bell-hop after Squint. Say I want him."

And inside of two minutes we had Squint with us. He remembers me too, and when he finds I'm an old friend of Whitey Weeks he opens up.

"Yes, I've seen that party around more or less," says he. "Creighton, eh? Well, he's no guest. Yes, I'm sure he don't room here. He just blew through the north exit. What's his line?"

"Antiques, he says," says I.

"Oh, sure!" says Squint. "Now I have him located. He's a free-lunch hitter; I remember one of the barkeeps grouching about him. But say, if you're after full details you ought to have a talk with Colonel Brassle. He knows him. And the Colonel ought to be strolling in from the Army and Navy Club soon. Want to wait?"

"Long as I've started this thing, I might as well stay with it," says I.

Yep, I waits for the Colonel. Some enthusiastic describer, Colonel Brassle is, when he gets going. It was near 1 A.M. when I finally tears myself away; but I'm loaded up with enough facts about Creighton to fill a book. And few of 'em was what you might call complimentary to Clyde. For one thing, his dear Alicia hadn't found him as inspirin' as he had her. Anyway, she'd complained a lot about his hang-over disposition, and finally quit him for good five or six years before she passed on. Also, Clyde was no plute. He was existin' chiefly on bluff at present, and that studio of his was a rear loft over a delivery-truck garage down off Sixth Avenue. Then, there was other items just as interestin'.

But how I was goin' to get it all on record for Auntie I couldn't quite dope out. Anyway, there was no grand rush; it would keep. So I just lets things slide for a day or so. Maybe next Wednesday evenin' I'd have a chance to throw out a hint.

Then, here Tuesday afternoon I gets this trouble call from Vee. She's out at the corner drug store on the 'phone.

"It's about Auntie," says she. "She is acting so queerly."

"Any more so than usual?" I asks.

"She is going somewhere, and she hasn't told me a word about it," says Vee. "I found her traveling-bag, all packed, hidden under the hall-seat."

"The old cut-up!" says I. "What about Creighton—he been around lately?"

"Every afternoon and evening," says Vee. "He's to take her to a concert somewhere this evening. I'm not asked."

"Shows his poor taste," says I. "He's due there about eight o'clock, eh?"

"Seven-thirty," says Vee. "But I don't know what to think, Torchy—the traveling-bag and—"

"Don't bother a bit, Vee," says I. "Leave it to me. If it's Clyde at the bottom of this, I've as good as got him spiked to the track. Let Auntie pack her trunk if she wants to, and don't say a word. Give the giddy old thing a chance. It'll be all the merrier afterwards."

"But—but I don't understand."

"Me either," says I. "I'm a grand little guesser, though. And I'll be outside, in ambush for Clyde, from seven o'clock on."

"Will you?" says Vee,' sighin' relieved. "But do be careful, Torchy. Don't—don't be reckless."

"Pooh!" says I. "That's my middle name. If I get slapped on the wrist and perish from it, you'll know it was all for you."

Course, it would have been more heroic if Clyde hadn't been such a ladylike gent. As it is, he's about as terrifyin' as a white poodle. So I'm still breathin' calm and reg'lar when I sees him rollin' up in a cab about seven-twenty-five. I'm at the curb before he can open the taxi door.

"Sorry," says I, "but I'm afraid it's all off."

"Eh?" says he, gawpin' at me.

"And you with your suit-case all packed too," says I. "How provokin'! But they're apt to change their minds, you know."

"Do you mean," says he, "that—er—ah—"

"Something like that," I breaks in. "Anyway, you can judge. For, the fact is, some busybody has been gossipin' about your little trick of bawlin' out Alicia over the coffee and rolls and draggin' her round by the hair."

"Wha-a-at?" he gasps.

"You didn't mention the divorce, did you?" I goes on. "Nor go into details about your antique business? That Marie Antoinette dressin'-table game of yours, for instance. You know there is such a thing as floodin' the market with genuine Connecticut-made relics like that."

Gets him white about the gills, this jab does.

"Puppy!" he hisses out. "Do you insinuate that—"

"Not me," says I. "I'm too polite. But when you unload duplicates of the late Oliver Cromwell's writing-desk you ought to see that both don't go to friends of Colonel Brassle. Messy old party, the Colonel, and I understand he's tryin' to induce 'em to make trouble. Course, you might explain all that to Auntie; but in her present state of mind— Eh? Must you be goin'? Any word to send up? Shall I tell her this wilt-thou date is postponed to—"

"Bah!" says Clyde, bangin' the taxi door shut and signalin' the chauffeur to get under way. I think I saw him shakin' his fist back at me as he drives off. So rough of him!

Upstairs I finds Auntie all in a flutter and tryin' to hide it. Vee looks at me inquirin' and anxious, but I chats on for a while just as if nothing had happened. Somehow, I was enjoyin' watchin' Auntie squirm. My mistake was in forgettin' that Vee was fidgety, too. No sooner has Auntie left the room, to send Helma scoutin' down to the front door, than I'm reminded.

"Ouch!" says I. Vee sure can pinch when she tries. I decides to report.

"Oh; by the way," says I, as Auntie comes back, "I just ran across Mr. Creighton."

"Yes?" says Auntie eager.

"He wasn't feelin' quite himself," says I. "Sudden attack of something or other. He didn't say exactly. But I expect that concert excursion is scratched."

"Scratched!" says Auntie, lookin' dazed.

"Canceled," says I. "Anyway, he went off in a hurry."

"But—but he-was to have—" And there she stops.

"I know," says I. "Maybe he'll explain later, though."

No wonder she was dizzy from it, and it's quite natural that soon after she felt one of her bad headaches comin' on. So Vee and Helma got busy at once. After they'd tucked her away with the ice-bag and the smellin'-salts, she asked to be let alone; so durin' the next half hour I had a chance to tell Vee all about Creighton and his career.

"But he did seem so refined!" says Vee.

"Yon got to be," says I, "to deal in fake antiques. His mistake was in tacklin' something genuine"; and I nods towards a picture of Auntie.

"I don't see how I can ever tell her," says Vee.

"It would be a shame," says I. "Them late romances come so sudden. Why not just let her press it and put it away? Clyde will never come back."

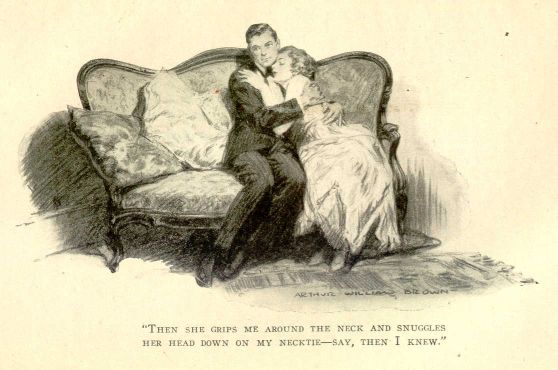

"Just think, Torchy," says Vee, sort of snugglin' up. "If it hadn't been for you!"

"That's my aim in life," says I—"to prove I'm needed in the fam'ly."

I expect you'll admit that when Mr. Robert slides out at 11 A.M. and don't show up again until after three he's stretchin' the lunch hour a bit. But, whatever other failin's I may have, I believe in bein' easy with the boss. So, when he breezes into the private office in the middle of the afternoon, I just gives him the grin, friendly and indulgent like.

"Well, Torchy," he calls over to me, "have I missed anyone?"

"Depends on how it strikes you," says I. "Mr. Hamilton Adams has near burned out the switchboard tryin' to get you on the 'phone. Called up four times."

"Ham, eh?" says he, shruggin' his shoulders careless. "Then I can hardly say I regret being late. I trust he left no message."

"This ain't your lucky day," says I. "He did. Wants to see you very special. Wants you to look him up."

"At the club, I suppose?" says Mr. Robert.

"No, at his rooms," says I.

"The deuce he does!" says Mr. Robert. "Why doesn't he come here if it's so urgent?"

"He didn't say exactly," says I, "but from hints he dropped I take it he can't get out. Sick, maybe."

"Humph!" says Mr. Robert, rubbin' his chin thoughtful. "If that is the case—" Then he stops and stares puzzled into the front of the roll-top, where the noon mail is sorted and stacked in the wire baskets.

I don't hear anything more from him for two or three minutes, when he signals me over and pulls up a chair.

"Ah—er—about Ham Adams, now," he begins.

"Say, Mr. Robert," says I, "you ain't never goin' to wish him onto me, are you? Why, him and me wouldn't get along a little bit."

"I must concede," says he, "that Mr. Adams has not a winning personality. Yet there are redeeming features. He plays an excellent game of billiards, his taste in the matter of vintage wines is unerring, and in at least two rather vital scrimmages which I had with the regatta committee he was on my side. And, while I feel that I have more than repaid any balance due— Well, I can't utterly ignore him now. But as for hunting him up this afternoon—" Mr. Robert nods at the stacks of letters.

"Oh, all right," says I. "What's his number?"

Mr. Robert writes it on a card.

"You may as well understand my position," says he. "I have already invested some twenty-five hundred dollars in Mr. Adams' uncertain prospects. I must stop somewhere. Of course, if he's ill or in desperate straits— Well, here is another hundred which you may offer or not, as you find best. I am relying, you see, on your somewhat remarkable facility for rescuing truth from the bottom of the well or any other foolish hiding-place."

"Meanin', I expect," says I, "that you're after a sort of general report, eh?"

"Quite so," says Mr. Robert. "You see, it's a business errand, in a way. You go as a probing committee of one, with full powers."

"It's a tough assignment," says I, "but I'll do my best."

For I'd seen enough of Ham Adams to know he wa'n't the kind to open up easy. One of these bull-necked husks, Mr. Adams is, with all the pleasin' manners of a jail warden. Honest, in all the times he's been into the Corrugated general offices, I've never seen him give anyone but Mr. Robert so much as a nod. Always marched in like he was goin' to trample you under foot if you didn't get out of his way, and he had a habit of scowlin' over your head like he didn't see you at all.

I expect that was his idea of keeping the lower classes in their place. He was an income aristocrat, Ham was. Always had been. Phosphate mines down South somewheres, left to him by an aunt who had brought him up. And with easy money comin' in fresh and fresh every quarter, without havin' to turn a hand to get it, you'd 'most think he could take life cheerful. He don't, though. Hardly anything suits him. He develops into the club grouch, starin' slit-eyed at new members, and cultivatin' the stony glare for the world in general.

And then, all of a sudden, his income dries up. Stops absolutely. Something about not bein' able to ship any more phosphate to Germany. Anyway, the quarterly stuff is all off. I'd heard him takin' on about it to Mr. Robert—cussin' out the State Department, the Kaiser, the Allies, anybody he could think of to lay the blame to. Why didn't someone do something? It was a blessed outrage. What was one to do?

Ham's next idea seems to be who was one to do; and Mr. Robert, being handy, was tagged. First off it was a loan; a good-sized one; then a note or so, and finally he gets down to a plain touch now and then, when Mr. Robert couldn't dodge.

But for a month or more, until this S. O. S. call comes in, he don't show up at all. So I'm some curious myself to know just what's struck him. I must say, though, that for a party who's been crossed off the dividend list for more'n a year, he's chuckin' a good bluff. Some spiffy bachelor apartments these are that I locates—tubbed bay trees out front, tapestry panels in the reception-room, and a doorman uniformed like a rear-admiral. I has to tell the 'phone girl who I am and why, and get an upstairs O. K., before I'm passed on to the elevator. Also my ring at B suite, third floor, is answered by a perfectly good valet.

"From Mr. Ellins, sir?" says he, openin' the door a crack.

"Straight," says I.

He swings it wide and bows respectful. A classy party, this man of Mr. Adams', too. Nothing down-and-out about him. Tuxedo, white tie, and neat trimmed siders in front of his ears. One of these quiet spoken, sleuthy movin' gents he is, a reg'lar stage valet. But he manages to give me the once-over real thorough as he's towin' me in.

"This way, sir," says he, brushin' back the draperies and shuntin' me in among the leather chairs and Oriental rugs.

Standin' in the middle of the room, with his feet wide apart, is Mr. Adams, like he was waitin' impatient. You'd hardly call him sick abed. I expect it would take a subway smash to dent him any. But, if his man fails to look the part of better days gone by, Ham Adams is the true picture of a seedy sport. His padded silk dressin'-gown is fringed along the cuffs, and one of the shoulder seams is split; his slippers are run over; and his shirt should have gone to the wash last week. Also his chin is decorated in two places with surgeon's tape and has a thick growth of stubble on it. As I drifts in he's makin' a bum attempt to' roll a cigarette and is gazin' disgusted at the result.

"Why didn't Bob come himself?" he demands peevish.

"Rush of business," says I. "He'd been takin' time off and the work piled up on him."

"Humph!" says Adams. "Well, I've got to see him, that's all."

"In that case," says I, "you ought to drop around about—"

"Out of the question," says he. "Look at me. Been trying to shave myself. Besides— Well, I can't!"

"Mr. Robert thought," I goes on, "that you might—"

"Well?" breaks in Mr. Adams, turnin' his back on me sudden and glarin' at the draperies. "What is it, Nivens?"

At which the valet appears, holdin' a bunch of roses.

"From Mrs. Grenville Hawks, sir," says he. "They came while you were at breakfast, sir."

"Well, well, put them in a vase—in there," says Ham. And as Nivens goes out he kicks the door to after him.

"Now, then," he goes on, "what was it Mr. Robert thought?"

"That you might give me a line on how things stood with you," says I, "so he'd know just what to do."

"Eh?" growls Ham. "Tell you! Why, who the devil are you?"

"Nobody much," says I. "Maybe you ain't noticed me in the office, but I'm there. Private sec. to the president of Mutual Funding. My desk is beyond Mr. Robert's, in the corner."

"Oh, yes," says Adams; "I remember you now. And I suppose I may as well tell you as anyone. For the fact is, I'm about at the end of my string. I must get some money somewhere."

"Ye-e-es?" says I, sort of cagey.

"Did Bob send any by you? Did he?" suddenly asks Adams.

"Some," says I.

"How much?" he demands.

"A hundred," says I.

"Bah!" says he. "Why, that wouldn't— See here; you go back and tell Bob I need a lot more than that—a couple of thousand, anyway."

I shakes my head. "I guess a hundred is about the limit," says I.

"But great Scott!" says Adams, grippin' his hands desperate. "I've simply got to—"

Then he breaks off and stares again towards the door. Next he steps across the room soft and jerks it open, revealin' the classy Nivens standin' there with his head on one side.

"Ha!" snarls Ham. "Listening, eh?"

"Oh yes, sir," says Nivens. "Naturally, sir."

"Why naturally?" says Adams.

"I'm rather interested, that's all, sir," says Nivens.

"Oh, you are, are you?" sneers Ham. "Come in here."

He ain't at all bashful about acceptin' the invitation, nor our starin' at him don't seem to get him a bit fussed. In fact, he's about the coolest appearin' member of our little trio.

Maybe some of that is due to the dead white of his face and the black hair smoothed back so slick. A cucumbery sort of person, Nivens. He has sort of a narrow face, taken bow on, but sideways it shows up clean cut and almost distinguished. Them deep-set black eyes of his give him a kind of mysterious look, too.

"Now," says Ham Adams, squarin' off before him with his jaw set rugged, "perhaps you will tell us why you were stretching your ear outside?"

"Wouldn't it be better, sir, if I explained privately?" suggests Nivens, glancin' at me.

"Oh, him!" says Adams. "Never mind him."

"Very well, sir," says Nivens. "I wanted to know if you were able to raise any cash. I haven't mentioned it before, but there's a matter of fifteen months' wages between us, sir, and—"

"Yes, yes, I know," cuts in Ham. "But yon understand my circumstances. That will come in time."

"I'm afraid I shall have to ask for a settlement very soon, sir," says Nivens.

"Eh?" gasps Adams. "Why, see here, Nivens; you've been with me for five—six years, isn't it?"

"Going on seven, sir," says Nivens.

"And during all that time," suggests Ham, "I've paid you thousands of dollars."

"I've tried to earn it all, sir," says Nivens.

"So you have," admits Ham. "I suppose I should have said so before. As a valet you're a wonder. You've got a lot of sense, too. So why insist now on my doing the impossible? You know very well I can't lay my hands on a dollar."

"But there's your friend Mr. Ellins," says Nivens.

Ham Adams looks over at me. "I say," says he, "won't Bob stand for more than a hundred? Are you sure?"

"He only sent that in case you was sick," says I.

"You see?" says Ham, turnin' to Nivens. "We've got to worry along the best we can until things brighten up. I may have to sell off some of these things."

A cold near-smile flickers across Nivens' thin lips.

"You hadn't thought of taking a position, had you, sir?" he asks insinuatin'.

"Position!" echoes Ham. "Me? Why, I never did any kind of work—don't know how. Tell me, who do you think would give me a job at anything?"

"Since you've asked, sir," says Nivens, "why, I might, sir."

Ham Adams lets out a gasp.

"You!" says he.

"It's this way, sir," says Nivens, in that quiet, offhand style of his. "I'd always been in the habit of putting by most of my wages, not needing them to live on. There's tips, you know, sir, and quite a little one can pick up—commissions from the stores, selling second-hand clothes and shoes, and so on. So when Cousin Mabel had this chance to buy out the Madame Ritz Beauty Parlors, where she'd been forelady for so long, I could furnish half the capital and go in as a silent partner."

"Wha-a-at?" says Ham, his eyes bugged. "You own a half interest in a beauty shop—in Madame Ritz's?"

Nivens bows.

"That is strictly between ourselves, sir," says he. "I wouldn't like it generally known. But it's been quite a success—twelve attendants, sir, all busy from eleven in the morning until ten at night. Mostly limousine trade now, for we've doubled our prices within the last two years. You'll see our ads in all the theater programs and Sunday papers. That's what brings in the—"

"But see here," breaks in Ham, "how the merry dingbats would you use me in a beauty parlor? I'm just curious."

Nivens pulls that flickery smile of his again.

"That wasn't exactly what I had in mind, sir," says he. "In fact, I have nothing to do with the active management of Madame Ritz's; only drop around once or twice a month to go over the books with Mabel. It's wonderful how profits pile up, sir. Nearly ten thousand apiece last year. So I've been thinking I ought to give up work. It was only that I didn't quite know what to do with myself after. I've settled that now, though; at least, Mabel has. 'You ought to take your place in society,' she says, 'and get married.' The difficulty was, sir, to decide just what place I ought to take. And then—well, it's an ill wind, as they say, that blows nobody luck. Besides, if you'll pardon me, sir, you seemed to be losing your hold on yours."

"On—on mine?" asks Ham, his mouth open.

Nivens nods.

"I'm rather familiar with it, you see," says he. "Of course, I may not fill it just as you did, but that would hardly be expected. I can try. That is why I have been staying on. I've taken over the lease. The agent has stopped bothering you, perhaps you have noticed. And I've made out a complete inventory of the furnishings. In case I take them over, I'll pay you a fair price—ten per cent. more than any dealer."

"Do—do you mean to say," demands Adams, "that you are paying my rent?"

"Excuse me, mine," says Nivens. "The lease has stood in my name for the last two months. I didn't care to hurry you, sir; I wanted to give you every chance. But now, if you are quite at the end, I am ready to propose the change."

"Go on," says Ham, starin' at him. "What change?"

"My place for yours," says Nivens.

"Eh?" gasps Ham.

"That is, of course, if you've nothing better to do, sir," says Nivens, quiet and soothin'. "You'd soon pick it up, sir, my tastes being quite similar. For instance—the bath ready at nine; fruit, coffee, toast, and eggs at nine-fifteen, with the morning papers and the mail laid out. Then at—"

"See here, my man," breaks in Adams, breathin' hard. "Are you crazy, or am I? Are you seriously suggesting that I become your valet?"

Nivens shrugs his shoulders.

"It occurred to me you'd find that the easiest way of settling your account with me, sir," says he. "Then, too, you could stay on here, almost as though nothing had happened. Quite likely I should go out a bit more than you do, sir. Well, here you'd be: your easy chair, your pictures, your favorite brands of cigars and Scotch. Oh, I assure you, you'll find me quite as gentlemanly about not locking them up as you have been, sir. I should make a few changes, of course; nothing radical, however. And, really, that little back room of mine is very cozy. What would come hardest for you, I suppose, would be the getting up at seven-thirty; but with a good alarm clock, sir, you—"

"Stop!" says Ham. "This—this is absurd. My head's swimming from it. And yet— Well, what if I refuse?"

Nivens lifts his black eyebrows significant.

"I should hope I would not be forced to bring proceedings, sir," says he. "Under the Wage Act, you know—"

"Yes, yes," groans Ham, slumpin' into a chair and restin' his chin on his hands. "I know. You could send me to jail. I should have thought of that. But I—I didn't know how to get along alone. I've never had to, you know, and—"

"Precisely, sir," says Nivens. "And allow me to suggest that another employer might not have the patience to show you your duties. But I shall be getting used to things myself, you know, and I sha'n't mind telling you. If you say so, sir, we'll begin at once."

Ham Adams gulps twice, like he was tryin' to swallow an egg, and then asks:

"Just how do—do you want to—to begin?"

"Why," says Nivens, "you might get my shaving things and lay them out in the bathroom. I think I ought to start by—er—dispensing with these"; and he runs a white hand over the butler siders that frames his ears.

Almost like he was walkin' in his sleep, Ham gets up. He was headed for the back of the suite, all right, starin' straight ahead of him, when of a sudden he turns and catches me watchin'. He stops, and a pink flush spreads from his neck up to his ears.

"As you was just sayin'," says I, "don't mind me. Anyway, I guess this is my exit cue."

I tries to swap a grin with Nivens as I slips through the door. But there's nothing doing. He's standin' in front of the mirror decidin' just where he shall amputate those whiskers.

First off Mr. Robert wouldn't believe it at all. Insists I'm feedin' him some fairy tale. But when I gives him all the details, closin' with a sketch of Ham startin' dazed for the back bathroom, he just rocks in his chair and 'most chokes over it.

"By George!" says he. "Ham Adams turning valet to his own man! Oh, that is rich! But far be it from me to interfere with the ways of a mysterious Providence. Besides, in six months or so his income will probably be coming in again. Meanwhile— Well, we will see how it works out."

That was five or six weeks ago, and not until Tuesday last does either of us hear another word. Mr. Robert he'd been too busy; and as for me, I'd had no call. Still, being within a couple of blocks of the place, I thought I might stroll past. I even hangs up outside the entrance a few minutes, on the chance that one or the other of 'em might be goin' in or out, I'd about given up though, and was startin' off, when I almost bumps into someone dodgin' down the basement steps.

It's Ham Adams, with a bottle of gasoline in one hand and a bundle of laundry under his arm. Looks sprucer and snappier than I'd ever seen him before, too. And that sour, surly look is all gone. Why, he's almost smilin'.

"Well, well!" says I. "How's valetin' these days?"

"Oh, it's you, is it?" says he. "Why, I'm getting along fine. Of course, I never could be quite so good at it as—as Mr. Nivens was, but he is kind enough to say that I am doing very well. Really, though, it is quite simple. I just think of the things I should like to have done for me, and—well, I do them for him. It's rather interesting, you know."

I expect I gawped some myself, hearing that from him. From Ham Adams, mind you!

"Ye-e-e-es; must be," says I, sort of draggy. Then I shifts the subject. "How's Mr. Nivens gettin' along?" says I. "Ain't married yet, eh?"

For a second Ham Adams lapses back into his old glum look.

"That is the only thing that worries me," says he. "No, he isn't married, as yet; but he means to be. And the lady—well, she's a widow, rather well off. Nice sort of person, in a way. A Mrs. Grenville Hawks."

"Not the one that used to send you bunches of roses?" says I.

He stares at me, and then nods.

"It seems that Mr. Nivens had already picked her out—before," says he. "Oh, there was really nothing between us. I'd never been a marrying man, you know. But Mrs. Hawks—well, we were rather congenial. She's bright, not much of a highbrow, and not quite in the swim. I suppose I might have— Oh, widows, you know. Told me she didn't intend to stay one. And now Mr. Nivens has come to know her, in some way; through his cousin Mabel, I suppose. Knows her quite well. She telephones him here. I—I don't like it. It's not playing square with her for him to— Well, you see what I mean. She doesn't know who he was."

"Uh-huh," says I.

"But I'm not sure just what I ought to do," says he.

"If you're callin' on me for a hunch," says I, "say so."

"Why, yes," says he. "What is it?"

"What's the matter," says I, "with beating him to it?"

"Why—er—by Jove!" says Ham. "I—I wonder."

He was still standin' there, holdin' the gasoline bottle and gazin' down the basement steps, as I passed on. Course, I was mostly joshin' him. Half an hour later and I'd forgot all about it. Never gave him a thought again until this mornin' I hears Mr. Robert explode over something he's just read in the paper.

"I say, Torchy," he sings out. "You remember Ham Adams? Well, what do you think he's gone and done now?"

"Opened a correspondence school for valets?" says I.

"Married!" says Mr. Robert. "A rich widow, too; a Mrs. Grenville Hawks."

"Zippo!" says I. "Then he's passed the buck back on Nivens."

"I—er—I beg pardon?" says Mr. Robert.

"You see," says I, "Nivens kind of thought an option on her went with the place. He had Ham all counted out. But that spell of real work must have done Ham a lot of good—must have qualified him to come back. Believe me, too, he'll never be the same again."

"That, at least, is cheering," says Mr. Robert.